This chapter presents financial products that have been developed to transfer and repackage credit risk: credit derivatives and securitization1 instruments such as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).

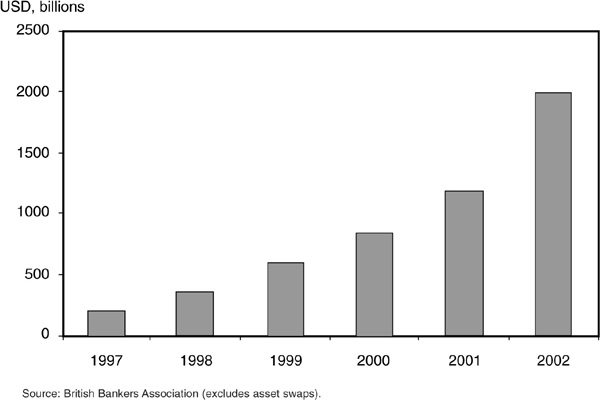

Credit derivatives are increasingly popular products. Figure 9-1 shows the dramatic growth in the volume outstanding of credit derivatives. These have started from zero in the early 1990s to exceed $2000 billion in 2002. Credit derivatives are instruments whose payoffs depend on a credit event such as a default, a downgrade, or a spread change. These products have been designed to isolate the credit risk component of an asset and to enable their users (buyers or sellers) to hedge or to take positions in pure credit risk.

FIGURE 9-1

Notional Amount Outstanding of Credit Derivatives

CDOs were created in the late 1980s and have grown dramatically since the mid-1990s. The issuance of CDOs has been supported by regulatory arbitrage opportunities and also by the possibility to realize positive spreads on similarly rated instruments. They are also useful in tailoring the risk profiles of the issues to the risk aversion of investors. All these issues are discussed later in the chapter.

In this chapter we introduce the main types of credit derivatives. We show how they can be used for managing credit risk and explain their structure. We then take an overall view of credit derivatives and discuss their benefits and their risks for banks, corporates, and the economic system as a whole.

As mentioned above, credit derivatives are relatively new products. They started in the early 1990s and now constitute a key component of credit markets. They were identified as a specific derivative class at an ISDA2 conference in 1992. A credit derivative is a bilateral financial contract that enables investors to trade the risk associated with the creditworthiness of a debtor. This contract is usually over the counter, and its payoff is contingent on credit events on the underlying reference entity. Some credit derivatives are cash-settled (the payoff is delivered in cash), while others are physically settled (payment is made by delivering the underlying financial instrument).

Six of the most actively traded types of credit derivatives are introduced in the section that follows. The subsequent section discusses the benefits and risks of credit derivatives for various players in the credit markets.

Figure 9-2 shows the holdings of the main types of institutions involved in the credit derivatives business. Banks are, unsurprisingly, by far the dominant players. They appear to be net buyers of protection, while reinsurance companies buy little protection but sell a lot. They are the most exposed to drops in the credit quality of issuers. This has implications for the riskiness of reinsurers as well as for the volatility of credit and equity markets, as will be shown below.

FIGURE 9-2

Buyers and Sellers of CDS Protection

As mentioned previously, credit derivatives are largely over-the-counter products. Each deal can therefore be considered as different from all previous ones, and frequently new characteristics are added to a given class of products. Here we will explain the stylized features of six of the main credit derivatives products:

1. Historically, credit derivatives started with asset swaps, which still represent a significant share of the market.

2. Credit default swaps (CDSs) are now the dominant product in the credit derivatives market. They are very popular because they are liquid and because they reflect in a transparent way the market’s view on the default likelihood of a specific counterpart.

3. Credit-linked notes (CLNs) are similar to CDSs but are packaged with a specific debt issue.

4. Total return swaps (TRSs) are contracts by which two parties exchange the returns on two assets.

5. Credit spread options (CSOs) are derivatives whose payoff depends on the value of the yield spread of an issue.

6. And finally basket instruments are products that integrate correlation effects among various obligors in addition to individual obligor credit risk.

The breakdown of the credit derivatives market by instrument type is reported in Figure 9-3.

FIGURE 9-3

Amount Outstanding by Asset Type

Asset swaps were the first type of credit derivatives. They can be seen as a standard interest rate swap on credit-risky products (Figure 9-4). An investor who has a position in a fixed-coupon bond swaps the interest payment with a counterpart (usually an investment bank) for a floating stream of coupons.

The main motivation for asset swap investors is to isolate interest rate from credit risk. They want to obtain a spread without being exposed to the risk of rising riskless interest rates. Most corporate bonds are issued with fixed coupons, and asset swaps enable investors to exchange the bonds’ coupons for Libor plus a predetermined spread.

One very substantial drawback of asset swaps is that the swap agreement is not terminated if the underlying bond defaults. The investor remains liable for the payment of fixed coupons and still receives the floating payments. After default the investor thus becomes exposed to the interest rate risk that he tried to avoid originally.

Credit default swaps are probably the simplest type of credit derivatives. They can be seen as insurance against the default of an obligor (Figure 9-5). The protection buyer pays a regular fee (as a percentage of the nominal amount of the contract) against the promise of a fixed amount (the par of the underlying asset) paid by the protection seller in case of default on the underlying asset. The main difference with a traditional insurance contract is that the amount paid in default is predetermined and does not depend on the severity of the loss on the underlying asset.

