Disorders and Anomalies of the Scrotal Contents

Jack S. Elder

Undescended Testis (Cryptorchidism)

The absence of a palpable testis in the scrotum indicates that the testis is undescended, absent, atrophic, or retractile.

Epidemiology

An undescended (cryptorchid) testis is the most common disorder of sexual differentiation in males. At birth, approximately 4.5% of males have an undescended testis. Because testicular descent occurs at 7-8 mo of gestation, 30% of premature male infants have an undescended testis; the incidence is 3.4% at term. As many as 50% of congenital undescended testes descend spontaneously during the first 3 mo of life, and by 6 mo the incidence decreases to 1.5%. Spontaneous descent occurs secondary to a temporary testosterone surge (termed a minipuberty ) during the first 2 mo, which also results in significant penile growth. If the testis has not descended by 4 mo, it will remain undescended. Cryptorchidism is bilateral in 10% of cases. There is some evidence that the incidence of cryptorchidism is increasing. Although cryptorchidism usually is considered to be congenital, some older males have a scrotal testis that “ascends” to a low inguinal position, and therefore requires an orchiopexy. In addition, 1–2% of neonatal and young males undergoing hernia repair develop secondary cryptorchidism from scar tissue along the spermatic cord.

Pathogenesis

The process of testicular descent is regulated by an interaction among genetic, hormonal, and mechanical factors, including testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, müllerian-inhibiting factor, the gubernaculum, intraabdominal pressure, and the genitofemoral nerve. The testis develops in the abdomen at 7-8 wk of gestation. Insulin-like factor 3 controls the transabdominal phase. At 10-11 wk, the Leydig cells produce testosterone, which stimulates differentiation of the wolffian (mesonephric) duct into the epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicle, and ejaculatory duct. At 32-36 wk, the testis, which is anchored at the internal inguinal ring by the gubernaculum, begins its process of descent, and is controlled in part by calcium gene-related peptide produced by the genitofemoral nerve. The gubernaculum distends the inguinal canal and guides the testis into the scrotum. Following testicular descent, the patent processus vaginalis (hernia sac) normally involutes.

Clinical Manifestations

Undescended testes are classified as abdominal (which are nonpalpable), peeping (abdominal but can be pushed into the upper part of the inguinal canal), inguinal, gliding (can be pushed into the scrotum but retracts immediately to the pubic tubercle), and ectopic (superficial inguinal pouch or, rarely, perineal). Most undescended testes are palpable just distal to the inguinal canal over the pubic tubercle.

A disorder of sex development should be suspected in a newborn phenotypic male with bilateral nonpalpable testes, as the child could be a virilized female with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (see Chapter 594 ). In a male with midpenile or proximal hypospadias and a palpable undescended testis, a disorder of sexual development is present in 15%, and the risk is 50% if the testis is nonpalpable.

The potential consequences of cryptorchidism include poor testicular growth, infertility, testicular malignancy, associated hernia, torsion of the cryptorchid testis, and the possible psychological effects of an empty scrotum.

The undescended testis is normal at birth histologically with a plethora of germ cells, but pathologic changes occur by 6-12 mo. Delayed germ cell maturation, germ cell depletion, hyalinization of the seminiferous tubules, and reduced Leydig cell number are typical; these changes are progressive over time if the testis remains undescended. At puberty, an undescended testis has no viable sperm components. Although less severe, changes may occur in the contralateral descended testis after 4-7 yr. After treatment for a unilateral undescended testis, 85% of patients are fertile, which is slightly less than the 90% rate of fertility in an unselected population of adult males. In contrast, following bilateral orchiopexy, only 50–65% of patients are fertile.

The risk of a germ cell malignancy (see Chapter 530 ) developing in an undescended testis is four times higher than in the general population and is approximately 1 in 80 with a unilateral undescended testis and 1 in 40-50 for bilateral undescended testes. Testicular tumors are less common if the orchiopexy is performed before 10 yr of age, but they still occur, and adolescents should be instructed in testicular self-examination. The peak age for developing a malignant testis tumor is 15-45 yr. The most common tumor developing in an undescended testis in an adolescent or adult is a seminoma (65%); after orchiopexy, nonseminomatous tumors represent 65% of testis tumors. Orchiopexy seems to reduce the risk of seminoma. Whether early orchiopexy reduces the risk of developing cancer of the testis is controversial, but it is uncommon for testis tumors to occur if the orchiopexy was performed before age 2 yr. The contralateral scrotal testis is not at increased risk for malignancy.

