7

Making a Scene

How to Integrate the Scenescape into Public Policy Thinking

The primary concerns of this book have been descriptive and analytical: What are scenes, how can we measure them, where are different types of scenes, and what are their consequences? Policy implications have emerged here and there, but people whose primary interest is in public policy will likely want to know more: What can I do with these ideas for my community? This chapter offers some general advice for integrating ideas about the scenescape into public policy thinking.

These policy issues are not idle questions for us. We have actively participated in the policy process, in particular in Chicago and Toronto. These experiences inform much of the discussion throughout this chapter.

The focus of the chapter, however, is less on specific policy suggestions and more on outlining how to use scenes ideas, concepts, and data in policy making in ways that others can adapt to their own circumstances. That scenes are generally important for urban policy is not news to most policy makers—far from it. In fact, many mayors and city officials have been decades ahead of academics in recognizing how significant scenes, or more broadly the character and feel of their cities and neighborhoods, can be for the fortunes of their communities. And they know how important policy decisions, about zoning or housing or business licensing or noise or grants, can be for preserving, enhancing, or changing that character.

The approach developed in this book helps further advance understanding of the policy implications of scenes in two ways: first, to articulate a way to think about the general importance of scenes, in the context of some of the major challenges policy makers face today, as one key issue area among others; second, to show how local “character” can be measured, quantified, and eventually translated into specific policy goals. The scenescape thereby moves out of the realm of ineffable “quality of life” and stands alongside the major concerns that have long dominated policy discussions, like education, income, density, and population changes.

This is a novel and useful contribution to urban policy. Planning departments and policy consultants, if they so choose, can incorporate scenes measures into their cost-benefit or other analyses along with jobs and income. Ask for these if you are making policy. Most of our data are available down to the zip code level and are publically available to download if others wish to use them, even if tapping other sources may be useful as well.

We begin by detailing critical changes in the past few decades that have shifted the foundations of urban policy, giving cultural issues in general and scenes in particular heightened policy salience. Some discussion draws on earlier chapters, but here we stress relevance for policy makers. Crucial is the idea that even if different cities and communities operate in a similar general context, they must make decisions based on their own specific histories and needs. There is no one right answer, and what works in San Francisco might not work in Indianapolis. It is thus crucial for any city or community to compare itself to others (or subsets of others) along many dimensions and to evaluate the implications of adopting one course of action over another, while at the same time undertaking more focused study of one’s own locality.

Based on these general ideas, some practical advice follows about how to include scenes-style thinking in formulating urban policy, both nationally and locally. Next come some examples of results that can follow from different policies, highlighting the connections between self-expressive scenes, density, and college graduates. The chapter concludes with lessons from Toronto, where certain scene-related concepts have been integrated into official cultural, economic development, and land-use policy making.

New Challenges for Urban Policy

Many basic challenges of urban policy have critically shifted in the past three to four decades. Globalization, individualization, gentrification, postindustrialization—under one label or another, these processes are staples of many general accounts of urban development. What is new here is explicitly joining them and drawing out their implications for policy makers. The most general result of these changes from our point of view is that urban policy cannot avoid serious consideration of scenes—how to identify, expand, diversify, focus, and protect them so as to energize civic identity; grow, retain, and attract talent; draw visitors; and build strong neighborhoods. A few words follow on each change process and how it links to scenes analysis.

Globalization. While analyses of globalization often focus on its economic dimensions, like outsourcing, finance, or free trade, just as important are its cultural and political consequences. Policy decisions proceed less in isolation and more in constant comparison to what people around the world are doing.

Chicago provides a telling example of this social-psychological effect of globalization. The traditional Chicago political machine operated through an army of precinct captains, taking marching orders from their particular bosses, all the way up to the Boss Himself, Da Mayor. Television coverage in the 1980s, however, intruded into the inner sanctum of Chicago city hall and the council chambers. Visitors to Chicago would comment, for instance, that they knew all about that night when Mayor Washington’s successor was chosen, since they had seen it on TV in Norway!

This global audience in turn increased the mayor’s and council’s consciousness of their worldwide images, as non-Chicagoans became part of what sociologists call a “reference group” that now extended the world over. That is, leaders would not just ask, “What do Chicagoans think of this vote and of me?” but also “What do others outside Chicago think?” The public images of the city and its leaders, broadcast worldwide, became a direct concern for the mayor and citizens. Media advertising, publically available accounting standards, and efficient service delivery (rather than payoffs) increasingly drove Chicago politics, and thus policy, in the 1990s. The sister city program was expanded. Maggie Daley, wife of the Mayor Daley II, would bring home ideas about urban design from Paris (like wrought iron signs at subway stops and flower gardens on major boulevards), and the mayor would ask his staff to think about how Chicago might incorporate them. That is, what happened and what people thought in Paris, New York, London, and Tokyo mattered in Daley Plaza, in ways they had not before.

Chicago is of course not alone in this regard. Many policy makers are now highly sensitive to the ways in which their communities relate to the wider world. Such comparative thinking can sometimes provoke efforts to catch up with perceived global standards by building amenities that “any competitive” city “has” to have: a natural history museum, a contemporary art museum (preferably designed by a renowned architect), an aquarium, a new symphony hall, and the like. Others add (or sometimes pursue instead) their distinct local specialties to contrast themselves with the rest. Flint, Michigan, won a prize for a walking tour which even local residents said taught them much about their hometown. Mayor Daley II declared that the banks of the Chicago River should become more cultured than those of the Seine; and he hired Chinese speakers to teach Mandarin in Chicago Public Schools. Indianapolis built cultural corridors linking historic neighborhoods while it made its downtown a center for motor sports tourism and conventions. New York City made Times Square a pedestrian zone.

Other examples are in boxes. The general point is that globalization faces policy makers with a set of questions about civic identity. Who are we, what image of ourselves do we want to project to the world, and what audiences are drawn to that image? What do we have here that is similar to and different from elsewhere, and how can citizens, potential new residents and businesses, and possible visitors find out about that? There are no easy answers to these questions, but they are on the table now in a way that is hard to avoid. The tools in this book provide powerful ways to consider them more deeply and precisely. Mayors or planners can assess and measure how their city or neighborhood differs from or is like others within and across contexts, and decide based on that information what amenities and scenes to focus on.

Increasing options. More people’s lives proceed with a strong sense of what we called in chapter 1 “contingency.” This is another way of saying that the path one takes is not given in advance but is experienced as variable and open. Yes, we are all born into a given nation, town, extended family, religion, and from parents with specific occupations and educations. But the question more and more is, where to go from here? To stay or go is being asked by citizens in ways that policy makers have to address daily.

Many cities have focused directly on the group where this sense of contingency seems most visible: the young and talented recent college graduates, the centerpieces of “the creative class.” They change jobs frequently and are more footloose and fancy-free than most. But still, they change cities less often than they change jobs. Thus a critical decision after college or graduate school is where to locate. Policy can reach out to them as citizens and residents who might prefer to change jobs locally rather than moving elsewhere or use help in launching new small firms.

