PROLOGUE

11 While writing, I published a weekly column on my journey following the trail of the young Rembrandt in the daily newspaper De Volkskrant, starting on 2nd October 2018. These columns formed the building blocks for this book.

13 For the entire story of the “Rembrandt of the Third Reich” see Onno Blom, Het litteken van de dood.

15 For the appeal of Leiden’s seventeenth-century city chronicler see also Willem Otterspeer, “Orlers en ik”.

1 RHL

19 For the interpretation of The Painter in his Studio see Ernst van de Wetering, “Leidse schilders achter de ezels”, in M.L. Wurfbain et al., Geschildert tot Leyden anno 1626.

21 The registration can be found in volumen inscriptionum, 1618–1631. Archives of the Senate and faculties, inv. no. 8 (ASF8). University of Leiden.

21 Constantijn Huygens text translated by. B.J. from the Dutch translation by C.L. Heesakkers.

24 With thanks to Jonathan Bikker for the background details relating to the 1628 self-portrait.

29 Indispensable source materials for everyone researching the life and work of Rembrandt are the expensive volumes of the Corpus, which can fortunately be consulted online: http://Rembrandtdatabase.org/literature/corpus and the Remdoc website of the Radboud University of Nijmegen, Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands (KNAW) and Museum Het Rembrandthuis: http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl.

2 REMBRANDT’S NATIVE CITY

37 “Vive les gueux!” derives from the memoirs of the Catholic jurist Pontus Payen (1559–78), in Luc Panhuysen and René van Stipriaan, Ooggetuigen van de Tachtigjarige Oorlog.

43 The two best articles about fact and fiction during and after the relief of Leiden are Judith Pollmann, “Een ‘blij-eindend’ treurspel: Leiden, 1574” and Jori Zijlmans, “Pieter Adriaensz van der Werff: held van Leiden”.

3 THE MILLER’S SON

52 The first reference to Gerrit Roelofsz is in the hospital archives, Gasthuisarchief, inv. no. a302, f. 14, f. 16, 1484. Erfgoed Leiden (the new name of the city archives).

53 Permit issued to Lijsbeth Harmensdr for the building of a windmill: Secretarie Archief, sheriff Claes Adriaenszoon. Groot Privilegeboek, ff. 367–68, 23rd November 1574. Erfgoed Leiden.

53 Rembrandt’s grandmother Lijsbeth Harmensdr draws up a second will: Rechterlijk Archief, Waarboek E, inv. no. RA 67, ff. 394v–39., 8th August 1575. Erfgoed Leiden.

58 For the observation that the mill’s sails are rotating “the wrong way” I wish to thank the former city archivist (and miller’s son) P.J.M. (Piet) de Baar. See also Ernst van de Wetering, “De molen”, in Christiaan Vogelaar and Gregor J.M. Weber, Rembrandts landschappen.

4 THE CRADLE WOVEN FROM WILLOW RODS

61 Jan Jansz Orlers, “Staet ende inventaris van alle myne Goederen”, 1640. Weeskamerarchief, inv. no. 3049 g, ff. 4v.–8. Erfgoed Leiden.

62 “Rembrant Harmansz. Van Rijn van Leyden” in the notice of the intended marriage of Rembrandt and Saskia van Uylenburgh: Archief van de burgerlijke stand. Extra ordinaris intekenregister 1622–36, inv. no. DTB 765, f. 25v., 10th June 1634. Gemeentearchief Amsterdam.

63 Harmen Gerritszoon claims the cradle from the estate of Gerrit Pietersz: Getuigenisboek lo, f. 184v., 26th October 1612. Erfgoed Leiden.

66 The wedding of Rembrandt’s parents: Trouwboek (marriage register) Pieterskerk, inv. no. DTB 12, f. 61, 8th October 1589. Erfgoed Leiden.

66 The occupants of Rembrandt’s parental home during the census held to determine head tax in 1622: Secretarie Archief. Bon Noord-Rapenburg, inv. no. SA 7541, 18th October 1622. Erfgoed Leiden.

