Belváros, from Vörösmarty Tér to the Great Market Hall

March 15 Square (Március 15. Tér)

University Square (Egyetem Tér)

Great Market Hall (Nagyvásárcsarnok)

Pest’s Belváros (“Inner Town”) is its gritty urban heart—simultaneously its most beautiful and ugliest district. You’ll see fancy facades, some of Pest’s best views from the Danube embankment, richly decorated old coffee houses that offer a whiff of the city’s Golden Age, parks tucked like inviting oases between densely populated streets, recently pedestrianized streets that ooze urbane sophistication, and a cavernous, colorful market hall filled with Hungarian goodies. But you’ll also experience crowds, grime, and pungent smells like nowhere else in Budapest. Remember: This is a city in transition. Local authorities plan to ban traffic from more and more Town Center streets in the coming years. If construction and torn-up pavement (common around here) impede your progress, be thankful that things will be nicer for your next visit. Within a decade, all of those rough edges will be sanded off...and tourists like you will be nostalgic for the “authentic” old days. (If you want the sanitized version today, stick with the other tourists on Váci utca.)

Even if this whole walk doesn’t appeal to you, don’t miss the spectacular Great Market Hall, described on here.

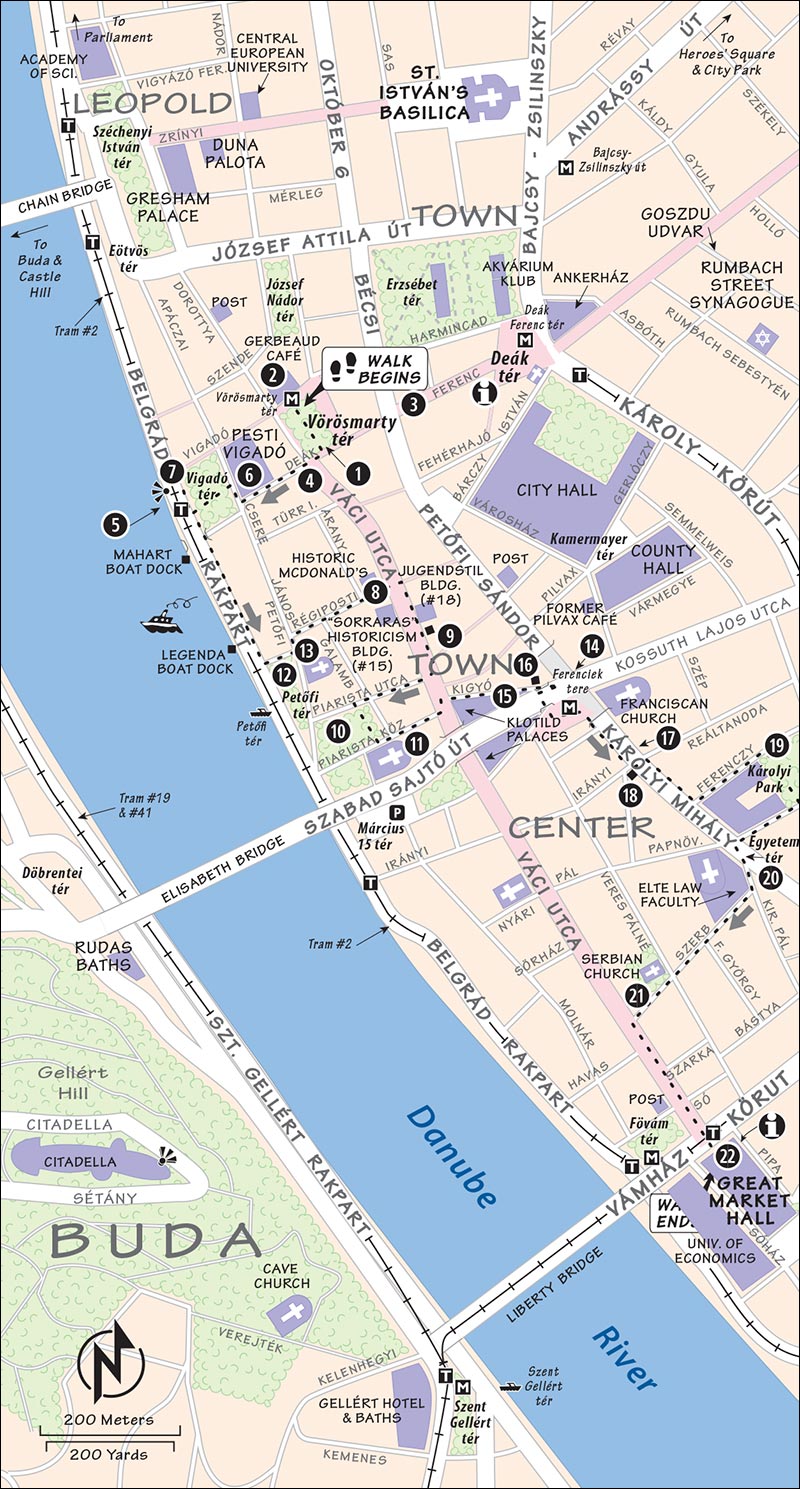

