Forming Good (and Bad) Decisions and Judgments

When making each day’s hundreds of judgments and decisions (Should I take a jacket? Can I trust this person? Should I shoot the basketball or pass to the player who’s hot?), we seldom take the time and effort to reason systematically. We follow our intuition, our fast, automatic, unreasoned feelings and thoughts. After interviewing policy makers in government, business, and education, social psychologist Irving Janis (1986) concluded that they “often do not use a reflective problem-solving approach. How do they usually arrive at their decisions? If you ask, they are likely to tell you . . . they do it mostly by the seat of their pants.”

Two Quick but Risky Shortcuts

When we need to make snap judgments, heuristics enable quick thinking without conscious awareness, and they usually serve us well (Gigerenzer, 2015). But as research by cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) on the representativeness and availability heuristics has shown, these intuitive mental shortcuts can lead even the smartest people into dumb decisions.

“In creating these problems, we didn’t set out to fool people. All our problems fooled us, too.”

“Intuitive thinking [is] fine most of the time. . . . But sometimes that habit of mind gets us in trouble.” Daniel Kahneman (2005)

The Representativeness Heuristic

To judge the likelihood of something by intuitively comparing it to particular prototypes is to use the representativeness heuristic. Imagine someone who is short, slim, and likes to read poetry. Is this person more likely to be an Ivy League university English professor or a truck driver (Nisbett & Ross, 1980)?

Many people guess English professor—because the person better fits their prototype of nerdy professor than of truck driver. In doing so, they fail to consider the base rate number of Ivy League English professors (fewer than 400) and truck drivers (3.5 million in the United States alone). Thus, even if the description is 50 times more typical of English professors than of truck drivers, the fact that there are about 7000 times more truck drivers means that the poetry reader is many times more likely to be a truck driver.

“The problem is I can’t tell the difference between a deeply wise, intuitive nudge from the Universe and one of my own bone-headed ideas!”

Some prototypes have social consequences. Consider the reaction of some non-Arab travelers soon after 9/11, when a young male of Arab descent boarded their plane. The young man fit (represented) their “terrorist” prototype, and the representativeness heuristic kicked in. His presence evoked anxiety among his fellow passengers—even though nearly 100 percent of those who fit this prototype are peace-loving citizens. One mother of two Black and three White teens asks other parents, “Do store personnel follow your children when they are picking out their Gatorade flavors? They didn’t follow my White kids. . . . When your kids trick-or-treat dressed as a ninja and a clown, do they get asked who they are with and where they live, door after door? My White kids didn’t get asked. Do your kids get pulled out of the TSA line time and again for additional screening? My White kids didn’t” (Roper, 2016). If people have a prototype—a stereotype—of delinquent Black teens, they may unconsciously use the representativeness heuristic when judging individuals. The result, even if unintended, is racism.

“ Kahneman and his colleagues and students have changed the way we think about the way people think.”