An indirect inguinal hernia usually accompanies a congenital undescended testis but rarely is symptomatic. Torsion and infarction of the cryptorchid testis also are uncommon but can occur because of excessive mobility of undescended testes. Consequently, inguinal pain and/or swelling in a male with an undescended testis should raise the suspicion of an inguinal hernia or torsion of the undescended testis.

An acquired or ascending undescended testis occurs when a male has a descended testis at birth but during childhood, usually between 4-10 yr of age, the testis does not remain in the scrotum. Such males often have a history of a retractile testis. With testicular ascent on physical examination, the testis can often be manipulated into the upper scrotum, but there is obvious tension on the spermatic cord. This condition is speculated to result from incomplete involution of the processus vaginalis, restricting spermatic cord growth, resulting in the testis gradually moving out of its scrotal position during a male's somatic growth.

On physical examination of the scrotum, the child should be entirely undressed, to help him relax. The examiner should examine the patient's scrotum and inguinal canal using their dominant hand. The nondominant hand is positioned over the pubic tubercle and is pushed inferiorly toward the scrotum. The examiner's dominant hand is used to try to palpate the testis. If the testis is nonpalpable, the soap test often is useful; soap is applied to the inguinal canal and the examiner's hand, significantly reducing friction and facilitating identification of an inguinal testis. In addition, pulling on the scrotum can pull a high inguinal testis into a palpable position. One soft sign that a testis is absent is contralateral testicular hypertrophy, but this finding is not 100% diagnostic.

Retractile testes may be misdiagnosed as undescended testes. Males older than age 1 yr often have a brisk cremasteric reflex, and if the child is anxious or ticklish during scrotal examination, the testis may be difficult to manipulate into the scrotum. Males should be examined with their legs in a relaxed frogleg position, and if the testis can be manipulated into the scrotum comfortably, it is probably retractile. It should be monitored every 6-12 mo with follow-up physical examinations, because it can become an acquired undescended testis. Overall, as many as one third of males with a retractile testis develop an acquired undescended testis requiring orchiopexy, and males younger than 7 yr of age at diagnosis of a retractile testis are at greatest risk. Although definitive data are not available, it is generally thought that males with a retractile testis are not at increased risk for infertility or malignancy.

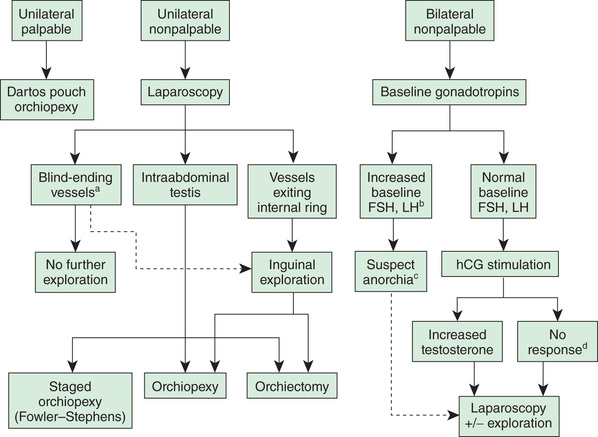

Approximately 10% of undescended testes are nonpalpable testes. Of these, 50% are viable testes in the abdomen or high in the inguinal canal, and 50% are atrophic or absent, almost always in the scrotum, secondary to spermatic cord torsion in utero (vanishing testis). If the nonpalpable testis is abdominal, it will not descend after 3 mo of age. Although sonography often is performed to try to identify whether the testis is present, it rarely changes clinical management, because the abdominal testis and atrophic testis are not identified on sonography. Inguinal/scrotal sonography might be beneficial in obese males with a nonpalpable testis; in this clinical setting, the undescended testis often is nonpalpable, and an inguinal/scrotal sonogram can be beneficial in surgical planning. CT scanning is relatively accurate in demonstrating the presence of the testis, but the radiation exposure is significant. MRI is even more accurate, but the disadvantage is that general anesthesia or sedation is necessary in most young children. None of these imaging studies are 100% accurate and in general do not add significantly to clinical decision making by the pediatric urologist or pediatric surgeon. Consequently, routine use of imaging is discouraged. A diagnostic approach is noted in Figure 560.1 .

