In the previous four chapters, the material balance equations for each of the four reservoir types defined in Chapter 1 were developed. These material balance equations may be used to calculate the production of oil and/or gas as a function of reservoir pressure. The reservoir engineer, however, would like to know the production as a function of time. To learn this, it is necessary to develop a model containing time or some related property, such as flow rate.

This chapter contains a detailed discussion of Darcy’s law as it applies to hydrocarbon reservoirs. The discussion will consider four major influences on fluid flow, their effect on the reservoir fluid, and the manipulation of Darcy’s law to account for these influences. The first major influence is the number of phases present. This chapter will consider only single-phase flow regimes. Subsequent chapters will investigate specific applications of multiphase flow. The second major influence is the compressibility of the fluid. Third is the geometry of the flow system, namely linear, radial, or spherical flow. Fourth is the time dependence of the flow system. Steady state will be considered first, followed by transient, late-transient, and pseudosteady state. The chapter concludes with an introduction to pressure transient testing methods that aid the reservoir engineer in getting information such as average permeability, damage around a wellbore, and drainage area of a particular production well.

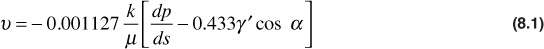

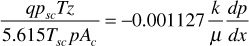

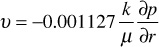

In 1856, as a result of experimental studies on the flow of water through unconsolidated sand filter beds, Henry Darcy formulated the law that bears his name. This law has been extended to describe, with some limitations, the movement of other fluids, including two or more immiscible fluids, in consolidated rocks and other porous media. Darcy’s law states that the velocity of a homogeneous fluid in a porous medium is proportional to the driving force and inversely proportional to the fluid viscosity, or

where

ν = the apparent velocity, bbl/day-ft2

k = permeability, millidarcies (md)

μ = fluid viscosity, cp

p = pressure, psia

s = distance along flow path in ft

γ’ = fluid specific gravity (always relative to water)

α = the angle measured counterclockwise from the downward vertical to the positive s direction

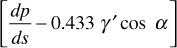

and the term

represents the driving force. The driving force may be caused by fluid pressure gradients (dp/ds) and/or hydraulic (gravitational) gradients (0.433γ’ cos α). In many cases of practical interest, the hydraulic gradients, although always present, are small compared with the fluid pressure gradients and are frequently neglected. In other cases, notably production by pumping from reservoirs whose pressures have been depleted and gas-cap expansion reservoirs with good gravity drainage characteristics, the hydraulic gradients are important and must be considered.

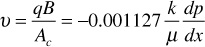

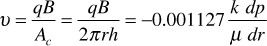

The apparent velocity, ν, is equal to qB/A, where q is the volumetric flow rate in STB/day, B is the formation volume factor, and A is the apparent or total area of the bulk rock material in square feet perpendicular to the flow direction. A includes the area of the solid rock material as well as the area of the pore channels. The fluid pressure gradient, dp/ds, is taken in the same direction as ν and q. The negative sign in front of the constant 0.001127 indicates that if the flow is taken as positive in the positive s-direction, then the pressure decreases in that direction, so the slope dp/ds is negative.

Darcy’s law applies only in the region of laminar flow characterized by low fluid velocities; in turbulent flow, which occurs at high fluid velocities, the pressure gradient is dependent on the flow rate but usually increases at a greater rate than does the flow rate. Fortunately, Darcy’s law is valid for liquid flow, except for some instances of quite large production or injection rates in the vicinity of the wellbore, the flow in the reservoir, and most laboratory tests. However, gas flowing near the wellbore is likely to be subject to non-Darcy flow. Darcy’s law does not apply to flow within individual pore channels but to portions of a rock, the dimensions of which are reasonably large compared with the size of the pore channels. In other words, it is a statistical law that averages the behavior of many pore channels. For this reason, although samples with dimensions of a centimeter or two are satisfactory for permeability measurements on uniform sandstones, much larger samples are required for reliable measurements of fracture and vugular-type rocks.

Owing to the porosity of the rock, the tortuosity of the flow paths, and the absence of flow in some of the (dead) pore spaces, the actual fluid velocity within pore channels varies from point to point within the rock and maintains an average that is many times the apparent bulk velocity. Because actual velocities are in general not measurable, and to keep porosity and permeability separated, apparent velocity forms the basis of Darcy’s law. This means the actual average forward velocity of a fluid is the apparent velocity divided by the porosity where the fluid completely saturates the rock.

A basic unit of permeability is the darcy (d). A rock of 1-d permeability is one in which a fluid of 1-cp viscosity will move at a velocity of 1 cm/sec under a pressure gradient of 1 atm/cm. Since this is a fairly large unit for most producing rocks, permeability is commonly expressed in units one thousandth as large, the millidarcy, or 0.001 d. Throughout this text, the unit of permeability used is the millidarcy (md). Conventional oil and gas sands have permeabilities varying from a few millidarcies to several thousands. Intergranular limestone permeabilities may be only a fraction of a millidarcy and yet be commercial if the rock contains additional natural or artificial fractures or other kinds of openings. Fractured and vugular rocks may have enormous permeabilities, and some cavernous limestones approach the equivalent of underground tanks. In recent years, unconventional reservoirs have been developed with permeabilities in the microdarcy (1μd = 10–6 d) or even nanodarcy (1 nd = 10–9 d) range.

The permeability of a sample as measured in the laboratory may vary considerably from the average of the reservoir as a whole or a portion thereof. There are often wide variations both laterally and vertically, with the permeability sometimes changing several fold within an inch in rock that appears quite uniform. Generally, the permeability measured parallel to the bedding planes of stratified rocks is larger than the vertical permeability. Also, in some cases, the permeability along the bedding plane varies considerably and consistently with core orientation, owing presumably to the oriented deposition of more or less elongated particles and/or the subsequent leaching or cementing action of migrating waters. Some reservoirs show general permeability trends from one portion to another, and many reservoirs are closed on all or part of their boundaries by rock of very low permeability, certainly by the overlying caprock. The occurrence of one or more strata of consistent permeability over a portion or all of a reservoir is common. In the proper development of reservoirs, it is customary to core selected wells throughout the productive area measuring the permeability and porosity on each foot of core recovered. The results are frequently handled statistically.1,2 In very heterogeneous reservoirs, especially carbonates, it may be that no core is retrieved from the most productive intervals because they are highly fractured or even rubblized. For such reservoirs core-derived permeability statistics may be very conservative or even misleadingly low.

Hydraulic gradients in reservoirs vary from a maximum near 0.500 psi/ft for brines to 0.433 psi/ft for fresh water at 60°F, depending on the pressure, temperature, and salinity of the water. Reservoir oils and high-pressure gas and gas-condensate gradients lie in the range of 0.10–0.30 psi/ft, depending on the temperature, pressure, and composition of the fluid. Gases at low pressure will have very low gradients (e.g., about 0.002 psi/ft for natural gas at 100 psia). The figures given are the vertical gradients. The effective gradient is reduced by the factor cos α. Thus a reservoir oil with a reservoir specific gravity of 0.60 will have a vertical gradient of 0.260 psi/ft; however, if the fluid is constrained to flow along the bedding plane of its stratum, which dips at 15° (α = 75°), then the effective hydraulic gradient is only 0.26 cos 75°, or 0.067 psi/ft. Although these hydraulic gradients are small compared with usual reservoir pressures, the fluid pressure gradients, except in the vicinity of wellbores, are also quite small and in the same range. Fluid pressure gradients within a few feet of wellbores may be as high as tens of psi per foot due to the flow into the wellbore but will fall off rapidly away from the well, inversely with the radius.

Frequently, static pressures measured from well tests are corrected to the top of the production (perforated) interval with a knowledge of the reservoir fluid gradient. They also can be adjusted to a common datum level for a given reservoir by using the same reservoir fluid gradient. Example 8.1 shows the calculation of apparent velocity by two methods. The first is by correcting the well pressures to the datum level using information about hydraulic gradients. The second is by using Eq. (8.1).

Example 8.1 Calculating Datum Level Pressures, Pressure Gradients, and Reservoir Flow from Static Pressure Measurements in Wells

Given

Distance between wells (see Fig. 8.1)

Figure 8.1 Cross section between the two wells of Example 8.1. Note exaggerated vertical scale.

True stratum thickness = 20 ft

Dip of stratum between wells = 8° 37′

Reservoir datum level = 7600 ft subsea

Reservoir fluid specific gravity = 0.693 (water = 1.00)

Reservoir permeability = 145 md

Reservoir fluid viscosity = 0.32 cp

Well number 1 static pressure = 3400 psia at 7720 ft subsea

Well number 2 static pressure = 3380 psia at 7520 ft subsea

First Solution

Reservoir fluid gradient = Reservoir fluid specific gravity × Hydraulic gradient fresh water = 0.693 × 0.433 = 0.300 psi/ft

p1 at 7600 ft datum = Well number 1 static pressure – (Elevation difference of well number 1 and datum × Reservoir fluid gradient) = 3400 – 120 × 0.30 = 3364 psia

p2 at 7600 ft datum = Well number 2 static pressure + (Elevation difference of well number 2 and datum × Reservoir fluid gradient) = 3380 + 80 × 0.30 = 3404 psia

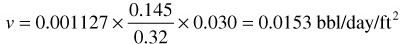

The difference of 40 psi indicates that fluid is moving downdip, from well 2 to well 1. The average effective gradient is 40/1335 = 0.030 psi/ft, where 1335 is the distance along the stratum between the wells. The velocity then is

v = 0.001127 × (Reservoir permeability / Reservoir fluid viscosity) × Average effective gradient

Second Solution

Take the positive direction from well 1 to well 2. Then α = 98° 37′ and cos α = –0.1458.

v = –0.0153 bbl/day/sq ft

The negative sign indicates that fluid is flowing in the negative direction (i.e., from well 2 to well 1).

