Neurologic Emergencies and Stabilization

Patrick M. Kochanek, Michael J. Bell

Neurocritical Care Principles

The brain has high metabolic demands, which are further increased during growth and development. Preservation of nutrient supply to the brain is the mainstay of care for children with evolving brain injuries. Intracranial dynamics describes the physics of the interactions of the contents—brain parenchyma, blood (arterial, venous, capillary), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—within the cranium. Normally, brain parenchyma accounts for up to 85% of the contents of the cranial vault, and the remaining portion is divided between CSF and blood. The brain resides in a relatively rigid cranial vault, and cranial compliance decreases with age as the skull ossification centers gradually replace cartilage with bone. The intracranial pressure (ICP) is derived from the volume of its components and the bony compliance. The perfusion pressure of the brain (cerebral perfusion pressure, CPP) is equal to the pressure of blood entering the cranium (mean arterial pressure, MAP) minus the ICP, in most cases.

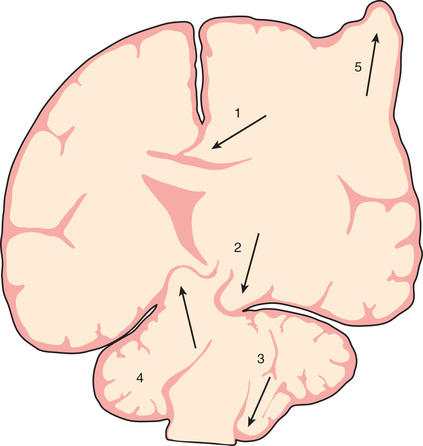

Increases in intracranial volume can result from swelling, masses, or increases in blood and CSF volumes. As these volumes increase, compensatory mechanisms decrease ICP by (1) decreasing CSF volume (CSF is displaced into the spinal canal or absorbed by arachnoid villi), (2) decreasing cerebral blood volume (venous blood return to the thorax is augmented), and/or (3) increasing cranial volume (sutures pathologically expand or bone is remodeled). Once compensatory mechanisms are exhausted (the increase in cranial volume is too large), small increases in volume lead to large increases in ICP, or intracranial hypertension (Fig. 85.1 ). As ICP continues to increase, brain ischemia can occur as CPP falls. Further increases in ICP can ultimately displace the brain downward into the foramen magnum—a process called cerebral herniation, which can become irreversible in minutes and may lead to severe disability or death; Fig. 85.2 notes other sites of brain herniation.

Oxygen and glucose are required by brain cells for normal functioning, and these nutrients must be constantly supplied by cerebral blood flow (CBF). Normally, CBF is constant over a wide range of blood pressures (i.e., blood pressure autoregulation of CBF) via actions mainly within the cerebral arterioles. Cerebral arterioles are maximally dilated at lower blood pressures and maximally constricted at higher pressures so that CBF does not vary during normal fluctuations (Fig. 85.3 ). Above the upper limit of autoregulation, breakthrough dilation occurs, which if severe can produce hypertensive encephalopathy. Acid-base balance of the CSF, often reflected by acute changes in arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO 2 ), body/brain temperature, glucose utilization, blood viscosity, and other vasoactive mediators (i.e., adenosine, nitric oxide), can also affect the cerebral vasculature.

Knowledge of these concepts is instrumental to preventing secondary brain injury. Increases in CSF pH that occur because of inadvertent hyperventilation (which decreases PaCO 2 ) can produce cerebral ischemia. Hyperthermia-mediated increases in cerebral metabolic demands may damage vulnerable brain regions after injury. Hypoglycemia can produce neuronal death when CBF fails to compensate. Prolonged seizures can lead to permanent injuries if hypoxemia occurs from loss of airway control.

