4

THE ORGANIZATIONAL TRANSFORMATION OF CIVIL SOCIETY

Patricia Bromley1

DRAMATIC SHIFTS IN RECENT DECADES drive home the need to reevaluate our understanding of the nonprofit sector and why it exists. The sector has expanded massively worldwide in countries that differ in their most elemental features, and within countries nonprofits are increasingly formal and complex organizations that can look very much like their counterparts in business and government sectors. But these developments are not inevitable. Nor are they simply a consequence of functional needs in society to, for example, deliver services more efficiently and effectively.

Starting in the early 1960s, economic explanations for the existence of nonprofit organizations gained momentum and developed into the dominant account of the sector (Hansmann 1980; Salamon 1987). Nonprofits, according to this account, emerged as a result of gaps left by market and government failures. Implicitly or explicitly, these failure-based explanations underpin a great deal of research, practice, and policy related to nonprofits. Yet there are several well-documented reasons to question whether those explanations fully account for the existence of the nonprofit sector. Such arguments fall short of explaining the massive and recent explosion of formal nonprofit organizations across vastly different political, economic, and historical contexts. Moreover, the now-commonplace observation of extensive blurring and cooperation between the business, nonprofit, and government sectors is hard to account for by theories predicting sharp distinctions between actors from those sectors (Ghatak, Chapter 13, “Economic Theories of the Social Sector”).

This chapter draws on sociological theories of formal organization to develop an alternative, cultural account of why the nonprofit sector has evolved into its contemporary form. Specifically, it argues that certain features of the sector today—especially its worldwide expansion and its increasingly formal nature—partly reflect the rise and globalization of liberal and neoliberal cultural ideologies. Liberal creeds valorize individuals as a cultural matter on two relevant fronts; first, they celebrate rational, scientific-like action (beyond established evidentiary bases), and second, they celebrate the sacredness of individual human rights and capabilities (despite persistent inequalities). The structures of contemporary formal organization are constituted by these intertwined principles of rational, sciencelike action and human rights. One implication of this argument is that, as a social-structural manifestation of these cultural ideologies, formal nonprofit organization as we know it is likely to weaken if the current liberal world order erodes.

The nonprofit sector has grown massively over the past several decades. This expansion, moreover, is astoundingly widespread: nonprofit organizations have grown in number in countries with very different contexts, they have grown at both domestic and international levels, and they have grown internally by becoming larger and more complex. In the United States the total number of nonprofits exploded from fewer than 13,000 in 1940 to more than 1.5 million by the end of the century (Soskis, Chapter 2, “History of Associational Life and the Nonprofit Sector in the United States”). Prior to the 1930s very few new nonprofits were created per year, but by the late 1960s around 20,000 new organizations were founded per year, and by the 1990s more than 50,000 new nonprofits per year filed for tax-exempt status (Jones 2006). Financially, American nonprofits also show healthy growth. For example, between 2002 and 2012, both revenues and assets grew faster than GDP: after adjusting for inflation, revenues grew 36.2 percent and assets grew 21.5 percent, compared with 19.1 percent growth for GDP (McKeever and Pettijohn 2014). New nonprofits have proliferated outside the United States as well, and this growth has been particularly rapid in countries that lie outside the community of established liberal democracies (Schofer and Longhofer 2011; Schofer and Longhofer, Chapter 27, “The Global Rise of Nongovernmental Organizations”; Dupuy and Prakash, Chapter 28, “Global Backlash Against Foreign Funding to Domestic Nongovernmental Organizations”). In addition, international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) have skyrocketed in number over time: from 1909 to 2009, INGO growth equates to a shift from roughly 0.1 organization per million people to 8 organizations per million people (Union of International Associations 2018).

A critical feature of these indicators of nonprofit expansion is that they document instances of expanding formal organization. This growth is not simply an artifact of more or better counting; it reflects a fundamental transformation that goes beyond the nonprofit sector. We now live in an “organizational society,” as observed by foundational figures in the field of organization theory (Presthus 1962; Coleman 1982; Drucker 1992; Perrow 2009). Organizations are the dominant social structure of our time, reaching into virtually all realms of life. The expansion of registration processes and directories of nonprofits is a central part of the transformation of civil society into a sector marked by increasingly formal organization. These registrations, countings, and accountings of nonprofit activities are substantive indicators of that transformation, rather than a data artifact.

Thus, a striking and central characteristic of the “global associational revolution” (Salamon 1993) is that much of it takes the form of formal organization. An analytical framework that focuses on counting formal organizations does not tell us whether humans are becoming more altruistic, or whether societies are becoming more equal or just. It leaves out many forms of prosocial activity: for example in collectives, such as families, tribes, and diasporas, as well as in looser networks, such as informal social movements and associations. After all, there are multiple ways of conceptualizing and creating civil society, and the formal organizational character of contemporary civil society represents only one such mode. We do not know if there is more “nonprofit” or prosocial activity in the world as a substantive focus, but we do know there is an expansion of “organization” as a structure. This leads to a core question: What does it mean to be a nonprofit “organization”?

This chapter analyzes the organizational transformation of civil society in four parts. First, it sketches the likely sources of this shift. It posits that cultural changes tied to the rise and globalization of Western liberal and neoliberal ideologies generate organizational expansion and formalization of associational life. According to this argument, the liberal valorization of individuals reshapes older forms of social activity, such as loose associations or tight collectivities, making them look more like what we recognize as contemporary formal organizations. Second, it comes to a more complete conceptualization of the unique features of contemporary formal “organization,” defining the ideal type of formal organization as an entity constructed to encompass both collective purposes and scientific rationality. Third, it presents a discussion of research directions that emerge from this argument. And fourth, it reflects on potential consequences of the rise of formal organization as a central feature of civil society.

The chapter makes several contributions to research on the nonprofit sector. To begin, it provides a cultural argument for the rise of formal nonprofit organization that explains why this form has emerged and expanded beyond its known functional utility. Prior research on the nonprofit sector has largely focused on understanding the “nonprofit” side of this work (e.g., Frumkin 2002), while other studies of organizational expansion have largely focused on firms and underemphasized the prosocial and nonprofit dimensions of this growth (e.g., Coleman 1982). Next, in presenting this cultural argument, the chapter goes beyond market-based explanations for the blurring between business, nonprofit, and government sectors. A cultural view emphasizes that entities in all sectors are increasingly structured as instances of formal organization; business is becoming nonprofit-like as much as nonprofits are becoming businesslike. Finally, the chapter explores a key implication of this argument: if formal nonprofit organization is associated with contemporary liberal culture, then it is likely to decline if and when liberalism erodes as the core organizing principle of national and world society.

Cultural Bases of Formal Organization2

The expansion of formal organization is linked to great cultural shifts that assert the ascendancy of the individual. Conceptions of the hyperempowered individual arise mainly from liberal Western philosophies, although they have spread globally beyond these roots. Two dimensions of expanding individualism are most relevant here. A first core dimension is the reconstruction of all human beings as inherently possessing a sacred status (Elliott 2007). This “cult of the individual” asserts a growing array of rights for more types of people and, related, valorizes human capabilities for rational action (Durkheim 1951, 1961). A second, related dimension is the diffusion of scientific and social scientific thought and method far beyond their traditional areas of focus, constructing social action as more universal, standardized, and orderly.

