Chapter 7

EVERYDAY LIFE IN THE POTTERIES

LITERATURE AND THE ARTS

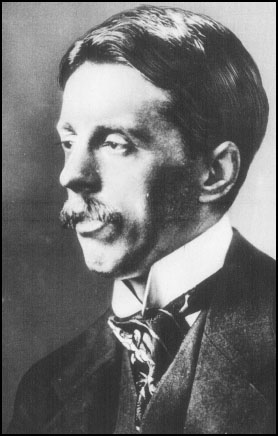

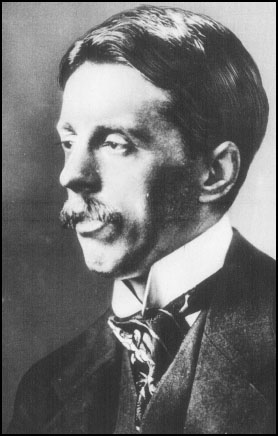

Although he only spent a little over twenty years in the Potteries, Arnold Bennett’s time there framed his world view and provided inspiration for many of the characters, events and places in his writing. In his novels and plays, this son of a Hanley solicitor sketched in graphic detail life in ‘the five towns’, highlighting many of the pressure points and injustices in late Victorian society (see box below). The cruelty of the Chell workhouse; the bawdy behaviour in the public houses; the avarice of the factory owners; the drudgery of life in the potbanks and down the mines: all were captured in Bennett’s writings and always with a poignant sympathy for the working class.

Bennett was not unique in writing about the Potteries. A succession of writers has sought to disentangle the area; some more sympathetically than others. Visiting in 1884, Charles Dickens observed that although not a pleasant sight, the area was not ‘in any way spoilt by its potworks, grotesque and ugly though many of them are’, as they provided the basis for ‘busy towns and thriving settlements’. But by 1908 J.F. Foster saw the Potteries as a byword for the ultimate industrial desolation, referring to its ‘inch-thick greasy mire beneath the tread’, ‘small and wizened houses’ and ‘everthing [sic] sombre, wretched, blighted’. George Bernard Shaw and George Orwell in the 1920s and J.B. Priestley in the 1930s all found little to appeal and sought to blacken the Potteries in print.

Artists who have worked in conventional media include: Charles William Brown (1882–1962), an acclaimed amateur painter who spent his working life in the mines; and Reginald Haggar (1905–88), who taught at the Stoke and Burslem Schools of Art.

It is, of course, in ceramics that local artistic expression is most readily found. Much of the ware was decorated by hand and those employed to do the work had to be not just skilled technicians but highly accomplished and creative artists. Women could make their mark in this field just as well as the men, and could even use design as a route to management positions. The success of Clarice Cliff in this respect has already been noted (see Chapter 2). Charlotte Rhead followed a similar route. Born in Burslem in 1885, she worked for several pottery firms before joining H.J. Wood, where she brought out a number of designs. One of these, Florentine, is still to be found in quantity. She later became a director of the successor company, Wood & Sons. More often than not, however, all that is known about these highly talented people – male or female – is their name. Potteries.org profiles the work of leading companies, including some individual artists. The Barewall Gallery in Burslem has collections by twentieth-century North Staffordshire artists and ceramicists (www.barewall.co.uk).

The North Staffordshire Field Club provided a focus for many early photographers, both amateur and professional, including William Blake and J.A. Lovatt. It was founded in 1865 to study the natural history, geology, industrial history, folklore and local history of North Staffordshire. Its first president was industrialist and banker James Bateman, FRS. The organization made a significant contribution to the intellectual life of the area, in particular through making an early photographic record of the changes affecting the Potteries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (see Chapter 1). Its records and publications, including membership lists, are held at Staffordshire Record Office [D6104] and other libraries.

Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, Staffordshire County Museum and Keele University all have substantial collections by local photographers (see Chapter 1). GENUKI has a list of professional photographers working in Staffordshire (www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/STS/ Stsphots.html). Other sources for information on photographers (often little more than lists) are: www.earlyphotographers.org.uk; and www.victorianphotographers.co.uk.

