Multidimensional sequence analysis

Alain Jeunemaître, Hervé Dumez, and Benjamin Lehiany

Introduction

Coopetition is an odd construct that links together two contrasting notions—competition and cooperation. The first calls to mind an individual struggle for particular gains. The second supports the idea of collective action to reach specific objectives. Coopetition is also ambiguous with respect to time: it refers both to simultaneity (competition and cooperation occurring at the same time) and to sequentiality (competitive processes succeeding cooperative processes). As such, coopetition may be said to be a multifaceted concept that can lead to multiple visual representations. The purpose of the present paper is to study this concept through these visualizations. As noted by Tufte (1990: 12), “The world is complex, dynamic, multidimensional; the paper is static, flat. How are we to represent the rich visual world of experience and measurement on mere flatland?”

It would be illusory to refer to all the possible ways of representing coopetition. There are many ways by which an account of a concept can be given through flatland visuals. Design tools are available, for example, to visualize dynamic and multidimensional data (see, for instance, Basole, 2014). In particular, they have been applied to topics related to social media coopetition, to visualize how firms cooperate and compete to attract public attention in media coverage (Sun et al., 2014). Rather than discussing which software may best provide for visualization, our focus is on templating coopetition through the ordering of visuals. Accordingly, the approach we have taken has been first to consider how visuals have been used in the literature on coopetition, and then to examine visuals regarding selected related topical words, namely cooperation, competition, dynamics, sequence, dyadic, network, objectives, governance, value creation, industry, value creation, innovation, drivers, processes, and outcomes. As a supplement to this, coopetition was crossed with these topical reference words via the internet, providing additional visuals through search engines such as Google Image. Finally, coopetition was also crossed with terms of visual representation, namely decision trees, graphs, figures, templates, diagrams, tools, photos, tables, pictures, charts, drawings, and displays.

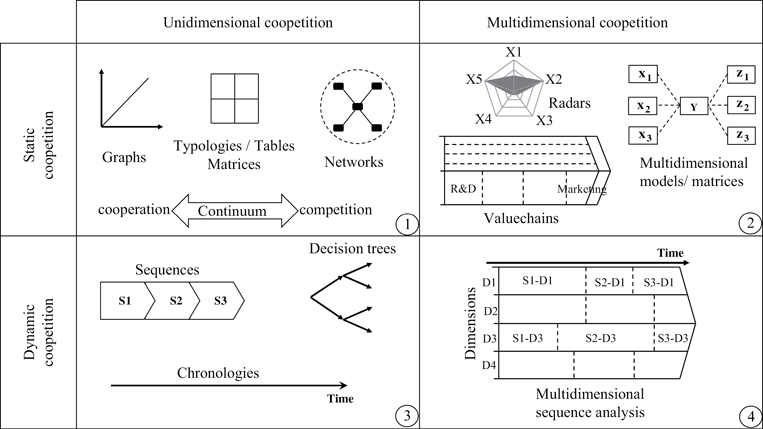

To put the findings in order in the exercise of envisioning coopetition, three sections are proposed. First, views on coopetition are discussed, with a specific focus on the visual perspective. Second, a meta-table is presented, cataloging visuals on attributes of coopetition stemming from a literature review and search engine images. Coopetition is viewed as an interactive process occurring between and/or within firms, composed of a mixture of cooperative and/or competitive moves that may lead to added value for the firm. The interactive process itself may develop in different dimensions, i.e., relating to products, services, supply chain, research and development, etc. For this reason, the meta-table on generic forms of visuals highlights two facets of coopetition: static versus dynamic, and unidimensional versus multidimensional. Finally, from the meta-table, a synthetic visual template derived from dynamic/multidimensional coopetition is proposed and discussed.

Views on coopetition

Coopetition may be viewed as deriving from two possible starting points. In the first, a firm assesses its competitive environment and seeks opportunities to cooperate accordingly. Inversely, in the second, a firm assesses its resources, capabilities, and business network relationships, and seeks to cooperate accordingly. With this in mind, it is critical to consider affiliated evidence regarding industrial organization, emphasizing the competitive environment of the firm, as well as strategy, putting the focus on the idiosyncrasies of the firm, when considering both Michael Porter (1980) and Brandenburger and Nalebuff’s (1996) diamond visuals on gaining competitive advantage.