Equation (8.1) suggests that the velocity and pressure gradient are related by the mobility. The mobility, given the symbol λ, is the ratio of permeability to viscosity, k/μ. The mobility appears in all equations describing the flow of single-phase fluids in reservoir rocks. When two fluids are flowing simultaneously—for example, gas and oil to a wellbore, it is the ratio of the mobility of the gas, λg, to that of the oil, λo, that determines their individual flow rates. The mobility ratio M (see Chapter 10) is an important factor affecting the displacement efficiency of oil by water. When one fluid displaces another, the standard notation for the mobility ratio is the mobility of the displacing fluid to that of the displaced fluid. For water-displacing oil, it is λw/λo.

Reservoir flow systems are usually classed according to (1) the compressibility of fluid, (2) the geometry of the reservoir or portion thereof, and (3) the relative rate at which the flow approaches a steady-state condition following a disturbance.

For most engineering purposes, the reservoir fluid may be classed as (1) incompressible, (2) slightly compressible, or (3) compressible. The concept of the incompressible fluid, the volume of which does not change with pressure, simplifies the derivation and the final form of many equations. However, the engineer should realize that there are no truly incompressible fluids.

A slightly compressible fluid, which is the description of nearly all liquids, is sometimes defined as one whose volume change with pressure is quite small and expressible by the equation

where

R = reference conditions

The exponential term in Eq. (8.2) can be expanded and approximated, due to the typically small value of c(pR – p), to yield the following:

A compressible fluid is one in which the volume has a strong dependence on pressure. All gases are in this category. In Chapter 2, the real gas law was used to describe how gas volumes vary with pressure:

Unlike the case of the slightly compressible fluids, the gas isothermal compressibility, cg, cannot be treated as a constant with varying pressure. In fact, the following expression for cg was developed:

Although fluids are typed mainly by their compressibilities, in addition, there may be single phase or multiphase flow. Many systems are only gas, oil, or water, and most of the remainder are either gas-oil or oil-water systems. For the purposes of this chapter, discussion is restricted to cases where there is only a single phase flowing.

The two geometries of greatest practical interest are those that give rise to linear and radial flow. In linear flow, as shown in Fig. 8.2, the flow lines are parallel and the cross section exposed to flow is constant. In radial flow, the flow lines are straight and converge in two dimensions toward a common center (i.e., a well or cylinder). The cross section exposed to flow decreases as the center is approached. Occasionally, spherical flow is of interest, in which the flow lines are straight and converge toward a common center (point) in three dimensions. Although the actual paths of the fluid particles in rocks are irregular due to the shape of the pore spaces, the overall or average paths may be represented as straight lines in linear, radial, or spherical flow.

Actually, none of these geometries is found precisely in petroleum reservoirs, but for many engineering purposes, the actual geometry may often be closely represented by one of these idealizations. In some types of reservoir studies (i.e., waterflooding and gas cycling), these idealizations are inadequate, and more sophisticated models are commonly used in their stead.

Flow systems in reservoir rocks are classified, according to their time dependence, as steady state, transient, late transient, or pseudosteady state. During the life of a well or reservoir, the type of system can change several times, which suggests that it is critical to know as much about the flow system as possible in order to use the appropriate model to describe the relationship between the pressure and the flow rate. In steady-state systems, the pressure and fluid saturations at every point throughout the system do not change. An approximation to the steady-state condition occurs when any production from a reservoir is replaced with an equal mass of fluid from some external source. In Chapter 9, a case of water influx is considered that comes close to meeting this requirement, but in general, there are very few systems that can be assumed to have steady-state conditions.

To consider the remaining three classifications of time dependence, changes in pressure are discussed that occur when a step change in the flow rate of a well located in the center of a reservoir, as illustrated in Fig. 8.3, causes a pressure disturbance in the reservoir. The discussion assumes the following: (1) the flow system is made up of a reservoir of constant thickness and rock properties, (2) the radius of the circular reservoir is re, and (3) the flow rate is constant before and after the rate change. As the flow rate is changed at the well, the movement of pressure begins to occur away from the well. The movement of pressure is a diffusion phenomenon and is modeled by the diffusivity equation (see section 8.5). The pressure moves at a rate proportional to the formation diffusivity, η,

where k is the effective permeability of the flowing phase, φ is the total effective porosity, μ is the fluid viscosity of the flowing phase, and ct is the total compressibility. The total compressibility is obtained by weighting the compressibility of each phase by its saturation and adding the formation compressibility, or

The formation compressibility, cf, should be expressed as the change in pore volume per unit pore volume per psi. During the time the pressure is traveling at this rate, the flow state is said to be transient. While the pressure is in this transient region, the outer boundary of the reservoir has no influence on the pressure movement, and the reservoir acts as if it were infinite in size.

The late transient region is the period after the pressure has reached the outer boundary of the reservoir and before the pressure behavior has had time to stabilize in the reservoir. In this region, the pressure no longer travels at a rate proportional to η. It is very difficult to describe the pressure behavior during this period.

The fourth period, the pseudosteady state, is the period after the pressure behavior has stabilized in the reservoir. During this period, the pressure at every point throughout the reservoir is changing at a constant rate and as a linear function of time. This period is often incorrectly referred to as the steady-state period.

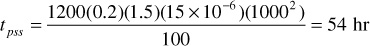

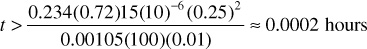

An estimation for the time when a flow system of the type shown in Fig. 8.3 reaches pseudosteady state can be made from the following equation:

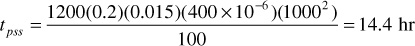

where tpss is the time to reach the pseudosteady state, expressed in hours.3 For a well producing an oil with a reservoir viscosity of 1.5 cp and a total compressibility of 15 × 10–6 psi–1, from a circular reservoir of 1000-ft radius with a permeability of 100 md and a total effective porosity of 20%:

This means that approximately 54 hours, or 2.25 days, is required for the flow in this reservoir to reach pseudosteady-state conditions after a well located in its center is opened to flow or following a change in the well flow rate. It also means that if the well is shut in, it will take approximately this time for the pressure to equalize throughout the drainage area of the well, so that the measured subsurface pressure equals the average drainage area pressure of the well.

This same criterion may be applied approximately to gas reservoirs but with less certainty because the gas is more compressible. For a gas viscosity of 0.015 cp and a compressibility of 400 × 10–6 psi–1,

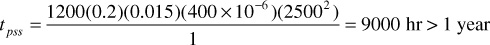

Thus, under somewhat comparable conditions (i.e., the same re and k), gas reservoirs reach pseudosteady-state conditions more rapidly than oil reservoirs. This is due to the much lower viscosity of gases, which more than offsets the increase in fluid compressibility. On the other hand, gas wells are usually drilled on wider spacings so that the value of re generally is larger for gas wells than for oil wells, thus increasing the time required to reach the pseudosteady state. Many gas reservoirs, such as those found in the overthrust belt, are sands of low permeability. Using an re value of 2500 ft and a permeability of 1 md, which would represent a tight gas sand, then the following value for tpss is calculated:

The calculations suggest that reaching pseudosteady-state conditions in a typical tight gas reservoir takes a very long time compared to a typical oil reservoir. In general, pseudosteady-state mechanics suffice when the time required to reach pseudosteady state is short compared with the time between substantial changes in the flow rate or, in the case of reservoirs, with the total producing life of the reservoir. Many wells are not produced at a constant rate, and instead, the flowing pressure may be approximately constant. For such wells during the transient flow condition, the pressure disturbance still moves at the same velocity, and at the time of pseudosteady state, the well reaches a boundary-dominated condition.

Now that Darcy’s law has been reviewed and the classification of flow systems has been discussed, the actual models that relate flow rate to reservoir pressure can be developed. The next several sections contain a discussion of the steady-state models. Both linear and radial flow geometries are discussed since there are many applications for these types of systems. For both the linear and radial geometries, equations are developed for all three general types of fluids (i.e., incompressible, slightly compressible, and compressible).

