5

Home, Home on the Scene

How Scenes Shape Residential Patterns

As you enter the Chicago Bronzeville neighborhood on the grand boulevard of Martin Luther King Drive, you are welcomed by the bigger-than-life statue of Soulman. Soulman is a young black man with his head high, sporting a large-brimmed hat and a suitcase tied closed with rope. His entire body seems covered with fish scales, but look more closely and they are the soles of shoes. They remind us of the many shoes worn out walking the Underground Railroad from the Deep South to Bronzeville. Soulman was a brave pioneer who escaped his slave master for the promise of freedom. The number of Soulmen courageous enough to risk the Underground Railroad was tiny, but they inspired thousands who followed in later years.

The symbolic heritage of Soulman remains strong in contemporary Bronzeville. Its thousands of new mixed-income housing units are surrounded by numerous churches, large and small, and strong memories of blues and gospel, which were pioneered here. Richard Wright read his works at the Wabash YMCA. He is one of dozens commemorated in the bronze plaques lining the sidewalks of King Drive. These scenes that grew up around Bronzeville’s historic legacy played a role at the turn of the twenty-first century, as Mary Pattillo (2008) documents in Black on the Block, in attracting many new middle-income residents who could have chosen to live elsewhere. They found a rich symbolic repository of historically potent images and aspirations, where song, sermon, solo, dance, verse, and more provide venues for critical judgment of, respite from, and creative engagement with an often harsh and hostile world.

Bronzeville of course embodies just one type of scene. The ghosts of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac still haunt Greenwich Village and Haight-Ashbury, and scenes that evoke Bohemian and Beat themes of self-expression and transgression are significant draws for young people and artists to this day. Similarly, pastoral images of the countryside, with its slow rhythms and quiet communities, often speak to older persons. Many spend their golden years of retirement “on the road,” in RVs rolling through America’s great scenes of natural beauty. Other retirees, particularly “ruppies” (retired urban professionals), may be drawn to emerging downtown scenes, with amenities like restaurants, operas, symphony halls, and parks.

Different people are drawn to different scenes. The character of the scene plays a major role in determining who lives where and therefore what shape residential communities take. To be sure, more than amenities define the opportunities and attractions that places afford to current and potential residents. Hence it is crucial to analyze multiple variables and multiple units of analysis.

Simple as this idea is, the major traditions of urban analysis have tended to propose one-factor, one-level explanations, with jobs typically taking center stage. There is a certain plausibility to this approach. Counties (or metros) generally constitute single labor markets. If finding a job is the major motivation for moving, then any neighborhood within a given labor market is, all things considered, as good as any other—jobs anywhere in the city draw people from many neighborhoods and backgrounds, according to this tradition. Hence many quantitative studies typically report large area data on economic and population change for entire counties or metro areas. Ethnographers by contrast often conduct case studies of individual neighborhoods, which generally ignore national or global patterns. And national surveys of individuals largely omit their neighborhoods.

However, if we admit that choosing a place to live involves a more wide-ranging and complex set of considerations, the analytical picture changes. In particular, residents of different neighborhoods have ready access to widely varying amenities and scenes, even within the same city. Chicago is a case in point. Just north of Bronzeville is the four-mile area around the Loop, which attracted in the 1990s more 25- to 34-year-olds and college graduates, relative to the metro area, than any other downtown in the entire United States.1 Many attribute the popularity to the four months of free or inexpensive concerts and related Loop restaurants and nightlife. Rents escalated as these young urban professionals moved in. Yet in other Chicago neighborhoods, population and rent were stable, while still others have been seriously declining, such as those near abandoned steel factories. Data for the whole county sums these many neighborhood-specific dynamics, which are lost when aggregated.

Chicago is similar to most big cities in illustrating such neighborhood-specific diversity. To capture such diversity analytically requires a more wide-ranging approach. We need to compare local communities to one another, both within and across the cities in which they are situated. And we need to incorporate jobs and income measures along with newer dimensions like glamour and self-expression and newer amenities (at least in America) like yoga and martial arts clubs. The point in doing so is not to disagree with past results so much as to show how they can be enhanced by adding scenes concepts and measures to the story. What emerges is a novel picture of why people live where they do and how residential patterns are changing.

Chapter overview. A few main types of questions guide the following analyses. A first question asks which types of scenes attract which types of people. We find links between scenes and population changes across many subgroups: young people tend to increase in transgressive scenes, baby boomers are rising where self-expression and local authenticity mix, and retirees are increasing both near natural amenities and in places rich in the arts. Moreover, Bronzeville is not alone in having a scene linked with African Americans: historically concentrated in more communitarian scenes, African Americans have been shifting somewhat away from such scenes and toward those that mix glamour and exhibitionism. Scenes matter not only to the young, educated, and the affluent, but also to middle-aged, older, and nonwhite persons.

We also ask how scenes distinguish within and transcend powerful social cleavages, like race, religion, and education. Contra the idea that artists constitute a distinct new class or homogeneous consumption group, we find that arts jobs are found in several different scenes. Similarly, we question the extent to which America is “coming apart” along a great cultural divide. There are to be sure major cultural differences across neighborhoods: the proportion of college-educated whites is relatively large in zip codes with yoga studios but small in those with evangelical churches; vice versa for nonwhites. However, some amenities bridge these differences. Popular culture (e.g., fast food, pop music, and sports) is an American lingua franca, well represented across communities with very different ethnic compositions but also in more highly educated zip codes. So are martial arts clubs, which are found near yoga studios and evangelical churches, in racially diverse and highly educated neighborhoods—openness to alternative traditions and cultures is not distinctive to any one group of Americans. What emerges is a far more crosscutting and pluralistic picture of American life than many popular accounts offer, which stress black-and-white fragmentation without showing potential commonalities and opportunities for meeting “the other” in shared pursuits and activities.

We pursue these questions and more below. But throughout, the general importance of the scene to urban development comes through loud and clear. Cities grow and change not only because they have beaches or jobs, but also because they offer distinct scenes that attract different types of people.

The New Chicago School

The Bronzeville example illustrates why it was no accident that what became known as the Chicago School of urban sociology emerged in the city of Chicago, with its distinctive focus on the neighborhood and the local context.2 Because of our own focus on local context, we have often described our scenes approach as part of a New Chicago School.3 Highlighting the local scene extends the classic Chicago School focus on shifts in lifestyle across neighborhoods. Yet it abandons the Old Chicago School nostalgia for village life and rigidity about where different types of neighborhoods should be located (e.g., in concentric circles). At the same time, the New Chicago School approach adds a much more pluralistic, crosscutting, wide-ranging, and flexible sensitivity to the cultural themes that can differentiate and link neighborhoods. To better understand how a scenes-based New Chicago School extends and diversifies the ethnic neighborhood-based Old Chicago School, it helps to first go back to the classic idea of studying the local context and then see why it is important to expand our vision from the neighborhood to the scene.

The Types of Glue That Hold a Community Together Shift by Local Context

While Marxian analyses of urban change tend to downplay local context and stress abstract forces like industrialism or capitalism, these seemingly universal processes have their own local roots. Indeed, in some of the classic eighteenth-century English factory towns, manufacturing workers from many backgrounds were thrust together in new types of neighborhoods built around a factory. All of a sudden, their residences and daily contacts were determined primarily by proximity to their place of work and their role in that workplace. They came from far and wide to live near where the jobs were, and this—the job—was the common thread in their residential life, more than, or at least alongside, their homeland, language, or ethnicity.

In extreme cases like Pullman Town (outside Chicago) or Saltaire (near Bradford, England), whole towns were planned and built around the company, and workers were expected to rearrange their lives according to the fact that they were Pullman or Saltaire workers. In Saltaire, not the cathedral but the textile mill was at the center of the village. One worker described life as a Pullman employee as follows: “We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell” (“Quote from a Pullman Laborer, 1883”).