FIGURE 9-5

Credit Default Swap

Unlike asset swaps, most CDSs are standardized and often liquid contracts. They can be marked to market, and their price reflects very closely the market’s view on the probability of default of the underlying obligor. When the PD changes, the price of the CDS will change, and so will the spread on the underlying bond. CDSs can therefore be used as hedges against spread changes and not just against default.

The attractiveness of this product for portfolio managers is obvious: When they feel that they are overexposed to a specific counterpart, they may reduce their credit exposure while keeping the asset in their portfolios. This is particularly useful when the underlying asset is very illiquid, such as a bank loan, as the bank may not be able to sell the position on the secondary market. For protection sellers (an insurance company, for example) the appeal of CDS comes from the fact that they can take pure credit risk bets without having to incur interest rate risk (as in the case of a standard purchase of corporate bonds).

The pricing of a CDS is relatively straightforward. It consists of determining at time t the annual fee that the buyer has to pay the seller for default protection between times t and T. This price is then expressed as an annual percentage fee. Risk-neutral probabilities of default used in the pricing of CDSs can be extracted from the prices of traded bonds. A simple introduction to the pricing of CDSs can be found in Hull (2002).

Conversely, when one can observe a CDS price, one can infer immediately the market assessment of the default probability of the issuer. For some obligors, the CDS market is more liquid than that of the underlying bonds, and CDS spreads are frequently used in lieu of yield spreads.

Figure 9-5 assumes implicitly that the protection seller is itself not subject to default. Otherwise, the protection would become worthless in case of default of the protection seller. This is why protection sellers are generally AA- or AAA-rated and chosen to have low default correlation with the underlying issuer. Some puzzling CDS contracts are, however, available on the market. For example, it is not rare to see a bank offering default protection against its own sovereign. It is, though, unlikely that the bank would be in a position to meet its obligation, should the country it is based in default.

Credit-linked notes are debt obligations with contingent coupon and redemption value. They use the CDS technology explained above in a debt package. The issuer of a CLN sells the notes to investors and receives the proceeds (Figure 9-6). At the same time, the isssuer sells a CDS contract on another obligor to an investment bank. The investment bank therefore pays a regular fee to the issuer which is transferred in part to the CLN investors in the form of an enhanced coupon. In case of default of the other obligor, the issuer has to pay the investment bank, and the CLN investor loses parts (or all) of the principal.

FIGURE 9-6

Credit-Linked Notes

CLNs enable investors to combine a standard bond of a well-known and usually well-rated issuer with a credit derivative that provides enhanced yield. Many types of institutions that cannot invest in off-balance-sheet credit derivatives can invest in CLNs because they remain on the balance sheet of the investor. Banks are also interested in the CLN business because they are protection buyers on counterparts that are often linked to loans on their books.

A total return swap is a simple product that allows an investor to exchange the payment of a stream of floating coupons (usually specified as Libor or a similar interest rate plus a spread) for the return on a bond, a loan, a portfolio, or an index (or any other asset). It therefore enables her to take an exposure in the underlying asset without having to own the asset. Figure 9-7 illustrates the stylized structure of this product. The types of underlying assets include specific bonds, portfolios, indexes, etc. The term “total return” refers to the fact that the investor receives not only the interest payments or dividend but also the changes (positive or negative) in the market value of the underlying instruments.

FIGURE 9-7

Total Return Swaps

There are many advantages of investing in total return swaps rather than in the cash market. Leverage is an obvious one: The investor does not need to raise the necessary funds to buy the portfolio in the cash market. Transaction costs are also avoided; this is particularly true when the TRS is based on the return of a broad corporate bond index. TRSs also enable some investors to short some credits although they may be prevented from doing so directly in the cash market for regulatory reasons.

Credit spread options are derivatives whose underlying is the yield spread on a bond. Many CSOs are actually forward contracts and not really options, the buyer of such product being exposed to adverse moves in the credit spread. “True” credit spread options exhibit an asymmetric payoff structure, with the downside limited to the option premium.3

They can be American- or European-style options.4 They can also include a trigger barrier. For example, an “up-and-out” option is designed such that if the spread increases above, say, 200 basis points, the option becomes worthless.

Credit spread options have not had the success one could have expected when they were first launched in the early nineties. Trading and new issuance of these options is still relatively low. This may seem surprising as they can offer a very valuable protection for portfolio managers who are significantly affected by changes in the level of spreads. Several reasons may help explain this fact. First, they are more complex instruments to price and hedge than standard products (CDS contracts, for example).

Second, most corporate bond issues are quite illiquid, and it is therefore possible to manipulate their spread. When trading is thin, a large order may affect the spread on an issue and drive credit spread option prices to abnormal levels. This problem could be avoided by writing options on spread indices rather than on specific names. However, there is no market standard for corporate bond indices similar to the S&P 500 for equities, for example. A multitude of indexes are available, but no consensus has yet emerged on the most reliable or trustworthy. Furthermore, most indexes are calculated by investment banks, and their competitors may doubt their impartiality and may not be willing to trade options based on them.

Third, and most importantly, the popularity of CDSs may explain the limited success of CSOs. It is possible to hedge a substantial part of credit spread movements by taking positions in CDSs. CDSs are cheaper (tighter bid-ask spreads) than CSOs, and although the hedge provided by CDSs may be imperfect, they are often preferred by investors for cost reasons.

CDSs are increasingly becoming a well-established and standardized industry. Investment banks have moved on to develop more customized products such as basket instruments. The idea is to trade credit risk on multiple issuers with one contract. Default correlations are therefore key to the hedging and valuation of these products. A popular type of basket credit derivative is the nth-to-default option, which pays the buyer a given amount if at least n obligors default (out of a specified pool) during the life of the option.

