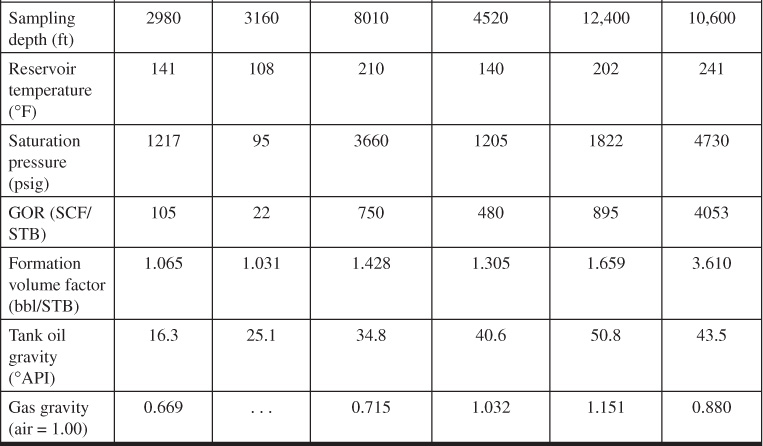

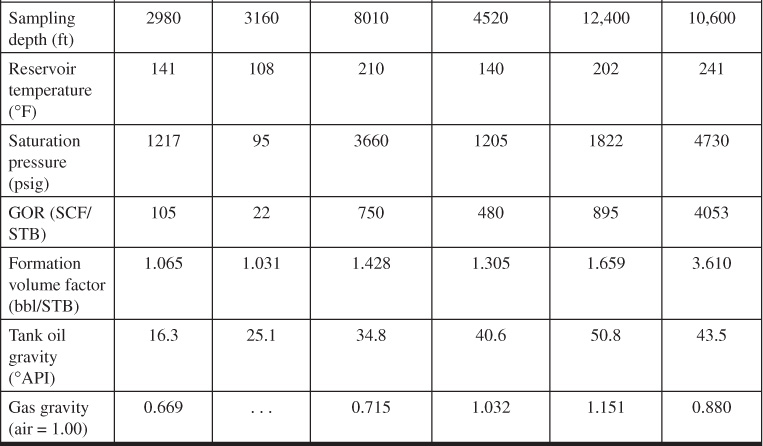

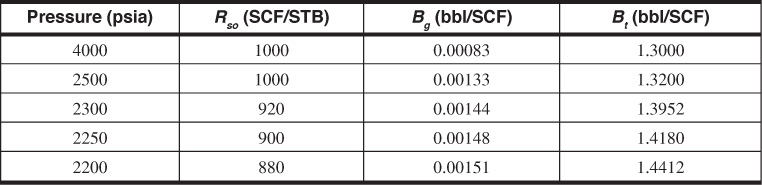

Table 6.1 Reservoir Fluid Compositions and Properties (after Kennerly, Courtesy Core Laboratories, Inc.)1

At the beginning of this text, the various hydrocarbon reservoirs were subdivided into four types. This chapter contains a discussion on reservoirs that have only liquid phases initially present. The next chapter will consider oil reservoirs that have an initial gas cap. These two reservoir types differ significantly from the gas reservoirs. The differences stem from the composition of the reservoir fluids and result in a distinct primary production method—that of depletion drive. Compared to volumetric gas drive, depletion drive is a weaker primary production method and more factors, such as rock and water compressibility, must be considered in order to accurately predict the behavior of the reservoir. The same method, the material balance, will be used in this prediction; it will, however, require additional terms.

Oil in place for oil reservoirs can be calculated in two ways. If available, well and seismic data can be used to calculate the oil in place using techniques like those explained in Chapter 4. Alternately, oil and gas production data combined with pressure and saturation data can be used in a material balance employing equations from Chapter 3.

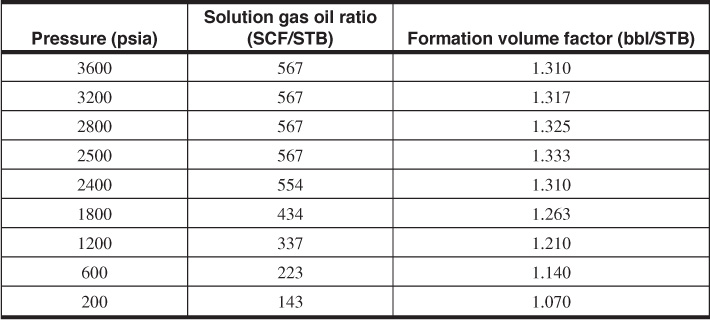

Oil reservoir fluids are mainly complex mixtures of the hydrocarbon compounds, which frequently contain impurities such as nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide. The composition in mole percentages of several typical reservoir liquids is given in Table 6.1, together with the tank gravity of the crude oil, the gas-oil ratio of the reservoir mixture, and other characteristics of the fluids.1 The composition of the tank oils obtained from the reservoir fluids are quite different from the composition of the reservoir fluids, owing mainly to the release of most of the methane and ethane from solution and the vaporization of sizeable fractions of the propane, butanes, and pentanes, as pressure is reduced in passing from the reservoir to the stock tank. The table shows a good correlation between the gas-oil ratios of the fluids and the percentages of methane and ethane they contain over a range of gas-oil ratios, from only 22 SCF/STB up to 4053 SCF/STB.

Table 6.1 Reservoir Fluid Compositions and Properties (after Kennerly, Courtesy Core Laboratories, Inc.)1

Several methods are available for collecting samples of reservoir fluids. The samples may be taken with subsurface sampling equipment lowered into the well on a wire line, or samples of the gas and oil may be collected at the surface and later recombined in proportion to the gas-oil ratio measured at the time of sampling. Samples should be obtained as early as possible in the life of the reservoir, preferably at the completion of the discovery well, so that the sample approaches as nearly as possible the original reservoir fluid. The type of fluid collected in a sampler is dependent on the well history prior to sampling. Unless the well has been properly conditioned before sampling, it is impossible to collect representative samples of the reservoir fluid. A complete well-conditioning procedure has been described by Kennedy and Reudelhuber.1,2 The information obtained from the usual fluid sample analysis includes the following properties:

1. Solution and evolved gas-oil ratios and liquid phase volumes

2. Formation volume factors, tank oil gravities, and separator and stock-tank gas-oil ratios for various separator pressures

3. Bubble-point pressure of the reservoir fluid

4. Compressibility of the saturated reservoir oil

5. Viscosity of the reservoir oil as a function of pressure

6. Fractional analysis of a casing head gas sample and of the saturated reservoir fluid

If laboratory data are not available, satisfactory estimations for a preliminary analysis can often be made from empirical correlations, like those considered in Chapter 2, that are based on data usually available. These data include the gravity of the tank oil, the specific gravity of the produced gas, the initial producing gas-oil ratio, the viscosity of the tank oil, the reservoir temperature, and the initial reservoir pressure.

In most reservoirs, the variations in the reservoir fluid properties among samples taken from different portions of the reservoir are not large, and they lie within the variations inherent in the techniques of fluid sampling and analysis. In some reservoirs, on the other hand, particularly those with large closures, there are large variations in the fluid properties. For example, in the Elk Basin Field, Wyoming and Montana, under initial reservoir conditions, there was 490 SCF of gas in solution per barrel of oil in a sample taken near the crest of the structure but only 134 SCF/STB in a sample taken on the flanks of the field, 1762 ft lower in elevation.3 This is a solution gas gradient of 20 SCF/STB per 100 ft of elevation. Because the quantity of solution gas has a large effect on the other fluid properties, large variations also occur in the fluid viscosity, the formation volume factor, and the like. Similar variations have been reported for the Weber sandstone reservoir of the Rangely Field, Colorado, and the Scurry Reef Field, Texas, where the solution gas gradients were 25 and 46 SCF/STB per 100 ft of elevation, respectively.4,5 These variations in fluid properties may be explained by a combination of (1) temperature gradients, (2) gravitational segregation, and (3) lack of equilibrium between the oil and the solution gas. Cook, Spencer, Bobrowski, and Chin, and McCord have presented methods for handling calculations when there are significant variations in the fluid properties.5,6

One of the important functions of the reservoir engineer is the periodic calculation of the reservoir oil (and gas) in place and the recovery anticipated under the prevailing reservoir mechanism(s). In some companies, this work is done by a group that periodically renders an account of the company’s reserves together with the rates at which they can be recovered in the future. The company’s financial position depends primarily on its reserves, the rate at which it increases or loses them, and the rates at which they can be recovered. A knowledge of the reserves and rates of recovery is also important in the sale or exchange of oil properties. The calculation of reserves of new discoveries is particularly important because it serves as a guide to sound development programs. Likewise, an accurate knowledge of the initial contents of reservoirs is invaluable to the reservoir engineer who studies the reservoir behavior with the aim of calculating and/or improving primary recoveries—for it eliminates one of the unknown quantities in equations.