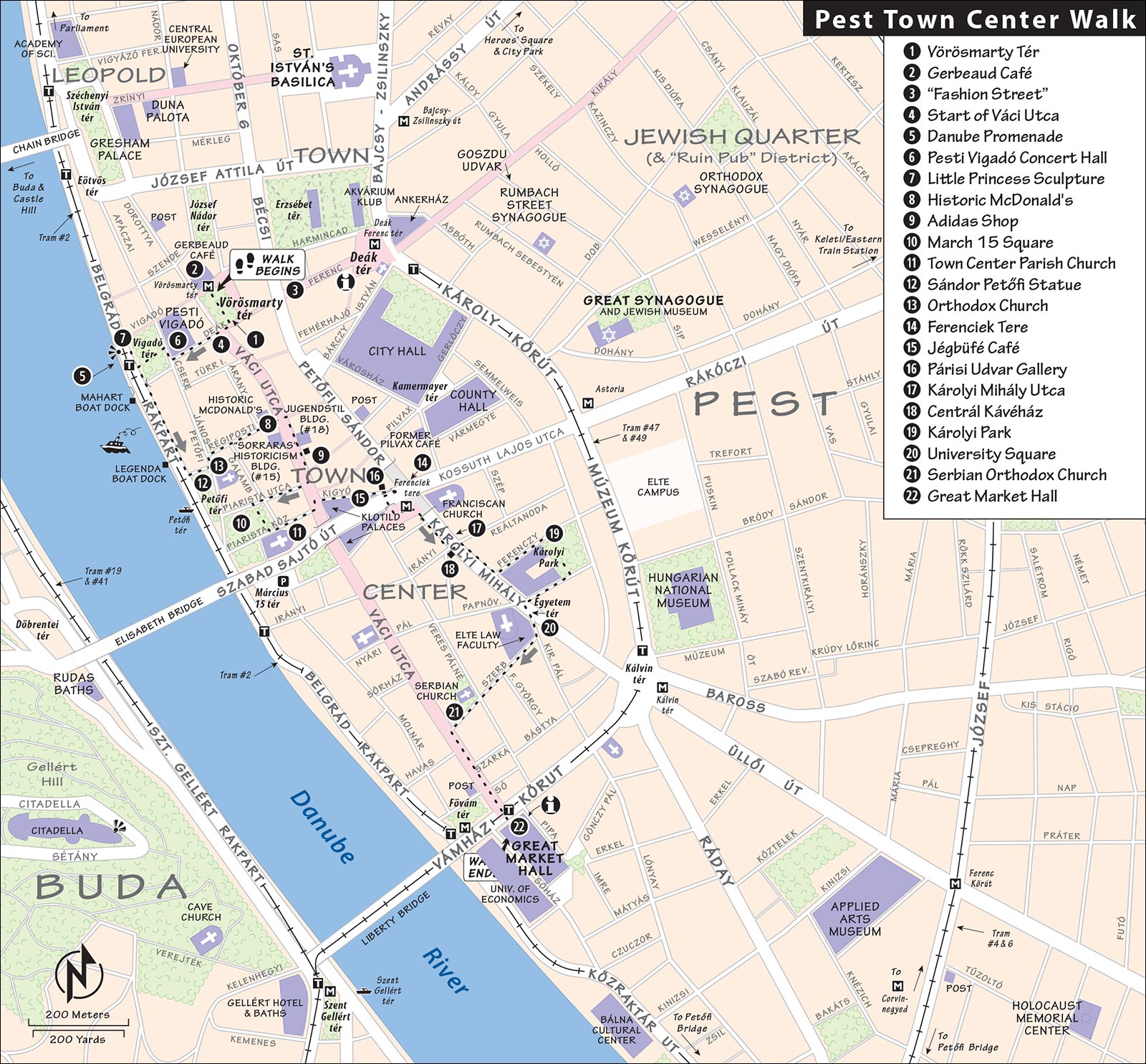

(See "Pest Town Center Walk" map, here.)

Length of This Walk: Allow 1.5 hours.

Getting There: Take the M1/yellow Metró line to the Vörösmarty tér stop.

Károlyi Park: Free, open daily 8:00-dusk.

Great Market Hall: Free, Mon 6:00-17:00, Tue-Fri 6:00-18:00, Sat 6:00-15:00, closed Sun, Fővám körút 1.

Starring: The urban core of Budapest, a gorgeous riverfront promenade, several of the city’s top cafés, and a grand finale at the Great Market Hall.

Nearby Eateries: For restaurants in Pest's Town Center, see here.

(See "Pest Town Center Walk" map, here.)

• Start on the central square of the Town Center, Vörösmarty tér (at the M1 Metró stop of the same name). Face the giant, seated statue in the middle of the square.

As we begin exploring the central part of Pest, consider its humble history. In the mid-1600s, Pest was under Ottoman occupation and nearly deserted. By the 1710s, the Habsburgs had forced out the Ottomans, but this area remained a rough-and-tumble, often-flooded quarter just outside the Pest city walls. Peasants came here to enjoy bearbaiting (watching brutal, staged fights between bloodhounds and bears—like cockfights, only bigger and angrier, with more fur and teeth). The rebuilding of Pest was gradual; most of the buildings you’ll see on this walk are no older than 200 years.

