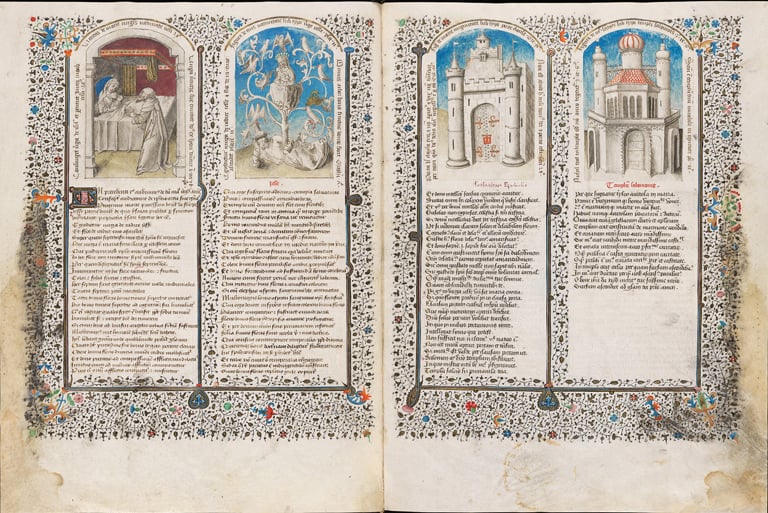

Figure 1.1 Speculum humanae salvationis, Paris/Flanders, 1430–50

Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 206 (49) fols.5v and 6r (www.e-codices.ch)

The Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of human salvation) was one of the most widely disseminated and influential works of the late Middle Ages. Thought to have originated in the early fourteenth century, this text uses the medieval system of typo-logical representation to illustrate events from the story of salvation, many of which are drawn from the apocrypha. Following earlier precedents, the Tree of Jesse is used as a prefiguration for the Birth of the Virgin. The subject is therefore not only placed in a Marian context, but is also linked to the mother of the Virgin, Saint Anne, whose popularity reached a peak in northern Europe during the course of the fifteenth century.1 The influence that these manuscripts and subsequent blockbooks had on late medieval iconographic programmes has long been recognised, although exactly how these texts might have acted as the agent for a shift in contemporary perceptions of the Tree of Jesse motif has not been previously considered. This chapter will discuss the Speculum humanae salvationis in some detail, to ascertain to what extent it might have encouraged and influenced renewed interest in Tree of Jesse iconography.

The earliest Speculum manuscripts are thought to have originated in Germany, sometime before 1324, the date recorded in the first known copies.2 Even before 1450, the geographical dispersal of the manuscripts was extraordinary, reaching as far as Dortmund in the north, Prague in the east and Toledo in the south.3 Originally in Latin, the earliest translation seems to have been into German, whilst the British Library has a Flemish copy dating from the early fifteenth century, known as the De spieghel der menscheliker behoudenesse (Add Ms. 11575), and the Haarlem Stadsbibliotheek has a copy in Dutch, the Spieghel onser behoudenisse (Ms. 11.17).4 In 1448, Jean Miélot was commissioned by the Duke of Burgundy to translate the text into French; this edition was known as the Miroir de la Salvation humaine, and although the original manuscript is now lost, the draft, or minute, still survives in the Royal Library of Belgium (Ms. 9249–50).5 Nearly four hundred manuscript copies from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, mostly in Latin, but also in German, Dutch, French, Czech and English, have been catalogued, providing convincing evidence of the Speculum’s widespread appeal.6

In manuscripts, the Speculum usually occupies fifty-one leaves, one hundred and two pages. Although there is disagreement among scholars, it is believed that at least a third of all surviving examples are illustrated.7 After a short prologue of two pages and prohemium of four, both without illustrations, there are forty-five chapters covering all the major events in the biblical story, starting with the Creation. The first two chapters describe the Fall of Lucifer and other important events taken from Genesis, and, consequently, have no Old Testament prefigurations. The final three chapters are of double length and are devoted to the Seven Stations of the Passion, the Seven Sorrows and the Seven Joys of the Virgin. Once again, their miniatures are not typological. The remaining forty chapters take an event from the story woven around the life of the Virgin or the scriptures and link it to three Old Testament episodes believed to have foreshadowed it. Although there are exceptions, traditionally these chapters follow a similar layout, with a double page opening containing four text columns, each of which is headed by a miniature pertaining to the text beneath. The first image represents the main event and the following three are typological. A whole chapter can therefore be read at one opening, the images visible concurrently across the top of the double page spread, as seen in the Speculum manuscript from the Einsiedeln Abbey Library of c.1430–50 (Codex 206 (49) fol.5v and 6r) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Speculum humanae salvationis, Paris/Flanders, 1430–50

Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 206 (49) fols.5v and 6r (www.e-codices.ch)

The Speculum, according to its author, was a book for the instruction of both laymen and clerics, and a key theme throughout is its devotion to the Virgin. ‘Those who instruct many men in righteousness will shine like stars forever. For this reason I decided to compile a book to teach many people, from which they can both receive and give instruction’.8 Following the description of the Creation and Fall, the story of salvation begins in Chapter Three with the annunciation of the Birth of the Virgin. Prefigurations given for this event are King Astyages’ dream of his daughter, from Comestor’s Historica scholastica; a garden enclosing a sealed fountain, from the Song of Solomon; and Balaam’s prophecy of the birth of Mary, from Numbers.9 Astyages dreamt of a beautiful vine that grew out of his daughter, the vine had leaves and branches bearing fruit, which spread out over his entire kingdom. Following his dream, Astyages’ daughter gave birth to a son, King Cyrus, who freed the children of Israel from the Babylonian Captivity. Therefore, just as Astyages is shown that his daughter will give birth to Cyrus, Joachim is shown that his daughter will bear Christ the King, and just as Cyrus liberated the Jews, Christ frees man from the bondage of Satan. Thus, the daughter of Astyages prefigures Mary and the annunciation of the Virgin’s birth is the beginning of man’s salvation. The dream of King Astyages, like the Tree of Jesse, represents the fulfilment of a genealogical prophecy and is the first indication of the manuscript’s preoccupation with the ancestry of the Virgin.

Chapter Four discusses the actual birth and lineage of the Virgin, opening with Isaiah’s prophecy. This was not the first time however that this had been directly linked to the Virgin’s birth. At the beginning of the eleventh century, Fulbert of Chartres had composed an influential responsory for the Feast of the Birth of the Virgin known as the Stirps Jesse. This proclaimed ‘The stem of Jesse brought forth a rod, and that rod a flower, And upon that flower rests God’s blessing. The virgin and the mother is the rod, the flower her son’.10 In her article relating to the celebration of the Nativity of Mary, Margot Fassler suggests that this association had its origins in the late eighth or ninth centuries, when Carolingian liturgists transformed the Feast by changing the Gospel text traditionally used in the Roman rite (the story of the Visitation recounted in Luke), to the genealogy of Christ recounted in Matthew.11 This shift consequently placed an emphasis on lineage and implied that Mary herself was descended from David. It is unsurprising then that Isaiah’s prophecy subsequently came to be more widely connected with the Virgin’s birth, and there are some early examples where the Tree of Jesse was used to illustrate the lesson for the Feast, as in the thirteenth-century Gospel Lectionary from Sainte-Chapelle (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. Latin 8892, fol.13v), where the motif decorates the first initial of the Liber generationis of Matthew 1.1.12 This association continued to be popular and can be seen again in the illumination of the Nativity of the Virgin in the early fifteenth-century Lovell Lectionary (British Library, Harley 7026, fol.27) (Figure 1.2).

The idea that the Tree of Jesse foreshadowed the Virgin’s birth was therefore established from an early date, yet the source for stories surrounding this event and the early life of the Virgin came not from the scriptures, but the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James, the Gospel of Pseudo Matthew and the De Nativitate Mariae.13 These stories were further popularised from the thirteenth century onwards when the Italian Dominican, Jacobus de Voragine (d.1298), included them in his anthology of saints’ lives known as the Legenda aurea, or Golden Legend.14 This text became hugely influential in the following centuries. It appears to have been particularly popular in Germany and the Netherlands, where it was translated into the vernacular more often than anywhere else.15 Voragine’s narrative makes it clear that the Virgin was descended from the tribe of Judah and therefore the royal stock of David. This was important, because if Joseph was not the biological father of Jesus, who had been immaculately conceived, then to be in accordance with the prophecy of Isaiah, Christ’s descent from David must be via Mary. Voragine goes on to explain that the Virgin’s absence in the genealogies of the Gospels of both Matthew and Luke, which trace Christ’s male descendants to Joseph, can be put down to Hebrew tradition, which dictated that only the male line was described.16

The miniature illustrating the Birth of the Virgin in the Speculum usually features Saint Anne, lying in bed with the newborn child, and the Virgin’s father, Joachim, at her side (Figure 1.1). Alongside is the image of the Tree of Jesse, and beneath these

