Diseases of the Myocardium

John J. Parent, Stephanie M. Ware

The extremely heterogeneous heart muscle diseases associated with structural remodeling and abnormalities of cardiac function (cardiomyopathy ) are important causes of morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population. Several classification schemes have been formulated in an effort to provide logical, useful, and scientifically based etiologies for the cardiomyopathies. Insight into the molecular genetic basis of cardiomyopathies has increased exponentially, and etiologic classification schemes continue to evolve (Table 466.1 ).

Table 466.1

Classification of the Cardiomyopathies by Phenome and Genome

| TYPE | PHENOTYPE | GENOME | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Physiology | Pathology | Systemic Conditions, Clinical Features, Risk Factors | Nonsyndromic, Usually Single Gene | Syndromic | |

| Dilated (DCM) | Dilation of LV and RV with minimal or no wall thickening | Reduced contractility is the primary defect; variable degree of diastolic dysfunction | Myocyte hypertrophy; scattered fibrosis | Hypertension, alcohol, thyrotoxicosis, myxedema, persistent tachycardia, toxins (e.g., chemotherapy, especially anthracyclines), radiation | Diverse gene ontology with >30 genes implicated | Diverse array of associated conditions, especially muscular dystrophies: Emery-Dreifuss, limb-girdle, Duchenne/Becker; Laing distal myopathy; Barth syndrome; Kearns-Sayre syndrome; others |

| Restrictive (RCM) | Usually normal chamber sizes; minimal wall thickening | Contractility normal or near-normal with a marked increase in end-diastolic filling pressure | Specific to type, diagnosis: amyloid, iron, glycogen storage disease, others | Endomyocardial fibrosis, amyloid, sarcoid, scleroderma, Churg-Strauss syndrome, cystinosis, lymphoma, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, hypereosinophilic syndrome, carcinoid | If not associated with systemic genetic disease, genetic cause usually from sarcomeric gene mutations | Gaucher disease, hemochromatosis, Fabry disease, familial amyloidosis; mucopolysaccharidoses, Noonan syndrome |

| Hypertrophic (HCM) | Usually normal or reduced internal chamber dimension; wall thickening pronounced, especially septal hypertrophy | Systolic function increased or normal | Myocyte hypertrophy, classically with disarray | Severe hypertension can confound clinical, morphologic diagnosis | Mutations of genes encoding sarcomeric proteins | Noonan syndrome, LEOPARD syndrome, Danon syndrome, Fabry disease, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, Friedreich ataxia, MERRF, MELAS |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | Scattered fibrofatty infiltration, classically of RV but also of LV; dilation of RV or LV, or both, is common but not universal | Ventricular arrhythmias (VT, VF) early or late, reduced contractility with progressive disease; can mimic DCM | Islands of fatty replacement; fibrosis | Palmoplantar keratoderma, wooly hair in Naxos syndrome | Mutations of genes encoding proteins of desmosome | Naxos syndrome |

| Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) | Ratio of noncompacted to compacted myocardium increased with normal LV or RV or any other phenotype | Normal to reduced systolic function | Myocardium normal and ranging to findings consistent with other coexisting cardiomyopathies | Phenotype observed in setting of other types of cardiomyopathy | Various cardiomyopathy genes associated, but uncertain whether genetic cause or developmental defect during organogenesis | |

| Infiltrative | Usually thickened walls; occasional dilation | Restrictive physiology; systolic function usually mildly reduced | Specific to type, diagnosis: amyloid, iron, glycogen storage disease, others | See RCM, above | See RCM, above | |

| Inflammatory | Normal or dilated without hypertrophy | Reduced systolic function | Inflammatory infiltrates | Hypereosinophilic syndrome, acute myocarditis | ||

| Ischemic | Normal or dilated without hypertrophy | Reduced systolic function | Areas of infarcted myocardium | Hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, cigarette smoking, family history | Familial hypercholesterolemia; other heritable lipid disorders | Familial hypercholesterolemia |

| Infectious | Normal or dilated without hypertrophy | Reduced systolic function | Specific to infection | Viral (especially acute myocarditis); protozoal (e.g., Chagas disease); bacterial, direct infection (e.g., Lyme disease) or from acute cellular toxicity as result of systemic toxins (e.g., Streptococcus , gram-negative, others) | Genetic predisposition to infection and/or variable response to infective agent | |

LV, Left ventricle; MELAS, mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like symptoms; MERRF, myoclonic epilepsy associated with ragged-red fibers; RV, right ventricle; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

From Falk RH, Hershberger RE: The dilated, restrictive, and infiltrative cardiomyopathies. In Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, editors: Braunwald's heart disease, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2019, Saunders (Table 77.1 ).