Firm- versus industry-centric views on coopetition

In Porter’s visual competitive advantage, strategy and rivalry depend on the conditions of supply and demand that co-exist with the scope of support within the industry, with the whole being inserted into a context of public regulatory policies. It focuses on the characteristics and profitability of the industry. Economic performance is related to the behavior of buyers and sellers as driven by industry structure. In other words, maximizing profit or gaining competitive advantage mainly pertains to the search for market power and is dependent on barriers to entry, monopoly, oligopoly, or atomistic markets, and contestability (Baumol et al., 1982). In so doing, strategic rent-seeking behavior may be seen as reducing strategic risk (Lado et al., 1997).

Under a similar diamond format, Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) and Dixit and Nalebuff (2008) propose examining competitive advantage from the inside view of the firm. Demand conditions become identified customers, supply/suppliers, competition/competitors, industry support/complements. It therefore defines an additional framework for strategists, the so-called PARTS structure game (with P standing for the number of competitive game players, A for company added value, R for rules of the game, T for tactics, S for scope of the businesses that are in opportunistic relationships with the players).

Thus, in a way the two different perspectives echo whether coopetition is looked at from either a player’s (actor school of thought) or industry (activity school of thought) perspective (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016), or, as pointed out by Grant (1991), coopetition must be seen as an inside-out process of strategy formulation. From the point of view of the firm, in terms of the industry, the concept proposes an alteration of the traditional interplay between market forces. Coopetition lies in between perfect competition and collusion. From the inside of the firm perspective, it introduces a rethinking of the dimensions of the supply and distribution channels of the business, products, services, supply chain, and R&D in interaction with competitors.

Sequential versus simultaneous views on coopetition

In support of the aforementioned diamond, Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) developed a dynamic game framework that visualizes coopetition as cooperative, followed by a competitive sequence. The “game of the business” illustrates, in a simplified version, a firm facing a competitor. According to payoffs in visual matrices, in a first phase the firm would increase the net creation of collective value through cooperation, and then in a second phase it would compete for apportionment of the added surplus. However, in this regard, there has been little investigation into the visualization of coopetition by means of matrices or by making use of game theory. Despite examples illustrating the interest in using game theory to rethink mutual interactions with competitors, the concept seems to have provided more insights than practical use for decision makers. The relevance of game theory itself in business strategy has been subject to skepticism (Shapiro, 1989).

At the same time, it should be noted that cooperation and competition within a game theory framework has been studied not only with respect to strategy but also in other social sciences and biology (Nowak, 2006). In particular, extended work on cooperation has incorporated network analysis (Axelrod and Amilton, 1981) and complex systems approaches (Axelrod, 1997), leading to additional visuals such as graphs on evolutionary dynamics (Allen et al., 2017).

Rather than from a game-theoretical perspective, the concept of coopetition has been increasingly examined as primarily nested in an assessment of the resources and dynamic capabilities of firms (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney & Clark, 2007). As a result, Bengtsson and Kock (2000) have addressed a further issue of cooperation and competition, specifically as not occurring in succession but rather taking into consideration simultaneous strategic moves, leading to new coopetition visuals, which are discussed below. This approach has paved the way for an array of publications in academic journals. Over the past two decades, the number of publications in journals with ISI impact factors of above 0.5 has grown from two in 1996 to more than twenty in 2014 (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016).

Thus, with the support of the game theory framework, coopetition thinking has provided both primary visuals and a synthesis of the resulting cooperative advantages, both concerning the economic environment and industry structure as well as the idiosyncratic resources of the firm.

Accordingly, a broad sweep on coopetition permits the elicitation of two properties of the concept: first, it is an interactive, dynamic process. Coopetition as the focus of game theory is about timely strategic moves that may occur in particular environments, with a possible succession of competition and cooperation phases. It may be looked upon as finite or infinite depending on the length of the period of time under consideration, with a start and an end as a transforming process in business strategy. Second, coopetition may also develop simultaneously on multiple business dimensions at the industry level (market segments, geographic location, etc.) and/or at the firm level (organizational units, products, value-chain activities, etc.). For instance, competitors may cooperate in R&D or infrastructure platforms while competing for products and services (Cassiman et al., 2009). Similarly, they may compete in one geographical market while simultaneously cooperating in another (Lehiany & Chiambaretto, 2014).

