Introduction

Coopetition is understood as a relationship covering simultaneous cooperation and competition (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Gnyawali & Park, 2011; Luo et al., 2006; Luo, 2007). From that perspective, any sequential, alternating appearance of cooperation and competition should be seen as a coopetitive relationship (Czakon et al., 2014). The newest coopetition literature identifies five current research areas (Dorn et al., 2016): (1) the nature of the relationship; (2) governance and management; (3) the output of the relationship; (4) actors’ characteristics; and (5) environmental characteristics. This chapter refers to the fourth area, namely coopetitors’ characteristics and their cultural profile in particular. Exploration of this area is reasoned as our knowledge about contextual factors is limited, hence the development of full conceptualization of coopetition in different managerial settings is hampered (Bouncken et al., 2015). Furthermore, given the results of several literature reviews on coopetition, (Bengtsson et al., 2010; Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016; Czakon et al., 2014; Dorn et al., 2016; Gast et al., 2015), even if organizational culture was the subject of explorative research, it remains fragmentarily recognized in the field of coopetition. This is surprising, as cultural aspects were claimed to be insufficiently explored in the context of coopetition more than a decade ago (Rijamampianina & Carmichael, 2005).

Following Luo (2007), the partnering of competitor’s needs: resource complementarity, goal compatibility, and respective cooperative culture, which ought to be based on shared values, philosophies, and assumptions. Similarly, Rijamampianina and Carmichael (2005) showed coopetitive relationships to be a function of cultural compatibility and strategic complementarity. In their proposition, it is possible to establish coopetition based on cultural compatibility, including centrality and visibility of cultural elements. Moreover, among the types of coopetitive relationships, there is a culturally based coopetition, which is characteristic for business rivals displaying similar strategic imperatives and compatible cultures (Rijamampianina & Carmichael, 2005). Finally, in research on collaborative networks, run from an organizational culture perspective, Srivastava and Banaji (2011) introduced the term of collaborative organizational culture, which emphasizes cross-boundary collaboration based on pro-cooperative beliefs, assumptions, and values.

The nuts and bolts of organizational culture

Organizational culture is understood as a set of beliefs, assumptions, artefacts, meanings, and perceptions (Denison, 1996; Hatch, 1993; Schein, 2010) shared by members of an organization (Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2010). As claimed by Denison (1996), organizational culture refers to the deep structure of an organization that is invisible and deeply rooted in values. However, when the above components of organizational culture are employed and take visible manifestations (e.g., behaviors, practices), they are considered to be more flexible, more psychological organizational features, namely the organizational climate.

In the current body of knowledge it is claimed that the exploration of organizational culture needs consideration of a wide range of aspects (Gregory et al., 2009; Maximini, 2015; Strese et al., 2016), for example, level of formalization, level of centralization, level of tolerance/avoidance of risks, degree of orientation on personal/impersonal relationships and communication, focus either on external or on internal environment, level of flexibility, level of control, or structure and strategic focus. All in all, there is no agreement about the structure and operationalization of this complex and latent construct; nonetheless, there are two general approaches to define the models of organizational culture. First, the models can be identified based on a set of specific features displayed by a particular company (see, for instance, Jarratt & O’Neill, 2002). Second, the model of culture adopted by the company may be identified using two differentiating and dichotomous continua; see Table 10.1.

Table 10.1Brief summary of different organizational culture models

| Author(s) | Year | Differentiating Continua | Models of Organizational Culture |

| Harrison | 1972 (1897) | High/low formalization

High/low centralization |

Role orientation

Task/achievement orientation; Person/support orientation power orientation |

| Schneider | 1999 | Actuality/possibility

Personal/impersonal |

Collaboration;

control; competence; cultivation |

| Deal and Kennedy | 2000 | Fast/slow feedback

High/low risk |

Work hard/play hard;

tough-guy/macho/s’ras; bet-your-company process |

| Iivari and Huisman | 2007 | Change/stability

Internal focus/external focus |

Group;

developmental; rational; hierarchical; balanced* |

| Cameron and Quinn | 2011 | Flexibility and discretion/ stability and control

Internal focus and integration/ external focus and differentiation |

clan;

adhocracy; market hierarchy; balanced* |

* As indicated by Gregory, Harris, Armenakis, and Shook (2009), companies may adopt a balanced model of organizational culture if all CVF culture domains are strongly held by the company.