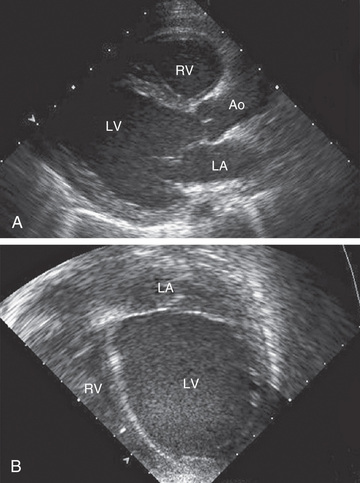

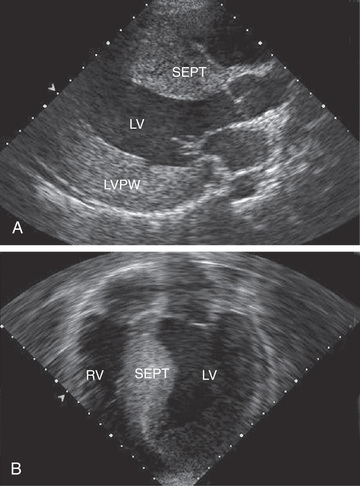

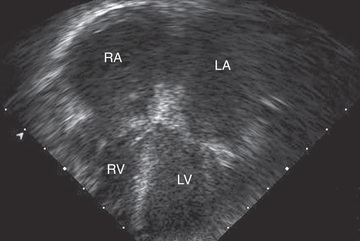

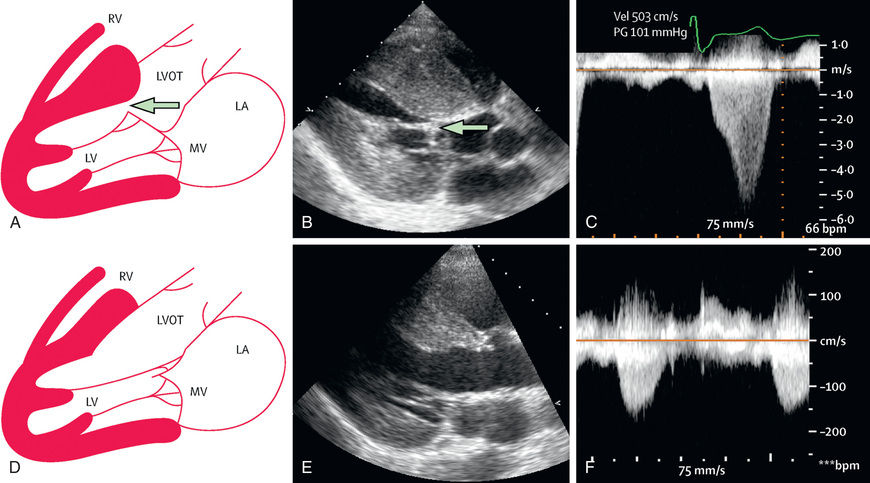

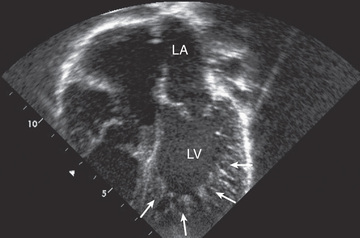

Table 466.2 classifies the cardiomyopathies based on their anatomic (ventricular morphology) and functional pathophysiology. Dilated cardiomyopathy , the most common form of cardiomyopathy, is characterized predominantly by left ventricular (LV) dilation and decreased LV systolic function (Fig. 466.1 ). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy demonstrates increased ventricular myocardial wall thickness, normal or increased systolic function, and often, diastolic (relaxation) abnormalities (Table 466.3 and Figs. 466.2 and 466.3 ). Restrictive cardiomyopathy is characterized by near-normal ventricular chamber size and wall thickness with preserved systolic function, but dramatically impaired diastolic function leading to elevated filling pressures and atrial enlargement (Fig. 466.4 ). Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is characterized by fibrofatty infiltration and replacement of the normal right ventricular (RV) myocardium and occasionally the left ventricle, leading to RV (and LV) systolic and diastolic dysfunction and arrhythmias. Left ventricular noncompaction is characterized by a trabeculated LV apex and lateral wall, with a heterogeneous group of associated phenotypes (most often a dilated phenotype with LV dilation and dysfunction). Cardiomyopathies may be primary or associated with other organ involvement (Tables 466.4 to 466.6 ).

Table 466.2

Etiology of Pediatric Myocardial Disease

| CARDIOMYOPATHY | |

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) | |

| Neuromuscular diseases | Muscular dystrophies (e.g., Duchenne, Becker, limb-girdle, Emery-Dreifuss, congenital muscular dystrophy), myotonic dystrophy, myofibrillar myopathy |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | Fatty acid oxidation disorders (trifunctional protein, VLCAD), carnitine abnormalities (carnitine transport, CPTI, CPTII), mitochondrial disorders (including Kearns-Sayre syndrome), organic acidemias (propionic acidemia), Danon disease (DCM more common in females). |

| Genetic mutations in cardiomyocyte structural apparatus | Familial or sporadic DCM |

| Genetic syndromes | Alström syndrome, Barth syndrome (phospholipid disorders) |

| Ischemic | Most common in adults |

| Chronic tachyarrhythmias | Atrial tachycardias (intractable reentrant supraventricular tachycardia [AVRT, AVNRT], multifocal atrial tachycardia, permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia), ventricular tachycardia |

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) | |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | Mitochondrial disorders (including Friedreich ataxia, mutations in nuclear or mitochondrial genome), storage disorders (glycogen storage disorders, especially Pompe; mucopolysaccharidoses; Fabry disease; sphingolipidoses; hemochromatosis; Danon disease) |

| Genetic mutations in cardiomyocyte structural apparatus | Familial or sporadic HCM |

| Genetic syndromes | Noonan, Costello, cardiofaciocutaneous, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndromes |

| Infant of a diabetic mother | Transient hypertrophy |

| Restrictive Cardiomyopathy (RCM) | |

| Neuromuscular disease | Myofibrillar myopathies |

| Metabolic | Storage disorders |

| Genetic mutations in cardiomyocyte structural apparatus | Familial or sporadic RCM |

| Secondary | Rare in children; radiation therapy of thorax, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis, β-thalassemia |

| Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | |

| Genetic mutations in cardiomyocyte structural apparatus | Familial or sporadic ARVC |

| Left Ventricular Noncompaction | |

| Genetic mutations in cardiomyocyte structural apparatus | LVNC phenotype associated with HCM or DCM |

| Other | X-linked (Barth syndrome), autosomal recessive, mitochondrial inheritance, 1p36 deletion syndrome, and other chromosome abnormalities or genomic disorders; associated with congenital heart defects |

| SECONDARY OR ACQUIRED MYOCARDIAL DISEASE | |

| Myocarditis (see also Table 466.8 ) |

Viral: parvovirus B19, adenovirus, coxsackievirus A and B, echovirus, rubella, varicella, influenza, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, measles, poliomyelitis, smallpox vaccine, hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus 6, HIV, opportunistic infections Rickettsial: psittacosis, Coxiella , Rocky Mountain spotted fever, typhus Bacterial: diphtheria, mycoplasma, meningococcus, leptospirosis, Lyme disease, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, streptococcus, listeriosis Parasitic: Chagas disease, toxoplasmosis, Loa loa, Toxocara canis, schistosomiasis, cysticercosis, echinococcus, trichinosis Fungal: histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, actinomycosis |

| Systemic inflammatory disease | SLE, infant of mother with SLE, scleroderma, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever, sarcoidosis, dermatomyositis, periarteritis nodosa, hypereosinophilic syndrome (Löffler syndrome), acute eosinophilic necrotizing myocarditis, giant cell myocarditis, Kawasaki disease |

| Nutritional deficiency | Beriberi (thiamine deficiency), kwashiorkor, Keshan disease (selenium deficiency) |

| Drugs, toxins | Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), cyclophosphamide, chloroquine, ipecac (emetine), sulfonamides, mesalazine, chloramphenicol, alcohol, hypersensitivity reaction, envenomations, irradiation, herbal remedy (blue cohosh) |

| Coronary artery disease | Kawasaki disease, medial necrosis, anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery, other congenital coronary anomalies (anomalous right coronary artery, coronary ostial stenosis), familial hypercholesterolemia |

| Hematology-oncology | Anemia, sickle cell disease, leukemia |

| Endocrine-neuroendocrine | Hyperthyroidism, carcinoid tumor, pheochromocytoma, adrenal crisis |

| Stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy |

Endocrine (see above) Neurologic (stroke, bleed) Induction of anesthesia Fright Medications/drugs (sympathomimetic agents, venlafaxine) |

CPTI/CPTII, Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1/2; LVNC, left ventricular noncompaction; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; VLCAD, very-long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase.

Table 466.3

| DCM | HCM | RCM | LVNC | ARVC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 50/100,000 | 1/500 | Unknown | Unknown | 1/2,000 |

| Causes | Sarcomeric/cytoskeletal/desmosomal gene mutation, neuromuscular disease, inborn error of metabolism, mitochondrial disease, genetic syndrome, infection | Sarcomeric/cytoskeletal/desmosomal gene mutation, genetic syndrome, inborn error of metabolism/mitochondrial disease | Sarcomeric gene mutation, neuromuscular disease, genetic syndrome | Sarcomeric-cytoskeletal-desmosomal gene mutation, neuromuscular disease, inborn error of metabolism, mitochondrial disease, genetic syndrome | Desmosomal gene mutations |

| Inheritance | 30–50% AD, AR, X-L, Mt | 50% AD, Mt | AD, % unknown | AD, X-L, Mt, % unknown | 30–50% AD, rare AR (Naxos disease; Carvajal syndrome) |

| Sudden death | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Arrhythmias | Atrial, ventricular, and conduction disturbances | Atrial and ventricular | Atrial fibrillation | Atrial, ventricular, and conduction disturbances | Ventricular and conduction disturbances |

| Ventricular function | Systolic and diastolic dysfunction |

Diastolic dysfunction Dynamic systolic outflow obstruction |

Diastolic dysfunction Normal systolic function |

Systolic or diastolic dysfunction | Normal-reduced systolic and diastolic function |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; AD, autosomal dominant inheritance; AR, autosomal recessive inheritance; ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVNC, left ventricular noncompaction; Mt, mitochondrial inheritance; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy; X-L, X-linked inheritance.