ARNOLD BENNETT: SON OF THE POTTERIES

Arnold Bennett was born in May 1867 in Hanley, where his father Enoch Bennett became a solicitor. After working for his father for a short while, he went to London as a solicitor’s clerk and experimented with journalism. After winning a literary competition in 1889, he was encouraged to take up journalism full-time and joined the editorial staff of Woman magazine. After 1900 he devoted himself entirely to writing, dramatic criticism being one of his foremost interests.

Arnold Bennett, 1867– 1931. (Public domain)

His first novel, A Man from the North, was published to critical acclaim in 1898, followed in 1902 by Anna of the Five Towns, the first of a succession of stories set in the Potteries and displayed his unique vision of life there. Many of the locations in Anna of the Five Towns, Clayhanger and other Bennett novels correspond to actual locations in and around the district. There was ‘Bursley’ (Burslem), ‘Hanbridge’ (Hanley), ‘Knype’ (Stoke), ‘Longshaw’ (Longton) and ‘Turnhill’ (Tunstall). The ‘forgotten town’ was Fenton, which has no literary twin in Bennett’s prose.

From 1903 to 1911 Bennett lived mostly in Paris, producing many novels and plays as well as working as a freelance journalist. During this time he continued to enjoy critical success. On a visit to America in 1911 he was acclaimed more than any visiting writer since Dickens. He returned to England to find the Old Wives Tale (published in 1908) being hailed as a masterpiece.

By 1922 he had separated from his French wife and taken up with the actress Dorothy Cheston, with whom he lived until his death from typhoid in 1931. His ashes are buried in Burslem Cemetery.

Although Arnold Bennett spent most of his life outside the Potteries, he never forgot the debt he owed to his birthplace. It gave him a unique setting for so many of his novels, a setting which he enhanced with his penetrating description of people and places. He is commemorated by a plaque at his childhood home in Waterloo Road, Cobridge; and by a statute outside the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery.

Keele University has a substantial Arnold Bennett archive, including many of his personal papers, literary manuscripts and pictorial material (www.keele.ac.uk/library/specarc/collections).

THEATRE, VARIETY AND CINEMA

For such a small area, the Potteries has had a surprisingly large number of theatres and other entertainment venues over the years. With the exception of Fenton, by the late nineteenth century each of the Six Towns had at least one theatre. As with other aspects of Potteries history, this is at least partly explained by competition between the towns, each attempting to outdo the other with larger and ever more expensively appointed venues.

The first permanent theatre in the area is thought to have been the Theatre Royal in Newcastle-under-Lyme which opened in 1788. Josiah Spode and Josiah Wedgwood were among the shareholders. Having been successful for many decades, it closed towards the end of the nineteenth century and later found use as a cinema.

A permanent venue within the Six Towns took much longer to establish. Several attempts by local businessmen to form theatres during the 1820s came to nought. Instead, local people relied on travelling theatres that toured the country. Entertainment was also found in the public houses. The Sea Lion in Hanley, for instance, is said to have had a large yard behind the inn that played host to plays and circuses. Music was a prominent feature inside the pubs and inns of the time and eventually spawned the music hall. Larger concerts and performances are known to have been held in the old Hanley Market.

Poster for Laurel and Hardy’s appearance at the Theatre Royal, Hanley, 1952. (Staffordshire Past Track)

Eventually, in 1852 the Royal Pottery Theatre opened in Pall Mall, Hanley. It had been converted for theatre use from a lecture hall known as The People’s Hall, which in turn had previously been a Methodist chapel. It soon became known more generally as the Theatre Royal.

This was the first of many theatre, concert and music hall venues opened in the area during the last half of the nineteenth century. Neale (2010) lists 28 such venues in the Six Towns during this period: 13 in Hanley; 5 in Burslem; 5 in Longton; 4 in Stoke; and 1 (the Prince of Wales Theatre) in Tunstall. Some of these many theatres were successful; others were financial disasters bringing bankruptcy or worse on their owners. Several have mysteriously burnt down and only a very few can be seen in the city of Stoke-on-Trent today.

