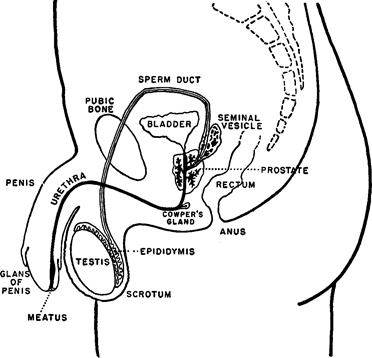

Figure 118. Female reproductive and genital anatomy

In our previous volume (1948) we presented data on the incidences and frequencies of the various types of sexual activity in the human male, and attempted to analyze some of the biologic and social factors which affect those activities. In the previous section of the present volume we have presented similar data for the female. Now it is possible to make comparisons of the sexual activities of the human female and male, and in such comparisons it should be possible to discover some of the basic factors which account for the similarities and the differences between the two sexes.

In view of the historical backgrounds of our Judeo-Christian culture, comparisons of females and males must be undertaken with some trepidation and a considerable sense of responsibility. It should not be forgotten that the social status of women under early Jewish and Christian rule was not much above that which women still hold in the older Asiatic cultures. Their current position in our present-day social organization has been acquired only after some centuries of conflict between the sexes. There were early bans on the female’s participation in most of the activities of the social organization; in later centuries there were chivalrous and galante attempts to place her in a unique position in the cultural life of the day. There are still male antagonisms to her emergence as a co-equal in the home and in social affairs. There are romantic rationalizations which obscure the real problems that are involved and, down to the present day, there is more heat than logic in most attempts to show that women are the equal of men, or that the human female differs in some fundamental way from the human male. It would be surprising if we, the present investigators, should have wholly freed ourselves from such century-old biases and succeeded in comparing the two sexes with the complete objectivity which is possible in areas of science that are of less direct import in human affairs. We have, however, tried to accumulate the data with a minimum of pre-judgment, and attempted to make interpretations which would fit those data.

It takes two sexes to carry on the business of our human social organization; but men will never learn to get along better with women, or women with men, until each understands the other as they are and not as they hope or imagine them to be. We cannot believe that social relations between the sexes, and sexual relations in particular, can ever be improved if we continue to be deluded by the longstanding fictions about the similarities, identities, and differences which are supposed to exist between men and women.

It must be emphasized again that what any animal does depends upon the nature of the stimulus which it receives, its physical structure, the capacity of that structure to respond to the given stimulus, and the nature of its previous experience. Its anatomy, its physiology, and its psychology must all be considered before one can adequately understand why the animal behaves as it does.

It is the physical structure which receives the stimulus and responds to it. Some knowledge of the anatomy of that structure and of the way in which it functions must be had before one can make adequate psychologic or social interpretations of any type of behavior. But, conversely, no knowledge of structures can completely explain the behavior unless psychologic factors are taken into account. From the lowest to the highest organism, psychologic factors—the animal’s previous experience, what it has learned, and the extent to which its present behavior is conditioned by its previous activity—will determine the way in which its structures function.

Psychologic factors become most significant among those species which have the most highly developed nervous systems. Among mammals, with their highly complex brains, the psychologic aspects of behavior may become of primary importance. This is true of sexual as well as of other types of behavior. It is, of course, particularly true of man, the most complex of all the mammals; and this provides some justification for the considerable attention which has, heretofore, been given to the psychologic and social aspects of human sexual behavior. Nothing we have said or may subsequently say in this chapter or in any other part of our report should be construed to mean that we are unaware of the importance of psychologic factors in human sexual behavior.

Much of the psychologic theory about sex has, however, been developed without any adequate appreciation of the anatomy which is involved whenever there is sexual response. In the human species, there have been anatomic studies of the external genitalia, primarily of the female; there have been studies of the way in which stimulation of those genitalia may be transmitted to the lower levels of the spinal cord, and of the mechanisms by which those portions of the cord then effect genital erection, pelvic thrusts, and orgasm. There have been studies of the significance of the cerebral cortex when there is psychologic stimulation which leads to sexual response (p. 710). But this is about the limit of the sexual anatomy and physiology which has been investigated, and this represents only a small portion of the anatomy and physiology which is actually involved. There has been hardly any investigation of the physiologic changes which occur throughout the body of the animal whenever it is aroused sexually. In fact, there has been a considerable failure to comprehend that sexual responses ever involve anything more than genital responses. We no longer consider the heart the seat of love, or an inflammation of the brain the source of the drive which impels the human creature to perform carnal acts; but we fall almost as far short of the fact when we think of the genitalia as the only structures or even the primary structures which are involved in a sexual response.

Some years ago we realized that it would be impossible to make significant interpretations of our data on human sexual behavior, and especially on the sexual behavior of the human female, or to make significant comparisons of female and male sexuality, until we obtained some better understanding of the anatomy and physiology of sexual response and orgasm. We could never have understood the female’s responses in masturbation, in nocturnal dreams, in petting, in coitus, and in homosexual relations, as they are presented in the previous chapters of this volume, and we could never have understood the basic similarities and differences between females and males, if we had not first become acquainted with the anatomy and physiology on which sexual functions depend.

There have been six chief sources of the data which we now have on the nature of sexual response and orgasm. These have been:

1. Reports from individuals who, in the course of contributing their histories to this study, have attempted to describe and analyze their own sexual reactions.

2. An invaluable record from scientifically trained persons who have observed human sexual activities in which they themselves were not involved, and who have kept records of their observations.

3. Observations which we and other students have made on the sexual activities of some of the infra-human species of mammals, and a great library of documentary film which we have accumulated for this study of animal behavior.

4. Published clinical data and a body of unpublished gynecologic data that have been made available for the present project.

5. Published data on the gross anatomy of those parts of the body which are involved in sexual response, and some special data on the histology (the detailed anatomy) of some of those structures.

6. The published record of physiologic experiments on the sexual activities of lower mammals and, to a lesser extent, of the human animal.

It is difficult, although not impossible, to acquire any adequate understanding of the physiology of sexual response from clinical records or case history data, for they constitute secondhand reports which depend for their validity upon the capacity of the individual to observe his or her own activity, and upon his or her ability to analyze the physical and physiologic bases of those activities. In no other area have the physiologist and the student of behavior had to rely upon such secondhand sources, while having so little access to direct observation.

This difficulty is particularly acute in the study of sexual behavior because the participant in a sexual relationship becomes physiologically incapacitated as an observer. Sexual arousal reduces one’s capacities to see, to hear, to smell, to taste, or to feel with anything like normal acuity, and at the moment of orgasm one’s sensory capacities may completely fail (Chapter 15 ). It is for this reason that most persons are unaware that orgasm is anything more than a genital response and that all parts of their bodies as well as their genitalia are involved when they respond sexually. Persons who have tried to describe their experiences in orgasm may produce literary or artistic descriptions, but they rarely contribute to any understanding of the physiology which is involved.

