Inge Russell

CONTENTS

8.2.6 Other Cytoplasmic Structures

8.3.8 Mass Mating and Genome Shuffling

8.4.3 Uptake and Metabolism of Wort Carbohydrates

8.4.4 Maltose and Maltotriose Uptake

8.4.5 Uptake and Metabolism of Wort Nitrogen

8.4.6 Uptake of Wort Minerals and Vitamins by Yeast

8.5.6 Diacetyl and 2,3-Pentanedione

8.7 Yeast Management in the Brewery

8.7.1 Glycogen and Trehalose—The Yeast’s Carbohydrate Storage Polymers

8.7.2.2 Multiple Cultures in a Plant Environment

8.7.2.3 Brettanomyces and Specialty Yeasts

8.9.1 Contamination of Cultures

8.9.2 Yeast Cropping from a Vertical Fermenter

8.11 Cell Viability/Vitality and Yeast Pitching

8.11.1 Microscopic Examination

8.11.2 Viability of Yeast and the Methylene Blue Test

8.11.5 Metabolic Activity Tests

8.11.7 Pitching Rate Calculations

8.1 TAXONOMY OF YEAST

Interest in brewing yeast centers around its different strains, and there are thousands of unique strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These strains encompass brewing, baking, wine, distilling, and laboratory cultures. There is a problem classifying such strains in the brewing context; the minor differences among strains that the taxonomist dismisses can be of great technical importance to the brewer. Saccharomyces, Latin for sugar fungus, is the name first used for yeast in 1838 by Meyen, but it was the work of Hansen at the Carlsberg Laboratory in Denmark during the 1880s that gave us the species names of S. cerevisiae for head-forming yeast used in ale fermentations and S. carlsbergensis for nonhead-forming yeast associated with the lower temperature range of lager fermentations. Historically, lager yeast and ale yeast have been taxonomically distinguished on the basis of their ability to ferment the disaccharide melibiose. Strains of lager yeast possess the MEL genes, produce the extracellular enzyme α-galactosidase (melibiase), and are able to utilize melibiose, whereas ale strains that do not produce α-galactosidase are therefore unable to utilize melibiose. Traditionally, lager is produced by bottom-fermenting yeasts at fermentation temperatures between approximately 5°C and 15°C (maximum growth temperature is approximately 34°C) and, at the end of fermentation, these yeasts flocculate and collect at the bottom of the fermenter. Top-fermenting yeasts, used for the production of ale at fermentation temperatures between approximately 15°C and 26°C (maximum growth temperature is 37°C or higher), tend to be somewhat less flocculent, and loose clumps of cells adsorbed to carbon dioxide bubbles are carried to the surface of the fermenting wort. Consequently, top yeasts were traditionally collected by skimming from the surface of the fermenting wort, whereas bottom yeasts were collected, or cropped, from the fermenter bottom. The differentiation of lagers and ales on the basis of bottom and top cropping has become less distinct with the advent of vertical bottom fermenters and centrifuges. There is much greater diversity among ale strains than lager strains.

The taxonomy surrounding the yeast Saccharomyces has been confusing and ever-changing. Saccharomyces sensu stricto is a species complex that includes most of the yeast strains relevant in the fermentation industry as well as in basic science (i.e., S. bayanus, S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, and S. pastorianus). Names of species and single isolates have, and are still undergoing, name changes that cause confusion for yeast scientists and fermentation technologists.

There are three main reasons that taxonomists change yeast names. These are: (1) the yeast was incorrectly described or named; (2) new observations warrant such change; or (3) a prior published legitimate name is uncovered.1 Unfortunately, in the past, changes in nomenclature varied with changes in the criteria taxonomists believed should be used. These varied from phenotypic characteristics (such as microscopic appearance and ability to use certain substrates), nutritional characteristics (which could mutate), or the criteria of interfertility within strains of the same species. Newer techniques of molecular taxonomy and DNA relatedness are now being used for yeast classification. Recent findings have demonstrated that S. bayanus and S. pastorianus are not homogeneous and do not seem to be natural groups. As molecular biology methods become simpler and are marketed in inexpensive user-friendly kits and the cost of genome sequencing continues to drop in price, these newer identification methods are quickly becoming the methods of choice.2, 3

In 1970, taxonomists repositioned the lager yeast S. carlsbergensis as S. uvarum. In 1990, taxonomists repositioned S. uvarum as part of S. cerevisiae. Then, S. cerevisiae var. carlsbergensis was classified as S. pastorianus. The species was often written as S. pastorianus/carlsbergensis for clarity. There was an argument4 for keeping the name S. carlsbergensis for lager-brewing yeast rather than using the name S. pastorianus; however, today S. pastorianus is considered to be the correct taxonomic name of the species.

The lager yeast S. pastorianus (syn. Saccharomyces carlsbergensis) is a natural allopolyploid hybrid of Saccharomyces eubayanus and S. cerevisiae. This hybrid yeast was created by the fusion of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae ale yeast with a cryotolerant Saccharomyces species, Saccharomyces eubayanus sp. nov., which resembles Saccharomyces bayanus (a complex hybrid of S. eubayanus, Saccharomyces uvarum, and S. cerevisiae, found only in the brewing environment).5

S. eubayanus is a species that until recently had eluded identification, and there is debate as to its geographical origin (Patagonia, Tibetan Plateau, China, or some other yet unidentified region) and it is the part of the hybrid that endows the yeast with its capacity to ferment at relatively cool temperatures, while the S. cerevisiae part of the hybrid contributes the ability to ferment maltotriose.6 The complete genome sequence of S. eubayanus has now been published,7 and it is 99.5% identical to the non- S. cerevisiae portion of the S. pastorianus genome sequence and suggests specific changes in sugar and sulfite metabolism occurred during domestication in the lager-brewing environment.

Gallone et al.8 recently examined the history and domestication of ale-brewing yeast using genomic and phenotypic analyses by sequencing 157 S. cerevisiae yeasts. They concluded that there are five sub-lineages that separate the brewing yeast from wild strains and that these originated from only a few ancestors. They found industry-specific selection for stress tolerance, sugar utilization such as maltotriose, and flavor production. Krogerus et al.9 in a recent review explore this topic of natural hybrids and the creation of new hybrids and further attempt to explain the complex history of brewing yeast and discuss future potential opportunities.

For simplicity, brewing yeast will be referred to as S. cerevisiae throughout this chapter unless distinct reference is made to lager yeast.

8.2 STRUCTURE OF YEAST

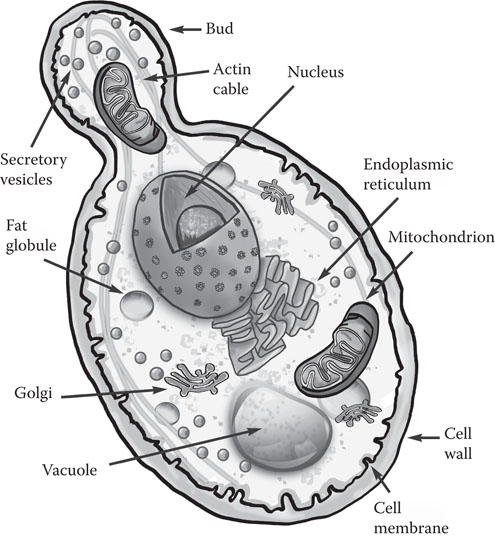

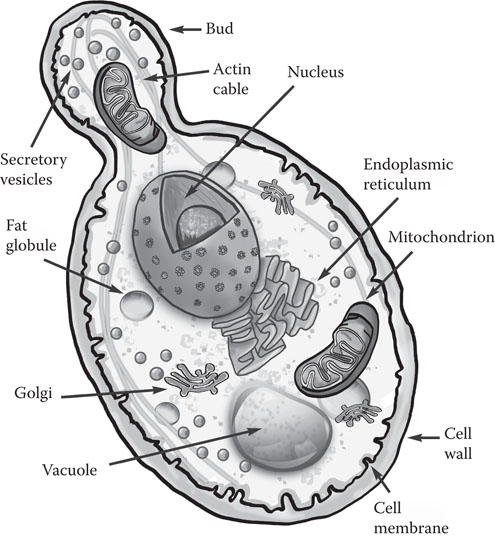

The group of microorganisms known as “yeast” is by traditional agreement limited to fungi in which the unicellular form is predominant.10 Figure 8.1 shows the features of a typical yeast cell, and Figure 8.2 is an electron micrograph of a budding yeast cell.

Figure 8.1 Main features of a typical yeast cell.

Figure 8.2 Electron micrograph of budding yeast cell. (Courtesy of Alex Speers, Heriot-Watt University.)

Yeasts vary in size, from roughly 5 μm to 10 μm in length to a breadth of 5 μm to 7 μm. The mean cell size varies with the growth cycle stage, fermentation conditions, and cell age (older cells are larger in size).

