As fluid from a reservoir is produced and brought to the surface, the fluid remaining in the reservoir experiences changes in the reservoir conditions. The produced fluid also experiences changes as it is brought to the surface. The reservoir fluid typically sees only a decrease in pressure, while the produced fluid will experience decreases in pressure and in temperature. As the pressure decreases, it is common to observe gas that had been dissolved in the oil or water be liberated. Reservoir engineers use terms, such as the solution gas-oil ratio (Rso), to account for this. There are many variations on this term. R is generally used to denote any ratio, while the subscripts denote which ratio is being used. Rsoi, for example, is the initial gas-oil ratio, and Rsw is the solution gas-water ratio.

As the fluid is produced from the reservoir, the pressure on the rock from the overburden or the rock above it remains constant but the pressure of the fluid surrounding it is decreasing. This leads the rock to expand or the pores in the rock to be compressed. This change in pore volume due to pressure is called the pore volume compressibility (cf). The compressibility of the gas is also of interest. The gas compressibility (cg) involves a compressibility factor (z). The compressibility factor is simply a ratio of how the gas would behave ideally compared to how it behaves in actuality. The compressibility of oil (co) and water (cw) can also be determined, but their magnitude is far less than that of the gas. The determination of each of these properties, as well as those defined in Chapter 1, is critical in predicting the performance of a reservoir. This chapter contains a discussion of the pertinent rock and fluid properties with which a reservoir engineer will work.

Properties discussed in this section include porosity, isothermal compressibility, and fluid saturation. Although permeability is a property of a rock matrix, because of its importance in fluid flow calculations, a discussion of permeability is postponed until Chapter 8, in which single-phase fluid flow is considered.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the porosity of a porous medium is given the symbol of φ and is defined as the ratio of void space, or pore volume, to the total bulk volume of the rock. This ratio is expressed as either a fraction or a percentage. When using a value of porosity in an equation, it is nearly always expressed as a fraction. The term hydrocarbon porosity refers to that part of the porosity that contains hydrocarbon. It is the total porosity multiplied by the fraction of the pore volume that contains hydrocarbon. Porosity values range from 10% to 40% for sandstone type reservoirs and 5% to 15% for limestone type reservoirs.1

The value of porosity is usually reported as either a total or an effective porosity, depending on the type of measurement used. The total porosity represents the total void space of the medium. The effective porosity is the amount of the void space that contributes to the flow of fluids. This is the type of porosity usually measured in the laboratory and used in calculations of fluid flow.

The laboratory methods of measuring porosity include Boyle’s law, water saturation, and organic-liquid saturation methods. Dotson, Slobod, McCreery, and Spurlock have described a porosity-check program made by 5 laboratories on 10 samples.2 The average deviation of porosity from the average values was ±0.5% porosity. The accuracy of the average porosity of a reservoir as found from core analysis depends on the quality and quantity of the data available and on the uniformity of the reservoir. The average porosity is seldom known more precisely than to 1% porosity (e.g., to 5% accuracy at 20% porosity). The porosity is also calculated from indirect methods using well log data, often with the assistance of some core measurements. Ezekwe discusses the use of various types of well logs in the calculation of porosity.3 Logging techniques have the advantage of averaging larger volumes of rock than in core analysis. When calibrated with core data, they should provide average porosity figures in the same range of accuracy as core analysis. When there are variations in porosity across the reservoir, the average porosity should be found on a volume-weighted basis. In highly fractured, rubblized, or vuggy carbonate reservoirs, the highest porosity rock may be neither cored nor logged, and hydrocarbon volumes based on core or log porosity averages may be grossly underestimated.

The isothermal compressibility for a substance is given by the following equation:

where

c = isothermal compressibility

V = volume

p = pressure

The equation describes the change in volume that a substance undergoes during a change in pressure while the temperature is held constant. The units are in reciprocal pressure units. When the internal fluid pressure within the pore spaces of a rock, which is subjected to a constant external (rock or overburden) pressure, is reduced, the bulk volume of the rock decreases while the volume of the solid rock material (e.g., the sand grains of a sandstone) increases. Both volume changes act to reduce the porosity of the rock slightly, of the order of 0.5% for a 1000-psi change in the internal fluid pressure (e.g., at 20% porosity to 19.9%).

Studies by van der Knaap indicate that this change in porosity for a given rock depends only on the difference between the internal and external pressures and not on the absolute value of the pressures.4 As with the volume of reservoir coils above the bubble point, however, the change in pore volume is nonlinear and the pore volume compressibility is not constant. The pore volume compressibility (cf) at any value of external-internal pressure difference may be defined as the change in pore volume per unit of pore volume per unit change in pressure. The values for limestone and sandstone reservoir rocks lie in the range of 2 × 10–6 to 25 × 10–6 psi–1. If the compressibility is given in terms of the change in pore volume per unit of bulk volume per unit change in pressure, dividing by the fractional porosity places it on a pore volume basis. For example, a compressibility of 1.0 × 10–6 pore volume per bulk volume per psi for a rock of 20% porosity is 5.0 × 10–6 pore volume per pore volume per psi.

Newman measured isothermal compressibility and porosity values in 79 samples of consolidated sandstones under hydrostatic pressure.5 When he fit the data to a hyperbolic equation, he obtained the following correlation:

This correlation was developed for consolidated sandstones having a range of porosity values from 0.02 < φ < 0.23. The average absolute error of the correlation over the entire range of porosity values was found to be 2.60%.

Newman also developed a similar correlation for limestone formations under hydrostatic pressure.5 The range of porosity values included in the correlation was 0.02 < φ < 0.33, and the average absolute error was found to be 11.8%. The correlation for limestone formations is as follows:

Even though the rock compressibilities are small figures, their effect may be important in some calculations on reservoirs or aquifers that contain fluids of compressibilities in the range of 3 to 25(10)–6 psi–1. One application is given in Chapter 6 involving calculations above the bubble point. Geertsma points out that when the reservoir is not subjected to uniform external pressure, as are the samples in the laboratory tests of Newman, the effective value in the reservoir will be less than the measured value.6

The ratio of the volume that a fluid occupies to the pore volume is called the saturation of that fluid. The symbol for oil saturation is So, where S refers to saturation and the subscript o refers to oil. Saturation is expressed as either a fraction or a percentage, but it is used as a fraction in equations. The saturations of all fluids present in a porous medium add to 1.

There are, in general, two ways of measuring original fluid saturations: the direct approach and the indirect approach. The direct approach involves either the extraction of the reservoir fluids or the leaching of the fluids from a sample of the reservoir rock. The indirect approach relies on a measurement of some other property, such as capillary pressure, and the derivation of a mathematical relationship between the measured property and saturation.

Direct methods include retorting the fluids from the rock, distilling the fluids with a modified American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) procedure, and centrifuging the fluids. Each method relies on some procedure to remove the rock sample from the reservoir. Experience has found that it is difficult to remove the sample without altering the state of the fluids and/or rock. The indirect methods use logging or capillary pressure measurements. With either method, errors are built into the measurement of saturation. However, under favorable circumstances and with careful attention to detail, saturation values can be obtained within useful limits of accuracy. Ezekwe presents models and equations used in the calculation of saturation values for both direct and indirect methods.3

Relationships that describe the pressure-volume-temperature (PVT) behavior of gases are called equations of state. The simplest equation of state is called the ideal gas law and is given by

where

p = absolute pressure

V = total volume that the gas occupies

n = moles of gas

T = absolute temperature

R′ = gas constant

When R′ = 10.73, p must be in pounds per square inch absolute (psia), V in cubic feet (ft3), n in pound-moles (lb-mols), and T in degrees Rankine (°R). The ideal gas law was developed from Boyle’s and Charles’s laws, which were formed from experimental observations.

The petroleum industry works with a set of standard conditions—usually 14.7 psia and 60°F. When a volume of gas is reported at these conditions, it is given the units of SCF (standard cubic feet). As mentioned in Chapter 1, sometimes the letter M will appear in the units (e.g., MCF or M SCF). This refers to 1000 standard cubic feet. The volume that 1 lb-mol occupies at standard conditions is 379.4 SCF. A quantity of a pure gas can be expressed as the number of cubic feet at a specified temperature and pressure, the number of moles, the number of pounds, or the number of molecules. For practical measurement, the weighing of gases is difficult, so gases are metered by volume at measured temperatures and pressures, from which the pounds or moles may be calculated. Example 2.1 illustrates the calculations of the contents of a tank of gas in each of three units.

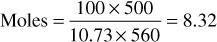

Example 2.1 Calculating the Contents of a Tank of Ethane in Moles, Pounds, and SCF

Given

A 500-ft3 tank of ethane at 100 psia and 100°F.

