Atopic Dermatitis (Atopic Eczema)

Donald Y.M. Leung, Scott H. Sicherer

Atopic dermatitis (AD) , or eczema, is the most common chronic relapsing skin disease seen in infancy and childhood. It affects 10–30% of children worldwide and frequently occurs in families with other atopic diseases. Infants with AD are predisposed to development of food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma later in childhood, a process called the atopic march .

Etiology

AD is a complex genetic disorder that results in a defective skin barrier, reduced skin innate immune responses, and polarized adaptive immune responses to environmental allergens and microbes that lead to chronic skin inflammation.

Pathology

Acute AD skin lesions are characterized by spongiosis , or marked intercellular edema, of the epidermis. In AD, dendritic antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the epidermis, such as Langerhans cells, exhibit surface-bound IgE molecules with cell processes that reach into upper epidermis to sense allergens and pathogens. These APCs play an important role in cutaneous responses to type 2 immune responses (see Chapter 166 ). There is marked perivenular T-cell and inflammatory monocyte-macrophage infiltration in acute AD lesions. Chronic, lichenified AD is characterized by a hyperplastic epidermis with hyperkeratosis and minimal spongiosis. There are predominantly IgE-bearing Langerhans cells in the epidermis, and macrophages in the dermal mononuclear cell infiltrate. Mast cell and eosinophil numbers are increased, contributing to skin inflammation.

Pathogenesis

AD is associated with multiple phenotypes and endotypes that have overlapping clinical presentations. Atopic eczema is associated with IgE-mediated sensitization (at onset or during the course of eczema) and occurs in 70–80% of patients with AD. Nonatopic eczema is not associated with IgE-mediated sensitization and is seen in 20–30% of patients with AD. Both forms of AD are associated with eosinophilia. In atopic eczema, circulating T cells expressing the skin homing receptor cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen produce increased levels of T-helper type 2 (Th2) cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, which induce isotype switching to IgE synthesis. Another cytokine, IL-5, plays an important role in eosinophil development and survival. Nonatopic eczema is associated with lower IL-4 and IL-13 but increased IL-17 and IL-23 production than in atopic eczema. Age and race have also been found to affect the immune profile in AD.

Compared with the skin of healthy individuals, both unaffected skin and acute skin lesions of patients with AD have an increased number of cells expressing IL-4 and IL-13. Chronic AD skin lesions, by contrast, have fewer cells that express IL-4 and IL-13, but increased numbers of cells that express IL-5, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-12, and interferon (IFN)-γ than acute AD lesions. Despite increased type 1 and type 17 immune responses in chronic AD, IL-4 and IL-13 as well as other type 2 cytokines (e.g. TSLP, IL-31, IL-33) predominate and reflect increased numbers of Type 2 innate lymphoid cells and Th2 cells. The infiltration of IL-22–expressing T cells correlates with severity of AD, blocks keratinocyte differentiation, and induces epidermal hyperplasia. The importance of IL-4 and IL-13 in driving severe persistent AD has been validated by multiple clinical trials now demonstrating that biologics blocking IL-4 and IL-13 action lead to clinical improvement in moderate to severe AD.

In healthy people the skin acts as a protective barrier against external irritants, moisture loss, and infection. Proper function of the skin depends on adequate moisture and lipid content, functional immune responses, and structural integrity. Severely dry skin is a hallmark of AD. This results from compromise of the epidermal barrier, which leads to excess transepidermal water loss, allergen penetration, and microbial colonization. Filaggrin , a structural protein in the epidermis, and its breakdown products are critical to skin barrier function, including moisturization of the skin. Genetic mutations in the filaggrin gene (FLG) family have been identified in patients with ichthyosis vulgaris (dry skin, palmar hyperlinearity) and in up to 50% of patients with severe AD. FLG mutation is strongly associated with development of food allergy and eczema herpeticum. Nonetheless, up to 60% of carriers of a FLG mutation do not develop atopic diseases. Cytokines found in allergic inflammation, such as IL-4, IL-13, IL-22, IL-25, and tumor necrosis factor, can also reduce filaggrin and other epidermal proteins and lipids. AD patients are at increased risk of bacterial, viral, and fungal infection related to impairment of innate immunity, disturbances in the microbiome, skin epithelial dysfunction, and overexpression of polarized immune pathways, which dampen host antimicrobial responses.