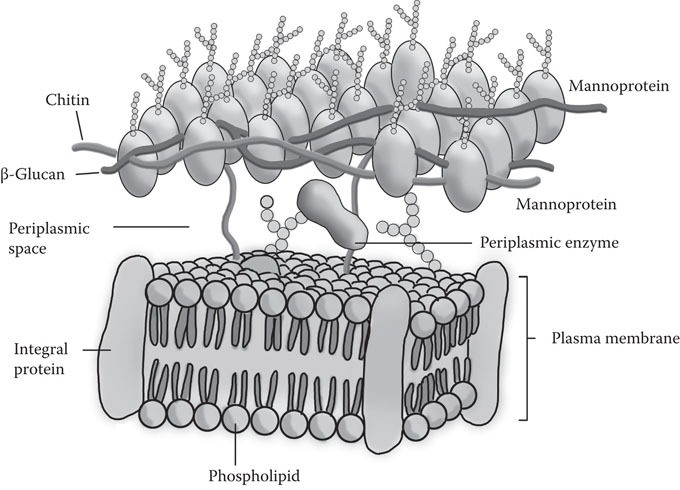

8.2.1 Cell Wall

The yeast cell wall is a multifunctional organelle of protection, shape, cell interaction, reception, attachment, and specialized enzymic activity. The cell wall, which is 100 nm to 200 nm thick, constitutes 15% to 25% of the dry weight of the cell and consists primarily of equal amounts of phosphomannan (31%) and glucans (29%). There are three glucans present in the wall (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Simplified structure of the yeast cell wall and plasma membrane.

The major component of the wall is an alkali-insoluble, acid-insoluble β-1,3-linked polymer, which helps the wall maintain its rigidity. There is an alkali-soluble branched glucan, with predominantly β-1,3-linkages, but with some β-1,6-linkages as well. The cell wall also contains a small portion of predominantly β-1,6-linked glucan. Chitin, a polymer of N-acetyl glucosamine, is present in small quantities (2% to 4%) and is almost always restricted to the bud scar. Mannans are present as an α-1,6-linked inner core with α-1,2- and α-1,3-side chains. Lipids are present at about 8.5% and proteins at about 13%. The carbohydrate portion of the mannoprotein on the yeast cell surface determines the immunochemical properties of the cell. The exact composition of the cell wall is dependent on growth conditions, age of the culture, and the specific yeast strain. The construction and structures of the yeast cell wall have been reviewed in detail by Klis et al.11

8.2.2 Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane acts as a barrier to separate the aqueous interior of the cell from its aqueous exterior. It consists of lipids and proteins, in more or less equal amounts, together with a small amount of carbohydrate. It is 8 nm to 10 nm thick, with occasional invaginations protruding into the cytoplasm (Figure 8.3).

The carbohydrate portions of the membrane-bound glycoproteins are believed to extend only from the external surface of the membrane. The plasma membrane has a role in regulating the uptake of nutrients and in the excretion of metabolites. It is also the site of cell wall synthesis and assembly, and secretion of extracellular enzymes.

The intrinsic membrane proteins are inserted in a lipid bilayer consisting primarily of phospholipids and sterols. The principal phospholipids are phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine, and their primary function is believed to be the maintenance of a barrier between the external and internal cell environment. The fluidity of the plasma membrane is regulated by phospholipid unsaturation and is an important factor in ethanol tolerance. The sterols in the plasma membrane are ergosterol, 24(28)-dehydro-ergosterol, zymosterol, and smaller quantities of fecosterol and lanosterol. They confer integrity and rigidity on the membrane.

The main function of the plasma membrane is to dictate what enters and what leaves the cytoplasm. The extrinsic proteins, those that interact with membrane lipids and proteins by polar binding, cover part of the bilayer surface, and a large group of these proteins is involved in solute transport.12 Brewer’s yeast requires initial oxygenation, prior to fermentation, to ensure correct plasma membrane synthesis as oxygen is absolutely required for the synthesis of the unsaturated fatty acids and sterols.

8.2.3 The Periplasmic Space

This is the thin area between the outer surface of the plasma membrane and the inner surface of the cell wall. Secreted proteins, which are unable to permeate the cell wall, are located here. This includes enzymes such as invertase, acid phosphatase, and melibiase. For example, sucrose is broken down in the periplasmic space by the enzyme invertase to fructose and glucose.

8.2.4 Nucleus

The cell nucleus is roughly spherical, about 2 μm in diameter, and is visible with phase contrast microscopy. In resting cells, it is usually situated next to a prominent vacuole. The nucleus consists primarily of DNA and protein and is surrounded by the nuclear membrane. Saccharomyces contains 16 linear chromosomes. The nuclear membrane, which is perforated at intervals with pores, remains intact throughout the cell cycle.

8.2.5 Mitochondria

Electron micrographs of yeast cells reveal round or elongated mitochondrial structures composed of two distinct membranes, the outer and the inner, within the cytoplasm. The cristae within the mitochondria are formed by the folding of the inner membrane. Specific enzymes are associated within four distinct locations: the outer membrane, the intermembrane space, the inner membrane, and the matrix. Most of the enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle are present in the matrix of the mitochondrion. The enzymes involved in electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation are associated with the inner membrane. When yeast is grown aerobically on a nonfermentable carbon source, the mitochondria of the fully respiring cells are rich in the cristae structures. Under aerobic conditions, yeast mitochondria are primarily involved in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis during respiration. In glucose-repressed cells, only a few mitochondria with poorly developed cristae can be seen. Mitochondrial DNA only comprises approximately 0.1 % of total cellular DNA. Stewart13 recently reviewed the influence of mitochondria on brewer’s yeast fermentations. Jensen et al.14 and Mishra and Chan15 provide in-depth reviews on overall yeast mitochondrial dynamics.

8.2.6 Other Cytoplasmic Structures

8.2.6.1 Vacuoles

Vacuoles are a part of an intra-membranous system that includes the endoplasmic reticulum and are easily seen under the light microscope. They serve as dynamic stores of nutrients, and they provide a site for the breakdown of macromolecules. They are also key in intracellular protein trafficking in yeasts. The form and size of the vacuoles change during the cell cycle, and they can occupy up to one-third of the volume of a cell. Mature cells contain large vacuoles, which fragment into small vesicles when bud formation is initiated. Later in the cell cycle, the small vacuoles fuse again to produce a single vacuole in the mother and daughter cells. The vacuoles contain proteases and hydrolases, and they also store metabolites such as amino acids. Vacuoles are bounded by a single membrane called the tonoplast. The secretory pathway in yeast is believed to work in the following fashion: endoplasmic reticulum → Golgi complex → vesicle → cell surface or vacuolar compartment. This sequence allows the transport of soluble and membrane-bound proteins, both for extracellular secretion and for assembly of the vacuole.16 Further details in chapter 14.

8.2.6.2 Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes are simple organelles up to 1 nm in size. They are sealed vesicles surrounded by a single membrane. Yeast peroxisomes perform a variety of functions and are also the sites of fatty acid degradation. The number and volume of the peroxisomes change depending on the external conditions. Dedicated membrane proteins are required to allow communication across the peroxisomal membrane.17

8.2.6.3 Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a large organelle formed as a network of tubules and sacs that extends from the nucleus. The whole ER is surrounded by a continuous membrane. The ER is divided into two parts: the rough ER on which the ribosomes are attached and the smooth ER. Secreted proteins are synthesized by the membrane-bound ribosomes and transported into the ER, where they are processed and then either retained or transported further to the Golgi apparatus. English and Voeltz18 review ER structure and its interconnections with other organelles.

8.2.6.4 Golgi Complex

The Golgi complex is an organelle built of several flattened, membrane-enclosed sacs and is part of the cellular endomembrane system. Secretory proteins exit from the ER in coated vesicles and then progress through the Golgi complex for processing before delivery to their final destination.19

8.2.6.5 Cytosol

The cytosol (cytoplasmic matrix) is the liquid matrix around the organelles in the cell and is separated into compartments by membranes. It is the prime site for protein synthesis and degradation. The cytosol is contained within the plasma membrane and surrounds the nucleus. It makes up more than half of the cell volume and consists of, among other things, all the free ribosomes and proteasomes. Proteasomes are responsible for the digestion of proteins that may be detrimental to the cell. The cytosol together with the rest of the cell content, except the nucleus, constitute the cytoplasm.

8.2.6.6 Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton gives the cell its mobility and support. It serves to organize the cytoplasm, to provide the means for generating force within the cell, and to determine and maintain the shape of the cell and its structural integrity. The shape and movement of the cell is controlled by three main components. The microfilaments and the microtubules give the cell support and movement, while the intermediate filaments are built of several different proteins and play a supportive role. Actin filaments in the cytoskeleton are constantly being built and then broken down due to the dynamic nature of the cytoskeleton.

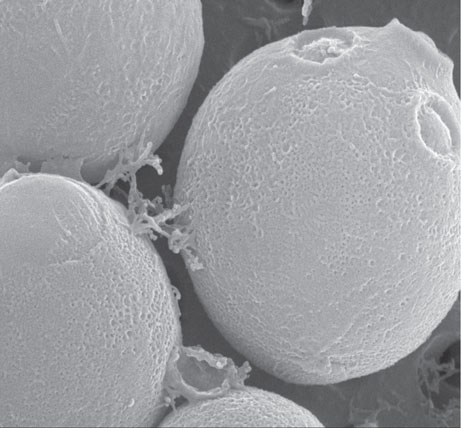

8.3 LIFE CYCLE AND GENETICS

8.3.1 Vegetative Reproduction

Most brewing strains are diploid, polyploid, or aneuploid, whereas most laboratory strains are haploid. The yeast cell cycle refers to the repeated pattern of events that occur between the formation of a cell by division of its mother cell and the time when the cell itself divides. Individual yeast cells are mortal. Yeast aging is a function of the number of divisions undertaken by the individual cell, and it is not a function of the cell’s chronological age. All yeast cells have a set lifespan determined both by genetics and environment. The maximum division capacity of a cell is called the “Hayflick limit.” Once a cell reaches this limit, it cannot replicate further and enters a stage of senescence and then death. A yeast cell can divide to produce 10 to 33 daughter cells. Research with industrial ale strains showed a high of 21.7 + 7.5 divisions to a low of 10.3 + 4.7 divisions.20 When yeast is examined under the microscope, the following are signs of aging: an increase in the number of bud scars, an increase in the cell size, surface wrinkles, granularity in the cytoplasm, and the retention of daughter cells. Older yeasts cell have a reduced capacity to adapt to stress and to ferment due to the progressive impairment of cellular mechanisms due to aging.

