KNOWLEDGE GOALS

To understand how the Boolean operators work.

To understand how the Boolean operators work.

To understand the flow of control in a branching statement.

To understand the flow of control in a branching statement.

To understand the flow of control in a nested branching statement.

To understand the flow of control in a nested branching statement.

To know what preconditions and postconditions are.

To know what preconditions and postconditions are.

Conditions, Logical Expressions, and Selection Control Structures

KNOWLEDGE GOALS

To understand how the Boolean operators work.

To understand how the Boolean operators work.

To understand the flow of control in a branching statement.

To understand the flow of control in a branching statement.

To understand the flow of control in a nested branching statement.

To understand the flow of control in a nested branching statement.

To know what preconditions and postconditions are.

To know what preconditions and postconditions are.

SKILL GOALS

To be able to:

Construct a simple logical (Boolean) expression to evaluate a given condition.

Construct a simple logical (Boolean) expression to evaluate a given condition.

Construct a complex logical expression to evaluate a given condition.

Construct a complex logical expression to evaluate a given condition.

Construct an If-Then-Else statement to perform a specific task.

Construct an If-Then-Else statement to perform a specific task.

Construct an If-Then statement to perform a specific task.

Construct an If-Then statement to perform a specific task.

Construct a set of nested If statements to perform a specific task.

Construct a set of nested If statements to perform a specific task.

Trace the execution of a C++ program.

Trace the execution of a C++ program.

Test and debug a C++ program.

Test and debug a C++ program.

So far, the statements in our programs have been executed in their physical order. The first statement is executed, then the second, and so on, until all of the statements have been executed. But what if we want the computer to execute the statements in some other order? Suppose we want to check the validity of input data and then perform a calculation or print an error message, but not both. To do so, we must be able to ask a question and then, based on the answer, choose one or another course of action.

The If statement allows us to execute statements in an order that is different from their physical order. We can ask a question with it and do one thing if the answer is yes (true) or another thing if the answer is no (false). In the first part of this chapter, we deal with asking questions; in the second part, we deal with the If statement itself.

5.1 Flow of Control

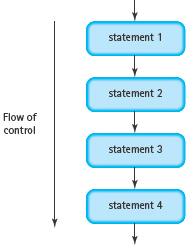

The order in which statements are executed in a program is called the flow of control. In a sense, the computer is under the control of one statement at a time. When a statement has been executed, control is turned over to the next statement (like a baton being passed in a relay race).

Flow of control The order in which the computer executes statements in a program.

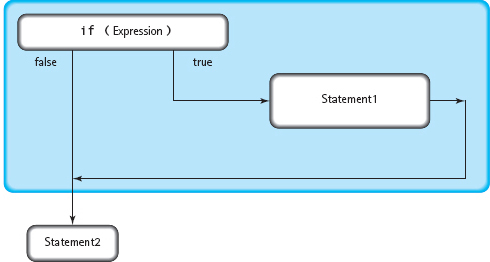

Flow of control is normally sequential (see FIGURE 5.1). That is, when one statement is finished executing, control passes to the next statement in the program. When we want the flow of control to be nonsequential, we use control structures, special statements that transfer control to a statement other than the one that physically comes next. Control structures are so important that we focus on them in the remainder of this chapter and in the next four chapters.

Control structure A statement used to alter the normally sequential flow of control.

Selection

We use a selection (or branching) control structure when we want the computer to choose between alternative actions. Within the control structure, we make an assertion—a claim that is either true or false. We commonly refer to this assertion as the branching condition. If the assertion is true, the computer executes one statement. If it is false, it executes another (see FIGURE 5.2). The computer’s ability to solve practical problems is a product of its ability to make decisions and execute different sequences of instructions.

The LeapYear program in Chapter 1 shows the selection process at work. The computer must decide whether a year is a leap year. It does so by testing the assertion that the year is not divisible by 4. If the assertion is true, the computer follows the instructions to return false, indicating that the year is not a leap year. If the assertion is false, the computer goes on to check the exceptions to the general rule. In Chapter 1, we said that this construct is like a fork in a road.

FIGURE 5.1 Flow of Control

FIGURE 5.2 Selection (Branching) Control Strucuture

Before we examine selection control structures in C++, let’s look closely at how we get the computer to make decisions.

QUICK CHECK

5.1.1 What does “flow of control” mean? (p. 186)

5.1.2 What is the “normal” flow of control for a program? (p. 186)

5.1.3 What control structure do we use when we want a computer to choose between alternative actions? (p. 186)

5.1.4 What does a branch allow the computer to do? (pp. 186–187)

5.2 Conditions and Logical Expressions

To ask a question in C++, we don’t phrase it as a question; we state it as an assertion. If the assertion we make is true, the answer to the question is yes. If the statement is not true, the answer to the question is no. For example, if we want to ask, “Are we having spinach for dinner tonight?” we would say, “We are having spinach for dinner tonight.” If the assertion is true, the answer to the question is yes. If not, the answer is no.

So, asking questions in C++ means making an assertion that is either true or false. The computer evaluates the assertion, checking it against some internal condition (the values stored in certain variables, for instance) to see whether it is true or false.

In C++, the bool data type is a built-in type consisting of just two values, the constants true and false. The reserved word bool is short for Boolean (pronounced “BOOL-e-un”).1 Boolean data is used for testing conditions in a program so that the computer can make decisions (with a selection control structure).

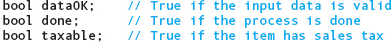

We declare variables of type bool in the same way we declare variables of other types—that is, by writing the name of the data type and then an identifier:

Each variable of type bool can contain one of two values: true or false. It’s important to understand right from the beginning that true and false are not variable names and they are not strings. They are special constants in C++ and, in fact, are reserved words.

Logical Expressions

In programming languages, assertions take the form of logical expressions (also called Boolean expressions). Just as an arithmetic expression is made up of numeric values and operations, so a logical expression is made up of logical values and operations. Every logical expression has one of two values: true or false.

Here are some examples of logical expressions:

A Boolean variable or constant

A Boolean variable or constant

An expression followed by a relational operator followed by an expression

An expression followed by a relational operator followed by an expression

A logical expression followed by a logical operator followed by a logical expression

A logical expression followed by a logical operator followed by a logical expression

Let’s look at each of these in detail.

Boolean Variables and Constants

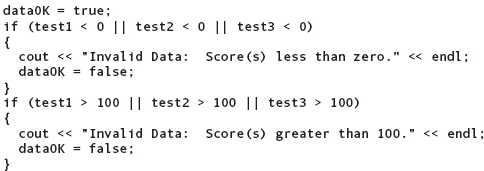

As we have seen, a Boolean variable is a variable declared to be of type bool, and it can contain either the value true or the value false. For example, if dataOK is a Boolean variable, then

dataOK = true;

is a valid assignment statement.

Relational Operators

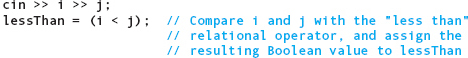

Another way of assigning a value to a Boolean variable is to set it equal to the result of comparing two expressions with a relational operator. Relational operators test a relationship between two values.

Let’s look at an example. In the following program fragment, lessThan is a Boolean variable and i and j are int variables:

By comparing two values, we assert that a relationship (such as “less than”) exists between them. If the relationship does exist, the assertion is true; if not, it is false. We can test for the following relationships in C++:

Operator |

Relationship Tested |

== |

Equal to |

!= |

Not equal to |

> |

Greater than |

< |

Less than |

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

<= |

Less than or equal to |

An expression followed by a relational operator followed by an expression is called a relational expression. The result of a relational expression is of type bool. For example, if x is 5 and y is 10, the following expressions all have the value true:

x != y

y > x

x < y

y >= x

x <= y

If x is the character 'M' and y is 'R', the values of the expressions are still true because the relational operator <, used with letters, means “comes before in the alphabet,” or, more properly, “comes before in the collating sequence of the character set.” For example, in the widely used ASCII character set, all of the uppercase letters are in alphabetical order, as are the lowercase letters, but all of the uppercase letters come before the lowercase letters. So

'M' < 'R'

and

'm' < 'r'

have the value true, but

'm' < 'R'

has the value false.

Of course, we have to be careful about data types when we compare things. The safest approach is to always compare ints with ints, floats with floats, chars with chars, and so on. If you mix data types in a comparison, implicit type coercion takes place, just as it does in arithmetic expressions. If an int value and a float value are compared, the computer temporarily coerces the int value to its float equivalent before making the comparison. As with arithmetic expressions, it’s wise to use explicit type casting to make your intentions known:

someFloat >= float(someInt)

If you compare a bool value with a numeric value (probably by mistake), the value false is temporarily coerced to the number 0, and true is coerced to 1. Therefore, if boolVar is a bool variable, the expression

boolVar < 5

yields true because 0 and 1 are both less than 5.

Until you learn more about the char type in Chapter 10, be careful to compare char values only with other char values. For example, the comparisons

'0' < '9'

and

0 < 9

are appropriate, but

'0' < 9

generates an implicit type coercion and a result that probably isn’t what you expect.

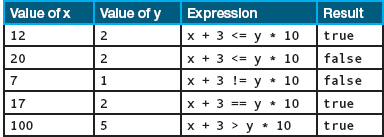

We can use relational operators not only to compare variables or constants, but also to compare the values of arithmetic expressions. In the following table, we compare the results of adding 3 to x and multiplying y by 10 for different values of x and y.