Table 466.4

Nuclear DNA Abnormalities Associated With Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmias or Conduction Defects*

| CONDITION | GENETIC DEFECT | HEART FINDINGS | OTHER CLINICAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISOLATED COMPLEX DEFICIENCIES | |||

| Complex I deficiency | Multiple complex I subunit genes, ACAD9, FOXRED 1 | HCM, DCM, LVNC, WPW | Leigh syndrome, FILA. MELAS, leukoencephalopathy, seizures, hypotonia, pigmentary retinopathy, optic atrophy, hearing loss, liver dysfunction |

| Complex II deficiency | SDHA, SDHD | HCM, DCM, LVNC, AF, heart block | Leukoencephalopathy, cerebellar atrophy, seizures, spasticity, myopathy, liver dysfunction, kidney dysfunction |

| Complex III deficiency | BCS1L | HCM | Developmental delay, psychosis, hearing loss |

| Complex IV deficiency | SCO2, SURF1, C2orf64, Cl2orf62, COX6B1 | HCM, DCM | Leigh syndrome, encephalopathy, ataxia, liver dysfunction, kidney dysfunction |

| MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSLATION DEFECTS | |||

| GTP-binding protein-3 deficiency | GTPBP3 | HCM, DCM, heart block, WPW | Leigh syndrome, encephalopathy |

| Mitochondrial translational activator protein deficiency | MTOI | HCM, heart block | Encephalopathy, hypotonia |

| Alanyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency | AARS2 | HCM | Leukoencephalopathy, myopathy |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency | YARS2 | HCM | MLASA syndrome |

| tRNA methyltransferase-5 deficiency | TRMTS | HCM | Developmental delay, hypotonia, peripheral neuropathy, renal tubulopathy |

| RNA processing defect | ELAC2 | HCM, PSVE | Microcephaly, growth deficiency, hearing loss |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal subunit deficiencies | MRPS22, MRPl3, MRPL44 | HCM, WPW | Leukoencephalopathy, seizures, liver dysfunction, renal tubulopathy |

| mtDNA DEPLETION SYNDROMES | |||

| MNGIE | TYMP | Mild or asymptomatic HCM | Leukoencephalopathy, severe gastrointestinal dysmotility, ophthalmoplegia, hearing loss, peripheral neuropathy |

| F-box protein deficiency | FBXL4 | Cardiomyopathy, unspecified | Encephalopathy, brain atrophy |

| Coenzyme Q10 biosynthesis defects | COQ2, COQ4, COQ9 | HCM | Leigh syndrome, encephalomyopathy, retinitis pigmentosa, hearing loss, liver dysfunction, renal tubulopathy |

| 3-METHYLGLUTACONIC ACIDURIAS | |||

| Barth syndrome | TAZ | HCM, DCM, LVNC, EFE, VT, LQTS | Myopathy, short stature, neutropenia |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy and ataxia syndrome | DNAJC19 | DCM, LVNC | Ataxia, optic ataxia, short stature, testicular abnormalities, liver disease |

| Complex V deficiency | TMEM70 | HCM | Cataracts, leukodystrophy, ataxia, myopathy, short stature |

| Sengers syndrome | AGK | HCM | Cataracts, myopathy, exercise intolerance, short stature |

* Examples of conditions that are associated with heart disease and feature abnormal nDNA are shown, along with the causative molecular defects and clinical findings. The genetic defects noted above are provided as major contributors to the various mitochondrial conditions but are not a comprehensive compilation.

AF, Atrial fibrillation; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; EFE, endocardial fibroelastosis; FILA, fatal infantile lactic acidosis; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LQTS, long QT syndrome; MELAS, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MLASA, myopathy, lactic acidosis, sideroblastic anemia; MNGIE, mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy; PSVE, paroxysmal supraventricular extrasystoles; LVNC, left ventricular noncompaction; VT, ventricular tachycardia; WPW, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

From Enns GM: Pediatric mitochondrial diseases and the heart, Curr Opin Pediatr 29:541–551, 2017 (Table 2, p 543).

Table 466.5

Mitochondrial DNA Abnormalities Associated With Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmias or Conduction Defects*

| CONDITION | GENETIC DEFECT | HEART FINDINGS | OTHER CLINICAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kearns-Sayre syndrome | mtDNA deletion | HCM, DCM, heart block, PMVT | Progressive external ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinopathy, cerebellar ataxia, hearing loss, increased CSF protein, diabetes mellitus, renal tubulopathy |

| MELAS | tRNALou point mutation | HCM, DCM, LVNC, RCM, heart block, WPW | Encephalopathy, seizures, stroke-like episodes, headaches, hearing loss, myopathy |

| MERRF | tRNALys point mutation | HCM, DCM, HiCM, WPW | Myoclonus, seizures, ataxia, optic atrophy, hearing loss, short stature |

| Complex I deficiency | Multiple complex I subunit genes | HCM, DCM | Leigh syndrome, leukoencephalopathy, seizures, optic atrophy |

| Complex III deficiency | MTCYB | HCM, DCM, HiCM | Exercise intolerance, myopathy, seizures, optic atrophy, short stature |

| Complex IV deficiency | MT-CO1, MT-CO2, MT-CO3 | HCM, DCM, HiCM | Encephalopathy, seizures, pigmentary retinopathy, hearing loss, myopathy, liver dysfunction |

| Complex V deficiency | MT-ATP6, MT-ATP8 | HCM | Ataxia, peripheral neuropathy |

* Relatively common conditions that are associated with heart disease and feature abnormal mtDNA are shown, along with the most common molecular defects and clinical findings. Although the most common molecular defects are indicated in the table, in most cases multiple genetic abnormalities can cause similar clinical presentations.

CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HiCM, histiocytoid cardiomyopathy; LVNC, left ventricular noncompaction; MELAS, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MERRF, myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers; PMVT, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy; WPW, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

From Enns GM: Pediatric mitochondrial diseases and the heart, Curr Opin Pediatr 29:541–551, 2017 (Table 3, p 546).

Table 466.6

Gene Mutations and Cardiac Manifestations of Neuromuscular Disorders

| DISORDER | GENE MUTATION | CARDIOMYOPATHY | ECG | ARRHYTHMIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Dystrophin | Dilated | Short PR interval, prolonged QT interval, increased QT:PT ratio, right ventricular hypertrophy, deep Q waves II, III, aVF, V5 , V6 | Increased baseline HR, decreased rate variability, premature ventricular beats (58% of patients by 24 yr of age) |

| DMD—female carrier | Dystrophin | Dilated | None | Uncommon |

| Becker muscular dystrophy | Dystrophin | Dilated | Conduction system disease | Similar to DMD |

| Emery-Dreifuss autosomal dominant or proximal dominant limb-girdle muscular dystrophy IB | Lamin A/C | Dilated | Conduction abnormalities: prolonged PR interval, sinus bradycardia | Atrial fibrillation or flutter and atrial standstill; ventricular dysrhythmias |

| Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy | α, β, γ, δ sarcoglycans | Dilated | Incomplete right bundle branch block, tall R waves in VI and V2, left anterior hemiblock | Uncommon |

| Congenital muscular dystrophy | Laminin α2 | Dilated | None | None |

| Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 21 | Fukutin | Dilated | AV node and bundle branch block; age at onset: late teens and early 20s | Atrial arrhythmias and/or ventricular arrhythmias |

| Emery-Dreifuss X-linked | Emerin | Rare | Conduction abnormalities: prolonged PR interval, sinus bradycardia | Atrial fibrillation or flutter and atrial standstill |

| Friedreich ataxia | Frataxin gene | Hypertrophic | T-wave inversion, left axis deviation, repolarization abnormalities | Ventricular arrhythmias |

| Myotonic dystrophy type 1, infantile | Myotonic dystrophy protein kinase gene | Hypertrophic | Conduction disease, prolonged PR interval, widening of QRS complex | Atrial fibrillation and flutter, complete heart block |

| Myotonic dystrophy type 1 | Myotonic dystrophy protein kinase gene | LVNC | Conduction disease, prolonged PR interval, widening of QRS complex | Atrial fibrillation and flutter, complete heart block |

AV, Atrioventricular; HR, heart rate; LVNC, left ventricular noncompaction.

