TABLE 1-1. ABCDE ACRONYM

KNOWLEDGE COMPETENCIES

1. Discuss the importance of a consistent and systematic approach to assessment of progressive care patients and their families.

2. Identify the assessment priorities for different stages of an acute illness:

• Prearrival assessment

• Arrival quick check

• Comprehensive initial assessment

• Ongoing assessment

3. Describe how the assessment is altered based on the patient’s clinical status.

The assessment of acutely ill patients and their families is an essential competency for progressive care practitioners. Information obtained from an assessment identifies the immediate and future needs of the patient and family so a plan of care can be initiated to address or resolve these needs.

Traditional approaches to patient assessment include a complete evaluation of the patient’s history and a comprehensive physical examination of all body systems. This approach is ideal, though progressive care clinicians must balance the need to gather data while simultaneously prioritizing and providing care to acutely ill patients who may either be improving or decompensating. Traditional approaches and techniques for assessment must be modified in progressive care to balance the need for information, while considering the acute nature of the patient and family’s situation.

This chapter outlines an assessment approach that recognizes the dynamic nature of an acute illness. This approach emphasizes the collection of assessment data in a phased or staged manner consistent with patient care priorities. The components of the assessment can be used as a generic template for assessing most progressive care patients and families. The assessment can then be individualized by adding more specific assessment requirements depending on the specific patient diagnosis. These specific components of the assessment are identified in subsequent chapters.

Crucial to developing competence in assessing progressive care patients and their families is a consistent and systematic approach to assessments. Without this approach, it would be easy to miss subtle signs or details that may identify an actual or potential problem and also indicate a patient’s changing status. Assessments should focus first on the patient, then on the technology. The patient needs to be the focal point of the progressive care practitioner’s attention, with technology augmenting the information obtained from the direct assessment.

There are two standard approaches to assessing patients—the head-to-toe approach and the body systems approach. Most progressive care nurses use a combination—a systems approach applied in a top-to-bottom manner. The admission and ongoing assessment sections of this chapter are presented with this combined approach in mind.

Assessing the progressive care patient and family begins from the moment the nurse is made aware of the pending admission or transfer of the patient and continues until transitioning to the next phase of care. The assessment process can be viewed as four distinct stages: (1) prearrival, (2) arrival quick check (“just the basics”), (3) comprehensive initial assessment, and (4) ongoing assessment.

Patients admitted to a progressive care unit may be transitioning from a more intensive level of care, as they become more stable and improve in condition. Conversely, they may be transferred from a lower level of care, as their physiologic status may be deteriorating. In either case, the progressive care patient has the potential to have a rapid change in status. A prearrival assessment begins the moment the information is received about the upcoming admission of the patient to the progressive care unit. This notification comes from the initial healthcare team contact. The contact may be a transfer from another facility or a transfer from other areas within the hospital such as the emergency room, operating room, the intensive care unit (ICU), or medical/surgical nursing unit. The prearrival assessment paints the initial picture of the patient and allows the progressive care nurse to begin anticipating the patient’s physiologic and psychological needs. This assessment also allows the progressive care nurse to determine the appropriate resources that are needed to care for the patient. The information received in the prearrival phase is crucial because it allows the progressive care nurse to adequately prepare the environment to meet the specialized needs of the patient and family.

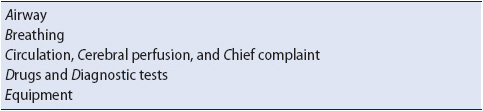

An arrival quick check assessment is obtained immediately upon arrival and is based on assessing the parameters represented by the ABCDE acronym (Table 1-1). The arrival quick check assessment is a quick overview of the adequacy of ventilation and perfusion to ensure early intervention for any life-threatening situations. The arrival quick check is a high-level view of the patient, but is essential because it validates that basic cardiac and respiratory function is sufficient, and can be used as a baseline for potential future changes in a condition.

TABLE 1-1. ABCDE ACRONYM

A comprehensive assessment is performed as soon as possible, with the timing dictated by the degree of physiologic stability and emergent treatment needs of the patient. If the patient is being admitted directly to the progressive care unit from outside the hospital, the comprehensive assessment is an in-depth assessment of the past medical and social history and a complete physical examination of each body system. If the patient is being transferred to the progressive care unit from another area in the hospital, the comprehensive assessment includes a review of the admission assessment data and comparison to the current assessment of the patient. The comprehensive assessment is vital to successful outcomes because it provides the nurse invaluable insight into proactive interventions that may be needed.

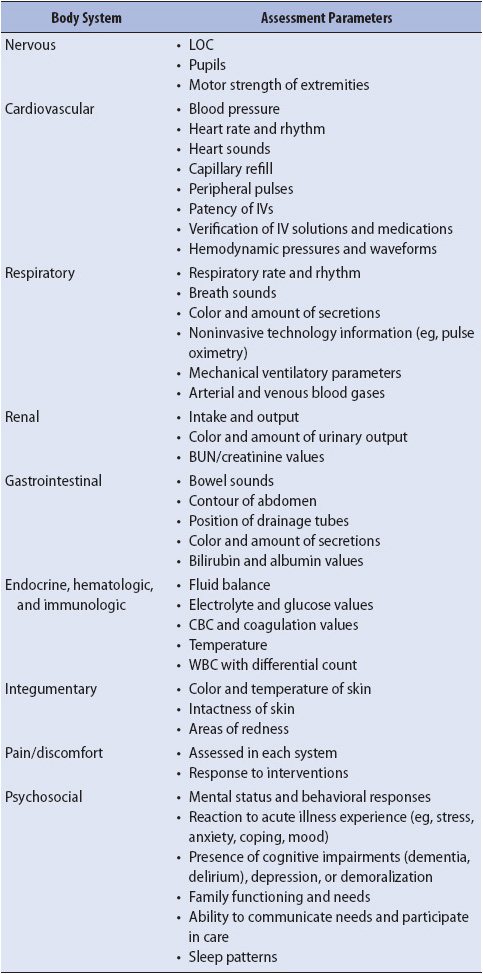

After the baseline comprehensive assessment is completed, ongoing assessments—an abbreviated version of the comprehensive assessment—are performed at varying intervals. The assessment parameters outlined in this section are usually completed for all patients, in addition to other ongoing assessment requirements related to the patient’s specific condition, treatments, and response to therapy.

Admission of an acutely ill patient can be a chaotic event with multiple disciplines involved in many activities. It is at this time, however, that health-care providers must be particularly cognizant of accurate assessments and data gathering to ensure the patient is cared for safely with appropriate interventions. Obtaining inaccurate information on admission can lead to ongoing errors that may not be easily rectified or discovered and lead to poor patient outcomes.