Caution: It’s easy to confuse the assignment operator (=) and the == relational operator. These two operators have very different effects in a program. Some people pronounce the relational operator as “equals-equals” to remind themselves of the difference.

The following program shows the output from comparing five sets of integer values.

What are those 1s and 0s? C++ stores true as the value 1 and false as the value 0. Later in the chapter, we will show you how to convert the numbers 1 and 0 to the words “true” and “false”.

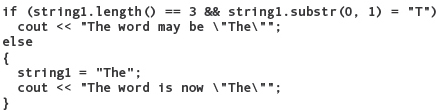

Comparing Strings

In C++, the string type is an example of a class—a programmer-defined type from which you declare variables that are called objects. Recall that C++ is an object-oriented language. Contained within each string object is a character string. The string class is designed such that you can compare these strings using the relational operators. Syntactically, the operands of a relational operator can either be two string objects, as in

myString < yourString

or a string object and a C string, as in

myString >= "Johnson"

However, both operands cannot be C strings.

Comparison of strings follows the collating sequence of the machine’s character set (ASCII, for instance). When the computer tests a relationship between two strings, it begins with the first character of each string, compares those characters according to the collating sequence, and if they are the same repeats the comparison with the next character in each string. The character-by-character test proceeds until either a mismatch is found or the final characters have been compared and are equal. If all their characters are equal, then the two strings are equal. If a mismatch is found, then the string with the character that comes before the other is the “lesser” string.

For example, given the statements

string word1;

string word2;

word1 = "Tremendous";

word2 = "Small";

the relational expressions in the following table have the indicated values.

Expression |

Value |

Reason |

word1 == word2 |

false |

They are unequal in the first character. |

word1 > word2 |

true |

'T' comes after 'S' in the collating sequence. |

word1 < "Tremble" |

false |

Fifth characters don't match, and 'b' comes before 'e'. |

word2 == "Small" |

true |

They are equal. |

"cat" < "dog" |

Unpredictable |

The operands cannot both be C strings.2 |

In most cases, the ordering of strings corresponds to alphabetical ordering. But when strings have mixed-case letters, we can get nonalphabetical results. For example, in a phone book we expect to see Macauley before MacPherson, but the ASCII collating sequence places all uppercase letters before the lowercase letters, so the string "MacPherson" compares as less than "Macauley". To compare strings for strict alphabetical ordering, all the characters must be in the same case. In a later chapter we show an algorithm for changing the case of a string.

If two strings with different lengths are compared and the comparison is equal up to the end of the shorter string, then the shorter string compares as less than the longer string. For example, if word2 contains "Small", the expression

word2 < "Smaller"

yields true, because the strings are equal up to their fifth character position (the end of the string on the left), and the string on the right is longer.

QUICK CHECK

5.2.1 What are the two values that are the basis for Boolean logic? (p. 188)

5.2.2 Write a Boolean expression that is true when the value of the variable temperature is greater than 32. (pp. 188–190)

5.2.3 In C++, how many values does the bool data type consist of? (p. 188)

5.2.4 What is a logical expression made up of? (p. 188)

5.2.5 What are possible values for x and y such that the following boolean expression evaluates to false? (pp. 188–190)

(x + 3) * 2 <= x * (y − 5)

5.3 The If Statement

Now that we’ve seen how to write logical expressions, let’s use them to alter the normal flow of control in a program. The If statement is the fundamental control structure that allows branches in the flow of control. With it, we can ask a question and choose a course of action: If a certain condition exists, then perform one action, else perform a different action.

At run time, the computer performs just one of the two actions, depending on the result of the condition being tested. Yet we must include the code for both actions in the program. Why? Because, depending on the circumstances, the computer can choose to execute either of them. The If statement gives us a way of including both actions in a program and gives the computer a way of deciding which action to take.

FIGURE 5.3 If-Then-Else Flow of Control

The If-Then-Else Form

In C++, the If statement comes in two forms: the If-Then-Else form and the If-Then form. Let’s look first at the If-Then-Else. Here is its syntax template:

If Statement (the If-Then-Else form)

The expression in parentheses can be of any simple data type. Almost without exception, it will be a logical (Boolean) expression; if not, its value is implicitly coerced to type bool. At run time, the computer evaluates the expression. If the value is true, the computer executes Statement1A. If the value of the expression is false, it executes Statement1B. Statement1A often is called the then-clause; Statement1B, the else-clause. FIGURE 5.3 illustrates the flow of control of the If-Then-Else. In the figure, Statement2 is the next statement in the program after the entire If statement.

Notice that a C++ If statement uses the reserved words if and else but does not include the word then. We use the term If-Then-Else because it corresponds to how we say things in English: “If something is true, then do this, else do that.”

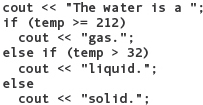

The following code fragment shows how to write an If statement in a program. Observe the indentation of the then-clause and the else-clause, which makes the statement easier to read. Also notice the placement of the statement following the If statement.

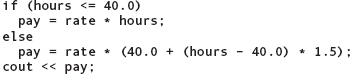

In terms of instructions to the computer, this code fragment says, “If hours is less than or equal to 40.0, compute the regular pay and then go on to execute the output statement. But if hours is greater than 40, compute the regular pay and the overtime pay, and then go on to execute the output statement.” FIGURE 5.4 shows the flow of control of this If statement.

FIGURE 5.4 Flow of Control for Calculating Pay

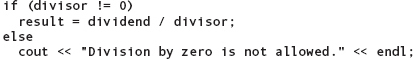

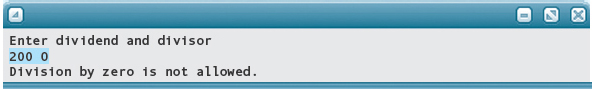

If-Then-Else often is used to check the validity of input. For example, before we ask the computer to divide by a data value, we should make sure that the value is not zero. (Even computers can’t divide something by zero. If you try, most computers halt the execution of your program.) If the divisor is zero, our program should print out an error message. Here’s the code:

As another example of an If-Then-Else, suppose we want to determine where in a string variable the first occurrence (if any) of the letter A is located and the first occurrence (if any) of the letter B. Recall from Chapter 3 that the string class has a member function named find, which returns the position where the item was found (or the named constant string::npos if the item wasn’t found). The following program outputs the result of such a search, including one that succeeds and one that doesn’t.

Here is the result of running the program:

Before we look any further at If statements, take another look at the syntax template for the If-Then-Else. According to the template, there is no semicolon at the end of an If statement. In all of the program fragments we have seen so far—the worker’s pay, division-by-zero, and string search examples—there seems to be a semicolon at the end of each If statement. Actually, these semicolons belong to the statements in the else-clauses in those examples; assignment statements end in semicolons, as do output statements. The If statement doesn’t have its own semicolon at the end.

Blocks (Compound Statements)

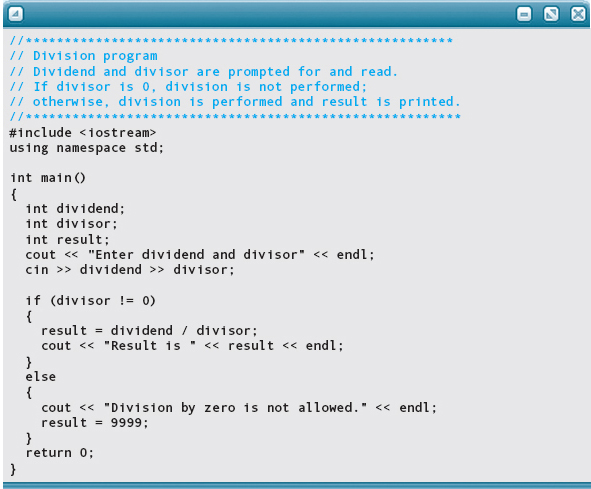

In our division-by-zero example, suppose that when the divisor is equal to zero we want to do two things: print the error message and set the variable named result equal to a special value like 9999. We would need two statements in the same branch, but the syntax template seems to limit us to one.

What we really want to do is turn the else-clause into a sequence of statements. This is easy. Recall from Chapter 2 that the compiler treats the block (compound statement)

like a single statement. If you put a { } pair around the sequence of statements you want in a branch of the If statement, the sequence of statements becomes a single block. For example:

If the value of divisor is 0, the computer both prints the error message and sets the value of result to 9999 before continuing with whatever statement follows the If statement.

Blocks can be used in both branches of an If-Then-Else, as shown in the following program.

Here is an example that succeeds:

Here is one in which the division fails:

When you use blocks in an If statement, you must remember this rule of C++ syntax: Never use a semicolon after the right brace of a block. Semicolons are used only to terminate simple statements such as assignment statements, input statements, and output statements. If you look at the previous examples, you won’t see a semicolon after the right brace that signals the end of each block.

MATTERS OF STYLE Braces and Blocks

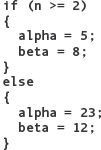

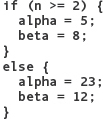

C++ programmers use different styles when it comes to locating the left brace of a block. The style we use in this book puts the left and right braces directly below the words if and else, with each brace appearing on its own line:

Another popular style is to place the left braces at the end of the if line and the else line; the right braces still line up directly below the words if and else. This way of formatting the If statement originated with programmers using the C language, the predecessor of C++.

