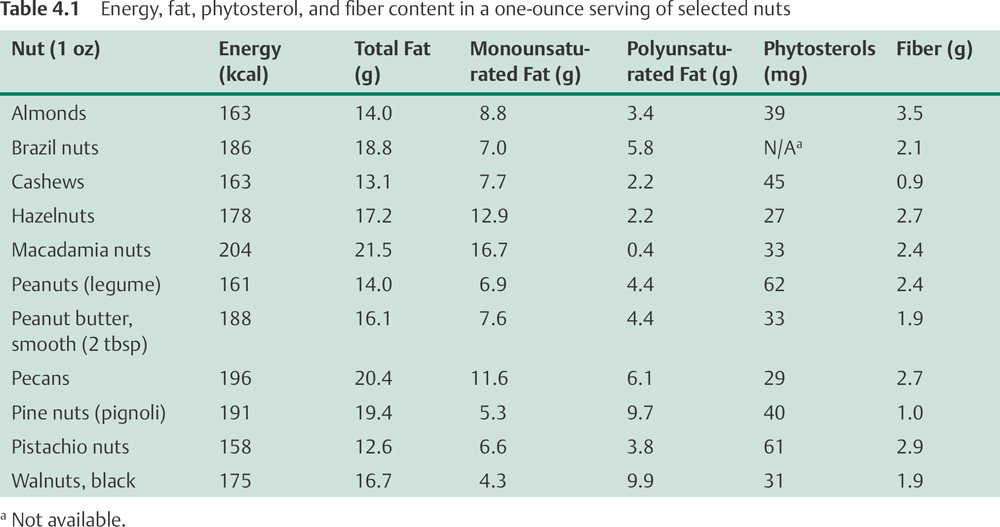

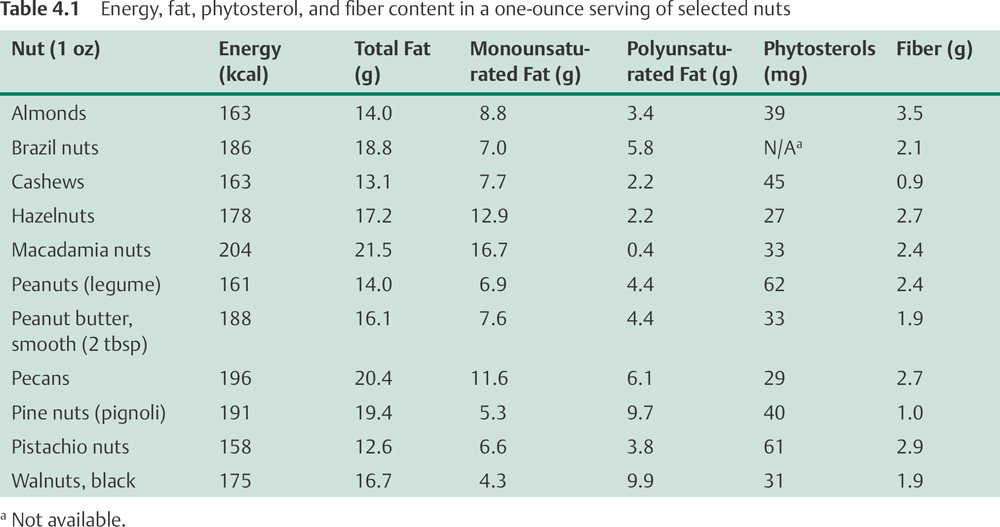

In the not too distant past, nuts were considered unhealthy because of their relatively high fat content. In contrast, recent research suggests that regular nut consumption is an important part of a healthful diet.1 Although the fat content of nuts is relatively high (14–19 g/oz or 49–67%), most of the fats in nuts are the healthier, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats (see Table 4.1)2. The term “nuts” includes almonds, Brazil nuts, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pistachios, walnuts, and peanuts. Despite their name, peanuts are actually legumes like peas and beans. However, they are nutritionally similar to tree nuts and have some of the same beneficial properties.

In large prospective cohort studies, regular nut consumption has been consistently associated with significant reductions in the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).3 One of the first studies to observe a protective effect of nut consumption was the Adventist Health Study, which followed more than 30 000 Seventh Day Adventists over 12 years.4 In general, the dietary and lifestyle habits of Seventh Day Adventists are closer to those recommended for cardiovascular disease prevention than those of average Americans. Few of those who participated in the Adventist Health Study smoked, and most consumed a diet lower in saturated fat than the average American. In this healthy group, those who consumed nuts at least five times weekly had a 48% lower risk of death from CHD and a 51% lower risk of a nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) compared with those who consumed nuts less than once weekly.4 In Seventh Day Adventists who were older than 83 years of age, those who ate nuts at least five times weekly had a risk of death from CHD that was 39% lower than those who consumed nuts less than once weekly.5 A smaller prospective study of more than 3 000 black men and women reported similar results.6 Those who consumed nuts at least five times weekly had a risk of death from CHD that was 44% lower than those who consumed nuts less than once weekly.6

