The specific sources of the reported, recorded, and observed data utilized in making this volume are described in the present chapter. The use that we have made of the previously published studies on human sexual behavior is also described. Since the data reported in our series of case histories constitute an important part of this volume, the nature of those data is described in some detail in this chapter, and critical tests of the reliability and validity of the case history data are also presented here.

All of the case histories in this study have been obtained through personal interviews conducted by our staff and chiefly by four of us during the period covered by this project. We have elected to use personal interviews rather than questionnaires because we believe that face-to-face interviews are better adapted for obtaining such personal and confidential material as may appear in a sex history. 1

Establishing Rapport . We believe that much of the quality of the data presented in the present volume is a product of the rapport which we have been able to establish in these personal interviews. Most of the subjects of this study—whatever their original intentions in regard to distorting or withholding information, and whatever their original embarrassment at the idea of contributing a history—have helped make the interviews fact-finding sessions in which the interviewer and the subject have found equal satisfaction in exploring the accumulated record as far as memory would allow. Persons with many different sorts of backgrounds have cooperated in this fashion. Females have agreed to serve as subjects and, on the whole, have contributed as readily and as honestly (p. 73, Tables 3 –8 ) as the males who were the subjects of our previous volume. Apart from rephrasing a few questions to allow for the anatomic and physiologic differences between the sexes, we have covered the same subject matter and utilized essentially the same methodology in interviewing females and males. 2

Objectivity of the Investigator . In the course of our interviewing, we have constantly reassured our subjects that the interviewer was not passing judgment on any type of sexual activity, and that he was not interested in redirecting the subject’s behavior. This has been explained in so many words at the beginning of each interview, but much of the reassurance has depended on the ease and objective manner of the interviewer, on the simple directness of his questions, on his failure to show any emotional objection to any part of the record, on his tone of voice, on his calm and steady eye, on his continued pursuit of the routine questioning, and on his evident interest in discovering what each type of experience may have meant to each subject. These things can be done in a face-to-face interview; they cannot be done as effectively on a questionnaire.

Confidence of the Record . In the interviews we have had the opportunity to convince the subjects that all of our records are kept confidential, that only four persons on our staff can read the code in which each history is recorded, that none of the staff has access to the files except the persons who have taken histories, that all of the histories are kept in locked and fireproof files in our laboratories at Indiana University, that no one except the interviewers ever prepares the data for subsequent analyses, that no part of the history is ever translated into words, that the data are placed directly onto punch cards by the same interviewing staff, that no individual history is ever discussed outside of the interviewing staff, and that no history will ever be published as an individual unit.

Recording the data in code in the presence of the subject has done a good deal to convince him or her of the confidence of the record. Even though anonymity is ordinarily guaranteed by the statement which caps most questionnaires, many persons still fear that there may be some means by which they can be identified if they write out answers to printed questions. They fear, and not without some justification in the history of such studies, that a record made in plain English may be read by other persons who obtain access to the file. It is not to be forgotten that our sex laws and public opinion are so far out of accord with common and everyday patterns of sexual behavior that many persons might become involved in social or legal difficulties if their sexual histories became publicly known.

Flexibility in Form of Question . While the point of each question has been precisely defined throughout the history of the project, the wording of each question has been adapted to the vocabulary and experience of each subject. The study has included persons who were poorly educated and sometimes illiterate, technically trained medical and psychiatric groups, children of the age of two and adults as old as ninety, religiously devout and underworld groups, and persons with highly diverse sexual histories. We have constantly had to define terms and explain exactly what we have intended by our questions, for technically trained as well as for poorly educated subjects. This would not have been possible in a questionnaire study.

It is a mistake to believe that standard questions fed through diverse human machines can bring standard answers. The professionally trained subject may be offended at the use of anything but a precisely technical vocabulary for the anatomy and physiology of sex, but the poorly educated individual may have no sexual vocabulary beyond the four-letter English vernacular. Even the most technically trained person may not catch the meaning of some particular question, although it is phrased in a form that has proved effective for most of the others who have been interviewed. 3

Vocabularies differ in different parts of the United States and there are differences among individuals belonging to different generations. Sexual vocabularies may differ among persons in different portions of a single city, depending upon their social levels, occupational backgrounds, racial origins, religious and educational backgrounds, and still other factors. In each community, we have had to discover the meanings that were being attached to particular terms, and learn which terms might be used without giving offense. In order to establish rapport one has to learn to use the local vocabulary with an ease and a skill that convinces the subject that we know something of the custom and mode of living in his or her type of community, and might be expected, therefore, to understand the viewpoint of such a community on matters of sex.

For instance, one has to learn that a person in a lower level community may live common-law, although he does not enter into a common-law marriage with a common-law wife. As we have noted in our volume on the male (1948:52), we have had to learn that a lower level individual is never ill or injured although he may be sick or hurt; he may not wish to do a thing although he may want to do it; he does not perceive although he may see; he may not be acquainted with a person although he may know him. Syphilis may be rare in such a community, although bad blood may be more common. At such a level an individual may not yet have learned about a particular type of sexual activity although he may have heard about it and even observed it many times; but he considers that he does not know about it until he has had experience. Such an individual does not understand our question about seeing a burlesque although he can tell you about the burlesque show which he saw. The existence of prostitutes in the community may be denied, although it may be common knowledge that there are some females and males who are hustling. Inquiries about the frequency with which a prostitute robs her clients may not bring any admission that such a thing ever happens, although she may admit that she rolls some of her tricks. But the use of such terms with an upper level subject would leave him mystified or offended. At every level, inquiries about the circulation of pornographic literature might elicit very little information, although most teen-age boys may have seen eight-pagers. The adaptation of one’s vocabulary in an interview thus not only contributes to the establishment of rapport, but brings out information which would be completely missed on a standardized questionnaire.

An interview may be restricted to the areas in which the subject has had sexual experience. By feeling his way, the interviewer may discover the limits of that experience, and not ask questions beyond that point. If the subject has not had masturbatory, or coital, or homosexual experience, questions concerning the detailed techniques of those activities are simply passed by. Thus it has been possible to interview children and inexperienced older individuals without mystifying or wearying them, or shocking them by discussing types of sexual activity about which they have had no previous information. But a questionnaire must cover all of the activities which the most experienced adult may have had, and there would be a variety of objections to undertaking such an exposition of all of the possibilities of human sexual behavior in the course of a single interview.

Consistency of Data . In a personal interview, the interviewer may check, on the spot, the consistency of the material covered in the history. He and the subject may then adjust, correct, and iron out contradictions which may have developed in the record. On occasion, the subject may have deliberately distorted the report; in other instances the subject’s memory may have failed; but answers which develop later in the interview may allow the interviewer to return to the original statement and straighten out the inconsistencies, with the subject’s help and without offending the subject by impugning his or her veracity. This would be difficult or impossible in most questionnaire studies.

Moreover, it has been possible for the interviewer to see that each and every item on the coded sheet was answered by the subject. The frequent failure to secure all of the answers on a questionnaire is a prime source of statistical difficulty which usually cannot be corrected after a subject has turned in a written record.

Determining the Quality of the Response . In a face-to-face interview, the interviewer has an opportunity to check the honesty, the certainty, and the exact meaning of the subject’s reply. The speed of the subject’s response, his tone of voice, the direction of his eye, the intonation and the directness or circumlocution of his statement, often provide a clue to the quality of the information which he is giving. When the subject seems uncertain in his reply, the interviewer may ask for additional information, sometimes on matters which are not covered by the standard interview. This may direct the inquiry toward important data which would have been overlooked if the interview had been confined to the minimum material. There are few such bases for determining the quality of the replies on a questionnaire, and little opportunity for extending the data beyond the set limits of a questionnaire.