Credit derivatives are a new asset class, and it is worthwhile discussing their economic implications as well as their advantages and risks for users. Many of the benefits for individual products have already been discussed in the chapter. In this section we focus primarily on general considerations regarding this class of asset and not on specific characteristics of products.

The main benefit of credit derivatives is to isolate the credit component of commonly traded instruments such as bonds and loans. By doing so they enable users to fine-tune their exposure to various counterparts. For example, they can help a bank expand its lending to one of its clients while avoiding overconcentration on a specific name. They are therefore very efficient tools for hedging and managing credit risk in order to optimize portfolio diversification.

In addition, credit derivatives bring more liquidity to debt markets. Some companies do not issue public debt but borrow money from banks. Thanks to credit derivatives, investors obtain access to counterparties or markets that were not publicly available previously. More generally, they contribute to building complete markets,5 implicitly providing prices for an increasing number of debt instruments at various maturities.

In addition, credit derivatives enable investors to enhance their yields. In the current period where interest rates are low, many investors are looking for alternatives in order to increase their performance. Insurers and hedge funds have therefore become significant sellers of credit protection. Asset managers are increasingly considering entering such markets.

These indisputable advantages have to be balanced with a series of drawbacks, some affecting the investors, some the sellers of credit derivatives, and some the global financial system.

Like most derivative instruments, credit derivatives can be used to increase the leverage of a bank and thus have important implications in terms of risk management and regulation. A distinguishing feature of credit derivatives is the complexity of the legal documentation involved to support the products. Credit derivatives have been tainted by several high-profile legal disputes due to the complexity of the contingent payments involved.

For example, in 1998 Russia defaulted on its domestic debt while maintaining normal payment of coupon and principal on its external debt. At the time, many credit derivatives were written on Russia in fairly vague terms. The question at that time was to determine whether the moratorium on domestic debt should be considered as a credit event for all credit derivatives on Russia. Protection buyers and sellers naturally had very different views on the matter.

Another example of legal problems arising in credit derivatives is the dispute between UBS and Deutsche Bank (DB) about a credit default swap contract on Armstrong World Industries (AWI) in 2001. UBS was seeking default protection from DB on AWI, which was facing major asbestos claim liabilities. Between the time the swap was agreed and the time it was confirmed in writing by DB, a new holding company (Armstrong Holding) was formed such that AWI became a subsidiary, but the holding did not assume the liabilities of AWI. The contract received by UBS was a credit default swap on the holding and not on AWI and was therefore not offering protection against a default (which eventually occurred) related to asbestos claims.

In order to clarify legal issues and help standardize and expand the market for credit derivatives, ISDA put forward, in July 1999, some standardized documentation that is widely accepted by market participants. This ISDA framework reports six credit events that can trigger payment on a credit default swap: bankruptcy, failure to pay, obligation default, obligation acceleration, repudiation/moratorium, and restructuring.

A lot of debate has surrounded this ISDA documentation, in particular about the criteria to define precisely a payment trigger.6 Market participants have recently attempted to further narrow the list of events that could trigger payouts by eliminating what is often called “soft” credit events. Such events correspond indeed to credit deterioration rather than to default. In addition, different interpretation of the occurrence of such events has frequently led to litigation. In April 2002, European market participants abandoned two such soft credit events—obligation acceleration and repudiation/moratorium. They were following the initiative already taken by U.S. dealers. Despite these changes, uncertainty remains over the issue of debt restructuring, on which there has been ongoing disagreement among traders. This has led to the trading of credit default swaps both with and without restructuring clauses. European banks, for instance, have often offered contracts with ISDA’s 1999 terminology, while since May 2001 U.S. dealers have been switching to contracts with a narrower definition of restructuring. This debate on the restructuring clauses is now also related to regulatory issues. The Basel Committee is currently reviewing whether dropping them should impact capital relief associated with credit derivatives.

The explosion of credit derivatives has been directly linked to regulatory arbitrage. Under the Basel I framework, banks have been allowed to pour large parts of their banking book in their trading book, thanks to credit derivatives.

Practically speaking, a loan on the banking book of bank A would receive a capital charge of 8 percent. By buying a protection complying with regulatory requirements, bank A would offload its risk and obtain full capital relief. The credit derivative transaction between bank A and bank B will be a transaction between two OECD banks for the same exposure. The new capital charge will therefore be limited to 1.6 percent for bank B.

With Basel II new rules, such arbitrage opportunities will be partially reduced, as the treatment of regulatory capital charges for transactions between banks will depend on their creditworthiness and no longer on their domicile (OECD or not).7

Credit derivatives are complex in their structure and often involve shifting risk off balance sheet. They are therefore treated by regulators with a lot of caution. Transparency is of paramount importance to gain the confidence of investors, and off-balance-sheet deals make it difficult for analysts to determine the actual exposure of a bank to various credits.

Another problem linked to the multiplicity of positions in a given name is that of “overcrowding” a credit. A bank may have a commercial unit dealing with a specific corporate and have at the same time an investment banking arm selling protection on the same name. If credit limits are set at the group level, the commercial bank may not be able to expand its exposure to the corporate. The credit is crowded out, and a genuine corporate financing need is ruled out because of credit derivatives activity.

The increased volatility reported in the credit (in particular in the spreads of corporate bonds) and equity markets has been blamed on the growing importance of credit derivatives. Credit derivatives allow us to sell credit short, which was not possible a few years ago. Therefore speculation on negative as well as positive credit events leads to larger swings in credit positions.