American Psychological Association President Sharon Brehm, 2007

The Availability Heuristic

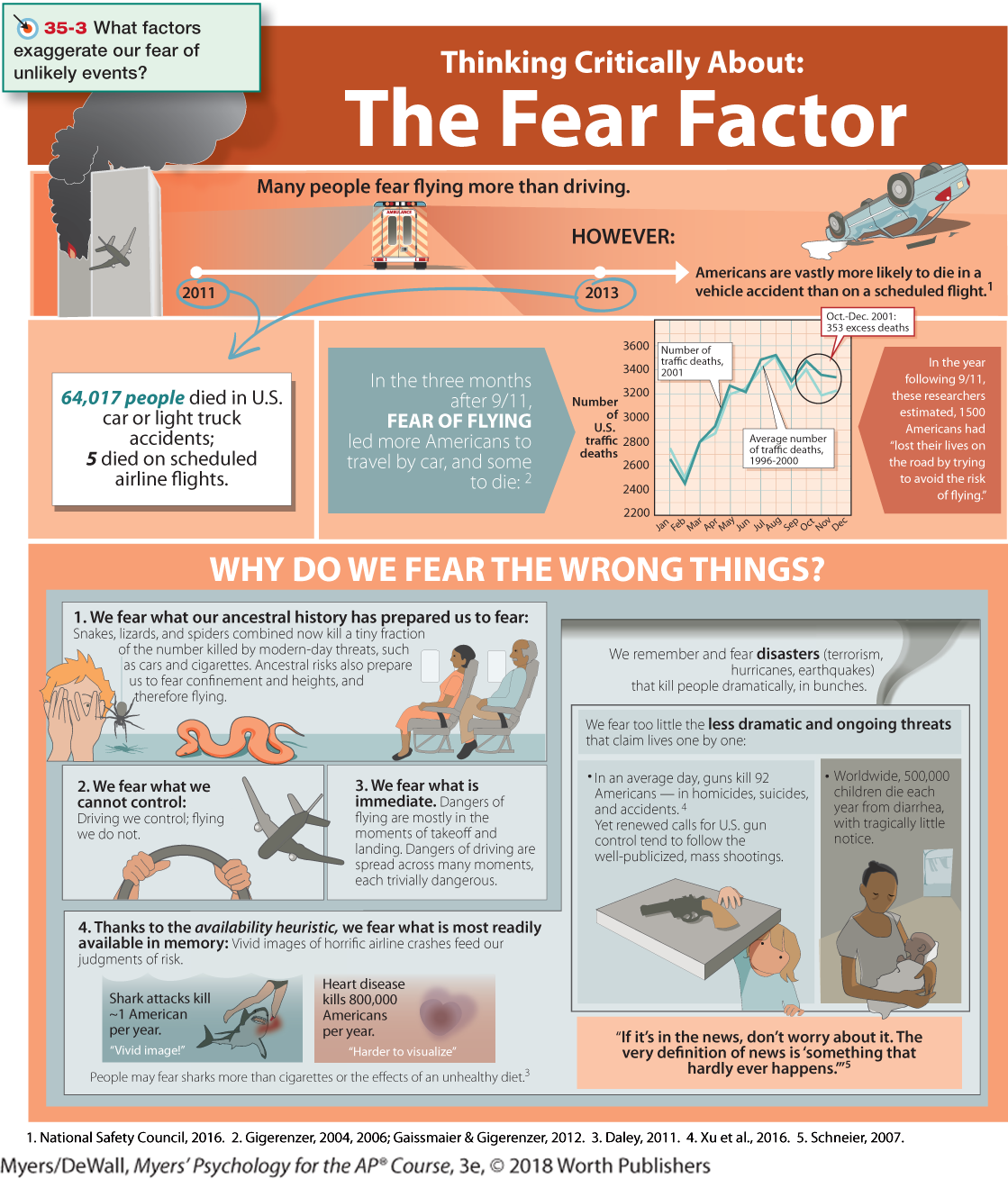

The availability heuristic operates when we estimate how common an event is based on its mental availability. Anything that makes information pop into mind—its vividness, recency, or distinctiveness—can make it seem commonplace. Casinos know this. They entice us to gamble by broadcasting wins with noisy bells and flashing lights. The big losses are soundlessly invisible.

The availability heuristic can also distort our judgments of other people. If people from a particular ethnic or religious group commit a terrorist act, as seen in pictures of innocent people about to be beheaded, our readily available memory of the dramatic event may shape our impression of the whole group. Terrorists aim to evoke excessive terror. If terrorists were to kill 1000 people in the United States this year, Americans would be mighty afraid. Yet they would have reason to be 30 times more afraid of homicidal, suicidal, and accidental death by guns, which take more than 30,000 lives annually. In 2015 and again in 2016, feared Islamic terrorists shot and killed fewer Americans than did armed toddlers (Ingraham, 2016; LaCapria, 2015). The bottom line: We often fear the wrong things. (See Thinking Critically About: The Fear Factor).

Meanwhile, the lack of available images of future climate change disasters—which some scientists regard as “Armageddon in slow motion”—has left many people unconcerned (Pew, 2014). What’s more cognitively available than slow climate change is our recently experienced local weather, which tells us nothing about long-term planetary trends (Egan & Mullin, 2012; Kaufmann et al., 2017; Zaval et al., 2014). Unusually hot local weather increases people’s worry about global climate warming, while a recent cold day reduces their concern and overwhelms less memorable scientific data (Li et al., 2011). After Hurricane Sandy devastated New Jersey, its residents’ vivid experience of extreme weather increased their environmentalism (Rudman et al., 2013).