Attention to detail and constant reassessment are paramount in managing children with critical neurologic insults. Among the most valuable tools for serial, objective assessment of neurologic condition is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see Chapter 81 , Table 81.3 ). Originally developed for use in comatose adults, the GCS is also valuable in pediatrics. Modifications to the GCS have been made for nonverbal children and are available for infants and toddlers. Serial assessments of the GCS score along with a focused neurologic examination are invaluable to detection of injuries before permanent damage occurs in the vulnerable brain. The full outline of unresponsiveness (FOUR) score is a modification of the GCS, with eye and motor response, but eliminates the verbal response and adds 2 functional assessments of the brainstem (pupil, corneal, and cough reflexes) and respiratory patterns (Table 85.1 ).

Table 85.1

| POINTS | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| GLASGOW COMA SCALE (GCS) SCORE | |

| Eye Opening | |

| 1 | Does not open eyes |

| 2 | Opens eyes in response to noxious stimuli |

| 3 | Opens eyes in response to voice |

| 4 | Opens eyes spontaneously |

| Verbal Output | |

| 1 | Makes no sounds |

| 2 | Makes incomprehensible sounds |

| 3 | Utters inappropriate words |

| 4 | Confused and disoriented |

| 5 | Speaks normally and oriented |

| Motor Response (Best) | |

| 1 | Makes no movements |

| 2 | Extension to painful stimuli |

| 3 | Abnormal flexion to painful stimuli |

| 4 | Flexion/withdrawal to painful stimuli |

| 5 | Localized to painful stimuli |

| 6 | Obeys commands |

| FULL OUTLINE OF UNRESPONSIVENESS (FOUR) SCORE | |

| Eye Response | |

| 4 | Eyelids open or opened, tracking, or blinking to command |

| 3 | Eyelids open but not tracking |

| 2 | Eyelids closed but open to loud voice |

| 1 | Eyelids closed but open to pain |

| 0 | Eyelids remain closed with pain |

| Motor Response | |

| 4 | Thumbs-up, fist, or “peace” sign |

| 3 | Localizing to pain |

| 2 | Flexion response to pain |

| 1 | Extension response to pain |

| 0 | No response to pain or generalized myoclonus status |

| Brainstem Reflexes | |

| 4 | Pupil and corneal reflexes present |

| 3 | One pupil wide and fixed |

| 2 | Pupil or corneal reflexes absent |

| 1 | Pupil and corneal reflexes absent |

| 0 | Absent pupil, corneal, and cough reflex |

| Respiration | |

| 4 | Not intubated, regular breathing pattern |

| 3 | Not intubated, Cheyne-Stokes breathing pattern |

| 2 | Not intubated, irregular breathing |

| 1 | Breathes above ventilatory rate |

| 0 | Breathes at ventilator rate or apnea |

Adapted from Edlow JA, Rabinstein A, Traub SJ, Wijdicks EFM: Diagnosis of reversible causes of coma, Lancet 384:2064-2076, 2014.

The most studied monitoring device in clinical practice is the ICP monitor . Monitoring is accomplished by inserting a catheter-transducer either into the cerebral ventricle or into brain parenchyma (i.e., externalized ventricular drain and parenchymal transducer, respectively). ICP-directed therapies are standard of care in traumatic brain injury (TBI) and are used in other conditions, such as intracranial hemorrhage, some cases of encephalopathy, meningitis, and encephalitis. Other devices being used include catheters that measure brain tissue oxygen concentration, external probes that noninvasively assess brain oxygenation by absorbance of near-infrared light (i.e., near-infrared spectroscopy), monitors of brain electrical activity (continuous electroencephalography [EEG] or somatosensory, visual, or auditory evoked potentials), and CBF monitors (transcranial Doppler, xenon CT, perfusion MRI, or tissue probes). In the severe TBI guidelines, brain tissue oxygen concentration monitoring received level III support and thus may be considered.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Etiology and Epidemiology

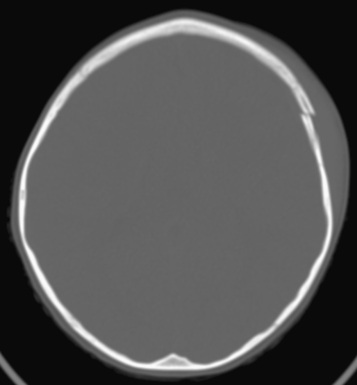

Mechanisms of TBI include motor vehicle crashes, falls, assaults, and abusive head trauma. Most TBIs in children are from closed-head injuries (Fig. 85.4 ). TBI is an important pediatric public health problem, with approximately 37,000 cases resulting in the death of >7,000 children annually in the United States.

