Introduction

Coopetition creates tensions that can be extremely strong and can jeopardize the effective pursuit of coopetition (Bonel & Rocco, 2007). Therefore, managing tensions is a critical task for coopetitive organizations and an essential condition for achieving performance (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Chen, 2008; Raza-Ullah et al., 2014). Within the strategy field, researchers of coopetition investigate management tools to provide solutions that will reduce coopetitive risks and tensions (Fernandez & Chiambaretto, 2016; Fernandez et al., 2014; Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001; Luo, 2007; Peng & Bourne, 2009; Seran et al., 2016), while within the management accounting field, authors focus on studies of inter-organizational cooperation, which include coopetitive relationships (Dekker, 2016; Grafton & Mundy, 2016; Mouritsen & Thrane, 2006; van der Meer-Kooistra & Scapens, 2008). The purpose of this chapter is to combine management accounting and strategy approaches in a discussion about coopetition management.

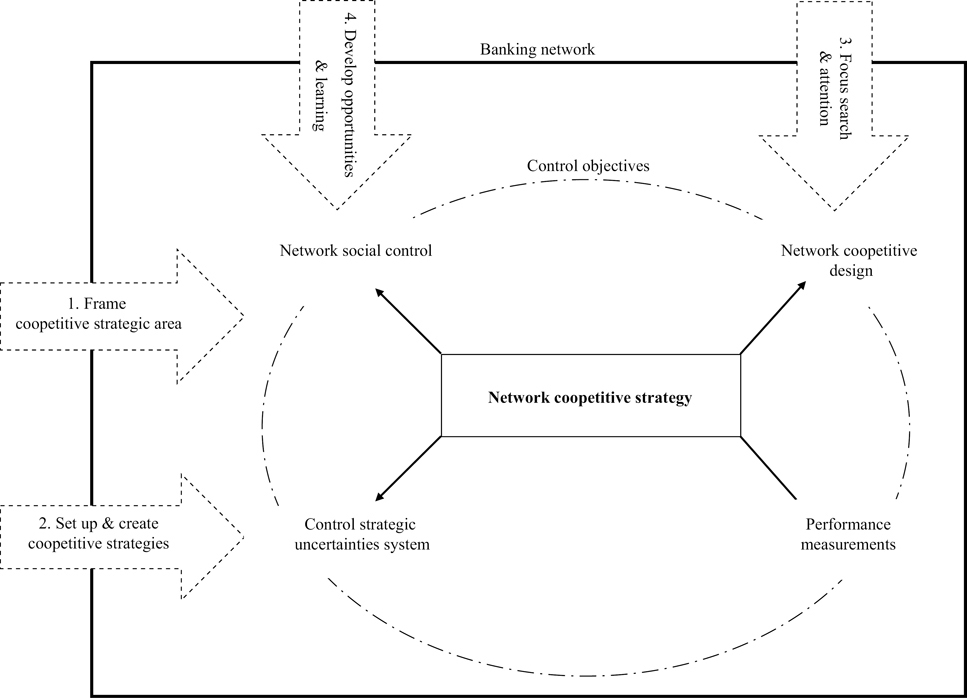

A literature review is conducted that combines two theoretical corpuses. At an organizational level, a consensus exists between the two approaches, even though the authors may use different terms to explain how formal and informal controls are mobilized to manage coopetitive tensions. At a network level, coopetitive and management accounting literatures offer general management principles, but they do not converge to explain how control mechanisms contribute to coopetition success (Czakon et al., 2014). Accordingly, we focus our research on a network, and we propose an integrative management accounting framework that can be applied to manage network coopetitive tensions. This framework is illustrated by a detailed analysis of the coopetitive network governance within the banking industry.

Levels of coopetitive tensions

Given that coopetitive tensions may come from several sources, Fernandez et al. (2014) develop a multi-level conceptual framework to understand key drivers of tension in coopetition and key approaches to managing that tension. We propose to aggregate coopetitive tensions according to levels and sources involved to clarify the principles applied (Table 34.1).