The usefulness of the observed data to which we have had access depends in no small degree upon the fact that the observations were made in every instance by scientifically trained observers. Moreover, in the interpretation of these data we have had the cooperation of a considerable group of anatomists, physiologists, neurologists, endocrinologists, gynecologists, psychiatrists, and other specialists. The materials are still scant and additional physiologic studies will need to be made.

Among the mammals, tactile stimulation from touch, pressure, or more general contact is the sort of physical stimulation which most often brings sexual response. In some other groups of animals, sexual responses are more often evoked by other sorts of sensory stimuli. Among the insects, for instance, the organs of smell and taste are most often involved. In such vertebrates as the fish it becomes difficult to distinguish between responses to sound and responses to pressure. It is true that among mammals, sexual responses may also be initiated through the organs of sight, hearing, smell, and taste; but tactile stimuli account for most mammalian sexual responses.

It has long been recognized that tactile responses are akin to sexual responses, 1 but we now understand that sexual responses amount to something more than simple tactile responses. A sexual response is one which leads the animal to engage in mating behavior, or to manifest some portion of the reactions which are shown in mating behavior. Mating behavior always involves a whole series of physiologic changes, only a small portion of which ordinarily develop when an individual is simply touched. The matter will become apparent as we analyze the data in this and the next chapter.

The organs which make the animal aware that it has been touched, and which at times may lead it to make more specifically sexual responses, are the end organs of touch (nerve endings) that are located in the skin, and some of the deeper nerves of the body. Certain areas of the body which are richly supplied with end organs have long been recognized as “erogenous zones.” 2 In the petting techniques which many females and males regularly utilize (Chapter 7 ), the sexual significance of these areas is commonly recognized. It is, in consequence, surprising to find how many persons still think of the external reproductive organs, the genitalia, as the only true “sex organs,” and believe that arousal sufficient to effect orgasm can be achieved only when those structures are directly stimulated.

The data that are given here on the sensitivity of certain structures must, therefore, be considered in relation to the fact that the tactile stimulation of all other surfaces which contain end organs of touch may also produce some degree of erotic arousal.

Penis . In the female and male mammal the external reproductive organs, the genitalia, develop embryologically from a common pattern. 3 They are, therefore, homologous structures in the technical meaning of the term. In spite of considerable dissimilarities in the gross anatomy of the adult female and male genitalia, each structure in the one sex is homologous to some structure in the other sex. During the first two months of human embryonic development, the differences between the male and the female structures are so slight that it is very difficult to identify the sex of the embryo. In any consideration of the functions of the adult genitalia, and especially of their liability to sensory stimulation, it is important and imperative that one take into account the homologous origins of the structures in the two sexes.

Figure 118. Female reproductive and genital anatomy

The embryonic phallus becomes the penis of the male or the clitoris of the female (Figures 118 , 119 ). The adult structures in both cases are richly supplied with nerves which terminate in what seem to be specialized sorts of end organs of touch—some of which are called Meissner’s corpuscles, and some Krause’s genital corpuscles. 4

It is commonly understood that the lower edge of the head (the glans) of the penis, or what is technically known as the corona of the glans, is the area that is most sensitive to tactile stimulation. The area on the under surface of the penis directly below the cleft of the glans is similarly sensitive to stimulation. This latter area lies directly beneath the longitudinal fold (the frenum) by which the loose foreskin is attached if it has not been removed by circumcision.

It appears, however, that there is a minimum of sensation in the main shaft of the penis or in the skin covering it. When the frenum is moved to one side or cut away, pressure on the original point shows that it is as sensitive as it was before the removal of the skin. Stimulation applied by inserting a probe into the urethra similarly shows that the sensory nerves are not located between the urethra and the under surface of the organ, but between the urethra and the spongy mass which forms the shaft of the penis. It remains for the neurologist and the student of male anatomy to identify the exact nerves which are involved, but the present evidence seems to show that they end deep in the shaft of the penis and not in its epidermal covering.

In addition to reactions to sensory stimulation, mechanical reactions also appear to be involved in the erection of the penis. It has been generally assumed that the increased How of blood into the organ during sexual arousal depends entirely upon circulatory changes which are effected by tactile or other sorts of erotic stimulation; but the possibility that mechanical effects may have something to do with the erection needs consideration. Forward pressures exerted on the corona of the glans not only effect sensory stimulation but, just as in stripping a wet piece of sponge rubber, also help crowd blood into the glans. Similarly, downward pressures on the upper (the distal) ends of the two spongy bodies (the corpora cavernosa) which constitute the shaft of the penis, and especially pressures on the upper edges of the spongy bodies at the point where they meet directly under the frenum, may stimulate the deep-seated nerves; but they may also have some mechanical effect in crowding blood into the corpora.

The effects of any direct stimulation of the penis are so obvious that the organ has assumed a significance which probably exceeds its real importance. The male is likely to localize most of his sexual reactions in his genitalia, and his sexual partner is also likely to consider that this is the part of the body which must be stimulated if the male is to be aroused. This overemphasis on genital action has served, more than anything else, to divert attention from the activities which go on in other parts of the body during sexual response. It has even been suggested that the larger size of the male phallus accounts for most of the differences between female and male sexual responses, and that a female who had a phallus as large as the average penis might respond as quickly, as frequently, and as intensely as the average male. But this is not in accord with our understanding of the basic factors in sexual response. There are fundamental psychologic differences between the two sexes (Chapter 16 ) which could not be affected by any genital transformation. This opinion is further confirmed by the fact that among several of the other primates, including the gibbon and some of the monkeys, the clitoris of the female is about as large as the penis of the male, but the basic psychosexual differences between the female and male are still present. 5

Clitoris . The clitoris, which is the phallus of the female, is the homologue of the penis of the male (Figures 118 , 119 ). The shaft of the clitoris may average something over an inch in length. It has a diameter which is less than that of a pencil. Most of the clitoris is embedded in the soft tissue which constitutes the upper (i.e. , the anterior) wall of the vestibule to the vagina. The head (glans) of the clitoris is ordinarily the only portion which protrudes beyond the body. In many females the foreskin (the hood) of the clitoris completely covers the head and adheres to it, and then no portion of the clitoris is readily apparent. Because of the small size of any protrudent portions, no localizations of sensitive areas on the corona or on other parts of the clitoris have been recorded.

Also because of its small size and the limited protrusion of the clitoris, many males do not understand that it may be as important a center of stimulation for females as the penis is for males. However, most females consciously or subconsciously recognize the importance of this structure in sexual response. There are many females who are incapable of maximum arousal unless the clitoris is sufficiently stimulated.

In connection with the present study, five gynecologists have cooperated by testing the sensitivity of the clitoris and other parts of the genitalia of nearly nine hundred females. The results, shown in Table 174 , constitute a precise and important body of data on a matter which has heretofore been poorly understood and vigorously debated. The record shows that there is some individual variation in the sensitivity of the clitoris: 2 per cent of the tested women seemed to be unaware of tactile stimulation, but 98 per cent were aware of such tactile stimulation of the organ. Similarly, there is considerable evidence that most females respond erotically, often with considerable intensity and immediacy, whenever the clitoris is tactilely stimulated.