Following sociological definitions, the term scientific and its permutations extend beyond their application to particular disciplines (e.g., chemistry, biology, or medicine) or an actual knowledge base. These terms refer broadly to cultural principles that give authority to systematically developed knowledge and to university-trained experts, rather than to alternative bases of authority such as charisma, tradition, or tacit forms of knowledge (Drori, Meyer, and Ramirez 2003). Moreover, these terms involve a belief in scientific and quasi-scientific methods as a highly legitimate source of authority more than they do an account of the true state of knowledge. In fact, the legitimacy of science as a source of authority, and belief in science as a principle, promote its expansion far beyond reasonable uses. The term human rights refers to a multifaceted expansion in the socially defined rights, obligations, interests, and capabilities of all individuals (Meyer and Jepperson 2000; Meyer 2010). Both dimensions are considered part of a cultural belief system because we celebrate scientific action beyond objectively knowable truths, assert human rationality beyond known capability, and valorize the sacredness of individual human rights beyond the realities of persistent global and local inequalities.

These principles provide a new basis for social order and action in which individuals, envisioned as possessing great rational capabilities and expansive human rights, are an increasingly central locus of both change and stability. There are masses of reforms in existing structures, largely in ways that are imagined to reflect and expand individual choice and capacity (e.g., decentralization, privatization, deregulation). But societies embracing these principles are not adequately characterized by imageries of individuals pursuing self-interests in anarchy. The ideals of scientific action and human rights come with strong self-disciplining and self-regulating social controls that provide order and stability (Miller and Rose 1990, 2008). Legitimate action needs to reflect the principles of science and rights (e.g., participatory structures, efficiency and accountability practices like outcomes measurement and evaluation), as do perceptions of self-interest. To use other terminology, governance rather than government becomes a key source of order and control (Rhodes 1996; Mörth 2004; Osborne 2006, 2010; see also Marwell and Brown, Chapter 9, “Toward a Governance Framework for Government–Nonprofit Relations”). In the following sections, I provide a rough overview of the historical expansion and globalization of these trends before spelling out how they generate formal organization.

Historical Emergence

The cultural shifts related to the global expansion of science and human rights are widely reported (see Price 1961 or Drori et al. 2003 for a general overview on science; see Elliott 2007, Stacy 2009, or Lauren 2011 for an overview on human rights). In many accounts, these shifts are tied to broad political changes related to the evolution of a feudal religious polity with medieval governance structures into the secular, administrative, and legal structures of modern nation-states (Tilly 1990). Enlightenment-era philosophy also helped consolidate and expand secular individualism; realms like education, art, and music became matters of interest to the general public, rather than pastimes for an elite few. To be sure, fully elaborating the exact causes of the massive and complex cultural changes unfolding over hundreds of years are beyond the scope of this paper. But whatever the causes, the clear consequence of these trends was that the scope, scale, and nature of social structure changed dramatically to reflect liberal and neoliberal cultural principles.

Expansion of Science: In the early modern period, an expansion of scientific thinking produced a movement toward administrative reform (M. Weber (1922) 1978). Feudal religious polities with medieval governance structures evolved into the secular, administrative, and legal structures of modern nation-states (Tilly 1990). Early bureaucracies, which included governments, churches, armies, and early corporations, had a rationalized, quasi-scientific form. But they were centralized structures intended to effectively and efficiently carry out the goals of a sovereign or owner; lower levels of these hierarchical structures had little autonomy or empowerment.

Then, in the first part of the twentieth century, an expansion of the social sciences led to the development of scientific approaches to managing businesses (as with Fayol 1949 or Taylor 1914) and generated more systematic approaches to philanthropic giving. Scholars often describe a shift from charity to philanthropy, with the former focusing on religious obligations to alleviate individual suffering and the latter focusing on developing systematic, rationalized, and putatively effective resolutions to social problems (Robbins 2006; Sealander 2003).

In the latter part of the twentieth century, the doctrines and myths of science have become more powerful, and their authority now reaches far into social life (Drori et al. 2003). Today, nearly every domain of natural and social life is analyzable and analyzed. For example, shared scientific principles about the common environment transcend criticisms of cultural relativism and provide a universalistic basis for rules applicable everywhere (Foucault (1978) 1997). In the same way, the expansion of the psychological sciences generates expanded conceptions of the needs of humans, so that any dimension of human development or way of thinking can become a widespread concern. For example, scientific analyses of childhood and its problems grow as children become reconceived as priceless (Zelizer 1994) and provide bases for social organization that now extend to a global level. New organizations arise, and older ones take on new responsibilities, for dealing with various dimensions of childhood—health, education, consumption behavior, protection from abuse by families and firms, and so on.

The extraordinary expansion of scientific authority means that even movements that resist certain kinds of social change—in areas like gay rights or climate change—now sometimes use the language and authority of science, rather than directly invoking alternative cosmologies. And, as a cultural principle, scientific and quasi-scientific endeavors spread into domains that far outpace their actual utility as generalizable Truth, allowing for a great deal of contestation (e.g., about what we know in the “decision-making sciences” or “learning sciences”). Nonprofits and foundations, for instance, are advised to (and sometimes do) build rationalized “theories of change” or “logic models” spelling out their best guess for how to achieve social change using quantified measures and metric (Brest, Chapter 16, “The Outcomes Movement in Philanthropy and the Nonprofit Sector”; Horvath and Powell, Chapter 3, “Seeing Like a Philanthropist”).

Expansion of Individual Rights and Capacities: In the eighteenth century, events that culminated in the French and American Revolutions played a central role in the development of individual rights. As new conceptions of justice and equality expanded, they promoted visions of democracy and undermined notions such as the divine right of kings (Bendix 1980). Consequently, highly centralized social structures, like the classic bureaucratic state, lost their charisma. In tandem, ideas of civil society as a distinct social sphere began to flourish. But early voluntary associations were relatively informal expressions of community, unlike the highly structured nonprofit organizations common today.

The new liberal ontology generated a focus on the human individual as the locus of both rights and action. As one indicator, the twentieth century witnessed an explosion of human rights treaties, organizations, and doctrines that spread liberal principles worldwide, and nation-states generally accepted this regime as legitimate at a cultural level (though not always at a practical level) (Elliott 2007, Stacy 2009, Lauren 2011). More rights were constructed and more types of people (e.g., gays and lesbians, disabled people, children, ethnic minorities, women) were almost always seen as individuals rather than corporate groups. And human rights changed focus from entitlements to protection, political standing, and social welfare (T. Marshall 1964): importantly for the expansion of the nonprofit sector, social and cultural matters came to be included. But further, the new human individual was seen as an empowered actor—able and entitled to pursue rights and interests on a global scale (Elliott 2007)—and inherent properties of individual rights and capabilities were seen as universalistic; human rights transcended local polities and their variations. So individuals are now increasingly entitled to choose roles and identities (Frank and Meyer 2002; Jiménez 2010)—but also obligated to respect the rights and capabilities of others.

