So far we’ve touched on Dow Theory, which is the basis of most trend following work being used today. We’ve examined the basic concepts of trend, such as support, resistance, and trendlines. And we’ve introduced volume and open interest. We’re now ready to take the next step, which is a study of chart patterns. You’ll quickly see that these patterns build on the previous concepts.

In Chapter 4, the definition of a trend was given as a series of ascending or descending peaks and troughs. As long as they were ascending, the trend was up; if they were descending, the trend was down. It was stressed, however, that markets also move sideways for a certain portion of the time. It is these periods of sideways market movement that will concern us most in these next two chapters.

It would be a mistake to assume that most changes in trend are very abrupt affairs. The fact is that important changes in trend usually require a period of transition. The problem is that these periods of transition do not always signal a trend reversal. Sometimes these sideways periods just indicate a pause or consolidation in the existing trend after which the original trend is resumed.

The study of these transition periods and their forecasting implications leads us to the question of price patterns. First of all, what are price patterns? Price patterns are pictures or formations, which appear on price charts of stocks or commodities, that can be classified into different categories, and that have predictive value.

There are two major categories of price patterns—reversal and continuation. As these names imply, reversal patterns indicate that an important reversal in trend is taking place. The continuation patterns, on the other hand, suggest that the market is only pausing for awhile, possibly to correct a near term overbought or oversold condition, after which the existing trend will be resumed. The trick is to distinguish between the two types of patterns as early as possible during the formation of the pattern.

In this chapter, we’ll be examining the five most commonly used major reversal patterns: the head and shoulders, triple tops and bottoms, double tops and bottoms, spike (or V) tops and bottoms, and the rounding (or saucer) pattern. We will examine the price formation itself, how it is formed on the chart, and how it can be identified. We will then look at the other important considerations—the accompanying volume pattern and measuring implications.

Volume plays an important confirming role in all of these price patterns. In times of doubt (and there are lots of those), a study of the volume pattern accompanying the price data can be the deciding factor as to whether or not the pattern can be trusted.

Most price patterns also have certain measuring techniques that help the analyst to determine minimum price objectives. While these objectives are only an approximation of the size of the subsequent move, they are helpful in assisting the trader to determine his or her reward to risk ratio.

In Chapter 5, we’ll look at a second category of patterns—the continuation variety. There we will examine triangles, flags, pennants, wedges, and rectangles. These patterns usually reflect pauses in the existing trend rather than trend reversals, and are usually classified as intermediate and minor as opposed to major.

Before beginning our discussion of the individual major reversal patterns, there are a few preliminary points to be considered that are common to all of these reversal patterns.

The Need for a Prior Trend. The existence of a prior major trend is an important prerequisite for any reversal pattern. A market must obviously have something to reverse. A formation occasionally appears on the charts, resembling one of the reversal patterns. If that pattern, however, has not been preceded by a trend, there is nothing to reverse and the pattern is suspect. Knowing where certain patterns are most apt to occur in the trend structure is one of the key elements in pattern recognition.

A corollary to this point of having a prior trend to reverse is the matter of measuring implications. It was stated earlier that most of the measuring techniques give only minimum price objectives. The maximum objective would be the total extent of the prior move. If a major bull market has occurred and a major topping pattern is being formed, the maximum implication for the potential move to the downside would be a 100% retracement of the bull market, or the point at which it all began.

The Breaking of Important Trendlines. The first sign of an impending trend reversal is often the breaking of an important trendline. Remember, however, that the violation of a major trendline does not necessarily signal a trend reversal. What is being signaled is a change in trend. The breaking of a major up trendline might signal the beginning of a sideways price pattern, which later would be identified as either the reversal or consolidation type. Sometimes the breaking of the major trendline coincides with the completion of the price pattern.

The Larger the Pattern, the Greater the Potential. When we use the term “larger,” we are referring to the height and the width of the price pattern. The height measures the volatility of the pattern. The width is the amount of time required to build and complete the pattern. The greater the size of the pattern—that is, the wider the price swings within the pattern (the volatility) and the longer it takes to build—the more important the pattern becomes and the greater the potential for the ensuing price move.

Virtually all of the measuring techniques in these two chapters are based on the height of the pattern. This is the method applied primarily to bar charts, which use a vertical measuring criteria. The practice of measuring the horizontal width of a price pattern usually is reserved for point and figure charting. That method of charting uses a device known as the count, which assumes a close relationship between the width of a top or bottom and the subsequent price target.