In order to understand the statement about the increased volatility in the equity markets, it is useful to recall that equity-based models of credit risk are being adopted by a large proportion of market participants. Equity volatility therefore spills over to credit markets. The reverse is also true because of hedging strategies undertaken by default protection sellers.

Figure 9-8, taken from Keppler and Williams (2003), illustrates how risk is passed along the financial systems and how the various players hedge their positions. It starts with an airline company borrowing from a regional bank. The bank grants the loan and enters simultaneously in a CDS contract with a larger institution (money center bank). The regional bank therefore receives interest from the airline company and pays a fee to the money center bank in exchange for protection against default by the airline. The money center bank then passes the risk to a reinsurance company, which is the natural buyer for this risk (see Figure 9-2). The reinsurance company will frequently hedge its exposure by shorting the equity of the airline company: If the airline goes into difficulties, the likelihood of paying the default value increases but the equity price drops, thereby protecting the insurance company. The last step shows one of the perverse effects of the transfer of risk via CDSs. The risk does not disappear but is reinjected into the economy via higher equity volatility. This equity volatility affects all agents, from the corporate itself to the banks and on to the reinsurance companies.

FIGURE 9-8

Risk Transfer in the Financial System

In this section we study structured products called collateralized debt obligations that were introduced in the late eighties following the development of the high-yield bond market and the long experience of mortgage bonds.

“CDO” is a generic term for a vast class of securitization8 products, in which a portfolio of debt instruments is used as collateral to back the issuance of new debt issues. The portfolio is often transferred from a bank’s balance sheet to a bankruptcy-remote company (a special-purpose vehicle, or SPV). The SPV then issues bonds of various seniorities backed by the pool of assets (Figure 9-9).

FIGURE 9-9

Simple CDO Structure

The senior notes (usually well rated) are repaid first using either the sale of assets in the SPV or the cash flows generated by these assets. Once the senior notes have been repaid in full, the SPV repays the subordinated (mezzanine) notes, and finally the equity (the first loss tranche) gets all the upside, after repayments of the other notes.

Tranching is the process of creating notes of various seniorities and risk profiles backed by the same pool of assets. This process enables the issuer to target investors with different risk aversions or trading restrictions. The top tranche is the senior class, which is designed to obtain an AAA rating (see Figure 9-10). The remainder of the liabilities of the SPV is subordinated to this class and obtains lower ratings. The bottom tranche is called equity.

FIGURE 9-10

Example of a Tranching of a CDO

The repayment of notes follows the priority order and is often compared to a waterfall. Cash flows are used to repay the most senior tranche first. Once the senior note is repaid in full, additional cash flows are used to service the mezzanine and subordinated notes, and, finally, all the cash left over goes to equity holders.

When the pool consists of loans or bonds only, the structure is called, respectively, collateralized loan obligation (CLO) or collateralized bond obligation (CBO). CDOs encompass CLOs, CBOs, and securitizations backed by a portfolio comprising both loans and bonds.

Some types of assets commonly used in CDOs are listed in Table 9-1. In fact, any type of debt can be securitized, and the table represents only a small sample of the categories of assets that can back these structures.

TABLE 9-1

Main Types of Underlying Collateral

The taxonomy of CDOs is generally performed according to three main criteria:

1. The nature and the source of repayment of the collateral pool. Using the cash flows generated by the ongoing receipts on the physical assets in the pool or the cash flows generated by the synthetic pool9 or the market value, i.e., the proceeds from the sale of those assets

2. The stability of the collateral pool. Either a static pool or an actively managed pool by means of reinvestment and/or substitution

3. The motivation behind securitization. Balance sheet management or arbitrage, either regulatory arbitrage or arbitrage stemming from capital market dislocations

Cash Flow CDOs A simple cash flow CDO structure is described in Figure 9-11. The issuer (special-purpose vehicle) purchases a pool of collateral (bonds, loans, etc.) that will generate a stream of future cash flows (coupon or other interest payment and repayment of principal). Standard cash flow CDOs involve the physical transfer of the assets.10

FIGURE 9-11

Structure of a Cash Flow CDO

This purchase is funded through the issuance of a variety of notes with different levels of seniority. The collateral is managed by an external party (the collateral manager) who deals with the purchases of assets in the pool and the redemption of the notes. The manager also takes care of the collection of the cash flows and of their transfer to the note holders via the issuer. The risk of a cash flow CDO stems primarily from the number of defaults in the pool. The more frequently and the more quickly obligors default, the thinner the stream of cash flows available to pay interest and principal on the notes. The cash flows generated by the assets are used to pay back investors in sequential order from senior investors (class A) to equity investors that bear the first-loss risk (class D). The par value of the securities at maturity is used to pay the notional amounts of CDO notes.

Synthetic CDOs An alternative to the actual transfer of assets to the SPV is provided by synthetic CDOs (see Figure 9-12).11 These structures benefit from advances in credit derivatives and transfer the credit risk associated with a pool of assets to the SPV while keeping the assets on the balance sheet of the bank. The SPV sells credit protection to the bank via credit default swaps.

FIGURE 9-12

Structure of a Synthetic CDO

Although synthetic CDOs are sometimes classified as balance sheet securitizations, the capital relief associated with them is often lower than for structures involving the actual sale of assets. The motivation for avoiding a true sale of the assets may be to preserve client relationships (a corporate may perceive as a sign of mistrust the sale of its loans to an SPV) or to maintain secrecy about the composition of the bank’s balance sheet. Some loans may also not be eligible for resale for contractual reasons but may still be securitized through a synthetic structure.

