6

Scene Power

How Scenes Influence Voting, Energize New Social Movements, and Generate Political Resources

With Christopher M. Graziul

Les Frigos is a Parisian artist collective in an abandoned rail yard of a traditional working-class neighborhood. After occupying for decades a building formerly used to cool train cars, the artist community in “the Fridge” became a focal point of the Paris underground art world in the 1980s and 1990s.

The Mitterrand national government and local authorities designated the surrounding area for one of the most ambitious redevelopment projects since Haussmann. Les Frigos did not fit into their plans and was designated for demolition. The artist community rose up, and after years of political struggle, they successfully prevented destruction of their building. Further, they carved out a recognized place for their activities within the city’s official policies as a core part of the evolving neighborhood (Sawyer 2012). Les Frigos activists joined traditional working-class solidarity themes with new issues, like preserving suitable sight lines from their building to the Seine. More generally, they sought to maintain a tone for the neighborhood—an anarcho-punk, transgressive feel—as glass and steel buildings went up around them. They fought, in other words, for a scene.

These refrigerator rebels are far from alone in linking scenes and politics. Successive local and national governments in Seoul, Korea, worked to beautify waterfronts, create cultural meeting points, and establish the city as a center of fashion and design, often meeting bitter resistance on the way. Bogotá’s charismatic and flamboyant (independent) mayor (and Green presidential candidate) Antanas Mockus sent mimes into traffic jams to encourage civility among drivers; he had opera troupes perform in poor neighborhoods to show that culture transcends class differences. Similarly ambitious political programs have emerged around the world, with the character of the scene sometimes taking center stage as a topic of political controversy and target of public policy.

These developments are part of larger transformations in many political cultures. Classical divisions between left and right are being redefined, and the range of politically salient issues and identities is expanding and diversifying. Thus, in the United States, a Republican candidate, George W. Bush, ran in 2000 on a platform of “compassionate conservatism” in which the government would have a significant role to play in improving peoples’ lives. While in office, he expanded Medicare and instituted new social programs such as No Child Left Behind. He left office with a government much larger than when he started. By contrast, Democrat Barack Obama, after a large Keynesian stimulus package in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008, reduced the number of government jobs and purchases yet came out in support of gay marriage. Here are elements of the “third way” or “new political culture” tradition from Bill Clinton to Tony Blair, which melds fiscal conservatism and social liberalism.

We live in a highly complex and diverse political culture. No single factor (like affluence or education) can explain who votes for whom or where and why some political movements (like Les Frigos) thrive in some places but elsewhere fall flat. Left and right have assumed many new meanings in different contexts.

Discovering origins of these new patterns is a job for which scenes analysis is well suited. Such analysis encourages a broader view of politics—linked not only to individuals’ wealth, education, ethnicity, and religion, but also to the full range of meaningful experiences they reject or embrace. From tradition to transgression, our scenes dimensions and amenities database can capture and detail specific cultural aspects of the environment salient to national and local political scenes. To understand this landscape, we need to bring new concepts and new data together with the tried and true methods of political analysis.

The chapter proceeds in four major sections. The first discusses how scenes provide resources to mobilize for politics. Scenes grow more politically salient in general with (1) the rise of culture, (2) the rediscovery of the urbane, and (3) the new political culture. The specific dynamics of scenes’ political potency center on what we call “buzz,” the valuable resource that scenes can generate, which may be exchanged for other resources, such as money or trust, used as a political weapon, a mobilizing tool, and more. The second section illustrates how scenes and their buzz can permeate local politics by examining an episode from Toronto local politics, where groups clashed over transforming an abandoned streetcar repair yard into an arts and community center.

The third section compares all US zip codes, identifying the scenes where new social movements (NSMs) thrive. NSMs arose after the 1960s to support human rights, the environment, and social justice. Shifting from analysis of their tactics and rhetoric to the contexts that foster NSMs, we find them strongly linked to distinct local contexts—urbane, self-expressive scenes in dense, lower rent settings, with many nonwhite and educated residents. Walkability is also a major NSM catalyst, as stressed by Jane Jacobs, along with concentrations of artists. Outside these settings, despite their universalist and cosmopolitan agendas, NSM organizations are less often present.

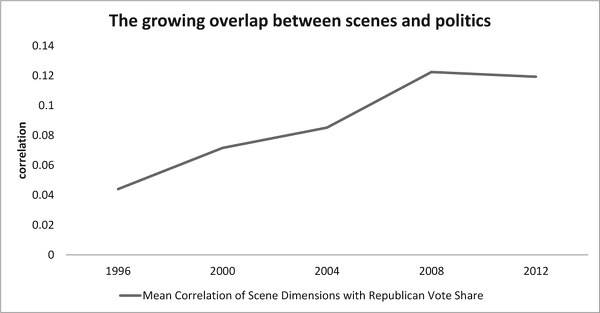

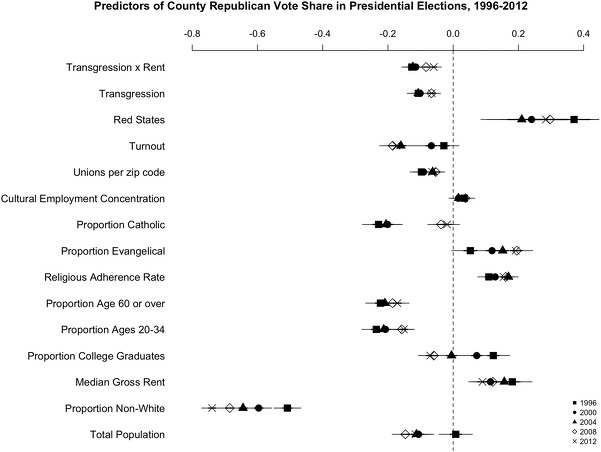

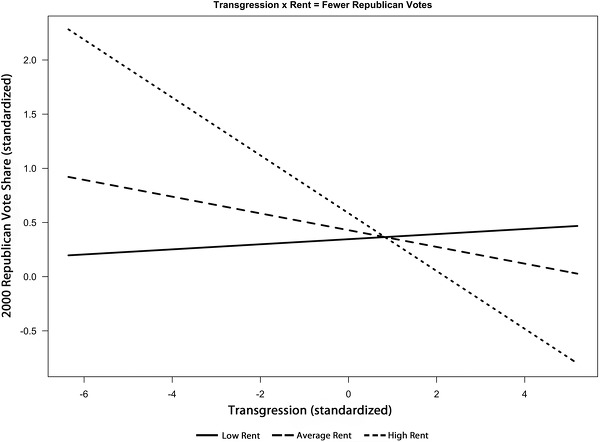

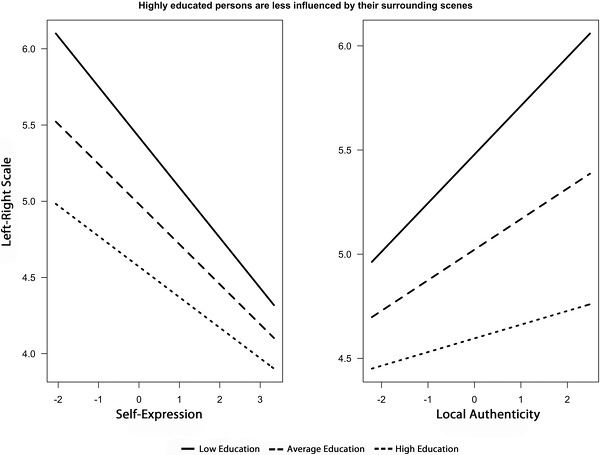

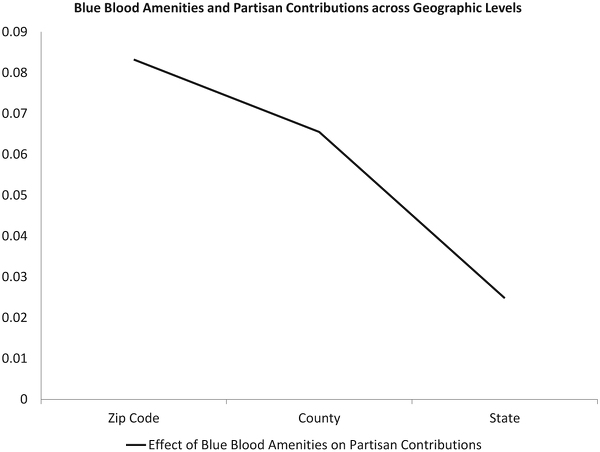

In the fourth section, we shift to national politics. Context is again the keynote here, as we show how presidential voting patterns shift with their scenic context. From 1996 to 2012, Democratic votes were correlated with more urbane dimensions like transgression and self-expression; Republican votes, with more communitarian dimensions, like neighborliness and tradition. The strength of these correlations increased threefold in this short period. The character of the scene became an increasingly reliable indicator of presidential voting. Scenes also shift other political variables. For instance, high rent counties generally vote Republican, but in more transgressive scenes they vote more Democratic—an instance of the “Bohemian bourgeois” or “Bobo” pattern identified by New York Times columnist David Brooks. Turning to Canada, we show how individuals’ political attitudes shift along with their surrounding scenes. Finally, we analyze financial contributions to presidential candidates (in 2000). We construct a “Blue Blood” index of amenities—golf clubs, yacht clubs, private tennis courts, and the like—to illustrate how scenes track zip code contributions, even sometimes in contrast to surrounding counties and states.

