The question ‘Do UFOs exist?’ is no longer an issue for David Hastings, a veteran pilot with 40 years’ flying experience that began with service in the RAF. Like many civilian pilots and some military aircrew, a dramatic personal sighting left him in no doubt the answer to that question is an emphatic ‘Yes!’. The event that convinced Hastings happened on the final leg of an epic trans-American trip. On the afternoon of 9 September 1985 he and his experienced co-pilot had just left the Grand Canyon behind them in their twin-engined Cessna Skymaster. As they approached restricted airspace at 10,500 ft above the Mojave Desert, ground radar reported: ‘no conflicting traffic’.

Hastings recently described what happened next, saying: ‘You can imagine our surprise when a small dot appeared at our same altitude and in our 12 o’clock which rapidly grew in size. We were both convinced that we were about to have a head-on mid-air collision with a high-speed military jet aircraft and both pushed hard down on the control columns, expecting a tremendous bang and the end of our flight.’1

At that point a huge black shadow passed over the cockpit. It vanished without making a sound and left no turbulence behind it. The two shaken pilots turned and asked each other: ‘What the hell was that?’. A check with ground control told them that still nothing was showing on radar but as minutes passed and tension grew both men were gripped by the feeling that something was flying in formation alongside them. Hastings then remembered his camera in the back of the plane. Unstrapping himself, he grabbed it, taking two shots from the port windows before the feeling passed, leaving them ‘shaken and puzzled’.

When the film was developed, the pair were staggered by the results. While the first snap showed just the Cessna’s port wing and the mountains below, the second showed a dark, elongated object with what appears to be some form of heat or exhaust emerging from its underside. Later in the trans-American trip, a friend in the US Navy asked to borrow the photograph. All he would say on returning it was ‘no comment’.

This reaction is given another dimension when you consider where the sighting occurred. The two men’s trip had taken them past restricted military airspace and close to Edwards Air Force Base and the secret Nevada Test and Training Range that contains Groom Lake. Both of these fall within the mysterious region known as ‘Area 51’ and both have, over the years, been home to a number of ‘black project’ programmes such as the Stealth fighter and the B-2 flying wing. Could it be that Hastings’ near-miss had been with some advanced top secret military aircraft? Hastings, for one, remains unconvinced by this idea and is certain the object he saw that day was not man-made. ‘Having flown for over 40 years like most pilots I have always accepted UFOs,’ he told me. ‘You only have to look up at the sky at night to realize that we cannot be the only planet that supports life.’

Two photographs taken by British pilot David Hastings during a near-miss over the Mojave Desert near the mysterious ‘Area 51’ on 9 September 1985. The second shows a mysterious elongated object. UFO or experimental aircraft?

In retirement, David Hastings felt confident writing and talking about his experience. For a pilot this is actually quite unusual. Flying aircraft is a responsible job and, quite understandably, few wish to be known as ‘the one who sees flying saucers’, however sure they might be of what they have seen. The late Graham Sheppard, a British Airways pilot who made two sightings of his own and famously spoke out on the issue, estimated that some 10 per cent of aircrew had some form of UFO experience during their career. In 1999 he said: ‘I must have spoken to 20 pilots who have had sightings but all are adamant they do not want publicity.’2

One of the earliest UFO sightings made by a civilian aircrew remains one of the most unusual even though it has been adequately explained. It was reported by the crew and passengers of a BOAC Stratocruiser during a flight from New York to London in June 1954. The captain, James Howard, was interviewed live by BBC news on landing and his story was widely reported by national newspapers who treated it as a reliable report from a credible witness. Captain Howard described how he and co-pilot Lee Boyd watched a group of strange objects for 18 minutes as they cruised at 19,000 ft above Goose Bay in Labrador. When first spotted, shortly after 9.00 pm, the sun was low on the horizon and six small dark objects were visible below the port beam. As they climbed, the crew saw these were arranged on either side of a large ‘jellyfish-shaped’ object that was constantly changing form. Howard contacted Goose Bay by radio and an F-94 fighter was diverted to intercept them, but before it reached the scene, ‘the small objects seemed to enter the larger [UFO], and then the big one shrank’.

Howard’s report was reported to the Air Ministry and investigated by Project Blue Book, who decided it was possible the UFOs were a mirage of a bright planet created by unusual weather conditions. However, when pressed by the BBC, Captain Howard said there was ‘no question that this was not an illusion… and that it was being intelligently handled’.3 In 2010 UFOlogist Martin Shough carried out a thorough cold case review of the evidence, including the crew’s original statements and contemporary weather data. His report concludes that Captain Howard and his crew did see an unusual mirage. And far from being rare, he discovered this sighting was just one of ‘an unrecognised class of very similar mirage observations from aircraft’ that may have given rise to other classic UFO reports in the past.4

UFO reports from aircrew are regarded as particularly persuasive evidence, as pilots are trained observers who often have a great number of years of flying experience. Captain Howard’s sighting was the first of many by civilian pilots to receive wide publicity in Britain, but until 1968 there was no formal procedure whereby aircrew could file their reports directly with the Ministry of Defence. As a result news of some incidents never reached the MoD or arrived so late that investigation was impossible, as vital evidence, such as radar tapes, had been erased. But as a direct result of the UFO flap of 1967 (see p. 75), the MoD was forced to improve the system whereby they received UFO reports from a range of official sources such as the police and airports.

From January 1968 all air traffic control centres were instructed to report any unusual sightings directly to RAF West Drayton so they could be investigated quickly. A version of these instructions remain part of the Manual of Air Traffic Control, the service’s reference book, to this day (see p. 177). In addition, the Civil Aviation Authority has, since 1976, kept a record of UFO incidents reported by British aircrew alongside a range of other more commonplace hazards. Known as Mandatory Occurrence Reports, these range from other aircraft that stray from their flight plan to incidents involving microlites, gliders and hot-air balloons. In those cases where crews report a near-miss with another aircraft, an independent team of experts is called in to investigate. The task of the Joint Air-miss Working Group, which is made up of both military and civilian aviation specialists, is to assess the possibility of a collision and, where possible, take steps to reduce future risks.