On the other side of the equation, following a major drop in the birth rate after the baby boom of the 1950s, cities and firms are now in serious competition for talent (domestic and foreign) to replace retiring baby boomers. To keep the talent they have, and to bring more from elsewhere, they have to make a case that it is worth moving here and staying, that there is something that makes life here more enjoyable, fulfilling, animated. Hence the international spread of policies designed to build and promote amenities and scenes that might be attractive to the younger and single members of the creative class, who are often thought to be both the most innovative and the most likely to make amenities a centerpiece of their location decisions. But the young and talented are not the only residents, and elected officials who respond too visibly to any one group can alienate constituents who feel left out.

A city’s scenes—overall and within certain neighborhoods, and jointly with job opportunities nearby—are crucial factors in this competition for young talent, as chapter 5 demonstrated in considerable detail. From a policy perspective, if “getting a good job” is the goal, the neighborhood scene is a critical context for defining what counts as a “good job.” A job in or near a vital, engaging scene is often a “better job” than the “same” job elsewhere.

The general point is that as options and comparative shopping for locations increase, the direct market value of scenes becomes more pronounced. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that this point holds only for the young, affluent, and college graduate members of the “creative class.” Retirees, as we showed in chapter 5, are locating in places with better access to natural amenities and the arts. And baby boomers show some of the strongest sensitivity to scenes; their numbers have risen in places that emphasize personal self-expression and local authenticity, like Sonoma, California, or Asheville, North Carolina. Retirees and boomers bring disposable income, neighborhood stability, and high levels of civic activism and volunteerism. And given their size, in numbers and aggregate purchasing power, policy makers ignore the movements of the nonyoung at their peril.

Similarly, as chapter 5 showed, the African American population is increasing in neighborhoods with a range of nightlife and entertainment options and many smaller churches, both more traditional Baptist and newer denominations. These scenes speak to deep and powerful biblical themes, like egalitarianism and charisma, but also to the excitements of seeing and being seen. Bronzeville, Chicago, exemplifies this pattern, but neighborhoods in Atlanta and Memphis, and also elsewhere, are leaders as well. Neighborhood groups, like Revival: Bronzeville, have sought to enliven the local scene with arts, culture, and sport, not only to bring new residents and give them reasons to stay, but also to build a sense of community engagement and neighborhood pride among those who are already there—to become a place to be, not only to be from. Artist Theaster Gates has developed new ways to cultivate neighborhoods’ scenic potentials through innovative interventions into urban space.

At the same time, not only global cities, like New York or London, competing for investment bankers and star musicians, but also smaller towns, looking to draw and retain residents, are increasingly active in thinking about how to create compelling scenes that differentiate them from others. Promoting community gardens, inviting artists to display their work and perform in public buildings like libraries and city hall, facilitating neighborhood walks or bike rides—these are relatively inexpensive ways to build civic pride and increase citizen engagement; scenes like these give reasons for choosing this place over others.

Chapter 4 showed that within specific contexts local authenticity is linked with urban development. To repeat the comment by Mayor Brainard of Carmel, Indiana: “We don’t have the Pacific Ocean, we don’t have the Rocky Mountains. So we have to work harder on our cultural amenities and in our built environment to make it beautiful—and to make it a place where people want to choose to spend their lives, raise their families, and retire” (Brainard 2009). Size and natural endowments are not destiny; as chapter 4 showed, Mayor Brainard was not alone: locally authentic scenes in locations with moderate to low access to natural amenities are nationally significant in key development outcomes like increases in postgraduate shares of the population. Similarly, local authenticity is linked to growth if people walk more. Policy can make a difference: communities without mountains can work to present what makes them locally distinctive. Pedestrian-friendly streets encourage more people to stop and enjoy the local fare.

The general point here is not to hold to one specific policy but to adapt policies by keeping in mind multiple types of groups and individuals who make decisions about where to live with local amenities in mind, including families (not only singles) and the less hip postgraduates (not only young college grads): not only schools, parks, and churches, but also day care, farmers’ markets, karate clubs, skate parks, and more. Some specific examples of small- or midsize-city initiatives are in boxes; these speak against the widespread idea that rising mobility and contingency are disasters for all except superstar global cities like London or New York.

The rise of culture. Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone became a best seller with the argument that participation in voluntary organizations like Kiwanis or the Boy Scouts has steeply declined since the 1950s. It warned of dire social consequences on the way. More people would live as isolates rather than as active members of their communities.

However, even if some organizations have lost members, others have gained. We found a marked increase in the number of people who are members of arts and culture groups.1 Young and low-income persons have increased their arts participation the most. The pattern varies internationally, with the United States, Holland, Canada, and Sweden showing the steepest increases. And it varies across and within cities and metro areas, as we have documented throughout this book. Still, the rise is quite far-reaching. And the level and increase of arts participation and engagement are probably much larger than most official data suggest, due to undercounting of very small arts groups and omitting many popular art forms and new forms of engagement, such as through digital media.2

This rising interest in arts and culture has major policy consequences. More cities are developing official cultural policies and undertaking cultural planning exercises. Municipal cultural affairs departments are growing, in size and confidence, sometimes building bridges with economic development and planning departments.

The shift is most striking in cities with a stronger Protestant history, in which “serious” issues like work, school, and church, and “bourgeois” virtues like thrift and delayed gratification have historically been more central to political culture. Boston is one of the most dramatic cases in point, as are other cities like Minneapolis, Seattle, and Portland. Instead of circumscribing the arts behind high or countercultural walls, they now are more likely to encourage the arts. Further, the arts are increasingly recognized as a potentially key element of urban development, attracting tourism, investment, and new firms and residents.

As more leaders and citizens acquire a more open attitude about the arts, a whole range of cultural policy concerns gains new salience. Arts grants are still central. But so are broader policies directed toward the vitality of the local scene: cleaning up dirty waterfronts, planting flowers, painting murals, holding festivals, slowing traffic, encouraging walking, promoting performances and exhibitions in public spaces, and loosening up or at least streamlining permitting processes for these and similar activities (like mobile food trucks that serve interesting cuisine)—these are some of the policies that many places have pursued to help make neighborhoods into attractive and engaging scenes, which residents and many visitors can enjoy.

At the same time, as more political leaders and officials become more aesthetically open and sensitive, grassroots and minority arts and cultural groups can become less marginalized and oppositional, since they can offer distinctive cultural contributions. Such groups can have a major seat at the table in policy discussions. If they can organize themselves and develop a coherent voice, they are more likely to find political leaders ready to listen.