Figure 1.2 Nativity of the Virgin, Lovell Lectionary, 1403

©The British Library Board, Harley 7026, fol.27r

miniatures, the text asserts (as it does in the Golden Legend) that Mary was descended from David. The narrative then goes on to interpret Isaiah’s prophecy, stating that the rod from the root of Jesse signifies Mary, who is made fruitful by heavenly dew, and produces for us Christ, the most beautiful flower (See Appendix 1). As discussed in the Introduction, this was not a new concept: the Virgin had often been assigned a preeminent position in Tree of Jesse iconography from as early as the twelfth century. However, the use of the motif as a prefiguration for her birth in this manuscript shifts the emphasis from the messianic nature of Isaiah’s prophecy to an affirmation of the Virgin’s Davidic and royal paternity. The narrative then goes on to explain the second part of Isaiah’s prophecy, that within the flower of Christ are found seven efficacious remedies for the various sicknesses of the soul, which correlate to the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. It is not unusual, therefore, to find Speculum manuscript illuminations that feature seven doves on the branches of the tree.

In addition to the Tree of Jesse, the two other typological events used to illustrate the Birth of the Virgin are Ezekiel’s vision of a closed gate and the Temple of Solomon.17 Ezekiel’s vision pertains to Mary’s virginity, before and after the Birth of Christ. Mary is born to the line of Jesse, we are told, but how the flower blossomed is revealed in the image of the closed gate. The text also explains how the Temple of Solomon can mystically prefigure the Birth of the Virgin. The temple had three pinnacles, which signified Mary’s celestial crown, the exterior was constructed of white marble and the interior was decorated with gold. Likewise, Mary radiates the dazzling splendour of the purest chastity and inwardly possesses the gold of the most precious charity. The association between the Tree of Jesse and Ezekiel’s vision of a closed gate has a long tradition, and, as previously discussed, can be seen in one of the earliest known representation of the motif in the Vyšehrad Codex (Figure 0.1). The association with the Temple of Solomon, however, is much rarer.

The tree motif is used for a third time in Chapter Eight of the Speculum manuscript, which discusses the Birth of Christ. Here the text provides a mystical interpretation of the dream of the vine of Pharao’s cup bearer (Genesis 40:1–23), Christ is the vine, but Mary is the earth from which he grows. Therefore, an analogous connection is made between the annunciation of the Virgin’s birth, the birth itself, and the nativity of Christ. A fifteenth-century manuscript in the Morgan Library in New York takes this connection one step further by using the same tree type to illustrate all three events (Ms. M385, fols 5v, 6v and 10v).

When present, the miniatures act as a kind of mnemonic, reminding the reader of the content of each of the chapters. However, regardless of whether the Speculum manuscripts are illuminated or not, the use of Isaiah’s prophecy as a prefiguration for the Birth of the Virgin can be seen as part of an overall desire to clear up any confusion regarding the genealogy of Christ, which may arise from the concept of the virgin birth. Consequently, Mary’s crucial role in the story of salvation is highlighted, and it also places a new emphasis on the part played by her parents, particularly her mother, Saint Anne.

The figure of Saint Anne and the myth woven around the story of her life were extraordinarily popular in Germany and the Netherlands in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Even Martin Luther commented on the astonishing explosion of her cult:

As I recall it the big event of Saint Anne’s arrival happened when I was a boy of fifteen [1498]. Before that nobody knew anything about her; then a fellow came and brought Saint Anne. She caught on right away, and everybody was paying attention to her.18

Exactly how influential the Speculum manuscripts were in creating a connection between the Tree of Jesse motif, the genealogy of the Virgin and, by association, Saint Anne, can only be surmised. However, it does seem significant that this was one of the earliest books to be printed, appearing in the second half of the fifteenth century, shortly after the blockbook edition of another popular devotional text, the Biblia pauperum.19 Not only did this mean that the Speculum was now able to reach a much wider audience than was ever possible in manuscript form, but also its illustrations became far more readily available as a source for artist’s models.

