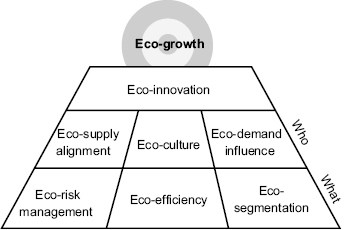

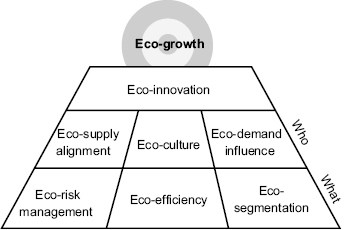

Figure 13.1 The elements of eco-growth

When A. G. Lafley returned to Procter & Gamble as CEO in 2013, his mandate was to spur growth in the face of increasing competition.1 “I am confident that we will deliver strong innovation, productivity, and growth to win with consumers, customers, and shareholders,” he said when appointed.2 Similarly, when Tom Mangas was named CEO of Armstrong Corporation, the $3 billion flooring manufacturer, a trade magazine quoted him as saying, “I'm going to ask a lot of questions and figure out how we can accelerate the growth.”3 Nothing in these statements is unique or surprising. As Bain & Company (and many scholarly articles) state, “For a business to survive, growth is an imperative, not an option.”4,5

If a business is not growing it is dying, according to conventional management wisdom. Almost all companies need to grow to achieve the lowest long-term costs (owing to scale); to protect themselves from competitors growing in other geographies and adjacent markets; and to provide advancement opportunities for talented employees. Just as important are shareholders’ and financial markets’ expectations of increasing profits. Societies, too, live under a kind of growth imperative: to seek to improve the quality of life of their growing populations through the creation of jobs and the conversion of the country's natural resources into wealth.

It was the best of times for growth, it was the worst of times for growth. Between 1994 and 2009, global GDP doubled6 as the world's middle class grew to 1.8 billion citizens. In countries such as China, India, Brazil, and Mexico, more consumers gained increased purchasing power. Developing countries continue to industrialize and urbanize. The middle class is expected to grow to 3.2 billion by 2020 (approximately 41 percent of the world population) and 4.9 billion by 2030 (approximately 58 percent of the world population7), according to Mario Pezzini, director of the OECD Development Center.8 These consumers strive for a “Western” standard of living that, in many ways, is defined by consumption.

The positive aspects of rising wealth come with a dark cloud of environmental impacts. Economic growth brings increased consumption of many natural resources such as water, minerals, forests, and sea life, as well as many kinds of emissions that can degrade these resources. In turn, the large companies, running the massive supply chains that use these resources, face pressure from NGOs, governments, and communities. “With the global middle class growing, we can all help to create solutions that use less water, less oil, less resources of all kinds. … After all, our businesses can only be as strong and healthy as the communities that we proudly serve,” said Muhtar Kent, CEO of Coca-Cola.9

Rising wealth means rising energy production for electricity, industry, and transportation. With this prosperity comes growing GHG emissions; between 1970 and 2011, carbon emissions nearly doubled. China, for example, now emits more GHGs from fossil fuel combustion than the US and the EU combined.10 Worldwide atmospheric levels of CO2 rose more than 20 percent between 1970 and 2016.11 If the 7.4 billion people alive in the world as of late 2016 attain the same standard of living as Americans, the world will need to almost quadruple its energy production.12 Even if the world emulates energy-efficient Germany, the total would still need to double.

Concern about GHGs started in the 1960s when scientists uncovered a link between ancient climate fluctuations and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. This concern was heightened when they also realized that CO2 levels were rising quickly in the modern world.13 Further data collection on both the past and present climate, as well as increasingly powerful climate models, led to ominous predictions of a significant rise in the Earth's temperature, the collapse of Antarctic ice sheets, and rise of sea levels. By 2001, the third report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated that global warming is “very likely,” with possible severe consequences. The fifth IPCC report in 2013 cited a variety of climate-related changes already taking place, warned of acceleration, and stated that it is “extremely likely” that the main cause is human activity.14

Still, a minority of scientists question the accuracy of the IPCC climate projections, arguing that the measurements and models are not exact enough to form the basis of policy. Other experts argue that climate change is not caused by human activity but rather by natural or unknown processes.15 Nonetheless, the majority scientific opinion resulted in a United Nations climate “Conference of Parties” (COP 21) in Paris in December 2015. At the conference, representatives of 196 countries agreed on a (nonbinding) resolution to limit global warming to 2°C by reducing net emissions of GHGs to zero during the second half of the 21st century. Such agreements, and the surrounding media attention, mean that consumers, investors, NGOs, and governments are likely to continue to demand that companies “do something” about the environment. In addition, companies are likely to be attacked if they are perceived as degrading the environment.

The amount of carbon released into the environment is not the only impact that worries activists, scientists, and policy makers, however. There is also concern of the resources that are removed from the ecosystem.

Half of India faces significant water stress due to population growth, overextraction, and pollution.16 Worldwide, about 1.2 billion people live in areas of physical water scarcity and another 1.6 billion face economic water shortages.17 At the same time, water is plentiful on the global level—the average volume of fresh surface water totals 3.5 million gallons per person.18 Ground water (accessible by pumping) and salt water (usable with desalination) offers thousands of times more water in some areas. Unfortunately, pumping and desalination require energy, which, with current technologies, entails more GHG emissions. Physical, regulatory, and social restrictions on water consumption could affect many categories of companies beyond the obvious ones in the agriculture and beverage sectors because many power generation and manufacturing processes also depend on water for both cooling and cleaning.

Between 1980 and 2013, demand for grain nearly doubled as more people could afford a more affluent diet, according to analysis by Syngenta.19 One example of a newly affordable item for many was beer, which grew in global production by more than one-third between 2000 and 2011, largely driven by a 120 percent surge in production in China. Despite this increase, AB InBev, the world's largest brewer, told investors: “Climate change, or legal, regulatory or market measures to address climate change could have a long-term, material adverse impact on AB InBev's business or operations.”20,21 In recent years, heavy rains, droughts, and heat waves have all affected barley yields.22 Climate change is forecast to make weather patterns more erratic, increasing the risk of crop failure.23

Brewers, and other agricultural commodity buyers, also face competition for arable land and water. For example, climate change-related policies in Germany are encouraging barley growers to switch to biofuel crops.24 This can affect total supplies, affordability, and sales of beer, which is the world's third most popular beverage (behind water and tea). Nearly all food products (and a great many other products such as apparel, cleansers, cosmetics, and furniture) depend on agriculture that might be affected by climate change, water scarcity, pollution, and rising demand. Land-use policies, such as those associated with deforestation and biodiversity, also potentially restrict growth in production of commodities such as palm oil, soybean, and beef, or create obstacles to the extraction of mineral resources.

