Vulvovaginitis

Helen M. Oquendo Del Toro, Holly R. Hoefgen

Vulvovaginitis is the most common gynecologic-based problem for prepubertal children, with a reported incidence of 17–50%. It is most typically caused by either inadequate or excessive hygiene or chemical irritants. The age of presentation peaks at 4 and 8 yr of age. The condition is usually improved by hygiene measures and education of the caregivers and child.

Etiology

Vulvitis refers to external genital pruritus, burning, redness, or rash. Vaginitis implies inflammation of the vagina, which can manifest as a discharge with or without an odor or bleeding. These may occur simultaneously as vulvovaginitis. When a child presents with vulvovaginitis, the history should include questions on hygiene (wiping from front to back) and information about possible exposure to chemical irritants (bath soaps, bubble bath, laundry detergents, swimming pools, or hot tubs). A detailed history of recent diarrhea, perianal itching, or nighttime itching is important. The possibility of foreign objects being placed into the vagina should also be asked, although the young child is unlikely to remember or recall. However, approximately 75% of cases of vulvovaginitis in children are nonspecific for a variety of reasons, including their lack of vaginal estrogenization and resulting atrophy and alkalinic pH, poor perianal hygiene, and the proximity of the anus to the vagina, which is without geographic barriers given the flattened labia and lack of pubic hair (Fig. 564.1 and Table 564.1 ).

Table 564.1

Specific Vulvar Disorders in Children

| CONDITION | PRESENTATION | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molluscum contagiosum (Fig. 564.8 ) | Diagnosis usually is made by visual inspection. |

The disease generally is self-limited and the lesions can resolve spontaneously. Treatment choices in children may include cryosurgery, laser, application of topical anesthetic and curettage, podophyllotoxin, and topical silver nitrate. Use of topical 5% imiquimod cream and 10% potassium hydroxide has been reported with similar effects. |

|

| Condyloma acuminata | Skin-colored papules, some with a shaggy, cauliflower-like appearance | Diagnosis usually is made by visual inspection. Biopsy should be reserved for when the diagnosis is in question. Human papillomavirus DNA testing is not helpful. | Many lesions in children resolve spontaneously, “wait and see” often utilized in children (60 days). Topical treatment with imiquimod cream and podophyllotoxin is the most studied (daily qhs 3 times/wk × 16 wk, wash 6-10 hr after application). General anesthesia is usually required for surgical/ablative procedures (cryotherapy, laser therapy, electrocautery); reserve for symptomatic or large lesions. Other treatments have been utilized in adults, including trichloroacetic acid, 5-fluorouracil, sine catechins, topical cidofovir, and cimetidine. The efficacy and safety of these treatments in children has not been established. |

| Herpes simplex | Blisters that break, leaving tender ulcers | Visual inspection confirmed by culture from lesion. |

Infants: Acyclovir 20 mg/kg body weight IV q8 hr × 21 days for disseminated and central nervous system disease or × 14 days for disease limited to the skin and mucous membranes. Genital/mucocutaneous disease: Age 3 mo–2 yr: 15 mg/kg/day IV divided in q8h × 5-7 days. Age 2-12 yr (1st episode): Same as above or 1,200 mg/day divided in q8h dosing × 7-10 days. Age 2-12 yr (recurrence): 1,200 mg/day in q8h dosing or 1,600 mg/day in bid dosing × 5 days (give 3-5 days for children older than 12 yr). |

| Labial agglutination (see Fig. 564.1 ) | May be asymptomatic or can cause vulvitis, urinary dribbling, urinary tract infection, or urethritis | Diagnosis is made by visual inspection of the adherent labia, often with a central semitranslucent line. |

Does not require treatment if the patient is asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients: Topical estrogen cream or betamethasone ointment applied alone or in combination daily for 6 wk directly to the line of adhesion, using a cotton swab while applying gentle labial traction. Estrogen should be interrupted if breast budding occurs. Mechanical or surgical separation of the adhesions is rarely indicated. The adhesions usually resolve in 6-12 wk; unless good hygiene measures are followed, recurrence is common. To decrease the risk of recurrence, an emollient (petroleum jelly, A and D ointment) should be applied to the inner labia for 1 mo or longer at bedtime. |

| Lichen sclerosus (see Fig. 564.4 ) |

A sclerotic, atrophic, parchment-like plaque with an hourglass or keyhole appearance of vulvar, perianal, or perineal skin, subepithelial hemorrhages may be misinterpreted as sexual abuse or trauma. The patient can experience perineal itching, soreness, or dysuria. |