Differences Between Tops and Bottoms. Topping patterns are usually shorter in duration and are more volatile than bottoms. Price swings within the tops are wider and more violent. Tops usually take less time to form. Bottoms usually have smaller price ranges, but take longer to build. For this reason it is usually easier and less costly to identify and trade bottoms than to catch market tops. One consoling factor, which makes the more treacherous topping patterns worthwhile, is that prices tend to decline faster than they go up. Therefore, the trader can usually make more money a lot faster by catching the short side of a bear market than by trading the long side of a bull market. Everything in life is a tradeoff between reward and risk. The greater risks are compensated for by greater rewards and vice versa. Topping patterns are harder to catch, but are worth the effort.

Volume is More Important on the Upside. Volume should generally increase in the direction of the market trend and is an important confirming factor in the completion of all price patterns. The completion of each pattern should be accompanied by a noticeable increase in volume. However, in the early stages of a trend reversal, volume is not as important at market tops. Markets have a way of “falling of their own weight” once a bear move gets underway. Chartists like to see an increase in trading activity as prices drop, but it is not critical. At bottoms, however, the volume pickup is absolutely essential. If the volume pattern does not show a significant increase during the upside price breakout, the entire price pattern should be questioned. We will be taking a more in-depth look at volume in Chapter 7.

Let’s take a close look now at what is probably the best known and most reliable of all major reversal patterns—the head and shoulders reversal. We’ll spend more time on this pattern because it is important and also to explain all the nuances involved. Most of the other reversal patterns are just variations of the head and shoulders and will not require as extensive a treatment.

This major reversal pattern, like all of the others, is just a further refinement of the concepts of trend covered in Chapter 4. Picture a situation in a major uptrend, where a series of ascending peaks and troughs gradually begin to lose momentum. The uptrend then levels off for awhile. During this time the forces of supply and demand are in relative balance. Once this distribution phase has been completed, support levels along the bottom of the horizontal trading range are broken and a new downtrend has been established. That new downtrend now has descending peaks and troughs.

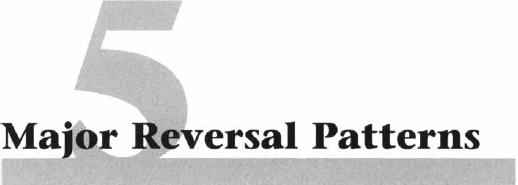

Let’s see how this scenario would look on a head and shoulders top. (See Figures 5.1a and b.) At point A, the uptrend is proceeding as expected with no signs of a top. Volume expands on the price move into new highs, which is normal. The corrective dip to point B is on lighter volume, which is also to be expected. At point C, however, the alert chartist might notice that the volume on the upside breakout through point A is a bit lighter than on the previous rally. This change is not in itself of major importance, but a little yellow caution light goes on in the back of the analyst’s head.

Figure 5.1a Example of a head and shoulders top. The left and right shoulders (A and E) are at about the same height. The head (C) is higher than either shoulder. Notice the lighter volume on each peak. The pattern is completed on a close under the neckline (line 2). The minimum objective is the vertical distance from the head to the neckline projected downward from the breaking of the neckline. A return move will often occur back to the neckline, which should not recross the neckline once it has been broken.

Figure 5.1b A head and shoulders top. The three peaks show the head higher than either shoulder. The return move (see arrow) back to the neckline occurred on schedule.

Prices then begin to decline to point D and something even more disturbing happens. The decline carries below the top of the previous peak at point A. Remember that, in an uptrend, a penetrated peak should function as support on subsequent corrections. The decline well under point A, almost to the previous reaction low at point B, is another warning that something may be going wrong with the uptrend.

The market rallies again to point E, this time on even lighter volume, and isn’t able to reach the top of the previous peak at point C. (That last rally at point E will often retrace one-half to two-thirds of the decline from points C to D.) To continue an uptrend, each high point must exceed the high point of the rally preceding it. The failure of the rally at point E to reach the previous peak at point C fulfills half of the requirement for a new downtrend—namely, descending peaks.

By this time, the major up trendline (line 1) has already been broken, usually at point D, constituting another danger signal. But, despite all of these warnings, all that we know at this point is that the trend has shifted from up to sideways. This might be sufficient cause to liquidate long positions, but not necessarily enough to justify new short sales.

By this time, a flatter trendline can be drawn under the last two reaction lows (points B and D), which is called a neckline (see line 2). This line generally has a slight upward slope at tops (although it’s sometimes horizontal and, less often, tilts downward). The deciding factor in the resolution of the head and shoulders top is a decisive closing violation of that neckline. The market has now violated the trendline along the bottom of points B and D, has broken under support at point D, and has completed the requirement for a new downtrend—descending peaks and troughs. The new downtrend is now identified by the declining highs and lows at points C, D, E, and F. Volume should increase on the breaking of the neckline. A sharp increase in downside volume, however, is not critically important in the initial stages of a market top.