Treatment

The congenital undescended testis should be treated surgically by 9-15 mo of age. With anesthesia by a pediatric anesthesiologist, surgical correction at 6 mo is appropriate, because spontaneous descent of the testis will not occur after 4 mo of age. Most testes can be brought down to the scrotum with an orchiopexy, which involves an inguinal incision, mobilization of the testis and spermatic cord, and correction of an indirect inguinal hernia. The procedure is typically performed on an outpatient basis and has a success rate of 98%. In some males with a testis that is close to the scrotum, a prescrotal orchiopexy can be performed. In this procedure, the entire operation is performed through a high scrotal incision. Often the associated inguinal hernia also can be corrected through this incision. Advantages of this approach over the inguinal approach include shorter operative time and less postoperative discomfort.

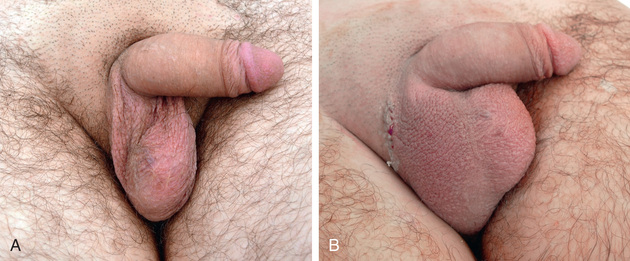

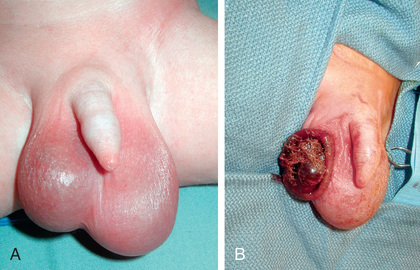

In males with a nonpalpable testis, diagnostic laparoscopy is performed in most centers. This procedure allows safe and rapid assessment of whether the testis is intraabdominal. In most cases, orchiopexy of the intraabdominal testis located adjacent to the internal inguinal ring is successful, but orchiectomy should be considered in more difficult cases or when the testis appears to be atrophic. A two-stage orchiopexy sometimes is needed in males with a high abdominal testis. Males with abdominal testes are managed with laparoscopic techniques at many institutions. Testicular prostheses are available for older children and adolescents when the absence of the gonad in the scrotum might have an undesirable psychological effect. The FDA has approved a saline testicular implant. Solid silicone “carving block” implants also are used (Fig. 560.2 ). Placement of testicular prostheses early in childhood is recommended for males with anorchia (absence of both testes).

The American Urological Association released guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of males with an undescended testis in 2014. Table 560.1 summarizes the primary statements.

Table 560.1

Adapted from Kolon TF, Herndon CDA, Baker LA, et al: Evaluation and treatment of cryptorchidism: AUA Guideline. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Cryptorchidism.pdf

Scrotal Swelling

Scrotal swelling may be acute or chronic and painful or painless (Table 560.2 ). Abrupt onset of painful scrotal swelling necessitates prompt evaluation because some conditions, such as testicular torsion and incarcerated inguinal hernia, require emergency surgical management. Tables 560.3 and 560.4 show the differential diagnosis.

Table 560.2

Differential Diagnosis of Pediatric Adolescent Acute Scrotal Pain

Modified from Palmer LS, Palmer JS: Management of abnormalities of the external genitalia in boys. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LRR, Partin AW, Peters CA (eds): Campbell-Walsh Urology, 4th ed, Vol 4, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier, Box 146-2, p. 3388.

Table 560.3

| PAINFUL |

| Testicular torsion |

| Torsion of appendix testis |

| Epididymitis |

| Trauma: ruptured testis, hematocele |

| Inguinal hernia (incarcerated) |

| Mumps orchitis |

| Testicular vasculitis |

| PAINLESS |

| Hydrocele |

| Inguinal hernia* |

| Varicocele* |

| Spermatocele* |

| Testicular tumor* |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura* |

| Idiopathic scrotal edema |

* May be associated with discomfort.

