Franchise Fundraising: Mansion House Appeals

It should by now be apparent that growth was a watchword of the new charity market. The voluntary charity sector as a whole grew, many individual organizations scaled their operations up and their donor markets out and, ultimately, the amount of money raised for charitable causes reached unprecedented heights. Indeed, even the conservative, patrician form of philanthropy examined in the preceding chapter had global ambitions. In driving this growth, as we have seen, charity entrepreneurs both mimicked and anticipated emerging business practices in marketing, advertising, branding and accountability. Thus, even as it critiqued poverty and inequality, the charity sector in this period firmly hitched its wagons to a form of capitalism then in the ascendant, such that, as Jo Littler has discussed, its practices can often seem eerily familiar to those studying the supposedly new, business-minded, post-welfare state third sector of the twenty-first century.1 Not for the first time, it is possible to see parallels between a ‘liberal’ nineteenth century and a ‘neo-liberal’ twenty-first, even among groups whose raison d’être is often perceived as mitigating economic liberalism’s grosser iniquities.

In this chapter we analyse the organizational expansion of Victorian and Edwardian charities in a similar light, arguing that many were heavily influenced by, and influential upon, the business replication models that were contemporaneously finding their feet in the commercial sector. In particular, the chapter focuses on ‘franchising’, a social enterprise buzzword in today’s third sector, but a form of charity brand roll-out, which we show had nineteenth-century precedents, the most significant of which is arguably one of the most familiar charity fundraising vehicles encountered (if, we contend, misunderstood) by Victorianists. The chapter begins, therefore, by examining the nature of a franchise, as understood in both business history literature and in the third sector today, showing, through historical examples, that several early voluntary charities helped to pioneer similar expansionist principles. It then examines the operations and growth of the Mansion House and its many appeals for both domestic and international causes, arguing that it represented an initial high watermark of what we term ‘franchise fundraising’, and a conceptual forerunner to the more recent likes of Comic Relief and Children in Need. Franchising, we argue, is not a new charitable growth strategy borrowed from the commercial world, but a tried and tested formula that helped raise millions of pounds for the Mansion House’s appeals from the late nineteenth century.

Social franchising: the future or the past?

According to some commentators on third sector growth and development in the twenty-first century, ‘social franchising’ may well represent ‘charity’s next top model’.2 Seen by many as a means of taking proven good ideas for tackling social ills, scaling them up and making them work to achieve similar social goals across different spaces and territories, in the past decade or so, social franchising has been the theme of civil society conferences, the subject of blogs and press articles aimed at charity professionals3 and the driving force, as the name suggests, behind the foundation of the International Centre for Social Franchising.4 The latter and the Social Enterprise Coalition in the United Kingdom even offer step-by-step manuals and consultation on how organizations and individuals that might wish to can go about engaging in social franchising.5 The concept has also begun, tentatively, to attract an accompanying academic literature, much of it focused on its application in healthcare, but with some interest also in the theoretical underpinnings of the model.6 Much of this discussion has originated in business schools and scholars interested in new conceptions and applications of social enterprise more generally, suggesting that social franchising is conceived of as a modern import from the private sector. Indeed, when introducing the concept of social franchising to practitioner audiences, references to famous business franchises and what can be learned from them – chiefly McDonald’s – are rife,7 and in explaining the various replication strategies charities could employ, instructional literature tends to use the word ‘business’ liberally.8

To a degree this is sensible: as historical studies of commercial franchising tell us, the private sector has made concerted and successful use of franchise models, primarily since the mid-twentieth century, as companies have sought new ways to expand.9 Two forms of franchise have predominated in that time and offer different benefits to the central franchisor firm and to franchisees. What some scholars refer to as ‘traditional’ or ‘agency’ franchising involves a franchisor allowing franchisee agents to sell its products, often giving them sole rights to do so in a given territory, and to exploit its trusted brand in doing so. This is ‘traditional’ because it is seen to have nineteenth-century roots, the likes of the Singer Company having distributed its sewing machines in precisely this manner.10 Car dealerships, petrol retailers and, in Britain, tied public houses represent further good examples of this type of franchise. For the franchisor, this model offers an effective means of distributing one’s product, and a way of doing so with less exposure to financial risk (that resting largely on the franchisee). However, it tends to offer less control for the franchisor, more opportunities for local innovation and therefore a possible side effect of brand damage. Meanwhile, what scholars classify as ‘business-format franchising’ involves the franchisor licensing a ready-made business ‘box’ to individual franchisees, who are given a clear template to conduct their own local version of the original business concept, and who, again, get to exploit an established brand in doing so. This came into its own in the 1960s, with the likes of McDonald’s and Domino’s.11 This arrangement gives the franchisor more control and less chance for the franchisee to deviate from the central brand, but is consequently more demanding of the franchisor’s resources; some franchises may eventually be taken over completely by the franchisor.12 A key point to remember for franchisees in both these formats is that they freely choose to buy into the franchise.