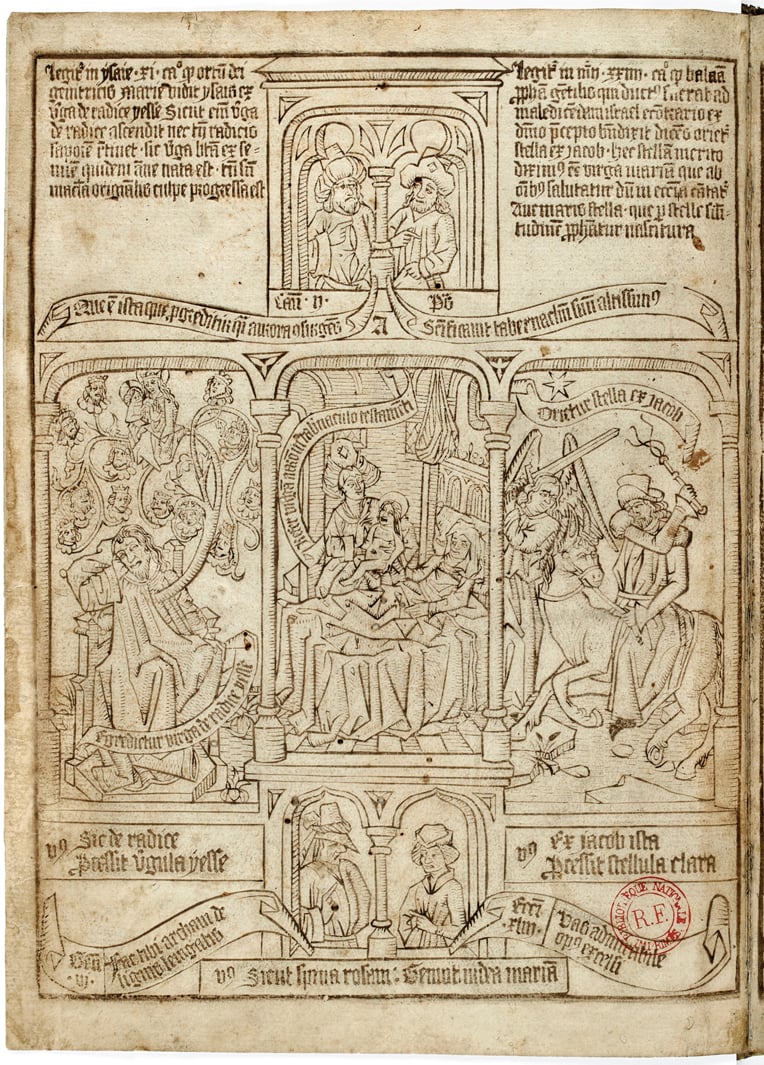

It is generally agreed that the earliest blockbook editions of the Speculum were first produced somewhere in the Low Countries.20 There appear to be four early editions: two in Latin and two in Dutch. The first Latin edition was produced in c.1468 and the first Dutch edition in c.1471.21 These blockbooks are shorter than the completed manuscripts; they have no prologue, just the prohemium, and include only twenty-nine of the forty-five manuscript chapters. The first twenty-four chapters follow the same configuration as the manuscripts, with a woodcut containing two scenes and captions in Latin at the top of each page. Apart from a few exceptions, virtually all subsequent Speculum blockbooks followed the illustrations of the earliest prototypes. Therefore, although the images may differ in style from one edition to another, they are fairly consistent in their iconography. In all editions, as in the illuminated manuscripts, the Tree of Jesse appears in Chapter Four alongside the Birth of the Virgin, with the associated text appearing in two columns beneath, as can be seen in a Netherlandish blockbook in the British Library (shelfmark G.11784) (Figure 1.3). Opposite is the illustration of the closed gate of Ezekiel and the Temple of Solomon.

The same woodcuts were used throughout the four early editions, their shape and dimensions clearly indicating that they were always intended for use in a book format. Despite this, it seems that the illustration of the Tree of Jesse may have been instrumental in popularising a form of representation that became particularly commonplace across all media in the Netherlands in the second half of the fifteenth century. Jesse appears asleep on a gothic chair in a garden; he is bearded and rests his bare head in his left hand. The shoot rising from his chest divides into branches, which have leaves and flowers and, in the corolla of the flowers, sit the heads of twelve kings. Directly above Jesse, sitting on one of the branches, is the Virgin, who is both crowned and haloed. She is holding the naked Christ Child on her lap with her left hand and has a round object, perhaps a reference to the apple of Eve, in her right. Christ, who also has a halo, raises his right hand in a gesture of benediction. Cut into the block beneath this scene are the words of Isaiah’s prophecy ‘egredietur virga de radice Jesse’.