(Source: based on Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Maximini, 2015; Strese et al., 2016.)

Models of organizational culture suitable for coopetitors

Prior literature shows that there are differences in organizational cultures adopted by coopetitors (Strese et al., 2016). Likewise, their cultural models are different from the models of non-coopetitors operating in the same industry settings (Klimas, 2016). However, it still remains unclear whether there is one perfect solution, namely the most suitable (characteristic) model of organizational culture for coopetitors. However, if we take a closer look at the different models of organizational cultures identified by different scholars (Table 10.1), it would be possible to outline the models being potentially the most suitable for organizations interested in coopetition.

First, following differentiating continua proposed by Harrison in 1972 (Maximini, 2015), the most appropriate model of organizational culture for coopetitors seems to be the “task/achievement orientation” characteristic for organizations with low centralization and high formalization. Given the results of research carried out on German companies, the level of centralization negatively influences, while the level of formalization positively influences, coopetition performance (Strese et al., 2016). Additionally, explorative research on organizational culture models of coopetitors in the Polish aviation industry shows high levels of formalization expressed by an extensive system of norms, rules, and procedures as characteristic for coopetitors (Klimas, 2016).

Second, given actuality/possibility and personal/impersonal dichotomies considered by Schneider, it is possible to identify the general (independent from national culture or industry settings) models of organizational cultures (as cited by Maximini, 2015). These dichotomies take into account the commitment and fulfilment of staff in utilizing opportunities arising from the company’s environment. Thus, the “competence” model based on impersonal relationships/communication and focused on the exploitation of future possibilities seems to be the most suitable for organizations interested in the adoption of coopetition. It seems to be the most rational, as coopetition is usually utilized by high-tech companies (Czakon et al., 2014) interested in radical innovation implemented on a global scale (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2013) and operating in industries driven by innovation and technology pressures (Gnyawali & Park, 2009; 2011). Furthermore, as coopetition is tension-based (Fernandez et al., 2014) and contains the risk of opportunistic behaviors (Bengtsson et al., 2010), coopetitors do not trust each other (an atmosphere of distrust is typical; Gnyawali & Park, 2009) and thus use developed protection mechanisms (Klimas, 2016), which also favors the suitability of the “competence” model of organizational culture.1

Third, taking into account the two continua (labeled as marketplace factors) adopted by Deal and Kennedy in their organizational culture framework (Maximini, 2015), the “bet-your-company” cultural model (high risk and slow feedback) seems to be the most appropriate for coopetitors. Companies that adopt this model take a long view on values, development, and investment, but the speed of their reactions to environment changes is low, while the efforts that should be taken to get feedback about the efficiency of those actions are high. Given that coopetition is adopted due to high levels of uncertainty (Gnyawali & Park, 2011; Ritala, 2012), as well as the need for the development and introduction of radical innovation (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2013), this culture seems to be the most appropriate.

Fourth, among many different models of organizational culture, the most popular approach still remains the competing value framework (CVF) (Eckenhofer & Ershova, 2011; Gregory et al., 2009; Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2011). This model provides models of cultures that match the most important management theories about organizational success, organizational quality, organizational roles, leadership, and management skills (Cameron & Quinn, 2011). As shown in Table 10.1, CVF is based on two independent continua (Gregory et al., 2009): (1) flexibility and discretion/stability and control (evaluating the structural dimension of the organization and its culture); and (2) internal focus and integration/external focus and differentiation (assessing the strategic focus of the organization). Simultaneous consideration of these two continua (dimensions) allows distinction between four models of organizational culture, i.e., clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market.