Clinical Manifestations

AD typically begins in infancy. Approximately 50% of patients experience symptoms in the 1st yr of life, and an additional 30% are diagnosed between 1 and 5 yr of age. Intense pruritus , especially at night, and cutaneous reactivity are the cardinal features of AD. Scratching and excoriation cause increased skin inflammation that contributes to the development of more pronounced eczematous skin lesions. Foods (cow's milk, egg, peanut, tree nuts, soy, wheat, fish, shellfish), aeroallergens (pollen, grass, animal dander, dust mites), infection (Staphylococcus aureus , herpes simplex, coxsackievirus, molluscum), reduced humidity, excessive sweating, and irritants (wool, acrylic, soaps, toiletries, fragrances, detergents) can trigger pruritus and scratching.

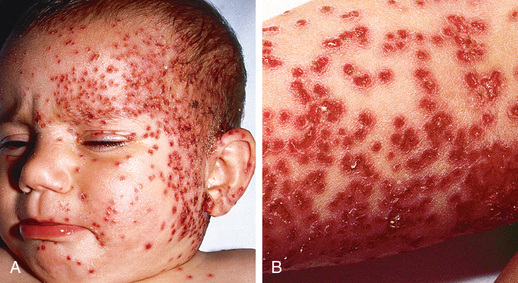

Acute AD skin lesions are intensely pruritic with erythematous papules (Figs. 170.1 and 170.2 ). Subacute dermatitis manifests as erythematous, excoriated, scaling papules. In contrast, chronic AD is characterized by lichenification (Fig. 170.3 ), or thickening of the skin with accentuated surface markings, and fibrotic papules . In chronic AD, all 3 types of skin reactions may coexist in the same individual. Most patients with AD have dry, lackluster skin regardless of their stage of illness. Skin reaction pattern and distribution vary with the patient's age and disease activity. AD is generally more acute in infancy and involves the face, scalp, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. The diaper area is usually spared. Older children and children with chronic AD have lichenification and localization of the rash to the flexural folds of the extremities. AD can go into remission as the patient grows older, however, many children with AD have persistent eczema as an adult (Fig. 170.1C ).

Laboratory Findings

There are no specific laboratory tests to diagnose AD. Many patients have peripheral blood eosinophilia and increased serum IgE levels. Serum IgE measurement or skin-prick testing can identify the allergens (foods, inhalant/microbial allergens) to which patients are sensitized. The diagnosis of clinical allergy to these allergens requires confirmation by history and environmental challenges.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

AD is diagnosed on the basis of 3 major features: pruritus, an eczematous dermatitis that fits into a typical pattern of skin inflammation, and a chronic or chronically relapsing course (Table 170.1 ). Associated features, such as a family history of asthma, hay fever, elevated IgE, and immediate skin test reactivity, reinforce the diagnosis of AD.

Many inflammatory skin diseases, immunodeficiencies, skin malignancies, genetic disorders, infectious diseases, and infestations share symptoms with AD and should be considered and excluded before a diagnosis of AD is established (Tables 170.2 and 170.3 ). Severe combined immunodeficiency (see Chapter 152.1 ) should be considered for infants presenting in the first yr of life with diarrhea, failure to thrive, generalized scaling rash, and recurrent cutaneous and/or systemic infection. Histiocytosis should be excluded in any infant with AD and failure to thrive (see Chapter 534 ). Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, an X-linked recessive disorder associated with thrombocytopenia, immune defects, and recurrent severe bacterial infections, is characterized by a rash almost indistinguishable from that in AD (see Chapter 152.2 ). One of the hyper-IgE syndromes is characterized by markedly elevated serum IgE values, recurrent deep-seated bacterial infections, chronic dermatitis, and refractory dermatophytosis. Many of these patients have disease as a result of autosomal dominant STAT3 mutations. In contrast, some patients with hyper-IgE syndrome present with increased susceptibility to viral infections and an autosomal recessive pattern of disease inheritance. These patients may have a DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8 gene) mutation. This diagnosis should be considered in young children with severe eczema, food allergy, and disseminated skin viral infections.