Usually a return move develops which is a bounce back to the bottom of the neckline or to the previous reaction low at point D (see point G), both of which have now become overhead resistance. The return move does not always occur or is sometimes only a very minor bounce. Volume may help determine the size of the bounce. If the initial breaking of the neckline is on very heavy trading, the odds for a return move are diminished because the increased activity reflects greater downside pressure. Lighter volume on the initial break of the neckline increases the likelihood of a return move. That bounce, however, should be on light volume and the subsequent resumption of the new downtrend should be accompanied by noticeably heavier trading activity.

Let’s review the basic ingredients for a head and shoulders top.

What has become evident is three well defined peaks. The middle peak (the head) is slightly higher than either of the two shoulders (points A and E). The pattern, however, is not complete until the neckline is decisively broken on a closing basis. Here again, the 1-3% penetration criterion (or some variation thereof) or the requirement of two successive closes below the neckline (the two day rule) can be used for added confirmation. Until that downside violation takes place, however, there is always the possibility that the pattern is not really a head and shoulders top and that the uptrend may resume at some point.

The accompanying volume pattern plays an important role in the development of the head and shoulders top as it does in all price patterns. As a general rule, the second peak (the head) should take place on lighter volume than the left shoulder. This is not a requirement, but a strong tendency and an early warning of diminishing buying pressure. The most important volume signal takes place during the third peak (the right shoulder). Volume should be noticeably lighter than on the previous two peaks. Volume should then expand on the breaking of the neckline, decline during the return move, and then expand again once the return move is over.

As mentioned earlier, volume is less critical during the completion of market tops. But, at some point, volume should begin to increase if the new downtrend is to be continued. Volume plays a much more decisive role at market bottoms, a subject to be discussed shortly. Before doing so, however, let’s discuss the measuring implications of the head and shoulders pattern.

The method of arriving at a price objective is based on the height of the pattern. Take the vertical distance from the head (point C) to the neckline. Then project that distance from the point where the neckline is broken. Assume, for example, that the top of the head is at 100 and the neckline is at 80. The vertical distance, therefore, would be the difference, which is 20. That 20 points would be measured downward from the level at which the neckline is broken. If the neckline in Figure 5.1a is at 82 when broken, a downside objective would be projected to the 62 level (82 – 20=62).

Another technique that accomplishes about the same task, but is a bit easier, is to simply measure the length of the first wave of the decline (points C to D) and then double it. In either case, the greater the height or volatility of the pattern, the greater the objective. Chapter 4 stated that the measurement taken from a trendline penetration was similar to that used in the head and shoulders pattern. You should be able to see that now. Prices travel roughly the same distance below the broken neckline as they do above it. You’ll see throughout our entire study of price patterns that most price targets on bar charts are based on the height or volatility of the various patterns. The theme of measuring the height of the pattern and then projecting that distance from a breakout point will be constantly repeated.

It’s important to remember that the objective arrived at is only a minimum target. Prices will often move well beyond the objective. Having a minimum target to work with, however, is very helpful in determining beforehand whether there is enough potential in a market move to warrant taking a position. If the market exceeds the price objective, that’s just icing on the cake. The maximum objective is the size of the prior move. If the previous bull market went from 30 to 100, then the maximum downside objective from a topping pattern would be a complete retracement of the entire upmove all the way down to 30. Reversal patterns can only be expected to reverse or retrace what has gone before them.

A number of other factors should be considered while trying to arrive at a price objective. The measuring techniques from price patterns, such as the one just mentioned for the head and shoulders top, are only the first step. There are other technical factors to take into consideration. For example, where are the prominent support levels left by the reaction lows during the previous bull move? Bear markets often pause at these levels. What about percentage retracements? The maximum objective would be a 100% retracement of the previous bull market. But where are the 50% and 66% retracement levels? Those levels often provide significant support under the market. What about any prominent gaps underneath? They often function as support areas. Are there any long term trendlines visible below the market?

The technician must consider other technical data in trying to pinpoint price targets taken from price patterns. If a downside price measurement, for example, projects a target to 30, and there is a prominent support level at 32, then the chartist would be wise to adjust the downside measurement to 32 instead of 30. As a general rule, when a slight discrepancy exists between a projected price target and a clearcut support or resistance level, it’s usually safe to adjust the price target to that support or resistance level. It is often necessary to adjust the measured targets from price patterns to take into account additional technical information. The analyst has many different tools at his or her disposal. The most skillful technical analysts are those who learn to blend all of those tools together properly.