Environmental activists call climate change “the challenge of our time.”25 Despite the inherent uncertainty and the complex assumptions underlying scientists’ climate models, as well as occasional contradictory data, most climate scientists believe that climate change is occurring as a result of human activity.

The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894 posited that London would be buried under nine feet of manure within 50 years, based on the exponential growth in the number of horses used in the city for personal and freight transportation.26 In New York (where 150,000 horses were producing 2,000 tons of manure each day), the first international urban planning conference estimated that manure would reach third floors by 1930. What they did not foresee was that, by 1912, Henry Ford would develop the assembly line process to make affordable automobiles, obviating the manure problem. Crisis averted as a result of new technology.

In 1919, David White, chief geologist of the United States Geological Survey, wrote of US petroleum: “… the peak of production will soon be passed, possibly within 3 years.”27 His was the first of what has become nearly a century's worth of “peak oil” warnings. In 1980, the world only had 27.9 years of oil left,28 and consumption was growing inexorably higher.

Fears of peak oil, volatile oil prices, and geopolitical stress between oil-producing countries and oil-consuming ones spurred investment and innovation, such as deepwater drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) that pull hidden oil out of old or previously infeasible fields. Innovations in geophysical sensing and computing allowed new oil fields to be discovered, and innovations in civil engineering enabled drilling in previously inaccessible areas. By 2013, despite 33 years of insatiable demand, reserves had grown to 49.5 years.29 This significant growth in reserves contributed to the plunge in the price of a barrel of oil from $140 in January 2008 to $30 per barrel in January 2016.

There are numerous examples of forecasts rendered wrong as a result of an unforeseen technological development. In fact, some currently unforeseen future technology may be able to capture CO2 and reduce its atmospheric concentration. Unfortunately, nothing like this seems to be on the current horizon. In fact, most scientific efforts are focused on reducing future emissions. Current experimental technologies like carbon capture and clean coal innovations are typically very expensive and require high energy inputs. The most promising avenue seems to be conservation and reduced use, which is the belief of many governments, NGOs, the mainstream media, and many consumers. As a result, one has to conclude, again, that regardless of personal beliefs and hopes, there are business reasons to pursue environmental initiatives.

The tension between financial performance and environmental performance is sometimes cast as a conflict between short-term and long-term interests.30 Many modern corporations practice what leading management thinker Peter Drucker warned about in 1986 when he wrote: “Corporate managements are being pushed into subordinating everything (even such long-range considerations as a company's market standing, its technology, indeed its basic wealth-producing capacity) to immediate earnings and next week's stock price.”31

Despite corporate shortcomings, the anti-capitalist, anti-corporate rhetoric of many environmentalists is misplaced. In practice, socialist autocratic governments were significantly worse for the environment compared with their capitalist corporate counterparts, because the regimes’ very survival depended on providing jobs and economic development. The former Soviet Union inflicted grave damage on the environment in Russia and the other Soviet republics in its quest for military and economic superiority.32 And Venezuela is facing “serious environmental issues including vegetation loss, wrong solid waste management, and pollution of basins and reservoirs of water for human consumption,” according to a 2016 article in the Caracas newspaper El Universal.33 In socialist central-planning regimes, short-term thinking is rooted in rampant corruption and shortcuts taken to meet government mandates regarding quotas.

Short-term thinking bedevils government institutions in the developed world as well—the results of election-cycle politics, populism, lame-duck outgoing officials, and special interest group lobbying. Environmental impact seems to be less a function of any particular economic ideology and more a function of the fundamental purpose of all economies and supply chains to satisfy humanity's needs and wants. That purpose has inevitably led to the extraction of resources from the Earth and emissions of by-products.

In June 2015, the mayors of 22 communities in Northern Ontario and Québec held a press conference at Parliament Hill, followed by a series of meetings with federal ministries to address what they called “eco-terrorism.”34 At issue were attacks by Greenpeace and ForestEthics on product and retail brand owners who source paper made from trees harvested by those communities. The mayors argued that the groups were targeting their “way of life,” using deliberate misinformation from organizations whose private politics have no regard for balancing the economic, social, and environmental sustainability of these northern communities.35

Although environmental activists portray sustainability as a battle of “profits versus planet”36 or “shareholders versus stakeholders,”37 those dichotomies of greed versus nature miss the deeper issue. The vilified financial profits and returns to shareholders are the monetary tip of a social iceberg in the form of (i) all the people whose livelihoods and communities depend on the supply chains of the maligned product or company, and (ii) all the consumers who want and rely on the products. Thus, the true tension between financial and environmental performance is not about shareholders versus stakeholders, but rather about (some) stakeholders versus (other) stakeholders, or (some) people versus (other) people.

Alberta, Canada, has the world's third-largest reserves of oil, behind only Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.38 But those 166 billion barrels of viscous crude oil lie locked in sandy formations that make extraction difficult and environmentally impactful. This results in open pit mines that scar the land where shallow layers of black oil sands can be dredged. Scattered nearby are more than 42,000 acres of toxic lakes39 containing sludgy tailings that reek of residual oil from the processing of the oil sands. The ponds contain heavy metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, nickel, vanadium, chromium, and selenium that potentially threaten both people and animals in the area.40 To extract deeply buried oil sands, miners burn large quantities of natural gas to generate steam that is injected into the ground to mobilize the thick gooey bituminous deposits.41 Overall, the energy required to extract and process oil sands adds 10 to 30 percent to the already high carbon footprint of regular oil.42 Moreover, the process consumes several barrels of water for every barrel of oil produced.

“The most destructive project on Earth” is what Rick Smith, executive director of the NGO Environmental Defence Canada, calls these oil sands fields.43 In 2010, ForestEthics began a campaign against US brand-name retailers and consumer goods companies, pressuring them to boycott fossil fuels derived from Canadian tar sands. “Unless you take action to take tar sands oil out of your footprint, you've got it in your footprint,” ForestEthics campaign director Aaron Sanger told companies.44 As the campaign gathered momentum, ForestEthics started publishing a growing list of companies that seemed to have agreed to its demands. The list included green companies such as Patagonia, Seventh Generation, and Whole Foods, as well as more mainstream companies, including Levi Strauss, The Gap, and FedEx (apparently without many of these companies’ knowledge or consent).45

In rebuttal, the Alberta government published facts about the large economic benefits and modest environmental impacts of the industry,46 which provided 30 percent of the GDP of the province. They touted the industry as the number one employer of indigenous (First Nations) people, its contribution to the provincial and Canadian tax base, and the estimated Can$2.5 trillion in revenues expected from existing and new projects over a 30-year period.