But when a near-miss is reported as having involved a UFO the team has found it difficult to reach any definitive conclusions, as such incidents cannot be neatly pigeonholed into any tangible hazard category. As a result, the potential risks posed by UFOs – as in something real but unknown – have tended to be downplayed by both the MoD and the Joint Airmiss Working Group, which have dealt with unexplained incidents on a case-by-case basis.

The MoD’s informal policy of ignoring potential hazards to aircraft presented by UFOs is illustrated by files at The National Archives that cover a 1977 review of policy. During a frank exchange of views within the MoD, an intelligence officer said reports of UFOs in the busy air lines over the English Channel raised ‘flight safety questions’. Responding to his concerns, Wing Commander D. B. Hamley of the RAF’s Inspectorate of Flight Safety admitted the MoD’s attitude to UFOs was ‘ostrich-like’, adding: ‘If we do not look, it will go away. If it does not officially exist, I cannot get terribly worked up if someone sees one, in the “busy air lanes over the Channel” or anywhere else.’5

This ‘ostrich-like’ official attitude towards reports of near-misses between aircraft and UFOs continued into the 1990s when a spate of disturbing incidents occurred over the British Isles. Although many of these were reported by the media at the time, full details of the official investigations and their findings did not emerge until the relevant MoD files were opened by The National Archives from 2008.

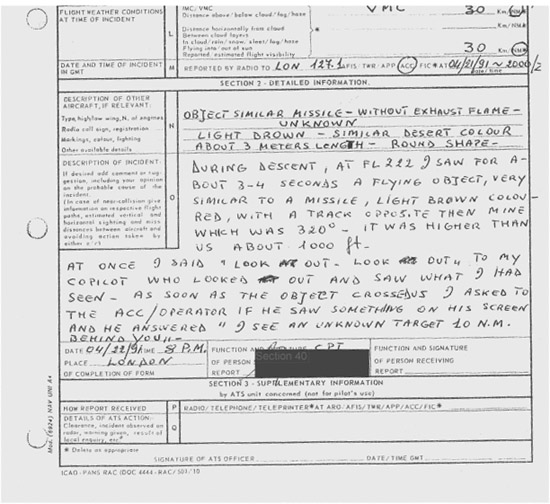

The most surprising fact to emerge was that the most dramatic encounter recorded in the files was never subject to a full ‘airmiss’ inquiry. The files reveal this report was investigated internally by the MoD, although the captain reported it officially as a near-collision with an unidentified flying object. On 21 April 1991 Captain Achille Zaghetti, the pilot of Alitalia Flight AZ 284 carrying 57 passengers en route from Milan, was on his final descent into Heathrow Airport. The jet had crossed the Channel coast and was around 6 miles west of Lydd in Kent and under London Air Traffic control. It was around 8.00 pm and still light when, according to the captain’s handwritten report: ‘during descent, at [22,200 ft] I saw for about 3–4 seconds a flying object, very similar to a missile, light brown coloured… with a track opposite than mine… It was higher than us, about 1000 ft. At once I said: “Look Out! Look Out!” to my co-pilot who looked out and saw what I had seen. As soon as the object crossed us I asked [Heathrow] if he saw something on his screen and he answered “I see an unknown target 10 [nautical miles] behind you.”6

The ‘near collision’ report made by Captain Achille Zaghetti, the pilot of Alitalia Flight AZ 284, to the Civil Aviation Authority following his close encounter with a missile-shaped UFO over Lydd, Kent, in April 1991. DEFE 24/1923/1.

The air traffic controller’s report confirmed that ‘at the time of the incident a primary response was observed behind [the aircraft] tracking northeast’, but checks with coastguards, police and the army failed to identify it. A replay of the radar tapes revealed the track of the ‘primary contact’ had been recorded on film and scribbled on one of the sheets are the words: ‘Possible slow-moving target – Cruise Missile?’.

The Sunday Times reported the outcome of inquiries that had been made by the MoD to trace the origin of the mysterious ‘missile’ and quoted an aviation expert who said it was possible the object could have been a stray military target or ‘drone’ used for air defence practice. Initially, it certainly seemed possible that whatever the captain had seen came from the nearby army ranges at Lydd or from a ship at sea. However, the file on the incident makes it clear that the MoD soon ruled this out.

Their investigation ended two months later when it became apparent they were unable to explain the incident. The MoD’s bland conclusion simply read: ‘In the absence of any clear evidence which could be used to identify the object it is our intention to treat this sighting like that of any other Unidentified Flying Object and therefore we will not be able to undertake any further investigation into the sighting.’7

This incident was just the tip of a small iceberg. During the summer of 1991 there were a further six UFO reports made by airline crews and passengers but only one of these was subject to a detailed investigation by the ‘airmiss’ working group.

On 15 July the crew of a Britannia Airways Boeing 737 returning from Greece and descending into Gatwick under London control at 14,000 ft saw ‘a small, black lozenge-shaped object’ zoom past at high speed just 100 yds off the port side of the aircraft. Gatwick confirmed a ‘primary contact’ was visible on radar 10 nautical miles behind the 737 moving at a speed estimated at 120 mph. Immediately air traffic control warned a following aircraft which made ‘avoiding turns to the left to avoid the [UFO], which had appeared to change heading towards it, but its pilot reported seeing nothing’. This incident could not be ignored and a formal ‘airmiss’ investigation was opened. In their report, completed in April 1992, the working group said they ‘were unsure what damage could have occurred had the object struck the 737; the general opinion was that there had been a possible risk of collision.’8

The working group admitted they could not explain the incident but suggested the ‘unidentified object’ that came so close to the 737 might have been an escaped balloon. Shortly after their report was completed, the Civil Aviation Authority’s in-house magazine, Airways, published a photograph of a toy balloon called the ‘UFO Solar’. Manufactured in Europe and costing just 99p, when inflated the balloon was 10 ft in length, black, lozenge-shaped and – according to the makers – capable of reaching ‘extraordinary altitudes’ up to 30,000 ft. It cannot be doubted the appearance of this balloon fits some aspects of the crew’s story, but as in many UFO incidents it is never possible to say conclusively: ‘case closed’.