Synthetic deals may be fully funded, through recourse to CLN (credit-linked notes), or partially funded in order to cover the risk on the AAA tranche only. Some CDOs can be a mix of cash flow and synthetic transactions when the collateral pool includes both physical and synthetic assets.

Market Value CDOs A market value CDO differs from a cash flow CDO in that the underlying pool is marked to market on a periodic basis. If the aggregate value of the collateral pool goes beyond a defined threshold, then the collateral manager has to sell collateral and pay down CDO notes in order to restore an acceptable level. The collateral manager plays a much more active role and has a lot of flexibility in the allocation of the pool of collateral. In particular, the manager can increase or decrease the leverage of the structure to boost returns or mitigate risk.

Traditional CDOs, such as cash flow CDOs, generally rely on a static pool, although it is not always the case. In contrast, market value CDOs and synthetic CDOs rely on revolving pools based on active management and trading by the collateral manager during the reinvestment period.

In principle, cash flow, synthetic, and market value transactions correspond to either balance sheet or arbitrage motivations, explained below. The various types of transactions are presented in Figure 9-13

FIGURE 9-13

Global CDO Sector Rated by S&P in 2001

Balance sheet deals are structured in order to obtain regulatory capital relief. Assets consuming too much capital are removed from the bank’s balance sheet and are used to back the issuance of the notes.

Arbitrage CDOs are primarily seeking to exploit the difference in yield between the pool of collateral (often constituted of speculative-grade assets) and the notes issued by the CDO. A large share of the notes will be rated investment grade and will therefore command low spreads over Treasuries. The difference in spreads is considered an arbitrage.

We will return to the distinction between balance sheet and arbitrage deals in the next section on issuer motivations.

As mentioned above, there are, broadly speaking, two types of motivations for issuers: arbitrage and balance sheet management.

Arbitrage denotes the search for yield or revenue. It can take several forms:

Issuers may seek to realize a positive spread between the high-yield assets in the pool and the lower yield on the notes.

Issuers may seek to realize a positive spread between the high-yield assets in the pool and the lower yield on the notes.

A bank offloading parts of its balance sheet via a CDO can free up some credit lines and increase its assets under management. This helps generate stable management fees.

A bank offloading parts of its balance sheet via a CDO can free up some credit lines and increase its assets under management. This helps generate stable management fees.

Most issuers keep parts of equity tranche and can therefore benefit from all the upside after repayment of the other notes.

Most issuers keep parts of equity tranche and can therefore benefit from all the upside after repayment of the other notes.

Balance sheet management was historically the primary reason for CDO issuance. The idea is to move assets off balance sheet in order to benefit from capital relief.

In order to illustrate the benefits of CDOs in reducing regulatory capital requirements, let us go back to the CDO example noted earlier (Figure 9-10). Assume that a bank has $1 billion of commercial loans on its balance sheet on which it earns an average interest rate of Libor + 150 basis points. The bank funds the loans at Libor and therefore earns a net spread of 150 basis points.

The current Basel rules (see Chapter 10) imply that the bank must keep at least 8 percent of this nominal amount as regulatory capital. The return on regulatory capital is therefore: $15 million/$80 million = 18.75 percent.

If the bank decides to securitize its loan portfolio using the CDO structure shown above, it will still earn Libor + 150 basis points from the loans. However, it will have to pay an average of Libor + 67 basis points on the various tranches of the CDO (the assumed rates are shown in Figure 9-14). The $40 million (4 percent of $1 billion) equity tranche is retained on the balance sheet and must be covered by $40 million in capital. All other loans are transferred to an SPV and therefore are no longer subject to capital allocation. Hence the return on regulatory capital becomes ($15 million − $6.7 million)/$40 million = 20.75 percent.

FIGURE 9-14

CDO Tranches and Associated Interest Rates

Given the very substantial sums involved, 2 percent extra return represents a significant amount. Naturally the savings depend on market conditions (how much return can be obtained from the loans and the interest rates to be paid on the CDO tranches), but the current regulatory regime tends to encourage regulatory arbitrage. Forthcoming changes in the regulatory capital charges will dampen this incentive, at least for good-quality loans on the balance sheet. These will indeed benefit from lower capital charges, and it may no longer be worthwhile for banks to securitize them.

Obviously the risk of the bank is affected by the transaction. It has sold (via an SPV) the safer tranches of the CDO but retains the very speculative equity. One can therefore argue that in the scenario detailed above, the bank is now more risky than when it held the loan on its balance sheet. In essence, it has increased its leverage.

CDO securitization, of course, does not systematically entail a higher level of risk. For instance, there is true risk mitigation when part or all of the first loss tranche is sold.

CDO notes have proved popular with investors for many reasons:

CDO tranches tend to offer a yield premium on bonds with identical ratings and are therefore attractive for their rate of interest.

CDO tranches tend to offer a yield premium on bonds with identical ratings and are therefore attractive for their rate of interest.

They also enable investors unwilling or unable (for example, for regulatory reasons) to invest in speculative securities to take an exposure to that market. By investing in an investment-grade tranche of a high-yield CDO, the investor has a safe investment and yet is linked to the performance of the high-yield market.

They also enable investors unwilling or unable (for example, for regulatory reasons) to invest in speculative securities to take an exposure to that market. By investing in an investment-grade tranche of a high-yield CDO, the investor has a safe investment and yet is linked to the performance of the high-yield market.