We have already noted (p. 158, Table 37 ) that a high percentage of all the females who masturbate use techniques which involve some sort of rhythmic stimulation of the clitoris, usually with a finger or several fingers or the whole hand. Such techniques often involve the stimulation of the inner surfaces of the labia minora as well, but then each digital stroke usually ends against the clitoris. When the technique includes rhythmic pressure on those structures, the effectiveness of the action may still depend upon the sensitivity of the clitoris and of the labia minora. Even direct penetrations of the vagina during masturbation may depend for their effectiveness on the fact that the base of the clitoris, which is located in the anterior wall of the vagina, may be stimulated by the penetrating object.

Figure 119. Male reproductive and genital anatomy

Whenever female homosexual relations include genital techniques, the clitoris is usually involved (Table 130 ). This is particularly significant because the partners in such contacts often know more about female genital function than either of the partners in a heterosexual relation. While there are more females than males who achieve orgasm through the stimulation of some area other than their genitalia, certainly there are no structures in the female which are more sensitive than the clitoris, the labia minora, and the extension of the labia into the vestibule of the vagina.

The male who comprehends the importance of the clitoris regularly provides manual or other mechanical stimulation of that structure during pre-coital petting. In coitus, he sees to it that the clitoris makes contact with his pubic area, the base of his penis, or some other part of his body. Oral stimulation of the female genitalia is most often directed toward the labia minora or the clitoris.

Some of the psychoanalysts, ignoring the anatomic data, minimize the importance of the clitoris while insisting on the importance of the vagina in female sexual response (p. 582).

Urethra and Meatus . The penis of the male is normally penetrated for its full length by the urethra (Figure 119 ). The urethra of the female does not penetrate the clitoris; instead it lies in the soft tissues which constitute the upper (the anterior) wall of the vagina (Figure 118 ). The opening of the urethra of the male (the meatus) is normally on the tip of the head of the penis (Figure 119 ); in the female it is located between the clitoris and the entrance to the vagina (Figure 118 ).

A few persons, females and males, employ masturbatory techniques which include insertions of objects into the urethra. 6 The urethral lining which has not become accustomed to such penetration is so sensitive that most individuals, upon initial experimentation, desist from further activity. More experienced persons claim that they receive some erotic stimulation from the penetrations. The recorded satisfactions may include reactions to pain, and sometimes they may be wholly psychologic in origin. Urethral insertions may also stimulate the nerves which lie in the tissue about the urethra of the female, or deep in the shaft of the penis of the male.

There is evidence that the area surrounding the meatus is supplied in some individuals with an accumulation of nerves. 7 Consequently, direct stimulation of the meatus is sometimes included in the masturbatory procedures. This may happen more often in the female than in the male.

Labia Minora . The inner lips of the female genitalia, the labia minora (Figure 118 ), are homologous with a portion of the skin covering the shaft of the penis of the male. Both the outer and the inner surfaces of the labia minora appear to be supplied with more nerves than most other skin-covered parts of the body, and are highly sensitive to tactile stimulation. The gynecologic examinations made for this study showed that some 98 per cent of the tested women were conscious of tactile stimulation when it was applied to either the outside or inside surfaces of the labia, and about equally responsive to stimulation of either the left or right labium (Table 174 ).

Table 174. Responses to Tactile Stimulation and to Pressure, in Female Genital Structures

The check (✓) shows response, x shows lack of response to stimulation in the designated area. The tests were made by five experienced gynecologists, two of them female, on a total of 879 females. In all of the tests, the vagina was spread with a speculum, and all testing of internal structures was done with especial care not to provide any simultaneous stimulation of the external areas. The tests of tactile responsiveness were made with a glass, metal, or cotton-tipped probe with which the indicated areas were gently stroked. Awareness of pressure was tested by exerting distinct pressure at the indicated points with an object larger than a probe. Finer standardizations of the tests proved impractical under the office conditions. It should he noted that awareness of tactile stimulation or of pressure does not demonstrate the capacity to he aroused erotically by similar stimuli; hut it seems probable that any area which is not responsive to tactile stimulation or pressure cannot he involved in erotic response.

As sources of erotic arousal, the labia minora seem to be fully as important as the clitoris. Consequently, masturbation in the female usually involves some sort of stimulation of the inner surfaces of these labia. Sometimes this is accomplished through digital strokes which may be confined to the labial surfaces; usually the strokes extend to the clitoris which is located at the upper (the anterior) end of the genital area where the two labia minora unite to form a clitoral hood. However, manipulation of the labia may also involve nerves that lie deep within their tissues. This is suggested by the fact that digital stimulation of the labia is often effected while the thighs are tightly pressed together so pressure may be exerted on the labia. Sometimes the technique may involve nothing more than a tightening of the thighs or a crossing of the legs, without digital stimulation. Sometimes the labia are rhythmically pulled in masturbation. During coitus, the entrance of the male organ into the vagina may provide considerable stimulation for the labia minora. All of these techniques are also significant in producing the muscular tensions which are of prime importance in the development of sexual responses (p. 618).

Labia Majora and Scrotum . The solid, outer lips (the labia majora) of the female genitalia are (at least in part) homologues of the skin which forms the scrotum of the male (Figures 118 , 119 ). Both structures develop from the two swollen ridges which lie on the sides of the genital area in the developing embryo. They form the lateral limits of the adult female genitalia. The homologous ridges in the male embryo become hollow during their development. Finally their two cavities unite to form a single cavity in a single sac, the scrotum of the male. In the human male, shortly before the completion of embryonic development, the testes, which have previously been located in the body cavity, descend through the inguinal canals (which lie in the groins) and take up their permanent locations in the scrotum.

The labia majora of the female are sensitive to tactile stimulation. This was so in some 92 per cent of the women who were tested by the gynecologists (Table 174 ). But there is a difference between the capacity to respond to tactile stimulation and the capacity to respond erotically. Although it is improbable that any area which is insensitive to tactile manipulation could be stimulated erotically, some areas which are tactilely sensitive (e.g. , the backs of the hands, the shoulders) are of no especial importance as sources of erotic response. We do not yet have evidence that the labia majora contribute in any important way to the erotic responses of the female.

Neither do we have any evidence that the skin of the scrotum is more sensitive than any other skin-covered surface of the body, and the scrotum does not seem an important source of erotic arousal. 8 There are quite a few males who react erotically, and a small number who may respond to the point of orgasm when there is some stimulation or more active manipulation of the testes; but this response is not due to the stimulation of the skin of the scrotum.