It makes no difference to the C++ compiler which style you use (and there are other styles as well). It’s a matter of personal preference. Whichever style you use, though, you should always use the same style throughout a program. Inconsistency can confuse the person reading your program and give the impression of carelessness.

Sometimes you run into a situation where you want to say, “If a certain condition exists, then perform some action; otherwise, don’t do anything.” In other words, you want the computer to skip a sequence of instructions if a certain condition isn’t met. You could do this by leaving the else branch empty, using only the null statement:

Better yet, you can simply leave off the else part. The resulting statement is the If-Then form of the If statement. This is its syntax template:

If Statement (the If-Then form)

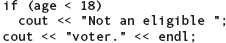

Here’s an example of an If-Then. Notice the indentation and the placement of the statement that follows the If-Then.

This statement means that if age is less than 18, first print “Not an eligible” and then print “voter.” If age is not less than 18, skip the first output statement and go directly to print “voter.” FIGURE 5.5 shows the flow of control for an If-Then statement.

Like the two branches in an If-Then-Else, the one branch in an If-Then can be a block. For example, suppose you are writing a program to compute income taxes. One of the lines on the tax form reads “Subtract line 23 from line 17 and enter result on line 24; if result is less than zero, enter zero and check box 24A.” You can use an If-Then to do this in C++:

FIGURE 5.5 If-Then Flow of Control

This code does exactly what the tax form says it should: It computes the result of subtracting line 23 from line 17. Then it looks to see if result is less than 0. If it is, the fragment prints a message telling the user to check box 24A and then sets result to 0. Finally, the calculated result (or 0, if the result is less than 0) is stored into a variable named line24.

What happens if we leave out the left and right braces in the code fragment? Let’s look at it:

Despite the way we have indented the code, the compiler takes the then-clause to be a single statement—the output statement. If result is less than 0, the computer executes the output statement, then sets result to 0, and then stores result into line24. So far, so good. But if result is initially greater than or equal to 0? Then the computer skips the then-clause and proceeds to the statement following the If statement—the assignment statement that sets result to 0. The unhappy outcome is that result ends up as 0 no matter what its initial value was!

The moral here is not to rely on indentation alone; you can’t fool the compiler. If you want a compound statement for a then- or else-clause, you must include the left and right braces.

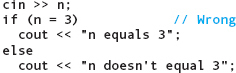

A Common Mistake

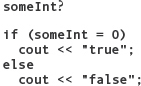

Earlier we warned against confusing the = operator with the == operator. Here is an example of a mistake that every C++ programmer is guaranteed to make at least once in his or her career:

This code segment always prints out

n equals 3

no matter what was input for n.

Here is the reason: We’ve used the wrong operator in the If test. The expression n = 3 is not a logical expression; it’s an assignment expression. (If an assignment is written as a separate statement ending with a semicolon, it’s an assignment statement.) An assignment expression has a value (here, it’s 3) and a side effect (storing 3 into n). In the If statement of our example, the computer finds the value of the tested expression to be 3. Because 3 is a nonzero value and thus is coerced to true, the then-clause is executed, no matter what the value of n is. Worse yet, the side effect of the assignment expression is to store 3 into n, destroying what was there.

Our intention is not to focus on assignment expressions; we discuss their use later in the book. What’s important now is that you see the effect of using = when you meant to use ==. The program compiles correctly but runs incorrectly. When debugging a faulty program, always look at your If statements to see whether you’ve made this particular mistake.

SOFTWARE MAINTENANCE CASE STUDY: Incorrect Output

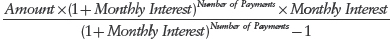

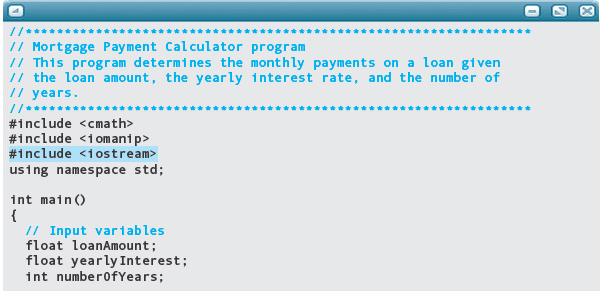

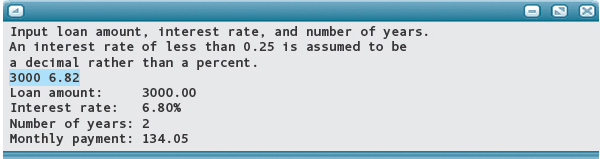

MAINTENANCE TASK: When you were helping your parents with their mortgage loan, you wrote a program to determine the monthly payments given the amount to be borrowed, the interest rate, and the number of years. You gave the same program to a friend to use when she was buying a car. She says that the program gives very strange results. You ask for an example of the erroneous output. She said it gave a ridiculously high rate for an amount of $3000, for 2 years at an interest rate of 6.8%.

VERIFYING THE BEHAVIOR: Whenever a user reports a bug, you should begin by making sure that you can generate the reported behavior yourself. This sets up the necessary conditions for isolating the problem and testing your modifications. You run the program using the data your friend supplied and the answers seem reasonable.

Loan amount: |

3000.00 |

Interest rate: |

0.0680 |

Number of years: |

2 |

Monthly payment: |

134.05 |

Because you can’t get the program to exhibit the bug, you go back to your friend to ask more questions. (Remember, that’s one of our problem-solving strategies, and they apply just as much to debugging as to writing new applications.) “What sort of ridiculously high rate did you get?” you ask her. Your friend says that she got 1700.0355647311262 as the payment amount. Clearly, $1700.03 per month for 2 years is not correct. What could have gone wrong?

Just as a mechanic may have to go for a drive with a car’s owner to understand what’s wrong, sometimes you have to sit and watch a user run your application. You ask your friend to show you what happened. Here’s what she did:

Loan amount: |

3000.00 |

Interest rate: |

6.8000 |

Number of years: |

2 |

Monthly payment: |

1700.04 |

Aha! You wrote the code to read the interest rate as a decimal fraction, and she is entering it as a percentage! There’s an easy solution to this problem. You can tell her to enter the interest rate as a decimal fraction, and you won’t have to change the code at all. Such a “fix” is known as a workaround.

She can do this, but says, “It’s annoying to have to do the math in my head. Why can’t you fix the program so that it takes the percentage the way that people normally write it?” She has a good point. As a programmer, you wrote the code in a way that made it easier for you. But a good application should be designed to make it easier for the user, which is what we mean by user friendly. If other people will be using your application, you must think in those terms.

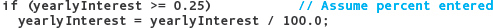

To make your friend happy, you have to change the program to first divide the input percentage by 100. But then you remember that you’ve also given the program to a friend who is a math major and who prefers to enter percentages as decimal fractions. The program could ask the user for his or her preference, but again, that’s more work for the user. What to do? How to accommodate both kinds of users with the least hassle?

Obviously, there has to be a branch somewhere in the application that chooses between dividing the percentage by 100 and using it as entered. Interest rates on loans are generally no more than about 25% and no less than one-quarter of a percent. So we could simply say that any number greater than or equal to 0.25 is assumed to be a percentage, and any number less than that is a decimal fraction. Thus, the necessary If statement would be written as follows:

Is that the only change? That’s all that’s required to make the program do the proper calculations. However, your friend indicated that it would be nice to have a version that used the keyboard for input and output rather than files. Let’s make this version use keyboard input and output and include our assumptions in the input prompts.

MODIFIED CODE: You call up the file with your source code so that you can modify it. You also re-familiarize yourself with the compound interest formula:

You then insert the revised input and output and the If statement. The changes are highlighted in the code below.

Here is the output from two test runs of the application, one with data entered as a percentage and one with data entered as a decimal:

QUICK CHECK

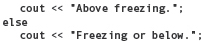

5.3.1 Write an If-Then-Else statement that uses the test from Question 5.2.2 to output either "Above freezing." or "Freezing or below.". (pp. 193–195)

5.3.2 Why must we provide code for both actions of an If statement? (p. 192)

5.3.3 What data type must the expression in parentheses of an If statement evaluate to? (p. 193)

5.4 Nested If Statements

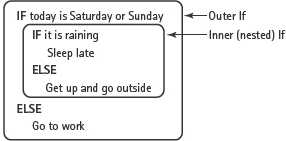

There are no restrictions on what the statements in an If can be. Therefore, an If within an If is okay. In fact, an If within an If within an If is legal. The only limitation here is that people cannot follow a structure that is too involved, and readability is one of the hallmarks of a good program.

When we place an If within an If, we are creating a nested control structure. Control structures nest much like mixing bowls do, with smaller ones tucked inside larger ones. Here’s an example, written in pseudocode:

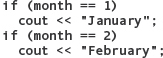

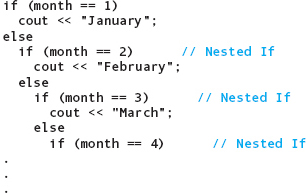

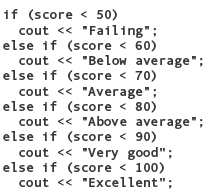

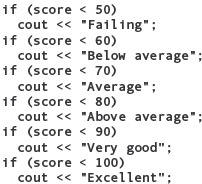

In general, any problem that involves a multiway branch (more than two alternative courses of action) can be coded using nested If statements. For example, to print out the name of a month given its number, we could use a sequence of If statements (unnested):

But the equivalent nested If structure,

is more efficient because it makes fewer comparisons. The first version—the sequence of independent If statements—always tests every condition (all 12 of them), even if the first one is satisfied. In contrast, the nested If solution skips all remaining comparisons after one alternative has been selected. As fast as modern computers are, many applications require so much computation that inefficient algorithms can waste hours of computer time. Always be on the lookout for ways to make your programs more efficient, as long as doing so doesn’t make them difficult for other programmers to understand. It’s usually better to sacrifice a little efficiency for the sake of readability.