The power of a vivid example The unforgettable (cognitively available) photo of 5-year-old Omran Daqneesh—dazed after being pulled from the rubble of yet another air strike in Aleppo, Syria—did more than an armload of statistics to awaken Western nations to the plight of Syrian migrants fleeing violence.

Over 40 nations have sought to harness the positive power of vivid, memorable images by putting eye-catching warnings and graphic photos on cigarette packages (Riordan, 2013). This campaign has worked because we reason emotionally (Huang et al., 2013). We overfeel and underthink (Slovic, 2007). In one study, Red Cross donations to Syrian refugees were 55 times greater in response to the publication of an iconic photo of a child killed compared with statistics describing the hundreds of thousands of other refugee deaths (Slovic et al., 2017). Dramatic outcomes make us gasp; probabilities we hardly grasp.

“ Don’t believe everything you think.”

Bumper sticker

Overconfidence

Sometimes our decisions and judgments go awry simply because we are more confident than correct. Across various tasks, people overestimate their performance (Metcalfe, 1998). If 60 percent of people correctly answer a factual question, such as “Is absinthe a liqueur or a precious stone?” they will typically average 75 percent confidence (Fischhoff et al., 1977). (It’s a licorice-flavored liqueur.) This tendency to overestimate the accuracy of our knowledge and judgments is overconfidence. Those who are wrong are especially vulnerable to overconfidence. One experiment gave students various physics and logic problems. Students who falsely thought a ball would continue following a curved path when rolling out of a curved tube were virtually as confident as those who correctly discerned that the ball, like water from a curled hose, would follow a straight path (Williams et al., 2013).

It is overconfidence that drives stockbrokers and investment managers to market their ability to outperform stock market averages—which, as a group, they cannot (Malkiel, 2016). A purchase of stock X, recommended by a broker who judges this to be the time to buy, is usually balanced by a sale made by someone who judges this to be the time to sell. Despite their confidence, buyer and seller cannot both be right. And it is overconfidence that so often leads us to succumb to a planning fallacy—overestimating our future leisure time and income (Zauberman & Lynch, 2005). Students and others often expect to finish assignments ahead of schedule (Buehler et al., 1994, 2002). In fact, such projects generally take about twice the predicted time. Anticipating how much more time we will have next month, we happily accept invitations. And believing we’ll surely have more money next year, we take out loans or buy on credit. Despite our past overconfident predictions, we remain overly confident of our next prediction.

Predict your own behavior When will you finish reading this module?

Overconfidence—the bias that Kahneman (2015), if given a magic wand, would most like to eliminate—can feed extreme political views. History is full of leaders who, when waging war, were more confident than correct. One research team tested 743 analysts’ ability to predict future events—predictions that typically are overconfident. Those whose predictions most often failed tended to be inflexible and closed-minded (Mellers et al., 2015). Ordinary citizens with only a shallow understanding of complex proposals, such as for cap-and-trade carbon emissions or a flat tax, may also express strong views. (Sometimes the less we know, the more definite we sound.) Asking such people to explain the details of these policies exposes them to their own ignorance, which in turn leads them to express more moderate views (Fernbach et al., 2013). To confront one’s own ignorance is to become wiser.

Nevertheless, overconfidence sometimes has adaptive value. Believing that their decisions are right and they have time to spare, self-confident people tend to live more happily. They make tough decisions more easily, and they seem competent (Anderson, C. A., et al., 2012). Given prompt and clear feedback, we can also learn to be more realistic about the accuracy of our judgments (Fischhoff, 1982). That’s true of weather forecasters: Extensive feedback has enabled them to estimate their forecast accuracy (“a 60 percent chance of rain”). The wisdom to know when we know a thing and when we do not is born of experience.

“ When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it; this is knowledge.”

Confucius (551–479 B.C.E.), Analects

Belief Perseverance

Our overconfidence is startling. Equally so is our belief perseverance—our tendency to cling to our beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. A classic study of belief perseverance engaged people with opposing views of capital punishment (Lord et al., 1979). After studying two supposedly new research findings, one supporting and the other refuting the claim that the death penalty deters crime, each side was more impressed by the study supporting its own beliefs. And each readily disputed the other study. Thus, showing the pro- and anti-capital-punishment groups the same mixed evidence actually increased their disagreement. Rather than using evidence to draw conclusions, they used their conclusions to assess evidence—a phenomenon also known as motivated reasoning.