The government also argued that the industry was not as dirty as it was portrayed to be, noting that only 4,800 km2 out of 381,000 km2 of Alberta's boreal forest would be mined and that miners were recycling 80 to 95 percent of the water they used. The government also stated that oil sands producers had reduced per-barrel emissions by an average of 26 percent since 1990, with some achieving up to 50 percent reductions. Finally, the government pointed out that miners had already planted 12 million seedlings as part of required land reclamation efforts. The debate even had a semantic dimension, with environmentalists using the term “tar sands,”47 whereas the industry used the less dark terminology of “oil sands” or the even more technically correct term “bitumen sands.”48

The Canadian people were less measured in their reaction. “We invite Levi Strauss, The Gap, and the affiliates (as well as any other American/international company currently marketing their products in Canada that does not want to accept our ‘dirty’ money) to NO LONGER do business on Canadian soil. By all means, purchase your oil from regimes that provide NO human rights or environmental stewardship. Don't let the door hit your ‘behind’ on the way out,” said a reader commenting on the story.49 A nonprofit called Alberta Enterprise Group (AEG) launched a counter-boycott campaign on Facebook, urging Canadians to boycott the boycotters of Alberta's oil.50 AEG vice president David MacLean said, “We want to push back on behalf of Albertans who benefit from this industry.”51

Faced with heightened media coverage, some companies, who apparently did not consent to their inclusion in the ForestEthics list, clarified their position. Levi Strauss, The Gap, and Timberland criticized ForestEthics for including them on the NGO's anti-tar-sands list.52 “We do not take a position opposing or supporting any fuel or energy source from any country or geography,” said a Levi Strauss spokesperson. Timberland asked its transportation contractors to demonstrate that they were increasing the use of “low carbon fuels and avoiding carbon-intensive sources” but did not specifically boycott a “type or source of fuel,” a spokeswoman told CBC News.53

In 1978, the average Chinese citizen had an annual disposable income of only ¥343.4054 (or about $200 at prevailing exchange rates at the time55). China was a very poor country with a stagnant, inefficient, centrally controlled economy that was relatively isolated from global markets. Then, in 1979, the Chinese government opened the country to foreign investment, enacted free-market reforms, and embarked on the fastest industrialization drive the world has ever seen.

In economic terms, the results have been stellar. Hundreds of millions of Chinese rose out of poverty and joined the middle class as income per capita grew almost 100-fold56 to ¥33,616 in 2016.57 Many observers believe that per capita income is actually much larger owing to the “gray economy” that flourished after the reforms. The fast and powerful rise of China out of poverty to become the second-largest (and soon to be the leading) engine of the world economy is one of the central stories of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. By 2025 the Chinese middle class is expected to include 700 to 800 million people,58 about 50 to 60 percent of the projected Chinese population.

The story of China's economic miracle is also a story of China's significant environmental degradation.59 Air pollution exceeds the EPA's “unsafe” levels many days of the year, especially in coastal cities. Water pollution taints 90 percent of the groundwater used for irrigation, and 60 percent of the groundwater beneath Chinese cities is described as “very polluted.”60 Farmland turned to desert and biodiversity dropped under the onslaught of deforestation and excessive agricultural development.61 The wanton environmental destruction gave rise to “cancer villages,” which are so polluted that just living there poses a significant cancer risk.

Outdoor air pollution may have contributed to 1.2 million premature deaths in China in 2010, subtracting an estimated 25 million healthy years of life from the population.62 These mortality figures, however, are dwarfed by China's longevity gains. Life expectancy at birth in China increased from 65.5 in 1980 to 75.5 in 2013,63 which represents an increase of 13 billion healthy years of life for the population. Shanghai's life expectancy—83 years—equals that of Switzerland.64

Over this entire period, many Chinese accepted the trade-off between increasing standards of living on the one hand and environmental degradation on the other. In fact, 350 million Chinese voted with their feet by moving to the country's booming, but polluted, cities.65 And while environmentalists may lament China's policy choices, who should be the judge? Hundreds of millions of Chinese stakeholders chose (implicitly) higher standards of living (cars, housing, appliances, vacations, access to health care, improved education, and longer life span, among other things) over higher environmental standards. In the future, once the country becomes even richer, it may change its priorities, but its past and current priorities are clear.

The preference for better standards of living (or even just jobs) over environmental sustainability is not unique to China. “Apparel production is a springboard for national development, and often is the typical starter industry for countries engaged in export-oriented industrialization,” wrote Gary Gereffi and Stacey Frederick in a 2010 World Bank Policy Research working paper.66 The industry employs at least 40 million people worldwide and can provide increased purchasing power to lift people out of poverty.67,68 At the same time, the Natural Resources Defense Council claims that “textile-making is one of the most polluting industries in the world.”69 It added that “a single mill can use 200 tons of water for each ton of fabric it dyes. And rivers run red—or chartreuse, or teal, depending on what color is in fashion that season—with untreated toxic dyes washing off from mills.”

Nearly two months before the Rana Plaza textile factory collapse (see chapter 2), Disney ordered an end to sourcing from Bangladesh and four other countries (Pakistan, Belarus, Ecuador, and Venezuela) based on audits and personal visits by senior executives. The company told the affected licensees that it would pursue “a responsible transition that mitigates the impact to affected workers and business.” It implemented a year-long transitional period to phase out production by March 31, 2014.70

Others may follow Disney's departure from Bangladesh. If that happens on a large scale, it will severely damage the country's social and economic fabric. Garment manufacturing employs 3.6 million Bangladeshi workers. The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development said that, for women in particular, “working in garments, for all its many problems, was a better way to make money than what one had done in the past.”71

Similar concerns about unintended consequences were raised during the early efforts to block conflict minerals—an effort to stop militants in some parts of the Congo from mining with slave labor to fund war efforts and atrocities (see chapter 10). Some smelters’ initial response was to cease buying minerals from all of the Congo, but such a broad-brush approach was neither ethical nor responsible. “We got letters from the Congo and NGOs saying that there are 100,000 artisan miners in the Congo trying to earn money to eat,” said Gary Niekerk of Intel, pointing out that not all of the miners work for the militants.72 In the Congo, mining is one of the two primary legitimate sources of income available (farming being the other). “Putting a de facto ban on materials out of the Congo means that good people might starve,” Niekerk said. Damaging the country's legitimate economy would only fuel further unrest.