Émile Mâle’s suggestion that Jesse appeared seated for the first time in the Speculum is incorrect, as many manuscript illustrations of seated Jesses can be identified before this date.22 Arthur Watson, for example, gives several instances of a seated Jesse, dating from one of the first known representation of the motif in the Vyšehrad Codex.23 A precedent for kings depicted as half figures in blossoms on the tree can be seen in the Parisian Bible Historiale of c.1414–15 (Royal Library of Belgium, Ms. 9002, fol.223r) (Figure 0.8), and both elements can be found together in a large Latin manuscript containing the Catholicon by Johannes Balbus of Janua, inscribed with the date ‘25 January 1457’ (Royal Library of Belgium, Ms. 102–03, fol.57)

Figure 1.3 Birth of the Virgin and Tree of Jesse, Speculum humanae salvationis, Netherlandish Blockbook, c.1473–75

©The British Library Board, G.11784

(Figure 6.2).24 Nevertheless, it does seem likely that the widespread distribution of Speculum texts from the 1470s would have had an impact on future forms of Tree of Jesse representation.

Following the early blockbooks, no fewer than sixteen incunabulum editions of the Speculum, by eleven different printers, were issued before the end of the fifteenth century.25 Printed in Latin, Dutch, French and German, all had woodcut illustrations, ensuring that the Tree of Jesse motif increasingly came to be associated with the genealogy of the Virgin and Saint Anne. The first of the Speculum texts to be printed with new woodcuts came from the press of Günther Zainer of Augsburg in 1473.26 This was followed in 1476 by a German translation, the Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis, printed by Bernhard Richel in Basel, which also had a new set of vertical woodcuts, partially derived from Zainer’s blocks. The design of these German woodcuts differs to a certain extent from the earlier blockbooks; in both Jesse is shown recumbent on a bed and is crowned, even though he is not a king, and the Virgin is shown without the Christ Child, perhaps implying that she alone can also been seen as the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecy. Although there is no intrinsic significance in the position of Jesse, it may be relevant that in German works of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries it is more usual to find a recumbent Jesse, in common with the woodcuts published by Zainer and Richel.

The use of the Tree of Jesse as a prefiguration of the Birth of the Virgin can also be found in an edition of the Biblia pauperum. Usually this text has forty pages, and its illustrations, which depict events and their prefigurations from the Life of Christ, do not feature the Tree of Jesse motif. In c.1480–85, however, a fifty page edition was produced. This was fundamentally an extension of the forty page edition which incorporated ten new subjects, including the Birth of the Virgin.27 The Tree of Jesse appears with Balaam’s prophecy, flanking the depiction of the birth (Figure 1.4). Unfortunately, only one copy of this blockbook still survives (in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris) and we have no way of knowing how many copies were originally printed, or if any other editions were ever produced. Nevertheless, its existence provides further evidence that, by the end of the fifteenth century, the Tree of Jesse motif had become irrevocably linked with the Virgin’s early life and genealogy.

Although there are connected texts and captions in Latin, the Biblia pauperum is essentially a picture book, and it is through the relationship between the pictures on each page that the reader understands the intended meaning. The Birth of the Virgin is the subject of the first page of the extended edition, implying that the Bible story starts with this event. The Tree of Jesse appears to the left of the illustration of the Birth at the centre of the page, with associated texts relating to Isaiah’s prophecy. The titulus or caption under the image of the Birth of the Virgin reads, ‘Sicut spina rosam genuit iudea Mariam’, which can be translated as ‘Just as the Judean thorn begat the rose Mary’, and that beneath the Tree of Jesse reads, ‘Sic de radice processit virgula Yesse’, ‘A rod comes thus from the root of Jesse’. A banderole that appears within the illustration carries the prophecy of Isaiah, ‘egredietur virga de radice Jesse’, and the lectione or text at the top of the page tells us that, as it is says in Isaiah 11, the Virgin is born from the root of Jesse. Meanwhile, the prophet scrolls appear to refer to texts in the Song of Solomon 6.9 and Genesis 6.14.28 The titulus under Balaam’s prophecy, to the right of the Birth of the Virgin, reads ‘Ex Jacob ista processit stellula clara’, ‘From Jacob came that bright little star’. The purpose of the Tree of Jesse illustration in the Biblia pauperum is identical to its function in the Speculum; it endorses the Davidic

Figure 1.4 Birth of the Virgin, Fifty-Page Biblia pauperum Blockbook, 1480–85

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Xylo-5, Block A

ancestry of the Virgin, thereby highlighting her role in the story of salvation, and it draws attention to her mother, Saint Anne.