Balloons are unlikely to have been responsible for another airmiss incident reported by a British Airways crew, this time near Manchester Airport. At 6.45 pm on 6 January 1995 their Boeing 737, carrying 60 passengers from Milan, had descended to 4,000 ft above the Peak District hills in preparation for landing. The 737 was cruising just above the clouds and visibility was at least 10 miles when, without warning, a glowing wedge-shaped object appeared following a course directly towards the plane.

Captain Roger Wills had this exchange with air traffic controllers:

‘B-737 (6.48 pm): |

… we just had something go down the [right hand side] just above us very fast. |

Manchester: |

Well there’s nothing on radar. Was it… an aircraft? |

Well, it had lights, it went down the starboard side very quick. |

|

Manchester: |

And above you? |

B737: |

… just slightly above us, yeah.’9 |

Captain Wills told the working group this UFO was in sight for just two seconds and created no noise or air displacement as it whizzed past. He said it was illuminated with a number of small lights, making it look like a Christmas tree. The first officer, Mark Stuart, told the Airmiss investigators he instinctively ducked when he saw: ‘a dark object pass down the right-hand side of the aircraft at high speed; it was wedge-shaped with what could have been a black stripe down the side… he felt sure that what he saw was a solid object – not a bird, balloon or kite.’

One of many reports by civilian aircrew of near-misses with UFOs; this example was reported to MoD by the captain of an airliner flying over the South Atlantic on 5 September 1986. DEFE 24/1924/1

The investigation was unable to trace any civilian or military aircraft and ruled out a stray hang-glider or night-flying microlite as being ‘extremely unlikely’. But although they could not identify the object, the working group pointed out that almost all unusual sightings of this kind ‘can be explained by a range of known natural phenomena’.

One possibility independently proposed by astronomer Ian Ridpath and UFOlogist Jenny Randles was a fireball meteor. They pointed out that it was not unusual for experienced pilots to misidentify such bright fireballs as they tend to appear and disappear suddenly, without warning. In darkness, with no reference points, it would be easy to conclude an object was alarmingly close to their aircraft when in fact it was many miles away, burning up in the upper atmosphere.

Nevertheless, the airmiss working group commended the two pilots for their courage in submitting their report. They noted that sightings by aircrew: ‘are often the object of derision, but the Group hopes that this example will encourage pilots who experience unusual sightings to report them without fear of ridicule.’ Their report, published in February 1996, decided there was no doubt that both: ‘saw an object… that was of sufficient significance to prompt an airmiss report. Unfortunately the nature and identity of this object remains unknown. To speculate about extraterrestrial activity, fascinating though it may be, is not within the Group’s remit and must be left to those whose interest lies in this field.’10

Near collisions with unidentified objects, such as those reported by pilots like David Hastings and Achille Zaghetti, highlight the frequent links between the UFO phenomenon and military secrets. The most recent MoD files released by The National Archives contain many hints that certain types of experimental military aircraft have been seen and reported as UFOs in recent years.

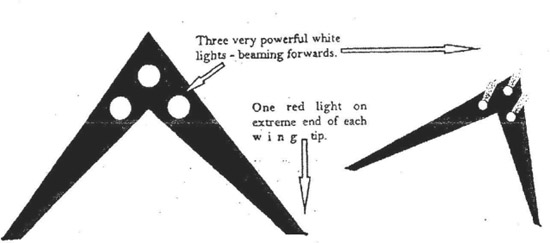

For example, in 2001 a resident of Stroud contacted his MP, David Drew, to report his sighting of ‘a very unusual aircraft’ flying above the Gloucestershire countryside. The letter says he was out walking at 9.30 pm on 3 September 2000 when his attention was drawn to a large object ‘looming up over the skyline’. He continued: ‘This was no ordinary aircraft as it was black all over with no tail section that I could determine and it had three very powerful beams of light, lighting up ahead of the aircraft. All three lights emanated from underneath the aircraft from dome-like globes and were set in a triangular shape. The only other lights were extremely small red lights on the extreme tips of each wing, the wings… were extremely long and much larger than any plane I had seen before… The engines were very quiet, something like Rolls Royce turbines… [and] the plane passed over me and to my right side heading in the direction of Bisley.’11

A drawing of the ‘unusual aircraft’ sent to the MP by the witness (see p. 140), so resembled the appearance of American ‘Stealth’ aircraft that UFO desk officer Linda Unwin decided to check with the US 3rd Air Force at RAF Mildenhall in Suffolk. They said there was ‘no unusual US aircraft activity over [the] UK’ at the relevant time.

This was just one of many similar sightings of silent, triangular-shaped UFOs reported from parts of Britain and Europe since the end of the Cold War. In 1990 sightings by police officers and civilians became so frequent in Belgium that on one occasion the Belgian air force scrambled F-16 fighters to investigate. At a subsequent press conference General Wilfried de Brouwer, Chief of Operations with the Belgian Air Force, admitted their pilots had detected something on radar that remained unexplained.12 Were these nocturnal craft, as many suspected at the time, a new American stealth aircraft operating secretly from RAF bases in Britain, or were they a UK-designed prototype developed using cutting-edge technology?

A sketch featuring a ‘flying triangle’ UFO seen in Gloucestershire during 2000. Reports of huge stealth-like UFOs became popular from the late 1970s. Coincidentally, massive wedge-shaped Imperial Star Destroyer spaceships appear in the science fiction film Star Wars (1977) and its sequels. DEFE 24/2034/1

The Cold War came to an end with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, but mutual suspicions continued on both sides of the former Iron Curtain. Old habits die hard and during the decade that followed, even former allies began to suspect each other of using high performance aircraft to spy upon their territory. At the same time, there was a natural temptation on behalf of some aviation journalists and their sources in the defence industry to attribute impressive UFO sightings to advanced ‘black projects’. In many cases, the truth often turned out to be more mundane.