It is understandable therefore that such templates serve as an example to the third sector as it, apparently belatedly, tries to get in on the franchising act. Mirroring the above classification, instructional material on social franchising tends to emphasize a spectrum of replication that is open to charity enterprises, from a flexible form of ‘dissemination’, within a ‘loose network’ relationship between ‘originator’ and ‘implementer’, through a more rigid form of business-format franchising to, at the other end, a situation where local implementing branches are wholly owned and controlled by the originator (see Figure 6.1).13 The undoubted advantage in basing social franchising on its commercial equivalent lies in the fact that the latter has decades of diverse practical experience and a well-developed scholarship of that experience which can be drawn upon, even if the specifics differ in some important respects.14 As even the most ardent advocates of the concept admit, much more needs to be known about the successes (and failures) of the infant social franchising sector.15

Figure 6.1The Social Franchising Manual.

With this is mind, we argue that taking a longer historical perspective offers a different picture of charity replication strategies, which suggests that franchising should not be seen solely as an import from the private sector. Franchising for charitable purposes and for social good has a history of its own which ought to be taken into account as practitioners attempt to resolve the challenges that replicating their models present today.16 Business franchising is, as historian Thomas Dicke contends, a ‘contractual method of organising a large-scale enterprise that evolved out of the traditional practice of selling through agents’.17 Charities, as the previous chapters have outlined, were nothing if not large-scale enterprises, and if we understand fundraising as a business practice, donations as a purchase and branding as a critical component of a charity’s success, then it may not be such an enormous leap to see the networks of volunteer fundraising committees, groups and individuals which were their financial lifeblood as proto-franchisees who were at least informally contracted to the central franchisor ‘firm’. In that respect, the replication and scaling up that charities attracted to the concept of social franchising seek today has much deeper roots than the literature around the supposedly ‘new’ models gives credit for, and they can and should look to models pioneered in the emerging voluntary charity sector in the late Victorian period, just as much as to well-known fast food chains that emerged in the twentieth century. Franchising is another example of the charitable sector both being shaped by and shaping the commercial sector as the two developed in parallel.

Our definitions in place, it is worth noting where different charitable organizations fall on the replication spectrum in Figure 6.1 above. The ‘scaling up’ of the likes of Barnardo’s and the Salvation Army was partly a story of pushing the brand, via advertising, eye-catching fundraising initiatives and other promotional techniques, as previous chapters have shown. But it would be difficult to argue that the central ‘firm’ was not the main motor and monitor of activity in these organizations in this period. Whether in relation to the services delivered to beneficiaries, or to fundraising innovation and prowess, these were charities resolutely led from the centre, and ‘wholly owned’ in terms of the control their founders and central committees exercised over their activities, even at a local level. An ‘army’, even a religious one, is not a franchise, any more than it is a federation.18 The Salvation Army might have encouraged initiative from its subordinates but it did so within clearly defined boundaries, channelling good ideas from individuals through the filter of central office before they were then promoted through centrally produced literature. Editions of The (Field) Officer may have featured a ‘novelty corner’, which spread these innovations, but they also featured highly prescriptive advice on what was expected of each ‘field captain’.19

And yet, the rapid expansion of such missions surely owed something to other commercial replication methods. Just as contemporary companies were beginning to engage in what business historians have referred to as the first (up to 1890) and second (up to 1914) phases of ‘multiples’ retailing growth,20 ambitious missioners understood the need to grow their own ‘businesses’ into new regions and territories. The route that the Army went down was to attract officers who acted much as salaried managers in a retail context rather than as franchisees.21 They were given, as the pages of The Officer attest, much advice on how to run their local operations, and a certain degree of leeway to enact their own ideas in fundraising and evangelizing, but there was not a wholesale business format sold to them, nor did they have the genuine autonomy from the central ‘firm’ that came with operating a franchise: officers could not, for example, choose not to fundraise for the ‘Darkest England’ campaign.