Table 34.1Coopetitive tensions and principles

| Levels | Coopetitive Tensions | |||

| Personal | Organizational level

(dual-level analysis) |

Network level | ||

| Inter-personal | Intra-organizational | Inter-organizational | Intra- and inter- network | |

Sources |

Belonging to the parent firm and coopetitive identity |

Allocation of resources and creation of appropriation of business unit value |

Value creation and appropriation | |

Knowledge sharing and learning |

Resource and power asymmetry | |||

Principles |

Separation-integration and combining both separation and integration |

Sponsorship or integration | ||

At the individual level, partners face continual pressures to manage cooperative and competitive tensions that emerge from collaboration with competitors. Explicit and implicit strategic priorities may lead to different mindsets and behaviors with respect to managers (Fernandez et al., 2014) and, hence, belonging to opposing firms is a source of cognitive dissonance and psycho-cognitive stress for managers (Dekker, 2016; Seran et al., 2016).

At the intra-organizational level, units cooperate to simultaneously develop synergies and scale effects, while also competing for internal limited technological human and financial resources (Luo et al., 2006; Seran et al., 2016).

At the inter-organizational level, the first tension arises due to the confrontation between common value creation and private value appropriation (Gnyawali et al., 2012; Madhavan, 2012). A partner who increases his or her resources and competences so that they exceed those of his or her coopetitor will gain a competitive advantage in future competition. As a consequence, tensions may then appear when each partner attempts to capture the previously created value (Cassiman et al., 2009). The second conflict is due to the risks associated with the transfer of confidential information and the risks of technological imitation. Partners join strategic resources to achieve their goals (Gnyawali & Park, 2009). However, at the same time, they must protect their core competencies from their competitors. Sharing information with their competitors, in subtle ways over time, may introduce homogeneity into their products and reduce the distinctiveness of each firm (Grafton & Mundy, 2016). In some cases, regulatory risk could also be a source of tension, and when such tension appears, it is a particularly salient concern (Anderson et al., 2014). Indeed, any exchange of information between competitors exposes them to the risk of perceived or real collusion, and hence, potentially could result in their being subject to anti-competition legislation (Grafton & Mundy, 2016).

At the network level, competition intensifies as the life cycle advances toward maturity (Baum & Korn, 1996; Bettis & Hitt, 1995; Korn & Baum, 1999). Tensions are specific and more intense during this process given that members’ interests may become more conflicted if the industry shrinks (Luo, 2007). The resources and power of each competitor structure the network and significantly influence coopetition (Ketchen et al., 2004).

While these principles appear meaningful conceptually, we know little about how to help a network manage the tensions in coopetition. Therefore, to deeply understand which mechanisms contribute to network coopetition success, we investigate an integrative management accounting framework and illustrate it using a banking industry case.

Banking inter-network coopetition

Cooperative banking, a part of the banking industry, is a perfect illustration of a network coopetitive case. In Europe, cooperative banking is an important economic sector that offers access to more than 71,000 bank agencies and employs approximately 850,000 people (EACB, 2017). BP-CE2 is the third important cooperative banking network in France and is classified as one among the top thirty systemic banks in the world by the Financial Stability Board.

In the last few decades, coopetitive activities have become more frequent in the cooperative banking sector, for three reasons. The first is linked to the application of the 1984 Finance Act, which ended the privileges of cooperative banks, forcing them to diversify, acquire new skills, and make alliances with competitors through internal or external development. As a result, cooperative banks established coopetition within the same bank network or with competitor bank networks.

The second reason for the acceleration of the phenomenon of coopetition in the cooperative banking network is the impact of the international legal environment in the banking sector. To satisfy the criteria of prudential rules following the 2008 crisis, banks must now prove the viability of their business model, demonstrate their credit risk and their low risk of governance, and publish all relevant information (Bonomo et al., 2016).