Solution

Assuming ideal gas behavior,

Pounds = 8.32 × 30.07 = 250.2

At 14.7 psia and 60°F,

SCF = 8.32 × 379.4 = 3157

Here is an alternate solution using Eq. (2.4):

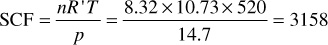

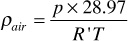

Because the density of a substance is defined as mass per unit volume, the density of gas, ρg, at a given temperature and pressure can be derived as follows:

Mw = molecular weight

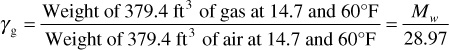

Because it is more convenient to measure the specific gravity of gases than the gas density, specific gravity is more commonly used. Specific gravity is defined as the ratio of the density of a gas at a given temperature and pressure to the density of air at the same temperature and pressure, usually near 60°F and atmospheric pressure. Whereas the density of gases varies with temperature and pressure, the specific gravity is independent of temperature and pressure when the gas obeys the ideal gas law. By the previous equation, the density of air is

Then the specific gravity, γg, of a gas is

Equation (2.6) might also have been obtained from the previous statement that 379.4 ft3 of any ideal gas at 14.7 psia and 60°F is 1 mol and therefore a weight equal to the molecular weight. Thus, by definition of specific gravity,

If the specific gravity of a gas is 0.75, its molecular weight is 21.7 lbs per mol.

Everything up to this point applies to a perfect or ideal gas. Actually there are no perfect gases; however, many gases near atmospheric temperature and pressure approach ideal behavior. All molecules of real gases have two tendencies: (1) to fly apart from each other because of their constant kinetic motion and (2) to come together because of electrical attractive forces between the molecules. Because the molecules are quite far apart, the intermolecular forces are negligible and the gas behaves close to ideal. Also, at high temperatures, the kinetic motion, being greater, makes the attractive forces comparatively negligible and, again, the gas approaches ideal behavior.

When the volume of a gas will be less than what the ideal gas volume would be, the gas is said to be supercompressible. The number, which measures the gas’s deviation from perfect behavior, is sometimes called the supercompressibility factor, usually shortened to the gas compressibility factor. More commonly it is called the gas deviation factor (z). This dimensionless quantity usually varies between 0.70 and 1.20, with a value of 1.00 representing ideal behavior.

At very high pressures, above about 5000 psia, natural gases pass from a supercompressible condition to one in which compression is more difficult than in the ideal gas. The explanation is that, in addition to the forces mentioned earlier, when the gas is highly compressed, the volume occupied by the molecules themselves becomes an appreciable portion of the total volume. Since it is really the space between the molecules that is compressed and there is less compressible space, the gas appears to be more difficult to compress. In addition, as the molecules get closer together (i.e., at high pressure), repulsive forces begin to develop between the molecules. This is indicated by a gas deviation factor greater than unity. The gas deviation factor is by definition the ratio of the volume actually occupied by a gas at a given pressure and temperature to the volume it would occupy if it behaved ideally, or

These theories qualitatively explain the behavior of nonideal or real gases. Equation (2.7) may be substituted in the ideal gas law, Eq. (2.4), to give an equation for use with nonideal gases,

where Va is the actual gas volume. The gas deviation factor must be determined for every gas and every combination of gases and at the desired temperature and pressure—for it is different for each gas or mixture of gases and for each temperature and pressure of that gas or mixture of gases. The omission of the gas deviation factor in gas reservoir calculations may introduce errors as large as 30%.7 Figure 2.1 shows the gas deviation factors of two gases, one of 0.90 specific gravity and the other of 0.665 specific gravity. These curves show that the gas deviation factors drop from unity at low pressures to a minimum value near 2500 psia. They rise again to unity near 5000 psia and to values greater than unity at still higher pressures. In the range of 0 to 5000 psia, the deviation factors at the same temperature will be lower for the heavier gas, and for the same gas, they will be lower at the lower temperature.

When possible reservoir fluid samples should be acquired at the formation level, such samples are termed bottom-hole fluid samples, and great care must be taken to avoid sampling the reservoir fluid below bubble-point or dew-point pressure. Without a bottom-hole fluid sample, produced wet gas or gas condensate may be recombined at the surface. This may be accomplished by recombining samples of separator gas, stock-tank gas, and stock-tank liquid in the proportions in which they are produced. The deviation factor is measured at reservoir temperature for pressures ranging from reservoir to atmospheric. For wet gas or gas condensate, the deviation factor may be measured for differentially liberated gas below the dew-point pressure. For reservoir oil, the deviation factor of solution gas is measured on gas samples evolved from solution in the oil during a differential liberation process.

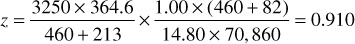

The gas deviation factor is commonly determined by measuring the volume of a sample at desired pressures and temperatures and then measuring the volume of the same mass of gas at atmospheric pressure and at a temperature sufficiently high so that all the material remains in the vapor phase. For example, a sample of the Bell Field gas has a measured volume of 364.6 cm3 at 213°F and 3250 psia. At 14.80 psia and 82°F, it has a volume of 70,860 cm3. Then, by Eq. (2.8), assuming a gas deviation factor of unity at the lower pressure, the deviation factor at 3250 psia and 213°F is

If the gas deviation factor is not measured, it may be estimated from its specific gravity. Example 2.2 shows the method for estimating the gas deviation factor from its specific gravity. The method uses a correlation to estimate pseudocritical temperature and pressure values for a gas with a given specific gravity. The correlation was developed by Sutton on the basis of over 5000 different gas samples.8 Sutton developed a correlation for two distinct types of gases—one being an associated gas and the other being a condensate gas. An associated gas is defined as a gas that has been liberated from oil and typically contains large concentrations of ethane through pentane. A condensate gas typically contains a vaporized hydrocarbon liquid, resulting in a high concentration of the heptanes-plus fractions in the gas phase.

For the associated gases, Sutton conducted a regression analysis on the raw data and obtained the following equations over the range of specific gas gravities with which he worked—0.554 < γg < 1.862:

Sutton found the following equations for the condensate gases covering the range of gas gravities of 0.554 < γg < 2.819:

Both sets of these correlations were derived for gases containing less than 10% of H2S, CO2, and N2. If concentrations of these gases are larger than 10%, the reader is referred to the original work of Sutton for corrections.

Having obtained the pseudocritical values, the pseudoreduced pressure and temperature are calculated. The gas deviation factor is then found by using the correlation chart of Fig. 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Compressibility factors for natural gases (after Standing and Katz, trans. AlME).9

Example 2.2 Calculating the Gas Deviation Factor of a Gas Condensate from Its Specific Gravity

Given

Gas specific gravity = 0.665

Reservoir temperature = 213°F

Reservoir pressure = 3250 psia

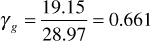

Solution

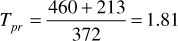

Using Eqs. (2.11) and (2.12), the pseudocritical values are

ppc = 744 – 125.4(0.665) + 5.9(0.665)2 = 663 psia

Tpc = 164.3 + 357.7(0.665) – 67.7(0.665)2 = 372°R

For 3250 psia and 213°F, the pseudoreduced pressure and temperature are

Using the calculated values in Fig. 2.2, z = 0.918.

In many reservoir-engineering calculations, it is necessary to use the assistance of a computer, and the chart of Standing and Katz then becomes difficult to use. Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem fit an equation of state to the data of Standing and Katz in order to estimate the gas deviation factor in computer routines.10 Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem used 1500 data points and found an average absolute error of 0.486% over ranges of pseudoreduced pressure and temperature of

0.2 < ppr < 30

1.0 < Tpr < 3.0

and for

ppr < 1.0 with 0.7 < Tpr < 1.0

The Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem equation of state gives poor results for Tpr = 1.0 and ppr > 1.0. The form of the Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem equation of state is as follows:

where

Because the z-factor is on both sides of the equation, an iterative method is necessary to solve the Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem equation of state. Any one of a number of techniques can be used to assist in the iterative method.11 The Excel solver function is a common computer tool to solve these types of iterative problems, and instructions on its use are available in the Help section of the Excel program.

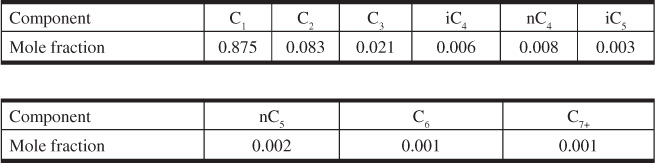

A more accurate estimation of the deviation factor can be made when the analysis of the gas is available. This calculation assumes that each component contributes to the pseudocritical pressure and temperature in proportion to its volume percentage in the analysis and to the critical pressure and temperature, respectively, of that component. Table 2.1 gives the critical pressures and temperatures of the hydrocarbon compounds and others commonly found in natural gases.12 It also gives some additional physical properties of these compounds. Example 2.3 shows the method of calculating the gas deviation factor from the composition of the gas.

Table 2.1 Physical Properties of the Paraffin Hydrocarbons and Other Compounds (after Eilerts12)

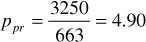

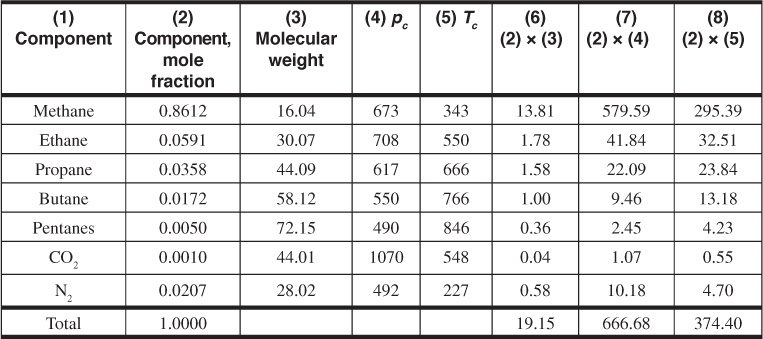

Example 2.3 Calculating the Gas Deviation Factor of the Bell Field Gas from Its Composition

Given

The composition column 2 and the physical data columns 3 to 5 are taken from Table 2.1.