Obtaining information from an acutely ill patient may be difficult, if possible at all. If the patient is unable to supply information, other sources must be utilized such as family members, electronic health records (EHRs), past medical records, transport records, or information from the patient’s belongings. Of particular importance at admission is obtaining accurate patient identification, as well as past medical history including any known allergies. Current medication regimens are extremely helpful if feasible, as they can provide clues to the patient’s medical condition and perhaps contributing factors to the current condition.

With the increasing use of EHRs, there are improving opportunities for timely access to past and current medical history information of patients. Healthcare providers may have access to both inpatient and outpatient records within the same healthcare system, assisting them to quickly identify the patient’s most recent medication regimen and laboratory and diagnostic results. In addition, many healthcare systems within the same geographic locations are working together to make available intersystem access to medical records of patients being treated at multiple healthcare institutions. This is particularly beneficial when patients are unable to articulate imperative medical information including advance directives, allergies, and next of kin.

Careful physical assessment on admission to the progressive care unit is pivotal for providing prevention and/or early treatment for complications associated with the illness. Of particular importance is the assessment of risk for pressure ulcer formation, alteration in mental status, and/or falls. Risks associated with accurate patient identification never lessen, particularly as these relate to interventions such as performing invasive procedures, medication administration, blood administration, and obtaining laboratory tests. Nurses need to be cognizant of safety issues as treatment begins as well; for example, accurate programming of pumps infusing high-risk medications is essential. It is imperative that nurses use all safety equipment available to them such as pre-programmed drug libraries in infusion pumps and bar coding technology. Healthcare providers must also ensure the safety of invasive procedures that may be performed emergently.

A prearrival assessment begins when information is received about the pending arrival of the patient. The prearrival report, although abbreviated, provides key information about the chief complaint, diagnosis, or reason for admission, pertinent history details, and physiologic stability of the patient (Table 1-2). It also contains the gender and age of the patient and information on the presence of invasive tubes and lines, medications being administered, other ongoing treatments, and pending or completed laboratory or diagnostic tests. It is also important to consider the potential isolation requirements for the patient (eg, neutropenic precautions or special respiratory isolation). Being prepared for isolation needs prevents potentially serious exposures to the patient, roommates, or the healthcare providers. This information assists the clinician in anticipating the patient’s physiologic and emotional needs prior to admission or transfer and in ensuring that the bedside environment is set up to provide all monitoring, supply, and equipment needs prior to the patient’s arrival.

TABLE 1-2. SUMMARY OF PREARRIVAL AND ARRIVAL QUICK

CHECK ASSESSMENTS

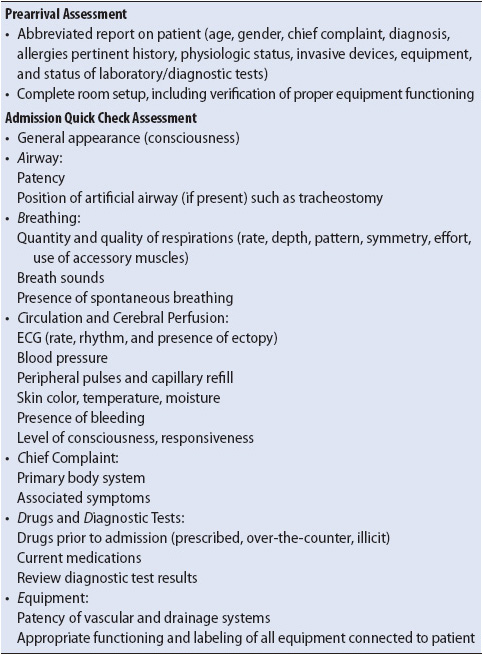

Many progressive care units have a standard room setup, guided by the major diagnosis-related groups of patients each unit receives. The standard monitoring and equipment list for each unit varies; however, there are certain common requirements (Table 1-3). The standard room setup is modified for each admission to accommodate patient-specific needs (eg, additional equipment, intravenous [IV] fluids, medications). Proper functioning of all bedside equipment should be verified prior to the patient’s arrival.

TABLE 1-3. EQUIPMENT FOR STANDARD ROOM SETUP

It is also important to prepare the medical records forms, which usually consist of paper flow sheets or computerized data entry system to record vital signs, intake and output, medication administration, patient care activities, and patient assessment. The prearrival report may suggest pending procedures, necessitating the organization of appropriate supplies at the bedside. Having the room prepared and all equipment available facilitates a rapid, smooth, and safe admission of the patient.

From the moment the patient arrives in the progressive care unit setting, his or her general appearance is immediately observed and assessment of ABCDEs is quickly performed (see Table 1-1). The seriousness of the problem(s) is determined so any urgent needs can be addressed first. The patient is connected to the appropriate monitoring and support equipment, medications being administered are verified, and essential laboratory and diagnostic tests are ordered. Simultaneously with the ABCDE assessment, the patient’s nurse must validate that the patient is appropriately identified through a hospital wristband, personal identification, or family identification. In addition, the patient’s allergy status is verified, including the type of reaction that occurs and what, if any, treatment is used to alleviate the allergic response.

There may be other healthcare professionals present to receive the patient and assist with arrival tasks. The progressive care nurse, however, is the leader of the receiving team. While assuming the primary responsibility for assessing the ABCDEs, the progressive care nurse directs the team in completing delegated tasks, such as changing over to the unit equipment or attaching monitoring cables. Without a leader of the receiving team, care can be fragmented and vital assessment clues overlooked.

The progressive care nurse rapidly assesses the ABCDEs in the sequence outlined in this section. If any aspect of this preliminary assessment deviates from normal, interventions are immediately initiated to address the problem before continuing with the arrival quick check assessment. Additionally, regardless of whether the patient appears to be conscious or not, it is important to talk to him or her throughout this admission process regarding what is occurring with each interaction and intervention.

Patency of the patient’s airway is verified by having the patient speak, watching the patient’s chest rise or fall, or both. If the airway is compromised, verify that the head has been positioned properly to prevent the tongue from occluding the airway. Inspect the upper airway for the presence of blood, vomitus, and foreign objects before inserting an oral airway if one is needed. If the patient already has an artificial airway, such as a cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy, ensure that the airway is secured properly. Note the position of the tracheostomy and size marking to assist future comparisons for proper placement. Suctioning of the upper airway, either through the oral cavity or artificial airway, may be required to ensure that the airway is free from secretions. Note the amount, color, and consistency of secretions removed.

