2 COPYRIGHT: GAINING AND KEEPING PROTECTION

Copyright is the source of all the reproduction rights that an artist sells in an artwork. The brief history of copyright at the end of this chapter discusses the visual arts in relation to the development of copyright and the tension between the individual’s copyright and the public’s desire for access to and use of artistic works.

On January 1, 1978, an entirely new copyright law replaced the law that had been in effect since 1909. While the changes in the 1978 law generally favored the creator, each artist must be aware of the provisions of the law to achieve maximum benefit from it and, particularly, to avoid the work-for-hire pitfall explained in chapter 4.

An important legal resource for any artist is the Copyright Office’s official Web site, located at www.copyright.gov. Artists using any Internet-enabled computer equipped with Adobe Acrobat Reader can view copyright forms, circulars, fact sheets, and other informative publications.

The fastest way to acquire these materials is to download them from the Copyright Office’s Web site. They can also be requested by mailing the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559. The Copyright Information Kit includes the Copyright Office’s regulations, the copyright application forms, and circulars explaining a great deal about copyright and the operation of the Copyright Office. Free publications that help give an overview include Circular 1, “Copyright Basics,” and Circular 2, “Publications on Copyright.” A number of circulars describe the registration procedures for various types of visual art, including Circular 40, “Copyright Registration for Works of the Visual Arts,” Circular 44, “Cartoons and Comic Strips,” and Circular 55, “Copyright Registration for Multimedia Works.” Also, the Copyright Office publishes its regulations in Circular 96, which includes provisions relevant to the visual arts. For artists wishing to purchase a copy of the complete copyright law, it can be ordered as Circular 92 for $28, or downloaded at no cost.

The Copyright Office will supply copies of any application form free of charge. In addition to being available on the Internet at www.copyright.gov/forms/, The Forms and Publications Hotline has been established by the Copyright Office to expedite requests for registration forms. This 24-hour resource can be reached at (202) 707-9100. Artists may also request forms be mailed to them using the Copyright Office’s “Forms by Mail” system, at www.copyright.gov/forms/formrequest.html.

Effective Date

Younger artists may well have created all of their work since 1978. The 1978 copyright law is no longer new, yet it is important to keep in mind that copyright transactions prior to January 1, 1978, are governed by the 1909 law. For example, if the copyright on a drawing has gone into the public domain under the 1909 law (a work in the public domain has no copyright and can be freely copied by anyone), the 1978 law would not revive this lost copyright, even if the copyright would not have gone into the public domain had the 1978 law been in effect. However, the 1978 law does govern the treatment of copyrights that were in existence on January 1, 1978.

Before 1978, copyright existed in two quite distinct forms: common law copyright and statutory copyright. Common law copyright derived from precedent in the courts, while statutory copyright derived from federal legislation and, at times, regulations implemented by the Copyright Office. Common law copyright protected works as soon as created without any copyright notice; statutory copyright protected works only when registered with the Copyright Office or published with copyright notice. Common law copyright lasted forever unless the work was published or registered; statutory copyright lasted for a twenty-eight-year term that could be renewed for an additional twenty-eight years.

The 1978 law almost entirely eliminated common law copyright, a reform that substantially simplified the copyright system. All works are now protected by statutory copyright the moment they are created in tangible form. This immediate statutory copyright protection, independent of registration or publication with copyright notice, was an important change in the law. It is not necessary to comply with any formalities to get a statutory copyright, because it comes into being as soon as an artist creates a work.

However, as explained in chapter 3, the formalities of registration and deposit are neither difficult nor expensive to comply with and do offer advantages to the artist.

What Is Copyrightable?

Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works are copyrightable. The law includes in these categories such items as “two-dimensional and three-dimensional works of fine, graphic and applied art, photographs, prints and art reproductions, maps, globes, charts, models, and technical drawings, including architectural plans.”

Audiovisual works form another category of copyrightable work and cover “works that consist of a series of related images which are intrinsically intended to be shown by the use of machines or devices such as projectors, viewers, or electronic equipment, together with accompanying sounds.” The form of an audiovisual work, be it a tape, film, or set of related slides intended to be shown together, doesn’t matter as long as the work meets the definition just given. A motion picture is a distinct type of audiovisual work that also imparts an impression of motion, something the other audiovisual works don’t have to do. The law makes clear that the soundtrack is to be copyrighted as part of the audiovisual work and not as a separate sound recording.

Work must be original and creative to be copyrightable. Originality simply means that the artist created the work and did not copy it from someone else. If, by some incredible coincidence, two artists independently created an identical work, each work would be original and copyrightable. Creative means that the work has some minimal aesthetic qualities. A child’s painting, for example, could meet this standard. All the work of a professional artist should definitely be copyrightable.

While part of a given artist’s work may infringe upon someone else’s copyrighted work, the artist’s own creative contributions may still be protected. For example, if an artist publishes a group of drawings as a book and fails to get permission to use one copyrighted drawing, the rest of the book would still be copyrightable. On the other hand, if someone were simply copying one film from another copyrighted film without permission, the entire new film would be an infringement and would not be copyrightable. If new elements are added to a work in the public domain, the new work would definitely be copyrightable. However, the copyright would only protect the new elements and not the original work that was in the public domain.

Ideas, titles, names, and short phrases are usually not copyrightable because they lack a sufficient amount of expression. Ideas can be protected by contract as discussed on pages 112–113. Likewise, style is not copyrightable, but specific pieces of art created as the expression of a style are copyrightable. Utilitarian objects are not copyrightable, but a utilitarian object incorporating an artistic motif, such as a lamp base in the form of a statue, can be copyrighted to protect the artistic material. Basic geometric shapes, such as squares and circles, are not copyrightable, but artistic combinations of these shapes can be copyrighted.