As the mother cell ages, there is protein damage within the cell. Before the yeast cell bud breaks off, the damaged and aged proteins in the newly formed yeast cell bud are transported back into the mother cell. Thus, the mother cell retains the problems and sends the daughter cell (bud) on its way in a healthy condition. This guarantees that the new daughter cell will be healthier than the parent cell.21

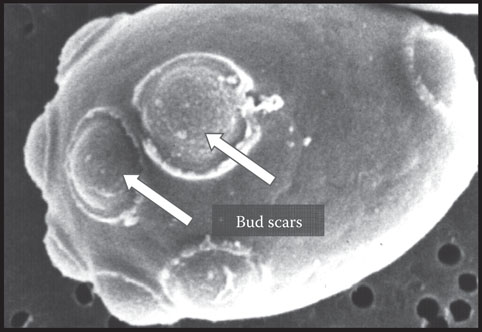

As the cell reproduces by budding, a birth scar is formed on the new daughter cell and a bud scar results on the mother cell. As budding continues, an individual cell ages and bud scars accumulate (usually 10 to 30) (Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 Electron micrograph of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast cell showing numerous bud scars on the cell surface.

By counting the number of bud scars on a cell, it is possible to estimate a particular cell’s age. The important point to remember is that although individual cells age and die, the total ensemble of cells does not age, and, in theory, a well-cared-for yeast culture could be used indefinitely. A haploid yeast cell, in a rich medium such as wort and at its optimum temperature, has a doubling time of approximately 90 min.

The cell cycle can be divided into a number of different phases, with the two major phases being the S phase (synthesis phase where DNA is duplicated) and the M phase (mitosis phase where cell division occurs). Mitosis and nuclear division occupy a relatively short time in the cell cycle. The remainder is divided into a G1 period, (telophase to the beginning of DNA synthesis), an S period (time of DNA synthesis), and a G2 period (end of DNA synthesis to prophase). (Figure 8.5)

Figure 8.5 Phases of the yeast cell cycle.

The G1, S, and G2 phases together constitute the interphase, and this occupies more than 95% of the cell’s time. The G1 phase is where the cells synthesize the enzymes needed for genome duplication, and the G2 phase is where the duplicated centrosomes separate to organize the mitotic spindle. Salazar-Roa and Malumbres22 have recently reviewed the complex process of the cell cycle and the significant advances in our understanding of its regulation.

8.3.2 The Genome

Brewing yeasts are polyploid and, in particular, triploid, tetraploid, or aneuploid. Polyploidy brings benefits to the strain in that extra copies of genes for sugar utilization can improve fermentation performance. Polyploid yeasts are also more genetically stable as it takes multiple mutational events to change them.23, 24 As previously mentioned, the lager yeast S. carlsbergensis has been reclassified as S. pastorianus. Gibson and Liti25 have reviewed the evolutionary history of this lager yeast and the ancestral hybridization events between S. cerevisiae and S. eubayanus that led to this yeast’s strong fermentative ability and traits such as cold tolerance.

The chromosomes are located in the cell nucleus, and the total haploid yeast genome consists of more than 12 million base pairs. A widely studied laboratory haploid yeast,26 strain S228C, was chosen for the yeast genome project, and its DNA sequence has now been fully characterized. The Saccharomyces genome database (SGD) provides a wealth of information at http://www.yeastgenome.org.

8.3.3 Strain Improvement

There are many strategies to obtain superior industrial yeast,27 and some of these have recently been reviewed by Pretorius et al.28 and Steensels et al.29 They include natural and artificial diversity, mutagenesis, sexual hybridization, spheroplast fusion, cytoduction, and evolutionary engineering. In terms of natural genetic diversity, there is a huge unexplored pool of organisms that have not yet been examined in detail or even categorized as to genera and species.

In contrast to exploring natural genetic diversity, there is a whole new field of science emerging called “synthetic genome engineering.” Pretorius30 has recently reviewed this topic in terms of wine yeast and discusses the seismic shifts in this field. The convergence of the many different areas: bimolecular, chemical, physical, mathematical and computational sciences, engineering, and the rapid advances in high-throughput DNA sequencing and synthesis techniques. The use of CRISPR/Cas9 for genetic modifications in Saccharomyces has been referred to as “using a molecular Swiss army knife.”31

The work in synthetic genomes will continue to increase our understanding of yeast biochemical pathways and the global “Synthetic Yeast Genome (Sc2.0) Project” has the goal to synthesize all 16 chromosomes of S. cerevisiae by 2018. The first S. cerevisiae cell with a fully functional synthetic chromosome was accomplished by Annaluru et al.32 in 2014. Work at this intersection of biology and engineering is only beginning, and yeast is the ideal research organism for this task.33, 34 There is little doubt that, as this research progresses, new discoveries and opportunities for brewing yeast will also be seen with the implementation of so many new technologies. Will consumers react to the concept of a yeast for beer production containing synthetic DNA in a similar negative manner as they have expressed for recombinant yeast produced with the insertion of DNA from other yeast species or bacteria to enhance brewing qualities is a question with no answer as of yet.

8.3.4 Mutation and Selection

Classical approaches to strain improvement include mutation and selection, screening and selection, and crossbreeding. Mutation is any change that alters the sequence of bases along the DNA molecule, thus modifying the genetic material. The average spontaneous mutation frequency in S. cerevisiae at any particular locus is approximately 10−6 per generation.

Chemical mutagens and physical treatments such as ultraviolet light are used to induce mutation frequencies to detectable levels. Problems are often encountered with the use of mutagens for brewing strains as mutagenesis is a destructive process and can cause gross rearrangement of the genome. The mutagenized strains often no longer exhibit many of the desirable properties of the parent strain, and, in addition, may exhibit a slow growth rate and produce a number of undesirable taste and aroma compounds during fermentation. Moreover, mutagenesis is seldom employed with industrial strains; their polyploid nature obscures mutations because of the nonmutated genes. Casey34 cautioned on the use of mutagens as these hidden undesirable mutations can become expressed after a time lag by such events as chromosome loss, mitotic recombination, or mutation of other wild type alleles. He suggested an analogy to computer viruses in computer software that can surface months later. In a similar way, hidden mutations can later spoil the efforts of a protracted strain improvement program.

Screening of cultures to obtain spontaneous mutants or variants has proved to be a more successful technique as this avoids the use of destructive mutagens. Some early examples follow. To select for brewery yeast with improved maltose utilization rates, 2-deoxyglucose, a glucose analog, was employed and spontaneous mutants selected that were resistant to 2-deoxyglucose. These isolates were also found to be derepressed for glucose repression of maltose uptake, thus allowing the cells to take up maltose without first requiring a 50% to 60% drop in wort glucose levels. This resulted in faster fermentation rates and no alternation in the final flavor of the product.35, 36 Later research by Piña et al.37 reported similar results but this time using a lager yeast strain and high gravity (25°Plato) wort. However, the increased wort fermentation rate was not sufficient to introduce the 2-DOG mutants into commercial brewing. (Further details in Chapter 14 and in Figure 14.4.)

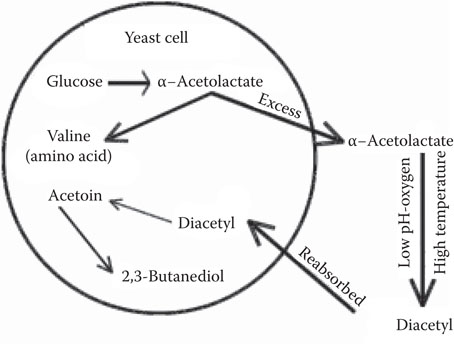

Galva’n et al.38 reported the isolation of brewing yeast strains with a dominant mutation and resistance to the herbicide sulfometuron methyl (SM). Yeast mutants resistant to SM are dominant and showed a decreased level of acetohydroxy acid synthase. This enzyme is the first enzyme in the isoleucine–valine biosynthetic pathway and produces acetolactate, the precursor of diacetyl in brewing fermentations. Workers at the Carlsberg Research Institute isolated low diacetyl-producing strains and conducted successful plant trials at the 4500 hL scale.39

There are three characteristics routinely encountered resulting from yeast mutation that can be harmful to a brewing fermentation. These are: the tendency of yeast strains to mutate from flocculence to nonflocculence; the loss of ability to ferment maltotriose; and the presence of respiratory deficient mutants. This last group usually consists of cytoplasmic mutants.