Prior literature shows two models as characteristic for cooperating companies. Namely, “clan culture,” which has been identified based on research on Austrian companies (Eckenhofer & Ershova, 2011), and the “adhocracy model” (also labeled the “developmental model” in terms of the typology provided by Ivari & Huisman in 2007; see Table 10.1), which has been shown as the most suitable for German organizations focused either on short-term and periodic interaction or longitudinal cooperation with both non-coopetitors and the greatest business rivals (Strese et al., 2016).

Summing up, there are different models of organizational culture that can be deliberately or inadvertently adopted by organizations interested in successful coopetition adoption. Nonetheless, in the context of coopetition, organizational culture still remains under-researched (Dorn et al., 2016; Klimas, 2016; Strese et al., 2016).

Research on cultural models of coopetitors in a nutshell

Comparison of prior studies on models of organizational cultures of coopetitors suggests that the model of organizational culture most suitable for coopetitors may be conditioned by external factors like industry or country. The results of two prior studies run in this area show that German manufacturers that maintain coopetitive relationships usually adopt the adhocracy model of organizational culture (flexibility and external focus; Strese et al., 2016), whereas Polish aviation coopetitors usually adopt the hierarchy model (stability and internal focus; Klimas, 2016). It is hard to confront the identified suitability of particular models of organizational cultures as both external factors—country/industry type—might be responsible for the results obtained. Therefore, to limit the contextual influence to one external factor we set the following research question: are there any models of organizational cultures that are shared by coopetitors functioning in the same country but in different industries?

The research aimed at answering the above question was explorative in nature and was focused on the development of our fragmentary knowledge about the existence of one specific model of organizational culture adopted by coopetitors.2 Given that “there is no ideal instrument for cultural exploration” (Jung et al., 2009: 1087), in this study the competing values framework was adopted as the most popular one. Each model of organizational culture was assessed using two differentiating continua (Gregory et al., 2009): structural (from flexible to stable) and strategic (from external to internal focus). The measurement tool and the approach to data analysis were adopted from prior studies carried out on cultural facets of Polish aviation coopetitors.3

The comparative explorations were made in parallel for coopetitors operating in two different industry sectors: aviation and the video game industry (VGI). First and foremost, purposeful selection of these industries was reasoned as both of them are innovation-based, knowledge-intensive, classified as high-tech, and aimed at the production of complex and global products (Klimas, 2016; O’Donnell, 2012), while those industry characteristics are shown as the most favorable for coopetition occurrence (Gast et al., 2015; Gnyawali & Park, 2009; Luo, 2007; Ritala, 2012). In order to limit the influence of national context on models adopted by coopetitors, the scope of research was limited to Poland—see Table 10.2.

Table 10.2Data-gathering in aviation and the video game industry

| Industry | Aviation Industry in Poland | Video Game Industry in Poland |

Time scope |

2012–2013 |

2017 |

Industry size |

Approximately 140—Report on Innovativeness of the Aviation Sector in Poland in 2010 ordered by the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development |

Approximately 150 – The stat of Polish Video Games Sector. Report 2015 ordered by The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. |

Cooperation |

Joint participation in national and international research projects—database provided by the Polish Agency of Information and Foreign Investments, Polish Agency for Enterprise Development, and Community Research and Development Information Service |

Joint participation in national and international research projects—database provided by the National Centre for Research and Development, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, and Community Research and Development Information Service |

Competition |

Direct competition in sales—manufacturing the same products and (or) delivering the same services according to information presented by databases of aviation networks |

Direct competition in sales—development of free-to-play games in freemium model sold through App Store/Google Play Store |