Oil reserves are usually obtained by multiplying the oil in place by a recovery factor, where the recovery factor is the estimated fraction of the oil in place that will be produced through a particular production or reservoir drive mechanism. They can also be estimated from decline curve studies and by applying appropriate barrel-per-acre-foot recovery figures obtained from experience or statistical studies of well or reservoir production data. The oil in place is calculated either (1) by the use of geological, geophysical, and fluid property data or (2) by material balance studies, both of which were presented for gas reservoirs in Chapter 4 and will be given for oil reservoirs in this and following chapters. In the latter case, recovery factors are determined from (1) displacement efficiency studies and (2) correlations based on statistical studies of particular types of reservoir mechanisms.

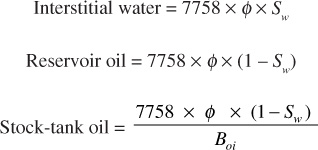

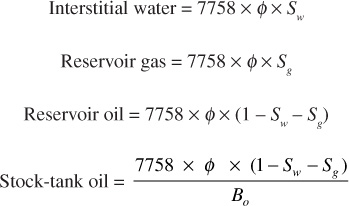

The first method for estimating oil in place starts with an estimate of the bulk reservoir volume using the techniques considered in Chapter 4. Then log and core analysis data are used to determine the bulk volume, porosity, and fluid saturations, and fluid analysis data are used to determine the oil volume factor. Under initial conditions, 1 ac-ft of bulk oil productive rock contains the following:

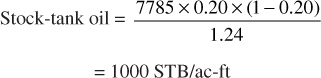

where 7758 barrels is the equivalent of 1 ac-ft, φ is the porosity as a fraction of the bulk volume, Sw is the interstitial water as a fraction of the pore volume, and Boi is the initial formation volume factor of the reservoir oil. Using somewhat average values (φ = 0.20, Sw = 0.20, and Boi = 1.24), the initial stock-tank oil in place per acre-foot is on the order of 1000 STB/ac-ft, or

For oil reservoirs under volumetric control, there is no water influx to replace the produced oil, so it must be replaced by the swelling of the oil phase or expanding gas, the saturation of which increases as the oil saturation decreases. If Sg is the gas saturation and Bo the oil volume factor at abandonment, then at abandonment conditions, 1 ac-ft of bulk rock contains the following:

Then the recovery in stock-tank barrels per acre-foot is

and the fractional recovery in terms of stock-tank barrels is

The total free gas saturation to be expected at abandonment can be estimated from the oil and water saturations as reported in core analysis.7 This expectation is based on the assumption that, while being removed from the well, the core is subjected to fluid removal by the expansion of the gas liberated from the residual oil and that this process is somewhat similar to the depletion process in the reservoir. In a study of the well-spacing problem, Craze and Buckley collected a large amount of statistical data on 103 oil reservoirs, 27 of which were considered to be producing under volumetric control.8,9 The final gas saturation in most of these reservoirs ranged from 20% to 40% of the pore space, with an average saturation of 30.4%. Recoveries may also be calculated for depletion performance from a knowledge of the properties of the reservoir rock and fluids.

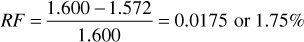

In the case of reservoirs under hydraulic control, where there is no appreciable decline in reservoir pressure, water influx is either inward and parallel to the bedding planes, as found in thin, relatively steep dipping beds (edgewater drive), or upward where the producing oil zone (column) is underlain by water (bottomwater drive). The oil remaining at abandonment in those portions of the reservoir invaded by water, in barrels per acre-foot, is as follows:

where Sor is the residual oil saturation remaining after water displacement. Since it was assumed that the reservoir pressure was maintained at its initial value by the water influx, no free gas saturation develops in the oil zone, and the oil volume factor at abandonment remains Boi. The recovery by active water drive then is

and the recovery factor is

It is generally believed that the oil content of cores, reported from the analysis of cores taken with a water-based drilling fluid, is a reasonable estimation of the unrecoverable oil because the core has been subjected to a partial water displacement (by the mud filtrate) during coring and to displacement by the expansion of the solution gas as the pressure on the core is reduced to atmospheric pressure.10 If this figure is used for the resident oil saturation in Eqs. (6.3) and (6.4), it should be increased by the formation volume factor. For example, a residual oil saturation of 20% from core analysis indicates a residual reservoir saturation of 30% for an oil volume factor of 1.50 bbl/STB. The residual oil saturation may also be estimated using the data of Table 4.2, which should be applicable to residual oil saturations as well as gas saturations (i.e., in the range of 25% to 40% for the consolidated sandstones studied).

In the reservoir analysis made by Craze and Buckley, some 70 of the 103 fields analyzed produced wholly or partially under water-drive conditions, and the residual oil saturations ranged from 17.9% to 60.9% of the pore space.8 According to Arps, the data apparently relate according to the reservoir oil viscosity and permeability.7 The average correlation between oil viscosity and residual oil saturation, both under reservoir conditions, is shown in Table 6.2. Also included in Table 6.2 is the deviation of this trend against average formation permeability. For example, the residual oil saturation under reservoir conditions for a formation containing 2 cp oil and having an average permeability of 500 md is estimated at 37 + 2, or 39% of the pore space.

Table 6.2 Correlation between Reservoir Oil Viscosity, Average Reservoir Permeability, and Residual Oil Saturation (after Craze and Buckley and Arps)7,8

Because Craze and Buckley’s data were arrived at by comparing recoveries from the reservoir as a whole with the estimated initial content, the residual oil calculated by this method includes a sweep efficiency as well as the residual oil saturation—that is, the figures are higher than the residual oil saturations in those portions of the reservoir invaded by water at abandonment. This sweep efficiency reflects the effect of well location, the bypassing of some of the oil in the less permeable strata, and the abandonment of some leases before the flooding action in all zones is complete, owing to excessive water-oil ratios, in both edgewater and bottomwater drives.

In a statistical study of Craze and Buckley’s water-drive recovery data, Guthrie and Greenberger, using multiple correlation analysis methods, found the following correlation between water-drive recovery and five variables that affect recovery in sandstone reservoirs.11

For k = 1000 md, Sw = 0.25, μo = 2.0 cp, φ = 0.20, and h = 10 ft,

RF = 0.114 + 0.272 × log 1000 + 0.256 × 0.25 – 0.136

log 2 – 1.538 × 0.20 – 0.00035 × 10

0.642, or 64.2% (of initial stock-tank oil)

where

RF = recovery factor

A test of the equation showed that 50% of the fields had recoveries within ± 6.2% recovery of that predicted by Eq. (6.5), 75% were within ± 9.0% recovery, and 100% were within ± 19.0% recovery. For instance, it is 75% probable that the recovery from the foregoing example is 64.2 ± 9.0%.