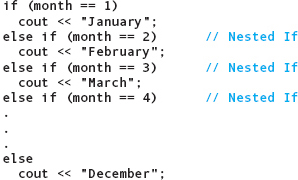

In the last example, notice how the indentation of the then- and else-clauses causes the statements to move continually to the right. Alternatively, we can use a special indentation style with deeply nested If-Then-Else statements to indicate that the complex structure is just choosing one of a set of alternatives. This general multiway branch is known as an If-Then-Else-If control structure:

This style prevents the indentation from marching continuously to the right. More importantly, it visually conveys the idea that we are using a 12-way branch based on the variable month.

It’s important to note one difference between the sequence of If statements and the nested If: More than one alternative can be taken by the sequence of Ifs, but the nested If can select only one option. To see why this is important, consider the analogy of filling out a questionnaire. Some questions are like a sequence of If statements, asking you to circle all the items in a list that apply to you (such as all your hobbies). Other questions ask you to circle only one item in a list (your age group, for example) and are thus like a nested If structure. Both kinds of questions occur in programming problems. Being able to recognize which type of question is being asked permits you to immediately select the appropriate control structure.

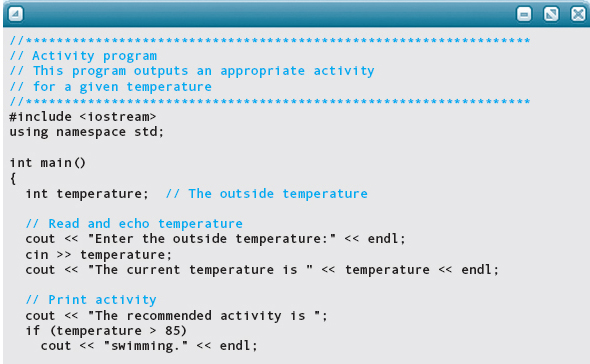

Another particularly helpful use of the nested If is when you want to select from a series of consecutive ranges of values. For example, suppose that we want to print out an appropriate activity for the outdoor temperature, given the following information:

Activity |

Temperature |

Swimming |

temperature > 85 |

Tennis |

70 < temperature <= 85 |

Golf |

32 < temperature <= 70 |

Skiing |

0 < temperature <= 32 |

Dancing |

temperature <= 0 |

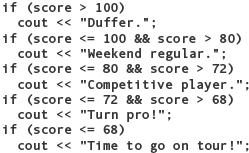

At first glance, you may be tempted to write a separate If statement for each range of temperatures. On closer examination, however, it is clear that these If conditions are interdependent. That is, if one of the statements is executed, none of the others should be executed. We are really selecting one alternative from a set of possibilities—just the sort of situation in which we can use a nested If structure as a multiway branch. The only difference between this problem and our earlier example of printing the month name from its number is that we must check ranges of numbers in the If expressions of the branches.

When the ranges are consecutive, we can take advantage of that fact to make our code more efficient. We arrange the branches in consecutive order by range. Then, if a particular branch has been reached, we know that the preceding ranges have been eliminated from consideration. Thus the If expressions must compare the temperature to only the lowest value of each range. To see how this works, look at the following Activity program.

To understand how the If-Then-Else-If structure in this program works, consider the branch that tests for temperature greater than 70. If it has been reached, we know that temperature must be less than or equal to 85 because that condition causes this particular else branch to be taken. Thus we need to test only whether temperature is above the bottom of this range (> 70). If that test fails, then we enter the next else-clause knowing that temperature must be less than or equal to 70. Each successive branch checks the bottom of its range until we reach the final else, which takes care of all the remaining possibilities.

If the ranges aren’t consecutive, however, we must test the data value against both the highest and lowest values of each range. We still use an If-Then-Else-If because that is the best structure for selecting a single branch from multiple possibilities, and we may arrange the ranges in consecutive order to make them easier for a human reader to follow. In such a case, there is no way to reduce the number of comparisons when there are gaps between the ranges.

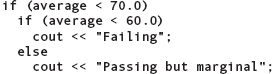

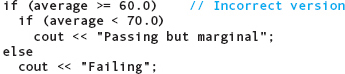

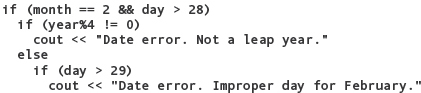

The Dangling else

When If statements are nested, you may find yourself confused about the if-else pairings. That is, to which if does an else belong? For example, suppose that if a student’s average is below 60, we want to print “Failing”; if the average is at least 60 but less than 70, we want to print “Passing but marginal”; and if it is 70 or greater, we don’t want to print anything. We code this information with an If-Then-Else nested within an If-Then:

How do we know to which if the else belongs? Here is the rule that the C++ compiler follows: In the absence of braces, an else is always paired with the closest preceding if that doesn’t already have an else paired with it. We indented the code to reflect this pairing.

Suppose we write the fragment like this:

Here we want the else branch attached to the outer If statement, not the inner If, so we indent the code as you see it. Of course, indentation does not affect the execution of the code. Even though the else aligns with the first if, the compiler pairs it with the second if. An else that follows a nested If-Then is called a dangling else. It doesn’t logically belong with the nested If but is attached to it by the compiler.

To attach the else to the first if, not the second, you can turn the outer then-clause into a block:

The { } pair indicates that the inner If statement is complete, so the else must belong to the outer if.

QUICK CHECK

5.4.1 What purpose does a nested branch serve? (pp. 203–205)

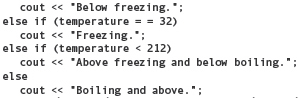

5.4.2 Write nested If statements to print messages indicating whether a temperature is below freezing, freezing, above freezing but not boiling, or boiling and above. (pp. 203–205)

5.4.3 What type of control structure do we have when an If statement is within another If statement? (p. 203)

5.4.4 What type of branching control structure is used when we have many (more than 2) alternative courses of action? (p. 204)

5.4.5 What problem does a C++ compiler solve using the rule: In the absence of braces, an else is always paired with the closest preceding if that doesn’t already have an else paired with it. (p. 206)

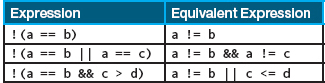

5.5 Logical Operators

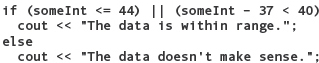

In mathematics, the logical (or Boolean) operators AND, OR, and NOT take logical expressions as operands. C++ uses special symbols for the logical operators: && (for AND), || (for OR), and ! (for NOT). By combining relational operators with logical operators, we can make more complex assertions. For example, in the last section we used two If statements to determine if an average was greater than 60.0 but less than 70.0. In C++, we would write the expression this way:

average >= 60.0 && average < 70.0

The AND operation (&&) requires both relationships to be true for the overall result to be true. If either or both of the relationships are false, the entire result is false.

The OR operation (||) takes two logical expressions and combines them. If either or both are true, the result is true. Both values must be false for the result to be false. For example, we can determine whether the midterm grade is an A or the final grade is an A. If either the midterm grade or the final grade equals A, the assertion is true. In C++, we write the expression like this:

midtermGrade == 'A' || finalGrade == 'A'

The && and || operators always appear between two expressions; they are binary (two-operand) operators. The NOT operator (!) is a unary (one-operand) operator. It precedes a single logical expression and gives its opposite as the result. If (grade == 'A') is false, then !(grade == 'A') is true. NOT gives us a convenient way of reversing the meaning of an assertion. For example,

!(hours > 40)

hours <= 40

In some contexts, the first form is clearer; in others, the second makes more sense.

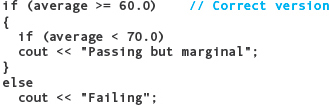

The following pairs of expressions are equivalent:

Take a close look at these expressions to be sure you understand why they are equivalent. Try evaluating them with some values for a, b, c, and d. Notice the pattern: The expression on the left is just the one to its right with ! added and the relational and logical operators reversed (for example, == instead of != and || instead of &&). Remember this pattern. It allows you to rewrite expressions in the simplest form.3

Logical operators can be applied to the results of comparisons. They can also be applied directly to variables of type bool. For example, instead of writing

isElector = (age >= 18 && district == 23);

to assign a value to the Boolean variable isElector, we could use two intermediate Boolean variables, isVoter and isConstituent:

isVoter = (age >= 18);

isConstituent = (district == 23);

isElector = isVoter && isConstituent;

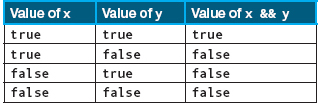

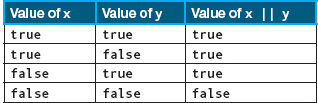

The following two tables summarize the results of applying && and || to a pair of logical expressions (represented here by Boolean variables x and y).

