14.2 Painful Syndromes of the Head and Neck

14.3 Painful Syndromes of the Face

14.4 Painful Shoulder–Arm Syndromes

14.2 Painful Syndromes of the Head and Neck

14.3 Painful Syndromes of the Face

14.4 Painful Shoulder–Arm Syndromes

The Same, Only Different

The patient, a 32-year-old nurse, had suffered from recurrent headaches every few months since childhood. These were generally of a pulsating quality, very intense, and limited to one side of the head, usually the right side. The pain was most intense behind the eye, accompanied by a strong sensation of pressure. Each attack lasted 6 to 8 hours; during the attacks, she was also very sensitive to light and noise. Whenever possible, she withdrew to a quiet, dark room, avoided all activity, and waited for the pain to go away. Her mother had suffered from similar headaches.

She had a severe headache again one Easter Sunday; this surprised her, because the last attack had been only 1 week before. This time, the pain came on not gradually, but suddenly, “out of a clear blue sky,” and was much more intense than usual. The pain was “all over my head,” and she felt as if her head were about to explode. She went to her room and lay down. Five minutes later, she became nauseated and vomited repeatedly. Over the next half hour, she became progressively confused. Her husband called the emergency medical services.

This patient’s prior usual headaches were typical migraine headaches, but the Easter Sunday episode was of another kind entirely. A headache of sudden onset and extreme intensity is characteristic of an intracranial hemorrhage. The most common cause is a ruptured aneurysm of an artery at the base of the brain, causing arterial blood to enter the subarachnoid space (subarachnoid hemorrhage, SAH).

The emergency physician on the scene examined her and found meningismus (a clinical manifestation of leptomeningeal irritation, generally caused either by extravasated blood or by an infectious/inflammatory process). She was somnolent, but responsive and cooperative, and had no other neurologic deficits. Suspecting SAH, the emergency physician had her transported immediately to the emergency room of a tertiary-care hospital for neurosurgical evaluation. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the diagnosis of SAH and revealed a probable ruptured aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery as the cause. This was then confirmed by angiography, whereupon the aneurysm was obliterated with intravascular detachable coils in an interventional neuroradiologic procedure.

Headache is a common symptom in everyday clinical practice and has many causes. Primary diseases of the nervous system often cause intense or unbearable pain as a prominent or even sole manifestation. For this reason, neurologists are often consulted to help in the evaluation of patients with pain. The nervous system plays a key role in the transmission and processing of nociceptive impulses and in the perception of pain.

Key Point

Many conditions whose most prominent, or sole, symptom is pain lie within the neurologist’s field of expertise. In this chapter, we will discuss painful syndromes by location: headache, facial pain, shoulder–arm pain, pain in the trunk, and pain in the lower limb. The differential diagnosis of a painful syndrome cannot be restricted to neurologic conditions and must always include diseases of nonneurologic origin.

Pain is a type of unpleasant sensation. In terms of pathophysiology, it arises when specialized sensory end organs are excited by certain mechanical, thermal, or chemical stimuli of a potentially damaging (“noxious”) nature. The pain-related (“nociceptive”) impulses are conducted centrally, mainly by way of thin, poorly myelinated fibers, through the posterior root and into the spinal cord. The nociceptive fibers cross the midline in the spinal cord at their level of entry and then ascend in the spinothalamic tract to the thalamus and onward to higher centers in the brain, which enable pain to be consciously felt (see section ▶ 5.3 and ▶ Fig. 5.2). Biochemical factors also play an important role in pain perception. In the periphery, the intensity of pain is increased by a variety of biogenic amines, for example, substance P. In the central nervous system, the intensity of pain is modulated by the production of opioid substances in certain areas of the brain. Finally, psychological factors—relating to the patient’s personality as well as the sociocultural environment—affect the manner in which pain is experienced and processed.

Many painful syndromes have their origin in the nervous system; many others, in which there is no evident neural dysfunction (e.g., most kinds of headache), are nonetheless traditionally evaluated and treated by neurologists. These facts justify the inclusion of painful syndromes in a textbook of neurology. It should be emphasized, however, that the physician confronted by the symptom “pain” should not approach it from the narrow viewpoint of any particular specialty, but must rather apply the full range of general medical knowledge.

This purpose is best served, first, by the taking of a systematic and directed pain history. The main elements of the pain history are listed in ▶ Table 14.1. Further specific questions will need to be asked depending on the nature and location of pain in the particular case, and ancillary diagnostic tests may be needed as well.

|

Aspect |

Questions |

|

Where is the pain? |

|

|

How long has it been present? |

|

|

Continuous or intermittent? |

|

|

Quality? |

|

|

Intensity? |

|

|

Precipitating and/or aggravating factors? |

|

|

Alleviating factors? |

|

|

How severely is the patient impaired by the pain? |

|

|

Current complaints other than pain? |

|

In the remainder of this chapter, we will discuss various major painful syndromes, classifying them by location.

Key Point

Headache can be either idiopathic or symptomatic. The most common idiopathic or “primary” types of headache are tension-type headache, migraine, and cluster headache. While migraine and cluster headache are typified by highly characteristic, mostly unilateral attacks of pain, tension-type headache more commonly assumes the form of a diffuse, continuous headache of lesser intensity. Symptomatic (“secondary”) headaches are, by definition, a manifestation of some other underlying condition. The possible causes include many neurologic diseases, as well as diseases of the eyes, teeth, jaw, ear, nose, and throat, and many general medical conditions. Spondylogenic headache is caused by pathologic processes in the cervical spine. A third group of conditions characterized by head and neck pain is the neuralgias, the most common of which is trigeminal neuralgia.

Headache can also include a variably significant component of facial pain—a typical example is cluster headache, which is felt mainly in the forehead, eye, and temple. Headache and facial pain cannot be cleanly separated from each other and are therefore considered under one heading in the International Headache Society (IHS) classification (see later and also ▶ Table 14.2). It is nonetheless useful, for clarity, to distinguish syndromes in which the pain is mainly in the head from those in which it is mainly in the face. Headache will accordingly be discussed in this section and facial pain in the next.

|

Category |

Entities |

|

Primary headaches |

|

|

Secondary headaches |

|

|

Cranial neuralgias, central and primary facial pain, and other headaches |

|

|

Note: Further subcategories and related information can be found on the Web site of the International Headache Society (http://ihs-classification.org). |

|

The classification of headache syndromes proposed by the IHS has won general acceptance. The major categories of headache in this system are listed in ▶ Table 14.2. The IHS has established obligatory diagnostic criteria for each type of headache. This highly precise approach to headache syndromes is most useful in clinical research, where the findings of different teams of investigators must be compared with each other, but it is also highly practical for routine clinical use.

Practical Tip

The potential benefit of any proposed treatment of a particular type of headache can only be assessed reliably when it is clear that all of the research teams reporting on it are, in fact, treating the same condition. Standardization is the main virtue of the IHS criteria.

For the beginning student of neurology, however, it is more useful to gain a descriptive overview of the more common, “classic” types of headache ( ▶ Table 14.3). In particular, he or she should learn to distinguish the common primary types of headache, that is, those not due to any demonstrable structural lesion in the head, from secondary types. The latter are caused by organic disease of the cranial vessels or other structures in the head, or have other organic causes (e.g., infection, disorders of homeostasis). Ninety percent of all cases of headache are of the primary type.

|

Headache type |

Site of pain |

Duration of episodes |

Frequency of episodes |

Phenomena during episodes |

Intensity; other remarks |

|

Tension-type headache |

Diffuse, bilateral |

Hours to days |

Rare to several times per week |

No unusual phenomena |

|

|

Migraine |

Two-thirds of attacks are unilateral, one-third bilateral |

4–72 h |

Rare to several times per week |

Occasionally, Horner syndrome |

|

|

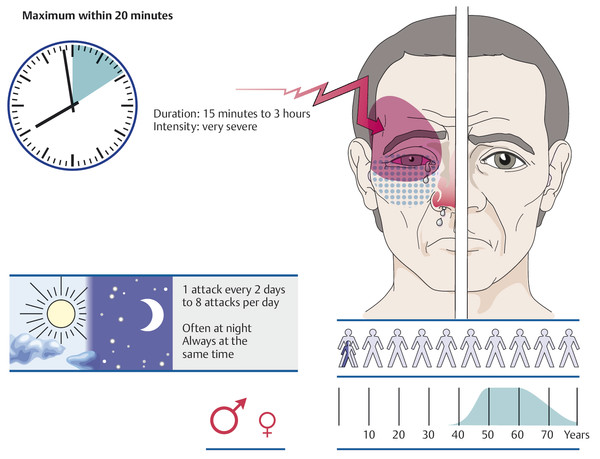

Cluster headache |

Periorbital, forehead, temple, maxilla |

15–180 min |

1–8/d |

Horner syndrome, periorbital erythema, conjunctival injection, lacrimation, rhinorrhea or stuffed nose |

|

|

Trigeminal neuralgia |

In the distribution of one of the three divisions of CN V (usually maxillary) |

Fraction of a second |

1 to 100 per day |

Painful contraction of the affected half of the face (tic douloureux) |

|

|

Secondary headache types |

Depends on etiology |

Usually continuous or long-lasting |

– |

Depends on etiology |

|

|

Abbreviation: CN, cranial nerve. |

|||||

Note

The patient who goes to the doctor because of headache is suffering from pain and, often, anxiety. He or she therefore can rightly expect the following:

To be taken seriously.