5 THE EXPLODING MUSKET

71 Kees Walle, the passionate researcher and author of the book Buurthouden, drew up for me, on the basis of the Oud Belastingboek (tax register), a list of the owners of all the houses in Rembrandt’s neighbourhood, as bounded by Galgewater, Weddesteeg, Vestwal (now Rembrandtstraat), Groenhazengracht, Rapenburg and Kort Rapenburg, which was traversed by the busy thoroughfare Noordeinde. Walle combined the information he found with the records on inns and taverns as commissioned by Jan van Hout in 1607, thus providing me with a highly accurate, detailed and lively picture of the neighbourhood.

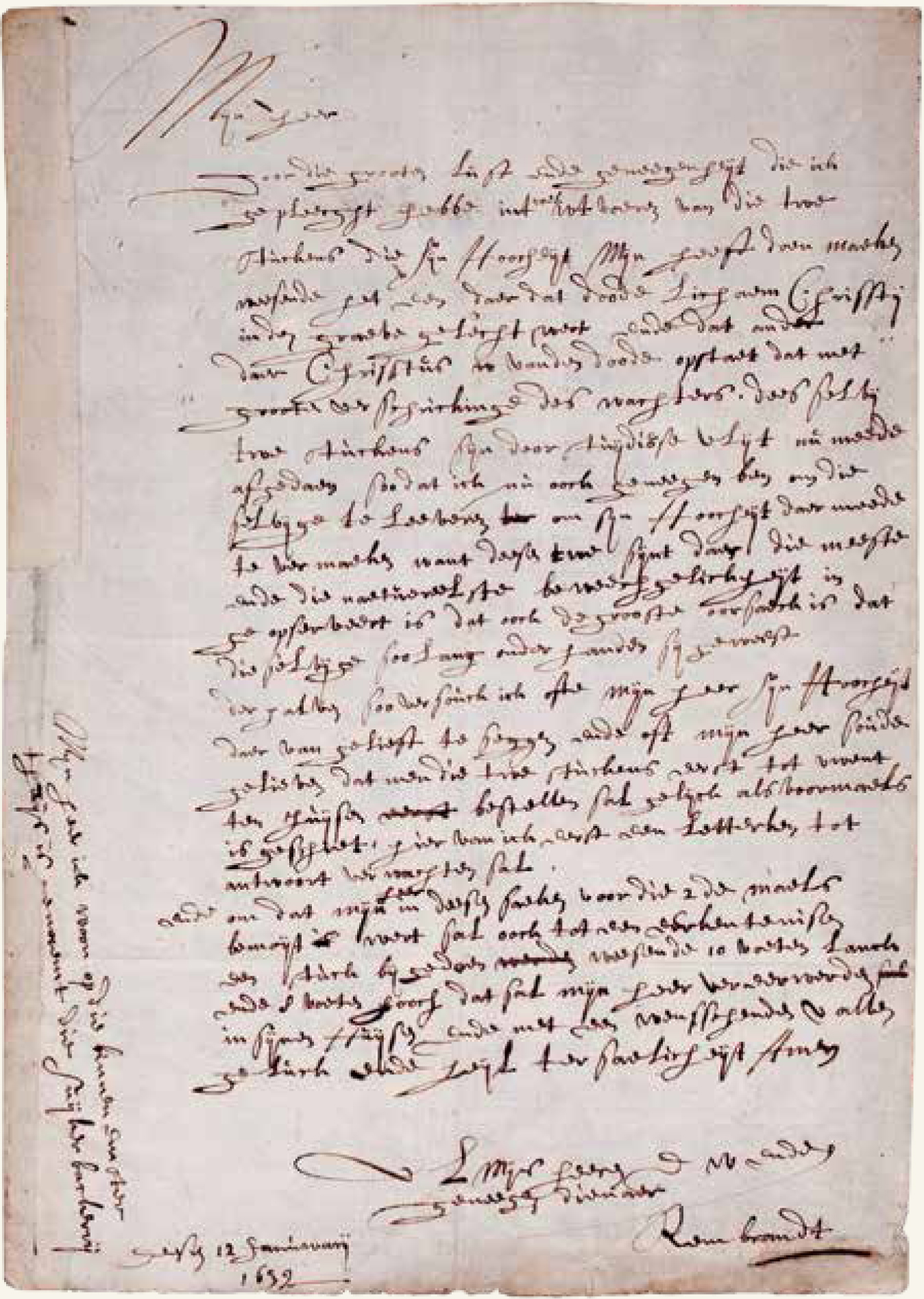

Letter from Rembrandt to Constantijn Huygens, 12th January 1639.