A CDO tranche can be seen as a stake in a diversified portfolio. It is therefore a way to benefit from some diversification while investing in one security only.12

A CDO tranche can be seen as a stake in a diversified portfolio. It is therefore a way to benefit from some diversification while investing in one security only.12

While some of the objectives of issuers in the various tranches are common, their interests are divergent as far as the investment policy and the management of the SPV collateral are concerned. Investors in the equity tranche benefit from high volatility in the collateral pool.13 In the case of cash flow CDOs, equity tranche holders would prefer a large proportion of high-coupon very speculative debt as the pool. Their bet would be to have the principal of the debt repaid quickly using the high-coupon payments before a large number of defaults puts an end to their interest payments.

Investors in AAA tranches, on the other hand, favor lower coupons from stable and well-rated issues. Their upside potential is capped by the principal of the debt, and volatility therefore damages the value of their investment.

Investors in subordinated notes occupy a middle ground. They do not share the unlimited upside of equity holders but require sufficient cash flow to recover their investment.

The conflicting interests of investors highlight the difficulty of the work of the collateral manager. His job is to manage the pool of assets to satisfy the diverse needs of investors. A too-prudent investment policy would in many cases lead to the equity tranche expiring worthless. A management policy favoring return over prudence would jeopardize the investment of the highest tranches. The collateral manager is involved in a multiperiod game in which he has to reconcile the interests of both types of investors in order to attract them to forthcoming structures he will manage.

In this section we deal with the rating of CDO tranches. We present an overview of the analytical tools used by Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s.

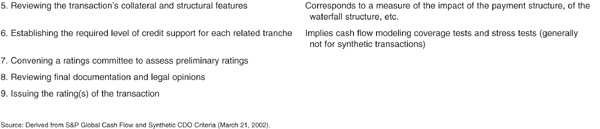

While these tools are actually used by rating agencies and by structurers of CDOs targeting a specific rating breakdown for their notes, they constitute only a small part of the credit assessment and rating allocation process. Within S&P, it actually corresponds to one step out of nine, as reported in Table 9-2. In particular there are several important due diligence elements that have to be mentioned such as:

TABLE 9-2

The Steps for the CDO Rating Process

A careful analysis of the assets of the pool (step 1)

A careful analysis of the assets of the pool (step 1)

A detailed review and monitoring of the collateral manager (step 3)

A detailed review and monitoring of the collateral manager (step 3)

A review of the guarantees and interest rate/currency hedges of the structure (step 5)

A review of the guarantees and interest rate/currency hedges of the structure (step 5)

The analysis of coverage ratios (step 6)

The analysis of coverage ratios (step 6)

S&P’s main tool for assessing the risk of CDO tranches is a Monte Carlo engine called CDO Evaluator. It is easy to use and straightforward. Its architecture is similar to several of the factor-based models described in Chapter 6.

The inputs of the model are the list of exposures, their amounts, the industry of the issuers, and their ratings. The engine simulates correlated binary random variables that represent default (1) or nondefault (0) and are calibrated on the probability of default induced by the rating.

In order to be rated AAA, the senior tranche must have a probability of default equivalent to that of a AAA corporate. CDO Evaluator calculates the maximum proportion X of defaults in the asset pool that would be compatible with a full payment of coupon and principal by the tranche. The tranche can then be rated AAA if the probability of observing a proportion of default x > X during the life of the CDO is less than or equal to the probability of an AAA corporate defaulting during the same period of time.

Figure 9-15 illustrates the output of the model.14 It shows two possible realizations for the loss distributions in the underlying CDO pool. The x-axis corresponds to the proportion of default in the pool. Assuming that an AAA corporate bond with the same maturity as that of the CDO has on average a 1 percent probability of default, we are looking at the 1 percent threshold in the CDO loss distribution. It is similar to looking for a VaR threshold at the 99 percent confidence level.

FIGURE 9-15

Effect of Correlation on Portfolio Defaults and Rating Threshold

In the first case, defaults are assumed to be uncorrelated, and the AAA threshold is situated at about 26 percent defaults in the pool. This figure means that there is only a 1 percent chance that more than 26 percent of the securities in the pool will default during the life of the CDO. Therefore, if the tranche can withstand at least 26 percent of defaults in the pool without itself defaulting, it can be rated AAA.

When correlations are introduced (30 percent intra-industry asset correlation, 0 percent interindustry asset correlation in this example), the AAA threshold shifts to a 49 percent default rate in the pool. Correlations swell the likelihood of extreme bad events, and it is therefore natural that the threshold should increase.

It is important to emphasize again that the model in itself does not guarantee a specific rating. It is just provided as a guide for CDO structurers and is used by S&P to obtain a first impression on the deal. The model’s output is indeed complemented by additional stress-testing adjustments and of course by all the steps briefly described in Table 9-2.

In particular, for cash flow CDOs, a review of the performance of the collateral pool based on some predetermined stressed default patterns is key to ensure that the stream of expected cash flows is compatible with the tranching defined using CDO Evaluator. The objective is to ensure that the underlying notes will pay timely interest and ultimate principal at a given default rate. For instance, if CDO Evaluator determines that the AAA tranche is bounded by a maximum 49 percent default rate, the cash flow model will have to exhibit a higher maximum default rate (the break-even rate), for example 52 percent.

Instead of simulating the actual distribution of losses in the pool, Moody’s relies on an approximate analytical shortcut mapping the actual portfolio of correlated assets to a homogeneous pool of uncorrelated assets using a diversity score.