Globalization

A dramatic cultural shift has thus provided a cosmological frame that imagines social order on a global scale emerging from universalistic principles—a frame that Foucault called “governmentality” ([1978] 1997). This cultural transformation unfolds over hundreds of years, but the end of World War II and the rise of neoliberalism in the 1990s bring notable intensifications of the worldwide expansion of an organizational revolution (e.g., Drori, Meyer, and Hwang 2006; Drori and Meyer 2006). Especially in the wake of World War II, the nation-state lost legitimacy, stigmatized by a half century of horrific evils. In the Western world, corporatist and statist ideas, as well as affiliated communal structures (e.g., traditional professions, the family as a corporate group, and related notions of race and religion as intrinsic properties of nations), lost standing. A positive legal system was not available in the decentralized world system in the wake of World War II, but a social order that would go beyond traditional state-centered mechanisms was widely seen as necessary. The solution, emphasized by the dominant, radically liberal United States, was the construction of forms rooted in the assumptions of rational choice and rights that characterize liberalism (as in de Tocqueville (1836) 2003; see Ruggie 1982). In other words, without the hard laws of a supranational world state, social controls rooted in the assertion of laws of science and human rights have been widely employed.

Throughout the Cold War, the spread of a liberal global order faced resistance from the competing vision of socialism. Following the collapse of the USSR, however, there was no real alternative to liberalism at the global level. Left unchecked, “embedded liberalism” (Ruggie 1982) evolved into its more extreme neoliberal form, and globalization in all forms—social, political, cultural, and economic—became more pronounced. In this context we see the emergence and rapid expansion across all sectors of formal organization. In this neoliberal world order, organizations are not only structured functionally to accomplish goals but also structured to do so as a virtuous citizen of a supranational world that conforms to the principles of science and human rights (Matten and Crane 2005).

Constituting Formal Organization

Overall, the perceived rights, authority, and capabilities of the individual human being grow stronger, and the parts of other social structures—such as nation-states, families, and communities—that are rooted in more communal principles become relatively weaker (Hall and Jacques 1989). Together, the abstract and universalistic principles of scientific rationality and human rights constitute the cultural foundation for the emergence and growth of the social structure that today we call “organization.” The rise of ideologies of human rights and scientific capabilities generates the expansion of formal organization in two ways.

First, assertions of human rights and scientific rationality considerably expanded the range of domains in which empowered human initiative seems reasonable (Toulmin 1992). These principles provide a basis for widespread purposive action in a growing array of substantive domains. Underpinned by assertions of rights, purposeful individual activity extends into new domains, such as abolitionism and children’s rights. And underpinned by revelations of science, organized activity expands into areas such as environmentalism or animal welfare. Often, these principles—which both stem from expanding individualism—are deeply intertwined. As one example, Oxfam’s work began with a predominantly technical vision of international development but increasingly takes on a “rights-based” orientation (Offenheiser and Holcombe 2003). As other examples, environmentalism, educational expansion, and health care are often justified on both scientific and rights-based grounds.

Second, cultural principles of human rights and science provide cultural templates for how activity should be structured. Under human rights principles, decisions and activities should be participatory and respectful of individual rights, and rational, responsible, and organized human action is seen as both possible and necessary. And under scientific principles, means and ends are systematically specified, measured, and monitored, and experts and professionals of all sorts proliferate and are seen as providing legitimate knowledge.

Such long-term changes greatly intensified after World War II and operate in the whole period since, but especially powerfully in the neoliberal era. This generated both increased numbers of organizations in previously unorganized arenas and increased internal elaboration of existing structures as these adapted to expanding external obligations. For example, as cultural pressures to respect a range of rights increase, it now becomes sensible for both Nike (in the business sector) and the Red Cross (in the nonprofit sector) to pursue diversity on their boards, policies for work-life balance, and formal efforts to protect children (by preventing them from making soccer balls or donating blood). Under these new cultural principles, traditional social structures—government agencies, firms, charities, hospitals, and universities—are reconstituted.

As social structures are transformed by these principles of human rights and scientific rationality, they come to look more like what we now recognize as proper, contemporary formal organizations. For instance, an old-fashioned charity responded to some social ill, but a modern nonprofit organization should do so in a way that is accountable, systematic, and effective; a Fordist firm efficiently maximized profits, but a modern corporation should do so while also displaying elements of social responsibility; a traditional government bureaucracy provided public services, but a modern public agency should do so while involving many stakeholders. In all these examples, the latter case illustrates the coming together of rights and scientific rationality through a process that transforms (albeit often partially) an older structure into a contemporary formal organization. These cultural principles are universalistic, envisioned as natural laws that cut across social sectors and extend around the world—although in practice they are not universally shared.

As illustrations, consider the widely reported transformations of two structures that emerged in early modern Western history. Bureaucracy, the first example, was conceived of as a structure serving a sovereign; even in theory individuals throughout its structure were envisioned as passively filling roles rather than empowered actors. Thus, bureaucracy has the scientific rationality of organization but lacks widespread individual empowerment. The transformation (at least partially) of bureaucracy is well recognized (Musolf and Seidman 1980; Osborne 2006, 2010). In both scholarly and public discourses we commonly recognize terms like postmodern (Parker 1992; Caporaso 1996), postindustrial (Bell 1976; Kumar 2009), and postbureaucratic (Heckscher 1994; Kernaghan 2000; Josserand, Teo, and Clegg 2006). These terms indicate a transition from early-modern society, which was dominated by more collective structures like states, family firms, trading empires, and traditional professions, to late-modern society, in which individuals are fundamental units of order (Hall and Jacques 1989). This shift has unfolded throughout the post–World War II period, and especially accelerated globally since the 1990s.

A second key structure that has undergone massive historical change is the voluntary association. Like contemporary organizations, informal associations carry the collective purpose of empowered individuals, but they are weakly rationalized. Well-recognized changes have also occurred in associational life, turning early voluntary associations into more formal organizations. Starting in the nineteenth century, the emergence of incorporation marked an important shift in the structure of voluntary action, with legally incorporated nonprofit entities becoming central components of economies (e.g., professional associations), society and culture (e.g., public good groups), and political systems (e.g., towns and political parties) (Creighton 1990; Kaufman 2008). Early in the twentieth century charitable work developed into a secular full-time career option, and the goals of many associations shifted away from the pursuit of Christian duty, charity, and salvation and toward the pursuit of human rights and scientific approaches to curing social ills (Sealander 2003). In these increasingly bounded, incorporated entities, purposes and goals became an issue of choice and identity, rather than a matter of enacting God’s will. Over time, informal associations became increasingly subject to formalization. These changes to associational life are sometimes depicted as creating entities that resemble government bureaucracies (as they increasingly subcontract and take on formal structures), and they do adopt some bureaucratic features (e.g., written policies, full-time career positions). But formal nonprofit organizations are not, by virtue of their collective nature, true bureaucratic hierarchies operating under the authority of an external sovereign.

More recently, observers have also emphasized the commercial transformation of the nonprofit sector and reported on phenomena such as the creation of “hybrid” organizations, social enterprises, and entities led by social entrepreneurs (Dees 1998; Billis 2010; Pache and Santos 2012; Mair, Chapter 14, “Social Entrepreneurship”). Here the rhetoric is that nonprofits are becoming more like businesses because of increased competition (as they take on practices designed to improve efficiency and effectiveness) (Eikenberry and Kluver 2004). Existing explanatory ideas work in part, but they are too narrow to cover the entire scope and scale of the relevant changes. For example, both nonprofits and firms are also becoming attuned to corporate social responsibility practices that extend beyond their core mission or their product-based activities (Pope et al. 2018).

