CHAPTER VIII

THE TRUNK

THE trunk, as understood by the artist, differs somewhat in its extent from that described by the scientific anatomist.

It will be considered here to include the back, chest, abdomen, and their immediately adjacent parts. The shoulders have been described to some extent (p. 73), but they will be mentioned again now with the trunk. A description of the neck will be found on p. 180.

The back of the trunk (Figs. 19, 20, 62) consists really of two parts—the back of the thorax, and the loins, or back of the abdomen. The distinction between these two regions is not so obvious behind as it is in front, where the chest is marked off from the abdomen by the margin of the ribs; and as these are covered behind by exceedingly thick and strong muscular and ligamentous structures, the last rib is usually completely hidden from sight, and in most subjects is only palpable with difficulty.

The dorsal vertebrœ are those which carry the thorax, while the lumbar vertebrœ support the loins.

The spine, when seen in profile, has been explained in a previous section to be convex backwards in the dorsal region, concave in the lumbar; and these curves contribute much to the elasticity, and therefore to the strength, of the back. There is no visible line of demarcation between these two curves or regions.

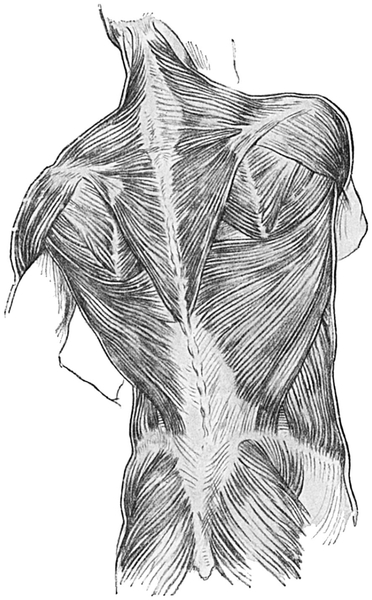

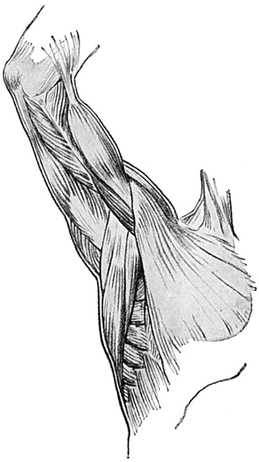

Fig. 62.—The Muscles on the Back of the Trunk, Buttock, and Neck.

A prominent feature of the back is the deep furrow which extends in the middle line for nearly its whole length (see Plates). The depth of this furrow is caused by the large mass of the erector spinæ muscle which projects on each side of it, and gradually increases in width but diminishes in prominence as it is traced upwards. At the upper part of the buttocks the furrow gives place to a slightly depressed flat area, to which again there succeeds the deep and narrow furrow which separates the two buttocks and passes forwards into the perineum.

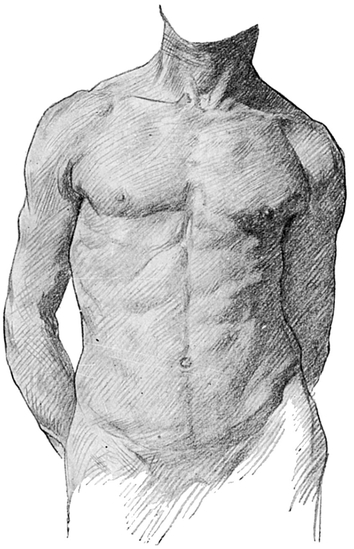

Fig. 63.—The Muscular Prominences on the Front of the Trunk and Neck.

The furrow is deepest below the middle of the back. If the distance from the lowest part of the back of the neck—i.e. at the level of the seventh cervical vertebra, or vertebra prominens—be measured to the termination of the furrow between the buttocks and divided into fifths, it will be found that the deepest part of the furrow lies in the third and fourth fifths, counting from above.