The third reason is the digitalization of the banking sector, particularly considering that new entrants are major companies in information technology, e-retailing and media (Fintech). While these Fintech players are not yet competitors of banks, they offer targeted and more convenient services. Hence, corporate and investment banks, as well as retail banks, are now embracing coopetition by taking these Fintech players as news partners in their ecosystems.

In 2009, the Group Central Institution BP-CE founded a common board to manage the coopetitive activities of the two networks, BP and CE (Figure 34.1).

Their competitive and cooperative activities are summarized in Table 34.2. These two networks include regional banks, which are independent banks competing in the areas of sales activities. In these two networks, Caisse d’Epargne (CE) and Banque Populaire (BP), competitive activities account for 64.5% of the total net banking income (traditional retail and commercial banking activities) and are conducted by eighteen banks in the BP network and seventeen in the CE network.

Table 34.2Cooperative and competitive activities

| Competitive activities (65% of net banking income) | Banking products sales |

| Cooperatives activities | Common information system management |

| Regulatory risk management | |

| Networks representation activities |

Cooperative activities and coopetitive tensions

The cooperative activities of these two banking networks include a shared information system, three common management funds and the joint representation of external actors (customers, financial markets, government, financial regulators). These activities are monitored by two organizations, namely the IT group central institution and the group central institution.

IT system tensions

Some tensions are created by shared information technology systems (IT systems). Initially, both networks had their own information system, but in 2015 they decided to jointly manage a new shared information system. The objectives behind this collaboration in digitalizing their banking activities were mainly to reduce IT costs and time to market, and to consolidate their network expertise and competencies. While the IT Group Central Institution was created to manage this cooperative activity, once the integration strategy was defined and approved by the IT Group Central Institution, common strategy reduced the regional banks’ bargaining powersand freedom of choice. Consequently, tension appeared as banks compared the costs of their contributions to this common project to the gains in terms of knowledge and customer data.

Risk management tensions

Tensions could also be created by regulatory risk management. In addition to their own fund management system, the two networks created a second common governance board, namely the Group Central Institution, to manage global coopetitive strategies, mutual funds and prudential compliance. Thus, since 2009, the global network financial risk has been supported by a common fund, the Fonds de Garantie Mutuel (FGM), in which the BP network and the CE network have each deposited €180 million.

The objective of common funds is to ensure coherence, solvency, and liquidity for the two banking networks and their subsidiary, Natixis. Therefore, the operating rules regarding these common funds establish the terms and conditions for member contributions. Although these mechanisms were originally established under a mutualist reinsurance approach, this solidarity, perceived as the distinctive value of cooperatives, creates tensions. For Natixis, in past crises, the equity and liquidity of all the banks in the two networks were called upon to financially support Natixis’ risky activities. This solidarity placed the two cooperative networks in a difficult situation and, as a consequence, their opening-up to the stock market resulted in tensions between the Group Central Institution and the listed subsidiary with all the banks in the two networks. Indeed, using of external capital considerably increase the cost of financing cooperatives and increase the need for profitability of their activities.

The Group Central Institution is also responsible for prudential consolidation, which is a consolidation of the financial risks and the performance of the two networks to fit financial prudential standards requirements. This financial consolidation brings together the balance sheets of the independent banks that belong to the two networks to offset the risks and performances of these banks. As the two banking networks include independent regional banks whose competitive advantages and individual risks depend strongly on the economy of the territory, they must engage in financial consolidation to compensate for the risks. However, the prudential consolidation creates tensions among the regional banks since the regional banks must provide more relevant information, such as financial statements, in accordance with prudential rules to avoid the exclusion of the network.