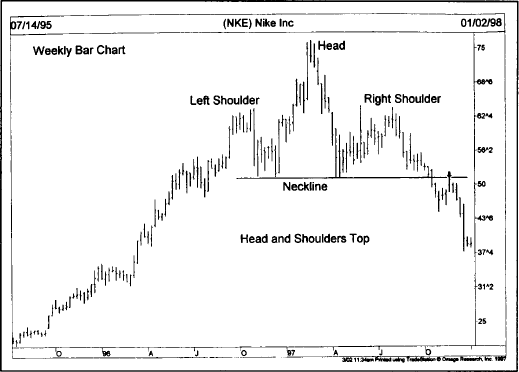

The head and shoulders bottom, or the inverse head and shoulders as it is sometimes called, is pretty much a mirror image of the topping pattern. As Figure 5.2a shows, there are three distinct bottoms with the head (middle trough) a bit lower than either of the two shoulders. A decisive close through the neckline is also necessary to complete the pattern, and the measuring technique is the same. One slight difference at the bottom is the greater tendency for the return move back to the neckline to occur after the bullish breakout. (See Figure 5.2b.)

Figure 5.2a Example of an inverse head and shoulders. The bottom version of this pattern is a mirror image of the top. The only significant difference is the volume pattern in the second half of the pattern. The rally from the head should see heavier volume, and the breaking of the neckline should see a burst of trading activity. The return move back to the neckline is more common at bottoms.

The most important difference between the top and bottom patterns is the volume sequence. Volume plays a much more critical role in the identification and completion of a head and shoulders bottom. This point is generally true of all bottom patterns. It was stated earlier that markets have a tendency to “fall of their own weight.” At bottoms, however, markets require a significant increase in buying pressure, reflected in greater volume, to launch a new bull market.

Figure 5.2b A head and shoulders bottom. The neckline has a slight downward slant, which is normally the case. The pullback after the breakout (see arrow) nicked the neckline a bit, but then resumed the uptrend.

A more technical way of looking at this difference is that a market can fall just from inertia. Lack of demand or buying interest on the part of traders is often enough to push a market lower; but a market does not go up on inertia. Prices only rise when demand exceeds supply and buyers are more aggressive than sellers.

The volume pattern at the bottom is very similar to that at the top for the first half of the pattern. That is, the volume at the head is a bit lighter than that at the left shoulder. The rally from the head, however, should begin to show not only an increase in trading activity, but the level of volume often exceeds that registered on the rally from the left shoulder. The dip to the right shoulder should be on very light volume. The critical point occurs at the rally through the neckline. This signal must be accompanied by a sharp burst of trading volume if the breakout is for real.

This point is where the bottom differs the most from the top. At the bottom, heavy volume is an absolutely essential ingredient in the completion of the basing pattern. The return move is more common at bottoms than at tops and should occur on light volume. Following that, the new uptrend should resume on heavier volume. The measuring technique is the same as at the top.

The neckline at the top usually slopes slightly upward. Sometimes, however, it is horizontal. In either case, it doesn’t make too much of a difference. Once in a while, however, a top neckline slopes downward. This slope is a sign of market weakness and is usually accompanied by a weak right shoulder. However, this is a mixed blessing. The analyst waiting for the breaking of the neckline to initiate a short position has to wait a bit longer, because the signal from the down sloping neckline occurs much later and only after much of the move has already taken place. For basing patterns, most necklines have a slight downward tilt. A rising neckline is a sign of greater market strength, but with the same drawback of giving a later signal.

A variation of the head and shoulders pattern sometimes occurs which is called the complex head and shoulders pattern. These are patterns where two heads may appear or a double left and right shoulder. These patterns are not that common, but have the same forecasting implications. A helpful hint in this regard is the strong tendency toward symmetry in the head and shoulders pattern. This means that a single left shoulder usually indicates a single right shoulder. A double left shoulder increases the odds of a double right shoulder.

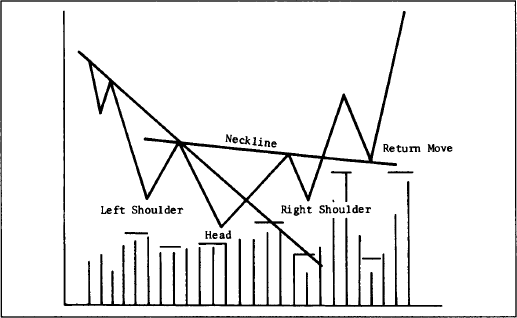

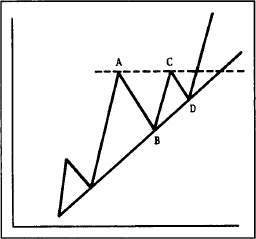

Market tactics play an important role in all trading. Not all technical traders like to wait for the breaking of the neckline before initiating a new position. As Figure 5.3 shows, more aggressive traders, believing that they have correctly identified a head and shoulders bottom, will begin to probe the long side during the formation of the right shoulder. Or they will buy the first technical signal that the decline into the right shoulder has ended.

