Chapter 6

Choosing a Greywater System

The next step is to review your site and overall goals to determine which greywater systems are the best match.

In this chapter we’ll review basic design considerations, where to send the water, and when not to use greywater. I’ll discuss how to use greywater indoors for toilet flushing, and, for renters or others who don’t want to alter their home, how to use greywater without a system. This chapter ends with a review of greywater systems types and their general costs, capabilities, and skill level required to install them.

In this chapter:

System Design Considerations

What part of the landscape should you irrigate — the lawn uphill from your house or the fruit trees downslope? Before getting to specifics, I’ll cover general design principles to help narrow your options and define your goals. Start with the following basic considerations.

Can you have a gravity irrigation system? First, consider areas of your yard close to the greywater source that require irrigation and are NOT uphill or across large areas of hardscape. Gravity-based systems typically last longer, cost less, use fewer resources, and require less maintenance than pumped systems.

Does water infiltrate well in the area you plan to use greywater? If this is an area you don’t already irrigate, you should perform an infiltration test (see here) to make sure greywater will soak into the soil without pooling.

Will the location of the greywater system cause any unforeseen problems? Maintain setbacks to the house’s foundation, neighbors’ yards, retaining walls, streams and lakes, groundwater table, and water supply wells. See the chart at right for some standard setback distances (based on California code). Setback requirements vary by area; check with your local code authority for a permitted system. Codes often include setbacks for septic tanks and leach lines, although it seems illogical to require a setback from a leach line since greywater would have been in the leach line if it wasn’t diverted from the septic system.

Example Setbacks for Greywater Irrigation Area (minimum distance)

|

|

Building foundations

|

2 feet

|

|

Property lines

|

1.5 feet

|

|

Water supply wells

|

100 feet

|

|

Streams and lakes

|

100 feet

|

|

Water table

|

3 feet above

|

|

Retaining wall

|

2 feet

|

In addition to the basic elements shown in the chart, greywater surge tanks also may have setback requirements. If your project requires a permit and you need a tank, ask your local building department for their thoughts on tank placement. Other cases may involve special situations that require modifications to the setback requirements. For example, if your neighbor’s yard is lower and covered with hardscape (e.g., a concrete patio), a 1.5-foot setback will not be enough distance to prevent leaking of greywater onto the neighbor’s patio. Increase setbacks anytime the greywater-irrigated landscape is elevated above any type of hardscape, like sidewalks, patios, walkways, or roads.

Avoid Common Problems and Design Pitfalls

- Don’t store greywater! Nutrients in greywater break down over time, causing a stink. To avoid odor problems with surge tanks (in a pumped system), make sure the tank is vented, can be cleaned, and is located out of the living space. (And don’t send greywater to mix with rainwater in a tank; the tank will become contaminated.)

- Don’t allow greywater to puddle or pond up. It is non-potable and people shouldn’t contact it. Ponding also creates mosquito breeding grounds.

- KISS (Keep It Simple or you’ll be Sorry). The more components and parts used, the more potential for system failure. At the residential level, simple systems tend to work best, last longest, and cost less than complex setups. Many systems do not require a tank, pump, or filter; use these components only when necessary.

- Plan carefully to match your greywater production with the needs of your plants.

- Use plant-friendly products (those without lots of salts, boron, or chlorine bleach).

Designing a New House with a Greywater System

If you plan your house with the greywater system in mind (not to mention rainwater catchment and waterless toilets), you’ll have more options and an easier system to install. Here are some planning tips:

- Locate the house above the landscape area when possible.

- Keep the plumbing accessible (no concrete slab). If you will have a slab foundation, design an accessible location for diverting greywater, and don’t join greywater and blackwater pipes below the slab.

- Design the landscape to fit with your greywater (and rainwater) supply.

- If you are not planning to install the greywater system immediately, put in the diverter valve with a “greywater stub-out,” or create a place to easily add it in later.

See Greywater-Ready Building Construction for more details on greywater access locations.

When Greywater Is Not a Great Idea

Outdoor greywater irrigation systems are not always appropriate. Here are some situations where greywater reuse may not be suitable:

Uninterested and uncooperative people living in the home. If people won’t use plant-friendly products or maintain the greywater system, it could harm the landscape (unless the landscape is designed with salt- and boron-tolerant plants, and an outside person does the maintenance).

Difficult-to-access drainpipes. When it’s very difficult to access greywater sources, such as a house on a slab foundation with all greywater sources in the middle of the home, money may be better spent on an alternative system, such as ultra-efficient fixtures and appliances and rainwater harvesting systems.

Very poorly draining soil. If you live in a swamp, it will be hard to infiltrate greywater into the native soil, and you won’t be saving water; swamps don’t need irrigation. Consider an ecological disposal system, like a constructed wetland, or an indoor greenhouse greywater system (see Greywater for Greenhouses).