Networks representation tensions

At last, tensions could be created by networks representation activities. The Group Central Institution represents regional banks and negotiates and signs national and international agreements on their behalf. It also manages their interests and establishes coopetitive banking network strategy (Moody, 2016: 18). However, because conflict arises between cooperative and shareholder values due to the diversity of the two networks’ property structures (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001), it is becoming increasingly more difficult for the Group Central Institution to ensure the cohesion of the network and defend mutualist values (democracy and solidarity). Furthermore, the tension between the BP and CE cooperative networks and Natixis is due to the shared common fund and the opposition in value between the network’s actors, i.e., capitalist values for Natixis and cooperative values for the rest of the network. Cooperative network banks are owned and governed by their members such that each member clearly holds a vote in the democratic process in accordance with the one-person-one-vote democratic principle. The ideal cooperative bank seeks to maximize the benefits of its members (who are also customers) and maximize consumer bonuses. However, with respect to Natixis, even if it is a subsidiary of BP and CE, it has a shareholder logic whereby maximizing the rate of return on capital is, if not the exclusive, at least the dominant business objective.

Management accounting tools

To manage tensions within a coopetitive inter-network we have to understand the role of management accounting in a cooperative network. As summarized in Table 34.1, separation, integration, and combining are the three principles employed to manage tensions at the individual and organizational levels. At the network level, resources and power depend on centrality, property structure, and network density (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001), and two principles are identified to manage coopetitive tensions—sponsorship and integration (Luo, 2007). Sponsorship refers to the effort to “pacify the volatility of steep rivalry among competitors,” to “establish collaborative opportunities and platforms for members to share complementary resources,” and to “create more favorable conditions” such as “competitive pressures from new entrants and substitutes and bargaining power from suppliers and buyers or government policies and international treaties” (Luo, 2007). Luo (2007) shows that integration is an effort to put a firm’s coopetition scheme under a unified and coordinated umbrella to better nurture the implementation of this global strategy to establish a well-coordinated coopetition program and prioritize the role played by each member.

While knowledge about principles is acknowledged, little is known about the tools to use. Management control mechanisms include a control system design that is based primarily on an information system used to share information and governance. Additionally, it encompasses performance measurement systems, such as goal setting, incentive systems, and performance monitoring, and involves process or behavioral control, social control, and informal control (Table 34.3). These control mechanisms must first be clarified from a perspective that will facilitate their use in a network with complex cooperative and competitive relationships.

Table 34.3Synthesis of management control mechanism and tools

| Management control mechanisms | Tools |

| Inter-organizational management controls systems design | Design of tasks, information sharing, information technology |

| Performance measurement systems | Goal setting, incentive systems, performance monitoring, and executive rewards |

| Process controls | Rules, regulations, structures, job descriptions, reporting structures |

| Behavioral control, social control, informal control | Trust, socialization processes, values |

At the organizational level, both coopetitive and management accounting literatures agree on the role of formal and informal control as tools to manage coopetitive tensions. Several studies have emphasized that formal and informal control mechanisms do not work separately and must be combined to manage tensions between partners and increase alliance performance (de Man & Roijakkers, 2009; Faems et al., 2008). Seran et al. (2016) provide an in-depth study of leading French banking institutions to unveil how formal and informal management helps individuals cope with coopetition tensions. Accordingly, their study develops the paradox integration thread of thinking through a scrutiny of various practices implemented to alleviate tensions. Fernandez & Chiambaretto (2016) suggest that the management of tensions related to information in coopetitive projects requires a combination of formal control mechanisms, i.e., information criticality, and informal control mechanisms, i.e., information appropriation, both of which are designed to foster the success of a common project while limiting the risk of opportunism (Das & Teng, 2001).

At the network level, both coopetitive and management accounting insist on the role of formal contract and informal social mechanisms, such as trust, shared norms, implicit sanctions, and symbolic communication (Caglio & Ditillo, 2008; Dekker, 2016; Peng & Bourne, 2009). These mechanisms lead to increased cognitive salience of competitors as well as to mutual coordination. Indeed, formal contracts, which are often incomplete, are performed with other mechanisms, such as informal social control (Anderson et al., 2014). Informal self-enforcing agreements between firms, i.e., relational contracts, rely on a range of social and other relationship-based control mechanisms and are sustained by the expected value of the future relationship (Baker et al., 2002).