Diagnosis usually is made by visual inspection. Biopsy should be reserved for when the diagnosis is in question. |

Ultrapotent topical corticosteroids are the first-line therapy (clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%) once or twice a day for 4-8 wk. Once symptoms are under control, the patient should be tapered off the drug unless therapy is required for a flare-up. In many girls, the condition resolves with puberty; however, this is not always the case and patients may require long-term follow-up. Immunomodulators can be used: tacrolimus 1% (applied once daily) and pimecrolimus 1% (applied twice daily for 3 mo, then every other day). |

| Psoriasis | Children are more likely than adults to have vulvar psoriasis noted as pruritic, well-demarcated, nonscaly, brightly erythematous, symmetric plaques. The classic extragenital lesions are similar but with a silver scaly appearance. | Diagnosis may be confirmed by locating other affected areas on the scalp or in nasolabial folds or behind the ears. | Vulvar lesions may be treated with low- to medium-potency topical corticosteroids, increasing strength as necessary. |

| Atopic dermatitis |

Chronic cases can result in crusty, weepy lesions that are accompanied by intense pruritus and erythema. Scratching often results in excoriation of the lesions and secondary bacterial or candidal infection. |

It may be seen in the vulvar area but characteristically affects the face, neck, chest, and extremities. |

Children with this condition should avoid common irritants and use topical corticosteroids (such as 1% hydrocortisone) for flare-ups. If dry skin is present, lotion or bath oil can be used to seal in moisture after bathing. |

| Contact dermatitis | Erythematous, edematous, or weepy vulvar vesicles or pustules can result, but more often the skin appears inflamed. | Associated with exposure to an irritant, such as perfumed soaps, bubble bath, talcum powder, lotions, elastic bands of undergarments, or disposable diaper components. |

Avoidance of irritant. Topical corticosteroids for flare-ups. |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Erythematous and greasy, yellowish scaling on vulva and labial crural folds associated with greasy dandruff-type rash of scalp, behind ears and face. | Diagnosis usually is made by visual inspection. | Gentle cleaning, topical clotrimazole with 1% hydrocortisone added. |

| Vitiligo (see Fig. 564.5 ) | Sharply demarcated hypopigmented patches, often symmetric in vaginal and anal regions. May be present in periphery at body orifices and extensor surfaces. | Clinical. Test for associated illness if clinically warranted (thyroid disease, Addison disease, pernicious anemia, diabetes mellitus). | If desired, treat limited lesions with low-potency corticosteroids or tacrolimus. See dermatologist for extensive lesions. |

Epidemiology

Infectious vulvovaginitis, where a specific pathogen is isolated as the cause of symptoms, is most commonly associated with fecal or respiratory pathogens, and cultures may reveal Escherichia coli (see Chapter 227 ), Streptococcus pyogenes (Chapter 210 ), Staphylococcus aureus (see Chapter 208 ), Haemophilus influenzae (see Chapter 221 ), Enterobius vermicularis (Chapter 320 ), and, rarely, Candida spp. (see Chapter 261 ). These organisms may be transmitted by the child using improper toilet hygiene and manually from the nasopharynx to the vagina. The children present with perianal redness, introital inflammation, and often a yellow-green or mildly bloody discharge. They may be observed to be grabbing their genital area or “digging” in their underwear, which is usually stained with yellow-brown discharge. Attempts to treat these bacterial etiologies with antifungal medication will fail and often the antifungal product will lead to more irritation. Table 564.2 gives specific treatment recommendations based on the bacteria localized.

Table 564.2

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis also are causes of specific infectious vulvovaginitis (see Chapter 146 ). Management of prepubertal children who have sexually transmitted infections requires close cooperation between clinicians and child-protection authorities. Official investigations for sexual abuse, when indicated, should be initiated promptly (see Chapter 16 ). If acquired after the neonatal period, some diseases (e.g., gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia) are virtually 100% indicative of sexual contact. For other diseases (e.g., human papillomavirus infection and herpes simplex virus), the association with sexual contact is not as clear. Presumptive treatment for prepubertal children who have been sexually assaulted or abused is not recommended, because (1) the incidence of most sexually transmitted infections in children is low after abuse/assault, (2) prepubertal girls appear to be at lower risk for ascending infection than adolescent or adult women, and (3) regular follow-up of children usually can be ensured. Although Trichomonas vaginalis can be transmitted vertically and can be seen in children up to 1 yr of age, it is an uncommon cause of specific infectious vulvovaginitis in the unestrogenized prepubertal girl.