Solution

The specific gravity may be obtained from the sum of column 6, which is the average molecular weight of the gas,

The sums of columns 7 and 8 are the pseudocritical pressure and temperature, respectively. Then, at 3250 psia and 213°F, the pseudoreduced pressure and temperature are

The gas deviation factor using Fig. 2.2 is z = 0.91.

Wichert and Aziz have developed a correlation to account for inaccuracies in the Standing and Katz chart when the gas contains significant fractions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).13 The Wichert and Aziz correlation modifies the values of the pseudocritical constants of the natural gas. Once the modified constants are obtained, they are used to calculate pseudoreduced properties, as described in Example 2.2, and the z-factor is determined from Fig. 2.2 or Eq. (2.13). The Wichert and Aziz correlation equation is as follows:

where

A = sum of the mole fractions of CO2 and H2S in the gas mixture

B = mole fraction of H2S in the gas mixture

The modified pseudocritical properties are given by

Wichert and Aziz found their correlation to have an average absolute error of 0.97% over the following ranges of data: 154 < p (psia) < 7026 and 40 < T (°F) < 300. The correlation is good for concentrations of CO2 < 54.4% (mol %) and H2S < 73.8% (mol %).

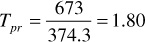

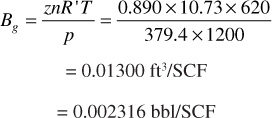

The gas formation volume factor (Bg) relates the volume of gas in the reservoir to the volume on the surface (i.e., at standard conditions psc and Tsc). It is generally expressed in either cubic feet or barrels of reservoir volume per standard cubic foot of gas. Assuming a gas deviation factor of unity for the standard conditions, the reservoir volume of 1 std ft3 at reservoir pressure p and temperature T by Eq. (2.8) is

where psc is 14.7 psia and Tsc is 60°F:

The constants in Eq. (2.16) are for 14.7 psia and 60°F only, and different constants must be calculated for other standards. Thus for the Bell Field gas at a reservoir pressure of 3250 psia, a temperature of 213°F, and a gas deviation factor of 0.910, the gas volume factor is

These gas volume factors mean that 1 std ft3 (at 14.7 psia and 60°F) will occupy 0.00533 ft3 of space in the reservoir at 3250 psia and 213°F. Because oil is usually expressed in barrels and gas in cubic feet, when calculations are made on combination reservoirs containing both gas and oil, either the oil volume must be expressed in cubic feet or the gas volume in barrels. The foregoing gas volume factor expressed in barrels is 0.000949 bbl/SCF. Then 1000 ft3 of reservoir pore volume in the Bell Field gas reservoir at 3250 psia contains

G = 1000 ft3 ÷ 0.00533 ft3/SCF = 188 M SCF

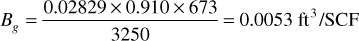

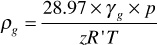

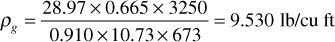

Equation (2.8) may also be used to calculate the density of a reservoir gas. An expression for the moles of gas in 1 ft3 of reservoir gas pore space is p/zRT. By Eq. (2.6), the molecular weight of a gas is 28.97 × γg lb per mol. Therefore, the pounds contained in 1 ft3—that is, the reservoir gas density (ρg)—is

For example, the density of the Bell Field reservoir gas with a gas gravity of 0.665 is

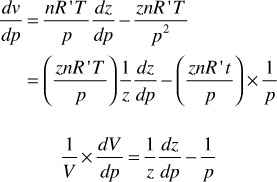

The change in volume with pressure for gases under isothermal conditions, which is closely realized in reservoir gas flow, is expressed by the real gas law:

Sometimes it is useful to introduce the concept of gas compressibility. This must not be confused with the gas deviation factor, which is also referred to as the gas compressibility factor. Equation (2.17) may be differentiated with respect to pressure at constant temperature to give

Finally, because

for an ideal gas, z = 1.00 and dz/dp = 0, and the compressibility is simply the reciprocal of the pressure. An ideal gas at 1000 psia, then, has a compressibility of 1/1000 or 1000 × 10–6 psi–1. Example 2.4 shows the calculation of the compressibility of a gas from the gas deviation factor curve of Fig. 2.4 using Eq. (2.18).

Example 2.4 Finding the Compressibility of a Gas from the Gas Deviation Factor Curve

Given

The gas deviation factor curve for a gas at 150°F is shown in Fig. 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Gas compressibility from the gas deviation factor versus pressure plot (see Example 2.4).

Solution

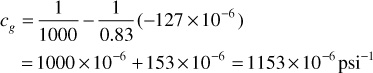

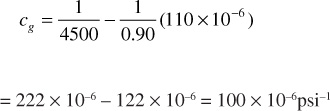

At 1000 psia, the slope dz/dp is shown graphically in Fig. 2.3 as –127 × 10–6. Note that this is a negative slope. Then, because z = 0.83

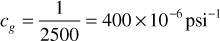

At 2500 psia, the slope dz/dp is zero, so the compressibility is simply

At 4500 psia, the slope dz/dp is positive and, as shown in Fig. 2.3, is equal to 110 × 10–6psi–1. Since z = 0.90 at 4500 psia,

Trube has replaced the pressure in Eq. (2.18) by the product of the pseudocritical and the pseudoreduced pressures, or p = ppc(ppr) and dp = ppcdppr.14 This obtains

Multiplying through by the pseudocritical pressure, the product cg(ppc) is obtained, which Trube defined as the pseudoreduced compressibility (cr):

Mattar, Brar, and Aziz developed an analytical expression for calculating the pseudoreduced compressibility.15 The expression is

Taking the derivative of Eq. (2.13), the equation of state developed by Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem,10 the following are obtained:

and

Using Eqs. (2.21) to (2.23) and the definition of the pseudoreduced compressibility, the gas compressibility can be calculated for any gas as long as the gas pressure and temperature are within the ranges specified for the Dranchuk and Abou-Kassem correlation. Using these equations, Blasingame, Johnston, and Poe generated Figs. 2.4 and 2.5.16 In these figures, the product of crTpr is plotted as a function of the pseudoreduced properties, ppr and Tpr. Example 2.5 illustrates how to use these figures. Because they are logarithmic in nature, better accuracy can be obtained by using the equations directly.

Figure 2.4 Variation in crTpr for natural gases for 1.05 ≤ Tpr ≤ 1.4 (after Blasingame).16

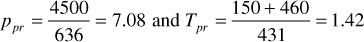

Example 2.5 Finding Compressibility Using the Mattar, Brar, and Aziz Method

Given

Find the compressibility for a 0.90 specific gravity gas condensate when the temperature is 150°F and pressure is 4500 psia.

From Eq. (2.11) and (2.12), ppc = 636 psia and Tpc = 431°R. Thus,

From Fig. 2.5, crTpr = 0.088. Thus,

Figure 2.5 Variation in crTpr for natural gases for 1.4 ≤ Tpr ≤ 3.0 (after Blasingame).16

The viscosity of natural gas depends on the temperature, pressure, and composition of the gas. It has units of centipoise (cp). It is not commonly measured in the laboratory because it can be estimated with good precision. Carr, Kobayashi, and Burrows have developed correlation charts, Figs. 2.6 and 2.7, for estimating the viscosity of natural gas from the pseudoreduced temperature and pressure.17 The pseudoreduced temperature and pressure may be estimated from the gas specific gravity or calculated from the composition of the gas. The viscosity at 1 atm and reservoir temperature (Fig. 2.6) is multiplied by the viscosity ratio (Fig. 2.7) to obtain the viscosity at reservoir temperature and pressure. The inserts of Fig. 2.6 are corrections to be added to the atmospheric viscosity when the gas contains nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and/or hydrogen sulfide. Example 2.6 illustrates the use of the estimation charts.