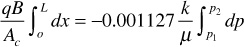

Figure 8.4 represents linear flow through a body of constant cross section, where both ends are entirely open to flow and where no flow crosses the sides, top, or bottom. If the fluid is incompressible, or essentially so for all engineering purposes, then the velocity is the same at all points, as is the total flow rate across any cross section; thus, in horizontal flow,

Separating variables and integrating over the length of the porous body,

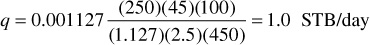

For example, under a pressure differential of 100 psi for a permeability of 250 md, a fluid viscosity of 2.5 cp, a formation volume factor of 1.127 bbl/STB, a length of 450 ft, and a cross-sectional area of 45 sq ft, the flow rate is

In this integration, B, q, μ, and k were removed from the integral sign, assuming they were invariant with pressure. Actually, for flow above the bubble point, the volume, and hence the rate of flow, varies with the pressure, as expressed by Eq. (8.2). The formation volume factor and viscosity also vary with pressure, as explained in Chapter 2. Fatt and Davis have shown a variation in permeability with net overburden pressure for several sandstones.4 The net overburden pressure is the gross less the internal fluid pressure; therefore, a variation of permeability with pressure is indicated, particularly in the shallower reservoirs. Because these effects are negligible for a few hundred-psi pressure difference, values at the average pressure may be used for most purposes.

The equation for flow of slightly compressible fluids is modified from what was just derived in the previous section, since the volume of slightly compressible fluids increases as pressure decreases. Earlier in this chapter, Eq. (8.3) was derived, which describes the relationship between pressure and volume for a slightly compressible fluid. The product of the flow rate, defined in STB units, and the formation volume factor have similar dependencies on pressure. The product of the flow rate is given by

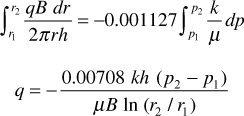

where qR is the flow rate at some reference pressure, pR. If Darcy’s law is written for this case, with variables separated and the resulting equation integrated over the length of the porous body, then the following is obtained:

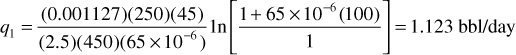

This integration assumes a constant compressibility over the entire pressure drop. For example, under a pressure differential of 100 psi for a permeability of 250 md, a fluid viscosity of 2.5 cp, a length of 450 ft, a cross-sectional area of 45 sq ft, and a constant compressibility of 65(10–6) psi–1, choosing p1 as the reference pressure, the flow rate is

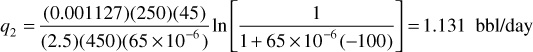

When compared with the flow rate calculation in the preceding section, q1 is found to be different due to the assumption of a slightly compressible fluid in the calculation rather than an incompressible fluid. Note also that the flow rate is not in STB units because the calculation is being done at a reference pressure that is not the standard pressure. If p2 is chosen to be the reference pressure, then the result of the calculation will be q2, and the value of the calculated flow rate will be different still because of the volume dependence on the reference pressure:

The calculations show that q1 and q2 are not largely different, which confirms what was discussed earlier: the fact that volume is not a strong function of pressure for slightly compressible fluids.

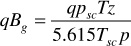

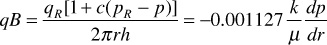

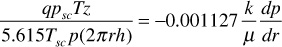

The rate of flow of gas expressed in standard cubic feet per day is the same at all cross sections in a steady-state, linear system. However, because the gas expands as the pressure drops, the velocity is greater at the downstream end than at the upstream end, and consequently, the pressure gradient increases toward the downstream end. The flow at any cross section x of Fig. 8.4 where the pressure is p may be expressed in terms of the flow in standard cubic feet per day by substituting the definition of the gas formation volume factor:

Substituting in Darcy’s law,

Separating variables and integrating,

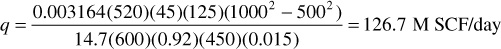

Finally,

For example, where Tsc = 60°F, Ac = 45 ft2, k = 125 md, p1 = 1000 psia, p2 = 500 psia, psc = 14.7 psia, T = 140°F, z = 0.92, L = 450 ft, and μ = 0.015 cp,

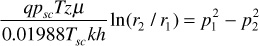

Here again, T, k, and the product μz were withdrawn from the integrals as if they were invariant with pressure, and as before, average values may be used in this case. At this point, it is instructive to examine an observation that Wattenbarger and Ramey made about the behavior of the gas deviation factor—viscosity product as a function of pressure.5 Figure 8.5 is a typical plot of μz versus pressure for a real gas. Note that the product, μz, is nearly constant for pressures less than about 2000 psia. Above 2000 psia, the product μz/p is nearly constant. Although the shape of the curve varies slightly for different gases at different temperatures, the pressure dependence is representative of most natural gases of interest. The pressure at which the curve bends varies from about 1500 psia to 2000 psia for various gases. This variation suggests that Eq. (8.10) is valid only for pressures less than about 1500 psia to 2000 psia, depending on the properties of the flowing gas. Above this pressure range, it would be more accurate to assume that the product μz/p is constant. For the case of μz/p constant, the following is obtained:

In applying Eq. (8.11), the product μz/p should be evaluated at the average pressure between p1 and p2.

Al-Hussainy, Ramey, and Crawford, and Russel, Goodrich, Perry, and Bruskotter introduced a transformation of variables that leads to another solution for gas flow in the steady-state region.6,7 The transformation involves the real gas pseudopressure, m(p), which has units of psia2/cp in standard field units and is defined as

where pR is a reference pressure, usually chosen to be 14.7 psia, from which the function is evaluated. Using the real gas pseudopressure, the equation for gas flowing under steady-state conditions becomes

The use of Eq. (8.13) requires values of the real gas pseudopressure. The procedure used to find values of m(p) has been discussed in the literature.8,9 The procedure involves determining μ and z for several pressures over the pressure range of interest, using the methods of Chapter 2. Values of p/μz are then calculated, and a plot of p/μz versus p is made, as illustrated in Fig. 8.6. A numerical integration scheme such as Simpson’s rule is then used to determine the value of the area from the reference pressure up to a pressure of interest, p1. The value of m (p1) that corresponds with pressure, p1, is given by

m(p1) = 2 (area1)

where

The real gas pseudopressure method can be applied at any pressure of interest if the data are available.

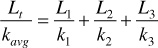

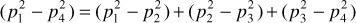

Consider two or more beds of equal cross section but of unequal lengths and permeabilities (Fig. 8.7, depicting flow in series) in which the same linear flow rate q exists, assuming an incompressible fluid. Obviously the pressure drops are additive, and

(p1 – p4) = (p1 – p2) + (p2 – p3) + (p3 – p4)

Substituting the equivalents of these pressure drops from Eq. (8.7),

But since the flow rates, cross sections, viscosities, and formation volume factors (neglecting the change with pressure) are equal in all beds,

or

The average permeability as defined by Eq. (8.14) is that permeability to which a number of beds of various geometries and permeabilities could be approximated by and yield the same total flow rate under the same applied pressure drop.

Equation (8.14) was derived using the incompressible fluid equation. Because the permeability is a property of the rock and not of the fluids flowing through it, except for gases at low pressure, the average permeability must be equally applicable to gases. This requirement may be demonstrated by observing that, for pressures below 1500 psia to 2000 psia,

Substituting the equivalents from Eq. (8.10), the same Eq. (8.14) is obtained.

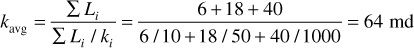

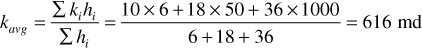

The average permeability of 10 md, 50 md, and 1000 md beds (which are 6 ft, 18 ft, and 40 ft in length, respectively, but of equal cross section) when placed in series is

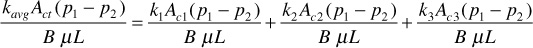

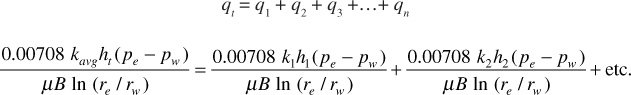

Consider two or more beds of equal length but unequal cross sections and permeabilities flowing the same fluid in linear flow under the same pressure drop (p1 to p2), as shown in Fig. 8.8, depicting parallel flow. Obviously the total flow is the sum of the individual flows, or

qt = q1 + q2 + q3

canceling

And where all beds are of the same width, so that their areas are proportional to their thicknesses,

Where the parallel beds are homogeneous in permeability and fluid content, the pressure and the pressure gradient are the same in all beds at equal distances. Thus there will be no cross flow between beds, owing to fluid pressure differences. However, when water displaces oil—for example from a set of parallel beds—the rates of advance of the flood fronts will be greater in the more permeable beds. Because the mobility of the oil (ko/μo) ahead of the flood front is different from the mobility of water (kw/μw) behind the flood front, the pressure gradients will be different. In this instance, there will be pressure differences between two points at the same distance through the rock, and cross flow will take place between the beds if they are not separated by impermeable barriers. Under these circumstances, Eqs. (8.15) and (8.16) are not strictly applicable, and the average permeability changes with the stage of displacement. Water may also move from the more permeable to the less permeable beds by capillary action, which further complicates the study of parallel flow.