Similar plans were developed elsewhere. George Steinmetz (1993) has shown how in late nineteenth-century Germany paternalism and ideology led the Social Democratic Party, corporate leaders, and local officials to agree to build housing for workers next to their factories. This model spread with socialism to Soviet areas and China.

But not everywhere. The link between work and residence is relative to the local context. Had Marx visited early twentieth-century Chicago, he would have seen this type of contextual relativism on the ground. Here, distinctive ethnic groups—Irish, Polish, Lithuanian, Italian, and so forth—lived not near factories but instead built and lived near their own parishes; they often worked far away from their homes. Without the national state as a focus of ethnic identity, as in European nations, the neighborhood became central. Though Chicago is more extreme, America is dotted with Greektowns, Little Italys, Chinatowns, Little Portugals, and the like.

This residential pattern—the ethnic neighborhood—reinforced ethnocultural styles through parades and food and bars and more. Saloons, church halls, and ethnic militias became the centers of social and political life, not only union halls and revolutionary cafes. Indeed, if we look to our amenities data, we find that to this day there is a strong correlation between the number of Italians who live in a given neighborhood and the number of Italian restaurants in that neighborhood, far stronger than for people of German, French, and Irish ancestry and “their” restaurants. Some new immigrants like Koreans or Jamaicans create new churches and restaurants in the same general manner.4 Even when people move away from the ethnic village, the density of shops, restaurants, churches, festivals, and the like in the old neighborhood provides a symbolic focus and a point of congregation at night and on weekends.

At the same time, when this spatial concentration of ethnic culture seems to be on the way to dilution, it can inspire feelings of anxiety and loss. Hence the Los Angeles School of Urbanism, with its claims about the fragmentary, conflictual, Nowheresville character of modern urban life, has its roots in its own distinctive neighborhood experiences: the Los Angeles of disconnected neighborhoods, large single-family homes in gated communities on sidewalk-free streets, freeway commutes, globetrotting stars, gangs, violence, and international media corporations. Even generalized claims about the schizoid character of modern life have their local bases.5

Where ethnic neighborhoods have been strong, religion, heritage, and culture have often provided more important bases of allegiance and enmity than has class. This is a legacy we saw clearly in chapter 3, documented in the number of family restaurants, parks, cemeteries, and churches in Chicago. Indeed, it is this strong linkage between residence and ethnic culture that is a central part of the answer to Werner Sombart’s classic question: Why is there no socialism in America? The (partial) answer is that in contexts like the United States in general and Chicago in particular, ethnicity and religion are often more important for politics than is class. But different contexts generate different answers, a theme to which we return in chapter 6.

The strong linkages in Chicago between neighborhood, ethnicity, religion, and culture made the typical Chicagoan into something of a cultural anthropologist. Different people have their own ways of life, their own ways of making sense of the world, which are manifested in their daily rituals, how far they stand apart, dinner table manners, home décor, leisure pursuits, and more. Chicagoans did not need to travel to the Amazon to learn this; they just walked across the park.

Marx’s intellectual disposition was to extrapolate what he saw in specific local contexts to impending global and epochal changes. Old ways of living together would be swept into the dustbin of history by the coming proletarian tide. The Chicago approach is more pluralistic and pragmatist: the strength of different types of social bonds varies in different local situations. In places where work and factories are the focus of life, jobs and class take center stage; elsewhere, other things matter more.

There Goes the Neighborhood

Scenes analysis extends this contextually sensitive neighborhood focus into a world in which not only the church and local pub but also the nightclub, the farmers’ market, the dance club, the yoga studio, and the dojo define the distinctive character of a place. This is similar to going “back to the land” as in chapter 4, while adding new and more wide-ranging cultural dimensions that affect people in more than their jobs. In chapter 4 this meant taking a more expansive view of how the character of a place influences economic growth, not only attending to physical soil or even Max Weber’s Puritan ethic. So too in this chapter: to go “back to the neighborhood,” we need a broader view of what “neighborhood culture” means to understand the energies that can make a place attractive for habitation and not only production. Hence extending the Old Chicago School neighborhood context means moving on to the New Chicago School scene.

This extension of “neighborhood” to “scene” is not an abstract claim. It has grown out of concrete local experiences, which the streets of Chicago made particularly evident. For if “you deliver your precinct, I’ll deliver mine” was the political result of Chicago’s everyday contextual relativism, it also made Chicagoans highly sensitive to new styles of life, new forms of group togetherness, making their way into their bars and restaurants. Thus it was in Chicago that a group label was forcefully applied to a new social type: the yuppie.

Given the strength of local cultural identity in Chicago, it was immediately apparent in the early 1970s that there were new characters on the scene. They stood out, for Chicagoans were always sensitive to “outsiders” in their midst. These newcomers were more likely to drink wine than beer. They engaged in strange new practices, like jogging or jazzercise. They were just as likely to be found in the yoga studio or meditation center as in the church. And so Chicagoans identified them by name—young urban professionals, yuppies—and treated them like any other ethnic group. They have their bars, and we have ours; they should live in their neighborhoods, and stay out of ours; and so on.6

The cultural transformations of Chicago under Mayor Daley II (1989–2011) were in no small measure a product of applying the central principle of old Chicago politics to this new “ethnicity.” That principle is, figure out what they want, give it to them, and remind them where it came from. Hence the bike paths, flower gardens, indie rock festivals, and postmodern architecture that grace Chicago’s neighborhoods came accompanied by signs that told you their source: “brought to you by Mayor Richard M. Daley.”7

And this is Chicago! The pork butcher to the world, the city of broad shoulders, is now more and more a city of scenes that are a complex plurality of overlapping dimensions, with hipsters and yuppies and fratboys and metrosexuals as much a part of the cultural landscape as ward bosses and Irish saloons. In Bridgeport, the classic neighborhood base of the Daley machine, international Chinese artists mingle with the underground artist children of Polish restaurateurs, “blue-collar Bobos” we might call them,8 who host exhibitions and performances in their parents’ businesses and in former warehouses.

This diversification of identities and expansion of personal expression reflects a national pattern. Indeed, we find that one of the strongest predictors of a self-expressive scene is the percentage of the population reporting multiple ancestries. Yet these “fragmented” neighborhoods are neither nothing nor nowhere; they have their own types of scenes, which can be studied alongside the classic ethnic neighborhood, and with similar tools. In fact, a major theme in some discussions of postmodernism is that there can be grounded postmodern practices that celebrate irony, boundary crossing, and mixing categories rather than fixity, closed worlds, and purity. Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” offered a classic exposition of this form of practice, extended more recently by authors like Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello (2007), who in The New Spirit of Capitalism associate playful irony with an “artistic critique” of contemporary capitalism that transforms standardized experiences into (potential) opportunities for authenticity.

Nor are the links between scene and residence exclusive to North America. Economists Oliver Falck, Michael Fritsch, and Stephan Heblich (2010) demonstrate that German cities with baroque opera houses were more likely than others to attract highly educated residents, who stimulated regional growth. They also cite a survey of about 500,000 Germans, which found that for highly educated workers “an interesting cultural scene” was among the most important factors in their location decision. Similarly, Clemente Navarro and colleagues (2012) show that scenes matter in Southern Europe as well, demonstrating that “the creative class” is highly likely to live in Spain’s “unconventional scenes.”

In sum, in the new Chicago, as in cities worldwide, the differences that make a difference in choosing between one neighborhood and another have become far more culturally subtle and wide-ranging. They go beyond but still include the traditionalism and neighborliness of the pub or parish or the formality of the opera house. Hence our 15 dimensions and their many combinations naturally come into play as crucial drivers of residential patterns.