The bottom line is that precisely how and in what direction to galvanize and connect a city’s cultural resources is an open question—but whether a city should do so is far less controversial than a decade or two back. Mayors and cities are building on arts and culture faster and sooner than most social scientists and journalists report. These are new and dramatic changes for most everyone in North America, albeit less so internationally.3

Diversifying patterns of urban growth. From the 1950s through the 1970s, many big US cities experienced “white flight”: higher-income people of European ancestry would leave mixed-income, mixed-race inner-city neighborhoods for homogeneous suburbs and exurbs. The big city became a symbol of neglect, blight, and danger; the suburb, of wholesomeness and family. These images have been the subject of intense cultural scrutiny in film, novels, and television shows. Migration patterns have also changed. More young, affluent, educated, white persons are moving to central cities. It would go too far to call this shift a reversal of suburbanization or a general victory of urbanism over suburbanism: sprawling Sunbelt cities like Phoenix, Atlanta, and Houston are still among the national leaders in total population growth; suburbs, and Patio Men, as David Brooks called them, are alive and well. But the “back to the city” movement is a dramatic change nonetheless, as many inner-city neighborhoods that were “off limits” to many have seen increasing demand, new development, new amenities, rising rents, and greater racial, educational, age, and occupational diversity.

“Gentrification” is the label often used to describe these changes in migration patterns. It is a helpful term, as far as it goes. It indeed focuses policy attention on influxes of demographic groups who for decades had avoided city living. And it helps to raise the question about what the best response to the changing character of many neighborhoods should be.

At the same time, “gentrification” as an analytical term has its limits, as we discussed in chapter 5. The main problem is that the term presents what is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon as a narrow economic process, where the (active) rich look for cheap rents and drive out the (passive) poor. No doubt this happens, but much else is also at play. “Gentrifiers,” for instance, are not always white—Chicago, Atlanta, and Washington, DC, among other places, have had notable cases of “black gentrification,” which changes the dynamic between “newcomers” and “old-timers” in ways that go beyond rich versus poor. Nor are “gentrifiers” always affluent; many are recent college graduates without steady jobs or children; many come from middle-class families, but others do not, as in the example of “blue-collar Bobos” in Bridgeport, Chicago (see chapter 5), or Asian immigrants in Flushing, New York.4

Moreover, the choice about where to live includes far more than rent, as chapter 5 showed. Proximity to various scenes, to downtown, neighborhood amenities, public transportation, and much, much more are in play. Cheap rent plays a relatively small role per se in this equation—the decision is as much cultural as economic. And while many children of the suburbs are moving to cities, many suburbs are taking on a more distinct urban cast, with denser and more-walkable districts, and “big city” cultural amenities of their own, like performance halls and museums. Suburbs moreover are now the destination of the majority of immigrants to the United States, and increasing numbers of African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans live in suburbs (cf. Lloyd 2012). Broad social and cultural changes are afoot, which go beyond one well-defined and well-bounded group displacing another.

Just as important is the fact that current residents and those labeled gentrifiers themselves are not passive victims of an inexorable process. There are many ways to actively intervene; the story is not written in stone. We reviewed several in chapter 5, but the point bears repeating here. Strong neighborhood associations can work to keep newcomers out, just as they can work with them to integrate new and old; and many of the children of the “old” are themselves part of “the new.” Arts groups can (and have) lobbied city hall to enact policies designed to preserve artist live-work spaces as new, nonartist residents arrive. Newcomers themselves can value the historical character of the neighborhood into which they are moving, including its distinct human ecology, and organize “social preservation” efforts. There are religious dimensions as well, as in the case of Atlanta’s Robert Lupton, a Presbyterian minister whose urban ministry collective seeks “gentrification with justice” (Hankins and Walter 2012). There is no one-track model, but many, many possibilities, none of which are foreordained, and all of which are results of action or inaction.5

The implication again is that responding to diverse patterns of neighborhood change is a widespread policy challenge with no single answer. But it is a challenge that must be met somehow. That is, if many smaller towns face the challenge of how to build scenes that attract new and retain current residents, many big-city neighborhoods have a different “problem”: they have some of the world’s most dynamic scenes, people are flocking to them, and they need to figure out what to do about this dramatic increase in demand. It is an open question whether this means loosening or tightening development restrictions, subsidizing affordable units and artist live-work spaces, building more parking spaces or pedestrian zones and public transportation, high-rises or mid-rises, or some or all of the above, or something else entirely. Different solutions may work better in different places. But some decision has to be taken. And whatever it is will have big consequences for the direction in which a city or neighborhood unfolds, and for the types of scenes it has to offer going forward.

In general, then, the actors and concerns described in many past policy discussions (like gentrification or suburbanization) omit or downplay many new factors and processes featured in this volume. It is thus crucial to pay more attention to these new processes and concerns, which affect increasing numbers of citizens: festivals, flowers, walking, biking, public art, and the like. These policies can build and transform scenes, shifting the dynamics of gentrification and suburbanization, one neighborhood at a time. To capture these multiple dynamics means focusing on more than narrowly economic incentives like tax write-downs. To be sure, business leaders themselves often care a lot about tax incentives. But their employees—and they themselves as residents—are likely to be animated by other, more wide-ranging concerns for amenities and scenes. Business-oriented magazines like Fortune or the Economist now routinely include some measure of culture and “liveability” in their various city rankings, for instance.6 How, then, to specifically develop policies that acknowledges these shifts?

New Directions in Urban Policy

Policy now proceeds in a transformed landscape—global, comparative, culturally infused, with growth centers and fallows in and out of inner-city neighborhoods. Actively including serious thought about the character of a city’s or neighborhood’s scenes is clearly a part of this new terrain. We do not propose any specific policy as better or worse—this is part of the relativist perspective encouraged by sensitivity to multiple scenes and their distinctiveness. Instead we offer some advice about how policy makers can make their own informed decisions about what is best for them, first at national or state levels, and second at local levels.

Two general principles guide these recommendations, both of which flow from the general orientation of this book: contextualize and cultivate. Rather than adopting any purported one-size-fits-all solution, whether a corporate headquarters, new museum, or the like, think of urban policy as a process of cultivating the latent potential of a city or community, somewhat on the model of a gardener. Look around and see what types of scenes are already present, what activities are already animating your streets and strips, and think about what it would take to grow and strengthen these. There are almost always many seeds already present—in the form of active and interested citizens, businesses, resident groups, and so on—whose energy only needs to be channeled in civic directions.

In many cases building up your strengths on the ground may involve adopting some best practices from elsewhere. But “adopting a best practice” from a scenes perspective means thinking about how that practice may fit together with and mutually benefit what is already there, much like a painter must decide whether adopting a new technique or adding a new figure will harmonize with the other elements of the scene. Here is where the second principle fits in: pay attention to context. No city, no neighborhood is an island; each has its own unique identity that comes into sharper view in comparison to others. This is why we often compare the scene in every US zip code to others or subgroups of others, not only in terms of amenities, but a whole host of variables relevant to policy, from population to density to education and beyond. From a policy perspective, this approach permits local officials to in effect travel around the whole country without leaving home, learn how their cities, their neighborhoods differ from and are similar to others, and evaluate the development consequences.