More specifically, a network, because of its lack of central authority, exercises control through the installation of a governance board that is characterized by joint authority, monitoring, and decision making (Dekker, 2004). This form of hierarchy, however, results in decision making and conflict resolution being subject to inter-firm communications and negotiations. In this sense, the design and implementation of management control is also subject to negotiation and approval by partners’ executives. The management accounting resulting from these negotiations is a mix of mechanisms and practices that are meant to serve the interests of the various partners rather than those of a single firm. Another difference between the inter-firm and the intra-firm settings is the role of arbitrators in the event of relationship failures or conflicts. This role also results from the absence of a complete hierarchy, and thus adds other parties to the relationship that are not present within the firm (Dekker, 2016).

Although both the coopetitive and the management accounting literature propose tools to manage coopetitive tensions at the network level, there remains a lack of a comprehensive theoretical framework.

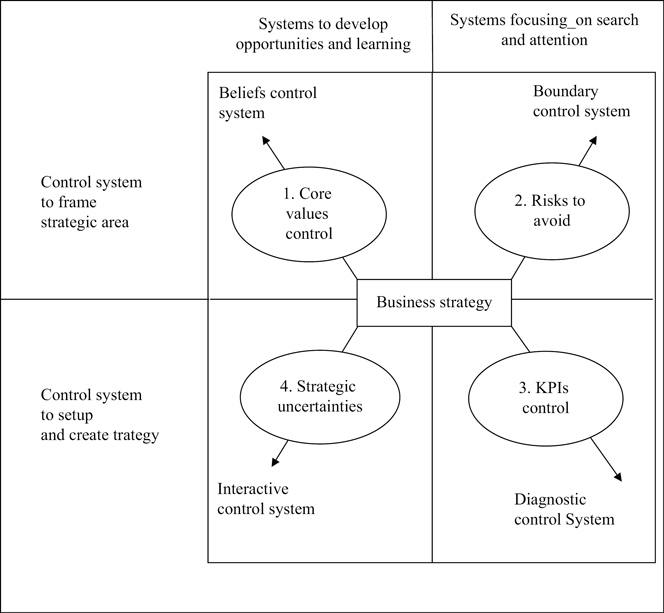

Simons (1995) developed a theoretical framework that aims to frame a strategic area, establish and create a strategy, develop opportunities and focus on managing multiple tensions. This framework links business strategy, including the alliance strategy, and system control management to balance tensions (Figure 34.2). Simons’ framework includes four managerial control levers: (1) beliefs systems; (2) boundary systems; (3) diagnostic control systems; and (4) interactive control systems.

Cooperative strategic area

The beliefs control system is “the explicit set of organizational definitions that senior managers communicate formally and reinforce systematically to provide basic values, purpose, and direction.” This formal communication style provides basic shared values and direction for inter-coopetitive networks and relies on relational contracting to establish credible commitments among firms (Grafton & Mundy, 2016). This system is presented as behavioral control, social control, and informal control in Table 34.3. Specifically, the Group Central Institution as a network representative organization makes extensive use of shared values, group norms, meetings, informal gatherings, partner selection, restricted access, and the threat of collective sanctions to manage various relational and decision risks associated with coopetitive activities. Dependence and repeated exchanges between partners can reduce opportunistic behaviors because any firm that operates against the norms of the group potentially faces the threat of being excluded from other collaborative activities critical to their survival as an independent bank.

