3

Muscles of the Face, Head, and Neck

Although in today’s society yoga is sometimes portrayed as a marketable exercise program, or even as a cult in some circles, the ancient and true goal of yoga is meditation, leading to awareness of the true self, our deepest nature of oneness and infinity. Asanas and pranayamas are practiced to attain this state of unity.

The neck muscles are obviously important for movement of the head, but the muscles of the face and skull must also be included; otherwise, how can one achieve inner peace unless attention is focused on the muscles of concentration, emotion, and tension found in this area? A few of these will be presented here to help the practitioner understand that, as muscles and mechanisms are understood in yoga, a profound knowledge can be gained.

Muscle Relaxation and Contraction: The Motor Unit

The relaxation of certain muscles is paramount if one wishes to achieve correct posturing and release in yoga. Skeletal muscles can be brought under conscious control, as they are linked directly to the somatic nervous system (SNS), which is part of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The SNS carries information from the nerves to the central nervous system (CNS) and from the CNS to the muscles and sensory fibers; it is associated with voluntary muscle control.

A “motor unit” is defined as the motor neuron (there can be many in a single muscle) and all the muscle fibers it innervates; it is the single connection between the CNS and muscular activity. When the neuron transmits a nerve impulse, the muscle contracts: when the neuron does not transmit an impulse, the muscle relaxes. It has been proven that one has the ability to “train” the motor units to become quiet, allowing relaxation.

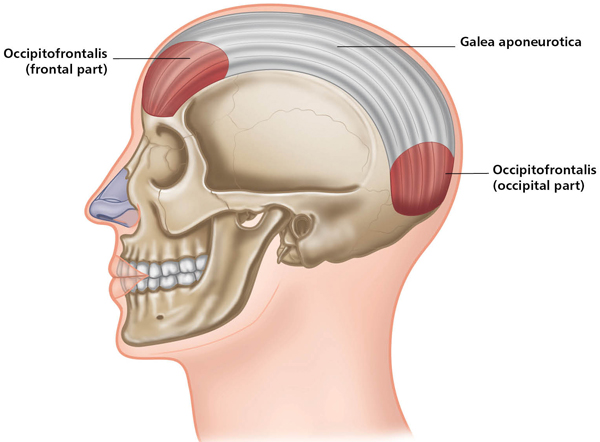

In simple terms, a willful decision of the mind can release internal signals to help silence the nerve impulses, resulting in relaxation. Imagine the following face and head muscles at rest, allowing for deeper release of tension. This leads to clarity.

A Note About the Hyoid Bone

The hyoid bone is found in the neck area, below the chin and above the larynx. In relation to joints, it is just beneath the jaw. Small and similar to a “wishbone,” it surrounds the esophagus. It is an anchoring structure for the tongue and other tissue, but does not articulate with other bones to form a joint. It moves up and down as one swallows and speaks.

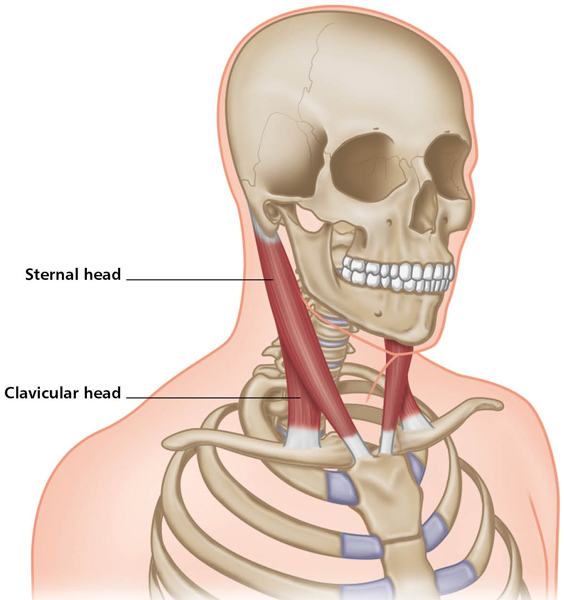

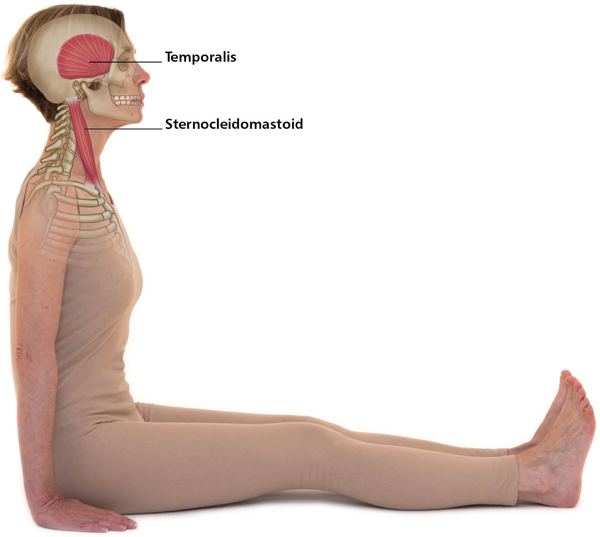

The hyoid is mentioned in this text because of placement and the tone of the muscles surrounding that can influence tension and digestion. The tongue is also important in this regard, as it is anchored to the hyoid. It is a connector between muscles in the front and back of the neck. As mentioned in the next section, the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and spleni muscles (splenius capitis/cervicis) can work in harmony if the hyoid bone is in the right alignment. Think of drawing the top of the throat back and up gently; the back of the neck will extend yet relax along with the front neck muscles, such as the SCM. Smaller, deeper muscles called the “longus capitis/colli” at the front of the cervical spine can then complete their mission: allowing the neck to lengthen even more. Sound like magic? Cueing the suspension of the head in any yoga posture can aid this alignment, releasing tension in connected areas, such as the shoulder girdle and shoulder joints. Reminding the practitioner to extend (but not hyperextend) the neck in backbends might also help in the positioning and conditioning of this entire area.

Agonist Versus Antagonist Muscles

Definitions of these muscle functions are given in Chapter 1. Here we will use the following neck muscles to illustrate agonists and antagonists. Opposite in location, as well as in flexion and extension, the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and spleni muscles, depending on the movement, are each other’s agonist and antagonist. For example, in a sit-up or in yoga Apanasana, the sternocleidomastoid flexes the neck against gravity (concentric contraction) while the spleni act antagonistically and lengthen. The SCM then contracts eccentrically on the way down, to keep the head from striking the ground.

Usually when the extensors contract concentrically to lift the head (body in a vertical position), the flexors relax. Similarly, when a flexor contracts concentrically, or shortens, the opposing extensor relaxes, even stretching or lengthening, depending on the forces. Remember that agonists are referred to as “the prime movers that contract to perform a specific movement,” so their opposite muscles must release to allow this to happen.

Dandasana (Staff Pose) Level I

Tadasana (Mountain Pose) Level I