4

Back to the Land, On to the Scene

How Scenes Drive Economic Development

This chapter shows how scenes are factors of production; they are key determinants of economic success or failure. Even if labor and capital dominate much of economic theory, these do not explain specifics of why, or especially where, growth occurs. The chapter comes in three major sections.

The first, on concepts and theory, traces an intellectual movement from “land” as the physical gifts of nature to “scene” as the cultural and aesthetic characteristics of a locale. The second articulates several propositions about how variations in scenes should bring variations in economic growth. And the third tests these propositions by joining the scenes measures we surveyed in chapter 3 with economic data on jobs, wages, rents, population, patents, human capital, and more.

While we investigate several specific hypotheses about how the characteristics of the scenescape relate to economic growth, they are offered to illustrate a larger point that goes beyond any one specific finding: Scenes are a “new” classical factor of production that many of today’s businesses ignore to their peril. If for some businesses (like farming) the qualities of the soil are critical for success or failure, for others (like software firms) the qualities of the scene where one operates are similarly crucial. To show this, we join scenes measures with classic variables from economics and geography, revealing how scenes can substantially influence local economic performance. While many “know” that scenes are key factors of production, including them in quantitative models shows how their economic contributions are more than anecdotal.

The Disappearance, Reappearance, and Transformation of “Land”

Classics help identify fundamental assumptions and imagine alternatives. Key classics of modern social and economic thought in particular often reveal a picture of the world opaque to the links between scenes and economic growth. But they also suggest why, and how, to realign our conceptual grid to include scenes more clearly.

The basic plot of the story that follows is the articulation, disappearance, reappearance, and transformation of “land.” We begin briefly with the classical theorists Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who first articulated land as a key economic concept. Then we see how land more or less drops out of the picture for Marx, or is pushed backstage, with big consequences for later theories, especially of globalization. “Land” starts to creep back in, in a transformed, culturally infused meaning, with authors like Alfred Marshall, Max Weber, and Talcott Parsons. Next, the “scene” extends and adds much more concrete empirical meaning to what Marshall, Weber, and Parsons started.

Factors of Production as Social Theory

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations is not just a classic in economics but also a classic of modern social thought. Perhaps more than any other book, it defined core aspects of a modern commercial order. Smith’s pioneering analyses of money and markets, capital accumulation, and the division of labor surely have much to do with the book’s enduring power. But rhetoric matters too. Indeed, Smith crafted a kind of sacred language of commerce. The aristocrat, whose leisure and martial virtues had hitherto been objects of reverence, becomes a perverse, if in certain ways lovable, profligate. The hard-working, frugal, entrepreneurial artisans and traders, whose savings lead to the steady accumulation of capital that calls forth the productive capacities of the nation, take the spotlight on the stage of history.

The Wealth of Nations is in many ways like the sociological equivalent of early astronomy. Instead of looking to the sky and constructing order from randomness, here we see a framework to reinterpret the social world. There is a socio-logic to the rise and fall of business sectors, movements of prices, rewards for various types of work, productivities of different workplaces, and conflicts between classes.

Smith divided society into three great classes: landlords, workers, and capitalists. This was based on a theory of the distribution of the “proceeds of labor” that make up “national wealth”—the total goods and services produced in a given nation. That wealth can go to profits, to wages, or to rents. Profits are the proceeds of capital, wages of labor, and rents of land—the three classical “factors of production” (Alfred Marshall, to whom we will return, and Joseph Schumpeter, added a fourth, known variously by Marshall’s terms “management” and “business power” or Schumpeter’s “entrepreneurship.”)

On this basis, Smith developed, among other things, a theory of social conflict, based on the interests of the three great classes and their ability to act on and understand their interests. For people only familiar with the received view of Smith as Godfather of Kapitalismus, his theory of social conflict comes as a shock. For, in broadest outlines, Smith argues that the interests of capital are inherently hostile to the overall good of society while those of the workers are inherently aligned with those of society. Workers’ main interest is in higher wages, and these, Smith argues, tend to at once signal increasing productivity and to create the basis for a broadly shared prosperity that places the general interests of consumers above the particular interests of any given firm or sector. The owners of capital, by contrast, tend to elevate the interests of producers over those of consumers to keep profits high, even—or especially—if that means offering lower quality goods for higher prices. The problem is that owners know and can act on their interests while workers typically do not and cannot.

Landlords are in a strange middle position for Smith. Their interests ultimately align with those of the nation and of the workers. “Every increase in the real wealth of the society, every increase in the quantity of useful labor employed within it, tends indirectly to raise the real rent of land” (A. Smith 1776, bk. 1, ch. 11). But they tend to misrecognize those interests. Because they live by sitting back and collecting rent rather than by constantly scheming up ways to make profits, landlords—“country gentlemen,” as Smith often calls them—are less likely than are capitalists to take the long view and to lobby for it in the halls of power, despite their ample time and education. They become blinded by the allure of renting their land to high-profit businesses and by the cunning rhetoric of the owners of capital. “It is by this superior knowledge of [the proprietors’] own interest that they have frequently imposed upon [the country gentleman’s] generosity, and persuaded him to give up both his own interest and that of the public, from a very simple but honest conviction, that their interest, and not his, was the interest of the public” (ibid.).

The result is that for Smith landholders tend in the end to align, against their own interests, with the owners of capital to keep down the wages of labor. This political alignment from Smith’s perspective in turn would explain the historical association of landlords with the forces arrayed against the public interest in broad-based growth. However, by articulating how this coalition is based on misrecognizing the landlord’s true interests, and thus the role of land in generating the wealth of nations, Smith also suggests that a fuller accounting of land as a factor of production might produce a broader assessment of its significance.

Land as the Value of Place

To do so, we turn to others who built on the foundations Smith laid, starting (briefly) with another great early modern economic and social thinker, David Ricardo. The details and intricacies of Ricardo’s theory need not detain us, such as his idea that rent is determined by the “last” plot of land brought into cultivation.1 More important is the underlying intuitive logic.

Take two farmers. Each works about the same amount of time per day and has more or less the same set of tools. That is, labor and capital are the same. Put Farmer #1 on rich, fertile soil and Farmer #2 on dry, cracked soil. Farmer #1 will be more productive. That added value is what land contributes as a factor of production, and when land is scarce, that value can generate a rent.

This is an intuitive, not particularly “deep” observation, though Ricardo did derive some counterintuitive and far-ranging consequences from it. What is important in the present context, however, is that the concept of land focuses analytical attention to the specific characteristics of a locality—at first how fertile the soil is, but also air quality, sunlight, and then qualities like distance and access to markets and suppliers (via, for instance, waterways or railroads). Including land as a factor of production in this way naturally puts on the analytical radar questions about how local area characteristics influence economic success or failure.

The Eclipse of Land as the Eclipse of Distance

Marx wrote his masterwork, Capital, after years of reading Smith and Ricardo, among others, while sitting in the British Museum Reading Room in London. It is a book that defies summary. This is not least because, in contrast to the straightforward style of his Anglophone predecessors, there are multiple levels of irony and bitter humor at work in Capital, which is as much a literary work as a work of political economy.

