Introduction

Strategic management research has traditionally posited that firms are separate entities that compete with each other to achieve performances that are higher vis-à-vis their rivals. As separate entities, firms have conflicting interests and experiment a win-lose game in which the winner of the competition race will be only one (Dagnino, 2016).

Due to technological and market uncertainties that firms face in a hypercompetitive arena (Afuah, 2000), in the late 1980s the business world showed that firms increasingly tend to cooperate with suppliers, buyers, and/or partners that are also their major competitors (Dowling et al., 1996). However, while inter-firm relationships could “incorporate elements of both traditional competitive relationships and collaborative relationships” (Dowling et al., 1996: 155), for many years strategy research has seemingly been focused on polarized relationships that are either simply competitive or cooperative (Smith et al., 1995; Wu, 2014). Therefore, strategy inquiry has continued to look at competition and cooperation in a separate fashion and as alternative strategies.

Following the seminal contribution of Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996), coopetition—epitomizing the simultaneous coexistence of cooperation and competition—has received increasing acknowledgment in the management realm. During the last decade, together with its remarkable and continuous diffusion in practice, coopetition research has experienced an impressive expansion. On the one hand, the proliferation of studies on coopetition characteristics and the various methods of inquiry that scholars have adopted (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed) are unambiguous signals of the vigor that this research area has progressively assumed. On the other hand, coopetition literature takes multiple theoretical angles and presents mixed empirical findings (Table 6.1 displays the most influential articles, book chapters, and conference papers on coopetition to date). Taken together, these conditions motivate the need to perform a critical overview of the coopetition literature.

By detecting the four main phases of coopetition development in the last two decades, this study aims to outline a reasoned understanding of existing coopetition studies. Specifically, we ask: how has coopetition literature evolved over time? And to what extent is coopetition literature converging on some specific issues? As anticipated, this overview is targeted at detecting the key phases in coopetition research and to suggest some hints on its convergence on few specific issues. In such a way, it will be possible to capture the critical aspects underlying the emergence of coopetition research as well as to disentangle its current theoretical and empirical advancements.

Table 6.1The most influential articles, book chapters, and conference papers on coopetition

Note: we selected papers located on Google Scholars by searching for “coopetition” or “co-opetition” in the title (15/09/2017). For papers published in the time frame spanning from 1996 to 2010 (from phase 1 to phase 3), we considered 100 citations as a cut-off. Since citations are biased by time elapsed from the time when articles were published, for papers published in the time frame spanning from 2011 to 2016 (phase 4), we considered 75 citations as a cut-off. We removed five articles that did not contribute to coopetition research.

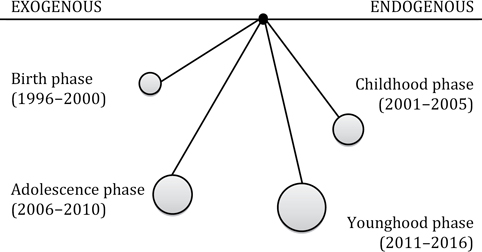

Drawing on Hoskisson et al. (1999), this chapter shows that the evolution of coopetition literature may be depicted through the metaphor of the “swing of a pendulum.” Actually, it is possible to single out alternate phases in which the coopetition literature emphasizes the influx of exogenous aspects, such as the context and the interactions with actors in the choice of cooperating with rivals, with other phases in which the emphasis is instead on endogenous aspects, such as firms’ internal resource deployment to manage the tensions underlying coopetitive relationships.

Research path

Our research path relates to performing a temporal analysis of the key articles contributing to the evolution of coopetition research. As anticipated earlier, to illustrate the path of evolution characterizing coopetition literature, we adopt the metaphor of the swing of a pendulum by drawing on Hoskisson et al. (1999). As known, the pendulum is a weight that is suspended from a fixed pivot so it can swing freely back and forth thanks to gravity. When the pendulum is sideways from its center position, it is exposed to a restoring force that will accelerate it back and report it to the center position. The restoring force and the pendulum’s mass allow it to swing back and forth. Since the swing of a pendulum has typically been used to identify time periods and phases, we argue that it is helpful to portray the evolutionary path of coopetition literature in the last two decades by reframing the state of the art of coopetition studies through the metaphor of the swing of a pendulum. Specifically, by “decomposing time lines into distinct phases where there is continuity in activities within each phase and discontinuity at the frontiers” (Langley, 2010: 919), we partition the time scale of the bulk of coopetition literature into four distinct phases. This methodological choice allows us to extricate, for each phase, the continuities that conceptual and empirical coopetition studies share, as well as to unveil the discontinuities in issues (Langley & Truax, 1994).