To be examined carefully.

To have the cause of the problem identified and clearly explained.

To be given effective treatment.

The physician must take the time needed to meet these expectations fully.

The clinical history is a vital step in the evaluation of headache. The systematic interview of the headache patient should address the following points:

Family history of headache?

How long have headaches been present?

Nature of headache:

Site?

Continuous or episodic?

Usual or unusual quality of pain?

Timing of onset?

Speed of development?

Character of pain?

Precipitating factors?

Duration of episodes?

Accompanying signs?

Frequency?

Headache-free intervals?

Impairment of activities at home and at work?

Drugs and other measures against headache:

Frequency?

Dose?

Effect?

Other symptoms besides headache:

ENT, ophthalmic, or dental disease?

Memory loss?

Neurologic/neuropsychological deficits?

Epileptic seizures?

General symptoms (fatigue, weight loss, circulatory problems, etc.)?

Personality and external circumstances:

Personality type?

Occupation?

Private life?

Conflict situations?

Alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, drugs of abuse?

Current medications?

A carefully elicited history usually leads to a fairly secure diagnosis. Nonetheless, the general physical examination and the neurologic examination should never be omitted, not least because they help the physician win the patient’s confidence—an important factor for the success of treatment. The examination should include the following:

General medical examination:

Cardiovascular system, especially blood pressure.

Renal function.

Signs of infection.

Signs of meningitis.

Signs of malignancy.

ENT diseases.

Eye diseases.

Dental diseases, jaw diseases.

Cervical spondylosis.

Neurologic examination, with particular attention to:

Meningismus.

Signs of intracranial hypertension.

Focal neurologic signs.

Cranial nerve deficits.

Mental status, with particular attention to:

Cognitive deficit.

Impairment of consciousness.

Current psychological conflicts.

Depression.

Neurotic personality traits.

Definition and frequency By definition, primary headache is not a symptom or consequence of any other disease—the pain itself is the disease. About 60 to 70% of people suffer from headache or facial pain at some time in their lives, but only about 15% seek medical attention. Of people with headaches, 90% have one of the two most common types: tension-type headache and migraine.

Pathogenesis Multiple factors probably play a role in the pathogenesis of tension-type headache and, especially, migraine ( ▶ 14.2.3.2). Positron emission tomography (PET) studies have revealed activation in the brainstem at the beginning of a migraine attack and in the hypothalamus in cluster headache. In a migraine attack, there is first vasoconstriction, then vasodilation. Dilation of the large arteries of the base of the brain is usually accompanied by unilateral, often throbbing headache. Vasodilation was once thought to cause the headache but is now thought to be an epiphenomenon, that is, a result of the same activation of the trigeminovascular system that separately causes headache. Migraine is presumably initiated when a neural process that is not yet completely understood activates the trigeminovascular system, leading to pain. The dura mater, the large arteries of the base of the brain, and the pial vessels all receive sensory innervation from the trigeminal nerve and the gasserian (trigeminal) ganglion. The main function of the sensory trigeminal system is to protect the head from dangerous external influences and stimuli. The pain that arises in primary headache syndromes is of no use to the organism and is thought to be caused by faulty activation of the system.

These changes in the trigeminovascular system are partly caused, or accompanied, by changes in humoral mediators. The neurotransmitter serotonin plays an especially important role, and several vasodilator peptides have been discovered in trigeminal neurons, including substance P, neurokinin A, and the calcitonin gene–related peptide. Antagonists of these peptides, and antibodies against them, are now being tested as drugs for the prevention and treatment of migraine attacks.

Tension-type headache has episodic and chronic forms.

In the IHS classification, sporadic episodic tension-type headache (of greater or lesser frequency) is defined as follows:

A: At least 10 previous episodes (once per month or on at least 12 days per year, or else on more than 1 but fewer than 15 days per month) that met criteria B to D and were present on fewer than 180 days per year overall.

B: Each individual headache episode lasts for 30 minutes to 7 days.

C: The pain is characterized by at least two of the following features:

Bilateral.

Pressing, squeezing, not throbbing.

Of mild to moderate intensity.

Not exacerbated by physical activity, walking, or climbing steps.

D: Both of the following criteria must be fulfilled:

No nausea or vomiting

No photophobia or photophobia, or at most one, but not the other.

E: The headache is not due to any other known disease.

Tension-type headache is illustrated schematically in ▶ Fig. 14.1.

Fig. 14.1 Tension-type headache. (These images are provided courtesy of Mumenthaler M, Daetwyler Ch, Kopfschmerz Interaktiv, Instructional Media Department [AUM-IAWF] of the University of Bern Faculty of Medicine, 2001.)

Chronic tension-type headache occurs, by definition, on more than 15 days per month for at least three consecutive months and on at least 180 days per year. The pain is usually diffuse, sometimes felt most intensely on the forehead, temples, or vertex, and often of a dull rather than throbbing character. It does not worsen with exercise. It can arise at any time of day, but most often in the morning on awakening or shortly after the patient gets up. There are usually no accompanying symptoms. This type of headache mainly affects young or middle-aged persons, men just as commonly as women, although the subjective suffering of female patients tends to be worse. The headaches are often provoked by weather changes, sleep deprivation, overconsumption of alcohol (“hangover headache”), and emotional tension. The neurologic examination reveals no abnormalities.

Treatment The main components of treatment are:

Lifestyle readjustment.

Dealing with external and internal sources of emotional tension.

On the pharmacologic level of attack management, acetaminophen 1,000 mg, ibuprofen 200 to 600 mg, or a combination of acetylsalicylic acid 250 mg, acetaminophen 250 mg, and caffeine 50 mg. Excessive intake of drugs to treat chronic tension-type headache can cause medication-overuse headache (see section ▶ 14.2.4, ▶ 14.2.4.7).

Important prophylactic measures include relaxation exercises (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation by the Jacobson’s technique), endurance training, and stress-management training, ideally in a multidisciplinary treatment program. Acupuncture does not lessen the frequency of attacks of episodic tension-type headache. Antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) can be considered for patients with the chronic form of the disorder.

Note

Migraine, a type of primary headache, is the second most common type of headache overall, after tension-type headache (see earlier). It is characterized by intense, often hemicranial headaches that last several hours, occur at variable frequency, and are accompanied by nausea (and sometimes vomiting), photophobia, and phonophobia. The pain worsens with physical activity. The first headaches often occur in the patient’s teens. Migraine is markedly more common in women than in men.

Pathogenesis The pathogenesis of migraine is discussed more extensively earlier at the beginning of this section.

Epidemiology The frequency of migraine in schoolchildren is generally estimated at 5%. Among older children, it affects girls more commonly than boys.

In adults, epidemiologic studies have revealed an unexpectedly high prevalence of migraine, roughly 25% in women and 17% in men. More than half of all “migraineurs” have a family history of headache (not necessarily of typical migraine). Women are more commonly affected, or, at least, they more commonly seek medical help.

Clinical features Migraine without aura (also called simple, classic, or common migraine), whose sole neurologic manifestation is headache, is distinguished from migraine with aura (also called complicated migraine), in which additional neurologic manifestations are present. The IHS criteria for the diagnosis of migraine without aura are as follows:

A: The patient has had at least five attacks fulfilling criteria B to D.

B: The attacks last 4 to 72 hours (if untreated or unsuccessfully treated).

C: The headache has at least two of the following features:

Unilaterality.

Throbbing character.

Moderate or marked intensity.

Worsening when the patient walks, climbs stairs, or performs similar everyday physical activities, which are avoided.

D: At least one of the following symptoms is present during the headache:

Nausea and/or vomiting.

Oversensitivity to light and noise.

E: The headaches are not attributable to any other disease.

