Neanderthals of the forest steppe

The Early Middle Palaeolithic, ~325–180 ka BP

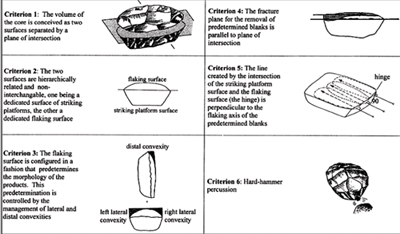

Archaeologically, the Early Middle Palaeolithic (EMP) is most readily differentiated from the Lower Palaeolithic by the widespread and persistent use of Levallois technology often, but not invariably, accompanied by the disappearance of handaxes and an increase in flake tools (papers in Ronen 1982; Gamble and Roebroeks 1999). Although instances of much earlier Levallois technology are documented (see below) these are rather precocious flourishes that do not constitute a lasting shift in technological practices, but rather random or situational convergences on Levallois from a common Acheulean root (White and Ashton 2003; White et al. 2011). Furthermore, they exist among a typically Lower Palaeolithic suite of behaviours, whereas the persistent change that occurred ~330 ka BP was accompanied by changes in other hominin adaptive, social and cognitive structures (White and Ashton 2003; Gamble 1999), discussed below.

Sites assigned in this book to the EMP span the period from late MIS9 to late MIS7, and provide evidence for hominin occupation of Britain during two previously unrecognised interglacial periods between the Hoxnian (MIS11) and the Ipswichian (MIS5e), namely the Purfleet (MIS9) and Aveley (MIS7) interglacials. As discussed by Scott (2010) and White et al. (in prep.), for most of the twentieth century the compressed chronological frameworks available actually left little time for a discrete EMP, which was instead compacted into a handaxe-rich late Lower Palaeolithic with Levallois as a technological option (e.g. Wymer 1968; Roe 1981). In this account, the Middle Palaeolithic was restricted to a handful of Upper Pleistocene occurrences, discussed in the next chapter. Because of a strong tradition of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary Quaternary studies, there are now a relatively large number of sites in the British terrestrial record that be firmly attributed to this newly defined period on a number of lithostratigraphical (Bridgland 1994; Schreve et al. 2002, in press), biostratigraphical (Schreve 1997, 2001a and b; Keen 1999) and chronostratographical (Penkman 2005; Briant et al. 2006) grounds. Here we accept these attributions, and will not repeat the long debates regarding the ages of the various deposits concerned (e.g. Bridgland 1994; Gibbard 1985, 1994; Schreve 1997, 2001a and b; Schreve et al. 2002; Schreve et al. 2006; Candy and Schreve 2007).

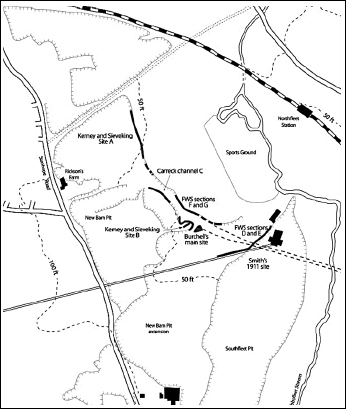

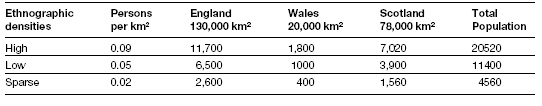

This chapter presents the first general synthesis of environments, landscapes and archaeology of EMP Britain. It concentrates on a number of key sites (Figure 5.1) that have been attributed on non-typological grounds to late MIS9–7, setting them in their environmental and landscape context, and subsequently discusses their significance for an understanding of Neanderthal technical organisation, settlement history, societies and demography.

Major British sites discussed in Chapter 5.

The termination of MIS 9 and the climatic deterioration marking the onset of the MIS8 glaciation began ~300 ka BP (Figures 5.2 and 5.3). On the basis of the global oxygen record, MIS8 appears to have been less severe than most other Middle Pleistocene glaciations, being similar in magnitude to MIS4; although at ~50,000 years duration it lasted much longer. Two distinct warm peaks are evident, with a significant warming event towards the latter end of the glaciation related to an increase in insolation (Toucanne et al. 2009). Unlike MIS12 and MIS2, terrestrial evidence for an extensive lowland glaciation during MIS8 has been elusive; according to Kukla (2005) high levels of solar radiation in northern latitudes from late MIS9 prevented the formation of extensive ice sheets. However, recent work in eastern England has provided evidence for ice sheets advancing at least as far as Lincolnshire (T. White et al. 2010), while offshore boreholes have established MIS8 deposits well into the Southern Bight of the North Sea (Beets et al. 2005).

The warming limb initiating MIS7 began about ~245 ka BP, but was interrupted by a brief (c. 2 ka) reversion to colder conditions (Desprat et al. 2006). Thereafter, the climatic structure of the MIS7 interglacial shows that it was characterised by at least three warm peaks of more or less equal magnitude and duration (MIS7e, 7c and 7a) and two climatic deteriorations (7d and 7b) (Bassinot et al. 1994; Candy and Schreve 2007), refining previous studies where only two warm peaks and a single cold episode were emphasised (e.g. Zazo 1999). As such, the development of the British landscape, and changes throughout the interglacial, are now seen as far more complex than previously thought, with major implications for hominin colonisation, settlement and behaviour.

The Marine Isotope Curve from MIS1 to MIS21, with the period covered in this chapter highlighted. (Data from Bassinot et al. 1994.)

Key features of Marine Isotope Stages 8, 7 and 6. (After Scott and Ashton 2010 and courtesy Beccy Scott.)

Abrupt climatic deterioration began c. 180,000 years ago, marking the start of MIS6, with MIS7 therefore lasting some 60 ka years. There is evidence of an equally abrupt return to warm conditions in MIS6.5, possibly of equal magnitude to MIS7a. The remainder of the period, however, was extremely cold, with British and Scandinavian ice sheets extending into and blocking the northern North Sea (Toucanne et al. 2009).

Waelbroeck et al. (2002) derived relative sea level (RSL) estimates based on high resolution δ18O records – combined with evidence of high sea-level stands based on corals and low sea-level stands from salinity records (Rohling et al. 1998) – to reconstruct a composite RSL estimate for the past four climatic cycles, with an estimated error margin of +/−13 m (Figure 5.4). During MIS8 RSL was depressed by as much as 110 m, creating terrestrial conditions in both the Channel and North Sea. Three high sea-level stands were detected in MIS7, corresponding to the warm sub-stages 7e (c. −10 m OD), 7c (ca −5 m OD) and 7a (ca −11 m OD), but during none of these did RSL quite reach modern levels.

Sea level estimates from the benthic isotope record and other sea-level indicators, with periods during which Britain was an island during MIS7 and MIS5 indicated. Top dashed line: modern sea-level. Lower dashed line: −40m below modern sea-level, above which Britain is assumed to become an island. Shaded area: periods of high sea level and island status as described in this chapter. (Reconstructions based on data from A: Waelbroeck et al. 2002, based on North Atlantic and equatorial Pacific benthonic isotopic record; B: Lea et al 2002, based on foraminiferal Mg/Ca and planktonic oxygen isotopes; C: Shackleton 2000, based oxygen isotope data from equatorial Pacific (V19–30) and Vostock air oxygen isotope ratio; D: Siddall et al. (2003), based on Red Sea salinity and oxygen isotope record; E: Cutler et al. 2003, based on scaled data from benthic isotope record of core V19–30.)

Waelbroeck et al. (2002) note that their results largely agree with estimates from corals and geochemical data on submerged speleothems from Argentorola Cave, Italy (Gallup et al. 1994; Bard et al. 1996, 2000), although more recent work on these speleothems have indicated that sea level in MIS7a was actually much lower, probably reaching no higher than −18 m OD (Dutton et al 2009a and b). These are similar to the estimates derived from Shackleton’s (2000) δ18O data, which project generally lower sea levels for all MIS7 warm peaks. On the other hand, estimates by Lea et al. (2002) using planktonic Mg/Ca and δ18O found even higher sea levels, with MIS7e and MIS7a possibly exceeding both modern and MIS5e RSL.

For the cold sub-stages of MIS7d and MIS7b, most estimates produced the expected reduction in sea levels, but again there are some discrepancies. Waelbroeck et al.’s (2002) results show that, during MIS7d, RSL plummeted to c. −85 m OD, but MIS7b showed only a marginal fall to c. −25 m OD, some 35 m higher than projections derived from Shackleton’s data. Interestingly, the Italian speleothem data, Shackleton’s δ18O reconstructions, Red Sea salinity (Siddall et al. 2003) and coral dating (Thompson and Goldstein 2005) all show a period of high RSL during the early part of MIS6 (MIS 6.5), when levels appear to have risen to <-19m OD, although the combined RSL data show lower levels well below ~-50m OD.

Despite inconsistent and contradictory reconstructions, it would still appear that sufficiently high sea levels existed for Britain to become an island during the warmer phases of MIS7, although it would have been a peninsula during periods of depressed sea levels in MIS8 and probably MIS7d. As noted in Chapter 3, Keen (1995) suggested that past sea levels at or above modern ordnance datum would have been sufficient to separate Britain from Europe, given the present critical depths of c. −50 m in the Dover Strait and −40 m in the North Sea; although he acknowledged the confounding problems of not knowing the Middle Pleistocene bathymetry of these basins, the absence of any telltale deposits and the fact that the North Sea is progressively downwarping and was probably shallower in the past.