The four phases we identify are reported as follows:

1.the birth phase: early development of coopetition (1996–2000);

2.the childhood phase: grasping the balance between competition and cooperation (2001–2005);

3.the adolescence phase: understanding benefits and pitfalls of coopetitive strategies (2006–2010);

4.the younghood phase: managing coopetitive tensions (2011–2016).

Figure 6.1 illustrates the key phases we have identified through the metaphor of the swing of a pendulum. As mentioned before, it understands them by using the two perspectives, looking respectively at the endogenous and exogenous sides of coopetition. The endogenous side of coopetition considers how firms organize themselves to deal with coopetition. It focuses on the role of firms’ resources and the organizational structures firms can use to manage cooperation with their rivals. In a nutshell, the endogenous side takes into account the internal mechanisms firms develop to manage coopetition and achieve a coopetitive advantage.

The exogenous side of coopetition considers the relational aspects related to the role of the external contexts in which coopetition occurs, and the interactions occurring among coopetitive firms. In this vein, the focus rests on the context in which firms operate and the actions rivals develop, thereby affecting their performance. Authors pay particular attention to “the dependence between competitors due to structural conditions [that] can explain why competitors cooperate and also why they compete” (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000: 416). Starting in the next section, we will review the main studies epitomizing each phase and discuss the swing of the pendulum in coopetition research. Table 6.2 offers a synopsis of each phase of coopetition literature identified.

Table 6.2Synopsis of the four key phases in coopetition research

| Phase | Side of Pendulum | Characteristic Traits | Prevalent Methodology | Influential Studies |

Birth (1996–2000); early development of coopetition |

Exogenous |

Conceptualization of coopetition and recognizing the conditions supporting the emergence of coopetition; emphasis on contexts and actors involved |

Theoretical development and few case studies |

Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996; Dowling et al., 1996; Bengtsson & Kock, 2000 |

Childhood (2001–2005); grasping the balance between competition and cooperation |

Endogenous |

How firms organize themselves to develop a coopetition strategy |

Case studies |

Tsai, 2002; Luo, 2005, Dagnino & Padula, 2002 |

Adolescence (2006–2010); benefits and pitfalls of coopetitive strategies |

Exogenous |

Consequences of coopetitive strategies as concerns benefits and pitfalls of coopetitive strategies in different empirical settings |

Case study; network analysis |

Dagnino, 2009; Gnyawali et al., 2006; Gnyawali & Park, 2009 |

Younghood (2011–2016); managing coopetitive tension |

Endogenous |

Theorizing coopetition and finding new solutions to deal with coopetitive tensions as regards characteristics of industries and actors |

Case study and econometric analysis |

Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Gnyawali & Park, 2011; Ritala, 2012, Park et al., 2014 Tidström, 2014 |

The birth phase: Early development of coopetition (1996–2000)

The early development phase encompasses coopetition studies published from 1996 to 2000, thereby recognizing as seminal the following pieces: Afuah (2000), Bengtsson and Kock (2000), Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996), Carayannis and Alexander (1999), Carayannis and Roy (2000), and Dowling et al. (1996). Such contributions devote their attention to introducing the concept of coopetition and to digging deeper into the logic underlying the emergence of such a “new” strategy.

In this phase, there are three main theoretical lenses coopetition studies essentially takes: resource dependence theory, transaction cost economics, and game theory. Authors intend to unveil the nature and the kinds of inter-firm relationships that embrace competition and cooperation (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Dowling et al., 1996). Thus, they offer a preliminary sketch explaining why coopetition occurs, its antecedents, and the moves and countermoves firms should develop to manage coopetition. For instance, Dowling et al. (1996) identify the types of multifaceted relationships occurring under coopetition (i.e., buyers or sellers in “direct competition,” buyers or sellers in “indirect competition,” and partners in competition), and the strategic dilemma they present. Similarly, Bengtsson and Kock (2000) identify three types of coopetitive relationships (i.e., cooperation-dominated relationships, equal relationships, and competition-dominated relationships) based on the predominance of competition or cooperation over the other.