Although it is usually possible to determine a reasonably accurate recovery factor for a reservoir as a whole, the figure may be wholly unrealistic when applied to a particular lease or portion of a reservoir, owing to the problem of fluid migration in the reservoir, also referred to as lease drainage. For example, a flank lease in a water-drive reservoir may have 50,000 STB of recoverable stock-tank oil in place but will divide its reserve with all updip wells in line with it. The degree to which migration may affect the ultimate recoveries from various leases is illustrated in Fig. 6.1.12 If the wells are located on 40-acre units, if each well has the same daily allowable, if there is uniform permeability, and if the reservoir is under an active water drive so that the water advances along a horizontal surface, then the recovery from lease A is only one-seventh of the recoverable oil in place, whereas lease G recovers one-seventh of the recoverable oil under lease A, one-sixth under lease B, one-fifth under lease C, and so on. Lease drainage is generally less severe with other reservoir mechanisms, but it occurs to some extent in all reservoirs.

Figure 6.1 Effect of water drive on oil migration (after Buckley, AlME).12

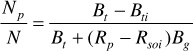

The material balance equation for undersaturated reservoirs was developed in Chapter 3:

Neglecting the change in porosity of rocks with the change of internal fluid pressure, which is treated later, reservoirs with zero or negligible water influx are constant volume or volumetric reservoirs. If the reservoir oil is initially undersaturated, then initially it contains only connate water and oil, with their solution gas. The solubility of gas in reservoir waters is generally quite low and is considered negligible for the present discussion. Because the water production from volumetric reservoirs is generally small or negligible, it will be considered zero. From initial reservoir pressure down to the bubble point, then, the reservoir oil volume remains a constant, and oil is produced by liquid expansion. Incorporating these assumptions into Eq. (3.8), the following is obtained:

While the reservoir pressure is maintained above the bubble-point pressure and the oil remains undersaturated, only liquid will exist in the reservoir. Any gas that is produced on the surface will be gas coming out of solution as the oil moves up through the wellbore and through the surface facilities. All this gas will be gas that was in solution at reservoir conditions. Therefore, during this period, Rp will equal Rso and Rso will equal Rsoi, since the solution gas-oil ratio remains constant (see Chapter 2). The material balance equation becomes

This can be rearranged to yield fractional recovery, RF, as

The fractional recovery is generally expressed as a fraction of the initial stock-tank oil in place. The pressure-volume-temperature (PVT) data for the 3–A–2 reservoir of a field is given in Fig. 6.2.

The formation volume factor plotted in Fig. 6.2 is the single-phase formation volume factor, Bo. The material balance equation has been derived using the two-phase formation volume factor, Bt. Bo and Bt are related by Eq. (2.29):

It should be apparent that Bt = Bo above the bubble-point pressure because Rso is constant and equal to Rsoi.

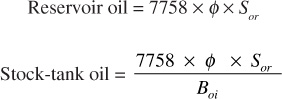

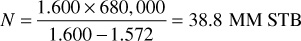

The reservoir fluid has an oil volume factor of 1.572 bbl/STB at the initial pressure 4400 psia and 1.600 bbl/STB at the bubble-point pressure of 3550 psia. Then, by volumetric depletion, the fractional recovery of the stock-tank oil at 3550 psia by Eq. (6.8) is

If the reservoir produced 680,000 STB when the pressure dropped at 3550 psia, then the initial oil in place by Eq. (6.7) is

Below 3550 psia, a free gas phase develops; and for a volumetric, undersaturated reservoir with no water production, the hydrocarbon pore volume remains constant, or

Figure 6.3 shows schematically the changes that occur between initial reservoir pressure and some pressure below the bubble point. The free-gas phase does not necessarily rise to form an artificial gas cap, and the equations are the same if the free gas remains distributed throughout the reservoir as isolated bubbles. Equation (6.6) can be rearranged to solve for N and the fractional recovery, RF, for any undersaturated reservoir below the bubble point.

Figure 6.3 Diagram showing the formation of a free-gas phase in a volumetric reservoir below the bubble point.

The net cumulative produced gas-oil ratio (Rp) is the quotient of all the gas produced from the reservoir (Gp) and all the oil produced (Np). In some reservoirs, some of the produced gas is returned to the same reservoir, so that the net produced gas is only that which is not returned to the reservoir. When all the produced gas is returned to the reservoir, Rp is zero.

An inspection of Eq. (6.11) indicates that all the terms except the produced gas-oil ratio (Rp) are functions of pressure only and are the properties of the reservoir fluid. Because the nature of the fluid is fixed, it follows that the fractional recovery RF is fixed by the PVT properties of the reservoir fluid and the produced gas-oil ratio. Since the produced gas-oil ratio occurs in the denominator of Eq. (6.11), large gas-oil ratios give low recoveries and vice versa.

Example 6.1 Calculating the Effect of the Produced Gas-Oil Ratio (Rp) on Fractional Recovery in Volumetric, Undersaturated Reservoirs

Given

The PVT data for the 3–A–2 reservoir (Fig. 6.2)

Cumulative GOR at 2800 psia = 3300 SCF/STB

Reservoir temperature = 190°F = 650°R

Standard conditions = 14.7 psia and 60°F

Solution

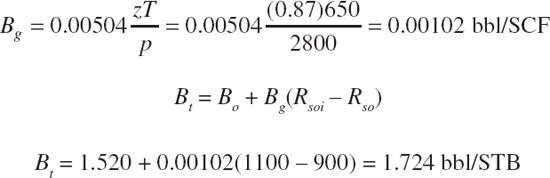

The following values are determined graphically from Fig 6.2. Rsoi is the GOR at the initial reservoir condition of p = 4400 psia and Rsoi = 1100 SCF/STB. Boi is the formation volume factor at initial reservoir conditions of p = 4400 psia and Boi = 1.572 bbl/STB. At 2800 psia, Rso is the GOR at 900 SCF/STB and Bo is the formation volume factor at 1.520 bbl/STB. Rp was given as the cumulative GOR at 2800 psia. Bg and Bt at 2800 psia are calculated as follows from Eqs. (2.16) and (2.29):

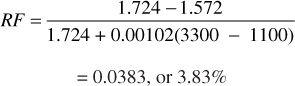

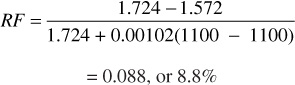

Then, using Eq. (6.11) at 2800 psia,

If two-thirds of the produced gas had been returned to the reservoir, at the same pressure (i.e., 2800 psia), Rp would be 1100 SCF/STB and the fractional recovery would have been

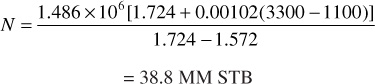

Equation (6.10) may be used to find the initial oil in place. For example, if 1.486 MM STB had been produced down to 2800 psia, for Rp = 3300 SCF/STB, the initial oil in place is

The calculations of Example 6.1 for the 3–A–2 reservoir show that, for Rp = 3300 SCF/STB, the recovery at 2800 psia is 3.83% and that, if Rp had been only 1100 SCF/STB, the recovery would have been 8.80%. Neglecting in each case the 1.75% recovery by liquid expansion down to the bubble-point pressure, the effect of reducing the gas-oil ratio by one-third is approximately to triple the recovery. The produced gas-oil ratio can be controlled by working over high gas-oil ratio wells, by shutting in or reducing the producing rates of high ratio wells, and/or by returning some or all of the produced gas to the reservoir. If gravitational segregation occurs during production so that a gas cap forms, as shown in Fig. 6.3, and if the producing wells are completed low in the formation, their gas-oil ratios will be lower and recovery will be improved. Simply from the material balance point of view, by returning all produced gas to the reservoir, it is possible to obtain 100% recoveries. From the point of view of flow dynamics, however, a practical limit is reached when the reservoir gas saturation rises to values in the range of 10% to 40% because the reservoir becomes so permeable to gas that the returned gas moves rapidly from the injection wells to the production wells, displacing with it only a small quantity of oil. Thus although gas-oil ratio control is important in solution gas-drive reservoirs, recoveries are inherently low because the gas is produced faster than the oil. Outside the energy stored up in the liquid above the bubble point, the energy for producing the oil is stored up in the solution gas. When this gas has been produced, the only remaining natural source of energy is gravity drainage, and there may be a considerable period in which the oil drains downward to the wells from which it is pumped to the surface.