Vestibule of Vagina . The labia minora continue inward to form a broad, funnel-shaped vestibule which leads to the actual entrance (the orifice or introitus) of the vagina (Figure 118 ). The structure represents an in-pocketing of external epidermis which is well supplied with end organs of touch. Nearly all females—about 97 per cent according to the gynecologic tests (Table 174 )—are distinctly conscious of tactile stimulation applied anywhere in this vestibule, and only a very occasional female out of the 879 who were tested proved to be entirely insensitive in the area. For nearly all women the vestibule is as important a source of erotic stimulation as the labia minora or the clitoris. Since the vestibule must be penetrated by the penis of the male in coitus, it is of considerable importance as a source of erotic stimulation for the female.

The hymen of the virgin female is a more or less thin membrane which lies at the inner limits of the vestibule. It is attached by its outer rim, partially blocking the entrance to the vagina. It usually has a natural opening of some diameter located in the center of the membrane, but this may, of course, be enlarged either by coitus or by the insertion of fingers, tampons, or other objects. An unusually thick or tough hymen which might cause considerable pain if it were first stretched or torn in coitus, may be more easily stretched or cut by the physician who makes a pre-marital examination. Remnants of the hymen almost always persist even after long years of coital experience, and the remnant of the tissue is sometimes sensitive. It is not clear whether the sensitivity depends on nerves in the remnants of the tissue or on the fact that movements of the tissue may stimulate the underlying nerves.

A ring of powerful muscles (the levator muscles) lies just beyond the vaginal entrance. The cavity of the vagina extends beyond this point. The female may be very conscious of pressure on the levators. The muscles may respond reflexly when they are stimulated by pressure, and most females are erotically aroused when they are so stimulated.

Interior of Vagina . The vagina is the internal cavity which lies beyond the external genitalia of the female (Figure 118 ). Unlike its vestibule, the vagina is derived embryologically from the primitive egg ducts which, like nearly all other internal body structures, are poorly supplied with end organs of touch. The internal (entodermal) origin of the lining of the vagina makes it similar in this respect to the rectum and other parts of the digestive tract. There is no functional homologue of the vagina in the male.

In most females the walls of the vagina are devoid of end organs of touch and are quite insensitive when they are gently stroked or lightly pressed. For most individuals the insensitivity extends to every part of the vagina. Among the women who were tested in our gynecologic sample, less than 14 per cent were at all conscious that they had been touched (Table 174 ). Most of those who did make some response had the sensitivity confined to certain points, in most cases on the upper (anterior) walls of the vagina just inside the vaginal entrance. The limited histologic studies of vaginal tissues confirm this experimental evidence that end organs of touch are in most cases lacking in the walls of the vagina, although some nerves have been found at spots in the vaginal walls of some individuals. 9

This insensitivity of the vagina has been recognized by gynecologists who regularly probe and do surface operations in this area without using anesthesia. 10 Under such conditions most patients show little if any awareness of pain. There is some individual variation in this regard, and clinicians are aware of this, for they ordinarily stand prepared to administer a local anesthetic if the patient does register pain.

The relative unimportance of the vagina as a center of erotic stimulation is further attested by the fact that relatively few females masturbate by making deep vaginal insertions (p. 161, Table 37 ). Fully 84 per cent of the females in the sample who had masturbated had depended chiefly on labial and clitorial stimulation. Although some 20 per cent had masturbated on occasion by inserting their fingers or other objects into the vagina, only a small portion had regularly used that technique. Moreover, the majority of those who had made insertions did so primarily for the sake of providing additional pressure on the introital ring of muscles, or to stimulate the anterior wall of the vagina at the base of the clitoris, and they had not made deeper insertions. As we shall note below, there is satisfaction to be obtained from deeper penetration of the vagina by way of nerve masses that lie outside of the vaginal wall itself, but all the evidence indicates that the vaginal walls are quite insensitive in the great majority of females. 11

In most of the homosexual relations had by females, there is no attempt at deep vaginal insertions (Table 130 ). Once again, the insertions that are made are usually confined to the introitus or intended to stimulate the anterior wall of the vagina at the base of the clitoris. Occasionally there are deeper penetrations in order to reach the perineal nerves (p. 584). This restriction of so much of the homosexual technique is especially significant because, as we have already noted, homosexual females have a better than average understanding of female genital anatomy.

On the other hand, many females, and perhaps a majority of them, find that when coitus involves deep vaginal penetrations, they secure a type of satisfaction which differs from that provided by the stimulation of the labia or clitoris alone. In view of the evidence that the walls of the vagina are ordinarily insensitive, it is obvious that the satisfactions obtained from vaginal penetration must depend on some mechanism that lies outside of the vaginal walls themselves.

There is a parallel situation in anal coitus. The anus, like the entrance to the vagina, is richly supplied with nerves, but the rectum, like the depths of the vagina, is a tube which is poorly supplied with sensory nerves. However, the receiving partner, female or male, often reports that the deep penetration of the rectum may bring satisfaction which is, in many respects, comparable to that which may be obtained from a deep vaginal insertion.

There may be six or more sources of the satisfactions obtainable from deep vaginal penetrations, and several or all of these may be involved in any particular case. The six sources are:

1. Psychologic satisfaction in knowing that a sexual union and deep penetration have been effected. The realization that the partner is being satisfied may be a factor of considerable importance here.

2. Tactile stimulation coming from the full body contact with the partner, and from his weight. This may result in pressures on various internal organs which can produce “referred sensations.” These may be incorrectly interpreted as coming from surface stimulation.

3. Tactile stimulation by the male genitalia or body pressing against the labia minora, the clitoris, or the vestibule of the vagina. This alone would provide sufficient stimulation to bring most females to orgasm. The location of this stimulation may be correctly recognized, or it may be incorrectly attributed to the interior of the vagina (see p. 584).

4. Stimulation of the levator ring of muscles in coitus. Such stimulation may bring reflex spasms which may have distinctly erotic significance.

5. Stimulation of the nerves that lie on the perineal muscle mass (the so-called pelvic sling), which is located between the rectum and the vagina (see the discussion of the perineum, below).

6. The direct stimulation, in some females, of end organs in the walls of the vagina itself. But this can be true only of the 14 per cent who are conscious of tactile stimulation of the area. There is, however, no evidence that the vagina is ever the sole source of arousal, or even the primary source of erotic arousal in any female.