In unveiling the antecedents of coopetition, authors call attention to the exogenous dimensions of coopetition that are connected to industry concentration, munificence of resources, interconnectedness, opportunism, asset specificity, and so on (Dowling et al., 1996). Interestingly, Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) extend the analytical spectrum of previous cooperation research by defining the set of actions and responses that firms can deploy based on the pay-offs they can achieve through their choices. Furthermore, Afuah (2000: 388) argues that, “if a firm has come to depend on its coopetitor’s capabilities, obsolescence of such capabilities can result in lower performance for the firm.”

From a methodological point of view, it is worth noting that the bulk of the papers published in this initial phase are conceptual pieces. At this stage, it was important to acknowledge the complexity underlying coopetitive relationships in which “two diametrically different logics of interaction” take place (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000: 412), as well as to understand which aspects of competition and cooperation emerge, so as to identify the essential features of coopetition (Afuah, 2000; Bengtsson & Kock, 2000). On the other hand, empirical evidence is limited and is mainly aimed at providing insightful examples of coopetition (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Dowling et al., 1996).

From the viewpoint of competition/cooperation integration or separation, in this phase we see that, while studies favor the importance of considering competition and cooperation simultaneously, they inspect “how the division between the cooperative and the competitive part of the relationship can be made and to further scrutinize the advantages of coopetition” (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000: 412).

As Figure 6.1 shows, the pendulum is clearly located on the exogenous side, meaning that, despite the fact that interactions among rival firms are explored focusing on resources and capabilities endowment and deployment, authors particularly stress industry structure conditions that in turn push firms to cooperate with rivals (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000).

The childhood phase: Grasping the balance between competition and cooperation (2001–2005)

During the second evolutionary phase of coopetition research, here labeled the “childhood stage,” we see an increased number of studies on coopetition. Scholars recognize the relevance of identifying novel, intriguing solutions to simultaneously combine and cope with competition and cooperation. For instance, Quintana-García and Benavides-Velasco (2004) introduce a bouquet of alternative moves that firms may develop (i.e., unilateral cooperation, mutual cooperation, unilateral defection, and mutual defection), that might originate from blurring competition and cooperation.

Interestingly, in this phase most coopetition studies share the centrality of firms and how they should draw on their internal resources and capabilities to balance competition and cooperation, thereby achieving a coopetitive advantage over their rivals. In coopetitive relationships, “while competing with each other, business players also cooperate among themselves to acquire new knowledge from each other” (Tsai, 2002: 180). Therefore, in this phase the emphasis is on how firms organize themselves to balance the critical duality between cooperation—that informs the value creating process—and competition—that informs the value appropriation process (Luo, 2005). For instance, M’Chirgui (2005) underscores that players in the smart card industry need to cooperate with each other to face the technological and market uncertainty stemming from the industry. However, the focus rests on organizing firms’ internal resources and capabilities, developing R&D activities to anticipate rival-partners moves, and promoting the technological standard. In this perspective, coopetition is “a powerful means of identifying new market opportunities and developing business conduct” (M’Chirgui, 2005: 933).

From a theoretical point of view, the resource-based view alters the prevalent perspective through which authors choose to investigate coopetition. From such a perspective, rival firms can decide to collaborate with each other if there is room for combining and recombining their similar and/or complementary resources and capabilities to shape rare, inimitable, and valuable synergies. Studies appear focused on exploring how competition and cooperation may impact knowledge sharing (Levy et al., 2003; Quintana-García & Benavides-Velasco, 2004; Tsai, 2002). Given the emphasis on the resources needed to compete, authors explore coopetition in different kinds of firms, such as firms operating in high-tech industries (Carayannis & Alexander, 2001; M’Chirgui, 2005), firms of different sizes (Levy et al., 2003; Lin & Zhang, 2005), and firms operating in various geographies or having geographic diversification (Luo, 2005).