What emerges is a complex and wide-ranging account of America’s political cultural fault lines. Joining multiple intellectual traditions while moving from case studies to national statistics, we show how scenes are deeply embedded in our local and national politics. And we provide tools and concepts for understanding how and why this is so.

The Rise of Culture and the Transformation of Urban Politics

In the concluding paragraphs of The Economy of Cities, Jane Jacobs left her readers with a fanciful piece of science fiction on what she considered “one of the most pressing and least regarded” problems facing cities:

I am not one who believes that flying saucers carry creatures from other solar systems who poke curiously into our earthly affairs. But if such beings were to arrive, with their marvelously advanced contrivances, we may be sure we would be agog to learn how their technology worked. The important question, however, would be something quite different: What kinds of governments had they invented which had succeeded in keeping open the opportunities for economic and technological development instead of closing them off? Without helpful advice from outer space, this remains one of the most pressing and least regarded problems. (Jacobs 1970, 235)

Jacobs’s book barely touched on politics. Instead, she focused on urban economics, arguing that (1) development in general is driven by cities more than the countryside and (2) urban development is driven by innovation more than efficiency. She elaborated these points in rich and detailed ways later popularized and expanded by her followers such as Edward Glaeser and Richard Florida. But she could not even begin to imagine the potential forms of urban politics that would foster what would later be called “creative cities.” Such governments in her mind could only be the stuff of science fiction.

Writing in the late 1960s, Jacobs can be excused for this failure of imagination. Contemporary urban theorists—Jacobs’s followers and others—cannot. The social world has changed since then. Since then, participation in creative activities has increased in general, and especially for middle- and low-status persons, with the strongest growth in the United States, Canada, and Northern Europe (detailed in table 6.1 below). “The creative city” concept features high on political agendas of cities worldwide. Scenes of all sorts, as we have seen, drive local economies and channel residential patterns. The styles of political leaders and urban governance have in some cities dramatically changed, adding new cultural and aesthetic sensitivity to their past repertoires. In addition to the classical conflicts around crime, clean streets, race, and class, neighborhood controversies revolve around the right mix of amenities that captures the local “spirit” and provides the qualitative experiences (some) citizens value. Scenes accordingly become a topic of political contestation and a source of political authority.

| Table 6.1. The rise of culture: Membership in culture-related organizations, World Values Survey |

|---|

Note: Data are from the World Values Survey. Surveys are of national samples of citizens in each country, about 1,500 per country, 3,525 in the United States. The three columns for each year show the percentage of citizens who replied that they participated in cultural and related activities. Change is the difference in percentage from the first to last year. Question A066: “Please look carefully at the following list of voluntary organizations and activities and say . . . which if any do you belong to? Education, Arts, Music or Cultural Activities.” To assess measurement error due to including education, we recomputed the results for parents and nonparents of school-age children. There were minimal differences. Darker shades indicate higher values.

Les Frigos is a dramatic case, near legendary in certain European circles. The process, however, is global, reaching from Paris, Berlin, and New York to Beijing, Bogotà, and Toronto. At least three major trends are driving this global process. Each heightens the others. Earlier chapters have touched on these trends already; reviewing and explicitly joining them here helps highlight how they combine to bring scenes more squarely into the political playing field.

The rise of arts and culture among citizens. Though Robert Putnam’s (2000) Bowling Alone sparked discussion and controversy with the finding that American participation in civic associations has declined since the 1950s, he failed to detail changes in specific types of activities. There may be fewer bowling and Kiwanis Clubs, but other types of belonging are in fact gaining salience. Indeed, as shown in table 6.1, there is overall growth between 1981 and 2000 in cultural organization membership (like museums) by citizens in 27 out of 35 countries surveyed by the World Values Survey (only 35 include over-time data by organizational type). Growth is strongest in the Netherlands, Scandinavia, the United States, and Canada, where membership in cultural organizations rose over 10 percent and was much higher among younger persons. Figure 1.2 in chapter 1 illustrated the dramatic scale of this process in the particular case of Canada, with steep rises in musical groups, dance companies, independent artists, and performing arts establishments, along with sports facilities and clubs. Chapter 1 (figure 1.3) also showed the steady growth of arts and entertainment as a share of the total US workforce, even through the Great Recession of 2008. This sort of ongoing transformation suggests a potentially major breakthrough of expressive culture and personal creativity into the populace at large.

This “rise of the arts” is also evident in other arenas: household spending on culture, the size of cultural industries, the growth of cultural employment, and government spending. The movement is uneven across localities and not always linear within them yet still large and cross-national.1

Rediscovery of the urbane. If the mid to late twentieth century was an era of suburbanization, the early twenty-first century is rediscovering and reclaiming the urbanity of central cities. Internationally there has been a general rise since the 1980s in young, affluent college graduates and retirees moving into cities and especially their downtown cores, sparking urban cultural tourism and stressing day-to-day urbanist issues such as walking, street life, adaptive reuse, and gardening (from the Paris Plage to the Times Square pedestrian zone to Toronto’s Evergreen Brick Works). These new urbanist sensibilities are supported by globally oriented city governments vying for creative residents, tourists, and financial capital (e.g., CEOs for Cities).2

Why is this “rediscovery” occurring? Urban analysts have mapped components of the change yet not formulated a clear interpretation. Gyourko, Mayer, and Sinai (2006), for instance, show that the rise of downtown real estate values and rent in the largest US “superstar” cities is much faster than the national average. Analogously, Cortright and Mayer (2001) presents data for all US metro areas on the dramatic increase of young persons in downtowns. But these authors do not explain why; they stay close to standard census data. Richard Florida’s interpretation stresses preferences of a creative class for tolerant and dynamic cities. Edward Glaeser highlights increases in idea generation that arise from dense concentrations and thick networks of skilled persons. On his account, the rediscovery of the urbane is occurring because idea production has become more economically significant with the decline of manufacturing and the rise of knowledge work. Saskia Sassen suggests the importance of personal relations among global actors who prefer downtowns, and identifies producer services and the globalization of capital as drivers. David Harvey stresses a shift from managerialism to entrepreneurialism in local governance caused by heightened interurban competition, leading cities to pursue intensive development strategies often oriented less toward local service provision and more toward cultural image and place making on the global stage (Harvey 1989; Brenner and Theodore 2005).

In chapter 5 we discussed how the attractive power of scenes shifts for different subpopulations. Scenes provide cues about the character of a place, which some people find welcoming and others find alien and strange, sorting themselves accordingly. Whatever the precise cause, however, cities themselves have been transformed in the process. Their aesthetic and cultural characteristics have become not so much givens, “just there,” but projects, ideals at issue for citizens and leaders alike. And this means they can be contested.

Rise of a new political culture. This is documented by Clark and Hoffmann-Martinot (1998), Clark (2004), and others. Forms of political activism and legitimation are changing. Lifestyle and social issues have been rising in salience relative to party loyalty, class, and material concerns. Fiscal conservatism is increasingly joined with social liberalism; new forms of participation and legitimacy have emerged, driven less by classic class and primordial group characteristics and more by other forms of political identification and mobilization rooted in different answers to the question of what “quality of life” means—fast cars, big houses, tight communities, personal experimentation, natural beauty, individual freedom, amusement parks, physical fitness, open spaces, dense walkability, big-time sports, and much more. Ramirez, Navarro, and Clark (2008) provide a detailed review of the literature in their study of hundreds of North American and European local governments, documenting a striking degree of support by citizens for social and lifestyle issues as well as for new forms of political activism outside of traditional parties.