The opening of a new theatre or music hall was the cause of much civic pride. The grand opening of the Empire Varieties Theatre, New Street, Hanley, in 1892 was attended by aldermen, county councillors and officials from neighbouring towns. Addressing the audience, the manager, Fred Gale, as quoted in the Era, 19 March 1892, explained that:

It was intended to bring before their audiences some of the best talent it was possible to secure. No expense would be spared to attain this object. The entertainment they meant to bring before the Hanley public from week to week was one to which any man might bring his wife, sister, or mother, without fear of being chastened on his return home. The management would make it their business to put down severely anything in any way objectionable.

The opening programme featured: The Voltynes, clever bar performers; Turner and Atkinson, tenor and baritone vocalists; Miss Carlotta Davis, a burlesque actress and skipping rope dancer; Percival and Breeze, sketch performers; Howlette’s Marionettes, described by the Era as ‘extremely diverting’; and Mr Sam Jesson, a singer. The scene would have been repeated, week after week, at venues across the Potteries, providing all-too-brief moments of light relief for industrious workers.

Neale (2010) surveys the history of Stoke-on-Trent’s theatres, concert and music halls, and information on the main venues is presented at Matthew Lloyd’s website, www.arthurlloyd.co.uk, dedicated to the music-hall star Arthur Lloyd. Local newspapers carried notices and reviews of performances similar to those quoted above, which may mention theatrical ancestors (see Chapter 1). These, as well as specialist theatrical newspapers such as the Stage, the Era and Music Hall & Theatre Review, are available at the British Newspaper Archive (www. britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

The STCA has an extensive collection of historic theatre and concert programmes. As well as the major theatres, the collection includes smaller, informal venues such as amateur productions put on in church and village halls. A handlist is available in the STCA Search Room. Of particular note are the collections relating to the Theatre Royal and Grand Theatre, Hanley [SD 1145, SD 1259, SD 1326] and the Mitchell Memorial Theatre, c. 1943–50 [SD 1662].

Collections with a musical orientation include: North Staffordshire Symphony Orchestra, 1904–2006 [SD 1352, 1384 and SA/COPE]; City of Stoke-on-Trent Choral Society, 1928–82 [SD 1579]; Potteries Gramophone Society, 1930–47 [SD 1695]; and the English Folk Dance & Song Society, North Staffordshire Branch, 1921–76 [D5104].

Potteries.org has a history of the Porthill Players, an amateur dramatic and musical society founded in 1911.

HOLIDAYS AND RECREATION

Wakes Weeks

In the eighteenth century there was no entitlement to paid holidays. Time off was limited to certain festivals and saints days which were recognized by the Church. In the Potteries these eventually evolved into a week-long annual holiday known as The Wakes. Shops closed and people took off on foot, by train or other means to enjoy the festivities.

Wakes week at Trentham swimming pool, c. 1950.

At Trentham Park the Duke of Sutherland threw open the gates of his estate and laid on entertainment (another episode referred to by Charles Shaw in When I Was A Child). In 1850 as many as 30,000 people visited the Park on the annual ‘Trentham Thursday’. The revelry often lasted for the first four or five days of Wakes Week, or until the workers ran out of money. Even then, many chose not to return to work.

Initially there were three separate Wakes celebrations. Burslem Wakes was held during the week following the Nativity of St John the Baptist on 24 June. Tunstall Wakes was held in late July to celebrate St Margaret, to whom Wolstanton parish church is dedicated; and the Stoke Wakes focused on the first Sunday in August. Around 1880 it was decided that a single Wakes Week for the whole district would be less disruptive and the timing of the Stoke Wakes was adopted. By the early 1900s Wakes Week had turned into an annual fortnight holiday.

Although some people respected the religious origins, for most the Wakes were a time of fun and jollity, offering escape from the drudgery of everyday life and work. Boxing rings, music, acrobatics and gambling were all in evidence, as well as wheelbarrow races and team games. Dog and cock fighting were popular and continued to be organized furtively long after they were outlawed. The prevalence of alcohol and the inevitable drunkenness that followed led the Church to complain that the Wakes were nothing but an excuse for hedonism. Employers were not happy at the disruption to production. Temperance groups, Sunday schools, Church leaders and manufacturers organized alternative activities – galas, tea parties, picnics and trips to the countryside – in an attempt to bring the Wakes under control.