The average permeability of three beds of 10 md, 50 md, and 1000 md and 6 ft, 18 ft, and 36 ft, respectively, in thickness but of equal width, when placed in parallel is

Although the pore spaces within rocks seldom resemble straight, smooth-walled capillary tubes of constant diameter, it is often convenient and instructive to treat these pore spaces as if they were composed of bundles of parallel capillary tubes of various diameters. Consider a capillary tube of length L and inside radius ro, which is flowing an incompressible fluid of μ viscosity in laminar or viscous flow under a pressure difference of (p1 – p2). From fluid dynamics, Poiseuille’s law, which describes the total flow rate through the capillary, can be written as

Darcy’s law for the linear flow of incompressible fluids in permeable beds, Eq. (8.7), and Poiseuille’s law for incompressible fluid capillary flow, Eq. (8.15), are quite similar:

Writing  for area in Eq. (8.7) and equating it to Eq. (8.17),

for area in Eq. (8.7) and equating it to Eq. (8.17),

Thus the permeability of a rock composed of closely packed capillaries, each having a radius of 4.17(10)–6 ft (0.00005 in.), is about 200 md. And if only 25% of the rock consists of pore channels (i.e., it has 25% porosity), the permeability is about one-fourth as large, or about 50 md.

An equation for the viscous flow of incompressible wetting fluids through smooth fractures of constant width may be obtained as

In Eq. (8.19), W is the width of the fracture; Ac is the cross-sectional area of the fracture, which equals the product of the width W and lateral extent of the fracture; and the pressure difference is that which exists between the ends of the fracture of length L. Equation (8.19) may be combined with Eq. (8.7) to obtain an expression for the permeability of a fracture as

The permeability of a fracture only 8.33(10)–5 ft wide (0.001 in.) is 53,500 md.

Fractures and solution channels account for economic production rates in many dolomite, limestone, and sandstone rocks, which could not be produced economically if such openings did not exist. Consider, for example, a rock of very low primary or matrix permeability, say 0.01 md, that contains on the average a fracture 4.17(10)–4 ft wide and 1 ft in lateral extent per square foot of rock. Assuming the fracture is in the direction in which flow is desired, the law of parallel flow, Eq. (8.15), will apply, and

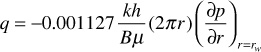

Consider radial flow toward a vertical wellbore of radius rw in a horizontal stratum of uniform thickness and permeability, as shown in Fig. 8.9. If the fluid is incompressible, the flow across any circumference is a constant. Let pw be the pressure maintained in the wellbore when the well is flowing q STB/day and a pressure pe is maintained at the external radius re. Let the pressure at any radius r be p. Then at this radius r,

where positive q is in the positive r direction. Separating variables and integrating between any two radii, r1 and r2, where the pressures are p1 and p2, respectively,

The minus sign is usually dispensed with, for where p2 is greater than p1, the flow is known to be negative—that is, in the negative r direction, or toward the wellbore:

Frequently the two radii of interest are the wellbore radius rw and the external or drainage radius re. Then

The external radius is usually inferred from the well spacing. For example, a circle of 660 ft radius can be inscribed within a square 40 ac unit, so 660 ft is commonly used for re with 40 ac spacing. Sometimes a radius of 745 ft is used, this being the radius of a circle 40 ac in area. The wellbore radius is usually assigned from the bit diameter, the casing diameter, or a caliper survey. In practice, neither the external radius nor the wellbore radius is generally known with precision. Fortunately, they enter the equation as a logarithm, so that the error in the equation will be much less than the errors in the radii. Since wellbore radii are about 1/3 ft and 40 ac spacing (rc = 660 ft) is quite common, a ratio 2000 is quite commonly used for re/rw. Since ln 2000 is 7.60 and ln 3000 is 8.00, a 50% increase in the value of re/rw gives only a 5.3% increase in the value of the logarithm.

The external pressure pe used in Eq. (8.21) is generally taken as the static well pressure corrected to the middle of the producing interval, and the flowing well pressure pw is the flowing well pressure also corrected to the middle of the producing interval during a period of stabilized flow at rate q. When reservoir pressure stabilizes as under natural water drive or pressure maintenance, Eq. (8.21) is quite applicable because the pressure is maintained at the external boundary, and the fluid produced at the well is replaced by fluid crossing the external boundary. The flow, however, may not be strictly radial.

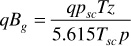

Equation (8.3) is again used to express the volume dependence on pressure for slightly compressible fluids. If this equation is substituted into the radial form of Darcy’s law, the following is obtained:

Separating the variables, assuming a constant compressibility over the entire pressure drop, and integrating over the length of the porous medium,

The flow of a gas at any radius r of Fig. 8.8, where the pressure is p, may be expressed in terms of the flow in standard cubic feet per day by

Substituting in the radial form of Darcy’s law,

Separating variables and integrating,

or

Finally,

The product μz has been assumed to be constant for the derivation of Eq. (8.23). It was pointed out in section 8.4.3 that this is usually true only for pressures less than about 1500 psia to 2000 psia. For greater pressures, it was stated that a better assumption was that the product μz/p was constant. For this case, the following is obtained:

Applying Eqs. (8.23) and (8.24), the products μz and μz/p should be calculated at the average pressure between p1 and p2.

If the real gas pseudopressure function is used, the equation becomes

Many producing formations are composed of strata or stringers that may vary widely in permeability and thickness, as illustrated in Fig. 8.10. If these strata are producing fluid to a common wellbore under the same drawdown and from the same drainage radius, then

Then, canceling,

This equation is the same as for parallel flow in linear beds with the same bed width. Here, again, average permeability refers to that permeability by which all beds could be replaced and still obtain the same production rate under the same drawdown. The product kh is called the flow capacity or transmissivity of a bed or stratum, and the total flow capacity of the producing formation, ∑kihi, is usually expressed in millidarcy-feet. Because the rate of flow is directly proportional to the flow capacity, Eq. (8.21), a 10-ft bed of 100 md will have the same production rate as a 100-ft bed of 10-md permeability, other things being equal. There are limits of formation flow capacity below which production rates are not economic, just as there are limits of net productive formation thicknesses below which wells will never pay out. Of two formations with the same flow capacity, the one with the lower oil viscosity may be economic but the other may not, and the available pressure drawdown enters in similarly. Net sand thicknesses of the order of 5 ft and capacities of the order of a few hundred millidarcy-feet are likely to be uneconomic, depending on other factors such as available drawdown, viscosity, porosity, connate water, depth, and the like, or will require hydraulic fracture stimulation. The flow capacity of the formation together with the viscosity also determines to a large extent whether a well will flow or whether artificial lift must be used. The amount of solution gas is an important factor. With hydraulic fracturing (to be discussed later), the well productivity in low flow capacity reservoirs can be greatly improved.

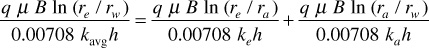

We now consider a radial flow system of constant thickness with a permeability of ke between the drainage radius re and some lesser radius ra and an altered permeability ka between the radius ra and the wellbore radius rw, as shown in Fig. 8.11. The pressure drops are additive, and

(pe – pw) = (pe – pa) + (pa – pw)

Then, from Eq. (8.21),

Canceling and solving for kavg,

Equation (8.27) may be extended to include three or more zones in series. This equation is important in studying the effect of a decrease or increase of permeability in the zone about the wellbore on the well productivity.

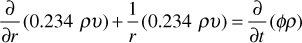

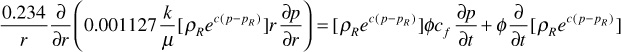

The radial diffusivity equation, which is the general differential equation used to model time-dependent flow systems, is now developed. Consider the volume element shown in Fig. 8.12. The element has a thickness Δr and is located r distance from the center of the well. Mass is allowed to flow into and out of the volume element during a period Δt. The volume element is in a reservoir of constant thickness and constant properties. Flow is allowed in only the radial direction. The following nomenclature, which is the same nomenclature defined previously, is used:

q = volume flow rate, STB/day for incompressible and slightly compressible fluids and SCF/day for compressible fluids

ρ = density of flowing fluid at reservoir conditions, lb/ft3

r = distance from wellbore, ft

h = formation thickness, ft

ν = velocity of flowing fluid, bbl/day-ft2

t = hours

φ = porosity, fraction

k = permeability, md

μ = flowing fluid viscosity, cp

With these assumptions and definitions, a mass balance can be written around the volume element over the time interval Δt. In word form, the mass balance is written as

Mass entering volume element during interval Δt – Mass leaving volume element during interval Δt = Change of mass in volume element during interval Δt

The mass entering the volume element during Δt is given by

The mass leaving the volume element during Δt is given by

The change of mass in the element during the interval Δt is given by

Combining Eqs. (8.28), (8.29), and (8.30), as suggested by the word “equation” written above,

2π(r+r)h(ρυ(5.615/24)Δt)r+Δr –2πrh(ρυ(5.615/24)Δt)r = 2πrΔrh[(φρ)t + Δt – (φρ)t]

If both sides of this equation are divided by 2πrΔrhΔt and the limit is taken in each term as Δr and Δt approach zero, the following is obtained:

or

Equation (8.31) is the continuity equation and is valid for any flow system of radial geometry. To obtain the radial differential equation that will be the basis for time-dependent models, pressure must be introduced and φ eliminated from the partial derivative term on the right-hand side of Eq. (8.31). To do this, Darcy’s equation must be introduced to relate the fluid flow rate to reservoir pressure:

Realizing that the minus sign can be dropped from Darcy’s equation because of the sign convention for fluid flow in porous media and substituting Darcy’s equation into Eq. (8.31),

The porosity from the partial derivative term on the right-hand side is eliminated by expanding the right-hand side and taking the indicated derivatives:

It can be shown that porosity is related to the formation compressibility by the following:

Applying the chain rule of differentiation to ∂φ/∂t,

Substituting Eq. (8.34) into this equation,

Finally, substituting this equation into Eq. (8.33) and the result into Eq. (8.29),

Equation (8.35) is the general partial differential equation used to describe the flow of any fluid flowing in a radial direction in porous media. In addition to the initial assumptions, Darcy’s equation has been added, which implies that the flow is laminar. Otherwise, the equation is not restricted to any type of fluid or any particular time region.