Table 560.4

| Hydrocele |

| Inguinal hernia (reducible) |

| Inguinal hernia (incarcerated)* |

| Testicular torsion* |

| Scrotal hematoma |

| Testicular tumor |

| Meconium peritonitis |

| Epididymitis* |

* May be associated with discomfort.

Clinical Manifestations

A detailed history is helpful in determining the cause of the swelling and includes the onset of pain—with testicular torsion, the pain often is sudden in onset and may be associated with exercise or minor genital trauma; duration of pain; radiation of pain—inguinal discomfort is common with testicular torsion, inguinal hernia, or epididymitis, and associated flank pain can occur with passage of a ureteral calculus; previous episodes of similar pain, which are common in males with intermittent testicular torsion or inguinal hernia; nausea and vomiting, which are associated with testicular torsion and inguinal hernia; and irritative urinary symptoms, such as dysuria, urgency, and frequency, which indicate a urinary tract infection that can cause epididymitis. Some males report a recent history of scrotal trauma. There are multiple reports of familial testicular torsion. Males with lower urinary tract pathology such as urethral stricture or neuropathic bladder may be prone to epididymitis.

Physical examination may be difficult in males with a painful scrotum. Some have advocated performing a spermatic cord block or administering intravenous analgesia to facilitate the examination, but such measures usually are unnecessary. Scrotal wall erythema is common in testicular torsion, epididymitis, torsion of the appendix testis, and an incarcerated hernia. In males with a normal cremasteric reflex, testicular torsion is unlikely. Absence of a cremasteric reflex is nondiagnostic.

Laboratory Findings and Diagnosis

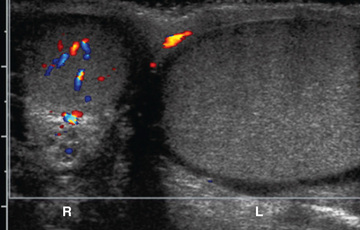

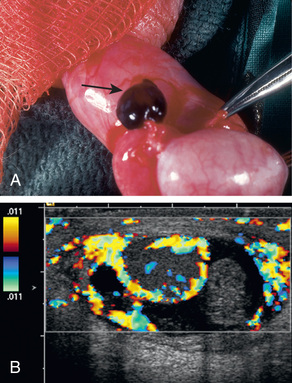

Pertinent laboratory studies include a urinalysis and culture. A positive urinalysis suggests bacterial epididymitis (uncommon before adolescence). Serum studies are not helpful in establishing a diagnosis unless a testicular malignancy is suspected. After initial evaluation, in males with testicular pain color Doppler ultrasonography often is helpful in establishing the diagnosis because it assesses whether testicular blood flow is normal, reduced, or increased (Fig. 560.3 ). If a hydrocele is present and the testis is nonpalpable, or if an abnormality of the testis is found, sonography also is indicated. Imaging studies are not 100% accurate; they should not be used to decide whether a male with testicular pain should be referred for urologic evaluation.

Color Doppler ultrasonography allows assessment of testicular blood flow and testicular morphologic features. Accuracy is > 95% if the ultrasonographer is experienced and the patient is older than 2 yr old. A false-negative study (demonstrates normal testicular blood flow) can occur in a male with testicular torsion if the degree of torsion is < 360 degrees and the duration of torsion is short, because there may be continued testicular perfusion. In males < 1 yr of age, including neonates, blood flow may be difficult to demonstrate in 15% of normal testes.

Testicular (Spermatic Cord) Torsion

Etiology

Testicular torsion requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to salvage the testis. Torsion is the most common cause of severe testicular pain in males age 12 yr and older, and is uncommon before age 10 yr. It is caused by inadequate fixation of the testis within the scrotum, resulting from a redundant tunica vaginalis and abnormal gubernacular attachment, allowing excessive mobility of the testis. The abnormal attachment is termed a bell clapper deformity and may be bilateral. Following spermatic cord torsion, venous congestion occurs, and subsequently arterial flow is interrupted. The likelihood of testis survival depends on the duration and severity of torsion. Following 4-6 hr of absent blood flow to the testis, irreversible loss of spermatogenesis can occur. Torsion is familial in 10% of males.