Some of the psychoanalysts and some other clinicians insist that only vaginal stimulation and a “vaginal orgasm” can provide a psychologically satisfactory culmination to the activity of a “sexually mature” female. It is difficult, however, in the light of our present understanding of the anatomy and physiology of sexual response, to understand what can be meant by a “vaginal orgasm.” The literature usually implies that the vagina itself should be the center of sensory stimulation, and this as we have seen is a physical and physiologic impossibility for nearly all females. Freud recognized that the clitoris is highly sensitive and the vagina insensitive in the younger female, but he contended that psychosexual maturation involved a subordination of clitoral reactions and a development of sensitivity within the vagina itself; but there are no anatomic data to indicate that such a physical transformation has ever been observed or is possible. 12

The concept of a vaginal orgasm may mean, on the other hand, that the spasms that accompany or follow orgasm involve the vagina; and in much of the psychoanalytic literature there is an implication that the vagina must be chiefly involved before one may expect any maximum and “mature” psychosexual satisfaction. 13 This is an equally untenable interpretation for, as we shall see in Chapter 15 , most parts of the nervous system, and all parts of the body which are controlled by those parts of the nervous system, are involved whenever there is sexual response and orgasm. In some individuals the spasms or convulsions that follow orgasm are intense and prolonged, and in others they are mild and of short duration. The individual differences in patterns of response are quite persistent throughout an individual’s lifetime, and probably depend upon inherent capacities more than upon learned acquirements. Those females who have extensive spasms throughout their bodies when they reach orgasm are the ones who are likely to have vaginal convulsions of some magnitude at the same time. Those who make few gross body responses in orgasm are not likely to show intense vaginal contractions. No question of “maturity” seems to be involved, and there is no evidence that the vagina responds in orgasm as a separate organ and apart from the total body. Whether a female or male derives more or less intense sensory or psychologic satisfaction when the vaginal spasms are more or less extreme is a matter which it would be very difficult to analyze.

This question is one of considerable importance because much of the literature and many of the clinicians, including psychoanalysts and some of the clinical psychologists and marriage counselors, have expended considerable effort trying to teach their patients to transfer “clitoral responses” into “vaginal responses.” Some hundreds of the women in our own study and many thousands of the patients of certain clinicians have consequently been much disturbed by their failure to accomplish this biologic impossibility.

Cervix . The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus (Figure 118 ). It protrudes into the deeper recesses of the vaginal cavity, and stands out from the vaginal wall as a rounded and blunt tip about as large or larger than the tip of a thumb. It has been identified by some of our subjects, as well as by many of the patients who go to gynecologists, as an area which must be stimulated by the penetrating male organ before they can achieve full and complete satisfaction in orgasm; but most females are incapable of localizing the sources of their sexual arousal, and gynecologic patients may insist that they feel the clinician touching the cervix when, in reality, the stimulation had been applied to the upper (anterior) wall of the vestibule to the vagina near the clitoris. All of the clinical and experimental data show that the surface of the cervix is the most completely insensitive part of the female genital anatomy. Some 95 per cent of the 879 women tested by the gynecologists for the present study were totally unaware that they had been touched when the cervix was stroked or even lightly pressed (Table 174 ). Less than 5 per cent were more or less conscious of such stimulation, and only 2 per cent of the group showed anything more than localized and vague responses.

Histologic studies show that there are essentially no tactile nerve ends in the surfaces of the cervix. This is further confirmed by gynecologic experience, for the surfaces are regularly cauterized and operated upon in other ways without the use of any anesthesia—and nearly all such patients are unaware that they have been touched. Cutting deeper into the tissue of the cervix may lead an occasional patient to register pain, and the dilation of the cervical canal causes most patients to feel intense pain. In none of these instances, however, is there any evidence of erotic response. 14

Perineum . The perineal area includes and lies between the lower portions of the digestive and the reproductive tracts. The area is essentially the same in the female and the male. The surface of the perineum includes the anal and genital areas and all of the space between. This surface is highly sensitive to touch, and tactile stimulation of the area may provide considerable erotic arousal.

The perineal area is occupied for the most part by layers of muscles, the so-called pelvic sling. Within and on this muscular mass there are nerves, and the area is, in consequence, definitely sensitive when it is stimulated with any sufficiently strong pressure. Many males are quickly brought to erection when pressure is applied on the perineal surface at a point which is about midway between the anus and the scrotum. In the case of the female, strong pressure applied from inside on the posterior (lower) wall at the back of the vagina may stimulate these same nerves, and this is one of the sources of the satisfaction which many females experience when the vagina is penetrated in coitus. Deep penetrations of the rectum may stimulate the same perineal nerves, and prove to be similarly erotic.

Anus . The anal area is erotically responsive in some individuals. In others it appears to have no particular erotic significance even though it may be highly sensitive to tactile stimulation. As many as half or more of the population may find some degree of erotic satisfaction in anal stimulation, but good incidence data are not available. There are some females and males who may be as aroused erotically by anal stimulation as they are by stimulation of the genitalia, or who may be more intensely aroused.

The erotic sensitivity of the anal area depends in part upon the fact that there are abundant end organs of touch throughout the anal surfaces, and in part upon the fact that reactions of the muscles (the anal sphincters) which normally keep the anus closed may be erotically stimulating. Some persons are psychologically aroused while others respond negatively to the idea of anal intercourse, and psychologic factors may have a good deal to do with the erotic or non-erotic significance of such contacts. These generalizations apply to both females and males.

Penetration of the anus may cause pain, and this may intensify the sexual responses for some persons.

The anus is particularly significant in sexual responses because the anal and genital areas share some muscles in common, and the activity of either area may bring the other area into action. Stimulation of the genitalia, both in the female and the male, may cause anal constrictions. Gynecologists frequently observe that stimulation of the clitoris, or of the areas about the clitoris and the urethral meatus, may cause contractions of the anus, 15 the hymenal ring, and the vaginal and perineal muscles. As rhythmic muscular movements develop during sexual responses, and particularly in the spasms that follow orgasm, the anal sphincter may rhythmically open and close. The incentives for anal insertions of various sorts and for anal intercourse lie partly in the significance of these rhythmic responses of the anal sphincters.

Conversely, contractions of the anal sphincter, whether they be voluntary or initiated by erotic stimulation, may bring contractions of the muscles that extend into the genitalia and produce erection in the male or movement of the genital parts in the female. As a matter of fact, contractions of the anal sphincter appear to produce contractions of muscles in various remote parts of the body, including areas as far away as the throat and the nose. Anal contractions may cause the sides of the nose to flare, and the subject is inclined to inhale deeply—both of which are characteristic aspects of an individual who is responding sexually. When the clinician has difficulty in bringing a patient out of anesthesia, he may start deep breathing by inserting a gloved finger into the anus of the patient. Anal contractions may also be associated with contractions of still other muscles elsewhere in the body; for the contraction of any muscle, anywhere in the body, may develop tensions in every other muscle in the body (p. 618).

Apparently the abdominal diaphragm is involved when there is anal contraction, for it is very difficult for an individual to exhale as long as the anal sphincters are under any considerable tension.

In brief, anal contractions, perineal responses, genital responses, and nasal and oral responses are so closely associated that one may believe that some sort of simple and direct reflex arc is involved. We do not yet understand the neural bases of such a connection.