Table 170.2

Differential Diagnosis of Atopic Dermatitis (AD)

| MAIN AGE GROUP AFFECTED | FREQUENCY* | CHARACTERISTICS AND CLINICAL FEATURES | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTHER TYPES OF DERMATITIS | |||

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Infants | Common | Salmon-red greasy scaly lesions, often on the scalp (cradle cap) and napkin area; generally presents in the 1st 6 wk of life; typically clears within weeks |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Adults | Common | Erythematous patches with yellow, white, or grayish scales in seborrheic areas, particularly the scalp, central face, and anterior chest |

| Nummular dermatitis | Children and adults | Common | Coin-shaped scaly patches, mostly on legs and buttocks; usually no itch |

| Irritant contact dermatitis | Children and adults | Common | Acute to chronic eczematous lesions, mostly confined to the site of exposure; history of locally applied irritants is a risk factor; might coexist with AD |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | Children and adults | Common | Eczematous rash with maximum expression at sites of direct exposure but might spread; history of locally applied irritants is a risk factor; might coexist with AD |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | Adults | Uncommon | One or more localized, circumscribed, lichenified plaques that result from repetitive scratching or rubbing because of intense itch |

| Asteatotic eczema | Adults | Common | Scaly, fissured patches of dermatitis overlying dry skin, most often on lower legs |

| INFECTIOUS SKIN DISEASES | |||

| Dermatophyte infection | Children and adults | Common | One or more demarcated scaly plaques with central clearing and slightly raised reddened edge; variable itch |

| Impetigo | Children | Common | Demarcated erythematous patches with blisters or honey-yellow crusting |

| Scabies | Children | Common † | Itchy superficial burrows and pustules on palms and soles, between fingers, and on genitalia; might produce secondary eczematous changes |

| HIV | Children and adults | Uncommon | Seborrhea-like rash |

| CONGENITAL IMMUNODEFICIENCIES (see Table 170.3 ) | |||

| Keratinization Disorders | |||

| Ichthyosis vulgaris | Infants and adults | Uncommon | Dry skin with fine scaling, particularly on the lower abdomen and extensor areas; perifollicular skin roughening; palmar hyperlinearity; full form (i.e., 2 FLG mutations) is uncommon; often coexists with AD |

| NUTRITIONAL DEFICIENCY–METABOLIC DISORDERS | |||

| Zinc deficiency (acrodermatitis enteropathica) | Children | Uncommon | Erythematous scaly patches and plaques, most often around the mouth and anus; rare congenital form accompanied by diarrhea and alopecia |

| Biotin deficiency (nutritional or biotinidase deficiency) | Infants | Uncommon | Scaly periorofacial dermatitis, alopecia, conjunctivitis, lethargy, hypotonia |

| Pellagra (niacin deficiency) | All ages | Uncommon | Scaly crusted epidermis, desquamation, sun-exposed areas, diarrhea |

| Kwashiorkor | Infants and children | Geographic dependent | Flaky scaly dermatitis, swollen limbs with cracked peeling patches |

| Phenylketonuria | Infants | Uncommon | Eczematous rash, hypopigmentation, blonde hair, developmental delay |

| NEOPLASTIC DISEASE | |||

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | Adults | Uncommon | Erythematous pink-brown macules and plaques with a fine scale; poorly responsive to topical corticosteroids; variable itch (in early stages) |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Infants | Uncommon | Scaly and purpuric dermatosis, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias |

* Common = approximately 1 in 10 to 1 in 100; uncommon = 1 in 100 to 1 in 1000; rare = 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000; very rare = <1 in 10,000.

† Especially in developing countries.

FLG, filaggrin gene.

Table 170.3

Features of Primary Immunodeficiencies Associated With Eczematous Dermatitis

| DISEASE | GENE | INHERITANCE | CLINICAL FEATURES | LAB ABNORMALITIES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD-HIES | STAT3 | AD, less commonly sporadic |

Cold abscesses Recurrent sinopulmonary infections Mucocutaneous candidiasis Coarse facies Minimal trauma fractures Scoliosis Joint hyperextensibility Retained primary teeth Coronary artery tortuosity or dilation Lymphoma |

High IgE (>2000 IU/µL) Eosinophilia |

| DOCK8 deficiency | DOCK8 | AR |

Severe mucocutaneous viral infections Mucocutaneous candidiasis Atopic features (asthma, allergies) Squamous cell carcinoma Lymphoma |

