INTRODUCTION

We have now entered the third millennium of the Common Era. The third century of dinosaur research will commence soon, and the study of dinosaurs is in a state of unprecedented activity everywhere. In earlier times, specimens were collected in remote terrains around the globe and delivered to major academic centers in North America and Europe for study. Today, vigorous research programs across the globe are broadening not only our understanding of dinosaur diversity but also the range of the intellectual perspectives brought to dinosaur studies. In Europe, long-standing dinosaur research in England, Wales, Scotland, France, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Belgium, Austria, and Romania is now complemented by programs in Switzerland, Italy, Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, Poland, and European Russia. Early in the history of dinosaur research Africa suffered from the effects of European colonialism, but for the past decade important domestic and international research programs have been hosted in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Lesotho, Ethiopia, Namibia, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Niger, Malawi, Mali, Cameroon, Egypt, Tanzania, Kenya, Sudan, and Madagascar. China, Mongolia, and India remain the most exciting dinosaur terrains in Asia, but Siberian Russia, Japan, Thailand, Laos, and South Korea are now demanding notice. Both Australia and New Zealand continue to yield remarkable dinosaurs. Likewise, the Middle East and southern Asia have potential for significant dinosaur material, as witnessed by discoveries in Georgia, Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Oman, Israel, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and most especially Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Kirghizia. The riches of Canada and the United States continue to increase, but Mexico and Honduras are no longer dinosaurian terra incognita in North America. In South America, Argentina has been synonymous with dinosaur discovery, but Brazil is beginning to make its presence felt, as are Venezuela, Chile, Peru, Uruguay, and Bolivia. Even inhospitable Antarctica has begun to surrender its dinosaurs. Truly, today's dinosaur paleontology is a grand international enterprise.

The Dinosauria was originally conceived in 1984 and published in 1990. At that time there was a dearth of reference texts in the field of dinosaur paleontology. Our intention was to provide the first comprehensive, critical, and authoritative review of the taxonomy, phylogeny, biogeography, paleobiology, and stratigraphic distribution of all dinosaurs and to explore topics ranging from dinosaur origins and interrelationships to dinosaur energetics, behavior, and extinction.

More than a decade has elapsed since the first edition of The Dinosauria was released, and it is fair to say that dinosaur studies have virtually exploded since then. In 1990 fewer than 300 genera had been recognized as valid since the advent of dinosaurs in the early 1800s; since then, more than 200 new genera have been described, corresponding to a nearly 70% increase over the past 14 years! The accelerating pace of dinosaur studies since 1990 is also due to the nascent impact of cladistics, which has called into question some of the most fundamental systematic tenets of our science. The major themes of dinosaur systematics were set in the late nineteenth century with the recognition of a diphyletic Dinosauria whose members were independently derived from what was then called Thecodontia. Thecodonts are now well refuted as a monophyletic taxon, and the composition and relationships of dinosaurs have now been profoundly redefined: Dinosauria is monophyletic and comprises Saurischia and Ornithischia. Cladistics has also established several formerly enigmatic relationships among dinosaur clades. These include first and foremost the phylogenetic nexus of birds within Theropoda but also the theropod relationships of therizinosauroids, the monophyly of prosauropods, and the internal relationships of Sauropoda. This veritable avalanche of new dinosaur discoveries alone makes a total revision of The Dinosauria necessary to reflect the current state of knowledge in dinosaur paleontology.

Chapter topics and authorship have changed since the first edition, reflecting the dynamic fields of dinosaur systematics, extinction, physiology, taphonomy, and paleoecology, as well as our efforts to keep each chapter vibrant and current. Most of the previous authors returned for this new edition, and others, many working on new chapters, were invited to participate. Our contributors collectively have a depth and breadth of hands-on experience with various groups of dinosaurs that cannot be matched by any single person. The slate of authors has expanded from 23 to 43. This time, American authors constitute a scant majority; nearly half of our authors come from Canada, South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, consistent with the international nature of our field.

The organization of this book is similar to that of the first edition. The first chapter addresses the definition and diagnosis of Dinosauria, the origin of the clade, and the interrelationships of the major dinosaurian groups. As in the first edition, the subsequent taxonomic chapters give comprehensive accounts of the groups under consideration in a consistent format. The authors consider all dinosaur species-level taxa and critically review the status of all proposed species. For higher taxa, diagnostic features, anatomy, phylogenetic relationships, and paleobiological issues are emphasized. Each taxonomic chapter includes a table summarizing species-level taxonomy, geographic and stratigraphic occurrences, age, and the nature of the material on which the species is based.

Furthermore, the taxonomic chapters (chapters 2–23) are now provided with numerical cladistic analyses, complete with character descriptions and character-taxon matrices. These descriptions and data are available on the Web at http://dinosauria.ucpress.edu. These chapters thus provide not only a review but also an original comprehensive synthesis of a given higher taxon by an appropriate specialist. Character data for chapter 1 and locality data for chapter 27 are also found at this Web site.

Fortunately, new discoveries and analyses since the first edition of The Dinosauria have made it possible to tie up some of its loose ends. Two chapters on problematic theropods (“coelurosaurs” and “carnosaurs”) are no longer necessary, and “Saurischia Sedis Mutabilis” (i.e., “segnosaurs”) have now found a stable home within Theropoda, as noted earlier. Previously separate chapters on carnosaur paleobiology and sauropod paleoecology have now been folded back into their parent chapters, where they belonged in the first place.