From the methodological point of view, the bulk of studies continue to present inductive case-based studies focusing on one central actor or on only few firms. At the same time, in this phase we start seeing a small amount of pieces adopting large-sample empirical methods that would allow the achievement of more generalizable results. Interestingly, considering the youth of the coopetition research area, in-depth case studies of single firms or industries are clearly favored in this phase. This condition occurs since case studies provide the opportunity to gather real-time data and conduct explorative investigation.

From the viewpoint of competition/cooperation integration or separation, we see that studies persist in approaching coopetition “as simultaneous, inclusive interdependence comprised of cooperation and competition as two interrelated but separate axes” (Luo, 2005: 73). In more detail, the subunits of the firm face “diverse issues and play diverse roles, giving rise to cooperation on some issues, projects, functions, or knowledge development and competition on other issues, projects, functions, or markets” (Luo, 2005: 73).

As Figure 6.1 shows, the pendulum of coopetition studies swings from the exogenous side further to the other extreme, the endogenous side. Authors call attention to firms’ resources, capabilities, and organizational structures supporting coopetition and allowing firms to perform better than rivals. Hence, the orchestration of resources firms possess represents the crucial asset for adopting a coopetitive strategy.

The adolescence phase: Benefits and pitfalls of coopetitive strategies (2006–2010)

The phase of coopetition research spanning from 2006 to 2010 represents the “adolescence” of coopetition studies. In this phase, we observe a significant increase in the number of coopetitive studies published in journals as well as a few books dedicated to the key issue. Among them, we acknowledge the presence of chapter collections published specifically in two edited books (Dagnino, 2009; Yami et al., 2010).

In this third phase, we recognize the emergence of studies exploring coopetition among firms at various levels of analysis,1 such as at inter-firm level (Bakshi & Kleindorfer, 2009; Venkatesh et al., 2006) and network level (Gnyawali et al., 2006; Peng & Bourne, 2009). These studies share emphasis on the exogenous side of coopetition, by stressing the impact of the international contexts (Luo, 2007; Luo & Rui, 2009) and, more generally, of industry factors (Gnyawali & Park, 2009; Watanabe et al., 2009). This condition applies to various environmental settings, such as the supply chain (Wu et al., 2010), knowledge-intensive industries (Cassiman et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2006; Watanabe et al., 2009), the healthcare industry (Peng & Bourne, 2009), and interactions with external agents, such as institutions and governments (Dagnino & Mariani, 2010), affecting firms’ abilities to achieve easier and/or earlier access to information and knowledge.

From a theoretical point of view, we notice that the majority of studies ground the firm’s choice to collaborate with rivals on higher/lower transaction costs or on the threat of opportunistic behavior. Interestingly, some authors argue that the benefits stemming from cooperation with rivals depend on the higher costs related to the threat of a rival’s opportunistic behavior that may be exerted during the coopetitive interaction to appropriate the value created (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009). They draw on the resource-based theory to emphasize the relevance in high-tech industries of collaborating with rivals to generate knowledge and to become more innovative (Ritala & Urmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009). Finally, a few papers draw on game theory to explain the competitive factors emerging during interaction among rival firms (Wu et al., 2010).

From a methodological point of view, while some scholars (Cassiman at al., 2009; Dagnino & Mariani, 2010; Watanabe et al., 2009) carry on to adopt qualitative detailed case-study methodology to grasp how to manage the coopetition emerging among R&D projects to extract profit from innovation activities (Cassiman at al., 2009), or to develop new technologies (Watanabe et al., 2009), others use other methods, such as network analysis, to seize the impact of coopetition on rivals’ competitive behavior (Gnyawali et al., 2006; Peng & Bourne, 2009).

From the viewpoint of competition/cooperation integration or separation, in this phase we observe that, to appreciate the essence of coopetition, studies generally acknowledge the relevance of digging deeper into the mechanisms underlying the integration of competition and cooperation (Dagnino, 2009). Specifically, by “making either the cooperation element or the competition element hidden” (Gnyawali et al., 2008: 395), Gnyawali et al. (2008) identify three guidelines to deal with coopetition: (a) spatial separation; (b) temporal separation, and (c) integration of competition and cooperation.