If you can’t use greywater for irrigation, investigate options for indoor reuse, such as for toilet flushing, or focus on rainwater catchment or composting toilet systems.

Not enough space for plants and irrigation systems. With a very small (or nonexistent) yard, there may not be enough landscape area to infiltrate greywater.

Too close to a creek or a drinking water well. Setback requirements range from 50 to 100 feet.

Unstable slope. Adding extra water to a steep or otherwise unstable slope could cause a landslide.

Using Greywater Indoors: Toilet Flushing

Flushing the toilet with pure drinking water offends common sense and ecological awareness. Why not flush with non-potable greywater instead? In the right situation, flushing with greywater is a great idea. However, in many situations there are better ideas to implement first. It’s typically cheaper and easier to set up an outdoor greywater irrigation system. It’s also easier to install a rainwater system to flush the toilet than a greywater one. But if your site doesn’t need irrigation, there are systems that filter greywater to flush the toilet.

Challenges with Toilet Systems

Toilet-flushing greywater systems usually require frequent maintenance, manual cleaning of filters, and chemical disinfectant to prevent odors in the bathroom. They also tend to be relatively complicated, and it’s critical that they be designed and installed properly. A few companies sell systems, while some greywater professionals design their own. Studies and system users report that lower-cost systems ($3,000–$5,000) have maintenance issues, while the better-functioning versions have a steep price tag ($8,000–$9,000). In general, it costs far less to purchase an ultra-low-flow toilet and showerhead than invest in a toilet-flushing system.

Getting a permit tends to be more difficult for indoor reuse of greywater, although a few states, such as Florida, make it easier than outdoor reuse. Some tinkerer-types create functional mechanisms for flushing, but these are never up to code. A study on 25 toilet-flushing systems in Guelph, Canada, found an average savings of just 4.5 gallons per person per day (gpcd). Toilets using treated greywater tend to require more maintenance, and internal parts wear out, causing wasteful leaks.

Recommendations

Use shower water first for indoor systems, since it has fewer particles to filter out. You’ll need to access the drainpipes to install the diverter valve, and install a tank with a filter. Lastly, do a reality check to make sure you are ready to do the necessary maintenance for this type of system to function well.

Choosing a Greywater Irrigation System

Greywater is a unique type of irrigation water, distinctly different from rainwater or potable water from the tap. To choose the best greywater system for your situation, you’ll need a basic understanding of how different types of systems work and their advantages and limitations, as well as a clear understanding of your site: the landscape, plumbing configuration, your budget, and how much maintenance will realistically be done to upkeep the system. Much of this information you gathered in chapters 1–5, and the remaining considerations are covered here.

Combine Greywater Sources or Keep Them Separate?

One big consideration is whether to keep the greywater flows separate and install a system for each fixture or to combine the flows together and install one larger system. For example, will you combine the showers with the washing machine greywater or keep them separate? What’s best depends on your situation: the layout of your home, the type of system you want to install, and what types of plants you plan to irrigate. In general, if you are installing a system in your current home and are not doing a major plumbing remodel, it’s most practical and economical to keep the greywater sources separate and build a different system from each fixture. In new home construction, or during big remodels, you could combine flows together and install one larger system.

When Separate Systems Make Sense

- Your house is already built and you don’t want to do extra plumbing work.

- You want a simpler and lower-cost project.

- You plan to use gravity systems for showers/sinks and a laundry-to-landscape system for the washing machine.

- You need irrigation water near the various greywater sources. For example, one shower is close to the front yard, while the washing machine is near the backyard.

- Tip: Even if you combine some flows, consider keeping the washing machine separate. Having a separate valve next to the machine allows you to control the laundry flow without having to shut off the entire system.

When Combining Flows Makes Sense

- You plan to incorporate a pump or filter.

- You want to include fixtures that aren’t used frequently, such as those in a guest bathroom.

- You want multiple irrigation zones. You’ll typically need more than one fixture to generate enough water for multiple irrigation zones.

- Tip: If you plan to reuse your entire household’s greywater and have multiple bathrooms in the home, consider keeping one bathroom off the system. Guests can use that bathroom without sending their own (possibly non-plant-friendly) soaps to your yard, or forcing you to turn off the entire system.

Other Considerations: Permits and Your Existing House

Permits and their requirements are other significant factors. Some types of systems are much easier to get a permit for than others, and many local authorities impose rigid permitting guidelines, which will impact your system design. In addition, most homes and landscapes were not planned with a greywater system in mind, so the best greywater system for your site may not be quite what you originally imagined. You may discover your site presents logistical challenges or your landscape plants aren’t suitable. Being flexible and open to change, particularly landscape changes, will help you find an affordable and suitable system.