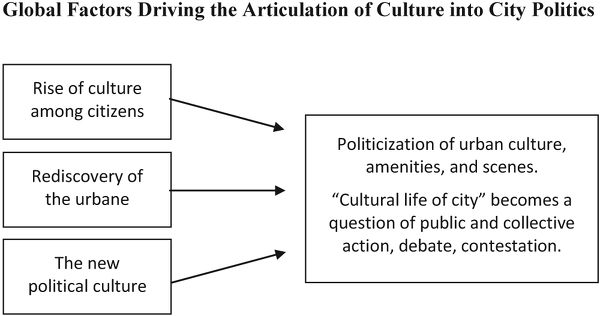

Our present concern is not to assess the causes or nature of these processes but to highlight their political salience. Typically, they are treated in isolation, or only two out of three are combined.3 However, all three processes generate increasing salience for scenes in neighborhood- and city-level decisions, coalitions, and controversies. Figure 6.2 illustrates their joint operation.

These three factors—the rise of arts and culture, the rediscovery of the urbane, and the rise of a new political culture—join to link culture to local politics through a number of mechanisms. The rise of culture gives generalized importance to expressive concerns across the citizenry—what kind of a person am I? How is this expressed in film, music, clothes, and comportment? What sorts of social audiences are in a position to appreciate and share such expressive performances of self? The goals or functional purposes of products are complemented by their design, their appeal to the personality and meanings valued by consumers, as we articulated in chapter 1.

The rediscovery of the urbane joins quality of life to quality of place. This motivates considerations about what kind of place, neighborhood, or city enables one to pursue a life deemed worthy, interesting, beautiful, or authentic. Scenes become fixtures in the urban landscape and more salient in decisions about where to live and work. These expressive dynamics are enhanced by global processes including the spread of the Internet, wider interurban competition, and increasing geographic mobility, spurring deeper searches for meaning and identity as every city and neighborhood can be compared and evaluated against everywhere else (Sassen 1994; Harvey 1989). Thus “cultural branding” and place identity become increasingly crucial and contested issues among civic leaders and ordinary citizens.

The new political culture redefines these issues of quality, culture, and place in political terms, by emphasizing how nascent leaders and social movements champion specific lifestyle issues and consumption concerns. New questions gain political and policy traction, such as how to create attractive and vibrant scenes that offer amenities (parks, music venues, bike paths, etc.) supportive of citizens’ quality of life demands; how to use these amenities and scenes as levers for economic growth, community development, and social welfare concerns; and how, for elected officials and movement leaders, to mobilize citizens’ emotional allegiance to particular types of scenes for electoral advantage and other policy goals. These three factors have combined in many cities where political and civic leaders create a new vanguard reshaping cities in a more culturally expressive direction (cf. Pasotti 2009; Lees 2003; N. Smith 2002). In the process, scenes become political opportunities for ambitious leaders and objects of contestation among citizens.4

Scenes Politics as Resource Interchange, Boundary Work, and Symbolic Inflation Management

The rise of citizen interest in the arts, combined with the aesthetics of some scenes, adds new elements to politics. We first elaborate a new political resource we call buzz, next we analyze buzz in a Toronto arts neighborhood, and then we consider new social movements and their dynamics.

Classic political resources like money and votes can acquire new import in the hands of active supporters of scenes. In assessing how and why, here as in earlier chapters, we join scene concepts with more established processes to examine how scenes “feed into” other domains. For instance, chapter 4 investigated links between scenes and economic growth, and chapter 5 showed connections between scenes and residential communities. Such “feeding in,” however, does not occur automatically, without controversy, rhetoric, negotiation, pressure, coalition building, and authority—without, in a word, politics. In the process, the excitement and energy projected by the scene—its buzz—becomes a valuable resource that may affect and redefine other valuable resources, such as money, political support, and votes.

“Buzz” refers to the symbols and signals circulating around a scene, the message that something is happening here. Such symbols can be extremely valuable, drawing investment, attention, visitors, migrants, and more. Yet buzz is often produced and spread by cultural actors such as artists who have (relatively) small amounts of other resources like money, political office, or local trust. Accordingly, as the value of buzz has generally increased, conflicts over controlling its production, distribution, and consumption are reshaping city politics, giving new groups access to power and creating potential coalitions between them and older institutional actors.

One avenue through which buzz can become a source of influence is by exchanging it for other resources. For instance, a developer is in the business of extracting economic value from new buildings. This endeavor is not intrinsically aesthetic or cultural, but it can be (1) enhanced if the buzz of the surrounding scene attracts attention and investment, (2) stymied or authorized by political regulations, and (3) legitimated or delegitimated by local residents. Here, scenic buzz, political power, and community influence are inputs into a mainly economic process for the developer. Yet from the perspective of scene participants, the developer’s cash and the politician’s authority may be assessed and engaged in terms of whether they help the scene to enhance the experiences that it cultivates—heighten its glamour, sharpen its self-expressiveness, deepen its local authenticity, renew its ethnic authenticity. Similarly, if political support for politicians depends on meeting citizens’ quality of life demands, and lively scenes provide quality urban living, then buzzing scenes become key inputs for the exercise and maintenance of political power. Further, if a scene enhances neighborhood trust (such as by providing public venues for shared experiences), then local neighborhood leaders, who depend on that trust to wield their influence, will depend on cultivating the artists, cultural groups, and diverse amenities that generate the scene. At the same time, support from influential neighborhood leaders can enhance solidarity among residents who are in turn more likely to treat the scene’s buzz as a neighborhood asset.

Still, since scene activists (artists or otherwise), however defined, are normally small minorities of even aesthetically minded neighborhoods, how they interface with other political logics is essential to assess. The capacity for aesthetic talents—dramatic flair, vivid drawing, poetic speaking, seductive music, sleek design—to enhance “normal” political resources like money makes buzz a potent resource in its own right. The impacts of such aesthetic talents are further enhanced as politics can potentially engage citizens via smartphones, social media, and visual excitement to degrees unimagined just a few decades back. If this is obvious in North American cities, it was also apparent in the Arab Spring uprisings from 2010 onward. Even in Egypt and Syria, villages and political groups competed over the attractiveness of their posters, slogans, and parades, as they sought to engage ambivalent citizens.

These examples illustrate a key point from the resource approach to politics: most citizens spend a tiny portion of their total resources on politics; there is huge “political slack” most everywhere. Winning often means increasing turnout, even just a little bit, not necessarily changing people’s minds. Traditional enticements are cash, patronage jobs, Christmas chickens, and similar material incentives; but as these have been declared immoral and corrupt resources from Chicago to China, activists have sought alternative resources. Enter buzz. Used effectively, the emotional engagement generated by artists and other experts in the ways of buzz encourages average citizens to spend time and money to energize the scene and build a political base for its supporters.

Social interchange does not mean agreement. There is constant opportunity for political struggle, coalition, and creative reinterpretation of business, aesthetic, neighborhood, and political practice. For instance, a community leader who seeks to build trust among neighbors through a public festival stakes her influence on the scene engaging rather than enraging local residents’ sensibilities. Aesthetic disagreements about amenities and culture become intertwined with disagreements about the nature of the community. Political leaders who seek to win elections and mobilize citizen action through local cultural policies stake their political power on the scene enriching citizens’ lives. They must deliver the cultural goods, and failure to do so can be politically damaging. For their part, activists who grow scenes by using buzz to attract money, political clout, and residential community support stake the scene’s ongoing vitality on attracting wealth, power, and local trust. They may thus face charges of co-optation, selling out, and domestication. And conversely, amid rising rents, increasing property values, and new developments, scenes may need to deliver some return on their buzz in the form of financial subsidies, political backing, and residential solidarity to keep the scene solvent and anchored in terms of its characteristic experiences and practices (shining glamorously, transgressing boldly, expressing oneself improvisationally, etc.)