The most frequently identified spontaneous mutant found in brewing yeast strains is the respiratory deficient (RD) or “petite” mutation. The RD mutant arises spontaneously through a rearrangement of the mitochondrial genome. It normally occurs at frequencies of between 0.5% and 5% of the yeast population but, in some strains, figures as high as 50% have been reported. The mutant is characterized by deficiencies in mitochondrial function, resulting in a diminished ability to function aerobically and, as a result, these yeasts are unable to metabolize nonfermentable carbon sources, such as lactate, glycerol, or ethanol. Respiratory deficient mutants can range from point mutations (mit−) to deletion mutations (rho−) to the complete elimination of mitochondrial DNA (rho0). Many phenotypic effects occur due to this mutation, and these include alterations in sugar uptake, metabolic by-product formation, and tolerance to stress factors, such as ethanol and temperature. Flocculation, cell wall and plasma membrane structure, and cellular morphology are affected by this mutation.13

It should be remembered that beer produced with a yeast RD strain or with a strain that produces a high number of RD mutants is more likely to have flavor defects and fermentation problems. Ernandes et al.40 have reported that beer produced from these mutants contained elevated levels of diacetyl and some higher alcohols. Wort fermentation rates were slower, higher dead cell counts were observed, and biomass production and flocculation ability were reduced.

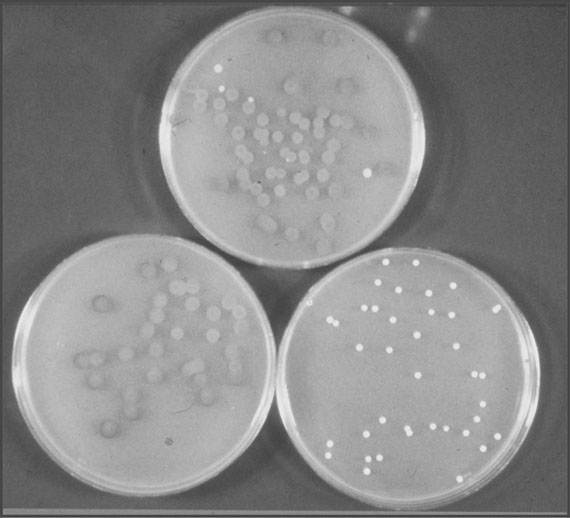

To test for the presence of respiratory deficient mutants, five-day-old colonies of yeast grown on peptone-yeast (PY) extract medium are overlaid with triphenyltetrazolium agar.41 Respiratory sufficient colonies stain red and RD mutants remain white. Respiratory deficient colonies growing on an agar plate are often smaller in size and hence the name “petites” (Figure 8.6). Because RD mutants lack respiratory chain enzymes, but can still grow by employing glycolysis as a source of ATP, a confirmative test involves streaking a suspect colony onto a PY glucose plate and a PY plate containing a nonfermentable carbon source, such as lactate or glycerol. An RD colony typically grows on the glucose plate but not on the lactate plate.42

Figure 8.6 Triphenyltetrazolium overlay plates illustrating the presence of respiratory deficient (RD) mutants and respiratory sufficient (RS) colonies. Top plate—mix of RS and RD colonies. Bottom left plate—only RS colonies. Bottom right plate—only RD colonies.

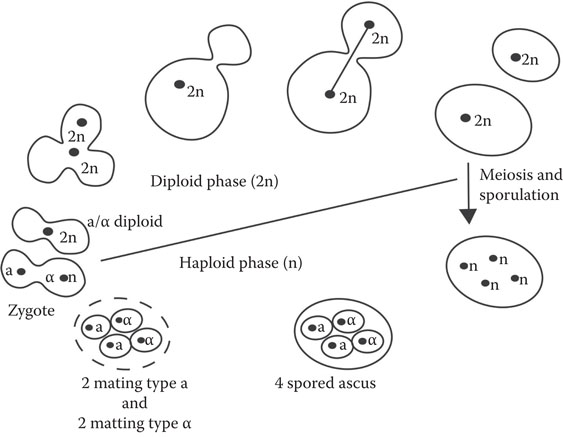

8.3.5 Hybridization

The study of yeast genetics was pioneered by Winge43 in 1935 and his coworkers at the Carlsberg laboratory in Denmark; they established the haploid–diploid life cycle (Figure 8.7). Saccharomyces can alternate between the haploid (a single set of chromosomes) and diploid (two sets of chromosomes) states. Yeast can display two mating types, designated a and α, which are manifested by the extracellular production of an a- or an α-mating pheromone. When a haploids are mixed with α haploids, mating takes place and diploid zygotes are formed. Under conditions of nutritional deprivation, diploids undergo reduction division by meiosis and differentiate into asci, containing four uninucleate haploid ascospores, two of which are a mating type and two of which are α mating type. Ascus walls can be removed by the use of preparations such as zymolyase. The four spores from each ascus can be isolated by use of a micromanipulator, then induced to germinate, tested for their fermentation ability, and subsequently employed for further hybridization work. Both haploid and diploid organisms can exist stably and undergo cell division via mitosis and budding.

Figure 8.7 Haploid/diploid life cycle of Saccharomyces spp.

Although the technique of hybridization fell into disfavor for a number of years, when recombinant DNA was thought to be the solution to all future gene manipulation requirements, it has gradually come to be accepted again as one of the valuable techniques in the toolbox for strain improvement.44 There are three prerequisites for the production of a hybrid yeast by this technique. First, it must be possible to induce sporulation in the parent strains; second, single spore isolates must be viable; and, third, hybridization (mating) must take place when the spores of single-spore cultures are placed in contact with one another. The great stability of industrial strains has been attributed to the following characteristics: little or no mating ability, poor sporulation, and low spore viability. Nevertheless, it is possible to increase sporulation ability in many of these industrial strains, thus making them much more amenable to hybridization.45

Employing the classical techniques of spore dissection and cell mating, diploid strains were produced with multiple genes for carbohydrate utilization: for example, a diploid that is homozygous for all three known starch-hydrolyzing genes DEX1/DEX1, DEX2/DEX2, STA3/STA3. This starch hydrolyzing enzyme (glucoamylase) was heat stable and had no debranching ability. These strains could then be employed for specific purposes or further improved by fusing them to industrial polyploids with additional desirable characteristics.46

Gjermansen and Sigsgaard47 carried out extensive crossbreeding studies with a S. pastorianus strain and produced hybrids that were tested at the 575 hL scale and that produced beer of acceptable quality. Similarly, crosses between ale and lager meiotic segregants produced hybrids with faster attenuation rates and produced beers of good palate, which lacked the sulfury character of the lager but retained the estery aroma of the ale.48 The aforementioned examples demonstrate that although hybridization is an old and “classical” technique, it is still very useful. Delneri et al.49 reported on reconfiguring the S. cerevisiae genome so that it was collinear with that of S. mikatae. Researchers demonstrated that this imposed genomic collinearity allowed the generation of interspecific hybrids, which produced a large proportion of spores that were viable but extensively aneuploid. They obtained similar results in crosses between wild-type S. cerevisiae and the naturally collinear species S. paradoxus. One of the major advantages to crossbreeding is that this technique carries none of the burden of ethical questions and fears that can sometimes accompany the use of recombinant DNA technology.

8.3.6 Rare Mating

Rare mating, also called forced mating, is a technique that disregards ploidy and mating type and, thus, is ideal for the manipulation of polyploid/aneuploid strains where normal hybridization procedures cannot be utilized. When nonmating strains are mixed at a high cell density, a few hybrids that have fused nuclei form, and these can usually be isolated using appropriate selection markers. A possible disadvantage to this method is that while incorporating the nuclear genes from the brewing strain, the rare mating product can also inherit undesirable properties from the other partner, which is often a nonbrewing strain. An example of this was the construction of dextrin-fermenting brewing strains, where the POF gene (phenolic-off-flavor), which imparted the ability to decarboxylate wort ferulic acid to 4-vinyl guaiacol was also introduced50 and gave the resulting beer a phenolic clove-like off-flavor. This made the hybrid product unsuitable for commercial use from a taste perspective but acceptable from a dextrin utilization standpoint.

8.3.7 Cytoduction

Cytoduction is a specialized form of rare mating in which only the cytoplasmic components of the donor strain are transferred into the brewing strain; that is, the cell receives the cytoplasm from both parents but retains the nucleus of only one parent. The process of cytoduction requires the presence of a specific nuclear gene mutation designated Kar, for karyogamy defective. This mutation impairs nuclear fusion.51 Cytoduction can be used in three ways: substitution of the mitochondrial genome; introduction of DNA plasmids; or transfer of dsRNA species. When used in the substitution of the mitochondrial genome, it is possible to study the effects of these genetic elements on various cell functions. Mitochondrial substitution has been demonstrated to bring about variations in respiratory functions, cell surface activities, and various other strain characteristics.52 In addition, rare mating, used to introduce DNA plasmids, has been successful in the introduction of specific genetic elements constructed by gene-cloning experiments and to transfer the “zymocidal” or “killer” factor from laboratory haploid strains to brewing yeast strains, without altering the primary fermentation characteristics of the brewing yeast strain.53, 54

8.3.8 Mass Mating and Genome Shuffling

Mass mating is a technique where large numbers of cells, using different parental strains, are mixed and allowed to randomly mate. It can be used to create interspecific hybrids if there are strong markers that can be used for selection.55 Related to this technique is genome shuffling where repeated rounds of genetic recombination (using protoplast fusion or mass mating) are carried out to combine many different beneficial mutations in the same cell.29

8.3.9 Killer Yeast

In 1963, Bevan and Makower discovered the killer phenomenon in a S. cerevisiae strain that was isolated as a brewery contaminant.56 During the past five decades, intensive investigations of the various killer systems in yeast have resulted in substantial progress in many different fields of biology, providing important insights into basic and more general aspects of eukaryotic cell biology, virus–host cell interactions, and yeast virology. The topic has been recently reviewed by Liu et al.57