Greywater Systems at a Glance

In the upcoming chapters I’ll explain how to design and install four common systems: the landscape-to-laundry (L2L), branched drain, and two pumped systems (both with and without a filter). The Greywater Systems Overview chart below summarizes the costs and capabilities of these systems.

Laundry-to-landscape systems typically are the lowest in cost and easiest to install. Because the installation doesn’t alter the household drainage plumbing the system often doesn’t require a permit.

branched drain systems are gravity-based and require the landscape to be lower than the plumbing; these are best suited for larger plants. They’re very low-maintenance — a great choice for irrigation of trees and bushes.

Pumped systems, both filtered and unfiltered, are designed to move greywater uphill and are capable of spreading the water over large areas. These systems typically are more difficult to get a permit for and may require backflow prevention (see Tankless Pumped System Option). Check with your local building authority, as specific requirements can add significant costs to the system.

Which System to Do First?

A common order of installing systems — for people retrofitting existing homes, as opposed to new construction or major remodels — is to start with the laundry-to-landscape system, then install gravity or pumped systems from the other fixtures. A kitchen sink system requires more frequent maintenance than other sources of greywater due to higher organic matter in the water, so it’s best to include one after the easier-to-maintain systems are installed.

Operation and Maintenance Manual for your Greywater Systems

You will need an Operation and Maintenance (O&M) manual for each greywater system (and most codes require you to have one). This manual includes important information about your greywater system, including:

- What types of soaps and detergents can be used

- When the system should be shut off

- How much greywater it was designed for

- Maintenance requirements

- Basic troubleshooting tips

- A site plan of the system accompanied by photographs of the unburied pipes; this will help you find pipes in the future in case you want to alter the system or plan to do landscape work and don’t want to damage the pipes.

Place the O&M manual in an easy-to-find location, such as inside a plastic sleeve and taped near the diverter valve or greywater fixture (for example, on the side of the washing machine). Show the manual to any house-sitters or house guests, and pass it on to new owners if you sell the house. Some local municipalities, either the city or water district, can provide you with an O&M manual to adapt; or you can download one from the website of a nonprofit such as Greywater Action (see Resources).

When to Turn Off the System

If you have a functional sewer or septic system, it’s easy to turn off your greywater and direct the water to the sewer/septic system. Direct the greywater to the sewer/septic system when:

- Using chlorine bleach, hair dye, harsh cleaners, or other toxic substances

- Using non-plant-friendly products (those high in salts or containing boron)

- Washing to remove toxic or hazardous chemicals from clothing, such as gasoline or paint thinner spilled on your shirt

- Washing diapers or clothing containing fecal matter

- There are puddles in the yard or any visible signs of greywater surfacing (note that some jurisdictions require systems to be shut off at the start of the rainy season)

Call Before You Dig!

Call 811 (or visit www.call811.com) several days before starting a project to find out where your underground utilities are located. The hotline will route your call to your local utility call center. You’ll tell the operator where you’re planning to dig and they’ll notify the utility providers in your area, who in turn will mark any underground utility lines on your property. You can also hire a private locator to find lines inside the property; this might be advisable if you have outbuildings, such as sheds and guest houses, that may be supplied by electrical and water lines from your house but aren’t officially within the purview of utility companies.

In addition to having all utilities marked, it’s up to you to make sure you don’t put a pickax through a buried service line, which could be a deadly mistake. Use extreme caution when working anywhere near buried lines. Or better yet, avoid these areas entirely.

Using Greywater without a System: Tips for Renters and Homeowners

It would be great if all landlords were water-conscious and supported the efforts of their water-wise tenants. Some are, but many still don’t want tenants changing the house, which makes installing a greywater system more challenging. If you’re a homeowner, perhaps you aren’t ready to install a dedicated system or you just want some simple solutions for reusing greywater right away. Following are a few ideas for reusing water without altering the house. Don’t forget to check with your landlord about these projects; they may want to pay for the parts or learn more.