Be that as it may, when one turns to Capital after Smith and Ricardo, one is struck by the fact that land has for the most part dropped out of the story. There is almost no discussion of rent and land in the first two (massive) volumes of the book. The topic does arise in the third volume, which is a collection of Marx’s unpublished notes compiled (and often extensively edited) by Engels after the death of the Master. And Marx further discusses land and rent in significant detail in Theories of Surplus Value, which is mostly a collection of notes about classical political economists (like Smith and Ricardo) that was not published in its entirety until 1956. Marx, that is, was never able in his lifetime to integrate a theory of land and rent with his more famous discussions of capital and labor. It is perhaps telling that while the size of the literature on Marx may rival that of the Bible and Shakespeare, a recent survey of articles on Marx’s theory of rent by economist Miguel Ramirez (2009) turned up only a dozen or so items. Geographers, most notably David Harvey in Limits to Capital, have endeavored to extend Marx’s thoughts on the topic, but even Harvey calls Marx’s ideas “tentative thoughts set down in the process of discovery” (1982, 330).2

With land offstage, capital and labor, aka bourgeoisie and proletariat, steal the show. As Marx describes it in The German Ideology, the precapitalist, premodern world was one of rich diversity, filled with barons, knights, monks, bishops, kings, artisans, shopkeepers, traders, troubadours, and much, much more. While social conflict was rampant, it was also complex, not reducible to any single opposition.

The capitalist order simplifies all of this. Capitalism acts like a solvent, clearing away mystical distinctions, antique metaphysics, and hoary sentimentality. Everything must become capital, and capital must mediate everything.3 All that is left is capital—and what it cannot do without in order to put itself into motion, labor. The ensuing clash between bourgeois and proletariat, in which capital aims to transform humanity’s most essential capacity, labor, into a tool for its own purposes, brings the class struggle that has defined the history of all hitherto existing history to its sharpest, culminating point.

This is already a strong contrast to Smith, who was most at home in a rich and diverse social environment. The Wealth of Nations gives pride of place to the butcher, the brewer, and the baker, staple figures in a small town and dense urban environment. And Smith thought the life of the farmer, in the country air and with his property under his own gaze, the ideal to which any healthy person would be drawn. The merchants and great manufacturers, though admirable in their own way, nevertheless provoked in Smith a kind of anxiety, in no small measure because they were untethered to any particular place, at a distance from their property and fellows, disconnected from the local habits and customs of those with whom they worked.

Marx likely saw this as a bit of sentimentality on Smith’s part. Merchants and the master industrialists represented the future, a future that was black and white. As Marx had already made clear in his early Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, the moral and economic significance of rich cultural diversity—embodied (for Smith) in local shop owners or the country gentlemen—is the stuff of feudalism. It would not last against the onslaught of capital. “Large landed property, as we see in England, has already cast off its feudal character and adopted an industrial character insofar as it is aiming to make as much money as possible” (Marx [1844] 1959). And so, the third principal character in Smith’s theory of society is nudged ever closer to the cliff.

To be sure, Marx had his own, powerful reasons for downplaying land. There were economic-technological reasons. If land seemed somehow different from industry, this was primarily because capital had been, and still was in Marx’s day, applied less extensively to agriculture. But as agricultural technology improved, it would make the physical qualities of the earth seem less gifts of nature that cause local disturbances to the pure operations of capital (Marx 1967, 3:861) and more objects that bend to human technological mastery, that is, capital. Land’s scarcity and qualities would thus matter less as capital improvements continued (3:760, 765).4

There were also political reasons. A three-way contest/interaction is far more complex than a one-on-one showdown. Leaving land as an independent factor means leaving the landlords as an independent social base of power, making it far harder to view social tensions as a kind of O.K. Corral standoff between bourgeoisie and proletariat. Landlords, Marx wrote, were an “alien force” that owed its existence primarily to outdated feudal property rights that continued due to power, and only power.5 In fact, revenues from land are parasitic on the activities of parasites, that is, capitalists. While capitalists at least exercise rationality with energetic coldness in exploiting the workers, the value in land comes from leeching from the leeches, skimming the top off the “work” of capitalists, which is a form of work that for Marx barely deserves the name.

Philosophical reasons were important as well, even if they are less discussed in the political-economic histories of Marx’s ideas. Marx was after all a German philosopher, deeply influenced by Hegel. For metaphysical reasons, he needed communism to be a dialectical synthesis of opposites. A unity-out-of-opposites cannot be derived from three terms, however much one tries. There needs to be two polarities, one that is “everything,” one that is “nothing.”6

So land made its way out the door. What happens when land drops out of our core set of social science concepts? We are left with capital and labor. Once they are unmoored from the qualities of any specific location, both quickly become standardized, abstract, and placeless. Capital flows to wherever wages are lowest; labor moves to high wages. Labor itself becomes a homogeneous block, undifferentiated by local heritage, customs, and habits, whose productivity can be measured on a single standard based on “socially necessary labor time,” that is, however long it takes the average person to do a given type of work. This makes all work at all places comparable on a single unvarying scale. Capital too becomes standardized. A factory is a factory is a factory, generating a certain output wherever it is, independent of what and who surrounds it.

Now it is possible that Marx meant much of this to be taken ironically. A bitter joke exposing from within the human deformations caused by capitalism, which tricks us into seeing capital as able to master and render impotent nature, humanity, and culture. This is the forceful literary interpretation of Capital that Robert Paul Wolff (1998) puts forward in his Moneybags Should Be So Lucky.

Perhaps so, but many have yet to get the joke. Consider standard interpretations of the social effects of globalization or the Internet, like the “death of distance” or “the world is flat” or the “McDonaldization of the world.” The assumption is that since work can be done equally well from anywhere, it will flow to wherever it can be done most cheaply. Attachment by people and firms to a particular place is a kind of persistent, stubborn irrationality, which should eventually give way to more abstract and global standards that hold everywhere, equally.

This is not just the stuff of the New York Times punditry or prognostications from the early days of the Internet age. Harvard political theorist Michael Sandel has linked the flattening of the world to the Marxian picture of global capitalism. This universalizing tendency, he argues, threatens “the distinctive places and communities that give us our bearings, that locate us in the world” (Friedman 2005, 236; see box 4.4). Some economic historians (e.g., Gaffney 2006) have made similar points about the simplifying consequences of thinking in terms of a “two-factor” world.7

Back to the Land

There is another tradition besides the Marxian one, however, in which land continued to figure prominently, albeit in a transformed way. It is too rich and complex to detail here, but we highlight some central points. Two key figures are Alfred Marshall and Max Weber, whose ideas Talcott Parsons and Neil Smelser joined in a new theory of land in their Economy and Society.

Parsons was a giant in mid-twentieth-century sociology, even if his star has waned. One of his major preoccupations was to integrate economics and sociology into a general system that would preserve a distinct place for each. To this end, his first major work, The Structure of Social Action ([1937] 1967), joined the thought of two economists, Alfred Marshall and Vilfredo Pareto, with that of two sociologists, Max Weber and Émile Durkheim, neither of whom had been much read before that in North America. Parsons went on to translate and introduce to an American audience Weber’s classic, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

In 1956, with his student Neil Smelser, Parsons published Economy and Society, which returned to the links between general social theory and economic theory. The primary goal of the book was to situate the problems of economics—price, distribution, growth, and so forth—within a broader framework. This would highlight more distinctly the specific problems of the economist. And, perhaps more importantly, the aim was to provide a way to systematically investigate the many noneconomic factors that influence the economy “from the outside,” as it were, and which economies influences in turn—power politics, legal regulations, and, above all, cultural norms.

Writing at the end of his career, Parsons in his American Society (published posthumously in 2006) observed that the major “bombshell” of Economy and Society was its interpretation of the concept of land. Parsons and Smelser advanced this interpretation through close attention to the work of Marshall and Weber. The key similarity in Marshall and Weber is a deep sensitivity to the fateful economic consequences of what the classical economists called habits and custom. We would now call that culture. This idea is present but downplayed in Smith, Ricardo, and also Marx. Marshall and Weber give it pride of place.