Scenes, Amenities, and Population Change

If Chicago precinct captains saw that neighborhoods were becoming defined by the subtleties of their scenes, it has taken social scientists longer to catch on. Early voices, like Paul Lazarsfeld or Daniel Bell, who questioned the traditional sociological assumption that “variations in the behavior of persons or groups in the society are attributable to their class or other strategic position in the social structure,” (Bell 1996, 37) were mostly drowned out.9 Manuel Castells’s (1983) The City and the Grassroots marked a major shift within the post-Marxist urbanist tradition, arguing that contemporary urban social movements were oriented toward the quest for communities based on “collective consumption goods” such as public transportation, education, the arts, and culture. From a different starting point, Terry Clark and Seymour Martin Lipset’s (2001) The Breakdown of Class Politics showed that classic left-right, union-capital divisions were becoming less salient politically in many different countries, while matters of taste, consumption, and quality of life were becoming more relevant.

Clark built on this idea in subsequent volumes. The New Political Culture (1998) (coedited with V. Hoffmann-Martinot) showed that an increasing number of mayors and city councils had added lifestyle and consumption issues to the centers of their agendas: the environment, amenities, gay tolerance, neighborhood aesthetics, and the like. The City as an Entertainment Machine (2004) followed by pioneering the study of how amenities drive urban migration, using data from the yellow pages for the first time to show that counties with more built amenities (like operas and juice bars) had rising numbers of young people, while older people were increasing in counties with more natural amenities (mountains, lakes).

Even economists reported examples of amenity-driven migration. Richard Florida’s (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class popularized this emerging consensus on the power of consumption rather than only production to drive population changes, adding a distinctive focus on clusters of artists and gays, dubbed “Bohemian,” as amenities in their own right, attractive to “the creative class.” And Edward Glaeser’s work on the “consumer city” argued that population growth was now driven more by what a city offered for consumption (restaurants, theaters) rather than for production (factories, warehouses) (Glaeser, Kolko, and Saiz 2001). Florida’s strong statement was reformulated by Clark and Glaeser (see the summary in Wikipedia’s “Richard Florida” entry as well as chapters by Florida, Glaeser, and Clark in Clark [2011a, chs. 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7]).

The scope of the shift becomes apparent when we note how even leading proponents of more traditional Marxian styles of analysis have added more explicit attention to culture in their concrete writings, for example, on urban development. One case in point is Harvey Molotch. His earlier Urban Fortunes (1987) (with John Logan) on the “urban growth machine” stressed business elites as driving urban development by rigging the political system in their favor. Since then he has softened his stance, and looked to cultural allure, and not only business and power machinations, as a key force driving urban change. Thus by 2011 Molotch himself was ready to declare a strong link between “the soul and migration” and to argue that factors beyond the political-economic are at play in determining how a place becomes the place it is and whether, and in what direction, it grows.

Another source of renewed attention to local culture in sociology comes from recent efforts at the nexus of urban and cultural sociology to rethink questions about purported “cultures of poverty.” For years after the infamous Moynihan (1965) report was published, social scientists, for instance, mostly stopped writing about the African American family—it became too politically sensitive, especially to document its decline.10 Then William Julius Wilson and Orlando Patterson pioneered work in the 1990s that reintroduced the centrality of the family to interpret many aspects of black life and culture.11

The issue continues to inform much discussion about social programs, lifestyle, cultural change, and more. In the process, “culture” returned to the sociological research agenda, but not as ostensibly positive or perverse values that attach to distinct groups (e.g., “Irish values are corrupt”).12 Instead the focus is on particular settings and activities, and how they do or do not build up important skills, social contacts, knowledge, and abilities. A person who grows up and lives in a place with high crime, poverty, and few amenities and services will likely have a distinct, and understandably oppositional, attitude toward his or her broader society.

Contemporary research has thus turned to local amenities and their potential role in changing the trajectory of black neighborhoods. Schools, daycare, churches, and community centers often feature prominently. Ethnographic studies suggest that such amenities can play key roles in establishing a circuit of neighborhood relationships that encourage mutual support, information sharing, and respect.13

In this period of intellectual ferment, there have been many names for social connections based on aesthetic sensibility, like “lifestyle enclaves” or “consumption communities” or “communities of taste,” as well as for what draws such groups to particular places, like “cultural ambiance,” “place aesthetics,” or our own “scene.” They all point toward something common. The style of life that a place makes possible is a key factor in defining what makes it an attractive place to live; scenes inspire the human habitat with meaning.14 And in some cases (as box 5.6 illustrates), the sense of belonging that comes from life in a scene can rival, or at least be mentioned alongside, that which comes from the most emotionally charged of all human bonds, that of the family—not unlike how the rise of ethnicity as a source of identity in nineteenth-century Europe drew its energy from metaphors from the extended family.

Standard accounts of urban change, which typically focus more on socioeconomics and politics, tend to miss the significance of the scene in driving migration. One powerful example of how important this can be, however, comes in a recent study by sociologists Jason Kaufman and Matthew Kaliner on the different trajectories of Vermont and New Hampshire. Throughout the twentieth century, the two states have been quite similar socioeconomically, and in the beginning they did not differ substantially politically.

But through the early part of the century and especially from around the 1930s on (Kaufman and Kaliner 2011, 138), Vermont billed itself as a haven for people looking to live in close contact with nature and art in a generally relaxed tolerant environment. New Hampshire’s image, by contrast, was business friendly, tourist friendly, individualistic, with low taxes and easy access to big cities: “Live free or die” is on the state’s official license plate. Over the years, people from all over moved to the two states, often based on whether these images spoke to them. Hence Vermont shifted politically, moving from the right to the left to become the liberal stronghold it is now. New Hampshire remained more libertarian. One of Kaufman and Kaliner’s main pieces of evidence for the cultural dynamics of this shift: Vermont has far more Birkenstock stores, vegetarian restaurants, health food stores, hemp shops, and Ben and Jerry’s; New Hampshire, more Dairy Queens and Harley Davidson stores.

Home Is Where the Scene Is

All of this implies that a place with a scene that expresses the vibe, the feel, the mood, the ambiance with which you identify, with which you are simpatico, would be, all things considered, a more attractive neighborhood to live in than would one that does not. You should be more tuned into the scenes with which you resonate, and be more motivated, again all else being equal, to move or stay near one than would somebody whom the scene leaves cold, or even repulsed. Let us put this general proposition, as well as several more specific ones, to the test.

Critically Extending Past Work: Zip Codes versus Cities/States, Single Amenities versus Whole Scenes, Total versus Subpopulations, Mono- versus Multicausality

To do so, we critically extend in a number of ways much of the past work reviewed above. We have introduced most of these features of our approach before, but they are important again in the present context.

First, while most research on culture, amenities, and population change analyzes population changes at the city, county, or even state level, we start from the zip code. This analytical decision is rooted in familiar experiences. How often does one hear, “I’m moving to New York State!” or “Wisconsin, here I come!” Maybe sometimes, but generally states have less psychological relevance in most location decisions than do cities: “SF or bust!” or “Which way to Austin!” are more common slogans. Even so, there is so much variation (in scenes, education levels, racial composition, etc.) within cities (think, for instance, of Staten Island versus Manhattan), that only analyzing the city leaves us in the dark when it comes to the decision: Where, exactly, in which neighborhood, will I settle? That is, “in which Chicago neighborhoods would I be comfortable?” To tell which ones, we need to go down to smaller units.

While it remains important to include larger units, starting from the zip code allows us to assess the relative importance of small and big (from zip code up to county and state), and to ask whether, for instance, a city’s average rent, or overall job growth, affects, or even trumps, the scene-like qualities of the local area in location decisions. This is a simple point, but it differs from much research that typically investigates larger units and so is unable even to ask these sorts of questions.