This increased depth of the furrow is due to two causes: first, to the concavity of the vertebral column, which in this region is directed backwards; secondly, to the great height of the sides of the furrow. The sides are formed by the powerful and prominent mass of muscle lying on each side of the middle line, known as the erector spinœ, a name which sufficiently explains its action. In the dorsal region the backward projection of the ribs makes the erector spinæ prominent, and so accentuates the furrow.

At the bottom of this median furrow all the projecting spines of the dorsal and lumbar vertebræ can either be felt or seen.

The first dorsal vertebra lies immediately below the vertebra prominens (the seventh cervical), and its spine is the most prominent of any. All the spines can be seen more clearly when the back is bent and the distance between each one is thus slightly increased. It can then be noticed that the dorsal spines are single processes, unlike those of the cervical region, which are double. Frequently, especially in wasted subjects, circles of superficial veins may be seen around the spines.

When the back is straightened it is not unusual or abnormal for a slight side-to-side curve to be demonstrable in the dorsal region, the convexity of which is, except in left-handed subjects, directed to the right. This curve is the result of the greater development of the muscles of the right side, in association with the freer and stronger movements of the right upper extremity in connection with right-handedness.

In left-handed persons the curve is found in the opposite direction. Since the normal slight curve is produced by muscular over-development, it naturally is the rule for it to be more pronounced in men than women, but its exaggeration owing to weakness or disease is more common in women.

The art student will do well to remember that such a lateral curve may develop as a result of tilting of the pelvis, e.g. when the subject is standing on one leg. It may also be pointed out that any lateral curve in the dorsal spine must present also some prominence of the shoulder-blade on the convex side.

It is important to notice that although the posterior convexity of the dorsal region of the back is much increased when the body is bent forwards, it never entirely disappears, even in the most erect Guardsman. Any apparent diminution of the curve as the erect position is assumed is due to an increase in the lumbar concavity backwards and to hyperextension of the hip-joint.

Note also that although the lumbar vertebræ number only five to the dorsal vertebræ twelve, the former are so much larger individually that the lumbar portion measures nearly two-fifths of the total length of the back, and the dorsal portion only the remaining three-fifths.

The erector spinæ muscle, which forms a thick mass below, where it is attached to the iliac crest, breaks up above into numerous smaller portions which go to the vertebræ and ribs. Marked projections on each side of the middle line are formed by two comparatively thin sheets of muscle which lie superficial to the erector spinæ, passing from the trunk to the upper limb. The lower of the two is the latissimus dorsi; the one lying above is the trapezius (Fig. 62). The trapezius forms also a conspicuous landmark in the neck, which will be described in a later section. The lower two-thirds of the trapezius belong to the thorax, and this portion passes from the dorsal region of the spinal column, where it is attached to the spines of all the dorsal vertebræ. The cervical and dorsal parts of this triangular sheet of muscle converge upon, and are attached to, the concavity of the horseshoe of bone which is formed by the clavicle and the spine of the scapula (Figs. 21, 23).

The lower fibres of the trapezius are more vertical than those in the middle of the triangular sheet of muscle. They form a straight edge, passing from the spine of the lowest dorsal vertebra to the root of the spine of the scapula, which is on a level with the third dorsal vertebra.

In the middle line of the back the origins of the two trapezius muscles are separated only by the line of spinous processes, so that the two triangles form together a diamond-shaped sheet under the skin, which from its position, size, and shape has been likened to a collapsed monk’s hood; hence the alternative name of the “musculus cucullaris.”

The latissimus dorsi (Fig. 62, p. 159) is a muscle of great importance, and has a large share in pulling the body after the arm as in the act of climbing. It has three visible edges when in action—inner, upper, and outer. By the inner border it arises from the spine opposite the lumbar and the lower six dorsal vertebræ. The upper border emerges from under cover of the trapezius in such a direction that it is curved with its concavity upwards. The lower border passes upwards and outwards from the back part of the crest of the ilium, and the two latter borders converge upon one another so that the muscle eventually forms a comparatively narrow thick band, the upper part of which overlaps the lower angle of the shoulder-blade. It then winds in a spiral manner round a thick muscle, only to be identified in muscular subjects, the teres major, and with it forms the thick and rounded posterior fold of the axilla or armpit (Fig. 24).