Scenes transform other political dynamics that can be thought of in resource terms. Scene buzz may become “inflated,” decreasing its reliability as a signal of the scene’s experiences. That is, as a scene’s buzz expands and draws more enthusiasts, more people may display external symbols of the scene without a corresponding deep personal commitment. This can reach a point at which possessing formerly clear symbols (T-shirts, music tracks, certain magazines, certain interior décor) may become fuzzier indicators of a person’s engagement in the fundamental emotions and practices that “back” the scene’s buzz, diluting its symbolic potency and expressive energy. Inflated buzz becomes symbolic sizzle without the emotional steak of the scene, akin to a hundred-dollar bill that cannot buy a cup of coffee.

Similarly, the volume of buzz in circulation may be affected by its “interest rates.” Some scenes may exhibit expansionary policies, to extend buzz far and wide with few strings attached (as in “low commitment” pop music or club districts). Others may set high borrowing costs and expand buzz less (as in Goth or heavy metal music, or perhaps fraternal social clubs that require intense commitment to adopt their symbols). Low interest rates in buzz may attract considerable investment in a scene (in monetary and other forms), as many people may decide to give it a try. This can lead to rapid growth but also to unsustainable inflation. High buzz interest rates may drive up the price of participation, making the scene more exclusive (and the rent higher), as in scenes that place limits on expansion to preserve their authenticity, via political zoning or informal mechanisms.

Zukin’s (1989, 2010) discussions of political-economic dilemmas around the desire to preserve authenticity of places like New York City’s Lower East Side is one recent case in point. Authenticity politics generally become more heated in conjunction with buzz inflation, deflation, and other substantial shifts uncoupling the more symbolic from the material practices of the scene. The risk of being labeled “inauthentic” rises if political leaders and others visibly change enduring and deeply embedded dimensions of a scene. We further explore such issues for policy making in chapter 7.

More generally, many city officials have responded to the processes listed in figure 6.2 by crafting policies designed to use their local amenities and scenes as levers for bringing tourists, new businesses, and residents. Archetypical examples are the renovated railroad station with “authentic” stone and steel framing a chic restaurant/bar or housing community arts groups and farmers’ markets (cf. Zukin 1989). At the same time, those who provide key inputs into the production of a buzzing scene may threaten to withhold their services and cut the supply and quality of buzz for a given place. These could include artists, photographers, writers, promoters, designers, and performers, among others. Insofar as the profitability of an area’s businesses, the social cohesion among its residents, and the election of its politicians depend on that buzz continuing, this withdrawal could be a major threat. If presented as such, it would become a buzz strike.5

These sorts of volatile and conflicting negotiations of key scenes resources are more common with rapid growth, inflation, and deflation. These may lead local scenes participants and visitors to raise doubts about the scene’s continuing solvency, and further possible controversy or out-migration. The concern that artists and their friends are just gentrifiers can be invoked. Some places have generated buzz inflation by encouraging rapidly growing tourist and club districts that may come to dominate the locals; fearing this, others have pursued “sustainable” growth in buzz, restricting restaurant and liquor licenses to more slowly integrate an emerging scene into existing residential neighborhoods and industrial areas. These sorts of policy decisions embedded with scenes dynamics, we suggest, offer a critical piece of the interpretation omitted by the more narrowly descriptive studies of rent or migration by Gyourko, Mayer, and Sinai and Cortright and Mayer cited above.

Such interchanges, boundary work, inflationary cycles, and policy decisions create new political opportunities and new problems for policy makers to address. Such processes vary considerably across contexts. It can help to clarify some local cases by considering how they link to broader propositions about scenes and the political dynamics of their buzz.

• Where local politics is more tightly coupled with national politics, participants are more likely to support cultural organizations and amenities capable of creating buzz that extends nationally or internationally. But there is often a potential conflict between distant priorities and local authenticity, which scenes participants must struggle to resolve.

• When themes like egalitarianism and anticorporatism are shared across multiple scenes, they are more likely to grow into a broader social movement. Conversely, individual self-expression may stress uniqueness and discourage engagement with collective political issues. Scenes that stress creative individuality can thus conflict with the political logic of “compromise and join others on common issues.”

• Certain scene participants such as artists, writers, or media professionals with distinctive buzz-generating resources may be sought out by others who lack these resources.

• In conflicts among residents about integrating a scene (especially a new scene) into their neighborhood, the moral contribution of local artists’ buzz to the local community (e.g., building versus undermining trust) can become an important political controversy. Political controversies can be mapped and negotiated in terms of the 15 separate scenes dimensions. If new activists and others seeking compromise look for common ground as well as areas of conflict across the 15 dimensions, they may be able to reduce the perceived public policy distance between new and old.

• In conflicts over cultural developments’ impacts on the local scene (e.g., building a new museum), residents may be concerned about impacts of heightened buzz on traditional and local neighborhood issues (e.g., traffic and home prices) while arts management professionals (curators, museum directors, etc.) may operate from a more cosmopolitan perspective (e.g., judge local projects in reference to global icons).

• Where conflict revolves around industrial policy to subsidize local scenes, the economic consequences of area artists’ contributions to the scene’s buzz may become central political issues.

• In a patron-client political culture, political leaders will tend to resist generic cultural planning frameworks and instead support specific cultural clients separately to build scenes dependent on and loyal to them personally, rather than generalized policy resources equally accessible to all. Conflict will revolve around access to key patrons as well as movements pushing for “reform” or seeking to develop a generalized “artist class consciousness” rather than particularistic relationships.

• When historically countercultural scenes begin to cooperate with established business interests, political organizations, and residential groups, critiques may arise that the scene’s core values are being, respectively, sold out, co-opted, or domesticated. Internal controversy will revolve around the scene’s capacity to deliver its core cultural experiences and integrate new participants as it grows and becomes more interdependent with other domains.

As the rules of the game shift across political contexts, so do the impacts of resources: money talks in a business-dominant power structure, but votes count more in an egalitarian system, while the arts dazzle the more aesthetically aware. Some hypothetical examples of shifts in resource impact are listed in table 6.2 to illustrate this sort of contextualist logic.6 For instance, it suggests that money counts highly in a business-dominant political system, while buzz is low. But in other political systems in table 6.2, the rules change. These different “ideal” types overlap empirically, however, so that even within the same neighborhood people may fight over whose rules and resources should rule. This illustrates how scenes redefine legitimacy and power through transformations of general rules into specifics.

In sum, scenes are targets and resources for contemporary politics. Fights over the dimensions of the local scene—what it means to be legitimate, theatrical, or authentic, which dimensions to cultivate here and now—may become bound up with existing political cleavages like race, age, or class (e.g., black scenes versus white scenes, worker scenes versus professional scenes, youth scenes versus elderly scenes). Or they may proceed within and across such categories, generating new bedfellows and new enemies. Whatever the specifics, however, the present point is that key dynamics of contemporary politics can be better understood through attending to the power of scenes.

Toronto’s Wychwood Barns: A Case Study Illustrating the Contentious Politics of Local Scenes

We offer these propositions and hypotheses to illustrate the dynamics of several overlapping processes: resources, exchange, issue areas, inflation, buzz strikes, and so on. Many more theories could be formulated and the ones we have listed could be empirically tested. Our main concern here, however, is to suggest that the politics of scenes can be analyzed with concepts that are no more evanescent or intractable than traditional local politics issues like zoning and tax rates. The case of Toronto’s Wychwood Barns and neighborhood controversies over its buzz feature issues found globally in local conflicts involving the arts. The case illustrates how the politics of lifestyle issues in neighborhood scenes can be just as contentious as fights over money or power. And it shows how these various resources can join and do battle.7

The Wychwood Barns are former Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) streetcar repair barns. They were built in the early twentieth century near Wychwood Park, an artist colony with an Arts and Crafts aesthetic of the pristine natural landscape (Berland and Hanke 2002). By the mid-1990s, the Barns were a barely used symbol of industrial age rust in the midst of a dense, now Midtown, residential community.

In the 2000s, what to do with the empty barns became a hotly debated issue as the surrounding neighborhood changed. Amalgamating Toronto with its suburbs had left two incumbent councilors vying for one position. Local political leaders in turn became the symbolic focus of questions about what kind of community the newly created ward would be.

