Aristocratic Fundraising and the Politics of Imperial Humanitarianism

So far, this book has shown the extent to which philanthropic fundraising was a competitive marketplace. We have illustrated how, from 1870, charities became more entrepreneurial and developed practices contingent on business management: creating and protecting brand identity, extending conceptions of the donor market and ways of mining it, auditing and becoming accountable to their donors and potential donors. This chapter considers these practices in what may, at first, appear to be an anachronistic context: aristocratic philanthropic networks. By this, we mean fundraising initiated, directly organized and overseen by aristocrats, magnates and grandees rather than elite patronage of good causes or societies. Aristocratic philanthropy has a long history, and has encompassed everything from alms doled out to the poor to funding the development of infrastructure to create employment and welfare. This kind of philanthropy was often conservative and self-interested, pitched at quelling or forestalling social unrest and there is a scholarship of ‘social control’ dedicated to it.1 The present chapter is concerned with a different kind of aristocratic fundraising with a much slimmer historiography: the relief efforts of groups of aristocrats and industrial magnates for international disasters or conflicts in the period before the expansion of the semi official, civic fundraising that characterized the Mansion House Funds discussed next in Chapter 6.

Previous chapters have referenced the political framework in which fundraising for domestic causes took place and, in particular, the science of poverty, that most familiar political context for British charity. This chapter examines fundraising in the context of international politics during the Russo-Turkish conflict in the 1870s. The political context and shape of what became known as ‘humanitarian aid’ is best outlined by Rebecca Gill in her book, Calculating Compassion: Humanity and Relief in War, Britain 1870–1914 (2013). Gill’s book takes in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the Balkans crises (1876–78). Gill pays particular attention to, first, the development of the Société Internationale de Secours aux Blessés des Armées de Terre et de Mer (later known as the International Red Cross) during the Franco-Prussian War and, second, its operation, alongside other aid organizations such as the Turkish Compassionate Fund, during the Balkans crises later in the 1870s.2 In this chapter, we turn to an aid organization that has received comparatively less attention, perhaps because its exclusivity in terms of sex and wealth seems so anachronistic to the emergence of a modern humanitarian sensibility.

Presided over by George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower (1828–91), third Duke of Sutherland and one of the richest men in Victorian Britain, the Stafford House Committee emerged in the 1870s as one of the most powerful elite philanthropic networks in Britain, both in its fundraising capability and its ability to deliver aid in overseas conflict areas. Committee members included peers and magnates whose wealth relied upon the Empire. Together, they sought to establish an elite and business-like agenda for humanitarian fundraising. Stafford House was one of a number of aristocratic charitable organizations in this period. It was unusual in being so exclusively masculine in its membership. We focus on it here because, thanks to the bureaucratic acumen of Henry Wright, the Duke of Sutherland’s secretary, it left comprehensive records of high-level fundraising. These archives open a small window onto a vista of privileged private enterprise that combined aristocratic patronage, capitalistic forms of accountability, fundraising and publicity alongside the delivery of international aid. As a case study, Stafford House Committee illustrates the ways in which even a relatively traditional model of fundraising, that of aristocrats calling on networks of high net worth individuals to subscribe to a good cause, could engage with modernizing dimensions of the charity market. Importantly, the chapter illustrates the ways in which old and new practices associated with fundraising could coexist.

International fundraising and grandees

The mechanics of ‘getting money’ for the victims of international disasters or wars in the late Victorian era did not differ noticeably from that for established, domestic charities but such campaigns were especially comparable to domestic disaster funds (for instance, for colliery explosions) in their transient nature and intensity.3 This is hardly surprising. After all, international charitable fundraising had deep roots, not least in Christian-led campaigns for famine relief and against slavery.4 As the nineteenth century progressed, however, the global reach of the British Empire extended the British public’s charitable world vision considerably, as epitomized by the foundation of the British National Society for Aid to the Sick and Wounded in War at the outset of the Franco-Prussian War and the diverse international causes indulged by the Mansion House Funds, generated by the lord mayor of London. The international fundraising through Mansion House is discussed in detail in the next chapter. Here, it is worth noting that it began to expand its fundraising for international causes in the 1870s and generated thousands of pounds towards famine relief and environmental and human disasters. Mansion House’s turning point for international fundraising was the Indian Famine Fund, 1877, which eventually totalled in the region of a quarter of a million pounds. The founder of the British National Society for Aid to the Sick and Wounded in War, Loyd-Lindsay, looked to the Geneva Convention, 1864, as a raison d’être for international humanitarian intervention. The Society operated until 1905 when it was subsumed into the newly created British Red Cross.5 Mansion House and the National Society aside, religiously driven relief funds were the most common form of relief work abroad, with missionary networks called upon to fund overseas orphanages, soup kitchens and famine relief. These campaigns competed in the same charitable marketplace mapped out in previous chapters for domestic causes, and indeed, were often overseen by the same organizations, such as the Salvation Army. Such international initiatives typically abided by the same rules associated with their sectarian, linguistic and class solidarity in order to benefit from the globalization that unfettered imperialism enabled.6