72 Rembrandt’s father called to testify after a brawl in ’t Sant: ONA 58, f. 233, 2nd October 1594, notary Willem Claesz van Oudevliet. Erfgoed Leiden. The Oud Belastingboek records indicate that the waggoner Harmen Willemsz himself lived on ’t Sant.

76 For the disturbance with the militiamen that took place around the entry into the city of Queen Consort Henrietta Maria and in which Rembrandt’s brother and nephew were involved see Getuignisboek W, ff. 113v.–116v., 7th June 1642. Erfgoed Leiden.

77 The information on the admission of orphans by Rembrandt’s father was first published in Kees Walle, Buurthouden and derives from AHGW, inv. no. 3386, Kinderboek 1598–1615, f. 53v. Erfgoed Leiden. (Not included in Remdoc.)

77 The chronicle of the Van Heemskerck and Van Swanenburg families was published by R.E.O. Ekkart, the biographer of Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg.

78 For the request submitted by Rembrandt’s father to be relieved of his duties in the civic guard see archives of the Schutterij, inv. no. 5, f. 53v., 22nd February 1611. Erfgoed Leiden.

79 For David Bailly’s indignation see Christiaan Vogelaar, “Schilderen en bouwen voor burgerij en stad”, Geschiedenis van Leiden, vol. 2, 2002, p. 157.

79 The information that Rembrandt erased part of Van Ruytenburgh’s shoulder was communicated to me by Ernst van de Wetering.

81 On the hasty action to draw up a will: “On this day, the sixteenth day of March in the year 1621, near the hour of 12 noon, appeared before me, Ewout Henricxz. Craen, Notary Public at the Court of Holland as nominated by the city of Leiden, the following witnesses, the honourable gentleman Harmen Gerytsz. van Rijn and the honourable lady Cornelia Willemsdr., man and wife, residing within the city of Leiden and known to me as notary, the aforesaid Harmen Gerytsz. van den Rijn being in good health and the aforesaid Cornelia Willemsdr. being in poor health and bedridden.” Oud Notarieel Archief, access no. xiii. Notary Ewout Hendricxz Craen. Originals of notarized deeds, 1611–27: 1621 I, ONA 137, f. 56, 16th March 1621. Erfgoed Leiden.

81 Harmen was relieved of his obligation to pay six guilders a year to the civic guard after his son Adriaen enlisted in his place: archives of the Schutterij, inv. no. 5, f. 132v., 2nd May 1617. Erfgoed Leiden.

83 The grave of Adriaen Harmensz van Rijn: Grafboek (register of graves) Pieterskerk 1647, f. 160, 25th September 1645. Erfgoed Leiden.

6 THE NEW CITY

85 With thanks to Jeremy Bangs, also for his hospitality in the delightful Leiden American Pilgrim Museum in Beschuitsteeg, which gives you the sense of entering Rembrandt’s own home.

85 With thanks to Leo Lucassen for his illuminating observations on immigration in Leiden in the seventeenth century.

88 See also Leids woordenboek at www.dickwortel.nl.

91 Blok, P.J., “Rembrandt en zijn tijd”.

93 For the negotiations between Rembrandt’s father and the city council on the tax to be paid see inv. no. 4346, f. 57. Erfgoed Leiden.

7 BEHIND MINERVA’S SHIELD

96 The most important source of information on the Latin school is the book by my former headmaster, A.M. Coebergh van den Braak, Meer dan zes eeuwen Leids gymnasium.

97 For the education provided to Leiden’s youngest children see D. Stremmelaar, “Spelen en leren in Leiden rond 1600”.

99 The description of the duties to be carried out by Lettingius is quoted by Ingrid Moerman in “Leiden: de stad en haar bewoners in Rembrandts tijd”, in Roelof van Straten, Rembrandts Leidse tijd, p. 282.