Exploring visuals

In consideration of the above coopetition properties, it is possible to explore the way coopetition can be illustrated. On the one hand, coopetition has been depicted in either unidimensional or multidimensional perspectives (Bengtsson et al., 2010). Drawing on graphs, typologies, matrices, continua, networks, chronologies, trees, and other forms, the unidimensional perspective aims at depicting the intensity (Bengtsson et al., 2010; Luo, 2005, 2007), nature (Dagnino & Padula, 2002), or dynamics of coopetition over a given dimension. The multidimensional perspective, in turn, builds on multidimensional figures and frameworks to illustrate the different areas in which coopetition takes place (Dumez & Jeunemaître, 2006a), the different levels of coopetition strategies (Dagnino & Padula, 2002), or the complex articulation between different components explaining coopetition (Bengtsson & Raza-Ullah, 2016). Unidimensional versus multidimensional perspectives represent then a first line of inquiry structuring the way coopetition can be conceptualized and illustrated.

On the other hand, the phenomenon of coopetition has been templated either from a static or dynamic perspective. Building on graphs, typologies, matrices, networks, and continua, the static perspective depicts coopetition in terms of the interactions between actors (see for instance Le Roy & Guillotreau, 2010; Hu, 2014; Wiener & Saunders, 2014), referring to the state of the relationship at a given moment. This perspective therefore assumes that coopetition is a particular, hybrid form of relationship in which competitive and cooperative components occur simultaneously (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000; Yami & Le Roy, 2010). In contrast, the dynamic perspective, building on chronologies, sequences, or decision trees, puts the stress on processes that structure coopetition over time (see Dumez & Jeunemaître, 2006b; Bengtsson et al., 2010; Lehiany & Chiambaretto, 2014). This perspective illustrates successive sequences or continuous timelines where two or more companies alternatively compete and cooperate.

From the above differentiating considerations—i.e., static versus dynamic, unidimensional versus multidimensional—a meta-table on coopetition visuals may then be proposed with pre-formatted templates stemming from the literature and from Google Image sources (see Table 25.1). In other words, using heterogeneous sources of data and information, reflecting upon generic pre-formatted visuals may help with a reading of the concept in a more consistent and uniform way (Dumez, 2016). The visuals presented below will not be commented on one by one, but rather only where they have significance.

Static-unidimensional coopetition

In the upper-left part of the quadrant, coopetition is studied as a hybrid form of interaction. Competitive and cooperative components occur in a particular period of time and on a single dimension—a business, market segment, supply chain function, organizational division, or strategic level of analysis—under a defined mutual objective. For instance, Bengtsson and Kock (2000) summarize the balance between the extremes of the coopetitive continuum, which may result a in cooperation-dominated relationship, an equal relationship, or a competition-dominated relationship. Other qualitative visual typologies characterize coopetition as active or passive, with possible mixed flexible outcomes (Czakon & Rogalski, 2014). The interest of such visuals is to better apprehend the intensity of coopetition within a continuum between competition and cooperation and the rise of the coopetition concept in a game structure (Padula & Dagnino, 2007).

Also, visuals provide an account of the coopetitive environment and the underlying motives through the lenses of matrices or tables (Carfì & Musolino, 2015). For example, focusing on different possible levels of competition and cooperation, Luo (2007) typifies coopetitive situations as contending, adapting, isolating, or partnering. Is the situation governed by small or large global enterprises, and with a greater or lesser influence of foreign markets? Are coopetitive situations dispersing, networking, concentrating, or connecting (Luo, 2007)? This goes along with the motives for cooperation, which is another studied dimension, whether the main focus is added knowledge or economic value even if driven by rent-seeking strategic behavior. Motives may range from entering new markets, time savings, increases in bargaining power, gaining scale and scope, gaining qualified labor, access to new knowledge diversification, or costs savings. The motives may take place in environments driven by destructive creation, hyper-competition, competition, collusion, or monopoly.

The possible areas of cooperation or collaboration comprise another research dimension, concerning development, sharing of existing knowledge, infrastructure, certification and standards, or government policies. These are embodied in looking at governance models, including more or less formal agreements such as equity or non-equity alliances and pre-conditions for cooperation that may apply to production, or distribution and sales. Static visuals on one dimension permit the characterization of coopetition according to proxy qualitative or quantitative variables on an abscissa and ordered at the origin (Wiener & Saunders, 2014). Of course, as a strategic project, the stability of coopetition hinges on a shared cultural value dimension where profiles in partnerships may be driven by similarities, reputations, the strategic fit of coopetitors, relational risks by opportunism, or the appropriation of resources and/or competencies. Thus, the upper-left part of the quadrant enables visual constructs that focus on a static rationale for coopetition according to a chosen dimension and that provide insights into the coopetition balance of power (Velu, 2016).