Some will measure the distance of the rally from the bottom of the head (points C to D) and then buy a 50% or 66% retracement of that rally. Still others would draw a tight down trendline along the decline from points D to E and buy the first upside break of that trendline. Because these patterns are reasonably symmetrical, some will buy into the right shoulder as it approaches the same level as the bottom of the left shoulder. A lot of anticipatory buying takes place during the formation of the right shoulder. If the initial long probe proves to be profitable, additional positions can be added on the actual penetration of the neckline or on the return move back to the neckline after the breakout.

Once prices have moved through the neckline and completed a head and shoulders pattern, prices should not recross the neckline again. At a top, once the neckline has been broken on the downside, any decisive close back above the neckline is a serious warning that the initial breakdown was probably a bad signal, and creates what is often called, for obvious reasons, a failed head and shoulders. This type of pattern starts out looking like a classic head and shoulders reversal, but at some point in its development (either prior to the breaking of the neckline or just after it), prices resume their original trend.

Figure 5.3 Tactics for a head and shoulders bottom. Many technical traders will begin to initiate long positions while the right shoulder (E) is still being formed. One-half to two-thirds pullback of the rally from points C to D, a decline to the same level as the left shoulder at point A, or the breaking of a short term down trendline (line 1) all provide early opportunities for market entry. More positions can be added on the breaking of the neckline or the return move back to the neckline.

There are two important lessons here. The first is that none of these chart patterns are infallible. They work most of the time, but not always. The second lesson is that technical traders must always be on the alert for chart signs that their analysis is incorrect. One of the keys to survival in the financial markets is to keep trading losses small and to exit a losing trade as quickly as possible. One of the greatest advantages of chart analysis is its ability to quickly alert the trader to the fact that he or she is on the wrong side of the market. The ability and willingness to quickly recognize trading errors and to take defensive action immediately are qualities not to be taken lightly in the financial markets.

Before moving on to the next price pattern, there’s one final point to be made on the head and shoulders. We started this discussion by listing it as the best known and most reliable of the major reversal patterns. You should be warned, however, that this formation can, on occasion, act as a consolidation rather than a reversal pattern. When this does happen, it’s the exception rather than the rule. We’ll talk more about this in Chapter 6, “Continuation Patterns.”

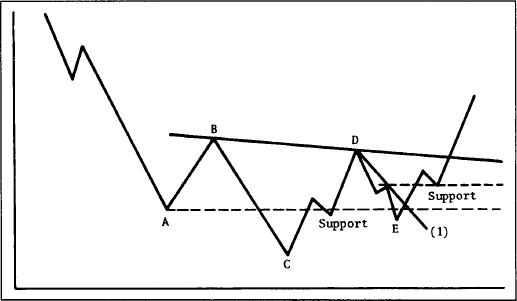

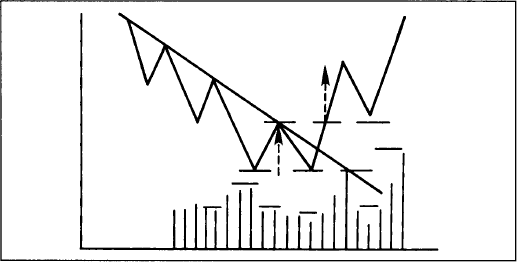

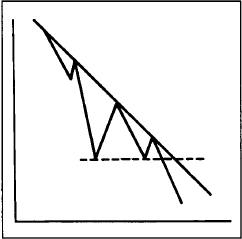

Most of the points covered in the treatment of the head and shoulders pattern are also applicable to other types of reversal patterns. (See Figures 5.4a-c.) The triple top or bottom, which is much rarer in occurrence, is just a slight variation of that pattern. The main difference is that the three peaks or troughs in the triple top or bottom are at about the same level. (See Figure 5.4a.) Chartists often disagree as to whether a reversal pattern is a head and shoulders or a triple top. The argument is academic, because both patterns imply the exact same thing.

The volume tends to decline with each successive peak at the top and should increase at the breakdown point. The triple top is not complete until support levels along both of the intervening lows have been broken. Conversely, prices must close through the two intervening peaks at the bottom to complete a triple bottom. (As an alternate strategy, the breaking of the nearest peak or trough can also be used as a reversal signal.) Heavy upside volume on the completion of the bottom is also essential.