100 On the inventory of items possessed by Schrevelius in Haarlem see Oud Notarieel Archief Haarlem, ONA 163, f. 68v.

100 The Buchelius quotation is as follows: “Molitoris etiam Leidensis filius magni fit, sed ante tempus”, in G.J. Hoogewerff and J.Q. van Regteren Altena, “Arnoldus Buchelius: Res pictoriae,” p. 67.

100 The discovery of the name of the drawing master Rieverdinck: J.G. van Gelder, “Rembrandts vroegste ontwikkeling”, p. 273, note 2.

101 The quotation from Ovid’s Metamorphoses is from A.S. Kline’s translation, published online.

101 My attention was drawn to the use of Claudian by Amy Golhany in Rembrandt’s Reading.

8 THE HAND OF GOD

105 The entry in the volumen inscriptionum was found by Jef Schaeps and Mart van Duijn, curators of Leiden University Library. I am extremely grateful to them for notifying me of their discovery before it was publicized. See also Jef Schaeps and Mart van Duijn, Rembrandt en de Universiteit Leiden.

106 For a scintillating picture of the earliest history of the University of Leiden see Willem Otterspeer, Groepsportret met dame: De Leidse universiteit, vol. 1.

109 The comments on Scaliger and the Dutch translation (translated into English here by B.J.) of his satirical poem are taken from H.J. de Jonge, “Josephus Scaliger in Leiden”.

110 On the library, publishers and printers see A. Bouwman, B. Dongelmans, P. Hoftijzer et al., Stad van boeken: Handschrift en druk in Leiden 1260–2000.

112 On Clusius see Kasper van Ommen, The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526–1609.

116 For Rembrandt’s household inventory see Desolate Boedelkamer (Bankruptcy Office), Register van Inventarissen B, inv. no. DBK 364, ff. 29r.–38v. Stadsarchief Amsterdam.

119 The passage on the anatomy theatre includes a quotation from J.J. Orlers, Beschrijvinge der Stadt Leyden.

120 The visitor to Rembrandt’s studio was Pieter van Brederode. Bibliotheek van de Hoge Raad van Adel. Quartieren, Helmteekens en Genealogie, f. 7, 2nd October 1669.

9 THE ARMINIAN REDOUBT

131 The popular anecdote that Prince Maurits wondered aloud whether predestination was “green or blue” is a charming fiction. Nonetheless, it serves to indicate that predestination was a highly complex issue and that Maurits had no head for abstract ideas.

135 For the entry in the diary of Johannes Wtenbogaert see Memorieen J. Wtenbogaert 1624–1633: Dagelijkse aantekeningen in den Comptoir Almanak van het jaar 1629–1634, inv. no. Ms. Sem. Rem., f. 43, 13th April 1633. Leiden University Library.

137 For the words that Scriverius is said to have uttered to the bailiff see Geeraert Brandt, Historie van de Regtspleging, pp. 76–86.

138 The skirmishes that took place outside the Knotter family home were discovered and described by Bas Dudok van Heel in his splendid PhD dissertation “De jonge Rembrandt onder tijdgenoten”, pp. 29–31.

10 THE GHOST OF LUCAS

141 For the interpretation of Lucas’s Last Judgement I am indebted to Christiaan Vogelaar, with whom I have made many visits to the triptych over the past few years.

142 For the history of The Last Judgement see also Rick Vos, Lucas van Leyden.

142 For the quotation on Lucas see Dominicus Lampsonius, Pictorum aliquot celebrium Germaniae Inferioris.

11 LITTLE NAPLES ON LANGEBRUG

147 For the information on Master Nicolai—as he is called by J.J. Orlers—see the fine catalogue produced by R.E.O. Ekkart, Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg 1537–1614: Leids schilder en burgemeester.