Note the rate, depth, pattern, and symmetry of breathing; the effort it is taking to breathe; the use of accessory muscles; and, if mechanically ventilated, whether breathing is in synchrony with the ventilator. Observe for nonverbal signs of respiratory distress such as restlessness, anxiety, or change in mental status. Auscultate the chest for presence of bilateral breath sounds, quality of breath sounds, and bilateral chest expansion. Optimally, both anterior and posterior breath sounds are auscultated, but during this arrival quick check assessment, time generally dictates that just the anterior chest is assessed. If noninvasive oxygen saturation monitoring is available, observe and quickly analyze the values.

If chest tubes are present, note whether they are pleural or mediastinal chest tubes. Ensure that they are connected to suction, if appropriate, and are not clamped or kinked. Assess whether they are functioning properly (eg, airleak, fluid fluctuation with respirations) and the amount and character of the drainage.

Assess circulation by quickly palpating a pulse and viewing the electrocardiogram (ECG) and monitor for the heart rate, rhythm, and presence of ectopy if ECG monitoring is ordered. Obtain blood pressure and temperature. Assess peripheral perfusion by evaluating the color, temperature, and moisture of the skin along with capillary refill. Based on the prearrival report and reason for admission, there may be a need to inspect the body for any signs of blood loss and determine if active bleeding is occurring.

Evaluating cerebral perfusion in the arrival quick check assessment is focused on determining the functional integrity of the brain as a whole, which is done by rapidly evaluating the gross LOC. Evaluate whether the patient is alert and aware of his or her surroundings, whether it takes a verbal or painful stimulus to obtain a response, or whether the patient is unresponsive. Observing the response of the patient during movement from the stretcher to the progressive care unit bed can supply additional information about the LOC. Note whether the patient’s eyes are open and watching the events around him or her; for example, does the patient follow simple commands such as “Place your hands on your chest” or “Slide your hips over”? If the patient is unable to talk because of trauma or the presence of an artificial airway, note whether his or her head nods appropriately to questions.

Optimally, the description of the chief complaint is obtained from the patient, but this may not be realistic. The patient may be unable to respond or may not speak English. Data may need to be gathered from family, friends, or bystanders, or from the completed admission database if the patient has been transferred from another area in the hospital. If the patient or family cannot speak English, an approved hospital translator should be contacted to help with the interview and subsequent evaluations and communication. It is not advised to use family or friends to translate for a non-English speaking patient for reasons such as protection of the patient’s privacy, the likelihood that family will not understand appropriate medical terminology for translation, and to avoid well-intentioned but potential bias in translating back and forth for the patient.

In the absence of a history source, practitioners must depend exclusively on the physical findings (eg, presence of medication patches, permanent pacemaker, or old surgery scars), knowledge of pathophysiology, and access to prior paper or electronic medical records to identify the potential causes of the admission.

Assessment of the chief complaint focuses on determining the body systems involved and the extent of associated symptoms. Additional questions explore the time of onset, precipitating factors, and severity. Although the arrival quick check phase is focused on obtaining a quick overview of the key life-sustaining systems, a more in-depth assessment of a particular system may need to be done at this time; for example, in the prearrival case study scenario presented, completion of the ABCDEs is followed quickly by more extensive assessment of both the nervous and respiratory systems.

Information about infusing medications and diagnostic tests is integrated into the priority of the arrival quick check. If IV access is not already present, it should be immediately obtained and intake and output records started. If IV medications are presently being infused, check the drug(s) and verify the correct infusion of the desired dosage and rate.

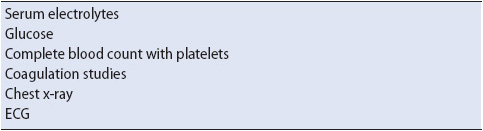

Determine the latest results of any diagnostic tests already performed. Augment basic screening tests (Table 1-4) with additional tests appropriate to the underlying diagnosis, chief complaint, transfer status, and recent procedures. Review any available laboratory or diagnostic data for abnormalities or indications of potential problems that may develop. The abnormal laboratory and diagnostic data for specific pathologic conditions will be covered in subsequent chapters.

TABLE 1-4. COMMON DIAGNOSTIC TESTS OBTAINED DURING ARRIVAL QUICK CHECK ASSESSMENT

Quickly evaluate all vascular and drainage tubes for location and patency, and connect them to appropriate monitoring or suction devices. Note the amount, color, consistency, and odor of drainage secretions. Verify the appropriate functioning of all equipment attached to the patient and label as required. While connecting the monitoring and care equipment, it is important for the nurse to continue assessing the patient’s respiratory and cardiovascular status until it is clear that all equipment are functioning appropriately and can be relied on to transmit accurate patient data.

The arrival quick check assessment is accomplished in a matter of a few minutes. After completion of the ABCDEs assessment, the comprehensive assessment begins. If at any phase during the arrival quick check a component of the ABCDEs has not been stabilized and controlled, energy is focused first on resolving the abnormality before proceeding to the comprehensive admission assessment.

After the arrival, quick check assessment is complete, and if the patient requires no urgent intervention, there may now be time for a more thorough report from the healthcare providers transferring the patient to the progressive care unit. It is important to note that handoffs with transitions of care are possible intervals when safety gaps may occur. Omission of pertinent information or miscommunication at this critical juncture can result in patient care errors. Use of a standardized handoff format—such as the “SBAR” format which includes communication of the Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendations—can minimize the potential for miscommunication. Use the handoff as an opportunity to confirm your observations such as dosage of infusing medications, abnormalities found on the quick check assessment, and any potential inconsistencies noted between your assessment and the prearrival report. It is easier to clarify questions while the transporters are still present, if possible.

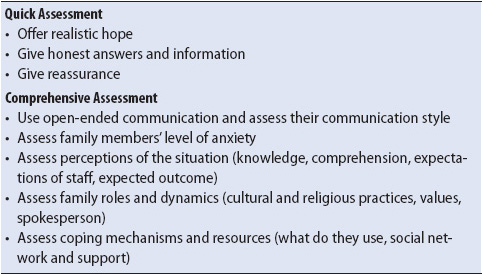

This may also be an opportunity for introductory interactions with family members or friends, if present. Introduce yourself, offer reassurance, and confirm the intention to give the patient the best care possible (Table 1-5). If feasible, allow them to stay with the patient in the room during the arrival process. If this is not possible, give them an approximate time frame when they can expect to receive an update from you on the patient’s condition. Have another member of the healthcare team escort them to the appropriate waiting area.

