![]()

The surface of a leaf is an inhospitable place by any standard. It is subject to extremes of temperature, both high and low, from hour to hour and day to day. Moisture is supplied irregularly; drenching rain one moment may be followed by desiccation in the heat of a summer afternoon the next. All the time it is unprotected from the damaging components of sunshine. Food is in short supply, being available only by the parsimonious leakage of nutrients through the cuticle from the cells beneath, or by chance windfalls of pollen and dust deposited by wind and rain. And as if this were not enough, it may be bombarded by a variety of poisons – sulphur dioxide and other pollutants from cities and factories or salt spray carried on the wind around the coast. Like many hostile places, however, this bleak world is teeming with life.

The phylloplane (the surface of the leaf) and the other above-ground surfaces of the plant – stems, buds and flowers – are inhabited by a whole range of fungi and bacteria, mostly saprophytes, all fully adapted to cope with every environmental extreme and all competing for space and food. No group is more successful in this battle than the ubiquitous powdery mildew fungi, obligate biotrophic members of the order Erysiphales within the Ascomycota. They are important pathogens of a wide range of cultivated and wild plants.

The word ‘mildew’ has been in the English language a long time, being derived from mildéauw, an Old English word meaning honeydew. It now refers to any fungal growth on any surfaces, living or dead. Thus clothes and leather goods become mildewed by saprophytic Penicillium or Aspergillus spp. in damp climates, and sheets become mildewed by dark coloured saprophytes if left damp too long. Plants too may show white fungal parasitic growths, referred to as ‘downy mildew’ if caused by parasitic members of the CHROMISTA (see here) and as ‘powdery mildew’ if caused by members of the Erysiphales. The superficial grey-white vegetative mycelium, conidiophores and conidia of the Erysiphales usually make infected plants obvious, looking as if they have been partially whitewashed or dusted with talcum powder (Plate 5a). High summer is the time to see these powdery mildews at their best, both in the garden and in the field, especially if the weather has been dry.

LIFE ON THE LEAF SURFACE

The hyphae of the powdery mildews are confined to the surface of the plant, with all the stresses that this implies, and they maintain themselves on this hostile environment principally by sending haustoria into the epidermal cells of the host to tap the food and water available there. Some have also developed the capability of germinating under drier conditions than those which suit other parasites. For example the conidia of Erysiphe polygoni, now restricted to isolates infecting Polygonaceae, but formerly considered to be a pathogen of many wild and cultivated species (the problem of naming powdery mildews will be dealt with below) not only germinate without the presence of free water but can even germinate in a relatively dry atmosphere, and the same is true of the grapevine mildew, Uncinula necator. On the other hand Sphaerotheca pannosa (rose mildew) (Fig. 8.1) and Podosphaera leucotricha (apple mildew) need a saturated atmosphere for germination, whilst other powdery mildews appear to behave somewhere between these two extremes.

There are many observations that suggest that having germinated, many powdery mildews are able to grow in dry conditions, and are thus xerophytes. Observations on the powdery mildew of rubber trees (Oidium heveae) suggest that rain is required to start an epidemic but that the epidemic subsequently develops most rapidly if a period of fine weather follows rather than a period of continuous rain. Many other powdery mildews appear to flourish and spread in warm dry weather, such as Uncinula necator on vines (Vitis vinifera) mentioned above, and Sphaerotheca fuliginea on members of the cucumber family. But one can lay too much emphasis on this, for there are also observations to suggest that fine weather during the day needs to be accompanied by dews at night for the spread of species like Podosphaeria leucotricha on apple. It is easy to demonstrate the damage that free water can do to the conidia of powdery mildews, but it is also possible to observe a reduction in the spread of these fungi when the weather becomes very hot. Also there are biological factors such as the nutrition of the host, its age and its stage of development, which influence the ease of infection by different species. It is clear that we are dealing with a group of fungi, some of which have xerophytic features but certainly not all.

The different genera of the Erysiphales are identified by the details of their asexual and sexual reproductive processes. All have the typical life cycle of the Ascomycota (see here).

FIG. 8.1

Sphaerotheca pannosa causing powdery mildew of rose (cultivar ‘Albertine’) in Cambridge, England. Note the mycelium covering almost the entire surface of each leaf and the distortion of the infected leaves. (D.S. Ingram.)

The conidia, the non-motile asexual spores, are budded off in succession from a short, often flask-shaped, mother cell (the conidiophore) attached to a hypha on the leaf surface (Fig. 8.2). In this process the single nucleus of the mother cell divides repeatedly to provide one haploid nucleus to each conidium. The mature conidia, which contain large reserves of water, are resistant to drying out over short periods and are easily detached, to be dispersed on the wind to new hosts.

FIG. 8.2

Conidia of Erysiphe graminis, cause of powdery mildew of grasses and cereals (Gramineae); note the flask-shaped mother cell. The oldest conidium, at the tip of the chain, is approximately 28 μm long. (Illustration by Mary Bates.)

There are small differences between the conidial stages of different species, and these can be used for identification purposes. Sometimes the individual spores remain attached to one another to form long visible chains, as in Erysiphe graminis (powdery mildew of grasses and cereals) (Fig. 8.2); indeed, there is evidence from spore traps that this fungus is often distributed as unbroken chains of conidia. Sometimes conidia fall off one by one as they are formed and do not form chains, as in E. polygoni. The mother cell may be swollen and barrel-shaped (E. graminis), or scarcely distinguishable from the young conidia (Sphaerotheca spp.). The fully developed conidia themselves vary in shape from egg-like (E. graminis) to pointed or dumbbell-shaped (Phyllactinia spp.). The presence or absence of vacuoles or fibrosin bodies (bundles of elongated fibres of unknown nature) and oil droplets are also distinguishing characteristics.