Diagnosis

Testicular torsion produces acute pain and swelling of the scrotum. On examination, the scrotum is swollen, and the testis is exquisitely tender and often difficult to examine. The cremasteric reflex nearly always is absent. The position (lie) of the testis is abnormal, and the testis position often is high in the scrotum. In addition, often there is associated nausea and vomiting. The condition can be differentiated from an incarcerated hernia because swelling in the inguinal area typically is absent with torsion. If the pain duration is < 4-6 hr, manual detorsion may be attempted. In 65% of cases the torsed testis rotates inward, so detorsion should be attempted in the opposite direction (e.g., the left testis is rotated clockwise). Successful manual detorsion results in dramatic pain relief. In the emergency department, prompt scrotal ultrasound should be performed. In some centers, this is performed as a point of care procedure by the emergency department staff.

Some adolescents experience intermittent testicular torsion . These males report episodes of severe unilateral testicular pain that resolves spontaneously after 30-60 min. Treatment is elective bilateral scrotal orchiopexy (see Treatment ).

Treatment

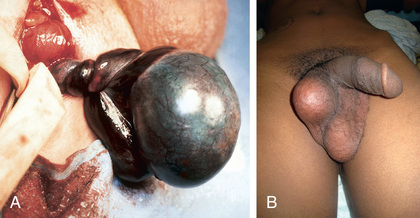

Treatment is prompt surgical exploration and detorsion. If the testis is explored within 6 hr of torsion, up to 90% of the gonads survive. Testicular salvage decreases rapidly with a delay of > 6 hr. If the degree of torsion is 360 degrees or less, the testis might have sufficient arterial flow to allow the gonad to survive, even after 24-48 hr. Following detorsion, the testis is fixed in the scrotum with nonabsorbable sutures, termed scrotal orchiopexy, to prevent torsion in the future. The contralateral testis also should be fixed in the scrotum because the predisposing anatomic condition often is bilateral. If the testis appears nonviable, orchiectomy is performed (Fig. 560.4A ). The detorsed testis may undergo compartment syndrome, and following detorsion, despite blood flow to the testis, high intratesticular pressure may cause ischemia and necrosis. This condition has been treated intraoperatively by incising the tunica vaginalis (similar to a blunt testicular rupture) and placing a tunica vaginalis flap over the exposed tunica. Some adolescents do not undergo prompt evaluation and treatment and present with late phase testicular torsion, in which there is delayed diagnosis of torsion. Often the testis is high in the scrotum and nontender (see Fig. 560.4B ). Fertility is reduced in adult males who experience spermatic cord torsion in adolescence, irrespective of whether detorsion or orchiectomy is performed.

Spermatic cord torsion also can occur in the fetus or neonate. This condition results from incomplete attachment of the tunica vaginalis to the scrotal wall and is “extravaginal.” When torsion occurs just before delivery, the baby usually is born with a large, firm, nontender testis. Usually the ipsilateral hemiscrotum is ecchymotic (Fig. 560.5 ). In these cases, the testis rarely is viable because torsion was a remote event. However, the contralateral testis is at increased risk for torsion until 1-2 mo beyond term. The pediatric urology community is divided regarding whether immediate exploration is necessary in a male newborn who has suspected testicular torsion at birth, but if observation is recommended, the family needs to be counseled regarding the risk of contralateral spermatic cord torsion. If the initial exam is normal and the newborn subsequently develops scrotal swelling and erythema, and imaging is consistent with spermatic cord torsion, emergency scrotal exploration is indicated.

Torsion of the Appendix Testis/Epididymis

Torsion of the appendix testis is the most common cause of testicular pain in males 4-10 yr but is uncommon in adolescents. The appendix testis is a stalk-like structure that is a vestigial embryonic remnant of the müllerian (paramesonephric) ductal system that is attached to the upper pole of the testis. When it undergoes torsion, progressive inflammation and swelling of the testis and epididymis occurs, resulting in testicular pain and scrotal erythema. The onset of pain usually is gradual. Palpation of the testis usually reveals a 3- to 5-mm tender indurated mass on the upper pole (Fig. 560.6A ). In some cases, the appendage that has undergone torsion may be visible through the scrotal skin, termed the “blue dot” sign. In some males, distinguishing torsion of the appendix from testicular torsion is difficult. In such cases, color Doppler ultrasonography is useful because testicular blood flow is normal and shows hyperemia to the upper pole of the testis. In such cases, the radiologist often recognizes epididymal enlargement and makes the diagnosis of epididymitis, reflecting the inflammatory reaction (see Fig. 560.6B ).