Today this square—a hub of activity in the Town Center—is named for the 19th-century Romantic poet Mihály Vörösmarty (1800-1855), whose statue dominates the little park in the square’s center. Writing during the time of reforms in the early 19th century, Vörösmarty was a Romantic whose poetry still stirs the souls of patriotic Hungarians—he’s like Byron, Shelley, and Keats rolled into one. One of his most famous works is a patriotic song whose popularity rivals the national anthem’s: “Be faithful to your country, all Hungarians.” At Vörösmarty’s feet, as if hearing those inspiring words chiseled into the stone, figures representing the Hungarian people rise up together. During Vörösmarty’s age, the peasant Magyar tongue was, for the very first time, considered worthy of literature. The people began to think of themselves not merely as “subjects of the Habsburg Empire”...but as Hungarians.

• Survey the square with a spin tour. First, facing the statue of Vörösmarty, turn 90 degrees to the left.

At the north end of the square is the landmark Gerbeaud café and pastry shop. Between the World Wars, the well-to-do ladies of Budapest would meet here after shopping their way up Váci utca. Today it’s still the meeting point in Budapest...for tourists, at least. Consider stepping inside to appreciate the elegant old decor, or for a cup of coffee and a slice of cake (but meals here are overpriced). Better yet, hold off for now—even more appealing cafés await later on in this walk.

The yellow M1 Metró stop between Vörösmarty and Gerbeaud is the entrance to the shallow Földalatti, or “underground”—the first subway on the Continent (built for the Hungarian millennial celebration in 1896). Today, it still carries passengers to Andrássy út sights, running under that boulevard all the way to City Park (it basically runs beneath the feet of people following my Andrássy Út Walk).

• Turn another 90 degrees to the left.

This super-modern glass building is the newest addition to Vörösmarty tér. If you think its appearance is jarring, then you should have seen the communist-style eyesore it replaced. Downstairs is upscale shopping; higher up are offices; and at the top are luxury apartments. Early plans called for a Mediterranean garden spiraling up inside this building, but it never materialized—so now it’s just a beautiful waste of space.

• Turn another 90 degrees to the left, and walk to the beginning of the Váci utca pedestrian street. Look up the street that’s to your left (with the yellow, pointy-topped building at the end).

This traffic-free street (Deák utca)—also known as “Fashion Street,” with top-end shops—is the easiest and most pleasant way to walk to Deák tér and, beyond it, through Erzsébet tér to Andrássy út ( see the Andrássy Út Walk chapter).

see the Andrássy Út Walk chapter).

• Extending straight ahead from Vörösmarty tér is a broad, bustling, pedestrianized shopping street. For now, look—but do not walk—down this street; we’ll stroll a different stretch of it later on this walk.