It was social progress rather than prescriptive regulation that curtailed the Wakes’ worst excesses. From the 1840s the railways allowed Potteries’ workers to travel further afield, opening up new locations such as Rudyard Lake in the Churnet Valley. This was promoted by the North Staffordshire Railway Company following the opening of the Churnet Valley line in 1849. During Stokes Wakes Week in August 1850 nearly 200 people arrived at Rudyard Lake by train to enjoy boating and picnic parties. Within a few years grand regattas were being held on the lake. One of those making the trip in 1863 was John Lockwood Kipling, a pottery designer from Burslem. He met his future wife, Alice Macdonald, there and they named their son, the novelist and poet Rudyard Kipling, after their meeting place.

Another beauty spot brought within easier reach by the railway was Mow Cop, which became a tourist attraction and not just a place of religious pilgrimage (see Chapter 4). Annual fetes at places such as Keele Hall and Leek were also popular.

Public Parks

While the annual Wakes Week provided welcome respite, demands were also growing for open spaces closer to home. In 1879 the Duke of Sutherland advocated a public park on land he was developing around Longton. The plan was opposed initially but in 1887, after the election of a new Mayor, was eventually accepted. The Duke donated 45 acres for the scheme, to be known as Queen’s Park, and a public subscription was launched to meet the set-up costs. At the opening ceremony in July 1888, the Duke observed: ‘We all know how necessary lungs are for the human frame. Open spaces are quite as necessary to those who toil much indoors and in a smoky town.’ In the Potteries, with its slagheaps and smoke-laden atmosphere, fresh air was increasingly recognized as a precious commodity.

As so often in the Potteries, the other towns followed suit. Hanley unveiled the first section of a 100-acre site in 1894, though the park was not fully opened until Jubilee Day 1897. Burslem Park, complete with ladies’ and gentlemen’s reading rooms, was opened in 1893. Other civic parks opened at Etruria (1904), Northwood (1907), Tunstall (1908) and later at Fenton (1924).

The popularity of public parks during the Victorian and Edwardian periods is difficult to comprehend today. It was not uncommon for crowds of 10,000 or more to visit Burslem or Hanley park on a Sunday. Boating, fishing and skating (during winter months) were all popular, as well as simply ‘promenading’ in front of one’s peers. Organized activities had to be paid for, however, so the poorer sections of society still found themselves excluded.

Sports Clubs

Sport provided a welcome, albeit brief, release for those who worked in the mines and the potbanks. Men and boys would kick a ball around in the street or on waste ground, and later in the blossoming public parks. As in many working class towns, there was a fierce rivalry for fans’ affections between local football teams. In the Potteries the rivals were ‘City’ (Stoke City, otherwise known as ‘the Potters’) and ‘Vale’ (Port Vale, known as ‘the Valiants’). For much of their existence the two clubs have played in different leagues and so have rarely met, but the rivalry was (and remains) real nonetheless.

The origins of Stoke City FC are deep and not entirely agreed upon. Some accounts say it was founded in 1863 by apprentices from Charterhouse School while serving as apprentices at The Knotty (North Staffordshire Railway Company). The first recorded match was in October 1868 when a team called Stoke Ramblers and consisting largely of railway employees played at the Victoria Cricket Club ground. In 1878 the Ramblers amalgamated with the Stoke Victoria Club to become Stoke FC and moved to a new athletics ground nearby. In 1888 the Potters were heavily involved in the formation of the Football League and were founder members for its inaugural season. The Potteries connection was further strengthened by the siting of the League’s office at 8 Parkers Terrace, Etruria (later to become 177 Brick Kiln Lane). Port Vale is almost as old, having been formed – according to club records – in 1876 in Burslem.