In Saccharomyces, killer strains secrete a protein toxin that is lethal to sensitive strains of the same genus and, less frequently, strains of different genera. Among the yeasts, killer, sensitive, and neutral strains have been described. The killer toxin of S. cerevisiae kills sensitive cells of the same species by disturbing the ion gradient across the plasma membrane after binding to the receptor at cell wall β 1,6-glucan.58 The “killer” character of Saccharomyces spp. is determined by the presence of two species of cytoplasmically located dsRNA plasmids. The M-dsRNA (1.0 to 1.8 kb) “killer” plasmid is killer-strain specific and codes for killer toxin and also for the immunity factor, which is a protein or proteins that make the host immune to the toxin (i.e., prevents self-killing). The L-dsRNA, which is also present in many “nonkiller” yeast strains, codes for the production of a protein that encapsulates both forms of dsRNA, thereby yielding virus-like particles. These virus-like particles are not naturally transmitted from cell to cell by any infection process. The killer plasmid behaves as a true cytoplasmic element, showing dominant non-Mendelian segregation. It depends, however, on a number of chromosomal genes for its maintenance in the cell and for expression. Cells of killer strains normally contain about 12 copies of the M-dsRNA and 100 copies of the L-dsRNA. The yeast can be cured of the M-dsRNA by growth at elevated temperature or by treatment with cycloheximide.

Based on the lack of cross-immunity, their molecular mode of action, and their killing profiles, toxin-producing S. cerevisiae killer strains have been classified into three major groups (K1, K2, and K28). Each secretes a unique killer toxin as well as a specific but as yet unidentified immunity component that renders the killer cells immune to their own toxins. The production of killer toxin K1, K2, or K28 is associated with the presence of a cytoplasmically inherited M-dsRNA satellite virus (designated ScV-M1, ScV-M2, or ScV-M28 for S. cerevisiae virus). This virus depends on the coexistence of a helper virus (L-A) to be stably maintained and replicated within the cytoplasm of the infected host cell.57

Brewing strains can be modified such that they are both resistant to killing by a zymocidal yeast and so that they themselves have zymocidal activity, thereby eliminating contaminating yeasts. Rare mating has been successfully employed to produce brewing killer yeast by crossing a brewing lager yeast with a Kar killer strain.53 Beer produced with this strain was acceptable but contained an ester note that was not present in the control. This suggested that the cytoplasm of the killer strain appeared to exert more influence on the brewing strain than originally predicted. A question often asked is whether the toxin is still active in the finished beer. The toxin is extremely heat sensitive, and a brewery pasteurization cycle of eight pasteurization units was shown to completely inactivate it.54

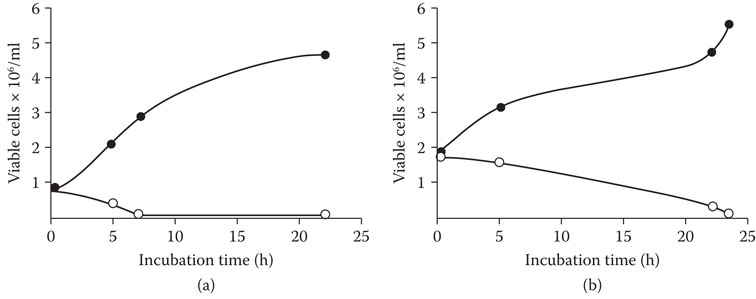

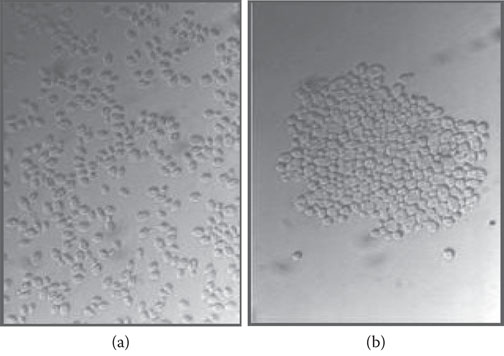

To determine the effect of the zymocidal lager strain on a typical brewery fermentation, “killer” lager yeast was mixed at a concentration of 10% with an ale brewing strain. The control was the ale strain mixed with 10% “nonkiller” lager. Within 10 h the killer lager strain had almost totally eliminated the ale strain. When the concentration of the killer yeast was reduced to 1%, within 24 h the ale yeast was again eliminated59 (Figure 8.8).

Figure 8.8 Effect of a ‘killer ‘ lager yeast on growth of a production ale yeast (12° P wort fermentation) at levels of 10% and 1%, assayed over a 24 hour period. (a) Legend control •--• : 90% ale yeast and 10% nonkiller lager yeast. Test ο—ο: 90% ale yeast and 10% killer lager yeast. (B) Legend control •--• : 90% ale yeast and 1% nonkiller lager yeast. Test ο—ο: 90% ale yeast and 1% killer lager yeast.

The speed at which this occurs may well make a brewer apprehensive about using such a yeast in the fermentation cellar, particularly where several yeasts are employed for the production of different beers. An error on an operator’s part in keeping lines and yeast tanks separate could have serious consequences. In a brewery with only one yeast strain, this would not be a cause for concern.

An alternative to the killer strain would be to produce a yeast strain that does not kill but is “killer resistant.” That is to say, it has received that genetic complement that makes it immune to zymocidal activity. The construction of such a yeast would perhaps be a good compromise because it would not itself kill; it would allay the brewer’s fear that this yeast might kill all other production strains in the plant; and, at the same time, it would not itself be killed by a contaminating yeast with “killer” ability.

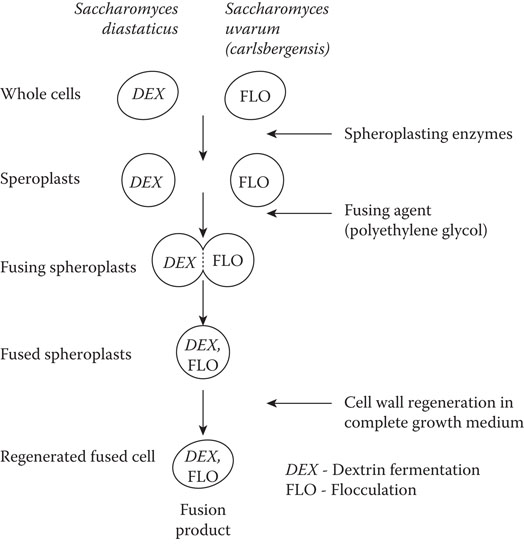

8.3.10 Spheroplast Fusion

Spheroplast (protoplast) fusion, first described by van Solingen and van der Plaat,60 is a technique that can be employed in the genetic manipulation of industrial strains and circumvents the mating/sporulation barrier. The method does not depend on ploidy and mating type and, consequently, has great applicability to brewing yeast strains because of their polyploid nature and absence of mating type characteristic. Examples of fusions with commercial brewing strains include the construction of a brewing yeast with amylolytic activity by the fusion of S. cerevisiae with S. diastaticus,59 a polyploid capable of high ethanol production by fusion of a flocculent strain with saké yeasts,61 and the construction of industrial strains with improved osmotolerance by fusion of S. diastaticus with S. rouxii.62, 63

Two yeasts, one a S. diastaticus strain capable of dextrin fermentation (DEX) and the other a flocculent brewing lager strain (FLO), were converted to spheroplasts by the enzymic removal of the cell wall (Figure 8.9). This resulted in osmotically fragile spheroplasts (protoplasts), which were maintained in an osmotically stabilized medium of 1 M sorbitol. The spheroplasting enzyme was removed by thorough washing, and the spheroplasts were mixed and suspended in a fusing agent consisting of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and calcium ions in buffer. Subsequently, the fused spheroplasts were induced to regenerate their cell walls and recommence division. This was achieved in solid media containing 3% agar and sorbitol. The action of PEG as a fusing agent is not fully understood, but it is believed to act as a polycation, inducing the formation of small aggregates of spheroplasts. The PEG can be replaced by an electrical current or by short electric field pulses of high intensity.64, 65

Figure 8.9 Spheroplast fusion to create novel industrial strains.

Although spheroplast fusion is an extremely efficient technique, it relies mainly on trial and error and does not modify strains in a predictable manner. The fusion product is nearly always different from both original fusion partners because the genome of both donors becomes integrated. Consequently, it is difficult to selectively introduce a single trait such as flocculation into a strain using this technique. For example, hybrid strains created by fusing lager yeast with S. diastaticus had unsatisfactory beer flavor/taste profiles, but could survive higher osmotic pressure and temperature and produced higher ethanol yields, and thus were of use to the fuel alcohol industry.66, 67 Similarly, a hybrid from a saké yeast with a brewing strain fermented high-gravity wort effectively, but the beers contained more ethanol and esters than the brew produced with the parental brewing strain.68

8.3.11 Recombinant DNA

Although the techniques of hybridization, rare mating, and spheroplast fusion have met with success, they have their limitations, the principal one being the lack of specificity in genetic exchange. Since 1978, when a transformation system for yeast became available,69 great strides have been made in yeast transformation. It is now possible to modify the genetic composition of a brewing yeast strain without disrupting the many other desirable traits of the strain, and it is possible to introduce genes from many other sources.