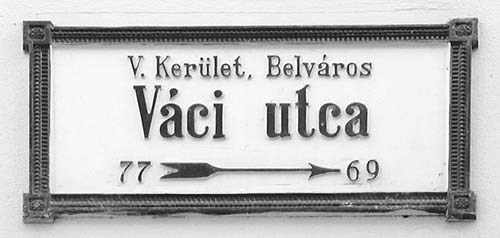

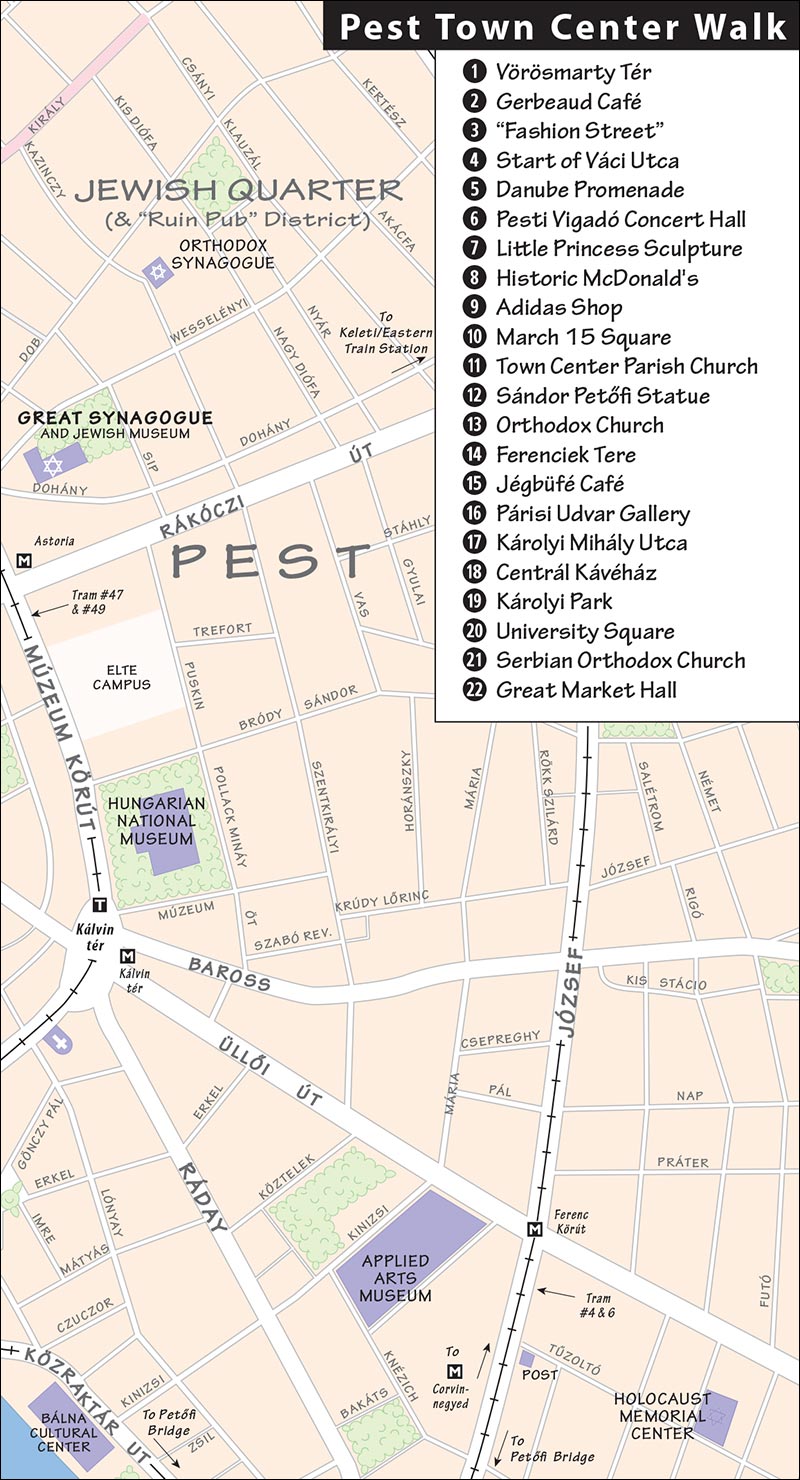

Dating from 1810-1850, Váci utca (VAHT-see OOT-zah) is one of the oldest streets of Pest. Váci utca means “street to Vác”—a town 25 miles to the north. This has long been the street where the elite of Pest would go shopping, then strut their stuff for their neighbors on an evening promenade. Today, the tourists do the strutting here—and the Hungarians go to American-style shopping malls.

This boulevard—Budapest’s tourism artery—was a dreamland for Eastern Bloc residents back in the 1980s. It was here that they fantasized about what it might be like to be free, while drooling over Nikes, Adidas, and Big Macs before any of these “Western evils” were introduced elsewhere in the Warsaw Pact region.

Ironically, this street—once prized by Hungarians and other Eastern Europeans because it felt so Western—is what many Western tourists today mistakenly think is the “real Budapest.” Visitors mesmerized by this people-friendly stretch of souvenir stands, tourist-gouging eateries, and upscale boutiques are likely to miss some more interesting and authentic areas just a block or two away.

Don’t fall for this trap. You can have a fun and fulfilling trip to this city without ever setting foot on Váci utca. In fact, this walk is designed to give you only the briefest taste of this famous street’s tackiness. (If you’re dying to saunter down Váci utca, this walk concludes at its far end—it takes about 20 minutes to walk back to its start.) Instead, we’ll zigzag through the heart of Pest’s Town Center for a look at the real “real Budapest.”

• Head for the river: Take the street that runs along the left side of the big glass building at the bottom of Vörösmarty tér. Cross the street and continue all the way to the railing and tram tracks. Swing about 30 yards to the right along the tracks, pausing by the statue of the girl with the dog. You’re on the most colorful stretch of the...

Some of the best views in Budapest are from this walkway facing Castle Hill—especially this stretch, between the white Elisabeth Bridge (left) and the iconic Chain Bridge (right). This is a favorite place to promenade (korzó), strolling aimlessly and greeting friends. Imagine the days before World War II, when—instead of mid-century monstrosities Marriott and InterContinental—this strip was lined with elegant grand hotels: Hungaria, Bristol, Carlton.

Take in the views of Buda, across the river (left to right): Gellért Hill, topped with its distinctive Liberation Monument; the green-domed Royal Palace, capping Castle Hill; and, farther along the hilltop, the colorful tile roof and spiny spire of the Matthias Church, surrounded by the cone-shaped decorations of the Fishermen’s Bastion.

Behind you (fronting the little park) is a big concert hall, which dominates this part of the promenade. This is the Neo-Romantic-style Pesti Vigadó—built in the 1880s, and recently restored. Charmingly, the word vigadó—used to describe a concert hall—literally means “joyous place.” In front, the playful statue of the girl with her dog captures the fun-loving spirit along this drag. At the gap in the railing, notice the platform to catch tram #2, which goes frequently in each direction along the promenade—a handy and scenic way to connect riverside sights in Pest. (You can ride it to the right, to the Parliament and the start of my Leopold Town Walk; or to the left, to the Great Market Hall—where this walk ends.)

• About 30 more yards toward the Chain Bridge, find the little statue wearing a jester’s hat. She’s playing on the railing, with the castle behind her.

The Little Princess is one of Budapest’s symbols and a favorite photo-op for tourists. While many of the city’s monuments have interesting back-stories, more recent statues (like this one) are simply whimsical and fun.