Identified coopetitors—targeted sample |

35; invitation sent to all |

74; invitation sent to all |

Research sample |

27 |

19 |

Specific models of organizational cultures of coopetitors in business practice

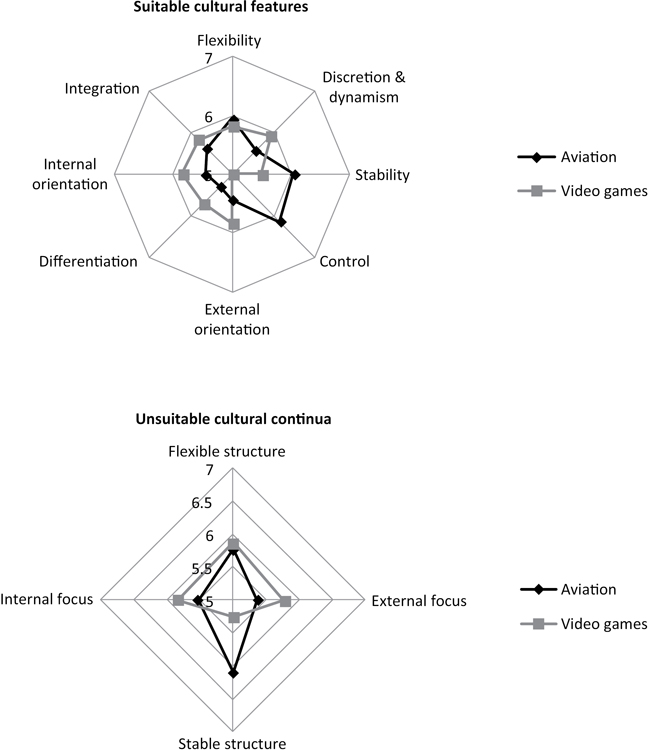

Given the average levels of particular cultural features (proxy for intensity of cultural characteristics), the differences among coopetitors from aviation and VGI identified using the share of coopetitors are confirmed—see Figure 10.1.

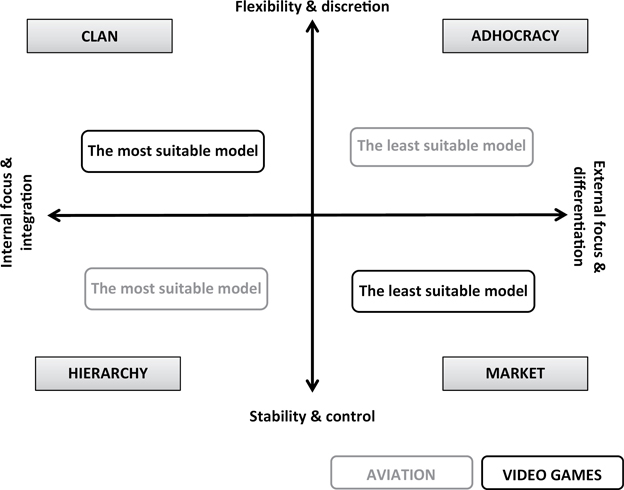

Coopetitors in VGI seem to be less stable and control-driven while they are more focused on dynamism and discretion than cooperating business rivals in aviation. Similarly, given the dichotomous cultural continua used in CVF the structural continuum seems to differentiate the industries more than the strategic approach. The difference in the intensity of cultural extrema considered on the structural continuum results from differences in the level of stability indicated by coopetitors in VGI and aviation while the level of flexibility is quite similar. Note, however, that flexible structure covers flexibility and dynamism. In the case of aviation the level of flexible structure results from the importance of flexibility but not from dynamism (Klimas, 2016). Last but not least, considering particular cultural features it was possible to identify the most- and the least-suitable models of organizational culture for coopetitors. As shown in Figure 10.2, the results are different in both the most- and the least-suitable cultural models for coopetitors from aviation and VGI.

As identified earlier (Klimas, 2016), the most-suitable model of organizational culture for coopetitors from the aviation industry is hierarchy, while the least-suitable model is adhocracy. Surprisingly, the cultural model that best matches the features of video game coopetitors is clan culture, whereas the market model is the least-suitable organizational culture. However, it’s worth noting that in both industries the most-suitable organizational culture models assume internal focus while the least-suitable models assume concentration on the environment.

Summing up, the results of this explorative research suggest that there is no specific model of organizational culture best-suited to all coopetitors regardless of the type of industry. Furthermore, the results may suggest that coopetitors—regardless of the industry—adopt organizational cultures characterized by internal focus.