Time Involved in Interview . The average interview of an adult contributing to the present study has required something between one and a half and two hours. When the subject had had more limited experience, as is frequently true of teen-age girls, the interviewing may have been accomplished in an hour or less; but when subjects had had more extensive experience the interviews have often extended beyond the two hours. Something over 300 questions have been minimum on the average history, but in special instances—where there had been extensive pre-marital or extra-marital experience, extensive homosexual experience, elaborate techniques in masturbation, coitus, or other types of sexual activity—the interviews have sometimes extended to 500 or more questions. It is doubtful whether it would have been possible to persuade many persons to give so much time to a questionnaire; and the quality of the answers on such a long questionnaire would probably have been lower.

The problem involved in a two-hour interview which covers 300 to 500 questions, many of which concern highly confidential material, is very different from the problem which is involved in most public opinion polls, and in most market, government, and other surveys which have utilized questionnaires. The claims made for the efficiency of the questionnaire have, to a large extent, been based upon studies that have covered relatively few questions and required relatively little time from each subject. Moreover, comparisons of questionnaire and interview techniques have usually been made on studies which dealt with subjects less sensitive than sexual behavior. 4

It is possible that the quality of the data obtained in interview studies may be more variable than the quality of the data secured from questionnaire studies, because the effectiveness of an interview so largely depends on the ability and experience of the interviewer and on the quality of his interviewing. In our own study, the interviewing has been limited to a very small number of carefully trained and professionally equipped, full-time associates on the project. On the other hand, public opinion and market and government surveys which must be carried on and completed in a minimum period of time often have to utilize large corps of part-time interviewers, most of whom cannot be trained to do much more than locate the subjects of the study and deliver a set schedule which they wish to have answered. This has been a prime reason for the conclusion that questions on an interview should be strictly standardized and administered via a questionnaire which is filled out by the subject or by the interviewer.

The items covered in our interviewing were listed in our previous volume on the male (1948: 63–70). The histories obtained through the interviews provided most of the data which were statistically tabulated and correlated in that volume, and which we present now in this volume on the female. Specifically, the following statistics have been drawn from the data reported on the histories:

Accumulative Incidence . These show the number of females and males, in terms of the percentages of the total sample, who had ever, by a given age, had experience or reached orgasm in the various types of sexual activity. The data cover the pre-adolescent sex play, masturbation, nocturnal dreams, heterosexual petting, pre-marital coitus, marital coitus, extra-marital coitus, post-marital coitus, homosexual contacts, and animal contacts of each of the subjects in the study. See pages 46–47 for a further discussion.

The case histories have also provided accumulative incidence data showing the ages at which the subjects first acquired information concerning various aspects of sex, the ages of first erotic arousal, the ages at marriage, the techniques utilized in the various types of sexual activity, the nature and number of the partners in the socio-sexual contacts, the subject’s attitudes toward particular types of sexual activity, and still other matters which are detailed later in this chapter.

Active Incidence . The case history data have made it possible to calculate the active incidences of the subjects—in terms of the percentages of the total sample—who were engaging in each type of sexual activity in each of the five-year age periods covered by the histories. See page 47 for a further discussion.

Frequency of Activity . The case history data have shown the frequencies with which each subject had engaged in each type of activity in each five-year period of his or her history. All frequencies have been calculated as average frequencies per week. See pages 47–48 for a further discussion.

Number of Years Involved . The case histories have shown the number of years during which each subject was involved in each type of sexual activity. At several points we have also obtained data on the continuity or discontinuity of certain types of sexual activity, noting those that had ordinarily occurred with some regularity and those which had occurred sporadically. We have stressed this point in the present volume, because sexual activities among females prove to be discontinuous more often than they are among males.

Techniques . Data on the incidences of the techniques used in the female’s sexual activities have also been obtained from the case histories. The data have covered:

Masturbation: 12 items of technique

Heterosexual petting (pre-marital, marital, or extra-marital): 10 items of technique

Heterosexual coitus (pre-marital, marital, or extra-marital): 18 items of technique

Homosexual contacts: 24 items of technique

Animal contacts: 4 items of technique

Partners . Where there had been socio-sexual contacts, the case histories have shown the number and ages of the partners involved and, in the more extensive histories, the subject’s preferences for particular types of partners, the way in which the partners first met, the marital status of each partner, the partner’s occupational classification, and the frequencies of contact.

Motivations and Attitudes . In each interview there has been an attempt to identify the first sources of the subject’s sexual knowledge, the factors that were originally responsible for the subject’s involvement in each type of sexual activity, and the factors (such as erotic satisfactions) which were responsible for the continuation of the activity.

The subject’s evaluation of his or her sexual experience, his or her intention to have or not to have additional experience, and his or her social and moral judgments of masturbation, pre-marital coitus, extramarital coitus, and homosexual activities, have also been recorded, and are analyzed in the present volume.

Correlations with Biologic and Social Backgrounds . In each case history, we have obtained data on factors which might have affected the individual’s choice of a pattern of sexual behavior, such as his or her age, marital status, educational level, parental occupational class, decade of birth, age at onset of adolescence, rural or urban background, religious background, and still other factors. See pages 53 to 56 for a further discussion.

Psychologic and Social Significance . In the interviewing, considerable information has been obtained on the psychologic and social significance of each type of sexual activity for the subject of each case history. Specific data have been secured on items of such obvious social concern as pregnancies consequent on pre-marital coitus, the effects of pre-adolescent sexual experience with adults, and the social and legal difficulties in which the subject may have become involved as a consequence of his or her sexual behavior. We have correlated the record on pre-marital sexual experience with the record of orgasm in the subsequent marital coitus. We have made special analyses of married couples, unmarried females, older females, females with homosexual histories, and still other special groups.

Much of the discussion of the social significance of each type of sexual activity has, however, been drawn from recorded and observed data, rather than from the case histories. These other sources of data are discussed below (pp. 83–92).

We are, of course, interested in knowing how far the events reported in an interview may represent an accurate account of what actually happened to the subject who has given the report. The record may be affected by: (1) a simple failure to recall, at the moment, events that should have been made a part of the record; (2) more specific errors (distortions) of memory; (3) some failure to comprehend the nature of the events when they originally took place; (4) emotional blockages which interfere with the subject’s ability to make an objective report; (5) deliberate cover-up or misrepresentation of the fact; and (6) some deliberate exaggeration of the fact. There are some events that are less liable to these errors than some others on a sex history.

This problem of the reliability and validity of reported behavior is not unique to this study or even to case history studies in general. It is a problem which we all face in evaluating the statements made by our friends, the reports published in newspapers and magazines, and all other sources of information which does not come from our own direct observations. If we were to accept the extreme skepticism which some persons profess, we should rate all reports as worthless, and not be too certain that our own eyes do not deceive us. Obviously, we do not actually do this in our everyday lives, and we do not actually do this with a scientific report. What we do do is to try to find some means for determining the degree of reliability and the level of the validity of the reported data. We have learned to accept reports from persons who are reliable and sincere in their attempts to confine themselves to valid statements. We arrive at some opinion concerning the general reliability or unreliability of each of the local newspapers. We try to find out what experience lies back of the journalist who writes the magazine article, and we want to know how capable and cautious he may have been in separating well established data from mere gossip and emotionally biased interpretations. In a scientific study we attempt to develop a variety of tests to determine the reliability and validity of the reported and observed data.

By the reliability of a subject or of a report, we refer to the interlocking consistencies of the data, and the consistency with which the subject gives the same report on successive occasions. In our present study, we have given especial attention to the internal consistencies of the data which we get on each history, and before the end of an interview we requestion the subject in order to straighten out any apparent inconsistencies. We have further tested reliability by securing retakes of histories from subjects who had previously given us histories. Comparisons of the data secured from the original histories and the retakes are described on pages 68 to 74.