High IgE Eosinophilia With or without decreased IgM |

| PGM3 deficiency | PGM3 | AR |

Neurologic abnormalities Leukocytoclastic vasculitis Atopic features (asthma, allergies) Sinopulmonary infections Mucocutaneous viral infections |

High IgE Eosinophilia |

| WAS | WASP | XLR |

Hepatosplenomegaly Lymphadenopathy Atopic diathesis Autoimmune conditions (especially hemolytic anemia) Lymphoreticular malignancies |

Thrombocytopenia (<80,000/µL) Low mean platelet volume Eosinophilia is common Lymphopenia Low IgM, variable IgG |

| SCID | Variable, depends on type | XLR and AR most common |

Recurrent, severe infections Failure to thrive Persistent diarrhea Recalcitrant oral candidiasis Omenn syndrome: lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, erythroderma |

Lymphopenia common Variable patterns of reduced lymphocyte subsets (T, B, natural killer cells) Omenn syndrome: high lymphocytes, eosinophilia, high IgE |

| IPEX | FOXP3 | XLR |

Severe diarrhea (autoimmune enteropathy) Various autoimmune endocrinopathies (especially diabetes mellitus, thyroiditis) Food allergies |

High IgE Eosinophilia Various autoantibodies |

| Netherton syndrome | SPINK5 | AR |

Hair shaft abnormalities Erythroderma Ichthyosis linearis circumflexa Food allergies Recurrent gastroenteritis Neonatal hypernatremic dehydration Upper and lower respiratory infections |

High IgE Eosinophilia |

AD, Autosomal dominant; AD-HIES, autosomal-dominant hyper-IgE syndrome; AR, autosomal recessive; DOCK8 , dedicator of cytokinesis 8 gene; IPEX, immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome; PGM3, phosphoglucomutase 3; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; WAS, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

From Kliegman RM, Bordini BJ, editors: Undiagnosed and Rare Diseases in Children 64(1):41–42, 2017.

Adolescents who present with an eczematous dermatitis but no history of childhood eczema, respiratory allergy, or atopic family history may have allergic contact dermatitis (see Chapter 674.1 ). A contact allergen may be the problem in any patient whose AD does not respond to appropriate therapy. Sensitizing chemicals, such as parabens and lanolin, can be irritants for patients with AD and are commonly found as vehicles in therapeutic topical agents. Topical glucocorticoid contact allergy has been reported in patients with chronic dermatitis receiving topical corticosteroid therapy. Eczematous dermatitis has also been reported with HIV infection as well as with a variety of infestations such as scabies. Other conditions that can be confused with AD include psoriasis, ichthyosis, and seborrheic dermatitis.

Treatment

The treatment of AD requires a systematic, multifaceted approach that incorporates skin moisturization, topical antiinflammatory therapy, identification and elimination of flare factors (Table 170.4 ), and, if necessary, systemic therapy. Assessment of the severity also helps direct therapy (Table 170.5 ).

Cutaneous Hydration

Because patients with AD have impaired skin barrier function from reduced filaggrin and skin lipid levels, they present with diffuse, abnormally dry skin, or xerosis . Moisturizers are first-line therapy. Lukewarm soaking baths or showers for 15-20 min followed by the application of an occlusive emollient to retain moisture provide symptomatic relief. Hydrophilic ointments of varying degrees of viscosity can be used according to the patient's preference. Occlusive ointments are sometimes not well tolerated because of interference with the function of the eccrine sweat ducts and may induce the development of folliculitis. In these patients, less occlusive agents should be used. Several prescription (classified as a medical device) “therapeutic moisturizers” or “barrier creams” are available, containing components such as ceramides and filaggrin acid metabolites intended to improve skin barrier function. There are minimal data demonstrating their efficacy over standard emollients.

