Chapter 21

The Great Outdoors: Sukkot

In This Chapter

Building a sukkah

Building a sukkah

Rejoicing in the Torah

Rejoicing in the Torah

Most people associate Judaism with the “great indoors.” Jews usually pray inside synagogues or at home, and religious American Jews have the reputation of being indoor types who’d rather face a book than the sun. We hate to disappoint you, but Judaism not only embraces the great outdoors but in many ways is inextricably tied to it. Case in point: the holiday of Sukkot.

Over 3,000 years old (making it among the oldest of Jewish holidays, likely predating Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur), Sukkot reflects an earlier festival celebrating the gathering of the autumn crops. Like many Jewish holidays, Sukkot has several names, including Hag ha-Asif (“Festival of Ingathering”) and Z’man Simkhateinu (“Time of our Joy”). Over the millennia, Sukkot gained additional historical and spiritual meaning, but it never lost its connection to agriculture and the land.

A Jewish Thanksgiving

Five days after Yom Kippur (see Chapter 20), exactly half a year away from Passover (see Chapter 25), Sukkot is a weeklong festival that begins on the full moon of the month of Tishrei. The festival actually lasts eight or nine days, though, because Jews tack on Sh’mini Atzeret and Simkhat Torah (we discuss these days later in this chapter).

The Bible notes that King Solomon dedicated the First Temple (see Chapter 12)on Sukkot. Then, during the Temple period, Sukkot was one of three pilgrimage festivals — along with Passover and Shavuot — during which Jews would travel from all over to visit Jerusalem. Sukkot was traditionally the most festive and jubilant of the holidays, a time of feasting, drinking, singing, and ecstatic dancing in the streets and in the Temple. To this day, Sukkot remains one of the most important Jewish holidays.

Giving thanks

Every culture and every major religion has a day or a time of year for giving thanks. You might say that Sukkot is the “Jewish Thanksgiving,” during which Jews offer praise and thanks for the abundant harvest. Sukkot falls near the Autumnal Equinox, and the holiday symbolizes the turning point toward winter. On the day after Sukkot, called Sh’mini Atzeret (which we discuss later in this chapter), Jews say prayers for fertile rains to fall throughout the desert land of Israel.

While Sukkot (which people sometimes call Ha-Khag, or “The Festival”) has plenty of ritual associated with it, the liturgy itself is quite similar to that of a regular Shabbat service. Sure, congregants say some additional prayers, and the cantor reads aloud the entire book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet in Hebrew) on the Shabbat during Sukkot. However, unlike the High Holidays, no special events require extra attendance at a synagogue, and while some people do perform some of the Sukkot rituals at a synagogue (like waving the lulav, which we talk about in a moment), many others honor the entire holiday at home.

Getting outdoorsy: Building a sukkah

The most visible tradition on Sukkot is building a sukkah — which is translated as “hut,” “booth,” or “tabernacle” — somewhere outdoors, usually in a backyard, a park, or outside the synagogue. (The plural of sukkah is — surprise! — sukkot.) The Bible states that people should live in the sukkah for the entire week of Sukkot, but the definition of “live” is complicated, and almost no one actually sleeps in them.

These huts may have originally represented the temporary shelters people lived in during the harvest. However, the Bible explains that Jews build a sukkah to remember the huts that the Hebrews lived in during the 40 years in the wilderness after the exodus from Egypt (see Chapter 11). The temporary dwelling reminds people not to get too attached to physical comforts, and it also renews the attachment people have to the natural cycles of the planet. On a metaphorical level, the sukkah reflects another temporary dwelling: the body, which houses the soul.

How to Sukkot

Unlike the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, which aren’t the most child-friendly days of the Jewish year, Sukkot is a fun-filled family event. Whether it’s building the sukkah, waving the lulav, or picnicking in the sukkah and hoping the bees don’t find you, kids of all ages enjoy taking advantage of all that Sukkot has to offer.