Other causes of specific infectious vulvovaginitis include Shigella (see Chapter 226 ), which often manifests with a blood-tinged purulent discharge, and Yersinia enterocolitica (see Chapter 230 ). Candida infections (yeast) commonly cause diaper rash, but they are unlikely to cause vaginitis in children because the alkaline pH of the prepubertal vagina does not support fungal infections. Diabetic or immunocompromised children and children taking prolonged antibiotics may be at increased risk for fungal vaginitis. Pinworms are the most common helminthic infestation in the United States, with the highest rates in school-age and preschool children. Perianal itching can lead to excoriation and, rarely, bleeding.

Clinical Manifestations

Diaper Dermatitis

Diaper dermatitis is the most common dermatologic problem in infancy and occurs in half of all diaper-wearing infants and children. The moisture and contact with urine and feces irritates the skin, and colonization with Candida spp. increases the severity of the dermatitis. First-line treatment includes hygiene measures such as increasing the frequency of diaper changes, allowing the infant to be diaper free, frequent bathing, and application of water-repellant barriers such as zinc oxide. If diaper dermatitis persists after these conservative measures, or if the classic satellite lesions of Candida are present, treatment with a topical antifungal can decrease the inflammation.

Physiologic Leukorrhea

Neonates and peripubertal girls can present with a white or clear or mucus discharge, which is a physiologic effect of estrogen. Some girls may complain of the moisture and mucus. Hygiene measures including baths may help but an explanation should reassure the patient and her mother.

Labial Agglutination

Labial agglutination (labial adhesions) are described most frequently in infants and young children. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to an inflammatory response in the labia minora in combination with a hypoestrogenic state. Diagnosis is usually done on routine genital examination. Asymptomatic patients usually require no intervention. First-line therapy in patients with difficulty voiding, persistent infections, or pain includes topical estrogen (Premarin or Estrace cream 0.01%) or a topical steroid (Betamethasone 0.05% ointment) applied twice daily to the midline raphe under gentle traction. Surgical correction is rarely necessary, but recurrence is common until the age of puberty.

Genital Ulcers

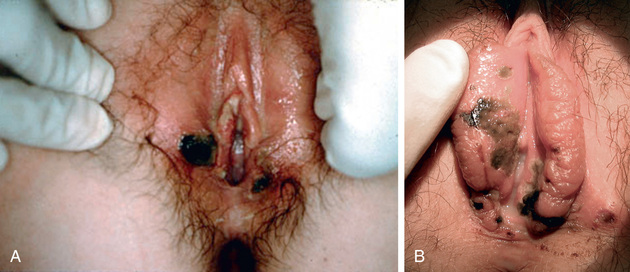

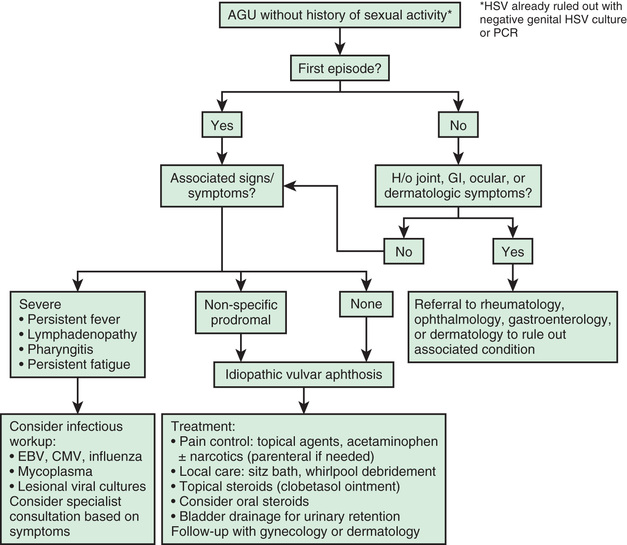

Acute genital ulceration of the vulva (Fig. 564.2 ) is described in young adolescents who are not sexually active and can occur in association with oral aphthous ulcers. Although initially linked to infectious causes such as Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, mycoplasma, mumps, and influenza A, these ulcers may also be idiopathic vulvar aphthoses. Other potential etiologies include inflammatory bowel disease, Behçet disease, pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug eruption, or mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage (MAGIC) syndrome.