TABLE 1-5. EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: FAMILY NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Comprehensive assessments determine the physiologic and psychosocial baseline so that future changes can be compared to determine whether the status is improving or deteriorating. The comprehensive assessment also defines the patient’s pre-event health status, determining problems or limitations that may impact patient status during this admission as well as potential issues for future transitioning of care. The content presented in this section is a template to screen for abnormalities or determine the extent of injury or disease. Any abnormal findings or changes from baseline warrant a more in-depth evaluation of the pertinent system.

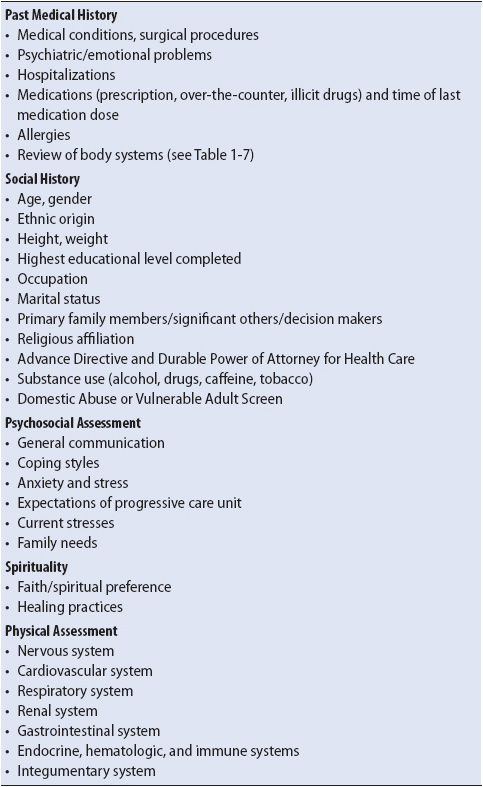

The comprehensive assessment includes the patient’s medical and brief social history, and physical examination of each body system. The comprehensive assessment of the progressive care patient is similar to admission assessments for medical-surgical patients. This section describes only those aspects of the assessment that are unique to progressive care patients or require more extensive information than is obtained from a medical-surgical patient. The entire assessment process is summarized in Tables 1-6 and 1-7.

TABLE 1-6. SUMMARY OF COMPREHENSIVE INITIAL

ASSESSMENT REQUIREMENTS

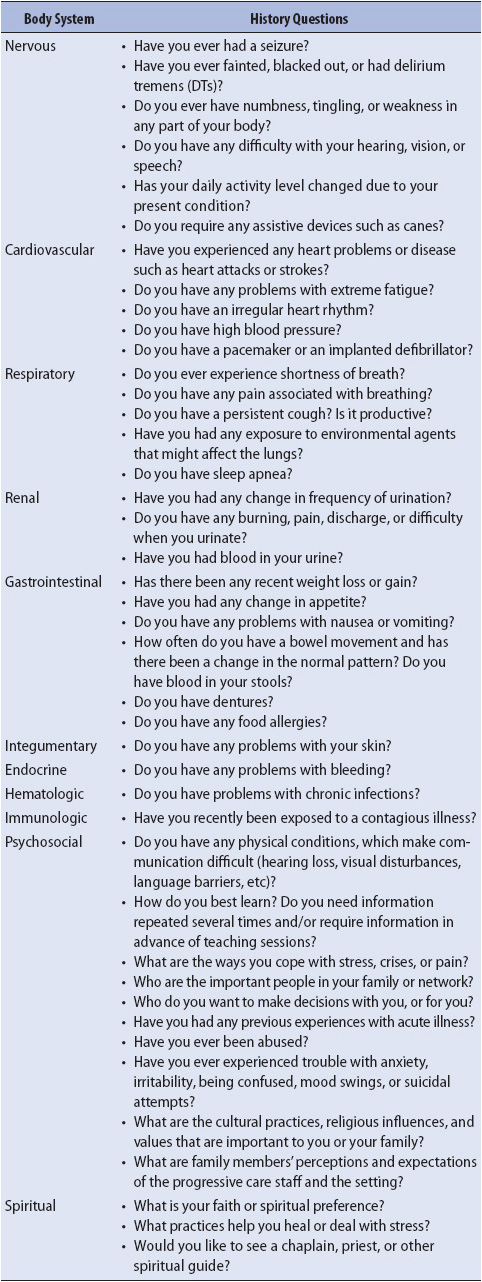

TABLE 1-7. SUGGESTED QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW OF PAST HISTORY CATEGORIZED BY BODY SYSTEM

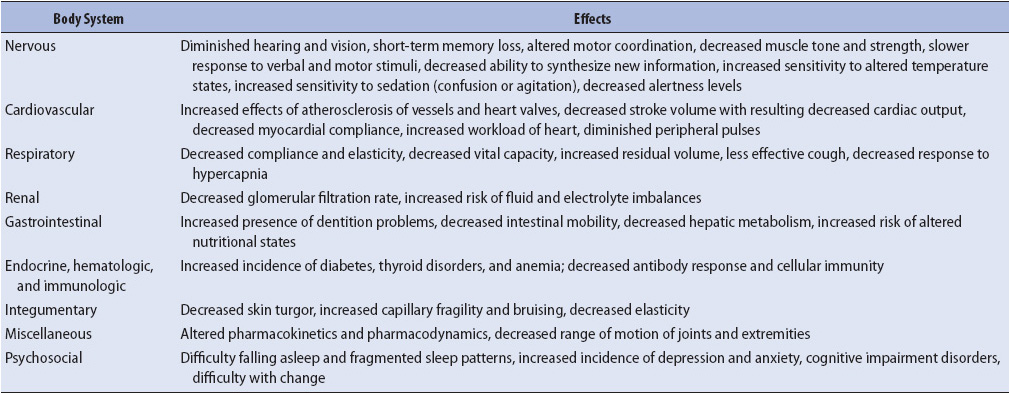

Changing demographics of progressive care units indicate that an increasing proportion of patients are elderly, requiring assessments to incorporate the effects of aging. Although assessment of the aging adult does not differ significantly from the younger adult, understanding how aging alters the physiologic and psychological status of the patient is important. Key physiologic changes pertinent to the progressive care elderly adult are summarized in Table 1-8. Additional emphasis must also be placed on the past medical history because the aging adult frequently has multiple coexisting illnesses and is taking several prescriptive and over-the-counter medications. Social history must address issues related to home environment, support systems, and self-care abilities. The interpretation of clinical findings in the elderly must also take into consideration the fact that the coexistence of several disease processes and the diminished reserves of most body systems often result in more rapid physiologic deterioration than in younger adults.