Figure 5.4a A triple top. Similar to the head and shoulders except that all peaks are at the same level. Each rally peak should be on lighter volume. The pattern is complete when both troughs have been broken on heavier volume. The measuring technique is the height of the pattern projected downward from the breakdown point. Return moves back to the lower line are not unusual.

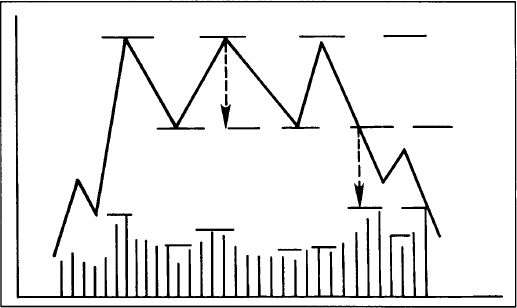

Figure 5.4b A triple bottom. Similar to a head and shoulders bottom except that each low is at the same level. A mirror image of the triple top except that volume is more important on the upside breakout.

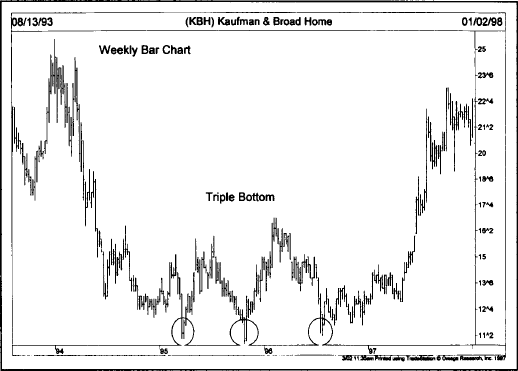

Figure 5.4c A triple bottom reversal pattern. Prices found support just below 12 three times on this chart before launching a major advance. The bottom formation on this weekly chart lasted two full years, thereby giving it major significance.

The measuring implication is also similar to the head and shoulders, and is based on the height of the pattern. Prices will usually move a minimum distance from the breakout point at least equal to the height of the pattern. Once the breakout occurs, a return move to the breakout point is not unusual. Because the triple top or bottom represents only a minor variation of the head and shoulders pattern, we won’t say much more about it here.

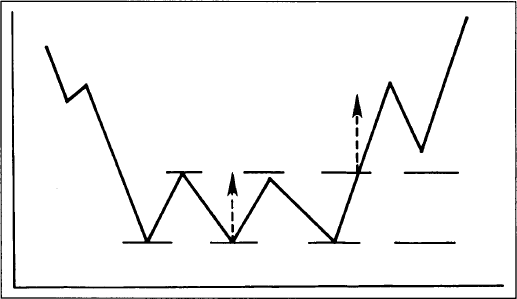

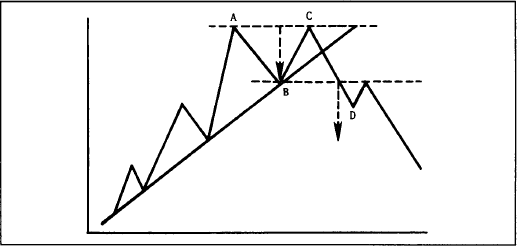

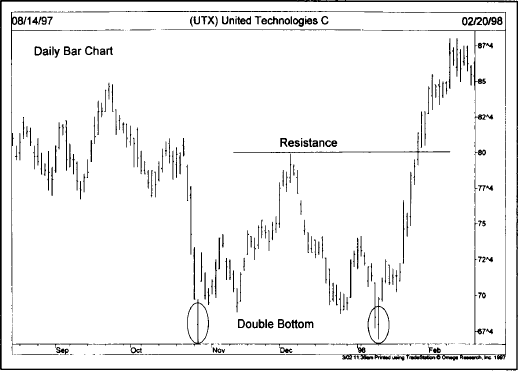

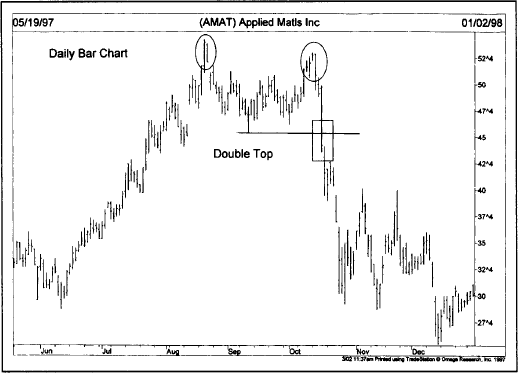

A much more common reversal pattern is the double top or bottom. Next to the head and shoulders, it is the most frequently seen and the most easily recognized. (See Figures 5.5a-e.) Figures 5.5a and 5.5b show both the top and bottom variety. For obvious reasons, the top is often referred to as an “M” and the bottom as a “W.” The general characteristics of a double top are similar to that of the head and shoulders and triple top except that only two peaks appear instead of three. The volume pattern is similar as is the measuring rule.