Stoke City FC, 1877–8. (Public domain)

STANLEY MATTHEWS: THE POTTER WITH THE GOLDEN TOUCH

No one has come to immortalize the Potteries’ sporting prowess like Sir Stanley Matthews. The first professional footballer to be knighted, Matthews is one of the most renowned players of modern times. His professional career covered some thirty-three years, much of it playing for Stoke City.

Matthews was born in 1915, in a terraced house in Seymour Street, Hanley, the third of four sons of local boxer Jack Matthews (who was known as ‘The Fighting Barber’ of Hanley). He first played for the Potters in 1932 and remained with the club until 1947. After fourteen years at Blackpool, he returned to city in 1961 until his retirement as a player in 1965, by which time he had made almost 700 League appearances. He helped Stoke to the Second Division title in 1932–3 and 1962–3. Following a short stint as Port Vale’s general manager between 1965 and 1968, he then travelled the world coaching enthusiastic amateurs.

During his career Matthews gained respect and admiration far beyond regular football supporters. When in 1938 it was mooted that he might be moving to another club, there was a public outcry in the Potteries. Employers complained that their workers ‘were so upset at the prospect of losing Matthews that they could not do their work!’. Despite playing in nearly 700 league games, he was never booked. The plaque outside his birthplace at 89 Seymour Street denotes him as ‘Footballer and Gentleman’.

He died in February 2000, just after his 85th birthday, and his ashes were buried beneath the centre circle of Stoke City’s Britannia Stadium. He is commemorated in a statue outside the ground.

Horse-racing was another popular pastime. The first properly laid out racecourse in the area was on Knutton Heath near Newcastle. Having failed to come to an agreement to hold their own races on the Newcastle course, in 1823 race-goers in the Potteries set about organizing their own race meeting. This was to be held on the Thursday and Friday of Stoke Wakes Week and 47 acres of land was leased from the Wedgwood family to establish a new course. A thousand pounds was spent laying out the course and building a large stand for spectators. The first race meeting was a huge success. The Staffordshire Advertiser reported that the committee had put on a varied programme, which included a foot race and a prison bar match as well as horse races. By the early 1830s the races at Etruria were attracting over 30,000 spectators and competitors from across the Midlands.

Finney Gardens in Bucknall became an important sporting venue in the late nineteenth century. Originally a 16-acre market garden flanking both sides of the railway track, from the 1860s grand galas and horse races began to be held there. By the 1890s a cricket ground and athletics ground had been established.

Edwards (1996) has further details on boxing, horse-racing and professional football within the Potteries.

Sport is not well represented in the SSA catalogue. Record series that may throw light on family members’ sporting endeavours are: North Staffordshire Referees Club, 1913–2005 [SD 1466]; Longton Swimming Club, 1929–36 [SD 1455]; Burslem Working Men’s Club, 1906–97 [SD 1706]; and North Staffordshire and District Cricket League (recent) [SD 1714]. The National Football Museum in Manchester holds extensive archives of Football Association and Football League records and is able to answer enquiries relating to relatives who have played the game at amateur or professional level (www.nationalfootball museum.com/collections).

PUBS, INNS AND BREWERIES

Pubs and inns have always played an important role in the life of the Potteries. Initially these were rural alehouses and inns: an ‘alehouse’ was an ordinary dwelling where the householder served home-brewed ale and beer, whereas an ‘inn’ was generally purpose-built to accommodate travellers. By the mid-eighteenth century larger alehouses were becoming common, while inns beside the major highways grew in grandeur and new ones sprang up to serve the stage coaches.

Very early photograph of the George Hotel, Swan Square, Burslem, the site of the Chartist riots. (Courtesy of thepotteries.org)

The sixteenth-century Greyhound Inn at Penkhull is one of the oldest in the district: for many years it hosted the Court of the Manor of Newcastle-under-Lyme. The Castle Hotel was one of many coaching inns in Newcastle. The origins of the Pack Horse at Longton go back to the time when Longbridge was a scattered hamlet in the Fowlea Valley between Newcastle and Burslem. Later, on the opposite side of Newcastle Street, the Duke of Bridgewater was built alongside the Trent & Mersey Canal when the former hamlet, its name changed to Longport, was expanding rapidly as a result of the new waterway. Josiah Wedgwood and others are known to have met at the Leopard (another coaching inn) in Burslem in 1765 when planning the canal.