Next, unlike most studies of amenities and population changes, we typically focus not on one or a few amenities but on hundreds (though we do sometimes examine smaller subsets to address specific hypotheses about key amenities). These thicker measures can be analytically critical since the overall cultural character of a place (what our scenes measures aim to capture) typically changes relatively slowly, but numerous discrete individuals and amenities move in and out. Thus, many experimental young people may move to a Greenwich Village, or Wicker Park, or Toronto’s Queen Street West for the generally self-expressive, transgressive, offbeat, and funky scene. Some stay as they age, but others move elsewhere when they have children or develop more moderate tastes, often to different scenes that combine self-expression with different dimensions, as we will see below. New young Bohemians or hipsters move in, and though particular businesses may change, these often continue the general ambiance of the scene—a body art studio opens, a tattoo parlor closes; a Thai-Mexican fusion restaurant closes, an Indian-Mexican fusion restaurant opens. The scene remains as the particular occupants change.

Yes, scenes do change and move, sometimes dramatically. The migration of New York’s alternative scenes to Brooklyn is a powerful example. But in the aggregate, they do so more slowly than do specific individuals and amenities. Scenes are ecological rather than individual-level phenomena. This is one major theoretical justification for why we typically treat scenes as independent variables and population changes as dependent variables.15

Moreover, instead of only analyzing changes in the total population of an area, we focus on subpopulations such as age groups, college and postgrads, artists, and African Americans. Simple as it is, this focus on subpopulations goes beyond much urban and community research, which looks for causes of growth or contraction in the total population. The problem with this standard approach is that it blinds us to the great diversity of processes at work behind overall population change, as many subgroups rise and fall for many different reasons. A city with relatively stagnant total population change can experience huge gains in some parts and declines in others. Or total population can be constant while the types of people in a neighborhood dramatically change. Thus it makes more sense to specify how distinct subgroups behave rather than to posit generalities about “what (all) people want,” like low taxes or warm weather.

In an ideal (analytical) world, we would be able to go beyond the relatively gross subcategories of the census, and find out not just how old somebody is or whether she graduated from college but also what kinds of books she reads and what types of restaurants she dines in, not to mention her personality. Then we could explicitly weigh the relative importance of her tastes versus her educational credentials in her location decisions. Alas, data like these, at a low-enough geographic level, if they exist at all, may be locked away in the digital vaults of the market research departments of major corporations.16

While we are therefore stuck with the census categories, we can still do a lot with them, beyond simply showing, which we do, that there are significant connections between scenes and where people in different age, ethnic, and educational groups live. Indeed, there is a reason the census divides up the population the way it does. These categories are and have been very important ways in which people define themselves and others.

At the same time, the census information can be used to show how scenes open up cracks within and build bridges across these classic divisions: by showing how, for instance, the same census groups are sometimes drawn to different scenes, how similar scenes sometimes appeal to multiple census groups, or how different combinations of scene dimensions have different impacts on the same census group. While this is all somewhat abstract right now, we elaborate below.

To do so, we return to our main Core variables, introduced in chapter 4, since they are relevant to residential as well as economic questions. Total county population is again important to account for, since many people live in and move to cities where there are already a lot of people, for all the opportunities—business, romantic, or otherwise—which that entails. We again include county rent as a proxy for general cost of living and affordability in the area. Accounting for the college graduate share of the population allows us to assess the importance of being near educated people in location decisions. Accounting for the nonwhite percentage of the local population allows us to assess the degree to which the racial composition of an area shapes where groups live and potentially moderates the impacts of scenes. Crime is clearly a major factor in location decisions, and so we again include the same crime data as in chapter 4. The rate at which a county voted for Bill Clinton in 1992 is a proxy for the area’s overall political orientation at the first time point in the analysis, which may influence which cities certain groups find hospitable or not. As in chapter 4, we include a variable for local cultural employment concentration. This variable can be interpreted as an indication both of the heightened artistic ambiance that more cultural firms and their staff can add to an area, as well as the job opportunities that such firms offer. And we again include as part of our Core model the Communitarianism/Urbanity scene measure, which allows us to ensure that any connection between a more specific scene or scene dimension is not simply a reflection of this most common American scene distinction.

To these we add two variables beyond the Core. First is the USDA’s index of natural amenities (lakes, mountains, etc.), because living close to nature may be an important consideration for many people, and natural amenities have featured prominently in past studies of amenities (Clark 2004; Zelenev 2004). Second is a measure of the county increase in total jobs, which accounts for a question we often receive in conference presentations: “Sure, the scene might be important when choosing a neighborhood, but is not the really important decision which city to live in, which is the place generating the most new jobs?”

All results we report for scenes are net of these other variables, that is, they show the strength of the connection between the scene and the census group (young people, college grads, etc.), accounting for, holding constant, or independent, of the education, rent, crime rate, density, and so on, of the local area. However, since we are concerned with scenes as one factor among many, and even as the overall character of the place in its entirety, which includes amenities and people and crime, and so forth, we also often report results for these other variables as well.

Young People Live in Scenes Where They Can Sow Their Wild Oats

A first set of questions about how scenes shape residential communities concerns the links between scenes and specific subpopulations: In which types of scenes do which types of people live? We start with age groups: young people (18–24, 25–34), baby boomers (born between 1945 and 1965), and retirees (i.e., persons 65 or older). Why age? For a number of reasons.

For one thing, especially since Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class, many cities, officials, and researchers have been interested in the question of what attracts young people to a given place. The general idea is that with their youth they bring energy, vitality, openness to and tolerance of new ideas, and a kind of comfort with the growing diversity that increasingly characterizes American life. And they are often net contributors to the tax base. Some researchers even speak of the “youthification” of many urban areas (Moos 2014). We qualify this image below.

For another, whatever baby boomers touch, they change. Wherever they go, they come in numbers, often with large and open wallets, at least in the aggregate. But of course, there is much more to the boomer generation than size. Not least is the fact that the boomers have been in many ways pioneers of consumption (from the Beatles to the hula hoop), and it is unlikely that their interest in such things would disappear with age.

Third, retirees are growing as a segment of the population. It stands to reason that, at least for many of them, where to live is an open question, whether downtown near the opera or in the quiet countryside. And while much of the academic literature focuses on youth, retirees bring much free time, willingness to volunteer, and often a fair amount of discretionary income to wherever they settle. They are no longer job-bound, though their families matter. So detailing what attracts them is important as well to understand how and why communities are changing.

In what types of places do these age groups tend to live, and where are their numbers changing? Look at figure 5.2 to find out, which shows the associations of self-expression, transgression, and their combination with young people and baby boomers both in terms of their zip code population shares in 1990 and in terms of the difference between their 1990 and 2000 percentages of the population (we return to retirees below).17

Figure 5.2

This figure shows the impact of (YP) self-expression and transgression performance scores, as well as their interaction term, on six outcomes: (1) percentages of zip code residents 18–24, 25–34, and baby boomers (1990); (2) differences in the percentages of these same groups between 1990 and 2000. Black circles indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) positive associations while hollow circles indicate statistically significant negative associations. Circle sizes are proportional to the magnitudes of coefficients from a multilevel model, where zip codes are the level 1 units of analysis and counties are level 2. In addition to these three scene variables, the full model includes the Core: county population, rent, party voting, and crime rate; zip code percentage college graduates; percentage nonwhite; cultural employment concentration; and our factor score measure of Communitarianism/Urbanity. Analyses in this chapter add to the Core: change in total jobs (1994–2001) and natural amenities. All analyses of change variables as outcomes include the corresponding level in the model (e.g., 1990 level of 25- to 34-year-olds for change in 25- to 34-year-olds, etc.). N is all US zip codes. More on variables and methods of analysis is in chapter 8 and the online appendix (press.uchicago.edu/sites/scenescapes).