Figure 2.6 The viscosity of hydrocarbon gases at 1 atm and reservoir temperature, with corrections for nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide (after Carr, Kobayashi, and Burrows, trans. AlME).17

Figure 2.7 Viscosity ratio as a function of pseudoreduced temperature and pressure (after Carr, Kobayashi, and Burrows, trans. AlME).17

Example 2.6 Using Correlation Charts to Estimate Reservoir Gas Viscosity

Given

Reservoir pressure = 2680 psia

Reservoir temperature = 212°F

Well fluid specific gravity = 0.90 (Air = 1.00)

Pseudocritical temperature = 420°R

Pseudocritical pressure = 670 psia

Carbon dioxide content = 5 mol %

μ1 = 0.0117 cp at 1 atm (Fig. 2.6)

Correction for CO2 = 0.0003 cp (Fig. 2.6, insert)

μ1 = 0.0117 + 0.0003 = 0.0120 cp (corrected for CO2)

μ/μ1 = 1.60 (Fig. 2.7)

μ = 1.60 × 0.0120 = 0.0192 cp at 212°F and 2608 psia

Lee, Gonzalez, and Eakin developed a semiempirical method that gives an accurate estimate of gas viscosity for most natural gases having specific gravities less than 0.77 if the z-factor has been calculated to include the effect of contaminants.18 For the data from which the correlation was developed, the standard deviation in the calculated gas viscosity was 2.69%. The ranges of variables used in the correlation were 100 < p (psia) < 8000, 100 < T (°F) < 340, 0.55 < N2 (mol %) < 4.8, and 0.90 < CO2 (mol %) < 3.20. In addition to the gas temperature and pressure, the method requires the z-factor and molecular weight of the gas. The following equations are used in the calculation for the gas viscosity in cp:

where

where

ρg = gas density from Eq. (2.5), g/cc

p = pressure, psia

T = temperature, °R

Mw = gas molecular weight

The next few sections contain information on crude oil properties, including several correlations that can be used to estimate values for the properties. McCain, Spivey, and Lenn present an excellent review of these correlations in their book, Reservoir Fluid Property Correlations.19 However, these crude oil property correlations are, in general, not as reliable as the correlations that have been presented earlier for gases. There are two main reasons for the oil correlations being less reliable. The first is that oils usually consist of many more components than gases. Whereas gases are mostly made up of alkanes, oils can be made up of several different classes of compounds (e.g., aromatics and paraffins). The second reason is that mixtures of liquid components exhibit more nonidealities than mixtures of gas components. These nonidealities can lead to errors in extrapolating correlations that have been developed for a certain database of samples to particular applications outside the database. Before using any of the correlations, the engineer should make sure that the application of interest fits within the range of parameters for which a correlation was developed. As long as this is done, the correlations used for estimating liquid properties will be adequate and can be expected to yield accurate results. Correlations should only be used in the early stages of production from a reservoir when laboratory data may not be available. The most accurate values for liquid properties would come from laboratory measurements on a bottom-hole fluid sample. Ezekwe has presented a summary of various methods used to collect reservoir fluid samples and subsequent laboratory procedures to measure fluid properties.3

The amount of gas dissolved in an oil at a given pressure and temperature is referred to as the solution gas-oil ratio (Rso), in units of SCF/STB. The solubility of natural gas in crude oil depends on the pressure, temperature, and composition of the gas and the crude oil. For a particular gas and crude oil at constant temperature, the quantity of solution gas increases with pressure, and at constant pressure, the quantity decreases with increasing temperature. For any temperature and pressure, the quantity of solution gas increases as the compositions of the gas and crude oil approach each other—that is, it will be greater for higher specific gravity gases and higher API gravity crudes. Unlike the solubility of, say, sodium chloride in water, gas is infinitely soluble in crude oil, the quantity being limited only by the pressure or by the quantity of gas available.

Crude oil is said to be saturated with gas at any pressure and temperature if, on a slight reduction in pressure, some gas is released from the solution. Conversely, if no gas is released from the solution, the crude oil is said to be undersaturated at that pressure. The undersaturated state implies that there is a deficiency of gas present and that, had there been an abundance of gas present, the oil would be saturated at that pressure. The undersaturated state further implies that there is no free gas in contact with the crude oil (i.e., there is no gas cap).

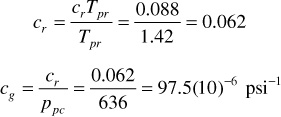

Gas solubility under isothermal conditions is generally expressed in terms of the increase in solution gas per unit of oil per unit increase in pressure (e.g., SCF/STB/psi or dRso/dp). Although for many reservoirs, this solubility figure is approximately constant over a considerable range of pressures, for precise reservoir calculations, the solubility is expressed in terms of the total gas in solution at any pressure (e.g., SCF/STB, or Rso). It will be shown that the reservoir volume of crude oil increases appreciably because of the solution gas, and for this reason, the quantity of solution gas is usually referenced to a unit of stock-tank oil and the solution gas-oil ratio (Rso) is expressed in standard cubic feet per stock-tank barrel. Figure 2.8 shows the variation of solution gas with pressure for the Big Sandy reservoir fluid at reservoir temperature 160°F. At the initial reservoir pressure of 3500 psia, there is 567 SCF/STB of solution gas. The graph indicates that no gas is evolved from the solution when the pressure drops from the initial pressure to 2500 psia. Thus the oil is undersaturated in this region, and there can be no free gas phase (gas cap) in the reservoir. The pressure 2500 psia is called the bubble-point pressure, for at this pressure bubbles of free gas first appear. At 1200 psia, the solution gas is 337 SCF/STB, and the average solubility between 2500 and 1200 psia is

Figure 2.8 Solution gas-oil ratio of the Big Sandy Field reservoir oil, by flash liberation at reservoir temperature of 160°F.

The data of Fig. 2.8 were obtained from a laboratory PVT study of a bottom-hole sample of the Big Sandy reservoir fluid using a flash liberation process that will be defined in Chapter 7.

In Chapter 7, it will be shown that the solution gas-oil ratio and other fluid properties depend on the manner by which the gas is liberated from the oil. The nature of the phenomenon is discussed together with the complications it introduces into certain reservoir calculations. For the sake of simplicity, this phenomenon is ignored and a stock-tank barrel of oil is identified, with a barrel of residual oil following a flash liberation process, and the solution gas-oil ratios by flash liberation are used.

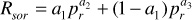

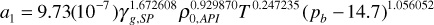

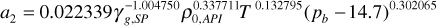

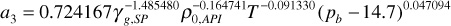

Estimating a value for the solution gas-oil ratio, Rsob, at the bubble point requires information about the conditions at which the surface separator is operating. If the separator pressure and temperature are not available, then Valko and McCain propose the following equation to estimate Rsob20:

where

Rso,SP = solution gas-oil ratio at the exit of the separator

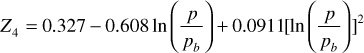

When laboratory analyses of the reservoir fluids are not available, it is often possible to estimate the solution gas-oil ratio with reasonable accuracy. Velarde, Blasingame, and McCain give a correlation method from which the solution gas-oil ratio may be estimated from the reservoir pressure, the reservoir temperature, the bubble-point pressure, the solution gas-oil ratio at the bubble-point pressure, the API gravity of the tank oil, and the specific gravity of the separator gas.21 The correlation involves the following equations:

where

Rsob = solution gas-oil ratio at the bubble-point pressure, STB/SCF

p = pressure, psia

pb = pressure at the bubble-point, psia

γg,SP = specific gravity of the separator gas

ρo,API = gravity of the stock-tank oil, °API

The gravity of the stock-tank oil is frequently reported as a specific gravity relative to water at 60°F. The equation used to convert from specific gravity to units of °API is

If the density is reported in °API and is needed in lb/ft3, then rearrange Eq. (2.27) and solve for the specific gravity. The specific gravity is then multiplied by the density of water at 60°F, which is 62.4 lb/ft3.

The formation volume factor (Bo), which is also abbreviated FVF, at any pressure may be defined as the volume in barrels that one stock-tank barrel occupies in the formation (reservoir) at reservoir temperature, with the solution gas that can be held in the oil at that pressure. Because both the temperature and the solution gas increase the volume of the stock-tank oil, the factor will always be greater than 1. When all the gas present is in solution in the oil (i.e., at the bubble-point pressure), a further increase in pressure decreases the volume at a rate that depends on the compressibility of the liquid.

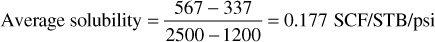

It was observed earlier that the solution gas causes a considerable increase in the volume of the crude oil. Figure 2.9 shows the variation in the formation volume factor of the reservoir liquid of the Big Sandy reservoir as a function of pressure at reservoir temperature of 160°F. Because no gas is released from solution when the pressure drops from the initial pressure of 3500 psia to the bubble-point pressure at 2500 psia, the reservoir fluid remains in a single (liquid) state; however, because liquids are slightly compressible, the FVF increases from 1.310 bbl/STB at 3500 psia to 1.333 bbl/STB at 2500 psia. Below 2500 psia, this liquid expansion continues but is masked by a much larger effect: the decrease in the liquid volume due to the release of gas from solution. At 1200 psia, the FVF decreases to 1.210 bbl/STB, and at atmospheric pressure and 160°F, the FVF decreases to 1.040 bbl/STB. The coefficient of temperature expansion for the 30°API stock-tank oil of the Big Sandy reservoir is close to 0.0004 per degrees Fahrenheit; therefore, one stock-tank barrel at 60°F will expand to about 1.04 bbl at 160°F, as calculated from

Figure 2.9 Formation volume factor of the Big Sandy Field reservoir oil, by flash liberation at reservoir temperature of 160°F.

where β is the temperature coefficient of expansion of the oil.