Moving left on our spectrum, however, there are contemporary examples of missions that more clearly aspired to operate along the lines of a ‘business-format franchise’. The London Spectacle Mission offered both eye glasses and spiritual succour to its beneficiaries, generally aging people who relied on continued sharp eyesight for their livelihood, such as printers, seamstresses and cobblers. It was founded by Dr Edward Waring, a member of the Royal College of Physicians, in 1886, and carried on by his daughter after his death in 1891. Applicants for glasses did not pay but had to have a ‘spectacle card’ given to them by a subscriber to the mission (who received a set number of such cards for set amounts donated). They were then tested for a pair of suitable spectacles and sent away with them, along with a Bible and a prayer book.22 It was, according to Truth, a success, distributing over 1,500 pairs of glasses in 1901 alone, even if the Charity Organisation Society (COS) objected to the distribution of spectacles ‘without oculist’s orders’.23 The Warings obviously knew they had a good idea worth replicating, and produced a pamphlet promoting a prototype social franchise in action. Spectacle Missions: Their Object, Advantage and Management gave precise details on how interested parties might replicate the mission for a fifteen-pound outlay on necessary equipment, and hoped that ‘spectacle missions may become a regular and recognised form of work throughout the length and breadth of the land’.24

The Warings offered a ready-made ‘business box’ in an effort to ensure that more people might benefit than they could themselves assist. The ambition to spread their simple but effective idea and to receive a small fee for their advice and necessary equipment means that the Spectacle Mission conformed neatly to ideas around social franchising that are abroad today. The Warings opened and operated four London branches but professed themselves ready to advise anyone who wanted to open their own spectacle mission. Whether it was taken up or not is difficult to confirm, although regional newspapers certainly noted the Mission’s success, and there was a similar outfit begun in New York in 1888.25 The addition of ‘society’ to the Mission’s name in later years might also imply that London was conceived of as a kind of headquarters for a loose network of similar missions.

There is also a sense, however, in which this loose kind of franchising could spring up more by accident than design, particularly when the idea and branding was strong enough. The death of General Gordon of Khartoum in 1885 prompted an outpouring of national mourning, and memorial efforts were eventually channelled into the Gordon Boys’ Home, based first at a temporary site provided by the government at Portsmouth and later, on a permanent basis, at West End near Woking in Surrey.26 Proposed by the Prince of Wales, the homes had a strong military ethos and purpose, with drills, pipe bands, parades, uniforms and martial ranks featuring heavily. ‘To make it national in the real sense of the word’, both boys and fundraising were sought from around the country, with local committees encouraged to finance the accession of local boys to the home. A sum of Twenty-two pounds per head per annum was enough to educate boys and instruct them in trades, although many went on, unsurprisingly, to join the army.27 There was an inescapable logic to this form of memorialization: in his lifetime Gordon had taken an interest in male ‘urchins’; the home could reform its inmates in part via appropriate military training; and Gordon’s name was bound to attract significant donations to pay for the work.

Such was the logic that beyond the ‘official’ national memorial home, several others also seized upon it. In 1885–86, boys’ homes bearing Gordon’s name appeared in Nottingham, Manchester, Croydon, Dover and quite possibly beyond.28 The Nottingham Gordon Boys’ Home was in fact the first to open, in 1885, and expanded into new premises on several occasions before closing in the 1960s.29 The Manchester home was run by Alexander Devine, previously involved in the Lads Club movement, who adopted the Gordon name for an existing home after Gordon’s death, although he had to relinquish control to a committee after running into financial difficulty, and the home was eventually subsumed into the Manchester and Salford Boys and Girls Refuges in 1891.30 The Croydon home was founded by George Murdoch in 1886, and was similarly taken over by the Waifs and Strays Society in 1891, although the home retained the Gordon name.31 The Dover home, meanwhile, was opened by Thomas Blackman in 1885 and attracted the attention of the COS, who identified what appeared to be genuine mismanagement of the home (chiefly that it was not very clean) and saw it as piggy-backing on the ‘real’ Gordon home at Woking.32

