Pulmonary Abscess

Oren J. Lakser

Lung infection that destroys the lung parenchyma, resulting in cavitations and central necrosis, can result in localized areas composed of thick-walled purulent material, called lung abscesses. Primary lung abscesses occur in previously healthy patients with no underlying medical disorders and are usually solitary. Secondary lung abscesses occur in patients with underlying or predisposing conditions and may be multiple. Lung abscesses are much less common in children (estimated at 0.7 per 100,000 admissions per year) than in adults.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

A number of conditions predispose children to the development of pulmonary abscesses, including aspiration, pneumonia, cystic fibrosis (see Chapter 432 ), gastroesophageal reflux (see Chapter 349 ), tracheoesophageal fistula (see Chapter 345 ), immunodeficiencies, postoperative complications of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, seizures, a variety of neurologic diseases, and other conditions associated with impaired mucociliary defense. In children, aspiration of infected materials or a foreign body is the predominant source of the organisms causing abscesses. Initially, pneumonitis impairs drainage of fluid or the aspirated material. Inflammatory vascular obstruction occurs, leading to tissue necrosis, liquefaction, and abscess formation. Abscess can also occur as a result of pneumonia and hematogenous seeding from another site.

If the aspiration event occurred while the child was recumbent, the right and left upper lobes and apical segment of the right lower lobes are the dependent areas most likely to be affected. In a child who was upright, the posterior segments of the upper lobes were dependent and therefore are most likely to be affected. Primary abscesses are found most often on the right side, whereas secondary lung abscesses, particularly in immunocompromised patients, have a predilection for the left side.

Both anaerobic and aerobic organisms can cause lung abscesses. Common anaerobic bacteria that can cause a pulmonary abscess include Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp., and Peptostreptococcus spp. Abscesses can be caused by aerobic organisms such as Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and very rarely Mycoplasma pneumoniae . Aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be part of the workup for all patients with lung abscess. Occasionally, concomitant viral-bacterial infection can be detected. Fungi can also cause lung abscesses, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Clinical Manifestations

The most common symptoms of pulmonary abscess in the pediatric population are fever, cough, and emesis. Other common symptoms include tachypnea, dyspnea, chest pain, sputum production, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Physical examination typically reveals tachypnea, dyspnea, retractions with accessory muscle use, decreased breath sounds, and dullness to percussion in the affected area. Crackles and occasionally a prolonged expiratory phase may be heard on lung examination.

Diagnosis

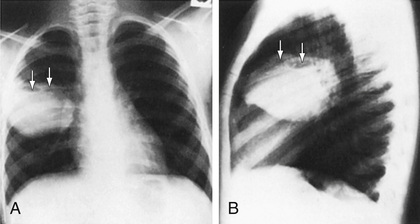

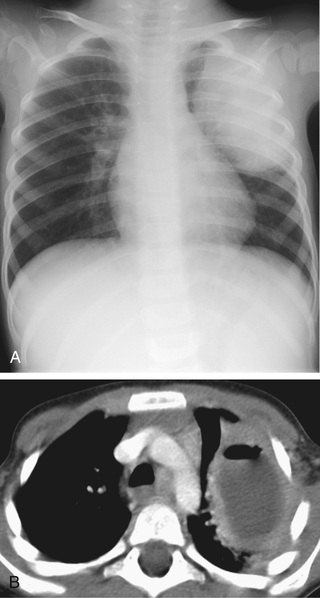

Diagnosis is most commonly made on the basis of chest radiography. Classically, the chest radiograph shows a parenchymal inflammation with a cavity containing an air-fluid level (Fig. 431.1 ). A chest CT scan can provide better anatomic definition of an abscess, including location and size (Fig. 431.2 ).

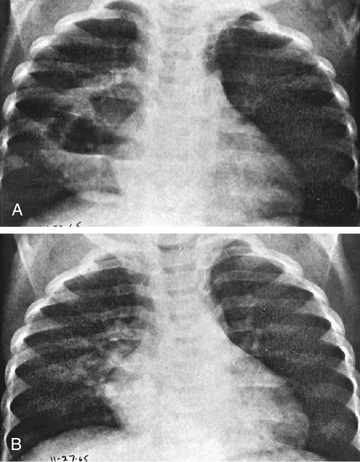

An abscess is usually a thick-walled lesion with a low-density center progressing to an air-fluid level. Abscesses should be distinguished from pneumatoceles, which often complicate severe bacterial pneumonias and are characterized by thin- and smooth-walled, localized air collections with or without air-fluid level (Fig. 431.3 ). Pneumatoceles often resolve spontaneously with the treatment of the specific cause of the pneumonia.

The determination of the etiologic bacteria in a lung abscess can be very helpful in guiding antibiotic choice. Although Gram stain of sputum can provide an early clue as to the class of bacteria involved, sputum cultures typically yield mixed bacteria and therefore are not always reliable. Attempts to avoid contamination from oral flora include direct lung puncture, percutaneous (aided by CT guidance) or transtracheal aspiration, and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens obtained bronchoscopically. Bronchoscopic aspiration should be avoided because it can be complicated by massive intrabronchial aspiration, and great care should therefore be taken during the procedure. To avoid invasive procedures in previously normal hosts, empiric therapy can be initiated in the absence of culturable material.

Treatment

Conservative management is recommended for pulmonary abscess. Most experts advocate a 2- to 3-wk course of parenteral antibiotics for uncomplicated cases, followed by a course of oral antibiotics to complete a total of 4-6 wk. Antibiotic choice should be guided by results of Gram stain and culture but initially should include agents with aerobic and anaerobic coverage. Treatment regimens should include a penicillinase-resistant agent active against S. aureus and anaerobic coverage, typically with clindamycin or ticarcillin/clavulanic acid. If gram-negative bacteria are suspected or isolated, an aminoglycoside should be added. Early CT-guided percutaneous aspiration or drainage has been advocated because it can hasten the recovery and shorten the course of parenteral antibiotic therapy needed.

For severely ill patients, patients with larger abscess, or those whose status fails to improve after 7-10 days of appropriate antimicrobial therapy, surgical intervention should be considered. Minimally invasive percutaneous aspiration techniques, often with CT guidance, are the initial and, often, only intervention required. Thorascopic drainage has also been successfully used with minimal complications. In rare complicated cases, thoracotomy with surgical drainage or lobectomy and/or decortication may be necessary. Abscess drainage is reportedly required in ~20% of cases of pulmonary abscess in children.

Prognosis

Overall, prognosis for children with primary pulmonary abscesses is excellent. The presence of aerobic organisms may be a negative prognostic indicator, particularly in those with secondary lung abscesses. Most children become asymptomatic within 7-10 days, although the fever can persist for as long as 3 wk. Radiologic abnormalities usually resolve in 1-3 mo but can persist for years.