Between the outer or lowest borders of the trapezius, the upper border of the latissimi dorsi, and the inner border of the scapula, a triangular interval is formed which lies over a portion of the space between the sixth and seventh ribs. The floor of this triangle is formed by a flat muscle called the rhomboideus major (Fig. 62).

External to the inner border of the scapula, and below its spine, two thick muscles with a dividing groove may be seen in muscular subjects, passing under the posterior border of the deltoid muscle. The upper one is the infra-spinatus, and the lower the teres major. The teres major conceals the scapular head of the triceps from view.

Just as in connection with the upper border of the latissimus dorsi a triangular interval is displayed between it and the muscle which lies above and internal to it, viz. the trapezius, so frequently there is to be observed another but much smaller triangular space between it and the muscle lying below and external to it on the abdominal side, which is the external oblique. The edges of this triangle, only demonstrable on dissection, are bordered by the latissimus dorsi internally, the external oblique externally, and by the crest of the ilium below. The triangle is floored by the internal oblique.

The external oblique muscle forms a distinct prominence upon the lateral part of the small of the back, which is concealed, however, by the latissimus dorsi in its upper part. In a very muscular subject the origin of the external oblique from the lowest ribs may appear in digitations, one arising from each rib.

All these muscles of the back produce hardly any prominence in persons who are well covered with fat, as, being flat sheets, their outlines may be completely obscured by the more superficial coverings.

Only in a very emaciated subject can the ribs be seen on the back, and there is difficulty even in feeling them clearly enough to count them. Their convexity makes the erector spinæ prominent on each side of the furrow in the middle line.

Frequently, in persons who are well covered with fat, the only obvious landmark in the general convexity of the back is the median furrow. In such cases the back forms a gentle uninterrupted curve on each side of the furrow.

In muscular subjects a further groove may be noticed, which is directed round the side of the body from the lower part of the lumbar spinal furrow. The groove separates the loins and abdomen above from the buttocks below, and is replaced in thin persons by a slightly sinuous ridge. In fat persons neither groove nor ridge can be detected. The ridge is due to the presence of the crest of the ilium, which is the expanded wing of the pelvis; the groove, when present, arises from the massing of muscles above and below it.

Anteriorly the groove is traceable into the deep cruro-scrotal fold, and as it runs forwards it lies a little below Poupart’s ligament. Note that the groove is somewhat curved, and more horizontal than Poupart’s ligament.

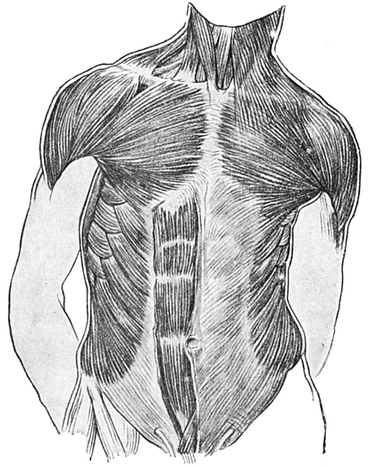

Fig. 64.—The Muscles on the Front of the Trunk and Neck.

In either case, whether ridge or groove, it may be traced posteriorly by the fingers into a slight elevation on the innominate bone, known as the posterior superior spine of the ilium (Fig. 62, p. 158), which in nearly all cases lies at the bottom of a dimple or depression in the skin. The situation of the dimple is an inch and a half from the middle line, and a little above the prominence formed by the spine of the fourth sacral vertebra, which is the last spine of the vertebral column to be seen or felt.

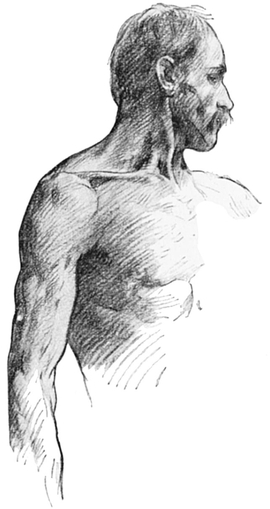

Fig. 65.—Muscular and Bony Surface Markings of Side of Neck, Trunk, and Arm.