Iconographic similarities between the Speculum and works of art in all media have been identified by several scholars. For example, in 1905 Mâle cited several instances where he believed prominent Netherlandish artists, such as Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, were inspired by both the Speculum and Biblia pauperum.29 In 1929, Jean Lafond discovered that a sixteenth-century Book of Hours from Rouen used for its illuminations a typological format taken directly from the Speculum.30 More direct evidence that this text influenced the use of Tree of Jesse iconography is provided by three large fourteenth-century windows, now preserved in the Temple Saint-Étienne at Mulhouse.31 These windows present a slightly modified version of the Speculum design, as each register features at its centre an episode from the life of the Virgin or scriptures, with an Old Testament prefiguration on either side. In the fourth register of the first window of the series we can see a depiction of the Birth of the Virgin, flanked by a representation of Ezekiel’s vision of the closed gate to its left, and a Tree of Jesse to its right.32

It seems that although Tree of Jesse iconography was associated with the Virgin from an early date, its use in the Speculum humanae salvationis manuscripts and subsequent blockbooks encouraged and influenced a renewed interest in the motif in certain parts of northern Europe. Its use as a prefiguration for the Birth of the Virgin was linked to a growing interest in her early life and genealogy, and its function was to establish her Davidic ancestry. This also cleared up any confusion regarding the genealogy of Christ that may have arisen from the Gospels. Although the composition of the woodcut design may not have originated with the first edition of the Speculum blockbooks, there can be little doubt that the widespread distribution of these books meant that they became a valuable source of reference, providing inspiration for donors and artists alike, contributing to the visual vocabulary of the later medieval period. The Speculum highlighted Mary’s crucial role in the story of salvation and also placed a new emphasis on the part played by her mother. It is unsurprising therefore that the Tree of Jesse also came to be used to endorse the royal paternity of Saint Anne, whose cult was to flourish from the second half of the fifteenth century.

1. Devotion to Saint Anne in the West had been almost unknown until the second half of the fourteenth century. See Henry Marriott Bannister, ‘The Introduction of the Cultus of Saint Anne into the West’, The English Historical Review, Vol. 18, No. 69 (January 1903), 107–112.

2. References within the text have indicated a Dominican author of south-west German or Swabian origin. An Italian source in the university town of Bologna has also been suggested, although this need not necessarily imply Italian authorship and there is no particular tradition for the work in Italy. For a full discussion of the authorship and early distribution of these manuscripts see Jules Lutz and Paul Perdrizet, Speculum Humanae Salvationis, Texte critique, Traduction inédite de Jean Mielot (1448), Les sources et l’influence iconographique, Tome 1 (Mulhouse: Meininger, 1907); Adrian Wilson and Joyce Lancaster Wilson, A Medieval Mirror, Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 1324–1500 (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 1984), 26–27; Bert Cardon, Manuscripts of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis in the Southern Netherlands (c.1410–1470) (Leuven: Peeters, 1996), 40–42, and Evelyn Silber, ‘The Reconstructed Toledo Speculum humanae salvationis: The Italian Connection in the Early Fourteenth Century’, The Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. XLIII (1980), 32–51.

3. Avril Henry, The Mirour of Mans Saluacioun, A Middle English Translation of Speculum Humanae Salvationis: A Critical Edition of the Fifteenth-Century Manuscript Illustrated From Der Spiegel der menschen Behältnis, Speyer, Drach, c.1475 (Aldershot: Scholar Press, 1986), 10.

4. These manuscripts are discussed in further detail by Wilson and Wilson in A Medieval Mirror, 87–88.

5. Other French translations can be found in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow (Ms. 60), the Newberry Library in Chicago (Ms. 40), the Musée Condé in Chantilly (Ms. fr.139, which carries the arms of the Flemish Le Fèvre family) and at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris (Ms. fr.188, commissioned by Louis of Bruges for his library at Gruthuyse). Bert Cardon looked at the function and meaning of the Speculum humanae salvationis at the Burgundian court between 1450 and 1470, and concluded that the manuscript was especially important in court circles. Cardon, Manuscripts of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 322–350.

6. Lutz and Perdrizet catalogued two hundred and forty-seven manuscripts, written in both Latin and the vernacular, and mentioned a further twenty-five in an appendix. See Speculum Humanae Salvationis, Tome 1. Edgar Breitenbach supplemented and amended Lutz and Perdrizet’s catalogue, adding a further seventy-nine entries, in Speculum humanae salvationis: eine typengeschichtliche untersuchung (Strassburg: J. H. E. Heitz, 1930). Evelyn Silber in her unpublished dissertation, The Early Iconography of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis: The Italian Connection in the Fourteenth Century (PhD Diss: Cambridge University, 1982), provides a list of three hundred and ninety-four surviving manuscripts.