The idealized pool is such that each asset has the same probability of default and same exposure size and that all assets are uncorrelated. Calculating the loss distribution of such a simplified portfolio is easy, as will be shown below.

Ignoring LGD,15 two inputs are necessary for the calculation of the loss distribution: the probability of default p and “decorrelation” adjustment (diversity score) for all assets in the idealized pool. Using these two inputs, we can calculate the default loss distribution using the binomial law.

We proceed in three steps:

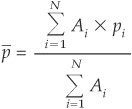

Calculating the average probability of default in the pool. Let us assume that there are N assets in the pool. Each of them has a “real” probability of default16 pi, for

Calculating the average probability of default in the pool. Let us assume that there are N assets in the pool. Each of them has a “real” probability of default16 pi, for  , during the life of the CDO. The idealized probability of default

, during the life of the CDO. The idealized probability of default  is calculated as the weighted average of PDs:

is calculated as the weighted average of PDs:

where Ai denotes the par value of asset i.

Incorporating concentration risk. As recalled earlier, the main idea is to replace a complex portfolio of N correlated assets with a simpler pool of

Incorporating concentration risk. As recalled earlier, the main idea is to replace a complex portfolio of N correlated assets with a simpler pool of  homogeneous uncorrelated facilities. Ignoring correlation leads to an underestimation of tail risk (see Figure 9-15, for example), and the idealized portfolio must be adjusted to compensate for this downward bias. The diversity score measures how concentrated the pool of assets is, in terms of industrial sectors. Moody’s has a list of about 30 sectors and counts the number of assets that are classified in each sector. Sectors with large concentrations of assets are penalized with a large weight. The weights used by Moody’s as a function of the number of firms in a given sector are provided in Table 9-3. Appendix 9A shows how one can relate the determination of a diversity score to the problem of matching the mean and variance of the real and idealized loss distributions.

homogeneous uncorrelated facilities. Ignoring correlation leads to an underestimation of tail risk (see Figure 9-15, for example), and the idealized portfolio must be adjusted to compensate for this downward bias. The diversity score measures how concentrated the pool of assets is, in terms of industrial sectors. Moody’s has a list of about 30 sectors and counts the number of assets that are classified in each sector. Sectors with large concentrations of assets are penalized with a large weight. The weights used by Moody’s as a function of the number of firms in a given sector are provided in Table 9-3. Appendix 9A shows how one can relate the determination of a diversity score to the problem of matching the mean and variance of the real and idealized loss distributions.

TABLE 9-3

Diversity Score for CDO Risk Evaluation

An example will help clarify the procedure leading to the calculation of the number of firms D in the idealized portfolio. Assume that we have a portfolio of  correlated assets. These assets are grouped in the various sectors, and the number of assets in each sector is counted. Assume that in our example we find that, in a given sector, there are either 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 assets (Table 9-4). For example, there are 11 sectors with 3 assets and 5 sectors with 5 assets, etc.17

correlated assets. These assets are grouped in the various sectors, and the number of assets in each sector is counted. Assume that in our example we find that, in a given sector, there are either 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 assets (Table 9-4). For example, there are 11 sectors with 3 assets and 5 sectors with 5 assets, etc.17

TABLE 9-4

Example of a Diversity Score Calculation

Each sector concentration is weighted by a diversity score (row B) extracted from Table 9-3. Row D reports this weighted number of firms. It is calculated as the product of B and C. The sum of the elements of the last row is the portfolio diversity score (D). In this example  . It means that a portfolio of 61 independent firms is assumed to mimic the true portfolio of 100 correlated firms accurately.

. It means that a portfolio of 61 independent firms is assumed to mimic the true portfolio of 100 correlated firms accurately.

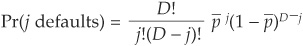

Calculating the loss distribution. Given that the constituents of the idealized portfolio are by construction uncorrelated and have the same probability of default, we can immediately obtain the probability of observing

Calculating the loss distribution. Given that the constituents of the idealized portfolio are by construction uncorrelated and have the same probability of default, we can immediately obtain the probability of observing  defaults using the binomial distribution:

defaults using the binomial distribution:

The rating can then be assigned based on the probability of observing a given amount of loss, as in the simulation method proposed by S&P.

Pricing and assessing the risk of CDO notes are complex procedures. CDOs are often cumbersome structures with embedded options, guarantees, prepayment covenants, a variety of collateral types, etc.

Closed-form solutions for CDOs therefore come at the cost of heroic simplifying assumptions or are available only for the simplest structures. Duffie and Garleanu (2001) analyze the risk and valuation of CDOs in an intensity model where the issuers’ hazard rates are assumed to follow a jump diffusion process. A model by Pykhtin and Dev (2002) for calculating capital for CDO tranches is described in Appendix 9B.

A numerical methodology is adopted in the S&P Risk Solutions’ Portfolio Risk Tracker model (see Chapter 6). It consists of simulating realizations of the value of the collateral pool and calculating the price of the CDO tranches by a technique similar to least-square Monte Carlo proposed by Longstaff and Schwartz (2001). The algorithm starts by calculating the payoff of each tranche at the maturity of the CDO and rolls backward until the issuance of the notes by estimating the payoff of each tranche conditional on the performance of the pool of assets at each time step.

Credit derivatives and CDOs have become very popular products for managing credit risk. They allow for a better tailoring of the risk-return profile associated with credit instruments and for more effective management of balance sheet structures. Financial innovation in the area of structured credit products is still ongoing. CDOs of CDOs (where the pool of underlying bonds itself comprises CDO tranches) are becoming more widespread. Credit derivatives are increasing in liquidity and coverage.