TABLE 1-8. PHYSIOLOGIC EFFECTS OF AGING

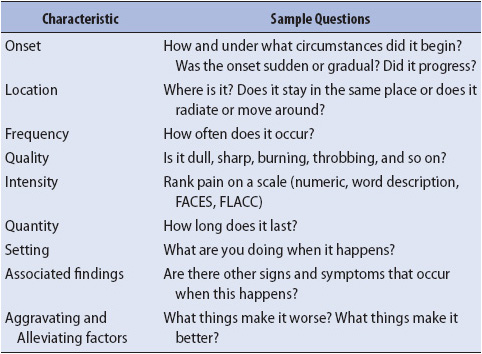

If the patient is being directly admitted to the progressive care unit, it is important to determine prior medical and surgical conditions, hospitalization, medications, and symptoms besides the primary event that brought the patient to the hospital (see Table 1-7). In reviewing medication use, ensure assessment of over-the-counter medication use as well as any herbal or alternative supplements. For every positive symptom response, additional questions should be asked to explore the characteristics of that symptom (Table 1-9). If the patient is a transfer from another area in the hospital, review the admission assessment information, and clarify as needed with the patient and family. Be aware of opportunities for health teaching and transition planning needs for discharge to home or to a rehabilitation facility.

TABLE 1-9. IDENTIFICATION OF SYMPTOM CHARACTERISTICS

Inquire about the use and abuse of caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, and other substances. Because the use of these agents can have major implications for the progressive care patient, questions are aimed at determining the frequency, amount, and duration of use. Honest information regarding alcohol and substance abuse, however, may not be always forthcoming. Alcohol use is common in all age groups. Phrasing questions about alcohol use by acknowledging this fact may be helpful in obtaining an accurate answer (eg, “How much alcohol do you drink?” vs “Do you drink alcohol and how much?”). Family or friends might provide additional information that might assist in assessing these parameters. The information revealed during the social history can often be verified during the physical assessment through the presence of signs such as needle track marks, nicotine stains on teeth and fingers, or the smell of alcohol on the breath.

Patients should also be asked about physical and emotional safety in their home environment in order to uncover potential domestic or elder abuse. It is best if patients can be assessed for vulnerability when they are alone to prevent placing them in a position of answering in front of family members or friends who may be abusive. Ask questions such as “Is anyone hurting you?” or “Do you feel safe at home?” in a non-threatening manner. Any suspicion of abuse or vulnerability should result in a consultation with social work to determine additional assessments.

The physical assessment section is presented in the sequence in which the combined system, head-to-toe approach, is followed. Although content is presented as separate components, generally the history questions are integrated into the physical assessment. The physical assessment section uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, and palpation. Although percussion is a common technique in physical examinations, it is infrequently used in progressive care patients.

Pain assessment is generally linked to each body system rather than considered as a separate system category; for example, if the patient has chest pain, assessment and documentation of that pain is incorporated into the cardiovascular assessment. Rather than have general pain assessment questions repeated under each system assessment, they are presented here.

Pain and discomfort are clues that alert both the patient and the progressive care nurse that something is wrong and needs prompt attention. Pain assessment includes differentiating acute from chronic pain, determining related physiologic symptoms, and investigating the patient’s perceptions and emotional reactions to the pain. Explore the qualities and characteristics of the pain by using the questions listed in Table 1-9. Pain is a subjective assessment, and progressive care practitioners sometimes struggle with applying their own values when attempting to evaluate the patient’s pain. To resolve this dilemma, use the patient’s own words and descriptions of the pain whenever possible and use a patient-preferred pain scale (see Chapter 6, Pain and Sedation Management) to evaluate pain levels objectively and consistently.

The nervous system is the master computer of all systems and is divided into the central and peripheral nervous systems. With the exception of the peripheral nervous system’s cranial nerves, almost all attention in the acutely ill patient is focused on evaluating the central nervous system (CNS). The physiologic and psychological impact of an acute illness, in addition to pharmacologic interventions, frequently alters CNS functioning. The single most important indicator of cerebral functioning is the LOC.

Assess pupils for size, shape, symmetry, and reactivity to direct light. When interpreting the implication of altered pupil size, remember that certain medications such as atropine, morphine, or illicit drugs may affect pupil size. Baseline pupil assessment is important even in patients without a neurologic diagnosis because some individuals have unequal or unreactive pupils normally. If pupils are not checked as a baseline, a later check of pupils during an acute event could inappropriately attribute pupil abnormalities to a pathophysiologic event.

Level of consciousness and pupil assessment are followed by motor function assessment of the upper and lower extremities for symmetry and quality of strength. Traditional motor strength exercises include having the patient squeeze the nurse’s hands and plantar flexing and dorsiflexing of the patient’s feet. If the patient cannot follow commands, an estimate of strength and quality of movements can be inferred by observing activities such as pulling against restraints or thrashing around. If the patient has no voluntary movement or is unresponsive, check the gag reflex.

If head trauma is involved or suspected, check for signs of fluid leakage around the nose or ears, differentiating between cerebral spinal fluid and blood (see Chapter 12, Neurologic System). Complete cranial nerve assessment is rarely warranted, with specific cranial nerve evaluation based on the injury or diagnosis; for example, extraocular movements are routinely assessed in patients with facial trauma. Sensory testing is a baseline standard for spinal cord injuries, extremity trauma, and epidural analgesia.

Now, it is a good time to assess mental status if the patient is responsive. Assess orientation to person, place, and time. Ask the patient to state their understanding of what is happening. As you ask the questions, observe for eye contact, pressured or muted speech, and rate of speech. Rate of speech is usually consistent with the patient’s psychomotor status. Underlying cognitive impairments such as dementia and developmental delays are typically exacerbated during an acute illness due to physiologic changes, medications, and environmental changes. It may be necessary to ascertain baseline level of functioning from the family.

It is also important to assess patients for the risk of a fall. With the goal of increasing the mobility and independence of progressive care patients, it is imperative that the nurse understand the fall risk for each individual patient and implement interventions to minimize the potential for a fall.

Laboratory data pertinent to the nervous system include serum and urine electrolytes and osmolarity and urinary specific gravity. Drug toxicology and alcohol levels may be evaluated to rule out potential sources of altered LOC.

The cardiovascular system assessment is directed at evaluating central and peripheral perfusion. Revalidate your admission quick check assessment of the blood pressure, heart rate, and rhythm. If the patient is being monitored, assess the ECG for T-wave abnormalities and ST-segment changes and determine the PR, QRS, and QT intervals and the QTc measurements. Note any abnormalities or indications of myocardial damage, electrical conduction problems, and electrolyte imbalances. Note the pulse pressure. If treatment decisions will be based on the cuff pressure, blood pressure is taken in both arms. If an arterial pressure line is in place, compare the arterial line pressure to the cuff pressure. In either case, if a 10- to 15-mm Hg difference exists, a decision must be made as to which pressure is the most accurate and will be followed for future treatment decisions. If a different method is used inconsistently, changes in blood pressure might be inappropriately attributed to physiologic changes rather than anatomic differences.