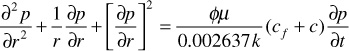

By applying appropriate boundary and initial conditions, particular solutions to the differential equation derived in the preceding section can be discussed. The solutions obtained pertain to the transient and pseudosteady-state flow periods for both slightly compressible and compressible fluids. Since the incompressible fluid does not exist, solutions involving this type of fluid are not discussed. Only the radial flow geometry is considered because it is the most useful and applicable geometry. If the reader is interested in linear flow, Matthews and Russell present the necessary equations.10 Also, due to the complex nature of the pressure behavior during the late-transient period, solutions of the differential equation for this time region are not considered. To further justify not considering flow models from this period, it is true that the most practical applications involve the transient and pseudosteady-state periods.

If Eq. (8.2) is expressed in terms of density, ρ, which is the inverse of specific volume, then the following is obtained:

where pR is some reference pressure and ρR is the density at that reference pressure. Inherent in this equation is the assumption that the compressibility of the fluid is constant. This is nearly always a good assumption over the pressure range of a given application. Substituting Eq. (8.36) into Eq. (8.35),

To simplify this equation, one must make the assumption that k and μ are constant over the pressure, time, and distance ranges in applying the equation. This is rarely true about k. However, if k is assumed to be a volumetric average permeability over these ranges, then the assumption is good. In addition, it has been found that viscosities of liquids do not change significantly over typical pressure ranges of interest. Making this assumption allows k/μ to be brought outside the derivative. Taking the necessary derivatives and simplifying,

or

The last term on the left-hand side of Eq. (8.37) causes this equation to be nonlinear and very difficult to solve. However, it has been found that the term is very small for most applications of fluid flow involving liquids. When this term becomes negligible for the case of liquid flow, Eq. (8.37) reduces to

This equation is the diffusivity equation in radial form. The name comes from its application to the radial flow of the diffusion of heat. Basically, the flow of heat, flow of electricity, and flow of fluids in permeable rocks can be described by the same mathematical forms. The group of terms φμct/k was previously defined to be equal to 1/η, where η is called the diffusivity constant (see section 8.3). This same constant was encountered in Eq. (8.6) for the readjustment time.

To obtain a solution to Eq. (8.38), it is necessary first to specify one initial and two boundary conditions. The initial condition is simply that at time t = 0, the reservoir pressure is equal to the initial reservoir pressure, pi. The first boundary condition is given by Darcy’s equation if it is required that there be a constant rate at the wellbore:

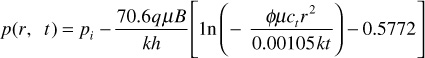

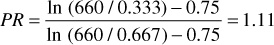

The second boundary condition is given by the fact that the desired solution is for the transient period. For this period, the reservoir behaves as if it were infinite in size. This suggests that at r = ∞, the reservoir pressure will remain equal to the initial reservoir pressure, pi. With these conditions, Matthews and Russel gave the following solution:

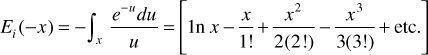

where all variables are consistent with units that have been defined previously—that is, p(r, t) and pi are in psia, q is in STB/day, μ is in cp, B (formation volume factor) is in bbl/STB, k is in md, h is in ft, ct is in psi–1, r is in ft, and t is in hr.10 Equation (8.39) is called the line source solution to the diffusivity equation and is used to predict the reservoir pressure as a function of time and position. The mathematical function, Ei, is the exponential integral and is defined by

This integral has been calculated as a function of x and is presented in Table 8.1, from which Fig. 8.13 was developed.

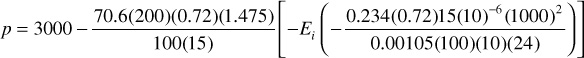

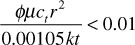

Equation (8.39) can be used to find the pressure drop (pi – p) that will have occurred at any radius about a flowing well after the well has flowed at a rate, q, for some time, t. For example, consider a reservoir where oil is flowing and μo = 0.72 cp, Bo = 1.475 bbl/STB, k = 100 md, h = 15 ft, ct = 15 × 10–6 psi–1, φ = 23.4%, and pi = 3000 psia. After a well is produced at 200 STB/day for 10 days, the pressure at a radius of 1000 ft will be

Thus

p = 3000 +10.0 Ei(–0.10)

From Fig. 8.13, Ei(–0.10) = –1.82. Therefore,

p = 3000 + 10.0 (–1.82) = 2981.8 psia

Figure 8.14 shows this pressure plotted on the 10-day curve and shows the pressure distributions at 0.1, 1.0, and 100 days for the same flow conditions.

It has been shown that, for values of the Ei function argument, less than 0.01 the following approximation can be made:

– Ei (– x) = –ln (x) – 0.5772

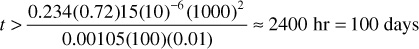

By rearranging the equation and solving for t, the time required to make this approximation valid for the pressure determination 1000 ft from the producing well can be found:

To determine if the approximation to the Ei function is valid when calculating the pressure at the sandface of a producing well, it is necessary to assume a wellbore radius, rw (0.25 ft), and to calculate the time that would make the approximation valid. The following is obtained:

It is apparent from these calculations that whether the approximation can be used is a strong function of the distance from the pressure disturbance to the point at which the pressure determination is desired or, in this case, from the producing well. For all practical purposes, the assumption is valid when considering pressures at the point of the disturbance. Therefore, at the wellbore and wherever the assumption is valid, Eq. (8.39) can be rewritten as

Substituting the log base 10 into this equation for the ln term, rearranging and simplifying, one gets

Equation (8.40) serves as the basis for a well testing procedure called transient well testing, a very useful technique that is discussed later in this chapter.

In section 8.5, Eq. (8.35)

was developed to describe the flow of any fluid flowing in a radial geometry in porous media. To develop a solution to Eq. (8.35) for the compressible fluid, or gas, case, two additional equations are required: (1) an equation of state, usually the real gas law, which is Eq. (2.8), and (2) Eq. (2.18), which describes how the gas isothermal compressibility varies with pressure:

These three equations can be combined to yield

Applying the real gas pseudopressure transformation to Eq. (8.41) yields the following:

Equation (8.42) is the diffusivity equation for compressible fluids, and it has a very similar form to Eq. (8.38), which is the diffusivity equation for slightly compressible fluids. The only difference in the appearance of the two equations is that Eq. (8.42) has the real gas pseudopressure, m(p), substituted for p. There is another significant difference that is not apparent from looking at the two equations. This difference is in the assumption concerning the magnitude of the (∂p/∂r)2 term in Eq. (8.41). To linearize Eq. (8.41), it is necessary to limit the term to a small value so that it results in a negligible quantity, which is normally the case for liquid flow applications. This limitation is not necessary for the gas equation. Since pressure gradients around the gas wells can be very large, the transformation of variables has led to a much more practical and useful equation for gases.

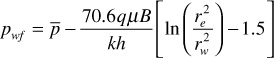

Equation (8.42) is still a nonlinear differential equation because of the dependence of μ and ct on pressure or the real gas pseudopressure. Thus, there is no analytical solution for Eq. (8.42). Al-Hussainy and Ramey, however, used finite difference techniques to obtain an approximate solution to Eq. (8.42).11 The result of their studies for pressures at the wellbore (i.e., where the logarithm approximation to the Ei function can be made) is the following equation:

where pwf is the flowing pressure at the wellbore; pi is the initial reservoir pressure; q is the flow rate in SCF/day at standard conditions of 60°F and 14.7 psia; T is the reservoir temperature in °R; k is in md; h is in ft; t is in hr; μi is in cp and is evaluated at the initial pressure, pi, cti is in psi–1 and is also evaluated at pi; and rw is the wellbore radius in feet. Equation (8.43) can be used to calculate the flowing pressure at the sandface of a gas well.

For the transient flow cases that were considered in the previous section, the well was assumed to be located in a very large reservoir. This assumption was made so that the flow from or to the well would not be affected by boundaries that would inhibit the flow. Obviously, the time that this assumption can be made is a finite amount and often is very short in length. As soon as the flow begins to feel the effect of a boundary, it is no longer in the transient regime. At this point, it becomes necessary to make a new assumption that will lead to a different solution to the radial diffusivity equation. The following sections discuss solutions to the radial diffusivity equation that allow calculations during the pseudosteady-state flow regime.