The sexual bodies, the ascocarps, are roughly spherical cleistothecia with no neck or natural opening, containing irregularly-shaped sac-like asci (Fig. 8.3). The number of asci varies according to genus: one large one in the case of Sphaerotheca and Podosphaera, several in Erysiphe, Uncinula, Microsphaera and Phyllactinia. Melanin, a dark fatty substance that impregnates the walls, helps to prevent water loss and may also protect the developing ascospores from the harmful components of sunlight. Ascocarps are very resistant to environmental extremes, enabling the fungus to survive over winter. Being almost 1 mm in diameter, the ascocarps are usually visible to the naked eye as black or dark brown specks, rather like specks of dust, on heavily infected plants (Plate 5).

Close examination with a lens or low power microscope reveals that the ascocarps are frequently ornamented with grotesque branches or appendages that grow out from the surface, the different shapes and branching patterns of these structures being characteristic of different genera. In Microsphaera alphitoides (powdery mildew of oak) (Fig. 8.5), for example, they branch repeatedly at the tip to form patterns resembling a cluster of old-fashioned H-shaped television aerials; in Uncinula necator they are hooked at the tip; whilst in Podosphaera leucotricha they are boringly straight. Their function is not known with any certainty, although it is possible they have a role in dispersal.

FIG. 8.3

Diagrammatic longitudinal sections (not to scale) of ascocarps of powdery mildew genera to illustrate ascus shape and number, and the form of the appendages: (a) Erysiphe, (b) Sphaerotheca; (c) Microsphaera; (d) Podosphaera; (e) Uncinula. (Drawn by Mary Bates after Ellis and Ellis (1997).)

The cleistothecia open irregularly to reveal the asci, in some cases by an equatorial split which removes one half leaving the asci protruding from the matrix in the other, like eggs in a nest.

TAPPING THE AQUIFER

In describing the ecological niche that the mildews occupy some clues to their behaviour have emerged. Individual conidia or ascospores land on the leaf surface, germinate and rapidly send out a germ tube. In some species, such as Erisyphe graminis, the first formed germ tube is very short, and by attaching itself to the leaf surface appears to act as an anchor for the spore. Then a second germ tube emerges from the other end of the spore, grows and swells to form an appressorium, which also sticks to the leaf surface. Finally an infection peg emerges from the underside of the appressorium and penetrates the underlying cuticle and cell wall. In other species there is a single germ tube with an appressorium at its tip. If the appressorium were not securely attached to the surface of the leaf the hydrostatic pressure within the host cell would make penetration impossible. The entry of the infection peg is facilitated by the secretion of enzymes such as cutinases, and perhaps cellulases, which soften the cuticle of the leaf surface and the underlying cell wall to allow the peg to grow into the cell.

It is this rapid penetration of the host cell, to tap its reserves of water and nutrients, that allows the fungus to flourish in its inhospitable environment. On entering the cell the infection peg comes into contact with the plasmalemma. Immediately changes begin to take place. The swollen infection peg grows to become a characteristic lobed or fingered haustorium, which occupies a large part of the cell. The plasmalemma of the host cell grows rapidly to accommodate this structure and becomes thicker than normal. It is inhibited from producing cell wall materials, and this prevents the haustorium from being walled off. Nevertheless, layers of material containing protein and lipids are laid down at the interface between the plasmalemma and the haustorium wall. This ‘sheath matrix’ may aid the exchange of nutrients and other substances between host and parasite. The haustoria are easily seen by stripping off the epidermis of an infected leaf and examining it with a microscope.

The timescale of infection is interesting. In Erysiphe graminis f.sp. hordei, the form that attacks barley, germination and the formation of an appressorium takes about 9–10 hours. Penetration occurs after 10–12 hours, and then the growth of the haustorium begins. The finger-like extensions of the functional haustorium in this species are found after 18 hours, and at that point a second hypha begins to grow out from the appressorium onto the surface of the leaf. This branches repeatedly, and an approximately circular colony forms. Secondary haustoria are formed after about 50–70 hours. Eventually approximately one haustorium is produced for every three hyphal ‘cells’ of the fungus and more than one haustorium may be found in each epidermal cell of the host.

Hyphal growth and branching usually leads eventually to the whole leaf surface being covered by a network of grey-white mycelium. Grey-white mycelium is characteristic of most powdery mildews, but in some the hyphae darken as they age, as with the American gooseberry mildew, Sphaerotheca mors-uvae, which attacks gooseberries in Britain (Plate 5).

Just to make things difficult, not all powdery mildews behave in this way. An exception is Phyllactinia guttata, which infects hazel (Corylus avellana) in Europe and other species in the USA and Asia (Fig. 8.6). The hyphae grow from the leaf surface, through the stomata and into the mesophyll. Another is Leveillula taurica, powdery mildew of xerophytic Mediterranean species and of crops grown under warm dry conditions, such as pepper (Capsicum spp.), cotton, and globe artichoke (Cynara scolymus); here the vegetative mycelium grows mostly within the leaf. Infection takes place through the stomata rather than directly through the cuticle, and the hyphae then sporulate on the leaf surface. Were the original mildews like this, or is this a secondary development in response to particular conditions? At present we do not know.

In the epiphytic forms, close examination of the neck of the haustorium where it passes through the plant cell wall shows a thickening resulting from the deposition of a ring of fatty, suberin-like material. It is tempting to think that this functions as a mechanism for isolating the haustorial wall from the wall of the external mycelium, to prevent evaporation or leakage. Further speculation demands more understanding of the qualities of the wall in the surface mycelium, especially if the mechanism for survival in the hostile environment of the leaf surface is to be understood.

Each haustorium contains a nucleus and is metabolically very active. Haustoria not only remove water, sugars and other nutrients from the host but also affect the host cells. In some instances, for example, chlorophyll is retained by infected cells after the normal onset of ageing, giving a green island effect (Plate 5b); this may be caused by the secretion by the fungus of plant hormones such as cytokinin. The fungus, presumably by way of the haustoria, also stimulates an increase in the rate of flow of nutritive material from the mesophyll of the leaf to the epidermal cells in contact with the fungus.