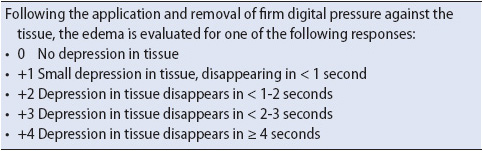

Note the color and temperature of the skin, with particular emphasis on lips, mucous membranes, and distal extremities. Also evaluate nail color and capillary refill. Inspect for the presence of edema, particularly in the dependent parts of the body such as feet, ankles, and sacrum. If edema is present, rate the quality of edema by using a 0 to +4 scale (Table 1-10).

TABLE 1-10. EDEMA RATING SCALE

Auscultate heart sounds for S1 and S2 quality, intensity, and pitch, and for the presence of extra heart sounds, murmurs, clicks, or rubs. Listen to one sound at a time, consistently progressing through the key anatomic landmarks of the heart each time. Note whether there are any changes with respiration or patient position.

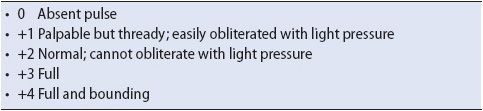

Palpate the peripheral pulses for amplitude and quality, using the 0 to +4 scale (Table 1-11). Check bilateral pulses simultaneously, except the carotid, comparing each pulse to its partner. If the pulse is difficult to palpate, an ultrasound (Doppler) device should be used. To facilitate finding a weak pulse for subsequent assessments, mark the location of the pulse with an indelible pen. It is also helpful to compare quality of the pulses to the ECG to evaluate the perfusion of heartbeats.

TABLE 1-11. PERIPHERAL PULSE RATING SCALE

Electrolyte levels, complete blood counts (CBCs), coagulation studies, and lipid profiles are common laboratory tests evaluated for abnormalities of the cardiovascular system. Cardiac enzyme levels (troponin, creatine kinase MB, β-natriuretic peptide) are obtained for any complaint of chest pain or suspected chest trauma. Drug levels of commonly used cardiovascular medications, such as digoxin, may be warranted for certain types of arrhythmias. A 12-lead ECG may be evaluated, either due to the chief reason for admission (eg, with complaints of chest pain, irregular rhythms, or suspected myocardial bruising from trauma) or as a baseline for future comparison if needed.

Note the type, size, and location of IV catheters, and verify their patency. If continuous infusions of medications such as antiarrhythmics are being administered, ensure that they are being infused into an appropriately sized vessel and are compatible with any piggybacked IV solution.

Verify all monitoring system alarm parameters as active with appropriate limits set. Note the size and location of invasive monitoring lines such as arterial and central venous catheters. Confirm that the appropriate flush solution is hanging and that the correct amount of pressure is applied to the flush solution bag. Level the invasive line to the appropriate anatomic landmark and zero the monitor as needed. Interpret hemodynamic pressure readings against normals and with respect to the patient’s underlying pathophysiology. Assess waveforms to determine the quality of the waveform (eg, dampened or hyperresonant) and whether the waveform appropriately matches the expected characteristics for the anatomic placement of the invasive catheter (see Chapter 4, Hemodynamic Monitoring); for example, a right ventricular waveform for a CVP line indicates a problem with the position of the central venous line that needs to be corrected. Evaluate all cardiovascular devices that are in place as feasible, such as a pacemaker, or any ventricular assist device. Verify and document equipment settings, appropriate function of the device, and the patient response to that device function.

Oxygenation and ventilation are the focal basis of respiratory assessment parameters. Reassess the rate and rhythm of respirations and the symmetry of chest wall movement. If the patient has a productive cough or secretions are suctioned from an artificial airway, note the color, consistency, and amount of secretions. Evaluate whether the trachea is midline or shifted. Inspect the thoracic cavity for shape, anterior-posterior diameter, and structural deformities (eg, kyphosis or scoliosis). Palpate for equal chest excursion, presence of crepitus, and any areas of tenderness or fractures. If the patient is receiving supplemental oxygen, verify the mode of delivery and percentage of oxygen against physician orders.

Auscultate all lobes anteriorly and posteriorly for bilateral breath sounds to determine the presence of air movement and the presence of adventitious sounds such as crackles or wheezes. Note the quality and depth of respirations, and the length and pitch of the inspiratory and expiratory phases.

Arterial blood gases (ABGs) may be used to assess for interpretation of oxygenation, ventilatory status, and acid-base balance. Hemoglobin and hematocrit values are interpreted for impact on oxygenation and fluid balance. If the patient’s condition warrants, the oxygen saturation values may be continuously monitored.

If the patient is connected to a mechanical ventilator, verify the ventilatory mode, tidal volume, respiratory rate, positive end expiratory pressure, and percentage of oxygen against prescribed settings. Observe whether the patient has spontaneous breaths, noting both the rate and average tidal volume of each breath. Note the amount of pressure required to ventilate the patient for later comparisons to determine changes in pulmonary compliance. If the patient has a tracheostomy, note the size and type of tube in place and the location to assist future comparisons for proper placement. If the patient is on biphasic positive airway pressure (BiPAP), note and verify the pressure settings against ordered parameters. Also assess the patient’s tolerance to the full face or nasal mask. Patients frequently exhibit anxiety with BiPAP and have difficulty tolerating the feeling of the mask.

If chest tubes are present, assess the area around the insertion site for crepitus. Note the amount and color of drainage and whether an air leak is present. Verify whether the chest tube drainage system is an underwater seal or is connected to suction.

Urinary characteristics and electrolyte status are the major parameters used to evaluate the function of the kidneys. In conjunction with the cardiovascular system, the renal system’s impact on fluid volume status is also assessed.

Some progressive care patients have a Foley catheter in place to initially evaluate urinary output every 2 to 4 hours. Note the amount and color of the urine and, if warranted, obtain a sample to assess for the abnormal presence of glucose, protein, and blood. Inspect the genitalia for inflammation, swelling, ulcers, and drainage. If suprapubic tubes or a ureterostomy are present, note the position as well as the amount and characteristics of the drainage. Observe whether any drainage is leaking around the drainage tube.

In addition to the urinalysis, serum electrolyte levels, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urinary and serum osmolarity are common diagnostic tests used to evaluate kidney function.