Static-multidimensional coopetition

In the upper-right part of the quadrant, coopetition is studied as a static interaction on multiple dimensions. At a given time point, different market segments can be crossed with the intensity of cooperation within clusters of firms, for example, regarding co-investment and location (Arthanari and al., 2015). In the selected dimensions, the points at which cooperation and competition occur simultaneously can be identified, or how the creation and appropriation of the value of coopetition combines added knowledge with network effects (Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2009) or for the intra-organization units of the firm (Tsai, 2002). For instance, through a value chain analysis, cooperation and competition occur simultaneously across different activities. Matrices, radar, or value-chain visuals may be appropriate for this purpose (Cassiman et al., 2009) or regarding types of coopetition governance in several dimensions (Bouncken & Fredrich, 2016).

Dynamic-unidimensional coopetition

The lower-left part of the quadrant addresses coopetition as an interactive process made up of successive phases of cooperation and competition occurring on a single dimension—a business, market segment, supply chain function, organizational division, or strategic level of analysis—under a possibly changing mutual objective. Coopetition develops over time through phases of competition and cooperation, as stated in the game theory perspective developed by Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996). These phases may be expressed under different displays, concentrating on a given set of firms and an industry (Okura, 2007). A visual tree is a suitable generic pre-format for conveying coopetition decision making processes (Rodrigues et al., 2011), in conjunction with objectives and the environment. In particular, it questions whether a risk matrix may be worked out that crosses capacity and resource utilization with expected synergies and profits.

Dynamic-multidimensional coopetition

The lower-right part of the quadrant is typical of sequence analysis occurring on multiple dimensions—businesses or market segments, supply chain functions, or organizational divisions—under plausible changing mutual objectives. For instance, Dumez and Jeunemaître (2006a) developed a multidimensional strategic sequence analysis that builds on three strategic dimensions: the market (strategies in prices, quantities, marketing, etc.), market boundaries (strategies aiming at redefining market boundaries and structure, such as mergers and acquisitions, product bundling, tying), and the non-market environment (lobbying, antitrust, corporate social responsibility; Baron, 1995), showing how companies may compete in one dimension while simultaneously cooperating in others. Other dynamic multidimensional models have been developed (Raza-Ullah et al., 2016), drawing, for instance, on the competition context (industrial, relational, and firm-specific factors) along with the coopetition paradox (cooperation versus competition) and tensions in coopetition (emotional ambivalence at the organizational and inter-organizational levels).

Visuals on the achievement of coopetition objectives suggest that the time scale is a determining factor of analysis. When viewed from complex systems mathematical figures, and considering the Matthew effect, coopetition as the learning curve accumulates advantage over time. As a result, evolutionary game systems indicate that the prevalence of long-term learning, together with random elements, preserves cooperative stability (Allen et al., 2017).

Proposing a visual template for studies on coopetition

The purpose of this section is not how to interpret and analyze coopetition, but rather to propose an intermediate tool that organizes collected raw material (quantitative and/or qualitative data) on cooperative processes with the analysis itself; in other words, it provides a visual framework template. The interest in such a framework is to help researchers collect the most relevant data on the process to be studied, in accordance with the appropriate issues to be raised.