Abrupt counteractions can have unintended consequences in which initiatives intended to reduce impacts can destroy livelihoods. If the target is a first world region, like Canada's province of Alberta, the affected populations can muster political support and fight back. Most people in the developing world have neither that option nor any other employment options. Consequently, a company's well-intentioned environmental actions can hurt many people. In addition, higher prices for sustainable goods pose more of a burden on the poor than on richer consumers.73 Furthermore, biofuel mandates, which often use food crops such as corn and soybeans as a raw material, have induced higher food prices.74

Explaining the balancing act that companies have to perform, Mike Barry of Marks & Spencer said, “You've got to be constantly at the cutting edge of listening and engaging and triangulating trends and ideas.”75

“The challenge in setting standards and measuring progress is that there is no universally agreed definition for sustainability,” said Aron Cramer, president and CEO of consulting firm BSR, “and the standards that do apply vary by industry, commodity and even product line.”76 A Unilever spokesperson added, “There is no absolute measure of farm sustainability. It's a moving target.”77 As mentioned in chapter 4, well-written laws and regulations define what the legal profession terms a “bright-line”—a straightforward and easy-to-follow rule with a clear demarcation between acceptable and unacceptable behavior.78 An action is either on the legal side of the line or not, with no ambiguity. Unfortunately, no such bright line exists between what is sustainable and what is not, which leads to disputes involving companies aspiring to be green.

Matt Rogers, a global produce coordinator for Whole Foods said, “We're really proud of the food we sell, and we know a lot about it, in general, and we want to share that with customers.”79 To that end, the company worked for three years with growers, distributors, certifiers, and topic experts to develop a 41-item questionnaire that scored the sustainability of farmers. The farmers’ answers led to a prominent “Responsibly Grown” label listing a farmer's produce as unrated, good, better, or best.80 Yet when the grocer debuted the label in 2015, some organic farmers complained that lower-priced conventionally grown produce sometimes got a better rating than their higher-priced organic fruits and vegetables. Both the New York Times and NPR reported on examples of conventional produce labeled as “best,” while some nearby organic items were merely labeled “good.”81

“Organic is responsibly grown, for goodness sake,” said one dumbfounded fruit grower.82 Five farmers wrote an open letter to John McKay, co-CEO of Whole Foods to say, “We are deeply concerned that Whole Foods’ newly launched ‘Responsibly Grown’ rating program is onerous, expensive, and shifts the cost of this marketing initiative to growers, many of whom are family-scale farmers with narrow profit margins.”83

In response, Edmund LaMacchia, the company's global vice president of perishable purchasing and the primary executive sponsor of the Responsibly Grown program, published a long point-by-point online reply explaining the company's motives.84

One of the cosigners of the farmers’ complaint letter said, “I'm hopeful that, as it has in the past, Whole Foods will make some modifications.”85 Indeed, Whole Foods engaged with a nonprofit representative of organic farmers, California Certified Organic Farmers, to modify the program.86 The changes included automatically giving more points to Certified Organic and Biodynamic producers and granting them at least a “good” rating while the growers adjusted to the system.87

“Becoming organic is a big investment of time and money,” said Jeff Larkey of Route 1 Farms. “This ratings system kind of devalues all that—if you can get a ‘best’ rating as a conventional farmer using pesticides and other toxic substances, why would you grow organically?”88 In truth, the Responsibly Grown rating system does not allow unfettered use of pesticides. When the rating system was updated, LaMacchia said: “Ecologically produced food can be defined in many different ways. We will also make room to recognize the contributions of other growing methods to the sustainable food supply.” Although the updated system automatically awarded certified organic farms 88 points—covering 10 of the 41 questions in Whole Food's Responsibly Grown rating system—the “best” rating requires scoring 225 points (out of 300).89 Getting a “best” rating also requires pollinator protection and industry leadership on pest management and environmental protection.

“There is no system, certification, production method or brand that adequately addresses all of the fast-moving issues that we need to understand,” LaMacchia told organic farmers.90 Rogers added, “None of that reduces the value of organic certification—it's just there are more things now on the table that we as buyers have to understand and address.”91

Historically, environmental regulations have often followed on the heels of development. In the US and EU, beginning in the second half of the 20th century, many kinds of pollution were halted and reversed, such as London's killer pea-soup smog,92 Rhine River pollution,93 LA smog,94 and acid rain in the eastern US.95 This trend has followed economic development around the world.

Although Western companies may have “outsourced their pollution” to the developing world in the short term, some argue that as these economies develop, their citizens will start demanding a healthier environment, leading to better environmental stewardship.96 The argument rests on a positive correlation between environmental stewardship and economic development once per capita income rises above some threshold—called the “environmental Kuznets curve.” (However, detractors have questioned the methodology that led to these conclusions.97) In 2014, China passed the biggest changes to its environmental protection laws in 25 years, creating plans to punish polluters more severely in order to limit pollution of water, air, and soil linked to economic growth.98 “The Chinese government is determined to tackle smog and environmental pollution as a whole,” said China's Premier Li Keqiang in 2015.99

Beyond the acts of individual countries, the global community has also shown it can address global environmental concerns. The most successful environmental campaign—tackling the depletion of the atmosphere's ozone layer—culminated with the 1987 Montréal Protocol (see chapter 4). This protocol provided coordinated standards to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and related ozone-depleting compounds.100

Tackling climate change may be tougher than any of these examples. First, few places in the world are experiencing deleterious effects directly attributable to climate change, despite attempts to link higher average temperatures and weather fluctuations to the possible trend. Long-term computer forecasts about the weather are just not as convincing as choking smog or measurable ozone holes and UV levels. Between 1998 and 2013, global surface temperatures reportedly failed to track the predictions of climate-change models (even though they were still rising), stoking skepticism about the models. Second, whereas CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals were used in only small segments of the economy (e.g., refrigeration and aerosol products), GHG emissions are linked to almost every facet of human activity (agriculture, electricity, heating, transportation, and industrial processes). Finally, CFC substitutes were relatively easy to find and commercialize. Substantially curtailing GHGs is much harder and much more expensive than eliminating ozone-depleting chemicals.