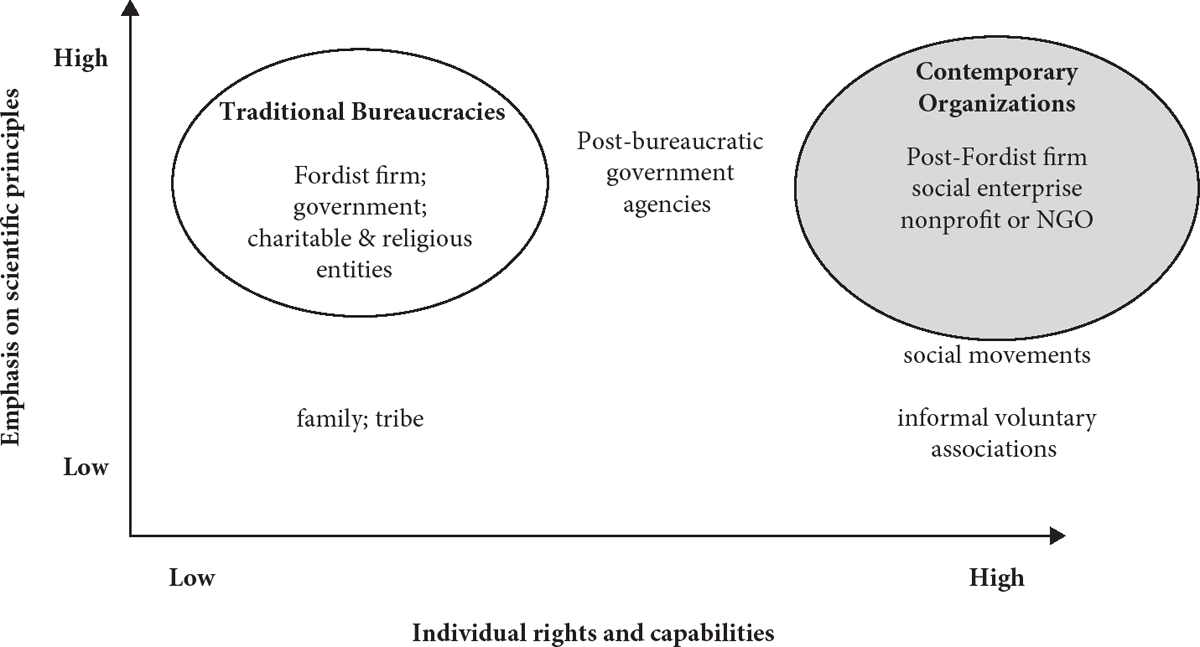

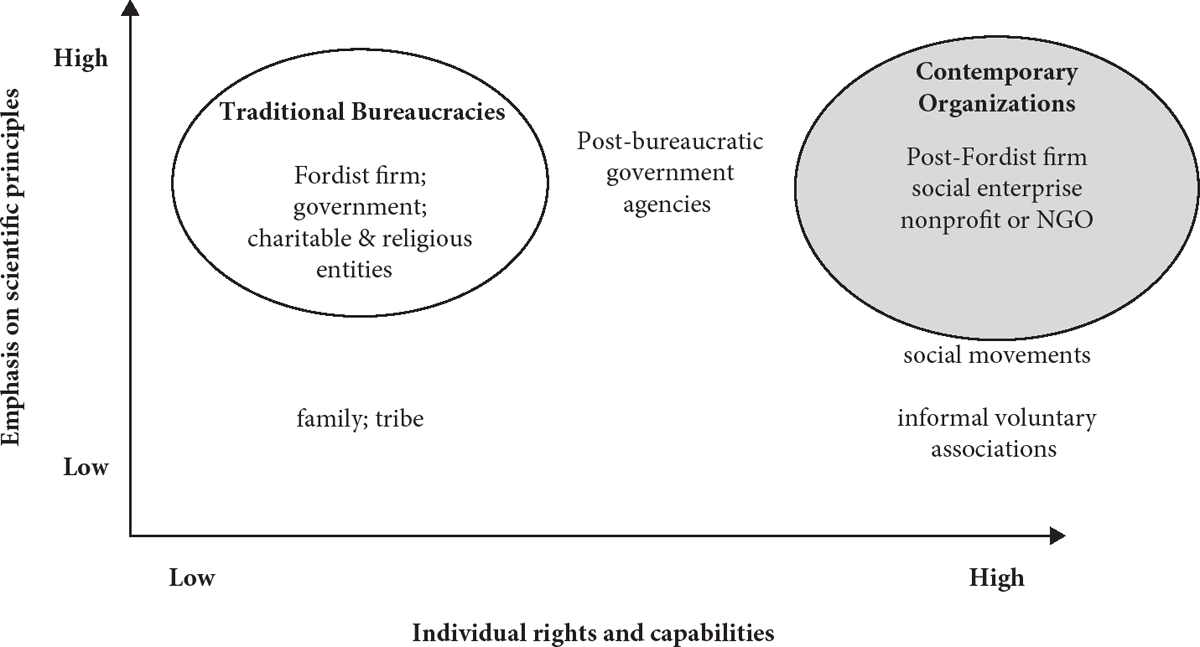

Figure 4.1 The cultural underpinnings of ideal types of social structure

Note: The social structures represented here are roughly classified as ideal types. Empirical research could usefully develop systematic analyses to test the extent to which various types reflect these cultural underpinnings.

Rather than viewing transformations within the nonprofit, government, and business sectors as independent phenomena, this chapter argues that these transformations arise from common cultural roots. According to this argument, voluntary associations, firms, and government agencies are all simultaneously being reshaped by the emergence of a new metacategory—what is now called organization (Bromley and Meyer 2017). These older forms still exist, of course, but they are increasingly reshaped as instances that, at least in part, fall under the broader category of organization.

Figure 4.1 arrays ideal types of social structure along the dimensions of science and rights. Of course, this depiction reflects ideal theory; in practice things can operate far differently and there is variation within each type. Along the x-axis are differences in the extent to which the ideal types reflect assumptions about individual capability for rational decision, choice, and the extent to which individuals possess various rights. Along the y-axis are differences in the extent to which the ideal types reflect assumptions about systematic, scientific principles as driving and ordering collective activity.

In the upper right of Figure 4.1 we have the metacategory of contemporary organizations, highly constituted by both rational, scientific principles and assumptions of human rights and capabilities. For example, post-Fordist firms emphasize inclusive, flatter structures and also seek to maximize profit (e.g., see Amin 2011); more recently, there are depictions of the “conversational firm” (Turco 2016) and “democratic organization” in business (Battilana, Fuerstein, and Lee 2018). Similarly, contemporary, professionalized nonprofits represent the apex of formal organization in the civil society sphere (e.g., entities that have both a prosocial purpose and rationalized structures like strategic plans, vision statements, risk management officers, outcomes measurement, and/or diversity and environmental strategies beyond their own mission). We can also think of ordering entities within the form of “organization” in terms of their profit motivation. Then, between contemporary firms and nonprofits, we find social enterprises: organizations that seek both social good and profit.

Importantly, the claim is not that all organizational forms in the upper right of the figure are exactly alike. We could also emphasize differences between the subforms of organization along various lines—such as profit or purpose. The core argument here is that organization has emerged and expanded as a metacategory in society, becoming the dominant social structure of our time. Entities in the upper right of the figure have more in common with each other than they do with entities in other quadrants. It becomes possible to observe that “although there are many differences between collectivities like factories, prisons, and government agencies, they share one important thing in common: they are all organizations” (Maguire 2003:1, italics added).