Pathology

Epidural, subdural, and parenchymal intracranial hemorrhages can result. Injury to gray or white matter is also commonly seen and includes focal cerebral contusions, diffuse cerebral swelling, axonal injury, and injury to the cerebellum or brainstem. Patients with severe TBI often have multiple findings; diffuse and potentially delayed cerebral swelling is common.

Pathogenesis

TBI results in primary and secondary injury. Primary injury from the impact produces irreversible tissue disruption. In contrast, 2 types of secondary injury are targets of neurointensive care. First, some of the ultimate damage seen in the injured brain evolves over hours or days, and the underlying mechanisms involved (e.g., edema, apoptosis, secondary axotomy) are therapeutic targets. Second, the injured brain is vulnerable to additional insults because injury disrupts normal autoregulatory defense mechanisms; disruption of autoregulation of CBF can lead to ischemia from hypotension that would otherwise be tolerated by the uninjured brain.

Clinical Manifestations

The hallmark of severe TBI is coma (GCS score 3-8 ). Often, coma is seen immediately after the injury and is sustained. In some cases, such as with an epidural hematoma, a child may be alert on presentation but may deteriorate after a period of hours. A similar picture can be seen in children with diffuse swelling, in whom a “talk-and-die” scenario has been described. Clinicians should also not be lulled into underappreciating the potential for deterioration of a child with moderate TBI (GCS score 9-12 ) with a significant contusion, because progressive swelling can potentially lead to devastating complications. In the comatose child with severe TBI, the second key clinical manifestation is the development of intracranial hypertension . The development of increased ICP with impending herniation may be heralded by new-onset or worsening headache, depressed level of consciousness, vital sign changes (hypertension, bradycardia, irregular respirations), and signs of 6th (lateral rectus palsy) or 3rd (anisocoria [dilated pupil], ptosis, down-and-out position of globe as a result of rectus muscle palsies) cranial nerve compression. Increased ICP is managed with continuous ICP monitoring, as well as monitoring for clinical signs of increased ICP or impending herniation. The development of brain swelling is progressive. Significantly raised ICP (>20 mm Hg) can occur early after severe TBI, but peak ICP generally is seen at 48-72 hr. Need for ICP-directed therapy may persist for longer than a week. A few children have coma without increased ICP, resulting from axonal injury or brainstem injury. In addition to head trauma, it is critical to identify potential cervical spine injury (see Chapter 83 ).