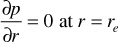

Once the pressure disturbance has been felt throughout the reservoir including at the boundary, the reservoir can no longer be considered as being infinite in size and the flow is not in the transient regime. This situation necessitates another solution to Eq. (8.38), using a different boundary condition at the outer boundary. The initial condition remains the same as before (i.e., the reservoir pressure is pi throughout the reservoir at time t = 0). The flow rate is again treated as constant at the wellbore. The new boundary condition used to find a solution to the radial diffusivity equation is that the outer boundary of the reservoir is a no-flow boundary. In mathematical terms,

Applying these conditions to Eq. (8.38), the solution for the pressure at the wellbore becomes

where A is the drainage area of the well in square feet and CA is a reservoir shape factor. Values of the shape factor are given in Table 8.2 for several reservoir types. Equation (8.44) is valid only for sufficiently long enough times for the flow to have reached the pseudosteady-state time period.

After reaching pseudosteady-state flow, the pressure at every point in the reservoir is changing at the same rate, which suggests that the average reservoir pressure is also changing at the same rate. The volumetric average reservoir pressure, which is usually designated as  and is the pressure used to calculate fluid properties in material balance equations, is defined as

and is the pressure used to calculate fluid properties in material balance equations, is defined as

where pj is the average pressure in the jth drainage volume and Vj is the volume of the jth drainage volume. It is useful to rewrite Eq. (8.44) in terms of the average reservoir pressure,  :

:

For a well in the center of a circular reservoir with a distance to the outer boundary of re, Eq. (8.46) reduces to

If this equation is rearranged and solved for q,

The differential equation for the flow of compressible fluids in terms of the real gas pseudopressure was derived in Eq. (8.42). When the appropriate boundary conditions are applied to Eq. (8.42), the pseudosteady-state solution rearranged and solved for q yields Eq. (8.48):

The ratio of the rate of production, expressed in STB/day for liquid flow, to the pressure drawdown at the midpoint of the producing interval, is called the productivity index, symbol J.

The productivity index (PI) is a measure of the well potential, or the ability of the well to produce, and is a commonly measured well property. To calculate J from a production test, it is necessary to flow the well a sufficiently long time to reach pseudosteady-state flow. Only during this flow regime will the difference between  and pwf be constant. It was pointed out in section 8.3 that once the pseudosteady-state period had been reached, the pressure changes at every point in the reservoir at the same rate. This is not true for the other periods, and a calculation of productivity index during other periods would not be accurate.

and pwf be constant. It was pointed out in section 8.3 that once the pseudosteady-state period had been reached, the pressure changes at every point in the reservoir at the same rate. This is not true for the other periods, and a calculation of productivity index during other periods would not be accurate.

In some wells, the PI remains constant over a wide variation in flow rate such that the flow rate is directly proportional to the bottom-hole pressure drawdown. In other wells, at higher flow rates the linearity fails, and the PI index declines, as shown in Fig. 8.15. The cause of this decline may be (1) turbulence at increased rates of flow, (2) decrease in the permeability to oil due to presence of free gas caused by the drop in pressure at the wellbore, (3) increase in oil viscosity with pressure drop below bubble point, and/or (4) reduction in permeability due to formation compressibility.

In depletion reservoirs, the productivity indices of the wells decline as depletion proceeds, owing to the increase in oil viscosity as gas is released from solution and to the decrease in the permeability of the rock to oil as the oil saturation decreases. Since each of these factors may change from a few to severalfold during depletion, the PI may decline to a small fraction of the initial value. Also, as the permeability to oil decreases, there is a corresponding increase in the permeability to gas, which results in rising gas-oil ratios. The maximum rate at which a well can produce depends on the productivity index at prevailing reservoir conditions and on the available pressure drawdown. If the producing bottom-hole pressure is maintained near zero by keeping the well “pumped off,” then the available drawdown is the prevailing reservoir pressure and the maximum rate is  .

.

In wells producing water, the PI, which is based on dry oil production, declines as the watercut increases because of the decrease in oil permeability, even though there is no substantial drop in reservoir pressure. In the study of these “water wells,” it is sometimes useful to place the PI on the basis of total flow, including both oil and water, where in some cases the watercut may rise to 99% or more.

The injectivity index is used with saltwater disposal wells and with injection wells for secondary recovery or pressure maintenance. It is the ratio of the injection rate in STB per day to the excess pressure above reservoir pressure that causes that injection rate, or

With both productivity index and injectivity index, the pressures referred to are sandface pressures, so that frictional pressure drops in the tubing or casing are not included. In the case of injecting or producing at high rates, these pressure losses may be appreciable.

In comparing one well with another in a given field, particularly when there is a variation in net productive thickness but when the other factors affecting the productivity index are essentially the same, the specific productivity index Js is sometimes used, which is the productivity index divided by the net feet of pay, or

In evaluating well performance, the standard usually referred to is the productivity index of an open hole that completely penetrates a circular formation normal to the strata and in which no alteration in permeability has occurred in the vicinity of the wellbore. Substituting Eq. (8.47) into Eq. (8.49), we get

The productivity ratio (PR) then is the ratio of the PI of a well in any condition to the PI of this standard well:

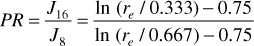

Thus, the productivity ratio may be less than one, greater than one, or equal to one. Although the productivity index of the standard well is generally unknown, the relative effect of certain changes in the well system may be evaluated from theoretical considerations, laboratory models, or well tests. For example, the theoretical productivity ratio of a well reamed from an 8-in. borehole diameter to 16 in. is derived by Eq. (8.52):

Assuming re = 660 ft,

Thus, doubling the borehole diameter should increase the PI approximately 11%. An inspection of Eq. (8.50) indicates that the PI can be improved by increasing the average permeability k, decreasing the viscosity μ, or increasing the wellbore radius rw. Another name for the productivity ratio is the flow efficiency (FE).

Earlougher and others have discussed the application of the principle of superposition to fluid flow in reservoirs.3,12,13,14 This principle allows the use of the constant rate, single-well equations that have been developed earlier in this chapter and applies them to a variety of other cases. To illustrate the application, the solution to Eq. (8.38), which is a linear, second-order differential equation, is examined. The principle of superposition can be stated as follows: The addition of solutions to a linear differential equation results in a new solution to the original differential equation. For example, consider the reservoir system depicted in Fig. 8.16. In the example shown in Fig. 8.16, wells 1 and 2 are opened up to their respective flow rates, q1 and q2, and the pressure drop that occurs in the observation well is monitored. The principle of superposition states that the total pressure drop will be the sum of the pressure drop caused by the flow from well 1 and the pressure drop caused by the flow from well 2:

Δpt = Δp1 + Δp2

Each of the individual Δp terms is given by Eq. (8.39), or

To apply the method of superposition, pressure drops or changes are added. It is not correct simply to add or subtract individual pressure terms. It is obvious that if there are more than two flowing wells in the reservoir system, the procedure is the same, and the total pressure drop is given by the following:

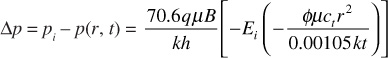

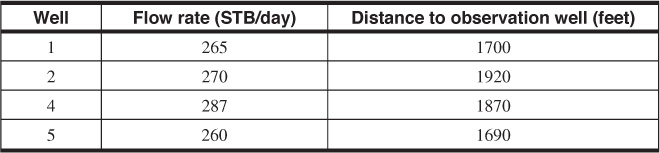

where N equals the number of flowing wells in the system. Example 8.2 illustrates the calculations involved when more than one well affects the pressure of a point in a reservoir.

Example 8.2 Calculating Total Pressure Drop

For the well layout shown in Fig. 8.17, calculate the total pressure drop as measured in the observation well (well 3) caused by the four flowing wells (wells 1, 2, 4, and 5) after 10 days. The wells were shut in for a long time before opening them to flow.

Figure 8.17 Well layout for Problem 8.2.

Given

The following data apply to the reservoir system:

μ = 0.40 cp

Bo = 1.50 bbl/STB

k = 47 md

h = 50 ft

ct = 15 × 10–6 psi–1

Solution

The individual pressure drops can be calculated with Eq. (8.39), and the total pressure drop is given by Eq. (8.54). For well 1,

From Fig. 8.12,

– Ei(– 0.164) = 1.39

Δp1 = 4.78(1.39) = 6.6 psi

Similarly, for wells 2, 4, and 5,

Δp2 = 4.87[– Ei(– 0.209)] = 5.7 psi

Δp4 = 5.14[– Ei(– 0.198)] = 6.4 psi

Δp5 = 4.69[– Ei(– 0.162)] = 6.6 psi

Using Eq. (8.54) to find the total pressure drop at the observation well (well 3), the individual pressure drops are added together to give the total:

Δpt = Δp1 + Δp2 + Δp4 + Δp5

or

Δpt = 6.6 + 5.7 + 6.4 + 6.6 = 25.3 psi

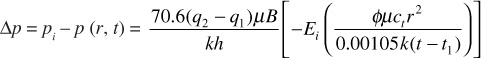

The superposition principle can also be applied in the time dimension, as is illustrated in Fig. 8.18. In this case, one well (which means the position where the pressure disturbances occur remains constant) has been produced at two flow rates. The change in the flow rate from q1 to q2 occurred at time t1. Figure 8.18 shows that the total pressure drop is given by the sum of the pressure drop caused by the flow rate, q1, and the pressure drop caused by the change in flow rate, q2 – q1. This new flow rate, q2 – q1, has flowed for time t – t1.