149 Quotations from the family chronicle: R.E.O. Ekkart, “Familiekroniek Van Heemskerck en Van Swanenburg”.

150 For the information on Langebrug and the Penshal (tripe hall) I would like to thank Piet de Baar, who checked Master Jacob’s address for me: Langebrug 89. According to the 1622 census drawn up to determine head tax, the following people lived in the Zevenhuizen neighbourhood (f. 2v.) in October or November: Jacob Isacxz van Swanenburch, painter, Margrieta Cardon, his wife, Marijtgen, Silvester, Isack, Jacop’s children, and Jannetgen Aryensdr, maidservant.

154 Ernst van de Wetering drew my attention to the “tablet”. For detailed background information see Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt: The Painter at Work.

156 When I was nearing the end of my Master’s programme in 1994, I had the good fortune to spend three months at the Istituto Olandese in Rome. Every day I followed the trail of famous Dutch painters and writers as I moved around the Eternal City. Every day I entered the San Luigi dei Francesi, the French church between Piazza Navona and the Pantheon. In the cool darkness I went to the Contarelli chapel and put a 500-lire coin in the meter. The lights clicked on and I gazed open-mouthed at the sweet angel whispering its words of inspiration to the old Evangelist Matthew.

157 One copy has been preserved in the Netherlands of the cookery book by Antonius Magirus, Koock-boeck oft familieren keuken-boeck (Antwerp, 1655). It is in the Special Collections, University of Amsterdam.

12 INNOCENCE SLAIN

161 Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee was stolen in the early morning of 18th March 1990 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The thieves, disguised as police officers, knocked out the guards and stole thirteen masterpieces valued at a total of 500 million US dollars, including a Vermeer, a Degas, a Flinck and three Rembrandts. The painting was never found. The heiress Gardner stipulated in her will that the interior of her house, which became the museum that bears her name, was to be left unchanged. That is why we find today, exactly twenty-nine years after the biggest art robbery of all time, the frame from which the thieves cut Christ in the Storm still hanging in its old place on the wall: an empty space, as flat as a Dutch polder.

162 For the facts on the life of Lastman see Astrid Tümpel and Peter Schatborn, Pieter Lastman: Leermeester van Rembrandt.

164 On the charming angel see also Henk van Os, Rembrandts offer van Abraham in de Hermitage.

170 On all the interpretations that have been advanced down to the present day, right up to this book’s publication, Gary Schwartz wrote the illuminating article “Putting ourselves and Rembrandt to the test”, op www.garyschwartzarthistorian.nl.

172 See also Piet Calis, Vondel. Het verhaal van zijn leven.

175 With thanks to Jan Six for telling me his story of the discovery and for giving me an opportunity to spend a few hours in the company of Rembrandt’s painting. Thanks also to Ernst van de Wetering for his account of the painting’s authenticity. See also Onno Blom, “Kunsthandelaar Jan Six ontdekt wéér een ‘nieuwe’ Rembrandt”.

13 TWO NOBLE YOUNG PAINTERS OF LEIDEN

180 With thanks to Piet de Baar for the data on the houses of the fathers of Rembrandt and Jan Lievens respectively. Roelof van Straten, Rembrandts Leidse tijd 1606–1632, a treasure trove of reliable information, contains the minor error that the Lievens family moved to Noordeinde while Rembrandt was living in Leiden. See Waarboek II, f. 252 in the archives of Erfgoed Leiden: Pieterskerk-Choorsteeg 15, north section, named De Rosencrans, a newly built huysinge, was officially transferred on 16th July 1608 by Aernt Cornelisz, a baker in Den Draeck, for 2,100 guilders, in addition to an annual payment of 31 guilders 50, to Lieven Henricxz filius Joos, who sold it on 31st July 1634 to the unmarried person Annetgen Jacobsz Visscher for 3,100 guilders (Waarboek III, f. 170).