Powdery mildews have been valuable in studies of the mechanisms involved in the uptake of sugars by haustoria, most experiments being made with Erysiphe pisi, the powdery mildew of pea (Plate 5a). Two approaches have been used. In the first, haustorial complexes, each consisting of the haustorium itself, the surrounding host plasmalemma and the sheath matrix between this and haustorial wall, were isolated. Once isolated, the neck of the haustorium becomes plugged as a result of the wound responses of the fungus, so the only route into the haustorial complex is through the semipermeable host plasmalemma surrounding it. These isolated complexes were then immersed in various solutions containing radioactively-labelled sugars and the pattern of uptake monitored. In other experiments, thin sections of infected, living leaves were stained with chemicals that react with and highlight the molecular ‘pumps’ responsible for the transport of sugars across membranes. The results from these experiments (Fig. 8.4) suggest that the presence of a powdery mildew haustorium in a host epidermal cell leads to activation of the inward facing pumps on the plasmalemma of the cell. Thus the infected cell begins to accumulate sugars from surrounding, uninfected cells. The only part of the plasmalemma on which the pumps are not activated is that surrounding the haustorium. If these pumps were activated sugars would be pumped out of the haustorium because the section of the plasmalemma enclosing the haustorium is turned back on itself. As sugars build up in the infected cell a concentration gradient between the cytoplasm and the haustorium is established. This leads to simple diffusion of sugars across the host plasmalemma that encloses the haustorium, into the sheath matrix. From there they are pumped into the haustorium by another set of inward facing pumps on the membrane surrounding the fungal cytoplasm inside the haustorium itself.

FIF. 8.4

Suggested location and orientation of molecular ‘pumps’ in a host epidermal cell containing an haustorium of an Erysiphe species. Note the inward facing pumps on the host cell membrane (a) and the inner haustorial membrane (b) (arrows), and the lack of pumps on the section of host cell membrane invaginated to accommodate the haustorium (c). (Illustration by Mary Bates, based on Manners and Gay (see Callow, 1987).)

THE DIVERSITY OF SPECIES AND THE DISEASES THEY CAUSE

Powdery mildews on wild plants

Very few wild plants escape attack by mildews. Few of them have been studied in depth and the taxonomy of the fungi involved is unsatisfactory, for two reasons. Firstly, most occur only in the anamorph phase and where ascocarps are present they are usually hard to find, being confined to a particular part of the plant’s growth cycle; many of the herbs of the European flora develop infection in midsummer, but the cleistothecia are not seen until late summer or autumn. Secondly, the taxonomy of the mildews is still evolving. Many of the forms on wild plants were assigned in earlier classifications to one or two species with wide host ranges such as Erysiphe polygoni and E. cichoracearum, but later investigations have separated particular groups from these. Thus E. trifolii has been distinguished from E. polygoni because it is confined to members of the clover and pea family (Leguminoseae) and has distinctive morphological features; similarly E. fischeri on Senecio spp. was originally part of E. cichoracearum, widely distributed on members of the daisy family (Compositae). However, the taxonomic literature that delineates the differences between these more closely defined species is only available in the major botanical centres, so it may be difficult for the amateur to make a precise identification even if the sexual stage is present, although Ellis and Ellis (see Bibliography) offer a guide to sound identification.

A different problem is highlighted by the species E. polyphaga. This apparently attacks plants as unrelated as members of the families Cucurbitaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Begoniaceae, Compositae and Crassulaceae. E. cichoracearum occurs on a number of distinct genera of the Compositae and E. heraclei attacks several species in widely separate genera in the Umbelliferae. The difficulty here is accommodating these biotrophs with wide host ranges in the model of pathogenicity developed in Chapters 2 and 3. If recognition is, as seems certain, such an important element in the delicate relationship built up between a biotrophic pathogen and its host, between parasitic gene (s) for virulence and avirulence and host gene (s) for susceptibility and resistance, then how can one genetic form of a pathogen attack many different hosts? The simplest explanation would be that the fungus either consisted of a mixture of appropriate pathogenic forms or was heterokaryotic (containing a mixture of nuclei of differing pathogenic potential), pathogenic races or forms being selected from the population of spores landing on the host surface. We do not have the experimental evidence to confirm or deny this hypothesis, but naturalists interested in plant diseases could go some way to solving the problem by studying the host range of some of the commoner mildews of wild plants. Inoculating them with single spores would be difficult, but serial inoculation of a single host to see if, after several passages on one host, it would transfer to another, would be simply done and of great interest.

There is no space to discuss in detail the many mildews found associated with wild plants. There are, however, three that are particularly worthy of notice. The oak mildew (Microsphaera alphitoides) (Fig. 8.5) is widely distributed in the north temperate zone and is seen every year on Quercus robur and Q. petraea in Europe. It is probably the only oak mildew in Britain; Microsphaera extensa, which may be part of the same taxonomic complex, has a similar distribution but is not recognised in Britain. Both are rare in the USA, but M. lanestris is widespread on oaks in North America and Asia. M. alphitoides is most easily seen on young shoots; their leaves are often distorted and look as if they have been painted with whitewash. The disease was not recognised in Europe until 1907, and was thought to have been imported from the USA, but this is by no means certain. In its early years the cleistothecia, with their much branched appendages and several asci, were rarely seen and were not identified in Britain until 1946 (Fig. 8.3). Attempts have been made to relate their occurrence to physical factors such as high temperatures and drought, or to the later appearance of a sexually compatible strain. In terms of taxonomy, history and physiology there is much still to discover about the oak mildews.

FIG. 8.5

Microsphaera alphitoides, cause of powdery mildew of oak (Quercus sp.) in Aberlady, East Lothian, Scotland. (D.S. Ingram.)