These lesions usually appear on the mucosal surfaces of the introitus as painful red or white lesions that evolve into sharply demarcated red-rimmed ulcers with a necrotic or eschar-like base. The time course is generally 10-14 days until remission occurs. The lesions are quite painful, and pain management and urinary diversion with a Foley catheter may be necessary. Patients with acute genital ulcers show a fairly consistent picture of flu-like prodromal symptoms, including fever, nausea, and abdominal pain. Dysuria and vulvar pain are common complaints as well. One third of patients present with a history of or develop oral ulcerations. Evaluation includes culture for herpes simplex virus to exclude this etiology. Special testing for systemic disease depends on the history. Biopsies are usually nondiagnostic because they yield acute and chronic inflammatory changes. Fig. 564.3 outlines the suggested evaluation and management of initial and recurrent disease. Evaluation for Behçet disease (see Chapter 186 ) using the International Study Group diagnostic guidelines should be considered with recurrent or severe cases (see Table 564.1 for other common etiologies). Treatment of acute genital ulcers should include topical Xylocaine 2% jelly, sitz baths, good hygiene, and acetaminophen. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug avoidance is suggested because of a possible causative link. Hospitalization may be required for pain management not controlled with oral narcotics or urinary retention requiring Foley catheterization, or if whirlpool debridement should hygiene become difficult. Antibiotic treatment is not required, unless evidence of bacterial superinfection exists or the patient is immunocompromised. Insufficient evidence exists to recommend whether oral steroid treatment is effective but may be helpful in the setting of recurrent outbreaks and extensive disease. Ultrapotent topical steroids (clobetasol 0.05% ointment) are beneficial in oral aphthous ulcers and may prove helpful in acute genital ulcers as well.

Dermatoses

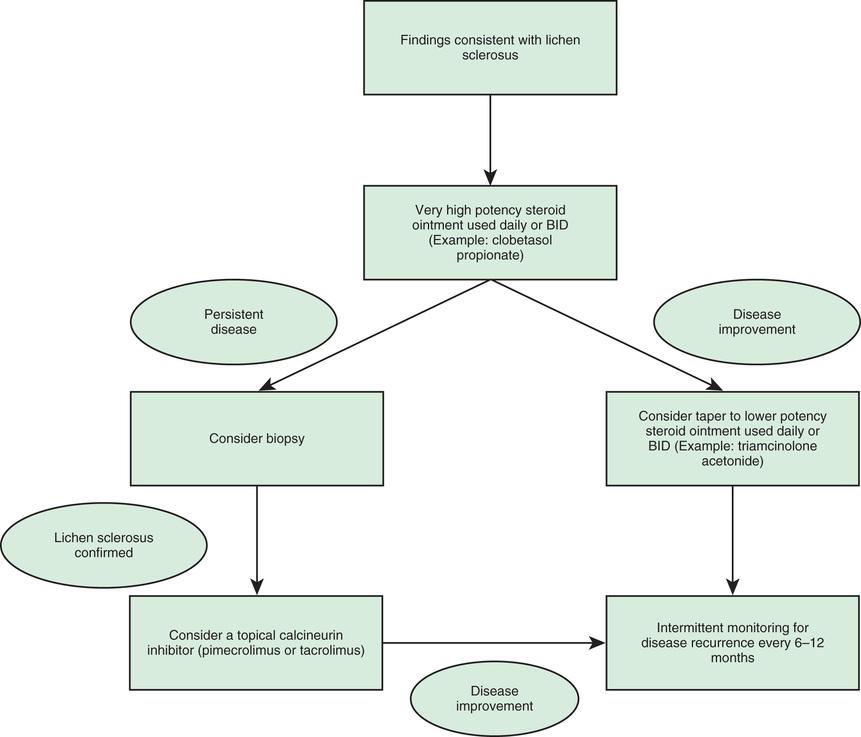

Dermatologic conditions often affect the vulvar area in children; it is important to determine if the girl presenting with vulvar irritation has a skin condition elsewhere on the body. Lichen sclerosus is commonly seen in the anogenital region and has a characteristic appearance of white skin changes associated with areas of erosion, ulceration, and petechiae. This disease can cause severe discomfort and most commonly presents with vulvar or perianal pruritus, dysuria, and constipation. Patients may also present without any symptoms, which may lead to underrecognition and undertreatment. If untreated, lichen sclerosus can lead to destruction and scarring of normal genital architecture, including labial resorption, obliteration of the clitoris, narrowing of the introitus, and painful fissures that may become secondarily infected. Once thought to resolve with puberty, this theory is now controversial, and many postmenarchal adolescents still suffer from disease (Fig. 564.4 ). Lichen sclerosis may be treated with potent topical steroids, such as clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once or twice daily until the symptoms resolve, and then tapered down through lower-dose topical steroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have been used in the treatment of lichen sclerosis. Patients should be followed every 6-12 mo to evaluate for recurrence (Fig. 564.5 ).