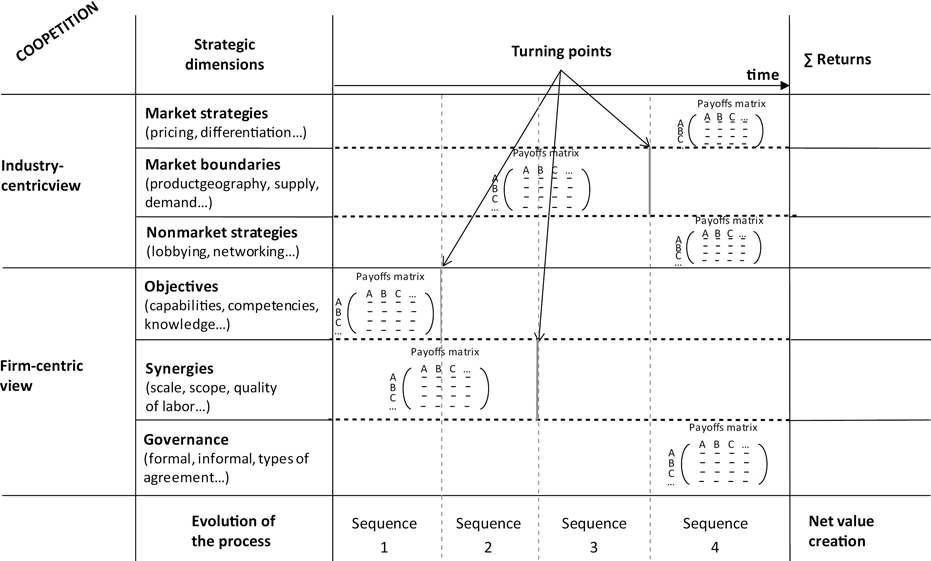

Based on the previous section, the template (described in Figure 25.1) shall incorporate two properties of coopetition: that coopetition is a process and therefore requires a dynamicperspective, and the importance of including one or more dimensions of interaction. The template shall therefore be both chronological and multidimensional.

Describing the template

The first column refers to the different possible dimensions of coopetition. These dimensions can be categorized from the point of view of the market in which coopetition is to be played out (market, market boundaries, and non-market), as well as from the internal point of view of the firm (objectives, synergies, governance).

The second column provides a dynamic layout of the cooperative processes by sequences and by dimensions. The process is broken down into identified sequences that are separated by focal turning points. Each sequence is identified by a payoff matrix.

The third column expresses what is expected by the actors (Σ returns) and what has or has not been fulfilled (net value creation).

The template draws the researcher’s attention to three fundamental elements. The coopetition process may thus be studied on different, clearly defined dimensions, for example, in order to identify the tensions between dimensions (Fernandez et al., 2014) that are inherent to the process. Put differently, if there is a change in the coopetition process, in which dimensions is the change accounted for?

The sequences of the coopetitive process (entry into the process, new sequence in an ongoing process) can be characterized by payoff matrices. Firms make assumptions about the predictable gains that they may achieve from cooperation with their competitors, as well as the gains that their competitors may achieve. During the process, valued matrices may change, either by evolution or by revolution. Then, turning points occur that trigger a move from one cooperative sequence to another.

Assessing coopetition outcomes

As there are turning points, it is necessary to distinguish between the ex ante point of view and the ex post point of view with respect to what was expected and what was fulfilled. A firm may decide to enter into a coopetition agreement with one or more competitors because it believes that it will achieve gains in the process and that competitors will make equal or lesser gains (but undoubtedly not higher). Matrix estimates are done ex ante before entry into the process. Once firms are involved, each periodically reviews the evolution of the estimates and looks at whether or not the expected gains have materialized and how the situation of the partners has developed. If the company understands that the gains it has received from coopetition are lower than those it had expected ex ante or that the gains of competitors are higher than anticipated, tensions may then appear in the coopetition process that could possibly lead to a turning point.

In the same way that the ex ante and ex post perspectives shall be isolated, it is also necessary to separate between the actors’ and the researchers’ points of view (Dumez, 2006b). Of course, in a process as complex as coopetition, which is easily unstable, involving many players and multiple dimensions, firms may be mistaken in assessing expected gains (theirs and those of their competitors) as to whether their evaluations fulfill (or not) their expectations. It is therefore crucial for the researcher to identify the possible cognitive biases of the actors (excessive optimism or pessimism, over- or under-reaction to particular events). Accordingly, the template invites the collection of accurate data in the construction of payoff matrices that may have led two or more companies to a coopetitive sequence regarding the key events driving a revision of the matrices, i.e., a turning point leading to a new sequence in the coopetition process. The issue is identifying the key dimension(s) that may have been causal in a turning point sequence change. To that end, it is likely that there is an interest in combining quantitative with qualitative analysis. When quantitative matrices are workable using plausible estimates, the analysis of returns and net value creation will be more rigorous. Nevertheless, qualitative assessment of the data can also constitute a major step towards rigorously analyzing the sequential process of coopetition. In order to gain access to these matrices, it is essential to carry out qualitative analyses (interviews with the actors involved, analysis of in-house documents, press articles) regarding how firms have ex ante anticipated their potential gains and those of their competitors as well as how they estimated gains or losses in the process, to complement and articulate with the quantitative analysis.