Hydration by baths or wet dressings promotes transepidermal penetration of topical glucocorticoids. Dressings may also serve as effective barriers against persistent scratching, in turn promoting healing of excoriated lesions. Wet dressings are recommended for use on severely affected or chronically involved areas of dermatitis refractory to skin care. It is critical that wet dressing therapy be followed by topical emollient application to avoid potential drying and fissuring from the therapy. Wet dressing therapy can be complicated by maceration and secondary infection and should be closely monitored by a physician.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of antiinflammatory treatment for acute exacerbations of AD. Patients should be carefully instructed on their use of topical glucocorticoids to avoid potential adverse effects. There are 7 classes of topical glucocorticoids, ranked according to their potency, as determined by vasoconstrictor assays (Table 170.6 ). Because of their potential adverse effects, the ultrahigh-potency glucocorticoids should not be used on the face or intertriginous areas and should be used only for very short periods on the trunk and extremities. Mid-potency glucocorticoids can be used for longer periods to treat chronic AD involving the trunk and extremities. Long-term control can be maintained with twice-weekly applications of topical fluticasone or mometasone to areas that have healed but are prone to relapse, once control of AD is achieved after a daily regimen of topical corticosteroids. Compared with creams, ointments have a greater potential to occlude the epidermis, resulting in enhanced systemic absorption.

Adverse effects of topical glucocorticoids can be divided into local adverse effects and systemic adverse effects, the latter resulting from suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Local adverse effects include the development of striae and skin atrophy. Systemic adverse effects are related to the potency of the topical corticosteroid, site of application, occlusiveness of the preparation, percentage of the body surface area covered, and length of use. The potential for adrenal suppression from potent topical corticosteroids is greatest in infants and young children with severe AD requiring intensive therapy.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors

The nonsteroidal topical calcineurin inhibitors are effective in reducing AD skin inflammation. Pimecrolimus cream 1% (Elidel) is indicated for mild to moderate AD. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% and 0.03% (Protopic) is indicated for moderate to severe AD. Both are approved for short-term or intermittent long-term treatment of AD in patients ≥2 yr whose disease is unresponsive to or who are intolerant of other conventional therapies or for whom these therapies are inadvisable because of potential risks. Topical calcineurin inhibitors may be better than topical corticosteroids in the treatment of patients whose AD is poorly responsive to topical steroids, patients with steroid phobia, and those with face and neck dermatitis, in whom ineffective, low-potency topical corticosteroids are typically used because of fears of steroid-induced skin atrophy.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitor

Crisaborole (Eucrisa) is an approved nonsteroidal topical antiinflammatory phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor indicated for the treatment of mild to moderate AD down to age 2 yr. It may be used as an alternative to topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors.

Tar Preparations

Coal tar preparations have antipruritic and antiinflammatory effects on the skin; however, their antiinflammatory effects are usually not as pronounced as those of topical glucocorticoids or calcineurin inhibitors. Therefore, topical tar preparations are not a preferred approach for management of AD. Tar shampoos can be particularly beneficial for scalp dermatitis. Adverse effects associated with tar preparations include skin irritation, folliculitis, and photosensitivity.

Antihistamines

Systemic antihistamines act primarily by blocking the histamine H1 receptors in the dermis, thereby reducing histamine-induced pruritus. Histamine is only one of many mediators that induce pruritus of the skin, so patients may derive minimal benefit from antihistaminic therapy. Because pruritus is usually worse at night, sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine) may offer an advantage with their soporific side effects when used at bedtime. Doxepin hydrochloride has both tricyclic antidepressant and H1 - and H2 -receptor blocking effects. Short-term use of a sedative to allow adequate rest may be appropriate in cases of severe nocturnal pruritus. Studies of newer, nonsedating antihistamines have shown variable effectiveness in controlling pruritus in AD, although they may be useful in the small subset of patients with AD and concomitant urticaria. For children, melatonin may be effective in promoting sleep because production is deficient in AD.

Systemic Corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids are rarely indicated in the treatment of chronic AD. The dramatic clinical improvement that may occur with systemic corticosteroids is frequently associated with a severe rebound flare of AD after therapy discontinuation. Short courses of oral corticosteroids may be appropriate for an acute exacerbation of AD while other treatment measures are being instituted in parallel. If a short course of oral corticosteroids is given, as during an asthma exacerbation, it is important to taper the dosage and begin intensified skin care, particularly with topical corticosteroids, and frequent bathing, followed by application of emollients or proactive topical corticosteroids, to prevent rebound flaring of AD.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is a potent immunosuppressive drug that acts primarily on T cells by suppressing cytokine gene transcription and has been shown to be effective in the control of severe AD. Cyclosporin forms a complex with an intracellular protein, cyclophilin, and this complex in turn inhibits calcineurin, a phosphatase required for activation of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells), a transcription factor necessary for cytokine gene transcription. Cyclosporine (5 mg/kg/day) for short-term and long-term (1 yr) use has been beneficial for children with severe, refractory AD. Possible adverse effects include renal impairment and hypertension.