That Weber would be a key source in drawing the connection between culture and land is no accident. Weber, a polymath of the first order, was first and foremost an expert in agrarian economics and legal history. Land and the historically and socially shifting meanings of property were always in his intellectual crosshairs.

While Weber’s main argument in The Protestant Ethic is one of the most famous in the history of modern social theory, its link to the concept of land is not immediately apparent, and much of the originality of Parsons and Smelser’s argument lies in making the connection. The key linkage lies in the fact that while both the Puritan commitment to work in a calling and the gifts of nature (like waterfalls and fertile soil) are not created for economic reasons (like wages or profits), they both generate tremendous economic consequences. How?

For the Calvinist, there are a fixed number of slots among God’s elect. Precisely who will occupy those slots is predestined. Being all-powerful and all-knowing, God already knows who is in and who is out. But to know if you yourself are among the elect? Being finite and mortal, you cannot. What can you do to earn a place? Nothing.

Calvinists thus found themselves in a terrific psychological predicament. Their solution was, in its own way, ingenious; it amounted to shifting the question of election into the subjunctive, so to speak. If you were among the saved, then surely your life would testify to your faith, wholly and completely, in all your thoughts, feelings, and actions, without any remainder. While there may be nothing you can do to force your way into heaven, you can look within yourself for signs that you already are one of the elect.

What followed was intense scrutiny of the self. One had to penetrate deep within, scouring the soul for any signs of evil, in the hopes of making oneself utterly transparent before God. It was in this context that diary keeping first emerged as an active practice of self-inspection.

But inwardness was not enough. Faith had to shine through in all your activities, including the most mundane, like the day-to-day tasks of earning a living. This radically transformed the nature of work, from a means to some other end (like survival or pleasure) to a vocation, worthwhile in itself. A member of the elect would not spend the bulk of his hours doing meaningless tasks; he would throw himself into his work with all his heart; he would be as scrupulous and trustworthy in business as at home; he would not covet profits for personal glorification and immediate enjoyment but would deny present pleasures by saving for the future.

In so doing, he would become a success in business, even while remaining true to Christian injunctions against conspicuous displays of wealth. While business success would put him in control over large sums of money, this in itself was not a problem. If God had a choice between two souls, one whose business had become successful through honest hard work, and another whose had failed from the opposite, whom would He have chosen? The question answers itself.

Economic success in this way becomes a sign—but not a cause—of election. And here is the connection to the concept of land. A waterfall was not made because of the profits to be had in electricity generation; it is a free gift of nature. Calvinists are similarly devoted to their work largely independent of economic considerations like wages and profit. Their commitment to work as a calling is a free gift, not of nature but of faith. All the same, it promises a bonus, a surplus, to anybody for whom they work.

From the perspective of a firm, therefore, places infused with Calvinist theology become very much analogous to good soil. If you had a choice of two locations to start a business, one animated by the idea that doing one’s job well is a task set by God, and another less animated in this way, which would you choose? Once again, the question answers itself.

Though Weber did not explicitly take the next step of not only connecting land to culture but also connecting culture to rent, Marshall did. He paved the way for breaking the classical identification of rent with the literal God- (or Nature-)given earth via ideas like “quasi-rent” and “rent of ability.” The key conceptual innovation was to treat rent as an analytical element present in all objects of value, rather than as strictly identical with the physical earth: “Even the rent of land is seen, not as a thing by itself, but as the leading species of a large genus” (Marshall 1892).

Building out from this insight, Marshall developed a far-reaching account of various types of rent. Quasi-rents come from various permanent human improvements to nature, such as better farmhouses, plumbing, irrigation, and the like. Though over the long term such improvements may be due to the profits they generate (this is why they are only “quasi” rents), in the short and middle terms, they are for all intents and purposes like good soil and air; they provide a bonus to all who work in their midst, and their owners can therefore charge a rent for access to this bounty.

Rent of ability is just as important. One of Marshall’s examples comes from theater. Actors may cultivate their theatrical talents for all sorts of reasons, perhaps only a small fraction of which have to do with the wages which they earn from those talents. But if for some reason demand for theater rises substantially—from, say, a general societal increase in education or affluence—actors will be able to reap the rewards of their gifts. There are now dozens of shows around town and only so many people with the ability to star in them! This is not different in any essential way from what happens when some new technological innovation renders the minerals buried in some plot of land suddenly valuable, and makes the owners of that land wealthy in the process.

While Marshall acknowledged that the “situation value” that some areas have comes sometimes from developing their surroundings with a view to profits—think of planned towns built expressly to make a profit on proximity to a factory or waterfront—the bulk of that value is what he called “public value.” This is locational value that comes not from any direct effort to acquire such value but rather from the public and quasi-public goods nearby. If the value of your home goes up $100 when a sushi restaurant opens around the corner, this is public value—the restaurateurs did not go into business to raise your home value, but through their actions they changed the character of your environment, which in turn would permit you to charge higher rent. Rent, in sum, is not “in” the land but rather is the economic benefit that accrues indirectly from goods or services not necessarily generated directly for economic ends. Rent rewards, we might say, the “effortless” component of our actions, that which we possess and are—hence the connection to property—without having to strive after it.

A similar sensitivity to locational dynamics fed into Marshall’s pioneering analyses of industrial districts. It is in this context that he made his famous statement that where complementary industries colocate there emerges “something in the air” that heightens the performance of all. Marshall has accordingly become a classic for economic geographers who study agglomeration effects. The foregoing discussion indicates, however, that these sorts of agglomeration effects are a special case of something broader and deeper, which goes beyond direct monetary benefits of concentration or a narrow conception of creativity as technical innovation: breathing the “air” of a distinctive place inspires a characteristic mode of existence and style of interaction, which imbues actions there with heightened meaning and importance. Such scenes, even the most traditional, are creative accomplishments that can draw people into the dramas they make possible and fill their surroundings with enhanced value.

Parsons and Smelser extended and joined all these ideas from Weber and Marshall by dividing the concept of land into three: physical facilities (earth, sun, soil), cultural facilities (e.g., “state of the art” knowledge and skills), and motivational commitment (like the Protestant ethic). These are all relatively insensitive, at least in the short term, to price; they are there regardless of what anybody is willing to pay for them. They vary considerably by location; some places have more or less of them. And they provide great advantages to firms and workers who locate near them.

On to the Scene

Think of the economic significance of scenes as an extension and specification of this Weber-Marshall-Parsons-Smelser tradition. The key idea again is intuitively simple. Places differ sharply in terms of the opportunities they afford to cultivate certain ranges of experiences. Such experiences include the kind of impassioned dedication to work characteristic of Weber’s Puritan.

But the range of possibilities is much greater now than in Weber’s day. There are places that encourage you to be glamorous, to express your uniqueness, to break normal standards of appearance, to connect to a tradition, to work hard, to be a good neighbor and community member, to shop and eat local, to kick back and relax, and more. We can recognize these intuitively when we walk or bike—or quantitatively stroll—from neighborhood to neighborhood. And all of these can come in different degrees and combinations. Hence the 15 dimensions of scenes and the many complexes of these we have introduced.