Yet the idea that there was one ‘real’ Gordon Boys’ Home and any others were imposters is typically black-and-white COS thinking. In reality, the Gordon homes represented a kind of informal franchise. Alike in name, the homes were also similar in their practical operations. Each home could count on prominent patrons, and each took in boys, educating and training them, involving them in quasi-military pursuits such as pipe bands and later scouting, and often bedecking their premises in images of Gordon, imperial flags and queen-and-country mottoes. Home managers were aware of each other’s existence: as the appeal literature of the Dover home noted, ‘[W]e are glad to say this is one of several Institutions bearing the honoured name of General Gordon’ and, like a true franchise, ‘all of the Gordon Institutions are managed independently of each other’.33 If Blackman et al. were therefore franchisees of the Gordon Boys’ Home ‘business box’, who was the franchisor in this instance? It was not the Nottingham home which was the first, nor the best-known ‘official’ memorial home at Woking, not least since the latter was more than willing to use the COS investigation of the Dover home to its potential benefit, at one point writing to ask what could be done to stop the latter receiving donations from a public which might have confused it with the Woking National home.34 There was no financial relationship between any of the homes in the way one might expect in a franchise today. And yet, it can be argued that there was an informal licensing of the Gordon name and the concept, inextricably linked with his persona, of reforming poor boys. Those who in effect owned that name were Gordon’s sisters, at least two of whom (Miss Gordon and Mrs Moffitt) took close interest not only in the Woking home, but all of the others too; they visited, made presentations, raised money and attended AGMs. Their support and approval was a powerful guarantee for home managers, to the extent that Thomas Blackman took care to note in his appeal literature that the Dover home had been founded ‘by permission of his late sister Miss Gordon’.35 The sisters also protected the brand: Blackman stopped a ‘snowball’ letter fundraising campaign when Mrs Moffitt objected to it.36 They acted, therefore, as unofficial franchisors of the Gordon Boys’ Homes, able to ‘license’ their brother’s name and legacy and confer legitimacy on those who used it.

Franchise replication of another form was practiced by the other great ‘societies’ of the Victorian voluntary sector, the RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, founded in 1824) and the NSPCC (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, founded in 1884). The two shared significant overlap in membership, and were organized along similar lines.37 They were both, by necessity, national organizations, whose central headquarters in London conducted anti-cruelty campaigns and lobbied government for favourable changes in legislation; but they also needed local branches, who conducted rescue and investigative work into animal and child cruelty cases in their own areas, and fundraised to support both themselves and the national campaigns. Branches had a certain degree of autonomy, therefore, but by the 1870s, the RSPCA, conscious of brand management, was only permitting branches to use its name if they committed to defer to the central committee in all legal and financial matters.38 Branches of both societies also had to pay what amounted to a franchise fee to the parent society, in return for services that lent uniformity to the organizations across the country. The Liverpool branch of the RSPCA, for example, in an 1876 report, noted that £300 had been remitted to the parent society ‘in return for an efficient staff of officers supplied during the past year’.39

This model, where local branches sprang up more or less spontaneously wherever groups sympathetic to the cause emerged, where they had their own identity, but also represented the national brand in their localities and where they could innovate locally but still had to abide by certain strict administrative rules emanating from the centre, can certainly be seen as a form of franchising. Local activists in either child or animal welfare might easily have channelled their effort into their own distinct organizations, but found it useful to buy into, literally, the national profile and strength of the larger societies, in the same way that a local sales agent found it easier to sell ‘Singer’ sewing machines. Key to the success of franchising, then, is the strength of the brand and what it represents. Without a clear purpose, a recognizable and trusted name and a central ‘firm’ to nurture and protect it, there can be no franchise. With these important aspects in mind, the next section explores in detail the operation of what was arguably the most financially successful fundraising franchise in Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