As Figure 6.1 shows, the pendulum of coopetition studies swings in this phase from the endogenous side to the other extreme, or the exogenous side. Authors call attention to the benefits and risks underlying the adoption of a coopetitive strategy, as well as on the impact of external factors on the firm’s decision to collaborate with rivals and, therefore, to develop a coopetition strategy. Additionally, eclectic approaches to coopetition and the wide portfolio of methodologies present in this phase confirms that, between 2006 and 2010, coopetition literature has eventually reached its adolescence.

The younghood phase: Managing coopetitive tensions (2011–2016)

The period of research spanning from 2011 to 2016 represents, in our understanding, the “younghood” phase of coopetition studies. This phase is characterized by the continuous and remarkable growth of coopetition literature. The amount of papers published and special issues of academic journals produced (i.e., two issues of Industrial Marketing Management in 2014 and 2016, one issue of the International Journal of Management and Organization in 2014, one issue of the International Journal of Business Environment in 2014, and one issue of the International Journal of Technology Management in 2016) confirm the increasing consensus that the coopetition research area is actually experiencing in the management realm (Minà & Dagnino, 2016), as well as the growing interest of the management community in developing a robust academic debate on the key aspects of coopetition so as to tackle the open issues and foster future research (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014).

Articles published in this phase explore the management of competition and cooperation intensity, and the balance between them for achieving increased firm innovation and performance. Specifically, authors call for consideration of the management of coopetitive tensions emerging at various levels of analysis (Fernandez et al., 2014; Séran et al., 2016). In this line of reasoning, Tidström (2014) detects the key drivers of coopetitive tensions and identifies the approaches firms should adopt to deal with them. Actually, different styles of action can employ different approaches to managing coopetitive tensions, thereby producing different outcomes that can be mutually positive, mutually negative, or mixed for the parties involved (Tidström, 2014). This condition emphasizes the relevance of managing the competition-cooperation paradox emerging in coopetition (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016; Czakon et al., 2014; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014).

In addition, the fourth phase of coopetition studies shares the emphasis on the regained centrality of firms and the importance of digging deeper into the mechanisms of managing coopetition for achieving coopetitive advantage. Remarkably, some authors call attention to the effect of coopetition strategy on innovation and performance (Bouncken et al., 2016; Estrada et al., 2016; Park et al., 2014; Ritala, 2012; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2013; Wilhem, 2011).

From a theoretical point of view, the majority of studies take a resource-based view or transaction-cost-of-economics stance. Analyzing the actors involved in coopetition, authors observe that increased cooperation might develop concerns about opportunistic behavior (Sainio et al., 2012). This stream of study implicitly summons up Hamel’s (1991) piece, according to which collaboration between competitors leads to the emergence of learning races. In this context, firms struggle against time to access and exploit their partner’s knowledge faster than their partner can do the same in such a way that they can forsake the coopetitive relationship when they have obtained what they wanted. Such concerns are primarily rooted in the potential threat that partners may always act in an opportunistic fashion.

From a methodological point of view, in this phase we observe a notable increase in the amount of papers adopting quantitative methods. While the previous phases of coopetition research have been methodologically dominated primarily by cases studies, in the younghood phase, scores of studies present quantitative data-driven and longitudinal analyses. For instance, Wu (2014) analyzes 1499 Chinese firms operating in several industries to detect an inverted U-shaped relationship between coopetition and product innovation performance. Furthermore, using a sample of 627 manufacturing firms, Estrada et al. (2016) unveil the role of internal knowledge-sharing mechanisms and formal knowledge protection mechanisms in the relation between coopetition and innovation. Similarly, Bouncken et al. (2016) develop a survey-based study of 372 vertical alliances in the medical device industry to investigate how firms can enhance their product innovation pace in coopetitive alliances. Overall, since the adoption of econometric-based empirical methods allows the academic community to deal with more generalizable results, this condition also applies to coopetition research. However, interestingly enough in this phase, conceptual pieces and theoretical frameworks are still being developed (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Gnyawali et al., 2016; Mariani, 2016).

From the viewpoint of competition/cooperation integration or separation, since authors have begun to accept that coopetition is inherently betrothed by tensions arising from the simultaneous interaction of cooperative and competitive actions (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014), they fine-tune their research to the paradox of managing coopetition and the required analytical and execution capabilities to do so (Gnyawali et al., 2016).