The cardioprotective effects of nuts are not limited to Seventh Day Adventists. In a 14-year study of more than 86 000 women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), those who consumed more than 5 oz of nuts weekly had a risk of CHD that was 35% lower than those who ate less than 1 oz of nuts monthly.7 Similar decreases were observed for the risk of nonfatal MI and death from CHD. More recently, a 17-year study of more than 21 000 male physicians found that those who consumed nuts at least twice weekly had a risk of sudden cardiac death that was 53% lower than those who rarely or never consumed nuts, although there was no significant decrease in the risk of nonfatal MI or nonsudden CHD death.8 A follow-up analysis in this cohort of male physicians found that nut consumption was not associated with incident heart failure.9 The Iowa Women's Health Study, which followed more than 30 000 postmenopausal women for 12 years, is the only published prospective study that did not observe a significant inverse association between nut consumption and CHD mortality, although a slight but significant decrease in all-cause mortality was observed in those who consumed nuts twice weekly.10 Overall, the results of most prospective cohort studies suggest that regular nut consumption is associated with a substantial decrease in the risk of death related to CHD. In fact, a recent pooled analysis of four of the US epidemiological studies mentioned above found those with the highest intake of nuts (around five times per week) had a 35% lower risk of CHD.11

Results of controlled clinical trials indicate that at least part of the cardioprotective effect of nuts is derived from beneficial effects on serum total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentrations.3 At least 18 controlled clinical trials have found that adding nuts to a diet that is low in saturated fat results in significantly reductions in serum total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol concentrations in people with normal or elevated serum cholesterol. These effects have been observed for almonds,12–15 hazelnuts,16 macadamia nuts,17–19 peanuts,20,21 pecans,22 pistachio nuts,23,24 and walnuts.25–30 More recently, a cross-sectional study found that frequent nut and seed consumption was associated with lower serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers in a multi-ethnic population.31 Although the evidence is circumstantial, these findings suggest that compounds in nuts may lower the risk of cardiovascular disease by decreasing inflammation.

Substituting dietary saturated fats with polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats like those found in nuts can decrease serum total and LDL cholesterol concentrations.3 However, in some clinical trials, the cholesterol-lowering effect of nut consumption was greater than would be predicted from the polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat content of the nuts, suggesting there may be other protective factors in nuts.32 Other bioactive compounds in nuts that may contribute to their cholesterol-lowering effects include fiber (Chapter 16) and phytosterols (Chapter 18).33 See Table 4.1 for the unsaturated fat, fiber, and phytosterol content of selected nuts. Walnuts are especially rich in α-linolenic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid with several cardioprotective effects, including the prevention of cardiac arrhythmias that may lead to sudden cardiac death (Chapter 20). Other nutrients that may contribute to the cardioprotective effects of nuts include folate, vitamin E, and potassium.3,33–35 The US Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged the emerging evidence for a relationship between nut consumption and cardiovascular disease risk, by approving the following qualified health claim for nuts36: “Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that eating 1.5 oz/day of most nuts as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease.”

Recent results from the NHS suggest that nut and peanut butter consumption may be inversely associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) in women.37 In this cohort of more than 86 000 women followed over 16 years, those who consumed an ounce of nuts at least five times weekly had a risk of developing type 2 DM that was 27% lower than in those who rarely or never consumed nuts. Similarly those who consumed peanut butter at least five times weekly had a risk of developing type 2 DM that was 21% lower than in those who rarely or never consumed peanut butter. While these findings require confirmation in other studies, they provide additional evidence that nuts can be a component of a healthful diet. Compounds in nuts that could contribute to the observed decrease in type 2 DM include unsaturated fats, fiber, and magnesium.

A major concern is that increased consumption of nuts may cause weight gain and obesity. However, several cross-sectional analyses of large cohort studies, including the Adventist Health Study5 and the NHS,7 have shown that individuals who consume nuts regularly tend to weigh less than those who rarely consume them. Recently, a 28-month prospective study conducted in Spain found that participants who consumed higher amount of nuts had lower risk of weight gain than those who rarely ate nuts.38 A similar association was observed in the NHS II.39 These epidemiologic data indicate that in free-living subjects, higher nut consumption does not cause greater weight gain; rather, incorporating nuts into diets may be beneficial for weight control. It is possible that higher amounts of protein and fiber in nuts enhance satiety and suppress hunger.