Dealing in disasters: Mansion House appeals

The author A. A. Milne once claimed expertise in the Lord Mayoralty of London because he could name four of the many hundreds of men who had held the title; these were, he wrote, Dick Whittington, Dick Whittington and Dick Whittington (who was, of course, mayor on three occasions), as well as, the result purely of recalling from childhood a terrible pun on his unusual name, Stuart Knill.40 This, Milne noted, was an inevitable consequence of the essential anonymity of the position. Each man in the post ‘is never himself, he is just the Lord Mayor’. ‘He can do nothing to make his year of office memorable; nothing that is, which his predecessor did not do before, or his successor will not do again. If he raises a Mansion House Fund for the survivors of a flood, his predecessor had an earthquake, and his successor is safe for a famine. And nobody will remember whether it was in this year or in Sir Joshua Potts’ that the record was beaten.’41 Subsequent histories seem to confirm Milne’s vignette. Less than a fifth of London’s 600-plus lord mayors have been granted entries in the Dictionary of National Biography and not all, it would appear, were even guaranteed the formality of a Times obituary: the nineteenth-century lord mayors may not quite have been ‘a dull and mediocre lot inclined to be old and fat’, but they have certainly been largely forgotten as individuals.42

Relative anonymity should not, however, be mistaken for a lack of significance in the position. Fundraising was a key duty of the Victorian and Edwardian lord mayor and it appears to have been discharged with remarkable success by the collective of the mayoralty’s otherwise forgettable incumbents. A 1910 estimate put the amount raised by Mansion House appeals at more than £7,000,000 in just under forty years since 1871, and a 1927 estimate said £12,000,000.43 In that context, the fact that the Mansion House Fund that has been most written about by historians remains the temporary distress and unemployment fund of 1885–86, which totalled just £80,000, is odd. The Mansion House was more than the occasional (and hardly solitary) bugbear of the Charity Organisation Society that the history of British philanthropy has so far described.44 The fact that the Mansion House has left no central archive of its funds adds further intrigue. What was this inchoate organization and how was it so successful at fundraising? It is a central contention of this chapter that the Mansion House represented an early and enduring form of charity franchising.

The Victorian era created enough opportunities for a franchise based around ‘disasters’ and their relief to grow and develop. Even in the midst of ‘Pax Britannica’, it is evident that Britain and its empire presented plenty of possibilities for sudden, violent death. A necessarily incomplete trawl through press coverage of incidents of multiple fatalities alone, across several distinct categories, suggests that between 1870 and 1912, at least 8,500 people lost their lives in dramatic fashion in domestic disasters. In that period, no less than 3,706 miners died in major colliery disasters across England, Scotland and Wales; at least 4,451 people died in water-based accidents inland and (sometimes quite some way) off the coast, whether fishermen, naval servicemen in non-combat circumstances, civilian travellers or pleasure cruisers; 192 lost their lives in major land-based ‘transport’ accidents, including railway crashes and bridge collapses; 124 people died in ‘industrial’ accidents – factory building collapses or explosions; what must be a bare minimum of 70 people died in multiple fatality fires; 216 people were killed in major crowd crushes; and 194 were lost to what tend to be classed as ‘natural disasters’, including floods and landslides.45

These figures must, of course, be an underestimate, and they can and do take no account of what were surely many scores of further incidents with more modest death tolls that failed to gain any substantive attention from the press. This kind of underreporting had a counterpart in overseas catastrophes where, as today, usually only the very familiar or the very worst received any degree of newspaper coverage. A devastating flood in Italy or Texas was considered news; an inferno in Salonica, or the, it would appear, remarkably fire-prone cities of Canada also garnered coverage.46 Beyond Europe and North America, however, editors considered that British readers wanted to know only about the most appalling famines, the most devastating hurricanes or the human consequences of the most protracted and deadly conflicts. Death tolls appear important in both types of disaster. In the former, this was because its newsworthiness seems largely to have been in its property-destroying effects – whole towns and cities wiped off the map, a point on a map being most readers’ sole concept of the place in question – while in the latter, it was because death tolls were often too large to contemplate, too large even to be recorded accurately by the relevant (often British) authorities. For example, Mike Davis notes both under-reporting of likely death tolls in Indian famines (1877) and press estimates of death tolls so large as to make the mind boggle (‘twelve to 16 million’ was commonly reported in 1898).47