The second section of this new edition of The Dinosauria is devoted to issues of general concern about dinosaurs as a whole. What is the stratigraphic and geographic distribution of dinosaurs? What can be said about dinosaur taphonomy, paleoecology, biogeography, and physiology? And what do we know about their pattern of extinction? On these and other topics the scope of The Dinosauria has been expanded. For example, whereas in 1990 we merely paid lip service to the proposition that birds are dinosaurs, in this edition we embrace fully as a logical sequela of phylogenetic systematics that birds (Avialae) are part of Theropoda. The explosion of relevant fossils, including birdlike dromaeosaurids and troodontids, as well as dinosaur-like birds, from the Lower Cretaceous fossil beds of Liaoning Province, in northeastern China, is impossible to ignore. The task of comprehending these fossils has been made easier by a recent symposium volume in honor of John Ostrom, New Perspectives on the Origin and Evolution of Birds(Gauthier and Gall 2001) and by Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs (Chiappe and Witmer 2002). Although the taxonomic chapters in the present volume discuss the taphonomy and paleoecology of the taxa covered in those chapters, new chapters specifically devoted to these subjects have been added. Similarly, a new chapter on biogeography explores both faunistic and phylogenetic aspects of dinosaur geographic and stratigraphic distribution.

Dinosaur physiology, especially as articulated by Ostrom in 1968 and by Bakker in the 1970s, has fueled a significant proportion of the dinosaur research in the decades that followed. The subject of dinosaur thermal physiology—whether dinosaurs were cold-blooded ectotherms or hot-blooded endotherms—still sparks vigorous debate. In order to frame the discussion, two different interpretations of the topic are provided by Chinsamy and Hillenius (chapter 28) and Padian and Horner (chapter 29). We believe that the interests of our readers are well served by the presentation of a range of opinions on this most interesting topic.

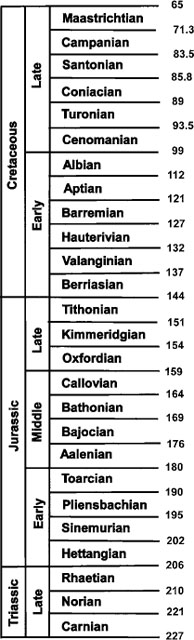

FIGURE I .1. Geologic time scale used throughout the text. (After GSA 1999.)

One of the most highly debated topics in dinosaur paleontology is that of their extinction. In our current understanding, ornithischians and sauropods, as well as many contemporaneous marine and terrestrial organisms, became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, 65 million years ago. This was certainly not the case for all theropods, however, as this group is recognized today by approximately 9,000 avian species. Archibald and Fastovsky (chapter 30) discuss the plethora of causes and processes that have been invoked to explain the terminal Cretaceous extinction and early Tertiary survivorship patterns observed in deposits all over the world. Their joint contribution explores Late Cretaceous volcanism, marine regression, climate, and the bolide impact 65 Ma as possible causes for the near demise of Dinosauria.

As in the first edition, two important conventions are maintained in this new edition of The Dinosauria. Ages of dinosaur occurrences are related to European marine stages and corresponding ages (fig. I.1) as far as possible, although few of the dinosaurs are in marine beds, and correlation with the European sequence may be uncertain on other continents. Often, age assignments are little more than reasonable estimates about the contemporaneity with the classic European stages.

In a work such as this it is important to strive for an internally consistent anatomical nomenclature that may set the standard for future work. In human anatomy, such a standard has been set by the Nomina Anatomica (NA 1983). This document has had a great influence on anatomical nomenclature in general and on mammalian nomenclature in particular even though humans are a peculiarly modified bipedal species and human anatomists have compounded problems of comparison of species by adopting as standard posture the figure with forearms supinated. The Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria (NAV 1994) and the Nomina Anatomica Avium (NAA 1993) represent an attempt to standardize a rational anatomical nomenclature for all tetrapods. Although the nomenclature of the NAV applies specifically to domesticated animals, and that of the NAA to living birds, the general principles articulated by both directly address the problems caused by indiscriminately imposing human terms on other vertebrates.

We adopt the following aspects of the NAV and the NAA: The terms ventral (toward the belly), dorsal (toward the back), cranial (toward the head), and caudal (toward the tail) replace the human terms anterior, posterior, superior, and inferior, which are ambiguous when applied to nonhuman vertebrates. The term cranial has no meaning with respect to the head itself; the appropriate term is rostral (toward the tip, or rostrum, of the head). The terms medial (toward the midline) and lateral (away from the midline) are familiar and common to the NA, the NAV, and the NAA. Since the tail can be considered an appendage, the terms proximal (toward the mass of the body) and distal (away from the mass of the body) are used to designate regions of the tail (e.g., proximal, middle, and distal caudal vertebrae). In addition, proximal and distal are used to designate segments of a limb or of elements of a limb (e.g., the proximal shaft of the femur, the distal end of the radius). For the manus and pes, palmar and plantar, respectively, are used to designate the surface in contact with the ground, and dorsal is used for the opposite surface. An alternative set of terms can be used to designate surfaces on the limb or the manus or pes: extensor or flexor. Finally, the dental nomenclature specified by Edmund (1969; see also Smith and Dodson 2003) is used with regard to the orientation of teeth within the jaws. The edge of a tooth toward the symphysis or premaxillary midline is the mesial edge, while the edge away from the symphysis along the tooth row is the distal. The surface of a tooth toward the lip or cheek (i.e., away from the oral cavity) is labial or buccal, respectively, while the surface toward the tongue is lingual.