Typeface designs are also excluded from being copyrightable, but computer programs are copyrightable even if the end result of using them involves uncopyrightable typefaces. Calligraphy may be copyrightable insofar as a character is embellished into an artwork, although the Copyright Office has not issued clear guidelines on this. Calligraphy would not be copyrightable if merely expressed in the form of a guide such as an alphabet.

Computer programs and the visual images created through the use of computers are both copyrightable, unless the image itself is uncopyrightable, (for example, because it is a typeface or a basic geometric shape) in which case the computer program is still copyrightable.

If pictorial images on computer and video screens are copyrightable, what about an image composed solely of text? Is this copyrightable? This question raises the larger issue of whether the design of text in general is copyrightable. Or, for that matter, is the design of a book or magazine cover copyrightable if no picture is used? Typefaces are not copyrightable, but can an arrangement of uncopyrightable type elements create a copyrightable cover?

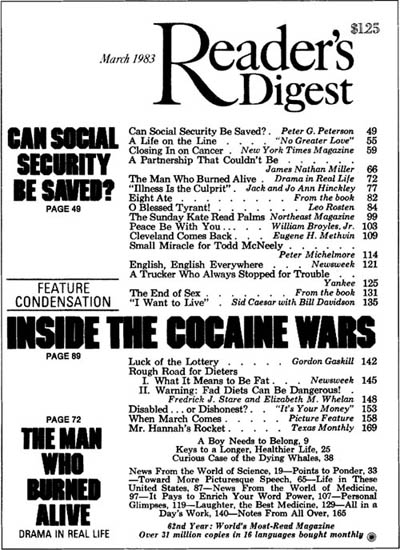

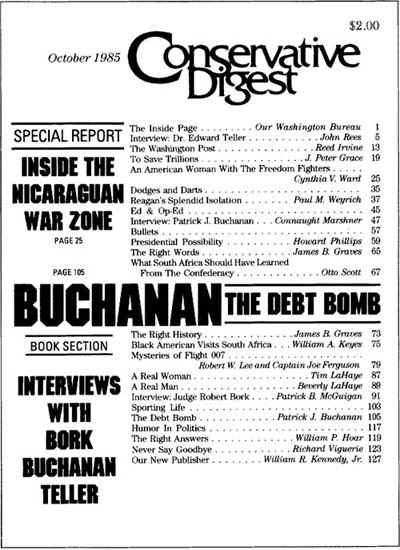

In August of 1985 Conservative Digest was acquired by a new publisher and, subsequently, changed the look of its cover to bear a close resemblance to the cover of Reader’s Digest. This new look for Conservative Digest was publicized at a press conference held at the National Press Club where a copy of the October 1985 issue was displayed.

The editor-in-chief stated that if Conservative Digest “looks like Reader’s Digest, I’m sure that Wally and Lila are somewhere up there saying, ‘That’s great, kids. Keep it up.’” Wally and Lila were DeWitt Wallace, the founder of Reader’s Digest, and his wife.

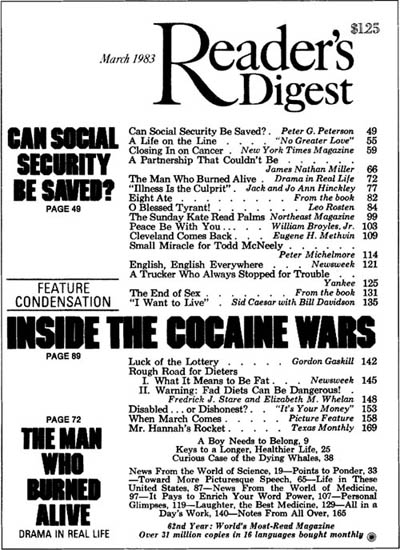

Whatever Wally and Lila might have thought, Reader’s Digest warned Conservative Digest not to use such a similar design. Despite the agreement by Conservative Digest not to use the design after the October and November issues, Reader’s Digest brought suit for copyright infringement. The two covers appear in black and white as figures 1 and 2.

Before the court could conclude that an infringement had taken place, it had to decide whether the cover of Reader’s Digest was copyrightable. The court’s opinion is quite interesting on this point: “None of the individual elements of the Reader’s Digest cover—ordinary lines, typefaces, and colors— qualifies for copyright protection. But the distinctive arrangement and layout of these elements is entitled to protection as a graphic work.”

Finding the two designs substantially similar and noting that Conservative Digest had access to the Reader’s Digest cover and thus could have copied it, the court upheld the determination that there had been a copyright infringement. However, since Conservative Digest had already stopped the infringement, the award for copyright infringement was only $500. The court refused to award attorney’s fees. Under the trade dress provisions of the Lanham Act, the court ordered that Conservative Digest make no further use of the two offending covers from October and November. (The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. v. The Conservative Digest, Inc., 642 F. Supp. 144, aff’d 821 F.2d 800).

Figure 1. Cover of Reader’s Digest.

Figure 2. Cover of Conservative Digest.

Multimedia works, which combine two or more media, are becoming more prevalent, especially online and also as CD-ROMs. Such works are certainly copyrightable. A helpful publication for such works is Circular 66, “Copyright Registration for Online Works.”

Who Can Benefit from Copyright?

If works are unpublished, the law protects them without regard for the artist’s nationality or where the artist lives. If works are published, the law will protect them if one or more of the artists is (1) a national or permanent resident of the United States; (2) a stateless person; or (3) a national or a permanent resident of a nation covered by a copyright treaty with the United States or by a presidential proclamation.

The United States is a party to the Universal Copyright Convention, so publication in any nation that is a party to that Convention will also gain protection in the United States. The copyright notice for the Universal Copyright Convention must include the symbol ©, the artist’s full name, and the year of first publication. Thus, the short form notice using the artist’s initials, (© JA, discussed on page 12) should be avoided when protection is desired under the Universal Copyright Convention. For the Buenos Aires Convention, covering many countries in the Western Hemisphere, the phrase “All rights reserved” should be added to the notice.