Conclusions and implications for both theory and further research

A bibliometric analysis of prior works shows that there are some coopetition-specific contexts influencing coopetitive relationships, while industry is one of the most often applied (Gast et al., 2015). Indeed, coopetition is expressed as an extremely industry-related phenomenon (Bouncken et al., 2015; Czakon et al., 2014; Dorn et al., 2016), while prior empirical efforts aimed at recognition of the cultural specificity of coopetitors was restricted to one industry (compare, e.g., Klimas, 2016; Strese et al., 2016), thus in order to improve the state of our knowledge it was reasoned to explore more deeply the specificity of cultural models of coopetitors without restricting the scope of research to one industry. Furthermore, to limit the risk of potential differences caused by national differences, including differences in national cultures, the research should be run in one country. Therefore, the exploration of the most suitable models of organizational culture for coopetitors focused on coopetitors operating in one country (Poland) but in two different industries: aviation and video games.

As indicated by Deal and Kennedy, the type of organizational culture model appropriate for any company is conditioned by external factors, including the level of competition, globalization, technological advancement, innovativeness, customer pressure, etc. (Maximini, 2015). This means that industry settings are more important than endogenous decisions about the nature of organizational culture adopted. Indeed, Naranjo-Valencia et al. (2010, 2011) pointed out that outcome-based environments privilege a market culture, creative surroundings are seen as appropriate for an adhocracy culture, the hierarchy model is the best solution in cases of a strict and formalized organizational culture, while in a much more loose, informal, and sociable context it is better to adopt clan culture. In the context of coopetition, a brief review of different typologies (see Table 10.1) of organizational culture models shows different models of culture suitable for companies interested in cooperation with business rivals. Moreover, the results of empirical investigation show that the most-suitable as well as the least-suitable models of organizational culture of coopetitors are different between considered industries.

First, the most suitable model of culture (following classification based on the CVF approach, developed by Cameron and Quinn in 2011) for coopetitors operating in the aviation there is hierarchy, while for those operating in VGI it is clan culture. In prior research, the hierarchy model has been indicated as a model with the lowest support for both the establishment and maintenance of inter-organizational cooperation (Eckenhofer & Ershova, 2011: 39). Important research on innovation and imitation strategies adopted by Spanish companies has shown that hierarchy promotes an imitation strategy inside clusters, while it also has a negative effect on innovation strategy (Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2011). Such findings seem to be contradictory to those obtained in this research. However, in the light of other results, the collaborative organizational culture can be based on formalized decision processes (Srivastava & Banaji, 2011); especially in cases of mature industries and manufacturing firms based on strategic resources, control cultures (actuality and impersonal dimensions) characterized by a great focus on hierarchy, predictability, and a longitudinal approach are the most successful and reasoned (Maximini, 2015).

Second, the most suitable model of culture for coopetitors operating in VGI is clan culture. Such result remain in line with prior studies showing this model to have been adopted by companies engaging in inter-organizational relationships, as a model that “supports the creation of solid networks the most” (Eckenhofer & Ershova, 2011: 38).

Third, the adhocracy model has been identified as the least suitable for aviation coopetitors, whereas market culture has been shown as the least suitable for cooperating business rivals in VGI. Given the lack of prior research focusing on the least-suitable models of organizational cultures for companies with a coopetitive approach, it was impossible to confront the results with any other empirical findings. However, it is worth noting that the explorative results suggest the differences in adequacy of adopted models of organizational culture to be conditioned by the type of industry. It is claimed that these differences may be explained by the following industry conditions: VGI is very fast-moving, especially due to the rapid expansion of mobile and “free-to-play” (F2P) games; aviation is conditioned by extensive safety regulations at global, European, and national level; the life cycles of products provided by those industries significantly differ—aircrafts are produced for four to five decades while games stay on the market for no longer than five to seven years (O’Donnell, 2012). Furthermore, as suggested by Klimas (2016), coopetitors in aviation pay attention to responsiveness and adaptiveness to external changes (flexibility), whereas they do not display a proactive and enterprising approach that results in the triggering of those changes (dynamism). This is the case as aviation is subordinated to safety and international regulations. Therefore, the majority of changes are induced by the institutional and political environment and companies must adapt to them as soon as possible. In other words, before change can be triggered by particular companies in a business practice, external approval must be assured by (usually global) policy makers. All in all, even though the most- and least-suitable models for coopetitors seem to be different, our findings confirm the preliminary assumptions about sectoral conditioning of cultural settings in the context of coopetition.