The lower and left sections of the figure capture social structures that do not fit what we now mean when we think of an ideal or proper contemporary organization. In the upper left we have another metacategory: traditional bureaucratic structures. Traditional bureaucracies are qualitatively different from what we now envision as a proper contemporary organization. Specifically, theories of bureaucracy outline their construction as efficient tools, but with limited individual rights or capabilities involved for roles beyond the imperative authority of a supreme leader. Ultimate control legitimately resides in a sovereign. Retrospectively, some apply the label of organization to older bureaucracies (e.g., Coleman 1982), but this reflects the rise and expansion of the category of organization—bureaucracies did not receive this label until late in their history (Drucker 1992). Contemporary postbureaucratic public agencies would fall somewhere in between traditional bureaucracies (upper left) and modern organizations (upper right), as they remain highly scientized but increasingly incorporate individual empowerment at all levels (Kernaghan 2000; Brunsson and Sahlin-Andersson 2000; Wachhaus 2013).

Moving to the lower sections of the chart, on the right are informal voluntary associations and social movement activities. These reflect a broad vision of universalistic individual rights and capabilities but have a loose to nonexistent formal structure lacking emphasis on scientific versions of efficiency or effectiveness (e.g., the recent Occupy Wall Street movement [Gitlin 2012]). There may be a drift over time as in, for example, the transition of social movements from being imagined as the utterly irrational “madness of crowds” (i.e., individual participation is voluntary and rather empowered but unscientific) to their current depiction in a vast literature on contemporary, highly strategic, social movement organizations (i.e., moving into the upper right area of the figure over time) (Polletta and Jasper 2001; King and Soule 2007; Bringel and McKenna, Chapter 29, “Social Movements in a Global Context”). In the lower left quadrant are collective and sometimes involuntary social structures such as families; participation may be required and involve very limited protection of each individual, but there is also little formal structure delineating rationalized action (e.g., such an organizational chart). Again, however, over time even some families may shift toward operating as proto-organizations with explicitly defined goals, responsibilities, and evaluation, and participation becomes more voluntary with divorce and child emancipation laws.

Institutionalization and Diffusion3

Several vehicles institutionalize the cultural principles of scientific rationality and individual rights and capabilities, transmitting the model into concrete settings and transforming older structures. Together, these channels construct and diffuse the model of formal organization within countries and worldwide. Hard law and formal regulation is a key mechanism in this process, but other important mechanisms include expansions in soft law (Mörth 2004), various forms of counting and accounting (Power 1999), and the massification of professionals (Wilensky 1964) largely created by changes in education, especially at higher levels (Schofer and Meyer 2005). Hard law and soft law, counting and accounting, and professionalization are vehicles that transmit cultural ideologies. They constitute “organization” as a legitimate social category, turning this imagined entity into an established “social fact” (Durkheim 1982). Instantiations of this cultural model reshape local settings by producing a continuum of entities that fit the imagined category of “organization” to varying degrees.

Hard and Soft Law

Hard laws represent a high form of rationalized social structure, imagining (and to some degree creating) systems that are subject to standardized, predictable rules (see, for example, Max Weber’s discussions of formal bureaucratic rationality [(1922) 1978; see also Kalberg 1980]). Laws powerfully provide an organization with formal boundaries and provide coercive force to the assignment of rights and responsibilities. For example, in the United States, legal developments dating to the nineteenth century granted corporations (including nonprofits, for-profits, and some townships) some of the same rights and protections afforded to individuals (Kaufman 2008). These legal expansions continue through the present; in 2010 the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the protection of free speech for corporations in a case between the nonprofit organization Citizens United and the Federal Election Commission.

Some assert that corporate personhood creates entities that are a mere “legal fiction” (Fama 1980) or a “nexus of contracts” (Jensen and Meckling 1976). But as a cultural construct, the model of “an organization” expands beyond formal legal status. For example, entire industries and a huge amount of management training are premised on the idea that organizations (with managers and executives enacting their essence) can and do act rationally, can plan and control operations, and can have unique cultures that shape outcomes. As another, in the United States religious entities and those with revenues under $5,000 do not need to formally register with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), so in an annual report on the state of the nonprofit sector, the Urban Institute reports that “the total number of nonprofit organizations operating in the United States is unknown” (McKeever 2015:2). In line with the point that legal incorporation alone does not constitute what we mean by “organization,” in their path-breaking comparative analysis of the nonprofit sector, Lester Salamon and Helmut Anheier (1998) come to a “structural-operational” definition of a nonprofit organization rather than a legal one. Legal status and compliance represent part of being an organization but not all of it.

Beyond establishing the legal existence of entities, hard and soft laws shape internal structures and spell out where the boundaries of an organization should be drawn. For example, professional norms and laws defining humans as equal and empowered generate formal structures that advance diversity and equality in hiring, promotion, and governance practices (e.g., see Daley 2002 for nonprofit board diversity, or Dobbin 2009 for trends in firms). A similar trend involves the rise of participatory decision making and collaborative governance processes (e.g., see Epstein, Alper, and Quill 2004 for medicine; Kernaghan 2000 for government agencies; or King 1996 for schools).

Counting and Accounting

The emergence and expansion of standardized methods for counting and accounting drive human activities to become more structured as the bounded, formal entities that we recognize as organizations. Quantification creates a basis for making previously distinct social structures comparable (Espeland and Stevens 1998). So, today, charitable work (even the voluntary sort) is no longer seen as unproductive labor; instead, it is seen as analogous to other forms of production, and its contribution to the economy is calculated annually. One recent study, for instance, calculates the contribution of volunteer work as a share of GNP across countries in 1995 (Roy and Ziemek 2000). Relatedly, there are now measures that enable comparisons of organizational performance across different industries, sectors, and countries (see, e.g., a discussion of nonprofit versus for-profit performance in Keller 2011, or the research produced by World Management Survey 2013). We can also now rate and rank organizations on such dimensions as performance, transparency, and accountability, as well as other forms of social responsibility, thereby enabling the transposition of concern with those dimensions from one domain to another. A number of recent studies examine the creation of charity watchdogs (Lammers 2003; Szper and Prakash 2011) and the rise of measures of social value (see Austin and Seitanidi 2012 for a review).

Professionals

Professionals with university training play a central role in transforming traditional social structures into organizations. Higher education is a key location where socialization into the culture of science and human rights takes place. The worldwide expansion of higher education has reached a level that would have been seen as a massive social problem in any previous period—the fear in earlier times was that overeducation would be a threat to social stability and a waste of resources (Schofer and Meyer 2005). By 2016, nearly 40 percent of the relevant cohort of young people worldwide was enrolled in an institution of higher education—a figure vastly higher than in any previous generation (e.g., in 1970 just 10 percent of the cohort was enrolled [World Development Indicators Online 2018]). This population is no longer concentrated in a few core countries; in peripheral countries, too, the number of university students has increased significantly.

To a large degree, the theory and practice of contemporary formal organization reflects the social behavior of these highly schooled people. In support of this argument, a path-breaking study drawing on a survey of two hundred San Francisco Bay Area nonprofits found that when executives receive managerial training (i.e., in the form of a master of business administration degree, a master of public administration degree, or a certificate in nonprofit management), their nonprofits have more extensive formal structures, such as formal planning, independent financial auditing, quantitative program evaluation, and use of consultants (Hwang and Powell 2009). In the realm of professional training, Roseanne Mirabella and her colleagues have collected detailed data on the growth of nonprofit degree programs over time (Mirabella 2007; Mirabella et al. 2007), and that growth both indicates and facilitates increased formal organization in the nonprofit sector. Overall, evidence of professionalization in the nonprofit sector, often linked narrowly to legitimacy and funding benefits, is widespread (Stone 1989; Alexander 2000; Guo et al. 2011; Suárez 2011).