Vitiligo is an acquired skin depigmentation resulting from an autoimmune process directed at epidermal melanocytes. Lesions appear as sharply demarcated patches of pigment loss, often symmetrically located around the vagina and anal area. Similar lesions of hypopigmentation can be found surrounding body orifices and extensor surfaces (Fig. 564.6 ). Although the diagnosis is clinical, there is an association with other autoimmune or endocrine disorders (hypothyroidism, Graves disease, Addison disease, pernicious anemia, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) and the workup should include evaluation for at least thyroid dysfunction. Mild topical corticosteroid cream or ointment may be prescribed for children. Dermatologists may offer immunomodulators (tacrolimus) and phototherapy.

Vulvar psoriasis presents as pruritic, well-demarcated, erythematous, symmetric plaques that involve the vulva, perineum, and/or gluteal folds. Lesions on the mons pubis may have the more characteristic scaly appearance. The classic signs of psoriasis may also be appreciated with pitting nail beds, posterior auricular erythema, or a silvery scaling rash found elsewhere on the body. Many of the treatments used in adults may not be appropriate in children. Psoriasis may be treated with moisturizers, topical steroids, and light therapy. Teens may be treated with coal tar, retinoids, tacrolimus, and calcipotriene, which is a derivative of vitamin D3 .

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Children with symptoms of vulvovaginitis often have had previous evaluations and treatment failures. Cultures with sensitivities to test for specific pathogens may be obtained with cotton swabs or urethral (Calgiswab) swabs moistened with nonbacteriostatic saline. Use of a swab can cause discomfort or, rarely, minimal bleeding. The premoistened swab can be placed vertically between the labia minora to collect secretions, as it is not necessary to place the swab into the vagina. Testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia may be done by culture or by nucleic acid amplification testing, depending on institutional or state and Centers for Disease Control guidelines. Tests for Shigella and H. influenzae might require special media and collection procedures.

If pinworms (see Chapter 320 ) are suspected, transparent adhesive tape or an anal swab should be applied to the anal region in the morning before defecation or bathing and then placed on a slide. Eggs seen on microscopic examination confirm the diagnosis, and sometimes the pinworms can be seen at the anal verge. Clinical history is often more indicative of disease than physical exam, and a negative tape test does not rule out this pathogen as a cause.

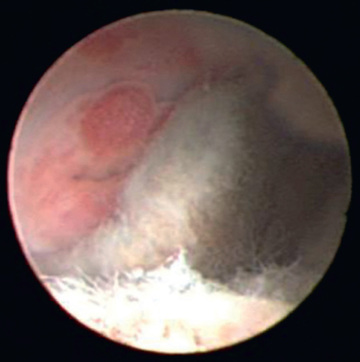

If the vaginal discharge is serosanguineous, if a foul odor is present, or if the discharge fails to respond to hygiene measures, consider presence of a vaginal foreign body (Fig. 564.7 ). If inspection suggests the presence of a foreign body, the vagina can be irrigated, or an examination under anesthesia may reveal the foreign body. Vaginal irrigation may occasionally lead to expulsion of the foreign body; in cases where this does not occur, vaginoscopy is an excellent diagnostic tool and can be performed in an unsedated cooperative patient in an outpatient setting, or under general anesthesia if necessary. Using a cystoscope with saline or water irrigation to gravity, insert the endoscopic device into the vagina, gently oppose the labia, the vagina will distend, and the entire vaginal cavity and cervix may be easily assessed.

Treatment and Prevention

The treatment of specific vulvovaginitis should be directed at the organism causing the symptoms (see Table 564.1 ). Treatment of nonspecific vulvovaginitis includes sitz baths and avoidance of irritating or harsh soaps and chemicals and tight clothing that abrades the perineum. External application of bland emollient barriers such as nonprescription diaper rash medications and petroleum jelly may be helpful. Proper perineal hygiene is critical for long-term improvement. Younger children need supervised perineal hygiene, and caregivers should be advised to wipe the genital area from front to back. Use of a warm moistened washcloth or diaper wipe is helpful after initially wiping with toilet tissue. Girls should wear cotton underwear and limit time spent in tights, leotards, jeggings, tight jeans, and wet swimsuits. Soaking in warm clean bathwater for 15-min intervals (no shampoo or bubble bath) is soothing and helps with cleaning the area. Parents should be counseled to avoid all scented, antiseptic, and deodorant-based soaps, and to eliminate the use of fabric softeners or dryer sheets when laundering undergarments.