Because the United States joined the Berne Union on March 1, 1989, it is no longer necessary for artists in the United States to publish simultaneously in a Berne Union country to gain protection under the Berne Convention. In fact, because the Berne Convention forbids member countries from imposing copyright formalities as a condition of copyright protection for the works of foreign authors, a number of changes have been made in the United States copyright law. These changes will be described in relation to the appropriate sections of the text.

Details of the international copyright relations of the United States can be obtained from the Copyright Office in Circular 38a, “International Copyright Relations of the United States.” While most countries belong to both the Berne Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention, many belong to the Berne Convention but not to the Universal Copyright Convention and a few belong to the Universal Copyright Convention but not the Berne Convention. The wisest course is to obtain protection under both conventions, if possible.

Manufacturing Requirement

The manufacturing requirement expired on June 30, 1986, so there is no longer any requirement that books or pictorial or graphic works be manufactured in the United States.

Term of Copyright

Recent legislation has extended the various copyright terms. If the artist is not doing work for hire, the term will generally be the artist’s life plus seventy years. The additional complexity wrought by legislative changes to the law is discussed at length in Circular 15a. Also, a convenient reference chart, compiled by the Cornell Law School, can help to demystify the statutory intricacies of term length by clearly describing what works are protected, and what works are in the public domain. It is available at copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm#Footnote_1.

The term of copyright under the 1978 law had been the artist’s life plus fifty years. The 1909 copyright law had an original twenty-eight-year term and a renewal term of twenty-eight years, so the life-plus-seventy term is much longer. For works created anonymously, under a pseudonym or as a work for hire, the term shall be either ninety-five years from first publication of the work or 120 years from its creation, whichever period is shorter. The Copyright Office maintains records as to when an artist dies, but a presumption exists that a copyright has expired if ninety-five years have passed and the records disclose no information indicating the copyright term might still be in effect. If the name of an artist who has created a work anonymously or using a pseudonym is recorded with the Copyright Office, the copyright term then runs for the artist’s life plus seventy years.

The term of copyright for a jointly created work is the life of the last surviving artist plus seventy years. A joint work is defined as a work prepared by two or more artists with the intention that their contributions be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.

Copyrights in their renewal term that would have expired on or after September 19, 1962, were extended due to the deliberations over the revision of the copyright law. They fall under the general rule that the terms of statutory copyrights in existence on January 1, 1978, are extended to seventy-five years and, by the more recent legislation, to ninety-five years.

However, any copyrights obtained prior to 1978 that were still in their first twenty-eight-year term would have had to be renewed on Form RE in order to benefit from the extension to what has become a total term of ninety-five years. A 1992 amendment waived this renewal requirement, so that all works copyrighted between January 1, 1964, and December 31, 1977, automatically have their term extended by sixty-seven years. However, there are benefits to filing Form RE and paying the one-hundred-and-fifteen dollar fee for renewal, including that the renewal certificate is considered proof that the copyright is valid and the facts stated in the certificate are true. Circular 15, “Renewal of Copyright,” offers additional information about copyright renewal.

Circular 15t, “Extension of Copyright Terms,” discusses the extended terms of copyrights in existence on January 1, 1978, whether the copyright was in its first twenty-eight-year term or in its renewal term.

Since common law copyright has basically been eliminated, all works protected by common law copyright as of January 1, 1978, will have a statutory copyright term of the artist’s life plus seventy years. In no event, however, will such a copyright previously protected under the common law expire prior to December 31, 2002, and, if the work is published, the copyright will extend at least until December 31, 2047.

The 1978 law provides that all copyright terms will run through December 31 of the year in which they are scheduled to expire. This will greatly simplify determining a copyright’s term and, when necessary, renewing a copyright.

Exclusive Rights

The owner of a copyright has the exclusive rights to reproduce the work, sell and distribute the work, prepare derivative works, perform the work publicly, and display the work publicly. A derivative work adapts or transforms an earlier work, such as using the image from a painting for a picture on the front of a tee shirt, taking an old drawing and adding new elements to it so that the new drawing would be a substantial variation from the original drawing, or making a novel into a film. The right to sell and distribute the work doesn’t prevent someone who has purchased a lawfully made copy from reselling it.

The right to display the work does not prevent the owner of a copy of the work from displaying it directly or with the aid of a projector to people present at the place of display, such as exhibiting a fine print in a gallery. For an audiovisual work, including a motion picture, a display is defined as showing its images nonsequentially. The owner of a copy could do this publicly. Performing an audiovisual work, which is showing its images sequentially, would be allowed only if the owner of the copy did it in private. To perform the work publicly, either in a public place or to an audience including a substantial number of people besides the family and its normal circle of friends, permission of the copyright owner would be needed. If a gallery or museum does not own copyright-protected art that it wishes to display, it will need the permission of the copyright owner.

Each of the exclusive rights belonging to the copyright owner can be subdivided. For example, the reproduction rights sold might be “first North American serial rights” instead of “all rights.” All rights would be the entire copyright. First North American serial rights is a subdivided part of the exclusive right to authorize reproduction of the work. It is still an exclusive right, because it gives a magazine the right to be first to publish the work in a given geographical area. It is important to understand how to subdivide rights, because this is how the artist limits what rights are transferred to the other party and retains the greatest possible amount of rights for future use.

There are some limited exceptions to the exclusive rights of the copyright owner. Both fair use and compulsory licensing, discussed on pages 47–56, are statutory limitations on exclusive rights that set forth when an individual or company can use a copyrighted work without asking permission of the copyright owner. As a general rule, however, anyone using a work in violation of the copyright owner’s exclusive rights is an infringer who must pay damages and can be restrained from continuing the infringement.