With these experiences, as with Weber’s Protestant ethic or Marshall’s public value, we need not presume that people primarily pursue them for the sake of their economic consequences (though of course they may do so). There is something attractive in itself in shining out on the dance floor, playing improvisationally in a jazz club, feeling rooted at home in a local pub, seeing oneself as connected with others in relations of mutual trust in a community center or neighborhood parish, and so on. But where certain of these experiences are strong (“in the air”) and easily available, certain types of firms clearly have better chances of succeeding—the economic value of a scene derives in no small measure, that is, from the experiences it creates. For scenes cultivate skills, create ambiances, and inculcate commitments that may be quite valuable to some types of work.

Six Hypotheses about How Scenes Improve Economic Performance

Take two video game design firms rather than two farmers, and call them Tech Firm #1 and Tech Firm #2. Tech Firm #1 locates in a scene that encourages personal self-expression, Tech Firm #2 in a scene that does not (as much). Tech Firm #1 is near the “state of the art” in new ideas, surrounded by an atmosphere that encourages innovation, not sticking with conventions. This is good soil for a firm that uses such abilities, commitments, and atmospheres, which it can “rent” when it hires somebody or when it literally rents an office on the scene. Its video games are better for it.

We could form similar hypotheses for other occupations, like artists. That artist clusters enhance, at least in more culturally oriented postindustrial economies, the performance of all sorts of work has been a keynote in several overlapping academic literatures. Economist Ann Markusen coined the term “the artistic dividend.” She highlights the prominence of artists in many contemporary workplaces, which increasingly require their services, such as graphic design, web design, product design, marketing, or advertising copy (Markusen, Schrock, and Cameron 2004). Similarly, sociologist Richard Lloyd (2006) argues that artist neighborhoods like Chicago’s Wicker Park play a key role in cultural production, gathering talent, stimulating new styles, sharing ideas. And one of Richard Florida’s (2002) central claims in The Rise of the Creative Class is that the “Bohemian” sensibilities traditionally associated with artists now enhance rather than undermine workplaces by inculcating habits of experimentation and imagination favored by the “creative economy” more broadly, beyond artists narrowly construed. Nonartist “creatives,” he argues, move near and learn from the denizens of Bohemian artist clusters, who themselves become less hostile to an economic order that now increasingly welcomes rather than represses them.

However powerful these links between artist clusters and broadly shared growth may be per se, they are likely enhanced by a supportive scene. Take two artists, Artist #1 and Artist #2. Each works, let us say, about the same number of hours per week and has more or less the same set of tools (computers, paints, software, etc.). Artist #1 is located in a thriving scene that encourages spontaneity (individual self-expression), putting on a stunningly refined show (glamour and formality), and standing out from the crowd (charisma). Artist #2 is located somewhere where these qualities are muted or even opposed. Artist #1 is working on fertile artistic ground: in that scene, there is, we might imagine, an openness to improvisation and risk, an understanding that many ideas don’t pan out, opportunities for idea and technique sharing, encouragement to rise to the occasion and produce something grand, a willingness to cast off conventional stereotypes and return to primal, unvarnished experiences, and much more. This is a scene, we might hypothesize, encouraging and hospitable to high quality artistic work, not to mention the attendant “dividends” it may provide for others.

In both cases, the tech firm or artist on more fertile soil will generate significant economic returns. By contrast, tech firms or artists on soil not conducive to their work would not, or at any rate would do so to a lesser extent. But in this case “soil” is not dirt but life in the scene.

In these examples, we are hypothesizing that within different scenic contexts, the economic impacts of other variables should change. Here are three specific empirical generalizations that follow (three more come below): (1) When located in scenes that more strongly support self-expression, firms producing innovative products, like advanced technology, should be associated with economic growth; when located in scenes that oppose self-expression, their association with economic growth should be weaker. (2) General economic growth, as well as growth in the broader creative class, should be stronger when artists are located in more self-expressive, glamorous, and charismatic scenes, but weaker when they are located in scenes that run counter to these dimensions. (3) Not only rent but many types of economic growth indicators should rise more in these (self-expressive, glamorous) scenes.

The Economic Impacts of Scenes Are Altered by Their Surroundings

We could just as well theorize not only about how scenes alter the economic effects of other variables but also about how the economic impacts of scenes change depending on their surroundings, as Marshall’s ideas about “situation value” would imply. Consider Bohemia as an illustration of these situational shifts. Bohemia is a useful concept in this connection because of its strong historical linkage to concrete places. Think of the Latin Quarter, Greenwich Village, Haight-Ashbury, or, more recently, Parkdale in Toronto or Pilsen in Chicago. These are all specific neighborhoods, which invite those who enter to think of themselves as a struggling but elite cadre of nonconformists, thinking thoughts, feeling feelings, experiencing experiences that would be out of bounds for “regular” people.

Yet classical Bohemias are not isolated neighborhoods. They have often been at their peaks at specific moments in the histories of their surrounding cities. In fact, the wider metro areas of which Bohemias are a part have in many cases not been very Bohemian. The Latin Quarter in the 1840s stood out because the rest of Paris provided fewer opportunities for concentrated and public experiences of self-expression. Paris Bohemia was at its strongest when Louis-Philipe was at his most repressive. Wicker Park in the 1990s existed within a Chicago that until very recently was dominated by the social life that took place in ethnic churches and supported the political machine. Toronto’s first Bohemian stirrings came in the Yorkville neighborhood in the late 1960s and early 1970s, stamped by the moralistic environment of “Toronto the Good” in which, as Ernest Hemingway described it, “85% of the inmates attend a Protestant Church on Sunday” (Lemon 1985, 57).

Spatial boundaries, that is, intensify symbolic boundaries. To set foot inside a Bohemian quarter and to feel at home is to mark yourself off against the squares over there in their cubicles. By contrast, if an entire metro area were “Bohemian,” then this boundary work would be much harder. If your mother enjoys punk music and alternative theater, your boss plays in a psychedelic band, and your neighbors all smoke marijuana, there is less to rebel against. Bohemia becomes Neo-Bohemia, ordinary, not a beacon for the misfits of the world.

Local authenticity is another key dimension of a scene that stresses sensitivity to the surrounding local context. Indeed, the very attraction of “the local” is that one expects to find something here that you can get only here, something distinctive, not (yet?) homogenized by the standardizing forces of global capitalism. Thus sociologist Sharon Zukin has linked local authenticity to neighborhood growth by specifically highlighting the case of New York’s Lower East Side. Local charm attracts persons dissatisfied by an increasingly McDonaldized and uniform world culture, and spurs demand for local products and services from fruit and vegetable stands to independent record stores to the local cafe.

In what situations would the allures of local authenticity be especially strong? Consider two possibilities. A first has to do with what the people in the scene spend their time doing. Specifically, do they walk or drive? Why should this matter? Walking sensitizes people to their environments; it slows the pace of life. On a walk, you can relatively easily greet and patronize the local grocer, wave to or stop for a drink with the cafe regulars, and stroll through the neighborhood flea market. All this is hard to do at 60 mph. That is, local authenticity may become more attractive as an alternative to globalized high-speed modernity when coupled with the more relaxed pace implied by walking. A hypothesis results: growth should be stronger, especially among firms which are local themselves, in locally authentic scenes where there are more rather than fewer people who regularly walk.

A second possibility has to do with the surrounding natural environment. Nature is important to consider in this context because while “land” is more than “the physical qualities of nature,” it still includes nature. Indeed, as Harvard economist Edward Glaeser writes in The Triumph of the City, “Americans do seem to love warm weather. Over the last century, no variable has been a better predictor of urban growth than temperate winters” (2012, Kindle locations 1149–50). But not every city has nice weather and easy access to abundant and beautiful natural amenities. What can these places do other than throw up their hands in despair?