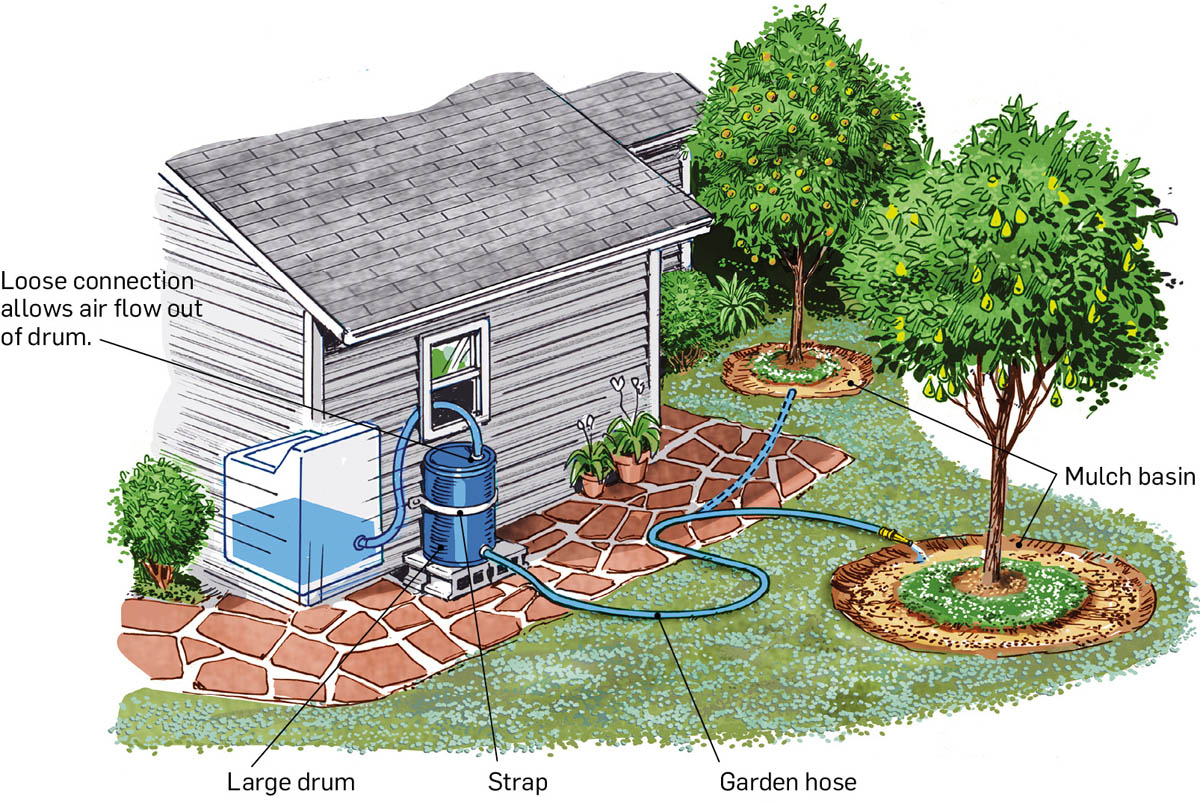

“Laundry Drum” System. Simply stick the hose of the washing machine out a nearby window (nearby window required), drain it into a drum/small tank (about 50 gallons), then connect a garden hose to the bottom of the barrel and move the hose manually to water the plants (see Laundry Drum System). Since greywater can’t be stored you’ll need to use it that day.

Laundry-to-Landscape System With No Hole in the Wall. Attach a piece of wood, such as a 2 × 4, to the bottom of a nearby window and drill through the wood instead of the wall. The window closes against the wood and the pipe exits the house with no holes in the house. Alternatively, if your landlord allows a hole in the floor (and you have a crawl space), drill through the floor and exit the house via a screened crawl space vent.

Outdoor washing machine. Set up your washing machine outside on a covered deck or porch (requires above-freezing temperatures). Connect the machine to an outdoor spigot, and run only cold-water loads (use a washer Y hose to connect cold water to both cold and hot inlets on the machine).

Bucket or siphon. Collecting greywater in buckets builds muscle and provides a visceral awareness of how much water you use. Collect shower greywater by plugging the tub and to bailing out the water, or simply shower over a bucket. And don’t forget to collect the “clear water” while your shower heats up. If the landscape is lower in elevation than your tub, you can siphon the water outside (with a hand pump and garden hose, or a product such as a SiphonAid). Kitchen sink water can be collected in a dishpan in the sink.

Constructing a laundry drum system is similar to converting a 55-gallon barrel into a rain barrel. The key difference is there is no shutoff on the bottom, since greywater should not be stored.

Directly attach a garden hose to the barrel and place the hose in a well-mulched part of the yard near thirsty plants to soak up the greywater. One method to attach the hose is to drill a hole at the bottom of the barrel, just large enough to thread a 3⁄4-inch garden hose adapter or hose bibb into the barrel (use one without a shut-off to prevent accidental overflow of greywater). If you can’t access the inside of the barrel, put a bead of silicone caulk around the hole to prevent leaks.

With access to the inside of the barrel you can more securely attach the fitting by doing the following; wrap pipe thread tape on the male pipe threads of the garden hose adapter or hose bibb, put an O-ring and washer onto the male threads and connect a 3⁄4-inch female-threaded coupling to it, tightening with tongue-and-groove pliers. Put a bead of silicone caulk around the outside and inside to prevent leaks.