There are a number of deposits along the coast from Essex to Cornwall (and also along the opposite French coast) that provide direct evidence for marine transgression and an open Dover Strait during MIS7. Where fossils are preserved, these generally show deposition during warm phases, although some preserve far-travelled cobbles and boulders that may be ice-rafted erratics emplaced during cold periods with high sea levels (Bates et al. 2000, 2003).

Extensive evidence for marine conditions during MIS7 has come from the Norton– Brighton Raised Beach on the Lower Coastal Plain at Sussex (Bates et al. 1997; Bates 1998; Bates et al. 2000, 2003). Relict beach deposits at Black Rock, Brighton, consisting of flint and chalk cobbles and pebbles with a base height of 8.5 m OD, have yielded AAR estimates consistent with an MIS7 correlation (Davies 1984). These are overlain by 20–25 m of ‘coombe rock’ (a rubbly, chalky solifluct) yielding a mammalian fauna similar to those from cold-climate deposits immediately predating the last interglacial (MIS5e) deposits at Marsworth, Buckinghamshire (Murton et al. 2001), and Bacon Hole, Gower (Stringer et al. 1986), and presumed to represent MIS6.

The Norton–Brighton Raised Beach has been extensively investigated at Norton Farm, where marine sands and gravels have been recorded between 5 and 9 m OD (Bates et al. 2000). Age estimation based on AAR, lateral correlation with other dated raised beach deposits, as well as the presence of both a small caballine horse and specific M1 morphology in northern voles, all suggest that the site belongs to late MIS7/early MIS6 (Bates et al. 2000; Bowen et al. 1989; Parfitt 1998b). Ostracods and foraminifera from Norton Farm revealed a marine regression, with fully marine conditions being replaced by intertidal mudflats, the foraminifera becoming stressed and reduced in size as tidal links receded to zero (Bates et al. 2000). Overall the invertebrate faunas showed a mixture of cold and warm species, perhaps suggesting that more continental conditions prevailed; the sparse pollen record also indicates an essentially open environment. The whole sequence was suggested to represent a high sea level event during deteriorating cold conditions (Figure 5.5), followed by a full marine regression at the MIS7/6 boundary (or conceivably a transition between one of the warm-cold sub-stages, or even MIS6.5). Similar evidence for cool-cold water conditions and high sea levels was noted on the other side of the channel, at Tancarville and Tourville (Bates et al. 2003).

The palaeogeography of eastern England during MIS7. (After Bates et al. 2003 and Wiley, with permission.)

Further Raised Beach deposits at West Beach, Portland Bill, Dorset, lying at 10.5 m OD (Davies and Keen 1985), and at Hope’s Nose, Torbay at 9–12 m OD (Davies 1984; Bowen et al. 1986) have also been correlated with MIS7 based on AAR estimates. Similar age estimates have been obtained from the sea caves at Berry Head (Figure 5.6), Torbay, from both AAR (Mottershead et al. 1987) and Uranium-series dates of 210 + 34/−76 ka BP and 226 + 53/−76 ka BP (Proctor and Smart 1991; Baker and Proctor 1996) on speleothem formed in regressive phases that seal intertidal brown loams. The molluscan faunas from these Devon and Dorset raised beaches, in contrast to Norton Farm, testify to warm sea temperatures similar to those of today and must, therefore, belong to different and probably earlier parts of the interglacial. Other sites with evidence for early interglacial marine conditions come from Selsey Life Boat Station (LBS), where brackish molluscs appear at −1.76 m OD, heralding a full marine transgression with deposits up to 7.5 m OD (West and Sparks 1960). As discussed below, the Selsey sequence probably represents the earliest part of MIS7.

The westernmost evidence comes from raised beaches of the Godrevy Formation in West Cornwall, which has produced TL and AAR estimations of both MIS7 and MIS5e age (Scourse 1999). At Fistral Bay, raised dunes attributed to both MIS7 and MIS5e show different prevailing wind directions, with MIS7 being dominated by northerly winds but MIS5e by southeasterlies. This may indicate very different climates during MIS5e and whatever part of MIS7 is represented here. Scourse tentatively suggested that the northerly winds may represent changing wind direction at the beginning of a cold stage. The Godrevy formation also contains non-local clasts within a muddy matrix, which Scourse (ibid.) suggests represent erratics deposited by ice floes during high sea-level stands during a cold period.

Raised beaches and sea caves in the Torbay area. Top: Raised beach at Shoalstone. Bottom: Berry Head. (Photographs courtesy Chris Proctor.)

A few sites within the Mucking Formation of the Thames (Bridgland 1994) also reveal high sea levels in the North Sea. At Aveley, brackish water molluscs and ostracods have been noted in the Lower Brickearth, suggesting a marine transgression during this early part of the interglacial (Allen and Robinson, cited in Sutcliffe 1995; Cooper 1972; Holyoak 1983). Similarly fine-grained, laminated sediments from Lion Tramway cutting, West Thurrock, have also been interpreted as representing intertidal or estuarine conditions (Schreve et al. 2006 see Text Box 5.1).

LION PIT TRAMWAY CUTTING, WEST THURROCK, ESSEX

First discovered by A.S. Kennard in the early twentieth century (Dibley and Kennard 1916), the Lion Pit Tramway Cutting preserves a primary context Levallois knapping floor, potentially one of the most important MIS7 sites in Britain. However, although the site has been recently reinvestigated (Bridgland 1994; Bridgland and Harding 1995; Schreve et al. 2006), an area of only 5.25 m2 was excavated, the narrow cutting within which the deposits are exposed (first cut to remove Chalk from the Lion Pit via a double track) and the sheer depth of sediment overlying the archaeology severely limiting the scale of any investigation.

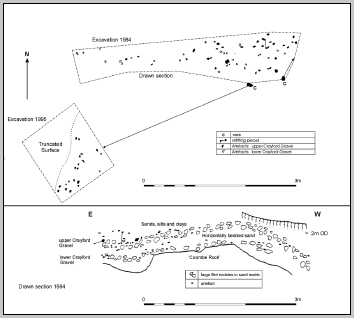

Excavation plan and geological section through the archaeological levels exposed in the recent excavations at the Lion Tramway Cutting, West Thurrock. (After Schreve et al. 2007.)

Levallois cores from the Lion Tramway Cutting, showing two different operational schema. (Top: lineal centripetal; bottom: recurrent unipolar.)

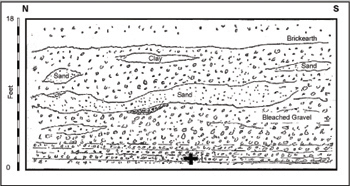

The Pleistocene deposits exposed in the Lion Pit Tramway Cutting form part of the Taplow/Mucking Formation of the Thames; the basal ‘Crayford Gravel’ dating to the MIS8–7 transition immediately following downcutting to this terrace level. The sequence rests on chalk breccia containing sparse flints, with the main archaeological horizon occurring just above this, in the upper division of the coarse Crayford Gravel. These are overlain by c. 10m of fine-grained sediments, including fossiliferous sands and silty clay, and laminated beds of possible estuarine origin.

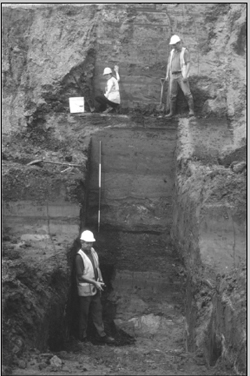

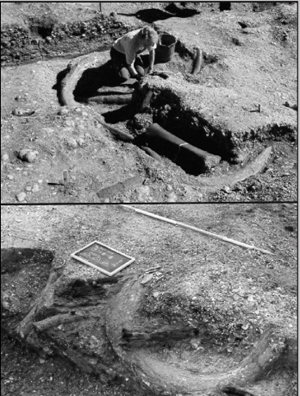

Photograph of the 1984 excavations at the Lion Tramway Cutting, showing the depth of sands and silts overlying the Levallois knapping floor. John McNabb provides a human scale. (Courtesy of David Bridgland.)

Molluscan and mammalian remains from the silts and clays above the archaeological horizon – including Corbicula fluminalis, Bithynia tentaculata, Palaeoloxodon antiquus (straight-tusked elephant) and Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Merck’s rhinoceros) – attest to deposition in a slow-flowing river under wooded, fully temperate conditions, although the majority of the mammalian fauna favour open-grassland, which presumably occurred on the Thames floodplain (Schreve et al. 2006). Pollen from the site also revealed a wooded environment dominated by alder, hornbeam and hazel with lower frequencies of pine, oak, lime and ash (Hollin 1977). Samples from another exposure 0.9 km west of the Tramway Cutting showed two pollen biozones, the lower (correlated with pollen from the Tramway itself) being dominated by thermophilous woodland taxa, the upper showing the spread of local grassland (Gibbard 1994). No artefacts have been recovered from these beds, but human presence is attested by a cut-marked pelvis of a narrow-nosed rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus), with incisions concentrated around the obdurator foramen, an area where butchery and detachment of muscle blocks leaves these characteristic traces (Schreve et al. 2006).

The ‘Levallois floor’ occurs on a gravel ‘beach’ at the foot of a chalk river-cliff, both of which provided raw material for knapping activities. Including both recently excavated material and the earlier collections made by Warren (Warren 1923a and b), this site has produced some 250 artefacts, including Levallois cores, Levallois flakes and a range of associated débitage. Large flint nodules from the gravel and chalk cliff were used to execute full Levallois reduction sequences, from raw material acquisition, though preparation, exploitation and discard of the cores and waste flakes on the river beach, to the export of selected blanks for use elsewhere. How far the knapping floor extends laterally is unknown, but given the richness of the small area so far investigated a major spread seems likely. The relatively undisturbed nature of the site is demonstrated by refitting, although some vertical displacement has occurred and, despite sieving, finer débitage is underrepresented, presumably winnowed out (Schreve et al. 2006). Environmental indicators directly associated with the Levallois floor are practically non-existent but given the geological context a cool climate and fairly open conditions probably prevailed during the MIS8–7 transition.