As mentioned above, the template is not intended to analyze coopetitive processes. For example, it does not in itself provide causal explanations. Instead, it helps to prepare this analysis: first, by identifying gaps in the collected material (do the data make it possible to ex ante reconstruct the expected payoff matrices of actors and their progress over time? How can the dynamics of the actors’ thinking about their diminished or fulfilled expectations and about anticipated competitors’ gains be reconstructed?); second, it helps to identify the critical dimensions and events that have structured the coopetition process (and, again, to identify gaps in the data to reconstruct critical events); finally, it helps in developing a narrative on the coopetition process from its inception (the expected gains by the different actors) and then with the delineated sequences. Narration renders the process intelligible (Abbott, 2001; Dumez & Jeunemaître, 2006b) and represents a further step in the treatment of the empirical material, allowing a deeper level of analysis and interpretation.

Conclusion

Publications on coopetition make use of diagrams and figures, highlighting two important points. First, coopetition may be seen from an outside view of the firm—in the tradition of industrial economics—or from an internal one—in the tradition of the resource-based view of the firm. These two perspectives on coopetition have occasionally been viewed in opposition and as complimentary. Second, visuals illustrate that research on coopetition is structured by two dimensions: static versus dynamic and uni- versus multi-dimensional. On this basis, a multidimensional coopetition sequence analysis (MCSA) template has been put forward. It attempts to articulate internal and external views on cooperation, multidimensionality, and a sequential analysis of its dynamics. In itself, the template is not solely an analytical tool, but is rather intended to facilitate the theorizing of coopetitive processes.

References

Abbott, A. (2001). Time Matters. On Theory and Method. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Allen, B., Lippner, G., Chen, Y.-T., Fotouhi, B., Momeni, N., Yau, S.-T., & Nowak, M. A. (2017). Evolutionary dynamics on any population structure. Nature, 544(7649), 227–237.

Arthanari, T., Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2015). Game theoretic modeling of horizontal supply chain coopetition among growers. International Game Theory Review, 17(2).

Axelrod, R. (1997). The Complexity of Cooperation: Agent-based Models of Competition and Collaboration. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Axelrod, R. & Hamilton, W. (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211(4489), 1390–1396.

Barney, J. B. & Clark, D. (2007). Resource-based Theory, Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baron, D. P. (1995). Integrated strategy: market and nonmarket components. California Management Review, 37(2), 47–65.

Baron, D. P. (1996). Business and Its Environment. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Basole, R. C. (2014). Visual business ecosystem intelligence: lessons from the field. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 34(5), 26–34.

Bates, R. H., Greif, A., Levi, M., & Rosenthal, J.-L. (1998). Analytic Narratives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Baumol, W. J., Panzar, J. C., & Willig, R. D. (1982). Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Bengtsson, M., Eriksson, J., & Wincent, J. (2010). Co-opetition dynamics – an outline for further inquiry. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 20(2), 194–214.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2000). Coopetition in business networks-to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition—Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188.

Bengtsson, M. & Raza-Ullah, T. (2016). A systematic review of research on coopetition: toward a multilevel understanding. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 23–39.

Brandenburger, A. & Nalebuff, B. (1996). Coopetition. New York: Doubleday Publishing Group.

Bouncken, R. B. & Fredrich, V. (2016). Learning in coopetition: Alliance orientation, network size, and firm types. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1753–1758.

Carfì, D. & Musolino, F. (2015). A coopetitive-dynamical game model for currency markets stabilization. Atti della Accademia Peloritana dei Pericolanti-Classe di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche e Naturali, 93(1), 1.

Cassiman, B., Di Guardo, M. C., & Valentini, G. (2009). Organising R&D projects to profit from innovation: Insights from co-opetition. Long Range Planning, 42(2), 216–233.

Chiambaretto, P. & Dumez, H. (2016). Toward a typology of coopetition: a multilevel approach. International Studies of Management & Organization, 46(2–3), 110–129.

Czakon, W. & Rogalski, M. (2014). Coopetition typology revisited–a behavioural approach. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 28–46.

Dagnino, G. B. & Padula, G. (2002). Coopetition strategy. A new kind of interfirm dynamics for value creation. Communication at EURAM second annual conference, Stockholm, May 9–11, 2002.

Dixit, A. K. & Nalebuff, B. (2008). The Art of Strategy: A Game Theorist’s Guide to Success in Business and Life. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Dumez, H. (2006). Why a special issue on methodology: Introduction. European Management Review, 3(1), 4–6.