When the crest of the ilium is traced forwards from this dimple round the side of the body, it is found to become thickened into a tubercle which marks the highest part of the crest. Some two or three inches farther forward the crest terminates a little below its highest level in the large and conspicuous bony prominence of the anterior superior spine of the ilium (Figs. 8, 9, 44).

Laterally, between the last rib and the crest of the ilium, the ilio-costal space is unsupported by bone. The height of this space varies much, according to the stature of the subject, but perhaps two or three inches is the average measurement from the tip of the rib to that portion of the crest of the ilium which lies immediately below it. Here lies the narrowest part of the body, the true waist (Fig. 103).

The chief superficial landmarks of the back have now been mentioned, and attention must next be directed to the side of the body (Fig. 65).

In order that as many points as possible may be studied, it is better for the student to raise the arm of the subject from the side. It will be observed that the armpit lies at the highest level of the side of the trunk. The skin is here covered with numerous coarse hairs, and is often moist, owing to the secretion of perspiration (Fig. 66).

But the armpit is not only the highest part of the side of the trunk, it is also the narrowest. This is because it is encroached upon by two large muscular masses, viz. the pectoralesforming the anterior “fold of the axilla,” the latissimus dorsi and teres major forming the “posterior fold.” The side gradually increases in breadth below the armpit as the ribs which support it become longer, and as these muscular folds of the axilla diverge forwards and backwards.

Fig. 66.—The Muscles of the Inner Surface of the Arm and of the Armpit.

Most of the ribs can easily be felt on the side of the chest even in the fattest, and they lie at the bottom of furrows between well-marked digitations of certain muscles. Although there are twelve ribs, only those between the fourth and the tenth (and exceptionally the eleventh) can be seen on the side. The upper three lie so deeply covered by muscles and bones that they cannot be seen; the twelfth is not long enough to reach the side. The muscles which produce the inter-digitating prominences on the side are the serratus magnums above, and the external oblique of the abdomen below.

There is a distinct decrease in the breadth of the side below the level of the tenth rib, except in prominent abdomens.

The groove or ridge which separates the side of the body from the region of the hip has been described on p. 164. In front of this ridge the lower part of the abdomen is rather more prominent than the portion which lies above it; below and behind the prominence of the buttocks is obvious.

The Front of the Trunk (Figs. 63 and 64).—The lateral parts of the front view of the body pass insensibly into the side view which has just been described. Above, however, the bony ridge produced by the horizontally lying clavicle clearly marks off the trunk from the neck, and below, the front of the body is very obviously demarcated from the thighs and the pubic region by three surface markings from without inwards, viz.:—

1. The crest of the ilium, which terminates in front in the anterior superior spine.

2. Poupart’s ligament, underlying the slight groove of the fold of the groin, which is more horizontal in the female than in the male, and relatively more pronounced when the abdomen is protuberant, passing downwards and inwards from the anterior superior spine.

3. The spine of the pubes. This bony prominence can be felt, but cannot be seen, one and a quarter inches from the middle line which here is formed by the symphysis of the pubic bones. Poupart’s ligament is a very important structure, for to it many muscles are attached.

Between the clavicles above and Poupart’s ligament below, the front of the body (even in fat persons) is obviously divided into two parts by the margin of the thorax. The chest or thorax is the part of the body which is surrounded on all sides by a bony framework; the abdomen or belly lies below it, and is surrounded for the most part by soft structures only.

The clavicles form well-defined ridges which approach closely to each other in the middle line, but without meeting. Between the prominent inner ends of the clavicles there is a deep depression, which, as it lies above the breast-bone, is called the supra-sternal fossa. It is very deep and conspicuous, the two tendinous heads of the sterno-mastoid muscles converging as they bound it laterally. In its depth the main vessels of the neck and limb diverge from each other, occasionally allowing pulsation to be observed in the fossa. The windpipe also lies very deeply at the bottom of the hollow, and here, or a little higher, it is opened in the frequent operation of tracheotomy (Fig. 68).