In the next section, a method is presented that allows the material balance equation to be used as a predictive tool. The method was used by engineers performing calculations on the Canyon Reef Reservoir in the Kelly-Snyder Field.

The Canyon Reef reservoir of the Kelly-Snyder Field, Texas, was discovered in 1948. During the early years of production, there was much concern about the very rapid decline in reservoir pressure; however, reservoir engineers were able to show that this was to be expected of a volumetric undersaturated reservoir with an initial pressure of 3112 psig and a bubble-point pressure of only 1725 psig, both at a datum of 4300 ft subsea.13 Their calculations further showed that when the bubble-point pressure is reached, the pressure decline should be much less rapid, and that the reservoir could be produced without pressure maintenance for many years thereafter without prejudice to the pressure maintenance program eventually adopted. In the meantime, with additional pressure drop and production, further reservoir studies could evaluate the potentialities of water influx, gravity drainage, and intrareservoir communication. These, together with laboratory studies on cores to determine recovery efficiencies of oil by depletion and by gas and water displacement, should enable the operators to make a more prudent selection of the pressure maintenance program to be used or should demonstrate that a pressure maintenance program would not be successful.

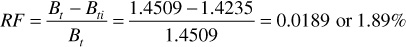

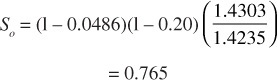

Although additional and revised data have become available in subsequent years, the following calculations, which were made in 1950 by reservoir engineers, are based on data available in 1950. Table 6.3 gives the basic reservoir data for the Canyon Reef reservoir. Geologic and other evidence indicated that the reservoir was volumetric (i.e., that there would be negligible water influx), so the calculations were based on volumetric behavior. If any water entry should occur, the effect would be to make the calculations more optimistic—that is, there would be more recovery at any reservoir pressure. The reservoir was undersaturated, so the recovery from initial pressure to bubble-point pressure is by liquid expansion and the fractional recovery at the bubble point is

Table 6.3 Reservoir Rock and Fluid Properties for the Canyon Reef Reservoir of the Kelly-Snyder Field, Texas (Courtesy The Oil and Gas Journal)14

Based on an initial content of 1.4235 reservoir barrels or 1.00 STB, this is recovery of 0.0189 STB. Because the solution gas remains at 885 SCF/STB down to 1725 psig, the producing gas-oil ratio and the cumulative produced gas-oil ratio should remain near 885 SCF/STB during this pressure decline.

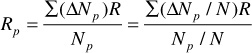

Below 1725 psig, a free gas phase develops in the reservoir. As long as this gas phase remains immobile, it can neither flow to the wellbores nor migrate upward to develop a gas cap but must remain distributed throughout the reservoir, increasing in size as the pressure declines. Because pressure changes much less rapidly with reservoir voidage for gases than for liquids, the reservoir pressure declines at a much lower rate below the bubble point. It was estimated that the gas in the Canyon Reef reservoir would remain immobile until the gas saturation reached a value near 10% of the pore volume. When the free gas begins to flow, the calculations become quite complex (see Chapter 10); but as long as the free gas is immobile, calculations may be made assuming that the producing gas-oil ratio R at any pressure will equal the solution gas-oil ratio Rso at the pressure, since the only gas that reaches the wellbore is that in solution, the free gas being immobile. Then the average producing (daily) gas-oil ratio between any two pressures p1 and p2 is approximately

and the cumulative gas-oil ratio at any pressure is

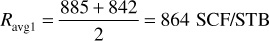

On the basis of 1.00 STB of initial oil, the production at bubble-point pressure Npb is 0.0189 STB. The average producing gas-oil ratio between 1725 and 1600 psig will be

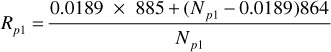

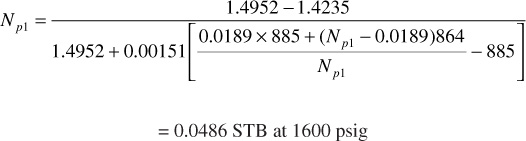

The cumulative recovery at 1600 psig Np1 is unknown; however, the cumulative gas-oil ratio Rp may be expressed by Eq. (6.13) as

This value of Rp1 may be placed in Eq. (6.11) together with the PVT values at 1600 psig as

In a similar manner, the recovery at 1400 psig may be calculated, the results being valid only if the gas saturation remains below the critical gas saturation, assumed to be 10% for the present calculations.

When Np stock-tank barrels of oil have been produced from a volumetric undersaturated reservoir and the average reservoir pressure is p, the volume of the remaining oil is (N – Np)Bo. Since the initial pore volume of the reservoir Vp is

and since the oil saturation is the oil volume divided by the pore volume,

On the basis of N = 1.00 STB initially, Np is the fractional recovery RF, or Np/N, and Eq. (6.15) can be written as

where Swi is the connate water, which is assumed to remain constant for volumetric reservoirs. Then at 1600 psig, the oil saturation is

The gas saturation is (1 –So – Swi), or

Sg = 1 – 0.765 – 0.200 = 0.035

Figure 6.4 shows the calculated performance of the Kelly-Snyder Field down to a pressure of 1400 psig. Calculations were not continued beyond this point because the free gas saturation had reached approximately 10%, the estimated critical gas saturation for the reservoir. The graph shows the rapid pressure decline above the bubble point and the predicted flattening below the bubble point. The predictions are in good agreement with the field performance, which is calculated in Table 6.4 using field pressures and production data, and a value of 2.25 MMM STB for the initial oil in place. The producing gas-oil ratio, column 2, increases instead of decreasing, as predicted by the previous theory. This is due to the more rapid depletion of some portions of the reservoir—for example, those drilled first, those of low net productive thickness, and those in the vicinity of the wellbores. For the present predictions, it is pointed out that the previous calculations would not be altered greatly if a constant producing gas-oil ratio of 885 SCF/STB (i.e., the initial dissolved ratio) had been assumed throughout the entire calculation.

Figure 6.4 Material balance calculations and performance, Canyon Reef reservoir, Kelly-Snyder Field.

Table 6.4 Recovery from Kelly-Snyder Canyon Reef Reservoir Based on Production Data and Measured Average Reservoir Pressures, and Assuming an Initial Oil Content of 2.25 MMM STB

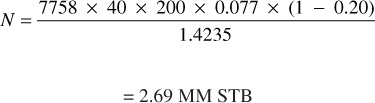

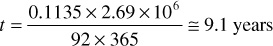

The initial oil under a 40-acre unit of the Canyon Reef reservoir for a net formation thickness of 200 feet is

Then, at the average daily well rate of 92 BOPD in 1950, the time to produce 11.35% of the initial oil (i.e., at 1400 psig when the gas saturation is calculated to be near 10%) is

By means of this calculation, the reservoir engineers were able to show that there was no immediate need for a curtailment of production and that there was plenty of time in which to make further reservoir studies and carefully considered plans for the optimum pressure maintenance program. Following comprehensive and exhaustive studies by engineers, the field was unitized in March 1953 and placed under the management of an operating committee. This group proceeded to put into operation a pressure maintenance program consisting of (1) water injection into wells located along the longitudinal axis of the field and (2) shutting in the high gas-oil ratio wells and transferring their allowables to low gas-oil ratio wells. The high-ratio wells were shut in as soon as the field was unitized, and water injection was started in 1954. The operation has gone as planned, and approximately 50% of the initial oil in place has been recovered, in contrast to approximately 25% by primary depletion, an increase of approximately 600 MM STB of recoverable oil.15