Transfers and Nonexclusive Licenses

All copyrights and subdivided parts of copyrights must be transferred in writing, except for nonexclusive licenses. This requirement of a written transfer had not been the case for common law copyrights (except in California and New York), which could be transferred verbally, and is an important protection for the artist.

An exclusive license gives someone a right that no one else can exercise. For example, an artist might give a manufacturer the right to be the only maker and distributor of a certain tee shirt design for five years in the United States. This would be giving an exclusive license to the manufacturer. The exclusivity could be increased or decreased based on duration of the license, geographic extent of the license, and types of products or uses to be permitted. The contractual limitations that can be imposed, along with model contract forms, are discussed in chapter 15

On the other hand, nonexclusive licenses allow two parties to do the same thing. For example, an artist could verbally give two magazines “simultaneous rights.” Such rights are not exclusive but specifically permit giving the same rights to other magazines at the same time and for the same area.

Since nonexclusive licenses can be transferred verbally, it’s necessary to watch out for publishers or manufacturers who try to get more than a one-time use of artwork through masthead notices or memoranda that might create an implied agreement. The additional uses would be nonexclusive, but the artist would not be paid again. For example, a store might purchase the right to use copies of a work in a window display, but later want to use the same work in printed advertising. The artist should know exactly what rights are being sold, preferably by having them detailed in a purchase order obtained prior to doing the work. If there is no express agreement when dealing with a magazine or other collective work, the law provides a presumption as to what rights are transferred (discussed later in this chapter). Even when dealing with nonexclusive licenses, the wisest course is to use written contracts. Otherwise, memories fade and conflicts are more likely. Also, the fact that a nonexclusive license is written may protect the recipient of the license if a conflicting transfer is made to another party.

Copies of documents recording transfers of copyrights or exclusive licenses should be filed with the Copyright Office by the person receiving the transfer to protect that person’s ownership rights. This filing should be done within one month if the transfer took place in the United States and within two months if the transfer took place outside of the United States. Nonexclusive licenses can also be recorded with the Copyright Office. Circular 12, “Recordation of Transfers and Other Documents,” gives details about recordation.

A form for the assignment of all right, title, and interest in a copyright is included here. In general, it should not be used to sell rights, since limited rights transfers are far better for the artist. However, this form can be used when the artist is reacquiring rights in a copyright— for example, if a right granted reverts back to the artist by contract.

Copyright Assignment Form

For valuable consideration, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, (name of party assigning the copyright), whose offices are located at (address), does hereby transfer and assign to (name of party receiving the copyright), whose offices are located at (address), his or her heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns, all its right, title, and interest in the copyrights in the works described as follows: (describe work, including registration number, if work has been registered) ____________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________, including any statutory copyright together with the right to secure renewals and extensions of such copyright throughout the world, for the full term of said copyright or statutory copyright and any renewal or extension of same that is or may be granted throughout the world.

In Witness Whereof, (name of party assigning the copyright) has executed this instrument by the signature of its duly authorized corporate officer on the _______ day of ___________, 20____.

ABC Corporation

By:___________________________

Authorized Signature

____________________________

Name Printed or Typed

____________________________

Title

Termination

Another significant provision of the 1978 law is the artist’s right to terminate transfers of either exclusive or nonexclusive rights. If, after January 1, 1978, an artist grants exclusive or nonexclusive rights in a copyright, the artist has the right to terminate this grant during a five-year period starting at the end of thirty-five years after the execution of the grant or, if the grant includes the right of publication, during a five-year period beginning at the end of thirty-five years from the date of publication or forty years from the date of execution of the grant, whichever term ends earlier.

Similarly, if before January 1, 1978, the artist or the artist’s surviving family members made a grant of the renewal right in one of the artist’s copyrights, that grant can be terminated during a five-year period starting fifty-six years after the copyright was first obtained. However, the artist has no right of termination in transfers by will or in works for hire.

The mechanics of termination involve giving notice two to ten years prior to the termination date and complying with regulations the Copyright Office can provide, but the important point is to remember that such a right exists. The purpose of the right of termination is to provide creators the opportunity to share in an unexpected appreciation in the value of what has been transferred.

The twenty-year extension of the copyright term affects the right of termination. If the right of termination has not been exercised, then it may be exercised with respect to the twenty-year extension during the five-year period commencing at the end of seventy-five years from when the copyright was secured.

Selling to Magazines and Other Collective Works

Magazines, newspapers, anthologies, encyclopedias—anything in which a number of separate contributions are combined together—are defined as “collective works.” The law specifically provides that the copyright in each contribution is separate from the copyright in the entire collective work. The copyright in a contribution belongs to the contributor who can give the owner of the copyright in the entire work whatever rights the contributor wishes in return for compensation.

However, especially where magazines are concerned, it is not uncommon for a contribution to be published without any express agreement ever being made as to what rights are being transferred to the magazine. The 1978 law deals with this situation by providing that, in a case where there is no express agreement, the owner of copyright in the collective work gets the following rights: (1) the nonexclusive right to use the work in the issue of the collective work for which it was contributed; (2) the right to use the contribution in a revision of that collective work; and (3) the right to use the contribution in any later collective work in the same series.

For example, a drawing is contributed to a magazine without any agreement with respect to what rights are being transferred. The magazine can now use that drawing in one issue and again in later issues, but it cannot publish that drawing in a different magazine. Magazines are not usually revised, but anthologies and encyclopedias are. In that case the drawing could be used in the original issue of the anthology or encyclopedia and any later revisions, but it couldn’t be used for a new anthology or a different encyclopedia.

Of course, only nonexclusive rights are transferred to the magazine or other collective work, so the drawing could be contributed elsewhere at the same time. The artist will have to weigh whether this is practical in terms of keeping the good will of the various clients.