Breasts . The breasts of both the male and the female may be more sensitive than some other parts of the body. Because of the greater size of the female breast its reactions to tactile stimulation are quite generally known. Among the infra-human mammals, the breast rarely plays a part in sexual activity, 16 but among human animals there may be a considerable amount of manual or oral stimulation of the female breast. In American patterns of sexual behavior, breast stimulation most regularly occurs among the better educated groups where nearly all of the males (99%) manually manipulate the female breast, and about 93 per cent orally stimulate the female breast during heterosexual petting or pre-coital play (Tables 73 , 100 ). All of this usually stimulates the male erotically, but the significance for the female has probably been overestimated. There are some females who appear to find no erotic satisfaction in having their breasts manipulated; perhaps half of them do derive some distinct satisfaction, but not more than a very small percentage ever respond intensely enough to reach orgasm as a result of such stimulation (Chapter 5 ). 17 Some females hold their own breasts during masturbation, coitus, or homosexual activities, evidently deriving some satisfaction from the pressure so applied; but there were only 11 per cent of the females in our sample who recorded any frequent use of breast stimulation as an aid to masturbation (Table 37 ).

Because of their smaller size the sensitivity of the male breasts has not so often been recognized except among some of the males who have had homosexual experience. This is undoubtedly not due to differences between heterosexual and homosexual males, but to the fact that relatively few females ever try to stimulate the breasts of their male partners, whereas such behavior is rather frequent in male homosexual relations. Our homosexual histories suggest that there may be as many males as there are females whose breasts are distinctly sensitive. A few males may even reach orgasm as a result of breast stimulation. 18

Mouth . The lips, the tongue, and the whole interior of the mouth constitute or could constitute for most individuals an erogenous area of nearly as great significance as the genitalia. Erotic arousal always involves the entire nervous system, and there appears to be some oral response whenever there is sexual arousal. We have already noted (p. 586) the apparently reflex connections between contractions of the genital, anal, nasal, and oral musculatures. Most uninhibited individuals become quite conscious of their oral responses, particularly if they accept deep kissing, mouth-breast contacts, or mouth-genital contacts as part of their sexual play.

The significance of the mouth depends, of course, upon the fact that all of its parts are richly supplied with nerves. This is true throughout the class Mammalia, and also true of some of the other vertebrates. Fish, lizards, many birds, and practically all of the mammalian species which have been studied are likely to place their mouths on some part of the partner’s body during pre-coital play or actual coitus (see p. 229). Mouth-to-mouth contacts between some of the birds and mammals may occasionally be continued for hours. The sexual significance of the mouth is obviously of long phylogenetic standing. 19 The human animal testifies to its origin when it engages in mouth activity during sexual relationships. The human is exceptional among the mammals when it abstains from oral activities because of learned social proprieties, moral restraints, or exaggerated ideas of sanitation.

In the course of mammalian oral activity, the lips may be pressed against the mouth or against some other portion of the partner’s body; tongues are brought into contact or used to lick the body; the lips and the teeth may nibble, or the teeth may bite more severely somewhere on the partner’s body. In some of the lower mammals (e.g. , the mink) such biting may penetrate the skin of the partner, 20 and while this is the means by which the males of these species hold the females in position for coitus, the immediate source of such behavior probably lies in the sensory satisfaction which the male secures by making these contacts. Even such large animals as stallions, which are ill-equipped to make contacts with their mouths, keep their lips in constant motion during sexual activity and constantly attempt to nibble or bite over the surface of the body of the mare. In many mammalian species, where the tip of the nose may be as sensitive as the lips of the mouth, the lips and the nose are used indiscriminately to make contacts with all parts of the body. 21 All of these things also happen during sexual activity in an uninhibited human animal.

It is not surprising that the two areas of the body which are most sensitive erotically, namely the mouth and the genitalia, should frequently be brought into direct contact. The high incidence of such mouth-genital contacts in all species of mammals, from one to the other end of the class Mammalia, and the high frequency of mouth-genital contacts in the human animal have been detailed in our volume on the male (1948: especially pages 368–373, 573–578), and in the present volume (pp. 229, 257).

Ears . The lobe of the ear and the inner cavity leading from it are points of especial sensitivity for at least some persons. 22 The ear lobes become engorged with blood during sexual arousal, and become increasingly sensitive at that time. An occasional female or male may reach orgasm as a result of the stimulation of the ears.

Buttocks . Tactile stimulation and heavier pressure on the buttocks may elicit unusually strong responses from the gluteal muscles. 23 These are the largest and the chief muscles on the back surface of the upper part of the leg. Contractions of these muscles reflect, more than any other one factor, the development of the nervous and muscular tensions which are involved in erotic arousal. Some persons, both female and male, deliberately contract these gluteal muscles to build up their erotic responses. Movements of vertebral muscles in conjunction with contractions of the gluteal muscles are the chief means by which the pelvis is thrown forward in rhythmic thrusts during copulation.

Thighs . The thin-skinned, inner surfaces of the thighs, particularly on their midlines, are richly supplied with nerves. Any tactile stimulation of these areas may contribute to erotic arousal. 24 Such stimulation may bring responses of the adductor muscles on the inner faces of the thighs, and of the abductor muscles which are located on the outer surfaces of the legs, and as a result the thighs may be rolled together or thrown apart with distinctive movements that are characteristic of much coital, masturbatory, and other sexual activity. These movements of the adductors and abductors are also involved in the build-up of nervous tensions throughout the whole body (see p. 618).

Other Body Surfaces . The areas just listed are the ones which are most often concerned in erotic stimulation and response. Other parts of the body may, however, be involved, and for some individuals these other parts may be as significant as any of the particular areas listed.

The nape of the neck, the throat, the soles of the feet, the palms of the hand, the armpits, the tips of the fingers, the toes, the navel area, the midline at the lower end of the back, the whole abdominal area, the whole pubic area, the groin, and still other parts have been recognized as areas which may be erotically sensitive under tactile stimulation. Even non-sensitive, non-living structures like teeth and hair may sometimes become sources of erotic stimulation, because movements of those structures stimulate the sensitive nerves that lie at their bases. There are females in our histories who have been brought to orgasm by having their eyebrows stroked, or by having the hairs on some other part of their bodies gently blown, or by having pressure applied on the teeth alone. This may be a factor in the biting which often accompanies sexual activities. Such stimuli are most effective when there is some accompanying and significant psychologic stimulation. Acting alone, these unusual sorts of stimuli would rarely be sufficient to effect any considerable arousal. Acting in conjunction with other physical and psychologic stimuli, they may, on occasion, provide the additional impetus which is necessary to carry the individual on to orgasm.

Many persons are conscious of the fact that they are sexually stimulated by things that they see, smell, taste, or hear. Oriental, Islamic, Classical Greek and Roman, Medieval, Galante, and more modern European sex literatures regularly refer to odors and to other chemical stimuli which are “aphrodisiacs” capable of exciting sexual responses.

But it is not certain that stimuli received through these other sense organs effect erotic arousal in the same direct fashion that tactile stimuli do. It is conceivable that great intensities of light, lights of particular colors, or movements of lights of different intensities or of different colors, do have some direct effect upon an animal’s sexual responses; but specific investigations have not yet been made.