The hazel mildew Phyllactinia guttata ( = P. corylea, the nomenclature is confused) (Fig. 8.6) is probably widely distributed in the north temperate zone and is especially noticeable on young coppice shoots of hazel late in the year. Its immediate interest lies in the presence of some mycelium inside the leaf and in the apparently eccentric but superbly functional design of the cleistothecia (Fig. 8.7). Cleistothecia are found on the lower surface of the hazel leaf with the top facing downwards. The appendages are very distinct, being long and straight, pointed at the end and with a swollen base. In addition, on the surface of the cleistothecia facing downwards are several secretory structures like small shaving brushes which secrete a large blob of mucilage. In autumn, as each cleistothecium dries out, the irregular thickening of the appendage bases causes them to bend towards the leaf and lever the whole structure off the leaf surface, so that it falls to the ground. As it falls the appendages act like the flights of a shuttlecock, ensuring that the cleistothecium lands with the blob of mucilage facing downwards; this sticks it firmly to the surface of the leaf litter on the ground, where it remains all winter. In spring, as the new leaves of the hazel emerge, each cleistothecium splits around its equator and the upper half (originally the base, when attached to the underside of the leaf) hinges back, carrying with it the asci, each containing two ascospores. The ascospores are then shot out from the tip of each ascus to infect new leaves and begin the cycle again. Morphologically similar fungi apparently infect other plants such as chestnuts (Castanea spp.) and oaks (Quercus spp.)

The sycamore mildew Uncinula bicornis (U. aceris) commonly occurs in the north temperate zone on a variety of Acer spp.; in Britain it is found on field maple (A. campestre) and sycamore (A. pseudoplatanus), and less commonly on Norway maple (A. platanoides). The mycelium and conidia occur in obvious patches late in the year, mostly on the lower surface but sometimes on both sides of the leaf, and spectacular green islands develop around the lesions as the leaves senesce in autumn (Plate 4b). The cleistothecia can often be found on the undersides of newly fallen leaves in the green island area, by which point no very obvious vegetative mycelium can be seen. They have beautiful appendages which branch dichotomously twice at the ends, with tips that curl over like ram’s horns (Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.6 Phyllactinia guttata, powdery mildew of hazel (Corylus avellana) from Elibank, Peeblesshire, Scotland. (C. Prior, Royal Horticultural Society.)

FIG. 8.7

Diagram of an ascocarp of Phyllactinia guttata, cause of powdery mildew of hazel (Corylus sp.). (a) An ascocarp attached by its base to the underside of the host leaf; note the secretory structures at the apex (pointing downwards) and the bulbous appendages. (b) The downward flight of the ascocarp; note that the appendages have bent to lever the ascocarp off the leaf, and act as flights; also note the blob of mucilage formed by the secretory structures. (c) The ascocarp attached to the ground surface; the base, with the asci attached to it, has hinged back ready for ascospore release. (Ilustration by Mary Bates, based on illustrations and descriptions by Webster (1980) and Ellis and Ellis (1997).)

Powdery mildews on cultivated plants

There are several other species that occur on both wild and cultivated plants. Where serious damage to the cultivated hosts has led to economic loss there has been intensive study of the disease. Examples include the powdery mildews of arable crops and their wild relatives, vines, hops, fruits and garden ornamentals.

Erysiphe graminis is probably the commonest of the powdery mildews, occurring on wild and cultivated grasses and on cereals (Fig. 8.8). The disease almost always develops on young plants, where the thick white powdery masses of fungal mycelium, bearing conidia, may be seen forming patches on leaves and stems. The host is not killed by the infection but, as the season advances and the disease extends, infected plants become increasingly debilitated and brown areas of dead and dying cells form around the margins of the lesions, although shaded leaves may develop green islands.

To all intents and purposes E. graminis looks the same whatever its host. Research has shown, however, that it exhibits a high degree of physiological specialisation with respect to host range. Firstly, as a species it is restricted to hosts within the grass family (Gramineae). Secondly, morphologically identical but physiologically distinct forms (formae speciales) are restricted to particular genera and species within that family. Within the formae speciales there may be further specialisation into races capable of attacking particular cultivars of the host, according to the combination of resistance genes carried by the host and the virulence/avirulence genes present in the pathogen (see Chapter 3).

It is difficult to estimate the crop losses caused by Erysiphe graminis, but they are large. Reliable figures for experiments comparing yields of sprayed and unsprayed barley show a loss in excess of 20% in unsprayed plots. The average estimated loss for all crops year on year is 5 to 6% for barley and 2 to 3% for wheat, but farmers know that when resistant cultivars are overtaken by a new pathogenic race the crop yield may be dramatically reduced and they make strenuous efforts to control the disease with sprays, which is expensive in itself.

E. graminis forms cleistothecia without clearly defined appendages on the older leaves and stubble of cereal plants in late summer (Fig. 8.8). These discharge and infect autumn-grown cereals and plants that have germinated from dropped seed, which carry the disease over to the next spring. Any cleistothecia that remain over winter are generally without fertile asci. We shall return to E. graminis later.

Of the several other members of the Erysiphales that cause disease in crops E. betae is the most studied. It attacks sugar beet crops everywhere, but is most damaging where the weather remains dry for long spells and where temperatures are high throughout the growing season. Thus it causes major problems in the southwestern USA, eastern Europe, North Africa and western Asia, but is not significant in temperate climates such as those of Britain and the eastern seaboard of the USA. Forms of the same fungus are to be found on wild species of Beta but not on other members of the beet family (Chenopodiaceae). Other common Erysiphe spp. occurring on crops include E. pisi on peas and other legumes (Plate 5a) and E. cruciferarum on members of the family Cruciferae including swedes, turnips and rape grown for oilseed and fodder. E. cichoracearum, as its name implies, attacks chicory (Cichorium intybus) and is also found on endive (Cichorium endivia), lettuce and globe artichokes (Cynara scolymus), becoming especially damaging on these and other crops in the daisy family in warmer climates; in British gardens it is a severe problem on Aster spp. (e.g. Michaelmas daisies).