Laboratory Findings

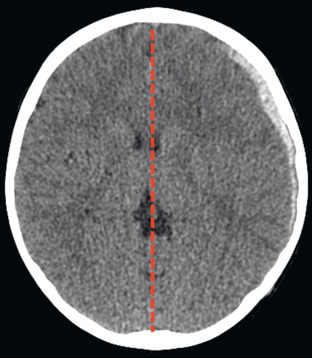

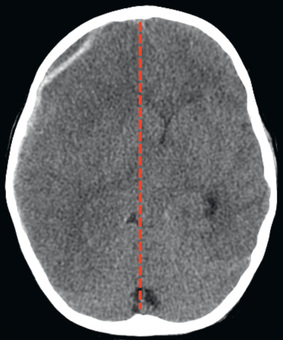

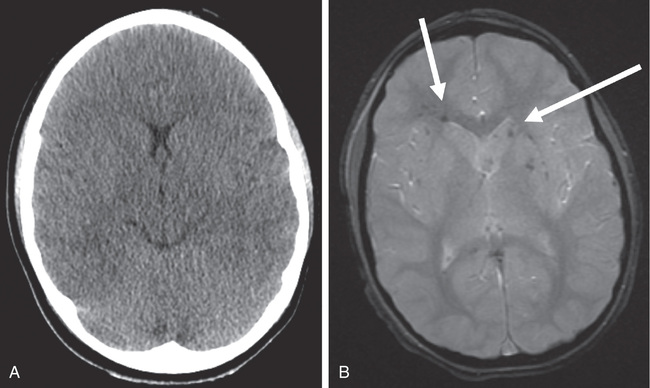

Cranial CT should be obtained immediately after resuscitation and cardiopulmonary stabilization (Figs. 85.5 to 85.11 ). In some cases, MRI can be diagnostic (Fig. 85.12 ). Generally, other laboratory findings are normal in isolated TBI, although occasionally coagulopathy or the development of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion or, rarely, cerebral salt wasting (CSW) is seen. In the setting of TBI with polytrauma, other injuries can result in laboratory and radiographic abnormalities, and a full trauma survey is important in all patients with severe TBI (see Chapter 82 ).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

In severe TBI the diagnosis is generally obvious from the history and clinical presentation. Occasionally, TBI severity can be overestimated because of concurrent alcohol or drug intoxication. The diagnosis of TBI can be problematic in cases of abusive head trauma or following an anoxic event such as drowning or smoke inhalation.

Treatment

Infants and children with severe or moderate TBI (GCS score 3-8 or 9-12, respectively) receive intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring. Evidence-based guidelines for management of severe TBI have been published (Fig. 85.13 ). This approach to ICP-directed therapy is also reasonable for other conditions in which ICP is monitored. Care involves a multidisciplinary team comprising pediatric caregivers from neurologic surgery, critical care medicine, surgery, and rehabilitation and is directed at preventing secondary insults and managing increased ICP. Initial stabilization of infants and children with severe TBI includes rapid sequence tracheal intubation with spine precautions along with maintenance of normal extracerebral hemodynamics, including blood gas values (PaO 2 , PaCO 2 ), MAP, and temperature. Intravenous (IV) fluid boluses may be required to treat hypotension. Euvolemia is the target, and hypotonic fluids must be rigorously avoided; normal saline is the fluid of choice . Vasopressors may be needed as guided by monitoring of central venous pressure, with avoidance of both fluid overload and exacerbation of brain edema. A trauma survey should be performed. Once stabilized, the patient should be taken for CT scanning to rule out the need for emergency neurosurgical intervention. If surgery is not required, an ICP monitor should be inserted to guide the treatment of intracranial hypertension.

During stabilization or at any time during the treatment course, patients can present with signs and symptoms of cerebral herniation (pupillary dilation, systemic hypertension, bradycardia, extensor posturing). Because herniation and its devastating consequences can sometimes be reversed if promptly addressed, it should be treated as a medical emergency , with use of hyperventilation, with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 1.0, and intubating doses of either thiopental or pentobarbital and either mannitol (0.25-1.0 g/kg IV) or hypertonic saline (3% solution, 5-10 mL/kg IV).

Intracranial pressure should be maintained at <20 mm Hg . Age-dependent cerebral perfusion pressure targets are approximately 50 mm Hg for children 2-6 yr old; 55 mm Hg for those 7-10 yr old; and 65 mm Hg for those 11-16 yr old. First-tier therapy includes elevation of the head of the bed, ensuring midline positioning of the head, controlled mechanical ventilation, and analgesia and sedation (i.e., narcotics and benzodiazepines). If neuromuscular blockade is needed, it may be desirable to monitor EEG continuously because status epilepticus can occur; this complication will not be recognized in a paralyzed patient and is associated with increased ICP and unfavorable outcome. If a ventricular rather than parenchymal catheter is used to monitor ICP, therapeutic CSF drainage is available and can be provided either continuously (often targeting an ICP >5 mm Hg) or intermittently in response to ICP spikes, generally >20 mm Hg. Other first-tier therapies include the osmolar agents hypertonic saline (often given as a continuous infusion of 3% saline at 0.1-1.0 mL/kg/hr) and mannitol (0.25-1.0 g/kg IV over 20 min), given in response to ICP spikes >20 mm Hg or with a fixed (every 4-6 hr) dosing interval. Use of hypertonic saline is more common and has stronger literature support than mannitol, although both are used; these 2 agents can be used concurrently. It is recommended to avoid serum osmolality >320 mOsm/L. A Foley urinary catheter should be placed to monitor urine output.