By validity , we refer to the conformance of the reported data with the event that actually occurred. The best test of validity would be a comparison of the report with recorded data made by qualified observers or recording machines. Short of that, we may test the validity of reported data by comparing the replies given independently by two or more participants in the same activity. We have, for instance, compared the reported data given us by several hundred pairs of spouses (pp. 74–76). More indirectly, we may test validity by comparing the replies obtained from one group with the replies obtained from a group that might be expected to have had similar sexual histories. For instance, we have compared the coital rates reported by males and the rates reported by females. The testing of the reliability and validity of our data is as yet insufficient, and we shall continue to make such tests as the research program allows; but it may be noted that this is the first time that tests of either reliability or validity have been made in any study of human sexual behavior, and that there are few other case history studies of any sort which have made as extensive tests as we have undertaken in the present study.

Retakes . Comparisons of the data secured in an original interview and the data secured from the same person at some subsequent date may test the reliability (the consistency) of the reports. In general, the test is more severe if an appreciable period of time has elapsed between the first and second interviews, for it then becomes more difficult to duplicate distortions which may have been accidentally, capriciously, or calculatedly introduced into the original record. If answers have been capricious, without a basis in fact, it becomes increasingly improbable that an exact duplicate could be produced after any considerable lapse of time. This is particularly likely to be true in the present study, where hundreds of details are covered on each history.

We have, in consequence, spent some time securing retakes from a series of subjects who had previously contributed their histories. In our previous volume we were able to report on 162 of these retakes, including both females and males. We can now report on 319 retakes, including 124 females and 195 males. We shall continue to accumulate such material as the total program allows, for we need to compare the reliability of the data which we secure from persons of various ages, various social levels, and various other groups.

While retakes do not provide a test of the validity of a report—the extent to which the reported behavior conforms with the event as it actually occurred—consistencies in answers on long-time retakes do suggest that they may have had some basis in fact.

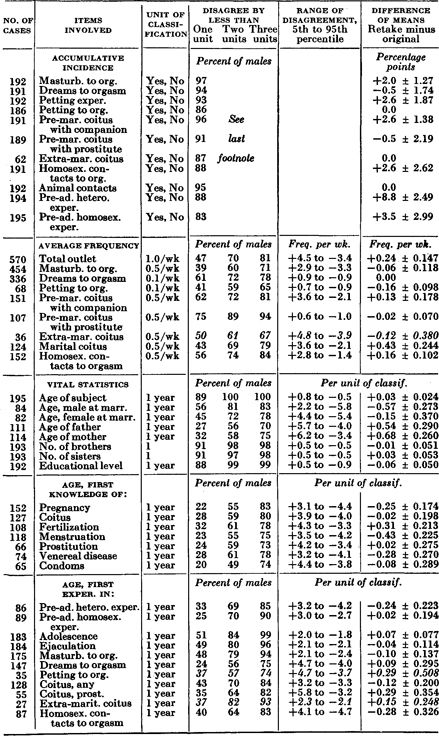

With few exceptions, our retakes have been made only after a minimum lapse of 18 months. For some years we have demanded a minimum lapse of at least two years. The median lapse of time between the original histories and retakes reported in the present volume has been 35 months for the males, and 33 months for the females. In a number of instances, the retakes have not been made until 10 or 12 years after the original histories were obtained. This constitutes an extreme test of the capacity of an individual to reproduce the considerable detail which is involved in the more than 300 questions that have been covered on each history. Comparisons of the data secured on this series of original histories, and the data secured on the corresponding histories in the series of retakes (Tables 3 and 4 ), show the following:

In regard to the accumulative incidence data (the question of whether an individual has ever been involved in a particular type of activity), the number of identical replies on the original histories and the retakes ranges from 77 per cent on one of the items, to 97 per cent on two of the other items (Tables 3 , 4 , column 4). For most of the items, the incidences calculated on the whole group of retakes are not materially different from the incidences calculated on the original group of histories (Tables 3 , 4 , last column). On fourteen of the items, they are modified by something less than 3 per cent (of a possible 100 per cent) and on three more the modification amounts to something between 3 and 4 per cent. The modification amounts to more than that on only four items. It is most extreme (9 to 10 per cent) for the incidence of pre-adolescent heterosexual play among females and among males, and for the incidence of pre-adolescent homosexual play among females. The greater discrepancies on these latter items are probably due to errors of memory concerning such early events, and to some difficulty in identifying pre-adolescent play as sexual; they are less likely to be due to deliberate cover-up.

The differences between the means computed for the whole group of original histories, and for the whole group of retakes, are actually small in terms of the units of measurement (Tables 3 , 4 , column 2), and in most instances less than might have been expected from an examination of the percents of identical replies. This means that the discrepancies between the first and second reports do not lie in one direction more often than the other, and that the differences on the individual histories are to some extent ironed out in computing averages.

For the adult female activities, the retakes modify the incidences calculated on the original histories by less than 2 per cent (of a possible 100 per cent) in the case of masturbation, petting experience, petting to orgasm, pre-marital coitus, and homosexual experience (Tables 3 , 4 ). They modify the incidences by something between 3 and 4 per cent in the case of nocturnal dreams which go to the point of orgasm, and in the case of extra-marital coitus. They modify the incidence of petting to the point of orgasm by nearly 6 per cent. For adult males, there is no activity for which the retakes modify the incidences calculated on the original histories by as much as 3 per cent, and in regard to five of the types of activity (nocturnal dreams to orgasm, petting to climax, coitus with prostitutes, extra-marital coitus, and animal contacts), they modify the incidences originally calculated by something less than 1 per cent.

It is to be noted that in regard to most types of activity both among females and males, the retakes raise the incidences calculated on the original histories. This confirms the impression we have acquired in the course of our interviewing, that the incidence data may be taken as minimum records, rather than exaggerations of the fact.

There were surprisingly few differences in the mean ages reported on the original histories and on the retakes for various items: for the ages involved in the vital statistics, for the ages at which the subjects had first acquired their knowledge of various sexual items, and for the ages at which they had first had experience in the various types of sexual activity. In 53 out of the 54 items (female plus male) covered in these calculations, the mean ages calculated on the original histories were modified by less than one year, and on 40 out of the 54 the modification would have amounted to less than four months (0.33 years). On 18 items, the retakes did not modify the means obtained on the original histories by more than one month. If one notes again that three years had, on the average, elapsed between the original histories and the retakes and, in some instances, there had been lapses of ten to twelve years, this high level of reliability is especially remarkable.

In general, the incidence data are more reliable than the frequency data. One may be expected to recall with considerable accuracy whether he has ever masturbated to orgasm, had pre-marital coitus, or been brought to orgasm in a homosexual relationship—although deliberate distortions may sometimes enter into such reports of incidence. Frequencies are more difficult to report with accuracy because most persons are inexperienced in averaging any sort of activity which occurs sporadically. Moreover, in an interview in a sex study the subject is asked to estimate averages for events that may have occurred in the long-distant past (see also our 1948: 124–125).

Table 4. Comparisons of Data Reported on Original Histories and Retakes of 195 Males

The footnotes for Table 3 also apply to this table.

In the original sample, the accumulative incidences for the items in this part of the table, in the sequence given here (from “Masturb. to org.” to “Pre-ad. homosex. exper.”), were as follows: 94, 89, 91, 39, 59, 34, 55, 51, 10, 51, and 59 per cent, respectively.