Dupilumab

A monoclonal antibody that binds to the IL-4 receptor α subunit, dupilumab (Dupixent) inhibits the signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, cytokines associated with AD. In adults with moderate to severe AD not controlled by standard topical therapy, dupilumab reduces pruritus and improves skin clearing.

Antimetabolites

Mycophenolate mofetil is a purine biosynthesis inhibitor used as an immunosuppressant in organ transplantation that has been used for treatment of refractory AD. Aside from immunosuppression, herpes simplex retinitis and dose-related bone marrow suppression have been reported with its use. Of note, not all patients benefit from treatment. Therefore, mycophenolate mofetil should be discontinued if the disease does not respond within 4-8 wk.

Methotrexate is an antimetabolite with potent inhibitory effects on inflammatory cytokine synthesis and cell chemotaxis. Methotrexate has been used for patients with recalcitrant AD. In AD, dosing is more frequent than the weekly dosing used for psoriasis.

Azathioprine is a purine analog with antiinflammatory and antiproliferative effects that has been used for severe AD. Myelosuppression is a significant adverse effect, and thiopurine methyltransferase levels may identify individuals at risk.

Before any of these drugs is used, patients should be referred to an AD specialist who is familiar with treatment of severe AD to weigh relative benefits of alternative therapies.

Phototherapy

Natural sunlight is often beneficial to patients with AD as long as sunburn and excessive sweating are avoided. Many phototherapy modalities are effective for AD, including ultraviolet A-1, ultraviolet B, narrow-band ultraviolet B, and psoralen plus ultraviolet A. Phototherapy is generally reserved for patients in whom standard treatments fail. Maintenance treatments are usually required for phototherapy to be effective. Short-term adverse effects with phototherapy include erythema, skin pain, pruritus, and pigmentation. Long-term adverse effects include predisposition to cutaneous malignancies.

Unproven Therapies

Other therapies may be considered in patients with refractory AD.

Interferon-γ

IFN-γ is known to suppress Th2-cell function. Several studies, including a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and several open trials, have demonstrated that treatment with recombinant human IFN-γ results in clinical improvement of AD. Reduction in clinical severity of AD correlated with the ability of IFN-γ to decrease total circulating eosinophil counts. Influenza-like symptoms are common side effects during the treatment course.

Omalizumab

Treatment of patients who have severe AD and elevated serum IgE values with monoclonal anti-IgE may be considered in those with allergen-induced flares of AD. However, there have been no published double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of omalizumab's use. Most reports have been case studies and show inconsistent responses to anti-IgE.

Allergen Immunotherapy

In contrast to its acceptance for treatment of allergic rhinitis and extrinsic asthma, immunotherapy with aeroallergens in the treatment of AD is controversial. There are reports of both disease exacerbation and improvement. Studies suggest that specific immunotherapy in patients with AD sensitized to dust mite allergen showed improvement in severity of skin disease, as well as reduction in topical corticosteroid use.

Probiotics

Perinatal administration of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG has been shown to reduce the incidence of AD in at-risk children during the 1st 2 yr of life. The treatment response has been found to be more pronounced in patients with positive skin-prick test results and elevated IgE values. Other studies have not demonstrated a benefit.

Chinese Herbal Medications

Several placebo-controlled clinical trials have suggested that patients with severe AD may benefit from treatment with traditional Chinese herbal therapy. The patients had significantly reduced skin disease and decreased pruritus. The beneficial response of Chinese herbal therapy is often temporary, and effectiveness may wear off despite continued treatment. The possibility of hepatic toxicity, cardiac side effects, or idiosyncratic reactions remains a concern. The specific ingredients of the herbs also remain to be elucidated, and some preparations have been found to be contaminated with corticosteroids. At present, Chinese herbal therapy for AD is considered investigational.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D deficiency often accompanies severe AD. Vitamin D enhances skin barrier function, reduces corticosteroid requirements to control inflammation, and augments skin antimicrobial function. Several small clinical studies suggest vitamin D can enhance antimicrobial peptide expression in the skin and reduce severity of skin disease, especially in patients with low baseline vitamin D, as during winter, when exacerbation of AD often occurs. Patients with AD might benefit from supplementation with vitamin D, particularly if they have a documented low level or low vitamin D intake.