If increased ICP remains refractory to treatment, careful reassessment of the patient is needed to rule out unrecognized hypercarbia, hypoxemia, fever, hypotension, hypoglycemia, pain, and seizures. Repeat imaging should be considered to rule out a surgical lesion. Guidelines-based second-tier therapies for refractory raised ICP are available, but evidence favoring a given second-tier therapy is limited. In some centers, surgical decompressive craniectomy is used for refractory traumatic intracranial hypertension. Others use a pentobarbital infusion , with a loading dose of 5-10 mg/kg over 30 min followed by 5 mg/kg every hour for 3 doses and then maintenance with an infusion of 1 mg/kg/hr. Careful blood pressure monitoring is required because of the possibility of drug-induced hypotension and the frequent need for support with fluids and pressors. Mild hypothermia (32-34°C [89.6-93.2°F]) in an attempt to control refractory ICP may be induced and maintained by means of surface cooling. Hypothermia for increased ICP after traumatic brain injury remains controversial for pediatric and adult patients. Hyperthermia must be avoided and if present should be treated aggressively. Sedation and neuromuscular blockade are used to prevent shivering, and rewarming should be slow, no faster than 1°C (1.8°F) every 4-6 hr. Hypotension should be prevented during rewarming. Refractory raised ICP can also be treated with hyperventilation (PaCO 2 25-30 mm Hg). Combinations of these second-tier therapies are often required.

Supportive Care

Euvolemia should be maintained, and isotonic fluids are recommended throughout the ICU stay. SIADH and CSW can develop and are important to differentiate, because management of SIADH is fluid restriction and that of CSW is sodium replacement. Severe hyperglycemia (blood glucose level >200 mg/dL) should be avoided and treated. The blood glucose level should be monitored frequently. Early nutrition with enteral feedings is advocated. Corticosteroids should generally not be used unless adrenal insufficiency is documented. Tracheal suctioning can exacerbate raised ICP. Timing of the use of analgesics or sedatives around suctioning events and use of tracheal or IV lidocaine can be helpful. Seizures are common after severe acute TBI. Early posttraumatic seizures (within 1 wk) will complicate management of TBI and are often difficult to treat. Anticonvulsant prophylaxis with fosphenytoin, carbamazepine, or levetiracetam is a common treatment option. Late posttraumatic seizures (≥7 days after TBI) and, if recurrent, late posttraumatic epilepsy are not prevented by prophylactic anticonvulsants, whereas early posttraumatic seizures are prevented by initiating anticonvulsants soon after TBI. Antifibrinolytic agents (tranexamic acid) reduce hemorrhage size, as well as the development of new focal ischemic cerebral lesions, and improve survival in adults with severe TBI.

Prognosis

Mortality rates for children with severe TBI who reach the pediatric ICU range between 10% and 30%. Ability to control ICP is related to patient survival, and the extent of cranial and systemic injuries correlates with quality of life. Motor and cognitive sequelae resulting from severe TBI generally benefit from rehabilitation to minimize long-term disabilities. Recovery from TBI may take months to achieve. Physical therapy, and in some centers methylphenidate or amantadine, helps with motor and behavioral recovery. Pituitary insufficiency may be an uncommon but significant complication of severe TBI.