In summary, as the climate ameliorated into early MIS7, rising sea levels led to a marine transgression. Data from the French side of the Channel, along with evidence from oceanographic and sedimentological source patterns, suggest an open Dover Strait during MIS7, and we can track evidence of high sea levels around the south coast from Cornwall to Essex. It would therefore seem extremely probable that Britain was cut off from Continental Europe during these periods, and that both hominin and animal populations were isolated or, if absent, perhaps faced insurmountable cognitive or technical barriers to seaborne dispersal (White and Schreve 2000). Furthermore, while the evidence from Portland Bill and Torbay show that high sea levels existed during fully temperate conditions, Norton Farm indicates the continuation of such conditions into a cold period. Whether this is the onset of MIS6, or one of the cold sub stages of MIS7, is currently unclear (Bates et al. 2003). This distinction is very important for understanding the movement of animals in and out of Britain for, although it is widely assumed that during cold sub-stages Britain may have been reconnected to Europe, the evidence presented above hints that this may not have always been the case. This may have significant implications for the EMP settlement history of Britain (White and Schreve 2000; Ashton and Lewis 2002; White et al. 2006).

The environments and environmental history of the EMP associated with MIS7 can be reconstructed at different scales through several proxies, including pollen, plant macrofossils and the dietary or habitat requirements of contemporary animals. MIS8 occupation is evident at a number of sites, notably Purfleet and Baker’s Hole, but beyond sedimentological evidence for deposition under cold condition and cold-tolerant species such as mammoth and horse (which also occur in the proceeding interglacial) little can be said. Very few good palaeoenvironmental records exist for MIS7 and even fewer can be directly related to significant archaeological assemblages. As such, we cannot associate EMP hominins within a particular type of habitat, although the fact that most significant archaeological sites occur in similar fluvial settings allows the assumption that hominins were active in the same types of landscapes and habitats. This section will therefore describe the landscapes available for hominin exploitation during MIS7, had they been present or left visible traces, and provides for the first time a synthetic overview of the environmental history of the period (cf. Murton et al. 2001).

Good evidence for the vegetation of MIS7 comes from pollen and plant macrofossils from just a handful of published sites: Aveley, Essex (West 1969), Marsworth, Buckinghamshire (Murton et al. 2001), Stoke Goldington, Bedfordshire (Green et al. 1996) and Selsey LBS, Sussex (West and Sparks 1960), each of which preserves evidence for vegetation development throughout parts of MIS7. This can be augmented by data from some very habitat and diet specific beetles. The majority of plants found in MIS7 sites still occur in southern Britain today, suggesting the existence of some analogous plant communities and implying an MIS7 environment very similar to the present day (Murton et al. 2001), even if populated by an exotic suite of animals and not controlled by modern land management practices.

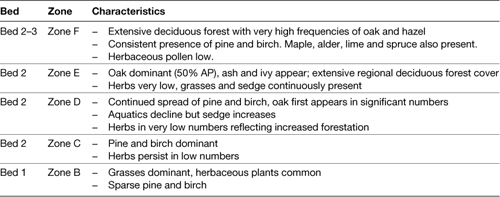

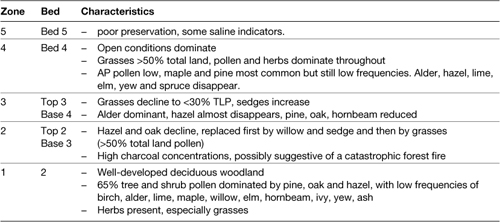

At the Selsey LBS site, Sussex, West and Sparks (1960) described a succession of freshwater silts (Bed 1), detrital muds (Bed 2) and estuarine clays (Bed 3), filling a channel incised into Eocene Bracklesham Beds. Pollen and plant macrofossils were recovered from all major stratigraphical units and were divided into several zones showing successive vegetation change over time (Table 5.1). The site also produced a sparse archaeological assemblage from the detrital muds of Bed 2, including a Levallois core (Nick Ashton pers. comm.).

The pollen from the basal Freshwater Beds (Table 5.1) was characterised by high frequencies of non-arboreal pollen, dominated by grasses, sedges and other herbaceous plants. Other than birch and pine, tree pollen was sparse, with sporadic records of lime, oak, and hornbeam. West postulated that the thermophilous tree species were derived from older Pleistocene deposits, and that much of the pine pollen was probably far travelled, although macroscopic remains of several birch species unequivocally demonstrates that trees were present. The regional vegetation at this time was thus dominated by open grassland with some isolated stands of trees and shrubs. West suggested that this was a flora typical of Zone B of the Ipswichian (i.e. MIS5e) and, although this attribution is not accepted here, the notion that this flora represents the earlier part of an inter-glacial may still be valid. However, there is no evidence that this period was particularly cold. No arctic or subarctic plants were present and while the majority of the macrofossils are today distributed throughout Scandinavia, some have a more southerly distribution (West and Sparks 1960, 104). High frequencies of Typha latifolia, which is not found beyond the 14 °C isotherm, also suggest mild conditions and rapid warming.

Table 5.1 Summary of the pollen evidence from Selsey LBS (after West and Sparks 1960).

The pollen spectra contained within the deposits of Bed 2 (the organic muds) and Bed 3 (grey silty-clay with evidence of incipient salinity) were divided by West into a further four Zones (C–F). These showed progressive forestation, and a concomitant decline in herbaceous species; by the end of the sequence regional forest cover was extensive (see Table 5.1). Thermophilous terrestrial plants such as ivy (Hedera helix), dogwood (Cornus sanguinea), and aquatic species including Eurasian water nymph (Najas minor) and soft hornwort (Ceratophyllum cf. submersum) also show warm summer conditions. Seeds of frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae), water-soldier (Stratiotes aloides) and duckweeds (Lemna), plants which rarely or never fruit in Britain today, may indicate higher summer temperatures than at present during Zone F (West and Sparks 1960, 113), while firethorn is presently a native of southern Europe. The high frequencies of hazel and the presence of holly (Ilex) and ivy suggest some degree of oceanicity, as the latter two in particular are frost-sensitive and will not tolerate average winter temperatures below 1.5 ºC. The climate during Zones E and F was therefore one with warm winters and warm summers.

The pollen profiles from Marsworth (Figure 5.7) and Aveley reveal an entirely different succession. At the old Bulbourne Quarry, Marsworth (SP933143, now College Lake Wildlife Centre), botanical remains have been recovered from the fluvial sands and organic muds filling the Lower Channel, and from tufa clasts within these (Green et al. 1984; Murton et al. 2001). The latter represent the fragmented remains of deposits laid down in an earlier calcareous spring at this location; uranium-series dating of tufa clasts gave age estimates ranging from 254,000–208,000 ka BP, suggesting that the tufa was originally emplaced during MIS7e–c, and that the temperate conditions of the Lower Channel deposits represent MIS7a (cf. Candy and Schreve 2007).

Pollen Profile from the Lower Channel Deposits at Marsworth. (After Murton et al. 2001 and Elsevier, reproduced with permission.)

Pollen from the tufa showed high frequencies of ash and pine with lesser quantities of oak, birch, elm, lime, alder and hornbeam. Leaf impressions of willow, hazel, maple, and rowan were also present. A local environment covered in temperate woodland similar to that found on the limestones of southern England today was inferred, although open ground herbs and high frequencies of grass pollen indicated that open grassland existed in areas away from the tufa spring (Murton et al. 2001). This may have been maintained by the contemporary herbivores who may even have been responsible for breaking up the tufa (ibid.).

In contrast, the botanical remains from the organic muds of the Lower Channel deposits were characterised by low quantities of tree and shrub pollen (<10%) but a dominance of open herbaceous taxa. Low frequencies of trees and shrub pollen (including alder, oak, elm, poplar, lime, hornbeam, hazel and juniper) were argued to represent individual or small clumps of trees and tall shrubs growing on the channel sides, existing in an otherwise open landscape dominated by grasses, sedge, and other common herbaceous plants. Nothing in the pollen indicated that the climate was significantly warmer or colder than today, except in the uppermost sample from the ‘coombe rock’ above the channel. This deposit, the formation of which is often triggered by cold conditions, contained sparse fossils of species characteristic of montane habitats in northern Europe today.

The picture provided by the Aveley pollen profile (see Text Box 5.2) conforms to that seen at Marsworth (West 1969; Bridgland et al. 1995). West (1969) divided the Aveley pollen profile into two major zones of an interglacial:

1 Early Temperate/Zone IIb, from the clays and silts of Bed 21 and the lower part of the Detritus Muds of Bed 3 (associated with the remains of straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus). This zone was dominated by pine, oak and hazel, with low frequencies of other tree taxa. Towards the end, the frequency of hazel falls as lime, hornbeam and spruce rise, accompanied by an increase in open ground pollen.

2 Late Temperate/Zone III, from the top of the Detritus Muds of Bed 3 and the mammoth area within Bed 3. This zone saw the continued fall in arboreal pollen with communities becoming more open. Oak and hazel decline significantly while hornbeam assumes dominance and pine continues to be well represented. Birch, alder and spruce also increase in significance.