Thus, the victorious Joe Mihevc—a PhD in theology and social ethics, able to casually quote Freud and Jane Jacobs and recite the history of various parks movements—attracted both intense scorn and praise, with opponents chanting “Heil Mihevc” at community meetings and supporters referring to his “Zen-like calm” (Landsberg 2002). Local political leadership became key in the ensuing dispute over the Barns, as Mihevc became a major force in the movement to transform them into a cultural community center. The critical resource question for advocates of turning the Barns into an arts hub concerned presenting their case so as to mobilize citizens and civic leaders to back the project. One answer was to broaden the “arts” beyond private production and passive spectatorship to include shared consumption and active participation by citizens in festivals, art classes, community gardening, farmers’ markets, and more—into a distinctive scene. At the same time, the task was to frame the project in a manner that appealed to family- and community-minded locals.

Underlying the allure of the Barns as a vehicle for buzz creation and circulation were changes in the numbers and types of local residents. Housing values were steeply rising, new residents with young children were moving into the neighborhood, development pressure was increasing, and there were rising percentages of residents reporting “multiple ethnic origins,” working in arts, culture, and recreation, working from home, and walking to work. “Who are we?” was floating in the air.8 While traditional residential and ethnocultural bases of identity and community were in doubt or flux, an arts-oriented, expressive, urbanist, industrial heritage transformation project was ideally situated as an attractive experiment in new forms of community. This proposal stood in stark contrast to the quiet Arts and Crafts colony of its past. “What kind of park do we want?” became a proxy for “what is the nature of our community?” Without any clear or universally shared answer, these questions grew politically divisive.

What lit the fuse was the question, what is a park? Both Mihevc and his opponent campaigned for the car barns to become “100% Park,” which at the time meant “not commercial real estate development.” But when it came time to specify what “100% park” meant, the community split. Artscape—an organization that rehabilitates (and eventually would develop) buildings into arts hubs—had been attending community meetings and, together with Mihevc, began to formulate plans to adaptively reuse rather than demolish some or all of the old buildings. They would house arts groups and farmers’ markets, community nonprofits and community food centers. Local ecologists and natural preservationist groups proposed returning the area to its original natural state.

All these alternatives were plausible “parks.” Which option to pursue became the focal point of heated community meetings as residents debated the sort of scene they wanted to live near. Some residents dubbed themselves Neighbours for 100% Park and started advocating for traditional grass, trees, playground, and sports fields. Others, some tapped by Mihevc, calling themselves Friends of a New Park, organized support for considering multiple uses in general and the Artscape proposals in particular.

The formation of these small, ad hoc organizations creates publically visible organized groups that are at least symbolically collective and represent more than private self-interests. They can join neighbors and claim volunteer time, money, and media attention more easily than a set of individuals, thereby decreasing “resource slack.” They become new mobilizing platforms, which often emerge as political conflicts mount and more participants turn out for meetings, fund-raisers, and more.

The Barns thus became the central occasion for debate and collective mobilization around the type of scene appropriate for the community. Run-down and boarded-up, they symbolized the dirty work and noisy, mechanical intrusion onto what had been a pastoral scene. Turning them into grass, trees, and a children’s play area was for some citizens a welcome way to end that era, to kick the manufacturing age into the dustbin of history. “Artists need space to work, I understand that,” said a leader of Neighbours for 100% Park, film producer, and Wychwood Park resident, “but one of the things that makes city life bearable to me is a park” (Conlogue 2002).

The Artscape proposal, supported by Mihevc and Friends of a New Park, proposed an alternative, treating the industrial past as part of a collective learning process. “The Green Barn will be the meeting place of culture and nature. . . . The community can explore nature while framed by the historical architecture and heritage of the TTC car barns” (Friends 2010). Yes, humans had harmed nature, but we can now work with her rather than on her while attempting to make work fulfilling rather than alienating—ideals that might, they proposed, be promoted by videos of aboriginal ritual dances and realized in food education centers, farmers’ markets, and self-expressing postindustrial artists working within an industrial heritage building, surrounded by photographs of streetcar mechanics.

The potential impact of this emerging scene on community solidarity was also controversial. Friends of a New Park proposed a conception of community based not on privacy but on publicity, interaction, and personal self-expression. The Barns would create a “dynamic and flexible” space for a community whose identity was in flux. “A key aspect of any sustainable project is that it be adaptable and flexible to changing conditions” (Friends 2010). Neighbours for 100% Park, by contrast, had a vision defined primarily by residence; the park was for those who lived nearby, an extension of their backyards. They brought bags of lard to community meetings to graphically show all the fat their kids would fail to burn without ample space. The buzz generated by artists living and working in the park would bring nonresidents and set up a rhetorical division between the cultivated and the uncouth. The Artscape proposal would create an “exclusive space where artists can interface with thespians and activists. Neighbours may intrude if they dare” (Neighbours 2010). The result would be the “Habourfronting” of the neighborhood. That is, the neighborhood would be transformed into a tourist destination, where “the various venues, gallery openings, theatre performances, non-profit activism, food depot transactions & dare we whisper it, the prospect of booze cans . . . promise . . . a very busy venue, hardly in keeping with the quiet residential character of the neighbourhood” (ibid.). A beacon for outsiders and unknowns, the new scene, according to this view, would be less a space for diverse openness and more the occasion for new divisions supported by government largesse: “Can we spell taxpayer subsidised: G-A-T-E-D C-O-M-M-U-N-I-T-Y” (ibid.). These competing visions gave “whose rules rule?” political urgency.

If Friends of a New Park were “dreamy” buzz inflators to their critics, Neighbours for 100% Park erred toward buzz deflation. Neighbours for 100% Park were largely anonymous, rarely granted interviews, and mostly presented themselves as defending private goods rather than building public space. Perhaps the most important media moment for Neighbours for 100% Park was when one member was reported as saying “she doesn’t want anything new to be built nearby because guests at her friend’s dinner party won’t have any place to park” (Barber 2002). Neighbours for 100% Park were framed as fearful of change and outsiders, defending private turf and semiprivate goods.

Friends of a New Park, by contrast, were able to reverse the image of artists as outsiders and deviant elites, while reframing them as upstanding neighbors and public goods. To do so, they used their skills to build professional-looking websites with a clean design, took residents on inspirational walks around the Barns, distributed posters, and held participatory design discussions. They even produced a video connecting the future of the Barns to urban problems writ large (blight, lack of public services), conjuring the history and beauty of the structure (comparing the internal lighting to a cathedral’s), stressing their group’s diverse base of supporters (artists, teachers, performers, environmentalists, landscape designers, urban agriculturalists, and more), and offering images of the sorts of activities (singing, dancing, learning) that would make the Barns exist not only for “pastimes” but for “creating time,” not a passive park but an occasion for a “higher caliber of existence.”

To build local trust, Friends of a New Park sought support from key civic groups. They gathered dozens of letters of support from local school principals. Their website included hundreds of names of local residents, with addresses proudly displayed. They publically argued that a buzzing scene could build community just as well as grass and trees could. More activity would mean more “eyes on the street” and a safer environment. Far from bringing deviants and hedonists into the area, resident artists would provide theater classes, painting classes, and more. They asserted in their video, moreover, that the arts add value that money alone could not. “What makes a city great is not the stockbrokers. We need the money, but we need the art more.” These efforts linked the potential buzz from the scenes that would grow up around the artistic use of the Barns to more open and diverse policies that credited the concerns of a traditional residential community, like trust, safety, and schools, while asserting the independent value of active aesthetic participation in a scene.

In the end, the promise of added buzz and its skillful deployment by activists yielded tangible results.9 Dubbed the Artscape Wychwood Barns, the dilapidated repair yards were rehabilitated, at a price tag of around 20 million Canadian dollars, with funds coming from a variety of sources such as development fees for nearby condominium proposals, provincial and federal grants for subsidized low-income housing (on the novel proposition that below-rent artist space could be eligible for such funds), foundation and private donations, and loans backed by the city, not to mention tax exemptions. They now house several artists and arts groups, various music education programs, a children’s theater, environmental organizations, a community food organization dedicated to social justice, an ongoing slate of festivals and events, and much more. At the year-round weekly farmers’ market, Mihevc is a regular, shaking hands and greeting voters. If the prospect of this sort of scene was able to mobilize resources and forge coalitions, its buzzing reality now feeds into new development, artistic creation, ongoing community gatherings, local business, and political allegiance to the leaders able to take credit for them.