What these reported disasters had in common, however, was that they prompted the opening of relief funds of one sort or another, which appealed to the British public for monetary aid on behalf of the victims or their bereaved dependents. These funds could take many forms and towards the end of the century, newspapers exploited their public profiles to open and manage their own relief funds.48 Yet, of the 168 major home and international disasters that we have been able to trace in the press and that attracted relief funds between 1870 and 1912, it is notable that at the very least, more than a third (66), were accorded some form of Mansion House Fund by the relevant lord mayor of London.49 As A. A. Milne suggested, it was rare that a mayor did not need to issue an appeal during his year in office.50 Thus, even as aristocratic committees and funds attempted to shape Britain’s overseas charity giving in their interests, the Mansion House in great measure superseded their efforts and emerged as a pivotal site of emergency humanitarian fundraising for both foreign and domestic causes, both in terms of the amount of money raised, and in terms of the number and variety of individual funds and appeals launched.

The leadership of civic authorities on this front was not unusual: across Britain the mayors of most cities and towns found themselves opening relief funds when occasion demanded it, with, for obvious reasons, those located in the mining districts (especially South Wales, Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Lancashire) and those on the coast (Hull, Southampton, Portsmouth) most likely to be thus called upon.51 Local sentiment and practicalities created these funds: constituents and perhaps even friends of the mayor and his aldermen were likely to have been affected by whatever calamity had occurred; donations were likely to be largest and most numerous from those in the vicinity of the disaster; and, once gathered, the funds were more often than not doled out to dependents by a local committee who took it upon themselves to monitor family circumstances and continued ‘deserving’ status closely.52 Local administration in respect of local disasters made sense. In general, mayors were simply offering their administrative machines in response to the spontaneous outpouring of generosity that tends to follow within a community hit by an adverse event; in most cases, money simply flooded in and little in the way of ‘appeal’ as such was required to attract it.

Mansion House Funds, although sometimes subject to the same pressures in respect of Greater London–based appeals (including the Distress fund of 1885–86), were in the main something altogether different. Fitfully from the 1860s, and on a more regular basis from about 1870,53 the lord mayor’s fundraising remit was understood by the press and the public to extend far beyond his own limited civic borders in the square mile of the City to encompass not just the United Kingdom and the empire, but the entire globe. While a mayor in a town in Lancashire, say, generally had the option and inclination to initiate a relief fund of his own only when a tragedy in his own borough or its environs demanded it,54 the lord mayor of London was expected to navigate, literally, a world of possibilities, where any and every humanitarian disaster, at home and abroad, might be granted the imprimatur of his office and his residence and be made an object of national charitable appeal. ‘National’ here is key: despite his borough’s growing financial clout, Mansion House Funds were never parochial in their appeal to donors. In fact, despite the fitful efforts of the likes of the Stafford House Committee, they were Britain’s chief means of mounting a concerted, nationwide, charitable effort in respect of humanitarian emergencies.

This worked, in practice, through a form of ‘franchising’ of the Mansion House fundraising ‘brand’. While the London mayor decided which causes to promote, and could declare his intention to receive money at the Mansion House from all corners – in some instances this was all he did – he collected most money nationally for ‘official’ Mansion House Funds with the cooperation of his fellow civic leaders across Britain.55 An early appeal for the 1874 Bengal famine is a case in point. First, other mayors were invited to take out a franchise: the lord mayor wrote to his counterparts in provincial towns and cities asking them to open local funds in the Mansion House’s name and remit the money to London. Only one mayor (of York) seems to have held out, although Liverpool Corporation may not have been alone in delaying a public meeting and a public subscription list for some weeks.56 Scores of councils and parishes eventually joined the effort.57 Second, the franchisees ensured that local markets could be targeted: civic administrations knew which regional newspapers to advertise in, where to post appeal posters, what churches and workplaces to target for collections and which local grandees and industrialists to tap for bigger contributions. Third, this could all happen without overburdening the central franchisor with risk: the fund’s reach could be exponentially expanded without demanding an unreasonable investment of time and effort from the lord mayor. In much the same way that, for example, the Singer company’s use of sales agents helped it to distribute its machines and find local markets for them with relative ease, and made it easier for consumers to purchase machines carrying a brand they trusted, this civic franchise allowed the lord mayor to boost his fund, while at the same time, giving charitable donors/consumers the chance to contribute easily to a prominent national fund.