In August of 1997, the court interpreted copyright law as applied to electronic publication in the case of Tasini v. New York Times (972 F. Supp. 804). The plaintiffs, all freelance writers, claimed that the defendants, all large publishing companies, had infringed their copyrights by placing the contents of their periodicals on electronic databases and CD-ROMs without first securing the permission of the plaintiffs whose contributions were included in those periodicals. The plaintiffs argued that all parties implicitly understood that the authors were selling only first North American Serial Rights, and reserving secondary rights such as syndication, translations, and anthologies for separate sale. The court, under then-district judge Sonia Sotomayor, decided in favor of the publishers, finding the articles originally appearing in the magazine to be substantially similar to the online and disc versions, and thus construing them to be permissible “revisions” under the Copyright Act. On appeal, however, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed in favor of the writers, and the Supreme Court affirmed that view in New York Times Co., Inc. v. Tasini, (533 U.S. 483). Justice Ginsburg held that electronic databases containing individual articles from multiple editions of periodicals could not be reproduced and distributed as part of revisions of individual periodical issues from which articles were taken. Therefore publishers of periodicals could not relicense individual articles to databases under a collective works theory, unless the individual authors transferred copyrights or other rights to the individual articles.

The rule of Tasini, which dealt with written works, has been expanded to include photographs. In Greenberg v. National Geographic, (533 F.3d 1244), photographer Jerry Greenberg brought a lawsuit against National Geographic, which had featured Greenberg’s images in four issues of its monthly magazine. In 1996, National Geographic sought to release a digital archive of its magazines on CD-ROM. This 30-disc archive would contain electronic versions of all published articles from 1888 to 1996, and would include reduced-resolution samples of all the photographs featured in those articles. Greenberg sued, alleging that he deserved additional compensation for this use. In essence, Greenberg argued that he gave National Geographic permission to publish pictures in only four printed magazine editions, and that the proposed digital collection was a new and categorically different work that required additional permission. After a long and circuitous journey through the federal courts, Greenberg ultimately lost his case. The court held that the digital archive was merely a “revision” of National Geographic’s collection of magazines. Though the medium was different, the collective works themselves remained unchanged, and thus, the CD-ROM collection was nothing more than an alternative version of National Geographic’s amassed paper magazine archive.

The fundamental difference between Greenberg and Tasini was that in the former case, National Geographic’s digital archive did not separate Greenberg’s photos from the articles in which they were featured. By contrast, the parsing of newspaper articles from their original published context into various searchable databases was deemed to infringe the rights of various authors in Tasini. In keeping with this the court in Greenberg held that National Geographic did infringe Greenberg’s copyright if it displayed the photos outside of the articles in which they appeared. In particular, the Greenberg court held that National Geographic’s introductory sequence, featuring animated logos, covers, photos, and music, were not privileged revisions, and that any attempt to use Greenberg’s photos in that sequence would infringe his copyright.

The best solution is simply to have a written agreement signed by the artist or his or her authorized agent transferring limited rights and dealing with whether any electronic rights are included in the transfer. For example, the limited rights might be defined as “first North America rights for non-electronic usage only” in the contribution to the collective work. This transfers exclusive first-time rights in North America, but it has the advantage of restricting the magazine or other collective work from making subsequent uses of the contribution without payment or from making any electronic use. It also makes the sale governed by terms agreed to and understood by both parties, instead of by a law that may not satisfactorily achieve the end result desired by either party. The need for a signed written transfer can be satisfied by a simple letter stating: “This is to confirm that in return for your agreement to pay me $___________, I am transferring to you first North American rights in my work titled ___________ described as follows:_________________ for non-electronic usage only in your magazine titled:____________________. For purposes of this agreement, electronic rights are defined as rights in the digitized form of works that can be encoded, stored, and retrieved from such media as computer disks, CD-ROM, computer databases, and network servers.”

Entering Contests

The artist may want to enter contests sponsored by professional organizations or companies. Many contests pose no problem, but any application form should be closely scrutinized with respect to reproduction rights. Does winning, or even entering, the contest, require that the artist transfer the copyright to the sponsor? If so, the contest should not be entered.

If the contest requires that exclusive rights be transferred to the sponsor in the event the artist wins, then the artist must evaluate whether this transfer of rights is reasonable. The sponsor should seek only limited rights, such as the right to publish the art in a book of contest winners or to make a poster for a certain specified distribution. If the sponsor seeks more than this, the artist should demand fair compensation for the additional rights that appear unnecessary to fulfill the purpose of the contest.

In addition, if the sponsor seeks free art to use for commercial purposes, such as promoting or advertising its products, then the artist should be especially wary of entering. Not only does this situation appear very similar to working on speculation, which should be anathema to all artists, but it would require a prize that would be a fair fee for the winner.

Just as the artist safeguards his or her copyright, so ownership should be maintained over the physical artwork embodying the copyright. Contest applications must be read carefully and contests entered only after thoroughly weighing whether the impact of the contest on ownership of the copyright and the physical art is fair and ethical.

Ownership of the Physical Work

Copyright is completely separate from ownership of a physical artwork. An artist can often sell the physical work verbally, but the copyright or any exclusive license must always be transferred in writing and the artist or the artist’s authorized agent must sign that transfer. Because prior to 1978 it appeared the sale of an artwork might transfer the common law copyright to the purchaser, New York and California have enacted statutes reserving the common law copyright to the artist unless a written agreement transfers the common law copyright to the purchaser. The New York statute covers sales of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and graphic works. The broader California statute covers commissions as well as sales of fine art (defined to include mosaics, photography, crafts, and mixed media) and also includes the categories covered under the New York statute. These statutes will continue to be of importance with respect to sales that took place prior to 1978. After 1978, the copyright law provides the same protection and has been held to preempt these laws.