Persons with migraine have often had uncharacteristic headache attacks in their childhood. They suffer from episodic abdominal pain and vomiting appreciably more frequently than the general population. Episodic headaches that only arise in adulthood are truly “hemicranial” in only about 65% of cases. The pain is often described as throbbing, pulsating, piercing, and deep; it worsens with any kind of physical exertion, even as mild as climbing a staircase, and with external stimuli such as light and noise. It reaches maximum intensity within 1 hour or a few hours, and 60% of patients have nausea and/or vomiting. Because of their oversensitivity to light and noise, patients usually withdraw to a dark and quiet room during the attack. They often cannot tolerate odors either. Allodynia, that is, pain felt merely on light touch of certain areas of the skin, has been described as occurring in 70% of patients during attacks. In many patients, the attacks are almost always on the same side of the head, but absolute constancy of the affected side should arouse suspicion of secondary headache. The attacks generally last at least 1 hour and may last for many hours; their frequency varies from a few per year to several per week. The typical features of migraine are shown schematically in ▶ Fig. 14.2.

Fig. 14.2 Migraine attack. (These images are provided courtesy of Mumenthaler M, Daetwyler Ch, Kopfschmerz Interaktiv, Instructional Media Department [AUM-IAWF] of the University of Bern Faculty of Medicine, 2001.)

Chronic migraine is defined as consisting of attacks that occur on more than 15 days per month for at least three consecutive months. An intense migraine attack that lasts longer than 72 hours is called status migrainosus. An aura without headache can also last a week or more. (For migraine auras, see the next subsection.)

Precipitating factors Common triggers are emotional stress (responsibilities, worries, excessive demands, tension) or, alternatively, diminishing stress and prolonged lying in bed (Sunday or holiday migraine). Further possible precipitating factors are weather changes and photic stimuli (e.g., bright sunlight). In women, migraine attacks may regularly come just before, or at the same time as, menstruation. Certain substances in food, such as chocolate or aspartame, can also precipitate migraine in some persons. The pressor substance tyramine, which is found in certain kinds of cheese, is a rare migraine trigger; it can also cause hypertensive crises in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Migraine induced by trauma (“footballer’s migraine”) has been described as well.

Diagnostic evaluation In persons with classic migraine, the neurologic examination is normal. The electroencephalogram (EEG) may show nonspecific changes, usually slow waves.

Treatment The treatment of common migraine depends on the frequency and severity of the attacks.

Rare and mild attacks often need no treatment. Moderately severe, not very prolonged attacks that are relatively rare (occurring less than three times per month) can be managed by treating the individual attacks. Mild to moderate attacks can be effectively treated early on in each attack with analgesic drugs or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in adequate doses, for example, acetylsalicylic acid 1,000 mg, acetaminophen 1,000 mg, ibuprofen 200 to 600 mg, or the fixed combination of acetylsalicylic acid 250 mg, acetaminophen 250 mg, and caffeine 40 mg. For nausea, an antiemetic drug should be given as well, for example, metoclopramide 20 mg by mouth or, if necessary, as a suppository. Moderate to severe attacks are often treated with triptans (usually by mouth); many patients prefer triptans because they are more effective than the analgesics and relieve pain faster. They are also more effective than ergotamines, which should no longer be given because of their side effects.

Practical Tip

The available triptan preparations differ in the strength and latency of pain relief and in their side effects. If necessary, a triptan can be given by injection (sumatriptan) or as a nasal spray (sumatriptan, zolmitriptan). The oral triptans that relieve pain fastest are rizatriptan and eletriptan.

If the attacks occur more than three times per month and/or severely hamper the patient’s everyday activities because of their duration (>72 hours) or severity, attack prophylaxis should be given. Once begun, this must usually be maintained continuously for months (rarely, years) afterward. First-line drugs for attack prophylaxis are the β-blockers propranolol and metoprolol, the anticonvulsants topiramate and valproate, and the calcium antagonist flunarizine. Second-line drugs include antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine), gabapentin, naproxen, acetylsalicylic acid, and magnesium. These recommendations also apply to the various types of complicated migraine described later.

Note

More than one-third of all persons with migraine suffer from other neurologic manifestations before the headache itself begins, for example, visual or sensory disturbances, difficulty speaking, paralysis, vertigo (see section ▶ 12.6.2, ▶ Vestibular Migraine), or abdominal symptoms. This condition is called migraine with aura or, in the traditional nomenclature, complicated migraine.

Migraine auras develop over 5 to 20 minutes and end within 60 minutes at most. They can be very dramatic, sometimes overshadowing the headache to such an extent that the patient’s illness is not immediately recognizable as migraine. In pathophysiologic terms, auras have been correlated with the phenomenon of spreading depression (of Leão), a wave of cortical neuronal discharge followed by neuronal silence that begins in the visual cortex and sweeps outward. Regional cerebral blood flow decreases during an aura and increases afterward.

Sometimes, an aura can be the only symptom of a migraine attack. This is called a typical aura without headache (or, traditionally, “migraine sans migraine”).

We will now individually describe the major clinical types of migraine with aura.

Migraine with ophthalmic aura This is characterized by visual symptoms that precede the headache. About one-third of persons with migraine have ophthalmic auras. The typical kind is a scintillating scotoma, that is, a flashing figure bordered by a bright, zigzag line (“fortification figure”—think of a crenellated medieval fortress), which is seen in both eyes. It arises in the center of one visual hemifield and then travels outward for 5 to 15 minutes until it falls out of view in the periphery, leaving behind a transient impairment of vision in the hemifield ( ▶ Fig. 14.3). The scintillating scotoma is followed by an attack of hemicranial headache, usually on the opposite side. Occasionally, no headache follows (migraine sans migraine); patients with this type of migraine may have a permanent visual field defect. There are also rare cases in which the visual disturbance affects one eye only (retinal migraine).

Fig. 14.3 Scintillating scotoma during an attack of ophthalmic migraine: typical fortification figures.

Ophthalmoplegic migraine This is defined as a migraine-like headache accompanied by ipsilateral weakness of the extraocular muscles, usually due to oculomotor nerve palsy. The existence of this type of membrane is questionable. Other causes of ophthalmoplegia must be ruled out.

An aura consisting of a hemisensory deficit or aphasia, previously called migraine accompagnée, now appears in the IHS classification under the heading typical aura with migraine headache. This variant of migraine usually begins in childhood or adolescence. In an attack, paresthesia arises in a small area, most often on an arm or the face, spreads within a few minutes to cover a larger area (e.g., from the thumb to the entire arm to the face), and then slowly subsides. Aphasia may follow or may be the sole manifestation of the aura. The typical hemicranial headache usually comes after the neurologic disturbance, on the same or the opposite side, enabling the diagnosis of migraine to be made. Headache may also be absent, in what is called aura without headache (traditionally, migraine accompagnée sans migraine); this type of migraine is especially common in children and is the initial manifestation of migraine in nearly half of all cases.

An EEG recorded after an aura shows a focal abnormality that may take a few days to resolve. Attacks may also be accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis. CSF pleocytosis or auras without headache call for careful diagnostic evaluation to rule out other potential causes of the problem, for example, transient ischemia.

Familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) This is characterized by recurrent migraine attacks accompanied by a transient hemiparesis, hemiplegia, or hemisensory deficit that resolves within 1 hour. Most patients have, or had, a first- or second-degree relative with the same disorder. There are multiple genetic subtypes. FHM1 is due to a mutation in the CACNA1A gene on chromosome 19, while FHM2 is due to a mutation in the ATP1A2 gene on chromosome 1.

Basilar migraine In this type of migraine, the symptoms reflect a pathophysiologic process located in both cerebral hemispheres as well as the brainstem. The name of the disorder reflects an earlier belief that the underlying abnormality was limited to the distribution of the basilar artery, which may not be true. The symptoms of the aura include varying combinations of dysarthria, dizziness, tinnitus, hearing loss, double vision, and ataxia, and, typically, simultaneous bilateral paresthesia and visual impairment in both hemifields of both eyes. Consciousness is variably impaired, to an extent ranging from somnolence to coma. The patient may be confused during the attack and amnestic for it afterward. The headache is generally occipital. Basilar migraine mainly affects girls and young women.

Special types of migraine with aura These include abdominal migraine, which is not uncommon, mainly in children, and cyclic vomiting syndrome; both of these disorders are often a precursor of migraine (i.e., headache develops later). Adults with migraine may have accompanying psychiatric manifestations such as mood swings (anxiety, depression), cognitive disturbances, confusion, agitation, or even “migraine psychosis” (dysphrenic migraine). Recurrent attacks of dizziness, termed vestibular migraine (see section ▶ 12.6.2, ▶ Vestibular Migraine), have also been described; other syndromes in this class include benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood and episodic ataxia (cerebellar migraine).

Treatment of migraine with aura Migraine with aura is treated in the same way as simple migraine (see earlier).

Note

The category called “trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias” in the new IHS classification comprises pain syndromes that mainly affect the face and have accompanying autonomic manifestations, for example, conjunctival injection, facial erythema, lacrimation, and altered nasal secretion ( ▶ Table 14.4). All of them are of a more or less paroxysmal nature, with short-lasting individual attacks of pain. They are as follows:

Cluster headache (see later).

SUNCT syndrome ( ▶ SUNCT).