Public houses reflected the communities they served and in the nineteenth century this meant there was strict stratification. Charles Shaw, writing in the 1890s, recalled that, in Tunstall, beerhouses were ‘for the common heard [sic], but, the [Sneyd Arms] hotel and the Lamb were for the gentlemen’. The Colliers Arms beerhouse in Moorland Road, Burslem was noted, in 1864, as being ‘a house of resort for the loose characters of the town’, while around the same time another beerhouse in High Street was known to harbour prostitutes. The Coachmakers Arms, Lichfield Street, Hanley is probably the best surviving example of a nineteenth-century Potteries beerhouse.

Victualling has always been a highly regulated trade. From 1522, a person wishing to sell alcoholic drinks had to apply for a licence from the Quarter or Petty Sessions, and from 1617 licences were required for those running inns, hence the term ‘licensed victualler’. A loosening of regulations during the 1820s and 1830s led to a significant increase in the number of licensed premises, as a result of which drinking in public houses became much more acceptable. From the 1880s a more ostentatious form of public house design began to emerge. One of the best examples is the Golden Cup Inn, in Old Town Road, Hanley, which is now Grade II listed.

The temperance movement was born in reaction to what many saw as ‘the demon drink’ affecting the working classes. Many such initiatives were led by Nonconformists who saw the fight against the evils of alcohol as part of their Christian mission. One of its leaders in the Potteries was Jeremiah Yates, a well-known Chartist, who ran a temperance coffee house (also referred to as a temperance hotel) at Mile’s Bank, Hanley. Wherever they could, campaigners took over beerhouses and public houses and converted them into temperance halls, as happened with the Sutherland Arms at Longton during the 1870s. The temperance movement persisted into the twentieth century. The Potteries, Newcastle and District Directory of 1907 lists three temperance societies in Burslem alone: Church of England Temperance Society (Burslem Auxiliary), Burslem Temperance Society and Sons of Temperance, Wedgwood Sub-Division.

Grindley (1993), Edwards (1997) and Edwards (2014) all survey the history of pubs in the area. Potteries.org has extensive listings, photographs and pub histories. The Stoke-on-Trent Historic Buildings Survey, available at the PMAG, provides details of many of the more notable pub buildings in existence at the time the study was made in the 1980s.

Licensing Records

Victuallers’ documentation is to be found in various categories of Quarter and Petty Sessions records. Landlords had to declare that they would not operate a disorderly pub and to enter into certain obligations before the court could issue a licence; these oaths are generally catalogued as ‘recognizances’ or ‘bonds’. Landlords that failed to adhere to these requirements would appear on charges of ‘keeping a disorderly house’ and so appear under the criminal headings of the court’s records. The SRO has a limited series of licensed victuallers registers from the period 1628–1792 [Q/RLv]. Later licences and related hearings are listed in the general Quarter Sessions or Petty Sessions series (see Chapter 5). Stoke, Burslem and Fenton came under the Pirehill North Magistrates Court for licensing purposes and that court’s records contain a long series of licensing applications (1872–1984) [SRO: D5272/1/3].

There are not many temperance-related records for North Staffordshire. The SRO has a small collection relating to the Newcastle-under-Lyme Methodist Temperance League, 1877–83 [D6275/1], as well as plans for Old Temperance Hall, Union Street, Leek, 1921 [6474/1/1]. General record series relating to Nonconformist congregations may also detail their activities in this regard.

Other sources for records of pubs and publicans include newspapers (e.g. brawls, festivities), land records (deeds, tithes, enclosures), rate books, fire-insurance records and apprenticeship agreements. Information on tied pubs and their owners can be found in the records of brewery companies, and in photographic collections.

MARKETS, SHOPS AND FOOD

Being a product of the industrial era, markets came relatively late to the Potteries. Historically, Newcastle-under-Lyme had been North Staffordshire’s main commercial centre. A market had been held there since the twelfth century and the burghers of Newcastle gained much power as a result (see Chapter 8). With the rise of the Potteries, markets were established within the Six Towns from the mid-eighteenth century. As with other areas of civic life, the nature and extent of the markets became a source of rivalry between the towns.