It is also not impossible and even probable that strong odors, spices, and loud noises have direct effects upon the nervous system and thus start the physiologic changes which constitute sexual response. It is rather clear that particular sorts of rhythms (e.g. , march and waltz time), variations of tempo, particular sequences of pitch (e.g. , continued repetitions of one note or chord, alternations of tones which lie an exact octave apart), and variations in volume (e.g. , crescendos and diminuendos, sudden and sharp notes, heavy chords) produce physiologic effects on the human and on some other animals which have some affinity to sexual responses. But on none of these points have there been sufficient scientific studies to warrant further discussion here.

It is more certain that stimuli received through these other sense organs operate primarily through the psychic associations which they evoke (p. 647). The arousal which the average male and some females experience in seeing persons with whom they have had previous sexual contacts, in seeing potential new partners, or in seeing articles of clothing or other objects which have been connected with some previous experience, must depend largely upon the fact that they are reacting, consciously or subconsciously, to memories of the past events. In the same fashion one may be aroused by entering a room, seeing a beach, a mountain top, or a sunset which, by its similarity to some situation associated with the previous sexual contact, brings arousal through recall of that experience. Sexual arousal from the taste of some particular food, through particular odors, or from hearing particular birds sing, particular tones of ringing bells, certain words spoken, the tones of particular voices, particular musical themes sung or played, or any other particular sounds, appears to depend largely upon associations of those things with previous sexual experience.

All of this is a picture of psychologic learning and conditioning, and not one of direct mechanical stimulation of the sort which tactile stimuli provide. In considering the erotic significances of things that are seen, smelled, tasted, or heard, the possibility that both psychologic and sensory factors are involved should, therefore, always be taken into account.

The physical differences between the genitalia and reproductive functions of the mammalian female and male have been the chief basis for the longstanding opinion that there must be similarly great differences in the sexual physiology and psychology of the two sexes. In view of the considerable significance of such concepts in human social relations, it has, therefore, been important to reexamine and reevaluate the similarities and differences in the anatomic structures which are involved in sexual responses and orgasm in the two sexes. Specifically we have found that:

1. In both sexes, end organs of touch are the chief physical bases of sexual response. There seems to be no reason for believing that these organs are located differently in the two sexes, that they are on the whole more or less abundant in either sex, or that there are basic differences in the capacities of the two sexes to respond to the stimulation of these end organs.

2. The genitalia of the female and the male originate embryologically from essentially identical structures and, as adult structures, their homologous parts serve very similar functions. The penis, in spite of its greater size, is not known to be better equipped with sensory nerves than the much smaller clitoris. Both structures are of considerable significance in sexual arousal. The chief consequence of the larger size of the penis is the fact that sexual stimulation is more often directed specifically toward it. Its larger size accounts in part for the greater psychologic significance of the penis to the male.

3. The labia minora and the vestibule of the vagina provide more extensive sensitive areas in the female than are to be found in any homologous structure of the male. Any advantage which the larger size of the male phallus may provide is equalled or surpassed by the greater extension of the tactilely sensitive areas in the female genitalia.

4. The larger and more protrudent and more extensible phallus of the male, and the more internal anatomy of the female, are factors which may determine the roles which the two sexes assume in coitus. The female may find psychologic satisfaction in her function in receiving, while the male may find satisfaction in his capacity to penetrate during coitus, but it is not clear that this could account for the more aggressive part which the average male plays, and the less aggressive part which the average female plays in sexual activity. The differences in aggressiveness of the average female and male appear to depend upon something more than the differences in their genital anatomy (see Chapters 16 and 18 ).

5. The vagina of the female is not matched by any functioning structure in the male, but it is of minimum importance in contributing to the erotic responses of the female. It may even contribute more to the sexual arousal of the male than it does to the arousal of the female.

6. The perineal area provides a considerable source of stimulation for both the female and the male. In the male, nerves located among the perineal muscles may be stimulated through direct pressure on the external surface of the perineum or through the rectum; in the female, the area may be stimulated in exactly the same fashion or through vaginal penetrations.

7. Because female breasts are larger, they may appear to be more significant to the female than male breasts are to the male. But since most males are aroused by seeing female breasts, and because most females are, in actuality, only moderately aroused by having their breasts tactilely stimulated, female breasts may be more important sources of erotic stimulation to males than they are to females.

8. The mouth, which is one of the most important erotic areas of the mammalian body, appears to be equally sensitive in the female and the male.

9. Tactile stimulatiou of the buttocks and of the inner surfaces of the thighs may play a significant part in the picture of sexual response. Responses to such stimulation seem to be essentially the same in the female and the male.

10. All of the other body surfaces which respond to tactile stimuli seem to function, as far as the specific evidence goes, identically in the two sexes.

11. There are no data to indicate that there are any differences in female and male responses which depend directly on the senses of sight, smell, taste, or hearing.

12. In brief, we conclude that the anatomic structures which are most essential to sexual response and orgasm are nearly identical in the human female and male. The differences are relatively few. They are associated with the different functions of the sexes in reproductive processes, but they are of no great significance in the origins and development of sexual response and orgasm. If females and males differ sexually in any basic way, those differences must originate in some other aspect of the biology or psychology of the two sexes (see Chapters 16 and 18 ). They do not originate in any of the anatomic structures which have been considered here.

1 As examples of this association of tactile and sexual responses, see: Bloch 1908:80. Havelock Ellis 1986(I,3):8–8. Freud 1988:599–600.

2 As examples of such lists of erogenous zones,.see: The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana [between 1st and 6th cent. A.D. , Sanskrit]. The Ananga Ranga [12th cent. A.D. ?, Sanskrit]. Van de Velde 1980:45–46. Havelock Ellis 1986(II,1): 148. Haire 1951:304–306.

3 For the embryology of the genitalia, see, for instance: Arey 1946:283–308. Patten 1946:575–607. Hamilton, Boyd, and Mossman 1947:193–223.

4 Recent authors are inclined to discard the concept of Krause’s corpuscles as end organs of touch and emphasize other end organs, especially Meissner’s. See: Fulton 1949:3–6, 17. Ruch in Howell (Fulton edit.) 1949:304–306. Houssay et al. 1951:836. Blake and Ramsey 1951:29. For data on Krause’s corpuscles, see: Eberth 1904:249. Jordan 1934:147. 149, 438, 467. Wharton 1947:10. Bailey 1948:585, 630. Dickinson 1949:58. Fulton 1949:6. Maximow and Bloom 1952:181, 524.

5 For data on the large clitoris of some primates, see: Hooton 1942:175, 231, 252, 273. Ford and Beach 1951:21. In examining spider monkeys we find the clitoris may be as long as or longer than the penis, although not as large in diameter.

6 Urethral insertions are also noted, for instance, in: Bloch 1908:411. Havelock Ellis 1936(1,1):171–173. Dickinson 1949:63,69. Grafenberg 1950:146. Haire 1951:147.