Figure 5.5a Example of a double top. This pattern has two peaks (A and C) at about the same level. The pattern is complete when the middle trough at point B is broken on a closing basis. Volume is usually lighter on the second peak (C) and picks up on the breakdown (D). A return move back to the lower line is not unusual. The minimum measuring target is the height of the top projected downward from the breakdown point.

Figure 5.5b Example of a double bottom. A mirror image of the double top. Volume is more important on the upside breakout. Return moves back to the breakout point are more common at bottoms.

Figure 5.5c Example of a double bottom. This stock bounced sharply off the 68 level twice over a span of three months. Note that the second bottom was also an upside reversal day. The breaking of resistance at 80 completed the bottom.

In an uptrend (as shown in Figure 5.5a), the market sets a new high at point A, usually on increased volume, and then declines to point B on declining volume. So far, everything is proceeding as expected in a normal uptrend. The next rally to point C, however, is unable to penetrate the previous peak at A on a closing basis and begins to fall back again. A potential double top has been set up. I use the word “potential” because, as is the case with all reversal patterns, the reversal is not complete until the previous support point at B is violated on a closing basis. Until that happens, prices could be in just a sideways consolidation phase, preparing for a resumption of the original uptrend.

Figure 5.5d Example of a double top. Sometimes the second peak doesn’t quite reach the first peak as in this example. This two month double top signaled a major decline. The actual signal was the breaking of support near 46 (see box).

The ideal top has two prominent peaks at about the same price level. Volume tends to be heavier during the first peak and lighter on the second. A decisive close under the middle trough at point B on heavier volume completes the pattern and signals a reversal of trend to the downside. A return move to the breakout point is not unusual prior to resumption of the downtrend.

The measuring technique for the double top is the height of the pattern projected from the breakdown point (the point where the middle trough at point B is broken). As an alternative, measure the height of the first downleg (points A to B) and project that length downward from the middle trough at point B. Measurements at the bottom are the same, but in the other direction.

Figure 5.5e Price patterns show up regularly on the charts of major stock averages. On this chart, the Nasdaq Composite Index formed a double bottom near the 1470 level before turning higher. The break of the down trendline (see box) confirmed the upturn.

As in most other areas of market analysis, real-life examples are usually some variation of the ideal. For one thing, sometimes the two peaks are not at exactly the same price level. On occasion, the second peak will not quite reach the level of the first peak, which is not too problematical. What does cause some problems is when the second peak actually exceeds the first peak by a slight margin. What at first may appear to be a valid upside breakout and resumption of the uptrend may turn out to be part of the topping process. To help resolve this dilemma, some of the filtering criteria already mentioned may come in handy.

Most chartists require a close beyond a previous resistance peak instead of just an intraday penetration. Second, a price filter of some type might be used. One such example is a percentage penetration criterion (such as 1% or 3%). Third, the two day penetration rule could be used as an example of a time filter. In other words, prices would have to close beyond the top of the first peak for two consecutive days to signal a valid penetration. Another time filter could be a Friday close beyond the previous peak. The volume on the upside breakout might also provide a clue to its reliability.

These filters are certainly not infallible, but do serve to reduce the number of false signals (or whipsaws) that often occur. Sometimes these filters are helpful, and sometimes they’re not. The analyst must face the realization that he or she is dealing with percentages and probabilities, and that there will be times when bad signals occur. That’s simply a fact of trading life.

It’s not that unusual for the final leg or wave of a bull market to set a new high before reversing direction. In such a case, the final upside breakout would become a “bull trap.” (See Figures 5.6a and b.) We’ll show you some indicators later on that may help you spot these false breakouts.

The terms “double top and bottom” are greatly overused in the financial markets. Most potential double tops or bottoms wind up being something else. The reason for this is that prices have a strong tendency to back off from a previous peak or bounce off a previous low. These price changes are a natural reaction and do not in themselves constitute a reversal pattern. Remember that, at a top, prices must actually violate the previous reaction low before the double top exists.

Figure 5.6a Example of a false breakout, usually called a bull trap. Sometimes near the end of a major uptrend, prices will exceed a previous peak before failing. Chartists use various time and price filters to reduce such whipsaws. This topping pattern would probably qualify as a double top.