Figure 5.2 contrasts the three age groups’ relations to the two scene dimensions. In 1990, both 18- to 24-year-olds and 25- to 34-year-olds composed, somewhat surprisingly, below average percentages of the population in the country’s more self-expressive scenes (net of the other variables in the model). Population shares of 18- to 24-year-olds were typically higher in more transgressive scenes, while the 1990 level of 25- to 34-year-olds was unrelated to transgression. However, from 1990 to 2000, 25- to 34-year-olds did rise (as a share of the population) in more transgressive scenes—in fact, of all variables in our model, only total county population was more strongly linked with growth in 25- to 34-year-olds than transgression. At the same time, again somewhat surprisingly, 25- to 34-year-old growth was unrelated to self-expressive scenes and 18- to 24-year-old growth was negatively related.

By contrast, 1990 levels of baby boomers were unrelated to transgression or self-expression. But Boomer population shares rose from 1990 and 2000 in these scenes. As the boomers aged, they grew more where self-expression was affirmed and transgression denied. The world of pottery classes and bookshops attracted more boomers than scenes of tattoo parlors and punk clubs.18

Should we conclude that young adults do not care about, or even resist, self-expression? No, if we remember that the overall scene includes combinations of dimensions. The results so far show a dichotomous choice between self-expression and transgression in isolation. Transgression seems to win.

But what if we combine the two?—not tattoo parlors or art galleries but both together in the same place. Statistically, one can identify this effect by multiplying two variables together, making what is called a multiplicative interaction term. Figure 5.2 also shows results for this interaction term, labeled “transgressive and self-expressive”

Figure 5.3 shows that, even when controlling for self-expression and transgression as separate dimensions, 18- to 24-year-olds and 25- to 34-year-olds are more concentrated where self-expression and transgression are combined. Growth in baby boomers by contrast was lower in such locations.19

Figure 5.3

This figure shows the impacts of 14 variables on two outcomes: (1) percentage of zip code residents aged 25–34 in 1990; (2) the difference in the percentage of this same group between 1990 and 2000. In addition to the variables listed in the note to figure 5.1, the model includes four scenes measures (plus Communitarianism/Urbanity, part of the Core): LA-LA Land, Rossini’s Tour, City on a Hill, and Nerdistan. These scene variables are factor scores based on a principle components analysis of the 15 scenes dimension performance scores for all US zip codes (summarized in chapter 8). See figure 5.1 notes for more detail.

These results also show that self-expression is not the sole property of the young. In fact, Stern and colleagues show that “knowing someone’s age or year of birth provides very little power in explaining his or her level of arts participation” (Stern 2008, 15). Moreover, if we look specifically at “Neo-Bohemian” amenities20 (like cafes, art galleries, etc.), we find (not shown) that these are often located not only where there are more young people but also where there are more older persons. As this goes fairly strongly against the grain of much recent research on urban growth and the arts, we have elaborated on this “gray creative class” elsewhere.21

Adding Multiple Complex Scenes

We can see the diversity of scenes to which people across and within age groups are drawn by looking not only at self-expression and transgression but also the overall patterns of scene dimensions.

Recall from chapter 3 that Communitarianism/Urbanity is the most typical US combination of dimensions. But there are other major complexes into which scene dimensions frequently combine:22

• LA-LA Land Tinsel is strong in glamour and exhibitionism. Examples of amenities correlated with this scene include nightclubs, tattooing, health clubs, beauty salons, custom T-shirt shops, body piercing, costume shops, dance companies, and automobile-customizing services; it has relatively few fishing lakes, hunting lodges, cemeteries, truck stops, campgrounds, convents, and public libraries. LA-LA Land has a strong presence in Downtown and West LA, as well as in Chelsea in New York and the Loop and Near North Side in Chicago.23

• Rossini’s Tour stresses both local authenticity and self-expression. Associated amenities include antique shops, marinas, fishing lakes, yoga studios, art galleries, used and rare bookstores, coffeehouses, bed and breakfasts, gardening, and outdoor recreation camps. Fast food, car dealers, truck stops, and churches are relatively rare. Places such as Sonoma and Marin Counties in California score high on this scene, as does Greenville, South Carolina.

• City on a Hill features egalitarianism and charisma, and less glamour. Associated amenities include public libraries, churches, and cemeteries; examples of relatively rare items include equestrian centers, yacht clubs, ski resorts, nightclubs, travel agencies, private tennis courts, restaurants, health clubs, nail salons, advertising agencies, art dealers, and interior design. This scene is strongest in the Midwest.

• Nerdistan, a term from Joel Kotkin, combines rationalism and formality. Correlated amenities include scientific and technical consulting services, legal offices, software publishers, R&D, business associations, professional organizations, and computer programming services. Examples of amenities that are relatively rare in Nerdistan include campgrounds, fishing lakes, liquor stores, talent agencies, recreational goods, antique dealers, tattooing, artists, and fashion designers. It is found more in the West and South.

Scenes Tell Us about Subgroups in Addition to Total Population Changes

Who tends to live near and move to these scenes? Total population grew in two of these scenes: Communitarianism and Rossini’s Tour (not shown). However, all these scenes are distinctly linked to specific subpopulations: not all scenes appeal to all people; different scenes resonate with some rather than others. Which and to whom? Figures 5.3, 5.4, and 5.5 show which scenes are associated with which age groups.

Figure 5.4

This figure shows the impacts of 14 variables on two outcomes: (1) percentage of baby boomers (born 1945–1965) in 1990; (2) the difference in the percentage of this same group between 1990 and 2000. See the note to figure 5.2 for more details.

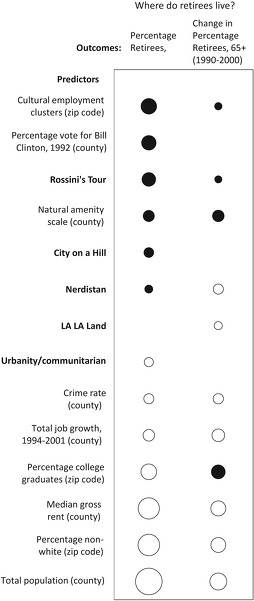

Figure 5.5

This figure shows the impacts of 14 variables on two outcomes: (1) percentage of retirees 65+ in 1990; (2) the difference in the percentage of this same group between 1990 and 2000. See the note to figure 5.2 for more details.

Figures 5.3, 5.4, and 5.5 show proportions of young people, baby boomers, and retirees, as well as their changes. The figures are sorted by how strongly each variable is connected to the level of each age group in 1990.

What stands out first and foremost for young people (aged 25–34) is how urbane they are. They were most concentrated in big cities where crime and rent were high, natural amenities were low, and jobs were growing; they were in zip codes with relatively strong cultural industry clusters, high nonwhite population shares, and few college graduates; they increased more where there were more Democrats.24

Scenes are clearly important factors in accounting for the residential patterns of young people. Again contradicting the image of coolness as an inherent property of youth, however, is the fact that young people (25–34) were most strongly linked with Nerdistan-style scenes of rationalism and formality, and then after that with the generically less communitarian mix of transgression, utilitarianism, corporateness, state, rationalism, and glamour. However, they were also likely to be concentrated in LA-LA Land, which mixes glamour and exhibitionism, and to be increasing in such scenes. Young people were fewer and declined in a Rossini’s Tour mix of local authenticity and self-expression. Youth, to use a term from cultural studies, is a multivocal signifier.25

What about baby boomers? Through 1990, boomers were more concentrated in high rent, Democratic counties, among college graduates and near cultural worker concentrations, where crime and population were high, natural amenities and nonwhites were relatively rare, and jobs were growing. Scenes of Urbanity and Nerdistan tended to have relatively high boomer shares of the population; they made up lower shares of the population in City on a Hill scenes.

From 1990 to 2000, the types of zip codes where boomers increased most as a share of the total population were somewhat different. Growth was higher where there were more college graduates and few nonwhites, but, in contrast to their levels, growth was slower in Nerdistan and less communitarian scenes, shifting from the historic pattern of 1990 levels. Boomers moreover significantly increased in Rossini’s Tour scenes. This finding adds precision to figure 5.3: boomers have shifted not so much into self-expressive scenes per se but into those that mix self-expression with local authenticity (think yoga studios, coffee shops, gardening centers, together with art galleries). Boomer population growth was relatively weak in cultural employment clusters and LA-LA Land, and was unrelated to natural amenities.