The pressure drop for this flow rate, q2 – q1, is given by

As in the case of the multiwell system just described, superposition can also be applied to multirate systems as well as the two rate examples depicted in Fig. 8.18.

Although Eq. (8.39) applies to infinite reservoirs, it may be used in conjunction with the superposition principle to simulate boundaries of closed or partially closed reservoirs. The effect of boundaries is always to cause greater pressure drops than those calculated for the infinite reservoirs. The method of images is useful in handling the effect of boundaries. For example, the pressure drop at point x (Fig. 8.19), owing to production in a well located a distance d from a sealing fault, will be the sum of the effects of the producing well and an image well that is superimposed at a distance d behind the fault. In this case, the total pressure drop is given by Eq. (8.54), where the individual pressure drops are again given by Eq. (8.39), or for the case shown in Fig. 8.19,

Pressure transient testing is an important diagnostic tool that can provide valuable information for the reservoir engineer. A transient test is initiated by creating a disturbance at a wellbore (i.e., a change in the flow rate) and then monitoring the pressure as a function of time. An efficiently conducted test that yields good data can provide information such as average permeability, drainage volume, wellbore damage or stimulation, and reservoir pressure.

A pressure transient test does not always yield a unique solution. There are often anomalies associated with the reservoir system that yield pressure data that could lead to multiple conclusions. In these cases, the strength of transient testing is realized only when the procedure is used in conjunction with other diagnostic tools or other information.

In the next two subsections, the two most popular tests (i.e., the drawdown and buildup tests) are introduced. However, notice that the material is intended to be only an introduction. The reader must be aware of many other considerations in order to conduct a proper transient test. The reader is referred to some excellent books in this area by Earlougher, Matthews and Russell, and Lee.3,10,15

The drawdown test consists of flowing a well at a constant rate following a shut-in period. The shut-in period should be sufficiently long for the reservoir pressure to have stabilized. The basis for the drawdown test is found in Eq. (8.40),

which predicts the pressure at any radius, r, as a function of time for a given reservoir flow system during the transient period. If r = rw, then p (r, t) will be the pressure at the wellbore. For a given reservoir system, pi, q, μ, B, k, h, φ, ct, and rw are constant, and Eq. (8.40) can be written as

where

Equation (8.55) suggests that a plot of pwf versus t on semilog graph paper would yield a straight line with slope m through the early time data that correspond with the transient time period. This is providing that the assumptions inherent in the derivation of Eq. (8.40) are met. These assumptions are as follows:

1. Laminar, horizontal flow in a homogeneous reservoir

2. Reservoir and fluid properties, k, φ, h, ct, μ, and B, independent of pressure

3. Single-phase liquid flow in the transient time region

4. Negligible pressure gradients

The expression for the slope, Eq. (8.56), can be rearranged to solve for the capacity, kh, of the drainage area of the flowing well. If the thickness is known, then the average permeability can be obtained by Eq. (8.57):

If the drawdown test is conducted long enough for the pressure transients to reach the pseudosteady-state period, then Eq. (8.55) no longer applies.

In the pseudosteady-state regime, Eq. (8.44) is used to describe the pressure behavior:

Again, grouping together the terms that are constant for a given reservoir system, Eq. (8.44) becomes

where

Now a plot of pressure versus time on regular Cartesian graph paper yields a straight line with slope equal to m′ through the late time data that correspond to the pseudosteady-state period. If Eq. (8.59) is rearranged, an expression for the drainage volume of the test well can be obtained:

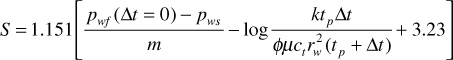

The drawdown test can also yield information about damage that may have occurred around the wellbore during the initial drilling or during subsequent production. An equation will now be developed that allows the calculation of a damage factor, using information from the transient flow region.

A damage zone yields an additional pressure drop because of the reduced permeability in that zone. Van Everdingen and Hurst developed an expression for this pressure drop and defined a dimensionless damage factor, S, called the skin factor:16,17

or

From Eq. (8.62), a positive value of S causes a positive pressure drop and therefore represents a damage situation. A negative value of S causes a negative pressure drop that represents a stimulated condition like a fracture. Notice that these pressure drops caused by the skin factor are compared to the pressure drop that would normally occur through this affected zone as predicted by Eq. (8.40). Combining Eqs. (8.40) and (8.62), the following expression is obtained for the pressure at the wellbore:

This equation can be rearranged and solved for the skin factor, S:

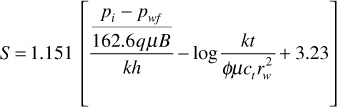

The value of pwf must be obtained from the straight line in the transient flow region. Usually a time corresponding to 1 hr is used, and the corresponding pressure is given by the designation p1hr. Substituting m into this equation and recognizing that the denominator of the first term within the brackets is actually –m,

Equation (8.64) can be used to calculate a value for S from the slope of the transient flow region and the value of p1hr also taken from the straight line in the transient period.

A drawdown test is often conducted during the initial production from a well, since the reservoir has obviously been stabilized at the initial pressure, pi. The difficult aspect of the test is maintaining a constant flow rate, q. If the flow rate is not kept constant during the length of the test, then the pressure behavior will reflect this varying flow rate and the correct straight line regions on the semilog and regular Cartesian plots may not be identified. Other factors such as wellbore storage (shut-in well) or unloading (flowing well) can interfere with the analysis. Wellbore storage and unloading are phenomena that occur in every well to a certain degree and cause anomalies in the pressure behavior. Wellbore storage is caused by fluid flowing into the wellbore after a well has been shut in on the surface and by the pressure in the wellbore changing as the height of the fluid in the wellbore changes. Wellbore unloading in a flowing well will lead to more production at the surface than what actually occurs down hole. The effects of wellbore storage and unloading can be so dominating that they completely mask the transient time data. If this happens and if the engineer does not know how to analyze for these effects, the pressure data may be misinterpreted and errors in calculated values of permeability, skin, and the like may occur. Wellbore storage and unloading effects are discussed in detail by Earlougher.3 These effects should always be taken into consideration when evaluating pressure transient data.

The following example problem illustrates the analysis of drawdown test data.

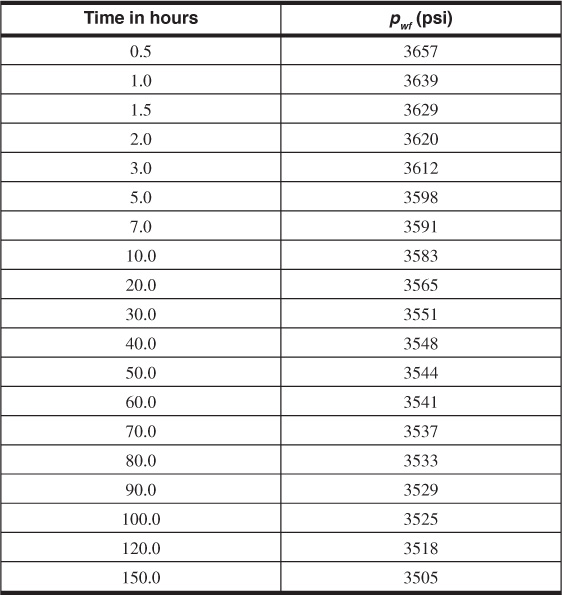

Example 8.3 Calculating Average Permeability, Skin Factor, and Drainage Area

A drawdown test was conducted on a new oil well in a large reservoir. At the time of the test, the well was the only well that had been developed in the reservoir. Analysis of the data indicates that wellbore storage does not affect the pressure measurements. Use the data to calculate the average permeability of the area around the well, the skin factor, and the drainage area of the well.

pi = 4000 psia

h = 20 ft

q = 500 STB/day

ct = 30 × 10–6 psia–1

μo = 1.5 cp

φ = 25%

Bo = 1.2 bbl/STB

rw = 0.333 ft

Solution

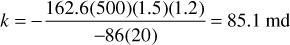

Figure 8.20 contains a semilog plot of the pressure data. The slope of the early time data, which are in the transient time region, is –86 psi/cycle, and the value of P1hr is read from the pressure value on the line at 1 hr as 3526 psia. Equation (8.57) can now be used to calculate the permeability:

Figure 8.20 Plot of pressure versus log time for the data of Example 8.3.

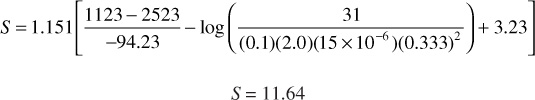

The skin factor is found from Eq. (8.64):

This positive value for the skin factor suggests the well is slightly damaged.

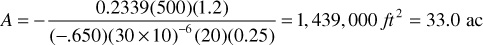

From the slope of a plot of P versus time on regular Cartesian graph paper, shown in Fig. 8.21, and using Eq. (8.60), an estimate for the drainage area of the well can be obtained. From the semilog plot of pressure versus time, the first six data points fell on the straight line region indicating they were in the transient time period. Therefore, the last two to three points of the data are in the pseudosteady-state period and can be used to calculate the drainage area. The slope of a line drawn through the last three points is –0.650. Therefore,

Figure 8.21 Plot of pressure versus time for the data of Example 8.3.