A sukkah born every minute

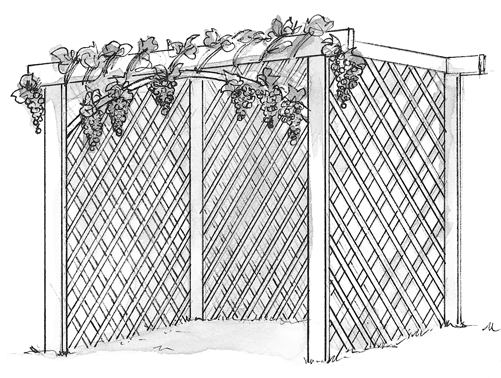

A sukkah (see Figure 21-1) is a temporary hut that people typically build in their backyard — though people in apartment buildings often build them on the roof or even on a balcony (see Getting outdoorsy: Building a sukkah for more information). The structure is traditionally assembled before Sukkot begins. Here are the rules for creating a “kosher” sukkah:

The structure needs four sides, though one or more of them can be the wall of a house (and one side can even be completely open, like a giant door). All the walls must be strong enough to withstand reasonable wind. The sukkah needs some sort of entranceway, of course, and some even have elaborate doorways and even windows.

The structure needs four sides, though one or more of them can be the wall of a house (and one side can even be completely open, like a giant door). All the walls must be strong enough to withstand reasonable wind. The sukkah needs some sort of entranceway, of course, and some even have elaborate doorways and even windows.

The roof must be made of plant material, like branches, bamboo, cut wood, or big leaves, as long as the material is no longer attached to a plant. The roof can’t be solid — that is, you have to be able to see the stars through it — but it must provide more shade than sunlight.

The roof must be made of plant material, like branches, bamboo, cut wood, or big leaves, as long as the material is no longer attached to a plant. The roof can’t be solid — that is, you have to be able to see the stars through it — but it must provide more shade than sunlight.

Many Jews decorate the sukkah, so let your kids go nuts hanging fruit (real or dried), ornaments, colored paper cut into funky shapes, pictures they’ve drawn, and anything else that adds to the fun. Note that some folks have just the opposite custom, leaving the whole thing completely unadorned.

Many Jews decorate the sukkah, so let your kids go nuts hanging fruit (real or dried), ornaments, colored paper cut into funky shapes, pictures they’ve drawn, and anything else that adds to the fun. Note that some folks have just the opposite custom, leaving the whole thing completely unadorned.

The sukkah can’t be entirely covered by something else, so no fair building it underneath a tree or in your carport. Well, to be precise, you’re allowed to build it under something as long as some reasonable amount remains uncovered.

The sukkah can’t be entirely covered by something else, so no fair building it underneath a tree or in your carport. Well, to be precise, you’re allowed to build it under something as long as some reasonable amount remains uncovered.

Although the classified ads in any Jewish magazine or newspaper offer commercial sukkot that you can buy and easily assemble just before the holiday, we think it’s more fun to design and build our own. Some people build the basic structure with a bunch of two-by-fours, some rope, and some cement cinder blocks. Each year, Ted’s congregation builds a community sukkah using 16 inexpensive, rectangular trellises from a nursery held together with plastic ties from a hardware store over a basic foundation made by two-by-fours.

Figure 21-1: Building a sukkah is a fun project for the whole family.

The sukkah should be large enough that you can sit, eat, and sleep in it for the entire week of Sukkot. Jews often entertain guests in the sukkah, study Torah in it, play music, and just basically hang out there. Of course, while this might be reasonable in a very safe neighborhood or in Israel (where it’s still relatively warm during Sukkot), those of us in colder climates might find ourselves in a chilly rainstorm, considering burning the sukkah for heat!

Most Jews limit their sukkah activities to saying blessings over the candles, wine, and bread (see Appendix B), as well as the blessing over the sukkah each time they enter it:

Barukh atah Adonai, Eloheynu melekh ha-olam asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu leysheyv ba-sukkah.

Blessed are you, Eternal One our God, Universal Ruling Presence, Who makes us holy through Your mitzvot [paths of holiness], and gives us this mitzvah of sitting in the sukkah.

Waving the lulav and etrog

Celebrating Sukkot involves using a couple of special props during the morning services on each day of the holiday (see Figure 21-2):

Lulav: A collection of freshly cut branches — a palm frond, two willow branches, and three myrtle branches — that are secured together.

Lulav: A collection of freshly cut branches — a palm frond, two willow branches, and three myrtle branches — that are secured together.

Etrog: A citrus fruit, also known as citron, that looks sort of like a big lemon but smells and tastes different, and has a much thicker rind.

Etrog: A citrus fruit, also known as citron, that looks sort of like a big lemon but smells and tastes different, and has a much thicker rind.