Dumez, H. (2016). Comprehensive Research: A Methodological and Epistemological Introduction to Qualitative Research. Copenhagen: CBS Press

Dumez, H. & Jeunemaître, A. (2000). Understanding and Regulating the Market at a Time of Globalization: The Case of the Cement Industry. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press Ltd.

Dumez, H. & Jeunemaître, A. (2006a). Multidimensional strategic sequences: A research programme proposal on coopetition. 2nd Workshop on Coopetition Strategy, 2006, Milan, Italy.

Dumez, H. & Jeunemaître, A. (2006b). Reviving narratives in economics and management: Towards an integrated perspective of modelling, statistical inference and narratives. European Management Review, 3(1), 32–43.

Esty, D. C. & Geradin D. (Eds) (2001). Regulatory co-opetition. In Regulatory Competition and Economic Integration: Comparative Perspectives (chapter 2, pp. 30–47). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Song, Y. (2016). Pursuit of rigor in research: Illustration from coopetition literature. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 12–22.

Gnyawali, D. R., He, J., & Madhavan, R. (2006). Impact of co-opetition on firm competitive behavior: An empirical examination. Journal of Management, 32(4), 507–530.

Golnam, A., Ritala, P., & Wegmann, A. (2014). Coopetition within and between value networks–a typology and a modelling framework. International Journal of Business Environment, 6(1), 47–68.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135.

Hu, J. (2014). Bipartite consensus control of multiagent systems on coopetition networks. Abstract and Applied Analysis, article ID 689070, 9 pages.

Jorde, T. M. & Teece, D. J. (1990). Innovation and cooperation: implications for competition and antitrust. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(3), 75–96.

Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Hanlon, S. C. (1997). Competition, cooperation, and the search for economic rents: a syncretic model. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 110–141.

Lehiany, B. & Chiambaretto, P. (2014). SMAA: A framework for a sequential and multidimensional analysis of alliances. Management international/International Management/Gestiòn Internacional, 18, 85–105 (in French).

Le Roy, F. & Guillotreau, P. (2010). Successful strategies for challengers: competition or coopetition with dominant firms? in Yami, S., Castaldo, S., & Dagnino, G. B. (Eds), Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century (chapter 12, pp. 238–255). Chelthenham: Edward Elgar.

Luo, Y. (2005). Toward coopetition within a multinational enterprise: a perspective from foreign subsidiaries. Journal of World Business, 40(1), 71-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2004.10.006

Luo, Y. (2007). A coopetition perspective of global competition. Journal of World Business, 42(2), 129–144.

McWilliams, A. & Smart, D. L. (1993). Efficiency v. structure-conduct-performance: Implications for strategy research and practice. Journal of Management, 19(1), 63–78.

Nowak, M. A. (2006). Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science, 314(5805), 1560–1563.

Okura, M. (2007). Coopetitive strategies of Japanese insurance firms a game-theory approach. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 53–69.

Padula, G. & Dagnino, G. B. (2007). Untangling the rise of coopetition: the intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 32–52.

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press.

Ritala, P. & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2009). What’s in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation, 29(12), 819–828.

Rodrigues, F., Souza, V., & Leitão, J. (2011). Strategic coopetition of global brands: a game theory approach to ‘Nike+ iPod Sport Kit’co-branding. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 3(4), 435–455.

Shapiro, C. (1989). The theory of business strategy. The Rand Journal of Economics, 20(1), 125–137.

Sun, G., Wu, Y., Liu, S., Peng, T. Q., Zhu, J. J., & Liang, R. (2014). EvoRiver: Visual analysis of topic coopetition on social media. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 20(12), 1753–1762.

Tadelis, S. (2013). Game Theory: An Introduction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

Tsai, W. (2002). Social structure of “coopetition” within a multiunit organization: Coordination, competition, and intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organization Science, 13(2), 179–190.

Tufte, E. R. (1990). Escaping flatland. In Envisioning Information (chapter 1, pp. 12–36). Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press LLC.

Velu, C. (2016). Evolutionary or revolutionary business model innovation through coopetition? The role of dominance in network markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 53 (February), 124–135.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

Weiss, L. W. (1979). The structure-conduct-performance paradigm and antitrust. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 127(4), 1104–1140.

Wiener, M. & Saunders, C. (2014). Forced coopetition in IT multi-sourcing. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 23(3), 210–225.