Trigeminal neuralgia (see section ▶ 14.3.1).

Paroxysmal hemicrania ( ▶ Paroxysmal Hemicrania).

|

Disorder |

Site of pain |

Duration of attacks |

Frequency of attacks |

Phenomena during an attack |

Remarks |

|

Cluster headache |

Periorbital, frontal, temporal, maxillary |

15–180 min |

1–8/d |

Horner syndrome, conjunctival injection, tearing, runny or stuffed nose, periorbital edema |

Always on the same side |

|

Paroxysmal hemicrania |

Periorbital, temporal |

2–30 min |

15/d |

Conjunctival injection, tearing, runny or stuffed nose, eyelid edema, sweating, Horner syndrome |

Responds to indomethacin |

|

Hypnic headache |

Diffuse |

At least 15 min |

>15 nights per month |

None |

Headaches awaken patient from sleep, onset after age 50, considered a rare type of primary headache |

|

SUNCT |

Periorbital, temporal |

5 s to 5 min |

≥100 per day |

Conjunctival injection, tearing |

Must be distinguished from cluster headache and trigeminal neuralgia |

|

Trigeminal neuralgia |

Distribution of one branch of the trigeminal nerve (usually maxillary) |

Seconds |

A few to 100 per day |

Painful contraction of the affected side of the face |

Usually idiopathic in older patients, often symptomatic in younger ones |

|

Abbreviation: SUNCT, short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing. |

|||||

Epidemiology Cluster headache (older, alternative name: “Bing–Horton neuralgia”) is about 1/10 as common as migraine. Unlike migraine, it is much more common in men, particularly smokers. It often begins in middle age or old age.

Pathogenesis and etiology Cluster headache attacks tend to occur in a circadian rhythm. The disorder is attributed to a functional disturbance of the diencephalon, as PET studies have shown increased activity in the hypothalamus during the attacks. Individual attacks can be induced by alcohol, histamine, or nitroglycerin. Aside from primary cluster headache, there are also symptomatic forms, caused, for example, by mass lesions.

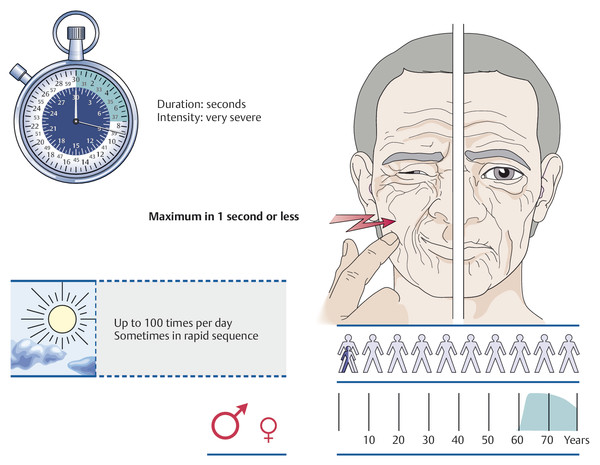

Clinical features These are highly typical and are illustrated in ▶ Fig. 14.4.

Fig. 14.4 Cluster headache attack. (These images are provided courtesy of Mumenthaler M, Daetwyler Ch, Kopfschmerz Interaktiv, Instructional Media Department [AUM-IAWF] of the University of Bern Faculty of Medicine, 2001.)

The headache attacks always occur on the same side of the head. The pain is mainly felt in the temple, eye, and forehead. About one-third of patients are regularly awakened by the attacks at certain times of night. Most patients have one to three attacks per 24-hour period when they are having attacks (i.e., during a “cluster,” see later). Photophobia and nausea are occasional accompanying manifestations. During an attack, the patient does not lie down (as in a migraine headache) but sits up or paces around restlessly. Typical physical findings in an attack are conjunctival injection, lacrimation, a runny or stuffed nose, and, often, redness of the face, all on the same side as the headache ( ▶ Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5 Right-sided cluster headache attack in a 52-year-old patient. Note the narrow palpebral fissure, conjunctival injection, and periorbital erythema.

In episodic cluster headache, the attacks occur during periods called “clusters” that may be one to several weeks long, with months or even years of freedom from headache in between. In the rarer, chronic form of the disorder, there are no attack-free intervals, and therefore no clusters (despite the name “chronic cluster headache”).

Transitional forms It is not uncommon for typical migraine to be replaced by typical cluster headache (or vice versa) at some point in a patient’s life. Some patients, too, have headaches with some of the features of both.

Diagnostic evaluation The acute attacks, because they are brief, are only rarely observed by the physician. The diagnosis depends on a precise clinical history (as in nearly all types of headache).

Differential diagnosis This disorder must be carefully differentiated from facial neuralgias such as trigeminal neuralgia, nasociliary neuralgia, and Sluder neuralgia (all described in section ▶ 14.3.1), as well as from SUNCT syndrome, paroxysmal hemicrania, and hypnic headache (all described later in this section).

It must also be borne in mind that symptomatic headache may clinically resemble typical cluster headache; the causes include tumors, inflammatory and infectious processes, and multiple sclerosis.

Treatment The treatment of an acute attack is difficult. Triptans can be given by subcutaneous injection, or the patient can be given pure oxygen to breathe (7 L per minute for 15 minutes). Medications for the reduction of attack frequency include verapamil and, as a second choice, indomethacin, sometimes in combination with a tricyclic antidepressant. A brief course of cortisone treatment is often effective. The chronic form responds to lithium.

This type of headache usually arises in adulthood and is equally common in men and women. The pain is always unilateral and, like cluster headache, located in the orbit and temple. The attacks last 2 to 30 minutes and generally occur at least five times per day. They are accompanied by the same autonomic manifestations as cluster headache.

The absolutely characteristic feature of paroxysmal hemicrania is that it responds to treatment with indomethacin.

This acronym (pronounced “sunked”) stands for “short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing.” The disorder is characterized by brief attacks of pain (lasting 5 seconds to a few minutes each) that always arise on the same side of the head, in the orbital and temporal area; they are accompanied by ipsilateral conjunctival injection and tearing, and sometimes by other autonomic manifestations. There are 3 to 100 attacks per day. SUNCT with a very high frequency of attacks can easily be mistaken for trigeminal neuralgia. SUNCT occasionally responds to treatment with antiepileptic drugs.

The main features and differentiating characteristics of the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, and of two other paroxysmal pain syndromes that can resemble them, are listed in ▶ Table 14.4.

▶ Table 14.5 lists a few rarer types of primary headache that will be briefly discussed in this section.

Stabbing (“icepick”) headache consists of unprovoked attacks of pain lasting only a few seconds that are felt at variable sites on the skull. The condition is harmless.

Primary exertional headache is holocranial and usually of a throbbing type. It can be induced by a variety of physical activities.

Cough headache is induced by heavy coughing. It last a few seconds to a few minutes.

Headache associated with sexual activity (orgasmic or coital headache) is a variety of exertional headache; some patients also have headache induced by other activities. It lasts a few minutes to a few hours. The absence of meningismus generally distinguishes an episode of coital headache from SAH, which can also occur during sexual intercourse.

Primary headache that wakes the patient from sleep is called hypnic headache or “alarm-clock headache syndrome.” This disorder affects persons over age 65. The headaches are generally not very intense; they generally last 15 minutes to 1 hour and rarely for several hours. This condition, too, is harmless.

Hemicrania continua is always unilateral and always on the same side. The pain is of moderate to severe intensity; it is accompanied by autonomic manifestations like those of paroxysmal hemicrania ( ▶ Paroxysmal Hemicrania) and, like the latter condition, responds to indomethacin. Acetylsalicylic acid is sometimes effective as well.