Jim Brainard, mayor of Carmel, Indiana, proposes a hypothesis: “We don’t have the Pacific Ocean, we don’t have the Rocky Mountains. So we have to work harder on our cultural amenities and in our built environment to make it beautiful—and to make it a place where people want to choose, to spend their lives, raise their families, and retire” (2009). That is, perhaps local authenticity can “compensate” when a place lacks those natural endowments that “automatically” bless it with beauty and connect it to ample recreational activities. Such communities may have added incentive to build a sense of local authenticity and broadcast their charms more intensely to recruit and retain skilled residents. If this is so, in places with fewer natural amenities, local authenticity could be a bigger selling point, especially for highly educated persons looking to escape the cosmopolitan rat race and settle down in a charming locale. That is, local authenticity might substitute for nature in less naturally well-endowed settings.

So now we have three more propositions: (4) Bohemian neighborhoods should correlate with population change and other indicators of economic growth when they are located inside less Bohemian cities; in less traditionalistic surroundings the “Bohemian” dividend should be weaker. (5) Local authenticity should be associated with growth in more-walkable places and (6) in places with fewer natural amenities.

Scenes Are Growth Factors

The performance score measures of scenes permit us to transform these ideas about scenes as economic growth factors from interesting daydreams into empirically testable propositions. To do so, we join our scenes variables with other variables, mostly from census data. The general approach is the standard one in social science. One looks for covariations and asks questions like, Where there are scenes that more strongly prize personal self-expression, is there also population growth, job growth, income growth, human capital growth, rental increases, greater innovation, and so on?

Of course, putting the question this way immediately raises the issue of spuriousness. Perhaps the correlation we observe is not due to the scene but to some other factor. Maybe self-expressive scenes are almost always located in high-population zones, and maybe high-population zones have economic growth wherever they are, and without the fact that they happen to be where numerous people are, self-expressive scenes would not be connected with growth.

To guard against spuriousness of this sort, we include a battery of control variables in our analyses. Which ones? The best candidates would permit us to rule out the possibility that any correlations we observe between scenes and economic growth are due to some other factor. The likeliest suspects are staples of the local development literature that have been featured in past studies by experts on related issues: population, cost of living, education, race, politics, and crime. We therefore control for these in all our US analyses, and detail the similar variables for Canada, below. Chapter 8 describes variables and methods of analysis in more detail.

In addition, we control for two other key variables. First is the local concentration of cultural industry employment, to test whether any correlation between scenes and growth is in fact due not so much to the overall aesthetic of the place but to the fact that this specific group is present.8 Second, we also include as a control variable the most common combination of scenes dimensions, which we featured in chapter 3—Gemeinschaft versus Gesellschaft, Communitarianism versus Urbanity. Because this complex so sharply defines the scenic differences across the country, we want to be sure that when we see a connection, say, between self-expression and growth that this more specific observation is not simply a function of the more general dynamic of Communitarianism versus Urbanity.

We call these eight variables the Core, which are listed in the note to figure 4.1. The Core is included as independent variables in all our multivariate analyses in this chapter, to provide a consistent benchmark for assessing results. We often add other variables, however, in other chapters when these are relevant to the specific hypotheses we are testing.

Figure 4.1

This figure shows how the impact of technology clusters on economic growth varies depending on the self-expressiveness of the scene. It represents the interaction of self-expression and technology clusters. The graphics are read left to right, where the x-axis indicates higher or lower self-expression performance scores (relative to the national average), and the y-axis indicates the predicted change in six separate outcomes (again relative to the national average): change in total jobs, change in income, change in total population, change in rent, change in the college graduate share of the population, and change in the postgraduate share in the population. Change measures are from 1990 to 2000, except for change in jobs, which is from 1994 to 2001 (due to data availability). Change in jobs, income, rent, and population are measured as ratios (e.g., 2000 per capita income / 1990 per capita income); change in the college and postgraduate shares of the population are measured as differences in proportions (e.g., 2000 college graduate percentage of the population − 1990 college graduate percentage of the population). Predicted values are based on multilevel models with counties as the level 2 units of analysis and zip codes as the level 1 units of analysis. Covariates include technology industry concentration, (BIZZIP) self-expression performance score, their interaction term, and the Core (county population, rent, party voting, and crime rate; zip code percentage college graduates; percentage nonwhite; cultural employment concentration; and our factor score measure of Communitarianism/Urbanity). All variables have been standardized to have mean equal 0 and standard deviation equal 1. Unless otherwise noted, all interactions are statistically significant (p < 0.05). N is all US zip codes. More on variables and methods of analysis is in chapter 8 and the online appendix (press.uchicago.edu/sites/scenescapes).

Any connection between a type of scene and economic growth we report is thus net of the Core. That is, the below results show whether, regardless of education levels, population levels, cost of living, and so on, zip codes with more self-expressiveness, or local authenticity, or glamorousness, and so forth, have more economic growth.

How do we measure economic growth? The main dependent variables, or outcomes, include the classics: growth in population, income, rents, and jobs. To these we add three variables featured in recent literature on the postindustrial creative economy: patents, the standard proxy for how innovative a local economy is; and gains in college graduates and postgraduates, the typical measures of the human capital that leads to idea generation. All nine outcomes are listed across the bottom of figure 4.3. Unless otherwise noted, the changes we measure are from 1990 to 2000.

Besides the Core controls above, we considered dozens of others—from technology industry clusters to January temperatures to county-wide attitudes toward women in the workplace—to assess their impacts.9

Do Scene Differences Make a Difference?

Chapter 3 showed how our scenes measures identify strong differences in the cultural character of places. That chapter ended with a challenge from William James: Do these differences make a difference? Now we can be more specific: Are they merely spurious icing or can they drive economic and social processes, as the discussion of the scene as a factor of production suggests? Consider our hypotheses from above.

A Self-Expressive Scene Enhances the Impact of Technology Clusters on the Local Economy

For this first proposition, about how self-expressive scenes provide fertile soil for technology work, we turn to our US data. Our question is whether the impact of technology clusters on various measures of economic development shifts as the scene in which they are located becomes more or less self-expressive. Figure 4.1 shows that these contextual dynamics do indeed often occur.

To read this type of figure, compare the x-axis, the y-axis, and the three lines. In figure 4.1, the x-axes show variation in self-expressive scenes: average self-expression is 0, and then values along the axis are standard deviations above or below that average. The y-axes are the economic development outcomes we are examining here: change in jobs, income, population, rent, college graduates, and postgraduates. National averages are again scored 0, and units are standard deviations away from that value. Thus for job growth (as an example), positive values indicate higher than average growth, and negative values indicate lower than average growth. The three lines show average technology industry concentration, high technology industry concentration (90th percentile), and low technology industry concentration (10th percentile).

For the type of proposition investigated in figure 4.1, the key is to follow the three lines while reading from left to right across a given x-axis. The patterns are striking. Start with the upper left graphic, where change in total jobs is the outcome. At the far left, the three lines barely differ: in less self-expressive scenes, high versus low technology industry concentration makes little difference for job growth. As we follow the lines to the right, they separate: in the country’s most self-expressive scenes, greater technology industry concentrations are more strongly associated with faster job growth.