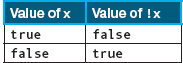

The following table summarizes the results of applying the ! operator to a logical expression (represented by Boolean variable x):

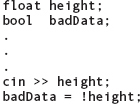

Technically, the C++ operators !, &&, and || are not required to have logical expressions as operands. Their operands can be of any simple data type, even floating-point types. If an operand is not of type bool, its value is temporarily coerced to type bool as follows: A 0 value is coerced to false, and any nonzero value is coerced to true. As an example, you sometimes encounter C++ code that looks like this:

The assignment statement says to set badData to true if the coerced value of height is false. That is, the statement is really saying, “Set badData to true if height equals 0.0.” Although this assignment statement works correctly in the C++ language, the following statement is more readable:

badData = (height == 0.0);

Throughout this text we apply the logical operators only to logical expressions, not to arithmetic expressions.

Caution: It’s easy to confuse the logical operators && and || with two other C++ operators, & and |. We don’t discuss the & and | operators here, but we’ll tell you that they are used for manipulating individual bits within a memory cell—a role quite different from that of the logical operators. If you accidentally use & instead of &&, or | instead of ||, you won’t get an error message from the compiler, but your program probably will compute wrong answers. Some programmers pronounce && as “and-and” and || as “or-or” to avoid making mistakes.

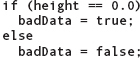

The preceding assignment statement can also be implemented using an If statement. That is,

badData = (height == 0.0);

can be implemented as

As you can see, the first form is simpler to write and, with a little practice, is easier to read.

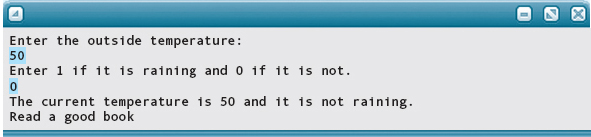

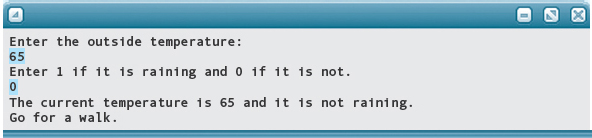

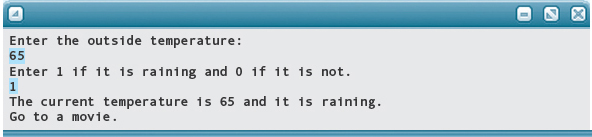

The following application sets the Boolean variables walk, movie, and book to true or false depending on what the temperature is and whether it is raining. An If statement is then used to print the results.

Following are the results of running the program on four different sets of input:

Short-Circuit Evaluation

Consider the logical expression

i == 1 && j > 2

Some programming languages use full evaluation of logical expressions. With full evaluation, the computer first evaluates both subexpressions (both i == 1 and j > 2) before applying the && operator to produce the final result.

In contrast, C++ uses short-circuit (or conditional) evaluation of logical expressions. Evaluation proceeds from left to right, and the computer stops evaluating subexpressions as soon as possible—that is, as soon as it knows the Boolean value of the entire expression. How can the computer know if a lengthy logical expression yields true or false if it doesn’t examine all the subexpressions? Let’s look first at the AND operation.

Short-circuit (conditional) evaluation Evaluation of a logical expression in left-to-right order, with evaluation stopping as soon as the final truth value can be determined.

An AND operation yields the value true only if both of its operands are true. In the earlier expression, suppose that the value of i happens to be 95. The first subexpression yields false, so it isn’t necessary even to look at the second subexpression. The computer stops evaluation and produces the final result of false.

With the OR operation, the left-to-right evaluation stops as soon as a subexpression yielding true is found. Remember that an OR produces a result of true if either one or both of its operands are true. Suppose we have this expression:

c <= d || e == f

If the first subexpression is true, evaluation stops and the entire result is true. The computer doesn’t waste time with an unnecessary evaluation of the second subexpression.

MAY WE INTRODUCE George Boole

Boolean algebra is named for its inventor, English mathematician George Boole, who was born in 1815. His father, a tradesman, began teaching George mathematics at an early age. But Boole initially was more interested in classical literature, languages, and religion—interests he maintained throughout his life. By the time he was 20, he had taught himself French, German, and Italian. He was well versed in the writings of Aristotle, Spinoza, Cicero, and Dante, and wrote several philosophical papers himself.

At 16, to help support his family, Boole took a position as a teaching assistant in a private school. His work there and a second teaching job left him little time to study. A few years later, he opened a school and began to learn higher mathematics on his own. In spite of his lack of formal training, his first scholarly paper was published in the Cambridge Mathematical Journal when he was just 24. Boole went on to publish more than 50 papers and several major works before he died in 1864, at the peak of his career.

Boole’s The Mathematical Analysis of Logic was published in 1847. It would eventually form the basis for the development of digital computers. In the book, Boole set forth the formal axioms of logic (much like the axioms of geometry) on which the field of symbolic logic is built.

Boole drew on the symbols and operations of algebra in creating his system of logic. He associated the value 1 with the universal set (the set representing everything in the universe) and the value 0 with the empty set, and restricted his system to these two quantities. He then defined operations that are analogous to subtraction, addition, and multiplication. Variables in the system have symbolic values. For example, if a Boolean variable P represents the set of all plants, then the expression 1 − P refers to the set of all things that are not plants. We can simplify the expression by using −P to mean “not plants.” (0 − P is simply 0 because we can’t remove elements from the empty set.) The subtraction operator in Boole’s system corresponds to the ! (NOT) operator in C++. In a C++ program, we might set the value of the Boolean variable plant to true when the name of a plant is entered, whereas !plant is true when the name of anything else is input.

The expression 0 + P is the same as P. However, 0 + P + F, where F is the set of all foods, is the set of all things that are either plants or foods. So the addition operator in Boole’s algebra is the same as the C++ || (OR) operator.

The analogy can be carried to multiplication: 0 × P is 0, and 1 × P is P. But what is P × F? It is the set of things that are both plants and foods. In Boole’s system, the multiplication operator is the same as the && (AND) operator.

In 1854, Boole published An Investigation of the Laws of Thought, on Which Are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities. In the book, he described theorems built on his axioms of logic and extended the algebra to show how probabilities could be computed in a logical system. Five years later, Boole published Treatise on Differential Equations, then Treatise on the Calculus of Finite Differences. The latter book is one of the cornerstones of numerical analysis, which deals with the accuracy of computations. (In Chapter 10, we examine the important role numerical analysis plays in computer programming.)

Boole received little recognition and few honors for his work. Given the importance of Boolean algebra in modern technology, it is hard to believe that his system of logic was not taken seriously until the early twentieth century. George Boole was truly one of the founders of computer science.

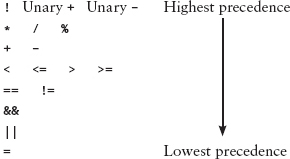

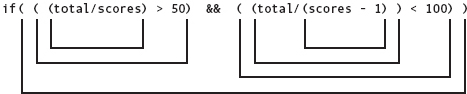

In Chapter 3, we discussed the rules of precedence—the rules that govern the evaluation of complex arithmetic expressions. C++’s rules of precedence also govern relational and logical operators. Here’s a list showing the order of precedence for the arithmetic, relational, and logical operators (with the assignment operator thrown in as well):

Operators on the same line in the list have the same precedence. If an expression contains several operators with the same precedence, most of the operators group (or associate) from left to right. For example, the expression

a / b * c

means (a / b) * c, not a / (b * c). However, the unary operators (!, unary +, unary -) group from right to left. Although you’d never have occasion to use this expression,

!!badData

its meaning is !(!badData) rather than the meaningless (!!)badData. Appendix B, “Precedence of Operators,” lists the order of precedence for all operators in C++. In skimming the appendix, you can see that a few of the operators associate from right to left (for the same reason we just described for the ! operator).

Parentheses are used to override the order of evaluation in an expression. If you’re not sure whether parentheses are necessary, use them anyway. The compiler disregards unnecessary parentheses. So, if they clarify an expression, use them. Some programmers like to include extra parentheses when assigning a relational expression to a Boolean variable:

dataInvalid = (inputVal == 0);

The parentheses are not actually needed here; the assignment operator has the lowest precedence of all the operators we’ve just listed. So we could write the statement as

dataInvalid = inputVal == 0;

Some people find the parenthesized version more readable, however.

One final comment about parentheses: C++, like other programming languages, requires that parentheses always be used in pairs. Whenever you write a complicated expression, take a minute to go through and pair up all of the opening parentheses with their closing counterparts.