Allergies to peanuts and tree nuts (almonds, cashews, hazelnuts, pecans, pistachios, and walnuts) are among the most common food allergies, affecting at least 1% of the US population.40 Although all food allergies have the potential to induce severe reactions, peanuts and tree nuts are among the foods most commonly associated with anaphylaxis, a life-threatening allergic reaction.41 People with severe peanut or tree nut allergies need to take special precautions to avoid inadvertently consuming peanuts or tree nuts, by checking labels and avoiding unlabeled snacks, candies, and desserts.

Brazil nuts grown in areas of Brazil with selenium-rich soil may provide more than 100 µg of selenium in one nut, while those grown in selenium-poor soil may provide 10 times less.42

Regular nut consumption, equivalent to an ounce of nuts five times weekly, has been consistently associated with significant reductions in CHD risk in epidemiological studies. Consuming 1–2 oz of nuts daily as part of a diet that is low in saturated fat has been found to lower serum total and LDL cholesterol in several controlled clinical trials. Since an ounce of most nuts provides at least 669 kJ (160 kcal), simply adding an ounce of nuts daily to one's habitual diet without eliminating other foods may result in weight gain. Substituting unsalted nuts for other less healthful snacks, or for meat in main dishes, are two ways to make nuts part of a healthful diet.

• Nuts are good sources of fiber, phytosterols, and unsaturated fat.

• The results of most prospective cohort studies suggest that regular nut consumption (equivalent to 1 oz at least five times weekly) is associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

• One prospective cohort study has found that regular nut consumption is associated with significantly lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

• Most prospective studies have shown that people who consume nuts regularly weigh less than those who rarely consume nuts. Nonetheless, since an ounce of most nuts provides approximately 669 kJ (160 kcal), substituting nuts for other less healthful snacks is a good strategy for avoiding weight gain when increasing nut intake.

1. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ. Nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a review of epidemiologic evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep 1999;1(3):204–209

2. Kris-Etherton PM, Yu-Poth S, Sabaté J, Ratcliffe HE, Zhao G, Etherton TD. Nuts and their bioactive constituents: effects on serum lipids and other factors that affect disease risk. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 70(3, Suppl):504S–511S

3. Kris-Etherton PM, Zhao G, Binkoski AE, Coval SM, Etherton TD. The effects of nuts on coronary heart disease risk. Nutr Rev 2001;59(4):103–111

4. Fraser GE, Sabaté J, Beeson WL, Strahan TM. A possible protective effect of nut consumption on risk of coronary heart disease. The Adventist Health Study. Arch Intern Med 1992;152(7):1416–1424

5. Fraser GE, Shavlik DJ. Risk factors for all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality in the oldest-old. The Adventist Health Study. Arch Intern Med 1997;157(19):2249–2258

6. Fraser GE, Sumbureru D, Pribis P, Neil RL, Frankson MA. Association among health habits, risk factors, and all-cause mortality in a black California population. Epidemiology 1997;8(2):168–174

7. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 1998;317 (7169):1341–1345

8. Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Willett WC, Manson JE. Nut consumption and decreased risk of sudden cardiac death in the Physicians’ Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(12):1382–1387

9. Djoussé L, Rudich T, Gaziano JM. Nut consumption and risk of heart failure in the Physicians’ Health Study I. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88(4):930–933

10. Ellsworth JL, Kushi LH, Folsom AR. Frequent nut in-take and risk of death from coronary heart disease and all causes in postmenopausal women: the Iowa Women's Health Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2001;11(6):372–377

11. Kris-Etherton PM, Hu FB, Ros E, Sabaté J. The role of tree nuts and peanuts in the prevention of coronary heart disease: multiple potential mechanisms. J Nutr 2008;138(9):1746S–1751S

12. Hyson DA, Schneeman BO, Davis PA. Almonds and almond oil have similar effects on plasma lipids and LDL oxidation in healthy men and women. J Nutr 2002;132(4):703–707

13. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al. Dose response of almonds on coronary heart disease risk factors: blood lipids, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, lipoprotein (a), homocysteine, and pulmonary nitric oxide: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Circulation 2002;106(11):1327–1332

14. Sabaté J, Haddad E, Tanzman JS, Jambazian P, Rajaram S. Serum lipid response to the graduated enrichment of a Step I diet with almonds: a randomized feeding trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77(6):1379–1384

15. Spiller GA, Jenkins DA, Bosello O, Gates JE, Cragen LN, Bruce B. Nuts and plasma lipids: an almond-based diet lowers LDL-C while preserving HDL-C. J Am Coll Nutr 1998;17(3):285–290