A brief example, drawn from the expansion of human health concerns inside organizations, helps illustrate these arguments. At one time illness was a mystery to humans, who believed that it was under the control of the fates or gods; poor health was a moral failing, likely punishment for misdeeds in the present life or past ones. Gradually, people came to regard health as something that they could understand and even shape. Eventually, scientific work generated evidence documenting how things invisible to the human eye—microscopic germs, genes, or environmental pollutants—damaged the health of people, animals, and the planet. As individual sacredness expands, ideas of health proliferate further to include new topics such as mood disorders, previously unlabeled mental and physical illnesses, and broad ideas of overall “wellness.” These expanding scientized ideas of health, combined with visions of human rights (and health becoming a human right), spawned activist and interest groups that used the normative pressure of hard and soft law. Such efforts sparked the creation of new groups aimed at improving human health, and the creation of formal regulatory structures (such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA] in the United States, along with related policies and laws). Following scientific cultural principles, moreover, both activists and governments tend to use systematic, evidence-based methods—including tools for tracking, rating, and monitoring environmental quality—to protect the environment. There are now many ways to measure attention to health within organizations and countries (such as the World Development Indicators, or the ranking put out by the World Health Organization [WHO]), and various forms of professionalization (such as degrees in health care management and positions for administering a variety of related employee benefits) have emerged to support specialization in these areas. As a result of these developments, any given entity is now likely to include some kind of health-related policies and practices in its formal structures, and is likely to do so in systematic ways that allow for monitoring, reporting, and evaluating progress. In the business world attention to employee health and wellness is sometimes justified as a way to increase productivity or as a response to consumers or shareholders. But those arguments are too narrow as we see this trend in the nonprofit world as well, where productivity is hard to measure, there are no shareholders, and nonprofits are unlikely to be the target of activist or consumer protests. We could imagine similar shifts for other domains, such as environmentalism, where all types of organizations are more likely to have policies and practices related to “being green” and even entities with social missions sign on to environmental agreements like the Global Compact (Pope et al. 2018).

Discussion

Organizational Actors4

In relevant sociological and management literatures, the recent emergence of organization as a dominant form of social structure is well recognized (Coleman 1982; Perrow 2009). Although precursors have existed for centuries (e.g., early corporations and bureaucracies), these early structures did not penetrate into as many realms of life and they did not valorize individual rationality and rights to the extent they do now. Today, organizations have become so dominant that their existence is taken for granted and naturalized by casual observers; it seems as though they have always been around. But even in developed liberal democracies much of the expansion of organizations occurred after World War II, and globally it has taken off especially since the 1990s (Drori et al 2006, 2009).

As a definitional matter, what makes organizations distinct from other structures is that they combine (a) the rationalization of bureaucracies (e.g., efforts to clarify lines of accountability with standardized rules and to establish links between means and ends through activities like planning and evaluation) with (b) the collective purpose of voluntary associations of individuals (e.g., the entity itself incorporates the purposes of sovereign individuals and thus has its own legitimate goals and interests, as well as the authority to pursue them). As these characteristics become institutionalized through the legal, accounting, and professional channels described earlier, organizations become envisioned as bounded, rational social actors that carry both rights and responsibilities (Brunsson and Sahlin-Andersson 2000; King, Felin, and Whetten 2010).5 For instance, conceptions of organized entities as analogous to persons or “fictive individuals,” in some phrasings, have long standing in a variety of legal systems (Hansmann and Kraakman 2000). James Coleman classically outlines the legal institutionalization of organizations as bounded entities (1982:14):

the conception of the corporation as a legal person distinct from natural persons, able to act and be acted upon, and the reorganization of society around corporate bodies made possible a radically different kind of social structure than before. . . . It [the corporation] could act in a unitary way, it could own resources, it could have rights and responsibilities, it could occupy the fixed functional position or estate which had been imposed on natural persons.

Importantly, however, the status of organizations as social actors goes beyond narrowly legal conceptions (Krücken and Meier 2006). Organizations are treated as independent and coherent actors in the media, the theory and practice of management, and the general social imagination. Broadly speaking, to be recognized as an actor of any sort (e.g., a person, an organization, or even a country) means that an entity possesses sovereignty, can pursue its own purposes, and has an identity or “self” (Coleman 1982; Pedersen and Dobbin 1997; King et al. 2010). For example, John Meyer (2010:3), writes: “An actor, compared with a mundane person or group, is understood to have clearer boundaries, more articulated purposes, a more elaborate and rationalized technology. An actor is thus much more agentic—more bounded, autonomous, coherent, purposive and hard-wired.” To get counted as an organizational actor indicates broad legitimacy to participate in society as an autonomous creature—one that is reliant on various stakeholder groups but distinct from them.

Decoupling

A core observation is that the evolving cultural model of an organizational actor is just that—a model or an imagined cultural ideal. It is not a ground-up description of what entities actually do or look like. And it is an imagined entity held together by social construction, not a naturally occurring creature. Thus, actual structures differ in how close they come to the vision of “an organization,” and empirical studies can explore this variation (see, e.g., Bromley and Sharkey 2017). Organization theory commonly notes significant gaps between models of reality or theories about how things should work and the experienced world (in sociology, see discussions of “decoupling” in Meyer and Rowan 1977 and Bromley and Powell 2012). For instance, we are likely to recognize the Red Cross as more of a “real organization” than a family foundation that exists mainly on paper as a tax shelter; although the two entities may have a similar legal status, one of them has greater sovereignty, purpose, and identity. Organization is often partial, and it can refer to certain activities or ways of thinking that occur within structures that are not themselves complete, formally incorporated entities (Ahrne and Brunsson 2011). Terms like organizing and getting organized are routinely applied to practices in settings that do not involve official incorporation. Although the archetype of an organization has a defined sovereignty, purpose, and identity, any given organization is likely to be characterized by areas of limited autonomy, multiple views of its identity, and conflicting conceptions of its purpose. But a more sophisticated organization seeks at least to present itself as aligned with the ideal model, and it may at times try various reforms to become more aligned with that model.

As a parallel to the decoupling between the ideal of organization and the practice of it, consider the example of bureaucracy. Actual bureaucracies routinely fail to work according to theory. The chain of command often breaks at some point, as bureaucrats pursue interests of their own (a practice now often called corruption) or reinterpret rules in inventive ways (Dwivedi 1967; Mbaku 1996; Lipsky 2010). Or rules that make no sense in particular local settings are ignored or followed only in ritual (E. Weber 1976). Despite many deviations from practice, the ideology of bureaucratic control, carrying out the will of a sovereign certified by religious, historical, or dynastic authority, has been central to modern societies, often permitting social control on a vast scale. Similarly, organizations that are recognized as more complete actors have sovereignty, purpose, and identity; in practice there is a continuum, and actual entities diverge from the concept.

Beyond the straightforward decoupling of theory or policy from reality or practice, being a proper organizational actor involves a great deal of decoupling between means and ends (Bromley and Powell 2012). Cultural shifts drive an expansion both in the number of organizations and in the range of domains where formal organization takes hold. As a result, there are a growing number of audiences and issues that any given organization must take into account in order to be considered a responsible actor (Bromley and Meyer 2015). As organizations respond to expanding pressures in their environment, they become less coherently structured around their purported goal. Although organizations are depicted as autonomous and rational, they are held together by external definitions that include many inconsistencies and contradictions.