The natural history of torsion of the appendix testis is for the inflammation to resolve in 3-10 days. Nonoperative treatment is recommended, including bed rest for 24 hr and analgesia with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication for 5 days. If the diagnosis is uncertain, scrotal exploration is recommended.

Epididymitis

Acute bacterial inflammation of the epididymis is an ascending retrograde infection from the urethra, through the vas into the epididymis. This condition causes acute scrotal pain, erythema, and swelling. It is rare before puberty and should raise the question of a congenital abnormality of the wolffian duct, such as an ectopic ureter entering the vas. In younger males, the responsible organism is often Escherichia coli (see Chapter 227 ). After puberty, bacterial epididymitis becomes progressively more common and can cause acute painful scrotal swelling in young sexually active males. Urinalysis usually reveals pyuria. Epididymitis can be infectious (usually gonococcus or Chlamydia ; see Chapters 219 and 253 ), but often the organism remains undetermined. Additional etiologies include familial Mediterranean fever, enterovirus, and adenoviruses. Treatment consists of bed rest and antibiotics as indicated. Differentiation from torsion is straightforward with scrotal ultrasonography.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (see Chapter 192.1 ) is a systemic vasculitis that involves multiple organ systems and that can involve the kidney and spermatic cord. When the spermatic cord is involved, typically there is bilateral painful scrotal swelling with purpuric lesions involving the scrotum. Scrotal sonography should show normal testicular blood flow. Treatment is directed toward systemic treatment of the Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Isolated testicular vasculitis is less common in Henoch-Schönlein purpura and, in such cases, polyarteritis nodosa should be suspected.

Varicocele

A varicocele is a congenital condition in which there is abnormal dilation of the pampiniform plexus in the scrotum, often described as a “bag of worms” (Fig. 560.7 ). Dilation of the pampiniform venous plexus results from valvular incompetence of the internal spermatic vein. Approximately 15% of adult males have a varicocele; of these, approximately 10–15% are subfertile. Varicocele is the most common (and virtually the only) surgically correctable cause of infertility in males. A varicocele is found in 10–15% of adolescent males, but it rarely is diagnosed in males younger than 10 yr old, because the varicocele becomes distended only after the increased blood flow associated with puberty occurs. Varicoceles occur predominantly on the left side, are bilateral in 2% of cases, and rarely involve the right side only. A varicocele in a male younger than age 10 yr or on the right side might indicate an abdominal or retroperitoneal mass; an abdominal sonogram or CT scan should be performed in such cases.

A varicocele typically is a painless paratesticular mass. Occasionally patients describe a dull ache in the affected testis. Usually the varicocele is not apparent when the patient is supine because it is decompressed; in contrast, the varicocele becomes prominent when the patient is standing and enlarges with a Valsalva maneuver. Many pediatricians do not routinely screen adolescents for a varicocele. Varicoceles typically are graded from 1-3 with the male standing: grade 1 is palpable only with Valsalva (clinically insignificant); grade 2 is palpable without Valsalva but is not visible on inspection; and grade 3 is visible with inspection. Males with a grade 3 varicocele are at greatest risk for testicular growth arrest, particularly if the varicocele is larger than the testis. Testicular size should be documented with calipers, an orchidometer, or scrotal sonography, because if the affected left testis is significantly smaller than the right testis, spermatogenesis probably has been adversely affected. A semen analysis should be considered in sexually mature adolescents who are Tanner stage V.

The goal of varicocelectomy is to maximize future fertility. Surgical treatment of varicoceles is indicated in males with a significant disparity in testicular size, with pain in the affected testis, if the contralateral testis is diseased or absent, or with oligospermia on semen analysis. Following treatment, typically the involved testis enlarges and catches up with the normal testis over the following 1-2 yr. Varicocelectomy should also be considered in males with a large grade 3 varicocele, even if there is not a disparity in testicular size. Surgical repair is accomplished with a variety of techniques by ligation of the veins of the pampiniform plexus laparoscopically or through an inguinal or subinguinal incision (with or without an operating microscope) or by ligating the internal spermatic vein in the retroperitoneum. The operation is performed on an ambulatory basis.