16. Durak I, Köksal I, Kaçmaz M, Büyükkoçak S, Cimen BM, Oztürk HS. Hazelnut supplementation enhances plasma antioxidant potential and lowers plasma cholesterol levels. Clin Chim Acta 1999;284(1):113–115

17. Curb JD, Wergowske G, Dobbs JC, Abbott RD, Huang B. Serum lipid effects of a high-monounsaturated fat diet based on macadamia nuts. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(8):1154–1158

18. Garg ML, Blake RJ, Wills RB. Macadamia nut consumption lowers plasma total and LDL cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic men. J Nutr 2003; 133(4):1060–1063

19. Griel AE, Cao Y, Bagshaw DD, Cifelli AM, Holub B, Kris-Etherton PM. A macadamia nut-rich diet reduces total and LDL-cholesterol in mildly hypercholesterolemic men and women. J Nutr 2008;138(4):761–767

20. Kris-Etherton PM, Pearson TA, Wan Y, et al. High-monounsaturated fatty acid diets lower both plasma cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70(6):1009–1015

21. O'Byrne DJ, Knauft DA, Shireman RB. Low fat-monounsaturated rich diets containing high-oleic peanuts improve serum lipoprotein profiles. Lipids 1997; 32(7):687–695

22. Morgan WA, Clayshulte BJ. Pecans lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in people with normal lipid levels. J Am Diet Assoc 2000;100(3):312–318

23. Edwards K, Kwaw I, Matud J, Kurtz I. Effect of pistachio nuts on serum lipid levels in patients with moderate hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Nutr 1999; 18(3):229–232

24. Sheridan MJ, Cooper JN, Erario M, Cheifetz CE. Pistachio nut consumption and serum lipid levels. J Am Coll Nutr 2007;26(2):141–148

25. Abbey M, Noakes M, Belling GB, Nestel PJ. Partial replacement of saturated fatty acids with almonds or walnuts lowers total plasma cholesterol and low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59(5):995–999

26. Almario RU, Vonghavaravat V, Wong R, Kasim-Karakas SE. Effects of walnut consumption on plasma fatty acids and lipoproteins in combined hyperlipidemia. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74(1):72–79

27. Chisholm A, Mann J, Skeaff M, et al. A diet rich in walnuts favourably influences plasma fatty acid profile in moderately hyperlipidaemic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 1998;52(1):12–16

28. Morgan JM, Horton K, Reese D, Carey C, Walker K, Capuzzi DM. Effects of walnut consumption as part of a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet on serum cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2002;72(5):341–347

29. Sabaté J, Fraser GE, Burke K, Knutsen SF, Bennett H, Lindsted KD. Effects of walnuts on serum lipid levels and blood pressure in normal men. N Engl J Med 1993;328(9):603–607

30. Zambón D, Sabaté J, Muñoz S, et al. Substituting walnuts for monounsaturated fat improves the serum lipid profile of hypercholesterolemic men and women. A randomized crossover trial. Ann Intern Med 2000;132(7):538–546

31. Jiang R, Jacobs DR Jr, Mayer-Davis E, et al. Nut and seed consumption and inflammatory markers in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163(3):222–231

32. Coulston AM. Do Nuts Have a Place in a Healthful Diet? Nutr Today 2003;38(3):95–99

33. Segura R, Javierre C, Lizarraga MA, Ros E. Other relevant components of nuts: phytosterols, folate and minerals. Br J Nutr 2006;96(Suppl 2):S36–S44

34. Willett WC. Eat, Drink, and be Healthy: The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healthy Eating. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2001.

35. Coates AM, Howe PR. Edible nuts and metabolic health. Curr Opin Lipidol 2007;18(1):25–30

36. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Nutrition. Summary of Qualified Health Claims Subject to Enforcement Discretion. 2003. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/LabelClaims/QualifiedHealthClaims/ucm073992.htm#nuts. Accessed May 1, 2012

37. Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Liu S, Willett WC, Hu FB. Nut and peanut butter consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA 2002;288(20):2554–2560

38. Bes-Rastrollo M, Sabaté J, Gómez-Gracia E, Alonso A, Martínez JA, Martínez-González MA. Nut consumption and weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(1):107–116

39. Bes-Rastrollo M, Wedick NM, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson L, Hu FB. Prospective study of nut consumption, long-term weight change, and obesity risk in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(6):1913–1919

40. Sicherer SH, Muñoz-Furlong A, Burks AW, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the US determined by a random digit dial telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103(4):559–562

41. Al-Muhsen S, Clarke AE, Kagan RS. Peanut allergy: an overview. CMAJ 2003;168(10):1279–1285

42. Chang JC, Gutenmann WH, Reid CM, Lisk DJ. Selenium content of Brazil nuts from two geographic locations in Brazil. Chemosphere 1995;30(4):801–802