Scenes and New Social Movements

The work of the Wychwood Barns and Les Frigos activists points toward an important, and potentially generalizable, insight implicit in our contextualist approach to politics: that there is an affinity between (1) certain types of political organizations (e.g., environmental groups, social justice advocates, human rights champions) and (2) certain sorts of scenes (e.g., those that support values such as creativity, experimentation, and cosmopolitanism). The success of the first, often termed new social movements (NSMs), may thus depend on their location amid the second.

A brief sketch of the rise of the NSMs suggests not only a general linkage between their politics and their aesthetics, but some specific propositions about the scenes where NSMs should thrive. Testing these propositions using our scenes measures and national comparative data allows us to go beyond the particularities of one or two cases and ask what factors in general favor NSM organizations. This broader analysis gives a window onto how scenes structure the local political landscape, and illustrates the more general sort of contribution that scenes data and concepts can make to understanding the sources of political activism.

The NSMs sought a new relationship to nature, to one’s body, to the opposite sex, to work, and to consumption.10 In so doing, consumption and lifestyle issues were joined with the classic production and workplace concerns championed by unions and parties dominating much of politics in Western Europe and the United States over the twentieth century. Yet even in the 1940s, some political analysts (such as Paul Lazarsfeld) commented that American politics was more like a conversation about what clothes to buy or what music to listen to than obeying a military commander or union boss.11 Lazarsfeld saw these aspects of politics clearly after migrating to the United States from Austria, but this insight later led to a new framing of politics; it was a big step toward scenes.

These new civic groups stressed new agendas—ecology, feminism, peace, gay rights—that the older political parties ignored. Over time, other, more humanistic and aesthetic concerns also arose: suburban sprawl, sports stadiums, urban gardening, museums, walkability, and more. In Europe, the state and political parties were the hierarchical “Establishment” opposed by the NSMs. In the United States, local business and political elites were more often the target.12 Many governments were seen as closed to these citizen activists. For instance, in the 1970s in Italy, even Communist and Socialist parties rejected NSM concerns.

Establishment opposition of this sort encouraged the organization of NSMs and (especially in the founding years) their confrontational tactics. But as some political parties and governments embraced the new social issues, the political opportunity space in which NSMs were operating drastically shifted. Movement leaders then broke from “urban guerrilla warfare” and began participating in elections, lobbying, and advising governments. As their issues were incorporated into the political system, their demands moderated. Yet they added a heightened sensitivity to the emotional, musical, image-driven, and theatrical aspects of political life.13

In a clearly related shift, business actors such as real estate developers and political leaders and candidates often grew more green and artistic. Some refashioned concepts like loft living or self-expression into their rhetoric and policies. National political candidates like Bill Clinton made public appearances in sunglasses, playing the saxophone. In addition to the traditional ethnic music events, Chicago’s Mayor Daley II added alternative and indie music festivals to the city’s calendar. He also marched in a gay rights parade and started turning up at art galleries.

The NSMs, in other words, reshuffled the traditional relationships between class and politics. Their cosmopolitan concerns were too general to fit in any “workers’ party.” Their issue specificity was too particular to focalize an entire social class. And with many activists and supporters from educated backgrounds destined for professional occupations, unions became less potent vehicles for transforming class differences into political activism. Not only a new left but a more general new political culture emerged, in which the traditional alignment of left and right to social and fiscal liberalism began to bend.14

The influence of NSMs has been so strong that what began in the 1960s and 1970s as a radical fringe has often become mainstream. Much research on new social movements focuses on the “successful” cases, where groups are able to effectively organize and sometimes stage dramatic victories. We ourselves do this kind of research, as it permits observations of new types of tactics, rhetoric, and organization at work and the assessment of how these do or do not join with existing channels of influence.

The cost of this approach, however, is that one has difficulties determining where and why the single or few successful cases differ from the many others, where either no movements form or those that do are weak. The NSM rhetoric is often universalistic, concerned with issues like environmental degradation, human rights, personal expression, and social justice. These apply to all human beings, wherever they happen to live and whatever their background. However, these universalistic themes do not resonate universally, and they issue in significantly different styles of organization and political efficacy.

Where and why do local patterns differ? Some analysts began to stress contextual characteristics, like the local political “opportunity structure” (McAdam, McCarthy and Zald 1996). “Framing” and “organization” were also featured as key variables affecting the likelihood a social movement would flourish.

The specificity of universalism. A less abstract way to add to this focus on the context for NSM success is to lay out some characteristics of the places where they first became energized and grew. Linking scenes and social movements explicitly, Darcy Leach and Sebastian Haunss (2009) have shown how important geographic concentrations of bars, clubs, films, concerts, and parties were in energizing Germany’s “autonomous” movement. Building on the cases of Hamburg and Berlin, they develop a series of propositions about how scenes can support active movements, and how the two—scene and movement—can create tension with each other.

In the American context, the dense, high-crime, multiethnic urban centers were the key scenes of NSM activism. Here, young college graduates, artists, and intellectuals moved into ethnically diverse inner-city neighborhoods. In such places, the underinvestment and degradation of many cities was greatest, and the “white flight” to the suburbs by older and more culturally conservative persons was often most rapid. A vision of an alternative future emerged among (some of) those “left behind”: more humane, more sensitive to the consequences of human actions upon Mother Nature, able to see the beauty not only in symmetry and regularity but also in discord and disorder. Richard Sennett’s (1970) The Uses of Disorder conveys some of this general attitude.

Density alone is not enough to capture what was distinctive about these NSM incubators. To see why, consider Jane Jacobs. Her Death and Life of Great American Cities ([1961] 1992) became a call to arms for urban reformers internationally. Her ideas were inspired and refined in no small part by her experiences as an activist, struggling against urban renewal projects from the likes of Robert Moses in New York City and Fred Gardiner in Toronto, the two cities in which she spent much of her life. Moses and Gardiner proposed building huge freeways to give suburban residents quick and easy access to downtown businesses and amenities. These would cut through existing neighborhoods and, Jacobs and her followers argued, destroy what made them work. Particularly important was their walkability. People out on the streets, she argued, are more likely to bump into one another, encounter others different from themselves, avoid getting stuck in stultifying routines, and keep their eyes out for criminal activity. Car culture threatened the very basis of urban community, and with it the spirit of cosmopolitan diversity crucial to the progressive new social movements.

Just as important as walking were the arts. Artists themselves were of course often politically aligned with the NSM agenda, and they did tend to live in the sorts of neighborhoods Jacobs and others were fighting to protect and extend. But their significance goes deeper. The artist himself could be a catalyst for urban change and the agent of a new vision for what an urban neighborhood could be. Not only a scene of depravity, despair, and dirt, the city itself could become a source of beauty, an aesthetic phenomenon.

The artist, in other words, would be a vehicle for turning inner-city filth into a space for cultivating the self, a source of expression rather than anxiety. Aesthetic experience itself, that deepest and most humane of qualities, could be a human right, and the new social movements would have to create a space for all persons to develop those qualities in themselves. And insofar as this aspiration went against the types of culture and the vision of society favored by the organs of the state and the corporation, it would naturally tend to take on a more transgressive, countercultural flavor. A different world was in the making in avant-garde paintings and poetry, and it would of course be hard for the people benefiting from the current system to accept what was to come.

It was in the wake of these experiences, well before the current vogue of treating artists as urban development agents, that some of the first and most visionary urban cultural documents were formulated. And these documents carried forward themes going even further back, all the way to the first stirrings of European urbanization, as the selection from The Wealth of Nations in box 6.2 illustrates.

New Social Movements Are Typically Located in Dense, Walkable Areas with Self-Expressive Scenes and Many Artists

We can take these general observations and translate them into testable empirical claims. NSMs should thrive in dense, diverse, places where high crime coexists with college graduates and artists. They should be in urbane, self-expressive, and transgressive scenes. And NSMs should be strong where more people spend more time walking. To take on these issues empirically, we made an NSM index, which sums for every US zip code human rights groups, environmental groups, and social advocacy groups.

Table 6.3 lists the 30 zip codes with the most NSM organizations in the country (as of 2000). Naturally, many state capital and Washington, DC, neighborhoods are at the top of the charts. But it also suggests that NSM activity is driven by more than access and proximity to political leaders. The San Francisco Bay Area, for example, has five of the top 30, with zip codes of the Mission and Tenderloin districts having the highest totals. Portland’s historic Goosehollow, whose neighborhood association explicitly places walkability, parks, and cultural opportunities among its main goals (Goosehollow.org 2015), and Seattle’s dense, hip Belltown have the most NSM organizations in Oregon and Washington.