Publication with Copyright Notice

Due to joining the Berne Union, as of March 1, 1989, the United States copyright law no longer requires copyright notice to be placed on published works. In fact, however, most copyright proprietors will continue to use copyright notice. The notice warns potential infringers of the copyright. Use of the copyright notice prevents an infringer from being allowed to ask the court for mitigation of damages on the grounds that the infringement was innocent. Also, the Universal Copyright Convention still requires copyright notice. As discussed earlier, a number of nations who signed the Universal Copyright Convention did not also sign the Berne Convention.

In some cases, the time when publication occurs can be confusing. Publication in the 1978 law basically means public distribution. This occurs when one or more copies of a work are distributed to people who are not restricted from disclosing the work’s content to others. Distribution can take place by sale, rental, lease, lending, or other transfer of copies to the public. Also, offering copies to a group of people for the purpose of further distribution, public performance, or public display is a publication. In circulating copies of a work to publishers or other potential purchasers, it would be wise to indicate on the copies that the contents are not to be disclosed to the public without the artist’s consent. Even if this is not done, however, it should be implicit that such public disclosure is not to be allowed.

The history of the law’s enactment (in the form of a statement by Congressman Kastenmeier in the Congressional Record) indicated that Congress did not intend for unique art works, those that are one of a kind, to be considered published when sold or offered for sale in such traditional ways as through an art dealer, gallery, or auction house. Works intended to be sold in multiple copies, however, would be considered published if publicly distributed or offered for sale to the public, even if the offering for sale occurs at a time when only a single prototype exists.

But unique works should be registered in any case, since they can still be infringed by someone who has access to them. Also, some experts believe that unique works are published when offered for sale by a dealer, gallery, or auction house. To warn the public of the artist’s copyright and to avoid taking any chances that a court in the future might decide that unique works can be published, copyright notice should be placed on such works as soon as they are created. This does not change the term of copyright protection, but it prevents having to worry about ambiguities in the definition of publication.

For works created prior to 1978, it is worthwhile to discuss the meaning of “publication” under the old law. For both common law and statutory purposes, publication generally occurred when copies of the work were offered for sale, sold, or publicly distributed by the copyright owner or under his or her authority. However, artworks are frequently first exhibited or offered for sale not through copies but by use of an original work or works. The consensus was that the exhibition of an uncopyrighted artwork would not be a publication if copying of the work, usually by photography, was prohibited and if this prohibition was enforced at the exhibition. On the other hand, such an exhibition would have been a publication if copies could be freely made or disseminated. Authority was also divided over whether the sale of an original uncopyrighted artwork was a publication that would bring an end to common law copyright protection. Despite this, both New York and California enacted the statutes discussed earlier, which provided that the sale of an uncopyrighted artwork did not transfer the right of reproduction to the buyer unless a written agreement was signed by the artist or the artist’s agent expressly transferring such right of reproduction.

Form of Copyright Notice

The form of the copyright notice is as follows: Copyright or Copr. or ©, the artist’s name or an abbreviation by which that name can be recognized or an alternative designation by which the artist is known, and the year date of publication (or the year date of creation, if the work is unpublished and the artist chooses to place notice on it). Valid notice could, therefore, be ©JA 2012, if the artist’s initials were JA. In general, the Copyright Office takes the position that an artist’s initials are insufficient unless the artist is well known by his or her initials. If the artist is not well known by his or her initials, the Copyright Office will treat the notice as lacking any name. The year date can be omitted only from artwork reproduced on or in greeting cards, postcards, stationery, jewelry, dolls, toys, or any useful articles. If a work consists preponderantly of one or more works created by the United States Government, a statement indicating this must be included with the copyright notice. If this is not done, an innocent infringer will be able to ask the court to mitigate damages, which the court may do in its discretion.

Circular 3, “Copyright Notice,” discusses both the form and placement of copyright notice.

Placement of Copyright Notice

The copyright notice should be placed so as to give reasonable notice to an ordinary user of the work that it is copyrighted. The Copyright Office regulations are very liberal as to where notice can be placed, but, in fact, any reasonable placement of notice will be valid. Of course, it would be wise to follow the guidelines given in the regulations and explained here.

The notice requirements for pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works insure that the use of copyright notice will not impair the aesthetic qualities of the art.

For a two-dimensional work, such as a fine print or poster, the copyright notice can go on the front or back of the work or on any backing, mounting, matting, framing, or other material to which the work is durably attached so as to withstand normal use or in which it is permanently housed. The notice can be marked on directly or can be attached by means of a label that is cemented, sewn, or otherwise permanently attached. A slide that is not part of a series of related slides would be a two-dimensional work and the copyright notice would go on the slide’s mounting.

For a three-dimensional work, such as a sculpture, the copyright notice can be placed on any visible portion of the work or on any base, mounting, framing, or other material to which the work is permanently attached or in which it is permanently housed. Again, the notice can be marked on directly or can be attached by means of a label that is cemented, sewn, or otherwise durably attached so as to withstand normal use. If, in an unusual case, the size of the work or the special characteristics of the material composing the work make it impossible to mark notice on the work directly or by a durable label, the notice could be placed on a tag of durable material attached with sufficient permanency to remain with the work while passing through the normal channels of commerce.

If a work is reproduced on sheet-like or strip materials bearing continuous reproductions, such as wallpaper or textiles, the copyright notice may be placed in any of the following ways: (1) on the design itself; (2) on the margin, selvage, or reverse side of the material at frequent and regular intervals; (3) if the material has neither selvage nor a reverse side, then on tags or labels attached to the materials and to any spools, reels, or containers housing them so that the notice is visible during the entire time the materials pass through their normal channels of commerce.

If a work is permanently housed in a container, such as a game or puzzle, a notice reproduced on the permanent container will be acceptable.