From Hsu DT: Cardiac manifestations of neuromuscular disorders in children, Pediatr Respir Rev 11:35–38, 2010 (Table 1, p 37).

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

John J. Parent, Stephanie M. Ware

Etiology and Epidemiology

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM ), the most common form of cardiomyopathy in children, is the cause of significant morbidity and mortality as well as a common indication for cardiac transplantation. The etiologies are diverse. Unlike adult patients with DCM, ischemic etiologies are rare in children, although these include anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, premature coronary atherosclerosis (homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, rare genetic syndromic disease such as progeria), and coronary inflammatory diseases, such as Kawasaki disease. It is estimated that up to 50% of cases are genetic (usually autosomal dominant; some are autosomal recessive or X-linked), including some with metabolic causes (see Tables 466.1 and 466.2 ). Although the most common etiology of DCM remains idiopathic , it is likely that undiagnosed familial/genetic conditions and myocarditis predominate. The annual incidence of DCM in children younger than 18 yr is 0.57 cases per 100,000 per year. Incidence is higher in males, blacks, and infants <1 yr old.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of the ventricular dilation and altered contractility seen in DCM varies depending on the underlying etiology; systolic dysfunction and myocyte injury are common. Genetic abnormalities of several components of the cardiac muscle, including sarcomere proteins, the cytoskeleton, and the proteins that bridge the contractile apparatus to the cytoskeleton, have been identified in autosomal dominant and X-linked inherited disorders. DCM can occur following viral myocarditis. Although the primary pathogenesis varies from direct myocardial injury to viral-induced inflammatory injury, the resulting myocardial damage, ventricular enlargement, and poor function likely occur by a final common pathway similar to that in genetic disorders.

In 20–50% of cases, the DCM is familial with autosomal dominant inheritance most common (see Table 466.3 ). Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies are X-linked cardiomyopathies that account for 5–10% of DCM cases (see Chapter 627.1 ). These dystrophinopathies result in an abnormal sarcomere-cytoskeleton connection, causing impaired myocardial force generation, myocyte damage/scarring, chamber enlargement, and altered function (see Table 466.6 ). Female carriers of dystrophinopathies may also manifest DCM.

Mitochondrial myopathies , as with the muscular dystrophies, may present clinically with a predominance of extracardiac findings and are inherited in a recessive or mitochondrial pattern (see Tables 466.4 and 466.5 ). Disorders of fatty acid oxidation present with systemic derangements of metabolism (hypoketotic hypoglycemia, acidosis, and hepatic dysfunction), some with peripheral myopathy and neuropathy, and others with sudden death or life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias.

Anthracycline cardiotoxicity (doxorubicin [Adriamycin]) on rare occasion causes acute inflammatory myocardial injury, but more classically results in DCM and occurs in up to 30% of patients given a cumulative dose of doxorubicin exceeding 550 mg/m2 . The risk of toxicity appears to be exacerbated by concomitant radiation therapy. Identifying methods to reduce toxicity and developing precision medicine approaches to identify and treat individuals at high risk are active areas of research.

Clinical Manifestations

Although more prevalent in patients <1 yr of age, all age-groups may be affected. Clinical manifestations of DCM are typically those of heart failure but can also include palpitations, syncope, and sudden death. Irritability or lethargy can be accompanied by additional nonspecific complaints of failure to thrive, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. Respiratory symptoms (tachypnea, wheezing, cough, or dyspnea on exertion) are often present. Infrequently, patients may present acutely with pallor, altered mentation, hypotension, and shock. Patients can be tachycardic with narrow pulse pressure and may have hepatic enlargement and rales or wheezing. The precordial cardiac impulse is increased, and the heart may be enlarged to palpation or percussion. Auscultation may reveal a gallop rhythm in addition to tachycardia and occasionally murmurs of mitral or, less often, tricuspid insufficiency may be present. The presence of hypoglycemia, acidosis, hypotonia, or signs of liver dysfunction suggests an inborn error of metabolism. Neurologic or skeletal muscle deficits are associated with mitochondrial disorders or muscular dystrophies (see Tables 466.4 to 466.6 ).

Laboratory Findings

Electrocardiographic screening reveals atrial or ventricular hypertrophy, nonspecific T-wave abnormalities, and occasionally, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias. The chest radiograph may demonstrate cardiomegaly and pulmonary vascular prominence or pleural effusions. The echocardiogram is often diagnostic, demonstrating the characteristic findings of LV enlargement, decreased ventricular contractility, and occasionally a globular (remodeled) LV contour (see Fig. 466.1 ). RV enlargement and depressed function are occasionally noted. Echo Doppler studies can reveal evidence of pulmonary hypertension, mitral regurgitation, or other structural cardiac or coronary abnormalities. Cardiac MRI is useful for patients with suboptimal imaging echocardiographic windows or in patients with concern of acute myocarditis where, in contrast to echocardiography, recognition of inflammation of the myocardium is possible.

Additional testing may include complete blood count, renal and liver function tests, creatine phosphokinase (CPK), cardiac troponin I, lactate, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), plasma amino acids, urine organic acids, and an acylcarnitine profile. Additional genetic and enzymatic testing may be useful (see Table 466.3 ). Cardiac catheterization and endomyocardial biopsy are not routine but may be useful in patients with acute DCM. Biopsy samples can be examined histologically for the presence of mononuclear cell infiltrates, myocardial damage, storage abnormalities, and for evidence of infection. It is considered standard of care to screen first-degree family members utilizing echocardiography and electrocardiogram (ECG) in idiopathic and familial cases of DCM.

Prognosis and Management

The 1 and 5 yr freedom from death or transplantation in patients diagnosed with DCM is 60–70% and 50–60%, respectively. Independent risk factors at DCM diagnosis for subsequent death or transplantation include older age, heart failure, lower LV fractional shortening z score, and underlying etiology. DCM is the most common cause for cardiac transplantation in pediatric and adult studies.

The therapeutic approach to patients with DCM includes a careful assessment to uncover possible treatable etiologies, screening of family members, and rigorous pharmacologic therapy. Medications aimed at reverse remodeling (improving ventricular size and function) include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) plus β-adrenergic blockade with carvedilol or metoprolol. Each of these medications have proved independently and in combination to improve survival and symptoms and reduce hospital admissions in adults with DCM. Additionally, furosemide may be used to reduce symptoms of pulmonary or systemic venous congestion. Digoxin therapy can also be considered in some patients. Implantable cardiac defibrillators may be considered for certain select patients with a high risk of sudden cardiac arrest. Pacemakers , including dual-chamber and biventricular pacing therapy, can improve patients with certain underlying electrical derangements. In patients presenting with extreme degrees of heart failure or circulatory collapse, intensive care measures are often required, including intravenous inotropes and diuretics, mechanic ventilatory support, and on occasion, mechanical circulatory support, which may include ventricular assist device (VAD), total artificial heart, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and ultimately cardiac transplantation. In patients with DCM and atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, specific antiarrhythmic therapy should be instituted.