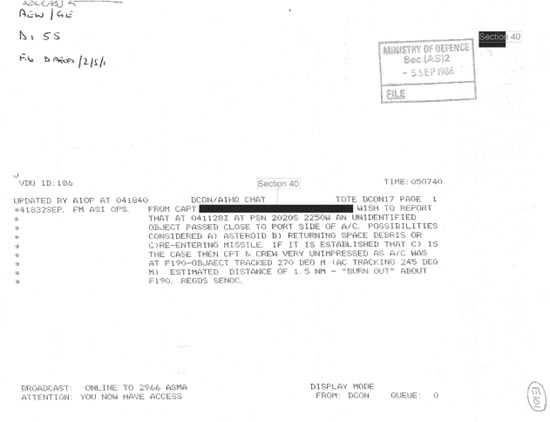

In 1990 the crews of six RAF Tornado jets were taking part in an exercise at 27,000 ft over Germany on the evening of 5 November under the control of Dutch military radar. As darkness fell at 6.00 pm their aircraft were suddenly overtaken by a large flying object. In a military signal to RAF West Drayton, the RAF flight commander described how the UFO ‘went into our 12 o’clock [position] and accelerated away’. He described seeing an object surrounded by ‘five to six white steady lights [and] one blue steady light [with] contrails from [the] blue area’. The crews discussed their experience and decided the UFO could have been the American Stealth fighter.

Although still a military secret, this aircraft was frequently in the news after photographs showing its distinctive triangular profile were declassified. Commenting upon their report, an intelligence officer wrote: ‘Clearly the incident happened and clearly the pilots saw what they believe (with hindsight) to be a Stealth aircraft [but] I doubt very much if the USAF or even the Soviet Air Force (if they were flying) would admit to anything.’13

A file opened by The National Archives in 2009 reveals the MoD did not investigate the Tornado crews’ report because it occurred outside UK airspace, but officials evidently suspected some type of ‘black project’ aircraft was involved. If they had made further inquiries they would have discovered other sightings had been made by aircrews elsewhere in Europe at the same date and time, some of which described loud bangs as the formation of lights moved through the sky. Space tracking stations identified these lights as the debris from a Soviet rocket which had earlier launched the Gorizont 21 communications satellite into orbit.

The report received by the MoD from the pilots of a group of RAF Tornados who reported being overtaken by a UFO whilst on exercise over Germany in November 1990. They suspected the UFO was the then secret United States Air Force Stealth fighter. DEFE 31/180/1

The Tornado pilot who reported the sighting remains unconvinced by this explanation. In a 2003 letter to UFOlogist Richard Foxhall, he says: ‘This was definitely not a Russian satellite – I’m 100% certain of that… the UFO did not look like any aircraft that I know to be in service with any air force either today or at the time… .’14

Alongside this can be placed the events that occurred in the early hours of 30/31 March 1993 when another UFO flap set phones jangling in the small Whitehall office that dealt with unusual sightings. Files released by The National Archives in 2009 show the MoD alone received more than 30 separate sighting reports on this night, including accounts from police officers in Devon and Cornwall who saw ‘two very bright lights hovering at about 2,000 ft (600 m)’. Another report was filed by a military patrol at RAF Cosford, near Wolverhampton, who saw ‘two bright lights in the sky above the airfield… flying at great velocity’. Their report described the lights as silent, ‘circular in shape and [they] gave off no beam… creamy white in colour and constant in size and shape’. A slight red glow could be seen from the rear of the lights before they disappeared over the horizon in a southeasterly direction. Most of the other witnesses described seeing a formation of two or three white lights with vapour trails moving swiftly across the sky in a similar direction. Some claimed the lights appeared in a triangular formation.

The MoD’s UFO desk officer, Nick Pope, was so worried by this flap he asked the RAF to examine radar tapes from the night in question, but nothing unusual could be seen. He later briefed the head of Sec(AS) that if a UFO really was operating over the UK ‘without being detected on radar this would… be of considerable defence significance’ and he recommended that ‘we investigate further’.

It later emerged that most of these sightings could be traced to the decay into Earth’s atmosphere of a Russian rocket used to launch the Cosmos 2238 spy satellite into orbit. This explanation was confirmed when news arrived of similar sightings made in Ireland and France on the same evening. When Pope was sent a copy of a French Space Agency report on the sightings in 1994 he conceded that ‘it is clear that most of the UFO sightings that occurred on the night in question can be attributed to this event’.15 UK astronomer Gary Anthony and NASA space debris expert Dr Nick Johnson have since produced a computer simulation of the trajectory followed by the debris that neatly explains the majority of sightings reported that night.

But before full details of this explanation had emerged, some MoD officials appear to have convinced themselves that the ‘Cosford flap’, as it became known, was caused by a genuine UFO. On 22 April the head of the UFO desk took matters a step further by sending a memo to the Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Sir Anthony Bagnall, that claimed: ‘there would seem to be some evidence… that an unidentified object (or objects) of unknown origin was operating over the UK’. He added: ‘If there has been some activity of US origins which is known to a limited circle in MoD and is not being acknowledged it is difficult to investigate further.’16 Bagnall decided to take no further action and soon afterwards Pope’s superior advised him, in a hand-written note: ‘I suggest you now drop this subject.’

During the First World War, when reports of phantom Zeppelins flooded into the War Office, some officials were prepared to believe at least some of these UFOs really were airships, until it became obvious this was not possible. Likewise, in the 1990s their successors at the MoD suspected that advanced spy planes or even aliens might be responsible for some UFO flaps. For a time the UFO desk adopted the mantra of the popular TV series, The X-Files: ‘I want to believe.’

In the 1980s a detachment of SR-71 spy planes was based at RAF Mildenhall, Suffolk, headquarters of the US 3rd Air Force in the UK, until shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. During this period rumours spread that Mildenhall and other United States Air Force bases in England were being used by other black project aircraft, particularly during the period of NATO operations in the former Yugoslavia, where the F-117 fighter saw action. This coincided with a dramatic rise in the number of sightings of UFOs such as those reported in Belgium and Gloucestershire (see p. 140). They were often called ‘Silent Vulcans’ owing to their sleek delta-winged shape, huge size and apparently silent flight. But oddly, despite their unconventional shape, these UFOs often displayed the flashing white strobes and rotating red and green beacons that are the standard aircraft lighting systems used for night-flying.