The boundary control system is defined as “the acceptable domain of strategic activity for organizational participants, through communicating, implementing and enforcing codes of business conduct.” As such, it outlines the acceptable domain of the banking business model, including credit risk and security, for inter-coopetitive networks and is presented in Table 34.3 as an inter-organizational management controls systems design. Concretely, the Group Central Institution oversees the global coopetitive activities of the two networks through the implementation of a three- to five-year strategic plan voted on by both banking networks and the strengthening of internal control. As part of its supervisory role, the Group Central Institution has the power to dismiss and replace the top managers from among the network members (e.g., regional banks) if they fail to comply with its directives or banking regulations. A strong internal merger has occurred in recent years within the regional banks of these networks, either for economy of scale or in the event that they were not sufficiently profitable.

Cooperative strategy

We propose to set up and create cooperative strategy through diagnostic and interactive control systems. The diagnostic control system is designed “to ensure the implementation of intended strategies and the achievement of planned outcomes, allowing the managers to monitor the activity of employees or partner’s organizations through the review of critical performance coopetitive variables” and is represented by the performance measurement systems and process controls in Table 34.3. The system includes budget and reporting and allows feedback of coopetitive networks (Table 34.4).

| Inter-network Coopetition Activities | Coopetitive Tensions | Control Mechanisms & Tools | Simons’ Levers of Control |

Common information system management |

Tension created in IT activities management |

Cost allocation and annual budget |

Diagnostic and interactive control system |

Tension created by knowledge sharing |

Specific governance structures through role and task sharing |

Diagnostic and interactive control system | |

Regulatory risk management |

Tension in the management of mutual funds and the joint subsidiaries taking more financial risks |

Five-year strategic plan; internal audit control |

Boundary control system |

Tensions created by comparing IT performance and IT risks between regional banks |

Global network consolidated reporting/IT—internal audit control |

Diagnostic control system | |

Networks representation activities |

Representation equilibrium between cooperative values and shareholder values |

Decision system (equity, interdependence); democracy; solidarity |

Beliefs control system; interactive control system |

The interactive control system is based on “the personal involvement and interest of managers in the critical elements of strategy design and implementation, creating an ongoing dialogue with subordinates and partners, and actively finding of best solutions for the identified problems” and controls inter-coopetitive networks with the use of formal tools in an interactive way. For example, the implementation of cost allocation control systems in the annual budget is managed via an interactive control system through the informal internal networks that are inter-related and embedded one in another (Seran et al., 2016). This control is effective because, on the one hand, cooperative banking networks are characterized by an information asymmetry between member-owners (shareholders) and managers that is much stronger than in conventional banking networks. The limitation of the ownership rights of the members and, in particular, the weak correlation between dividend and bank’s performances, weakens their incentive to control the managers. On the other hand, the dilution of control and the weak link between capital ownership and the composition of management bodies reinforce discretionary managerial power and organizational inefficiency that can include overstaffing, lack of penalties for incompetence, lack of motivation to reduce operating costs and improve productivity, excessive remuneration, existence of free cash flows and creation of high reserves (Akella & Greenbaum, 1988; Mayers & Smith, 1994). However, the discretionary power of regional banking managers is limited by the risk of being closed or merged by a collective decision and by the existence of an internal labor market in which managers must preserve their reputations (informal control system). These informational asymmetries favor the development of informal interactive control through the networks of senior executives.