One obvious implication of the formation volume factor is that for every 1.310 bbl of reservoir liquid in the Big Sandy reservoir, only 1.000 bbl, or 76.3%, can reach the stock tank. This figure (76.3% or 0.763) is the reciprocal of the formation volume factor and is called the shrinkage factor. Just as the formation volume factor is multiplied by the stock-tank volume to find the reservoir volume, the shrinkage factor is multiplied by the reservoir volume to find the stock-tank volume. Although both terms are in use, petroleum engineers have almost universally adopted the formation volume factor. As mentioned previously, the formation volume factors depend on the type of gas liberation process—a phenomenon that we ignore until Chapter 7.

In some equations, it is convenient to use the term two-phase formation volume factor (Bt), which is defined as the volume in barrels one stock-tank barrel and its initial complement of dissolved gas occupies at any pressure and reservoir temperature. In other words, it includes the liquid volume, Bo, plus the volume of the difference between the initial solution gas-oil ratio, Rsoi, and the solution gas-oil ratio at the specified pressure, Rso. If Bg is the gas volume factor in barrels per standard cubic foot of the solution gas, then the two-phase formation volume factor can be expressed as

Above the bubble point, pressure Rsoi = Rso and the single-phase and two-phase factors are equal. Below the bubble point, however, while the single-phase factor decreases as pressure decreases, the two-phase factor increases, owing to the release of gas from solution and the continued expansion of the gas released from solution.

The single-phase and two-phase volume factors for the Big Sandy reservoir fluid may be visualized by referring to Fig. 2.10, which is based on data from Figs. 2.8 and 2.9. Figure 2.10 (A) shows a cylinder fitted with a piston that initially contains 1.310 bbl of the initial reservoir fluid (liquid) at the initial pressure of 3500 psia and 160°F. As the piston is withdrawn, the volume increases and the pressure consequently must decrease. At 2500 psia, which is the bubble-point pressure, the liquid volume has expanded to 1.333 bbl. Below 2500 psia, a gas phase appears and continues to grow as the pressure declines, owing to the release of gas from solution and the expansion of gas already released; conversely, the liquid phase shrinks because of loss of solution gas to 1.210 bbl at 1200 psia. At 1200 psia and 160°F, the liberated gas has a deviation factor of 0.890, and therefore the gas volume factor with reference to standard conditions of 14.7 psia and 60°F is

Figure 2.10 Visual conception of the change in single-phase and in two-phase formation volume factors for the Big Sandy reservoir fluid.

Figure 2.8 shows an initial solution gas of 567 SCF/STB and, at 1200 psia, 337 SCF/STB, the difference of 230 SCF being the gas liberated down to 1200 psia. The volume of these 230 SCF is

Vg = 230 × 0.01300 = 2.990 ft3

This free gas volume, 2.990 ft3 or 0.533 bbl, plus the liquid volume, 1.210 bbl, is the total FVF or 1.743 bbl/STB—the two-phase volume factor at 1200 psia. It may also be obtained by Eq. (2.28) as

Bt = 1.210 + 0.002316 (567 – 337)

= 1.210 + 0.533 = 1.743 bbl/STB

Figure 2.10 (C) shows these separate and total volumes at 1200 psia. At 14.7 psia and 160°F (D), the gas volume has increased to 676 ft3 and the oil volume has decreased to 1.040 bbl. The total liberated gas volume, 676 ft3 at 160°F and 14.7 psia, is converted to standard cubic feet at 60°F and 14.7 psia using the ideal gas law, producing 567 SCF/STB as shown in (E). Correspondingly, 1.040 bbl at 160°F is converted to stock-tank conditions of 60°F as shown in Eq. (2.28) to give 1.000 STB, also shown in (E).

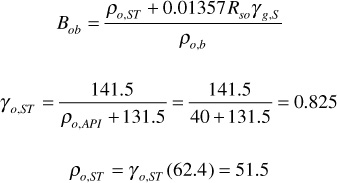

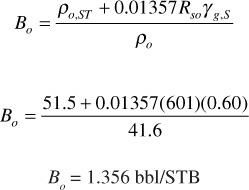

The single-phase formation volume factor for pressures less than the bubble-point pressure may be estimated from the solution gas-oil ratio, oil density, density of the stock-tank oil, and the weighted average specific gravity of the surface gas, using a correlation prepared by McCain, Spivey, and Lenn:19

where

ρo,ST = density of stock-tank oil, lb/ft3

γg,S = weighted average specific gravity of the surface gas

ρo = oil density

The weighted average specific gravity of the surface gas should be calculated from the specific gravities of the stock-tank and the separator gases from the following equation:

where

γg,SP = specific gravity of the separator gas

RSP = separator gas-oil ratio

γg,ST = specific gravity of the stock-tank gas

RST = stock-tank gas-oil ratio

For pressures greater than the bubble-point pressure, Eq. (2.32) is used to calculate the formation volume factor:

where

Bob = oil formation volume factor at the bubble-point pressure

co = oil compressibility, psi–1

Column (2) of Table 2.2 shows the variation in the volume of a reservoir fluid relative to the volume at the bubble point of 2695 psig, as measured in the laboratory. These relative volume factors may be converted to formation volume factors if the formation volume factor at the bubble point is known. For example, if Bob = 1.391 bbl/STB, then the formation volume factor at 4100 psig is

Bo at 4100 psig = 1.391(0.9829) = 1.367 bbl/STB

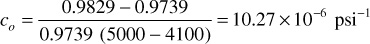

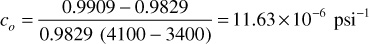

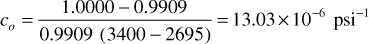

Sometimes it is desirable to work with values of the liquid compressibility rather than the formation or relative volume factors. The isothermal compressibility, or the bulk modulus of elasticity of a liquid, is defined by Eq. (2.1):

The compressibility, c, is written in general terms since the equation applies for both liquids and solids. For a liquid oil, c will be given a subscript of co to differentiate it from a solid. Because dV/dp is a negative slope, the negative sign converts the oil compressibility, co, into a positive number. Because the values of the volume V and the slope of dV/dp are different at each pressure, the oil compressibility is different at each pressure, being higher at the lower pressure. Average oil compressibilities may be used by writing Eq. (2.1) as

The reference volume V in Eq. (2.33) may be V1, V2, or an average of V1 and V2. It is commonly reported for reference to the smaller volume—that is, the volume at the higher pressure. The following expressions determine the average compressibility of the fluid of Table 2.2 between 5000 psig and 4100 psig

between 4100 psig and 3400 psig

and between 3400 psig and 2695 psig

A compressibility of 13.03 × 10–6 psi–1 means that the volume of 1 million barrels of reservoir fluid will increase by 13.03 bbls for a reduction of 1 psi in pressure. The compressibility of undersaturated oils ranges from 5 to 100 × 10–6 psi–1, being higher for the higher API gravities, for the greater quantity of solution gas, and for higher temperatures.

Spivey, Valko, and McCain presented a correlation for estimating the compressibility for pressures above the bubble-point pressure.22 This correlation yields the compressibility in units of microsips (1 microsip = 10–6/psi). The correlation involves the following equations:

The correlation gives good results for the following ranges of data:

11.6 ≤ ρo,API ≤ 57.7 °API

0.561 ≤ γg,SP ≤ 1.798 (air = 1)

120.7 ≤ pb ≤ 6658.7 psia

414.7 ≤ p ≤ 8114.7 psia

12 ≤ Rsob ≤ 1808 SCF/STB

70.7 ≤ T ≤ 320 °F

3.6 ≤ co ≤ 50.3 microsips

Villena-Lanzi developed a correlation to estimate co for black oils.23 A black oil has nearly all its dissolved gas removed. The correlation is good for pressures below the bubble-point pressure and is given by

where

T = °F

The correlation was developed from a database containing the following ranges:

31.0(10)–6 < co (psia–1) < 6600(10)–6

500 < p (psig) < 5300

763 < pb (psig) < 5300

78 < T (°F) < 330

1.5 < Rsob, gas-oil ratio (SCF/STB) < 1947

6.0 < ρo, API (°API) < 52.0

0.58 < γg < 1.20

The viscosity of oil under reservoir conditions is commonly measured in the laboratory. Figure 2.11 shows the viscosities of four oils at reservoir temperature, above and below bubble-point pressure. Below the bubble point, the viscosity decreases with increasing pressure owing to the thinning effect of gas entering solution, but above the bubble point, the viscosity increases with increasing pressure.