Bibliography

Bloom MW, Hamo CE, Cardinale D, et al. Cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction and heart failure. Part 1. Definitions, pathophysiology, risk factors, and imaging. Circ Heart Fail . 2016;9:e002661.

Char DS, Lázaro-Muńoz G, Barnes A, et al. Genomic contraindications for heart transplantation. Pediatrics . 2017;139(4):e20163471.

Ehrhardt MJ, Fulbright JM, Armenian SH. Cardiomyopathy in childhood cancer survivors: lessons from the past and challenges for the future. Curr Oncol Rep . 2016;18:22.

Enns GM. Pediatric mitochondrial diseases and the heart. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:541–551.

Everitt MD, Sleeper LA, Lu M, et al. Recovery of echocardiographic function in children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: results from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2014;63:1405–1413.

Hsu DT. Cardiac manifestations of neuromuscular disorders in children. Paediatr Respir Rev . 2010;11:35–38.

Limongelli G, D'Alessandro R, Maddaloni V, et al. Skeletal muscle involvement in cardiomyopathies. J Cardiovasc Med . 2013;14:837–861.

Patel MD, Mohan J, Schneider C, et al. Pediatric and adult dilated cardiomyopathy represent distinct pathological entities. JCI Insight . 2017;2.

Pietra BA, Kantor PF, Bartlett HL, et al. Early predictors of survival to and after heart transplantation in children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation . 2012;126:1079–1086.

Rusconi P, Wilkinson JD, Sleeper LA. Differences in presentation and outcomes between children with familial dilated cardiomyopathy and children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a report from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry Study Group. Circ Heart Fail . 2017;10.

Ware SM. Genetics of paediatric cardiomyopathies. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29:534–540.

Weintraub RG, Semsarian C, Macdonald P. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet . 2017;390:400–414.

Wildenbeest JG, Wolthers KC, Straver B, et al. Successful IVIG treatment of human parechovirus associated dilated cardiomyopathy in an infant. Pediatrics . 2013;132:e243–e247.

Woiewodski L, Ezon D, Cooper J, Feingold B. Barth syndrome with late-onset cardiomyopathy: a missed opportunity for diagnosis. J Pediatr . 2017;183:196–198.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

John J. Parent, Stephanie M. Ware

Etiology and Epidemiology

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM ) is a heterogeneous, relatively common, and potentially life-threatening form of cardiomyopathy. The causes of HCM include inborn errors of metabolism, neuromuscular disorders, syndromic conditions, and genetic abnormalities of the structural components of the cardiomyocyte (see Tables 466.1 and 466.2 ). Both the age of onset and the associated features are helpful in identifying the underlying etiology.

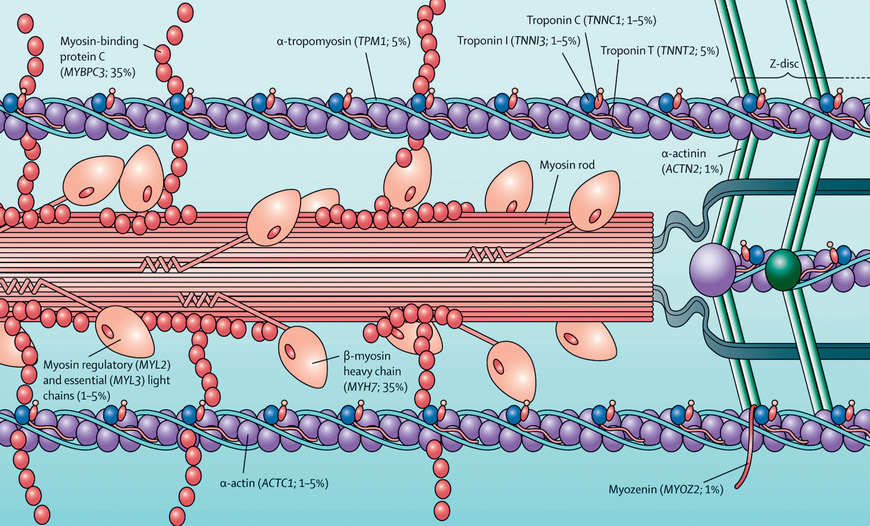

HCM is a genetic disorder and frequently occurs because of mutations in sarcomere or cytoskeletal components of the cardiomyocyte (see Fig. 466.2 ). Mutations of the genes encoding cardiac β-myosin heavy-chain (MYH7) and myosin-binding protein C (MYBPC3) are the most common (see Table 466.3 ). Mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with a high penetrance but variable expressivity. Some patients have mutations in >1 sarcomere or cytoskeletal gene, and some speculate this may lead to earlier disease presentation, but this has not been proved. Additional genetic causes for HCM include nonsarcomeric protein mutations, such as the γ2 -regulatory subunit of adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (PRKAG2) and the lysosome-associated membrane protein 2α-galactosidase (Danon disease , a form of glycogen storage disease). Syndromic conditions, such as Noonan syndrome , may present with HCM at birth, and recognition of extracardiac manifestations is important in making the diagnosis.

Glycogen storage disorders such as Pompe disease often present in infancy with a heart murmur, abnormal ECG, systemic signs and symptoms, and occasionally heart failure. The characteristic ECG in Pompe disease demonstrates prominent P waves, a short P-R interval, and massive QRS voltages. The echocardiogram confirms severe, often concentric, LV hypertrophy.

Pathogenesis

HCM is characterized by the presence of increased LV wall thickness in the absence of structural heart disease or hypertension. Often the interventricular septum is disproportionately involved, leading to the previous designation of idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis or the current term of asymmetric septal hypertrophy . In the presence of a resting or provocable outflow tract gradient, the term hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy is used. Although the left ventricle is predominantly affected, the right ventricle may be involved, particularly in infancy. The mitral valve can demonstrate systolic anterior motion and mitral insufficiency. Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction occurs in 25% of patients, is dynamic in nature, and may in part be secondary to the abnormal position of the mitral valve as well as the obstructing subaortic hypertrophic cardiac muscle. The cardiac myofibrils and myofilaments demonstrate disarray and myocardial fibrosis.

Typically, systolic function is preserved or even hyperdynamic, although systolic dysfunction may occur late and is a predictor for death or need for cardiac transplant. LVOT obstruction with or without mitral insufficiency may be provoked by physiologic manipulations such as the Valsalva maneuver, positional changes, and physical activity. Frequently, the hypertrophic and fibrotic cardiac muscle demonstrates relaxation abnormalities (diminished compliance), and LV filling may be impaired (diastolic dysfunction).

Clinical Manifestations

Many patients are asymptomatic, and 50% of cases present with a heart murmur or during screening when another family member has been diagnosed with HCM. Symptoms of HCM may include palpitations, chest pain, easy fatigability, dyspnea, dizziness, and syncope. Sudden death is a well-recognized but uncommon manifestation that occurs during physical exertion. Characteristic physical examination findings include an overactive precordial impulse with a lift or heave, a systolic ejection murmur in the aortic region not associated with an ejection click, and an apical blowing murmur of mitral insufficiency.