Below the supra-sternal fossa is the sternum. Its borders, which are separated by a space of, roughly, two inches, are overlaid by the long margin of origin, in muscular subjects somewhat knotted, of a large fan-shaped muscle passing to the arm, and called the pectoralis major (Fig. 64, p. 165). This origin extends from the clavicle to the seventh rib, and is a little arched, presenting a convexity towards the middle line, and leaving rather more of the anterior surface of the sternum exposed in its upper and lower than in the intermediate parts.

Indeed, in muscular subjects the area left between the prominent muscles of the two sides may ampunt to little more than a deep median groove at the level of the second and third ribs, though more expanded above and below.

When a skeleton is examined in profile it is seen that the sternum does not lie in a purely vertical plane. It not only slopes decidedly forwards, as it is traced downwards, but it is also bent so as to present a curved surface, or rather two surfaces, inclined at an angle to each other. This “sternal angle” is the most prominent part of the bone; it is situated at the level of the second rib, two inches below the supra-sternal fossa, and is continued on each side into the ridge produced by the second rib, the most easily identified of all the ribs, and therefore the one from which any enumeration of the ribs should be made. The first rib lies deeply beneath the clavicle in such a way that it can neither be seen nor easily felt.

Above this projecting sternal angle lies the expanded part of the median groove, already described as separating the two pectoral muscles, and supported by the upper portion of the sternum or manubrium.

The second part of the sternum which lies below the angle is called the gladiolus; it is more than twice as long as the part above it. It extends downwards, with a distinct inclination forwards, until it reaches the level of the seventh costal cartilage. At this level the bone is somewhat expanded.

Below this second part of the sternum, in what is popularly known as the “pit of the stomach,” called by anatomists the infra-sternal fossa, is the somewhat recurved ensiform cartilage, which forms the lower end of the sternum. Its point may occasionally be distinctly projected forwards; it is always much narrower than the rest of the sternum.

Below the infra-sternal fossa a groove occupies the centre of the body, fading away as it approaches the pubic bone. It lies between the two wide straplike muscles, the recti abdominis. The linea alba, a strong fibrous band, supports the groove, which is broken in its line by the umbilicus, or navel, the pitted scar of the vascular cord which connected the mother and the fœtus in utero.

This scar lies a little below the centre of a line drawn from the infra-sternal fossa to the symphysis pubis, or junction of the two pubic bones. It is a circular, and usually depressed, area, with the surrounding skin raised and wrinkled, and it lies opposite the disc between the third and fourth lumbar vertebræ. Some hair may be found in the course of the middle line, even quite high up; this fact will be referred to later.

Three muscles should next be studied on each side of the middle line, viz. the pectoralis major, serratus magnus, and rectus abdominis (Figs. 63 and 64, pp. 159, 165, and Plates).

The pectoralis major is large and fan - shaped, converging from a wide origin from the inner half of each clavicle and from the margin of the sternum (Fig. 64), which it frequently obscures, to its narrow insertion into the upper part of the arm. The clavicular and sternal parts are separated by a groove which is nearly as distinct as that which separates the adjacent borders of the deltoid and pectoralis major (Fig. 64). Sometimes the groove is not easy to identify, but even then the clavicular part of the muscle may be distinguished from the sternal. If the subject be instructed to lift the outstretched arm against some resistance, the clavicular portion will be noticed to stand out. If, on the contrary, he be instructed to depress the outstretched arm against resistance, the lower or sternal part will be put into action, and will become prominent.

There is a groove between the upper margin of the pectoralis major and the deltoid. The inner end of this groove opens out just below the clavicle into a depression known as the infra-clavicular fossa (Fig. 64, p. 165). Immediately below and external to the lower margin of the pectoralis major may be observed the lower digitations of the serratus magnus, and the upper digitations of the external oblique muscle. The serratus magnus pulls the scapula forwards, and is thus used in stretching out the arm, as in shaking hands.