The great and good had always played a part in these kinds of campaigns. As Frank Prochaska has noted, royal and aristocratic patronage was significant, and as Chapter 3 above detailed, the imprimatur of royalty or high-profile individuals conveyed charity brand values such as authenticity, authority and worthiness: one reason why, as we have seen, fraudsters were so keen on appropriating well-known names for their pseudo-committees. Sometimes, however, persons of high net worth and philanthropic disposition were motivated to initiate fundraising schemes themselves. For example, Angela Burdett-Coutts, who inherited most of her banker grandfather’s wealth (around £1.8 million) in 1837 at the age of 23, famously launched the home for homeless women, Urania Cottage, with Charles Dickens in the 1840s.7 However, the late 1870s, and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 in particular, saw a notable spike in elite fundraising initiatives, much of it led by high-profile women for whom the earlier work of Florence Nightingale was both rival and inspiration. Paulina Irby, daughter of a minor noble family from Norfolk, was from earlier in the decade an activist on behalf of Balkan Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Irby capitalized on news in 1876 of the persecution of Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire, what came to be known as the ‘Bulgarian Atrocities’ or ‘Horrors’, to boost both her fund and those of several associates.8 Emily Anne Smythe (nee Beaufort), more usually known as Viscountess Strangford, and often associated with the foundation of St John Ambulance and the development of district nursing, also became heavily involved in both the Bulgarian uprising and the Russo-Turkish conflict, delivering humanitarian aid in a personal capacity and raising funds from Britain to relieve Christians through her Bulgarian Peasants Relief Fund.9 And Burdett-Coutts, again, was instrumental in founding the Turkish Compassionate Fund in aid of Muslim refugees in 1877–78, making some of the earliest and, at over £2,000, the largest donations to the fund. Rebecca Gill has given the most comprehensive analysis of the political context in which these multiple fundraising ventures operated and their varying fortunes.10 Meanwhile, the Stafford House Committee, under the aegis of the third Duke of Sutherland, offered aid to sick and wounded Turkish soldiers in the 1877–78 conflict.

This list of funds and their varied beneficiaries indicates the degree to which, by the latter half of the century at least, humanitarian sympathies were strongly aligned with political choices and economic opportunities. British international aid in the early Victorian period was characterized by solidarity with assorted Christian minorities. The efforts of Irby and Strangford, and their strong support from William Gladstone and within wider Liberal circles, continued this trend. Yet in December 1876, the Duke of Sutherland chaired a meeting to determine what might be done to ‘alleviate the great sufferings’ that prevailed among Turkish soldiers. This meeting led to the formation of the Stafford House Committee for the Relief of Sick and Wounded Turkish soldiers, an initiative that was controversial with sections of the British press more sympathetic to orthodox Christian Russia. One of the richest magnates of Victorian England,11 Sutherland’s wealth and social standing gave him a dominant role in federating an extraordinarily effective fundraising structure which, like many parochial fundraising groups, was led by the principal notables of the era.12 The committee took the name of his London residence, Stafford House, and assembled a formidable coalition of ninety-four benefactors and leading philanthropists. The list included the Nawab of Hyderabad Salar Jung Bahadur who ruled the richest of all Indian princely states; the eccentric recluse Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, fifth Duke of Portland; the notorious Earl of Lucan13; Henry Holroyd, third Earl of Sheffield; and Sutherland’s own son-in-law, Charles Stuart, twelfth Lord Blantyre, who funded a hospital under his own name. Also allied were leading figures such as the financier and former president of the London Committee of Deputies of British Jews, Sir Moses Montefiore, and the conservative politician Baron Henry de Worms, president of the Anglo-Jewish Association between 1872 and 1886, who would later become the secretary to the Board of Trade. Most of the leading ninety-four grandees, arranged by rank and seniority in all public documents, were notable Conservatives.14

Just as competition for donors prevailed in the domestic charity market, fundraising for singular international disasters could also present potential donors with multiple channels for their largesse. The complicated Balkans crisis and its several British funds with varied beneficiaries is an especially good example. The Ottoman and Russian empires had long been at odds by the time crisis erupted. The struggle for dominance in Bulgaria in the mid-1870s opened the door to the resurgence of Russia as a great European power after the humiliation of the Crimean War. The Bulgarian conflict was heavily politicized in Britain, particularly by The Bulgarian Horrors, a pamphlet written from opposition by William Gladstone, in which he set the tone for Christian indignation at Ottoman atrocities against Bulgarian minorities.15 Although Britain did not intervene militarily in favour of the Bulgarians, the political campaign in their support symbolized the renewal of interventionist diplomacy across Europe.16 The issue of humanitarian intervention and for whose benefit it might be practiced became hotly contested. Disraeli, prime minister at the time, denied the involvement of the Ottomans and minimized the brutality of the repression of Bulgarian peasants. At the same time, a variety of Catholic and Protestant groups lobbied to protect multiple ancient Christian groups while orientalist realpolitik played out on an increasingly bleak portrayal of the Muslim other.17

Yet fundraising for humanitarian relief during these crises suggests a complex picture in which some British imperialists upheld Muslim identity and the need to support the weakened Ottoman Empire against the Russian aggressor and its proxies.18 Across the United Kingdom, a wide range of charities attempted to navigate the deep-seated interests and political choices at play. As much as the public might agree that one set of victims (such as the Bulgarian Christians) was entitled to succour, the needs of civilian victims on all sides could be acknowledged. But the politicization of the crisis in Britain was such that the wounded and soldiers of the Ottoman armies, the same soldiers accused of committing the Bulgarian atrocities, could also become subjects of British humanitarian fundraising. As Lady Strangford, an informed observer of the Balkans, observed: ‘As for the Turks, I doubt if for many years Justice will be done them in England – it will require a long time to calm the passions which colour and daub everything they do now in the eyes of some of the English – who see only the surface and known nothing of the depths and counter currents below.’19