Changing English Statements into Logical Expressions

In most cases, you can write a logical expression directly from an English statement or mathematical term in an algorithm. But you have to watch out for some tricky situations. Remember our sample logical expression:

midtermGrade == 'A' || finalGrade == 'A'

In English, you would be tempted to write this expression: “Midterm grade or final grade equals A.” In C++, you can’t write the expression as you would in English. That is,

midtermGrade || finalGrade == 'A'

won’t work because the || operator is connecting a char value (midtermGrade) and a logical expression (finalGrade == 'A'). The two operands of || should be logical expressions. (Note that this expression is wrong in terms of logic, but it isn’t “wrong” to the C++ compiler. Recall that the || operator may legally connect two expressions of any data type, so this example won’t generate a syntax error message. The program will run, but it won’t work the way you intended.) A variation of this mistake is to express the English assertion “i equals either 3 or 4” as follows:

i == 3 || 4

Again, the syntax is correct but the semantics are not. This expression always evaluates to true. The first subexpression, i == 3, may be true or false. But the second subexpression, 4, is nonzero and, therefore, is coerced to the value true. Thus the || operator causes the entire expression to be true. We repeat: Use the || operator (and the && operator) only to connect two logical expressions. Here’s what we want:

i == 3 || i == 4

In math books, you might see a notation like this:

12 < y < 24

which means “y is between 12 and 24.” This expression is legal in C++ but gives an unexpected result. First, the relation 12 < y is evaluated, giving the result true or false. The computer then coerces this result to 1 or 0 to compare it with the number 24. Because both 1 and 0 are less than 24, the result is always true. To write this expression correctly in C++, you must use the && operator as follows:

12 < y && y < 24

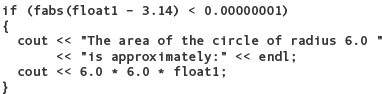

Relational Operators with Floating-Point Types

So far, we’ve talked about comparing int, char, and string values. Here we look at float values.

Do not compare floating-point numbers for equality. Because small errors in the rightmost decimal places are likely to arise when calculations are performed on floating-point numbers, two float values rarely are exactly equal. For example, consider the following code that uses two float variables named oneThird and x:

oneThird = 1.0 / 3.0;

x = oneThird + oneThird + oneThird;

We would expect x to contain the value 1.0, but it probably doesn’t. The first assignment statement stores an approximation of 1/3 into oneThird, perhaps 0.333333. The second statement stores a value like 0.999999 into x. If we now ask the computer to compare x with 1.0, the comparison yields false.

Instead of testing floating-point numbers for equality, we test for near equality. To do so, we compute the difference between the two numbers and test whether the result is less than some maximum allowable difference. For example, we often use comparisons like this:

fabs(r − s) < 0.00001

where fabs is the floating-point absolute value function from the C++ standard library. The expression fabs(r − s) computes the absolute value of the difference between two float variables r and s. If the difference is less than 0.00001, the two numbers are close enough to call them equal.

QUICK CHECK

5.5.1 What are the C++ boolean operators that correspond to the logical operators AND, OR, and NOT? (p. 207)

5.5.2 Write an equivalent boolean expression for (a != b && c < d) that uses the operators == and >= and !. (p. 208)

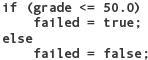

5.5.3 Write a single assignment statement that corresponds to the following If statement (assuming that grade is type float and failed is type bool): (p. 209)

5.5.4 Which direction is a logical expression evaluated in in C++? (p. 211)

5.5.5 Write a boolean expression such that it demonstrates short-circuit evaluation. Highlight the part of the | expression that is not executed. (p. 211)

5.6 Testing the State of an I/O Stream

In Chapter 4, we talked about the concept of input and output streams in C++. As part of that discussion, introduced the classes istream, ostream, ifstream, and ofstream. We said that any of the following can cause an input stream to enter the fail state:

Invalid input data

Invalid input data

An attempt to read beyond the end of a file

An attempt to read beyond the end of a file

An attempt to open a nonexistent file for input

An attempt to open a nonexistent file for input

C++ provides a way to check whether a stream is in the fail state. In a logical expression, you simply use the name of the stream object (such as cin) as if it were a Boolean variable:

if (cin)

.

.

.

.

.

.

When you do this, you are said to be testing the state of the stream. The result of the test is either true (meaning the last I/O operation on that stream succeeded) or false (meaning the last I/O operation failed). Conceptually, you want to think of a stream object in a logical expression as being a Boolean variable with a value true (the stream state is okay) or false (the state isn’t okay).

Testing the state of a stream The act of using a C++ stream object in a logical expression as if it were a Boolean variable; the result is true if the last I/O operation on that stream succeeded, and false otherwise.

In an If statement, the way you phrase the logical expression depends on what you want the then-clause to do. The statement

if (inFile)

.

.

.

executes the then-clause if the last I/O operation on inFile succeeded. The statement

if (!inFile)

.

.

.

executes the then-clause if inFile is in the fail state. (Remember that once a stream is in the fail state, it remains so. Any further I/O operations on that stream are null operations.)

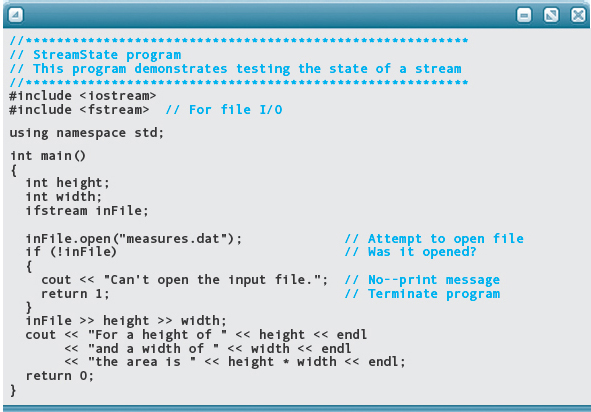

Here’s an example that shows how to check whether an input file was opened successfully:

In this program, we begin by attempting to open the file measures.dat for input. Immediately, we check whether the attempt succeeded. If it was successful, the value of the expression !inFile in the If statement is false and the then-clause is skipped. The program proceeds to read data from the file and then perform a computation. It concludes by executing the statement

return 0;

With this statement, the main function returns control to the operating system. Recall that the function value returned by main is known as the exit status. The value 0 signifies normal completion of the program. Any other value (typically 1, 2, 3, …) means that something went wrong.

Let’s trace through the program again, assuming we weren’t able to open the input file. Upon return from the open function, the stream inFile is in the fail state. In the If statement, the value of the expression !inFile is true. Thus the then-clause is executed. The program prints an error message to the user and then terminates, returning an exit status of 1 to inform the operating system of an abnormal termination of the program. (Our choice of the value 1 for the exit status is purely arbitrary. System programmers sometimes use several different values in a program to signal different reasons for program termination. But most people just use the value 1.)

Whenever you open a data file for input, be sure to test the stream state before proceeding. If you forget to do so, and the computer cannot open the file, your program quietly continues executing, and ignores any input operations on the file.

QUICK CHECK

5.6.1 Write an If statement that tests if the standard input stream is in the fail state. (pp. 215–217)

5.6.2 What terminology is used when you are trying to determine if a stream is in the fail state? (p. 216)

5.6.3 What happens if you do not test the state of a file input stream before using it? (p. 216)

Problem-Solving Case Study

BMI Calculator

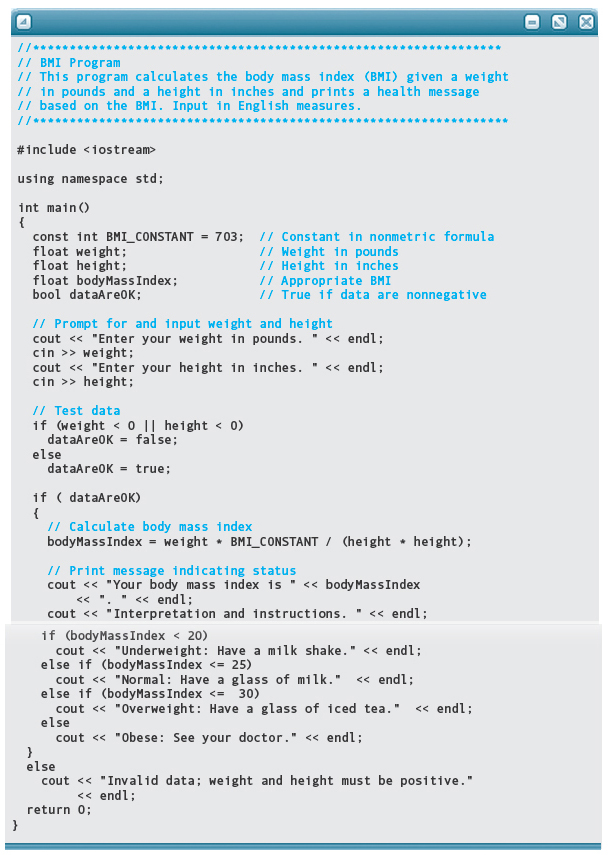

PROBLEM: A great deal has been said about how overweight much of the American population is today. You can’t pick up a magazine that doesn’t have an article on the health problems caused by obesity. Rather than looking at a chart that shows the average weight for a particular height, a measure called the body mass index (BMI), which computes a ratio of your weight and height, has become a popular tool to determine an appropriate weight. The formula for nonmetric values is

BMI = weight × 703 / height2

BMI correlates with the amount of body fat, which can be used to determine whether a weight is unhealthy for a certain height.

Although the discussion of the BMI in the media is a fairly recent phenomenon, the formula was actually developed by Adolphe Quetelet, a nineteenth-century Belgian statistician. Do a search of the Internet for “body mass index” and you will find more than a million hits. In these references, the formula remains the same but the interpretation of the result varies, depending upon age and gender. Here is the most commonly used generic interpretation:

BMI |

Interpretation |

< 20 |

Underweight |

20–25 |

Normal |

26–30 |

Overweight |

> 30 |

Obese |

Write a program that calculates the BMI given a weight and height and prints out an appropriate message.

INPUT: The problem statement says that the formula is for nonmetric values. In other words, the weight should be in pounds and the height should be in inches. Thus the input should be two float values: weight and height.