183 The quest for the shared studio has always kept the minds of the people of Leiden occupied. A building at Muskadelsteeg number 5 was long believed to be the location. The alley derives its name from the fact that a liquor store and tavern in the alley sold, among other things, sweet wine made from muscatel grapes. In the early seventeenth century, one Trijntje Harmensdochter lived there; this must have been one of Rembrandt Harmenszoon’s sisters. The popular author Jan Mens wrote a novel entitled Meester Rembrandt (1946) in which the painter moves in with his friend and rival Jan Lievens. In the later 1980s, the then director of De Lakenhal, M.L. Wurfbain, and Ernst van de Wetering of the Rembrandt Research Project together went to see if the seventeenth-century front room corresponded to Rembrandt’s The Painter in his Studio (c.1628). Sadly, they soon noted that the wide floorboards in the painting did not run in the same direction as in the historical front room in Muskadelsteeg. Yet this did not break the spell for the students who lived in that building. They set a memorial tablet in the façade: “Here lived and worked / Rembrandt van Rhijn 1622–1624.” Years later, after fierce protests by the historian Ingrid Moerman and Piet de Baar, Leiden’s burgomaster ordered the tablet’s removal. Rembrandt’s father’s name was certainly Harmen, but did he have a sister called Trijntje? As it happened, he did not. The tablet was completely wrong. On the shared studio see also Ernst van de Wetering, “De symbiose van Lievens en Rembrandt”.

190 For the report and the analysis of the painting competition see Ernst van de Wetering, “Leidse schilders achter de ezels”, in M.L. Wurfbain et al., Geschildert tot Leyden anno 1626.

193 With thanks to the eminent scholars Frans Blom (no relation) and Ad Leerintveld, who took me to Hofwijck, the country estate of Constantijn Huygens in Voorburg. That same day, in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library) in The Hague, we pored over Huygens’s original manuscript. On a cushion lay the thick bound volume. We opened the book in the manner of high priests handling the Holy Scriptures and leafed through until we came to the five densely inscribed pages. Our index fingers moved across the rough seventeenth-century paper, line by line. We read sections in Latin, then the Dutch translation by C.L. Heesakkers, and were astonished. Nowhere did the secretary’s even hand betray the slightest hint of emotion, but he wrote with such eloquence. His words ring out, silver-toned. Bravo Huygens!

14 THE FIRST HERETIC IN THE ART OF PAINTING

205 I have based my retelling of Houbraken’s anecdotes on the version by Jan Konst and Manfred Sellink (1995).

209 With thanks to Peter Zuur who took me to the attic of the Leiden art society Ars Aemula Naturae for a demonstration of the technique of etching. It is a magical place: Willem van Mieris, Frans van Mieris’s son, who was in turn the best pupil of Rembrandt’s best Leiden pupil Gerrit Dou, established the first art academy in the country on that spot in 1694. Despite the clarity of Peter Zuur’s explanation of the technique, it remained a mystery—even to him—that no one has ever succeeded in improving upon Rembrandt’s bizarre method of etching. Sheer sorcery.

The grave of Rembrandt’s parents, number 60, central section of the nave of the Pieterskerk in Leiden.

216 Gary Schwartz on “antedating” in Rembrandt: Zijn leven, zijn schilderijen, p. 84.

222 Rembrandt’s letter of 12th January 1639 to Constantijn Huygens contained a section that may be translated as follows: “Sir, it has been with great delight and affection that I have executed the two paintings that his Highness commissioned from me, viz. one depicting the dead body of Christ being laid in the grave and the other showing Christ rising from the dead to the great terror of the guards. These same two paintings have now been completed, partly as a result of studious diligence, so that I am now ready to deliver them to your Highness for your enjoyment, since in these two I have pursued the most natural moving quality, which is the primary reason why I have had them in hand for so long.” Collection of the Royal Archives, The Hague.

15 EYES SHUT

225 The archives of the late Robert Oomes, a huge trolley containing many boxes of paper, are still waiting to be opened and explored in the storage facility of Erfgoed Leiden. Oomes spent years researching the numbering and names of the graves. In the course of his research, in 2009, he identified the precise location of the grave of Jan van Hout in the Pieterskerk. With the aid of his numbered floor plan of the church we can find the locations of grave numbers 60 and 71: we find them in the church’s burial book (Grafboek Pieterskerk) for 1610, ff. 72v. and 73v, Erfgoed Leiden. Without the assistance of Kees Walle and Piet de Baar I would have found the transcription and interpretation of these documents an impossible task. The burial books also show that the church—probably because the graves of Harmen and grandfather Cornelis were beneath the pulpit—moved them both on 26th September 1645 to grave number 101 in the central section of the nave. That is where Adriaen Harmenszoon van Rijn, who died on 19th October 1652, was laid to rest.