For a contribution to a collective work, such as a magazine or anthology, the regulations state that copyright notice can be placed in any of the following ways: (1) if a contribution is on a single page, the copyright notice may be placed under the title of the contribution, next to the contribution, or anywhere on the same page as long as it is clear that the copyright notice is to go with the contribution; (2) if the contribution takes up more than one page in the collective work, the copyright notice may be placed under the title at or near the beginning of the contribution, on the first page of the body of the contribution, immediately following the end of the contribution, or on any of the pages containing the contribution as long as the contribution is less than twenty pages and it is clear the notice applies to the contribution; (3) as an alternative to numbers (1) or (2), the copyright notice may be placed on the page bearing the notice for the collective work as a whole or on a clearly identified and readily accessible table of contents or listing of acknowledgments appearing either at the front or back of the collective work as a whole. For (3), there must be a separate listing of the contribution by its title or, if it has no title, by an identifying description.

For works that are reproduced in machine-readable copies, the notice can go near the title or at the end of the work on printouts. Other placements include at the user’s terminal at sign-on, on continuous display on the terminal, or on a label securely affixed to a permanent container for the copies.

For motion pictures and other audiovisual works, the copyright notice is acceptable if it is embodied in the copies by a photomechanical or electronic process so that it appears whenever the work is performed in its entirety and is located in any of the following positions: (1) with or near the title; (2) with the cast, credits, or similar information; (3) at or immediately following the beginning of the work; or (4) at or immediately preceding the end of the work. Since a series of related slides intended to be shown together is considered an audiovisual work, the notice would have to be visible when the work is performed in one of the positions just listed. There would be no requirement, however, that notice appear on the mounting of the slides as on the case of a slide that is not part of a related series. Also, a motion picture or other audiovisual work distributed to the public for private use (such as a video recording cassette) may have the notice on the container in which the work is permanently housed if that would be preferred to one of the four placements listed above.

Circular 3, “Copyright Notice,” is also helpful on this topic.

Defective Notice

Since copyright notice is permissive after March 1, 1989, works published without notice are fully protected and the provisions on defective notice are not relevant. However, the changes in the copyright law are not retroactive, so works published without copyright notice prior to March 1, 1989, may have gone into the public domain. There are two categories of pre-March 1, 1989 works that must be discussed: those published between January 1, 1978 and March 1, 1989, and those published before January 1, 1978.

Between January 1, 1978 and March 1, 1989, a copyright was not necessarily lost if the copyright notice was incorrect or omitted when authorized publication took place either in the United States or abroad. For example, if the wrong name appeared in the copyright notice, the copyright was still valid. This meant that if an artist contributed to a magazine or other collective work but there was no copyright notice in the artist’s name with the contribution, the copyright was still protected by the copyright notice in the front of the magazine even though the notice was in the publisher’s name. Notice in the publisher’s name did not, however, protect advertisements that appeared without separate notice (unless the publisher was also the advertiser). If an earlier date than the actual date of publication appeared in a copyright notice, the term of copyright was simply computed from the earlier date, but the copyright remained valid. Computing the copyright from the earlier date would not make any difference, since the term of the copyright is measured by the artist’s life plus seventy years (not a fixed time period that could be shortened by computing the term from the earlier date).

If the name or date was simply omitted from the notice, or if the date was more than one year later than the year in which publication actually occurred, the validity of the copyright was governed by the same provisions that applied to the complete omission of copyright notice. In such a case, the copyright was valid and did not go into the public domain if any one of the following three tests was met: (1) the notice was omitted from only a relatively small number of copies distributed to the public; (2) the notice was omitted from more than a relatively small number of copies, but registration was made within five years of publication and a reasonable effort was made to add notice to copies distributed in the United States that did not have notice (such a reasonable effort at least required notifying all distributors of the omission and instructing that they add the proper notice; foreign distributors did not have to be notified); or (3) the notice had been left off the copies against the artist’s written instructions that such notice appear on the work.

However, an innocent infringer who gave proof of having been misled by the type of incorrect or omitted notice discussed in the preceding paragraph would not have been liable for damages for infringing acts committed prior to receiving actual notice of the registration. Also, the court in its discretion might have allowed the infringement to continue and required the infringer to pay a reasonable licensing fee.

Prior to 1978, a defective notice usually caused the loss of copyright protection because statutory copyright for published works was obtained by publication with copyright notice. If, for example, a year later than the year of first publication was placed in the notice, copyright protection was lost. There were exceptions, however. For example, the use in the notice of a year prior to that of first publication merely reduced the copyright term but did not invalidate the copyright. Also, if copyright notice was omitted from a relatively small number of copies, the copyright continued to be valid, but an innocent infringer would not be liable for the infringement.

A Brief History of Copyright

This brief history of copyright reveals some of the underlying forces that have shaped the copyright law in force today. A tension exists between the rights of the public and the rights of the artist. Copyright is a monopoly favoring authors, artists, or right holders, and like any monopoly, it imposes limitations on the public. The artist reaps economic gains for the term of the copyright while the public is denied the fullest access to its own images and culture. In justifying this monopoly by ancient concepts of property law, copyrights are considered one category of intellectual property.

The etymological derivation of property is from the Latin word “proprius,” which means private or peculiar to oneself. Intellectual comes from the Latin verb “intellegere,” which is to choose from among, hence to understand or to know. Contained within “intellegere” is the verb “legere,” which means to gather (especially fruit) and thus to collect, to choose, and ultimately to assemble (the alphabetical characters) with the eyes and to read.

So the private inspiration that finds fruition in art is rewarded with monopoly rights that last longer than the artist’s life. Yet new means to create, store, and deliver art place pressure on the system of copyright. Arguments are made for rights of public access to and use of all imagery, perhaps on the model of a compulsory license created by statute in which copyright owners have no right to control usage but do receive a fee fixed either by voluntary arrangements or government fiat. Would the public be better served by ending copyright as a monopoly and allowing the most widespread dissemination of literature, art, and other products of the mind? Is the public’s right to access art, writing, or other forms of creative expression greater than any right that the art’s creator might assert?