In connection with the frequencies of sexual activity, on 7 out of the 9 items reported by the females and on 8 out of the 9 items reported by the males, fewer than 70 per cent of the subjects had given identical replies (within the limits of the units designated in Tables 3 , 4 ). For a number of the items less than half of the subjects had given identical replies. Moreover, something between 6 and 37 per cent of the subjects failed to give replies that lay within even two units of identity.

However, the utility of the frequency data appears to increase when we deal with the average frequencies for the whole group of subjects. The differences between the mean frequencies calculated for the original histories and the mean frequencies calculated for the retakes would amount to something less than one experience in five weeks for almost any type of activity, and to less than one experience in ten weeks for most of them.

Comparisons of the data presented in Tables 3 and 4 fail to show consistent differences in the reliability of the record secured from females and that secured from males. Females do not seem to have been more inclined, as some persons have suggested they might be, to distort the record on the material covered by the present study. In regard to the 45 items which the female and male histories have in common., the females gave identical replies more often than the males in 23 instances, identical replies as often as the males in 4 instances, and identical replies less often than the males in 18 instances. Comparisons of replies that were identical within one and within two units show about the same proportions of concurrence between the female and male replies. A further examination of Tables 3 and 4 shows that the reliability of the data on the specifically sexual items is as high as the reliability of the data on such non-sexual items as those covered by the vital statistics, and this seems remarkable.

It may be added that the reliability of the data which we have studied from our series of retakes is, with the exception of the frequency data, not particularly different from the reliability of reports obtained in other surveys which have dealt with much less personal and much less emotional material than human sexual behavior. One might have anticipated a higher level of unreliability in a sex study. Even if one makes allowances of the sort indicated above, our generalizations concerning the nature of the sexual behavior of our female and male samples will still not be modified in any material respect, with the possible exception of some of the generalizations based on the frequency data.

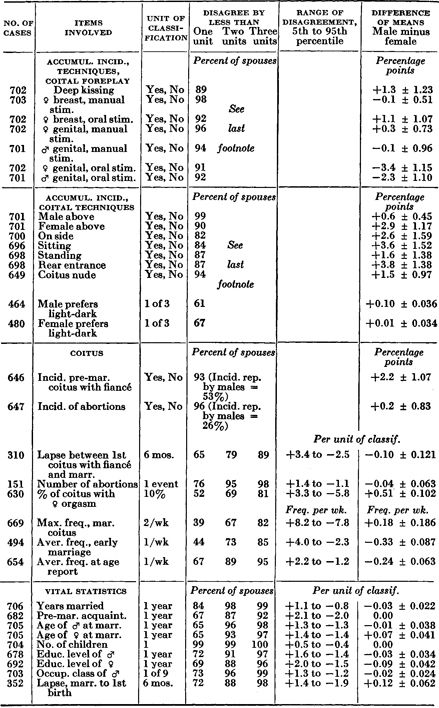

Table 5. Comparisons of Data Reported by 706 Paired Spouses

Table is based on all available paired spouses, including both white and Negro, and both prison and non-prison histories.

Because average frequencies of coitus are not well established in the first year of marriage, data from marriages which had extended for less than one year were not used in this table. Since the maximum frequencies reached in any week are usually attained early in the marriage, one-year marriages were included in the calculations on that point. In order to test recall that covered some years, the “average frequencies in early marriage” were based on marriages which had extended for at least three years.

Comparisons have been possible only for events occurring prior to the interview with the first spouse in each pair.

The N’s vary for the different items because: (1) comparisons could not be made when a given question had not been asked, or had not been asked in sufficient detail, of either spouse; (2) a few of the questions did not apply to the experience of a particular female or male.

In the male sample, the accumulative incidences for the items in the first part of the table, in the sequence given here (“Deep kissing” to “ genital, oral stim.”), were as follows: 89, 99, 93, 97, 93, 54, and 52 per cent, respectively.

genital, oral stim.”), were as follows: 89, 99, 93, 97, 93, 54, and 52 per cent, respectively.

In the male sample, the accumulative incidences for the first six items in the second part of the table, in the sequence given here (“Male above” to “Rear entrance”), were as follows: 99, 83, 70, 41, 26, and 49 per cent, respectively.

Comparisons of Spouses . While comparisons of original histories and retakes provide some test of the consistency of reporting, a comparison of the data provided by the two spouses in a marriage, or by the sexual partners in any other type of relationship, may provide a test of the conformance between the reported data and the actual event-i.e. , the validity of the report. Even such a test, however, falls short of being a final test of validity, for there may have been some prior agreement between the sexual partners to distort their reports, or both of them may have had the same reason for consciously or subconsciously distorting the fact. Nevertheless, such comparisons provide information of some value in attempting to assess the quality of reported data.

In our previous volume we compared the responses received from 231 pairs of spouses. We now have the histories of 706 pairs of spouses (1412 individual spouses) which we have compared in regard to 33 items (Table 5 ). These items include certain of the vital statistics, data concerning coital relations in marriage, the incidences of various techniques in the pre-coital foreplay, and the incidences of various coital positions.

The number of identical replies ranges from 39 per cent on one item (the maximum frequency of coitus in any single week of the marriage) to 99 per cent on another (the use of the male superior position in coitus). On 12 of the items, identical replies were received from 90 per cent or more of the pairs of spouses. On 18 out of the 33 items, identical replies were received from 80 per cent or more of the pairs of spouses.

Replies that were identical within a single unit were received from 90 per cent or more of the pairs of spouses, on 7 out of the 15 items on which such measurements could be made. Replies that were identical within two units were received from 90 per cent or more of the pairs of spouses on 11 out of the 15 items.

More important than the percentages of identical or near identical replies are the magnitudes of the differences between the means calculated for the female spouses, and the means calculated for the corresponding male spouses. With one exception the means of the replies of the female spouses on various items of the vital statistics do not differ from the means of the replies of the male spouses by as much as 10 per cent of the unit of measurement—e.g. , by one-tenth of a year. The incidences of the various techniques used in the pre-coital foreplay, and of the positions and other techniques of the actual coitus as reported by the female and male spouses, never differ by more than 4 percentage points on any item; and on 7 out of the 14 items they differ by only 1 percentage point or less.

This means that the disagreements that do appear in the replies received from the paired spouses do not lie predominantly in a single direction. This is even true for the frequencies of the marital coitus, where we previously (1948: 127–128) found a tendency for the male to underrate the frequencies, and a tendency for the female to exaggerate the frequencies. The differences which we now find in our more than 700 pairs of spouses do lie in that direction, but they do not amount to more than one coital contact in three to five weeks.

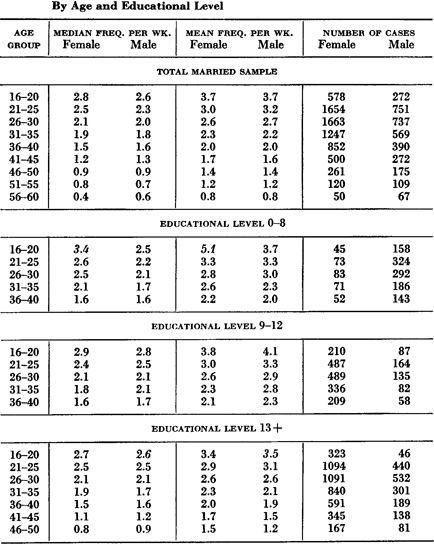

Conformance of Female and Male Reports on Marital Coitus . Heterosexual coitus should, of course, involve females as frequently as it involves males. If the male and female samples are comparable, whether they are actually representative of the total population or not, and if the replies received from females and males are equally adequate, then the frequencies of marital coitus reported by each group of married females should be identical with the frequencies of marital coitus reported by the corresponding group of married males. The degree of conformance of the data which we have from our samples of married females and males should, therefore, provide a test of the quality of each sample, and also some test of the validity of the replies received from the females and from the males.