However, it should be noted that in both considered industries coopetitors seem to be more focused on internal issues and integration than on differentiation and external relationships, and the possibility of accessing resources and capabilities. This remains in contrast to findings on cross-functional coopetition showing adhocracy (developmental) culture as the most oriented on external cooperation, including cooperation with competitors (Strese et al., 2016). Simultaneously, such results may add to prior findings that show that the fear of a “lose-lose” situation (i.e., negative results of non-cooperating organizations) more often drives cooperation with business rivals than awareness and willingness of taking benefits from such cooperation (Liu, 2013: 91). Coopetitors may operate under enormous innovation, technological, and customer pressure leading them to cooperation with business rivals, even the closest ones. Hence, their awareness of coopetition-related risks (e.g., the asymmetry of information flows—Chai & Yang, 2011; a wide range of opportunistic behaviors—Bouncken & Kraus, 2013; value appropriation—Ritala & Tidström, 2014) limits their external focus and drives the development of extensive protection mechanisms. To conclude, it is argued there is no single most-suitable model of organizational culture for coopetitors, while the most appropriate cultural profile seems to depend on industrial settings.

This chapter confirms that coopetition is influenced not only by organizational-level, but also by environment- and industry-level factors (Gnyawali & Park, 2009). However, the focus here is on one organizational-level factor, namely organizational culture, considered in two different industry settings—hence, in the same national context. This national context, as well as the realization of research in only two industries, can be seen as a limitation.

However, this research was aimed at exploration, not at generalization. Thus, in further studies it would be valuable to consider the role of national cultures as they may be significant for coopetition strategy adoption, as they have not been investigated in a coopetition context so far. In fact, national context influences the models of organizational culture adopted, as national cultures do matter to organizations, while countries do differ in terms of cultural settings (Hofstede, 1981; Xiao & Tsui, 2007). Thus, it is suggested to run replication research on VGI or aviation (Klimas, 2016) outside of Poland, or on manufacturing companies outside of Germany (Strese et al., 2016) in order to compare the results. It would be interesting to run international or even global research on cultures adopted by coopetitors in industries characteristic for coopetition strategy adoption—those classified as high-tech, knowledge-intensive, or hyper-dynamic. Last but not least, to complete the cultural profile of coopetitors it would be good to run further research applying other differentiating continua (see Table 10.1) than those used in CVF.

Acknowledgment

The preparation of this paper was financially supported by the National Science Centre under the project titled: Co-creative relationships and innovativeness – the perspective of the video game industry (UMO-2013/11/D/HS4/04045).

Notes

1Even though Schneider distinguished the “cooperation” model of organizational culture, which allows “fully utilizing one another as resources” (Schneider, 1999: 45; quoted by Maximini, 2015: 15), we consider it unsuitable for coopetitors as they still stay enemies (not friends) linked by both cooperative and competitive relationships at the same time.

2The findings presented in this chapter are one of the results of two broader, separately run studies focused on organizational proximity in the aviation industry and co-creative relationships exploited by game developers. The same national scope and focus on organizational culture were the only joint aspects in those studies.

3A detailed description of the research framework (including measurement method, survey questionnaire, methodology of data analysis) can be found in Klimas (2016).

References

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business Networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: Toward a multilevel understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

Bengtsson, M., Eriksson, J., & Wincent, J. (2010). Co-opetition dynamics–an outline for further inquiry. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 20(2), 194–214.

Bouncken, R. B., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Bogers, M. (2015). Coopetition: a systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 577–601.

Bouncken, R. B. & Kraus, S. (2013). Innovation in knowledge-intensive industries: the double-edged sword of coopetition. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2060–2070.

Cameron, K. S. & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Chai, Y. & Yang, F. (2011). Risk control of coopetition relationship: An exploratory case study on social networks "Guanxi" in a Chinese logistics services cluster. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 6(3): 29–39.