Self-expression also shifts the impacts of tech concentration on change in income, rent, college graduates, and postgraduates. Look again at the far left side of the graphics for each of these outcomes. The dotted lines (indicating high tech industry concentration) are all lower than the dashed lines (indicating low tech industry concentration): in less self-expressive scenes, growth in rent, income, college graduates, and postgraduates was relatively weaker where tech concentrations were stronger. Then we follow the lines to the right; they cross: in more self-expressive scenes, greater technology industry concentration is associated with stronger growth in these outcomes. The impact of tech concentration on population change, by contrast, does not seem to be affected by self-expression: the lines stay close together all the way across, and do not separate to a statistically significant degree.10 Still, on the whole, self-expressive scenes seem to be fertile economic soil indeed.11

This idea of exploring how technology links with nontech factors extends cutting-edge work in economic geography. UC Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti’s The New Geography of Jobs, for instance, shows that innovation especially in the technology sector drives the “new economy,” but also that technology clusters are the main source of more and better jobs beyond that sector. A personal trainer in Silicon Valley is better off than one living three hours away, in Visalia, he shows.

These results about how scenes heighten the connection between technology clusters and economic development suggest that tech clusters on their own are not the whole story. Rather, innovative industries come into their own and perform at higher levels when coupled with the right scene: consumption does not only follow along in the wake of production; consumption can enhance and improve production. While evidence for this connection has typically come from anecdotes from the bars of Silicon Valley, San Francisco, and New York, figure 4.1 shows that these are not unique cases but emblematic of a broader and deeper connection.

A Strong Renoir’s Loge Scene Enhances the Artistic Dividend

Our second proposition suggests that when artists are concentrated in welcoming scenes, the artistic dividend increases. We test this hypothesis with our Canadian data, focusing on a scene measure that approximates the scene embodied in Renoir’s Loge, which we outlined in chapter 2. Combining glamour, charisma, self-expression, and formality, this measure is based on a factor analysis of scenes dimensions constructed from Canadian census of business data.12 It is strongly correlated with theaters and other items listed in box 4.15 on key Renoir’s Loge amenities. And it is highly concentrated in Canada’s urban centers, with all the 29 highest-scoring FSAs located in Toronto or Montreal (Toronto’s highest-scoring FSA, M5V, contains the entertainment district; Montreal’s, H2W, is the center of the Plateau Mont-Royal district and contains the highest percentage of artists of any Canadian FSA).

We again examine changes in several indictors of overall local economic development, in this case from 1996 to 2006: median family income, average employment income, and so on. We also include in our analysis a battery of controls similar to the US Core group. All variables are listed in the figure 4.2 note.13

Figure 4.2

This figure shows how the impact of the arts and culture share of the workforce on Canadian local economic development varies across Renoir’s Loge scenes, measured as a factor score featuring glamour, charisma, self-expression, formality, anti-utilitarianism, and anticorporateness (relative to the national average). It represents the interaction of art and culture professionals with Renoir’s Loge. The graphics are read left to right, where the x-axis indicates stronger or weaker Renoir’s Loge scenes, and the y-axis indicates the predicted change in six separate outcomes (also relative to the national average): change in employment income, median family income, rent, population, the university graduate share of the population, and the “creative class” share of the workforce. Change measures are from 1996 to 2006. Changes in income, rent, and population are measured as ratios (e.g., 2006 employment income / 1996 employment income); changes in university graduates and the creative class are measured as differences in proportions (e.g., 2006 university percentage of the population − 1996 college graduate percentage of the population). Predicted values are based on multilevel models with census metropolitan areas (CMAs) as the level 2 units of analysis and Forward Sortation Areas (FSAs) as the level 1 units of analysis. Covariates include the proportion of the workforce employed as “professionals in art and culture,” Renoir’s Loge scenes, and their interaction, along with 1996 population, rent, and university graduate and visible minority shares of the population, as well as 2000 Liberal Party vote share. All variables have been standardized to have mean equal 0 and standard deviation equal 1. Unless otherwise noted, all interactions are statistically significant (p < 0.05). N is all Canadian FSAs.

Figure 4.2 examines whether correlations between indicators of economic growth and the share of the local workforce employed as professionals in arts and culture shift as the scene more or less strongly approximates Renoir’s Loge. What do we find?

The pattern in figure 4.2 is again striking. Start at the upper left, with changes in employment income (i.e., wages) and median family income (a broader-based indicator of income growth). Both show a similar pattern: arts and culture workers are in general associated with income growth, but the association is strongest when artists live in a Renoir’s Loge scene. On the far left end of the x-axes, the lines touch: in places with weak Renoir’s Loge scenes, having high concentrations of arts and culture professionals does not lead to much more income growth than having a low concentration. But follow the lines to the right as they separate: where Renoir’s Loge is strong, a high arts and culture share of the workforce meant faster income growth than in areas with relatively few artists.

Change in rent shows a more dramatic shift across scenes, not only a change in degree but a reversal. On the left side, the line for few arts and culture workers is on top: where Renoir’s Loge was weak, rents increased more where there were few artists compared to where there were many. However, follow the lines to the right into areas with stronger Renoir’s Loge scenes; they cross. Here, places with strong artist concentrations had bigger increases in rent than places with low concentrations. Change in population has a somewhat similar pattern: where Renoir’s Loge was weak, population growth was much higher in places with few artists. As we move to the right, however, where population growth in general was slower, the lines come together, and artist concentrations are not a (relative) drag on growth.

Now look at changes in university graduates and the creative class. The impact of artist concentrations on university graduates is similar to their impact on income: it steadily increases as the scene becomes stronger. The effect of artists on creative-class growth, however, reverses as the scene changes. In less glamorous, charismatic, and self-expressive scenes, artist clusters had relatively low growth in the creative class; when joined with a scene that supports self-expression, glamour, and charisma, artists attracted the creative class. The creative class, in other words, does not seem to be as strongly drawn to artist communities without the right amenities. Instead, they grow where artists and amenities join to make a more compelling overall scene.

Overall, in line with the ideas of Richard Florida and Ann Markusen, we thus find strong links between artists and overall economic development. But these connections are often strongest when artists live amid the Renoir’s Loge combination of glamour, charisma, and self-expression. Outside of this context, relationships between artists and economic growth are often weaker. These results suggest that the artistic dividend does seem to be enhanced when artists are surrounded by a supportive scene.

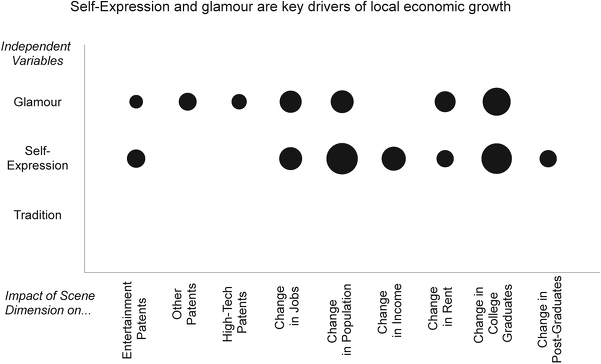

Self-Expression and Glamour: Two Core Drivers of General Economic Growth

These are strong indications that especially those scenes that prize glamour and self-expression provide noneconomic bases for economic success. We would therefore expect to find that they are linked not only with rising rent but all manner of economic development. And that is what we do find, at least in the United States, as in figure 4.3.