Conclusions: Contributions and research agenda

Combining both coopetition and management accounting literatures is necessary to build an integrative management accounting framework for network coopetition. Simons (1995, 1999) posits that effective control is achieved by integrating the four levers of control, since “the power of these levers in implementing strategy does not lie in how each is used alone, but rather in how they complement each other when used together. The interplay of positive and negative forces creates a dynamic tension.” Simons also states that beliefs and interactive controls create positive energy and that boundary and diagnostic controls create negative energy as they assess planned objectives. From our case study, this equilibrium produced good results in terms of cost and income synergies according to our financial data analysis from the beginning of the alliance to 2013. Moreover, financial performance also exhibited good results and risks were reduced. The performances were driven by boundary and diagnostic control systems, i.e., negative energy. However, these systems have some limits linked to the specificities of cooperative banks, which sometimes make them ineffective. Hence, they are completed with beliefs control systems and interactive control systems, i.e., positive energy. A perfect example of the interaction of beliefs and interactive control systems was demonstrated in the cooperative banking case presented above. Whereas management accounting literature contributes by advancing knowledge on the coopetition phenomenon by providing structured coopetitive management tools, management accounting is perceived as coopetitive strategic alignment by incorporating the tools as concrete actions and performance measurements. Concretely, the integrative framework proposed (Figure 34.3) as a management tool facilitates the achievement of the following four objectives: (1) frame the coopetitive strategy area using the definition of shared value to obtain commitment to the coopetitive purpose, i.e., belief system, and to design the network governance and risk management to stake out the territory, i.e., boundary system; (2) establish a strategy based on the performance measurement, i.e., diagnostic system, and create competition through the positioning of the uncertainty environment, i.e., interactive system; (3) focus on research based on the definition of risk domain; and (4) develop new opportunities and learning within the coopetitive network.

Conversely, coopetition enriches management accounting literature by developing emerging literature on the boundaries between intra-firm and inter-firm management accounting (Dekker, 2016) and on the horizontal relationships network among competitors. Moreover, coopetitive tensions appearing during the time span of the inter-firm management accounting literature consume the whole-time span of coopetition studies (Czakon et al., 2014). However, as these tensions remain under-examined in management accounting literature (Grafton & Mundy, 2016), the topic provides interesting opportunities for future studies.

First, the new institutionalist theory can be a paradoxical approach for coopetitive networks as their members may belong to a hybrid organization or a meta-organization that has different institutional logics.

Second, network-level or industry-level empirical studies are still few. This level of analysis takes into account market structure contingencies, ecosystem competition, and collective growth strategies. Tensions arising under these conditions are stronger in a coopetitive context because each individual defends his/her parent firm. While partner companies often agree on a collaborative strategy to be pursued jointly, they are also likely to pursue individual strategies that relate to their individual objectives. In particular, when a firm’s private aspirations diverge from (or conflict with) the collaborative strategy, it results in competing tensions and greater complexity for alliance staff who are expected to act in the best interests of both parties. In fact, the role of the management control system is to balance the interests and decisions of boundary spanners with respect to the different objectives and strategies being pursued (Dekker, 2016). To investigate management control in the boundary organization through the boundary spanner, the boundary object concept may facilitate understanding how boundary spanner profiles and mechanisms must be mobilized for successful coopetition and why coopetition stabilizes over time.

Notes

1Acknowledgments: we thank the IRCCF of Montréal (Canada) and the BPCE (France), particularly Mr Séran, Mr Grafouillère, and Mr Viguié, for their valuable contributions, which helped us to improve our research significantly. All errors and shortcomings remain the authors’ responsibility.

2Banque Populaire Caisse d’Epargne.

References

Akella, S. R. & Greenbaum, S. I. (1988). Savings and Loan ownership structure and expense-preference. Journal of Banking and Finance, 12, 419–437.

Anderson, S. W., Christ, M. H., Dekker, H. C., & Sedatole, K. L. (2014). The use of management controls to mitigate risk in strategic alliances: Field and survey evidence. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(1).

Baker, G., Gibbons, R., & Murphy, K. J. (2002). Relational contracts and the theory of the firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 39–84.

Baum, J. A. C. & Korn, H. J. (1996). Competitive dynamics of interfirm rivalry. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 255–291.

Bengtsson, M. & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition—Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188.

Bettis, R. A. & Hitt, M. A. (1995). The new competitive landscape. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 7–19.

Bonel, E. & Rocco, E. (2007). Coopeting to survive; surviving coopetition. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 70–96.

Bonomo, G., Schneider, S., Turchetti, P., & Vettori, M. (2016). SREP: How Europe’s banks can adapt to the new risk-based supervisory playbook. New York: McKinsey & Company.