SANDY LANE QUARRY AND PURFLEET ROAD, AVELEY, ESSEX

The site of Aveley was instrumental in the recognition of the MIS7 interglacial in the terrestrial record (Schreve 2001b and references therein). First discovered in 1964, the fossiliferous temperate deposits at Aveley, along with those at Trafalgar Square and Ilford, were originally assigned to the Ipswichian (MIS5e) interglacial on the basis of its pollen record (West 1969; Mitchell et al. 1973; Hollin 1977). Aveley and Ilford, however, are situated at a higher terrace level than Trafalgar Square and contain different mammalian assemblages. This led Sutcliffe (1975) to question the notion that all these sites were of the same age and he concluded that, while the Trafalgar Square deposits were genuinely Ipswichian, the Aveley and Ilford deposits belonged to an older, post-Hoxnian, pre-Ipswichian temperate period (i.e. MIS7). This has since been supported by Bridgland’s Thames terrace model (Bridgland 1994 and see main text) which places Aveley within the third (Mucking/Taplow) post-Anglian terrace formation, as does a range of biostratigraphic schema (Schreve 2001b; Keen 2001; Coope 2001) and aminostratigraphy (Bowen et al. 1989; Schreve et al. 2006). By contrast, the pollen signatures from the Ipswichian and MIS7 interglacials cannot, as yet, be separated.

Schematic section through the Mucking formation deposits at Sandy Lane, Aveley. (After White et al. 2006, modified after Bridgland 1994.)

Photo of 1997–8 investigations at Aveley. (Courtesy of David Bridgland.)

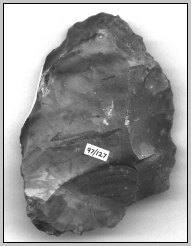

Levallois core from Aveley. (Photo Mark White.)

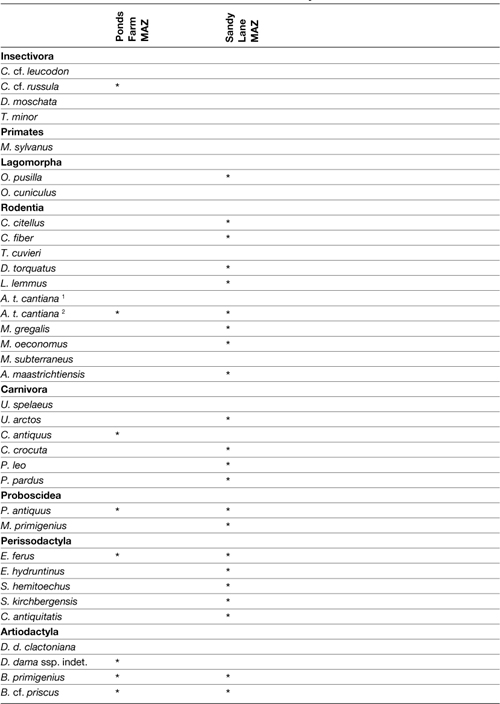

The sediments at Aveley record a complex climatic signal with at least two temperate episodes separated by breaks in deposition. As noted in the main text, the mammalian faunas from the upper (Bed 2) and lower units at Aveley both represent fully temperate conditions but differ substantially in composition and environmental range. The Ponds Farm MAZ belongs to the older part of the sequence and is characterised by temperate woodland species such as straight-tusked elephant and fallow deer, alongside obligate thermophiles such as European pond terrapin (Emys orbicularis) and white-toothed shrew (Crocidura cf. russula) (Schreve 2001a and b). Molluscs from this part of the sequence indicate a slow-flowing, well-oxygenated river with water depths of 1–5m but also some areas of shallower water with a muddy substrate and surrounding marshland (D. Keen, pers. comm.). The proximity of more open grassland conditions is indicated by the presence of horse and bison. The Sandy Lane MAZ belongs to the later part of the sequence, and is separated from the Ponds Farm MAZ by a depositional hiatus. It is characterised by a reduction in woodland-favouring forms and an increase in herds of large grazers including a late form of steppe mammoth and horse; fallow deer is a notable absentee. The pollen evidence from Sandy Lane (West 1969) also records an opening up of the environment at this time, recording the transition from woodland to grassland in this part of the sequence; this is also in accord with the molluscan and beetle evidence.

The faunal turnover between the Ponds Farm and Sandy Lane MAZs may provide evidence for a marine regression. Slightly brackish molluscs in the upper silts testify to high sea levels during this period of deposition but a period low sea levels, presumably during a cold sub-stage marked by the deposition hiatus between the two MAZs, must have prevailed to allow this influx of new species from mainland north-west Europe. The timing of the suggested reconnection has previously been proposed as sub-stage 7d of the marine isotope record (Schreve 2001b), when increased global ice volume probably lowered sea level enough to rejoin Britain to mainland Europe, although new uranium-series dating from the correlative site at Marsworth has also suggested sub-stage 7b (Candy and Schreve 2007: see Text Box 5.3).

Until recently, Aveley had produced no evidence of human occupation but in 1996 salvage excavations at Purfleet Road during the upgrading of the A13 dual-carriageway (Schreve et al. in prep.) produced five flakes from the lower part of the Aveley sequence (Ponds Farm MAZ), while a further three flakes and a Levallois core were found in the upper part of the Aveley sequence (Sandy Lane MAZ). Although a very small collection, these artefacts are nonetheless valuable in helping to show hominin presence during both the early and later parts of this interglacial in association with different environmental regimes.

More recent work by Bridgland et al. (1995, 212–215) detected five pollen zones at Aveley (Table 5.2) which, despite some specific differences in representation and seriation, again shows a transition from an essentially wooded to an open landscape over time. Blezard (1966) proposed a considerable hiatus between the lower and upper parts of the sequence and more recent work (Schreve et al. in prep.) has indicated that Bed 3 contains two organic horizons separated by a minerogenic sequence. As such, the Aveley deposits may contain a punctuated rather than gradual change in vegetation. Schreve et al. (ibid.) argue that this implies two warm phases separated by a cold phase that is poorly represented in the pollen record although there is little in the pollen that shows either an initial cooling or subsequent warming to support this. A similar transition from wooded to open conditions has been described at West Thurrock (Gibbard 1994).

Table 5.2 Pollen zones from Aveley (after Bridgland et al. 1995).

The data summarised above provides three short snippets through different sub-stages of the MIS7 interglacial from which it is possible to make some tentative statements about the overall vegetation history of the period. On the basis of flora, fauna and sedimentology, the deposits at Selsey LBS, as well as the nearby site at West Wittering, have been assigned by several workers to the earliest part of an interglacial, previously MIS5e but now generally accepted as representing the earlier part of MIS7 (Parfitt 1998b; Preece et al. 1990; West and Sparks 1960). The data, not unexpectedly, show a familiar pattern of vegetation development after a glaciation, commencing with open grassland conditions and a relict cool fauna, which progressively gave way to extensive dense woodland vegetation and associated faunas, presumably MI7e. This period coincides with a marine transgression. The tufa samples from Marsworth have provided Uranium-series dates that suggest correlation of the woodland phases of MIS7 with sub-stages 7e and 7c. By extrapolation this would date the later open temperate conditions inferred from the pollen in the organic muds of the Lower Channel at Marsworth to MIS7a, with the cold-stage deposits above marking the onset of MIS6 (Candy and Schreve 2007). The long sequence from Aveley, which shows the same transition from wooded to open conditions and a similar faunal change, is believed to span the same period (Candy and Schreve 2007; Schreve 2001b). In summary, at a regional scale the interglacial began and closed with open phases, the middle largely dominated by dense coniferous and deciduous woodland during temperate interstadials.

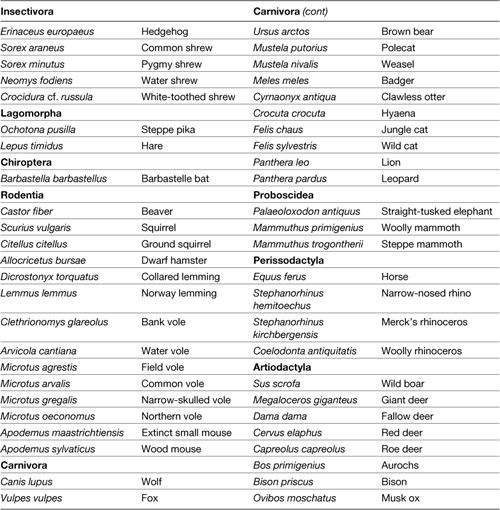

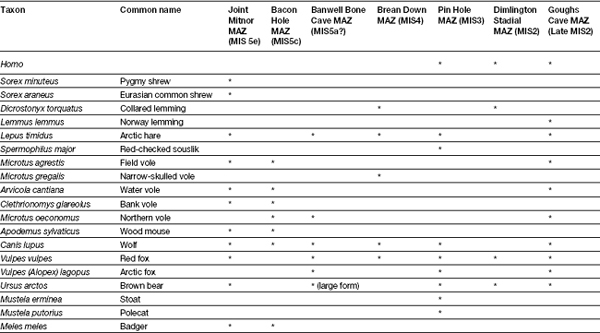

Unlike pollen, fossil vertebrates and invertebrates that once populated these MIS7 grasslands and woodlands are preserved at a relatively large number of sites. Table 5.3 presents the 49 species of mammal currently known to have been present in Britain during MIS7. As for all other Pleistocene periods, the MIS7 mammalian community was far richer in megafauna than today, providing a wide range of potential prey for hominins, with abundant herds of large herbivores existing in the open river valleys and beyond. Early Neanderthal occupants would also have faced stiff competition from the carnivore guild, which included lion, wolf, leopard and hyaena; some of these species, along with the bear, may also have been sitting tenants in the few desirable caves available in Britain.