Diagnosis

The ECG typically demonstrates LV hypertrophy with ST segment and T-wave abnormalities (particularly T-wave inversion in the left precordial leads). Intraventricular conduction delays and signs of ventricular preexcitation (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome ) may be present and should raise the possibility of Danon disease or Pompe disease. Chest radiography demonstrates normal or mildly increased heart size with a prominence of the left ventricle. Echocardiography is diagnostic in identifying, localizing, and quantifying the degree of myocardial hypertrophy (see Fig. 466.3 ). Doppler interrogation defines, localizes, and quantifies the degree of LVOT obstruction and also demonstrates and quantifies the degree of mitral insufficiency and diastolic dysfunction.

Cardiac catheterization is rarely used in diagnosis of HCM but may be helpful if there is concern for a myocardial bridge (when a coronary artery runs through vs on top of the myocardium) that may be causing intermittent coronary insufficiency during dynamic obstruction. Myocardial bridges can be seen on coronary angiography. Additionally, cardiac catheterization my occasionally be used to better define hemodynamics in patients.

Additional diagnostic studies include metabolic testing, genetic testing for specific syndromes, or genetic testing for mutations in genes known to cause isolated HCM (see Table 466.3 ). Clinical genetic testing panels continue to expand. Genetic diagnosis is also useful to identify at-risk family members who require ongoing surveillance.

Prognosis and Management

Children <1 yr of age or with inborn errors of metabolism or malformation syndromes or those with a mixed HCM/DCM have a significantly poorer prognosis. The risk of sudden death in older patients is greater in those with a personal or family history of cardiac arrest, ventricular tachycardia, exercise hypotension, syncope, or excessive (>3 cm) ventricular wall thickness. Although intrafamilial variability in symptoms occurs, a family history of sudden death is a highly significant predictor of risk. Restriction from competitive sports and strenuous physical activity is highly recommended, and additional recreational exercise activities should be tailored to each individual based on their overall clinical status. β-Adrenergic blocking agents (propranolol, atenolol, metoprolol) or calcium channel blockers (verapamil) may be useful in diminishing LVOT obstruction, modifying LV hypertrophy, and improving ventricular filling. They also confer an antiarrhythmic benefit and may reduce symptoms. In patients with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, specific antiarrhythmic therapy should be used. Patients with documented, previously aborted sudden cardiac arrest, strong family histories of sudden death, ventricular wall end-diastolic dimensions of ≥3 cm, unexplained syncope, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, or blunted or hypotensive blood pressure response to exercise should be treated with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Early identification of HCM, family screening/surveillance, appropriate activity restriction, and utilization of ICDs have greatly reduced mortality of HCM to approximately 0.5% per year in the modern era.

Innovative interventional procedures have been used to reduce the degree of LVOT obstruction anatomically or physiologically. Dual-chamber pacing, alcohol septal ablation, surgical septal myomectomy, and mitral valve replacement have all met with some success but are typically reserved for patients with significant symptoms despite medical therapy (Fig. 466.5 ).

First-degree relatives of patients identified as having HCM should be screened with ECG and echocardiogram. Genetic testing is available clinically and is of high utility. It is important first to test the affected individual in the family rather than “at-risk” individuals, because 20–50% of cases of HCM will not demonstrate mutations in currently available panels of genes. If a causative mutation is identified, at-risk members of the family can be effectively tested. In families with HCM without demonstrable gene mutations, repeat noninvasive cardiac screening with ECG and echo should be undertaken in at-risk individuals yearly until young adulthood (age 21 yr) and then every 3-5 yr if no prior evidence of HCM is present. Gene-positive but phenotype-negative pediatric patients may remain asymptomatic during childhood but require careful and frequent follow-up.

Bibliography

Maron BJ, Spirito P, Ackerman MJ, et al. Prevention of sudden cardiac death with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in children and adolescents with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2013;61:1527–1535.

Maron MS. Risk stratification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: highly effective, but could it be better? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging . 2017;10.

Munk K, Jensen MK. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in childhood: risk management through family screening. J Pediatr . 2017;188:10–11.

Norrish G, Cantarutti N, Pissaridou E, et al. Risk factors for sudden cardiac death in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol . 2017;24:1220–1230.

Owens AT, Cappola TP. Recreational exercise in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA . 2017;317(13):1319–1320.

Saberi S, Wheeler M, Bragg-Gresham J, et al. Effect of moderate-intensity exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2017;317(13):1349–1356.

Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Kayvanpour E, Tugrul OF, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with sarcomere mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a meta-analysis on 7675 individuals. Clin Res Cardiol . 2018;107(1):30–41.

Soriano-Maldonado A, Vargas-Hitos JA, Jimenez-Jaimez J. Exercise for patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA . 2017;318:480–481.

Tower-Rader A, Betancor J, Lever HM, et al. A comprehensive review of stress testing in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: assessment of functional capacity, identification of prognostic indicators, and detection of coronary artery disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr . 2017;30(9):829–844.

Vermeer AMC, Clur SAB, Blom NA, et al. Penetrance of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children who are mutation positive. J Pediatr . 2017;188:91–95.

Veselka J, Anavekar NS, Charron P. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Lancet . 2017;389:1253–1264.

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

John J. Parent, Stephanie M. Ware

Etiology and Epidemiology

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM ) accounts for <5% of cardiomyopathy cases. Incidence increases with age and is more common in females. In equatorial Africa, RCM accounts for a large number of deaths. Infiltrative myocardial causes and storage disorders frequently result in associated LV hypertrophy and may represent HCM with restrictive physiology. Noninfiltrative causes include mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric or cytoskeletal proteins. Although there has been significant success in discovering new gene mutations causing RCM, the majority of cases are considered idiopathic .

Pathogenesis

RCM is characterized by normal ventricular chamber dimensions, normal myocardial wall thickness, and preserved systolic function. Dramatic atrial dilation can result from the abnormal ventricular myocardial compliance and high ventricular diastolic pressure. Autosomal dominant inheritance has been demonstrated for families with mutations in sarcomeric and cytoskeletal genes.

Clinical Manifestations

Abnormal ventricular filling, sometimes referred to as diastolic heart failure, is manifest in the systemic venous circulation with edema, hepatomegaly, or ascites. Elevation of left-sided filling pressures result in cough, dyspnea, or pulmonary edema. With activity, patients may experience chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope/near-syncope, or even sudden death. Pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular disease develop and may progress rapidly. Heart murmurs are typically absent, but a gallop rhythm may be prominent. In the presence of pulmonary hypertension, an overactive RV impulse and pronounced pulmonary component of the second heart sound (S2 ) are present in RCM.

Diagnosis

The characteristic electrocardiographic finding of prominent P waves is usually associated with normal QRS voltages and nonspecific ST and T-wave changes. RV hypertrophy occurs in patients with pulmonary hypertension. The chest radiograph may be normal or may demonstrate a prominent atrial shadow and pulmonary vascular redistribution. The echocardiogram is often diagnostic, demonstrating normal-sized ventricles with preserved systolic function and dramatic enlargement of the atria (see Fig. 466.4 ). Flow and tissue Doppler interrogation reveal abnormal filling parameters. It is critical to differentiate RCM from constrictive pericarditis , which can be treated surgically (see Chapter 467.2 ). MRI may be necessary to demonstrate the thickened or calcified pericardium often present in constrictive pericardial disease.

Prognosis and Management

Pharmacologic modalities are of limited use, and the prognosis of patients with RCM is generally poor, with often progressive clinical deterioration. Sudden death is a significant risk, with a 2 yr survival of 50%. When signs of heart failure exist, judicious use of diuretics can result in clinical improvement. As a result of the dramatic atrial enlargement and ventricular scarring, these patients are predisposed to the development of atrial tachyarrhythmias, complete heart block, and thromboemboli. Antiarrhythmic agents may be necessary, and anticoagulation with platelet inhibitors or warfarin (Coumadin) is indicated.