Figure 5.6b Example of a false breakout. Notice that the upside breakout was on light volume and the subsequent decline on heavy volume—a negative chart combination. Watching the volume helps avoid some false breakouts, but not all.

Notice in Figure 5.7a that the price at point C backs off from the previous peak at point A. This is perfectly normal action in an uptrend. Many traders, however, will immediately label this pattern as a double top as soon as prices fail to clear the first peak on the first attempt. Figure 5.7b shows the same situation in a downtrend. It is very difficult for the chartist to determine whether the pullback from the previous peak or the bounce from the previous low is just a temporary setback in the existing trend or the start of a double top or bottom reversal pattern. Because the technical odds usually favor continuation of the present trend, it is usually wise to await completion of the pattern before taking action.

Figure 5.7a Example of a normal pullback from a previous peak before resumption of the uptrend. This is normal market action and not to be confused with a double top. The double top only occurs when support at point B is broken.

Figure 5.7b Example of a normal bounce off a previous low. This is normal market action and not to be confused with a double bottom. Prices will normally bounce off a previous low at least once, causing premature calls for a double bottom.

Finally, the size of the pattern is always important. The longer the time period between the two peaks and the greater the height of the pattern, the greater the potential impending reversal. This is true of all chart patterns. In general, most valid double tops or bottoms should have at least a month between the two peaks or troughs. Some will even be two or three months apart. (On longer range monthly and weekly charts, these patterns can span several years.) Most of the examples used in this discussion have described market tops. The reader should be aware by now that bottoming patterns are mirror images of tops except for some of the general differences already touched upon at the beginning of the chapter.

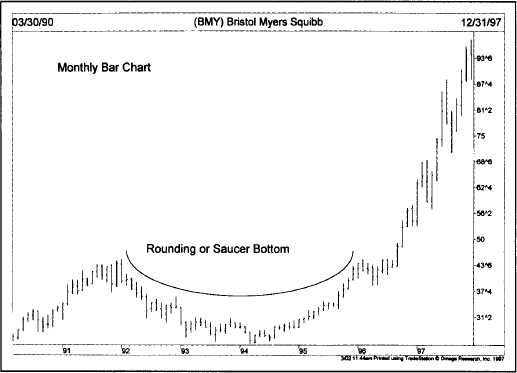

Although not seen as frequently, reversal patterns sometimes take the shape of saucers or rounding bottoms. The saucer bottom shows a very slow and very gradual turn from down to sideways to up. It is difficult to tell exactly when the saucer has been completed or to measure how far prices will travel in the opposite direction. Saucer bottoms are usually spotted on weekly or monthly charts that span several years. The longer they last, the more significant they become. (See Figure 5.8.)

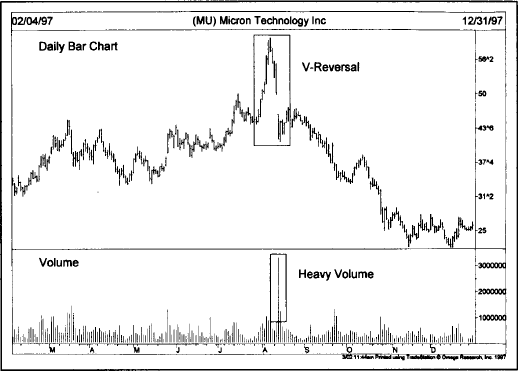

Spikes are the hardest market turns to deal with because the spike (or V pattern) happens very quickly with little or no transition period. They usually take place in a market that has gotten so overextended in one direction, that a sudden piece of adverse news causes the market to reverse direction very abruptly. A daily or weekly reversal, on very heavy volume, is sometimes the only warning they give us. That being the case, there’s not much more we can say about them except that we hope you don’t run into too many of them. Some technical indicators we discuss in later chapters will help you determine when markets have gotten dangerously over-extended. (See Figure 5.9.)

Figure 5.8 This chart shows what a saucer (or rounding) bottom looks like. They’re very slow and gradual, but usually mark major turns. This bottom lasted four years.

Figure 5.9 Example of a v reversal pattern. These sudden reversals take place with little or no warning. A sudden price drop on heavy volume is usually the only telltale sign. Unfortunately, these sudden turns are hard to spot in advance.

We’ve discussed the five most commonly used major reversal patterns—the head and shoulders, double and triple tops and bottoms, the saucer, and the V, or spike. Of those, the most common are the head and shoulders, and double tops and bottoms. These patterns usually signal important trend reversals in progress and are classified as major reversal patterns. There is another class of patterns, however, which are shorter term in nature and usually suggest trend consolidations rather than reversals. They are aptly called continuation patterns. Let’s look at this other type of pattern in Chapter 6.