Rabbis offer a number of different interpretations for why these four plants are used in particular, including the following:

The palm frond is tall and straight like the human spine, the etrog is shaped like the heart, the willow leaves are like lips, and the myrtle leaves are like eyes. Therefore, using all four species is like involving your whole body in the ritual.

The palm frond is tall and straight like the human spine, the etrog is shaped like the heart, the willow leaves are like lips, and the myrtle leaves are like eyes. Therefore, using all four species is like involving your whole body in the ritual.

The etrog has both a pleasant taste and aroma, symbolizing a person who is both learned and who does good deeds. The palm tree has fruit (dates) that taste good but have no aroma, symbolizing a person who is learned but does no good deeds. The myrtle has a pleasant aroma but no taste, so it is like someone who does good deeds but is not learned. Finally, the willow has neither taste nor smell, a symbol of someone who is neither learned nor does good deeds. Some say that all four types of people are important in a community.

The etrog has both a pleasant taste and aroma, symbolizing a person who is both learned and who does good deeds. The palm tree has fruit (dates) that taste good but have no aroma, symbolizing a person who is learned but does no good deeds. The myrtle has a pleasant aroma but no taste, so it is like someone who does good deeds but is not learned. Finally, the willow has neither taste nor smell, a symbol of someone who is neither learned nor does good deeds. Some say that all four types of people are important in a community.

Figure 21-2: The lulav and etrog.

These props are used in a ritual dance that involves shaking the lulav and etrog in various directions. Here’s how to perform the dance:

1. Facing east, hold the lulav in your right hand and the etrog in your left, with both of your hands close together.

2. Extend the lulav forward and then pull it back while shaking both the lulav and etrog.

3. While still facing east, point the lulav and etrog to the north (to the right) and repeat the extending, pulling back, and shaking, almost as if you’re drawing in a fish on a fishing line.

4. Repeat the whole dance to the west (behind), the south (to the left), to the heavens (up), and finally down toward the earth.

Some teachers note that this ritual is a reminder that God is everywhere, and it also honors the unique “energies” that each direction symbolizes:

East is the land of the rising sun, and it symbolizes new possibilities, beginnings, and awakenings.

East is the land of the rising sun, and it symbolizes new possibilities, beginnings, and awakenings.

North is the direction of clarity, rationality, and the coolness of intellect.

North is the direction of clarity, rationality, and the coolness of intellect.

West is the land of the setting sun and journeys completed.

West is the land of the setting sun and journeys completed.

South is the direction of warmth, emotion, verdant growth, and sensual energy.

South is the direction of warmth, emotion, verdant growth, and sensual energy.

Up is the land of dreams and visions, the land of spirituality.

Up is the land of dreams and visions, the land of spirituality.

Down is the connection to the earth, and recognition of people’s environmental responsibilities.

Down is the connection to the earth, and recognition of people’s environmental responsibilities.

When Sukkot is over, consider saving these plants for other purposes. For example, some Jews use the palm frond as a giant “feather” with which to hunt for chametz just before Passover (see Chapter 25). Or you can save the lulav and burn it with the chametz. Another custom is to press whole cloves into the etrog and then use it as a “spice box” during the Havdalah ceremony after Shabbat (see Chapter 18).

Sh’mini Atzeret

The day after Sukkot, called Sh’mini Atzeret (“the eighth day of solemn assembly”), tends to be under-appreciated by many Jews. Sh’mini Atzeret also means “setting a boundary” or “restraining,” and there’s no doubt that Sh’mini Atzeret acts as a way to move through the revelry and hoopla of the previous week and focus attention on the serious prospect of the coming winter.

Sh’mini Atzeret and Simchat Torah (see the following section), even though they are officially separate holidays, are still considered the final days of the festival season and have the status of a chag, a festival on which no work is done.

After a week sitting in the sukkah hoping that it won’t rain, on Sh’mini Atzeret Jews recite a prayer called geshem (“rain”), wishing for a generous downpour to start the winter off properly and ensure that the land will be fertile, the crops will grow, and the people will eat.

In many traditional communities, the ceremonies actually begin a day earlier, on the seventh day of Sukkot, called Hoshanah Rabbah. (Hoshanah is the same word as the English “Hosanah,” meaning “help, I pray.” Rabbah means “great.”) On Hoshanah Rabbah, Jews circle the bimah (the reading stand at the front of the synagogue) seven times as they beat the ground with willow branches. Many see this act as a talisman for making the earth fertile or for casting off old sins.