The applications of recombinant DNA methods to brewing and wine yeast have been reviewed in detail.28–30, 70 Examples include the production of brewing strains with glucoamylase, α-amylase, or pullulanase genes inserted from various sources. Work has been carried out cloning genes coding for β-glucanase into brewing strains. Research has been conducted on improving fermentation efficiency by increasing the gene dosage of the MAL genes for maltose utilization. The flocculation properties of brewing strains have been modified using cloning techniques. There is much interest in the use of transformation in terms of producing strains that have a reduced capacity to produce compounds such as diacetyl, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and dimethyl sulfide (DMS) as well as the increased ability to produce higher levels of esters such as isoamyl acetate. Genes for this cloning work come from a number of sources including Aspergillus niger, Bacillus subtilis, and Trichoderma reesii.

Strains have been constructed with the desirable traits expressed, but these strains are not used commercially at this time as there is still concern over consumer acceptance of beer made using a recombinant DNA yeast. The availability of alternative, inexpensive, traditional solutions for many of the problems it was hoped a genetically modified (GM) yeast could solve, such as inexpensive sources of β-glucanase and gluco- and α-amylase, has also retarded the implementation of these new strains.

There has been reluctance to use recombinant DNA technology in the brewing industry. The first genetically modified organism (GMO) for brewing to receive official government blessing was reported in the United Kingdom in 1994.70 However, this has not been used commercially to date. A gene coding for a glucoamylase was transferred from a diastatic strain of Saccharomyces to a brewing strain of Saccharomyces. The construct was considered “self-cloning” and was thus not treated as a recombinant organism, but this is not currently the legal designation in all countries.

The first commercially sold GMO-labeled beer in the world was launched in Sweden in 2004. Rather than using a recombinant DNA yeast, however, the beer was promoting the GM corn used in its manufacture. The company claimed to have launched the first beer to use genetic modification as a marketing tool. The beer, brewed in the southern Swedish town of Ystad, was made from corn—supplied by U.S. biotech giant Monsanto—genetically modified to resist attacks from pests.71

Researchers have produced strains using recombinant DNA that showed a reduction in diacetyl production by ILV2 gene disruption and BDH1 expression72 in laboratory fermentations. Strains have also been engineered to display α-acetolactate decarboxylase from Acetobacter aceti ssp. xylinum, and use of these strains resulted in a lower final diacetyl concentrations in the beers produced in the laboratory.73

Although it is now relatively easy with the strides made in the DNA technologies to manipulate yeast in the laboratory, and therefore to construct a GM yeast that has many additional useful brewing properties, the brewing industry today is still very hesitant to implement the use of a GM yeast due to the negative consumer perceptions regarding the use of such a yeast for beer production. The improvement of yeast for commercial beer production still relies on the more conventional techniques of breeding and directed evolution, although the newer gene editing techniques such as CRISPR will no doubt renew the discussion on, “What is a GM yeast?” and “What is the public willing to accept?”74

8.4 YEAST NUTRITION

8.4.1 Oxygen Requirements

Molecular oxygen has a multifaceted role in yeast physiology. Brewer’s yeast is a facultative aerobe. Wort fermentation in beer production, on the other hand, is largely anaerobic. However, this is not the case when the yeast is pitched into the wort, and at this time, some oxygen must be made available to the yeast. There is a need for oxygen because brewing yeasts require molecular oxygen to synthesize sterols and unsaturated fatty acids, which are present in wort but at suboptimal concentrations. Thus, yeast is capable of growth under strictly anaerobic conditions only when there is an exogenous supply of these compounds. Under aerobic conditions, the yeast can synthesize sterols and unsaturated fatty acids de novo from carbohydrates. Sterols and unsaturated fatty acids are abundant in malt, but normal manufacturing procedures prevent them from passing into the wort. When ergosterol and an unsaturated fatty acid, such as oleic acid, are added to wort, the requirement for oxygen disappears.

Cells prepared aerobically can grow to some extent anaerobically. Growth of yeast during the anaerobic phase of fermentation dilutes the preformed sterol pool between the mother cell and progeny. Cells can continue to divide until sterol depletion limits growth. Optimization of the dissolved oxygen (DO) supply for any brewing yeast strain is important to achieve good fermentation and a high-quality end product.75

The quantity of oxygen required for fermentation is yeast strain dependent. Ale yeast have been classified into four groups based on the oxygen concentration required to produce satisfactory fermentation performance.76 Similar groupings for lager yeast were reported by Jacobsen and Thorne.77 The amount of oxygen required for sterol synthesis and satisfactory fermentation varies widely, not only with the particular yeast employed but also with time of addition, whether in increments, and so on. With higher Plato worts, it is more difficult to ensure that there is enough oxygen available for the yeast, and pure sterile oxygen rather than air may be necessary.

Ensuring the correct yeast oxygenation at pitching ensures good yeast growth, full attenuation, and that the desired flavor compounds are produced. A general guideline on wort oxygenation is 1 ppm of oxygen for each degree Plato. Under-oxygenation is a bigger concern than a “slight” over-oxygenation because the yeast at pitching will very quickly remove all of the oxygen present in the wort. Excessive oxygen however will result in too much yeast growth and accompanying flavor issues. When air is used to oxygenate, 8 ppm is the maximum amount that will dissolve in a 10°Plato wort78 at 15°C. When higher wort values of oxygen are needed, pure oxygen must be used, and it should be remembered that, as the temperature and gravity of the wort increases, oxygen solubility decreases. (Further details in Chapters 9 and 14.)

8.4.2 Lipid Metabolism

Lipids are sparingly soluble in water but readily soluble in organic solvents. They are an integral part of the plasma membrane, where they are involved in the regulation of movement of compounds in and out of the cell, regulation of the activities of membrane-bound enzymes, and enhancement of the yeast’s ability to resist high ethanol concentrations.79 Saccharomyces yeast are able to take up fatty acids at low concentrations via facilitated diffusion and at high concentrations via simple diffusion.

Free fatty acids are powerful detergents and once taken up by the cell are quickly esterified to coenzyme A to reduce their potential for nonspecific enzyme inactivation. The addition of lipids, especially ergosterol and unsaturated long-chain fatty acids, has a pronounced effect on the growth and metabolism of yeast. The addition of unsaturated fatty acids (oleic, linoleic, and linolenic) has been reported to be a mechanism for the regulation of the concentration of flavor-active compounds in beer.80

The oxygen content of the wort at pitching is important with regard to lipid metabolism, yeast performance, and beer flavor. Under-aeration leads to suboptimal synthesis of essential membrane lipids and is reflected in limited yeast growth, a low fermentation rate, and concomitant flavor problems. Over-aeration results in overextending nutrients for the production of unnecessary yeast biomass, thus lowering fermentation efficiency because of the excess biomass and lower ethanol production. Negative effects on beer flavor and stability can result from over-aeration.

Studies have shown that the key factor in the successful application of wort or yeast aeration techniques is the physiological state of the yeast harvested at the end of the wort fermentation cycle.81 It has been suggested that the current regimes of yeast management produce variations in the physiological condition of the yeast, and that fluctuations in the ratio of glycogen to sterol may result in fermentation inconsistency, unless appropriate pitching rates and wort oxygen concentrations are selected. Devuyst et al.81 describe a procedure where the cropped yeast is suspended in water and aerated until maximum oxygen uptake rate is reached. The authors suggest that the formation of yeast sterols during the oxygenation process is fueled by glycogen dissimilation and that when the yeast is subjected to vigorous oxygenation pre-pitching, it provides a pitching yeast of standardized physiology. They believe that the best approach to improve fermentation control is to eliminate variability and that the oxygenation process they recommend produces pitching yeast of consistent and stable physiology, with no requirement for subsequent wort oxygenation to achieve satisfactory fermentation performance.

High metabolic activity of the cropped yeast is critical for efficient mobilization of reserve materials.82 Boulton et al.83 describe experiments to produce pitching yeast, replete in sterol, and thereby ostensibly remove the requirement for subsequent wort aeration. Yeast suspended in beer, cropped from the fermenter, was forcibly exposed to oxygen and was allowed to accumulate sterol. They found that it was necessary to increase pitching rates by 30% in order to achieve the same vessel residence times as control fermentations. Oxygenated yeast withstood the rigors of storage at elevated temperature less well than the untreated control.

Sterols are taken up by the yeast only while the yeast is growing under aerobic conditions. They are not taken up by stationary phase cells under anaerobic conditions. The poor physiological quality of cropped yeast is due to the depletion of sterols and unsaturated fatty acids. To restore the physiological activity of the plasma membrane, the yeast must take up its requirements from the wort, or synthesize the required lipids de novo, or convert them from the available pool of precursors. Callaerts et al.84 oxygenated an anaerobic brewing yeast to improve its physiological condition and measured the glycogen, sterol, and trehalose content of the yeast cell over time. In addition to the degradation of glycogen, and the expected synthesis of sterols, they observed an unexpected accumulation of trehalose and found that the trehalose and sterol concentrations correlated. The authors speculated that perhaps excessive contact with oxygen provoked a certain stress for the yeast and that the trehalose acted as a general stress protectant.85, 86

Fujiwara and Tamai87 showed that adequate aeration accelerates lager yeast fermentation and inhibits acetate ester formation. They demonstrated that complete depletion of trehalose adversely influences fermentation properties and ester synthesis and warned that aeration or agitation should be avoided during storage as high levels of dissolved oxygen enhanced the consumption of trehalose. Excess aeration resulted in trehalose exhaustion and did not stimulate anaerobic growth or decrease the synthesis of volatile esters. They suggest that intracellular trehalose concentration could be used as a marker that can reflect the appropriate level of aeration. Bleoanca et al.88 examined glycogen and trehalose protection mechanisms in brewing yeast as a response to oxidative stress and observed differences in the patterns of response based on the particular strain of yeast. (Further details in Chapter 14.)