7. Wilson and Wilson in A Medieval Mirror, 10, claim that nearly all the manuscripts are illuminated, whilst Silber in The Reconstructed Toledo Speculum humanae salvationis, 32, claims that approximately only one third are illuminated. Of the two hundred and forty-seven manuscripts catalogued by Lutz and Perdrizet, 39% were specified as having some form of illustration, 26% had none at all and 35% were not described in any detail.

8. Translation from the prologue taken from Henry, The Mirour of Mans Saluacioun, 227.

9. Song of Solomon 4:12 ‘Hortus conclusus soror mea, sponsa, hortus conclusus, fons signatus’, ‘My sister, my spouse, is a garden enclosed, a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up’. Numbers 24:17 ‘Orietur stella ex Jacob, et consurget virga de Israel:’ ‘A star shall rise out of Jacob and a sceptre shall spring up from Israel’. The text of the Golden Legend describes the angel’s annunciation of the Birth of the Virgin, first to Joachim and then to Anne. The text of the Speculum refers only to the annunciation to Joachim and, therefore, most manuscript and blockbook copies depict this event. However, there are some examples where the annunciation to Anne is shown instead, these include Brussels, Royal Library, Ms. 9332–9345, fol. 124v (1428), Paris, BnF, Ms. Latin 512, fol. 4v (1401–1500) and Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, Ms. 23, fol. 4 (c.1460). See Bert Cardon, ‘Between Flanders and France? The Speculum Humanae Salvationis, Fitzwilliam Museum Ms 23 (c.1460)’, in Fifteenth-Century Flemish Manuscripts in Cambridge Collections (Cambridge: Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 1992), 165–172.

10. ‘Stirps Jesse virgam produxit, virgaque florem, Et super hunc florem requiescit spiritus almus. V. Virgo dei genitrix virga est, flos filius eius’. See Margot E. Fassler, ‘Mary’s Nativity, Fulbert of Chartres and the Stirps Jesse: Liturgical Innovation circa 1000 and Its Afterlife’, Speculum, Vol. 75 (April 2000), 418.

11. Fassler, ‘Mary’s Nativity, Fulbert of Chartres and the Stirps Jesse’, 389–434. The Feast of Mary’s Nativity was celebrated on the 8th September.

12. A second Tree of Jesse appears on fol.16 of this manuscript, decorating the first initial of the Liber generationis for the Matins reading on Christmas Day, thereby linking the two feasts. See Robert Branner, ‘Le Premier Evangéliaire de la Sainte-Chapelle’, Revue de l’Art, Vol. 3 (1969), 37–48.

13. The Protoevangelium of James is likely to have originated in the second century and was widespread in the East, whilst it was not until the sixth or seventh century that the Gospel of Pseudo Matthew popularised the same stories in the West. The De Nativitate Mariae probably dates from the ninth century; chapters one through eight are a free adaptation of the Pseudo Matthew, whilst chapters nine through ten follow the canonical Gospels of Mathew and Luke. For further details see James Keith Elliott, ‘Mary in the Apocryphal New Testament’, in Chris Maunder ed., The Origins of the Cult of the Virgin Mary (London and New York: Burns and Oates, 2008), 57–70. Fassler suggests that belief in the idea that the evangelist Matthew wrote texts about the Virgin and that her life was directly and deliberately supported by the change in Gospel text for the Feast of Mary’s Nativity. She suggests therefore that liturgy, theology and exegesis worked together to give the Virgin’s life story legitimacy. See Fassler, ‘Mary’s Nativity, Fulbert of Chartres and the Stirps Jesse’, 397–398.

14. Jacobus de Voragine, ‘The Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary’, in The Golden Legend, Readings on the Saints (translated by William Granger Ryan), Vol. II (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1993), 149–158.

15. See Werner Williams-Krapp, ‘German and Dutch Translations of the Legenda Aurea’, in Brenda Dunn-Lardeau ed., Legenda Aurea: Sept Siècles de Diffusion, Actes du colloque international sur la Legenda aurea: texte Latin et branches vernaculaires à l’Université du Québec à Montréal, May, 1983, 227–232.