Table 6. Comparisons of Frequencies of Marital Coitus as Reported by Females and Males

Table based on total sample of white, non-prison females, and on total white male sample including prison and non-prison groups. It is based on the male sample rather than the “U. S. Corrections” reported in our 1948 volume, in order to secure a more comparable educational distribution of the females and males.

An examination of Table 6 will show that there is, in actuality, a remarkable agreement between the frequencies of marital coitus reported by the females of the various age groups and educational levels in the sample, and by the males of the corresponding groups. This is true for both the median and mean frequencies. The discrepancies which do occur are for the most part very minor, and they do not lie in any single direction. Evidently the constitution of the married female sample closely parallels that of the married male sample; and there would seem to be considerable validity in the replies received from females and males.

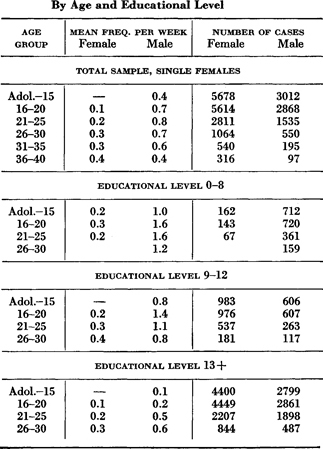

Table 7. Comparisons of Frequencies of Pre-Marital Coitus as Reported by Females and Males

Non-conformance of Female and Male Reports on Pre-Marital Coitus . In contrast to the foregoing, comparisons of the frequency data for pre-marital coitus reported by the females and males in the sample show discrepancies of considerable magnitude (Table 7 ). Quite consistently in every educational level and for every age group the males reported incidences and frequencies which were higher and in some cases considerably higher than those reported by the females. At this point we are not certain what factors are primarily responsible for these differences, but some of the following may be involved:

1. The discrepancies between the reports on pre-marital coitus by the females and the males are least for the college group and maximum for the grade school group. This suggests that the replies from the college males and females are more valid than the replies from the lower level groups; or it may suggest that the college sample is more representative than the grade school sample.

2. The data given in the/resent volume are based almost wholly on females of the high school, college, and graduate school levels; females from the grade school level are very poorly represented in the calculations. On the other hand, the record given in our volume on the male included a much larger sample of the grade school group and was probably more representative of that group of males.

3. The females may have covered up in reporting their pre-marital experience, or the males may have exaggerated their reports of such experience. It is quite possible that both things may have happened, but it is our judgment that the female record is more often an understatement of the fact.

4. The male sample included a considerable series of males, particularly of the grade school level, who had been involved with the law and had served time in penal institutions. The frequencies of pre-marital coitus in that group were definitely higher than the frequencies of pre-marital coitus among the grade school males who had never served time in penal institutions. In the case of the female, calculations show that the frequencies of pre-marital coitus were similarly higher among those who had served time in penal institutions. The group includes both prostitutes and the sort of promiscuous females who are most often involved in tavern pick-ups and in street approaches. The exclusion of the grade school sample, and particularly of the prison sample, from the male data, or the inclusion of the corresponding group of females in the present volume, would have brought the female and male data on pre-marital coitus closer together. It still would not have accounted for all the differences.

5. Males not infrequently have their pre-marital coitus with girls of social levels which are lower than their own. Consequently, a more adequate sample of lower level females would have accounted for some of the discrepancies among the better educated groups.

6. Males have a portion of their pre-marital coitus with prostitutes; and while we attempted to differentiate the male’s contacts with prostitutes and with girls who were not prostitutes, it is possible that the distinction was not always made. None of the activities which females have had as prostitutes are included in any of the calculations in the present volume.

7. White males of all social levels may have pre-marital and extra-marital coitus with Negro females. White females very rarely have non-marital coitus with Negro males. Some small portion of the discrepancy between our female and male data may be accounted for by the fact that these interracial contacts were included in the male volume but are not accounted for in the present volume, because no Negro females are included in this volume. This correction, however, would account for only a small portion of the discrepancy.

8. Some of the pre-marital coitus recorded in the male volume represented contacts which males had had outside of the United States, chiefly while they were in the armed services during the first and second World Wars and on business trips. Essentially none of these contacts are covered in the present volume.

9. The coital frequencies reported for the males were based upon the frequencies of orgasm, whereas the frequencies shown for the females represent frequencies of experience, whether with or without orgasm. In the case of the males, the calculated frequencies were raised whenever there was multiple orgasm; in the case of the females, multiple orgasm was not included in calculating the frequencies of the coitus. Recalculations on the basis of the frequencies of experience should bring the male data closer to those for the female; but the correction would not account for more than a portion of the discrepancy.

While most of these adjustments are small, their total would bring the female and male data much closer together. It is probable, however, that differences in the representativeness of the female and male samples, and the probability that the females have covered up some portion of their pre-marital coitus, are the two factors that are chiefly involved.

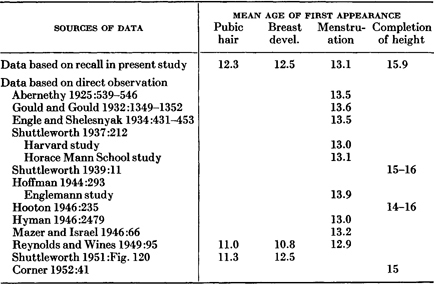

Memory vs. Physical Findings . The best test of validity is one which compares reported data with data obtained by direct observation from comparable samples. Unfortunately such comparisons are unavailable oil most aspects of human sexual behavior. They are available, however, for comparisons of data on the ages at which physical developments first occurred at the onset of adolescence. Table 8 shows that the data which we have obtained by recall are amazingly close to the data which have been obtained by direct observation.

The first development of a physical character might be expected to pass unnoticed by a girl or boy, and recall after a great many years might be expected to be inaccurate on such non-discrete items. It is all the more surprising, therefore, to find that the data obtained by recall are remarkably close to those obtained by observation. The greatest discrepancy (Table 8 ) comes in the recall of the age at which pubic hair first developed. The observations on this character, reported in two studies, give median ages which are about a year earlier than our subjects recalled. Regarding breast development, one of the physical studies indicates earlier development while another study arrives at the very same median age which our females recalled. The median age of first menstruation obtained from the recall was 13.1 years, in comparison with ages ranging on the observational studies from 12.9 to 13.9 years. Four of the observational studies arrived at a median age which differed by only 0.1 years, plus or minus, from the median calculated in our own study. Since menstruation is a more discrete event than some other adolescent developments, it is understandable that this should have been recalled with greater precision by our older subjects. Even the median age of completion of height, which was recorded by our subjects as a bit under 16 years, very closely agrees with the age reported on three of the other studies.

No scientist would be inclined to consider that data obtained by recall were as valid as data obtained from the direct observation of a physical phenomenon; but recall has apparently not served too badly on these particular characters in our case history study.

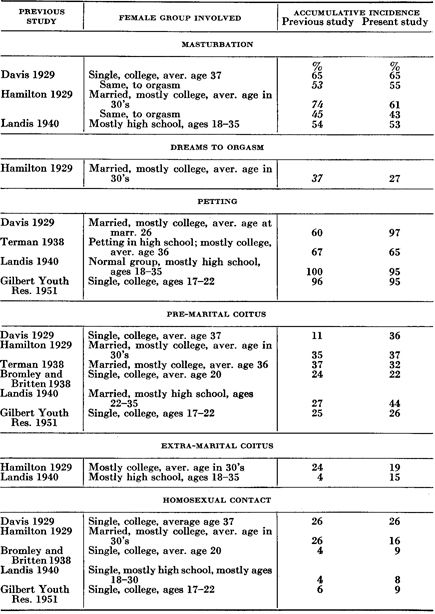

Comparisons of Data in Present and Previous Studies . Conformance of the data obtained in two or more independent studies may suggest that there is some validity in the findings, or it may suggest that all of the studies have been affected by the same sources of error. Certainly both explanations are possible, but there is a strong presumption, both among scientists in their experimental work and among most people as they meet their everyday problems, to see some significance in conformant experience.