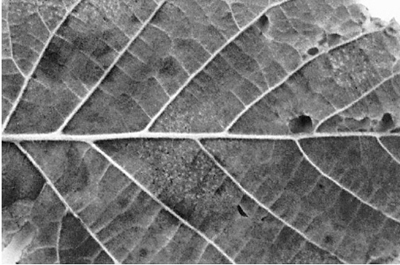

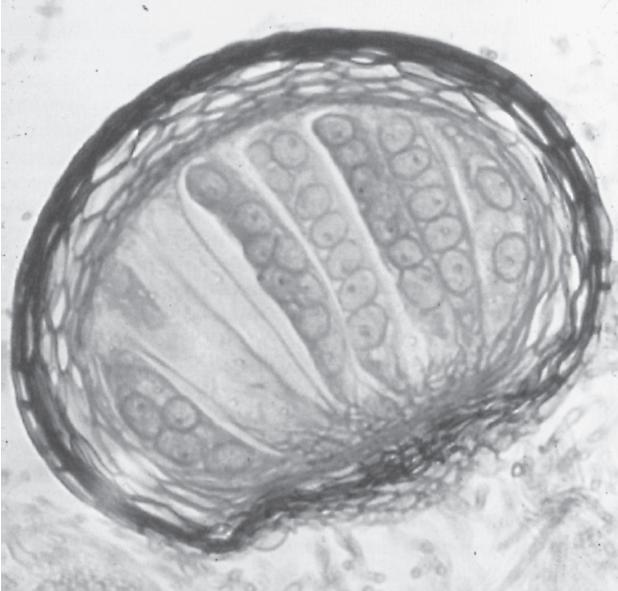

FIG. 8.8a

FIG. 8.8b

Erysiphe graminis, cause of powdery mildew of grasses and cereals (Gramineae): (a) surface mycelium and ascocarps on a leaf sheath of winter oat (Avena sativa) in Cambridge, England; (b) vertical section of an ascocarp showing the thickened wall and elongate asci, each with eight ascospores. (Photograph (a), D.S. Ingram; photograph (b) H.J. Hudson, University of Cambridge.)

Another major disease is the powdery mildew of vines, caused by Uncinula necator. This fungus appeared in epidemic proportions at about the same time as the potato blight (1842–5). It was first recognised in the United States and turned up in a glasshouse in Margate, England, in 1847, from whence it spread to the vineyards of Europe and threatened the wine industry, a disaster too awful to contemplate. It should not be confused with the downy mildew of vines, Plasmopara viticola, which was first imported from America in 1878 and which can also cause serious disease problems.

Uncinula necator, although capable of surviving very dry conditions, is not as dependent on warmth and dryness for its spread as are some other mildews. If left unchecked it soon covers all the leaves, debilitating the vines and affecting their growth and productivity. It also spreads to the fruits, stopping growth of part of the fruit wall, leading to bursting. The disease is often seen in Britain on ornamental vines, and is especially easy to spot on those with purple leaves.

The conidia are borne singly on the conidiophore, although in still conditions small chains may occasionally form. The sexual stage is rarely found and indeed was unknown in Europe until 1892; the cleistothecia have appendages with curved, forked ends. Ascospores are discharged in the spring, but by far the greatest source of overwintered fungus lies in buds infected with vegetative hyphae.

From thoughts of wine we move to beer. There are many similarities between the life cycle of the vine mildew and Sphaerotheca humuli (S. macularis), the powdery mildew of hops (Humulus lupulus). The characteristics of the cleistothecia in the genus Sphaerotheca are the long sinuous appendages and the presence of a single ascus. The disease has been recognised in British hop growing from about 1700, although the causal organism was not recognised until the late nineteenth century. It also occurs frequently on wild hops. The importance of the disease for the hop industry lies in the general debility of a severely affected crop. In addition, the pathogen often multiplies on the fruiting branches in late summer, which may lead to premature ripening of the ‘cones’, a reduction in the production of the flavouring principle known in the trade as alpha-acid and a consequent reduction in the appeal of the hops to buyers, who are greatly influenced by the appearance and smell of the cones in the hand.

There are a number of interesting aspects to this disease. It is widespread in Britain, mainland Europe and the eastern states of America. Hop-growing in the eastern USA, which suffered severely from epidemics of the disease in the early twentieth century, has probably for this reason been overtaken by the spread of the crop to the Pacific northwest, where the mildew does not yet seem to occur. Its significance worldwide has varied as other hop diseases such as downy mildew (Pseudoperonospora humuli – see here) and wilt (Verticillium albo-atrum – see here) have become important in their turn, but it is still recognised as a serious threat to production.

Survival of the pathogen in the absence of hop plants is in part by cleistothecia, which mature the eight ascospores in the single ascus over winter and discharge them in spring when the young foliage is emerging. The vegetative mycelium also persists over winter in external buds on the crowns of the hop stools. In the spring these give rise to heavily infected shoots, which initiate the spread of powdery mildew in the hop garden. Interestingly, the significance of both of these sources of inoculum has increased with the adoption of labour-saving methods in hop cultivation. In more labour-intensive days, infected buds were recognised and cut out; the cultivation of the soil then resulted in the burial of infected debris. Nowadays, with the replacement of cultivation by minimal tillage methods, infective debris with viable cleistothecia often accumulates around the bases of plants and this leads to an increase in infection.