Given their large numbers, this “great aesthetic migration” of boomers to new scenic pastures like Sonoma, California, or Asheville, North Carolina, may point toward a largely undocumented reshuffling of the urban landscape. The trend is hard to identify or explain without a theory of scenes and amenities data. Yet clearly, boomers have been on the move, and the scene has been a lodestone showing the way. These results underscore a policy point we stress in chapter 7: what attracts the young and the restless may turn others off; cities may benefit from a wide array of scenes, beyond LA-LA Land glamour, especially if the policy goal is to keep those twenty-somethings around as they mature.

And retirees, 65 or older? They made up larger percentages of the population in lower rent, lower crime, less populous areas with relatively weak job growth and many natural amenities, fewer college graduates and nonwhites but greater cultural worker concentration. Scenes in zip codes with retirees had a communitarian feel, a Rossini’s Tour’s combination of self-expression and local authenticity, a City on a Hill that fuses egalitarianism with charisma, and Nerdistan’s utilitarianism, corporateness, and formality.

While much of this picture comports with a fairly traditional image of where older persons would live (a small-town feel near natural amenities, consistent with Clark’s [2004] finding that older persons tend to live near natural amenities), other aspects point in a different direction, such as the strong connection with cultural employment clusters. The classic picture seems to have mostly persisted between 1990 and 2000, but there are differences. Retirees rose in zip codes with more college graduates and weak LA-LA Land and Nerdistan scenes.

Artist Concentrations: Not Only about the Rent

These results show that where Americans live is often clearly connected with a specific type of scene, with a specific cultural and aesthetic feel—even accounting for “harder” variables like rent, jobs, race, and education. From here, we can see how various scenes link to other key segments of the population, like artists.

Indeed, if urban analysts have recently discussed youth, they have been positively obsessed with people working in arts and culture. Much of the focus is economic, for the reasons in chapter 4.

But there are also more social and community issues linked with artists. Where there are more working artists, so the argument goes, neighborhood quality of life increases. Streetscapes tend to become beautified and street life more vibrant; new opportunities for community connection appear in art classes, studios, and shows.

But there is a dark side to artist growth. Artists are drawn to urban, inner-city neighborhoods with cheap rents and an air of risk, marginality, and diversity, often linked to crime and nonwhite persons. As artists work their magic, the neighborhood grows more attractive. Others, often white, well-off, college graduates, move in. Rents go up, and soon enough, not only the original inhabitants but also the artists themselves are pushed aside as ritzy condos and high-end restaurants replace dive bars and grungy music clubs. That is the standard gentrification story, in a nutshell.

While we cannot observe these processes directly with our data, we can catch some of them. We can ask, for instance, about where jobs in the arts and culture are most concentrated, where they have increased, and what characteristics such neighborhoods have. First, in what neighborhoods do artists concentrate?26 figure 5.6 has the answer.27

This figure shows the impact of 14 variables on two outcomes: arts concentration (1998) and change in arts concentration (1998–2001). These 14 variables are the same as those listed in the note to figure 5.2, except we removed cultural industry concentration and added change in zip code rent (to account for some gentrification dynamics). Change is measured as the ratio of 2001 to 1998 levels, and only includes zip codes that had any arts workers in 1998 (whereas the levels analysis includes all zip codes). We use here a more narrow measure of the arts in contrast to the broader cultural industry variable in our Core models. The narrow measure includes independent artists, writers, and performers, musical groups and artists, dance companies, other performing arts companies, theater companies, fine arts schools, art dealers, and motion picture theaters. We measure arts concentrations as a location quotient, that is, the share of each zip code’s total labor force that works in the arts compared to the national average. See notes to figure 5.1 for more details.

The arts live up to their general reputation. The strongest predictors of where arts jobs are concentrated include the percentage of college degree holders and county population size. Other important factors are LA-LA Land, Urbanity, and natural amenities. Crime rates and zip code share of nonwhite residents are also positively linked with artist clusters, as are City on a Hill and Rossini’s Tour.

Perhaps most intriguing here is that four out of five of the country’s most common combinations of scenes dimensions, even when controlling for one another and the other variables in the model, are positively and significantly linked with concentrations of people who work in the arts and culture. Artists are not only found in scenes of Urbanity, glamour, and exhibitionism, but also in Rossini’s Tour mixes of self-expression and local authenticity and City on a Hill’s mix of egalitarianism and charisma. “Artist” is a far from homogeneous category; its members range from countercultural rebels to church choir leaders to desert landscape painters. This internal differentiation shows up in their concentration in very distinct scenes and locales.

And what about rent, the usual centerpiece of the gentrification story? Our results show arts employment concentrated in higher rent areas. At the same time, we find no relationship between arts clusters and change in rent between 1990 and 2000.

This more complex picture of arts clusters persists if we look at places where artists grew more concentrated from 1998 to 2001. Admittedly, this is not a big enough time period to draw general conclusions.28 Moreover, only some US zip codes have any arts employment whatsoever (about 10,000), and there is little difference between where growth occurred and where concentrations were already high, relative to the country as a whole. Artists, contrary to some popular narratives, do not appear to move incessantly into new terrain. It is thus useful to look at only those zip codes where some arts jobs are present, and the factors related to increased concentration of the arts therein (measured as a ratio of the 2001 to the 1998 location quotient).

The results (in figure 5.6) are intriguing. Arts employment concentration increased in smaller counties with less crime, and in zip codes with more college graduates and smaller 1998 artist clusters. County rent was insignificant, as was change in zip code rent. Three of the five scene factor scores, however, were significant: arts jobs concentrated more in stronger Communitarian and Rossini’s Tour scenes and weaker Nerdistan scenes. That is, not the most urbane, populous, or low rent areas, but areas with scenes that include local authenticity, neighborliness, tradition, and self-expression.

Urban analysts Carl Grodach and Michael Seman come to a similar conclusion about going beyond the standard variables in their analysis of the cultural sector during the Great Recession after 2007. They find

no clear evidence that artists or other cultural sector workers are increasing in affordable, older industrial metros like Detroit and Cleveland whether due to migration from more established cultural hubs, as has been widely reported in the popular media, or otherwise. Both of these regions, which possess below average concentrations of cultural sector employment, have endured declines during the recession not only for cultural occupations as a whole, but for artists in particular. Altogether, the correlation coefficient for cost of living and cultural sector employment growth is weak (.122) and not statistically significant. (Grodach and Seman 2013, 19)

Even in a time of general economic recession, cost of living is a relatively weak determinant of growing arts employment.

And this all stands to reason. Take Chicago’s Wicker Park as an example, one of the paradigm cases of artist-led neighborhood change. Measured against the average US zip code, rent in Wicker Park was likely never low—if low rent was the issue, there is always Toledo. Of course, rent matters at the margins, but so does much else. What Wicker Park had, like Toronto’s West Queen West or Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, was relatively close proximity to existing artist networks, relatively easy access to downtown (for gigs and jobs and other opportunities), a certain sense of dangerousness and excitement (like prostitutes and drug dealers on the corner), and a base of divey, dingy amenities (like bars and restaurants) that appealed to Bohemian images of the starving artist—along with somewhat lower rents than many other North Side neighborhoods.

This may not dramatically alter the overall gentrification story, in that once arts establishments arrive the scene may change in ways that invite new residents. But it does suggest that a one-track model, with simple economic and demographic forces driving inexorably from cheap-rent-seeking artist pioneers to their yuppie successors, is too simple. As we saw in chapter 4, for instance, Bohemian scenes lead to job and population growth in more traditional communitarian cities, but not as much in more urbane cities, where there already are many artists and an arts-friendly social environment.