In other studies and in everyday life, people have similarly welcomed belief-supportive evidence—about climate change, same-sex marriage, or politics—while discounting challenging evidence (Friesen et al., 2015; Sunstein et al., 2016). In the late 1980s, most Democrats believed that inflation had risen under Republican President Reagan (it had dropped). In 2016, two-thirds of Republicans surveyed said that unemployment had increased under President Obama (unemployment had plummeted). In each case, politics overrode facts (Public Policy Polling, 2016). Big time. As an old Chinese proverb says, “Two-thirds of what we see is behind our eyes.”

“I’m sorry, Jeannie, your answer was correct, but Kevin shouted his incorrect answer over yours, so he gets the points.“

To rein in belief perseverance, a simple remedy exists: Consider the opposite. When the same researchers repeated the capital-punishment study, they asked some participants to be “as objective and unbiased as possible” (Lord et al., 1984). The plea did nothing to reduce biased evaluations of evidence. They also asked another group to consider “whether you would have made the same high or low evaluations had exactly the same study produced results on the other side of the issue.” Having imagined and pondered opposite findings, these people became much less biased.

The more we come to appreciate why our beliefs might be true, the more tightly we cling to them. Once we have explained to ourselves why candidate X or Y will be a better commander-in-chief, we tend to ignore evidence undermining our belief. As we will see in Unit XIV, once beliefs form and get justified, it takes more compelling evidence to change them than it did to create them. Prejudice persists. Beliefs often persevere.

The Effects of Framing

Framing—the way we present an issue—can be a powerful tool of persuasion. Governments know this. People are more supportive of “gun safety” than “gun control” laws, more welcoming of “undocumented workers” than of “illegal aliens,” more agreeable to a “carbon offset fee” than to a “carbon tax,” and more accepting of “enhanced interrogation” than of “torture.” And consider how the framing of options can nudge people toward beneficial decisions (Bohannon, 2016; Fox & Tannenbaum, 2015; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008):

- Choosing to live or die. Imagine two surgeons explaining the risk of an upcoming surgery. One explains that during this type of surgery, 10 percent of people die. The other explains that 90 percent survive. The information is the same. The effect is not. In real-life surveys, patients and physicians overwhelmingly say the risk is greater when they hear that 10 percent die (Marteau, 1989; McNeil et al., 1988; Rothman & Salovey, 1997).

- Becoming an organ donor. In many European countries, as well as in the United States, people renewing their driver’s license can decide whether to be organ donors. In some countries, the default option is Yes, but people can opt out. Nearly 100 percent of the people in opt-out countries have agreed to be donors. In countries where the default option is No, most do not agree to be donors (Hajhosseini et al., 2013; Johnson & Goldstein, 2003).

- Opting to save for retirement. U.S. companies once required employees who wanted to contribute to a retirement plan to choose a lower take-home pay, which few people did. Thanks to a new law, they can now automatically enroll their employees in the plan but allow them to opt out. Either way, the decision to contribute is the employee’s. But under the new “opt-out” arrangement, enrollments in one analysis of 3.4 million workers soared from 59 to 86 percent (Rosenberg, 2010). Britain’s 2012 change to an opt-out framing similarly led to 5 million more retirement savers (Halpern, 2015).

The point to remember: Framing can nudge our attitudes and decisions.

The Perils and Powers of Intuition

We have seen how our unreasoned intuition can plague our efforts to solve problems, assess risks, and make wise decisions. The perils of intuition can persist even when people are offered extra pay for thinking smart, even when they are asked to justify their answers, and even among expert physicians, clinicians, and U.S. federal intelligence agents (Reyna et al., 2014; Shafir & LeBoeuf, 2002; Stanovich et al., 2013). Very smart people can make not-so-smart judgments.

So, are our heads indeed filled with straw? Good news: Cognitive scientists are also revealing intuition’s powers. For example:

- Intuition is recognition born of experience. It is implicit (unconscious) knowledge—what we’ve recorded in our brains but can’t fully explain (Chassy & Gobet, 2011; Gore & Sadler-Smith, 2011). We see this ability to size up a situation and react in an eyeblink in chess masters playing speed chess, as they intuitively know the right move (Burns, 2004). We see it in the smart and quick judgments of experienced nurses, firefighters, art critics, and car mechanics. We see it in skilled athletes who react without thinking. Indeed, conscious thinking may disrupt well-practiced movements, leading skilled athletes to choke under pressure, as when shooting free throws (Beilock, 2010). And we would see this instant intuition in you, too, for anything in which you have developed knowledge based on experience.