OUTPUT

Prompts for the input values

Prompts for the input values

A message based on the BMI

A message based on the BMI

DISCUSSION: To calculate the BMI, you read in the weight and height and plug them into the formula. If you square the height, you must include <cmath> to access the pow function. It is more efficient to just multiply height by itself.

BMI = weight × 703 / (height × height)

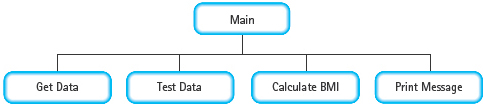

If you were calculating this index by hand, you would probably notice if the weight or height were negative and question it. If the semantics of your data imply that the values should be nonnegative, then your program should test to be sure that they are. The program should test each value and use a Boolean variable to report the results. Here is the main module for this algorithm.

Main

Level 0

Test data

IF data are okay

Calculate BMI

Print message indicating status

ELSE

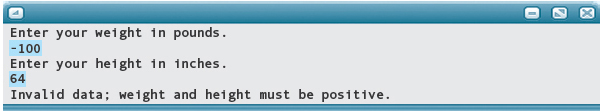

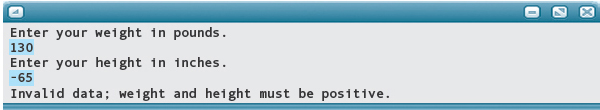

Print “Invalid data; weight and height must be positive.”

Which of these steps require expansion? Get data, Test data, and Print message indicating status all require multiple statements to solve their particular subproblem. By contrast, we can translate Print “Invalid data; …” directly into a C++ output statement. What about the step Calculate BMI? We can write it as a single C++ statement, but there’s another level of detail that we must fill in—the actual formula to be used. Because the formula is at a lower level of detail than the rest of the main module, we choose to expand Calculate BMI as a Level 1 module.

Test Data

IF weight < 0 OR height < 0

Set dataAreOk to false

ELSE

Set dataAreOk to true

Calculate BMI

Set bodyMassIndex to weight * 703 / (height * height)

Print Message Indicating Status

Print Message Indicating Status

The problem doesn’t say exactly what the message should be, other than reporting the status. Why not jazz up the output a little by printing an appropriate message along with the status.

Status |

Message |

Underweight |

Have a milk shake. |

Normal |

Have a glass of milk. |

Overweight |

Have a glass of iced tea. |

Obese |

See your doctor. |

Print “Your body mass index is”, bodyMassIndex, “.”

Print “Interpretation and instructions.”

IF bodyMassIndex <20

Print “Underweight: Have a milk shake.”

ELSE IF bodyMassIndex <= 25

Print “Normal: Have a glass of milk.”

ELSE IF bodyMassIndex <= 30

Print “Overweight: Have a glass of iced tea.”

ELSE

Print “Obese: See your doctor.”

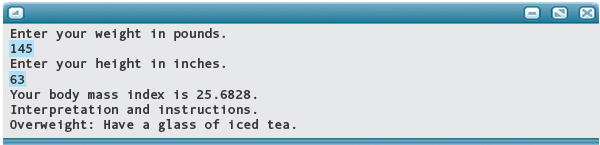

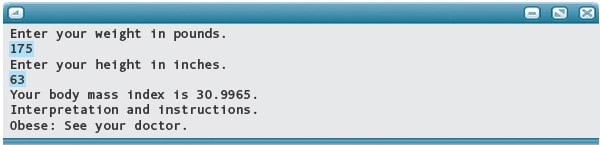

Here are outputs of runs with various heights and weights and with both good and bad data.

In this program, we use a nested If structure that is easy to understand although somewhat inefficient. We assign a value to dataAreOK in one statement before testing it in the next. We could reduce the code by writing

dataAreOK = !(weight < 0 || height < 0);

Using DeMorgan’s law, we also could write this statement as

dataAreOK = (weight >= 0 && height >= 0);

In fact, we could reduce the code even more by eliminating the variable dataAreOK and using

if (weight => 0 && height >= 0)

.

.

.

in place of

if (dataAreOK)

.

.

.

To convince yourself that these three variations work, try them by hand with some test data. If all of these statements do the same thing, how do you choose which one to use? If your goal is efficiency, the final variation—the compound condition in the main If statement—is the best choice. If you are trying to express as clearly as possible what your code is doing, the longer form shown in the program may be the best option. The other variations lie somewhere in between. (Some people would find the compound condition in the main If statement to be not only the most efficient, but also the clearest to understand.) There are no absolute rules to follow here, but the general guideline is to strive for clarity, even if you must sacrifice a little efficiency.

Testing and Debugging

In Chapter 1, we discussed the problem-solving and implementation phases of computer programming. Testing is an integral part of both phases. Here, we test both phases of the process used to develop the BMI program. Testing in the problem-solving phase is done after the solution is developed but before it is implemented. In the implementation phase, we do testing after the algorithm is translated into a program, and again after the program has compiled successfully. The compilation itself constitutes another stage of testing that is performed automatically.

Testing in the Problem-Solving Phase: The Algorithm Walk-Through

Determining Preconditions and Postconditions

To test during the problem-solving phase, we do a walk-through of the algorithm. For each module in the functional decomposition, we establish an assertion called a precondition and another called a postcondition. A precondition is an assertion that must be true before a module is executed for the module to execute correctly. A postcondition is an assertion that should be true after the module has executed, if it has done its job correctly. To test a module, we “walk through” the algorithmic steps to confirm that they produce the required postcondition, given the stated precondition.

Precondition An assertion that must be true before a module begins executing.

Postcondition An assertion that should be true after a module has executed.

Our algorithm has five modules: the main module, Get Data, Test Data, Calculate BMI, and Print Message Indicating Status. Usually there is no precondition for a main module. Our main module’s postcondition is that it outputs the correct results, given the correct input. More specifically, the postcondition for the main module is as follows:

The computer has input two real values into weight and height.

The computer has input two real values into weight and height.

If the input is invalid, an error message has been printed; otherwise, the body mass index has been calculated and an appropriate message has been printed based on the result.

If the input is invalid, an error message has been printed; otherwise, the body mass index has been calculated and an appropriate message has been printed based on the result.

Because Get Data is the first module executed in the algorithm and because it does not assume anything about the contents of the variables it is about to manipulate, it has no precondition. Its postcondition is that it has input two real values into weight and height.

The precondition for module Test Data is that weight and height have been assigned meaningful values. Its postcondition is that dataAreOK contains true if the values in weight and height are nonnegative; otherwise, dataAreOK contains false.

The precondition for module Calculate BMI is that weight and height contain meaningful values. Its postcondition is that the variable named dataAreOK contains the evaluation of the BMI formula (weight * 703 / (height * height)).

The precondition for module Print Message Indicating Status is that dataAreOK contains the result of evaluating the BMI formula. Its postcondition is that appropriate documentation and the value in dataAreOK have been printed, along with the messages: “Underweight: Have a milk shake.” if the BMI value is less than 20; “Normal: Have a glass of milk.” if the value is less than or equal to 26; “Overweight: Have a glass of iced tea.” if the value is less than or equal to 30; and “Obese: See your doctor.” if the value is greater than 30.

The module preconditions and postconditions are summarized in the following table. In the table, we use AND with its usual meaning in an assertion—the logical AND operation. Also, a phrase like “someVariable is assigned” is an abbreviated way of asserting that someVariable has already been assigned a meaningful value.

Module |

Precondition |

Postcondition |

Main |

Two float values have been input AND if the input is valid, the BMI formula is calculated and the value is printed with an appropriate message; otherwise, an error message has been printed. |

|

Get Data |

weight and height have been input. |

|

Test Data |

weight and height are assigned values. |

dataAreOK contains true if weight and height are nonnegative; otherwise, dataAreOK contains false. |

Calculate BMI |

weight and height are assigned values. |

bodyMassIndex contains the evaluation of the BMI formula. |

Print Message |

bodyMassIndex contains the evaluation of the BMI formula. |

The value of bodyMassIndex has been printed, along with a message interpreting the value. |

Performing the Algorithm Walk-Through

Now that we’ve established the preconditions and postconditions, we walk through the main module. At this point, we are concerned only with the steps in the main module, so for now we assume that each lower-level module executes correctly. At each step, we must determine the current conditions. If the step is a reference to another module, we must verify that the precondition of that module is met by the current conditions.

We begin with the first statement in the main module. Get Data does not have a precondition, and we assume that Get Data satisfies its postcondition that it correctly inputs two real values into weight and height.

The precondition for module Test Data is that weight and height are assigned values. This must be the case if Get Data’s postcondition is true. Again, because we are concerned only with the step at Level 0, we assume that Test Data satisfies its postcondition that dataAreOK contains true or false, depending on the input values.

Next, the If statement checks to see if dataAreOK is true. If it is, the algorithm performs the then-clause. Assuming that Calculate BMI correctly evaluates the BMI formula and that Print Message Indicating Status prints the result and the appropriate message (remember, we’re assuming that the lower-level modules are correct for now), then the If statement’s then-clause is correct. If the value in dataAreOK is false, the algorithm performs the else-clause and prints an error message.

We now have verified that the main (Level 0) module is correct, assuming the Level 1 modules are correct. The next step is to examine each module at Level 1 and answer this question: If the Level 2 modules (if any) are assumed to be correct, does this Level 1 module do what it is supposed to do? We simply repeat the walk-through process for each module, starting with its particular precondition. In this example, there are no Level 2 modules, so the Level 1 modules must be complete.