16. Voragine explains that Christ was born of the Virgin alone and that the Virgin herself was born of David through the line of Nathan, the ancestor of her father Joachim, whilst Joseph was born of David through the line of his other son, Solomon. Joseph was by birth the son of Jacob of the line of Solomon, but by law the son of Heli, of the line of Nathan, the deceased first husband of his mother. Voragine, The Golden Legend, Reading on the Saints (translated by Granger Ryan), Vol. II, 149. This does not entirely clear up the confusion created by the differing genealogies described in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.

17. Ezekiel 44:2 ‘And the Lord said to me: This gate shall be shut, it shall not be opened, and no man shall pass through it: because the Lord the God of Israel hath entered in by it, and it shall be shut’. 3 Kings 6: ‘And it came to pass in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of the reign of Solomon over Israel, in the month Zio (the same is the second month), he began to build a house to the Lord….’

18. Martin Luther, ‘Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe’, Vol. 47, (Weimar: H. Bohlau, 1883–1948), 383, ‘Bej meinem gedencken ist das gross wesen von S.Anna auffkomen, als ich ein knabe von funffzehen jharen wahr. Zuvor wuste man nichts von ihr, sondern ein bube kam und brachte S.Anna, klugs gehet sie ahn, den es gab jederman darzu’. Translation by Nixon, Mary’s Mother, 38.

19. Cornelia Schneider and Sabine Mertens eds., Blockbücher des Mittelalters, Bilderfolgen als Lektüre, Gutenberg-Museum, Exh. Cat. (Mainz: P. von Zabern, 1991), provides a catalogue of forty-five Speculum blockbooks, however, survival records can be misleading, as they do not directly reflect the original number of copies or their market.

20. Approximately thirty-six different texts and picture texts were printed in blockbook editions in the fifteenth century, and almost all of these came from the Low Countries or from southern Germany. See Paul Needham, ‘Prints in the Early Printing Shops’, in Peter Parshall ed., The Woodcut in Fifteenth-Century Europe (Washington, DC and New Haven: National Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, 2005), 46.

21. The second Latin edition was produced in c.1474 and the second Dutch edition in c.1479. Wilson and Wilson, A Medieval Mirror, 116. See also Arthur Hind, An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, With a Detailed Survey of Work Done in the Fifteenth Century (London: Constable and Company Ltd, 1935), 247, who places the Speculum blockbooks in Holland about 1470–75.

22. Mâle, Religious Art in France, The Late Middle Ages, 77–78.

23. Watson, The Early Iconography of the Tree of Jesse, 47–48, and ‘The Speculum Virginum With Special Reference to the Tree of Jesse’, Speculum, Vol. 3, No. 4 (October 1928), 445–469.

24. The origin of this type of representation is discussed further in Chapter Six.

25. These are discussed in greater detail by Wilson and Wilson, A Medieval Mirror, 207–215.

26. Needham, ‘Prints in the Early Printing Shops’, 41.

27. This text can be consulted online at http://gallica.bnf.fr. See also Wilhelm Ludwig Schreiber and Paul Heitz, Biblia pauperum, nach dem einzigen Exemplare in 50 Darstellungen (Strassburg: Heitz and Mündel, 1903). Apart from some new inscriptions or updating of clothing, there appears to have been few other changes made to the iconography of the original forty subjects.

28. Song of Solomon: 6.9 ‘Who is she that cometh forth as the morning rising, fair as the moon, bright as the sun, terrible as an army set in array? Genesis 6.14: ‘Make thee an ark of timber planks: thou shalt make little rooms in the ark, and thou shalt pitch it within and without’.

29. Émile Mâle, ‘L’art symbolique â la fin du moyen-âge’, Revue de l’art ancient et moderne, Vol. XVIII (September 1905), 195–209. This assertion was repeated in his L’art religieux de la fin du moyen-âge en France and subsequent editions. See Mâle, Religious Art in France, The Late Middle Ages, 219–230.

30. Jean Lafond, Un Livre d’Heures Rouennias, Enluminé d’Après Le Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Rouen: Imprimerie A. Laine, 1929). See also Robert Koch, ‘The Sculptures of the Church of Saint-Maurice at Vienne, the Biblia Pauperum and the Speculum Humanae Salvationis’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 32, No. 2 (June 1950), 151–155.

31. This was first identified by Lutz and Perdrizet, who also recognised links between the icono-graphic programme of the Speculum and typological glass in Alsace, at Wissembourg, Colmar and Rouffach. See Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 307–308.

32. For a more detailed description of this windows see Michel Hérold and Françoise Gatouillat eds., Lorraine et Alsace, CVMA, France 5 (Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la Recherche scientifique, 1994), 294.