Czakon, W., Mucha-Kuś, K., & Rogalski, M. (2014). Coopetition research landscape-a systematic literature review 1997–2010. Journal of Economics & Management, 17, 121.

Deal, T. & Kennedy, A. (2000). Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life (2000 Edition). New York: Basic Books.

Denison, D. R. (1996). What is the difference between organizational culture and organizational climate? A native’s point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 619–654.

Dorn, S., Schweiger, B., & Albers, S. (2016). Levels, phases and themes of coopetition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 34(5), 484–500.

Eckenhofer, E. & Ershova, M. (2011). Organizational culture as the driver of dense intra-organizational networks. Journal of Competitiveness, 3(2), 28–42.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gast, J., Filser, M., Gundolf, K., & Kraus, S. (2015). Coopetition research: towards a better understanding of past trends and future directions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 24(4), 492–521.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B. J. R. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B. J. R. (2011). Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663.

Gregory, B. T., Harris, S. G., Armenakis, A. A., & Shook, C. L. (2009). Organizational culture and effectiveness: A study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), 673–679.

Hatch, M. J. (1993). The dynamics of organizational culture. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 657–693.

Hofstede, G. (1981). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management and Organizations, 10(4): 15–41.

Iivari, J. & Huisman, M. (2007). The relationship between organizational culture and the deployment of systems development methodologies. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 35–58.

Jarratt, D. & O’Neill, G. (2002). The effect of organisational culture on business-to-business relationship management practice and performance. Australasian Marketing Journal, 10(3), 21–40.

Jung, T., Scott, T., Davies, H. T., Bower, P., Whalley, D., McNally, R., & Mannion, R. (2009). Instruments for exploring organizational culture: A review of the literature. Public Administration Review, 69(6), 1087–1096.

Klimas, P. (2016). Organizational culture and coopetition: An exploratory study of the features, models and role in the Polish aviation industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 91–102.

Liu, R. (2013). Cooperation, competition and coopetition in innovation communities. Prometheus, 31(2), 91–105.

Luo, X., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pan, X. (2006). Cross-functional “coopetition”: The simultaneous role of cooperation and competition within firms. Journal of Marketing, 70(2), 67–80.

Luo, Y. (2007). A coopetition perspective of global competition. Journal of World Business, 42(2), 129–144.

Maximini, D. (2015). The Scrum Culture. Introducing Agile Methods in Organizations. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Naranjo-Valencia, J. C., Sanz Valle, R., & Jiménez Jiménez, D. (2010). Organizational culture as determinant of product innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 13(4), 466–480.

Naranjo-Valencia, J. C., Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2011). Innovation or imitation? The role of organizational culture. Management Decision, 49(1), 55–72.

O’Donnell, C. (2012). This is not a software industry. In P. Zackariasson & T. L. Wilson (Eds), The Video Game Industry Formation, Present State, and Future (pp. 99–115). New York: Routledge.

Rijamampianina, R. & Carmichael, T. (2005). A framework for effective cross-cultural co-opetition between organisations. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 4, 92–103.

Ritala, P. (2012). Coopetition strategy: When is it successful? Empirical evidence on innovation and market performance. British Journal of Management, 23(3), 307–324.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2013). Incremental and radical innovation in coopetition—the role of absorptive capacity and appropriability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(1), 154–169.

Ritala, P. & Tidström, A. (2014). Untangling the value-creation and value-appropriation elements of coopetition strategy: A longitudinal analysis on the firm and relational levels. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(4), 498–515.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational Culture and Leadership (4th edition). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Srivastava, S. B. & Banaji, M. R. (2011). Culture, cognition, and collaborative networks in organizations. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 207–233.

Strese, S., Meuer, M. W., Flatten, T. C., & Brettel, M. (2016). Organizational antecedents of cross-functional coopetition: The impact of leadership and organizational structure on cross-functional coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 42–55.

Xiao, Z. & Tsui, A. S. (2007). When brokers may not work: The cultural contingency of social capital in Chinese high-tech firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52, 1–31.