When it is necessary to estimate the viscosity of reservoir oils, correlations have been developed for both above and below the bubble-point pressure. Egbogah presented a correlation that is accurate to an average error of 6.6% for 394 different oils.24 The correlation is for what is referred to as “dead” oil, which simply means it does not contain solution gas. A second correlation is used in conjunction with the Egbogah correlation to include the effect of solution gas. Egbogah’s correlation for dead oil at pressures less than or equal to the bubble-point pressure is

where

μod = dead oil viscosity, cp

T = temperature, °F

The correlation was developed from a database containing the following ranges:

59 < T (°F) < 176

– 58 < pour point, Tpour (°F) < 59

5.0 < ρo, API (°API) < 58.0

Beggs and Robinson25,26 developed the live oil viscosity correlation that is used in conjunction with the dead oil correlation given in Eq. (2.36) to calculate the viscosity of oils at and below the bubble point:

where

A = 10.715 (Rso + 100)–0.515

B = 5.44 (Rso + 150)–0.338

The average absolute error found by Beggs and Robinson while working with 2073 oil samples was 1.83%. The oil samples contained the following ranges:

0 < p (psig) < 5250

70 < T (°F) < 295

20 < Rso, gas-oil ratio (SCF/STB) < 2070

16 < ρo, API (°API) < 58

For pressures above the bubble point, the oil viscosity can be estimated by the following correlation developed by Petrosky and Farshad:27

where

A = –1.0146 + 1.3322[log(μob)] –0.4876[log(μob)]2 – 1.15036[log(μob)]3

and

μob = oil viscosity at the bubble-point pressure, cp

The following example problem illustrates the use of the correlations that have been presented for the various oil properties.

Example 2.7 Using Correlations to Estimate Values for Liquid Properties at Pressures of 2000 psia and 4000 psia

Given

T = 180°F

pb = 2500 psia

Rso,SP = 664 SCF/STB

γg,SP = 0.56

γg,S = 0.60

ρo,API = 40 °API

ρo,b = 39.5 lb/ft3

ρo,2000 = 41.6 lb/ft3

γo = 0.85

Solution

Solution Gas-Oil Ratio, Rso

p = 4000 psia (p > pb)

For pressures greater than the bubble-point pressure, Rso = Rsob; therefore, from Eq. (2.25),

Rso = Rsob = 1.1618

Rso,SP = 1.1618(664)

Rsob = 771 SCF/STB

Rso = (Rsob) (Rsor) = 771Rsor

pr = (p – 14.7)/(pb – 14.7) = (2000 – 14.7)/(2500 – 14.7) = 0.799

a1 = 9.73(10–7)0.561.672608400.9298701800.247235(2500 – 14.7)1.056052 = 0.158

a2 = 0.022339(0.56–1.004750)400.3377111800.132795(2500 – 14.7)0.302065 = 2.939

a3 = 0.725167(0.56–1.485480)40–0.164741180–0.091330(2500 – 14.7)0.047094 = 0.840

Rsor = 0.288(0.799)0.194 + (1 – 0.288)(0.799)0.495 = 0.779

Rso = (771)(0.779) = 601

Isothermal Compressibility, co

p = 4000 psia (p > pb)

From Eq. (2.34),

ln co = 2.434 + 0.475Z + 0.048Z2 – ln(106)

Z1 = 3.011 – 2.6254ln(ρo,API) + 0.497[ln(ρo,API)]2

Z1 = 3.011 – 2.6254ln(40) + 0.497[ln(40)]2 = 0.089

Z2 = –0.0835 – 0.259ln(γg,SP) + 0.382[ln(γg,SP)]2

Z2 = –0.0835 – 0.259ln(0.56) + 0.382[ln(0.56)]2 = 0.195

Z3 = 3.51 – 0.0289ln(pb) – 0.0584[ln(pb)]2

Z3 = 3.51 – 0.0289ln(2500) – 0.0584[ln(2500)]2 = –0.291

Z4 = 0.327 – 0.608ln(4000/2500) + 0.0911[ln(4000/2500)]2 = 0.061

Z5 = –1.918 – 0.642ln(Rsob) + 0.154[ln(Rsob)]2

Z5 = –1.918 – 0.642ln(771) + 0.154[ln(771)]2 = 0.620

Z6 = 2.52 – 2.73ln(T) + 0.429[ln(T)]2

Z6 = 2.52 – 2.73ln(180) + 0.429[ln(180)]2 = –0.088

ln(co) = ln(co) = 2.434 + 0.475Z + 0.048Z2 – ln(106) = 2.434

+ 0.475(0.586) + 0.048(0.586)2 – 13.816 = –11.087

co = 15.3(10)–6 psi–1

p = 2000 psia (p < pb)

From Eq. (2.35),

ln(co) = –0.664 – 1.430 ln(p) – 0.395 ln(pb) + 0.390 ln(T)

+ 0.455 ln(Rsob) + 0.262 ln(ρo,API)

ln(co) = – 0.664 – 1.430 ln(2000) – 0.395 ln(2500) + 0.390 ln(180)

+ 0.455 ln(771) + 0.262 ln(40)

co = 183 (10)–6 psi–1

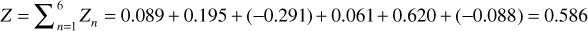

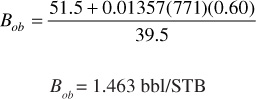

Formation Volume Factor, Bo

p = 4000 psia (p > pb)

From Eq. (2.32),

Bo = Bob exp [co(pb – p)]

Bob is calculated from Eq. (2.30) at the bubble-point pressure:

Bo = 1.463 exp [15.3(10)–6 (2500 – 4000)] = 1.430 bbl/STB

p = 2000 psia (p < pb)

From Eq. (2.30),

Viscosity, μo

From Eq. (2.36),

log10[log10(μobd + 1)] = 1.8653 – 0.025086ρo,API – 0.5644log(T)

log10[log10(μobd + 1)] = 1.8653 – 0.025086(40) – 0.5644log(180)

From Eq. (2.37),

A = 10.715 (Rsob +100)–0.515 = 10.715 (771 + 100)–0.515 = 0.328

B = 5.44 (Rsob +150)–0.338 = 5.44 (771 + 150)–0.338 = 0.542

μob = 0.328(1.444)0.542 = 0.400 cp

p = 2000 psia (p < pb)

From Eq. (2.36), μod will be the same as μobd:

μobd = 1.444 cp

A = 10.715 (Rso + 100)–0.515 = 10.715(601 + 100)–0.515 = 0.367

B = 5.44 (Rso + 150)–0.338 = 5.44(601 + 150)–0.338 = 0.580

μo = 0.367(1.444)0.580 = 0.454 cp

p = 4000 psia (p > pb)

From Eq. (2.38),

μo = μob + 1.3449(10-3)(p – pb)10A

where

A = –1.0146 + 1.3322[log(μob)] – 0.4876[log(μob)]2 – 1.15036[log(μob)]3

A = –1.0146 + 1.3322[log(0.400)] – 0.4876[log(0.400)]2 – 1.15036[log(0.400)]3

A = –1.549

μo = 0.400 + 1.3449(10–3)(4000 – 2500)10–1.549 = 0.457 cp

The properties of formation waters are affected by temperature, pressure, and the quantity of solution gas and dissolved solids, but to a much smaller degree than crude oils. The compressibility of the formation, or connate, water contributes materially in some cases to the production of volumetric reservoirs above the bubble point and accounts for much of the water influx in water-drive reservoirs. When the accuracy of other data warrants it, the properties of the connate water should be entered into the material-balance calculations on reservoirs. The following sections contain a number of correlations adequate for use in engineering applications.

McCain28 developed the following correlation for the water formation volume factor, Bw (bbl/STB):

where

ΔVwt= – 1.00010 × 10–2 + 1.33391 × 10–4 T + 5.50654 × 10–7 T2

ΔVwp= – 1.95301 × 10–9 pT – 1.72834 × 10–13 p2T – 3.58922 × 10–7 p – 2.25341 × 10–10 p2

T = temperature, °F

p = pressure, psia

For the data used in the development of the correlation, the correlation was found to be accurate to within 2%. The correlation does not account for the salinity of normal reservoir brines explicitly, but McCain observed that variations in salinity caused offsetting errors in the terms ΔVwt and ΔVwp. The offsetting errors cause the correlation to be within engineering accuracy for the estimation of the Bw of reservoir brines.

McCain has also developed a correlation for the solution gas-water ratio, Rsw (SCF/STB).28 The correlation is

where

S = salinity, % by weight solids

T = temperature, °F

Rswp = solution gas to pure water ratio, SCF/STB

Rswp is given by another correlation developed by McCain as

where

A = 8.15839 – 6.12265 × 10–2 T + 1.91663 × 10–4 T2 – 2.1654 × 10–7 T3

B = 1.01021 × 10–2 – 7.44241 × 10–5 T + 3.05553 × 10–7 T2 – 2.94883 × 10–10 T3

C = –10–7 (9.02505 – 0.130237 T + 8.53425 × 10–4 T2 – 2.34122 × 10–6 T3 + 2.37049 × 10–9 T4)

T = temperature, °F

The correlation of Eq. (2.40) was developed for the following range of data and found to be within 5% of the published data:

1000 < p (psia) < 10,000

100 < T (°F) < 340

Equation (2.41) was developed for the following range of data and found to be accurate to within 3% of published data:

0 < S (%) < 30

70 < T (°F) < 250

Osif developed a correlation for the water isothermal compressibility, cw, for pressures greater than the bubble-point pressure.29 The equation is

where

CNaCl = salinity, g NaCl/liter

T = temperature, °F

The correlation was developed for the following range of data:

1000 < p (psig) < 20,000

0 < CNaCl (g NaCl/liter) < 200

200 < T (°F) < 270

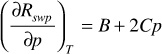

The water isothermal compressibility is strongly affected by the presence of free gas. Therefore, McCain proposed using the following expression for estimating cw for pressures below or equal to the bubble-point pressure:28

The first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (2.43) is simply the expression for cw in Eq. (2.42). The second term on the right-hand side is found by differentiating Eq. (2.41) with respect to pressure, or

where B and C are defined in Eq. (2.41).