Many reservoirs are of the volumetric undersaturated type and their production, therefore, is controlled largely by the solution gas-drive mechanism. In many cases, the mechanism is altered to a greater or lesser extent by gravitational segregation of the gas and oil, by small water drives, and by pressure maintenance, all of which improve recovery. The important characteristics of this type of production may be summarized as follows and observed in the graph of Fig. 6.5 for the Gloyd-Mitchell zone of the Rodessa Field. Above the bubble point, the reservoir is produced by liquid expansion, and there is a rapid decline in reservoir pressure that accompanies the recovery of a fraction of 1% to a few percentage points of the initial oil in place. The gas-oil ratios remain low and generally near the value of the initial solution gas-oil ratio. Below the bubble point, a gas phase develops that, in most cases, is immobile until the gas saturation reaches the critical gas saturation in the range of a few percentage points to 20%. During this period, the reservoir produces by gas expansion, which is characterized by a much slower decline in pressure and gas-oil ratios near or in some cases even below the initial solution gas-oil ratio. After the critical gas saturation is reached, free gas begins to flow. This reduces the oil flow rate and depletes the reservoir of its main source of energy. By the time the gas saturation reaches a value usually in the range of 15% to 30%, the flow of oil is small compared with the gas (high gas-oil ratios), and the reservoir gas is rapidly depleted. At abandonment, the recoveries are usually in the range of 10% to 25% by the solution gas-drive mechanism alone, but they may be improved by gravitational segregation and the control of high gas-oil ratio wells.

Figure 6.5 Development, production, and reservoir pressure curves for the Gloyd-Mitchell zone, Rodessa Field, Louisiana.

The production of the Gloyd-Mitchell zone of the Rodessa Field, Louisiana, is a good example of a reservoir that produced during the major portion of its life by the dissolved gas-drive mechanism.16 Reasonably accurate data on this reservoir relating to oil and gas production, reservoir pressure decline, sand thickness, and the number of producing wells provide an excellent example of the theoretical features of the dissolved gas-drive mechanism. The Gloyd-Mitchell zone is practically flat and produced oil of 42.8 °API gravity, which, under the original bottom-hole pressure of 2700 psig, had a solution gas-oil ratio of 627 SCF/STB. There was no free gas originally present, and there is no evidence of an active water drive. The wells were produced at high rates and had a rapid decline in production. The behavior of the gas-oil ratios, reservoir pressures, and oil production had the characteristics expected of a dissolved gas drive, although there is some evidence that there was a modification of the recovery mechanism in the later stages of depletion. The ultimate recovery was estimated at 20% of the initial oil in place.

Many unsuccessful attempts were made to decrease the gas-oil ratios by shutting in the wells, by blanking off upper portions of the formation in producing wells, and by perforating only the lowest sand members. The failure to reduce the gas-oil ratios is typical of the dissolved gas-drive mechanism, because when the critical gas saturation is reached, the gas-oil ratio is a function of the decline in reservoir pressure or depletion and is not materially changed by production rate or completion methods. Evidently there was negligible gravitational segregation by which an artificial gas cap develops and causes abnormally high gas-oil ratios in wells completed high on the structure or in the upper portion of the formation.

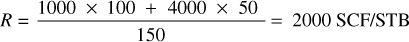

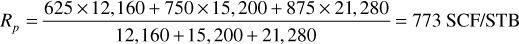

Table 6.5 gives the number of producing wells, average daily production, average gas-oil ratio, and average pressure for the Gloyd-Mitchell zone. The daily oil production per well, monthly oil production, cumulative oil production, monthly gas production, cumulative gas production, and cumulative gas-oil ratios have been calculated from these figures. The source of data is of interest. The number of producing wells at the end of any period is obtained either from the operators in the field, from the completion records as filed with the state regulatory body, or from the periodic potential tests. The average daily oil production is available from the monthly production reports filed with the state regulatory commission. Accurate values for the average daily gas-oil ratios can be obtained only when all the produced gas is metered. Alternatively, this information is obtained from the potential tests. To obtain the average daily gas-oil ratio from potential tests during any month, the gas-oil ratio for each well is multiplied by the daily oil allowable or daily production rate for the same well, giving the total daily gas production. The average daily gas-oil ratio for any month is the total daily gas production from all producing wells divided by the total daily oil production from all the wells involved. For example, if the gas-oil ratio of well A is 1000 SCF/STB and the daily rate is 100 bbl/day and the ratio of well B is 4000 SCF/STB and the daily rate is 50 bbl/day, then the average daily gas-oil ratio R of the two wells is

This figure is lower than the arithmetic average ratio of 2500 SCF/STB. The average gas-oil ratio of a large number of wells, then, can be expressed by

where R and qo are the individual gas-oil ratios and stock-tank oil production rates.

Figure 6.5 shows, plotted in block diagram, the number of producing wells, the daily gas-oil ratio, and the daily oil production per well. Also, in a smooth curve, pressure is plotted against time. The initial increase in daily oil production is due to the increase in the number of producing wells and not to the improvement in individual well rates. If all the wells had been completed and put on production at the same time, the daily production rate would have been a plateau, during the time all the wells could make their allowables, followed by an exponential decline, which is shown beginning at 16 months after the start of production. Since the daily oil allowable and daily production of a well are dependent on the bottom-hole pressure and gas-oil ratio, the oil recovery is larger for wells completed early in the life of a field. Because the controlling factor in this type of mechanism is gas flow in the reservoir, the rate of production has no material effect on the ultimate recovery, unless some gravity drainage occurs. Likewise, well spacing has no proven effect on recovery; however, well spacing and production rate directly affect the economic return.

The rapid increase in gas-oil ratios in the Rodessa Field led to the enactment of a gas-conservation order. In this order, oil and gas production were allocated partly on a volumetric basis to restrict production from wells with high gas-oil ratios. The basic ratio for oil wells was set at 2000 SCF/STB. For leases on which the wells produced more than 2000 SCF/STB, the allowable in barrels per day per well, based on acreage and pressure, was multiplied by 2000 and divided by the gas-oil ratio of the well. This cut in production produced a double hump in the daily production curve.

In addition to a graph showing the production history versus time, it is usually desirable to have a graph that shows the production history plotted versus the cumulative produced oil. Figure 6.6 is such a plot for the Gloyd-Mitchell zone data and is also obtained from Table 6.5. This graph shows some features that do not appear in the time graph. For example, a study of the reservoir pressure curve shows the Gloyd-Mitchell zone was producing by liquid expansion until approximately 200,000 bbl were produced. This was followed by a period of production by gas expansion with a limited amount of free gas flow. When approximately 3 million bbl had been produced, the gas began to flow much more rapidly than the oil, resulting in a rapid increase in the gas-oil ratio. In the course of this trend, the gas-oil ratio curve reached a maximum, then declined as the gas was depleted and the reservoir pressure approached zero. The decline in gas-oil ratio beginning after approximately 4.5 million bbl were produced was due mainly to the expansion of the flowing reservoir gas as pressure declined. Thus the same gas-oil ratio in standard cubic feet per day gives approximately twice the reservoir flow rate at 400 psig as at 800 psig; hence, the surface gas-oil ratio may decline and yet the ratio of the rate of flow of gas to the rate of flow of oil under reservoir conditions continues to increase. It may also be reduced by the occurrence of some gravitational segregation and also, from a quite practical point of view, by the failure of operators to measure or report gas production on wells producing fairly low volumes of low-pressure gas.

Figure 6.6 History of the Gloyd-Mitchell zone of the Rodessa Field plotted versus cumulative recovery.

The results of a differential gas-liberation test on a bottom-hole sample from the Gloyd zone show that the solution gas-oil ratio was 624 SCF/STB, which is in excellent agreement with the initial producing gas-oil ratio of 625 SCF/STB.17 In the absence of gas-liberation tests on a bottom-hole sample, the initial gas-oil ratio of a properly completed well in either a dissolved gas drive, gas cap drive, or water-drive reservoir is usually a reliable value to use for the initial solution gas-oil ratio of the reservoir. As can be seen in Fig. 6.6, the extrapolations of the pressure, oil rate, and producing gas-oil ratio curves on the cumulative oil plot all indicate an ultimate recovery of about 7 million bbl. However, no such extrapolation can be made on the time plot (see Fig. 6.5). It is also of interest that, whereas the daily producing rate is exponential on the time plot, it is close to a straight line on the cumulative oil plot.