Table 8. Comparisons of Memory and Observation as Sources of Data on Physical Development of the Female in Adolescence

For what it is worth, then, it may be recorded that our findings on incidences, on ages of first experience, in some instances on frequencies, on the number of years involved in given types of activity, on the number of partners involved, and on still other aspects of human sexual behavior, are in striking accord with the findings in those relatively few other studies which have made statistical analyses of data systematically collected from samples of any size (Table 9 ). Even some of our findings which are most likely to surprise the readers of the present volume, such as the relatively low incidence of masturbation among females, the relative infrequency of fantasy in connection with female masturbation, the relatively low incidences of homosexual contacts among females, and many of the other statistics in this volume, agree with the findings in previous statistical studies. Detailed comparisons of certain of these items are shown in Table 9 , and comparisons of many more are made in the footnotes throughout this volume, particularly in Chapters 4 through 13 .

Table 9. Comparisons of Data in Present and Previous Studies

Percentages given are incidence of experience unless otherwise indicated. Comparisons are made with the nearest comparable groups, and recalculations on both our own and the previous studies had to be made in some instances to secure comparable groups. Such recalculations of data from previous studies are shown in italics.

It is very difficult to make comparisons between various studies in this area, because of the different ways in which the age groups, educational levels, and other portions of the samples have been classified, and because many of the important factors, like the decade of birth and the religious backgrounds, were not considered in most of the previous studies. In most previous studies the reported incidence data are neither accumulative nor active incidences, but the incidences of experience up to the point at which the subjects had contributed their histories to the study; and in most instances the published studies do not make specific correlations with the ages at which the subjects contributed their histories. Consequently the comparisons made both in Table 9 and in the footnotes throughout this volume cannot be more than approximate. It is all the more surprising, therefore, to find that they are in accord as often as they are.

Throughout the years of this study we have been accumulating recorded data on human sexual behavior, and these have been the bases for much of the non-statistical and more general discussions which appear in the present volume.

The recorded data to which we have had access represent calendars, diaries, correspondence, drawings, and various other types of material accumulated by a considerable number of our subjects and contributed to our files for preservation and study. Records made at the time of sexual activity or soon thereafter are valuable because they are not so liable to be affected by the errors of memory which may get into a case history obtained some years after the event. The recorded material may also contain a great deal more detail than can be obtained in an interview. Such records may still be distorted by deliberate or unconscious cover-up, and may show considerable bias in the choice of the material which the subject elects to preserve; but such a bias may in itself be significant, for it may reflect the subject’s interests better than they can be described in an interview. In addition, the recorded data may reflect unconscious or unexpressed desires. Of some of these desires, the subject may not be sufficiently aware to report them in an interview. Not infrequently the recorded material concerns types of sexual behavior which the subject has never accepted as part of his or her overt activity, although the subject may be psychologically interested in them.

Even though it has been difficult to quantify and statistically treat most of this recorded material, it has been invaluable in its portrayal of the attitudes of the subjects in the study, the social, moral, and other factors which had influenced the development of their patterns of sexual behavior, details concerning the techniques of their socio-sexual approaches, the techniques of their overt relationships, their own evaluations of their sexual experience, and their reactions to the persons with whom they had been involved.

Specifically, the recorded data and documentary materials which are in the files of the Institute for Sex Research, and which have been utilized in the present study, include the following:

Calendars . Some 377 persons, representing 312 females and 65 males, have contributed sexual calendars which show, as a minimum, the dates on which their sexual activities had occurred. In many instances, the calendars distinguish the types of sexual activity, solitary or socio-sexual, in which the subject had engaged, and activities which led to orgasm are distinguished from those which did not lead to orgasm. Most of the female calendars show how the activities were related to periods of menstruation. In some instances there are data concerning other social activities, trips during which the subject was away from the spouse, periods of illness, and still other factors that had affected the frequencies of sexual contact.

The time covered by these calendars has ranged from six months to as long a period as thirty-eight years. The emphasis on the importance of such calendars, made by Havelock Ellis some years ago, inspired a number of persons to begin keeping records, and we have profited by having access to some of these. 5 Many of the calendars were started by females who were interested in becoming pregnant and who in consequence kept records of menstruation which they, at the physician’s suggestion, had correlated with their coital activities. Many of the calendars have come from scientifically trained persons who have comprehended the importance of keeping systematic records. Many of the calendars are a product of our call for such material in the male volume. We are not yet certain whether the keeping of a calendar modifies an individual’s sexual behavior, but we are inclined to believe that any such modification lasts for only a short period of time.

Persons who have kept calendars, or who are willing to begin keeping day-by-day calendars showing the sources and frequencies of their outlet, are urged to write us for instructions.

Diaries . Some scores of individuals, including both females and males, have kept more elaborate records of their sexual activities, either as occasional diaries, or as day-by-day diaries, or as tabulations in other forms which they have turned into our files. The diaries often include detailed accounts of the situations and the techniques involved in sexual contacts, lists and descriptions of sexual partners, discussions of attitudes, and reports on the social consequences of the activities.

The journals and correspondence of literary persons, and of other persons in public positions, have always constituted a significant part of the world’s published literature and have provided source material for the biographer and historian. The sexual portions of such journals usually do not reach publication, but in a number of instances they have been made available to us for our special study. 6 Persons who have kept diaries or journals which have included a record of their sexual activities, or who are willing to begin keeping such diaries, are urged to deposit them in the files of the Institute for Sex Research where they will be kept as confidentially as the case history material.

Correspondence . We have extensive files of correspondence between spouses and between other sexual partners. In addition to recording overt sexual contacts, such correspondence often shows the emotional backgrounds out of which the sexual activities emerged. Some of this correspondence has come from persons of some literary fame. It should be emphasized, however, that correspondence originating from a person with no literary ability may also give considerable insight into the author’s thinking on matters of sex. Our file of correspondence carried on surreptitiously by prison inmates, for instance, has provided important information.

Original Fiction . Many persons, including some of considerable literary ability, may, on occasion, write fiction which is primarily intended to satisfy their erotic interests. In the choice of the subject matter of such fiction, in the choice of the characters who participate in the fictional action, and in the emphases placed upon particular details of the sexual activity, the writer often discloses interests and thinking which are brought to the surface only with difficulty in an interview. Such material has, consequently, been of considerable value in extending our understanding of some of the subjects of our case histories.

Erotic fiction, for reasons discussed in Chapter 16 , is more frequently produced by males. As that chapter will show, it would be of considerable importance to secure additional material, whether it is openly erotic or more general and amatory material, written by females.

Scrapbooks and Photographic Collections . Many persons make scrapbooks which, inevitably, turn about their special sexual interests. They collect newspaper or magazine clippings, or photographs and drawings cut from magazines, bought from commercial photographers, or gathered from their friends. Not a few persons photograph their sexual partners, or collect other materials which have been associated with their partners, and many such collections have been contributed for the present study. There are materials gathered from prison inmates, collections turned over to us by courts and police who have handled sex cases, collections of fine art, and still other types of material. Persons wishing to add such material to the files of the Institute would, consequently, be contributing to our basic understanding of human sexual behavior. Such collections are more frequently made by males (see Chapter 16 ), and it would be particularly valuable to secure additional material collected by females.