Stealth technology has advanced in leaps and bounds since the F-117 and the B-2 bomber were removed from the secret list, and speculation has continued to grow about what might constitute the next generation of ‘black project’ aircraft. From the late 1980s, rumours spread that the United States Department of Defense was testing a highly advanced hypersonic aircraft as a replacement for the ageing SR-71. The mystery began in 1985 when a Pentagon budget report listed a project called ‘Aurora’ alongside the SR-71, apparently by mistake. The United States Air Force later explained the error by claiming the name was used in the document to conceal the existence of another then-secret project, the B-2 Stealth bomber. By then it was impossible to put the genie back inside the bottle.

Although Secretary of the Air Force, Donald Rice, went on record to flatly deny such a project existed, throughout the 1990s sightings of the Aurora frequently made headlines in UFO magazines and specialist aviation journals such as Jane’s Defence Weekly. The Aurora was said to be capable of incredible feats, such as high altitude flight at Mach 8 at a top speed of 5,300 mph (8,530 km/h). In 1992 The Scotsman published a story that claimed an anonymous air traffic controller had seen a fast-moving blip ‘emerge from the area of the joint NATO–RAF station at RAF Machrihanish at approximately three times the speed of sound’. Puzzled by the experience, he called up the remote airfield on the tip of the Kintyre peninsula but was told to forget what he had seen.17

This story prompted Scottish MPs to ask in Parliament if permission had been given to the Americans for secret flights through British airspace. Privately, the MoD advised Defence Secretary Tom King on 2 March 1992 that the last SR-71 left the UK from RAF Mildenhall in 1990 but the confidential briefing added cryptically: ‘There may or may not be an Aurora project. There is no knowledge in MoD of a “black” programme of this nature, although it would not surprise the relevant desk officers in the Air Staff and DIS if it did exist.’18

Despite denials, the Aurora story refused to die. When in December 1992 Jane’s Defence Weekly published a statement from an impressive eyewitness, relations between the US and UK were put under further strain. Chris Gibson’s account was the most credible to emerge from the welter of rumours that preceded it. He was a member of the Royal Observer Corps and an expert in aircraft identification, so his account of what he saw flying low over the North Sea one afternoon in August 1989 carries the weight of experience. Gibson was working on an oil rig at Galveston Key, about 100 miles northeast of Great Yarmouth, at the time. His attention was attracted by a colleague who returned from the deck calling out: ‘ “Have a look at this”: I looked up, saw a KC-135 tanker and two [USAF] F-111s, but was amazed to see the triangle. I am trained in instant recognition, but this triangle had me stopped dead. My first thought was that it was another F-111, but… it was too long and it didn’t look like one. My next thought was that it was an F-117, as the highly swept platform of the [Stealth fighter] had just been made public. Again the triangle was too long and had no gaps.’19

Gibson was left struggling for ideas and as the formation passed by he realised the two men had seen something that did not officially exist. On checking his aircraft recognition manual, he found nothing matched and immediately sat down to sketch what he had seen. Publication of his drawings prompted the British Air Attaché in Washington to write to the Air Staff in London for advice on what he should tell the Americans. His letter, dated 22 December 1992, read: ‘[The US] Secretary of the Air Force, the Honorable Donald B. Rice, was to say the least incensed by the renewed speculation, and the implied suggestion that he had lied to Congress by stating that Aurora did not exist… the whole affair is causing considerable irritation within HQ [US Air Force] and any helpful comments we can make to defuse the situation would be appreciated.’20

To date, no convincing explanation for the North Sea sighting has been provided by the MoD and the United States has never confirmed the existence of the mysterious Aurora. Writing in 1997 Gibson concluded: ‘Whether this aircraft was Aurora is debatable [and] my background precludes jumping to conclusions based on a single piece of evidence. I don’t know what it was, but it was the only aircraft I have ever seen that I could not identify.’21

UFO desk officer Nick Pope warns MoD branches to expect sightings of a bright cigar-shaped UFO over London in the spring of 1993. This flap was traced to an illuminated airship advertising the launch of the Ford Mondeo. DEFE 31/181/1 and DEFE 24/1954/1.

Public fascination with UFOs, alien abductions and crop circles peaked in the mid-1990s, partly as a result of the popularity of the hit US TV series The X-Files. The fictional plot embraced UFO conspiracy theories and series creator Chris Carter’s storyline appeared to reflect widespread suspicion that governments were hiding facts about UFOs and aliens from the public.

Shortly after the series aired on British TV, a serving MoD official went public with what the press began to call ‘Britain’s real X-files’. In 1996 Nick Pope published a personal account of his tour of duty on the UFO desk, which resulted in his conversion to a believer in UFOs. The cover blurb for his book Open Skies, Closed Minds proclaimed the three years he spent researching the subject at the MoD (1991–4) had changed his life: ‘from starting out as a sceptic, he became a firm believer in the reality of UFOs.’ Drawing upon cases that impressed him as evidential, such as the Rendlesham incident and the Cosford UFO flap, he concluded that ‘extraterrestrial spacecraft are visiting Earth and that something should be done about it urgently’.

This public declaration, from a former MoD official, went much further than any previous statement from more senior officials such as Ralph Noyes (see p. 49). In fact Pope’s statements in his book, as well as in a series of TV and radio programmes, directly contradicted his own department’s long-standing policy, repeated in all correspondence with the public. For if UFOs were of ‘no defence significance’, here was someone who was responsible for implementing this policy who clearly did not believe it. According to Pope’s own account, some former colleagues were unhappy with the content of his book and attempts were made to block its publication. Fortunately, the risks of censorship in a new era of open government overcame these objections but Pope’s employers pointed out that ‘clearance to publish does not imply MoD approval of, or agreement with, the contents.’ A press briefing drawn up by the MoD made it clear that Pope’s views were his own opinions and did not reflect official policy on UFOs.