As Figure 6.1 clearly shows, the pendulum of coopetition studies swings out from the exogenous side to the other extreme, or to the endogenous side. While in the previous phase—labeled the adolescence of coopetition—scholars tended to examine why and to what extent firms involved in coopetitive relationships were committed to cooperation to achieve their shared objectives, for the first time in this phase authors emphasize that “coopetitive tension is fundamentally an individual level construct, which is experienced and felt by managers that are carrying out the contradictory tasks of coopetition” (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016: 12). Therefore, it appears crucial to explore the inner mechanisms that emerge when competition and cooperation occur simultaneously, as well as the ways through which firms should deal with them (Fernandez et al., 2014).

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have interpreted the evolution of coopetition literature through the metaphor of a swinging pendulum. The pendulum swings from the exogenous side, giving relevance to the characteristics of context and actors representing key antecedents and factors leading to cooperation with rivals and coopetition performance, to the endogenous side, focusing on how firms organize themselves and invest resources in dealing with coopetition. Specifically, we have seen that, from the birth phase of early development to the childhood phase, the pendulum swings from the exogenous side to the endogenous side of coopetition. Later on, during the adolescence phase, the pendulum swings back towards the exogenous side. Finally, in the younghood phase, the pendulum swings forward once more to the exogenous side of coopetition, in which the focus is on how to manage coopetitive tensions.

We believe that strategic management inquiry may benefit from an overview such as this one, integrating various insights from prior research. In fact, the comprehensive picture of the four-phased evolution of coopetition literature we have supplied in this chapter is to be seen as the backbone to shaping an intriguing introduction to the coopetition domain that may be of interest to a wide array of strategy scholars and students, who have developed or are developing awareness in coopetition and/or wish to join its exploration in the future.

Note

1Interestingly, some authors have also explored coopetition among groups and among functions and strategic business units (Cassiman et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2006).

References

Afuah, A. (2000). How much do your “co-opetitors’” capabilities matter in the face of technological change? Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 387–404.

Bakshi, N. & Kleindorfer, P. (2009). Co-opetition and investment for supply-chain resilience. Production and Operations Management, 18(6), 583–603.

Bengtsson, M., Eriksson, J., & Wincent, J. (2010). Co-opetition dynamics—an outline for further inquiry. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 20(2), 194–214.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition—Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2015). Tension in Co-opetition. In Spott H. E. (Ed.). Creating and delivering value in marketing. Cham: Springer, 38–42.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: toward a multilevel understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

Bouncken, R. B., Clauß, T., & Fredrich, V. (2016). Product innovation through coopetition in alliances: Singular or plural governance? Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 77–90.

Bouncken, R. B., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Bogers, M. (2015). Coopetition: a systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 577–601.

Bouncken, R. B. & Kraus, S. (2013). Innovation in knowledge-intensive industries: The double-edged sword of coopetition. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2060–2070.

Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday.

Carayannis, E. G. & Alexander, J. (2001). Virtual, wireless mannah: a co-opetitive analysis of the broadband satellite industry. Technovation, 21(12), 759–766.

Carayannis, E. G. & Alexander, J. (1999). Winning by co-opeting in strategic government-university-industry R&D partnerships: the power of complex, dynamic knowledge networks. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 24(2), 197–210.

Carayannis, E. G. & Roy, R. I. S. (2000). Davids vs Goliaths in the small satellite industry:: the role of technological innovation dynamics in firm competitiveness. Technovation, 20(6), 287–297.

Cassiman, B., Di Guardo, M. C., & Valentini, G. (2009). Organising R&D projects to profit from innovation: Insights from co-opetition. Long Range Planning, 42(2), 216–233.

Chin, K. S., Chan, B. L., & Lam, P. K. (2008). Identifying and prioritizing critical success factors for coopetition strategy. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 108(4), 437–454.

Czakon, W., Fernandez, A. S., & Minà, A. (2014). Editorial–From paradox to practice: the rise of coopetition strategies. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 1–10.

Dagnino, G. B. (2009). Introduction—coopetition strategy: a “path recognition” investigation approach. In Dagnino, G. B. & Rocco, E. (Eds), Coopetition strategy: theory, experiments and cases. New York: Routledge, 1–21.