• Now walk down the promenade to the left (toward the white bridge). Directly in front of the corner of the Marriott Hotel, watch for the easy-to-miss stairs leading down under the tram tracks, to a crosswalk that leads safely across the busy road to the riverbank. From the top of these stairs, look along the river.

Lining the embankment are several long boats: Some are excursion boats for sightseeing trips up and down the Danube (especially pleasant at night), while others are overpriced (but scenic) restaurants. Kiosks along here dispense info and sell tickets for the various boat companies—look for Danube Legenda (their dock is just downstream from here—go down the stairs, cross the road, then walk 100 yards left; for details, see here).

• For now, continue walking downstream (left) along the promenade, passing in front of the blocky, dirty-white Marriott. When you reach the end of the Marriott complex, at the little parking lot, turn inland (left), cross the street, and walk up the street called Régi Posta utca. Head for the Golden Arches. You deserve a break today.

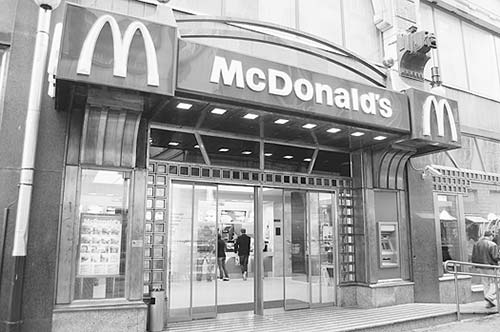

The fancy McDonald’s (on the left) was a landmark in Eastern Europe—the first McDonald’s behind the Iron Curtain. Budapest has always been a little more rebellious, independent, and cosmopolitan than other Eastern European cities, whose citizens flocked here during the communist era. Váci utca (which we’ll see next) was a showcase street during those grim times, making this a strategic location for Ronald McDonald and Co. Since you had to wait in a long line—stretching around the block—to get a burger, it wasn’t “fast food”...but at least it was “West food.” Váci utca also had a “dollar store,” where you could buy hard-to-find imported and luxury items as long as you had Western currency. During the Cold War, Budapest was sort of the “Sin City” of the Eastern Bloc. (What happened in Budapest, stayed in Budapest. Unless the secret police were watching...which they always were...uh-oh.)

• After the McDonald’s, Régi Posta utca crosses...

We’ll follow this crowded drag for two blocks to the right. As we stroll, be sure to look up. Along this street and throughout Pest, spectacular facades begin on the second floor, above a plain entryway (in the 1970s, the communist government made ground-floor shop windows uniformly dull). Locals like to say these buildings are “wearing socks.” Pan up above the knees to see some of Pest’s best architecture. These were the townhouses of the aristocracy, whose mansions dotted the countryside. You might notice that some of the facades are plain. Many of these used to be more ornate, like their neighbors, but were destroyed by WWII bombs and rebuilt in the stripped-down style of the austere years that followed.

As you head to the right down Váci utca, notice two buildings in particular. The second building on the right, at #15 (marked Sörorrás), features beautiful carved wood on the bottom and tile-and-stone decorations on the top. Combining everything that was typically thought of as “beautiful” in the late 19th century, this building exemplifies Historicism. Across the street and down one door (at #18), we see another architect’s response to that facade: stern Jugendstil (Vienna’s answer to Art Nouveau). Based in a movement called “The Secession” for the way it broke away from past conventions, this building almost seems to be having a conversation with the one across the street: “Dude, tone it down. Be cool.”

A few doors down (past the modern Mercure Hotel), on the left at #24, is any old Adidas shop...except, like the “any old McDonalds” we just saw, this was the first Adidas shop behind the Iron Curtain. And, like the McDonald’s, 30 years ago you’d have to stand in an hours-long line just to get in the door.

Continue strolling down the street. Here and elsewhere along Váci utca, you’ll see restaurants touting Hungarian fare. Avoid these places. Any restaurant along this street is guaranteed to be at least half as good and twice as expensive as other eateries nearby. (For better options—some just a few steps from Váci utca—see the Eating in Budapest chapter.)

• After about two blocks, turn right down the little lane called Piarista utca. You’ll emerge into a charming square called...

This fine riverfront square—facing the graceful modern lines of the Elisabeth Bridge and Gellért Hill—sits upon some serious history. This was the site of Contra-Aquincum, a third-century fortress built across (contra) the Danube from Aquincum, the main Roman settlement just a few miles up the river, in today’s Óbuda (see here). Contra-Aquincum fortified the narrowest Danube crossing, where the river is constricted at the base of Gellért Hill. Like so many others who have viewed Budapest as a boundary between West and East, the Romans considered the Danube the natural border of their empire—and fortresses like Contra-Aquincum helped keep the barbarian hordes at bay. For decades, the partially excavated ruins of Contra-Aquincum made this square an ugly jumble of fences and scaffolding, and it gained a reputation as one of downtown Budapest’s most dangerous corners. But now it has been gorgeously restored as a fine park, and those ancient ruins are neatly displayed under glass in the middle of the square.

The inland part of the square is enlivened by entertaining, kid-friendly fountains and a sprawling outdoor café, called simply Kiosk. While this walk passes a few genteel, old-fashioned coffee houses, these days young urbanites flock to places like this instead. Just order at the bar, then take the scenic seat of your choice.