Higher-Level Policy

At higher levels of government, achieving most local policy goals, at least in fiscal terms, implies transferring funds to local governments. Local governments are closer to social problems and citizen concerns. Higher-level governments have better access to funds, yet many are hesitant to transfer these resources to local governments without strings attached in order to account for and evaluate the effectiveness of local spending. And sometimes national, state, and provincial officials feel they should reset local priorities.

The challenge, then, is to give local governments room to respond to the local problems and concerns to which they are most sensitive while maintaining more general accountability norms so as to assess whether funds are being spent wisely. One common solution is for experts, who survey a large number of cases, to identify “best practices” that others might adopt, like testing public school students. Yet best practices often fail to transfer from successful locations. Why? The context or assumptions for the best practices are often weak or absent. This implies that policy makers must be highly attentive to how their situation is similar to or different from those in which other policies have been developed, and think about how to adapt accordingly. How to do so?

Build on successful scenes and integrate them into existing programs. There are lots of small examples that work. Look for specific types of institutions and program areas that have grown and are successful, especially new areas like arts and culture but also sports and park programs from basketball to dance to pottery. In Chicago, for instance, many such programs were joined with the public schools in a seamless afternoon program that continued with the Park District after school for a few hours each day. Toronto city officials work with community partners to incorporate unique cultural spaces into social housing, such as recording studios, music practice rooms, and performance spaces. While funding cuts are often challenging, in many cases they have spurred parents and neighbors to spend their own money. The number of day care programs the world over has been increasing, and much of their “agenda” is arts and culture for the young, complementing the “hard work” of the schools.

There is a common theme to many of these organizations: namely, citizen empowerment. These organizations seek to engage people with activities they already enjoy and to channel that energy into work, school, and community, as well as personal growth. Recognizing the social value in such groups means explicitly acknowledging that education has to be more than memorizing the three Rs. The arts, for instance, are a quintessential arena for teaching innovation and collaboration as growing out of “play,” and beginning to link it to advanced creativity and cooperation in every field. Joseph Yi (2009), in God and Karate on the South Side, shows that for many youth, black, white, and Hispanic, karate clubs impart an engaged, participatory ethos, demanding that their members perform and achieve at ever-higher levels, building tight, cross-racial, cross-class personal friendships that cement participants together and forestall deviance. Learning how to support scenes replete with these self-empowering organizations is central for developing the sort of wide-ranging education policies that can help young people do well in a world in which creativity and personal expression are key to success.

An example of national policy moving in this direction is the “creative placemaking” initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts initiated by NEA chairman Rocco Landesman and elaborated in a white paper by Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa Nicodemus. This initiative is intriguing for a number of reasons.7 It led to ArtPlace America, which created partnerships between the NEA and nonfederal organizations such as the US Conference of Mayors and the American Architectural Foundation while at the same time building links with other federal agencies (eight in all) such as the Departments of Housing and Urban Development, Transportation, and Health and Human Services. And it attracted significant funding from nongovernmental sources. Grants were redirected toward arts initiatives designed to support distinct places. In subsequent rounds grants went to proposals with nonarts partners, like botanical gardens, religious and scientific organizations, farms, educational institutions, and even the US Army. At the same time, other nonarts agencies started to include the arts among their priorities, with, for instance, the Department of Education including arts language in its Promise Neighborhoods application guidelines.

Other jurisdictions have experimented in similar ways. The State of Michigan sponsored a Cool Cities annual conference and offered prizes for specific local programs. The City of Chicago required that every city department incorporate some type of arts activity into its regular programs. This even led some (historically aloof) police officers to perform in improv theater alongside neighborhood youths; laughing at the awkward cops reportedly built neighborhood solidarity. Boulder, Colorado, prohibited many national franchises like “big box” retail stores deliberately to counter “Hollywoodization” and to encourage local artists, architects, and entrepreneurs. Not all are resounding successes, but that is the nature of experimentation. The key is to learn and adapt.

Be open to intermediaries. This is how many “new” programs have originated—with good ideas from below. But it would be a mistake to pick one single, consistent policy or program to apply equally to all places. One size fits all is preordained to failure (e.g., a federally mandated karate club on every street corner). Uniformity is what gave past national government programs their worst reputations. Such uniformity led many countries to transfer much of their welfare state activities to lower-level governments, even if the tax power of the national government leads in funding.

The most respected programs by local governments were those with the fewest strings attached, with general revenue sharing and some broader categorical grants in the lead. But there must be some strings, and the difficulty in conforming to them can make life challenging for the huge numbers of very active small and fragile organizations that are transforming and animating cities and neighborhoods. Especially in low-income areas, these small organizations, often held together by a few committed members, can play a major role in making scenes with big social payoffs: activating community pride and imparting transferable skills like self-discipline, focus, creativity, teamwork, and self-expression.

Such groups are often woefully underfunded. Part of the underfunding flows from a concern by governments and foundations that the small organizations (some are too small even to become official nonprofits) are not able to “manage” or “account” for grants properly, exposing the grantors to potential scandal or investigation. There are enough difficult past cases to lead many potential grantors to stay with safer, larger grantees.

One potential solution is to develop or expand existing efforts by intermediary organizations. Good examples are the South Shore Bank and Chicago Community Trust, and similar small local foundations, which obtained funds from individuals and foundations and channeled them to small outfits. ArtPlace America is a national example. Making awards to intermediate-level organizations like these and creating others such as a neighborhood arts coordinator are potential options. Such intermediate organizations could write checks to smaller groups under their umbrellas and serve as buffers between the demanding national accounting standards and the flexibility of individual organizations that cannot afford accountants and lawyers to do everything necessary to keep procedures legally correct.

Participate in regional planning. Many local policies do not get implemented even if strongly desired. Certain types of investments or programs demand too much money or too long a time perspective to justify to taxpayers. Others affect and might benefit an entire region, but for this very reason are not enacted locally because each city is worried about the others free riding on its efforts.

Regional transportation is a classic instance. Each locality in a bigger region is likely to benefit from a coherent public transportation policy, but none has a direct interest or ability to make it happen. Regional tourism policies are similar, as individual cities within regions have much to gain by developing suites of amenities that complement rather than compete with one another and by disseminating a common message to potential visitors about what the region has to offer. Federal and state governments can be key mediators in these areas.

Major development initiatives are similar. They can sometimes take decades, passing through successive local political regimes, none of which can lay claim to “delivering the goods.” For this reason, Toronto’s massive, 30-year waterfront redevelopment project is being overseen by a special agency, Waterfront Toronto, which was created and funded jointly by the city, province, and federal governments, and acts with relative autonomy. This is one example of the sort of higher-level intervention that can be crucial in supporting scenes that affect entire regions. Of course, regional planning bodies are no panaceas—they open up their own challenges, as new policy players can create new vested interests and new conflicts.