Cardiac transplantation is the treatment of choice in many centers for patients with RCM, and the results are excellent in patients without pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary vascular disease, or severe congestive heart failure. Some patients may need bridging to transplant with a VAD if they have elevate pulmonary pressures or significant heart failure.

Bibliography

Mahmoud A, Bansal M, Sengupta PP. New cardiac imaging algorithms to diagnose constrictive pericarditis versus restrictive cardiomyopathy. Curr Cardiol Rep . 2017;19:43.

Rindler TN, Hinton RB, Salomonis N, et al. Molecular characterization of pediatric restrictive cardiomyopathy from integrative genomics. Sci Rep . 2017;7:39276.

Ryan TD, Madueme PC, Jefferies JL, et al. Utility of echocardiography in the assessment of left ventricular diastolic function and restrictive physiology in children and young adults with restrictive cardiomyopathy: a comparative echocardiography-catheterization study. Pediatr Cardiol . 2017;38:381–389.

Webber SA, Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, et al. Outcomes of restrictive cardiomyopathy in childhood and the influence of phenotype: a report from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. Circulation . 2012;126:1237–1244.

Left Ventricular Noncompaction, Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy, Endocardial Fibroelastosis, and Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

John J. Parent, Stephanie M. Ware

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is characterized by a distinctive trabeculated or spongy-appearing left ventricle commonly associated with LV dysfunction and/or dilation and at times hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, and arrhythmias (Fig. 466.6 ). LVNC may be isolated or associated with structural congenital cardiac defects. Patients may present with signs of heart failure, arrhythmias, syncope, sudden death, or as an asymptomatic finding during screening of family members. Whether LVNC represents a an actual cardiomyopathy or is a phenotypic trait associated with cardiomyopathy or congenital heart defects is controversial.

Imaging studies using ultrasound or MRI can demonstrate the characteristic pattern of deeply trabeculated LV myocardium, most characteristically within the apex. ECG findings are nonspecific and include chamber hypertrophy, ST and T-wave changes, or arrhythmias. In some patients, preexcitation is notable, and giant QRS voltages occur in approximately 30% of younger children. Metabolic screening should be considered, especially in young children. Elevated serum lactate and urine 3-methylglutaconic acid may be seen in Barth syndrome , an X-linked disorder of phospholipid metabolism caused by a mutation in the tafazzin (TAZ ) gene. Clinical testing for TAZ mutations is available and should be considered, especially in males. Patients with mitochondrial disorders frequently demonstrate signs of LVNC. These children are at risk for atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and thromboembolic complications. Treatment includes anticoagulation, antiarrhythmic therapy if needed, and treatment of heart failure if present. In patients refractory to medical therapy, cardiac transplantation has been used successfully.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is relatively uncommon in North America compared to the high prevalence in Europe, especially Italy. Autosomal dominant inheritance is common. In addition, recessive forms associated with severe ARVC and skin manifestations are known. Comprehensive genetic screening has been reported to identify a cause in up to 50% of cases. ARVC is typically characterized by a dilated right ventricle with fibrofatty infiltration of the RV wall; increasingly, LV involvement is being recognized. Global and regional RV and LV dysfunction and ventricular tachyarrhythmias are the major clinical findings. Syncope or aborted sudden death can occur and should be treated with antiarrhythmic medications and placement of an ICD. In patients with ventricular dysfunction, heart failure management as indicated for patients with DCM may be of use.

Endocardial fibroelastosis (EFE) , once an important cause of heart failure in children, is uncommon. The decline in primary EFE is likely related to the abolition of mumps virus infections by immunization practices. Rare familial cases exist, but the causative genes are unknown. Secondary EFE can occur with severe left-sided obstructive lesions such as aortic stenosis or atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, or coarctation of the aorta. EFE is characterized by an opaque, white, fibroelastic thickening on the endocardial surface of the ventricle, which leads to systolic and/or diastolic dysfunction. Surgical removal of the endocardial fibrosis has been successfully done to improve cardiac function. Standard heart failure management, including transplantation, has been used in the management of EFE.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a reversible stress-induced syndrome associated with transient systolic and diastolic dysfunction and regional ventricular wall motion abnormalities characterized by ventricular apical ballooning. Physical or emotional stress and associated etiologies (see Table 466.2 ) precipitate transient episodes of chest pain or heart failure. Treatment includes that for heart failure (β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics) and addressing the precipitating event (thyrotoxicosis, pheochromocytoma, drug ingestion).

Bibliography

Arbustini E, Favalli V, Narula N, et al. Left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct genetic cardiomyopathy? J Am Coll Cardiol . 2016;68:949–966.

Beaton A, Mocumbi AO. Diagnosis and management of endomyocardial fibrosis. Cardiol Clin . 2017;35:87–98.

Chebrolu LH, Mehta AM, Nanda NC. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy: the role of advanced multimodality imaging techniques in diagnosis and assessment. Echocardiography . 2017;34:279–289.

Corrado D, Link MS, Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med . 2017;376:61–72.

DePasquale EC, Cheng RK, Deng MC, et al. Survival after heart transplantation in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail . 2017;23:107–112.

Femia G, Sy RW, Puranik R. Systematic review. Impact of the new task force criteria in the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol . 2017;241:311–317.

Gupta U, Makhija P. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy in pediatric patients: a case series of a clinically heterogeneous disease. Pediatr Cardiol . 2017;38:681–690.

Toce MS, Farias M, Bruccoleri R, et al. A case report of reversible takotsubo cardiomyopathy after amphetamine/dextroamphetamine ingestion in a 15-year-old adolescent girl. J Pediatr . 2017;182:385–388.

Myocarditis

John J. Parent, Stephanie M. Ware

Acute or chronic inflammation of the myocardium is characterized by inflammatory cell infiltrates, myocyte necrosis, or myocyte degeneration and may be caused by infectious, connective tissue, granulomatous, toxic, or idiopathic processes. There may be associated systemic manifestations of the disease, and occasionally the endocardium or pericardium is involved, but coronary pathology is uniformly absent. Patients may be asymptomatic, have nonspecific prodromal symptoms, or present with overt congestive heart failure, compromising arrhythmias, or sudden death. It is thought that viral infections are the most common etiology, although myocardial toxins, drug exposures, hypersensitivity reactions, and immune disorders may also lead to myocarditis (Table 466.7 ).

Etiology and Epidemiology

Viral Infections

Coxsackievirus and other enteroviruses, adenovirus, parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr virus, parechovirus, influenza virus, and cytomegalovirus are the most common causative agents in children. In Asia, hepatitis C virus appears to be significant as well. The true incidence of viral myocarditis is unknown because mild cases probably go undetected. The disease is typically sporadic but may be epidemic. Manifestations are, to some degree, age dependent: in neonates and young infants, viral myocarditis can be fulminant; in children it often occurs as an acute, myopericarditis with heart failure; and in older children and adolescents it may present with signs and symptoms of acute or chronic heart failure or chest pain.

Bacterial Infections

Bacterial myocarditis has become much less common with the advent of advanced public health measures, which have minimized infectious causes such as diphtheria. Diphtheritic myocarditis is unique because bacterial toxin may produce circulatory collapse and toxic myocarditis characterized by atrioventricular block, bundle branch block, or ventricular ectopy (see Chapter 214 ). Any overwhelming systemic bacterial infection can manifest with circulatory collapse and shock with evidence of myocardial dysfunction, characterized by tachycardia, gallop rhythm, and low cardiac output. Additional nonviral infectious causes of myocarditis include rickettsiae, protozoa, parasitic infections, and fungal disease.