227 The authenticity of the drawing and the inscription has at times been challenged. Peter Schatborn, who has been the leading authority on Rembrandt’s drawings for decades, has assured me that there is no need to harbour any doubt that this is a genuine Rembrandt.

228 The portrait of Rembrandt’s father in the inventory of the estate of Sybout van Caerdecamp: Oud Notarieel Archief, no. LXI. Willem Pietersz van Leeuwen, ONA 785, f. 13, 23rd February 1644. Erfgoed Leiden.

229 Rembrandt’s etching plates in Clement de Jonghe’s shop: Notarieel Archief, no. 186. Johannes Backer, NA 4528. Stadsarchief Amsterdam.

229 For Gary Schwartz’s comments on the portrait of the old woman see De grote Rembrandt, p. 48.

236 “Een tronitgen van warmbrant”: Huydecoper family archives, inv. no. 30, f. 5v. Utrechts Archief.

236 For Jouderville see also Ernst van de Wetering, “Isaac Jouderville. A pupil of Rembrandt”, in Albert Blankert et al., The Impact of a Genius: Rembrandt, His Pupils and Followers in the Seventeenth Century.

237 For the notes on Marten Soolmans see also Jonathan Bikker, Marten en Oopjen.

237 Jonathan Bikker was the first to publish an account of the brawl witnessed by Soolmans. The original document is to be found in Notarieel Archief, Pieter den Oosterlingh, f. 10, akte 115, 19th March 1630. Erfgoed Leiden. With thanks to Piet de Baar for the transcription.

238 For the tontine see ONA 425, akte 26, 8th/24th March 1631, notary Karel Outerman. Erfgoed Leiden. With thanks to Kees Walle for the transcription, including the complete list of subscribers. For the statement attesting to Rembrandt’s good health see Notary Jacob van Zwieten, inv. no. Notarieel Archief 861, ff. 244v.–245r., pp. 488–89, 26th July 1632. Stadsarchief Amsterdam. With thanks to the curator, Eric Schmitz, for showing me and transcribing the original. In the margin of the notary’s records (notarisboek) is a red cross, placed there by the person who discovered the document: Abraham Bredius, the renowned Rembrandt researcher and one-time director of the Mauritshuis.

240 With thanks to Jan Six for identifying the breed of the dog at Rembrandt’s feet.

241 That the dissection took place at the Weighhouse (De Waag) is an educated guess. It is impossible to prove, but highly likely. See also Ernest Kurpershoek, De Waag op de Nieuwmarkt, pp. 42–64.

243 The first piece of research to discover the background details of this case was conducted by I.H. van Eeghen: “De anatomische lessen van Rembrandt”. Kees Walle transcribed for me the vast quantity of documents on Ariskindt. Those drawn from the Gemeentearchief Amsterdam were as follows: Confessieboek inv. no. 295, pp. 136–7, 16th November 1623; Confessieboek inv. no. 297, p. 35, 27th November 1625; Confessieboek inv. no. 297, pp. 66v.–67, 10th March 1626; Confessieboek inv. no. 299, pp. 31v.–32, 4th December 1631; Confessieboek inv. no. 299, pp. 37–38, 12 December 1631; Confessieboek inv. no. 299, p. 48, 24th January 1632. Crimineel Vonnisboek 1629–33, pp. 158–62, 31st January 1632.

The documents drawn from Erfgoed Leiden were: ORA, Crimineel Vonnisboek 10, f. 251v., 23rd July 1624; ORA, Crimineel Vonnisboek 11, ff. 47, 47v. and 48, 22nd August 1625; ORA, Crimineel Vonnisboek 11, ff. 72, 72v. and 73, 24th October 1625; ORA, Crimineel Vonnisboek 11, ff. 85, 85v., 86 and 86v., 19th/26th January 1626.