The twin spires belong to the Town Center Parish Church (Belvárosi Plébániatemplom). The oldest building in Pest, this church was founded in 1046, and has lived through many iterations: Romanesque basilica, Gothic hall church, Ottoman mosque. Today, the Gothic foundations are topped with frilly, Baroque, onion-domed steeples. When Franz Josef and Sisi, the Habsburg monarchs, were crowned as the Hungarian king and queen in 1867, they did it right here on this square (for more on the couple and their coronation, see here).

Closer to the river (to the right as you face it), you can see a stirring statue of Hungary’s national poet, Sándor Petőfi—sort of the Hungarian Lord Byron. On the morning of March 15, 1848, a collection of local intellectuals and artists—who came to be known as the “Pest Youth”—gathered at the Pilvax Café (just three blocks up from here, at the corner of Pilvax köz and Városház utca; it’s now an Irish pub) to listen to their friend Sándor Petőfi read a new poem. Petőfi’s call to arms so inspired the group that they decided to revolt against their Habsburg oppressors...right away. Later that day, Petőfi read his poem again on the steps of the National Museum, rebels broke a beloved patriot out of jail at the castle, the group printed up their list of 12 demands...and the 1848 Revolution had begun. The revolution was ultimately crushed—and Petőfi was killed fighting at the front line—but Hungarians still feel pride about their valiant defeat. (While powerful nations have the luxury of celebrating great military victories, underdogs like the Hungarians cherish their Alamos.) March 15—the namesake of this square—remains one of Hungary’s national holidays. (For more on 1848, see here.)

The Orthodox Church facing Petőfi has noticeably mismatched steeples. The right one was blown off during World War II and never replaced.

• At the top of March 15 Square, find the grandly arcaded passage called Piarista köz, between the café and the church. Take this one block up to Váci utca, then proceed straight ahead one more block up Kígyó utca. Emerging into a busy urban zone, walk up to the Jégbüfé café near the corner, and survey...

“Franciscan Square”—so named for the church across the highway—is the perfect place to take in some of Pest’s best “diamond in the rough” architecture...fantastic facades that stand grim and caked with soot. The boulevard was developed (like so much of Budapest) in the late 19th century, to connect the Keleti/Eastern train station (to the left, not visible from here) with the Elisabeth Bridge (to the right). Looking toward the Elisabeth Bridge, you’ll see that the busy highway is flanked by twin apartment blocks called the Klotild Palaces. Recently both of these have been purchased by investors and turned into new hotels (you may see them working on the one on the left)—but other nearby buildings remain soot-caked. Imagine this area before 20th-century construction routed a major thoroughfare through it, when people could stroll freely amidst these elaborate facades. Someday, you might not have to imagine. But for now, breathe in the real Budapest.

The Jégbüfé, which you’re standing in front of, is an increasingly rare artifact of communist times. This bisztró serves stand-up coffee and cakes to urbanites on the go. For more details on this place, including how and what to order, see here.

Continue about 30 yards back the way you came, toward the right-hand Klotild Palace. On the right (at Kossuth Lajos út 11) is the low-profile entrance to the Párisi Udvar (“Parisian Courtyard”)—a grand, hidden gallery with delicate woodwork, fine mosaics that glitter evocatively in the low light, and a breathtaking stained-glass dome. Like the streets around it, this fine space sat neglected for decades, rotting all around its tenants. Now everybody has moved out, it has been purchased, and it’s slated to become yet another fancy hotel. While it’s likely closed for your visit, peek (or, if possible, walk) through the gate to appreciate the grand space...and daydream about the day when it’s returned to its former glory.

This gallery is a reminder that if you only experience what’s on the main streets in Budapest, you’ll miss a big part of the story. Behind most of Pest’s once-grand, now-crumbling facades, you’ll find cozy courtyards where residents carry out much of their lives. These courtyards, shared among neighbors and ringed by a common balcony, stay cool through the summer. Poking into some of these courtyards (which are generally open to the public, offering a handy shortcut through city blocks) is an essential Back Door experience for understanding the inner life of Budapest.

• Facing the gallery door, turn 180 degrees and head straight down the stairs into the pedestrian underpass. Surfacing on the other side, turn left, walk to the end of the block, then (at the church) turn right and walk along...

As you walk up the street, appreciate the pretty corner spires on the buildings. The yellow one marks the university library.

At the end of the block, cross Irányi utca, and you’ll be face-to-face with the entrance to the recommended Centrál Kávéház (on the right-hand corner)—another of Budapest’s newly rejuvenated, old-style café/restaurants (see here). Step inside to be transported to another time. If you haven’t taken a coffee break yet, now’s a good time.

Continue along Károlyi Mihály utca. Just past Centrál Kávéház, on the left (at #12), is the recently restored Ybl Palace, designed by and named for the prominent architect Miklós Ybl (who also did the Opera House). You can usually pop inside the palace and step into its fine inner courtyard to see the impressive remodel job.

• Continue along Károlyi Mihály utca to the end of the block, then take the first left up Ferenczy István utca. After the long building, dip through the green fence on the right, into...