Whatever the moral and religious politics at play, each of the funds, in practice, vied with each other for the British public’s donations, and was deeply conscious of the fact. When Sutherland inaugurated the Stafford House Committee it came to light that another initiative with similar objectives, under the leadership of Lord Stanley of Alderley, had already raised and sent £1,100. This fund merged into the Stafford House Committee. Meanwhile in 1877 Lady Strangford, who was fundraising independently to manage hospital structures near the frontline, discovered that being caught in military crossfire was not her only problem.20 She faced competition for donations from Burdett-Coutts’s newly minted Turkish Compassionate Fund, managed by the British Embassy in Constantinople, and raising resources towards rehousing and equipping refugees.21 Strangford complained to the British ambassador in Turkey that the Burdett-Coutts fund had ‘suddenly suffocated’ her own subscriptions, which had been ‘going on well and steadily’. By October 1877, she had to find funding from the Turkish Red Crescent until her own fundraising in the United Kingdom could resume its previous pace.22 While Strangford’s initiative was unusually personal, her fundraising was clearly in direct competition with more distant sympathizers who had sufficient authority and status at home to generate successful rival fundraising schemes.23 Their activism was limited to raising donations and to the devolved management of these funds to professionals in the field, the most significant of whom was Vincent Kennett-Barrington, who had worked with both St. John Ambulance and the British National Aid Society.24 Even here, however, rival fundraising efforts need not eclipse cooperation on the ground. The British ambassador at Constantinople was a key contact and facilitator for each fund. And while Strangford’s work gradually lost its distinctive identity to merge into the Red Crescent’s work, she also associated with Sutherland’s Stafford House initiative, and indeed Kennett-Barrington switched between her operation and that of Stafford House.25 Later on in the conflict, although at times their appeals for donations ran consecutively on the same page of newspapers,26 Stafford House also played a small and adjunct role to the Turkish Compassionate Fund’s work.

The British public navigated this web of competing funds connected to the Russo-Turkish conflict with the same mixture of compassion and pragmatism that domestic charities, as we have seen, were able to harness. In her long series of appeal letters to the readers of the Daily Telegraph throughout 1877–78, Burdett-Coutts thus mingled heart-rending stories of individual suffering with precise accounting of the suitably ‘meagre’ relief given: 4½d per day for women and 2½d per day for children was ‘just sufficient for Turkish peasants’, she had been assured by ‘the native members’ of her committee.27 This kind of appeal echoed advice that Florence Nightingale had given to Paulina Irby on fundraising appeals earlier in the decade: the public wanted to know the details of the distress and the relief of it, but they also wanted assurances that their money was not going to be wasted in any way.28 Witness accounts in the press were therefore a crucial means of generating interest and cash for each of the funds throughout the war, although they needed to be used judiciously. As Burdett-Coutts’s secretary noted in late 1878, there was little point sending another letter to the Telegraph when the public’s attention was focused on recent domestic disasters, including the sinking of the Princess Alice.29

As with other high-status fundraising networks in this period, Stafford House Committee cultivated public sympathy for its recipients, wounded soldiers, by emphasizing their suffering. This focus on giving to the wounded rather than the sick, the military rather than the civilians, reflects the origins and ethos of early humanitarianism and its focus on heroic sufferings of ‘splendid, brawny, broad-backed men’ who for months, ‘shoeless and shelterless’ and living ‘on a pound of black bread a day’, have made the ‘heroic defence of their country that has astonished Europe’.30 Even so, throughout the conflict, many of the reports in the press on Stafford House aid relayed the combination of medical help for wounds with that for the sicknesses associated with war zones, notably dysentery, typhoid fever and scurvy.31 Even less heroic perhaps, by March 1878, reports in the press noted that the committee was engaged in disease prevention, burying the ‘great number’ of dead horses and oxen that lay around Constantinople in order to prevent pestilence.32 Although far removed from the stated objectives of the fund at the beginning of its campaign, press reports implicitly acknowledged that relieving sickness and disease among soldiers (and civilians) were of a piece with assisting victims of war.

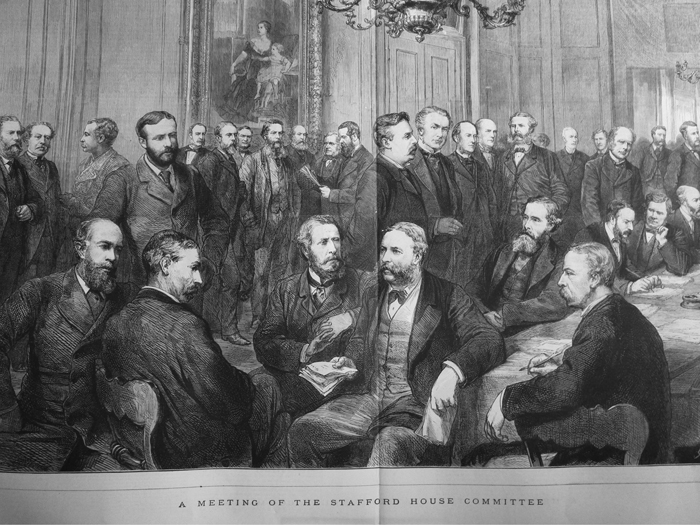

Despite the Stafford House Committee’s broad membership and the public branding of the organization as a large coalition of ‘great men’ (a sketch in the Christmas issue of The Graphic in 1877 of the Committee [see Figure 5.1] promoted the initiative as an elite masculine enterprise that touched the festive fundraising imperatives discussed in Chapter 2),33 in practice, relatively few attended the formal meetings or participated in the reporting processes that committee work entailed. In effect, for much of 1877–78 an executive committee including the Duke, the Marquis of Stafford, the Marquis of Ormonde, General Marshall, General Sir Henry Green and the Duke’s secretary Henry Wright customarily attended the important meetings. In the final year of the committee, the meetings were attended by groups of seven to fourteen more or less titled individuals gravitating around the wealth and influence of the committee. As with other ventures of this nature, the committee membership represented the welding together of patronage networks and commercial interests that all contributed to the fundraising activities of the committee. As the papers of Sutherland reveal, major landlords and industrialists gave to a wide range of charitable enterprises which varied from the most traditional school-building committee, the local hospital associated with their regional and local footprint to the wider range of charitable enterprises that took the fancy of the noble household.34 Even in increasingly democratic times, aristocracy and wealth exuded brand values of quality, reliability and worthiness.

Figure 5.1A Meeting of the Stafford House Committee, The Graphic, 22 December 1877 (Duke of Sutherland at the centre of the image). Authors’ private collection.