Innovations often come at the cost of more uncertainty. Structured credit products are still recent and are not understood by all market players. Regulators are struggling to cope with the recent development in credit derivatives and securitizations, and some investors have learned the hard way that these instruments are, like any other, not offering extra yield without involving more risk.

These teething problems will probably disappear once the market is more mature. They are likely to become standard products as familiar as interest rate swaps are today.

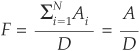

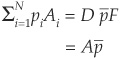

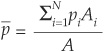

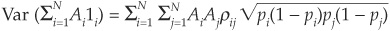

The idea behind the diversity score is that one looks for a simple portfolio of homogeneous (same exposure size, same PD) uncorrelated assets that will replicate the mean and variance of the loss distribution of the true pool of assets. (The other moments of the distribution will not be matched.) The real portfolio consists of N assets with pairwise default correlation ρij, individual default probability pi and exposure size Ai. The sum of individual exposures is denoted as A. The replicating portfolio has D facilities with identical probability of default  and face value F.

and face value F.

The steps below illustrate how to derive the diversity score D:

1. Calculating the exposure size. The total portfolio size must equal the real portfolio size. Therefore the face value of idealized exposures is just the mean exposure size:

2. Calculating the probability of default. The mean loss on the idealized portfolio must equal that of the true portfolio. Therefore:

which leads to

The idealized probability of default is just the face value–weighted average of default probabilities.

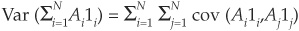

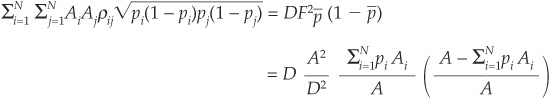

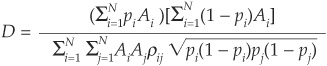

3. Computing the diversity score D. The diversity score is finally obtained by matching the variance of the losses of the true and idealized portfolios.

The variance of the true portfolio is the sum of the covariances of the individual assets:

where 1i is the indicator function taking value 1 if asset i defaults and 0 otherwise. Recalling that the variance of a binomial distribution with probability pi is pi(1 − pi), we get

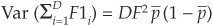

The variance of the loss in the idealized portfolio is

Matching the variances of the two portfolios gives us

and finally

Once D and  are determined as above, they can be inserted into the binomial probability equation in order to obtain the idealized loss distribution.

are determined as above, they can be inserted into the binomial probability equation in order to obtain the idealized loss distribution.

Pykhtin and Dev (2002) propose a simple factor-based model18 for the evaluation of CDO risk. Their model is based on several key assumptions:

1. The portfolio of loans underlying the securitization tranche is asymptotically fine-grained (a very diversified pool of collateral with no large proportion accounted for by any asset).

2. This portfolio of loans is driven by one systematic risk factor.

3. The investor’s portfolio where the CDO tranche is held is also asymptotically fine-grained.

4. The investor’s portfolio is driven also by one (different) systematic risk factor.

5. The investor’s exposure to the CDO tranche is small compared with the size of her portfolio.

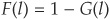

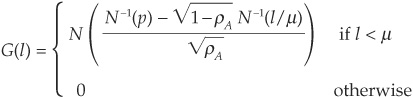

The CDO is based on a portfolio of bonds with a loss rate probability distribution function  . Thus G(l) is the probability that the loss rate L on the collateral portfolio is above the level l.

. Thus G(l) is the probability that the loss rate L on the collateral portfolio is above the level l.

The portfolio consists of M identical loans with probability of default p and with normally distributed LGD with mean µ. Each issuer is characterized by asset returns that follow a simple Gaussian one-factor model identical to those described in Chapters 5 and 6:

ξi is the idiosyncratic factor for issuer i, and Y is the common factor. The default threshold is identical for all loans and is obtained as N−1(p).

We can thus apply the formula of Vasicek (1991) in order to calculate the distribution of the loss rate in the portfolio:

Let us consider a securitization tranche with lower bound T1 and upper bound T2. Investors in this stand-alone tranche face the loss profile depicted in Figure 9B-1.

FIGURE 9B-1

Loss in the Pool versus Loss in the CDO Tranche

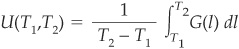

The expected loss on this tranche is

The formula above also corresponds to the expected loss on an infinite portfolio of infinitesimally small loans with probabilities of default G(l) and LGD = 100 percent.

The analogy of the CDO tranche with a portfolio of loans allows us to calculate the risk associated with the tranche as the sum of the risks of the “infinitesimally small loans.”

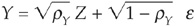

In order to calculate (regulatory) capital for the CDO tranche, Pykhtin and Dev assume that the tranche is held in a very diversified portfolio and that its relative size compared with that of the portfolio is negligible. The losses on the portfolio are driven by another normally distributed random variable, correlated to the common factor Y. The authors assume that the two factors satisfy

where ε is another idiosyncratic term.

The capital is the amount that would withstand losses on the portfolio with 1 − q percent probability (where q, for example, is equal to 1 percent). It is obtained by assuming that the realization of the risk factor Z is equal to it\s 1 − q percentile: z1−q, and calculating the probability of default of infinitely small loans conditional on the risk factor:

Pykhtin and Dev (2002) obtain a closed-form solution for this equation, only involving the bivariate normal distribution.

In a separate paper, Pykhtin and Dev (2003) lift assumption 1 above, which is frequently violated (the pool of assets will in many cases comprise only 30 to 50 issuers).