Caglio, A. & Ditillo, A. (2008). A review and discussion of management control in inter-firm relationships: Achievements and future directions. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33, 865–898.

Cassiman, B., Di Guardo, M. C., & Valentini, G. (2009). Organising R&D projects to profit from innovation: Insights from co-opetition. Long Range Planning, 42, 216–233.

Chen, M.-J. (2008). Reconceptualizing the competition-cooperation relationship: a transparadox perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20, 1–19.

Czakon, W., Mucha-Kus, K., & Rogalski, M. (2014). Coopetition research landscape – A systematic literature review 1997–2010. Journal of Economics & Management, 17, 122–150.

Das, T. K. & Teng, B.-S. (2001). A risk perception model of alliance structuring. Journal of International Management, 7, 1–29.

de Man, A.-P. & Roijakkers, N. (2009). Alliance governance: Balancing control and trust in dealing with risk. Long Range Planning, 42(1).

Dekker, H. C. (2004). Control of inter-organizational relationships: evidence on appropriation concerns and coordination requirements. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29, 27–49.

Dekker, H. C. (2016). On the boundaries between intrafirm and interfirm management accounting research. Management Accounting Research, 31, 86–99.

EACB. (2017). Co-operative Banks: Definition, Characteristics and Key figures – EACB. European Association of Co-operative Banks.

Faems, D., Janssens, M., Madhok, A., & Van Looy, B. (2008). Toward an integrative perspective on alliance governance: Connecting contract design, trust dynamics, and contract application. Academy of Management Journal, 51(6),

Fernandez, A.-S. & Chiambaretto, P. (2016). Managing tensions related to information in coopetition. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 66–76.

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 222–235.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Madhavan, R. (2001). Cooperative networks and competitive dynamics: A structural embeddedness perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 431–445.

Gnyawali, D. R., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2012). Contradiction, dualities and tensions in cooperation and competition: A capability based framework. In Annual meeting of the Academy of Management (AoM). Boston, MA.

Gnyawali, D. R. & Park, B. J. (2009). Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330.

Grafton, J. & Mundy, J. (2016). Relational contracting and the myth of trust: control in a co-opetitive setting. Management Accounting Research, in press.

Ketchen Jr., D. J., Snow, C. C., & Hoover, V. L. (2004). Research on competitive dynamics: recent accomplishments and future challenges. Journal of Management, 30(6), 779–804.

Korn, H. J. & Baum, J. A. C. (1999). Chance, imitative, and strategic antecedents to multimarket contact. Academy of Management Journal, 42(2), 171–193.

Luo, X., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pan, X. (2006). Cross-functional “coopetition”: The simultaneous role of cooperation and competition within firms. Journal of Marketing, 70, 67–80.

Luo, Y. (2007). A coopetition perspective of global competition. Journal of World Business, 42, 129–144.

Mayers, D. & Smith, C. W. (1994). Managerial discretion, regulation, and stock insurer ownership structure. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 61(4), 638–655.

Moody. (2016). Company Profile: BPCE. Moody’s Investors Service.

Mouritsen, J. & Thrane, S. (2006). Accounting, network complementarities and the development of inter-organisational relations. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31, 241–275.

Peng, T.-J. A. & Bourne, M. (2009). The coexistence of competition and cooperation between networks: Implications from two Taiwanese healthcare networks. British Journal of Management, 20, 377–400.

Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198.

Seran, T., Pellegrin-Boucher, E., & Gurau, C. (2016). The management of coopetitive tensions within multi-unit organizations. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 31–41.

Simons, R. (1995). Control in an age of empowerment. Harvard Business Review, 73 (March–April), 80–88.

Simons, R. (1999). How risky is your company? Harvard Business Review, 77, 85–95.

van der Meer-Kooistra, J. & Scapens, R. W. (2008). The governance of lateral relations between and within organisations. Management Accounting Research, 19, 365–384.