New daily persistent headache begins as a diffuse headache in a person who has not suffered from headaches before and then persists. It is felt as a mild to moderately intense pressure in the head. It does not worsen with exercise. This diagnosis should only be made after secondary (symptomatic) headache has been excluded.

|

Type |

Clinical features |

Remarks |

|

Hemicrania continua |

Persistent unilateral headache |

Responds to indomethacin and sometimes to aspirin |

|

“Ice-cream headache” |

Acute headache, usually temporal, lasting 20–30 s, precipitated by a cold stimulus on the palate (such as ice cream) |

– |

|

Cough headache |

Precipitated by coughing, abdominal straining, or bending over; an intense, diffuse headache lasting a few seconds |

Usually innocuous, but sometimes due to a pathologic process in the posterior cranial fossa |

|

Coital headache |

Sudden onset, lasts minutes or hours, sometimes accompanied by vomiting |

No meningismus (differential diagnosis: subarachnoid hemorrhage) |

Secondary headaches are not diseases in themselves but “merely” symptoms of another, underlying disease. ▶ Table 14.6 contains an overview of the major causes of secondary headache. Only a small minority of patients whose chief complaint is headache have secondary headaches. Alarm symptoms indicating the likely presence of secondary headache are listed below under “ ▶ 14.2.4.9.”

|

Type |

Cause |

Features, remarks |

|

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (section ▶ 6.6.2) |

Usually rupture of a saccular aneurysm at the base of the brain |

Sudden, extremely severe headache, usually diffuse, accompanied by vomiting, drowsiness, and meningismus |

|

Intracranial mass (section ▶ 14.2.4) |

Brain tumor, chronic subdural hematoma, brain abscess |

Permanent headache of increasing severity; emesis, bradycardia, papilledema, focal neurologic deficits; neuroimaging is essential |

|

Occlusive hydrocephalus |

Aqueductal stenosis, intraventricular mass, mass in posterior cranial fossa |

Manifestations like those of a brain tumor; neuroimaging is essential |

|

Malresorptive hydrocephalus (section ▶ 6.12.6) |

Prior subarachnoid hemorrhage or meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis |

Diffuse, increasingly severe headache, gait ataxia, incontinence; neuroimaging is essential |

|

Intracranial hypotension |

Prior LP, (rarely) spontaneous, dural tear |

Orthostatic headache that improves or resolves when the patient lies down; normal neurologic examination, CSF not obtainable by LP (or only with aspiration); elevated CSF protein concentration; meningeal contrast enhancement |

|

Pseudotumor cerebri |

Often seen in overweight young women; may be secondary to prior head trauma, anovulatory drugs, steroid withdrawal, tetracycline, etc. |

Chronic headache without any other detectable cause; often papilledema; sometimes, visual loss lasting seconds (amblyopic attacks); CT or MRI reveals slit ventricles; elevated pressure on LP |

|

Meningitis |

Bacterial or viral meningitis |

Hyperacute in purulent meningitis; very severe headache, meningismus, drowsiness, vomiting |

|

Carcinomatous or leukemic meningitis |

Primary tumors of various types, e.g., breast carcinoma |

Chronic, diffuse headache, cranial nerve deficits or spinal radicular deficits; LP and CSF cytology are essential; can often be diagnosed by MRI |

|

Postinfectious headache |

After recovery from a (viral) infection |

Diffuse, often intractable headache without other neurologic abnormalities, resembling tension headache; mild CSF pleocytosis |

|

ENT disease |

Chronic sinusitis, neoplasia in the pharynx |

Headache or facial pain depending on the site of the disease process; no neurologic deficit |

|

Eye disease |

For example, heterophorias (latent strabismus), acute glaucoma, iritis, infectious/inflammatory processes in the orbit |

Usually frontal and temporal headache |

|

Dental conditions |

Pulpitis, periodontitis, retained teeth, and myofascial pain syndrome due to malocclusion |

Severe, acute facial pain or chronic facial pain, depending on cause |

|

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; LP, lumbar puncture; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

||

Headache is an early or late major symptom in about half of all patients with brain tumors, particularly those with tumors in the posterior fossa.

Intermittent obstruction of CSF outflow causes sudden attacks of very intense headache accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and, rarely, brief and transient loss of consciousness. The patient may have opisthotonus as well. The attack may arise gradually over a few seconds or minutes, rarely lasts longer than a few minutes, and generally subsides more slowly than it arose. Any process that obstructs CSF outflow intermittently can produce headaches of this type; a classic example is colloid cyst of the third ventricle.

Pathophysiology The intracranial hypotension syndrome has also been called the low CSF volume syndrome, the CSF loss syndrome, and the hypoliquorrhea syndrome. Its symptoms are due to a reduction of intracranial pressure. It can arise after traumatic brain injury, because of CSF loss (by lumbar puncture, through a dilated nerve root sleeve, or through a tear in the dura mater, e.g., because of perforation by a bone spur), or without any evident cause.

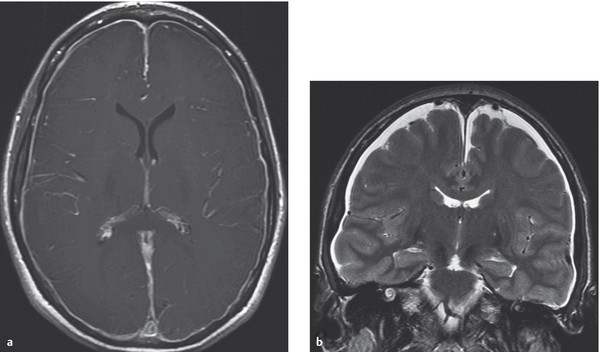

Intracranial hypotension can be complicated by a subdural hematoma or hygroma ( ▶ Fig. 14.6b).

Fig. 14.6 MRI in intracranial hypotension syndrome. a Contrast enhancement of the dura mater (pachymeninx). In meningitis, the leptomeninges take up contrast medium as well. b Subdural hygromas over both cerebral convexities.

Clinical features The typical symptom is a very intense orthostatic headache felt whenever the patient stands up, which diminishes on lying down. Persistent, severe intracranial hypotension may be manifested by confusion, nausea/vomiting, tinnitus, hearing loss, and diplopia.

Diagnostic evaluation Lumbar puncture in the recumbent patient reveals a CSF pressure below 5 cm H2O, possibly so low that CSF does not flow spontaneously at all and must be aspirated from the needle. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals contrast enhancement of the dura mater (pachymeninx) ( ▶ Fig. 14.6a). This differs from the characteristic MRI finding in chronic meningitis, that is, leptomeningeal contrast enhancement ( ▶ Fig. 6.44).

Treatment and prognosis The prognosis is good: the disorder usually resolves spontaneously.

The efficacy of bed rest, fluid administration, and normal saline infusions is debated. Pharmacotherapy (e.g., with caffeine) may help. An epidural blood patch is an effective treatment. Surgical closure of a CSF leak is only rarely necessary.

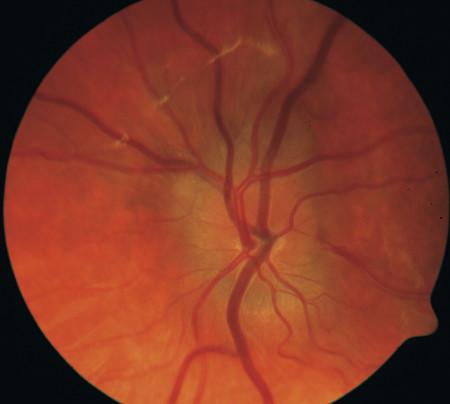

Pseudotumor cerebri This syndrome can be considered the opposite of the intracranial hypotension syndrome, so to speak, in that the headaches are due to intracranial hypertension. Most patients are overweight young women. The neurologic examination usually reveals papilledema, particularly in patients who, when closely questioned, report having had attacks of loss of vision ( ▶ Fig. 14.7). Elevated intracranial pressure is confirmed by lumbar puncture. In imaging studies, the ventricles are abnormally narrow (“slit ventricles”) and the optic nerve sheath is dilated ( ▶ Fig. 14.8). The treatment consists of dehydrating measures, repeated lumbar punctures, and, above all, dedicated and maintained weight loss.

Fig. 14.7 Papilledema in pseudotumor cerebri.

Fig. 14.8 Head MRI in a patient with intracranial hypertension. The coronal images reveal dilatation of the CSF spaces in the optic nerve sheath.

Headaches are a prominent symptom of meningitis (see section ▶ 6.7). In bacterial meningitis, the headache usually begins subacutely or acutely, along with fever and constitutional signs of illness. There is marked meningismus. Intracranial abscesses usually cause focal neurologic deficits.

Ninety percent of patients with acute SAH due to a ruptured aneurysm (see section ▶ 6.6.2) complain of headache. Most patients experience an extremely intense headache that begins suddenly (“thunderclap headache”) and then persists.

Space-occupying intracranial hemorrhages (see section ▶ 6.6.1) often cause acute headache, which is frequently initially felt on the side of the hemorrhage. There are always accompanying focal neurologic deficits.

It is not entirely clear whether patients with arterial hypertension are more prone to headaches than normotensive persons. An association between blood pressure and headache is well documented only for hypertensive crises.

In pheochromocytoma, headaches arise abruptly. The attacks, lasting a few minutes to an hour at most, are usually associated with diaphoresis, palpitations, and pallor.

Headache is only rarely a symptom of intracranial arterial occlusion.