Get Data correctly reads in two values—weight and height—thereby satisfying its postcondition. (The next refinement is to code this instruction in C++. Whether it is coded correctly is not an issue in this phase; we deal with the code when we perform testing in the implementation phase.)

Test Data checks whether both variables contain nonnegative values. The If condition correctly uses OR operators to combine the relational expressions so that if either of them is true, the then-clause is executed. It thus assigns false to dataAreOK if either of the numbers is negative; otherwise, it assigns true. The module, therefore, satisfies its postcondition.

Calculate BMI evaluates the BMI formula: weight * 703 / (height * height). The required postcondition, therefore, is true. But what if the value of height is 0? Oh, dear! We checked that the inputs are nonnegative, but forgot that height is used as a divisor and thus cannot be 0. We’ll need to fix this problem before we release this program for general use.

Print Message Indicating Status outputs the value in bodyMassIndex with appropriate documentation. It then compares the result to the standards and prints the appropriate interpretation. “Underweight: Have a milk shake.” is printed if the value is less than 20; “Normal: Have a glass of milk.” is printed if the value is less than or equal to 26; “Overweight: Have a glass of iced tea.” is printed if the value is less than or equal to 30; and “Obese: See your doctor.” is printed if the value is greater than 30. Thus the module satisfies its postcondition.

Once we’ve completed the algorithm walk-through, we have to correct any discrepancies and repeat the process. When we know that the modules do what they are supposed to do, we start translating the algorithm into our programming language.

A standard postcondition for any program is that the user has been notified of invalid data. You should validate every input value for which any restrictions apply. A data-validation If statement tests an input value and outputs an error message if the value is not acceptable. (We validated the data when we tested for negative scores in the BMI program.) The best place to validate data is immediately after it is input. To satisfy the data-validation postcondition, the algorithm should also test the input values to ensure that they aren’t too large or too small.

Testing in the Implementation Phase

Now that we’ve talked about testing in the problem-solving phase, we turn to testing in the implementation phase. In this phase, you need to test at several points.

Code Walk-Through

After the code is written, you should go over it line by line to be sure that you’ve faithfully reproduced the algorithm—a process known as a code walk-through. In a team programming situation, you ask other team members to walk through the algorithm and code with you, to double-check the design and code.

Execution Trace

You also should take some actual values and hand-calculate what the output should be by doing an execution trace (or hand trace). When the program is executed, you can use these same values as input and check the results.

The computer is a very literal device—it does exactly what we tell it to do, which may or may not be what we want it to do. We try to make sure that a program does what we want by tracing the execution of the statements.

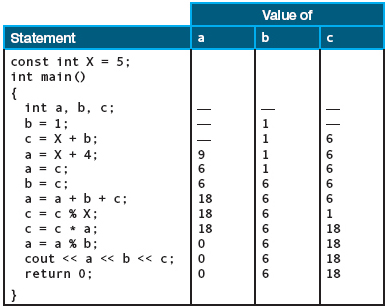

We use a nonsense program below to demonstrate the technique. We keep track of the values of the program variables on the right-hand side. Variables with undefined values are indicated with a dash. When a variable is assigned a value, that value is listed in the appropriate column.

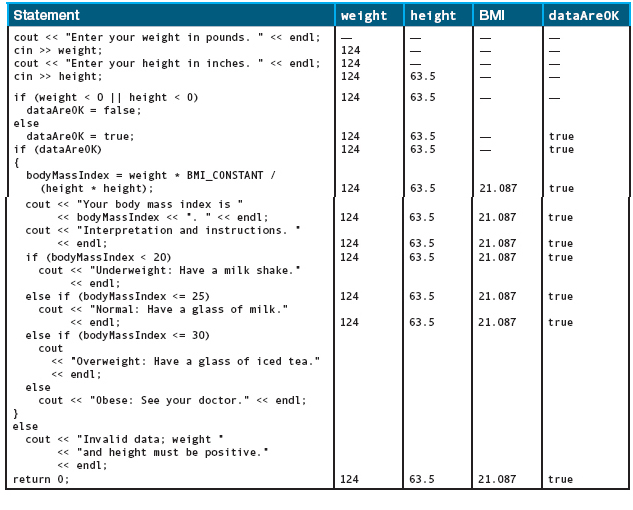

Now that you’ve seen how the technique works, let’s apply it to the BMI program. We list only the executable statement portion here. The input values are 124 and 63.5.

The then-clause of the first If statement is not executed for these input data, so we do not fill in any of the variable columns to its right. The then-clause of the second If statement is executed; thus the else-clause is not. The else-clause of the third If statement is executed, which is another If statement. The then-clause is executed here, leaving the rest of the code unexecuted.

We always create columns for all of the variables, even if we know that some will stay empty. Why? Because it’s possible that later we’ll encounter an erroneous reference to an empty variable; having a column for the variable reminds us to check for just such an error.

When a program contains branches, it’s a good idea to retrace its execution with different input data so that each branch is traced at least once. In the next section, we describe how to develop data sets that test all of a program’s branches.

Testing Selection Control Structures

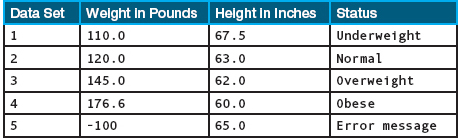

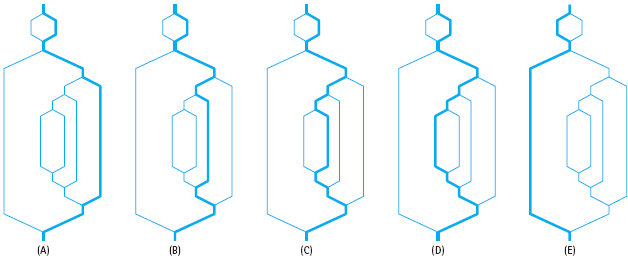

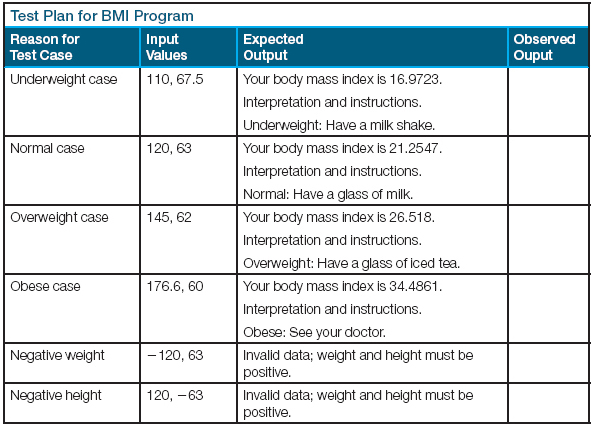

To test a program with branches, we need to execute each branch at least once and verify the results. For example, the BMI program contains five If-Then-Else statements (see FIGURE 5.6). We need a series of data sets to test the different branches. For example, the following sets of input values for weight and height cause all of the branches to be executed:

FIGURE 5.7 shows the flow of control through the branching structure of the BMI program for each of these data sets. Every branch in the program is executed at least once through this series of test runs; eliminating any of the test data sets would leave at least one branch untested. This series of data sets provides what is called minimum complete coverage of the program’s branching structure. Whenever you test a program with branches in it, you should design a series of tests that cover all of the branches. It may help to draw diagrams like those in Figure 5.7 so that you can see which branches are being executed.

Because an action in one branch of a program often affects processing in a later branch, it is critical to test as many combinations of branches, or paths, through a program as possible. By doing so, we can be sure that there are no interdependencies that could cause problems. Of course, some combinations of branches may be impossible to follow. For example, if the else-clause is executed in the first branch of the BMI program, the else-clause in the second branch cannot be executed. Shouldn’t we try all possible paths? Yes, in theory we should. However, even in a small program the number of paths can be very large.

FIGURE 5.6 Branching Structure for BMI Program

FIGURE 5.7 Flow of Control Through BMI Program for Each of Five Data Sets

The approach to testing that we’ve used here is called code coverage because the test data are designed by looking at the code of the program. Code coverage also is called white-box (or clear-box) testing because we are allowed to see the program code while designing the tests. Another approach to testing, called data coverage, attempts to test as many allowable data values as possible without regard to the program code. Because we need not see the code in this form of testing, it also is called black-box testing—we would design the same set of tests even if the code were hidden in a black box.

Complete data coverage is as impractical as complete code coverage for many programs. For example, if a program has four int input values, there are approximately (2 × INT_MAX)4 possible inputs. (INT_MAX and INT_MIN are constants declared in the header file <climits>. They represent the largest and smallest possible int values, respectively, on your particular computer and C++ compiler.)

Often, testing entails a combination of these two strategies. Instead of trying every possible data value (data coverage), we examine the code (code coverage) and look for ranges of values for which processing is identical. Then we test the values at the boundaries and, sometimes, a value in the middle of each range. For example, a simple condition such as

alpha < 0

divides the integers into two ranges:

1. INT_MIN through −1

2. 0 through INT_MAX

Thus we should test the four values INT_MIN, −1, 0, and INT_MAX. A compound condition such as

alpha >= 0 && alpha <= 100

divides the integers into three ranges:

1. INT_MIN through −1

2. 0 through 100

3. 101 through INT_MAX