Nevertheless, files released by the MoD in 2007 under the Freedom of Information Act have revealed that other defence officials privately shared Nick Pope’s belief that some UFOs could be spacecraft piloted by extraterrestrials. The evidence suggests this was not because, as some have claimed, they had privileged access to hard evidence that was being concealed from the public. Rather, they reached their conclusions by reading and watching the same books and TV programmes that were widely available to everyone else. From the 1950s onwards, some have been inclined to believe the ‘Extra Terrestrial Hypothesis’ (ETH), while others have dismissed the subject as being irrelevant.

Early in the 1990s it seems the faction who wanted to believe began to gain some small influence on the MoD’s UFO policy. During August 1993 a RAF Wing Commander working for the Defence Intelligence Staff lobbied MoD officials at a Whitehall briefing on the need for a properly funded study of UFOs. He opened his case by stating: ‘I am well aware that anyone who talks about UFOs is treated with a certain degree of suspicion. I am briefing on the topic because DI55 have a UFO responsibility, not because I talk to little green men every night!’22

This official, whose name has been blacked out along with all others in the most recent documents released by the MoD, continued: ‘the national security implications [of UFOs] are considerable. We have many reports of strange objects in the skies and we have never investigated them.’ He said if the sightings were caused by American stealth aircraft then these would not constitute a threat, ‘although it would be most alarming if the craft were using UK airspace without authority’. If on the other hand they were of Russian or even Chinese origin, there would be a clear threat and ‘[MoD would] urgently need to establish the nature of the craft and its capabilities.’ He then turned to extraterrestrials: ‘If the sightings are of devices not of the earth then their purpose needs to be established as a matter of priority. There has been no apparently hostile intent and other possibilities are: (1) military reconnaissance, (2) scientific, (3) tourism.’

The Wing Commander said the key priority for the MoD was ‘Technology Transfer’, which he explained in this way: ‘if the reports are taken at face value then devices exist that do not use conventional reaction propulsion systems, they have a very wide range of speeds and are stealthy. I suggest we could use this technology, if it exists.’23

Against this background, intelligence officers argued that the MoD could be placed in a vulnerable position if they were ever questioned in Parliament on the basis of their public stance that UFOs were ‘of no defence significance’. This internal debate came to a head in 1995 when a collection of files were opened at The National Archives, under the 30-year rule, that revealed UFO reports had been routinely copied to Defence Intelligence branches since the 1950s. When officials realised these documents were now in the public domain an exasperated intelligence officer wrote to the ‘UFO desk’: ‘I see no reason for continuing to deny that [Defence Intelligence] has an interest in UFOs. However, if the association is formally made public, then the MoD will no doubt be pressurised to state what the intelligence role/interest is. This could lead to disbelief and embarrassment since few people are likely to believe the truth that lack of funds and higher priorities have prevented any study of the thousands of reports received.’24

In the margin of this sentence a UFO desk official scribbled: ‘Ouch!’.

One snowy night, 27 January 2004, Alex Birch took a series of colour slides showing the town hall in Retford, Nottinghamshire, for submission to a photography competition. He saw nothing unusual at the time. But on examining the transparencies he was amazed to find an image showing what appears to be a classic ‘flying saucer’. Having ruled out lens flares and aircraft, he contacted the Ministry of Defence. They said ‘defence experts’ would like to take a closer look at the mysterious ‘elliptical object’ that was visible on the transparency. Alex delivered the slide to the MoD Main Building and it was sent to the Defence Geographic and Imagery Intelligence Agency for computer analysis. DGIA said they were unable to calculate the size of the ‘object’ because its distance from the camera was unknown. In their report, dated 2 August 2004, the agency told the MoD ‘no definitive conclusions’ could be reached but ‘it may be coincidental that the illuminated plane of the object passes through the centre of the frame, indicating a possible lens anomaly, [for example] a droplet of moisture’.1 The story took a strange twist because this was not the first time the Ministry had been left perplexed by a photo taken by Alex Birch. He first made headlines in 1962 when, as a 14-year-old schoolboy, he took a black and white photograph showing a fleet of ‘flying saucers’ over Sheffield [see p. 72]. This was the second occasion that Alex’s UFO images had been subjected to an inconclusive MoD investigation.2

An anomalous image captured by photographer Alex Birch at Retford Town Hall, Nottinghamshire, in January 2004. The image was subjected to computer analysis by MoD intelligence staff. They could not identify the ‘object’ shown. But they suspected it might be a droplet of moisture on the camera lens. DEFE 24/2060/1

It was also not the first time that the MoD had drawn upon the expertise of their image intelligence experts to help them evaluate photographs and film footage depicting aerial phenomena. In 1994 VHS footage of a strange object in the sky near Bonnybridge in Scotland was sent to experts at JARIC (RAF Brampton), the predecessor of DGIA. They concluded: ‘It cannot be determined whether this object is real or a hoax – it is possible it is a hoax using a kite or video studio effects.’3 Two years earlier, colour photographs showing a diamond-shaped UFO were taken by a man walking near the A9 at Calvine in Scotland. The photographs show the object appeared to be shadowed by a RAF Harrier jet. Desk officers from DI55 suspected the image could show a USAF black project aircraft and prints of the photographs were sent to JARIC for scrutiny. The prints subsequently disappeared and the MoD claim there is no surviving record of the conclusions reached by their covert investigation of the images.4

A photocopy of an original colour print showing a strange diamond-shaped UFO accompanied by a Harrier jet, seen over Calvine in Scotland in daylight one afternoon in August 1990. The MoD’s Defence Intelligence Staff were unable to explain the object depicted in the photograph or trace the RAF Harrier jet also visible below the ‘UFO’. DEFE 31/180/1.

This type of work triggered a sharp exchange of views within the Ministry. In public, MoD policy was they did not spend public money on UFO research. But in private, desk officers at the Defence Intelligence staff were keen to take a look at photos and films of UFOs obtained by the public. In order to do so, UFO desk officers would need authorisation to approach members of the public either by phone or by a personal visit. This was seen as a risky strategy as both the press and UFOlogists would interpret any visits from ‘the men from the Ministry’ as proof that a cover-up was underway.