- Intuition is usually adaptive, enabling quick reactions. Our fast and frugal heuristics let us intuitively assume that fuzzy-looking objects are far away—which they usually are, except on foggy mornings. Our learned associations surface as gut feelings, right or wrong: Seeing a stranger who looks like someone who has harmed or threatened us in the past, we may automatically react with distrust. Newlyweds’ implicit attitudes toward their new spouses likewise predict their future marital happiness (McNulty et al., 2013).

- Intuition is huge. Recall from Module 16 that through selective attention, we can focus our conscious awareness on a particular aspect of all we experience. Our mind’s unconscious track, however, makes good use intuitively of what we are not consciously processing. Unconscious, automatic influences are constantly affecting our judgments (Custers & Aarts, 2010). Consider: Most people guess that the more complex the choice, the smarter it is to make decisions rationally rather than intuitively (Inbar et al., 2010). Actually, in making complex decisions, we sometimes benefit by letting our brain work on a problem without consciously thinking about it (Strick et al., 2010, 2011). In one series of experiments, three groups of people read complex information (for example, about apartments or European football matches). Those in the first group stated their preference immediately after reading information about four possible options. The second group, given several minutes to analyze the information, made slightly smarter decisions. But wisest of all, in several studies, were those in the third group, whose attention was distracted for a time, enabling their minds to engage in automatic, unconscious processing of the complex information. The practical lesson: Letting a problem incubate while we attend to other things can pay dividends (Dijksterhuis & Strick, 2016). Facing a difficult decision involving a lot of facts, we’re wise to gather all the information we can, and then say, “Give me some time not to think about this, even to sleep on it.” Thanks to our ever-active brain, nonconscious thinking (reasoning, problem solving, decision making, planning) can be surprisingly astute (Creswell et al., 2013; Hassin, 2013; Lin & Murray, 2015).

Critics note that some studies have not found the supposed power of unconscious thought, and they remind us that deliberate, conscious thought also furthers smart thinking (Newell, 2015; Nieuwenstein et al., 2015; Phillips et al., 2016). In challenging situations, superior decision makers, including chess players, take time to think (Moxley et al., 2012). And with many sorts of problems, deliberative thinkers are aware of the intuitive option, but know when to override it (Mata et al., 2013). Consider two problems:

- A bat and a ball together cost 110 cents. The bat costs 100 cents more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

- If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

“ The heart has its reasons which reason does not know.”

Blaise Pascal, Pensees, 1670

Most people’s intuitive responses—10 cents and 100 minutes—are wrong, and a few moments of deliberate thinking reveals why.3

The bottom line: Our two-track mind makes sweet harmony as smart, critical thinking listens to the creative whispers of our vast unseen mind and then evaluates evidence, tests conclusions, and plans for the future.

For a summary of some key ideas from this section, see Table 35.1.

| Process or Strategy | Description | Powers | Perils |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | Methodical rule or procedure | Guarantees solution | Requires time and effort |

| Heuristic | Simple thinking shortcut, such as the availability heuristic (which estimates likelihood based on how easily events come to mind) | Lets us act quickly and efficiently | Puts us at risk for errors |

| Insight | Sudden Aha! reaction | Provides instant realization of solution | May not happen |

| Confirmation bias | Tendency to search for support for our own views and ignore contradictory evidence | Lets us quickly recognize supporting evidence | Hinders recognition of contradictory evidence |

| Fixation | Inability to view problems from a new angle | Focuses thinking on familiar solutions | Hinders creative problem solving |

| Intuition | Fast, automatic feelings and thoughts | Is based on our experience: huge and adaptive | Can lead us to overfeel and underthink |

| Overconfidence | Overestimating the accuracy of our beliefs and judgments | Allows us to be happy and to make decisions easily | Puts us at risk for errors |

| Belief perseverance | Ignoring evidence that proves our beliefs are wrong | Supports our enduring beliefs | Closes our mind to new ideas |

| Framing | Wording a question or statement so that it evokes a desired response | Can influence others’ decisions | Can produce a misleading result |

| Creativity | Ability to innovate valuable ideas | Produces new insights and products | May distract from structured, routine work |