8.4.3 Uptake and Metabolism of Wort Carbohydrates

When yeast is pitched into wort, it is introduced into an extremely complex environment consisting of simple sugars, dextrins, amino acids, peptides, proteins, vitamins, ions, nucleic acids, and other constituents too numerous to mention. One of the major advances in brewing science during the past 35 years has been the elucidation of the mechanisms by which the yeast cell, under normal circumstances, utilizes, in a very orderly manner, the plethora of wort nutrients.

Wort contains the sugars sucrose, fructose, glucose, maltose, and maltotriose, together with dextrin material. In the normal situation, brewing yeast species (i.e., S. cerevisiae and S. pastorianus) are capable of utilizing sucrose, glucose, fructose, maltose, and maltotriose in this approximate sequence, although some degree of overlap does occur. The majority of brewing strains leave the maltotetraose and other dextrins unfermented, but S. diastaticus is able to utilize some of the dextrin material due to the excretion of glucoamylase, which can hydrolyze smaller dextrins to metabolizable glucose.

The initial step in the utilization of any sugar by yeast is usually either its passage intact across the cell membrane or its hydrolysis outside the cell membrane, followed by entry into the cell by some or all of the hydrolysis products. Maltose and maltotriose are examples of sugars that pass intact across the cell membrane, whereas sucrose is hydrolyzed by an enzyme (invertase) located in the periplasmic space between the yeast cell wall and yeast cell membrane, and its hydrolysis products (glucose and fructose) are taken across the membrane into the cell (Figure 8.10). Dextrin material from wort is hydrolyzed outside of the yeast cell and simple sugars such as glucose can then enter the cell by facilitated diffusion.

Figure 8.10 Carbohydrate uptake by Saccharomyces spp.

Brewing yeast has several mechanisms for sensing the nutritional status of the environment, allowing it to adapt its uptake and metabolism to the surrounding conditions.89 Glucose and sucrose are always consumed first. Sucrose is hydrolyzed into glucose and fructose, and the monosaccharides are taken up by facilitated diffusion involving common membrane carriers.90 The yeast prefers glucose over fructose. Glucose slows down the uptake of fructose as the sugars have the same carriers, and these have a greater affinity for glucose. The presence of glucose and fructose in a fermentation causes the repression of gluconeogenesis, the glyoxylate cycle, respiration, and the uptake of less preferred carbohydrates, such as maltose and maltotriose. In addition, these two sugars activate cellular growth, mobilize storage compounds, and lower cellular stress resistance.91 Because yeast consumes fructose at a different rate from glucose, when large amounts of sucrose are used as adjunct, it can result in some of the very sweet fructose remaining in the beer and affecting the flavor profile. (Further details of adjuncts are in Chapter 6.)

Maltose and maltotriose are the major sugars in brewer’s wort and, therefore, the brewing strain’s ability to use these two sugars is vital and depends upon the correct genetic complement to transport the two sugars across the cell membrane into the cell. Once inside the cell, both sugars are hydrolyzed to glucose units by the α-glucosidase system.

8.4.4 Maltose and Maltotriose Uptake

Maltose fermentation in Saccharomyces requires at least one of five unlinked MAL loci. These five nearly identical regions are located at telomere-associated sites on different chromosomes92: MAL1, chromosome VII; MAL2, III; MAL3, II; MAL4, XI; and MAL6, VIII. Different maltose-fermenting strains carry at least one of these fully functional alleles, but often two or more loci are present in a strain. A typical MAL locus is a cluster of three genes, all of which are required for maltose fermentation. Gene 1, a member of the 12-transmembrane domain family of sugar transporters, encodes a maltose permease transporter; gene 2 encodes maltase (α-glucosidase); and gene 3 encodes the regulator/activator of transcription of the other two genes.

The expression of maltose permease and α-glucosidase are induced by maltose and repressed by glucose.93 The constitutive expression of the maltose transporter gene is critical, and the maltose-fermentation ability of brewing yeasts depends mostly on maltose permease activity.94 The maltose uptake system is an active process requiring cellular energy. Uptake involves a proton symport system, and potassium is exported to maintain electrochemical neutrality.

Brewing strains carry multiple copies of the maltose transporter gene, and it is speculated that the high number of MAL loci in brewing strains may have evolved as a mechanism to adapt to the high maltose environment of wort, giving the yeast strain a selective advantage.95

There are three different transporters known to carry maltose (Mal, Agt1, and Mtt1).96 Maltose and maltotriose can share the same transporter, the gene for which is closely linked to the maltase gene, and it is believed that brewing strains probably contain several copies of each of the two genes scattered as pairs around several different chromosomes. Yeast strains constructed with multiple MAL genes show increased rates of maltose uptake up from wort.97

The AGT1 (MAL1) permease is capable of transporting maltotriose as well as maltose, but although it is 57% identical to the MAL 6 permease gene, the MAL 6 permease gene cannot transport maltotriose—only maltose.98 More recent studies examining maltose and maltotriose uptake in brewing strains have shown that S. pastorianus strains utilize maltose more efficiently than S. cerevisiae strains99 and that there appear to be two subgroups of lager strains, which differ in sugar utilization due to the presence or absence of specific transmembrane transporters.100

During the brewing process, the rate and extent of wort sugar uptake are controlled by numerous factors including the yeast strains employed; the concentration and category of assimilable nitrogen; the concentration of ions; the fermentation temperature; the pitching rate; the tolerance of yeast cells to ethanol; the wort gravity; the wort oxygen level at yeast pitching and the wort sugar spectrum. These factors influence yeast performance either individually or in combination with others. The kinetics of maltose transport by an ale and a lager strain are affected by the presence of other sugars, ethanol, high gravity wort, and temperature, but maltose uptake is the dominant factor controlling the rate of wort maltose utilization.101

The uptake and hydrolysis of maltose and maltotriose from the wort is also dependent on the glucose concentration. When the glucose concentration is high (greater than 1% [w/v]), the MAL genes are repressed, and only when 40% to 50% of the glucose has been taken up from the wort will the uptake of maltose and maltotriose commence. Thus, the presence of glucose in fermenting wort exerts a major repressing influence on the wort fermentation rate. Mutants of brewing strains have been selected in which the maltose uptake was not repressed by glucose and, as a consequence, these strains exhibited increased fermentation rates.102

The presence of residual maltotriose in beer is not only due to the inability of yeast to utilize the sugar but also to the lower affinity for maltotriose uptake in conjunction with deteriorating conditions present at the later stages of fermentation. Indeed, transport, rather than hydrolysis of maltose, is the rate-limiting step determining fermentation performance.103 Meneses et al.104 used a model fermentation system to define the abilities of 25 industrial S. cerevisiae strains to utilize maltose and sucrose in the presence of glucose and fructose. Their survey exposed a number of novel phenotypes that could be harnessed as a means of producing strains with rapid and efficient utilization of fermentable carbohydrates. MTT1 (MTY1) is a transporter gene with a higher affinity for maltotriose than maltose.105 Magalhães et al.100 commented on how MTT1 plays an integral role in lager strains in terms of their ability to ferment effectively at lower temperatures.

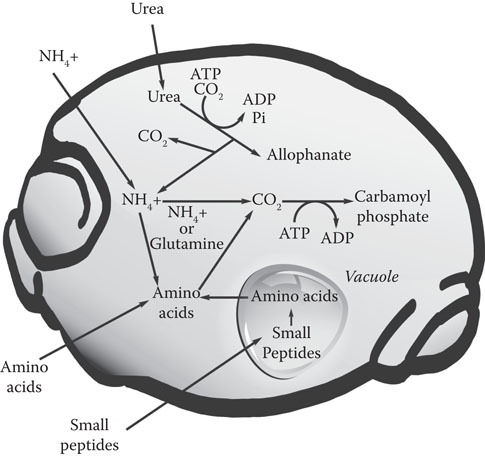

8.4.5 Uptake and Metabolism of Wort Nitrogen

The nitrogen content of a yeast cell varies between 6% and 9% (w/w), and active yeast growth requires nitrogen, mainly in the form of amino acids, for the synthesis of new cell proteins and other nitrogenous components. Nitrogen uptake slows or ceases later in the fermentation as yeast multiplication stops. Wort nitrogen levels affect yeast growth and, at levels below 100 mg/L free amino nitrogen, growth is nitrogen-dependent. In wort, the main source of nitrogen for the synthesis of proteins, nucleic acids, and other nitrogenous cell components is the variety of amino acids formed from the proteolysis of barley protein. Lager wort nitrogen has been reported as approximately 30% to 40% amino acids, 30% to 40% polypeptides, 20% protein, and 10% nucleotides.106 Assimilable yeast nitrogen is the aggregation of the individual wort amino acids and small peptides (di-, tripeptides).107 These compounds are essential for the formation of new amino acids, synthesis of new structural and enzymic proteins, cell viability and vitality, fermentation rate, ethanol tolerance, and carbohydrate uptake. With all malt worts, there is usually enough nitrogen present, but with the use of adjuncts and high gravity brewing, the nitrogen levels must be monitored to ensure that the levels are adequate for yeast growth.