Be an information hub. Federal and state governments can help spread information about locations and their scenes to enhance the quality of choices by individuals and firms. The US Census Bureau and other agencies do this presently, but they could do more to provide information about available amenities and consumption opportunities across US cities and neighborhoods, together with information about environmental quality, access to nature, and the like. Such information is absent or not readily available in the census. But it can be crucial for many families and businesses in determining where to locate and for local officials in assessing their own locality’s offerings relative to others. Federal agencies could play a more active role in encouraging tourism, providing more information to potential visitors, as well as new residents, from inside and outside the United States. Other countries, especially in Europe, have more active cultural observatories and collect more data on tourism. Yet in the United States, for example, there is virtually no data on local tourism reported systematically by the federal government. This book illustrates the types of data and analyses that could be expanded and refined.

Local-Level Policy

National, state, and regional policies typically operate at a level that is too general to make direct decisions about what specific types of scenes, amenities, and organizations to promote and protect. At these higher levels, funding, tax exemptions, vision statements, and the like are the main policy tools. Local policy makers, however, make many decisions that directly affect their scenes—about zoning, land use, cultural district designation, parks, parking, pedestrian zones, and public transportation, as well as liquor, patio, noise, or street performance permits. And there are also the specific tools of urban cultural policy, such as arts grants, festivals, or artist housing, which directly affect local scenes as well.

Still, many policy-making decisions even among local officials are macro and top down. They often aim at a general policy for all, like a new convention center to spur economic growth. Yet most local areas contain considerable internal diversity. No doubt some areas have homogeneous policy preferences, but most do not. It is therefore crucial to consider policies that can respond to diverse, neighborhood, scene-specific concerns. A policy that is highly effective in a self-expressive scene, like building a tech cluster, may not work very well in a traditional or neighborly scene, which may benefit more from different amenities, like karate clubs or skate parks or community arts centers. This internal diversity makes it especially important to formulate policy while considering views from below, from average citizens. How to do so?

Look more specifically for examples of all 15 dimensions of scenes in your locality. If some seem largely absent, ask if you want to add them, or decide which to pursue. Smaller areas especially should be modest and focus carefully. Be prepared to build on strength, and highlight those salient to local participants. But look a bit, and maybe ask around, before deciding that there are no citizens who want X, especially if this implies policies that you may not be pursuing. Any policy under consideration can be assessed in its impact along the 15 dimensions described in chapter 2; they offer a broader framework than most current cost-benefit analyses. They add consumption to production criteria. That is, they encourage thinking not only about who wants to work here but also why they would enjoy living here.

Conduct an inventory of your local amenities and how they compare to other locations. Even if you know every church and restaurant and park in town, almost no one knows how the numbers and types compare to other locations across the region. Our main data are publically available and can be accessed by request. Specific groups provide details in their areas, like restaurant associations or sports leagues. Ask related questions: Where do citizens go for Saturday night or the weekend? How many leave town? What attracts them elsewhere that might be added locally?

Build on distinctiveness and strong local resources. Examples include a church, talented League of Women Voters, and great high school football team. Consult with participants/experts about how their activities might be used better and possibly generalized to other neighborhoods. Assemble ad hoc teams to review a range of policies and report back (e.g., on how to rebuild on a vacant land site). In choosing team members, consider including participants representing many if not all 15 dimensions. That is, if you are building a skate park, bring parents and skaters and graffiti artists and nearby residents to the table. Encourage incorporating multiple scenes perspectives if not in one project, then across several projects.

Drive slowly, or better, walk or bike around your whole local area, stopping to talk to neighborhood residents. Look for scenes that engage or enrage different sets of citizens. Ask them what scenes they cherish or abhor, and how to improve. Moreover, ask not just about a restaurant, but what else nearby makes it a destination—parking, shopping, the people, the view, pollution, crime, music, street cafes, and so forth. These are the components that build a holistic scene. Ask your staff or colleagues and friends if they could do the same, say, for one week, then meet and confer. Many mayors do this regularly, taking notes on what to change. Professionals can be engaged to do surveys in depth, but assess the terrain yourself first and listen to local folks with experience. Ask about what failed in the last decade, and why, as well as about new successes nearby. Consult the Internet for new ideas that might work locally; look for examples of activities/amenities for all our 15 scenes dimensions that might fit locally, and assess if or how they could be supported in your area.

“Talk to people” may not seem like a very radical cultural policy suggestion; but it contrasts rather dramatically to other approaches, which often begin from the top. Since the scenes approach begins instead from on-the-ground activities, it encourages policy that begins there as well. Start, that is, with what residents and visitors already enjoy and are energized by, and think about how to grow from there. Think like a movie director, not like a military general.

Know the local rules of the game. Some US cities are closer to the historic European capitals of culture, like Paris, Berlin, or Vienna—deeply engaged with the arts and scenes ideas, looking for details and specifics. Others need to be convinced of basics: the value of amenities and scenes at all. Be aware of where each of your communities stands, and calibrate your policy proposals accordingly. Where basics are at issue, specificity can distract from the big picture; where specifics are needed, grand visions can be vacuous.

Attend as well to the dynamics of local political culture. As we showed in chapter 6, new social movement (NSM) organizations (e.g., for environmental and human rights) thrive in specific local contexts: urbane, walkable, self-expressive, artistic, dense. Outside such urbanist settings, NSMs are rare, and their associated agendas may be met with bewilderment, indifference, or resistance. Policy pushing for avant-garde arts, glamorous scenes, and entertainment districts may seem alien and dangerous. Instead themes of neighborhood and community may be more effective, such as neighborhood festivals, walks, and gardening. The support of community leaders like school principals and local business owners may be key. Likewise, where local politicians, rather than activist organizations, tend to initiate policy from the top, linking the public benefits of scenes to their personal reputations and electoral success can be important. Know the context, and think about how to frame scene ideas to maximal effect.

What Impacts Can You Expect from Building Your City’s Scenes?

None of these remarks are meant to be too surprising; they only codify for exploring in your area what many mayors and officials have already been doing for some time. However, this policy case for scenes and amenities often confronts the assertion that they are too soft or intangible for bureaucratic planning frameworks. The scenes methods and data in this book provide an opportunity for culture and amenities to join the traditional “harder” variables of urban and community policy, like budgets, density, population, or crime. And, as this book has shown, the consequences of scenes for the fortunes and fates of localities can be major. Showing this with numbers can be a crucial policy lever.

Consultants often assess potential policy impacts by showing “multiplier effects” that come from adding a new museum or sports stadium. These predictions are typically highly unreliable when based on one single organization like a stadium and often without an adequate comparative basis. One major advantage of our approach is that it combines hundreds of indicators to provide a read of the overall scene. We stress not just considering, say, a convention center but heightening or changing the overall feel of a neighborhood or city and assessing impacts against every other neighborhood in the country.

This approach implies considering projections based on scenes data using economic cost-benefit types of tools. For instance, we find that in general a 10 percent increase in the degree to which a neighborhood’s scene promotes personal self-expression is associated with nearly a full percentage point increase in the share of the population with a college degree (e.g., from 5 to 6 percent)—even accounting for other variables in our Core models, population, rent, education, race, and more. While a one-point increase may seem small, a host of research shows that this sort of difference is major compared to most other policies.