Table 5.3 Mammalian fauna of MIS7 Britain (data from Schreve 1997; Parfitt 1998a; Wenban-Smith 1995).

The species list in Table 5.3 has been derived from some 30 stratigraphic horizons from 22 archaeological and palaeontological sites. Regardless of where they fall within the period they show a range of ecological and climatic preferences and most sites show a range of local environments. However, based on abundance (measured as either number of identified specimens (NISP) or minimum number of individuals (MNI)) the majority of sites show a dominance of animals adapted to open grassland habitats. The most common taxa are horse, woolly mammoth, the smaller ‘Ilford-type mammoth’ (now believed to be a form of Mammuthus trogontherii, the steppe mammoth; Lister and Sher 2001; Scott 2007), bison, narrow-nosed rhinoceros, woolly rhinoceros and giant deer, all open-dwelling grazers or grazers/browsers that required large quantities of daily forage. A suite of small mammals with similar grassland or shrubland associations is also evident, most notably the northern vole, field vole, hedgehog, hare, steppe pika, common shrew, lemming and ground squirrel. Of the carnivores, lion and hyaena are also predominantly open grassland predators, as is the jungle cat, which today hunts small mammals and waterbirds in marshy and grassland habitats (Schreve 1997; 2001b). Red fox and weasel are able to exploit a wide range of habitats, depending on the presence of small prey, while the red deer can adapt its feeding behaviour and rumen to suit its environment (Lister 2004; Stewart 2005), and all are thus not good indicators of habitat.

Contemporary with these predominantly open landscape species occurs a smaller woodland element, suggesting that the wider landscape was a mosaic of open/closed habitats, familiar from many Pleistocene localities (Gamble 1995a). Typical large woodland indicators include bear, straight-tusked elephant, Merck’s rhinoceros, wild boar, roe deer and fallow deer, while among small mammals badger, beaver, woodmouse, white-toothed shrew and squirrel have similar associations; the polecat also favours forested locations today (Schreve 1997). Several species are also dependant on slow-running fresh water, such as water vole and beaver, perhaps unsurprising given the predominantly fluvial contexts from which they were recovered.

While most MIS7 assemblages are dominated by open-dwelling species, a small number of assemblages have higher frequencies of woodland animals, the most important being that from Bed 4 at Aveley (Schreve 1997). This observation formed the basis for the two MIS7 mammalian assemblage zones (MAZ) defined by Schreve (1997, 2001a and b): the Ponds Farm MAZ and the Sandy Lane MAZ (Table 5.4; see Text Box 5.3). The Ponds Farm MAZ is dominated by species representing heavily wooded environments such as straight-tusked elephant and white-toothed shrew and is argued to belong to earlier MIS7. The presence of Emys orbicularis (European pond terrapin), which requires average summer temperatures of 18 °C to hatch its eggs, indicates summer temperatures hotter than today. In contrast, the Sandy Lane MAZ is dominated by open-dwelling species such as steppe mammoth, narrow-nosed rhinoceros and horse, and is argued to belong to late MIS7. Schreve (2001b) tentatively suggests that an unconformity in the lower sands and silts at Aveley may indicate a further subdivision of the Ponds Farm MAZ.

Table 5.4 The characteristic faunas of the Ponds Farm and Sandy Lane MAZs

THE BIOSTRATIGRAPHY OF MIS7

MIS7 comprised three warm events (7e, 7c and 7a), interrupted by two cold substages (7d and 7b). Although well established in the marine isotope record, MIS7 has only recently been recognised as a distinct and valid interglacial in the terrestrial record. Key marker species include the ‘Ilford-type’ mammoth, the freshwater clam Corbicula fluminalis (which is absent from all later interglacials; Keen 1990) and the beetle Oxyletus gibbulus (which occurs in large numbers only during MIS7; Coope 2001). No formal attempt has yet been made to provide a pollen zonation for the period. Attempts have been made, however, to construct a finer resolution (sub-Milankovitch level) chronology for MIS7 using mammalian biostratigraphy.

Schreve (2001b) was initially undecided which MIS7 sub-stages her Ponds Farm and Sandy Lane MAZs represented (Table 5.4) but argued that the observed faunal turnover was probably climatically driven, with reduced sea levels required to allow the incursion of a new suite of animals from the continent. Such an event must have occurred during a cold sub-stage, either 7d or 7b. More recent work on the dating of tufa deposits from the Lower Channel at Marsworth has allowed some refinement of this observation (Candy and Schreve 2007). The brecciated tufa from the Lower Channel produced two clusters of dates, ~254 to 234 ka BP (correlated with MIS7e) and ~219 to 208 ka BP (correlated with MIS7c), suggesting two distinct phases of tufa development, separated by a cold event (MIS7d) during which deposition ceased. The youngest date for the tufa, ~208 ka BP, implied that the fossiliferous Lower Channel fill itself post-dates MIS7c and being fully interglacial and open in character it was assigned to MIS7a (ibid.). Drawing on these dates and their subdivisions of the Aveley fossil material, Candy and Schreve (2007) concluded that the wooded phase represented by the Ponds Farm MAZ belonged to both MIS7e and MIS7c and the open phase signalled by the Sandy Lane MAZ to MIS7a. This would place the climatic deterioration that reconnected Britain to Europe in MIS7b.

One difficulty here is that 7b was less severe than 7d, and sea levels may have fallen to only 25 m bmsl. At these sea levels, Britain is likely to have remained an island. Further complications with the mammalian biostratigraphy arise when the vegetation history is considered. The wooded conditions apparent from the flora at Selsey LBS (as well as West Thurrock (Gibbard 1994) and Stutton (West and Sparks 1960)) seems to suggest that the animals from these sites are placed in one or more of the forested phases, probably MIS7e and/or MIS7c. However, Schreve (1997; Candy and Schreve 2007) assigned the faunas from each of these sites to the Sandy Lane MAZ. The apparent contradiction at West Thurrock and Stutton could be explained by the fact that the flora and fauna from these sites is not firmly associated and might relate to different parts of the interglacial but Selsey LBS cannot be explained in these terms.

The floral sequence at Selsey LBS shows open conditions giving way increasingly to forested habitats, while the mammals of Bed 1, which included the steppe (Ilford-type) mammoth and narrow-nosed rhinoceros along with some cold indicators such as lemming, give way to a fully temperate fauna including straight-tusked elephant in Bed 2 (Parfitt 1998b).

It is therefore difficult to see how Selsey LBS could equate with MIS7a as it shows the reverse of the pattern expected by Candy and Schreve. Even if one were to suggest that the open conditions and marine transgression at this site represent rising sea levels and vegetation developments following the cold conditions of MIS7b (White et al. 2006), no heavily forested phase should be expected to follow. An alternative explanation, following the argument for Marsworth, could be that Selsey LBS represents forest recovery in MIS7c after the colder conditions of MIS7d, but again this period is associated with the Ponds Farm MAZ, meaning that mammoth and narrow-nosed rhinoceros should not occur, only straight-tusked elephant (see Table 5.4). Other sites along the Sussex coast, at East Wittering and West Street, both near Selsey (Parfitt 1998b, 135), produced a faunal suite similar to the Sandy Lane MAZ, which Parfitt placed in a later phase of the same interglacial seen at Selsey LBS, when a mosaic of open and forested conditions prevailed.

Another exception is the site of Strensham which Schreve (1997) assigned to the later part of MIS7 (i.e. MIS7a) due to the presence of mammoth. In contrast, Bridgland et al. (2004) argued that it lies on the earlier of two MIS7 terraces in the Severn–Avon system, the later part of MIS7 being represented by the terrace at Ailstone.

A more complex situation can be proposed:

1 An early phase with a suite of open-dwelling species in which mammoth is the only elephant (of Ilford-type according to Schreve’s 1997 analysis).

2 A subsequent, more wooded, phase characterised by straight-tusked elephant and other forest specialists.

3 A late phase characterised by a mosaic of predominantly open landscapes with significant woodland and a mixed fauna dominated by mammoth (by this time possibly only Mammuthus primigenius, see Scott 2007) and including straight-tusked elephant.

Much more data is required to test this proposed sequence. But, at sites with only a single biozone (most of them), the problems discussed above mean that the fauna (and archaeology) could feasibly date to several parts of the interglacial. Exactly where many of the other ‘late MIS7’ sites (e.g., Ilford, Stanton Harcourt, Stoke Goldington) actually fit within the sequence must therefore now be considered open to question, with no independent or unequivocal means of determining whether they are late, early or even middle MIS7. As such, we would

Sampling biases complicate this picture. In some cases faunal variation may simply represent localised vegetation structure. Context is key when reconstructing environments on the basis of animal frequency: if we were to interpret sites at face value it would be easy to infer that the majority of MIS7 mammals operated close to water in open environments. But it is necessary to remember that some large ‘keystone’ herbivores probably helped create and maintain their own open habitats (such as elephant), and that the predominance of fluvial or lacustrine contexts in MIS7 sites (in Schreve’s 1997 study 20/26) probably indicates the greater preservational potential of these settings rather than the clustering of animals solely in these locales. Large tracts of woodland may have existed not far from these open valleys, the lower proportions of woodland animals in the record a reflection of the frequency with which they entered these open habitats or other preservational basins, not the relative proportion of regional woodland cover at any given point in time.