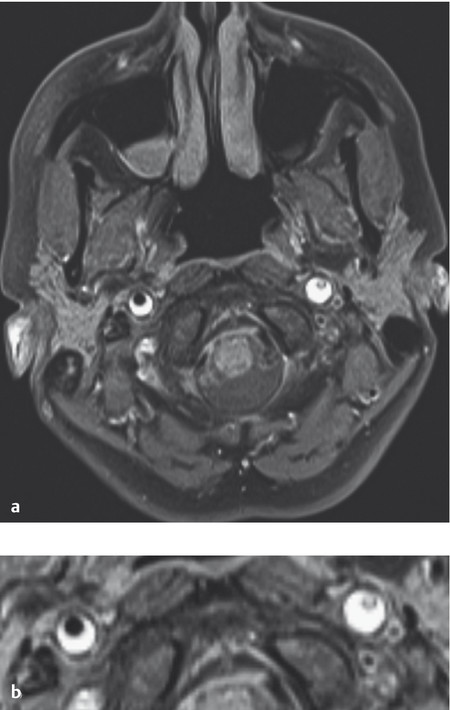

Dissection of the internal carotid artery ( ▶ Fig. 14.9) can arise spontaneously or after trauma (even mild) to the head or neck. It causes very intense pain on one side of the neck, radiating into the face and temple. It is sometimes accompanied by Horner syndrome (see section ▶ 12.3.5). Signs of cerebral ischemia may be absent. Similarly, vertebral artery dissection causes pain in the ipsilateral occipital and nuchal region; it can arise spontaneously, after local trauma, or after a whiplash injury of the cervical spine. Clinical manifestations usually arise only if the vertebral artery, the basilar artery, or their branches are narrowed or occluded by an embolus or appositional thrombus.

Fig. 14.9 Bilateral carotid dissection of the carotid artery: left, with pseudo-occlusion; right, with high-grade stenosis. b is a close-up view of a. The typical finding is a sickle-shaped hyperintense mural hematoma eccentrically enclosing the residual lumen, which appears as a low-signal flow void.

Cerebral venous thrombosis or venous sinus thrombosis is usually accompanied by headache. For this entity, see the relevant discussion in section ▶ 6.5.10. Venous sinus thrombosis can also cause malresorptive hydrocephalus (see section ▶ 6.12.6).

Pathogenesis Cranial (also called temporal) arteritis is a giant-cell arteritis, that is, an autoimmune disease causing typical changes of the tunicae media and elastica interna of large and midsized arteries. It almost exclusively involves the branches of the external carotid artery. Large arteries elsewhere in the body can also be affected; involvement of the interior carotid artery is very rare.

Clinical features This disorder nearly exclusively affects persons over age 50, women more often than men. Headache is often the initial symptom. It is very intense, usually located in the forehead and temple, and either unilateral or, more commonly, bilateral. The patient may complain of severe, continuous pain, or else of pain on chewing (“claudication” of the tongue and muscles of mastication). The superficial temporal arteries are often thickened and tortuous; they are tender to palpation and cease to pulsate in the advanced stage of the disease ( ▶ Fig. 14.10). In exceptional cases, however, the vessels may appear normal. The headache can also be in an atypical location. If the patient has giant-cell arteritis as a generalized phenomenon, headache may be absent, but there may be other manifestations such as optic nerve involvement, retinal arterial occlusion, paresis of the extraocular muscles, and polyneuropathy.

Fig. 14.10 Temporal arteritis in a 65-year-old man. Note the thickened, painful, no longer pulsating superficial temporal artery.

Systemic manifestations such as fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, nocturnal diaphoresis, and subfebrile temperature are very common. They are also seen in a further prominent manifestation of giant-cell arteritis—a syndrome called polymyalgia rheumatica, characterized by pain in the large proximal joints of the limbs.

Note

The most dreaded complication of giant-cell arteritis is sudden blindness due to occlusion of posterior long ciliary arteries ( ▶ Fig. 14.11).

Fig. 14.11 Ischemia in temporal arteritis, with disc pallor and thin retinal arteries. (This image is provided courtesy of Prof. Josef Flammer, emeritus head of the Ophthalmological Clinic, University of Basel, Switzerland.)

Diagnostic evaluation The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and the C-reactive protein concentration are markedly elevated in practically all cases; the ESR is generally above 50 mm/h in the first hour.

Color-duplex sonography shows a dark halo around the wall of the superficial temporal artery, which is thickened by arteritis. MRI can also reveal inflammation of the arterial wall, but the definitive diagnostic procedure is biopsy of the superficial temporal artery.

Treatment Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone 1 mg/kg body weight orally once a day in the morning) should be given until the ESR reverts to normal. The dose can then be slowly reduced, but corticosteroid therapy must be continued for many months, often years. A recurrent elevation of the ESR indicates a new exacerbation of the inflammatory process, which often takes years to “burn out.”

Note

If there is a well-grounded clinical suspicion of temporal arteritis, steroids should be given immediately without waiting for the histologic findings. This is done mainly to prevent serious ocular complications, which can arise rapidly and without warning.

Spondylogenic headache, alternatively called cervicogenic headache (or even, inappropriately, “migraine cervicale”), is defined as pain in the head or face caused by a pathologic process in the bony or soft tissues of the neck.

Clinical features Spondylogenic headache is usually, but not always, unilateral. It is either nuchal or radiating from the back to the front of the head (in which case patients may accompany their verbal description of the pain with a hat-doffing hand gesture, by way of illustration). It can also be felt in the face. It tends to arise with certain head movements and postures (e.g., prolonged reading) or at night when the head has been kept in an unfavorable position for a long time. The diagnostic criteria are summarized in ▶ Table 14.7.

|

Criteria |

Description |

|

Characteristics of the pain |

|

|

Cervical spine |

|

|

Precipitating and alleviating factors |

|

|

Accompanying symptoms |

|

Treatment The treatment is difficult. In acute cases, particularly when torticollis is also present, traction can be tried. The immediate success of briefly applied manual traction can also be used as diagnostic evidence for spondylogenic headache.

Persistent or chronic spondylogenic headache can be alleviated by relative immobilization of the cervical spine in a soft collar or hard (Philadelphia) collar for a few days, as well as by proper positioning of the head at night, local heat application, muscle relaxant drugs, and NSAIDs. CT-guided local anesthetic infiltration of the cervical intervertebral joints can help in rare cases.

Headache can be an acute effect of certain drugs and other substances, among them nitric oxide (NO), nitroglycerin, histamine, carbon monoxide (CO, generated, for example, in a poorly ventilated oven), alcohol, monosodium glutamate (“Chinese restaurant headache”), amyl nitrite (“hot dog headache”), cocaine, and cannabis.

The withdrawal of certain drugs and other substances after longstanding use can also cause headaches, for example, caffeine, opioids, and estrogen.

Medication-overuse headache: the longstanding, regular consumption of analgesic drugs by a headache patient can itself cause diffuse, more or less continuous headaches. By definition, medication-overuse headache is present on at least 15 days of each month. It is felt on both sides of the head, usually as a throbbing pain. It is typically of moderate intensity.

Note

Any analgesic drug—not just ergot derivatives and triptans, but also nonprescription drugs such as acetaminophen—can cause medication-overuse headache if taken to excess.

Chronic triptan use, however, causes medication-overuse headache more rapidly than chronic use of other drugs. The diagnosis requires, by definition, that the offending drug has been taken on at least 10 days per month for at least three consecutive months and also that the patient’s headache reverts to its original quality once the drug has been discontinued.

The treatment is difficult. Analgesic consumption must be markedly reduced; for psychological support, antidepressant drugs may help, but the most important factors are the sustained, direct involvement of the treating physician and the provision of behavior therapy.

The neck-tongue syndrome is rare: sudden turning of the head immediately leads to an occipital headache and simultaneous paresthesia of one-half of the tongue.

Ophthalmologic headache can be caused by refractory anomalies but is mainly due to heterophorias (squints) in childhood. The headache arises over the course of the day. The problem resolves after appropriate treatment by an ophthalmologist.

Sinusitis can cause intractable, often sharply localized headache, as can chronic otitis and space-occupying lesions in the nasopharynx.

Goggle headache is a special type of supraorbital neuralgia caused by wearing tight swimming goggles.

Headache due to a systemic disease can be very severe, particularly in some infectious diseases, such as Q fever. The headache can last far longer than the causative acute infection.

Chronic iron deficiency is a further cause of headache.

Emotional factors are said to play an important role in the pathogenesis of so-called tension headache. This term has been used with a variety of meanings; it generally refers to mainly occipital headaches that are attributed to emotional tension and cause more or less persistent contraction of the nuchal muscles. Tension headache is not the same entity as tension-type headache (discussed in section ▶ 14.2.3).

Headache can also be a heralding symptom of incipient psychosis.

Note

All patients who consult a physician because of headache are in pain and therefore deserve our full attention. More than 90% of them, however, will turn out not to have a serious medical problem. An important task facing the physician is to be on guard for the occasional cases of headache that are, in fact, due to a dangerous underlying condition.

The main alarm signals are the following:

Headache of an unusual nature arising for the first time, particularly in a patient over age 40.

Continuous headache:

that has been continuous from its onset

or that has become continuous through the confluence of ever more frequent, previously episodic headaches.

Progressively severe headache.

Explosive headache.