The problem for the MoD was that if no official study had ever been carried out, how could they honestly claim that UFOs posed no threat to the defence of the realm? The existence of this Achilles heel troubled intelligence officers throughout the last two decades of the twentieth century. In 1988 DI55 became embroiled in a project to produce a computerised database of UFO reports, involving a student on a work experience placement with the RAF’s scientific staff. But even this ‘low priority’ task was halted when the news reached the head of the UFO desk. A DI55 desk officer briefed intelligence staff that: ‘when Sec(AS) 2 heard about the study, they decreed that all work should cease as it was in contravention of Ministerial statements that UFOs did not pose a threat to the UK, and that resources should not be diverted from more important work to investigate UFO incidents.’ He said it appeared ‘there was some concern about public reaction if knowledge of the work being undertaken emerged in the media.’25

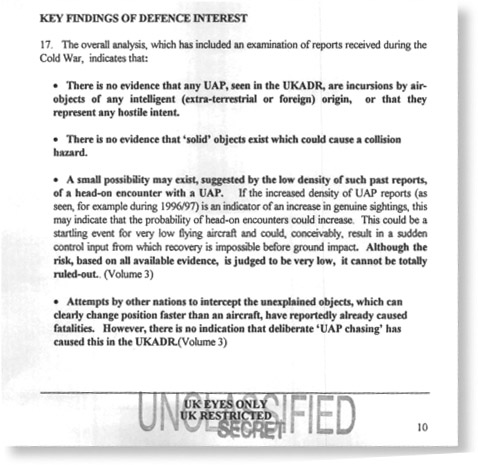

An extract from executive summary/final recommendations of DI55’s Condign report, ‘Unidentified Aerial Phenomena in the UK Air Defence Region’, completed in 2000.

In 1996, after years of internal wrangling, the MoD reluctantly agreed to earmark £50,000 of public money from an existing defence contract for a UFO study that was carried out under strict secrecy. This was a momentous moment. After 50 years and thousands of reports this was the first time that a detailed study had been commissioned by the MoD to investigate whether UFOs were a real phenomenon that might pose a threat to the defence of the UK.

The man selected to conduct the study was a contractor from the aerospace industry who had acted as a special adviser to the MoD on UFOs. His identity has been withheld due to the sensitive nature of his other work for the Defence Intelligence Staff. In 1996 he was asked to carry out a study that included, as part of its remit, an assessment of any possible flight safety risks posed by what intelligence officers now routinely referred to as ‘unidentified aerial phenomena’ (UAP). This acronym was chosen because it was seen as avoiding both the implication of an extraterrestrial origin and the presence of some form of piloted craft. It followed that those incidents that could not be explained by MoD remained ‘unidentified’ rather than ‘extraterrestrial’.

The UFO study was hidden by the codename ‘Project Condign’, a word the Oxford English Dictionary defines as ‘severe and well deserved (usually of punishment)’. Its terms of reference were ‘to determine the potential value, if any, of UAP sighting reports to Defence Intelligence’. In addition, ‘the available data [was to be] studied principally to ascertain whether there is any evidence of a threat to the UK and… to identify any potential military technologies of interest’.

Its foundation stone was a sample of UFO sightings taken from reports held in DI55 files. By the completion of the project in February 2000, details of more than 3,000 reports covering a 10-year period ending in 1997 had been manually entered into a computer database.

The retired intelligence officer who conducted the report was faced with a number of problems. Firstly, as the study was conducted in secret on a strict ‘need-to-know’ basis, he could not contact witnesses or consult independent experts. Secondly, the raw data upon which he relied for the study was of very poor quality. An earlier Air Ministry study in 1955 had found around 90 per cent of UFO reports could be explained if they were investigated thoroughly before the scent went cold (see p. 61). In contrast, most of the reports received by the MoD between 1987 and 1997 had simply been glanced at and then filed away.

Inevitably, the flawed methodology that underpinned Project Condign led to conclusions that were ultimately questionable. For example, the project’s author concluded that, despite hundreds of UFO reports made from the ground, ‘there is no firm evidence… that a RAF crew has ever encountered or evaded a low altitude UAP event’. This conclusion cannot be regarded as definitive, given the limited information available to the author; elsewhere he notes that he was unable to access the contents of intelligence files on UFOs before 1975 that would have contained detailed reports from RAF aircrew such as Michael Swiney (see p. 47). These had been destroyed years earlier when someone in the MoD decided they contained nothing of defence or historical interest.

Other sections of the study are based upon more reliable information including UFO reports made by civilian aircrew. In his discussion of this topic the author wrote: ‘It is clear that unexplained airmisses are discussed among crews… It is believed that many more civil events due to UAP remain unreported. This is because… the airline crews have most probably decided that the UAP are benign, secondly they are concerned about their individual reputations as professionals and finally the effect any publicity might have on airline business.’26

For this section of the study the author was forced to rely upon details of just seven ‘unexplained’ incidents reported to the airmiss working group between 1988 and 1996, including the Manchester Airport incident (see p. 137). Of these, all but one occurred below 20,000 ft in good visibility and all were witnessed by at least two members of the flight crew. Like David Hastings, the objects they reported were ‘always extremely close and closing fast’ when first sighted, but the experience was so fleeting that ‘no evasive action could be taken in the time available and no damage, other than a fright to the crew has occurred’. Some crews described close sightings of ‘black objects’ the size of small fighter aircraft. Three involved radar trackings, but just one of these was co-incident with the visual sighting.

Despite the restrictions he faced, the author of the Condign report boldly stated in his conclusions that ‘the possibility exists that a fatal accident might have occurred in the past’ as a result of aircrew taking sudden evasive action to avoid a UFO when flying fast and low. This statement was made after the author scrutinised more than one hundred unexplained fatal accident reports involving RAF aircraft during a period of 30 years. Whilst none of these contained any evidence linking them with UFOs, he did find anecdotal evidence that some aircrew had lost their lives as a result of close encounters in the former Soviet Union.