This delightful, flower-filled oasis offers the perfect break from loud and gritty urban Pest. Once the private garden of the aristocratic Károlyi family from eastern Hungary (whose mansion it’s behind), it’s now a public park beloved by people who live, work, and go to school in this neighborhood. The park is filled with tulips in the spring, potted palm trees in the summer, and rich colors in the fall. On a sunny summer day, locals escape here to read books, gossip with neighbors, or simply lie in the sun. Many schools are nearby. Teenagers hang out here after school, while younger kids enjoy the playground. (If you need a potty break after all that coffee, a pay WC is in the green pavilion in the far-right corner.)

• Exit the park straight ahead from where you entered, and turn right down Henszimann utca. At the end of the street, you’ll come to a church with onion-dome steeples. The big plaza in front of it is...

This square is one of Budapest’s most recent to enjoy a makeover. An initiative called the “Heart of the City” is directing EU and Hungarian funds at renovating city-center streets and squares like this one (as well as Károlyi Mihály utca, which we were walking down earlier). Traffic is carefully regulated. Notice the automatic bollard that goes up and down to let in approved vehicles: buses, taxis, and local residents only. The modern lampposts and barriers are an interesting (and controversial) choice in this nostalgic city, where the priority is usually on re-creating the city exactly as it was a century ago. The idea in this case is to keep the original buildings, but surround them with a modern streetscape.

The colonnaded building on the left is the law school for ELTE University (Hungary’s biggest, with 30,000 students and colleges all over the city). The letters stand for “Eotvös Lorand Technical University,” named for an influential physicist. As in much of the former Soviet Bloc, the university system in Hungary is still heavily subsidized by the government. It’s affordable to study here...if you can get in (competition is fierce).

• Facing the university building, turn left, then take the first right down Szerb utca. After one long block, on the right, in the park behind the yellow fence, is a...

This used to be a strongly Serbian neighborhood—there’s still some Cyrillic writing on some of the buildings nearby. The church is rarely open, but if it is, step inside to be transported to the far-eastern reaches of Europe...heavy with incense and packed with icons.

The Serbs are just one of many foreign groups that have coexisted here. Traditionally, Hungary’s territory included most of Slovakia and large parts of Romania, Croatia, and Serbia—and people from all of those places (along with Austrians, Jews, and Roma/Gypsies) flocked to Buda and Pest. And yet, most of the residents of this cosmopolitan city still speak Hungarian. Throughout centuries of foreign invasions and visitors, new arrivals have undergone a slow-but-sure process of “Magyarization”—“becoming” Hungarian (often against their will). This has made Budapest one of the greatest “melting pot” cities in Europe, if not the world.

• Continue down Szerb utca, until it runs into Váci utca. Turn left, and set your sights on the colorful tiled roofs two blocks directly ahead. Across the street is the...

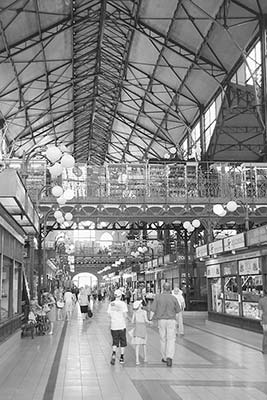

This market hall (along with four others) was built—like so much of Budapest—around the millennial celebration year of 1896 (see here). Appreciate the colorful Zsolnay tiles lining the roof—frostproof and harder than stone, these were an integral part of the Hungarian national style that emerged in the late 19th century.

Tunnels connect this hall to the Danube, where goods could be unloaded at the customs house (now Budapest Corvinus University of Economics, formerly Karl Marx University, next door) and easily transported into the market hall. Along the river behind the market hall and university—not quite visible from here—is the sleek, glass-roofed Bálna (“Whale”), a super-modern cultural center (with an extension of the Great Market Hall’s vendors, and art gallery, and inviting public spaces) that opened in late 2013 (for details, see here).

To the right, the green Liberty Bridge—formerly named for Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef—spans the Danube to the Gellért Baths, in the shadow of Gellért Hill. And to the left, the Small Boulevard (here named Vámház körút) curls around toward Deák tér, passing Kálvin tér, the National Museum, and the Great Synagogue along the way.

Step inside the market and get your bearings: The cavernous interior features three levels. The ground floor has produce stands, bakeries, butcher stalls, heaps of paprika, goose liver, and salamis. Upstairs are stand-up eateries and souvenirs. And in the basement are a supermarket, a fish market, and piles of pickles.

Before exploring, take this guided stroll along the market’s “main drag” (straight ahead from the entry). Notice the floor slopes slightly downhill to the left. Locals say that the vendors along the right wall are (appropriately enough) higher-end, with more specialty items, while the ones along the left wall are cheaper. Just inside the door, to the right as you enter, notice the small electronic scale—so shoppers can double-check to be sure the merchants didn’t cheat them.

In the first “block” of stalls, the corner showcase on the left explains how this stall has been in the same family since 1924, and includes photos of three generations. At the end of this set of stalls, in the dairy case, they sell Túró Rudi (TOO-roh ROO-dee), a semi-sweet cottage cheese covered in chocolate (in the red-and-white polka-dot wrapper). This is a favorite treat for young Hungarians—mothers get their kids to behave here by promising to buy them one. Across the “street,” the corner showcase on the right (at the end of this block) displays some favorite Hungarian spirits: Tokaji Aszú, colored (and priced) like gold and called “the wine of kings, and the king of wines” (see here); Unicum, the secret-recipe herbal liquor beloved by Hungarians and undrinkable to everyone else (see here); and the local version of schnapps, pálinka, in several fruit flavors.