The point is not that the arts sector “never” cares about rent and “does not” initiate gentrification; we do not want to replace one unidimensional theory with another. It is simply that there are many variables and variants at work. The question is when, where, and why some lead and others follow, and vice versa.29

And there are many more local variants than the standard story would admit. Thus, strong ethnic neighborhoods may resist (or modify) the “first” stage of gentrification by controlling access to housing or making sure that their (sometimes) artist children get first crack, as in St. Louis’s (Irish) “the Hill” neighborhood or Chicago’s (Irish and Polish) Bridgeport. Politically organized arts advocacy groups can (sometimes) lobby city government to keep a foothold in the neighborhood even after new nonartists arrive (as in Toronto’s West Queen West). Arts groups can work with government agencies to provide jobs to local residents in their offices (as Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi document in the case of Cirque du Soleil in Montreal’s Saint-Michel neighborhood). And “social preservationists,” as documented by Japonica Brown-Saracino, sometimes organize to preserve the historic human ecology of neighborhoods even as gentrifying newcomers move in. Many of these variants and more are documented by Grodach and Silver (2012) in The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy: Global Perspectives.

Bronzeville and Beyond

Bronzeville, as we saw above, embodies some core cultural dimensions central to many African Americans: the biblical hope for a world better than ours, based in the equality of all persons before God; the charismatic presence of the fiery preacher, the musician, or the great athlete. At the same time, these are joined by energetic nightlife, bright fashion, dance, innovative music, and a playful flamboyance in dress and appearance, mixed with an often-critical and countercultural stance toward mainstream American society and culture. This combination of historic links to deep religious and cultural currents in African American history together with emergent scenes of wide-ranging entertainment options and cultural facilities surely played a role in Bronzeville’s recent and relatively dramatic growth, led especially by middle-income African Americans.

But how unique is Bronzeville?

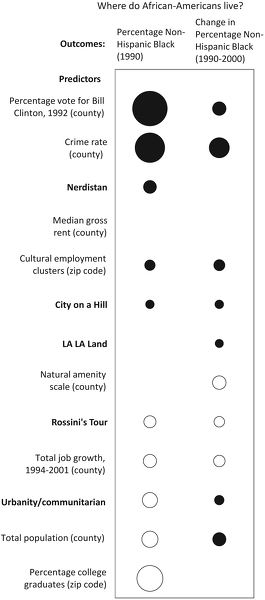

Figure 5.7 shows that Bronzeville is far from the exception. Rather, it looks more like a paradigmatic instance of a broader pattern. In 1990, America’s neighborhoods with higher black percentages of the population tended to be in Democratic counties with relatively high crime, weak job growth, and few college graduates in the zip code. Such neighborhoods often had scenes that evoked classic prophetic biblical themes—the egalitarianism, neighborliness, tradition, and charisma characteristic of Communitarianism and City on a Hill scenes—as well as the rationalism and formality that characterize Nerdistan. However, between 1990 and 2000, African Americans shifted away from scenes of Communitarianism (even if in 2000 black population shares remained higher in Communitarian than Urbane scenes); at the same time they grew in the LA-LA Land mix of glamour and exhibitionism while continuing to increase in City on a Hill.30

Figure 5.7

This figure shows the impact of 13 variables on two outcomes: (1) the percentage non-Hispanic black residents in 1990 and (2) difference in in the percentage of this same group between 1990 and 2000. These 13 variables are the same as those listed in the note to figure 5.1, except that percentage nonwhite was not included as a predictor.

These results fit broadly with the notion of the “the new great migration” (Frey 2004), where many African Americans are moving away from declining Rust Belt areas and into major southern metropolises, like Atlanta and Memphis, and to many suburban areas. However, our results are broader than this: if we add the South to our model as a control variable, we find that, while black population shares increased in the southern zip codes (between 1990 and 2000), the impacts of scenes on African American migration were not altered. Southern or not, zip codes with concentrations of cultural industry workers, scenes of Urbanity, egalitarianism and charisma, glamour and exhibition, saw increases in African Americans—and this, again, independent of rent, education, population, crime, and other variables in our core model.31

A Great Divide?

Much academic research on population shifts and gentrification is by demographers and economists who are traditionally insensitive to more holistic and cultural factors like scenes. The strength of the above results, however, suggests that analytical attention to scenes and amenities has much to offer. And not only to them.

The American media and many public intellectuals often invoke themes of division, separation, and fracture among American residential communities. Conflict is news; nonconflict is boring. What are the main themes and how grounded are they?

Commentators stressing division come from across the political spectrum. In Coming Apart (2013), conservative Charles Murray traces a cultural division of American neighborhoods. On the one hand are “superzips” full of college graduates who maintain classic American civic and family values while leading culturally bubbled lives set apart from their working-class compatriots; on the other are working-class communities where, he argues, these virtues have weakened and positive role models are rare. This division, he suggests, is reinforced by the fact that each group has its own distinct consumption and lifestyle habits, with, for instance, college graduates favoring foreign films and noncollege graduates favoring Hollywood blockbusters. Moderate Bill Bishop’s The Big Sort suggests a related kind of division: as Americans move more and more based on lifestyle preferences, they end up increasingly sorting themselves residentially by politics. Liberals go to where the Starbucks, organic grocers, yoga studios, and Apple stores are; conservatives go to where there are churches, gun shops, and NASCAR. The result is intensified partisanship and mutual misunderstanding, as fewer people bump into those others from the other side of the aisle in their day-to-day neighborhood interactions. Similarly, Richard Sennett (2012), a man of the left, argues in Together that Americans are losing touch with “the craft of cooperation,” as “democratic rituals” of listening and discussing give way to conflict and a tribal us-versus-them attitude throughout society.

This sort of rhetoric of loss, conflict, decline, division, and fracture is as old as America itself, making one wonder when exactly the unified, coherent time before the current crisis of community was. An alternative sees community ties as multiplex. Both conflict and consensus are present at the same time.

This more mixed picture is what sociologists Claude Fischer and Greggor Mattson (2009) found when they reviewed decades of research on the question, is America fragmenting? They found increasing ideological polarization among political elites and activists since the 1970s but more commonality in the general electorate—and nothing like the level of past animosity that led to deep conflagrations like the Civil War. Race and ethnicity remain strongly correlated with divergent life chances. And yet racial residential segregation, while still high, has been decreasing in recent decades; racial intermarriage, while low, has been increasing. There is evidence of proliferating cultural styles and options, and more wide-ranging, “omnivorous” tastes; but whether this amounts to fracture or simply plurality is unclear. The most rapidly increasing disparity is in education, as college-educated persons have grown more likely to intermarry, to live in the same neighborhoods, and to share common tastes.

Starting from this more tempered view suggests some general propositions about how amenities might or might not correlate with America’s major social divisions, in particular education and race. On the one hand, we would expect certain types of amenities to have relatively narrow geographic and demographic reach and to thus be relatively strongly correlated with educational and racial residential concentrations. On the other, these correlations should be only moderately strong. We could add that there should be certain types of amenities that have broader appeal, extending into both America’s more- and less-educated neighborhoods, as well as into areas in which people of diverse races reside.