To place this debate in perspective, we must remember that copyright is neither ancient nor uncontroversial. The Roman legal system, for example, had no copyright. If a man could own slaves (who might carry fabulous creations in their minds), why should the ownership of words be separate from the ownership of the parchment containing the words? Trained slaves took dictation to create thousands of copies of popular works for sale at low prices. The poet Martial complained that he received nothing when his works were sold. Even if works could be sold, as were the plays written by Terence, no protection existed against piracy. The profits from any sales of the copied manuscripts went to the property owner, not the author.

Indeed, this collective view of creativity held sway through the Middle Ages. Religious literature predominated; individual creativity was not rewarded. The reproduction of manuscripts rested in the dominion of the Church, and it was only with the rise of the great universities in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that lay writers began producing works on secular subjects. Extensive copying by trained scribes again became the norm, with only the publishers, or “stationarii” as they were called, gaining any profit. Even before the introduction of block printing into the West in the fifteenth century, the publishers had formed a Brotherhood of Manuscript Producers in 1357 and were soon given a charter by the Lord Mayor of London. Johannes Gutenberg’s introduction of the printing press to the Western world in 1437 gave individual authors an even greater opportunity for self-expression. The printer’s movable type foreshadowed the author’s copyright protection.

William Caxton introduced these printing techniques to England in 1476, which led to an even greater demand for books. Seven years later, Richard III lifted the restrictions against aliens if those aliens happened to be printers. Within fifty years, however, the supply of books had far exceeded the demand and Henry VIII passed a new law providing that no person in England could legally purchase a book bound in a foreign nation (this was the forerunner to the manufacturing clause that finally expired in 1986).

At about this time the Brotherhood of Manuscript Producers, now known as the Stationers’ Company, was given a charter—that is, a monopoly—over publishing in England. No author could publish except with a publisher belonging to the Stationers’ Company. This served the dual purpose of prohibiting any writing that was either seditious to the Crown or heretical to the Church. The right of ownership was not in the author’s creation, but rather in the right to make copies of that creation. Secret presses came into existence, but the Stationers’ Company sought to maintain its monopoly with the aid of repressive decrees from the notorious Star Chamber.

Due largely to the monopoly of the Stationers’ Company, a recognition had come into being of a right to copy, which might also be called a common law copyright—that is, a right supposedly existing from usages and customs of immemorial antiquity as interpreted by the courts. With this concept of property apart from the physical manuscript established, the Stationers’ Company objected vehemently when its charter and powers expired in 1694 and Scotch printers began reprinting their titles. The stationers pushed for a new law, but this law, enacted in 1710 and called the Statute of Anne, was largely drafted by two authors, Joseph Addison and Jonathan Swift. The result was a law that protected authors as well as publishers by the creation of statutory copyright (that is, copyright protected under a statute). At this point authors had something to sell on the market, a copyright that had been created to encourage “learned men to compose and write useful books.”

The intellectual property manifested by words had been protected, but what of images? Preyed upon repeatedly by plagiarists who undersold his own prints, William Hogarth and other artists petitioned Parliament to extend copyright protection to pictures and prints. In 1735 this protection was granted, but not before the pirates created their own version of The Rake’s Progress by sending their agents posing as potential buyers to Hogarth’s house to see the series of prints. These agents then attempted to remember and reproduce what they had seen. Their efforts were, as Hogarth said, “executed most wretchedly both in Design and Drawing….”

The copyright laws of the United States stand on this structure, originally built in England. The Confederation of States had no power to legislate with respect to copyright. Between 1783 and 1789 Noah Webster successfully lobbied in twelve states for the passage of copyright laws. Finally, the Federal Constitution provided that “The Congress shall have the power… To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

In 1790 Congress enacted our first federal copyright statute providing copyright for an initial term of fourteen years plus a renewal term of fourteen years. It applied to the making of copies of books, maps, and charts. This law was amended in 1802 to apply to engraving and etching of historical and other prints. In 1831 the initial term of copyright was lengthened to twenty-eight years. In 1865 the law was amended to include photographs and negatives. In 1870 it was revised to cover paintings, drawings, statuaries, and models or designs of works of the fine arts. From the artist’s viewpoint, it is interesting that drawings and paintings were added as a postscript to the copyright law.

In 1909 the copyright law was revised again. The initial term of copyright remained twenty-eight years and the renewal term was lengthened to twenty-eight years for potential protection of fifty-six years. In fact, statutory copyrights that would have expired at the end of the renewal term on or after September 19, 1962, were extended to a term of seventy-five years from the date copyright was originally obtained. Recent legislation has extended the term to the artist’s life plus seventy years for works created after 1977. For works created before 1978 that must be renewed, the total term has been extended to ninety-five years.

Radio, television, motion pictures, satellites, and other technological innovations required revision of the 1909 law. After a long gestation, the complete revision of the law took effect on January 1, 1978. No doubt future revisions lie ahead as the Internet and other new tools to make, store, and deliver creative works shape the copyright needs of creators, users, and society itself. In this vein, legislative efforts to deal with emerging problems created by the Internet are discussed on page 64.

At first blush, the copyright law appears to limit the public’s ability to benefit from artistic and literary works. However, the purpose of copyright is to benefit the public as well as the author. Copyright laws are founded on the assumption that granting authors limited economic monopolies over their own creations encourages them to create innovative new works of creative expression. This stimulus to authorship, provided by economic incentives, ultimately bequests a richer cultural legacy to the public than would a system that allowed the public to pirate at will. Society renounces piracy, because it believes that the cultural wealth increases when the artists and authors that create that wealth have incentive to create it in the first place. Viewed in this way, the conflict between the artist and the public vanishes. For what is the artist but a part of society? And what are the artist’s freedom and copyright but a reflection of the society’s liberty and legacy?