Art Materials . In an attempt to determine the extent to which erotic elements have contributed to the development of the world’s fine art, we have been engaged for some years in obtaining the histories of living artists and in correlating each history with the character of the work done by the artist. Each artist has helped us accumulate originals or printed or photographic reproductions of his or her artistic output. We now have originals or copies of some 16,000 works of art, contemporary and non-contemporary, which are providing materials for this study.

The artist’s drawing or painting provides something more than a photographic reproduction of the person or of the scene which he is depicting. In his emphasis on particular items, in his exaggeration of particular parts of the body, in his arrangement of the elements of the total composition, and in his selection of particular subject matter, he interprets his material in terms of his own special interests. The amateur is unable to introduce such emphases and exaggerations without making them so apparent that they become distortions instead of interpretations of the reality. For this very reason, however, amateur drawings are even more likely to expose conscious or sometimes subconscious sexual interests. 7 The doodlings which artists often do in their spare moments may give an especial insight into their thinking on matters of sex. Many artists have done more specifically erotic drawings or paintings. Since erotic art is more frequently produced by males (Chapter 16 ), we particularly need additional material done by females.

Toilet Wall Inscriptions . From the days of ancient Greece and Rome, it has been realized that uninhibited expressions of sexual desires may be found in the anonymous inscriptions scratched in out-of-the-way places by authors who may freely express themselves because they never expect to be identified. Students of anthropology, folklore, psychology, psychiatry, and the social sciences have found such graffiti (inscriptions, usually on walls and the like) a rich source of information. 8 In Chapter 16 we show that such material epitomizes some of the most basic differences between male and female sexual psychology. The importance of the toilet wall inscriptions which we have accumulated should become apparent upon examining the data presented in that chapter. Since males are more prone to produce such graffiti, we particularly need additional collections of material originating from females.

Other Erotic Materials . All erotic materials, whatever their nature, provide information on the interests of the persons who produce them, or of the public which consumes them. The sexual attitudes of whole cultures may be better exposed by their openly erotic drawings, paintings, and sculpture, than by their more inhibited art. The gross exaggerations of the erotic art of ancient Rome, the intensely emotional and religious approach to sex which is evident in Hindu erotic art, the emotionally undisturbed acceptance of sex in ancient Japanese art, and the fine portrayals of sexual action in later Greek art, provide some of the best information which we have on the sexual mores and attitudes of those cultures. 9 The preoccupation of present-day erotic art with matters which do not occur so often in any overt form in the case histories, emphasizes the persistence of suppressed desires in our own culture.

Sado-Masochistic Material . As a particular instance of the erotic items which must be comprehended in any study of current social problems, there is the considerable body of literature, art, and other materials which reflect human interest in the giving and receiving of pain. It has long been recognized that there is a relationship between such sado-masochistic interests and sex, but the relationship is probably not as direct and invariable as current psychologic and psychiatric theory would have it. 10

Because of the considerable interest which any social organization has in protecting itself from persons who force sexual relations upon others, and who inflict physical damage during such relationships, we are attempting to understand the exact nature of the sexual element in this sort of activity. This has involved the accumulation of the histories of persons with specifically sadistic or masochistic experience, the accumulation of correspondence, drawings, scrapbooks, collections of photographs, and other documentary materials, the accumulation of a considerable library of published and amateur writing, and a study of prison cases of individuals who have been convicted of sex crimes involving the use of force. In connection with this study, it has been inevitable that we should accumulate a library of the world’s sadomasochistic literature, including the considerable body of religious writing on the martyrdom of early Christians and the saints, technical, legal, and philosophic treatises on the subject, and the sometimes scholarly but more often amateur fiction on cruelty, flagellation, torture, subjugation, prison camps, and legalized punishment. 11 As a result of our study of the basic physiology of sexual response, we are acquiring some understanding of the relationship between responses to pain and the sexual syndrome (Chapters 14 –15 ). From all of this we may, some day, come to understand some of the factors which account for the occurrence of sex crimes which involve the use of force.

All of the sciences depend upon observed data as their ultimate sources of information. Matter which may be observed with one’s eyes, ears, nose, or other sense organs constitutes the part of the universe with which the scientist is best equipped to deal. Sometimes observations have to be made indirectly, as through a microscope or some more complex instrument, or when the existence of sub-microscopic units must be detected by their effects upon other, more observable phenomena. Nonetheless, it is still observation which provides most of our scientific knowledge. It is unfortunate that so much of our information on human sexual behavior must be acquired secondhand, through the reports of persons who have been involved in such behavior; but there is obviously no way in which anyone could observe the behavior of any other human being through all of the hours and years of a lifetime. In consequence, observation has not provided as much information as the reported and even the recorded materials in the present study; but data derived from the direct observation of mammalian sexual activities and human socio-sexual relationships have, nevertheless, constituted an important source of the information on which we have based the present study of human sexual behavior.

Community Studies . In securing case histories, we have spent many hours and sometimes days and weeks in various types of city communities, in rural communities, in schools, in homes for children, in university communities, in penal institutions, and in the still other areas from which we were securing histories. We have watched many individuals making socio-sexual approaches in taverns, on street corners, at dances, on college campuses, at swimming pools, on ocean beaches, and elsewhere. We have spent time in the homes of many of our subjects, visited with their friends, gone with them to taverns, night clubs, the theatre, and concerts, and become acquainted with the other places in which they were finding their recreation and in which many of them were finding their sexual partners. We have had an opportunity to listen to such discussions of sex as are characteristic of each community, and to observe the sorts of social situations which lead to sexual activity. Such observations have checked the adequacy of the records we were securing in the case histories. Our understanding, for instance, of the greater acceptability of pre-marital coitus in lower level groups, and its lesser acceptability in upper level groups, depends upon a considerable body of information which we have obtained in our community contacts, as well as upon the data in our case histories. It would be difficult to quantify and statistically tabulate the information which we have acquired from these community contacts, but they have constituted an integral part of the background out of which many of our generalizations have grown. 12

Clinical Studies . Throughout this study on human sexual behavior we have spent considerable time with anatomists, gynecologists, obstetricians, urologists, neurologists, endocrinologists, clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and other clinicians who have made their experience and in many instances their extensive records available to us for study. Thus we have had the benefit of the accumulated observations made by some scores of physicians in the course of their practice. We have had similar cooperation from criminologists, penologists, law enforcement officials, social workers, public health officers, laboratory physiologists, marriage counselors, anthropologists, geneticists, sociologists, students of animal behavior, students of child development, military and naval officers, students of law, and still others who have dealt with human problems. Many of these persons have served as special consultants in the preparation of the present volume.

A number of these clinicians have collaborated by gathering special data for our study. Thus the record which we present in the present volume (Chapter 14 ) on the sensitivity of the various areas of the female genitalia, is based upon observations made for us by a group of cooperating gynecologists on nearly nine hundred of their female patients.

Mammalian Studies . The opportunity to observe sexual activity either in the human or lower mammals is limited not only by the custom, but by the fact that such activity occurs only occasionally, and then so briefly that there is usually little opportunity to analyze the activity in any detail. In consequence, careful studies of sexual behavior among mammals of even domesticated species have been surprisingly few. Most of the scientific studies have been confined to laboratory experiments on certain aspects of the physiology of sexual response; and while these have provided important data, 13 they have not given us the considerable body of observations which we have needed on the gross physiology of sexual response and orgasm. With this as an objective, we have undertaken observational studies on mammalian sexual behavior, and have gone to some lengths to accumulate data from other persons who have made such observations.