As Shapely and Prochaska have shown, this provided and reinforced prestige in the many settings where aristocrats and their families sought to influence society while these giving networks also enabled them to call on ready-made committees and rhizome-like fundraising structures, leveraging influence and funds in localities where, for instance, Sutherland’s name or that of his prestigious associates topped local pyramids of influence. Angela Burdett-Coutts thus expected her commercial connections to fundraise on behalf of the Turkish Compassionate Fund among their employees.35 More generally, aristocrats and grandees expected enterprises, factories and social groups indebted to them to respond to their calls for marshalling fundraising activities. The calls were open to the wider public and, like any other charity, built on their respectability to attract funds. Though their social networks may appear antiquated relics of aristocratic power, the Stafford House Committee was a financial powerhouse with robust claims to modern management. In absolute terms, the committee could match the British National Aid Society in fundraising and reportedly surpass it in effectiveness.

Stafford House’s fundraising strategy showed many of the hallmarks of other voluntary charities of the period. It began with classic modes of subscription that enabled the regular publication of subscription lists associating lesser mortals to members of the committee.36 The Nawab of Hyderabad collected funds independently in his territory (£5,300 in 1876). Alongside the subscription lists, the Duke of Sutherland’s report in April 1879 acknowledged the combination of financial fundraising in the form of concerts and theatrical entertainments and the donation of goods that ‘assisted greatly’ in alleviating ‘the sufferings of the wounded’.37 Some of these concerts had taken place at Stafford House with the Duke loaning his prestigious home in exchange of a guaranteed return. In July 1878, for instance, Algernon Borthwick, son of a conservative MP and proprietor of the Morning Post, was thus given the privilege ‘to arrange [a concert] and to guarantee a sum of £250 to the fund’.38 The exchange of cash against social capital could not have been more explicit and it showered Mr Borthwick with the leeway to entertain in palatial surroundings. The event was billed as being specifically in favour of the Gallipoli Hospital, in receipt of aid from the Stafford House Committee. The event, which was covered by the conservative press, took place as a ‘Grand Morning Concert’ at 3 pm in the afternoon under the patronage of HRH Princess Mary Adelaide and a veritable who’s who of titled ladies. It involved a dozen singers from Mr Mapleson’s operatic enterprise.39 The celebrated actor Henry Irving read some texts, including a short passage from Dickens’s David Copperfield. For a guinea apiece spectators could mingle in Stafford House and benefit from a private visit of the picture galleries of the palatial home. As Chapter 2 highlighted, Sutherland loaned the house for a range of charitable events he favoured.

According to the Committee’s report, by March 1879, they and Lord Blantyre combined had raised £43,750 12s 4d or, in 2014 money, using the economic cost which assesses project expenditures in relation to the percentage of GDP, £68,880,000.00.40 This sum provided fifty salaried medical staff (surgeons and physicians), five staff in charge of logistics, nineteen translators and, directly reporting to their agent Kennett-Barrington, a central office of four accountants and clerical staff. This medical team carried out their work in twenty-one hospitals under their control, three evacuation operations by train and contributed to a refugee shelter.41 Each surgeon received a salary or stipend of £1 a day for their services to the Committee.42 By July 1878, 71,274 medical cases had been treated.43 In comparison, the official British Red Cross sent a little less than one third of this staffing. In correspondence to his wife Alice, Kennett-Barrington reflected on the jealousy arising from this disproportion between a private fund and what claimed to be a national organization:

The National Society do not like Stafford House having done so much more than themselves, as of course the Nat. Soc. ought to be the representative Society of England. They have I believe spent almost the same amount as we have, but the expense of their special ship swallowed up a terrible sum and after all was of little use.44

In proportion, the Stafford House Committee also financed a greater number of medical staff than the Red Crescent of the Ottoman Empire.45 The scale of this humanitarian effort was in itself difficult for the Committee to communicate to the Ottoman authorities who often remained suspicious on the ground. In 1877 the Committee’s Constantinople office thought it necessary to print the monthly record of its staff and work in French and English in order to paste them on the walls of their hospitals. French being the lingua franca among Russian and Ottoman elites, these posters were meant to provide a modicum of safety to the employees of the Stafford House Committee and of Lord Blantyre.46

Accountability, Stafford House and international relief

The fundraising activities associated with this conflict were of a piece with the ‘experience economy’ discussed in Chapter 2, but international relief funds were an explicitly modern exemplar when it came to their management. Kennett-Barrington, who had previously worked in war zones under the auspices of the Red Cross Society, began managing the Stafford House fund in 1877 from Constantinople, taking no remuneration in this role beyond his expenses. As we outlined in Chapter 4, even this practice might be identified by the likes of the Charity Organisation Society [COS] and the press as open to mismanagement. Indeed, Nightingale had advised Irby, in a similar situation, to add a line on her appeal literature to note that ‘the directresses always pay their own expenses’.47 Allegations of misuse of funds did sometimes arise. In December 1877, The World newspaper suggested, entirely erroneously, that £197 of Stafford House funds had been spent on a dinner in Constantinople for Kennett-Barrington and others.48 Potentially anticipating such criticisms, Kennett-Barrington made the Russo-Turkish War Fund accounts publicly available, down to the smallest sums. He harassed the often financially inept medical directors of each hospital which the fund supported for full invoices and detailed returns. In turn, he supplied the Stafford House Committee board meetings with detailed accounts that were monitored and discussed by a specialist finance officer. In Britain, the fund’s only expenditure was on advertising, printing and postage; all personnel connected with the administration of the fund worked on a voluntary basis. Though much of the fund’s income originated from private gifts (some of them very large such as the £6,000 provided by the Duke of Portland or the £3,357 3s. and 5d. sent by Lord Blantyre), every shilling was accounted for by the publication of the Committee’s ‘Final Report’ in April 1879.49