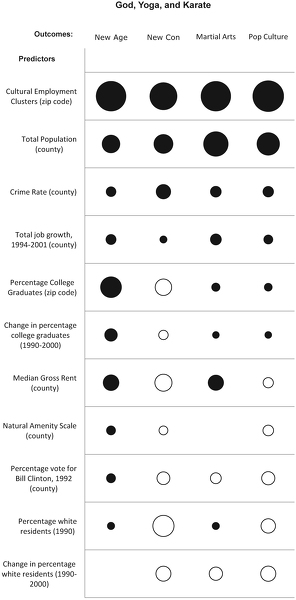

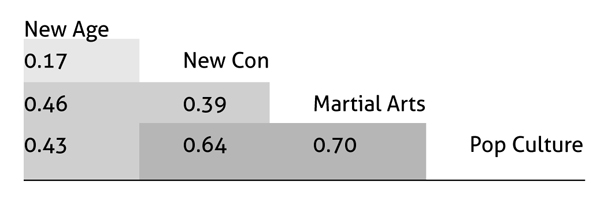

To examine these general propositions more precisely, we shift from more abstract performance score measures of scene dimensions to specific amenities, selecting four types to assess the lines of conflict suggested by standard commentaries. The first two capture types often discussed as conflicting: “New Age” lifestyles versus conservative evangelical Christianity. The second two are more widely shared: popular culture and martial arts. Below we discuss each of these types in detail, and measure them with indicators from our amenities database. Analyzing their location offers insight into the types of practices and experiences that are more broadly shared or more narrowly pursued across American communities. It also points toward a more ecumenical conception of religious-ethical organizations: churches compete and commingle with other cultural and leisure options—arts, sports, music, yoga, karate, and more—as parts of the wider scenes that people may choose to join, defining their allegiances and animosities in the process.

Two major themes emerge in the results. On the one hand, many Americans seem to live in scenes apart: whites and college graduates near New Age amenities; nonwhite and less-educated near evangelical churches. On the other hand, these differences are less hard-and-fast than they might first appear: popular culture and martial arts seem to bridge the apparent New Age–evangelical cultural divide.

New Conservative Churches: Racial Bridging, Educational Divide32

A major and consistent finding in the sociology of religion—confirmed again in Putnam and Campbell’s American Grace—is that, especially since the 1960s, membership and participation in mainline churches has declined. By contrast, conservative evangelical Christianity has been ascendant.

American popular discourse links the rise of conservative evangelical Christianity to the religious right and Moral Majority. Because these movements are connected to the Republican Party, with a reputation for not welcoming ethnic diversity, some draw the inference that evangelical churches are populated by less-educated whites. Their strict sexual morality is then construed as a traditional reaction against the tidal wave of modernity, in its many aspects, from individualism to diversity.

There are many grains of truth to this. In fact, the academic literature often reports that religiously conservative churches, like Southern Baptists, are historically linked to racially segregated worship and opposition to government assistance to African Americans. And, as we show in chapter 6, the evangelical Christian percentage of a county’s population is one of the most powerful ways to predict whether it votes Republican or Democratic. Accordingly, evangelicals have figured prominently in many of the debates about America’s culture divide. Yet the story is more complex.

One of the most significant religious trends in the second half of the twentieth century has been a truly global growth of conservative Protestantism, not only in the United States. Growth has been strongest among new or historically marginal strains, such as Pentecostalism. The evangelical movement in America is just one part of this bigger surge, which involves huge numbers of conversions in Latin America, Africa, and Asia (especially Korea). Synthesizing research on this worldwide movement, one of the leading sociologists of religion, David Martin (2005), concludes that the rise of Pentecostalism is a distinctively modern religious phenomenon, one centered on ecstatic personal experience and the charismatic leaders who help people get there. He further suggests that the rise of Pentecostalism in Latin America especially has fostered an individualistic ethos of personal discipline and cultivation, connected with greater community leadership roles for women and heightened demands for sobriety and family commitment from men.

In the United States, these “new line conservative” churches, or “New Cons,” often understand themselves as outsiders, operating at the margins of the old-guard Protestant establishment. Many of them actively portray themselves as racially neutral, operating beyond or outside the cleavages that have traditionally divided American society. They often include enthusiastic or charismatic worship styles, replete with rock bands and multimedia performances, that help break down traditional social norms about who should associate with whom (cf. Collins 2008; Dougherty and Huyser 2008; Marti 2009). Their combination of individual fervor, charismatic leaders, and egalitarian visions of equality before God, along with strict adherence to divine authority, carries forward the biblical tradition of the City on a Hill in a contemporary context.

These New Cons resemble what Max Weber called inner-worldly activists: missionaries, an army of God, out to reshape the world in His image. Accordingly, many press their members to invite diverse guests to their services. They establish branches in inner-city neighborhoods and actively recruit new members from all races. Nobel laureate economist Robert Fogel has called this upwelling the “fourth great awakening” of evangelical fervor in American history. The preceding three he links with the Revolution, abolitionism, and the concern with material and gender equality that led to the New Deal and women’s suffrage; this one he links with a societal move toward concern with the distribution of “spiritual” rather than “material” goods.

A significant, but not uncontested, body of research suggests that new conservative churches do in fact often reach across racial divides. Thus, Robert Putnam found that evangelical Protestant congregations are more likely to be racially diverse than are liberal-moderate, mainline Protestant ones.33 Michael Emerson found that large evangelical congregations had “dramatic growth” in racial diversity between 1998 and 2007: only 6 percent of such congregations were classified as ethnoracially diverse in 1998 but 25 percent were by 2007. Almost 20 percent of American Latinos are now evangelical Protestants. Similarly, others (such as Joseph Yi) find that racial diversity is especially pronounced among New Cons—those new or less-established strains of evangelical Protestantism, including the typically “nondenominational” megachurches, that are not affiliated with the more-established Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist, or Presbyterian denominations.34 As we note below, we too find that conservative evangelical churches are more strongly associated with racially diverse neighborhoods than are mainline Christian churches.

There is another side to the growth of the conservative evangelical movement, however. New conservative churches have sometimes been more successful than other American churches in reaching across the country’s racial cleavages. But the evangelical commitment to strict moralism and literalist adherence to biblical authority tends to fall flat among college graduates, who are, on average, liberal in morals and relativist in culture—though these sorts of averages can of course mask internal variation.

These general propositions suggest some specific empirical generalizations, which we pursue below: neighborhoods with many New Con churches should have (a) higher levels of overall racial diversity, (b) higher nonwhite shares of the local population, and (c) lower college graduate shares of the population.

New Age Spirituality: New Spiritualities and Divisions

Resistance to the evangelical biblical message from the most educated segments of American society has its own logic. Indeed, new line conservative evangelical Protestantism was not the only religious movement, or even the best known, at least in the popular discourse, to gain strength in the ferment of the 1960s. There were also the hippies, who sought new modes of consciousness, an enlightened religion of Love, and a New Age of Aquarius.

College campuses were key incubators for the new spiritual ideas that emerged from the 1960s counterculture. Of course, not all campuses were hotbeds of Free Love, but places like Berkeley, Ann Arbor, and Columbia, among others, were major launching pads. And the country’s most enduring center of New Age spirituality, the secluded Esalen Institute on California’s rugged Big Sur coastline, was founded by two students from Stanford’s comparative religion department. There they found behind all the world’s religions—East and West—a common Divine Spring, which goes beyond any particular authorities, teachers, and dogmas, flowing through All Being.35

Perhaps the central feature of the new spiritual awakening was a rejection of authority and a concomitant turn to the self. Each of us must find our own personal way to bliss; nobody can do it for us. “Outside” and “external” authorities cannot show the way. They are at best signposts whose directions must be individually tested; at worst, stumbling blocks seeking to replace your own experience, your own journey, with dead letters, secondhand reports, and crushing conformism. As sociologist Paul Heelas puts it, “If there is too much external authority—theistic, traditionalized, polytheistic—one can conclude that one is no longer with the New Age” (2003, 25).

Just as important to the New Age is rejecting traditional, especially Christian, puritanical attitudes toward the body. The body is not a seething tempest of sin and temptation to be dominated, mastered, and controlled. Rather, the body “knows”; its impulses and instincts are the seeds of meaningful attunement to the world; they must be generously cared for, cultivated, awakened, released, loved. Kripal notes that the Esalen Institute was a pioneer in numerous novel bodily practices, not only yoga and body work, but also jogging.