Avoiding Triggers

It is essential to identify and eliminate triggering factors for AD, both during the period of acute symptoms and on a long-term basis to prevent recurrences (see Table 170.4 ).

Irritants

Patients with AD have a low threshold response to irritants that trigger their itch-scratch cycle. Soaps or detergents, chemicals, smoke, abrasive clothing, and exposure to extremes of temperature and humidity are common triggers. Patients with AD should use soaps with minimal defatting properties and a neutral pH. New clothing should be laundered before wearing to decrease levels of formaldehyde and other chemicals. Residual laundry detergent in clothing may trigger the itch-scratch cycle; using a liquid rather than powder detergent and adding a 2nd rinse cycle facilitates removal of the detergent.

Every attempt should be made to allow children with AD to be as normally active as possible. A sport such as swimming may be better tolerated than others that involve intense perspiration, physical contact, or heavy clothing and equipment. Rinsing off chlorine immediately and lubricating the skin after swimming are important. Although ultraviolet light may be beneficial to some patients with AD, high–sun protection factor (SPF) sunscreens should be used to avoid sunburn.

Foods

Food allergy is comorbid in approximately 40% of infants and young children with moderate to severe AD (see Chapter 176 ). Undiagnosed food allergies in patients with AD may induce eczematous dermatitis in some patients and urticarial reactions, wheezing, or nasal congestion in others. Increased severity of AD symptoms and younger age correlate directly with the presence of food allergy. Removal of food allergens from the diet leads to significant clinical improvement but requires much education, because most common allergens (egg, milk, peanut, wheat, soy) contaminate many foods and are difficult to avoid.

Potential allergens can be identified by a careful history and performing selective skin-prick tests or in vitro blood testing for allergen-specific IgE. Negative skin and blood test results for allergen-specific IgE have a high predictive value for excluding suspected allergens. Positive results of skin or blood tests using foods often do not correlate with clinical symptoms and should be confirmed with controlled food challenges and elimination diets. Extensive elimination diets, which can be nutritionally deficient, are rarely required. Even with multiple positive skin test results, the majority of patients react to fewer than 3 foods under controlled challenge conditions.

Aeroallergens

In older children, AD flares can occur after intranasal or epicutaneous exposure to aeroallergens such as fungi, animal dander, grass, and ragweed pollen. Avoiding aeroallergens, particularly dust mites, can result in clinical improvement of AD. Avoidance measures for dust mite–allergic patients include using dust mite–proof encasings on pillows, mattresses, and box springs; washing bedding in hot water weekly; removing bedroom carpeting; and decreasing indoor humidity levels with air conditioning.

Infections

Patients with AD have increased susceptibility to bacterial, viral, and fungal skin infections. Antistaphylococcal antibiotics are very helpful for treating patients who are heavily colonized or infected with Staphylococcus aureus.

Erythromycin and azithromycin are usually beneficial for patients who are not colonized with a resistant S. aureus

strain; a first-generation cephalosporin (cephalexin) is recommended for macrolide-resistant S. aureus

. Topical mupirocin is useful in the treatment of localized impetiginous lesions, with systemic clindamycin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole needed for methicillin-resistant S. aureus

(MRSA). Cytokine-mediated skin inflammation contributes to skin colonization with S. aureus

. This finding supports the importance of combining effective antiinflammatory therapy with antibiotics for treating moderate to severe AD to avoid the need for repeated courses of antibiotics, which can lead to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains of S. aureus.