Research Directions

Existence: Fundamental issues related to the existence and nature of nonprofits remain weakly studied, but the rapidly increasing availability of data opens the door for new possibilities. Several research directions emerge from the arguments presented here. As noted at the outset, traditional failure-based theories look to answer questions about when nonprofits, as opposed to for-profit entities, are likely to appear. This chapter takes a different approach, situating the expansion of nonprofits within the expansion of organization in general. Functional explanations rooted in efficiency or effectiveness may explain the rise of formal structures in part, but a cultural view helps explain the timing and accounts for the massive expansion of organization into all areas of life and around the world, beyond known utility. A sophisticated understanding of both functional and cultural arguments reveals that these arguments do not always represent logically discrete worldviews. Rather, they direct attention to somewhat different observations and questions. This chapter urges greater focus on organizational expansion as a key feature shaping the evolution of the nonprofit sector, pointing out that the conceptual utility of for-profit or nonprofit legal status diminishes as sectors blur. In contrast, failure theories seek to explain why organizations take a nonprofit or for-profit legal status, obscuring the historical context of organizational expansion and sector blurring. Empirically, multiple causal forces are likely to be at work, and future studies could work toward understanding the conditions under which settings are likely to be driven more or less by functional efficiency, culture, or alternatives such as elite power. Plausibly, domains with greater technical certainty are less susceptible to being structured by cultural influences because efficiency is self-evident. Thus, domains with greater complexity or uncertainty (slippery concepts, to be sure) may be more easily structured by cultural expectations and thus may experience greater organizational expansion. To the extent that we believe profit goals have more technical certainty than prosocial goals, cultural pressures may drive organizational expansion the most in prosocial areas (including nonprofits and the socially responsible areas of for-profits).

Expansion: This chapter argues that organizations are only partly constructed as a functional response to societal “needs” and that they arise largely because of shifts in underlying cultural conditions. To test this argument, future research could examine where and when the expansion of formal nonprofit activity is most likely to occur. A core hypothesis is that there is likely to be a higher degree of formal organization in settings where liberal principles related to science and human rights flourish (e.g., perhaps in places marked by a growing commitment to education, especially at higher levels). Conversely, on average there is likely to be a lower degree of formal organization in settings marked by alternative bases of authority (e.g., in the form of strong religious belief or a strong centralized government). These hypotheses, which can be tested directly, are in contrast with the view that nonprofits exist solely in order to fill gaps left by the state or the market, although no single explanation need exist alone.

A related hypothesis, emphasizing historical timing, would posit a rapid worldwide expansion of formal nonprofit organization immediately following World War II, when the first steps to create a liberal world order were under way, and again immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, which represented the main global alternative to liberalism. Over more than a century, modern history has witnessed an expansion of principles of science and rights. But in the arguments here, there is no theoretical basis for expecting an inevitable march toward liberal modernity in perpetuity; the causes of changing macrohistorical trends are complex and not fully understood, leaving much room for uncertainty about the future. Recent global resurgences of populism, declining democracy, and growing doubt in the neoliberal economic model may indicate an erosion of the liberal cultural model worldwide; if so, nonprofit organization as we know it is likely to be undercut.

Taking a different angle, studies of the extent to which adaptation or selection processes are at work in turning civil society into a formal organizational sector would shed light on the process. We know that the rate at which new nonprofits are founded in the United States has increased markedly in recent decades, but we have little knowledge about the extent to which older structures retain distinctiveness relative to newer ones, or in what ways. Some studies suggest that adaptation also plays a role. Catholic orders, for example, began to reimagine and register formally as INGOs in the 1950s (Wittberg 2006; Gonzalez 2009), and clergy in some denominations have gone into the business of being event planners to adapt to the preferences of their congregation (Putnam and Campbell 2012). Others have looked at the transitions from bureaucratic to postbureaucratic agencies (Josserand et al. 2006). Again, analyses to help understand which domains or dimensions retain distinctiveness or resist pressures toward formal organization and why would be valuable.

Sector Blurring: The blurring of sectors into more standardized contemporary organizations around the world is well documented (Brass 2012; Marshall and Suárez 2014). A cultural view argues that as trends toward scientific rationality and human rights grow, social structures take on the features of what we now call organizations beyond market pressures. For example, organizations seek to become more “professional,” and they incorporate broader concerns related to responsibility—such as codes of conduct, whistleblower policies, and strategies for being “green”—regardless of established links to a particular mission or profit. In contrast, economic explanations often take a narrower emphasis on marketization of nonprofits (Billis 1993, 2010; Dees and Anderson 2003; Eikenberry and Kluver 2004), overlooking general professionalization. Economic explanations also tend to locate changes in prior resource dependencies without analyzing why those conditions are themselves altered (e.g., why funders start caring more about measuring the impact of nonprofits or why shareholders start caring more about displays of social responsibility on the part of firms) (Weisbrod 1997). And economic views often focus on a one-way transfer of business practices into the nonprofit world and commercialization (Weisbrod 1998; Young and Salamon 2002; Dart 2004), underemphasizing the extent to which sector blurring is multidirectional. For example, firms have increasingly prosocial and expressive elements as a result of the rise of corporate social responsibility, workplace charity, “social intrapreneurship,” and movements to allow greater self-expression in the workplace. Economic and cultural arguments can be tested empirically, for example by generating lists of the organizational structures associated with market pressures versus those associated with being an actor more generally (e.g., as indicators of “identity” perhaps mission or vision statements, or statements of organizational history, or branding activities) and observing diffusion (or not) across various samples of organizations with different resource needs or dependencies.

Variation: Although we should not disregard organizational form or sectoral differences as an important ongoing area of work (Knutsen 2012), the cultural arguments put forth here point toward a different, but equally central, kind of variation: in contemporary organizational society, the differences between more-formal and less-formal entities and sectors may be sharper than the differences between nonprofit and for-profit organizations and sectors. For example, large educational or health care organizations (which can and do take both nonprofit and for-profit forms, located in the upper right of Figure 4.1) may have far more in common with each other than they do with more informal-associational or bureaucratic entities within those fields.

Another form of variation highlighted by cultural arguments is that manifestations of the cultural model of “organization” is expected to vary greatly in real entities. Research could empirically examine gaps between formal models of organization and practical instantiations, and could then develop general arguments about where and why decoupling is likely to occur in the nonprofit sector.

A third important form of variation is persistent cross-national variation, which continues to exist alongside worldwide organizational expansion (in line with Salamon and Anheier’s [1998] social origins model; see also Anheier, Lang, and Toepler, Chapter 30, “Comparative Nonprofit Sector Research”); these differences could exist in both the discourse of organization and the practice of it. Indeed, over time growth trajectories that proceed at different rates will lead to greater cross-national differences in absolute terms. As explanatory indicators, ties to a liberal cultural framework or to an alternative social structure (e.g., religious entities, which may remain different from their secular counterparts; see Fulton, Chapter 26, “Religious Organizations”) may explain some cross-sectional variation in absolute levels and in growth rates.