Powdery mildews of fruits can be seen in almost any garden. Podosphaera leucotricha on apples has already been mentioned, its only method of survival over winter being within the dormant buds. It is more troublesome in some climates than in others, and in Britain is particularly severe, causing distortion and even death of heavily infected leaves. Mildew on soft fruit is caused by a number of different species. On strawberry the fungus is Sphaerotheca macularis, and on raspberry it is possibly a forma specialis of the same species. The most spectacular soft fruit infection, however, is that of the American gooseberry mildew (Sphaerotheca mors-uvae) on Ribes uva-crispa (Plate 5c). This fungus, which is indigenous on various Ribes spp. in the USA, was introduced into Europe via Northern Ireland in 1900. It attacks young shoots and leaves in the spring and then moves to the developing fruit, which is first covered with white sporulating mycelium, then becomes felted and black. This mycelium, despite its ugly appearance, can easily be rubbed off, demonstrating the surface nature of the mildew as well as the lack of structural damage to the host cells, as one would expect of a biotroph. Cleistothecia develop on leaves and stems and the fungus also overwinters in the terminal buds. The latest formed cleistothecia on shoots appear to be the most important for the release of ascospores in the spring. The fungus also attacks red, white and blackcurrants, especially the latter. There is in addition a European gooseberry mildew, caused by Microsphaera grossulariae, which occurs on leaves late in the season and is generally innocuous.

Powdery mildews are also widespread on ornamental plants grown in gardens, and in hot dry summers whole herbaceous borders may be afflicted. We highlight here just two that will easily attract the attention of the naturalist. The most striking is the rose mildew, Sphaerotheca pannosa. This occurs in a number of guises. Infection is most obvious and growth of the fungus most luxuriant on the shoots of wild roses (Rosa spp.) and on cultivars that bloom several times a year. In the old floribunda variety ‘Frensham’, for example, the flower stems and buds may be covered with a profuse growth of the fungus while the leaves on the rest of the plant are scarcely affected. In other cultivars the mycelium is not very obvious on the leaves or stems but, as the plant matures, patches of felt-like (pannose) mycelium consisting of a creamy layer of thickened hyphae appear. It is in these that the cleistothecia are formed. They lack appendages and contain a single large ascus with eight ascospores. The patches of pannose mycelium are often around the thorn bases or on the maturing fruit. Indeed, we can recognise certain genotypes in the wild rose population in Scotland by the striking pannose mycelium on the ripening ‘hips’. Cleistothecia are known to overwinter and release spores in the spring, but again mycelium surviving in buds is responsible for much of the carry over of infection. The release of the conidia follows a diurnal rhythm probably conditioned by changes in relative humidity, with the greatest release and dispersal taking place at about noon on a rainless day, reducing in the afternoon and at night.

Our second example is powdery mildew of Rhododendron. This disease is instructive because it is at an early stage in its development. However, we have some way to go before we feel secure in our knowledge of it. The first problem it poses is one of identity. In the mid-1950s some diseased rhododendrons in the glasshouses of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh were found to be infected by a mildew in the anamorph (Oidium) phase. No sexual stage was present. As far as could be ascertained, the fungus responsible was exterminated. In 1955 powdery mildew was identified on rhododendrons in Australia, and again no sexual stage was present. No more mildew was reported in Britain until 1969, when it appeared once more on plants in the Edinburgh glasshouses, this time on Rhododendron zoelleri. These plants had been introduced from New Guinea the previous year, and the supposition was that the fungus had been introduced with its host, since careful examination suggested it was different from the earlier examples in Edinburgh and Australia.

The history since then is of the identification of at least two types of Rhododendron mildew: one similar to Sphaerotheca pannosa (the rose mildew), on glasshouse rhododendrons; and one similar to Erysiphe cruciferarum (a powdery mildew of the cabbage family), on outdoor rhododendrons (Fig. 8.9). This last has spread to nearly all Rhododendron collections in Britain, and probably the same species is also present in New Zealand; the situation in Australia and Japan awaits clarification. Powdery mildew of Rhododendron has been found in the USA, mostly of a different type and thought perhaps to relate to Microsphaera azaleae, although two other types have possibly been recognised there as well.

FIG. 8.9

Erysiphe cruciferarum-type on Rhododendron stenophyllum at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Scotland. Note the chlorosis and distortion of the infected leaves. (S. Helfer, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

The reason for concern regarding the taxonomy of the pathogen is that we cannot be sure of the exact relationship between these various isolates, nor do we know whether their chance introduction to other countries might complicate the problem of control. Moreover, although the British isolates have been equated with Sphaerotheca pannosa and Erysiphe cruciferarum, this is on the flimsiest of morphological evidence and it is impossible at present to extrapolate any of our knowledge of these organisms to the situation in Rhododendron mildew.

The effects of infection are various. In some Rhododendron spp. shoots and leaves are obviously infected, often yellowing and dropping off the plant, and the typical mildew mycelium can be seen. In others the effects are less obvious and limited infections on the undersides of leaves produce dark lesions on the upper surface, often persisting in the older leaves and sometimes causing defoliation. The degree of damage varies from species to species, sometimes causing massive leaf loss and death of the plant, sometimes being hardly noticeable. R. ponticum, the pernicious weed of many natural ecosystems is, ironically, relatively resistant to infection.

DIVERSITY WITHIN SPECIES

Probably the best documented variation within species of powdery mildews is that of Erysiphe graminis on cereals. The presence of formae speciales on different cereal and grass species has already been mentioned. Although there is occasional evidence of mildew crossing over from grass hosts to cereals, the specialised forms on cereals seem to be fairly strictly confined, with no crossover among wheat, oats and barley. This is well shown in New Zealand, where powdery mildew has always been present on wheat and barley, but did not appear on oats until at least 1973.

The recognition of variation within these specialised forms followed the development of cereal varieties in the early days of the twentieth century. Previously cereals had been grown as ‘land races’, morphologically similar genetic mixtures from particular parts of the country, recognised by a name. At that time mildew does not seem to have been a problem, perhaps because of the genetic variation among the hosts.