Since the human animal, in the course of its evolution, has acquired both its basic anatomy and its physiologic capacities from its mammalian ancestors, studies of sexual behavior in the lower mammals may contribute materially to our understanding of human sexual behavior (Chapters 14 –18 ).

Because of the extreme rapidity of sexual response, and because the responses may involve every part of the animal’s body, it is exceedingly difficult and usually impossible to observe all that is taking place in the few seconds or minute or two which are usually involved in sexual activity. We have, therefore, found it necessary to supplement our direct observations with moving picture records which we, and several others collaborating with the research, have now made on the sexual activities of some fourteen species of mammals. 14 With the photographic record, it is possible to examine and reexamine the identical performance any number of times and, if necessary, examine and measure the details on any single frame of the film. Thus we have been able to analyze the physiologic bases of the action in various parts of the animal body (Chapters 15 , 17 ).

We have also been able to utilize records made by a number of persons who have had the opportunity to observe human sexual behavior. Parents who have observed their young children in sexual activities, and scientifically trained persons who, on occasion, have found the opportunity to observe adult performances in which they themselves were not participants, have reported some of these observations in the technical literature (Chapters 14 –15 , 17 ). Most of the material which has been made available to us has never before been published. These and the observations on other mammals have provided, throughout the present volume, data which we have used for analyzing the physiologic bases of sexual response and orgasm, and for comparing the similarities and differences between the responses of human females and males (Chapters 14 –16 ).

The research staff which has been responsible for the present volume has included persons trained in biology, psychology, anthropology, the social sciences, law, statistics, and still other areas. We have therefore been able to make a critical use of the previously published studies which have had a bearing on human sexual behavior.

Anthropologic Studies . Throughout the present volume we have presented comparative data on sexual behavior in some of the other cultures of the world. The anthropologic record of specifically sexual activity is, however, generally scant and highly inadequate. Aside from a limited number of biographies, there are practically no case histories made in pre-literate societies. Instead, the anthropologist has usually had to depend upon such general information as he could pick up in group discussions, upon a limited number of informants, or upon observation of that portion of the sexual behavior which is publicly displayed. As a result, he may obtain a general impression of what is openly advocated, expected, permitted, discouraged, or condemned within a given society (the overt culture), but how the people privately behave (the covert culture) is not accurately or fully revealed by such sources of information. The discrepancies that may exist between an overt and covert culture are, as anthropologists well know, often considerable.

The general inadequacy of the anthropologic record in sexual matters has been primarily due to the reluctance of the majority of the investigators to consider specific aspects of sex. Most of this reluctance stems from the anthropologist’s inability to overcome his own cultural conditioning. Only too frequently he excuses himself on the grounds that sexual questioning would spoil rapport with his subjects, but the success of those few explorers who have seriously attempted to gather sexual information indicates that valid and reasonably extensive data may be collected without undue difficulty, provided that the interviewing is well done.

The lack of any systematic coverage in any of the studies makes it difficult to use them for establishing any broad generalizations. For instance, a report which contains data concerning pre-marital and extra-marital coitus may completely fail to mention masturbation or homosexuality. One acquires the impression that the investigator recorded the sexual data which were readily available and made no additional effort to secure the remainder of the record. In view of the highly systematized and minutely detailed studies accorded such things as kinship terminologies, canoe-building, and the like, the scant and random treatment of sexual behavior seems all the more remarkable.

The mistakes and omissions of the past are, unfortunately, embalmed in the literature and handicap the research of persons who merely depend on that literature, or on the “Human Relations Area Files” which are now being accumulated through the joint efforts of the anthropologists in a number of American universities. The anthropologic data reported in previous studies, as well as in the present volume, must therefore be viewed as illustrative of the behavior in which some individuals have engaged in each of these cultures, although they may not be adequate descriptions of patterns which are widespread in any of them. 15

Legal Studies . Our study of sex law and sex offenders has utilized recorded, reported, and observed data as well as the published legal record in this area. We now have the histories of females and males who have been convicted of sex offenses in some 1300 instances. Our studies in penal institutions have been made with the whole-hearted cooperation of both the inmate bodies and the institutional administrations, and have given us an opportunity to understand the sorts of situations which brought the sex offender into conflict with the law and the problems which he now faces in reestablishing his position in the social organization.

We have spent time observing court processes and acquiring an acquaintance with the attitudes of judges, prosecutors, the police, penal administrators, and other officers who have handled sex offenders. We have secured the histories of some of these law enforcement officers, and thereby obtained some insight into the motivations which lie back of their policies in dealing with sex offenders. We have made intensive studies of the administration of the sex laws in a number of large cities and of some smaller towns scattered widely over the United States. Our legally trained associate is making an intensive study of the sex law of the forty-eight states, the interpretation of that law in published court decisions, the historical development of the statutes in each of the states, and something of the English and other European backgrounds of American sex law. Most of this material will be published later, but it has provided the brief summaries and the footnote annotations which appear throughout the present volume. These show the application of the laws in the various states to masturbation, petting, pre-marital coitus, extra-marital coitus, homosexual activities, and still other types of sexual behavior. We have also recorded data on the ways in which the sex laws are enforced.

Previous Statistical Studies . Most of the earlier studies which had systematically gathered data on the sexual behavior of American females and males and statistically analyzed those data were reviewed in our volume on the male (1948: 21–34). The list, including the additions published since 1948, now stands as follows:

1. Achilles, P. S. 1923. The effectiveness of certain social hygiene literature. New York, American Social Hygiene Association, 116p.

2. Ackerson, L. 1931. Children’s behavior problems. A statistical study based upon 5000 children examined consecutively at the Illinois Institute for Juvenile Research. I. Incidence, genetic and intellectual factors. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, xxi+268p.

3. Bromley, D. D., and Britten, F. H. 1938. Youth and sex. A study of 1300 college students. New York and London, Harper & Brothers, xiii+303p.

4. Davis, K. B. 1929. Factors in the sex life of twenty-two hundred women. New York and London, Harper & Brothers, xx+430p.

5. Dickinson, R. L., and Beam, L. 1931. A thousand marriages. A medical study of sex adjustment. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins Company, xxv+482p.

6. Dickinson, R. L., and Beam, L. 1934. The single woman. A medical study in sex education. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins Company, xix+469p.

7. Ehrmann, W. W. (in preparation). Pre-marital dating behavior. New York, Dryden Press.

8. Exner, M. J. 1915. Problems and principles of sex instruction. A study of 948 college men. New York, Association Press, 39p.

9. Finger, F. W. 1947. Sex beliefs and practices among male college students. J. Abnorm. & Soc. Psych. 42:57–67.

10. (Gilbert Youth Research.) 1951. How wild are college students? Pageant (Nov.), pp. 10–21.

11. Glueck, S., and Glueck, E. T. 1934. Five hundred delinquent women. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, xxiv+539+x p.

12. Hamilton, G. V. 1929. A research in marriage. New York, Albert & Charles Bani, xiii+570p.

13. Hohman, L. B., and Schaffner, B. 1947. The sex lives of unmarried men. Amer. J. Soc. 52:501–507.

14. Hughes, W. L. 1926. Sex experiences of boyhood. J. Soc. Hyg. 12: 262–273.

15. Landis, C., et al. 1940. Sex in development. New York and London, Paul B. Roeber, xx+329p.

16. Landis, C., and Bolles, M. M. 1942. Personality and sexuality of the physically handicapped woman. New York and London, Paul B. Roeber, xii+171p.

17. Locke, H. J. 1951. Predicting adjustment in marriage: a comparison of a divorced and a happily married group. New York, Henry Holt and Co., xx+407p.

18. Merrill, L. 1918. A summary of findings in a study of sexualism among a group of one hundred delinquent boys. J. Delinquency 3: 255–267.