In the second block, meat is on the right, and produce is on the left. At the end of this section on the left, you have a good opportunity to sample homemade strudels (rétesek) of various flavors for 230 Ft.

In the third block, you’ll see paprika on both sides. To sample before you buy, turn left before entering this block, go down the street, then turn right at the next corner. The Csárdi és Csárdi stall (on the right) lets you sample both types of paprika: sweet (édes, used for flavor) and hot (csipós, used sparingly to add some kick). Note the difference, choose your favorite, and buy some to take home (for more information, see “Paprika Primer” on here). They also sell fun little wooden spice spoons.

Back on the main paprika drag, just after the stairs on the right, hung high amidst the paprika (at the Kmetty & Kmetty stall), is a photo of Margaret Thatcher visiting this market in 1989. She expected atrocious conditions compared to English markets, but was pleasantly surprised to find this place up to snuff. This was, after all, “goulash communism” (Hungary’s pragmatic mix, which allowed a little private enterprise to keep people going). On the steps of this building, she delivered a historic speech about open society, heralding the impending arrival of the market economy.

At the fourth block, on the right, the corner showcase features another favorite Hungarian food: goose liver (libamáj)—not to be confused with the cheaper and less typical duck liver (kacsamáj); see the geese standing above the case. Goose liver comes in various forms: most traditional is packaged whole (naturel or blokk), others are pâté (parfé or püré). Hungary is, after France, the world’s second-biggest producer of foie gras.

In the fifth block, on the left, look for another local favorite: Hungarian szalámi (Pick, a brand from the town of Szeged, is a favorite here).

Reaching the sixth block, above the corner showcase on the right, you’ll see a poster showing two types of uniquely Hungarian livestock. Mangalica is a hairy pig (with a thick, curly coat resembling a sheep’s fleece) that almost went extinct, but became popular again after butchers discovered it makes great ham—and has a lower fat content than other types of pork (look for this on local menus). Szürkemarha are gray longhorn cattle. Keeping an eye on all that livestock, but not pictured here, is the distinctive Puli (or larger Komondor)—a Hungarian sheepdog with tightly curled hair that resembles dreadlocks.

• Head up the escalator at the back of the market (on the left).

Along the upstairs back wall are historic photos of the market hall (and pay WCs).

If you’re in the mood for some shopping, this is a convenient place to look—with a great selection of souvenirs both traditional (embroidery) and not-so-traditional (commie-kitsch T-shirts). While there are no real bargains here, the prices are a bit better than out along Váci utca. For tips on shopping here, see the Shopping in Budapest chapter.

The left wall (as you face the front) is lined with fun, cheap, stand-up, Hungarian-style fast-food joints and six-stool pubs. About two-thirds of the way along the hall (after the second bridge), the Lángos stand is the best eatery in the market, serving up the deep-fried snack called lángos—similar to elephant ears, but savory rather than sweet. The most typical version is sajtos tejfölös—with sour cream and cheese. You can also add garlic (fokhagyma). The Fakanál Étterem cafeteria above the main entrance is handy but pricey.

• For a less glamorous look at the market, head down the escalators near the front of the market (below the restaurant) to the...

The market basement is pungent with tanks of still-swimming carp, catfish, and perch, and piles of pickles (along the left side of the supermarket). Stop at one of the pickle stands and take a look. Hungarians pickle just about anything: peppers and cukes, of course, but also cauliflower, cabbage, beets, tomatoes, garlic, and so on. They use particularly strong vinegar, which has a powerful flavor but keeps things very crispy. Until recently—before importing fruits and vegetables became more common—most “salads” out of season were pickled items like these. Vendors are usually happy to give you a sample; consider picking up a colorful jar of mixed pickled veggies for your picnic.

• When your exploration is finished...so is this walk. Exit the hall the way you came in. Near the Great Market Hall, you have several sightseeing options. If you’d like to stroll back to Vörösmarty tér—this time along the fashionable Váci utca—you can walk straight ahead from the market. In the opposite direction, along the river behind the Great Market Hall, you can poke into the Bálna Budapest cultural center. The green Liberty Bridge next to the market leads straight to Gellért Hotel, with its famous hot-springs bath, at the foot of Gellért Hill (see the Thermal Baths chapter; trams #47 and #49 zip you right there, or it’s one stop on the M4/green Metró line).

Convenient trams connect this area to the rest of Budapest: Tram #2 runs from under the Liberty Bridge along the Danube directly back to Vigadó tér (at the promenade by Vörösmarty tér), the Chain Bridge, and the Parliament (where my Leopold Town Walk begins). Trams #47 and #49 (catch them directly in front of the market) zip to the right around the Small Boulevard to the National Museum (see here) and, beyond that, the Great Synagogue (for my Great Synagogue and Jewish Quarter Tour) and Deák tér (the starting point of my Andrássy Út Walk)—or you can simply walk around the Small Boulevard to reach these sights in about 15 minutes.