Advanced farmers have always selected especially fine ears of wheat or barley from these land races to create new varieties, but especially so since the emergence of Mendelian genetics at the beginning of the twentieth century. The cereals are largely self-pollinating, so over a number of generations of ear selection they breed true and a variety becomes ‘fixed’. As the new varieties appeared so also did the science of agronomy and the mildew. Comparing these varieties in field plots, farmers saw mildew in a way that had not been possible before. The next step was to make crosses between varieties and to select new varieties from the progeny of these crosses. A whole spectrum of susceptibility and resistance to mildew was displayed by the new varieties. Nevertheless, in the early years of the twentieth century, although cereal mildew was recognised as a disease that could be troublesome, it was still thought of as a natural hazard that had to be endured. There was a mildew epidemic in Germany in 1903 but the pathologists had no remedy for it.

In barley (and a similar story can be told of wheat and oats) an attempt was made to incorporate mildew resistance in some of the new crosses after the first world war. In 1931 ‘Pflug’s Intensive’ was identified as a barley apparently completely resistant to mildew. It was a selection from a European land race and was used in crossing programmes to produce a number of the well-known barley varieties of that period. In succeeding decades, further sources of mildew resistance have been found, and since the Second World War the barley breeding programme has reflected the need to incorporate new sources of resistance in new varieties. These resistant varieties allow the identification of races of the mildew and in turn of genes in the host for resistance and susceptibility and in the fungus for virulence and avirulence (see Chapter 3). Resistance has been found in further selections from land races and also in exotic species like wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum). Crossing cultivated barleys with these exotic species is sometimes difficult, but an even greater problem is the array of ‘wild’ characteristics that are carried into the breeding line and have to be bred out by intensive selection. Different types of resistance are available, from near immunity to various levels of reduced susceptibility with small lesions and limited sporulation.

In barley most of the breeding has concentrated on genes for near immunity. The incorporation of these has generally led to a corresponding change in the fungus over a shorter or longer time, so that the resistance has broken down. We have here nothing more than a ‘plant pathologist’s merry-go-round’ similar to that described for the rusts (see here). Before moving on to discuss the utility of these plant breeding efforts we should note that some plant breeders believe that this approach is wrong, and the best way to breed ‘adapted’ varieties is by discarding the most susceptible plants in any breeding line and gradually building up a genotype with a tolerance of, rather than a high level of resistance to, the pathogen.

However, since breeding programmes from the 1930s to the present day have relied on the incorporation of genes for resistance or immunity, what strategies can be adopted to make best use of them? One is to turn out new varieties incorporating new genes for resistance as fast as possible and to combine with them, in a ‘belt and braces’ approach, the development of new fungicides and spraying techniques. This approach, of course, is favoured by commercial interests.

Another approach is to sow varieties with different resistance genes in a patchwork of fields over a wide geographical area, to slow down the rate of epidemic spread of different forms of the pathogen and possibly prevent the build-up of new races. A similar strategy is to separate the areas for growing winter and spring barley. For example, when a build-up of mildew on winter barley posed a threat to the spring barleys in Scotland the advisory service sought to discourage the growing of winter barley in areas where the valuable, mildew-susceptible spring barley ‘Golden Promise’ was grown. But this did not succeed. Farmers require flexibility and the freedom to grow what seems to them to make commercial sense. The high yields of winter barley and its value in spreading farm work between autumn and spring far outweighed the problem of mildew.

Another strategy is to hark back to the land races of the past, where mildew was apparently not a problem. It is known that they contained a population of barley genotypes with differing levels of mildew resistance and susceptibility. Could they be simulated by growing mixtures of barley cultivars containing a variety of genes for resistance to present day mildew races? Such mixtures have indeed been made and are effective, but they pose problems in farming. Straight mixtures of cultivars certainly reduce the severity of mildew attacks and more doubtfully may even show an advantage in terms of the exploitation of above-ground space and below-ground soil fertility, because they are morphologically different. The problems arise, however, because of the very tight specifications of the end user. In brewing, for example, when two or more cultivars are present in a crop it is impossible to get the uniform endosperm quality or the uniform germination required for making good malt. And since the brewer already accepts or rejects the crop in terms of a set of somewhat subjective commercial criteria the farmer cannot afford to add any more disadvantages to the crop for sale.

It is true that it is possible to construct a ‘multiline variety’ which is reasonably uniform for morphological and commercial features, but which contains a population of different resistance factors for mildew. The problems in the use of such ‘varieties’ lie in the commercial strategies of the breeding companies and the legislative framework within which varieties are defined and released. When it is realised that improvements are continually being made in yield and commercial qualities, and that disease resistance has to be incorporated for other pathogens too, it is clear that the success of a cultivar depends on elements of chance, fashion and other indefinable factors. Nevertheless, barley mixtures designed to overcome the problems of disease can now be found in the catalogues of some seed merchants. It is good to know that the science behind resistance breeding is partly understood and that methods exist for the rational production of varieties that resist disease.

It is one thing to find evidence of pathogenic variation in fungi causing disease of cultivated plants, where the actions of plant breeders slowly reveal the range of pathogenic variation present. It is quite another matter to investigate this phenomenon in wild plants. However, in Israel, which is thought to be a centre of origin of cultivated barleys, not only are cultivated barleys infected by mildew but their wild relatives are also infected by genetically similar forms of the fungus. This has made possible a detailed investigation of the range of pathogenicity present in the wild populations. It is at least equal to that identified in cultivated barley. Some of the races in geographical or ecological isolation are more virulent on cultivated barleys than any previously known race. Conversely, there are genes in the wild Hordeum population for all degrees of resistance, including some for resistance to all the mildew races so far recognised on cultivated barleys.