Of course, this is ceteris paribus—all else equal—and all else is rarely equal. For instance, given that self-expression is typically (but not always) negatively correlated with tradition, boosting self-expression may create conflict. In these places, one might generate more support by linking the scene more closely to local authenticity, which is often positively correlated with both self-expression and tradition—small galleries, local poetry readings, nature walks, heritage, church painting groups.

For places that already have strong self-expressive scenes, it may make more sense to focus on increasing access to these scenes and connecting them to related media, culture, and technology businesses. Some potential options are public transportation, more intensive residential and employment development, reserving below-market rentals for artists and the needy, and innovation hubs that put arts groups, tech firms, design firms, social advocacy groups, and the like in the same building. In such policies it is crucial to be sensitive to how new development might alter the character of the scene and to listen to its spokespeople. If no one is vocal, go out and find them.

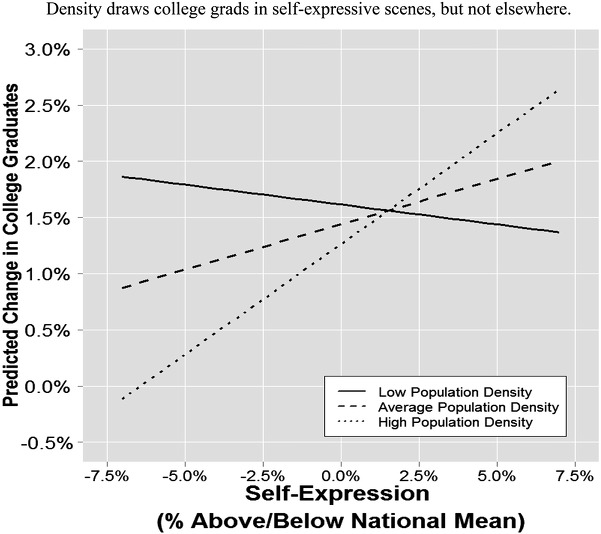

Figure 7.1 shows the potential this sort of approach holds. In zip codes with relatively low concentrations of self-expressive amenities, density does not bring increase in the college graduate share of the population. But high density and high self-expression combine to draw college graduates. Figure 7.1 graphically illustrates how this relationship between population density and changes in the college graduate share of the population shifts across self-expressive scenes. Start on the left, showing zip codes with low self-expression scores. The dotted line indicates that high population density has an impact of 0—density does not increase college graduates. Now look at the far right, at zip codes with highly self-expressive scenes. Here density is strongly connected to college graduate gains—dense zip codes in self-expressive scenes saw an average increase of around 2.5 percentage points in their college graduate share of the population, whereas college grads in less dense, self-expressive zip codes increased by under 1.5 percent. In other words, for places with scenes that are already highly self-expressive, increasing density may be an effective strategy to enhance the power of the scene.

This figure shows how the impact of population density on change in the college graduate share of the population shifts across self-expressive scenes. The figure is read left to right, where the y-axis indicates the predicted change in college graduate share of a zip code’s population from 1990 to 2000 (accounting for our Core variables), and the x-axis indicates the degree to which a zip code’s (BIZZIP) self-expression performance score is above or below the national mean.

This is a simple example to help assess impacts of just density and one dimension of scenes, self-expression. Look through other chapters for examples with other dimensions. There is of course no substitute for judgment, and judgment is always situation specific. But you can make informed judgments by comparing your city or community to others and thinking about how your scenes are similar and different. Yet no matter where you are, the character and direction of your city’s scenes can help inform policy discussion—not just as a narrow “arts” question but instead as linked with the overall economic, social, and cultural development of your community.

A Toronto Example of How to Integrate Scenes into the Policy Tool Kit

It is one thing to think about scenes and local policy. It is another to integrate such thinking into a city’s formal policy-making processes. Here the hard slog of bureaucratic reports and policy meetings, as well as political savvy, networking, and public relations, are indispensable and unavoidable. We report here on lessons learned in helping integrate aspects of scene concepts into Toronto’s official development policies.

Historical Background, or How Toronto Embraced Expressive Culture

First, some quick background shows how much Toronto has changed economically, politically, socially, and culturally. These changes mirror many discussed above, but in a specific local context.

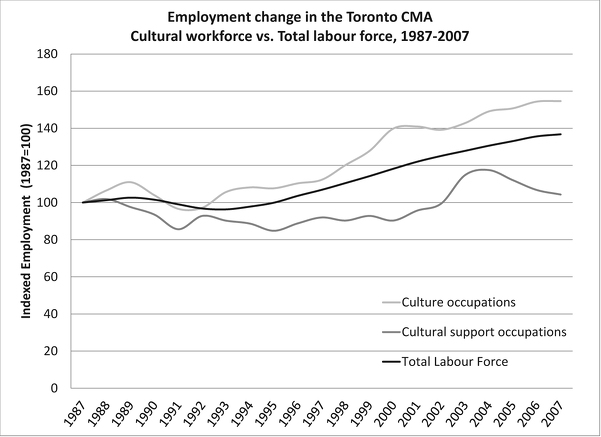

Economically, especially since the early 1990s, manufacturing jobs have declined, service and finance occupations have grown, and the postindustrial “creative occupations” from fine arts to graphic design to technology and R&D have rapidly grown. Socially, waves of immigrants have settled in Toronto, bringing with them new cultural traditions. Starting in the mid-1950s and 1960s, a first wave was from Southern and Eastern Europe. They were followed by countercultural Americans, escaping the Vietnam draft. Others have come from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean in steeply rising proportions and absolute numbers through the 1980s and 2000s. At the same time, the city’s average household size was declining, especially in the central city. Politically, in the late 1990s, the City of Toronto was amalgamated with five of its suburbs. Previously connected in an awkward two-tier metro-city arrangement, the new “megacity” instantly became the fifth largest in North America.

These economic, social, and political changes have a cultural component. Postindustrialization means more people working in and around the arts; international competition for skilled workers has led civic and political leaders to promote the arts and culture as a carrot for attracting globe-trotting young and dynamic creative workers. New immigrants have introduced diverse culinary and cultural traditions, from cappuccino to roti. Shrinking household size has increased demand for public spaces of sociability and enjoyment outside home and family, like restaurants, plazas, cafes, and music venues. The birth of the megacity spurred initiatives to make Toronto a “world-class” city, with its cultural offerings centrally featured.

The most visible consequence has become known as the “Cultural Renaissance.” Most notably, star architects Daniel Liebeskind and Frank Gehry produced strikingly controversial designs for two of Toronto’s most traditional cultural institutions, the Royal Ontario Museum and the Art Gallery of Ontario. But the “rise of culture” is broader and more deeply integrated into Torontonians’ daily experience than a few redesigned buildings.

Since 2001, Toronto has seen dramatic increases in a host of cultural and expressive organizations and amenities. Nearly all are growing at rates faster than total businesses. Some much faster: for instance, interior designers and dance companies more than doubled between 2001 and 2009.