In proposing Eq. (2.43), McCain suggested that Bg should be estimated using a gas with a gas gravity of 0.63, which represents a gas composed mostly of methane and a small amount of ethane. McCain could not verify this expression by comparing calculated values of cw with published data, so there is no guarantee of accuracy. This suggests that Eq. (2.43) should be used only for gross estimations of cw.

The viscosity of water increases with decreasing temperature and in general with increasing pressure and salinity. Pressure below about 70°F causes a reduction in viscosity, and some salts (e.g., KCl) reduce the viscosity at some concentrations and within some temperature ranges. The effect of dissolved gases is believed to cause a minor reduction in viscosity. McCain developed the following correlation for water viscosity at atmospheric pressure and reservoir temperature28:

where

A = 109.574 – 8.40564 S + 0.313314 S2 + 8.72213 × 10–3 S3

B = 1.12166 + 2.63951 × 10–2 S – 6.79461 × 10–4 S2 – 5.47119 × 10–5 S3 + 1.55586 × 10–6 S4

T = temperature, °F

S = salinity, % by weight solids

Equation (2.44) was found to be accurate to within 5% over the following range of data:

0 < S (%) < 26

The water viscosity can be adjusted to reservoir pressure by the following correlation, again developed by McCain:28

This correlation was found to be accurate to within 4% for pressures below 10,000 psia and within 7% for pressures between 10,000 psia and 15,000 psia. The temperature range for which the correlation was developed was between 86°F and 167°F.

The correlations presented in this chapter are valid for estimating properties, provided the parameters fall within the specified ranges for the particular property in question. The correlations were presented in the form of equations to facilitate their implementation into computer programs.

(a) 14.7 psia and 60°F

(b) 14.7 psia and 32°F

(c) 14.7 psia plus 10 oz and 80°F

(d) 15.025 psia and 60°F

2.2 A 500-ft3 tank contains 10 lb of methane and 20 lb of ethane at 90°F.

(a) How many moles are in the tank?

(b) What is the pressure of the tank in psia?

(c) What is the molecular weight of the mixture?

(d) What is the specific gravity of the mixture?

2.3 What are the molecular weight and specific gravity of a gas that is one-third each of methane, ethane, and propane by volume?

2.4 A 10-lb block of dry ice is placed in a 50-ft3 tank that contains air at atmospheric pressure 14.7 psia and 75°F. What will be the final pressure of the sealed tank when all the dry ice has evaporated and cooled the gas to 45°F?

2.5 A welding apparatus for a drilling rig uses acetylene (C2H2), which is purchased in steel cylinders containing 20 lb of gas and costs $10.00 exclusive of the cylinder. If a welder is using 200 ft3 per day measured at 16 oz gauge and 85°F, what is the daily cost of acetylene? What is the cost per MCF at 14.7 psia and 60°F?

2.6 (a) A 55,000 bbl (nominal) pipeline tank has a diameter of 110 ft and a height of 35 ft. It contains 25 ft of oil at the time suction is taken on the oil with pumps that handle 20,000 bbl per day. The breather and safety valves have become clogged so that a vacuum is drawn on the tank. If the roof is rated to withstand 3/4 oz per sq in. pressure, how long will it be before the roof collapses? Barometric pressure is 29.1 in. of Hg. Neglect the fact that the roof is peaked and that there may be some leaks.

(b) Calculate the total force on the roof at the time of collapse.

(c) If the tank had contained more oil, would the collapse time have been greater or less?

2.7 (a) What percentage of methane by weight does a gas of 0.65 specific gravity contain if it is composed only of methane and ethane? What percentage by volume?

(b) Explain why the percentage by volume is greater than the percentage by weight.

2.8 A 50-ft3 tank contains gas at 50 psia and 50°F. It is connected to another tank that contains gas at 25 psia and 50°F. When the valve between the two is opened, the pressure equalizes at 35 psia at 50°F. What is the volume of the second tank?

2.9 Gas was contracted at $6.00 per MCF at contract conditions of 14.4 psia and 80°F. What is the equivalent price at a legal temperature of 60°F and pressure of 15.025 psia?

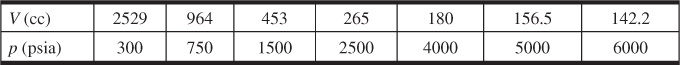

2.10 A cylinder is fitted with a leak-proof piston and calibrated so that the volume within the cylinder can be read from a scale for any position of the piston. The cylinder is immersed in a constant temperature bath maintained at 160°F, which is the reservoir temperature of the Sabine Gas Field. Forty-five thousand cc of the gas, measured at 14.7 psia and 60°F, is charged into the cylinder. The volume is decreased in the steps indicated as follows, and the corresponding pressures are read with a dead weight tester after temperature equilibrium is reached.

(a) Calculate and place in tabular form the gas deviation factors and the ideal volumes that the initial 45,000 cc occupies at 160°F and at each pressure.

(b) Calculate the gas volume factors at each pressure, in units of ft3/SCF.

(c) Plot the deviation factor and the gas volume factors calculated in part (b) versus pressure on the same graph.

2.11 (a) If the Sabine Field gas gravity is 0.65, calculate the deviation factors from zero to 6000 psia at 160°F, in 1000 lb increments, using the gas gravity correlation from Fig. 2.2.

(b) Using the critical pressures and temperatures in Table 2.1, calculate and plot the deviation factors for the Sabine gas at several pressures and 160°F. The gas analysis is as follows:

Use the molecular weight and critical temperature and pressure of n-octane for the heptanes-plus. Plot the data of Problem 2.10(a) and Problem 2.11(a) on the same graph for comparison.

(c) Below what pressure at 160°F may the ideal gas law be used for the gas of the Sabine Field if errors are to be kept within 2%?

(d) Will a reservoir contain more SCF of a real or an ideal gas at similar conditions? Explain.

2.12 A high-pressure cell has a volume of 0.330 ft3 and contains gas at 2500 psia and 130°F, at which conditions its deviation factor is 0.75. When 43.6 SCF measured at 14.7 psia and 60°F were bled from the cell through a wet test meter, the pressure dropped to 1000 psia, the temperature remaining at 130°F. What is the gas deviation factor at 1000 psia and 130°F?

2.13 A dry gas reservoir is initially at an average pressure of 6000 psia and temperature of 160°F. The gas has a specific gravity of 0.65. What will the average reservoir pressure be when one-half of the original gas (in SCF) has been produced? Assume the volume occupied by the gas in the reservoir remains constant. If the reservoir originally contained 1 MM ft3 of reservoir gas, how much gas has been produced at a final reservoir pressure of 500 psia?

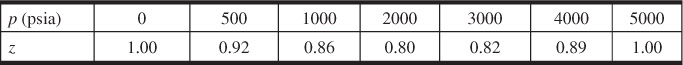

2.14 A reservoir gas has the following gas deviation factors at 150°F:

Plot z versus p and graphically determine the slopes at 1000 psia, 2200 psia, and 4000 psia. Then, using Eq. (2.19), find the gas compressibility at these pressures.

2.15 Using Eqs. (2.9) and (2.10) for an associated gas and Fig. 2.2, find the compressibility of a 70% specific gravity gas at 5000 psia and 203°F.

2.16 Using Eq. (2.21) and the generalized chart for gas deviation factors, Fig. 2.2, find the pseudoreduced compressibility of a gas at a pseudoreduced temperature of 1.30 and a pseudoreduced pressure of 4.00. Check this value on Fig. 2.4.

2.17 Estimate the viscosity of a gas condensate fluid at 7000 psia and 220°F. It has a specific gravity of 0.90 and contains 2% nitrogen, 4% carbon dioxide, and 6% hydrogen sulfide.

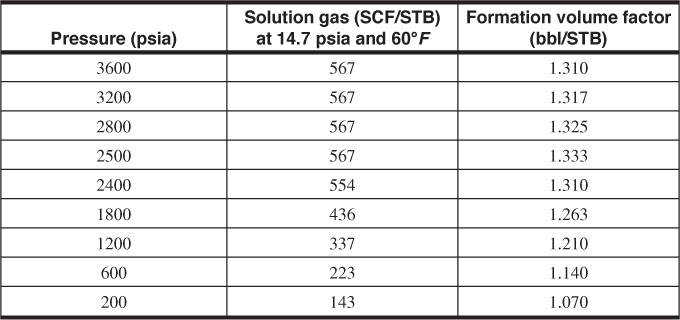

2.18 Experiments were made on a bottom-hole sample of the reservoir liquid taken from the LaSalle Oil Field to determine the solution gas and the formation volume factor as functions of pressure. The initial bottom-hole pressure of the reservoir was 3600 psia, and the bottom-hole temperature was 160°F; thus all measurements in the laboratory were made at 160°F. The following data, converted to practical units, were obtained from the measurements:

(a) Which factors affect the solubility of gas in crude oil?