Although this is an indication of the presence of two interacting genetic systems in wild host and pathogen combinations, there is a lingering worry that the presence of the population of mildews on cultivated barleys might be influencing the situation. This problem has been taken care of in studies of the interaction between the common groundsel (Senecio vulgaris) and its mildew Erysiphe fischeri, for no cultivated form of S. vulgaris exists. First a number of inbred lines of the Senecio were selected and tested for susceptibility to a number of genetically homogeneous isolates of the mildew. The lines were easily obtained by isolating single chains of conidia, picked up on a dry needle, as the primary inoculum (every spore in a chain is derived from the same mother cell, so all are identical). Once the inbred lines of the host and the pure lines of the pathogen were established, replicated trials of the reactions of the host to the pathogen were carried out, using detached leaf segments placed (in Petri dishes) on water agar containing the senescence-retarding chemical benzimidazole. In this simple set up the leaf segments were kept fresh and there was no inhibition of the growth of the mildew.

It was shown that a wide range of resistance and susceptibility to mildew existed in the host population, with an equally wide range of pathogenic and nonpathogenic forms among isolates from the wild population of the pathogen. For example, a sample of only 24 mildew isolates yielded 19 different races on the differential hosts employed. Isolates from Glasgow and from Wellesbourne in Warwickshire, England, showed a similar and partially overlapping heterogeneity. From this and other evidence provided by studying the behaviour of pathogens on wild plants it is possible to postulate that co-evolution of host and pathogens continues throughout the evolutionary life of plants.

MILDEWS AND FUNGICIDES

Powdery mildews have played a significant role in the development of modern fungicides. It was shown in about 1850 that sulphur could be used to control vine mildew, then a serious threat to European wine production. It was used in various forms as a sulphur dust, as sulphur painted onto glasshouse heating pipes, and in mixtures with water, soap and so on to control a variety of powdery mildews. ‘Eau Grison’, or ‘Bouille Versaillaise’, was compounded from sulphur and lime boiled together and in time became the lime-sulphur widely used in orchards in Europe and the USA. It comprised a concentrated mixture of calcium polysulphides which broke down on dilution with water and exposure to the air to give a suspension of fine particles of sulphur along with other sulphur compounds. However, lime-sulphur had many disadvantages: the spraying regimes required the expensive transport of great quantities of water; it could under certain circumstances be toxic to fruit varieties; and in all circumstances it was toxic to certain ‘sulphur-shy’ varieties such as the apple ‘Stirling Castle’ and the gooseberry ‘Leveller’. Even so, lime-suphur was increasingly a standard part of orchard management in the first half of the twentieth century. At the same time organic fungicides were being sought which would be easier to use and which might be used in lower volume sprays.

Meanwhile the breeding programme that was producing cereal varieties resistant to mildew also brought into commerce a number of high-yielding varieties which became spectacularly infected with mildew when the genetic resistance in the host was overcome by a change in the pathogen. Farmers sought to ameliorate this situation by the application of sprays, and although this was a difficult operation in fields of standing barley or wheat, new spraying equipment with long booms mounted high on the tractor and the development of sowing techniques that left ‘tramlines’ (unsown drills for tractor access) allowed the spraying of cereal crops without damage. This opened a new market to the manufacturers of sprays and even greater efforts were put into finding and developing new compounds. By 1960 non-phytotoxic derivatives of the hitherto phytotoxic dinitrophenols were being produced and these were very effective in controlling mildew. There followed a series of syntheses which produced other useful fungicides. To iterate them here would be tedious, but three groups are particularly noteworthy. The first, the 2-aminopy-ridines, were synthesised in the mid-1960s. These were systemic fungicides which could enter the xylem of the plant and diffuse upwards. Some of them proved to be particularly useful as soil drenches for the control of mildew in glasshouses on, for example, cucumber, one application keeping the plants disease-free until harvesting. Others could be used in similar fashion as a seed-dressing on cereals, as well as being valuable sprays; a seed application kept the young plant free of mildew for a while, but the protection was not sufficient to last for the whole life of the plant and was usually supplemented with subsequent sprays. The timing of the application of such sprays is critical, and constant monitoring is important for the correct spraying sequence. An interesting feature of these fungicides is their capacity to disrupt the behaviour of the mildew on the leaf. Instead of growing over the leaf surface it begins to grow up and away from it.

The other two synthetic systemic fungicides can be considered together. These are the benzimidazole and morpholin fungicides, which inhibit sterol synthesis, but at a different site in each case. The benzimidazoles are active against a range of organisms, including mildew, while the morpholines are particularly effective against mildew species.

Benomyl, which is one of the benzimidazole fungicides, came into use in the late 1960s and shortly afterwards adapted forms of the mildews were found which it could not control. This phenomenon of genetic adaptation to resist fungicides has a superficial similarity to the changes that take place when pathogenic variants of a fungus attack hitherto resistant host varieties. There is now ample evidence that pathogens develop resistance to a range of new organic fungicides soon after their release. Whether the nuclei controlling such resistance pre-exist in the population, or whether resistance develops as a consequence of new mutations, is not yet clear. The practical consequence is that it is necessary to develop new fungicides, to ring the changes with existing ones or to apply mixtures.

The way ahead lies in a fuller understanding of the nature of pathogenicity and resistance, so that spraying and the manipulation of resistance go hand in hand. The selection of resistant types with genes for slow colonisation by the fungus and for mature plant resistance, which seem less liable to be overtaken by a change in the fungus, may produce more stable varieties. The ideal would be a situation in which the utilisation of different types of resistant cultivars, alone or in mixtures, eliminated the need for commercial fungicides altogether. We recognise, however, that there are a great many vested commercial and political interests that might militate against the early development of such a situation.

The powdery mildews are a particularly interesting group for the naturalist to study. Easy to see and to collect, in the teleomorphic phase they are readily identifiable to the level of the genus. At the species level there is still much observational work to be done by the field naturalist, and as we have illustrated here there are many unsolved pathological problems which would respond to careful study with limited equipment.