7 For nerve endings located about the urethral meatus of the female, see, for instance: Lewis 1942:8. Dickinson 1949:62.

8 Havelock Ellis 1936(II,1):123 also states that the scrotum “is not the seat of any voluptuous sensation.”

9 Relative lack of nerves and end organs in the vaginal surface is noted by: Dahl ace. Kuntz 1945:319. Undeutsch 1950:447. Dr. F. J. Hector (Bristol, England) and Dr. K. E. Kranz (University of Vermont) have furnished us with histologic data on this point. Vaginal sensitivity applying primarily to the area on the anterior wall at the base of the clitoris is also noted in: Lewis 1942:8. Grafenberg 1950:146, 148.

10 From our gynecologic consultants, we have abundant data on the limited necessity of using anesthesia in vaginal operations. See also Döderlein and Krönig 1907:88.

11 Simone de Beauvoir 1952:373 says vaginal pleasure certainly exists, and proposes (without specific data) that vaginal masturbation seems more common than we have indicated.

12 For Freud’s interpretation of the relative importance of the clitoris and vagina, and the adoption of this interpretation by many of the psychoanalysts, see, for instance: Freud 1933:161 (“…in the phallic phase of the girl, the clitoris is the dominant erotogenic zone. But it is not destined to remain so; with the change to femininity, the clitoris must give up to the vagina its sensitivity, and, with it, its importance, either wholly or in part”). Freud 1935:278 (“The clitoris in the girl, moreover, is in every way equivalent during childhood to the penis….In the transition to womanhood very much depends upon the early and complete relegation of this sensitivity from the clitoris over to the vaginal orifice”). Hitschmann and Bergler 1936: 15 (“… the girl … must undertake a removal of the leading sexual zone from the clitoris to the vagina….If this transition is not successful, then the woman cannot experience satisfaction in the sexual act….The first and decisive requisite of a normal orgasm is vaginal sensitivity ”). Deutsch 1945(2):80 (“… the clitoris preserves its excitability during the latency period and is unwilling to cede its function smoothly, while the vagina for its part does not prove completely willing to take over both functions, reproduction and sexual pleasure”). Fenichel 1945:82 (“The significance of the phallic period for the female sex is associated with the fact that the feminine genitals have two leading erogenous zones: the clitoris and the vagina. In the infantile genital period the former and in the adult period the latter is in the foreground. The change from the clitoris as the leading zone to the vagina is a step that definitely occurs in or after puberty only”). Kroger and Freed 1950:528 (“Hence, in the child the clitoris gives sexual satisfaction, while in the normal adult woman the vagina is supposed to be the principal sexual organ….in frigid women the transference of sexual satisfaction and excitement from the clitoris to the vagina, which usually occurs with emotional maturation, does not take place). See also: Chideckel1935:39. Ferenczi 1936: 255–256. Knight 1943:28. Abraham (1927) 1948:284.

13 The shift from clitoris to vagina is sometimes stated to be psychologic rather than physiologic, and in psychoanalytic theory the failure to effect this change is frequently considered the chief cause of frigidity. For example, see: Freud 1935:278 (“In those women who are sexually anaesthetic, as it is called, the clitoris has stubbornly retained this sensitivity”). Hitschmann and Bergler 1936:20 (“Under frigidity we understand the incapacity of woman to have a vaginal orgasm ….The sole criterion of frigidity is the absence of the vaginal orgasm”). Deutsch 1944(1):233 (“The competition of the clitoris, which intercepts the excitations unable to reach the vagina, and the genital trauma then create the dispositional basis of a permanent sexual inhibition, i.e. , frigidity”). Abraham (1927) 1948:359 (“In … frigidity the pleasurable sensation is as a rule situated in the clitoris and the vaginal zone has none”). Kroger and Freed 1950:526 (“However, as a general rule, the question of what constitutes true frigidity depends on whether clitoric or vaginal response is achieved. It is believed that the clitoris does not often come into contact with the male organ during intercourse, and, if a transfer in sensation occurs from the clitoris to the vagina, it is purely psychologic and unconscious. In completely frigid women this psychologic transmission is always disturbed. Therefore, the problem of frigidity is reduced to a psychologic basis”). See also: Lundberg and Farnham 1947:266. Stokes 1948:39. Bergler 1951:216 (transfer is purely psychologic). Beauvoir 1952:372 (“the clitorid orgasm … is a kind of detumescence … only indirectly connected with normal coition, and it plays no part in procreation”).

14 Our data on the insensitivity of the cervix come from the abundant experience of our gynecologic consultants. See our Table 174 . See also: Döderlein and Krönig 1907:88. Malchow 1923:183. Lewis 1942:8. Dickinson ms.

15 An early reference to anal contractions during coitus is found in Aristotle [4th cent. B.C. ]: Problems, Bk.IV:879b.

16 The relative infrequency of breast stimulation in the sexual activity of the infrahuman mammal is also noted by Ford and Beach 1951:48. See also p. 255 of the present volume.

17 Records of females reaching orgasm from breast stimulation alone are rare. In addition to our own data (p. 161), we note: Moraglia 1897:7–8. Rohleder 1921:44. Eberhard 1924:246. Kind and Moreck 1930:156. Dickinson 1949: 66–67. Grafenberg 1950:146.

18 The sensitivity of male breasts is recorded in our 1948:575. It is also recorded in: Van de Velde 1930:164. Féré 1932:105. Pillay 1950:81.

19 For our own data on oral activity among the lower mammals, see p. 229 including footnotes 3 and 4 . Also see: Yerkes 1929:296. Zuckerman 1932:123, 147, 227, 230. Yerkes and Elder 1936a: 10–11. Havelock Ellis 1936(1,2):85. Reed 1946:passim . Beach in Hoch and Zubin 1949:55–62. Ford and Beach 1951:46–55.

20 Biting through the skin of the sexual partner’s neck is recorded for the mink, ferret, marten, and sable. See also: Ford and Beach 1951:58–59.

21 Manipulation of the sexual partner’s body with the nose and lips has occurred among nearly all of the species of mammals which we have observed (see p. 229). See also: Stone 1922 (rat). Louttit 1927 (guinea pig). Shadle 1946 (porcupine). Reed 1946 (various mammals).

22 The erotic sensitivity of the ear is quite common knowledge. In the literature see: Van de Velde 1930:45. Havelock Ellis 1936(II,1): 143. Stone and Stone 1937:221; 1952:182. Beach 1947b:246.

23 Contraction of the buttocks was once considered the mechanism by which semen was expelled during coitus. See Aristotle [4th cent. B.C. ]: Problems, Bk.IV: 876b.

24 There are abundant data in our records on the erotic sensitivity of the inner surfaces of the thigh. There are few references in the published studies, but see: Van de Velde 1930:45. Havelock Ellis 1936(II,2):113. Kahn 1939:70. Fulton 1949:140 records that manipulation of this area can cause penile erection in dogs, cats, monkeys, and humans whose spinal cords are severed.