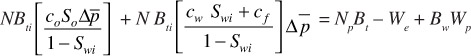

The average gas-oil ratio during any production interval and the cumulative gas-oil ratio may be indicated by integrals and shaded areas on a typical daily gas-oil ratio versus cumulative stock-tank oil production curve, as shown in Fig. 6.7. If R represents the daily gas-oil ratio at any time, and Np the cumulative stock-tank production at the same time, then the production during a short interval of time is dNp and the total volume of gas produced during that production interval is R dNp. The gas produced over a longer period when the gas-oil ratio is changing is given by

The shaded area between Npl and Np2 is proportional to the gas produced during the interval. The average daily gas-oil ratio during the production interval equals the area under the gas-oil ratio curve between Npl and Np2 in units given by the coordinate scales, divided by the oil produced in the interval (Np2 – Np1), and

The cumulative gas-oil ratio, Rp, is the total net gas produced up to any period divided by the total oil produced up to that period, or

The cumulative produced gas-oil ratio was calculated in this manner in column 11 of Table 6.5. For example, at the end of the third period,

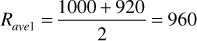

In Chapter 2, it was shown that both formation and water compressibilities are functions of pressure. This suggests that there are in fact no volumetric reservoirs—that is, those in which the hydrocarbon pore volume of the reservoir remains constant. Hall showed the magnitude of the effect of formation compressibility on volumetric reservoir calculations.18 The term volumetric, however, is retained to indicate those reservoirs in which there is no water influx but in which volumes change slightly with pressure, due to the effects just mentioned.

The effect of compressibilities above the bubble point on calculations for N are examined first. Equation (3.8), with Rp = Rsoi above the bubble point, becomes

This equation may be rearranged to solve for N:

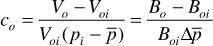

Although this equation is entirely satisfactory, often an oil compressibility, co, is introduced with the following defining relationship:

and

The definition of co uses the single-phase formation volume factor, but it should be apparent that as long as the calculations are being conducted above the bubble point, Bo = Bt. If Eq. (6.23) is substituted into the first term in Eq. (6.21), the result is

Multiplying both the numerator and the denominator of the term containing co by So and realizing that above the bubble point there is no gas saturation, So = 1 – Swi, Eq. (6.24) becomes

or

The expression in brackets of Eq. (6.25) is called the effective fluid compressibility, ce, which includes the compressibilities of the oil, the connate water, and the formation, or

Finally, Eq. (6.25) may be written as

For volumetric reservoirs, We = 0 and Wp is generally negligible, and Eq. (6.27) can be rearranged to solve for N:

Finally, if the formation and water compressibilities, cf and cw, both equal zero, then ce is simply co and Eq. (6.28) reduces to Eq. (6.8), derived in section 6.3 for production above the bubble point.

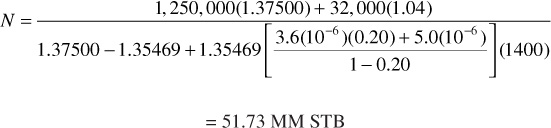

Example 6.3 shows the use of Eqs. (6.22) and (6.28) to find the initial oil in place from the pressure-production data of a reservoir that all geologic evidence indicates is volumetric (i.e., it is bounded on all sides by impermeable rocks). Because the equations are basically identical, they give the same calculation of initial oil, 51.73 MM STB. A calculation is also included to show that an error of 61% is introduced by neglecting the formation and water compressibilities.

Example 6.2 Calculating Initial Oil in Place in a Volumetric, Undersaturated Reservoir

Given

Bti = 1.35469 bbl/STB

Bt at 3600 psig = 1.37500 bbl/STB

Connate water = 0.20

cw = 3.6 (10)–6 psi–1

Bw at 3600 psig = 1.04 bbl/STB

cf = 5.0 (10)–6 psi–1

pi = 5000 psig

Np = 1.25 MM STB

Δ at 3600 psig = 1400 psi

at 3600 psig = 1400 psi

Wp = 32,000 STB

We = 0

Solution

Substituting into Eq. (6.22)

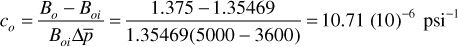

the average compressibility of the reservoir oil is

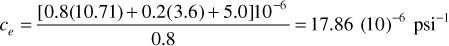

and the effective fluid compressibility by Eq. (6.26) is

Then the initial oil in place by Eq. (6.28) with the Wp term from Eq. (6.27) included is

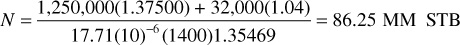

If the water and formation compressibilities are neglected, ce = co, and the initial oil in place is calculated to be

As can be seen from the example calculations, the inclusion of the compressibility terms significantly affects the value of N. This is true above the bubble point where the oil-producing mechanism is depletion, or the swelling of reservoir fluids. After the bubble point is reached, the water and rock compressibilities have a much smaller effect on the calculations because the gas compressibility is so much greater.

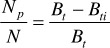

When Eq. (3.8) is rearranged and solved for N, we get the following:

This is the general material balance equation written for an undersaturated reservoir below the bubble point. The effects of water and formation compressibilities are accounted for in this equation. Example 6.3 compares the calculations for recovery factor, Np/N, for an undersaturated reservoir with and without including the effects of the water and formation compressibilities.

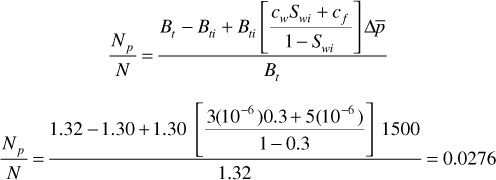

Example 6.3 Calculating Np/N for an Undersaturated Reservoir with No Water Production and Negligible Water Influx

Note the calculation is performed with and without including the effect of compressibilities. Assume that the critical gas saturation is not reached until after the reservoir pressure drops below 2200 psia.

Given

pi = 4000 psia

cw = 3 × 10–6 psi–1

pb = 2500 psia

cf = 5 × 10–6 psi–1

Sw = 30%

φ = 10%

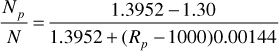

The calculations are performed first by including the effect of compressibilities. Equation (6.22), with Wp equal to zero and We neglected, is then rearranged and used to calculate the recovery at the bubble point.

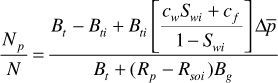

Below the bubble point, Eqs. (6.29) and (6.13) are used to calculate the recovery:

and

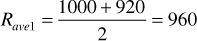

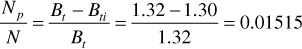

During the pressure increment 2500–2300 psia, the calculations yield

where Rave1 equals the average value of the solution GOR during the pressure increment.

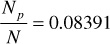

Solving these three equations for Np/N yields

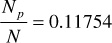

Repeating the calculations for the pressure increment 2250–2200 psia, the Np/N is found to be

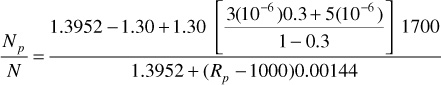

Now, the calculations are performed by assuming that the effect of including the compressibility terms is negligible. For this case, at the bubble point, the recovery can be calculated by using Eq. (6.8):

Below the bubble point, Eqs. (6.11) and (6.13) are used to calculate Np/N

and

For the pressure increment 2500–2300 psia,

where Rave1 is given by

Solving these three equations yields

Repeating the calculations for the pressure increment 2300–2250 psia,

For the pressure increment 2250–2200 psia,

Figure 6.8 is a plot of the results for the two different cases—that is, with and without considering the compressibility term.