Between the closure of the fund’s activities and the publication of its report, Kennett-Barrington reconciled a variety of invoices, letters of change, notes and exchange rates to produce an unimpeachable financial narrative of the committee’s work.50 All bills were logged into books that were copied in duplicate. Every cheque was registered and issued with more than one signature, the stubs of all cheque books were returned and stored in the Sutherland archives. These accounts were precise and extremely detailed considering the challenges that war presented and the unexpected vagaries of transportation costs. In fact, Kennett-Barrington’s standards of reporting exceeded the norms of many contemporary businesses including some on the stock exchange where most of the members of the Committee would have had interests.51 All the same, a board composed of major landlords, entrepreneurs and industrialists such as the Stafford House Committee was probably accustomed to high levels of formal reporting and accountability. Sutherland himself managed his considerable inherited wealth with a degree of venture capitalism, particularly in relation to railways and mines.52 As a global entrepreneur he had financial interests in a wide range of ventures in Serbia, France, Borneo, Palestine and Syria. In the United Kingdom, over his investment career he ventured in no fewer than eight major railway enterprises or consolidations.53 His peers and members on the Stafford House Committee were equally enterprising and it is not surprising that the humanitarian enterprise expected highly detailed accountability to donors. Yet this accountability was also a major claim to efficiency and transparency to the wider public and the press.

Prior to the arrival of Kennett-Barrington, the funds of the Committee had been mediated by leading Turkish politicians, most notably Ahmed Vefyk Pasha54 whose role Sutherland acknowledged in his preface to the Report while arguing that, due to his other political responsibilities, he could not continue after September 1877. In reality, the Committee had responded to a bruising campaign from British anti-Turkish newspapers such as The Times, who queried whether ‘a single penny’ of aid reached the intended beneficiaries, proclaiming, ‘How the Turks swindle the Stafford House Committee’.55 This anxiety, that only a small percentage of money raised for a fund ever reaches intended beneficiaries, continues to plague international fundraising initiatives.56 In this case, accusations against Vefyk Pasha were rooted in previous allegations of corruption although corruption was, The Times insinuated, the modus operandi for the entire Ottoman Empire.57 In response to these accusations the committee produced their robust paperwork: ‘As to the statement that not a penny sent through Turkish sources has been applied to its proper purpose in Asia, I repeat that we have vouchers and receipts for all the stores sent there.’58 Kennett-Barrington and the committee had to repeat this message on several occasions in September 1877 and the charity distanced itself from Ottoman politicians to avoid being tarred with the charge of corruption hanging over their administration. Only by countering accusations made by The Times and others, denouncing its selective and negative editing of the dispatches from their own correspondents, could the charity attempt to correct the rumours of wasteful handling of charitable goods and money.59

These accusations undermined the presumed respectability one would have associated with the Committee’s social standing. The board of eminent citizens and figures gathered in the Committee was certainly the oldest form of legitimacy available and its composition put it at the summit of the respectability index which stood as implicit guarantor to all charities. Yet even this august company was open to challenges of cronyism and nepotism while geographical distance from the distribution of relief, Kennett-Barrington notwithstanding, diminished the effectiveness of their supervision. The production of accounts and their auditing was a relatively inexpensive countermeasure in this respect, though the complexity of the operation demanded a team of five to deliver the auditing in the case of the Stafford House Committee. The accounts were basic in that they did not calculate the capital depreciation or other forms of incremental losses yet Kennett-Barrington’s figures would have been familiar to anyone working with double entry books. This exercise in public accountability included the appointing of a local auditor Mr Scaife from the firm Wellesley Hanson based in Constantinople.62 Minor supplementary expenditures relating to accounting were then lodged separately.63 At every step of the way the Stafford House Committee took extraordinary measures to represent its work as precisely as could be done.

Where the Committee organization also acted as a business was in its careful handling of networks, supply chains and local administration. The committee’s first priority had been to ensure its supply and distribution lines using existing commercial partnerships in Constantinople and London to ensure the safe passage of goods and money. Whereas the National Society squandered much of its income on a ship destined to maintain its supplies, Kennett-Barrington utilized commercial experience and influence to obtain free passage from commercial lines such as the French Messageries Maritime or the Austrian Lloyds for transportation and delivery of medical supplies.64 The distribution depots similarly used the commercial goodwill of business associates and kept the storage and transportation costs extremely low. At a local political level, the reports and letters of Kennett-Barrington and his associates account for close and constant management of relations on the ground.

This raises the question of the extent to which, in addition to evident accountability to donors, ‘accountability to beneficiaries’, a relatively recent concept in humanitarianism, was also inscribed into the work sponsored by Stafford House and other British relief funds during the war.65 The notion that the inequalities of power between the direct consumers of aid and local leaders were in any way thought of by the administrators of the funds is given the lie by Burdett-Coutts’s Turkish committee members urging her to give scanty allowances to their fellow Turks in distress.66 Yet there is no doubt that, at the very least, the funds were extremely sensitive to local politics.67 In 1877–78 British relief committees operated in the Ottoman Empire at the invitation of the local authorities and had to abide by the specific cultural norms of a Muslim society. Medical staff hired locally alongside expatriates had to produce their medical qualifications on arrival while an edict by the Turkish Sultan forced expatriate medical staff to seek informed consent from their patients before operations. Many surgeons were frustrated by this state of affairs and deplored being unable to amputate at will. In some cases, they hired amputees to argue the case for the loss of a limb with patients at risk of gangrene.68 The need to be sensitive to Islam was implicitly linked to the memories of the Indian uprising of 1857. The presence of the Muslim ruler of the largest principality in India on the Stafford House Committee vouched for the significance of this relief work among Indians, who had contributed about 15 per cent of the fund’s income, and acted as a symbolic guarantor to the fund’s sensitivity to local religious beliefs and practices.69