A hint that this might be the case comes from the caves of the south-west of England, such as Bleadon Cave and Oreston Cave, which show micro-habitat variation and a complex vegetation mosaic. Within these caves, wild boar occurs in relatively high frequencies alongside other woodland species such as roe deer and open environment indicators. Outside the caves, however, not a single example of wild boar has been found (Schreve 1997). This presumably reveals the presence of dense forest on top of Mendip and the limestone hills of Plymouth (ibid.). Were it not for the preservation of wild boar and roe deer in these caves – which, after all, they were not actually living in – we would not see this forested element of the landscape. Carnivores, which always occur at much lower densities than their prey (Guthrie 1990) and who are thus less likely to die and be preserved in significant number at fluvial sites, are also best represented in the cave sites of south-west England where they probably denned and weaned their young (NISP data from Schreve 1997 shows that 84% of wolf remains, 96% of hyaena remains and 82% of lion remains come from just three sites). The presence of leopard at only Bleadon and Pontnewydd caves (see Text Box 5.4) similarly reflects the rarity of this animal and its fondness for cave localities, while the absence of hominin fossils from the archaeological record might equally reflect their rarity in the landscape and position on the trophic pyramid. Scott (2007) has made similar observations regarding the absence of rhinoceroses from central England, suggesting that this either represents a difference in regional habitat, or a different phase within MIS7 for these sites.

PONTNEWYDD CAVE, CLWYD, NORTH WALES

Pontnewydd Cave is situated in Carboniferous limestone in the Elwy Valley about 50 m above the modern river. The first recorded excavations were by William Boyd Dawkins, the Rev. D. Thomas and Mrs Williams-Wynn in the 1870s (Dawkins 1874, 1880; Hughes and Thomas 1874) although by this time a substantial amount of deposit had already been removed. Between 1978 and 1996 systematic excavations were undertaken at the cave by Stephen Green which confirmed the stratigraphic sequence described by previous workers (see Table 1). This demonstrated that the cave system preserves a fragmentary record of infilling and erosion spanning at least 300 ka, and amassed significant collections of artefacts, fauna and 23 human teeth, comprising 4–7 individuals showing Neanderthal affinities (papers in Green 1984; Aldhouse-Green 1995).

View of the entrance to Pontnewydd Cave.

(© National Museums and Galleries Wales.)

Hard stone bifaces from the Early Middle Palaeolithic of Pontnewydd Cave.

(© National Museums and Galleries Wales.)

Table 1 Stratigraphic sequence at Pontnewydd (after Green 1984; Aldhouse-Green 1995)

Bed |

Interpretation |

| Laminated travertine | Calcareous precipitate |

| Upper clays and sands | Fluvial |

| Upper Breccia | Debris flow, dated to ~35–25 ka BP, containing derived artefacts and fauna |

| Silt | Fluvial, dated to >25 ka BP |

| Stalagmite | In situ precipitate, dated to ~220–80 ka BP |

| Lower Breccia | Debris flow, dated to >220 ka BP, containing artefacts, fauna and Neanderthal remains |

| Intermediate Beds | Debris flow, containing artefacts, fauna and a Neanderthal tooth |

| Upper sands and gravel | Debris flow, dated to >245 ka BP |

| Lower sands and gravels | Debris flow and fluvial sediments, dated to >245 ka BP |

The site has produced over 600 artefacts, including handaxes, scrapers, Levallois pieces and a number of discoidal cores that may represent recurrent centripetal Levallois technology (Aldhouse-Green 1995, 1998). The artefacts are predominantly made from local volcanic raw materials with a few from sandstone and flint. The volcanics are noted as being difficult to work, a fact reflected in the crude, pointed nature of the handaxes and the ‘inept’ Levallois technique found at the site (Newcomer 1984; Aldhouse-Green 1988, 1995). The majority of the artefacts (and the human remains) come from the Lower Breccia with a smaller number originating from the Intermediate Beds. Both are allochthonous debris flow deposits. Consequently, the artefacts are thought to have originated outside the cave and show damage consistent with exposure in a cold climate prior to their introduction. Aldhouse-Green (1995) suggested that the cave – which is large enough to comfortably hold 6–12 people – may have been incidental to the human occupation, most of which occurred outside. However, the range of activities inferred from the artefacts suggest that it was more than just a transitory camp. Traces of butchery have also been noted on remains of horse and bear from the Lower Breccia (Aldhouse-Green 1995) and the presence of burnt flint hints at the erstwhile presence of hearths.

Thermoluminesence and Uranium-series dating programmes provided a minimum age estimate of ∼220 ka BP for the Lower Breccia (Aldhouse-Green 1995). This is in agreement with the MIS7 attribution for the mammalian fauna from this bed which contains a mixture of open/closed and warm/cold adapted species – including lemming, horse, narrow-nosed rhinoceros, beaver and roe deer – probably representing different cold and warm sub-stages (Aldhouse-Green 1995; Schreve 1997). The fauna from the underlying Intermediate Beds is dominated by temperate woodland elements, potentially reflecting an earlier wooded phase of the same interglacial. Dates for the deposits in the ‘New Entrance’, which produced >100 artefacts, suggest that this phase of occupation took place ∼175 ka BP, at the close of MIS7, although the dates range from ∼225–175 ka BP and overlap at 2σ with estimates from the Main Entrance. The artefacts show a range of similar types but differ in frequency of representation. Given their secondary context, it is probably unwise to read too much into this. In sum, the occupation may predate the ages of all the deposits by several millennia, and may have spread across several warm and cold events throughout MIS7.

Another notable element of the MIS7 fauna is the mixture of ostensibly warm and cold-adapted animals in the same assemblage, for example woolly rhinoceros and red deer at Ilford, or more famously temperate molluscs (Corbicula fluminalis) and red deer alongside musk ox and lemming at Crayford (see Text Box 5.5). There are several possible explanations. It may be entirely taphonomic, with elements of cold (sub-)stage and warm (sub-) stage faunas mixed in the same deposit. It may be a collection issue, with poor recording leaving animals that actually belonged to different contexts of very different ages and depositional environments now combined into a single collection (a particular problem at Crayford and Baker’s Hole). Indeed, Scott (2007) has argued that the association of woolly rhinoceros with an otherwise warm fauna reflects stratigraphical uncertainties, and cannot be seen as indicating the beginning of MIS6 as suggested by Stuart (1976). She further argues that only the smaller ‘Ilford-type mammoth’ was actually present in MIS7, with the woolly mammoth not arriving until very late in the interglacial, or even early in MIS6, as indicated by recent dating programmes (Lister et al. 2005). For Scott (2007, 129), claims of woolly mammoth earlier in the interglacial are based on misidentifications. This would certainly help explain the paradox of such a classic cold climate indicator living in a warm temperate environment, although others see the MIS7 faunas as representing genuine communities and not taphonomic jumbles; Schreve (1997, 2001b) suggests the mixture highlights a more continental regime – with warm summers but much colder winters than at present – and a significant seasonal turnover in migratory species.

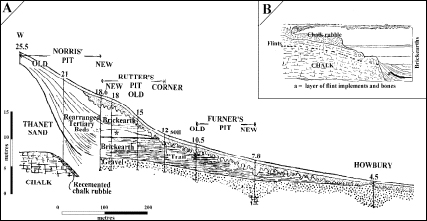

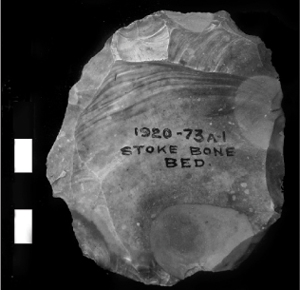

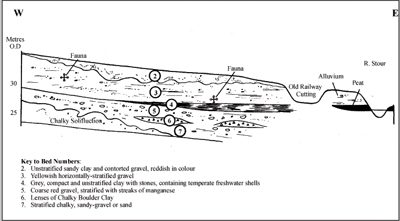

THE CRAYFORD BRICKEARTHS (STONEHAM’S PIT, NORRIS’S PIT, RUTTER’S PITS, FURNER’S PITS, SLADE GREEN)

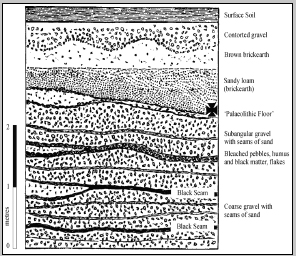

The deposits once exposed in a number of pits at Crayford and Erith potentially hold a valuable key to our understanding of the EMP occupation of Britain. The deposits rest on Chalk/Thanet Sand with the basic sequence comprising a basal gravel overlain by brickearth and capped with ‘trail’. The brickearth is subdivided into a lower fluviatile and an upper colluvial component separated by the highly fossiliferous Corbicula Bed. They have been assigned to the Taplow/Mucking Formation, correlated with OIS8–7–6 (Bridgland 1994), an attribution supported by an AAR ratio on Bithynia (Bowen et al. 1989). Precisely where they belong within this long period is a contentious yet important issue. Currant (1986a) and Sutcliffe (1995) preferred an OIS6 age because several cold-climate species are present, including lemming and musk-ox. Bridgland, however, suggested the main archaeological horizons were of late OIS8/early OIS7 age, with the sparser higher occurrences showing persistent human presence throughout 7. Schreve (1997) offers a solution: that the deposits date to terminal OIS7, as evidenced by similarities to the upper faunal suite at Aveley, the presence of cold-adapted species, and the dentition of the northern vole Microtus oeconomus, which shows a transitional morphotype between the fully temperate OIS7 specimens and those from sites assigned to OIS6. The abrupt warming during MIS 6.5 provides another possibility.

(a) Composite section through the Crayford and Erith brickpits (b) Spurrell’s original section showing position of main archaeological horizon and band of flint at Stoneham’s Pit. (After Spurrell 1880a.)