Nevertheless, many companies are starting to address the risks and opportunities of climate change. While some do so because it is “the right thing to do,” most do so to save money, reduce risks, or take advantage of new green opportunities. To mitigate future risks, Oxfam America created the Partnership for Resilience and Environmental Preparedness with collaborating companies—including Levi Strauss & Co., Green Mountain Coffee Roasters Inc., Starbucks, Swiss Re, and Entergy—to develop, refine, and share practices for resilience in the face of climate change.101 Certain regions are starting to take advantage of current and anticipated changes. For instance, agricultural productivity and total production is increasing in Greenland, reducing the country's reliance on expensive imported food.102 And in a twist of climate change fate, the melting of Arctic ice is enabling more sustainable transportation—ocean freighters can save almost 30 percent on time and fuel by sailing from China to Europe via the ice-free Arctic rather than by navigating the Suez Canal.103

Consumers in the developed world—especially young ones—may be seeking fewer material goods, potentially reducing the material impacts of future consumers on the planet. According to Julie Hennessy of Northwestern University, who researched millennials’ attitudes, “Nearly any possession you can think of stopped being an ‘of course’ and became a ‘hmmmm’ for millennials.”104 This is especially noticeable in the attitude toward car ownership105—in the United States, the proportion of 17-year-olds with drivers’ licenses fell to less than half in 2010, down from more than two-thirds in 1978 106—but it is not limited to automobiles.

Millennials are investing in “experiences” rather than “things,” which is why social networking, music services, YouTube, and the sharing economy thrive. Companies are responding by creating experiences—everything from sharing on Facebook to Walmart movie nights—shifting the material-intensive industrial economy toward a potentially less-resource-intensive service and information economy.

Consumption in the developed world may stop growing as standards of living rise and fertility rates drop. Already, some mature, high-consumption countries, such as Japan and Italy, are shrinking in population, and others would be shrinking without a steady influx of immigrants.107 Estimates suggest that sometime between 2050 and 2100 the world's population may plateau at 10 billion,108 although other estimates hint at continuing slow growth to anywhere between 9.6 billion and 12.3 billion by 2100.109 Both estimates include many caveats that may point to even lower numbers.

Large multinational companies that depend on global markets for both supply and demand to provide growth worry about potential disruptions or restrictions. “We thought about some of the megatrends in the world, like the shift east in terms of population growth and the growing demand for the world's resources. And we said, ‘Why don't we develop a business model aimed at contributing to society and the environment instead of taking from them?’” said Paul Polman, the CEO of Unilever.110 He even said, “I don't think our fiduciary duty is to put shareholders first.”111 In 2010, Polman committed Unilever to halving the environmental footprint of its products while doubling the size of its business.112 It is an eco-growth target—growing the company's top line while shrinking its environmental impact.

Business-oriented eco-growth, of the kind that Polman desires, requires a very broad, multifaceted portfolio of initiatives to address the various types of impacts and the multiple sources. Figure 13.1 depicts the basis on which corporations may foster eco-growth, divided into what the initiatives seek to do (and why), and who they are aimed to influence. As described in previous chapters, companies can use a variety of eco-efficiency, eco-risk mitigation, and eco-segmentation initiatives to improve performance on both financial and environmental performance dimensions.

Figure 13.1 The elements of eco-growth

Each initiative can contribute individually to eco-growth while protecting and enhancing the company's brand. By reducing costs, eco-efficiency helps a company become more competitive while simultaneously reducing its environmental impact. By reducing risks of disruption to supply or demand, eco-risk mitigation reduces potential costs, losses, brand diminution, and barriers to maintaining a social license to operate and grow. By developing and promoting “green” products, eco-segmentation creates a real option for scaling costly or speculative sustainability practices, for testing green product concepts, for extending the brand to new consumers, and for priming customers’ acceptance of sustainable products. As M&S's Barry said, “We are very much firmly in the view that sustainability is shifting from risk to opportunity, and that's happening very, very quickly.”

The who layer of the eco-growth pyramid sees these three types of initiatives spread inward and outward to align all the supply chain stakeholders that affect both a company's environmental impact and its financial performance. The story of sustainability is the story of supply chain management. As illustrated throughout this book, the lion's share of a company's environmental impacts—be it emissions, resource consumption, or other impacts—usually lies outside the company's four walls. Moreover, an impact in one part of the supply chain (e.g., energy for hot water to wash clothes) may only be addressable by a different part of the supply chain (e.g., a chemical ingredient supplier who can make effective cold-water detergents). Thus, addressing impacts at the most cost-effective point requires a company to take on an expanded role in its industry. This also involves cooperation and communications with—as well as the education of—customers, the media, NGOs, and governments to assuage concerns about the company's efforts to manage environmental impacts efficiently.113

As discussed in chapter 4, sustainability typically begins “at home” with reductions in the company's own footprint for manufacturing and overhead. Initially, these can be individual low-hanging-fruit projects such as replacing inefficient lights, recycling waste materials, or using fuel-efficient trucks. Achieving larger internal reductions might require more widespread efforts or more coordinated changes in product design, procurement, manufacturing, and marketing. Thus, if a company wishes to reach more aggressive sustainability goals, it will need to align a large fraction of its own employees with those goals. The eco-culture element in figure 13.1 refers to creating a corporate culture around sustainability similar to creating a corporate culture around any other strategic goal such as quality, safety, or service.

The challenge for large corporations is how to inculcate such a culture across the organization; the employees may span the globe, finding themselves in different time zones, legal frameworks, and national cultures. Eco-culture initiatives comprise both formal and informal practices. Formal practices include policies (including compensation), environmental KPIs, shadow prices of natural resources, and other rules set by the company's leadership. Informal practices include education; publicizing quick wins, challenges, and awards; and so forth. Such a culture encourages employees to watch for opportunities in their own and their coworkers’ daily activities in order to create or support environmental initiatives. “At Walmart, we're working to make sustainability sustainable, so that it's a priority in good times and in the tough times,” said Mike Duke, CEO, in 2009.114

Consider Apple CEO Tim Cook: When a shareholder group demanded Apple invest only in environmental measures that were profitable, Cook responded angrily, “When we work on making our devices accessible by the blind, I don't consider the bloody ROI. When I think about doing the right thing, I don't think about an ROI. If you want me to do things only for ROI reasons, you should get out of this stock.” Apple shareholders applauded Cook's outburst and voted down the group's resolution.115 Stories like Cook's angry response serve to polish Apple's green image, as well as foster a culture of service and sustainability among its employees.