Dagnino, G. B. (2016). Evolutionary lineage of the dominant paradigms in strategic management research. In Dagnino, G. B. & Cinici M. C. (Eds), Research Methods for Strategic Management. New York: Routledge, 15–48.

Dagnino, G. B. & Mariani, M. M. (2010). Coopetitive value creation in entrepreneurial contexts: The case of AlmaCube. In Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, B., & Le Roy, F. (Eds), Coopetition: winning strategies for the 21st century. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 101–123.

Dagnino, G. B. & Padula, G. (2002). Coopetition strategy: a new kind of interfirm dynamics for value creation. In Innovative Research in Management, European Academy of Management (EURAM), second annual conference, Stockholm, May (Vol. 9).

Dowling, M. J., Roering, W. D., Carlin, B. A., & Wisnieski, J. (1996). Multifaceted relationships under coopetition: Description and theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 5(2), 155–167.

Eriksson, P. E. (2008). Procurement effects on coopetition in client-contractor relationships. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 134(2), 103–111.

Estrada, I., Faems, D., & de Faria, P. (2016). Coopetition and product innovation performance: The role of internal knowledge sharing mechanisms and formal knowledge protection mechanisms. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 56–65.

Fernandez, A. S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gnyawali, D. R., He, J., & Madhavan, R. (2006). Impact of co-opetition on firm competitive behavior: An empirical examination. Journal of Management, 32(4), 507–530.

Gurnani, H., Erkoc, M., & Luo, Y. (2007). Impact of product pricing and timing of investment decisions on supply chain co-opetition. European Journal of Operational Research, 180(1), 228–248.

Gnyawali, D. R., He, J. & Madhavan, R. (2008). Co-opetition: Promises and challenges. 21st century management: A reference handbook, 386–398.

Gnyawali, D. R., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2016). The competition–cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 7–18.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B. J. R. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B. J. R. (2011). Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for competence and interpartner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S1), 83–103.

Hoskisson, R. E., Hitt, M. A., Wan, W. P., & Yiu, D. (1999). Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum. Journal of Management, 25(3), 417–456.

Kylänen, M. & Rusko, R. (2011). Unintentional coopetition in the service industries: The case of Pyhä-Luosto tourism destination in the Finnish Lapland. European Management Journal, 29(3), 193–205.

Langley, A. (2010) Temporal Bracketing. In Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (Eds). (2010). Encyclopedia of case study research: L-Z; index (Vol. 1). California: Sage.

Langley, A. & Truax, J. (1994). A process study of new technology adoption in smaller manufacturing firms. Journal of Management Studies, 31(5), 619–652.

Levy, M., Loebbecke, C., & Powell, P. (2003). SMEs, co-opetition and knowledge sharing: the role of information systems. European Journal of Information Systems, 12(1), 3–17.

Lin, C. Y. Y. & Zhang, J. (2005). Changing structures of SME Networks: Lessons from the publishing industry in Taiwan. Long Range Planning, 38(2), 145–162.

Li, Y., Liu, Y., & Liu, H. (2011). Co-opetition, distributor’s entrepreneurial orientation and manufacturer’s knowledge acquisition: Evidence from China. Journal of Operations Management, 29(1), 128–142.

Loebecke, C., Van Fenema, P. C., & Powell, P. (1999). Co-opetition and knowledge transfer. ACM SIGMIS Database, 30(2), 14–25.

Luo, Y. (2004). A coopetition perspective of MNC–host government relations. Journal of International Management, 10(4), 431–451.

Luo, Y. & Rui, H. (2009). An ambidexterity perspective toward multinational enterprises from emerging economies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(4), 49–70.

Luo, X., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pan, X. (2006). Cross-functional “coopetition”: The simultaneous role of cooperation and competition within firms. Journal of Marketing, 70(2), 67–80.

Luo, Y. (2005). Toward coopetition within a multinational enterprise: a perspective from foreign subsidiaries. Journal of World Business, 40(1), 71–90.

Luo, Y. (2007). A coopetition perspective of global competition. Journal of World Business, 42(2), 129–144.

M’Chirgui, Z. (2005). The economics of the smart card industry: towards coopetitive strategies. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 14(6), 455–477.