This figure shows the impacts of three (BIZZIP) performance scores—self-expression, glamour, and tradition—on nine economic development outcomes (listed across the bottom). It summarizes three separate analyses. In each, the full model includes the Core (see note to figure 4.1) plus one of the performance scores. Black circles indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) positive associations, hollow circles indicate statistically significant negative associations, and blanks indicate that there is no statistically significant association. Circle sizes are proportional to the magnitudes of coefficients from multilevel models, where counties are the level 2 units of analysis and zip codes are level 1. All variables have been standardized to have mean equal 0 and standard deviation equal 1. Because patents are county-level variables, they are analyzed with ordinary least squares (OLS) models, and circle sizes are proportional to standardized coefficients. N is all US zip codes.

To read this type of figure, the key is to look at the black and white shading and sizes of the circles. A bigger circle means a stronger relationship (e.g., between self-expression and change in jobs). A black circle indicates a positive relationship (more self-expressive scenes, greater job growth); a hollow circle indicates a negative relationship (figure 4.3 has no hollow circles, but figures in later chapters do). If a circle is present, the relationship is statistically significant (i.e., not random), even adjusting for the controls we discussed above (the Core). If there is no circle, the relationship is not statistically significant, as is the case for traditional scenes and all outcomes.

What stands out is how broad and deep the link is between self-expression, glamour, and growth. Rent climbs at relatively high rates in places with scenes strong in both dimensions. But not just rent. Glamour and self-expression are significant drivers of seven of our nine outcomes (listed at the base of figure 4.3)—of the more than 20 variables we examined, they had the broadest positive impacts on numerous economic growth indicators. Glamour and self-expression were in fact more consistently important than such urban development staples as growth and level of human capital, arts jobs, technology jobs, population density, and commute times.

And glamour and self-expression were not only broadly linked with key outcomes; they were sometimes strongly linked. For instance, no other variable in our Core group shows as strong a link with population growth as does self-expression. And only the median county rent and the concentration of artists are more strongly linked with college graduate gains than are glamour and self-expression. In other words, if you wanted to predict which places would enjoy the most robust economic development through the 1990s,14 not only college graduates or tech but the degree to which the local scene prizes an improvisational attitude toward life and a glamorous way of displaying the self is one of your best bets.

Traditional scenes, by contrast, were not linked with economic outcomes either way, positive or negative. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that the more communitarian dimensions of local scenes have no role to play in economic development, and that young, flexible creatives are the only game in town. College graduates and some other economic growth indicators are rising where the scene evinces more local authenticity; rent is rising in more neighborly scenes. And both neighborliness and local authenticity are linked with patents (not shown).

This last finding about patents goes so much against the grain of much of the urban development literature that tends to focus on the more urbane and experimentalist dimensions of innovation that we did not believe it ourselves at first, and ran many tests to verify whether it was just statistical noise. It does not seem to be. Rather, our conclusion is that most analysts miss the connection because neighborly scenes, local scenes, and patents all tend to be in high rent districts (like Silicon Valley), and they mistake rent for the main event. But once one controls for rent, the link between neighborliness and patents is robust.

Innovation, that is to say, has many dimensions other than rule breaking or show stopping. It is often emotionally taxing, marked more by failure than by success. Being rooted in a warm, stable, supportive, and trusting environment could encourage perseverance through difficulties. And some of the best new knowledge can be like the best food: it comes slow, not fast, organically connected with local practice, rooted in the particular dynamics of a concrete place and community.

Bohemian Islands in Communitarian Seas Lead to Growth, but Not Elsewhere

And what about Bohemia? The suggestion above was that the allure of Bohemia should be linked to the character of its surroundings. To test this idea, we construct a bliss point measure, based on the scene profile of all US zip codes against the ideal-typical Bohemian profile from chapter 2. Zip codes closer to that ideal type are defined in this way as more Bohemian. This measure of Bohemia is strongest in high crime areas where many artists live but relatively few college graduates, tech workers, or R&D workers are nearby. Moreover, it tends to be in places where, according to the DDB lifestyle survey, the typical person, when asked whether he considers himself to “be a hard worker,” is somewhat likely to say “no”—that is, where the bourgeois, nose-to-the-grindstone work ethic, is relatively weak.15

Our analysis examines how the impact of a variable (in this case Bohemia) on indicators of economic growth varies across contexts. The context here is the county average score on our first US scenes factor, Communitarianism/Urbanity. This gives a measure of the general county scene, running from more communitarian counties (on the left end of the x-axis), which are more traditional, neighborly, and formal, up to less communitarian counties (on the right end of the x-axis), which are more rational, corporate, utilitarian, transgressive, and glamorous. The idea, again, is to examine whether the economic impacts of Bohemia shift as their surrounding scenes become more or less communitarian.

Figure 4.4 suggests that the economic impacts of Bohemian zip codes are in some cases stronger when they contrast their surroundings, that is, when located in a more communitarian surrounding county. More Bohemian amenities predict increases in income and population when in more communitarian counties; as the county becomes less communitarian and more urbane, more versus less Bohemianism makes a smaller difference for income and population growth—in fact, for income growth, the relationship reverses in the least communitarian counties (at the far right), and less Bohemian zip codes had higher income growth than more Bohemian ones. Similarly, in the less communitarian (more urbane) counties, more Bohemian places had fewer high-tech and entertainment patents than less Bohemian places, and in the case of entertainment patents the relationship reverses in more communitarian counties. Yet the positive relationship between Bohemias and job growth does not shift across county Communitarianism: the distances between the three lines do not change in a statistically significant way as they move across the x-axis.16

Figure 4.4

This figure shows how the impact of Bohemia on economic development varies depending on how communitarian or urbane the surrounding scene is. It represents the interaction of the (zip code) Bohemia bliss point with county average Urbanity. The graphics are read left to right, where the x-axis indicates Communitarinism/Urbanity, and the y-axis indicates the predicted change in six separate outcomes: entertainment patents, high-tech patents, change in population, change in income, change in total jobs, and change in the postgraduate share of the population. Except for the patents, predicted values are based on multilevel models with counties as the level 2 units of analysis and zip codes as the level 1 units of analysis. Because patents are county-level variables, they are analyzed in ordinary least squares (OLS) models. Covariates include the Core (see note to figure 4.1). To the Core, we add our (BIZZIP) bliss point measure of Bohemia (defined in the online appendix), the county average Urbanity, and their interaction term. We measure Communitarianism/Urbanity with a factor score that combines multiple scenes dimensions: higher Urbanity means more glamour, transgression, corporateness, rationalism, and utilitarianism; lower Urbanity means more neighborliness, tradition, and formality. All variables have been standardized to have mean equal 0 and standard deviation equal 1. Unless otherwise noted, all interactions are statistically significant (p < 0.05). N is all US zip codes.

These figure 4.4 results provide qualified support for our proposition about Bohemian islands within communitarian seas being conducive to growth.17 More generally it underscores the importance of considering contextual scene characteristics, which qualify the common reasoning that “to be creative, we need more Bohemian folks.” These scene results suggest that, on the contrary, Bohemias can add value (as measured in economic development terms) if they are surrounded by more communal, even anti-Bohemian people and institutions.