The archaeology from Crayford has proved similarly enigmatic. At Stoneham’s Pit, Spurrell (1880a and b, 1884) found large numbers of in situ, conjoinable, laminar Levallois artefacts at the base of a chalk river-cliff in association with animal bones. Similar finds were later made in adjacent pits (Chandler 1914, 1916). Most of the artefacts came from the Lower Brickearth. Spurrell’s main ‘floor’ was a sandy horizon within the Lower Brickearth, illustrated as occurring well above the base (1880a, Figure 1), while Chandler found refitting material in a similar position ‘at the base’ of the Brickearth in Rutter’s New West Pit (Chandler 1916, 241–2). Others were recovered at various levels with at least one from just above the Corbicula bed at Erith (Kennard 1944). Spurrell also mentions artefacts in a different preservational state from the surface of the underlying gravel and Chandler reported workmen’s tales of ‘knives’ (probably laminar Levallois) from here. Kennard supposed that the surface of the gravel had formed an older land surface related to the initial downcutting to this terrace level. Much has been made of the laminar, blade-line qualities of some of the Crayford material (Cook 1986; Révillion 1995), inviting comparisons with continental Middle Palaeolithic sites such as Seclin and notions that it anticipates the Upper Palaeolithic (cf. Mellars 1996).

The prevailing environments during the deposition of the Lower Brickearth and Corbicula bed were essentially similar (Kennard 1944). The molluscs reveal a slow-flowing river with little aquatic vegetation and non-marshy banks set in dry, open grassland; woodland and semi-aquatic species are sparse. The western edge of the river was set against Chalk and Thanet Sand that provided abundant flint (Spurrell 1880a and b; Chandler 1914, 1916). The mammals show a similar range of environments; dominated by open grassland species they famously contain a mixture of cold- and warm-loving species. The faunal composition, which includes the first occurrence of ground squirrel since the Anglian, suggested to Schreve an eastern European ‘feel’ testifying to more continental temperate conditions in Britain at this time, with warmer summers but harsher winters. The presence of Corbicula fluminalis, however, would seem to point to both warm summers and mild winters, the size distribution showing optimum rather than stressed conditions (Kennard 1944), although its recent southerly distribution may be masking wider tolerances (Keen, in Schreve et al. in prep). So, in all respects, a clear understanding of Crayford remains elusive.

Rich insect assemblages have been published from five MIS7 sites: Aveley (Schreve et al. in prep; see Text Box 5.2); Stoke Goldington (Green et al. 1996); Marsworth (Murton et al. 2001); Strensham (Rouffignac et al. 1995) and Stanton Harcourt (Briggs et al. 1985 see Text Box 5.6). Although the majority of remains recovered and published from these sites are beetles, other orders have been noted. Spiders and mites were reported at Stoke Goldington (Green et al. 1996), while Trichoptera (caddisflies), Dermapotera (earwigs), Megaloptera (alderflies), Diptera (flies/midges), Hymenoptera (wasps/bees/ants) and Hemiptera (aphids/shield bugs/cicadas) were found at Stanton Harcourt (Briggs et al. 1985).

THE STANTON HARCOURT CHANNEL (DIX’S PIT), OXFORDSHIRE

The Stanton Harcourt Channel deposits form part of the complex Summer-town–Radley Formation of the Upper Thames which subsumes sediments dating from MIS8 to possibly MIS2. The lower channel deposits of this group are highly organic with rich floral and faunal assemblages indicative of fully interglacial conditions during MIS7 (Briggs et al. 1985; Buckingham et al. 1996; Bridgland 1994); Schreve (2001b) assigns the site to the later part of the interglacial. The MIS7 channel deposits comprise silts, sands and gravels with a basal boulder bed, occupying a shallow SW–NE trending, single-thread channel incised into Oxford Clay (Briggs et al. 1985; Bridgland 1994; Buckingham et al. 1996). The ‘Ilford-type’ mammoth (a late form of Mammuthus trogontherii) dominates the mammalian assemblage, accompanied by large numbers of horse (Equus ferus) and straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus). Brown bear (Ursus arctos), red deer (Cervus elaphus), lion (Panthera leo) and spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) are also present in smaller numbers. Pollen preservation is poor, although 30 taxa have been recorded, mostly aquatics and marginal plants (Buckingham et al. 1996; Scott and Buckingham 2001). Arboreal pollen includes alder, birch, pine, blackthorn and elder with oak and other thermophilous species being represented by abundant and often very large pieces of wood. However, despite the presence of large tree trunks, the local environment was predominantly herb-rich grassland. Molluscs from the channel indicate an absence of dense forest in the local vicinity while the beetles are largely inhabitants of thinly vegetated, sunny ground, only a few shade-loving species being present. The occurrence of the molluscs Corbicula fluminalis and Potomida littoralis suggests warm conditions (Keen 1990), as does the insect fauna, which is dominated by species that today have a mainly southern distribution, suggesting a climate as warm or warmer than the present (Buckingham et al.1996). Fish remains have also been recovered from the channel, including stickleback, pike, perch and eel, together with specimens of frog and bird.

To date the channel deposits have produced just 27 artefacts, including 11 handaxes, a Levallois-like core and 2 chopping tools (Buckingham et al. 1996; Scott and Buckingham 2001; Kate Scott pers. comm. 2004). Although most are in an abraded condition, the core and some of the flakes are practically mint and may represent a human presence contemporary with the channel deposits (Buckingham et al. 1996). Raw materials are locally very poor and this is exactly the type of situation where one might again expect humans to have come prepared with a tool-kit that they subsequently took away with them; hence the large quantities of tools and knapping waste seen in the Lower Thames are absent. The abraded and derived material on the other hand is probably of pre-MIS7 origin, possibly the same source as the large collections of abraded material from the overlying (MIS6) Stanton Harcourt Gravel at Gravelly Guy/Smith’s Pit, Stanton Harcourt (MacRae 1982, 1991). According to Lee (2001) the Gravelly Guy/Smith’s Pit artefacts are very similar in condition and form to those from the channel deposits at Dix’s Pit (Buckingham et al. 1996), suggesting that they may all be earlier than the oldest deposits in which they were found and all derive from eroded, older pre-MIS7 landsurfaces (Hardaker 2001; Scott and Buckingham 2001).

Photograph of the site under excavation. Top photograph shows mammoth tusks and limb bones; bottom photograph shows mammoth tusks and bones, alongside large fragments of wood, including oak. (Courtesy Kate Scott.)

Artefacts from Stanton Harcourt. Left: a handaxe in rolled condition, and probably relating to an earlier occupation of the Upper Thames; right: a Levallois core in fresh condition, possibly evidence of contemporary MIS7 occupation. (Courtesy of Kate Scott.)

The Stanton Harcourt Gravel is also the most probable source of the artefacts from Mount Farm Pit and Queensford Pit at Berinsfield (MacRae 1982; Lee 2001) which produced over 200 artefacts of both flint and quartzite. These are mostly abraded and frost-damaged handaxes but some flakes (including handaxe thinning flakes) and, most notably, two Levallois cores and seven Levallois flakes, were also recovered. The rolled condition of the artefacts again suggests derivation from older deposits but Roe (1986) makes the important point that the Levallois material is fresher than the handaxes and may therefore be younger. The lack of any decent raw material in this area (the closest primary source is the Chiltern foothills six miles to the south) led Wymer to infer that, the handaxes manufacturing flakes notwithstanding, hominins must have been importing finished handaxes (as well as perhaps roughouts and other blanks) into the area. Indeed, preferential transport may explain why a region apparently so lacking in flint and decent archaeological assemblages has managed to produce a number of very large finished handaxes and a small amount of Levallois material (Roe 1994).

As stated in Chapter 2, at a regional scale beetle data are very useful for reconstruction of palaeoclimates, because many are highly habitat and temperature specific and because beetles respond to climate change, not by evolving in the Darwinian sense, but by altering their geographic ranges (Coope 2002). This is often achieved much faster than other terrestrial biota, which may lead to beetle faunas apparently being out of phase with other proxies (ibid). The beetle faunas from these five assemblages were made up of species that could occur today in southern England, with a few notable exotics. At Stanton Harcourt (Briggs et al. 1985) and Strensham (Rouffignac et al. 1995) the beetles were described as fully western European in aspect and possibly indicative of an oceanic type climate. July temperatures at Stanton Harcourt were suggested to be between 16 and 18º C, with those at Strensham slightly lower at 16º C; average winter temperatures were argued not to have been much below 0º C. At Stoke Goldington (Green et al. 1996) and Marsworth (Murton et al. 2001), however, a number of exotic species with ranges south and east of Britain, and some cold tolerant (but not obligate) species, are present, from which a more continental type climate has been inferred. At Stoke Goldington summer temperatures 1–2º C hotter than modern values were proposed, while at Marsworth the mutual climatic range (see Elias 1994) suggested maximum temperatures of 15–17º C, and a minimum temperature falling somewhere within the range of −9–1º C. As noted above, a number of floral and faunal elements have also suggested greater continentality during MIS7, but if the beetle record is taken at face value, then the climate may have fluctuated between oceanic and continental. In this case, these sites may belong to different parts of the interglacial, although it must be stressed that only a ‘hint’ of continentality really exists.