While competing for donations as outlined above, Stafford House worked with other relief funds in delivering aid. This needed to be managed carefully, since each fund had appealed on behalf of particular, often very different, constituencies of victims. Donors to the Stafford House fund had given money explicitly to help wounded Ottoman soldiers rather than civilian victims: those who intended giving to the latter might be even more circumspect about their donations potentially helping armed combatants. The sudden advance of Russian armies towards Constantinople at the beginning of 1878 precipitated a surge of around 150,000 Muslim refugees, some of whom were hosted in the great Mosques of Constantinople Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque.70 Kennett-Barrington reported in March 1878 that, unlike the successful fundraising for the benefit of Ottoman soldiers and war wounded, the Turkish Compassionate Fund’s fundraising in favour of refugees failed both to meet its target and to raise significantly its profile with the British public.71 The fund did receive sympathetic coverage in the press, even in the comic paper Judy, and on account of the many letters Burdett-Coutts sent to editors.72 Queen Victoria responded almost immediately to the refugee crisis with a donation of £100.73 By the end of January 1878, the Compassionate Fund had sent over £24,000 in money and materials to Constantinople to meet the swell of refugees.74 Yet by April 1878 Austen Layard wrote to Burdett-Coutts to say that he had given notice to the Turkish government that funds raised had fallen off and would not permit ‘relief on so large a scale as that hitherto adopted’.75 By March 1880, the fund was clearly winding down with, Burdett-Coutts claimed, money to feed refugees for five more days only. The fund closed at the end of June that year.76 Rebecca Gill gives a figure of over £40,000 raised for the Turkish Compassionate Fund, not dissimilar to the amount raised by Stafford House. Although ostensibly set up to aid soldiers, Stafford House Committee reports in spring 1878 focused more on the epidemics that decimated refugee groups and filled the hospitals under Stafford House management than on wounded soldiers. The typhus, small pox and typhoid epidemics presented a major threat to life for the patients and carers alike.77 By June 1878, thirteen out of thirty-nine medical staff serving directly under Kennett-Barrington had been taken ill with typhus, and two had died in service.78 Despite their emphasis on aid for wounded soldiers, Stafford House assisted the Turkish Compassionate Fund’s work with refugees and the sick, implying that the constituencies of those in need were inseparable.79 The collaboration also indicates the ways in which rivals for donations in the competitive marketplace could work together in the delivery of aid.

The politics of humanitarian fundraising

Stafford House Committee’s political agenda was intertwined with commercial and class interests that aligned private and public good, geopolitical perspectives and imperialism. The period 1877–78 might be seen as the apex of this alignment and the greatest enterprise in the Stafford House Committee work. The negotiations towards the peace treaty of Berlin brought the Russo-Turkish War to a close and ended the Stafford House fundraising activities. The decision to end the fund’s presence in Turkey, made by the Committee in London, was sent by telegram on 22 March 1878. Kennett-Barrington closed the accounts in July 1878 just as the peace treaty was signed.80 The remaining funds were transferred to help refugees in Constantinople and Kennett-Barrington expressed his concerns regarding the fate of the wounded still in the care of the Committee’s hospitals. There were no obvious structures to which they could easily be transferred. The decision to withdraw from Turkey also highlighted the drying up of funds. The final attempts to raise funds, such as the concert in July 1878, merely facilitated the orderly withdrawal. The hospital in Gallipoli was already officially in Turkish hands on 21 June 1878,81 and by 15 July 1878 all equipment and resources of other hospitals were put in the hands of the Turkish military. The final fundraising of July 1878 was intended to prolong the Committee staff presence at the Gallipoli hospital for only another month. By then the Committee’s fund had completely run out and besides this last fundraising effort, so had its sense of purpose. Turkey’s military defeat ended the humanitarian campaign revealing how humanitarian work was subservient to the necessities of the conflict.

This ending reveals the meshing of politics and humanitarian work. The needs of civilians or, indeed, the many wounded soldiers still in the wards were known and acknowledged but as the war ended so did the urge to intervene to bolster one of the warring parties. Far from any notion of neutrality, the humanitarian fundraising of 1877–78 was explicitly partisan and framed by the context of a Turkish war effort against Russian invaders. While some journalists such as the Times correspondent at Erzeroum Captain Norman, W. T. Stead’s Northern Echo and the pioneering reporter at the Daily News Archibald Forbes clearly wrote in support of Russia, Algernon Borthwick, owner and editor of the Morning Post, used his newspaper as a platform for the defence of the Committee and its work.82 Even Sutherland, usually aloof, made his sympathies public. He received the controversial Colonel Valentine Baker (self-styled ‘Baker Pasha’), an officer of the Ottoman army and viewed by many in Clubland London as a hero despite his conviction for indecent assault in a railway carriage in 1874 for which he served a year in prison.83 Sutherland was much criticized in public and in parliament for his association with Baker and his endorsement of the Turkish cause. He nevertheless embraced the consequences of his political choices when in January 1878, some months before the cessation of hostilities, he delivered a speech at St James Hall in which he compared Russia to a snake and accused Gladstone of being one of its agents.84

This unlikely outburst provoked indignation and derision in equal measure. The Liberal-leaning and irreverent Punch lambasted Sutherland’s mixing of politics and humanitarian aid in no uncertain terms. Despite the speech’s status as ‘the silliest of many silly utterances’, Punch noted the dangerous influence such silliness wielded when spoken by one so powerful. The speech ‘comes from one who bears a ducal title, lives in several palaces, owns a county, figures at the head of a charitable movement’ and has so many commercial interests. As the magazine concluded: ‘Let the Duke of Sutherland stick to his Sutherland improvements and steam engines, and not try to act as an organ of public opinion, or even his own opinion in public.’85 On the opposite side of the political spectrum, Vanity Fair praised the Duke in order to highlight in stark terms the class dimensions of the British political debates, claiming that Gladstone had been properly chastised by Sutherland’s comments. Whereas any ‘ordinary man’ alleging Gladstone to be a Russian agent would have been ‘demonstrated to be ignorant, malignant and false’, the ‘exalted’ person of the Duke had made Gladstone ‘miserable and penitent’. After all, Vanity Fair concluded, ‘Mr. Gladstone had never been considered a gentleman by Society’.86 The contrast between Jingoist and noisily anti-Russian conservatives and pro-Russian campaigners was most acute in the final throes of the war when, before a peace settlement could be reached, the possibility of a Russian advance on Constantinople seemed ineluctable considering the demoralized state of the Ottoman armies. For all his fundraising muscle, Punch dismissed Sutherland as another rich and eccentric man rather than as a force to be reckoned with in British politics. Vanity Fair however noted that Sutherland’s fundraising activities on behalf of the ‘liberties of Europe’ were viewed, by some at least, as a key indicator of his political sympathies in a British context: ‘he has ceased to be a Liberal, and has become a Conservative’.87