Simkhat Torah

Sukkot, Chanukkah, and Purim are all joyful, but Simkhat Torah — which traditionally falls the day after Sh’mini Atzeret (see the previous section) — is deeply and expansively joyful. Indeed, Simkhat Torah means “Rejoicing in the Torah.” On Shavuot, Jews honor the giving of Torah, and on Simkhat Torah, Jews celebrate the Torah itself as they complete the yearly reading cycle and then immediately begin the cycle again (see Chapter 3).

Simkhat Torah, which didn’t exist in biblical days, has no formal liturgy or ritual, but customs have certainly evolved for this day over the years:

Almost every congregation reads the last section of the Book of Deuteronomy (the end of the five books of Moses) and the first section of the Book of Genesis. (The evening service on Simkhat Torah is the only time in traditional communities when the Torah can be read at night.) Whoever is called to read the last lines of Deuteronomy is called the Chatan Torah (“Groom of the Torah,” pronounced kha-tan To-rah), and the reader of the beginning of Genesis is called the Chatan Bereshit (“The Groom of Creation”). In communities where both men and women are called to the Torah, there might be a Kallah Torah (“Bride of the Torah”) or a Kallah Bereshit. Traditionally, the entire congregation is called up to the bimah for aliyot (to say the prayers before and after Torah readings) on Simkhat Torah.

Almost every congregation reads the last section of the Book of Deuteronomy (the end of the five books of Moses) and the first section of the Book of Genesis. (The evening service on Simkhat Torah is the only time in traditional communities when the Torah can be read at night.) Whoever is called to read the last lines of Deuteronomy is called the Chatan Torah (“Groom of the Torah,” pronounced kha-tan To-rah), and the reader of the beginning of Genesis is called the Chatan Bereshit (“The Groom of Creation”). In communities where both men and women are called to the Torah, there might be a Kallah Torah (“Bride of the Torah”) or a Kallah Bereshit. Traditionally, the entire congregation is called up to the bimah for aliyot (to say the prayers before and after Torah readings) on Simkhat Torah.

Some synagogues celebrate the yearly cycle of reading by unrolling the entire Torah scroll and forming it into a giant circle so that the end and the beginning of Torah are next to one another for the readings. Children stand in the center of the circle of Torah, as their parents and other adults lovingly hold the scroll, allowing everyone to experience a sense of shared holiness.

Some synagogues celebrate the yearly cycle of reading by unrolling the entire Torah scroll and forming it into a giant circle so that the end and the beginning of Torah are next to one another for the readings. Children stand in the center of the circle of Torah, as their parents and other adults lovingly hold the scroll, allowing everyone to experience a sense of shared holiness.

Everyone is so focused on the joyful singing and dancing that even in many Orthodox congregations the men, women, and children all sit and sing together.

Everyone is so focused on the joyful singing and dancing that even in many Orthodox congregations the men, women, and children all sit and sing together.

People hold Torah scrolls while parading around the sanctuary seven times (called hakafot), allowing participants to celebrate and perhaps even dance with the Torah while everyone sings. This part of the celebration can become so frenzied that after the seven circuits, everyone may spill out into the street like a big party.

People hold Torah scrolls while parading around the sanctuary seven times (called hakafot), allowing participants to celebrate and perhaps even dance with the Torah while everyone sings. This part of the celebration can become so frenzied that after the seven circuits, everyone may spill out into the street like a big party.

Ask a child what happens on Simkhat Torah and you’ll get a definitive answer: “We get candy!” Judaism has a long tradition of associating sweets with sweet occasions. In Reform congregations this holiday is also a time for Consecration, during which young children are formally welcomed into the community as they began their religious education.

Ask a child what happens on Simkhat Torah and you’ll get a definitive answer: “We get candy!” Judaism has a long tradition of associating sweets with sweet occasions. In Reform congregations this holiday is also a time for Consecration, during which young children are formally welcomed into the community as they began their religious education.

Most Jews are no longer farmers, but that doesn’t mean the harvest metaphor no longer works. During Sukkot, you can think about the emotional and spiritual work completed over Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, like you’re harvesting the benefits of repentance and forgiveness.

Most Jews are no longer farmers, but that doesn’t mean the harvest metaphor no longer works. During Sukkot, you can think about the emotional and spiritual work completed over Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, like you’re harvesting the benefits of repentance and forgiveness. When selecting an etrog, make sure the stub (

When selecting an etrog, make sure the stub (