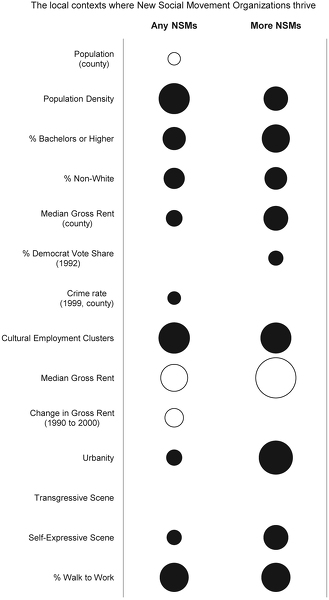

Figure 6.3 moves beyond these few dozen zip codes and evaluates the variables typically associated with NSM organizations nationally. Because most zip codes have no NSMs, we divide all US zip codes into two categories: those without NSMs and those with at least one NSM. We then ask two related but distinct questions: (1) What conditions are associated with the presence of any NSMs? And (2) given the presence of at least one NSM, what conditions are associated with the presence of many or few NSMs? The left column addresses the first question while the right column addresses the second.

This figure depicts results from what is called a hurdle model. These models are used in situations where the outcome is relatively rare but can take on multiple values (e.g., major sports teams in US counties). The purpose is to simultaneously learn something about the conditions that give rise to the presence of any NSMs and the conditions that give rise to more NSMs (e.g., any major sports teams versus five major sports teams in Chicago’s Cook County). It is not immediately clear that the same factors come into play, as our results show. Note that, due to how a hurdle model is estimated, the two columns represent two distinct submodels whose bubble sizes cannot be compared across each independent variable but can be compared within each model. Variables have been standardized to have mean equal 0 and standard deviation equal 1 at their respective levels of analysis (zip code or county). Unless otherwise noted, non-scenes variables represent zip code–level values for 1990. Cultural employment clusters and other scenes variables are identical to those used in previous chapters. N is all US zip codes. More on variables and methods of analysis is in chapter 8 and the online appendix (press.uchicago.edu/sites/scenescapes).

Where do NSMs thrive? They are usually present in high rent, high crime counties, and there are more of them in Democratic counties. Neighborhoods with any (and many) NSMs are usually in dense, lower rent zip codes with strong cultural employment concentrations, nonwhite residents, and college graduates. Moreover, walking, as Jacobs’s ideas would lead us to expect, is a crucially important element of an NSM-friendly scene.

But cultivating an openness to personal expression and a general feeling of Urbanity is important as well. Our (YP) self-expression and Urbanity measures are both strongly linked with NSM presence. Urbanity in particular is linked with not only the presence of any NSMs but also many of them.

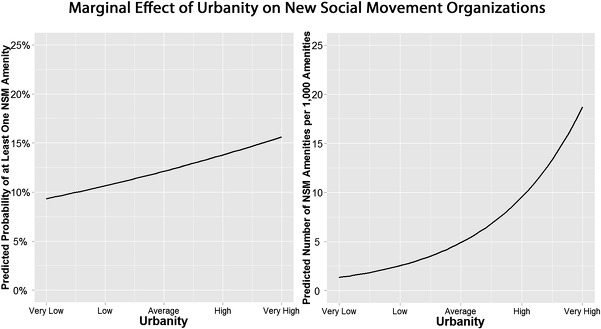

The left graphic in figure 6.4 shows, all other things equal, a moderately positive relationship between our Urbanity factor score and any NSM presence. In our model, there is a roughly 15 percent chance that there are any NSMs in the most Urbane scenes. The right graphic shows that, however, among the zip codes with at least one NSM, there are likely to be dramatically more NSMs where the sense of Urbanity is strong. Less Urbane scenes tend to have only a few NSMs (the model predicts under 2 per 1,000 amenities); average Urbane scenes have a handful (about 5 predicted per 1,000 amenities); while the most Urbane scenes have many more (18 predicted per 1,000 amenities). Urbanity, in other words, while important in NSM formation, seems to be a key driver of NSM expansion beyond our other standard variables.15

This figure shows the marginal effects of Urbanity on new social movement organizations. The figure is read left to right, where the y-axis indicates the predicted probability of having any NSMs and the predicted total number of NSMs (given that any exist) for an average US zip code (defined using the covariates listed in figure 6.3), respectively. The x-axis indicates an increase in the average Urbanity of the zip code from very low (highly Communitarian) to very high (highly Urbane).

Self-expressive, urbane, walkable, dense, diverse, low rent neighborhoods—these are indeed places that very much resemble Jane Jacobs’s Greenwich Village and Annex neighborhoods. Where these factors conjoin, they create an experience that is apparently conducive to NSM activity; elsewhere, such activity is more rare.

The Ambiguity of Transgression

One somewhat unexpected result in figure 6.3 concerns transgression. The degree to which a place has amenities that support a spirit of transgression is unrelated to whether it is home to new social movement organizations. This is the case whether we are talking about places with any NSMs or those with many NSMs.

This may seem surprising if we think of “transgression” in the revolutionary sense. But it is consistent with a strong tension within historically Bohemian culture. On the one side, there is the activist strand, which says that rejecting the present world also means reforming it economically and politically. But there has always been another side of Bohemia, one more suspicious of political activism.

This less activist strand is more concerned with transgressing norms of style and culture. Bohemians of this variety tend to retreat from public political engagement rather than attempting to overturn the existing order, much to the chagrin of anticapitalists, including Marx himself. And even when this element becomes political, it does so in a more aesthetic way. For instance, when Baudelaire commented on his participation in the 1848 revolutions, he said he did so for the rush of tearing something down and being carried away by a passion larger than himself—not to spread the rights of man. Moreover, he could and did find similar experiences in the oldest of Old Regime institutions, the Catholic Church. While it is of course only circumstantial, and we should not overinterpret a finding of statistical insignificance, this result may suggest indirect evidence of the persistence of this political ambivalence built into antiestablishment culture.16

Self-Expressive Scenes Heighten the Political Salience of Walkability

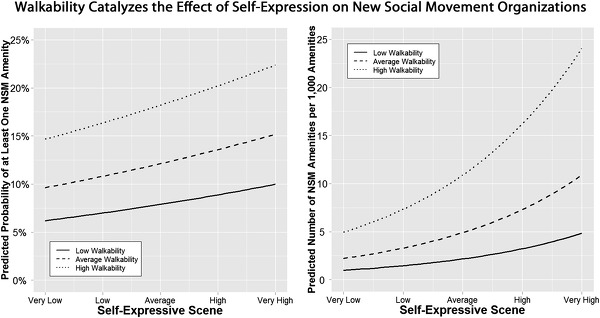

Figure 6.5 shows that walkability is one of the most widespread characteristics of neighborhoods in which NSMs are located. Zip codes whose walkability is high (i.e., one standard deviation higher than average) have in our model about 60 percent more NSMs than zip codes with average walkability, when controlling for our other variables. Ambulatory experience may indeed create a natural sensitivity to classic NSM issues like zoning, the environment, diversity, urban planning, and aesthetics.

The above analysis, however, treats walkability and the scenic features of the neighborhood (like self-expression) independently, asking how much an increase of one is associated with an increase of NSMs net of changes in the other. But, of course, they do not operate independently. One of the main aspects of movements from Jacobs on was that they should not: the urban experience itself should become an uplifting opportunity, and that means taking the time to wander through it and listen to what it says. This ethos suggests a tractable hypothesis: where this conjunction of walking and self-expression occurs, we should be more likely to find those organizations dedicated to preserving and expanding the vision of life it suggests: cosmopolitan, open, ready to learn from the experiences of chance encounters and diverse others, out to make the world more beautiful and sustainable than it currently is. That is, it is in those places where walking and self-expression come together that we would expect some of the largest current concentrations of NSM activity to be found.

Figure 6.5 shows how important this interplay between walking and self-expression can be in fostering new social movement political activity by exploring how varying each affects their joint relationship to NSMs. The left graphic shows again that, ceteris paribus, more-walkable places are in general more likely to have any NSMs than less-walkable places are. But it also shows that this difference is greater in more self-expressive scenes: in the country’s least self-expressive zip codes, the most walkable places have about an 8 percent higher predicted probability of having some NSMs than the least walkable places do. But in the country’s most self-expressive scenes, the most walkable zip codes exhibit a 13 percent higher predicted probability of having at least one NSM than do the least walkable zip codes.