The rectus abdominis is the flat muscle lying upon each side of the middle line of the abdomen, and its effect upon the surface form of the abdomen is great. Even in fat persons it forms a definite ridge when in action. Its upper limit stretches as high as the fifth rib, close to the sternum, and here the muscle is somewhat narrower. Tracing it down, as it reaches the sixth and seventh ribs it widens, and continues of the same breadth until a point is reached a little below the umbilicus, whence it rapidly tapers to its lower end, which is quite narrow, on the front of the pubic bone. The narrowing of the lower part of the muscle is brought about by the incurving of its outer edge.

There are three or four horizontal lines, or rather grooves, dividing it into several parts or segments. The grooves lie in very constant positions—one at the level of the umbilicus, one at the level of the ensiform cartilage, and another midway between these points. Sometimes also a groove may be seen dividing the portion of muscle which lies below the navel into two nearly equal parts.

In the muscular subject, therefore, the rectus abdominis forms a very striking object. The inner edge is not so prominent as the outer border, which is known as the linea semi-lunaris, owing to the marked curving towards the middle line, below the umbilicus, already noted. There is an inclination on the part of some artists to make the rectus a little too broad, and to accentuate rather much the prominence of its individual segments, and it is not very rare to see too many segments of this muscle and of the serratus magnus depicted, especially in sculpture.

The rectus acts by drawing the chest and pelvis together, and in forcible bending forwards of the body its shape and actions may be demonstrated. It has other important functions; it helps to keep the viscera in position, and, like the pectoralis major and the serratus magnus, it is an accessory muscle of respiration. The linea alba is sometimes stretched to such a degree, especially in fat women, that the two recti become widely separated.

The vertical height of the chest wall is greater behind than in front; the abdominal wall, on the contrary, is more extensive in front than at the sides and back. The chest contains the heart and lungs, and other important structures, protected by the dorsal vertebræ, ribs, and sternum. The abdomen contains the alimentary canal and its great glands the liver and pancreas, the urinary and the genital viscera (with the exception of the testicle and a part of its duct, which are contained in the scrotum), but they have no bony protection in front and at the sides. Both cavities also contain many large blood-vessels and nerves.

These two great cavities of the body are well adapted for their several purposes.

Respiration chiefly depends upon the action of the diaphragm, the thin dome-shaped muscular sheet intervening, inside the body, between the chest and abdomen. This muscle cannot be seen without deep dissection, but it produces such an effect upon the general shape of the chest and abdomen that it must be mentioned here. A series of little muscles essential to the full action of respiration must also be described, viz. the intercostals, which line and pass between the adjacent ribs.

When the diaphragm contracts, its dome becomes flatter and less rounded, with the result that the capacity of the chest, whose floor it forms, is increased and air rushes in through the windpipe to fill the cavity. The abdominal viscera are at the same time pushed downwards, thus producing a bulging of the abdomen. This type of respiration, “the abdominal type,” occurs in both sexes, but is especially deep in men.

The little intercostal muscles raise and evert the ribs, and again the chest capacity is increased and air inspired. This “costal type” of breathing is more marked, in women.

We have seen that the costal margin indicates the boundary line between chest and abdomen, and forms an obvious landmark on the front surface of the body, and that only the seven upper ribs articulate with the sternum by means of their cartilaginous ends. The eighth, ninth, and tenth ribs articulate with the cartilage which lies immediately above each of them.

The costal margin may be traced, either by sight or by palpation, from the sternum to the vertebral column. Near the middle line of the sternum the seventh costal cartilage passes downwards and outwards from the expanded part of that bone which lies just above the infra-sternal fossa. This part of the costal margin is a little curved, so as to present a convexity pointing inwards and downwards. Below this the margin is directed outwards and downwards along a line which has a slight concavity open inward and downward; this part of the costal margin corresponds to the eighth, ninth, and tenth costal cartilages. If a vertical line be dropped from the middle point of the clavicle, it passes through the junction of the eighth and ninth costal cartilages.

The tenth cartilage is the lowest part of the costal margin, and lies at the side of the body. From it the costal edge passes upwards and backwards along the eleventh and twelfth ribs to the last dorsal vertebra.

The last two ribs can only be felt with difficulty, and are very rarely visible through the skin. They are called “floating ribs,” because they do not join up by their tips with the cartilage of the rib above.