Spermatocele

A spermatocele is a cystic lesion that contains sperm and is attached to the upper pole of the sexually mature testis. Spermatoceles usually are painless and are incidental findings on physical examination. Enlargement of the spermatocele or significant pain is an indication for removal.

Hydrocele

Etiology

A hydrocele is an accumulation of fluid in the tunica vaginalis (Fig. 560.8 ). Between 1% and 2% of neonates have a hydrocele. In most cases, the hydrocele is noncommunicating (the processus vaginalis was obliterated during development). In such cases, the hydrocele fluid disappears by 1 yr of age. If there is a persistently patent processus vaginalis, the hydrocele persists and may become larger during the day and is small in the morning. A rare variant of a hydrocele is the abdominoscrotal hydrocele, in which there is a large, tense hydrocele that extends into the lower abdominal cavity. In some older males, a noncommunicating hydrocele can result from an inflammatory condition within the scrotum, such as testicular torsion, torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, or testicular tumor. The long-term risk of a communicating hydrocele is the development of an inguinal hernia. Some older males and adolescents also develop a hydrocele. In some cases, hydrocele develop acutely after an episode of scrotal trauma or epididymoorchitis, whereas others develop more insidiously.

Diagnosis

On examination, hydroceles are smooth and nontender. Transillumination of the scrotum confirms the fluid-filled nature of the mass. It is important to palpate the testis, because some young males develop a hydrocele in association with a testis tumor. If the testis is nonpalpable, a scrotal ultrasound should be performed to confirm that the testis is present and normal. If compression of the fluid-filled mass completely reduces the hydrocele, an inguinal hernia/hydrocele is the likely diagnosis.

Treatment

Most congenital hydroceles resolve by 12 mo of age following reabsorption of the hydrocele fluid. If the hydrocele is large and tense, however, early surgical correction should be considered, because it is difficult to verify that the child does not have a hernia, and large hydroceles rarely disappear spontaneously. Hydroceles persisting beyond 12-18 mo often are communicating and should be repaired. Surgical correction is similar to a herniorrhaphy (see Chapter 373 ). Through an inguinal incision, the spermatic cord is identified, the hydrocele fluid is drained, and a high ligation of the processus vaginalis is performed. If an older male has a large hydrocele, often diagnostic laparoscopy can be performed to determine whether there is a patent processus vaginalis, and if the internal ring is closed, then the hydrocele may be corrected with a scrotal incision.

Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernia is discussed in Chapter 373 .

Testicular Microlithiasis

Approximately 2–3% of pediatric scrotal ultrasound examinations demonstrate calcific depositions in the testis, termed testicular microlithiasis. Typically, it is found in males undergoing an examination for testicular pain, varicocele, or scrotal swelling. In adults, it is a common finding in males with infertility and with a germ cell tumor of the testis. In pediatric patients with microlithiasis, there are no guidelines for monitoring, but the condition should be monitored for changes in testicular size or induration, with follow-up ultrasound studies as indicated.

Testicular Tumor

Testicular and paratesticular tumors can occur at any age, even in the newborn. Approximately 35% of prepubertal testis tumors are malignant; most commonly they are yolk sac tumors, although rhabdomyosarcoma and leukemia also can occur in this age-group. In adolescents, 98% of painless solid testicular masses are malignant (see Chapter 530 ). Most manifest as a painless, hard testicular mass that does not transilluminate. Scrotal ultrasonography should be performed to confirm the finding of a testicular mass, and it can help to delineate the type of testis tumor. Serum tumor markers, including α-fetoprotein and β-human chorionic gonadotropin, should be drawn. Definitive therapy includes surgical exploration through an inguinal incision. In most cases, a radical orchiectomy, consisting of removal of the entire testis and spermatic cord, is performed. In a prepubertal male, if the ultrasonographic study or surgical exploration suggests that the tumor is localized and benign, such as a teratoma or an epidermoid cyst, testis-sparing surgery with removal only of the mass may be appropriate.

Testicular microlithiasis identified incidentally with ultrasonography may be a risk factor for future neoplasia.