In Stoke a market was held in the original town hall, erected in 1794. Built by subscription and administered by trustees, it was a typical building of the period, with an arcaded market below and a meeting room above. By 1818 there was a Saturday market, but in 1834 this was overshadowed by the market at Hanley, so, in 1835, a new market hall was built. In Burslem, a covered meat market opened in Market Place, next to the town hall, also in 1835, where it remained for many years. Longton market has operated from sites in or near Market Square (now Times Square) since 1802.

Large-scale ‘retail experiences’ came late to the Potteries. For much of the nineteenth century shops were limited to the traditional trades – bakers, chemists, haberdashers, ironmongers, etc. Michael Huntbach opened the district’s first department store in Lamb Street, Hanley in 1876, having bought up the surrounding properties. By the time of his death in 1910, Huntbach’s store occupied more than 20,000ft² and employed 300 staff. Other emporiums were Bratt & Dyke at the corner of Stafford Street and Trinity Street, and McIlory’s in Hanley.

Like many working class areas, the co-operative movement, which advocated the principles of self-help, was an important feature of trading in the Potteries. One of the first stores opened in Newcastle Street, Burslem in 1901. It became the basis for the Burslem Cooperative Society, Stoke-on-Trent’s most successful mutual commercial enterprise. Initially 200 joined, each subscribing 4s. By 1932, the Burslem & District Industrial Co-operative Society had 50,000 members, 112 shops and capital of more than £1 million.

Oatcakes are a type of pancake made with oatmeal that has been a staple for the working classes in Staffordshire for over 200 years. Although not unique to Staffordshire (they are found also in Cheshire, Derbyshire and parts of North Wales), oatcakes have become synonymous with the county and especially Stoke-on-Trent. In the nineteenth century they were sold from the front rooms of the Potteries’ terraced houses. Some of these houses evolved into more permanent shops, with a hatch through which the oatcakes were sold on the street.

The Staffordshire oatcake looks nothing like its Scottish cousin. It is made from a batter comprising oatmeal, flour, milk and water that is ladled on to a griddle. The final result resembles a French crepe. Today all manner of exotic fillings are added to the modern oatcake, though the purists will tell you that cheese and bacon are the original and best. Sausage, eggs and tomatoes are also popular fillings. Sambrook (2009) provides an authoritative history of this local delicacy.

Lobby, a type of thin stew, was another Potteries staple. Often it comprised little more than potatoes and was served in an ironstone bowl with a cloth tied tightly round the top. This, too, is not unique to Stoke-on-Trent, but a version of the lobscouse recipe that is supposed to have been introduced to these shores by the Vikings. Writer Paul Johnson mentions it in his childhood memoir of Stoke in the 1930s (Johnson, 2004). Referring to The Sytch, a huge polluted waste ground populated by potbanks, mines and iron furnaces, he describes how the workers:

used to take their midday ‘dinner’ with them. It was called Lobby and was a thin stew . . . It seemed to me a horrific kind of meal but it was no doubt nourishing and they liked it. All carried their supply of Lobby to work and never thought of eating anything else. There were no canteens. The master potters said, ‘Can’t afford ’em. Dust want to send us down Carey Street?’ [meaning bankruptcy]

Key sources for shop-owning ancestors include trade directories (look for advertisements as well as directory listings), rate books, and property records such as deeds. Commercial disputes may have ended up in court and be reported in the newspapers. Shop-owners frequently went bankrupt and so ended up in the civil courts or in debtors prison. Photobooks, such as Hanley Then and Now (History Press, 2012), serve to show not only the shops and their owners, but the diversity of products sold.

ORAL AND COMMUNITY HISTORY

The Potteries’ mode of speech is sufficiently distinct in terms of grammar, pronunciation and vocabulary to qualify as a dialect rather than just an accent. In days gone by, the fact that people spent most of their time in close proximity with others in the same social class – either in the potbanks or the mines – is likely to have helped to reinforce and preserve the dialect. In these days of global media and Estuary English it is less pronounced than it used to be, but any visitor to the area is still sure to notice.