Qualifications of the Russo-Turkish War as a war for liberties notwithstanding, the Stafford House Committee did seem to have been largely staffed by conservative grandees. In his lengthy speech from January 1878, which remained largely unreported in the press except in the Morning Post, Sutherland made the connection between humanitarian relief and political intent in relation to the famine relief effort in India, noting that the ‘people who have just despatched half a million sterling in charity’ would ‘hardly be willing to part with such a possession’. By the same token, Sutherland thought it ‘desirable’ to ‘maintain the independence of Persia and of Turkey’. He reversed the arguments set forth by Gladstone and his associates regarding the Bulgarian atrocities to evoke the crimes of ‘Bulgarian avengers’ supported by the Russians: confiscation of property, violation of women, torture and ‘butchery’. Aware of the clearly partisan character of the Stafford House Committee’s activities, Sutherland rooted the authenticity of claims against the Bulgarians in the witness accounts of ‘English gentlemen’ working on behalf of the Turkish Compassionate Fund, in association with the English Consul’s reports of atrocities against Muslim and Jewish women and children.88 While his speech was sensationalized and ridiculed, in many ways it utilized the same narratives anti-slavery campaigners had employed for nearly a hundred years beforehand.89 In the war of words that divided pro- and anti-Russian geopolitical views, charitable operators such as Sutherland staked their claims and political legitimacy on humanitarian narratives rather than class or traditional status alone.90

In contrast with the National Aid Society which staked its origins in the Geneva Convention, the Stafford House Committee had chosen its side. Its hospitals and ambulances nevertheless used all the emblems of the National Aid Society and Red Crescent and Kennett-Barrington had disseminated the text of the Geneva Convention for both belligerent parties.91 Stafford House’s finitude contrasted with the endless reinvention of the National Aid Society and its institutionalization as a unique international ideal and social organization.92 As John Hutchinson and Rebecca Gill have shown, the National Aid Society (or Red Cross as it became), the first international aid movement, remained divided for much of the first fifty years of its existence.93 What funds such as the Stafford House Committee, the Turkish Compassionate Fund or that of Lady Strangford revealed was an alternative origin to the humanitarian movement, one not based in the principles of the founders of the Geneva Convention,94 but in the prudent and modern management of compassion in the context of political and commercial sensitivities.95

It also, of course, had much to do with economic interests. The Stafford House Committee was a network of venture capitalists and investors, bound by commercial as well as moral interest. The Duke of Sutherland was a railway magnate before he was a philanthropist96 and, even though he undoubtedly responded emotively to the plight of wounded Turkish soldiers, he also had designs on Ottoman economic development. In May 1878 he wrote to the British ambassador in Constantinople, Austen Layard, scoping the benefits of investing English capital into Turkish coalmines, specifically those at Heraclea: it would assist the Turkish government and give the English public a ‘real interest in the future welfare of the country’ beyond charitable giving.97 In a similar vein, he also attempted to compete for the creation of a Euphrates railway line,98 which would provide rapid access to India and a more secure access than the narrow Suez Canal.99 Following the closure of the fund for wounded Turkish soldiers, the Stafford House Committee turned to other global affairs although with little of the success that characterized the fundraising of the late 1870s.

The combined strength of the Stafford House Committee for fundraising could be deployed for charity or enterprise in equal measure. As such, it attracted international attention from groups dressing capitalist ventures in humanitarian clothes. The most controversial was an approach by the king of Belgium to the Stafford House Committee, organized as ‘The Upper Congo Exploration Committee’ in 1879. Leopold II, king of the Belgians, had set up the Association Internationale Africaine in 1876 and was, by 1879, financing the exploration of the Congo Basin by Henry Morton Stanley. The king’s private colonial enterprise was cloaked by a broad humanitarian discourse which combined the desire to educate the African people and bring to them Christianity.100 Approaching Stafford House in March 1879, the king suggested that while subscriptions to the initiative ‘ought to be considered a mere act of philanthropy’ they would also confer the right to obtain shares issued by the Association.101 By 1879 trade to the Congo was already estimated at £50,000–60,000 annually for Manchester alone and the committee seemed originally won over by the philanthropic rhetoric. Yet the king’s original brief was very similar to any other venture capitalist enterprise. It involved considerable outlay in return for a percentage of the profits guaranteed by the establishment of a trading monopoly. Though from the first meeting the king claimed to be ‘opposed to monopoly and greatly in favour of free trade’, the Stafford House Committee remained suspicious of the Congo enterprise’s economic model and further scrutiny revealed that the king had misrepresented his plans and the full risks investors might incur.102

A first and contentious point was the legal status of an organization domiciled in Brussels and the legal redress one could obtain against the king of Belgium in a Belgian court.103 Leopold’s reputation across Europe was tainted and between 1879 and 1882, he was the object of allegations in relation to the white slave trade.104 Burdett-Coutts in particular challenged the trustworthiness of the proposal finding loopholes in its funding structure and distancing herself from its trading dimensions. Henry Green disapproved that ‘the philanthropic and scientific objects were not kept separate from the commercial’.105 But it was on the humanitarian programme itself that the proposal eventually foundered. The plan for capitalist exploitation of Congo paid lip service to the development of its people but in such an unconvincing manner that Burdett-Coutts, herself a firm advocate of an African charitable investment, could not accept the validity of the king’s intention. The committee, representing one of the largest groups of real estate owners and venture capitalists in Britain, declined the king’s offer to raise funds on his behalf.