The key factors when reviewing the gastrointestinal system are the nutritional and fluid status. Inspect the abdomen for overall symmetry, noting whether the contour is flat, round, protuberant, or distended. Note the presence of discoloration or striae. Nutritional status is evaluated by looking at the patient’s weight and muscle tone, the condition of the oral mucosa, and laboratory values such as serum albumin and transferrin.

Auscultation of bowel sounds should be done in all four quadrants in a clockwise order, noting the frequency and presence or absence of sounds. Bowel sounds are usually rated as absent, hypoactive, normal, or hyperactive. Before noting absent bowel sounds, a quadrant should be listened to for at least 60 to 90 seconds. Characteristics and frequency of the sounds are noted. After listening for the presence of normal sounds, determine whether any adventitious bowel sounds such as friction rubs, bruits, or hums are present.

Light palpation of the abdomen helps determine areas of fluid, rigidity, tenderness, pain, and guarding or rebound tenderness. Remember to auscultate before palpating because palpation may change the frequency and character of the patient’s peristaltic sounds.

Assess any drainage tube for location and function, and for the characteristics of any drainage. Validate the proper placement of the nasogastric (NG) tube. Ensure patency of any feeding tube or percutaneously placed gastric tubes. Check placement and assess for any drainage or leaking around the tubes. Check emesis and stool for occult blood as appropriate. Evaluate ostomies for location, color of the stoma, and the type of drainage.

The endocrine, hematologic, and immune systems often are overlooked when assessing progressive care patients. The assessment parameters used to evaluate these systems are included under other system assessments, but it is important to consider these systems consciously when reviewing these parameters. Assessing the endocrine, hematologic, and immune systems is based on a thorough understanding of the primary function of each of the hormones, blood cells, or immune components of each of the respective systems.

Assessing the specific functions of the endocrine system’s hormones is challenging because much of the symptomatology related to the hypo- or hypersecretion of the hormones can be found with other systems’ problems. The patient’s history may help differentiate the source, but any abnormal assessment findings detected with regard to fluid balance, metabolic rate, altered LOC, color and temperature of the skin, electrolytes, glucose, and acid-base balance require the progressive care nurse to consider the potential involvement of the endocrine system; for example, are the signs and symptoms of hypervolemia related to cardiac insufficiency or excessive amounts of antidiuretic hormone? Serum blood tests for specific hormone levels may be required to rule out involvement of the endocrine system.

Assessment parameters specific to the hematologic system include laboratory evaluation of the red blood cells (RBCs) and coagulation studies. Diminished RBCs may affect the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood as evidenced by pallor, cyanosis, light-headedness, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Insufficient clotting factors are evidenced by bruising, oozing of blood from puncture sites or mucous membranes, or overt bleeding.

The immune system’s primary function of fighting infection is assessed by evaluating the white cell and differential counts from the CBC, and assessing puncture sites and mucous membranes for oozing drainage and inflamed, reddened areas. Spiking or persistent low-grade temperatures often are indicative of underlying infections. It is important to keep in mind, however, that many progressive care patients have impaired immune systems and the normal response to infection, such as white pus around an insertion site or elevated temperature and WBC, may not be evident.

The skin is the first line of defense against infection so assessment parameters are focused on evaluating the intactness of the skin. Assessing the skin can be undertaken while performing other system assessments; for example, while listening to breath sounds or bowel sounds, the condition of the thoracic cavity or abdominal skin can be observed, respectively. It is important that a thorough head to toe, anterior, posterior, and between skin folds assessment is performed on admission to the progressive care unit to identify any preexisting skin issues that need to be immediately addressed as well as to establish a baseline skin assessment.

Inspect the skin for overall integrity, color, temperature, and turgor. Note the presence of rashes, striae, discoloration, scars, or lesions. For any abrasions, lesions, pressure ulcers, or wounds, note the size, depth, and presence or absence of drainage. Consider use of a skin integrity risk assessment tool to determine immediate interventions that may be needed to prevent further skin integrity breakdown.

The rapid physiologic and psychological changes associated with acute illnesses, coupled with pharmacologic and biological treatments, can profoundly affect behavior. Patients may suffer from illnesses that have psychological responses that are predictable, and, if untreated, may threaten recovery or life. To avoid making assumptions about how a patient feels about his or her care, there is no substitute for asking the patient directly or asking a collateral informant, such as the family or significant other.

Factors that affect communication include culture, developmental stage, physical condition, stress, perception, neurocognitive deficits, emotional state, and language skills. The nature of an acute illness coupled with pharmacologic and airway technologies can interfere with patients’ usual methods of communication. It is essential to determine pre-illness communication abilities as well as methods and styles to ensure optimal communication with the progressive care patient and family. The inability of some progressive care patients to communicate verbally necessitates that progressive care practitioners become expert at assessing nonverbal clues to determine important information from, and needs of, patients. Important assessment data are gained by observation of body gestures, facial expressions, eye movements, involuntary movements, and changes in physiologic parameters, particularly heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Often, these nonverbal behaviors may be more reflective of patients’ actual feelings, particularly if they are denying symptoms and attempting to be the “good patient” by not complaining.

Anxiety is both psychologically and physiologically exhausting. Being in a prolonged state of arousal is hard work and uses adaptive reserves needed for recovery. The progressive care environment can be stressful, full of constant auditory and tactile stimuli, and may contribute to a patient’s anxiety level. The progressive care setting may force isolation from social supports, dependency, loss of control, trust in unknown care providers, helplessness, and an inability to solve problems. Restlessness, distractibility, hyperventilation, and unrealistic demands for attention are warning signs of escalating anxiety.

Medications such as interferon, corticosteroids, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and vasopressors can induce anxiety. Abrupt withdrawal from benzodiazepines, caffeine, nicotine, and narcotics as well as akathisia from phenothiazines may mimic anxiety. Additional etiologic variables associated with anxiety include pain, sleep loss, delirium, hypoxia, ventilator synchronization or weaning, fear of death, loss of control, high-technology equipment, and a dehumanizing setting. Admission to or repeated transfers to the progressive care unit may also induce anxiety.

Individuals cope with an acute illness in different ways and their pre-illness coping style, personality traits, or temperament will assist you in anticipating coping styles in the progressive care setting. Include the patient’s family when assessing previous resources, coping skills, or defense mechanisms that strengthen adaptation or problem-solving resolution. For instance, some patients want to be informed of everything that is happening with them in the progressive care unit. Providing information reduces their anxiety and gives them a sense of control. Other patients prefer to have others receive information about them and make decisions for them. Giving them detailed information only exacerbates their level of anxiety and diminishes their ability to cope. It is most important to understand the meaning assigned to the event by the patient and family and the purpose the coping defense serves. Does the coping resource fit with the event and meet the patient’s and family’s need?