As mentioned in chapter 4, however, Apple's green exterior hides a less green reality upstream in its supply chain, among its Asian suppliers (as well as in the use phase for its products). Glitzy brochures and triumphant claims aside, Apple is aware of the hidden carbon footprint hot spots in its supply chain. Beginning in 2008, Apple began training a growing number of suppliers’ managers and workers on a range of environmental and social issues (see chapter 5). To further reduce the carbon footprint of its suppliers, in 2015, Apple partnered with suppliers to install four gigawatts of clean energy, including two gigawatts in China.116 The company worked with its Asian contract manufacturers to change their manufacturing processes to increase usage of recycled aluminum and aluminum smelted using hydroelectric power. The company has also helped suppliers implement initiatives for energy eco-efficiency, water reduction, and waste reduction.117 “This won't happen overnight—in fact, it will take years—but it's important work that has to happen,” Cook pointed out in 2015.118

As with Apple, most companies have a large fraction of environmental impacts and risks that lie in their upstream supply chains. Thus they often attempt to align suppliers to environmental goals as described in chapter 5. These eco-supply alignment activities depicted in figure 13.1 include codes of conduct, transparency requirements, frequent audits, supplier education, economic incentives, and expectations that suppliers will push environmental objectives to the next tier of suppliers. Supplier alignment can target any of the three types of initiatives. Companies can align suppliers to eco-efficiency goals by requiring suppliers to report and reduce their energy use, carbon emissions, water usage, or other natural resource footprints. Supplier eco-risk initiatives might focus on prohibiting “zero tolerance” activities, such as deforestation (e.g., RSPO), particular pesticides (Whole Foods), or worker safety and work rules violations (IKEA and many others). Supplier eco-segmentation initiatives might involve certifications that materials or parts supplied allow the company to meet green label standards for its products. In many cases, however, effecting change in suppliers’ processes requires industry-wide collaboration through consortia such as the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC) or RSPO.

One can assess companies on their level of process maturity for the role of sustainability in suppliers’ management along the following scale (see figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2 Suppliers’ environmental management maturity model

Some companies manage their suppliers’ environmental performance on their own, whereas others enlist the help of a third party, such as an NGO, certification body, or industry body. Companies such as L’Oréal, IKEA, Starbucks, Nike, and Patagonia have different levels of sustainability management depending on the supplier type, as a function of the company's materiality assessment (see chapter 3) and supplier risk assessment (see the HP example in chapter 5).

A completely different element of supply eco-alignment is the attractiveness of sustainable companies to millennial recruits; in other words, the supply of human resources. As mentioned in chapter 10, many companies have seen evidence that millennials—who will be entering the workforce in large numbers in the second and third decades of the 21st century—are attracted to firms that practice social and environmental responsibility. These companies may attract a larger pool of applicants and therefore gain better employees. The competitive advantage created by such attraction is basic in that companies’ most important assets are their employees, and superior employees create superior returns.

Worldwide, industry consumes half of all energy produced. The other half of energy is consumed by the use of all the products created by industry. Pressure (and mandates) to reduce this total impact motivates companies to develop and market energy efficient products or change end-of-life disposal practices. To achieve this, companies combine new green products with marketing campaigns aimed at influencing consumers to buy and use them responsibly. Toyota made hybrid cars “cool” with the distinctive styling of the Prius and an aggressive marketing campaign. The carmaker has also attempted to influence consumers’ behavior after they buy the car. The Prius gives real-time feedback to drivers on their driving habits, including fuel consumption and separate “eco-scores” for the driver's starting, cruising, and stopping habits.119 Similarly, a range of companies, including detergent makers, appliance makers, apparel makers, and retailers, have tried to influence consumers to use cold water to wash clothing (see chapter 9).

Companies deeper in the supply chain also work to influence B2B customer behavior and product choices. Alcoa creates special lightweight alloys and products to improve the fuel efficiency of cars, trucks, and aircraft. BASF develops and markets specialty chemicals and materials for green product applications, which accounts for 23 percent of the company's sales (see chapter 8). These companies try to influence their customer companies to design and sell greener products, which (by no coincidence) are profitable for the suppliers of key materials needed to make these greener products.

A company's alignment efforts can go beyond its own upstream and downstream ends of the supply chain to encompass others who affect resource consumption and impacts. AB InBev ranks water stewardship among the most important issues for both its business and its stakeholders120 (see chapter 4). Although the beverage maker has worked to improve its own water use in places like Brazil, it recognizes that if the broader patterns of water use by others in the region are not sustainable, then AB InBev's access to water (or its social license to operate) might be disrupted. “With worsening droughts from the southwest United States to southeastern Brazil, scarcity presents enormous challenges that go beyond access, impacting the quality of health and socio-economic prosperity in our communities,” wrote Carlos Brito, CEO of AB InBev.121 This has motivated the brewer to go beyond efforts within the company and its supply chain, to take on a broader natural resource stewardship role in the region. These expanded eco-alignment efforts aim to harness the combined power of all players in an industry or region to work toward sustainability.

One element of AB InBev's water stewardship initiatives in Brazil focuses on restoration of the upstream areas of the watersheds surrounding the urban metropolis São Paulo. This work involves a complex public-private partnership with The Nature Conservancy, the area mayor's office, the Jaguariúna Bureau of the Environment, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, the Brazilian National Water Agency, and the Piracicaba, Capivari, and Jundiaí Watershed Committees.122 These efforts target reforestation of riverbanks to reduce erosion and help control flooding. They also include improving soil conservation practices in area farms: deploying 195 water retention ponds, terracing 540 hectares, and readjusting 17 km of rural roads.123 Watershed restoration in the region promotes better water retention in the greater São Paulo area. Not only does this help ensure continuity of water supplies, but it also reduces the threat of disruptions from flooding.