Figure 6.8 Pressure versus fractional recovery for the calculations of Problem 6.4

The calculations suggest there is a very significant difference in the results of the two cases, down to the bubble point. The difference is the result of the fact that the rock and water compressibilities are on the same order of magnitude as the oil compressibility. By including them, the fractional recovery has been significantly affected. The case that used the rock and water compressibilities comes closer to simulating real production above the bubble point from this type of reservoir. This is because the actual mechanism of oil production is the expansion of the oil, water, and rock phases; there is no free gas phase.

Below the bubble point, the magnitude of the fractional recoveries calculated by the two schemes still differ by about what the difference was at the bubble point, suggesting that below the bubble point, the compressibility of the gas phase is so large that the water and rock compressibilities do not contribute significantly to the calculated fractional recoveries. This corresponds to the actual mechanism of oil production below the bubble point, where gas is coming out of solution and free gas is expanding as the reservoir pressure declines.

The results of the calculations of Example 6.4 are meant to help the reader to understand the fundamental production mechanisms that occur in undersaturated reservoirs. They are not meant to suggest that the calculations can be made easier by ignoring terms in equations for particular reservoir situations. The calculations are relatively easy to perform, whether or not all terms are included. Since nearly all calculations are conducted with the use of a computer, there is no need to neglect terms from the equations.

6.1 Using the letter symbols for reservoir engineering, write expressions for the following terms for a volumetric, undersaturated reservoir:

(a) The initial reservoir oil in place in stock-tank barrels

(b) The fractional recovery after producing Np STB

(c) The volume occupied by the remaining oil (liquid) after producing Np STB

(d) The SCF of gas produced

(e) The SCF of initial gas

(f) The SCF of gas in solution in the remaining oil

(g) By difference, the SCF of escaped or free gas in the reservoir after producing Np STB

(h) The volume occupied by the escaped, or free, gas

6.2 The physical characteristics of the 3–A–2 reservoir are given in Fig. 6.2:

(a) Calculate the percentage of recovery, assuming this reservoir could be produced at a constant cumulative produced gas-oil ratio of 1100 SCF/STB, when the pressure falls to 3550, 2800, 2000, 1200, and 800 psia. Plot the percentage of recovery versus pressure.

(b) To demonstrate the effect of increased GOR on recovery, recalculate the recoveries, assuming that the cumulative produced GOR is 3300 SCF/STB. Plot the percentage of recovery versus pressure on the same graph used for the previous problem.

(c) To a first approximation, what does tripling the produced GOR do to the percentage of recovery?

(d) Does this make it appear reasonable that, to improve recovery, high-ratio (GOR) wells should be worked over or shut in when feasible?

6.3 If 1 million STB of oil have been produced from the 3–A–2 reservoir at a cumulative produced GOR of 2700 SCF/STB, causing the reservoir pressure to drop from the initial reservoir pressure of 4400 psia to 2800 psia, what is the initial stock-tank oil in place?

6.4 The following data are taken from an oil field that had no original gas cap and no water drive:

Oil pore volume of reservoir = 75 MM ft3

Solubility of gas in crude = 0.42 SCF/STB/psi

Initial bottom-hole pressure = 3500 psia

Bottom-hole temperature = 140°F

Bubble-point pressure of the reservoir = 2400 psia

Formation volume factor at 3500 psia = 1.333 bbl/STB

Compressibility factor of the gas at 1500 psia and 140°F = 0.95

Oil produced when pressure is 1500 psia = 1.0 MM STB

Net cumulative produced GOR = 2800 SCF/STB

(a) Calculate the initial STB of oil in the reservoir.

(b) Calculate the initial SCF of gas in the reservoir.

(c) Calculate the initial dissolved GOR of the reservoir.

(d) Calculate the SCF of gas remaining in the reservoir at 1500 psia.

(e) Calculate the SCF of free gas in the reservoir at 1500 psia.

(f) Calculate the gas volume factor of the escaped gas at 1500 psia at standard conditions of 14.7 psia and 60°F.

(g) Calculate the reservoir volume of the free gas at 1500 psia.

(h) Calculate the total reservoir GOR at 1500 psia.

(i) Calculate the dissolved GOR at 1500 psia.

(j) Calculate the liquid volume factor of the oil at 1500 psia.

(k) Calculate the total, or two-phase, oil volume factor of the oil and its initial complement of dissolved gas at 1500 psia.

6.5 (a) Continuing the calculations of the Kelly-Snyder Field, calculate the fractional recovery and the gas saturation at 1400 psig.

(b) What is the deviation factor for the gas at 1600 psig and 125°F?

6.6 The R Sand is a volumetric oil reservoir whose PVT properties are shown in Fig. 6.9. When the reservoir pressure dropped from an initial pressure of 2500 psia to an average pressure of 1600 psia, a total of 26.0 MM STB of oil was produced. The cumulative GOR at 1600 psia is 954 SCF/STB, and the current GOR is 2250 SCF/STB. The average porosity for the field is 18%, and average connate water is 18%. No appreciable amount of water was produced, and standard conditions were 14.7 psia and 60°F.

(a) Calculate the initial oil in place.

(b) Calculate the SCF of evolved gas remaining in the reservoir at 1600 psia.

(c) Calculate the average gas saturation in the reservoir at 1600 psia.

(d) Calculate the barrels of oil that would have been recovered at 1600 psia if all the produced gas had been returned to the reservoir.

(e) Calculate the two-phase volume factor at 1600 psia.

(f) Assuming no free gas flow, calculate the recovery expected by depletion drive performance down to 2000 psia.

(g) Calculate the initial SCF of free gas in the reservoir at 2500 psia.

6.7 If the reservoir of Problem 6.6 had been a water-drive reservoir, in which 25 × 106 bbl of water had encroached into the reservoir when the pressure had fallen to 1600 psia, calculate the initial oil in place. Use the same current and cumulative GORs, the same PVT data, and assume no water production.

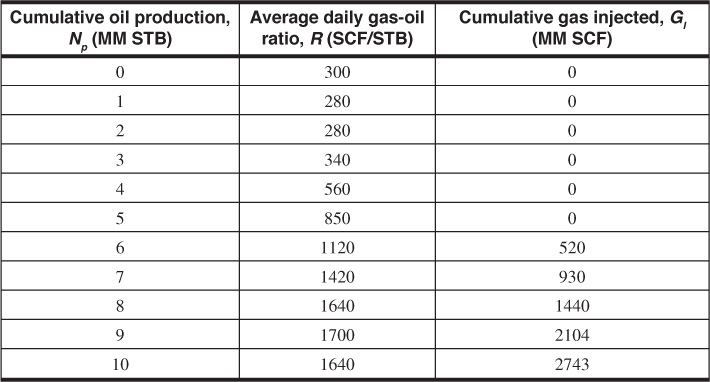

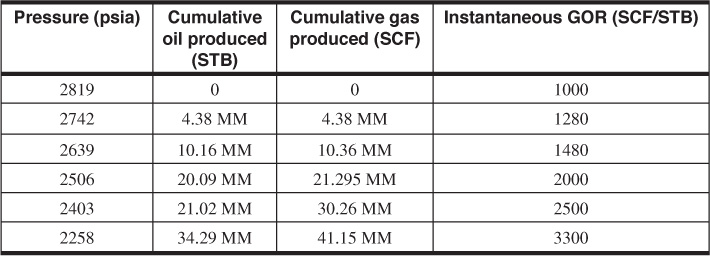

6.8 The following production and gas injection data pertain to a reservoir.

(a) Calculate the average producing GOR during the production interval from 6 MM STB to 8 MM STB.

(b) What is the cumulative produced GOR when 8 MM STB has been produced?

(c) Calculate the net average producing GOR during the production interval from 6 MM STB to 8 MM STB.

(d) What is the net cumulative produced GOR when 8 MM STB has been produced?

(e) Plot on the same graph the average daily GOR, the cumulative produced gas, the net cumulative produced gas, and the cumulative injected gas versus cumulative oil production.