Undoubtedly, members of the Stafford House Committee straddled enterprise and philanthropy in their own careers and were not opposed to what might be termed ‘social enterprise’. As we note elsewhere, the balance of economic interest and philanthropy could be reversed with enterprise per se as a form of benefaction. Other Stafford House ventures, such as the attempt to obtain railway franchises from the Chinese government, were framed in a simpler context of social benefits and development returns through infrastructural work.106 In line with imperialist economic thinking, the committee represented any successful investment as a potentially philanthropic gesture or indeed as a response to imminent or past famines.107 In the context of China which experienced in 1878 one of the largest famines on record108 and for which there had been considerable fundraising worldwide due to the exertions of missionaries such as Timothy Richard and the Shanghai business communities,109 this link between infrastructure and famine was obviously relevant.

As a philanthropic enterprise, the Stafford House committee reached its apex in 1878. When it resumed its formal activities within months of the Russo-Turkish War, on 5 June 1879, as the Stafford House South African Aid Fund, it included a ladies’ committee under the patronage of HRH The Duchess of Cambridge and the presidency of Baroness Burdett-Coutts. At that stage, the Stafford House Committee could have claimed to have brought together most of the significant grandees of the Empire. Burdett-Coutts was no longer competing but instead provided Sutherland’s closest female match in terms of wealth and influence.110 Under her, the formal organization of a ladies committee ensured that women’s contribution was formally recognized in the new campaign.111 The two committees merged in the task to raise a national campaign to finance medical staff and hospitals at the occasion of the war in South Africa against the Zulu kingdom in 1879. The initial funding call was made in the Morning Post of 4 June 1879. It framed the new appeal as a means of continuing the previous appeal while engaging with a critique of existing military health services: volunteer aid was deployed where ‘most needed’ while the lack of medical expertise and equipment meant officers and wounded Zulu suffered as a consequence. It was, then, ‘high time that those who did such wonders in the Turkish war, who treated tens of thousands of cases and saved thousands of lives, should do the same for Englishmen’.112 Another article in the same newspaper on the 5 June mocked officialdom as ‘often slow and constantly cumbersome’.113 The Committee’s main target was to help ‘our poor boys, immature and unseasoned’ who had been ‘hurried off under the short-service system’ to participate in a campaign where ‘dysentery and malarious fever have already prostrated a great number’.114

Despite an initial round of support towards the initial £1,000 needed to send a small surgical team, the fundraising did not go according to plan or precedent. According to the accounts published in its report and audited on 23 March 1880, the fund raised and disbursed a mere £6,201 1s 1d, approximately one-eighth the amount raised two years earlier for the Russo-Turkish War.115 The political climate was different: the war of aggression against the Zulu kingdom was generally not well accepted by the British public and the fundraising explicitly criticized the British administration. While the fundraising failed to attract sufficient attention, the committee claimed to have made a point, perhaps belatedly, by sending trained female nurses to the hospitals of the British army. This was, after all, what Strangford had been doing all her career.116 Meanwhile, the public failed to respond to funding calls more obviously grounded on a critique of military practices than evidence of overwhelming need. If the plight of the Turkish soldier had seemed a worthy cause against a Russian aggressor, that of British soldiers represented a political scandal subsumed in the general critique of the conduct of the war against the Zulu kingdom.

By 1884 the committee began to show its fragility. The grandees were politically exposed and became increasingly unwilling or unable to commit time and resources. Declining financial supremacy may have played a role, of course. For instance, the decline of Burdett-Coutts’s charitable enterprises can be attributed squarely to the catastrophic reduction of her income following her marriage to Ashmead Bartlett, her secretary, which contravened the terms of the will that had endowed her such material fortune.117 The Duke of Sutherland proved increasingly cautious and responded negatively to a similar call to send resources to help General Gordon at Khartoum and subsequently the relief army.118 On that occasion, other veterans of the Russo-Turkish War had taken radically different paths. Baker Pasha conducted a relief operation that ended in defeat while Kennett-Barrington joined the National Society’s participation in the ill-fated Suakin expedition a year later.119 Viscountess Strangford was still on the ground but now working for the St John ambulance rather than as fundraiser in her own right.120 But by 1884 Sutherland had lost much of his appetite for foreign humanitarian ventures and especially when Gladstone, his old adversary, was in power.

Conclusion

The independently wealthy entertained many benefaction schemes across the empire and beyond. In doing so they made constant references to formal liberalism rather than the imperialist notion that might is right.121 In some respects, one might regard these globalized acts of philanthropic activism as the last charitable gasp of traditional elites. The efforts of the likes of Sutherland and Burdett-Coutts seem an almost feudalist throwback when set against the dynamic, demotic campaigns of the charity entrepreneurs with whom we began this book. Yet when examined in detail, it is clear that it was through their engagement with the modernizing practices of the charity marketplace and their concern for efficient delivery that these groups coalesced around humanitarian projects. They shared some important characteristics with domestic charity entrepreneurs, including not only a keen appreciation of the right buttons to push when addressing particular audiences of potential donors, but also an understanding that an openly touted business-like management was a key tool in their fundraising armoury. Clearly, the British donating public responded with a degree of generosity to the competing claims of the various funds backed by their various elites. Cases could be and were made for each set of victims that were strong enough to attract tens of thousands of pounds. In the swirl of fundraising around the Russo-Turkish War in particular, we see one vision of how British aid for overseas objects of compassion might have developed in the longer term. That the Stafford House Committee’s later ventures were a relative failure, however, is reflective of public resistance to the kind of overtly politicized and economically self-interested aid model that it ultimately represented. While this type of aristocratic humanitarian aid lived on throughout the rest of the period, the vast bulk of the British public’s donations towards overseas war and disaster victims went not through their piecemeal efforts, but through the civic framework of the Mansion House Fund which, with some exceptions, adopted both a more neutral political stance and a more innovative business model in its fundraising efforts.