The greatest transverse diameter of the thorax lies between the seventh, eighth, and ninth ribs.

The tenth, eleventh, and twelfth ribs are separated by rather narrower intercostal spaces than the others.

Owing to the obliquity of the first rib, the upper aperture of the barrel-like thorax, or chest cavity, slopes from the sternum upwards and backwards, the supra-sternal fossa lying opposite the cartilaginous disc between the second and third dorsal vertebræ, some two inches lower than the first dorsal, which bounds the aperture behind.

Although the ribs are the support of the thoracic or chest wall, it is clear that the greater breadth of the upper part of the trunk cannot be due to them; for the first rib is quite short, and the length of the ribs increases from above downwards till the seventh is reached. The greater width at the top of the trunk is, in fact, entirely the result of the length of the clavicle.

The function and formation of the chest having now been briefly explained, the student’s attention should be turned to the position of the nipples. They lie one on each side of the middle line. In the male they are little pigmented nodules, surrounded by a pinkish area, and raised upon a somewhat elevated base from the general surface of the chest. They lie in the fourth intercostal space, four inches from the middle line.

Very different is the appearance of this part in the female. In the adults of this sex the nipple is much larger, and surmounts a large prominent mass known as the breast, which contains the milk-secreting “mammary” gland, embedded in a layer of fat which varies enormously in different individuals.

The female nipple has a less uniform position on the front of the chest, as the breast is very often pendulous, and so the nipple may hang considerably below the fourth intercostal space.

The fat which is present around the breast is responsible for the gentle curves of this part. Each breast lies upon the pectoralis major and the serratus magnus, two-thirds upon the former and one-third upon the latter muscle.

The nipple is light brown in colour in the virgin, in whom it is surrounded by a pink areola. The nipple becomes browner and the areola more pigmented in the pregnant woman, and these tints remain in the matron.

The saucer-shaped mammary gland extends from the level of the second as far as the sixth rib, and from the margin of the sternum to the anterior fold of the axilla. These limits are the boundaries of the actual mammary gland when fully developed, but in the young it is less extensive, and in the old it is usual for it to become much smaller, though in both the young and the old there may be such a development of fat as to make the breast appear large.

Blue lines, which mark the presence of veins, may be seen on the surface of the fully developed breast, and these become much larger during pregnancy and lactation.

Notice that the shape of the breast varies not only with its consistence, but with the position of the trunk, and even with the position of the arm.

Notice also that while the nipple is in the middle of the breast, the contour of the upper half of the organ is less convex than the lower half, which makes with the chest wall a well-marked thoraco-mammary fold (Plates X., XVIII., XXIII., XXXI.).

The abdomen is usually, even in muscular men, rather more prominent in its lower than in its upper part. In women who have borne children a change is demonstrable in the skin throughout the lower part of the abdomen. Numerous pink, silvery lines are seen. In the old the lines become distinctly brown and pigmented, and are known as “lineœ atrophicœ.”

The abdomen is apt to increase in size with advancing age, especially in elderly and sedentary men. This is the consequence of a great increase of fat, which causes the protuberant abdomen to hang downwards over the upper part of the thighs.

Three layers of muscle-sheets support the abdomen, viz. the external and internal oblique, and the transversalis. They are so arranged that their fibres cross each other, thereby adding very greatly to the strength of the abdominal wall.

The external oblique muscle is a flat sheet on the side of the abdomen. The anterior limit of its muscular portion is prominent along a curved line, slightly convex towards the middle of the body, and nearer to the middle at the level of the costal margin, than below, where again it is very obvious just above and in front of the anterior superior spine of the ilium. Therefore its aponeurosis or spread-out tendon is broader below than above (Plate XVI.).

Just above the two pubic bones, the lower limit of the abdominal wall contains a pad of fat, which is covered with hair and marked off from the abdominal wall just above by a well-marked furrow in the skin, not quite transverse, but concave upwards. In the fat subject a similarly disposed furrow crosses at the umbilicus (Plate X.).

The hair upon the front of the trunk varies much in amount. The pubic hair extends up the middle line towards the umbilicus.