Pathophysiology

Myocarditis is characterized by myocardial inflammation, injury or necrosis, and ultimately fibrosis. Cardiac enlargement and diminished systolic function are a direct result of the myocardial damage. Typical signs of congestive heart failure occur and may progress rapidly to shock, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death. Viral myocarditis may also become a chronic process, with persistence of viral nucleic acid in the myocardium, and the perpetuation of chronic inflammation secondary to altered host immune response, including activated T lymphocytes (cytotoxic and natural killer cells) and antibody-dependent cell-mediated damage. Additionally, persistent viral infection may alter the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens with resultant exposure of neoantigens to the immune system. Some viral proteins share antigenic epitopes with host cells, resulting in autoimmune damage to the antigenically related myocyte. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 are inhibitors of myocyte response to adrenergic stimuli and result in diminished cardiac function. The final result of viral-associated inflammation can be DCM.

Clinical Manifestations

Manifestations of myocarditis range from asymptomatic or nonspecific generalized illness to acute cardiogenic shock and sudden death. Infants and young children more often have a fulminant presentation with fever, respiratory distress, tachycardia, hypotension, gallop rhythm, and cardiac murmur. Associated findings may include a rash or evidence of end organ involvement such as hepatitis or aseptic meningitis.

Patients with acute or chronic myocarditis may present with chest discomfort, fever, palpitations, easy fatigability, or syncope/near-syncope. Cardiac findings include overactive precordial impulse, gallop rhythm, and apical systolic murmur of mitral insufficiency. In patients with associated pericardial disease, a rub may be noted. Hepatic enlargement, peripheral edema, and pulmonary findings such as wheezes or rales may be present in patients with decompensated heart failure.

Diagnosis

Electrocardiographic changes are nonspecific and may include sinus tachycardia, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, heart block, diminished QRS voltages, and nonspecific ST and T-wave changes, often suggestive of acute ischemia. Chest radiographs in severe, symptomatic cases reveal cardiomegaly, pulmonary vascular prominence, overt pulmonary edema, or pleural effusions. Echocardiography often shows diminished ventricular systolic function, cardiac chamber enlargement, mitral insufficiency, and occasionally, evidence of pericardial infusion.

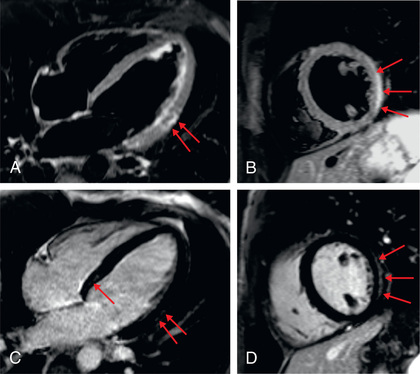

Cardiac MRI is a standard imaging modality for the diagnosis of myocarditis; information on the presence and extent of edema, gadolinium-enhanced hyperemic capillary leak, myocyte necrosis, LV dysfunction, and evidence of an associated pericardial effusion assist in the cardiac MRI diagnosis of myocarditis (Table 466.8 and Fig. 466.7 ).

Table 466.8

MRI Findings Suggestive of Myocarditis

Endomyocardial biopsy may be useful in identifying inflammatory cell infiltrates or myocyte damage and performing molecular viral analysis using polymerase chain reaction techniques. Catheterization and biopsy, although not without risk (perforation and arrhythmias), should be performed by experienced personnel in patients suspected to have myocarditis, or if unusual forms of cardiomyopathy are strongly suspected, such as storage diseases or mitochondrial defects. Nonspecific tests include erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CPK isoenzymes, cardiac troponin I, and BNP levels.

Differential Diagnosis

The predominant diseases mimicking acute myocarditis include carnitine deficiency, other metabolic disorders of energy generation, hereditary mitochondrial defects, idiopathic DCM, pericarditis, EFE, and anomalies of the coronary arteries (see Table 466.2 ).

Treatment

Primary therapy for acute myocarditis is supportive, including β-blockers and ACE inhibitors (see Chapter 469 ). Acutely, the use of inotropic agents, preferably milrinone, should be considered but used with caution because of their proarrhythmic potential. Diuretics are often required as well. If in extremis, mechanical ventilatory support and mechanical circulatory support with VAD implantation or ECMO may be needed to stabilize the patient's hemodynamic status and serve as a bridge to recovery or cardiac transplantation. Diuretics, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs are of use in patients with compensated congestive heart failure in the outpatient setting, but may be contraindicated in those presenting with fulminant heart failure and cardiovascular collapse. In patients manifesting with significant atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, specific antiarrhythmic agents (e.g., amiodarone) should be administered and ICD placement considered.

Immunomodulation of patients with myocarditis is controversial. Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) may have a role in the treatment of acute or fulminant myocarditis, and corticosteroids have been reported to improve cardiac function, but the data are not convincing in children. Relapse has been noted in patients receiving immunosuppression who were weaned from therapy. There are no studies to recommend specific antiviral therapies for myocarditis. Fulminant myocarditis has also been treated with ECMO or a VAD.

Prognosis

The prognosis of symptomatic acute myocarditis in newborns is poor, and a 75% mortality has been reported. The prognosis is better for children and adolescents, although patients who have persistent evidence of DCM often progress to need for cardiac transplantation. Recovery of ventricular function, however, has been reported in 10–50% of patients.

Bibliography

Bergmann KR, Kharbanda A, Haveman L. Myocarditis and pericarditis in the pediatric patient: validated management strategies. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract . 2015;12:1–22 [quiz 23].

Biesbroek PS, Beek AM, Germans T, et al. Diagnosis of myocarditis: current state and future perspectives. Int J Cardiol . 2015;191:211–219.

Bulic A, Maeda K, Zhang Y, et al. Functional status of United States children supported with a left ventricular assist device at heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant . 2017;36:890–896.

Caforio ALP, Malipiero G, Marcolongo R, et al. Myocarditis: a clinical overview. Curr Cardiol Rep . 2017;19:63.

Canter CE, Simpson KE. Diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis in children in the current era. Circulation . 2014;129:115–128.

Comarmond C, Cacoub P. Myocarditis in auto-immune or auto-inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun Rev . 2017;16:811–816.

Feingold B, Mahle WT, Auerbach S, et al. Management of cardiac involvement associated with neuromuscular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation . 2017;136(13):e200–e231.

Ginsberg F, Parrillo JE. Fulminant myocarditis. Crit Care Clin . 2013;29:465–483.

Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(18):1749–1755.

Kindermann I, Barth C, Mahfoud F, et al. Update on myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2012;59(9):779–792.

Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Priori SG. Genetic causes of sudden cardiac death in the young. Curr Opin Cardiol . 2017.

Sinagra G, Anzini M, Pereira NL, et al. Myocarditis in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc . 2016;91:1256–1266.

Teele SA, Allan CK, Laussen PC, et al. Management and outcomes in pediatric patients presenting with acute fulminant myocarditis. J Pediatr . 2011;158:638–643.

Ware SM. Genetics of paediatric cardiomyopathies. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2017;29(5):534–540.

Westphal JG, Rigopoulos AG, Bakogiannis C, et al. The MOGE(S) classification for cardiomyopathies: current status and future outlook. Heart Fail Rev . 2017;22(6):743–752.

Xiong H, Xia B, Zhu J, et al. Clinical outcomes in pediatric patients hospitalized with fulminant myocarditis requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Cardiol . 2017;38:209–214.