(b) Plot the gas in solution versus pressure.

(c) Was the reservoir initially saturated or undersaturated? Explain.

(d) Does the reservoir have an initial gas cap?

(e) In the region of 200 to 2500 psia, determine the solubility of the gas from your graph in SCF/STB/psi.

(f) Suppose 1000 SCF of gas had accumulated with each stock-tank barrel of oil in this reservoir instead of 567 SCF. Estimate how much gas would have been in solution at 3600 psia. Would the reservoir oil then be called saturated or undersaturated?

2.19 From the bottom-hole sample given in Problem 2.18,

(a) Plot the formation volume factor versus pressure.

(b) Explain the break in the curve.

(c) Why is the slope above the bubble-point pressure negative and smaller than the positive slope below the bubble-point pressure?

(d) If the reservoir contains 250 MM reservoir barrels of oil initially, what is the initial number of STB in place?

(e) What is the initial volume of dissolved gas in the reservoir?

(f) What will be the formation volume factor of the oil when the bottom-hole pressure is essentially atmospheric if the coefficient of expansion of the stock-tank oil is 0.0006 per °F?

2.20 If the gravity of the stock-tank oil of the Big Sandy reservoir is 30 °API and the gravity of the solution gas is 0.80 °API, estimate the solution gas-oil ratio and the single-phase formation volume factor at 2500 psia and 165°F. The solution gas-oil ratio at the bubble-point pressure of 2800 psia is 625 SCF/STB.

2.21 A 1000-ft3 tank contains 85 STB of crude oil and 20,000 SCF of gas, all at 120°F. When equilibrium is established (i.e., when as much gas has dissolved in the oil as will), the pressure in the tank is 500 psia. If the solubility of the gas in the crude is 0.25 SCF/STB/psi and the deviation factor for the gas at 500 psia and 120°F is 0.90, find the liquid formation volume factor at 500 psia and 120°F.

2.22 A crude oil has a compressibility of 20 × 10–6 psi–1 and a bubble point of 3200 psia. Calculate the relative volume factor at 4400 psia (i.e., the volume relative to its volume at the bubble point), assuming constant compressibility.

2.23 (a) Estimate the viscosity of an oil at 3000 psia and 130°F. It has a stock-tank gravity of 35 °API at 60°F and contains an estimated 750 SCF/STB of solution gas at the initial bubble point of 3000 psia.

(b) Estimate the viscosity at the initial reservoir pressure of 4500 psia.

(c) Estimate the viscosity at 1000 psia if there is an estimated 300 SCF/STB of solution gas at that pressure.

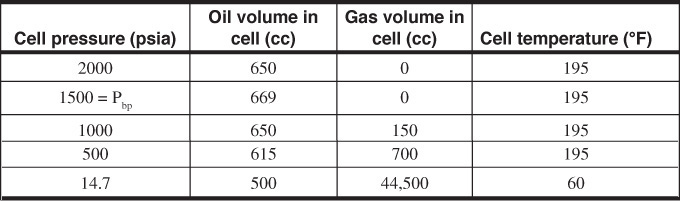

2.24 See the following laboratory data:

Evaluate Rso, Bo, and Bt at the stated pressures. The gas deviation factors at 1000 psia and 500 psia have been evaluated as 0.91 and 0.95, respectively.

2.25 (a) Find the compressibility for a connate water that contains 20,000 parts per million of total solids at a reservoir pressure of 4000 psia and temperature of 150°F.

(b) Find the formation volume factor of the formation water of part (a).

2.26 (a) What is the approximate viscosity of pure water at room temperature and atmospheric pressure?

(b) What is the approximate viscosity of pure water at 200°F?

2.27 A container has a volume of 500 cc and is full of pure water at 180°F and 6000 psia.

(a) How much water would be expelled if the pressure was reduced to 1000 psia?

(b) What would be the volume of water expelled if the salinity was 20,000 ppm and there was no gas in solution?

(c) Rework part (b) assuming that the water is initially saturated with gas and that all the gas is evolved during the pressure change.

(d) Estimate the viscosity of the water.

1. R. P. Monicard, Properties of Reservoir Rocks: Core Analysis, Gulf Publishing Co., 1980.

2. B. J. Dotson, R. L. Slobod, P. N. McCreery, and James W. Spurlock, “Porosity-Measurement Comparisons by Five Laboratories,” Trans. AlME (1951), 192, 344.

3. N. Ezekwe, Petroleum Reservoir Engineering Practice, Pearson Education, 2011.

4. W. van der Knaap, “Non-linear Elastic Behavior of Porous Media,” presented before the Society of Petroleum Engineers of AlME, Oct. 1958, Houston, TX.

5. G. H. Newman, “Pore-Volume Compressibility of Consolidated, Friable, and Unconsolidated Reservoir Rocks under Hydrostatic Loading,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (Feb. 1973), 129–34.

6. J. Geertsma, “The Effect of Fluid Pressure Decline on Volumetric Changes of Porous Rocks,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (1957), 11, No. 12, 332.

7. Henry J. Gruy and Jack A. Crichton, “A Critical Review of Methods Used in the Estimation of Natural Gas Reserves,” Trans. AlME (1949), 179, 249–63.

8. R. P. Sutton, “Fundamental PVT Calculations for Associated and Gas/Condensate Natural-Gas Systems,” SPE Res. Eval. & Eng. (2007), 10, No. 3, 270–84.

9. Marshall B. Standing and Donald L. Katz, “Density of Natural Gases,” Trans. AlME (1942), 146, 144.

10. P. M. Dranchuk and J. H. Abou-Kassem, “Calculation of Z Factors for Natural Gases Using Equations of State,” Jour. of Canadian Petroleum Technology (July–Sept. 1975), 14, No. 3, 34–36.

11. R. W. Hornbeck, Numerical Methods, Quantum Publishers, 1975.

12. C. Kenneth Eilerts et al., Phase Relations of Gas-Condensate Fluids, Vol. 10, US Bureau of Mines Monograph 10, American Gas Association, 1957, 427–34.

13. E. Wichert and K. Aziz, “Calculate Z’s for Sour Gases,” Hyd. Proc. (May 1972), 119–22.

14. A. S. Trube, “Compressibility of Natural Gases,” Trans. AlME (1957), 210, 61.

15. L. Mattar, G. S. Brar, and K. Aziz, “Compressibility of Natural Gases,” JCPT (Oct.–Dec. 1975), 77–80.

16. T. A. Blasingame, J. L. Johnston, and R. D. Poe Jr., Properties of Reservoir Fluids, Texas A&M University, 1989.

17. N. L. Carr, R. Kobayashi, and D. B. Burrows, “Viscosity of Hydrocarbon Gases under Pressure,” Trans. AlME (1954), 201, 264–72.

18. A. L. Lee, M. H. Gonzalez, and B. E. Eakin, “The Viscosity of Natural Gases,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (Aug. 1966), 997–1000; Trans. AlME (1966), 237.

19. W. D. McCain, J. P. Spivey, and C. P. Lenn, Petroleum Reservoir Fluid Property Correlations, PennWell Publishing, 2011.

20. P. P. Valko and W. D. McCain, “Reservoir Oil Bubble-Point Pressures Revisited: Solution Gas-Oil Ratios and Surface Gas Specific Gravities,” Jour. of Petroleum Science and Engineering (2003), 37, 153–69.

21. J. J. Velarde, T. A. Blasingame, and W. D. McCain, “Correlation of Black Oil Properties at Pressures below Bubble Point Pressure—A New Approach,” CIM 50-Year Commemorative Volume, Canadian Institute of Mining, 1999.

22. J. P. Spivey, P. P. Valko, and W. D. McCain, “Applications of the Coefficient of Isothermal Compressibility to Various Reservoir Situations with New Correlations for Each Situation,” SPE Res. Eval. & Eng. (2007), 10, No. 1, 43–49.

23. A. J. Villena-Lanzi, “A Correlation for the Coefficient of Isothermal Compressibility of Black Oil at Pressures below the Bubble Point,” master’s thesis, Texas A&M University, 1985, College Station, TX.

24. E. O. Egbogah, “An Improved Temperature-Viscosity Correlation for Crude Oil Systems,” paper 83-34-32, presented at the 1983 Annual Technical Meeting of the Petroleum Society of CIM, May 10–13, 1983, Alberta, Canada.

25. H. D. Beggs, “Oil System Correlations,” Petroleum Engineering Handbook, ed. H. C. Bradley, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1987.

26. H. D. Beggs and J. R. Robinson, “Estimating the Viscosity of Crude Oil Systems,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (Sept. 1975), 1140–41.

27. G. E. Petrosky and F. F. Farshad, “Viscosity Correlations for Gulf of Mexico Crude Oils,” paper SPE 29468, presented at the SPE Production Operations Symposium, 1995, Oklahoma City.

28. W. D. McCain Jr., “Reservoir-Fluid Property Correlations: State of the Art,” SPERE (May 1991), 266.

29. T. L. Osif, “The Effects of Salt, Gas, Temperature, and Pressure on the Compressibility of Water,” SPERE (Feb. 1988), 175–81.