Headache that always occurs on the same side and in exactly the same location (except cluster headache or trigeminal neuralgia, both of which, by definition, always occur in the same place).

Headache with accompanying features:

Vomiting (except in migraine).

Progressive personality change.

Epileptic seizures.

Headache with accompanying neurologic abnormalities:

Neurologic deficits.

Papilledema.

neuropsychological abnormalities.

Headache that does not conform to any of the typical types of headache.

If any of the above apply, further investigation is needed, usually with an imaging study.

Key Point

Facial pain is often due to a lesion of a sensory nerve in the face, most commonly the trigeminal nerve. It typically presents with very brief, but very intense attacks of pain (“classic” or “genuine” neuralgia). There are also various kinds of facial pain with other pathogenetic mechanisms, for example, a structural anomaly of the temporomandibular joint. The pain may resemble neuralgia in these conditions as well. Patients with any kind of facial pain always require careful differential diagnostic evaluation.

Neuralgia is defined as pain in the distribution of a peripheral nerve. It is often of a tearing or piercing quality. The face is a common site of intense, brief (rarely, longer-lasting), lightning-like attacks of pain. Often, these can be induced by touching the faces in certain places (trigger points) or by activities such as speaking, swallowing, or chewing.

Epidemiology The prevalence of trigeminal neuralgia is reportedly 100 to 400 per 1 million people.

Etiology and pathogenesis Excitation of tactile fibers is presumed to cross over abnormally onto nociceptive fibers in what is called “ephaptic transmission.” In idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, the underlying cause is thought to be a lesion of the myelin sheath of the trigeminal nerve root at its zone of entry into the pons, brought about either by the aging process or else by persistent mechanical irritation from a pulsating vascular loop lying on the root. In symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia, another underlying disease (e.g., tumor, multiple sclerosis) affects the trigeminal nerve or its brainstem fibers, producing pain.

Clinical features As mentioned earlier, there is a distinction between idiopathic and symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia:

Idiopathic (essential) trigeminal neuralgia only affects persons over age 50. The pain is always felt in the same area, usually in the distribution of the maxillary and/or mandibular nerve. The pain is always unilateral at first; however, in occasional cases, pain later affects the other side of the face as well. The pain is described as electric or lancinating (lightning-like) and unbearably intense. Each attack lasts only a few seconds, but the attacks can repeat themselves every few minutes and can occur up to a hundred times a day.

Practical Tip

Patients whose neuralgic attacks occur at very closely spaced intervals may perceive or describe them as continuous. This can cause diagnostic confusion.

The attacks can often be induced by chewing, speaking, or touching particular sites (trigger points) on the face or inside the mouth. Patients with the idiopathic form of the disorder have no abnormalities on neurologic examination. Spontaneous remission is possible, with months or years of freedom from pain. The symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia are illustrated in ▶ Fig. 14.12.

Fig. 14.12 Trigeminal neuralgia. (These images are provided courtesy of Mumenthaler M, Daetwyler Ch, Kopfschmerz Interaktiv, Instructional Media Department [AUM-IAWF] of the University of Bern Faculty of Medicine, 2001.)

Symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia can be caused by multiple sclerosis (see the relevant discussion in section ▶ 8.2), a pontine infarct, or a tumor of the cerebellopontine angle. Patients with the symptomatic form of the disorder can be of any age; compared with those with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, they more commonly suffer from bilateral and/or continuous pain and may have objectifiable neurologic deficits on examination.

Treatment Symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia is treated by the treatment of its underlying cause. Idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, which is much more common, is initially treated with drugs, usually the anticonvulsant carbamazepine (slow dose escalation up to 200 mg three to four times daily) or its structural derivative oxcarbazepine (900–1,800 mg/d). If these are poorly tolerated, other anticonvulsants, including gabapentin, lamotrigine, pregabalin, topiramate, and levetiracetam, can be used as second-line drugs.

If pharmacotherapy does not sufficiently relieve the pain, effective neurosurgical treatments are available.

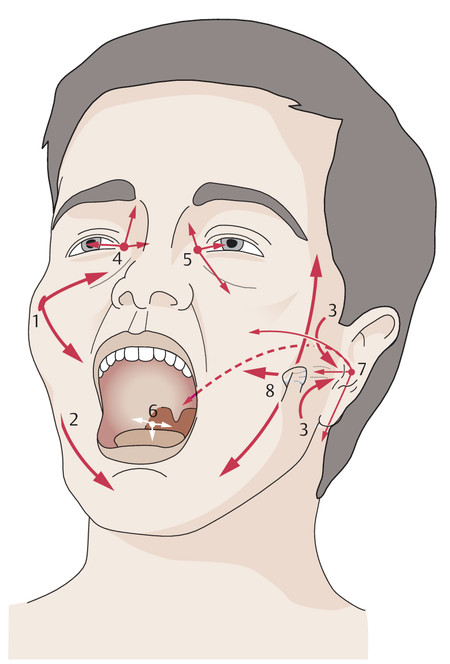

Neuralgias in the face other than trigeminal neuralgia are rare; an overview is provided in ▶ Fig. 14.13.

Fig. 14.13 The sites of various types of facial pain and neuralgia. 1 Trigeminal neuralgia in the distribution of the maxillary nerve (V2). 2 Trigeminal neuralgia in the distribution of the mandibular nerve (V3). 3 Auriculotemporal neuralgia. 4 Nasociliary neuralgia. 5 Sluder neuralgia. 6 Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. 7 Neuralgia of the geniculate ganglion. 8 Craniomandibular dysfunction (also called temporomandibular joint syndrome or “neuralgia”).

In auriculotemporal neuralgia, the pain is located in the temple and in front of the ear. It is usually a sequela of ipsilateral parotid gland disease, appearing a few days or months after the parotid condition resolves.

In nasociliary neuralgia, either episodic or continuous pain is felt in the nose, on the inner canthus, or in the globe of the eye. It is accompanied by erythema of the forehead, swelling of the nasal mucosa, and sometimes conjunctival injection and lacrimation.

Sluder neuralgia is attributed to a pathologic process affecting the pterygopalatine ganglion. Its clinical features resemble those of nasociliary neuralgia. In many patients, the attacks are accompanied by the urge to sneeze. Sluder neuralgia is occasionally associated with sphenoid, ethmoid, or maxillary sinusitis.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is characterized by intense, lightning-like attacks of pain in the base of the tongue, the hypopharynx, and the tonsillar fossa, always only on one side of the head. The pain is continuous in some patients.

Neuralgia of the geniculate ganglion was originally described as a sequela of herpes zoster infection, typically associated with a vesicular rash on the tragus and mastoid process and a peripheral facial nerve palsy (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). It can, however, arise without any preceding rash or palsy. The pain is felt in front of the ear and in the external auditory canal, and also deep in the roof of the palate, the upper jaw, and the mastoid area. It can be accompanied by abnormal taste perception on the anterior half of the tongue and by hypersalivation.

Acute dental disease can cause severe pain in the face.

Craniomandibular dysfunction, that is, dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint, can cause neuralgiform pain. This condition has many names, including temporomandibular joint syndrome, temporomandibular “neuralgia,” myofascial syndrome, and Costen syndrome. It is usually caused by malocclusion and mainly affects young and middle-aged women. Patients typically complain of intermittent or continuous preauricular pain that is brought on, or made worse, by chewing. In about half of all patients, the pain also radiates into the forehead, the lower jaw, and/or the occiput. It is mostly unilateral. Physical examination reveals tenderness of the jaw joint to palpation and, sometimes, restricted opening or closing of the mouth. Dental examination reveals the malocclusion that is the cause of the pain.

This term refers to unilateral, diffusely localized pain in the face, often of a burning, distressing quality. It may have no apparent cause but can also arise after a dental procedure, often a minor and apparently uncomplicated one. The pain is always present, with intermittent exacerbations. Atypical facial pain is most common in middle-aged women.

Several other types of facial pain have been described, most of them rare.

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome consists of intense periorbital pain accompanied by weakness of one or more of the extraocular muscles, probably because of a nonspecific inflammatory process in the cavernous sinus. Treatment with corticosteroids is effective.

Glossodynia (“burning mouth syndrome”) is a more or less permanent, dull, burning, distressing pain in the tongue and mouth, accompanied by paresthesia in these areas. It affects women much more often than men, in a 7:1 ratio. It tends to arise in middle age.