Another element of AB InBev's Brazilian water stewardship initiatives focuses on reducing water use by others, especially ordinary consumers, regardless of whether they drink the company's products or not. AB InBev and the Brazilian water utility Sabesp launched Banco Cyan (Cyan Bank) on Earth Day 2011. Twenty-six million consumers opened online accounts that help them track water usage, learn to conserve, and earn points toward discounts at online stores in Brazil.124

Between 1980 and 2010, total ton-miles of freight in the United States grew by 36 percent.125 Yet, at the same time, the percentage of the US GDP spent on logistics declined steadily from 15.7 percent in 1980 to 10.4 percent in 1995, and down to 8.3 percent in 2010.126 The logistics industry had become significantly more efficient, which also enabled global merchandise trade to surge from 27.7 percent of global GDP in 1986, to 33.9 percent in 1995, and to reach 46.9 percent in 2010.127

The main impetus for the reduced cost of logistics services was the deregulation of the US transportation industry, followed by transportation deregulation in the EU and other regions. This trend was augmented by high fuel costs and environmental considerations that spurred the development of fuel-efficient trucks,128 airplanes,129 and ships,130 as well as the adoption of fuel-saving operating procedures, such as slow steaming131 and speed regulators on trucks.132 Logistics facilities also adopted energy-saving devices, alternative energy sources, and reduced emissions technologies, all of which reduced costs. At the same time, better logistics management tools and processes (such as better coordination to minimize empty miles) reduced waste and cost, leading to higher efficiency and lower environmental impacts.

One of the most important trends that kept logistics costs from escalating with world GDP and the growth in international trade was the adoption of data capture, analysis, management, and communications tools. Digital information, besides directly replacing some manufactured print and music products, has also reduced the costs and, often, the environmental footprints of all manufactured goods. Timely information and precise control can help minimize the use of high-footprint expedited transportation; it can also lower safety stocks and help machinery perform optimally—all leading to both reduced costs and lower environmental impacts. When computers went from the desktop to the palmtop to embedded sensors with an always-on connection to the Internet, the enterprise management applications that efficiently ran administrative back-offices could be extended into the great outdoors where supply chains chiefly operate.

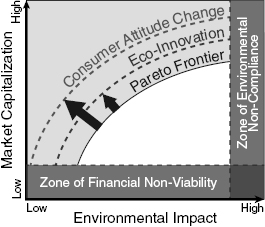

Once companies reach the Pareto frontier, the low-hanging fruit has been harvested. Decisions that led to better outcomes on both financial and environmental dimensions have already been taken, and at that point companies seem to be forced to make trade-offs between financial performance and environmental performance. But this frontier is only an absolute limit if decision makers have an unchanging set of options.

Fortunately, the world is not static. The set of options available to managers expands in two directions (see figure 13.3). First, innovation in the form of new management processes, new materials, and the inexorable advance of technology all expand the decision maker's space of options. Another source of innovation is suppliers, who may redesign or modify equipment to enable low-impact, high-efficiency, or low-risk manufacturing and transportation. Second, consumers’ changing attitudes toward green companies and products (whether owing to demand shaping by a company, a regulatory change, media influence, or external trends) may make investments in sustainability more attractive and allow for premium pricing and/or market share capture.

Figure 13.3 Expanding the Pareto Frontier

Such developments, when they come, allow companies to “push out” the Pareto frontier and create new opportunities to achieve both economic growth and a reduction in environmental impacts.

The common assertion that growth and environmental sustainability cannot coexist rests on two principle assumptions. The first is that growth—such as revenue increases—must require proportional increases in the material volume of products. But eco-efficiency innovations might reduce the amount of material in a product (e.g., concentrated detergent, lightweight plastic bottles, aluminum-frame cars, and ever-shrinking consumer electronics). Other innovations may increase the value of the product through improvements in performance or service (e.g., customization of products, “white glove delivery,” software bundled with products), leading to a higher price for a given quantity of physical product. Furthermore, changing consumer preferences might favor more services over owning more stuff. Finally, the Internet has enabled both the sharing economy and growing online markets for secondhand products, which means more people get to use a given product without the need to manufacture more of that product.

The second assumption is that higher material consumption necessarily means corresponding increases in environmental degradation. At first glance this assumption seems true; making a ton of cotton T-shirts seems to always require at least a ton of cotton, with all the negative impacts that growing cotton entails. However, innovations in irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides, and cotton breeding can reduce the environmental impact of that ton of cotton. Recycling by consumers might mean that the one ton of new T-shirts needs less than a ton of new cotton. Renewable energy initiatives might replace carbon-intensive power used in the harvesting, manufacturing, and transportation processes with carbon-neutral alternatives. Eco-risk mitigation initiatives might reduce impactful activities (such as deforestation), substitute low-impact materials for high-impact ones (such as Patagonia's Yulex wet suit described in chapter 11), or phase out toxins.

Examples of new products that break the more-products–more-impact relationship include the array of hybrid and electric automobiles and machinery, which reduce the carbon footprint during a product's use phase. A specific example is Cummins’ low-emissions diesel truck engines, which are cleaner, as well as more efficient and quieter, than the engines they replace.133 The new engines opened new markets for Cummins in Europe and elsewhere.

Innovations can extend to manufacturing processes, such as Coca-Cola's redesigned bottle-washing spray equipment that reduces water consumption (see chapter 4). Raytheon Corporation's response to the evidence of ozone depletion caused by cleaning chemical solvents is another example. The company replaced a CFC-based cleaning agent with a semi-aqueous, terpene-based agent that was not only reusable but also increased product quality.134 New manufacturing methods allow for radical redesigns of existing products to reduce their impacts (e.g., Nike's Flyknit shoe; see chapter 8). Finally, some companies might combine product and process innovations with new business models (e.g., Interface Carpet's cradle-to-cradle model; see chapter 8).

Regulations can affect many of these sustainability-related innovations, but they have to be correctly applied. Porter and van der Linde135 argue that regulations mandating the use of specific technologies (e.g., a particular emissions-control device) can limit innovation. In contrast, environmental regulations that focus on achieving a measurable outcome (e.g., a limit on emissions) can spur innovation, thus pushing the Pareto frontier outward.

Although product supply chains and consumers’ use of goods do require natural resources, the amount of resources required to produce value can decline. Ford switched from steel to aluminum to decrease weight and increase the fuel efficiency of its F-150 pickup truck.136 GE is investing $200 million to mass-produce ultra-lightweight high-performance materials to create higher-efficiency jet engines and gas turbines.137

Some of the greatest improvements in resource efficiency have taken place in consumer and business computing owing to Moore's Law. A modern-day tablet, such as an Apple iPad, has more processing power and functionality than a desktop PC of 20 years ago, yet it uses less than 1/10th the materials and 1/100th the electrical power. With the use of apps, a smartphone or tablet can replace dozens of previously separate consumer products (and their respective environmental impacts). Besides being a telephone, the device also acts as a camera, video recorder, walkie-talkie, GPS navigation aid, pocket calculator, wristwatch, game console, flashlight, hand mirror, appointment book, notepad, laptop, wallet, credit cards, and house keys, to name a few. The Internet, mobile networks, and digital delivery obviate most of the environmental impacts of manufacturing, distributing, retailing, and recycling of physical books, audio records, CDs, videotapes, DVDs, maps, and instruction manuals, as well as the furniture (bookshelves and filing cabinets) and floor space (and retail space) they formerly required.