Wort contains 19 amino acids and, under brewery fermentation conditions, brewing yeast takes them up in an orderly manner, with different amino acids being removed at various points in the fermentation cycle and first described by Jones and Pierce108 in 1967. There are at least 16 different amino acid transport systems in yeast. In addition to permeases specific for individual amino acids, there is a general amino acid permease (GAP) with broad substrate specificity. Short chains of amino acids in the form of di- or tripeptides can also be taken up by the yeast cell. Uptake patterns are very complex, with a number of regulatory mechanisms interacting109 (Figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 Nitrogen uptake by yeast.

Amino acids, like a number of sugars, do not permeate freely into the cell by simple diffusion; instead, there is a regulated uptake facilitated by a number of transport enzymes. At the start of fermentation, arginine, aspartic acid, asparagine, glutamic acid, glutamine, lysine, serine, methionine, and threonine are absorbed rapidly.109 The other amino acids are absorbed only slowly—or not until later in the fermentation. Under strictly anaerobic conditions, such as those encountered late in a brewery fermentation, proline, the most plentiful amino acid in wort, has scarcely been assimilated by the end of the fermentation, whereas over 95% of the other amino acids have disappeared. Proline is still present in the finished product at 200 to 300 mg/ml; however, under aerobic laboratory conditions, proline is assimilated after exhaustion of the other amino acids.

The inability of Saccharomyces spp. to assimilate proline under brewery conditions is the result of several phenomena. When other amino acids or ammonium ions are still present in the wort, the activity of proline permease, the enzyme that catalyzes the transport of proline across the cell membrane, is repressed. Once inside the cell, the first catabolic reaction of proline involves proline oxidase, which requires the participation of cytochrome c and molecular oxygen. By the time the other amino acids have been assimilated, thus removing the repression of the proline permease system, conditions are strongly anaerobic. As a result, the activity of proline oxidase is inhibited, and proline uptake does not occur.

Yeast strains exhibit different amino acid absorption rates and preferences. Amino acid uptake by yeast depends on a number of factors, including percentage of total assimilable nitrogen, individual amino acid concentrations, quality and absorption rate, amino acid competitive inhibition, yeast strain and generation, and yeast growth phase.

Free amino nitrogen (FAN) refers to free α-amino nitrogen and is expressed as milligrams N per liter assimilable nitrogen. FAN includes all of the amino acids minus proline. (Proline is not an α-amino acid and is not utilizable by Saccharomyces under anaerobic conditions.) FAN affects a great range of other fermentation factors, such as cell growth, biomass, viability, pH, and attenuation rate. The FAN target is usually stated as 160 to 190 mg/l wort (based on a 1040 wort). Optimization of the nitrogen content of wort is a complex issue as it is not only the initial FAN content in the wort but also the equilibrium of amino acids and ammonium ions, as well as other still undefined fermentation parameters, all of which will influence the final beer flavor.

S. cerevisiae is able to use different nitrogen sources for growth but not all nitrogen sources support growth equally well. Yeast prefers to use ammonium salts,110 but these are present in wort in only small amounts, and yeast cannot use inorganic nitrogen. S. cerevisiae selects nitrogen sources that enable the best growth by a mechanism called nitrogen catabolite repression. This mechanism is designed to prevent or reduce unnecessary divergence of the cell’s synthetic capacity to form enzymes and permeases for nonpreferred nitrogen sources.111, 112 The utilization of amino acids and the formation of fermentation by-products such as higher alcohols, esters, diketones, and organic acids, and their importance to beer flavor is discussed in later sections.

8.4.6 Uptake of Wort Minerals and Vitamins by Yeast

Yeast requires a number of vitamins and minerals for optimum growth and fermentation, and the levels needed for healthy yeast are adequate in most worts. Zinc is an essential element for yeast as it acts as a cofactor for many yeast enzymes, including the zinc-metalloenzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, the terminal step in yeast alcoholic fermentation. A lack of zinc can prevent a yeast from budding. The amount of zinc that a strain requires is determined to some extent by the particular strain’s genetic makeup. Some strains are very sensitive to low levels of zinc in the wort,113 and levels required for optimal fermentation range from 0.48 to 1.07 ppm. Problem fermentations can often be resolved by the addition of a source of bioavailable zinc, such as zinc chloride or sulfate, or yeast foods. (Further details in Chapter 10.) If magnesium is not present in sufficient amounts, the yeast cannot grow. Magnesium is important for key metabolic processes and is directly involved in ATP synthesis. Like zinc, magnesium also protects the cell from stress.114 Sufficient manganese in the wort is important when the wort is deficient in FAN. The control of flavor for beer consistency depends on a number of the metallic ions in the wort, where either not enough or too much can pose problems.115 Most of the yeast’s vitamin requirements can be met by the wort. Hucker et al.116 review and provide in-depth information on the roles of thiamine and riboflavin in wort.

8.5 YEAST EXCRETION PRODUCTS

One of the major excretion products produced during the fermentation of wort by yeast is ethanol. This primary alcohol impacts the final beer mainly by intensification of the alcoholic taste and aroma and by imparting a warming character. However, it is the types and concentrations of the other yeast excretion products that primarily determine the flavor of the product. The formation of these excretion products depends on the overall metabolic balance of the yeast culture, and there are many factors that can alter this balance and consequently the flavor of the product. Yeast strain, incubation temperature, adjunct level, wort pH, buffering capacity, wort gravity, oxygen, pressure, and so on, are all influencing factors.

Some volatiles are of great importance and contribute significantly to beer flavor, while others are of importance merely in building the background flavor of the product. The composition and concentration of beer volatiles depend upon the raw materials used, brewery procedures in mashing, fermentation parameters, and the yeast strain employed. The following groups of substances are to be found in beer: alcohols, esters, carbonyls, organic acids, sulfur compounds, amines, phenols, and a number of miscellaneous compounds.

8.5.1 Alcohols

In addition to ethanol, there several other alcohols found in beer, and these higher alcohols or fusel oils contribute significantly to flavor.117, 118 Their formation is linked to yeast protein synthesis. Higher alcohols can be synthesized via two routes: de novo from wort carbohydrates (the anabolic route) or as by-products of amino acid assimilation (the catabolic route). The contribution of the two routes is influenced by a number of factors, but generally, when low levels of amino acids are available, the anabolic route predominates and when high concentrations of amino acids are present the catabolic pathway is favored. For n-propanol, there is only the anabolic route as there is no corresponding amino acid for the catabolic pathway. The transport of branched-chain amino acids is important in brewing as the metabolites of these compounds are converted to higher alcohols. The composition of the wort, in particular the amino nitrogen content, influences the formation of these compounds. The yeast strain chosen for fermentation is of great significance and the levels of alcohols are dependent upon the fermentation temperature, with an increase in temperature resulting in increased concentrations of higher alcohols in the beer.

8.5.2 Glycerol

After ethanol and CO2, glycerol is the next highest compound produced by the yeast and present in beer. A 5% (v/v) ethanol beer will contain approximately 0.2% (v/v) glycerol. Glycerol has a sweet taste and thus contributes some sweetness to a beer’s flavor profile and is a palate contributor. Cells produce glycerol and accumulate it intracellularly, where it provides protection against various stress factors. It acts as an osmoprotectant for the cell, and it also protects against temperature stress.

The main pathway of glycerol formation is by the reduction of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) to glycerol. It is also acts as a redox sink for the regeneration of cytosolic NAD+ from NADH. Yeast can be induced to overproduce glycerol in a number of ways, such as the addition of sulfite and salts to the growth media or by a pH change to above pH 7. Yeast can also catabolize glycerol, using it as a sole carbon source for growth.119, 120

8.5.3 Esters

Of the flavor-active substances produced by yeast, esters represent the largest and most important group. Esters are responsible for the highly desired fruity/floral character of beer. Esters are formed intracellularly by an enzyme-catalyzed condensation reaction between two co-substrates, a higher alcohol and an activated acyl-coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) molecule. The regulation of ester synthesis is complex (Figure 8.12). See reviews on this topic by Verstrepen et al.121 and Pires et al.122

Figure 8.12 Formation of esters and fatty acids as byproducts of yeast growth.

Beer contains more than 100 different esters, with the key ones being ethyl acetate (fruity/solvent), isoamyl acetate (banana/apple/fruity), isobutyl acetate (banana/fruity), and 2-phenylethyl acetate (honey/rose) aroma. The C6 to C10 medium-chain fatty acid ethyl esters, such as ethyl hexanoate (ethyl caproate) and ethyl octanoate (ethyl caprylate), have sour apple/aniseed aromas. Ethyl esters are present in the highest quantity presumably because ethanol is present in large amounts.

A number of factors have been found to influence the amount of esters formed during fermentation. The yeast strain is very important as are the fermentation parameters of temperature, pitching rate, and top pressure. Wort composition affects ester production; assimilable nitrogen compounds, the concentration of carbon sources, dissolved oxygen, and fatty acids all have an effect. Wort components that promote yeast growth tend to decrease ester levels.123 High-gravity worts can lead to disproportionate amounts of ethyl acetate and isoamyl acetate,124, 125 and the use of large-scale cylindro-conical fermentation vessels causes a dramatic drop in ester production, with a resultant imbalance in the ester profile.126 In order to obtain better control over ester synthesis, much research is being focused on the elucidation of the biochemical mechanisms of ester synthesis and on the factors influencing ester synthesis rates (further details in Chapters 9 and 14).

8.5.4 Sulfur Compounds