The humans who visited and moved through these MIS7 river valleys and surrounding plateaux would have thus been enveloped in a lush landscape that offered a variety of affordances (Text Box 5.7). Trees and shrubs would have provided both edible fruits and materials to make spears and other implements. Many of the herbaceous plants also had edible elements. The rich vegetation attracted a range of large herbivores, prey for hominin and non-human carnivores. Romantically we might see this as an unspoilt, giving environment, with bountiful animal and vegetal resources and very mild climate ideally suited for hominin interaction. In a sense it is surprising, therefore, that most of the sites that have provided detailed palaeobotanical or invertebrate evidence reveal very little evidence of hominin presence. It may be that the types of environment that provided preservational opportunities – swampy and perhaps stagnant areas – were simply not attractive to humans. Hominins may have focused their activities on more sandy or gravely substrate, or the drier grassy slopes, which would not have acted as such a hindrance to mobility and hunting. However, as we will see below, hominin occupation during MIS7 appears to have been surprisingly sparse and intermittent whatever the local conditions.

A RICH TAPESTRY OF MIS7 ENVIRONMENTS1

The various channels and floodplain pools found at MIS7 sites were heavily vegetated, with deep-water floating plants including water lily, floating heart and duckweed; and shallow-water floating plants like water violet, water soldier and mare’s tail. Other aquatics included water crowfoots, various ‘pondweeds’, and watercress. At many sites, the aquatic plants have suggested water that was generally still or slow moving, poorly oxygenated, and in Chalk areas highly calcareous. This is complemented by the coleoptera. Of the five insect-rich sites available, only Stanton Harcourt has a significant frequency of species indicative of free-flowing water, including Orectochilus villosus, a night hunter that preys on drowning animals trapped on the surface, and Esolus parallelepipedus, which lives amongst stones in vigorous streams (Briggs et al. 1985). Oulimnius tuberculatus, which inhabits shallow, well-oxygenated riffles in free flowing rivers, was present in Aveley Bed 3i, but otherwise the dominant insect signature from this and all other sites shows sluggish or stationary water and mats of decomposing material. Such environments are strongly indicated by a number of dyticid and hydraenid water beetles typical of grassy pools or backwaters and the majority of the Hydrophilidae which live off rotting vegetation. As these sites generally represent the deposits of significant Pleistocene rivers – the Thames and the Great Ouse – it seems likely that only marginal floodplain pools and cut-offs are represented in the fossil record, the main rivers not preserving high concentrations of coleopteran or plant remains.

The pollen and macrofossil records also reveal a variety of wetland plants that grew around the water margins including sedges, rushes, bulrush, watercress and wild mustards. Moving further onto the floodplains, the vegetation blends into a rather marshy, herb-rich grassland which Coope (in Ruffignac et al. 1995) reconstructs as lush water meadow, evocative of a warm summer’s day on the banks of the River Cam at Grantchester. Abundant herbaceous plants that grew in such places are found throughout the interglacial and included such familiars as ferns, valerian, marsh violet, teasel, forget-me-nots, meadowsweet, and several members of the buttercup and daisy families. Areas of base-rich marshland were also host to mosses and lichens. Several species of ground beetle indicate more open, meadow-like country shaded by weedy vegetation. This community – represented at different sites by a number of ground beetles such as Bembidion obtusum, Calathus melanocephalus and Patrobus atrorufus – is today found together on agricultural land, which Coope (in Murton et al. 2001) sees as mimicking these ancient habitats. In places, the marshy vegetation around all of these sites was more open, with bare patches of humus rich soil (e.g. Murton et al. 2001). Clivina fossor, found in four of the beetle assemblages, lives in patchy and open grassy vegetation where it excavates tunnels in damp, clayey or humusrich soils (Murton et al. 2001).

On the valley sides dry, herb-rich grassland existed with many species evocative of southern England today, including several species from the daisy–dandelion family, thistles, pinks, bellflowers, Jacob’s ladder, flax, gentian, and field pansy. Cornflowers, goosefoot, knotweeds, wormwood and various plantains grew on disturbed or sandy areas along the riverbanks or steepest slopes alongside stinging nettle and dock. The beetles also indicate some drier sandy/gravelly ground with sparse vegetation, such as Calathus and Agriotes, whose larvae feed on roots and grass. Such taxa are rare, however, probably indicating that these habitats occurred at some distance from the main catchment at the sites in question.

Dung beetles are found in some abundance, including both dung feeders (e.g. Aphodius) and dung predators (e.g. Oxytelus gibbulus which feeds on arthropods and worms in dung). This demonstrates that the large, herbivorous mammals found in the fossil record were active around the watercourses, their feeding behaviours helping to construct and maintain their own niches and to explain the apparent rarity of trees locally at many riverine sites (cf. Coope et al. 1961; Green et al. 1996). Carrion beetles show that these animals also died in these locations. At times and places these rather idyllic meadows must have resembled killing fields. Although humans are only minimally represented, if at all, the fossils of other large carnivores show that they were active in these environments in MIS7.

The pollen and macrofossils both record a variety of trees and tall shrubs with most of the modern ‘British’ deciduous and coniferous trees being present. Depending on which part of the interglacial is represented, these would have occurred as dense woodland, small clumps or even individual trees. Various woodland understorey plants have also been recorded from this interglacial including hazel and juniper, alongside bracken, ivy, fern, anemone, geranium and stitchwort. Such woodland probably stood on the interfluves and valley sides rather than in the valley bottoms. Within the beetle faunas only Aveley and Stanton Harcourt yielded obligate woodland species with most of these being dependant on deciduous trees. At Stanton Harcourt two species were found that are dependant on oak: the weevil Rhynchaenus quercus, whose larvae mine oak leaves, and Xyleborus dryophagus, a scolytid beetle that drills galleries in oak wood (Briggs et al. 1985). The Anobiid beetle Docatoma chysomelina, which inhabits fungi on dead or dying trees, was also recorded. Similarly, Aveley (Schreve et al. in prep) yielded two oak-dependant species, Curculio venosus, which lays its eggs in acorns, and the aforementioned R. quercus. A wider range of deciduous species is indicated by Scolytus multistriatus, a bark beetle that feeds on trees such as oak, elm, prunus and poplar, and Cerylon histeroides, which lives under dead bark on many species. The elaterid beetle Prosternon tesselatum, the larvae of which develop in rotting coniferous stumps, also implies the local presence of conifers; demonstrating that not all coniferous pollen is necessarily far travelled.

At the other sites, we can only assume that any trees that existed were outside the range of the beetle catchment. Recent studies (ibid.) have shown that the representation of ‘tree’ insects falls off very sharply with distance from trees, compounded by the fact that the migratory capacity of many woodland insects is limited. While a number do undertake flights to new feeding stations or to find mates, their preservation in the archaeological record depends highly on their flight (and death) paths intercepting suitable preservational deposits. So, archaeological deposits lacking woodland beetles do not automatically indicate a landscapes lacking in woodland vegetation, just that no trees were in the near proximity of the sampled area. Indeed, Bembidion gilvipes, which is usually found in moss and leaf litter in deciduous forest, is found at Strensham and Stoke Goldington, perhaps a small indication of some local woodland at these otherwise apparently open grassland sites.

NOTE

1 This section draws heavily on the work of Russell Coope, using the references cited in the main text.

Using only dated sites, White and Jacobi (2002) divided the British Middle Palaeolithic into two chronologically and technologically discrete entities: an Early Middle Palaeolithic (EMP) and a Late Middle Palaeolithic (LMP) (see Chapter 6 for the latter). This bipartite division recognised the EMP as a period in which Levallois technology dominated the lithic repertoire. Handaxes were practically absent and it can now be shown that the co-occurrence of handaxes and Levallois technology that so exercised the cultural sequences of Wymer (1968, 1985) and Roe (1981) is largely due to taphonomic mixing. In most cases, it is possible to demonstrate differences of preservational state, with the handaxes usually more worn and probably belonging to an earlier phase of occupation in the same location (Scott 2006; 2010; see below). This technological pattern stands in contrast to the Late Middle Palaeolithic, which is dominated by handaxe manufacture and discoidal core technology, but which has so far produce limited, if any, evidence of contemporary Levallois technology. The absence of chronological control over most occurrences of both Middle Palaeolithic handaxes and Levallois technology means that this pattern remains provisional, and could potentially be overturned by a single new discovery. However, for present purposes, it provides a useful heuristic, which enables us to use the occurrence of Levallois technology to gauge the distribution and extent of EMP occupation of Britain.

The English Rivers Project (Wymer 1992, 1993, 1994, 1996a, 1996b, 1997) listed some 250 findspots in England from which Levallois material has been reported (as well as another two from Wales), almost all situated in the southern half of the country, almost all found in fluvial deposits of major rivers and their tributaries, and nearly 50% located in the Thames Valley (Figure 5.8 and 5.9). This pattern is certainly an artefact of three controlling factors:

Number of known British Levallois sites and find spots, by modern county.

Number of known British Levallois sites and find spots, by river valley.

1 Most sites are located south of the maximum ice advance of the Last Glaciation (MIS2) and therefore safe from the direct effects of glacial destruction.

2 Regardless of the proportion of hominin activity that actually took place in and around river valleys, they provide ideal burial environments in which lithic materials are frequently preserved in primary and secondary contexts.

3 The extent to which major commercial quarrying activity and/or major urban expansion during the late nineteenthh and early twentieth centuries, combined with the energies of particular local collectors, provided opportunity for discovery and recovery of lithic collections.

It thus seems unlikely that either the distribution of Levallois findspots or frequency of Levallois artefacts provides a true impression of hominin settlement or activity during MIS7 (see below). They do, however, serve to demonstrate that, whenever they were present, Neanderthal groups utilising Levallois technology were ranging widely across the British landscape from the till plains of East Anglia to the rugged broken uplands of the west.