6.9 An undersaturated reservoir producing above the bubble point had an initial pressure of 5000 psia, at which pressure the oil volume factor was 1.510 bbl/STB. When the pressure dropped to 4600 psia, owing to the production of 100,000 STB of oil, the oil volume factor was 1.520 bbl/STB. The connate water saturation was 25%, water compressibility 3.2 × 10–6 psi–1, and based on an average porosity of 16%, the rock compressibility was 4.0 × 10–6 psi–1. The average compressibility of the oil between 5000 and 4600 psia relative to the volume at 5000 psia was 17.00 × 10–6 psi–1.

(a) Geologic evidence and the absence of water production indicated a volumetric reservoir. Assuming this was so, what was the calculated initial oil in place?

(b) It was desired to inventory the initial stock-tank barrels in place at a second production interval. When the pressure had dropped to 4200 psia, formation volume factor 1.531 bbl/STB, 205 M STB had been produced. If the average oil compressibility was 17.65 × 10–6 psi–1, what was the initial oil in place?

(c) When all cores and logs had been analyzed, the volumetric estimate of the initial oil in place was 7.5 MM STB. If this figure is correct, how much water entered the reservoir when the pressure declined to 4600 psia?

6.10 Estimate the fraction recovery from a sandstone reservoir by water drive if the permeability is 1500 md, the connate water is 20%, the reservoir oil viscosity is 1.5 cp, the porosity is 25%, and the average formation thickness is 50 ft.

6.11 The following PVT data are available for a reservoir, which from volumetric reserve estimation is considered to have 275 MM STB of oil initially in place. The original pressure was 3600 psia. The current pressure is 3400 psia, and 732,800 STB have been produced. How much oil will have been produced by the time the reservoir pressure is 2700 psia?

6.12 Production data, along with reservoir and fluid data, for an undersaturated reservoir follow. There was no measurable water produced, and it can be assumed that there was no free gas flow in the reservoir. Determine the following:

(a) Saturations of oil, gas, and water at a reservoir pressure of 2258.

(b) Has water encroachment occurred and, if so, what is the volume?

Gas specific gravity = 0.78

Reservoir temperature = 160°F

Initial water saturation = 25%

Original oil in place = 180 MM STB

Bubble-point pressure = 2819 psia

The following expressions for Bo and Rso, as functions of pressure, were determined from laboratory data:

Bo = 1.00 + 0.00015p (in bbl/STB)

Rso = 50 + 0.42p (in SCF/STB)

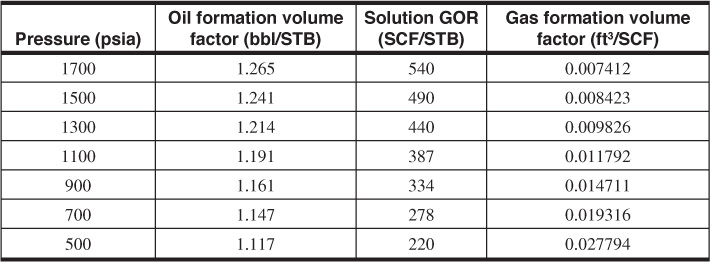

6.13 The following table provides fluid property data for an initially undersaturated lens type of oil reservoir. The initial connate water saturation was 25%. Initial reservoir temperature and pressure were 97°F and 2110 psia, respectively. The bubble-point pressure was 1700 psia. Average compressibility factors between the initial and bubble-point pressures were 4.0 × 10–6 psi–1 and 3.1 × 10–6 psi–1 for the formation and water, respectively. The initial oil formation volume factor was 1.256 bbl/STB. The critical gas saturation is estimated to be 10%. Determine the recovery versus pressure curve for this reservoir.

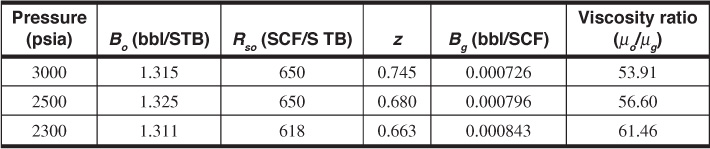

6.14 The Wildcat reservoir was discovered in 1970. The reservoir had an initial pressure of 3000 psia, and laboratory data indicated a bubble-point pressure of 2500 psia. The connate water saturation was 22%. Calculate the fractional recovery, Np/N, from initial conditions down to a pressure of 2300 psia. State any assumptions you make relative to the calculations.

Porosity = 0.165

Formation compressibility = 2.5 × 10–6 psi–1

Reservoir temperature = 150°F

1. T. L. Kennerly, “Oil Reservoir Fluids (Sampling, Analysis, and Application of Data),” presented before the Delta Section of AlME, Jan. 1953 (available from Core Laboratories, Inc., Dallas).

2. Frank O. Reudelhuber, “Sampling Procedures for Oil Reservoir Fluids,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (Dec. 1957), 9, 15–18.

3. Ralph H. Espach and Joseph Fry, “Variable Characteristics of the Oil in the Tensleep Sandstone Reservoir, Elk Basin Field, Wyoming and Montana,” Trans. AlME (1951), 192, 75.

4. Cecil Q. Cupps, Philip H. Lipstate Jr., and Joseph Fry, “Variance in Characteristics in the Oil in the Weber Sandstone Reservoir, Rangely Field, Colo.,” US Bureau of Mines R.I. 4761, U.S.D.I., Apr. 1951; see also World Oil (Dec. 1957), 133, No. 7, 192.

5. A. B. Cook, G. B. Spencer, F. P. Bobrowski, and Tim Chin, “A New Method of Determining Variations in Physical Properties of Oil in a Reservoir, with Application to the Scurry Reef Field, Scurry County, Tex,” US Bureau of Mines R.I. 5106, U.S.D.I., Feb. 1955, 12–23.

6. D. R. McCord, “Performance Predictions Incorporating Gravity Drainage and Gas Cap Pressure Maintenance—LL-370 Area, Bolivar Coastal Field,” Trans. AlME (1953), 198, 232.

7. J. J. Arps, “Estimation of Primary Oil Reserves,” Trans. AlME (1956), 207, 183–86.

8. R. C. Craze and S. E. Buckley, “A Factual Analysis of the Effect of Well Spacing on Oil Recovery,” API Drilling and Production Practice (1945), 144–55.

9. J. J. Arps and T. G. Roberts, “The Effect of Relative Permeability Ratio, the Oil Gravity, and the Solution Gas-Oil Ratio on the Primary Recovery from a Depletion Type Reservoir,” Trans. AlME (1955), 204, 120–26.

10. H. G. Botset and M. Muskat, “Effect of Pressure Reduction upon Core Saturation,” Trans. AlME (1939), 132, 172–83.

11. R. K. Guthrie and Martin K. Greenberger, “The Use of Multiple Correlation Analyses for Interpreting Petroleum-Engineering Data,” API Drilling and Production Practice (1955), 135–37.

12. Stewart E. Buckley, Petroleum Conservation, American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers, 1951, 239.

13. K. B. Barnes and R. F. Carlson, “Scurry Analysis,” Oil and Gas Jour. (1950), 48, No. 51, 64.

14. “Material-Balance Calculations, North Snyder Field Canyon Reef Reservoir,” Oil and Gas Jour. (1950), 49, No. 1, 85.

15. R. M. Dicharry, T. L. Perryman, and J. D. Ronquille, “Evaluation and Design of a CO2 Miscible Flood Project—SACROC Unit, Kelly-Snyder Field,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology, Nov. 1973, 1309–18.

16. Petroleum Reservoir Efficiency and Well Spacing, Standard Oil Development Company, 1943, 22.

17. H. B. Hill and R. K. Guthrie, “Engineering Study of the Rodessa Oil Field in Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas,” US Bureau of Mines R.I. 3715, 1943, 87.

18. Howard N. Hall, “Compressibility of Reservoir Rocks,” Trans. AlME (1953), 198, 309.