In 2013, the UN reported that more people on Earth have access to mobile phones than toilets.138 With cellular data networks available to six billion people, any country has the potential to jump from a preindustrial level of development to a postindustrial information economy. African countries are building cellphone networks and skipping the landline phase; they are using mobile payments without building bank branches everywhere; and they are in the process of skipping the PC revolution in favor of smartphones.139

The growing availability of data and the declining cost (and increased accuracy) of sensors facilitates supply chain visibility—the ability to locate and track materials, parts, and products as they move around the world. Such operational visibility is critical for pharmaceuticals, food safety, sensitive defense parts, high-value products, and time-sensitive production and delivery processes. Companies invest in visibility for business benefits such as efficiency, reliability, and service that are enhanced by knowing where parts and products are at all times, anticipating delays, and allowing for better coordination of manufacturing and distribution activities.

Supply chain visibility systems can support tracking of hidden credence attributes, such as those associated with sustainability, by ensuring provenance. Companies can then use their operational visibility systems to manage and communicate sustainability information to those customers, consumers, and investors who want it, especially customers who must comply with government regulations (e.g., EU timber, US conflict minerals, among others). To communicate this information, companies can use online media, such as the interactive map Marks & Spencer created showing 1,230 suppliers in the retailer's food and apparel supply chains (which is reminiscent of Patagonia's Footprint Chronicles).140 Such visual displays are currently static, but one can imagine a future dynamic layer depicting real-time information. Downstream information sharing may also help in managing responsible use and end-of-life issues. For example, GE has installed sensors in its jet engines, locomotives, and other products that send information back to the company about product usage and performance.141 This enables GE to increase the operating efficiency, life span, and safety of its products, leading to both economic and environmental benefits.

On a more inspiring level, visibility can create a human connection between suppliers and consumers around the world, becoming a means by which rising standards of living foster rising concern for the environment. The near-universal availability of cellular phones142 means that virtually every farmer, supplier, trader, factory, transportation carrier, retailer, worker, and consumer in the world can be connected at all times. The same tools that let FedEx or UPS track a package from origin to destination may help Starbucks track coffee from a Costa Rican farm to a consumer's venti latte, connecting the bean grower with the cup sipper. Such connections can help personify the impacts of supply chains and help accelerate a reduction of environmental impacts at both ends of the chain.

The linear economy of the 20th century was easy to understand. Goods flowed in one direction: downstream from supplier to manufacturer to retailer to consumer, and on to a landfill. However, as recycling and reuse efforts expand, consumers and customers become suppliers. Downstream end-of-life waste management efforts create new supply sources of materials for the upstream end of the supply chain.

Governments are contributing to this trend by enacting Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulations (see chapter 7). These regulations include a combination of take-back requirements, disposal fees and deposit-refund schemes, recycled content requirements, and consumer education or labeling requirements. Between 1998 and 2007, more than 260 producer responsibility organizations that collect and/or recycle end-of-life products were established in Europe.143

Thus, government mandates and initial market forces are starting to shift companies (and supply chains) from the prevailing “take-make-dispose” paradigm to a “cradle-to-cradle” paradigm. Such thinking leads companies to adopt what EMC and Herman Miller (among others) call “design for disassembly.” EMC accepts returns of all its branded products (see chapter 7).144 Some returned products are reconditioned for internal deployment or donations, while others are harvested for remanufacturing. The company sends less than 1 percent of its postcustomer products and materials to landfills. Carpet manufacturer Interface Inc. went even further and changed its overall business model to obtain full control of its products throughout their entire life cycle (see chapter 8). Combined with innovative product design, Interface recovers, recycles, and reuses 98 percent of old carpet to make new carpet. “The circular economy has to be the better way forward. Every manufactured good in the future should be made so that it can be remanufactured,” said Sir David King, the UK Foreign Office's special representative for climate change.145

As Unilever's CEO Paul Polman said, “Sustainability is contributing to our virtuous circle of growth. The more our products meet social needs and help people live sustainably, the more popular our brands become and the more we grow. And the more efficient we are at managing resources such as energy and raw materials, the more we lower our costs and reduce the risks to our business and the more we are able to invest in sustainable innovation and brands.”146

At first glance, selling sustainability to business executives in the short term seems difficult. First, some executives might believe that the extent, timing, and impacts of climate change and other environmental risks are too uncertain to merit short-term investment. Second, they might believe that technological solutions will avert any potential catastrophe, as they have in the past, obviating the need to invest right now. Third, they might believe that long-term investment in sustainability does not serve the central short-term financial and competitive goals of the organization.

Nevertheless, even the most skeptical executive would still pursue some level of eco-initiatives; these initiatives are rooted in a business rationale that is independent of an executive's personal beliefs about the long-term future of the environment. The business rationale for eco-efficiency depends only on the inevitable cost savings of using fewer natural resources. The business sense behind eco-risk mitigation depends on the beliefs of the NGOs, media, and regulators who might attack non-green companies. It is also a rationale for recycling to protect against price increases and shortages. Finally, the business motivation for eco-segmentation depends on the beliefs of those consumers who might prefer green goods. It also socializes the organization to a possible future in which supplying green products will be required. Thus, even the most ardent climate change skeptics are likely to pursue some minimum level of sustainability efforts because those initiatives reduce costs, lower short-term risks, and reposition a company for potential changes in consumer attitudes or regulations.

Implementing sustainable practices falls on the shoulders of supply chain managers. The design and management of supply chains plays a dominant role both in creating and in mitigating the environmental impacts of sourcing, manufacturing, transportation, usage, and disposal of all products that sustain and improve peoples’ lives. Supply chain management processes are caught in the crossfire between the tensions of economic performance, natural resource stresses, societally acceptable practices, and regulation. The debate regarding the acceptable trade-offs between human standards of living and prevalence of jobs on the one hand, and levels of environmental impacts on the other, has already begun, and it will affect the constraints and opportunities that companies face. Some inventive companies will find clever and profitable ways to beat these supposed trade-offs—innovating their way into eating the proverbial cake while having it, too. In 2011, Nike CEO Mark Parker told shareholders, “I believe that any company doing business today has two simple options: embrace sustainability as a core part of your growth strategy, or eventually stop growing.”147