Effects: A final set of issues that link the emergence and expansion of formal nonprofit organization involves their instrumental effects. The demand-driven view assumes that these organizations fill a prosocial, functional role, while a cultural view is agnostic about the effects of any particular nonprofit. The arguments put forth here suggest that nonprofit organization may be correlated with other features that are normatively valued in more-liberal societies (e.g., nonprofit organizations and more education or liberal democratic freedoms). But nonprofits themselves may not directly and causally create all of the associated public value (e.g., improved education, health care, democracy, environmentalism). The argument is that an underlying cultural shift unfolding at the macro level may be partly driving related social changes (see Bromley, Schofer, and Longhofer 2018 for a deeper discussion of the relationship between domestic education nonprofits and education outcomes). We still lack causal research that isolates the effects of nonprofit work from the potential influences of broader, contextual trends. Similarly, creative research designs are needed to test beliefs about the effects of particular organizational structures (e.g., “partnerships” or “strategic planning”) on desired outcomes across many entities.

Implications and Conclusions

The nonprofit sector has continued to grow in overall size, in the total number of organizations, and in global reach, and it has become increasingly formal, complex, and professionalized. Building on theory from organizational sociology, I argue that this growth is part of a general trend of organizational expansion. The modern system of distinct states, firms, churches, and schools—which prevailed in the early post–World War II period—is transforming into a late-modern system in which these once-diverse entities can become instances under the common frame of “organizations.” In becoming organizations, precursors to the nonprofit form take on new features. They shift, for example, from deriving mission and legitimacy from traditional sources (such as God or community) toward operating as autonomous actors that are able and entitled to determine their own goals and purposes (Drori and Meyer 2006; Meyer 2010).

One explanation of this shift is two horrific world wars that undermined government-based control, creating supports for alternative forms of a more global social order. In the postwar period of American dominance, centralized nation-state solutions (including a world state) to social problems became less feasible, and an alternative idea of order rooted in science and in expanded individual rights and capacities took center stage. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, an even more aggressive celebration of individualism took hold. Social structures worldwide transformed and new ones were created, reflecting these cultural beliefs in scientific rationality and individual rights and capacities. Thus, the growing number and the increasing internal complexity of organizations are driven by a key phenomenon: worldwide cultural change. This argument should not be interpreted as suggesting an inevitable trajectory toward organizational expansion. In fact, I posit the opposite: the worldwide rise of an organizational society rests on the globalization of liberal cultural ideologies of progress and modernization rooted in individualism. Therefore, if these cultural roots shift or are reversed, social structures will change as well. In an alternative world society—for example, one built around central imperial structures—“organization” as we know it would be a less central form of social structure.

One key implication of this argument involves the need to reflect on what is gained and lost as the business, government, and nonprofit sectors blur. Some see the differences between sectors as relatively immaterial and are untroubled by this trend (Dees and Anderson 2003). For instance, in response to a query about business schools that have programs for nonprofits, one scholar responded, “our primary focus is on organizational theory. We believe you can apply it to any type of organization” (Orgtheory.net 2012). Others call for greater attention to the unique elements of public and nonprofit management (Frumkin 2002; Eikenberry and Kluver 2004). A number of excellent studies document how nonprofits try to maintain their expressive (or identity) functions in spite of increasing formalization, or how they reconcile charitable goals with more instrumental pressures (Chen 2009; Knutsen and Brower 2010; Suárez 2010).

This chapter does not argue that organizational expansion and increasing similarity across the sectors creates charities or government agencies or firms that are more (or, for that matter, less) efficient or effective. Nor are the new structures thought to be inherently more (or less) just or socially beneficial or productive than before. At the societal level, it is unclear whether having more nonprofits and government agencies with, for example, systematic performance metrics means that as a whole they are producing better outcomes than before, or whether having more firms with socially responsible structures improves practices.

Several possible concerns arise. Whereas charitable structures in years past could hang much of their legitimacy on tackling a widely shared social purpose or serving a legitimate sovereign, contemporary nonprofit organizations are constructed as autonomous actors and thus increasingly face demands to justify their existence and their work. Pressures for accountability and responsibility arise in the nonprofit sector, along with the related concepts of performance and impact measurement. This parallels the general rise of pressures toward corporate social responsibility in for-profit organizations. Indeed, firms, government agencies, and nonprofits begin to adopt many of the same corporate social responsibility policies and practices (Pope et al. 2018). They all begin to stress their general social responsibilities as organizational actors through things like sustainability reporting, community outreach programs, multistakeholder initiatives, and “good governance” practices such as codes of conduct, whistleblower policies, and risk management procedures. Overall, the legitimacy of charitable structures shifts to reside as much in adopting the trappings of proper organizational actors as in their mission.

The internalization of inconsistencies associated with the expanding responsibilities of being a proper organizational actor can create entities that are rather paradoxical: organizations increasingly claim capacity for autonomous, rational action on many fronts while, at the same time, becoming more enmeshed in a web of responsibilities to diverse stakeholders that limits their actual autonomy. As a result, “responsible” organizational actors may become more accountable but less efficient.

The social controls involved specify that it is less legitimate to overtly pursue narrow self-interests, particularly if they impinge on other actors. In the contemporary organizational world, a great deal of effort goes into displays of accounting for the interests of other stakeholders within a pluralistic society; even powerful actors like foundations seek comply at least in appearance (Brandtner, Bromley, and Tompkins-Stange 2016). But ultimately, social controls are a weakly enforceable mechanism, and displays of responsibility can differ wildly from actual practices, leaving a great deal of leeway for immoral and self-interested action. As Francis Fukuyama writes, “One person’s civic engagement is another’s rent-seeking; much of what constitutes civil society can be described as interest groups trying to divert public resources to their favoured causes. . . . There is no guarantee that self-styled public interest NGOs represent real public interests. It is entirely possible that too active an NGO sector may represent an excessive politicization of public life, which can either distort public policy or lead to deadlock” (2001:12). Legal oversight of organizations’ responsibilities has perhaps not caught up to their rapidly expanding rights, leaving the system vulnerable to corruption and self-interest. Some advocate for a more rigorous corporate criminal justice system—complete with an organizational “death penalty” in egregious cases (Grossman 2016; Ramirez and Ramirez 2017).

A final implication of these arguments is that, as a social-structural manifestation of cultural ideologies rooted in individual empowerment, formal nonprofit organization is likely to be undercut if the liberal world order weakens. Indeed, we see increasing opposition to nonprofit organizations alongside contemporary resurgences of populism, nativism, and nationalism worldwide (Dupuy and Prakash, Chapter 28, “Global Backlash Against Foreign Funding to Domestic Nongovernmental Organizations”). This is of great concern as the world has enjoyed a period of long advancements in human development and expansions in rights. At the same time, many of the benefits we now attribute to nonprofits can and do take other forms that often aren’t “counted” in the formal sector—for example, through stronger extended family units or centralized provision of social services by state bureaucracies. Moreover, even accountable organizations can be a source of inequality, as the level of professionalization involved requires high levels of education that exclude vulnerable groups from full participation (see Bloemraad, Gleeson, and de Graauw, Chapter 12, “Immigrant Organizations,” for a related discussion of civic invisibility). Observing that nonprofits are increasingly instances of formal organization should draw our attention toward their capacity for both good and evil: they can be vehicles for exclusion and reinforcing elite power—or sources of inclusion and democratization. They can perpetrate corruption—or serve as watchdogs of the public good. They can be sites of dehumanizing conformity—or venues that promote free expression.