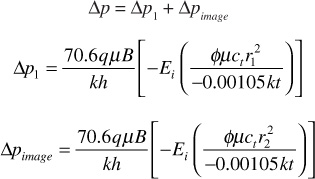

The buildup test is the most popular transient test used in the industry. It is conducted by shutting in a producing well that has obtained a stabilized pressure in the pseudosteady-state time region by flowing the well at a constant rate for a sufficiently long period. The pressure is then monitored during the length of the shut-in period. The primary reason for the popularity of the buildup test is the fact that it is easy to maintain the flow rate constant at zero during the length of the test. The main disadvantage of the buildup test over that of the drawdown test is that there is no production during the test and therefore no subsequent income.

A pressure buildup test is simulated mathematically by using the principle of superposition. Before the shut-in period, a well is flowed at a constant flow rate, q. At the time corresponding to the point of shut-in, tp, a second well, superimposed over the location of the first well, is opened to flow at a rate equal to –q, while the first well is allowed to continue to flow at rate q. The time that the second well is flowed is given the symbol of Δt. When the effects of the two wells are added, the result is that a well has been allowed to flow at rate q for time tp and then shut in for time Δt. This simulates the actual test procedure, which is shown schematically in Fig. 8.22. The time corresponding to the point of shut-in, tp, can be estimated from the following equation:

where Np = cumulative production that has occurred during the time before shut-in that the well was flowed at the constant flow rate q.

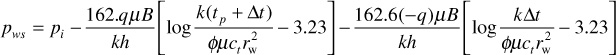

Equations (8.40) and (8.54) can be used to describe the pressure behavior of the shut-in well:

Expanding this equation and canceling terms,

where

pws = bottom-hole shut-in pressure

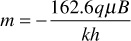

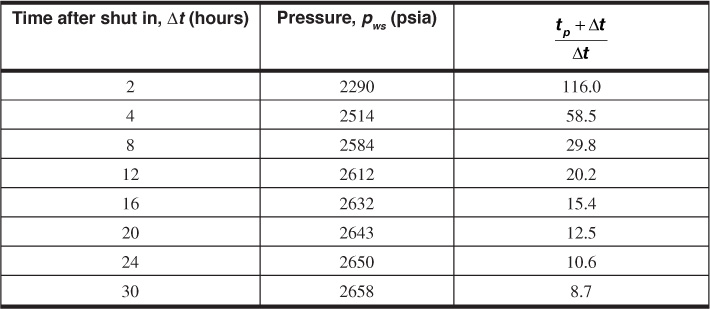

Equation (8.66) is used to calculate the shut-in pressure as a function of the shut-in time and suggests that a plot of this pressure versus the ratio of (tp + Δt)/Δt on semilog graph paper will yield a straight line. This plot is referred to as a Horner plot, after the man who introduced it into the petroleum literature.18 Figure 8.23 is an example of a Horner Plot. The points on the left of the plot constitute the linear portion, while the two points to the right, representing the early time data, are severely affected by wellbore storage effects and should be disregarded. The slope of the Horner plot is equal to m, or

Figure 8.23 Plot of pressure versus time ratio for Example 8.4.

This equation can be rearranged to solve for the permeability:

The skin factor equation for buildup is found by combining Eq. (8.64), written for t = tp(Δt = 0), and Eq. (8.66):

The shut-in pressure, pws, can be taken at any Δt on the straight line of the transient flow period. For convenience, Δt is set equal to 1 hr, and pws is taken from the straight line at that point. The value for p1hr must be on the straight line and might not be a data point. At a time of Δt = 1 hr, tp is much larger than Δt for most tests, and tp + Δt ≈ tp. With these considerations, the skin factor equation becomes

This section is concluded with an example problem illustrating the analysis of a buildup test. Notice again that there is much more to this overall area of pressure transient testing. Pressure transient testing is a very useful quantitative tool for the reservoir engineer if used correctly. The intent of this section was simply to introduce these important concepts. The reader should pursue the indicated references if more thorough coverage of the material is needed.

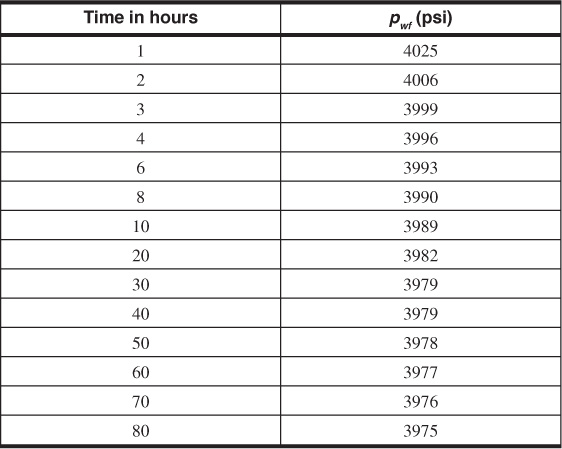

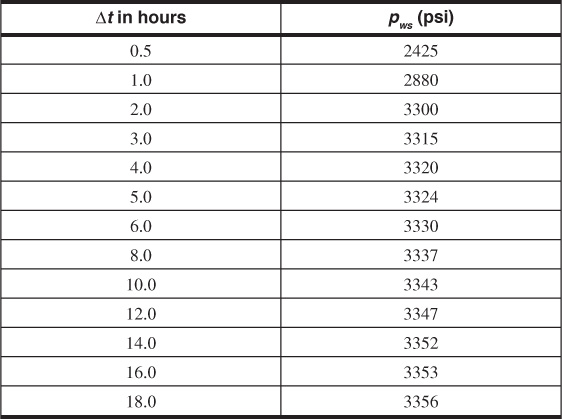

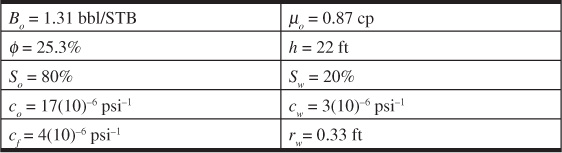

Example 8.4 Calculating Permeability and Skin from a Pressure Buildup Test

Given

Flow rate before shut in period = 280 STB/day

Np during constant rate period before shut in = 2682 STB

pwf at the time of shut-in = 1123 psia

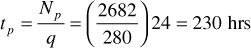

From the foregoing data and Eq. (8.65), tp can be calculated:

Other given data are

Bo= 1.31 bbl/STB

μo = 2.0 cp

h = 40 ft

ct = 15 × 10–6 psi–1

φ = 10%

rw = 0.333 ft

Solution

The slope of the straight-line region (notice the difficulty in identifying the straight-line region) of the Horner plot in Fig. 8.23 is –94.23 psi/cycle. From Eq. (8.67),

Again from the Horner plot, p1hr is 2523 psia and, from Eq. (8.68),

The extrapolation of the straight line to the Horner time equal to 1 provides the extrapolated pressure, p*. For a new well, p* provides an estimate for the initial reservoir pressure, pi.

The time ratio (tp + Δt)/Δt decreases as Δt increases. Therefore, the early time data are on the right and the late time data on the left of Fig. 8.23. Because most of the data points are influenced by wellbore storage, it is difficult to identify the correct straight line of the transient time region. For this example problem, the last three data points were used to represent the transient time region. This difficulty in identifying the proper straight-line region points out the importance of a thorough understanding of wellbore storage and other anomalies that could affect the pressure transient data. Modern pressure transient interpretation methods in Lee et al. (2004) offer more effective ways to do this analysis that are beyond the scope of this chapter.

8.1 Two wells are located 2500 ft apart. The static well pressure at the top of perforations (9332 ft subsea) in well A is 4365 psia and at the top of perforations (9672 ft subsea) in well B is 4372 psia. The reservoir fluid gradient is 0.25 psi/ft, reservoir permeability is 245 md, and reservoir fluid viscosity is 0.63 cp.

(a) Correct the two static pressures to a datum level of 9100 ft subsea.

(b) In what direction is the fluid flowing between the wells?

(c) What is the average effective pressure gradient between the wells?

(d) What is the fluid velocity?

(e) Is this the total velocity or only the component of the velocity in the direction between the two wells?

(f) Show that the same fluid velocity is obtained using Eq. (8.1).

8.2 A sand body is 1500 ft long, 300 ft wide, and 12 ft thick. It has a uniform permeability of 345 md to oil at 17% connate water saturation. The porosity is 32%. The oil has a reservoir viscosity of 3.2 cp and Bo of 1.25 bbl/STB at the bubble point.

(a) If flow takes place above the bubble-point pressure, which pressure drop will cause 100 reservoir bbl/day to flow through the sand body, assuming the fluid behaves essentially as an incompressible fluid? Which pressure drop will do so for 200 reservoir bbl/day?

(b) What is the apparent velocity of the oil in feet per day at the 100-bbl/day flow rate?

(c) What is the actual average velocity?

(d) What time will be required for complete displacement of the oil from the sand?

(e) What pressure gradient exists in the sand?

(f) What will be the effect of raising both the upstream and downstream pressures by, say, 1000 psi?

(g) Considering the oil as a fluid with a very high compressibility of 65(10)–6 psi–1, how much greater is the flow rate at the downstream end than the upstream end at 100 bbl/day?