Experts believe that the North Staffordshire dialect may derive from Old English, as spoken by the Anglo-Saxons. This may explain the very round vowel sounds: for example, the vowel ‘o’ followed by an ‘l’ is pronounced ‘ow’ as in towd (told), owd (old), cowd (cold), and gowd (gold). The local word ‘nesh’ – meaning soft, tender or to easily get cold – is derived from the early English, ‘nesc’, or ‘nescenes’; and ‘slat’ – meaning to throw – is from the Old English ‘slath’ (moved). ‘Mithered’ means to be worried about something; ‘sneaped’ is to be upset; and ‘famished’ is to be very hungry. Other dialect words are: ‘surry’, meaning friend; ‘brazzle’, meaning hard (and/or hard-faced); ‘farrantly’, meaning good or amiable; and ‘clemmed’, meaning starving. One of the most noticeable phrases for the visitor is use of the term ‘duck’ as a greeting (for a man or woman), although this is found in other areas of the north and east of England and is not unique to North Staffordshire.

Wilfred Bloor’s ‘Jabez’ character by artist W. Walker. (Keele University)

In recent years, archives and heritage institutions have placed increasing emphasis on so-called ‘community history’, collecting and documenting ordinary people’s recollections and experiences of their communities. The Staffordshire Dialects Project on the BBC Stoke & Staffordshire website has accounts of people’s accents and dialects in use across the county, collected under a 2005 project called Staffordshire Voices (www.bbc.co.uk/stoke/ voices2005). Unfortunately, the audio links from this site no longer function. Potteries.org has a guide to the North Staffordshire dialect, as well as memories of life in Stoke-on-Trent based on interviews with local people and published accounts (www.thepotteries.org/ memories).

Wilfred Bloor (1915–93) was born and bred in the Potteries and spent his working life researching the effects of dust in the pottery industry. His interest in different dialects, and especially that of North Staffordshire, led to his creation of the character Jabez. Under the pseudonym ‘A. Scott’ he wrote over 400 Jabez tales in Potteries dialect for the local Sentinel newspaper. The Wilfred Bloor Papers at Keele University comprise his manuscript and typescript articles, cuttings, correspondence and audio cassettes from the 1960s to the 1990s (www.keele.ac.uk/library/specarc/collections/).

The Sentinel maintains an extremely popular ‘nostalgia’ section, offering a look back at times gone by in Stoke-on-Trent, North Staffordshire and South Cheshire from the 1890s to the 1990s (www.stokesentinel.co.uk/all-about/way-we-were). It has spawned an active Facebook group (www.facebook.com/sentinelwaywewere). Nostalgic Memories of Stoke on Trent and the Potteries (True North Books, 2015) is one of many books that aim to capture such memories. Cockin (2010) is a collection of folklore and ‘oddities of human life and character’ from the Potteries and surrounding area.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Booth, John, Hanley Then and Now (History Press, 2012)

Cockin, Tim, Did You Know That . . . 6: Facts About The Potteries, Stone, Newcastle (Malthouse Press, 2010)

Edwards, Mervyn, Potters at Play (Churnet Valley Books, 1996)

Edwards, Mervyn, Potters in Pubs (Churnet Valley Books, 1997)

Edwards, Mervyn, Potters in Parks (Churnet Valley Books, 1999)

Edwards, Mervyn, Stoke-on-Trent Pubs (Amberley Publishing, 2014)

Gibson, Jeremy and Judith Hunter, Victuallers Licences: Records for Family and Local Historians (3rd edn, Family History Partnership, 2009)

Grindley, Joan-Ann, A Pint-sized History of Stoke-on-Trent and District (Sigma Leisure, 1993)

Johnson, Paul, The Vanished Landscape: A 1930s Childhood in the Potteries (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 2004)

Neale, William A., Old Theatres in the Potteries (Lulu.com, 2010)

Sambrook, Pamela, The Staffordshire Oatcake: A History (Palatine Books, 2009)