Conversely, if an area already has a generally less traditionalist ethos, adding more Bohemian people or facilities or programs (if we are pondering local policy options) may have small economic impact. When Bohemia is not anymore an island in a communitarian sea, that is, but just one style in a more diverse (urbane) context, the intensity of its countercultural resistance to its surroundings is weaker, and its economic effects less distinct. The contrast between establishment and radical is reduced, and specifically, Bohemian neighborhoods stand out less both as innovation centers and talent attractors. One indication of this moderating of Bohemia in less communitarian contexts is that postgraduate degree holders—harbingers of the establishment18—actually increase in Bohemias located within the least communitarian parts of the country, as figure 4.4 also shows.19

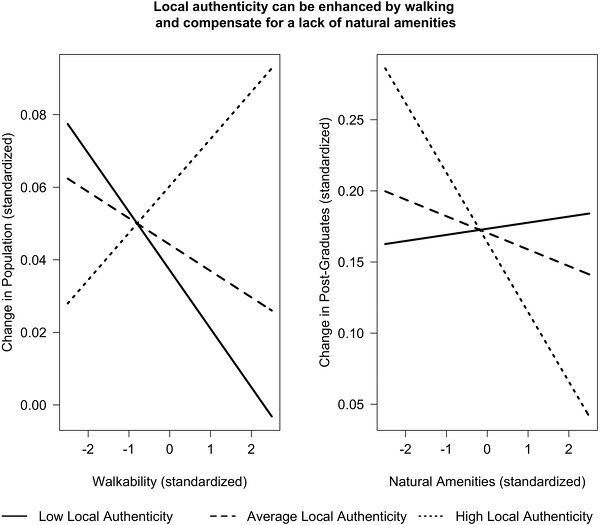

Local Authenticity Can Sometimes Be Enhanced by Walking and Compensate for a Lack of Natural Amenities

Finally, let us test the ideas about local authenticity: that the charm of the local scene can be heightened by routinely walking through it and might compensate for a lack of natural amenities. To do so, we look (in figure 4.5) at how the impacts of local authenticity may vary across contexts of walkability and access to natural amenities.20

Figure 4.5

This figure shows how the impact of (BIZZIP) local authenticity on population and postgraduate growth varies across walkable and natural amenity contexts. It represents (on the left) the interaction of local authenticity and walkability and (on the right) the interaction of local authenticity and natural amenities. The graphics are read left to right, where the x-axis indicates walkability (on the left) and natural amenities (on the right), and the y-axis indicates the predicted change in two outcomes: change in population and change in the postgraduate share of the population. Predicted values are based on multilevel models with counties as the level 2 units of analysis and zip codes as the level 1 units of analysis. Covariates include the Core (see note to figure 4.1). To these we add for the left graphic local authenticity, walkability, and their interaction term; for the right, local authenticity, natural amenities, and their interaction term. All variables have been standardized to have mean equal 0 and standard deviation equal 1. Unless otherwise noted, all interactions are statistically significant (p < 0.05). N is all US zip codes.

Figure 4.5 suggests that for some outcomes the context makes a difference for the growth potential associated with local authenticity. Look first at the left graphic. As we follow the lines of local authenticity to the right, walkability increases, and the lines cross and spread out: where more people walk to work, the impact of local authenticity on population growth is strongest. This result gives some qualified support to the proposition that when people slow down to engage with a strong local culture, that culture may become more attractive, a simple idea illustrating potential scene-specific impacts on growth.

Now look at the right graphic. If we follow the lines from right to left, we move from places with more to less natural amenities. As we do so, we see that places with few natural amenities and higher local authenticity are associated with relative increases in the postgraduate share of the population.21 This pattern seems to resonate with Mayor Brainard’s intuition. While natural amenities certainly can be key factors in driving growth, other amenities (often constructed, like festivals or gardens or B&Bs or libraries) can, at least for some persons (e.g., postgraduates), compensate for having low or average access to natural amenities. This is a far more encouraging result about the potential of local policy makers to build an attractive scene than what many accounts offer, which often imply nothing can be done. Richard Longworth’s (2008) account of Midwest cities and towns, Caught in the Middle, for instance, shows that a few places like Chicago and Kalamazoo have made strides toward creating new scenes to adapt to the decline of the rustbelt manufacturing economy, but many other locations are just quietly declining.

It is not easy to create attractive local authenticity, but these results are more sanguine than Longworth’s picture. There are many examples of success as well as failure. Still, our analysis provides an intriguing glimpse at this counterintuitive Brainard effect, while showing that Brainard may speak for many others, who, by being sensitive to their local context, can make a real difference. “If you have lemons, make lemonade”—a policy motto to which we return in chapter 7, which reflects on general implications of scenes for local policy.

Conclusion—“Every Man a Musician”: Throwing Open the Garret Gates

The general message of these results comes out loud and clear: The cultural character of a place is a strong determinant of its economic fortunes.

We conclude this discussion of economic impacts of scenes by reflecting on what the results imply on a broader level, returning to the higher plane of the discussion of land, labor, and capital. Max Weber again provides a useful point of departure. He was fond of using the phrase “every man a monk” to characterize the world-historical—especially economic—implications of the Protestant Reformation.

By this, he meant that the Reformation threw open the walls of the monastery, injected its ascetic element into everyday life, and offered positive religious backing for the focused, disciplined, and rational exercise of mundane activities like work and household management. Normative ideals formerly restricted to religious virtuosi were extended to a wider population, tremendously expanding and deepening the personal religious commitments and experiences available to them. Heightened expectations of disciplined performance as an everyday occurrence, outside of specialized settings, generated new anxieties and conflicts.

And, most fatefully, the productivity gains that followed created what philosopher Charles Taylor calls a “disciplinary revolution” (Taylor 2007, ch. 12). The rest of the world became encased in the “steel shell” of capitalism, as Weber famously described it. If Calvinists pursued work with the ascetic zeal of a religious calling, others for whom worldly toil was a burden were thereby forced to work harder or move aside.

Things have changed since Weber’s times. Not “every man a monk” but “every man a musician” could describe the situation in general, if not perfectly accurate, terms. The walls of the lab, lecture hall, and Latin Quarter have been thrown open, injecting expressive and creative elements into everyday life. Practices and sensibilities formerly restricted to creative virtuosi have been extended from the garret, studio, and study to boardrooms, city halls, office cubicles, and main streets.

This marks a great upgrading of the expressive and creative possibilities available to the general populace. It also subjects more individuals to previously more exclusive anxieties oriented around the quest for authenticity and the demand to construct meaning for oneself. And as politics has grown ever more populist, ratcheted up still further after 1968, the literal meaning of “everyman” has shifted from the politically active of past centuries to include more men and women than ever. This is clearest in the Western democracies, of course, and large parts of the world remain important exceptions.

We are witnessing in many geographic areas the institutionalization and internalization of creativity. Like the Protestant ethic, it has transformed the economic playing field. Places that best facilitate idea and style generation are succeeding, even if success is not due to any single factor, whether it is education, basic research, technology, artists, tolerance, or the scene. In any case, this is a world that Weber would have hardly recognized.

Has it thrown up an iron cage of creativity? Innovate or die? Bohemia or bust? There is no one, clear answer in these analyses. We do find that many places encouraging residents to express and glamorously display themselves are at the leading edge of the creative economy, yet they do not have a monopoly on innovation or growth. Other places with neighborly scenes also grow and innovate. Some places that root residents in the local or keep them in contact with nature are growing, innovating, and attracting people with education and skills. Nashville’s country music industry rivals music industries in New York and Los Angeles. Yet each city’s musical genres feed on the strikingly different amenities and scenes: three of the five most abundant types of amenities in Los Angeles are jewelers, bakeries, and commercial artists; in New York the top categories include jewelers, delicatessens, and art dealers. The most numerous amenities in Nashville are automobile customizing services, Methodist churches, and the Church of Christ.

These distinctive patterns tell a powerful story about local cultural soils fostering different scenes with different economic consequences, a quite different story than one which omits land. Of course, scenes have other consequences beyond economic growth. They are not only land for working; they are also habitats for living. Chapter 5 thus turns to the links between scenes and the composition of residential communities.