Ernest Hemingway wrote a column for the Toronto Star in the 1920s and regularly went back and forth between Paris and Toronto. He once complained, “How I hate to leave Paris for Toronto, city of churches.” There are now in Toronto more holistic health centers, acupuncturists, yoga studios, and martial arts schools per postal code than there are churches and religious organizations.8 Daily life, that is, takes place increasingly outside of the traditional venues of the bourgeois, Victorian culture that historically defined Toronto, which was termed in the past Hogtown for its industrialism and Toronto the Good for its Victorian moralism.

Local arts activism rose in the early twenty-first century, with an increasingly active cultural affairs agency, enhanced by a merger with the city’s Economic Development Division. Civil society activists are vocal. BeautifulCity.ca organized lobbying efforts to impose taxes on billboards, with revenue earmarked for the arts. The ArtsVote movement, which proclaims, “I am an artist and I vote,” holds mayoral debates and issues report cards about how arts friendly candidates for city council are. They exercise classic pressure group tactics, targeting key districts where bloc voting by the rising number of people working in (or married to those who work in) the arts can make the difference in low-turnout elections.

Lessons of From the Ground Up

With more residents, businesses, politicians, and civil society groups active in the cultural field, the role of the arts in the city’s economy and residential communities became hotly debated. Silver’s (2012) “Local Politics in the Creative City: The Case of Toronto” explores two cases. One, discussed in chapter 6 of this book, centered on a residential neighborhood with abandoned streetcar repair barns: Should it be torn down to make room for a traditional grass-and-trees-and-playground park, or turned into artist housing, exhibition and performance space, a farmers’ market, community food bank, environmental education center, and more? The other case highlights a grassroots and independent artist community, where many young artists had for a decade occupied former industrial spaces and warehouses. Rents were rising, condos were coming in, and the arts groups and supportive businesses organized in the name of “good planning” that would preserve a foothold for creative and cultural work in the neighborhood as more and more people arrived.

Source: From the Ground Up: Growing Toronto’s Cultural Sector (Silver 2011b). Courtesy of the City of Toronto and Tara Vinodrai.

Both cases show on-the-ground political disputes that energize policy questions with passion, making the character of the local scene into a matter of controversy and dispute. While these disputes ended in ad hoc settlements with little direct official policy influence, they pressured city officials to more tightly link cultural policy with land-use planning. In other words, they started public discussion and conscious consideration of what makes places distinctively engaging and attractive—they sparked explicit policy discussion of scenes.

The question was thus raised in city hall of how to build a policy infrastructure that would make protecting and expanding the city’s scenes a general concern across the city’s neighborhoods, together with classic issues like height, zoning, and density. This focus on place was not entirely new. Cultural Services in the last decade had grown increasingly involved in planning issues, hiring for the first time a former planner, who then collaborated with local architects, in ways that dovetail with the scenes approach, to map all of the city’s cultural facilities and categorize them by uses, such as showcase or heritage or incubation. But these connections between culture and planning gained extra urgency as they took center stage on the local political scene.

A working group had been meeting, of which Silver was a part, called Placing Creativity. At the initiative of the Economic Development and Culture Division, some participants in this group produced a report, From the Ground Up: Growing Toronto’s Cultural Sector (Stolarick et al. 2011; Silver served as editor and coauthor). One of its major goals was to generate new tools based on hard data that would pass muster with Ontario planning regulators while also building a platform for integrating cultural issues into the municipal planning process. It also had to convince potentially skeptical city councilors and citizens.

The report has three main chapters: (1) “Economic Analyses of Toronto’s Cultural Sector,” which charts trends in cultural sector jobs relative to other sectors; (2) “Cultural Location Index,” which maps where Toronto’s cultural workers live and work, as well as where cultural facilities are; and (3) “The Economic Importance of Cultural Scenes,” which explains how concentrations of cultural activity create added economic value while illustrating these processes via case studies of particular people and places, highlighting how creative people help make vibrant scenes and vibrant scenes help creative people to do their work better.

Rather than summarize the report, which can be downloaded, consider some general lessons that come from the process of producing it.

Bring together people with multiple types of expertise. Collaborators included geographers, architects, cultural planners, sociologists, graphic designers, and urban designers, as well as key figures in the local music and more broadly independent art scene. This improved the overall quality of the work while generating credibility—professional, academic, cultural—from multiple sources. It is an example of bringing some of the many scene dimensions together. The report moreover was initiated and coordinated by the economic development side of Economic Development and Culture, not the culture side. This gave it additional credibility as speaking to “hard” rather than “soft” issues and opened doors that might otherwise have remained closed.

The fact that meetings were held at the Martin Prosperity Institute (MPI), an independent academic think tank, was key in this regard. It provided a neutral space comfortable for all participants. The MPI is Richard Florida’s main research center, and the opportunity to interact with him and his associates was likely attractive to many participants. City and provincial officials from different departments who rarely interact could meet outside of city hall and engage in freewheeling discussions. While not every city has a Richard Florida, most cities are near a university, where academics can mingle with policy makers and other cultural policy stakeholders at coffee klatches and the like, which can blossom into more serious collaboration. Museums or art centers are other good venues.

Providing the opportunity for cutting-edge work is also important. For the academics, these meetings were an opportunity to work with data in ways that are new, even relative to specialist journals. For instance, we analyzed separately both where arts and cultural workers live and work, which is relatively uncharted territory from a research perspective. Designers got to experiment with new types of maps and data-presentation techniques. Planners felt they were pushing their discipline’s boundaries. Artists got to discuss theories with intellectuals and articulate their role in the community. This interaction creates more excitement among participants, since it engages their professional creativity and imaginations in addition to their civic activism.

Make it pretty. A team from the Ontario College of Arts and Design University (OCAD) made glossy foldout maps as well as a limited number of poster-size maps. Aesthetics matter. Many folks are drawn into the ideas because they are drawn into the beauty of the presentation. Posters can be distributed to city councilors or others to display. This gets people used to talking about the importance of culture in the city and gets them to think about why it differs across locations. A simple idea that could work in many contexts.

Work is changing, not only declining. Many politicians see empty factories and warehouses and conclude that jobs and industry are leaving the city. They infer that residential and retail development is the only way to reanimate the inner city. While these matter, the report demonstrates that in Toronto, though large-scale cultural goods manufacturing (like printing or record production) is declining, the cultural sector in general and especially its creative core is rapidly growing, more so than other key growth areas like finance and biotech.

Much of the city is reindustrializing rather than postindustrializing, in other words. Acknowledging this difference changes our view of the possible: an empty warehouse or big-box store, for instance, transforms from a blight to an opportunity for experimenting with new ways of linking work, residence, and play. Zoning the warehouse out of existence forestalls this creativity. The general, transferrable point is that what might be bad news from one perspective can be good news from another. Be open to many perspectives.