Dilute bleach baths ( cup of bleach in 40 gallons of water) twice weekly may be also considered to reduce S. aureus

colonization. In one randomized trial, the group who received the bleach baths plus intranasal mupirocin (5 days/mo) had significantly decreased severity of AD at 1 and 3 mo compared with placebo. Patients rinse off after the soaking. Bleach baths may not only reduce S. aureus

abundance on the skin but also have antiinflammatory effects.

cup of bleach in 40 gallons of water) twice weekly may be also considered to reduce S. aureus

colonization. In one randomized trial, the group who received the bleach baths plus intranasal mupirocin (5 days/mo) had significantly decreased severity of AD at 1 and 3 mo compared with placebo. Patients rinse off after the soaking. Bleach baths may not only reduce S. aureus

abundance on the skin but also have antiinflammatory effects.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can provoke recurrent dermatitis and may be misdiagnosed as S. aureus infection (Fig. 170.4 ). The presence of punched-out erosions, vesicles, and infected skin lesions that fail to respond to oral antibiotics suggests HSV infection, which can be diagnosed by a Giemsa-stained Tzanck smear of cells scraped from the vesicle base or by viral polymerase chain reaction or culture. Topical corticosteroids should be temporarily discontinued if HSV infection is suspected. Reports of life-threatening dissemination of HSV infections in patients with AD who have widespread disease mandate antiviral treatment. Persons with AD are also susceptible to eczema vaccinatum , which is similar in appearance to eczema herpeticum and historically follows smallpox (vaccinia virus) vaccination.

Cutaneous warts, coxsackievirus, and molluscum contagiosum are additional viral infections affecting children with AD.

Dermatophyte infections can also contribute to exacerbation of AD. Patients with AD have been found to have a greater susceptibility to Trichophyton rubrum fungal infections than nonatopic controls. There has been particular interest in the role of Malassezia furfur (formerly known as Pityrosporum ovale ) in AD because it is a lipophilic yeast commonly present in the seborrheic areas of the skin. IgE antibodies against M. furfur have been found in patients with head and neck dermatitis. A reduction of AD severity has been observed in these patients after treatment with antifungal agents.

Complications

Exfoliative dermatitis may develop in patients with extensive skin involvement. It is associated with generalized redness, scaling, weeping, crusting, systemic toxicity, lymphadenopathy, and fever and is usually caused by superinfection (e.g., with toxin-producing S. aureus or HSV infection) or inappropriate therapy. In some cases the withdrawal of systemic glucocorticoids used to control severe AD precipitates exfoliative erythroderma.

Eyelid dermatitis and chronic blepharitis may result in visual impairment from corneal scarring. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis is usually bilateral and can have disabling symptoms that include itching, burning, tearing, and copious mucoid discharge. Vernal conjunctivitis is associated with papillary hypertrophy or cobblestoning of the upper eyelid conjunctiva. It typically occurs in younger patients and has a marked seasonal incidence with spring exacerbations. Keratoconus is a conical deformity of the cornea believed to result from chronic rubbing of the eyes in patients with AD. Cataracts may be a primary manifestation of AD or from extensive use of systemic and topical glucocorticoids, particularly around the eyes.

Prognosis

AD generally tends to be more severe and persistent in young children, particularly if they have null mutations in their filaggrin genes. Periods of remission occur more frequently as patients grow older. Spontaneous resolution of AD has been reported to occur after age 5 yr in 40–60% of patients affected during infancy, particularly for mild disease. Earlier studies suggested that approximately 84% of children outgrow their AD by adolescence; however, later studies reported that AD resolves in approximately 20% of children monitored from infancy until adolescence and becomes less severe in 65%. Of those adolescents treated for mild dermatitis, >50% may experience a relapse of disease as adults, which frequently manifests as hand dermatitis, especially if daily activities require repeated hand wetting. Predictive factors of a poor prognosis for AD include widespread AD in childhood, FLG null mutations, concomitant allergic rhinitis and asthma, family history of AD in parents or siblings, early age at onset of AD, being an only child, and very high serum IgE levels.

Prevention

Breastfeeding may be beneficial. Probiotics and prebiotics may also reduce the incidence or severity of AD, but this approach is unproven. If an infant with AD is diagnosed with food allergy, the breastfeeding mother may need to eliminate the implicated food allergen from her diet. For infants with severe eczema, introduction of infant-safe forms of peanut as early as 4-6 mo, after other solids are tolerated, is recommended after consultation with the child's pediatrician and/or allergist for allergy testing. This approach may prevent peanut allergy (see Chapter 176 ). Identification and elimination of triggering factors are the mainstay for prevention of flares as well as for the long-term treatment of AD.

Emollient therapy applied to the whole body for the 1st few mo of life may enhance the cutaneous barrier and reduce the risk of eczema.