This figure shows how walkability and self-expression interact to predict greater numbers of NSMs. The figure is read left to right, where the y-axis indicates the predicted probability of having any NSMs and the predicted number of NSMs (given that any exist) for an average US zip code (defined using the covariates listed in figure 6.3), respectively. The x-axis indicates an increase in the average (YP) self-expressive scene within each zip code from very low to very high.

In the right graphic, we can see that the “walkability premium” for not only any but for many NSMs is much greater in more self-expressive scenes. The difference between walkable/less walkable increases dramatically in highly self-expressive scenes. In less self-expressive scenes, a highly walkable zip code has on average about 4 more NSMs per 1,000 amenities than a less walkable zip code. But in the most self-expressive zip codes, a more walkable zip code has on average about 20 more NSMs per 1,000 amenities than a low walkability zip code.

That is, when walking and self-expression come together, the result is quite likely to be organizations advocating for human rights, social justice, and the environment.17 The one supports the other, as Jacobs held. A neighborhood with people walking about is one with an audience, one that holds opportunities to see and be seen. A scene that prizes self-expression is one that legitimizes efforts to put one’s ideas, insights, and imagination forward before others as an opportunity for experience and interaction. These sorts of places where public sociability and personal self-expression push each other to higher levels seem to cultivate the environments in which the new social movements have found energy, inspiration, members, and supporters most in tune with their aims and ambitions.

These analyses thus show just how much new social movement organizations depend on the specific character of the situations in which they work. However universal and cosmopolitan the content of NSM goals, they appear to get much of their energy and support from the qualities that inhere in concrete local contexts. Such qualities animate a distinct style of life, give it urgency and importance, but they are not found everywhere or even in many places. Dense, walkable, self-expressive, urbane, diverse, intellectual—while each of these characteristics is important separately, when they come together they provide powerful catalysts for new social movement activism to grow. But where they are weak or absent, NSM styles and goals may seem alien and unwelcome, and they may face difficulties in taking root. Jacobs-esque settings, that is, provide critical cultural meaning and emotional energy to the more abstract environmental characteristics more often featured in the NSM literature’s trinity of opportunity structure, framing, and organization. Beyond these specifics, the general point again is that certain forms of politics thrive in certain scenes but fall flat elsewhere.

Scenes and National Politics

Scenes can set the stage in which new social movement groups thrive, and define the terms in which local political controversies are engaged. But the links between scenes and politics clearly go beyond small organizations and neighborhood politics, to national party identifications, and to more general political ideologies of left and right. A simple insight as new as Aristotle, Montesquieu, Tocqueville, and Hegel tells us why this should be so: distinct morals, manners, and habits bring with them distinct sets of political ideas; as the former vary, so should the latter. As scenes manifest and crystallize different visions of the good life across localities—embedded in and affirmed by their day-to-day practices and amenities—differences in scenes should correspond to differences in their overall political orientations. A candidate, party, or policy proposal resonates in some scenes that embody some shared visions or values and falls flat in others.

As simple as it is, this general idea may not seem so visible in current political analyses, which tend to treat voters in isolation from their social contexts. Still if one considers major trends in postwar political science, some point toward a potential convergence with scenes concepts and analysis.

Politics is not an island. Professional political analysis has shifted away from a relatively narrow focus on constitutional and legal structures and the process of legislation. It now situates politics within a broader context. Only after World War II did many US academic departments of “public law” and “government” adopt the name “political science.” The change in names marked a shift to incorporate the social and cultural environment, in the work of authors like Gabriel Almond, Seymour Martin Lipset, Philip Converse, and David Easton.

Another challenge to the field was the penetration of ideas from economics, as “public” or “rational choice” models entered political science after the 1970s. While the public choice tradition had a strong individualistic cast, the processes it stressed also pushed analytical attention toward the importance of broader contexts. Thus rational choice authors (such as James Buchanan, Gordon Tullock, and Mancur Olson) introduced a range of contextualizing concepts, such as public goods and free riders. That is, rather than simply analyzing individual interests, such as supporting a public park, public choice analysts stressed incorporating interactional dynamics about how decisions are made. These new concepts led to the insight that it could be “rational” not to reveal your support for the park, but to ride free on others with a similar interest. Examining general “equilibria conditions” within which specific local policies (such as property taxes) are embedded also pushed analyses in a more contextual direction. Accordingly, the nature of rational decision making was seen to depend on the decisions of others, as developed with baroque complexity in applying game theory to politics.

Storming the bastille of elite-centric analysis. The individualistic focus of public choice authors had another surprisingly contextualizing effect. It shifted attention from princes, presidents, and party bosses to ordinary citizens. Democratic leaders depend on citizen support; such leaders ignore citizen preferences at their peril and adjust their programs to reflect those preferences. This idea was central to the writings of economists-cum-political-analysts like Kenneth Arrow and Paul Samuelson. Analogously, Anthony Downs stressed that political parties and leaders were not autonomously dominant. In a systemic context, candidates become servants of citizens by choosing popular issues for campaigns. Tocqueville was a further inspiration for authors (such as Robert Putnam) by stressing how people build “social capital” (e.g., trust). Tocqueville stressed not the strong state or the landed gentry, but small towns and their plurality of organizations, from farm associations to churches, which articulate local political cultures.18

Think small. “Context” can be large, in the grand tradition of civilizational analysis of Samuel Huntington, Schmuel Eisenstadt, or Francis Fukuyama, stressing massive entities like the West or Asia, and how these civilizational “contexts” operate.

“Context” can also lead one to think small. Small units become hugely important when we focus analytical attention on ordinary citizens and processes such as migration. As folks move around, cities and neighborhoods acquire distinct local political histories, cultures, and institutions, which can differ markedly from one another and from the larger units of which they are a part. Think about San Francisco and Austin Bohemians versus San Diego and Houston country clubs, for instance. To see these differences, we need to consider “context” as “local context.”

Daniel Elazar is perhaps the leading recent theorist of local context. He developed his account of American politics in some 50 books in which he elaborated a global interpretation of local context. Elazar’s (e.g., 1975) central idea was that America’s political subcultures trace back to the deep value commitments of the original immigrants who settled the country. In New England, the source of these values was not geography, but the theology of Calvin, carried from Swiss communes as well as Dutch and English nonconformist churches. These were “covenant societies,” whose founding documents explicitly linked the new government to God and his people. The archetype was the Ten Commandments brought down from Sinai by Moses to guide the ancient Jews. This was no contract between individuals; it was a God-given covenant that all must follow as a moralistic guide in life as well as in politics.

The New England town meeting, in requiring attendance of all adult citizens, enshrined egalitarianism among its population. Collective action was based not on majority rule by individuals but on consensual support among all through reasoned discussion and compromise. Elazar contrasts this New England political culture with the cultures of the mid-Atlantic and South. These had no covenants with God in their founding constitutions. Mid-Atlantic settlers were more individualistic and suspicious of government intervention into the free market. They favored majority rule by individuals, not consensus arising out of deliberation. The South, by contrast, was more traditionalist-hierarchical. The Southern gentleman—slave owner living in his plantation house—was the American social type closest to the European aristocrat with his “blue blood.” Government was accordingly seen more as a vehicle for securing hereditary privilege than for regulating the market or reforming the world.

Over two centuries, migration and national integration via a growing federal government and mass media have still not erased these patterns. They have been carried to cities and neighborhoods outside their original settlements. Elazar traced these migrations in microdetail, for instance, showing Scots-Irish moving from Appalachia into Southern California towns like Bakersfield, bringing their “culture of honor” with them (Nisbett and Cohen 1996). Multiple surveys and case studies still indicate such differences (e.g., Clark 2004).

Scenes and Presidential Voting Patterns

These diverse intellectual trajectories within multiple traditions of political research converge on the simple yet important idea that national voting patterns provide a window into the links between scenes and political ideology. Even within a single nation, there are many and diverse local cultures, bound up with distinct political orientations and styles of decision making. A “rational choice” differs in a traditional versus transgressive scene.19 Given its decentralized national system, moreover, such local political-cultural variation is especially salient in the United States.