Cultural clusters are often under the radar. It is easy to find a finance district: just look for the corporate logos. Tech firms have a sign on the door. You can smell bread baking at a bread factory. But arts and cultural activities cut across traditional distinctions between residence, employment, and retail uses—they happen in all three, and it is hard to separate them. The West Queen West neighborhood had one of the highest concentrations of arts workers of any neighborhood in Canada, but nobody could prove it in order to show its relative importance to the city as a whole. The impact of new developments on similarly significant biotech or finance clusters would without question figure in planning decisions for their neighborhoods. For policy makers to similarly consider arts and culture clusters, they need to know that such clusters are there. Hence we made maps showing them.

Analyze both where people live and where they work. One major finding of the report is that artists and cultural workers differ from the rest of the workforce in where they live, but not so much in where they work. The difference is that they disproportionately live (a) in the central city and (b) near one another. Their presence is a key element in what makes the central city attractive and intriguing to others.

That they cluster together also suggests that they gain benefits from being near one another. And this implies that a supportive scene can feed directly into their work. That this is not a phenomenon unique to Toronto we demonstrated in chapter 4. Artists in an arts-friendly scene generate significantly greater economic growth than do artists in a less arts-friendly scene. This is a strong justification for urban policies designed to maintain a strong link between artists and scenes, perhaps through subsidizing artist housing or expanding the housing stock, so that artists and other low-income persons can afford to live in gentrifying scenes. Consider options that work for your locality.

Link numbers and maps to people. While numbers and maps are important, in the end the goal was to show how access to distinctive cultural scenes empowers people to improve their lives. We thus included in the report short case studies, quasi-ethnographies, that feature key scene makers. These illustrate how these individuals helped create Toronto’s distinctive scenes that many others enjoy and benefit from, as well as how their own work was enhanced by easy access to a scene. This takes us beyond dots and charts, and animates the message with human interest. While the particular stories and scenes would differ in different cities and neighborhoods, the goal of humanizing scene policy does not.

Offer language and logic for explaining why scenes matter. Maps and trend lines show what is happening and provide important policy tools. But these take on more meaning if policy makers have a language and logic to explain to themselves and others why these matter. Hence the main thrust of chapter 3 of the report, “The Economic Importance of Cultural Scenes.”

This chapter outlines several mechanisms through which strong scenes can generate prosperity. For instance, on the consumption side, they can keep spending local that might otherwise leave town (e.g., through “staycations” rather than vacations), cultivate nascent interests and hence expand local participation, draw new residents, retain existing ones, and more. On the production side, the right scene can provide supportive yet critical networks crucial to experimental and risky work, place branding, technique- and idea-sharing opportunities, and more. These are clear and simple processes; enumerating them explicitly can encourage decisions with a firmer understanding of why and how these processes should work.

Avoid one-size-fits-all recommendations. The report’s specific policy recommendations lay out multiple possibilities for different situations. Some examples include publicizing relatively under-the-radar scenes, connecting them better to one another, and exploring cultural district designations. In addition, we stress that sometimes “hands off!” is the best policy, as a scene can thrive on organic, spontaneous growth that too much intervention can spoil. More important than the specifics is to expand the horizon of what is possible when plans and policies are formulated.

Keep the energy going after a plan or policy is written. Officials who work in complex organizations like city government know that writing a memo or report is only the first step of the game. One has to keep at it, for months or years.

Getting a hearing at related agencies is crucial: the report made its way to the planning department and the culture department, for instance, where their staff attended and discussed it. Elected officials need to be engaged, especially the leaders of key committees. Maps can be tailored to specific political wards but also designed to show the general importance of vibrant cultural scenes to the city as a whole. The report’s maps were warmly received even by city councilors without reputations for being stalwart friends of the arts. Also important is to integrate ideas emerging from different reports into a coherent general cultural policy message. From the Ground Up was featured in the city’s new culture plan, which explicitly mentions the importance of scenes as a cultural development goal with the city’s general commitment to creative place making.

The challenge here is to convey to others the energy that lies behind the final product. City staff obviously have to take the lead in keeping a new policy tool or idea on the bureaucratic agenda. But they help themselves by inviting their collaborators to city meetings, and their collaborators can help by accepting the invitation. Getting the whole group together, or at least a few members, shows an ongoing commitment to the ideas. It also models to others the types of innovative collaboration that are worth pursuing further. Simply getting the word out can make a big difference. Staff think about and perceive their options in a different light—maybe somebody notices something about a development proposal she would not have without having discussed the ideas, or is inspired to pick up the phone to call a colleague in a different department about an issue that she would not have otherwise seen as an opportunity for collaboration. These informal results are “policy outcomes” that are also important, even if they do not make their way into official plans or legislation.

Principles of Scenes Policy

A few simple principles help synthesize the main lines of a scene-based urban policy. The most general principle is that understanding policy options means linking macro-global trends in the economy and society to local context and political culture. Here’s how to do so:

1. Consider the specific people, actors, groups who have a stake in policy issues relevant to scenes—cultural affairs departments, cultural industries, nonprofit cultural organizations, activist groups, citizens, mayors, artists, residents, youth, and so on. The particular constellation of actors will vary in different places, as will their influence and resources. Success depends on bringing these groups together and aligning their interests.

2. Be flexible, and promote flexibility in others. Remember that many new projects fail; put your eggs in multiple baskets. Consider not just one project like a library, museum, gallery, or restaurant, but how to combine many such amenities, private and public, to build an attractive scene.

3. Measure success by empowerment. Making a difference often means enabling more people to make a difference for themselves. Consider what scenes best allow citizens to do and be the best version of themselves. Standard measures are when people move to or away from a neighborhood, or it rises in average education or income, but watch for more subtle processes too, like turnout at local meetings, neighborhood cleanups, and festivals, or how local folks talk about these issues. Be sensitive to competing criteria and how to respond variously—for some folks not raising neighborhood rent or income is a goal.

4. Achieving specific goals is important but so is building organizational capacity. Think about policy outcomes not only in terms of which groups get what they want. We may not get everything we want today, but we can change how the game is played, add new players, and help build new policy tools and ideas more deeply into policy-making mentalities/institutions. This is key for new groups and scenes, like artists or youth groups.

5. Talk to citizens, and listen to their concerns. Don’t say “if we build it, they will come.” Instead ask what people want first, and assess nearby projects. Then ask the planners and architects to include these concerns in new land use and building. Ask them to comment on how individual projects may affect area scenes.

These points are neither radical nor new. But their very simplicity can often be what makes them difficult to stick to, especially when there is usually some proposal for some new universal engine of urban prosperity making news. Yes, look far and wide for new best practices. But the point of doing so is to learn more about yourself, to get a clearer picture of what scenes you have and what might be done to build on that distinct character.

The concepts and techniques in this book provide a way to do so: to situate your local scene in the context of many others; define more precisely what scenes are here and how their key dimensions work; to learn how much is shared with others, how much is not; and to bring some data to bear on the question of how important these similarities and differences are in shaping your community’s future. These activities have encouraged innovative policies and outcomes in other places and could do so in your area too.