Mariani, M. M. (2007). Coopetition as an emergent strategy: Empirical evidence from an Italian consortium of opera houses. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 97–126.

Mariani, M. M. (2016). Coordination in inter-network co-opetitition: Evidence from the tourism sector. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 103–123.

Mention, A. L. (2011). Co-operation and co-opetition as open innovation practices in the service sector: Which influence on innovation novelty? Technovation, 31(1), 44–53.

Minà, A. & Dagnino, G. B. (2016). In search of coopetition consensus: shaping the collective identity of a relevant strategic management community. International Journal of Technology Management, 71(1–2), 123–154.

Morris, M. H., Koçak, A., & Özer, A. (2007). Coopetition as a small business strategy: Implications for performance. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 18(1), 35.

Nalebuff, B. J. & Brandenburger, A. M. (1997). Co-opetition: Competitive and cooperative business strategies for the digital economy. Strategy & Leadership, 25(6), 28–33.

Padula, G. & Dagnino, G. B. (2007). Untangling the rise of coopetition: the intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 32–52.

Park, B. J. R., Srivastava, M. K., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Walking the tight rope of coopetition: Impact of competition and cooperation intensities and balance on firm innovation performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 210–221.

Peng, T. J. A. & Bourne, M. (2009). The coexistence of competition and cooperation between networks: implications from two Taiwanese healthcare networks. British Journal of Management, 20(3), 377–400.

Quintana-García, C. & Benavides-Velasco, C. A. (2004). Cooperation, competition, and innovative capability: a panel data of European dedicated biotechnology firms. Technovation, 24(12), 927–938.

Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198.

Ritala, P. (2012). Coopetition strategy—when is it successful? Empirical evidence on innovation and market performance. British Journal of Management, 23(3), 307–324.

Ritala, P., Golnam, A., & Wegmann, A. (2014). Coopetition-based business models: The case of Amazon.com. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 236–249.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2009). What’s in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation, 29(12), 819–828.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2013). Incremental and radical innovation in coopetition—The role of absorptive capacity and appropriability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(1), 154–169.

Rusko, R. (2011). Exploring the concept of coopetition: A typology for the strategic moves of the Finnish forest industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 311–320.

Sainio, L. M., Ritala, P., & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2012). Constituents of radical innovation—exploring the role of strategic orientations and market uncertainty. Technovation, 32(11), 591–599.

Séran, T., Pellegrin-Boucher, E., & Gurau, C. (2016). The management of coopetitive tensions within multi-unit organizations. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 31–41.

Smith, K. G., Carroll, S. J., & Ashford, S. J. (1995). Intra-and interorganizational cooperation: Toward a research agenda. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 7–23.

Tidström, A. (2014). Managing tensions in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 261–271.

Tsai, W. (2002). Social structure of “coopetition” within a multiunit organization: Coordination, competition, and intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organization Science, 13(2), 179–190.

Venkatesh, R., Chintagunta, P., & Mahajan, V. (2006). Research note—sole entrant, co-optor, or component supplier: Optimal end-product strategies for manufacturers of proprietary component brands. Management Science, 52(4), 613–622.

Walley, K. (2007). Coopetition: an introduction to the subject and an agenda for research. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 11–31.

Wang, Y. & Krakover, S. (2008). Destination marketing: competition, cooperation or coopetition? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(2), 126–141.

Watanabe, C., Lei, S., & Ouchi, N. (2009). Fusing indigenous technology development and market learning for greater functionality development—an empirical analysis of the growth trajectory of Canon printers. Technovation, 29(4), 265–283.

Wilhelm, M. M. (2011). Managing coopetition through horizontal supply chain relations: Linking dyadic and network levels of analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7), 663–676.

Wu, J. (2014). Cooperation with competitors and product innovation: Moderating effects of technological capability and alliances with universities. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 199–209.

Wu, Z., Choi, T. Y., & Rungtusanatham, M. J. (2010). Supplier–supplier relationships in buyer–supplier–supplier triads: Implications for supplier performance. Journal of Operations Management, 28(2), 115–123.

Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, B., & Le Roy, F. (Eds) (2010). Coopetition: winning strategies for the 21st century. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Zineldin, M. (2004). Co-opetition: the organisation of the future. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22(7), 780–790.