This may also be the time to conduct a brief assessment of the spiritual beliefs and needs of the patient and how those assist them in their coping. Minimally, patients should be asked if they have a faith or spiritual preference and wish to see a chaplain, priest, or other spiritual guide. However, patients should also be asked about spiritual and cultural healing practices that are important to them to determine whether those can possibly be maintained during their progressive care unit stay.

Patients express their coping styles in a variety of ways. Persons who are stoic by personality or culture usually present as the good patient. Assess for behaviors of not wanting to bother the busy staff or not admitting pain because family or others are nearby. Some patients express their anxiety and stress through manipulative behavior. Progressive care nurses must understand that patients’ and families’ impulsivity, deception, low tolerance for frustration, unreliability, superficial charm, splitting among the provider team, and general avoidance of rules or limits are modes of interacting and coping and attempts to feel safe. Still other patients may withdraw and actually request use of sedatives and sleeping medications to blunt the stimuli and stress of the environment.

Fear has an identifiable source and an important role in the ability of the patient to cope. Treatments, procedures, pain, and separation are common objects of fear. The dying process elicits specific fears, such as fear of the unknown, loneliness, loss of body, loss of self-control, suffering, pain, loss of identity, and loss of everyone loved by the patient. The family, as well as the patient, experiences the grieving process, which includes the phases of denial, shock, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

The concept of family is not simple today and extends beyond the nuclear family to any loving, supportive person regardless of social and legal boundaries. Ideally the patient should be asked who they identify as family, who should receive information about patient status, and who should make decisions for the patient if he or she becomes unable to make decisions for self. This may also be an opportune time to ask whether they have an advance directive, a physician order for life sustaining treatment (POLST) on file, or if they have discussed their wishes with any family members or friends. Progressive care practitioners need to be flexible around traditional legal boundaries of next of kin so that communication is extended to, and sought from, surrogate decision makers and whomever the patient designates.

Families can have a positive impact on the patient’s ability to cope with and recover from an acute illness. Each family system is unique and varies by culture, values, religion, previous experience with crisis, socioeconomic status, psychological integrity, role expectations, communication patterns, health beliefs, and ages. It is important to assess the family’s needs and resources to develop interventions that will optimize family impact on the patient and their interactions with the healthcare team. Areas for family needs assessments are outlined in Table 1-5.

The progressive care nurse must take the time to educate the patient (if alert) and family about the specialized progressive care unit environment. This orientation should include a simple explanation of the equipment being used in the care of the patient, visitation policies, the routines of the unit, and how the patient can communicate needs to the unit staff. Additionally, the family should be given the unit telephone number and the names of the nurse manager as well as the nurse caring for the patient in case problems or concerns arise during the progressive care unit stay.

After completing the comprehensive assessment, analyze the information gathered for the need to make referrals to other healthcare providers and resources (Table 1-12). With length of stay and appropriate resource management a continual challenge, it is important to start referrals as soon as possible to maintain continuity of care and avoid worsening decline of status. Assess whether any ancillary service referrals may have already been initiated in the ICU or medical-surgical unit and ensure those services are aware of the transfer in order to avoid any gaps in coverage.

It is important that transition and/or discharge planning starts on arrival of the patient to the progressive care unit. Length of stays continues to decrease for patients in progressive care, creating a challenge for progressive care nurses to assess the appropriate transition location for the progressive care patient adequately. Educational and logistical processes need to be put into place in a timely manner so as to avoid any delays in patient progress and recovery. This necessitates early and active involvement by all appropriate healthcare team members to ensure smooth transitioning.

After the arrival quick check and comprehensive assessments are completed, all subsequent assessments are used to determine trends, evaluate response to therapy, and identify new potential problems or changes from the comprehensive baseline assessment. Ongoing assessments become more focused, and the frequency is driven by the stability of the patient; however, routine periodic assessments are the norm; for example, ongoing assessments can occur every 1 to 2 hours for patients who are exhibiting changes in physiological status to every 2 to 4 hours for stable patients. Additional assessments should be made when any of the following situations occur:

• When caregivers change

• Before and after any major procedural intervention, such as chest tube insertion

• Before and after transport out of the progressive care unit for diagnostic procedures or other events

• Deterioration in physiologic or mental status

• Initiation of any new therapy

As with the arrival quick check, the ongoing assessment section is offered as a generic template that can be used as a basis for all patients (Table 1-13). More in-depth and system-specific assessment parameters are added based on the patient’s diagnosis and pathophysiologic problems.

TABLE 1-13. ONGOING ASSESSMENT TEMPLATE

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Core Curriculum for Progressive Care Nursing. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2010.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Progressive Care Task Force. Progressive care fact sheet. 2009. Available at www.aacn.org/WD/Practice/Docs/ProgressiveCareFactSheet.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2013.

Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

Gorman LM, Sultan DF. Psychosocial Nursing for General Patient Care, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Co; 2008.

Stacy KM. Progressive care units: different but the same. Crit Care Nurs. 2011;31(3):77-83.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Protocols for Practice: Creating a Healing Environment. 2nd ed. Aliso Viejo, CA: AACN; 2007.

American College of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines on admission and discharge for adult intermediate care units. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(3):607-610.

Gephart SM. The art of effective handoffs. What is the evidence? Adv Neonatal Care. 2012;12(1):37-39.

Hilligoss B, Cohen MD. The unappreciated challenges of between-unit handoffs: negotiating and coordinating across boundaries. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(1):15-160.

Maxwell KE, Stuenkel D, Saylor C. Needs of family members of critically ill patients: a comparison of nurse and family perceptions. Heart Lung. 2007;36(5):367-376.

Murphy TH, Labonte P, Klock M, Houser L. Falls prevention for elders in acute care: an evidence-based nursing practice initiative. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31(1):33-39.

Sendelbach S, Guthrie PF, Schoenfelder DP. Acute confusion/delirium. Identification, assessment, treatment, and prevention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(11):11-18.

Staggers N, Blaz JW. Research on nursing handoffs for medical and surgical settings: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(2):247-262.

Tescher AN, Branda ME, OByrne TJ, Naessens JM. All at-risk patients are not created equal. Analysis of Braden pressure ulcer risk scores to identify specific risks. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(3):282-291.

Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Van Zuuren F, Duijnstee M, Grypdonck M. The needs and experiences of family members of adult patients in an intensive care unit: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:501-509.