The differential diagnosis of headache and facial pain is nearly always based on the patient’s detailed description of the pain. The clinical features often provide important clues to the cause. Important aspects of differential diagnosis are summarized in ▶ Table 14.8.

|

Clinical features |

Syndrome |

|

Recurrent attacks of intense headache with pain-free intervals |

|

|

Recurrent attacks of intense facial pain with pain-free intervals, usually unilateral |

|

|

Continuous facial pain |

|

|

Intense headache of sudden onset, which then persists |

|

|

Diffuse, usually intense headache of subacute onset, which then persists |

|

|

Headache on standing or sitting that improves when the patient lies down |

|

|

Chronic, or chronically relapsing, diffuse headache of insidious onset and mild to moderate severity |

|

|

Chronic, well-circumscribed headache and facial pain |

|

|

Abbreviation: TMJ, temporomandibular joint. |

|

Key Point

Pain in the shoulder and arm is a common complaint. The differential diagnosis includes conditions treated by a wide range of medical specialties: cervical spine pathology (spondylogenic arm pain); degenerative changes of the shoulder and elbow joints and the adjacent connective tissues (ligaments, tendons, joint capsules); diseases of the cervical nerve roots, brachial plexus, and peripheral nerves (neurogenic arm pain); and vascular diseases. Finally, there remains “arm pain of overuse,” a collection of conditions caused by unusually intense stress on muscles and joints.

An overview of diseases causing pain in the shoulder and arm is provided in ▶ Table 14.9. The clinical features of the more common conditions in this group are described in the following paragraphs.

|

Category |

Etiology |

Remarks |

|

Spondylogenic pain |

Spondylosis |

Nuchal pain at first; pain often radiates diffusely |

|

Disk herniation |

Acute torticollis at first, only later followed by pain radiation in a radicular pattern; objectifiable neurologic deficits |

|

|

Nonspondylogenic nerve root lesion |

Tumor |

Slowly progressive symptoms |

|

Dissection of the vertebral artery |

Acute, unilateral nuchal or occipital pain |

|

|

Brachial plexus lesion |

Tumor |

For example, lung apex tumor (Pancoast tumor) with lower brachial plexus involvement and Horner syndrome |

|

Radiation injury |

Pain and progressive neurologic deficits after a latency period |

|

|

Neuralgic shoulder amyotrophy |

Intense pain for one or more days, followed by weakness of shoulder girdle or arm muscles |

|

|

TOS |

Overdiagnosed; the diagnosis can be accepted if there is a cervical rib or other anomaly of the thoracic outlet |

|

|

Hyperabduction syndrome |

The arm “falls asleep” at night in certain positions |

|

|

Posttraumatic brachial plexus lesion |

Phantom pain, neuroma pain, stump pain, painful and nonsuppressible twitching of the stump |

|

|

Lesion of an individual peripheral nerve (or branch) |

Radial nerve |

Supinator syndrome |

|

Median nerve |

Pronator syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome (most common cause of nocturnal arm pain) |

|

|

Ulnar nerve |

Sulcus ulnaris syndrome |

|

|

Cutaneous sensory branches |

For example, pain in the elbow pit after paravenous injection |

|

|

Degenerative and rheumatologic disorders |

In the shoulder region |

Rotator cuff involvement, impingement syndrome |

|

In the elbow region |

Radial epicondylitis (tennis elbow), ulnar epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow) |

|

|

In the distal forearm and hand |

Radial styloiditis, first metacarpophalangeal joint, e.g., in gout |

|

|

Upper or lower limb (often hand) |

CRPS |

|

|

Brachialgia of vascular origin |

Arterial |

Acute brachial artery occlusion, subclavian steal syndrome |

|

Venous |

Effort thrombosis |

|

|

Tenomyalgic and pseudoradicular overuse syndromes |

Diffuse brachialgia after nonphysiologic overuse of an arm, or secondary to weakness of the shoulder muscles |

Various occupations, e.g., bank teller, or in the wake of trapezius weakness |

|

Rarer causes |

Glomus tumor |

A locally painful blue spot is often visible under the fingernail; the pain increases when the arm is dependent |

|

Abbreviations: CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; TOS, thoracic outlet syndrome. |

||

Note

The cause of spondylogenic shoulder and arm pain is usually degenerative osteochondrosis with spondylotic narrowing of the intervertebral foramina and, possibly, cervical disk herniation. These disease processes compress and mechanically irritate the cervical nerve roots.

Clinical features Conditions of this type always begin with neck pain and/or a painful restriction of head movement. Later on, the pain radiates into the shoulder and, usually, down the arm (cervicobrachialgia). Some patients have diffuse pain, but most have pain in the dermatome of the affected nerve root (i.e., radicular pain): C6 lesions cause pain on the lateral aspect of the forearm and the thumb, C7 lesions cause pain in the middle finger, and C8 lesions cause pain on the ulnar side of the hand and in the fourth and fifth fingers. The objective findings include painful restriction of head movement and, sometimes, radicular neurologic deficits—weakness, loss of segment-indicating reflexes, and diminished sensation in the dermatome of the affected nerve root (cf. ▶ Table 13.1).

Treatment Physical therapy and analgesic drugs are the mainstays of treatment.

Note

Pain in the shoulder and arm is usually due to degenerative changes of the bones, joints, tendons, and other soft tissues.

Rotator cuff dysfunction (formerly called humeroscapular periarthropathy) can arise spontaneously or after shoulder trauma (a blow or sprain) or immobilization. The tendons of the short rotators of the shoulder joint undergo degenerative changes, sometimes with calcification, which lead to irritation of the subdeltoid bursa. The highly typical clinical finding is local shoulder pain on active raising of the arm, particularly with simultaneous internal rotation. It is painful, for example, for the patient to slip the arm into a sleeve while getting dressed. If the abducted arm is then rested on a surface (table, etc.), the pain abates. The diseased tendon(s) is (are) tender to palpation, usually ventral to the shoulder joint. Plain radiographs may reveal calcifications. Rotator cuff tear makes the patient unable to abduct the arm without pain or at all. Rotator cuff dysfunction can be objectively demonstrated with certain functional tests (the Jobe test, the starter test, and the lag sign).

Impingement syndrome is closely related to degenerative disease of the rotator cuff. In this condition, when the arm is abducted, the sensitive area of the rotator cuff comes into contact with the coracoacromial roof.

Frozen shoulder syndrome sometimes represents the end stage of degenerative disease of the rotator cuff, but more commonly arises as a sequela of hemiparesis or myocardial infarction. It is rarely caused by phenobarbital use, and can also come about spontaneously. It is characterized by very painful restriction of shoulder movement, with a slowly progressive course.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS): this often intractable condition was known in the past as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, algodystrophy, or Sudeck dystrophy. The sympathetic nervous system plays an important role in its pathogenesis, particularly as a cause of the characteristic swelling. Faulty information processing in the neurons of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord is thought to be another contributing factor. CRPS can affect any part of the upper or lower limbs but it is particularly common in the hand. It tends to arise after a fracture or other type of trauma, which need not be particularly severe. The clinical findings include the following: soft tissue swelling; smooth, cool, often cyanotic skin; and a very painful restriction of joint mobility. Plain radiographs reveal patchy osteoporosis of the bones in the affected area.

Epicondylitis is characterized by pain at the origins of the extensor and flexor muscles of the hand and fingers on the humeral epicondyles. The pain can be felt spontaneously, on contraction of the affected muscles and tendons, or in response to local pressure. The usual cause is muscle overuse. The commonest type is lateral (radial) epicondylitis, so-called “tennis elbow.” Medial (ulnar) epicondylitis (“golfer’s elbow”) is rarer and is caused by flexor overuse.

Radial styloiditis is characterized by pain at the tendinous origins of the extensor carpi radialis muscles on the styloid process of the radius. Ulnar styloiditis is the analogous condition on the styloid process of the ulna. Both are varieties of tendonitis, similar to others occurring elsewhere in the body.

Note

In these conditions, pain in the arm and shoulder is due to a lesion affecting sensory nerve fibers, either in the brachial plexus or in the peripheral nerves. The lesion may be either mechanical (common) or infectious/inflammatory (less common).

Compression of the brachial plexus at the thoracic outlet can occur at any of several anatomic bottlenecks (the scalene hiatus, the costoclavicular passage, or the subacromial space). This generally occurs, however, only when an additional pathogenic factor is present, such as a cervical rib, fibrous band, or anomaly of the scalene attachments, or exogenous pressure. The corresponding clinical syndromes are discussed in Chapter ▶ 13.

Brachial plexus tumors sometimes cause progressively worsening arm pain that becomes very severe within a matter of weeks. Pancoast tumors of the lung apex (described in section ▶ 13.2.1) are a well-known cause.

Neuralgic shoulder amyotrophy (discussed in section ▶ 13.2.2) also causes acute, severe pain.

Compressive neuropathies can cause severe, intractable pain in the upper limb. These conditions are described in section ▶ 13.2.3. The more common types are sulcus ulnaris syndrome and carpal tunnel syndrome, which causes arm pain, especially at night (brachialgia paraesthetica nocturna).

Note

Stenosis or occlusion of an artery supplying the shoulder girdle or the upper limb can cause pain, sometimes only during or after movement of the limb. Venous occlusion can cause pain as well.