The study recommended that military aircrew should be advised that ‘no attempt should be made to out-manoeuvre a UAP during interception’. The author’s advice to civilian aircrews was: ‘although UAP appear to be benign to civil air-traffic, pilots should be advised not to manoeuvre, other than to place the object astern, if possible.’ Although the possibility of aircrew actually encountering a UFO remained very low and the level of risk from a collision was judged as being lower than a bird strike, the study decided this could not be ruled out.

An example of an ‘Identified Flying Object’, in this case caused by laser lights from a Tina Turner concert. DEFE 24/1939/1

Although classified secret at the time it was completed, I obtained a full copy of the Condign report using the Freedom of Information Act in 2006. The study revealed that work on the UFO database began in 1997 as Tony Blair’s government swept to power, ushering in an era of ‘open government’. Although the MoD did not anticipate it then, the clock was ticking towards a point when they would have to find a way of making their entire back catalogue of UFO reports available to the public.

In the meantime a restricted group of senior officials received the conclusions of what was described as ‘the first UK detailed and authoritative [UFO] report which has been produced since the 1950s’. The executive summary contained the following stunning admission: ‘That [UFOs] exist is indisputable. Credited with the ability to hover, land, take off, accelerate to exceptional velocities and vanish, they can reportedly alter their direction of flight suddenly and clearly can exhibit aerodynamic characteristics well beyond those of any known aircraft or missile – either manned or unmanned.’27

This summary covered a hefty four-volume report, 465-pages in length. The ‘summary of findings’ led the author to conclude that although UFOs, or ‘UAPs’ certainly existed, they posed no threat to defence. He found no evidence among the 30 years of reports on file that UFOs ‘are incursions by air objects of any intelligent (extra-terrestrial or foreign) origin’. Furthermore, ‘no artefacts of unknown or unexplained origin have been reported or handed to the UK authorities, despite thousands of UAP reports.’

In addition, the report’s author had found nothing about UFOs in classified signals intelligence or from information gathered by electronic eavesdropping. Apart from a few ambiguous, blurred photographs and videos there was little useful imagery showing UFOs and no reliable radiation measurements, even from supposedly evidential cases such as Rendlesham.

The Condign study did not attempt to investigate any specific sightings in depth and confined its scrutiny to individual UFO flaps that were subjected to statistical analysis using its computer database. Although flawed in its methodology, the study found many could be explained as the misidentifications of man-made aircraft, natural phenomena and ‘relatively rare and not completely understood phenomena’.

It was this final category that generated the most controversial claim made by the Condign report. In the second volume of the report, the author listed more than 20 natural phenomena that have undoubtedly given rise to UFO sightings in the past. Some less familiar phenomena included new types of lightning called red sprites and blue jets that appear high above thunderclouds. These were identified and photographed only in recent years and may explain some of the UFO sightings made by aircrew. Alongside these are noctilucent clouds, auroral displays, mirages, sun dogs and other poorly understood phenomena such as ‘earthquake lights’, ball lightning (see p. 13) and atmospheric plasmas.

Plasma is the most common form taken by matter. Atmospheric plasmas are clusters of electrically charged particles that can take the form of gaseous clouds and beams that respond to electromagnetic fields. It follows that many unexplained atmospheric phenomena such as ball lightning and the Will-o’-the-Wisp described in Chapter 1, along with ‘earthquake lights’ produced by movements in the Earth’s crust, are also types of plasma observed in the lower atmosphere.

The study concluded there was ‘strong evidence’ that a residue of unidentified sightings, particularly those reported by aircrew, were caused by these atmospheric plasmas. The report lists examples of ball lightning flying ahead or behind aircraft that resemble the ‘foo-fighters’ reported by aircrew during the Second World War (see pp. 16–20). On other occasions aircrew have reported lightning balls entering the fuselage of aircraft during thunderstorms.

Although witnesses often perceive UFOs as solid objects, the report’s author concluded the plasma explanation was likely. But he had to admit that: ‘the conditions and method of formation of the electrically-charged plasmas and the scientific rationale for sustaining them for significant periods is incomplete and not fully understood.’

Despite the lack of scientific evidence for these mysterious plasmas occurring naturally in the lower atmosphere, the author took a step further into speculative territory by applying his theory to explain ‘close encounter’ stories such as those described in Chapter 5. Drawing upon the UFO literature and experimental research carried out by a Canadian neuro-scientist, Dr Michael Persinger, he pondered the idea that plasmas and ‘earthquake lights’ might explain a range of alien abduction experiences. His report toyed with the improbable-seeming idea that on rare occasions exposure to atmospheric plasmas may cause responses in the temporal-lobe area of the human brain, leading those affected to experience periods of ‘missing time’ and elaborate hallucinations that might be interpreted as supernatural experiences or contact with alien beings. This, the report’s author suggested, may be ‘a key factor in influencing the more extreme reports [that] are clearly believed by the victims’.

Leaving aside such far-out speculation, the Condign report’s key recommendation was that UFOs had no intelligence value and that the Defence Intelligence Staff should cease to receive the reports that had, for many decades, been routinely copied to them by the MoD’s UFO desk.

The report’s conclusions and recommendations were circulated within the MoD during December 2000, classified as ‘Secret: UK Eyes Only’. The covering letter made it clear that officials believed it was too early, at this stage, to release the results of the study to the public: ‘Although we intend to carry out no further work on the subject… we hardly need remind addressees of the media interest in this subject and consequently the sensitivity of the report. Please protect this subject accordingly, and discuss the report only with those who have a need to know.’28

This memo and the report it covered remained secret for just over five years before it was released under the Freedom of Information Act. In 2000, when the report was completed, government files on UFOs were still being routinely withheld for up to half a century, and in other cases had been destroyed long before the arrival of open government. Today, however, Freedom of Information has opened this secret world to unprecedented scrutiny and allowed everyone access to thousands of pages of official documentation on the UFO mystery.