At a local level the Mansion House appeal could function as a local enterprise; church and civic collections, cash boxes and petitioning of influential individuals meant that a community of charity was reinforced and renewed. The locality was not so much represented through these committees, as it was imagined, and it confirmed traditional alliances of establishment figureheads as well as the depth of religious mobilization. The bulk of the donations were nominal and visible. Thus the subscriber lists of the hugely successful 1877 fundraising appeal in favour of the victims of Famine in India would appear locally and tell a consistent tale of social hierarchies of giving. The £345 15s 7d collected in Tamworth in Devon was received from 159 individuals and groups who each contributed varying sums. Two rich parishes alone contributed £43.58 To be listed individually required contributing more than 10 shillings to the fund (worth between c.£40 and £631 in today’s money). This threshold of giving was clearly identified by the givers who mostly contributed 10 shillings exactly. The ‘social labelling’ arising from this publicity undoubtedly contributed to the local relevance of the fundraising work.59

For the franchisees, the civic leaders and other provincial committees who undertook to co-ordinate fundraising at a local level, we can detect similar advantages at stake from their participation as those experienced by commercial franchisees. It must be remembered that they did not have to buy into the central ‘firm’; local mayors could decline to promote the Mansion House appeal in their areas if they so wished, and the lord mayor of London had no power to mandate their participation. We might well ask if the cause was something provincial mayors felt people in their locality were likely to want to donate towards, why not constitute themselves independently? By placing themselves under the Mansion House umbrella, weren’t they allowing London’s lord mayor and the national fund to take the credit for their hard work? To a degree this is true. But franchising allowed local committees to accrue key benefits. Most obviously, local committees were able to market their efforts in several helpful ways. They benefited from national advertising and communication emerging from the lord mayor’s office.60 They were also able to highlight their own particular contributions to the central fund, showcasing their generosity on a national and even international stage. The individual who gave 5d and the local committee that gave a few hundred pounds could each take pride in a hefty ‘British’ relief fund total. Local committees could also engage, quite consciously, in regional fundraising competitions that often involved sub-franchises. For example, the committee in Clayton-le-Moors, Lancashire, charged with fundraising for the Mansion House Indian Famine appeal of 1897, were solicited to remit their funds to Blackburn who would then send it onward to Manchester, the regional centre. A letter from Blackburn noted that ‘you kindly helped us in 1877 to make this District third on the list of subscriptions’, suggesting that local pride was at stake just as much as individual social capital.61

The analogies here with a modern fundraising franchise such as Comic Relief or Children in Need are obvious. Although often run to a regular timescale rather than in response to particular disasters, such ‘telethon’ style entities similarly ask local groups and individuals to buy into their operation on a one-off basis. ‘Franchisees’ are asked to generate funds in whatever way they see fit, but to use the branding of the umbrella fund in doing so, and thereby to benefit from its national profile, both in terms of the additional funds that might help attract, and in terms of the additional kudos it might accrue to the individual fundraiser. Regional BBC coverage could even be said to generate a similar sense of local fundraising competitiveness.62 In addition, franchisees in all cases avoid heavy administrative burdens. Today’s Comic Relief event organizers need not get a charity licence, and neither they, nor the local Mansion House committees shoulder the complexities and risks of having to disburse the funds they have collected. In the Mansion House 1877 appeal, for example, the London committee took responsibility for remitting the entire fund, in stages, to a Central Relief Committee in Calcutta via Rothschild’s bank.63 The lord mayor also undertook to have the accounts of the fund ‘professionally audited’.64 Both moves indicate a wider truth about the lord mayor’s suitability to head these quasi-national funds, which is that he sat, literally, in the middle of the City of London at a period when the global reach of its banks and bankers was increasing, and an audit culture was gradually taking shape among them.65 In the end, harnessing all of this effort to the Mansion House Relief Fund for Bengal reaped a healthy national total of £200,000.66

Successive lord mayors therefore had at their disposal a powerful fundraising ‘brand’, consisting of a recognizable and reputable name with a centuries-long connection to the establishment, and a relatively recent but developing track record of effective financial intervention in disaster relief. That brand, informally licensed across civic and religious networks around the country, became gradually established in the minds of the charitable public over the final decades of the nineteenth century as more and more funds came and went, for the most part successfully. However, since not all causes could be adopted, the lord mayor was regularly confronted with choices as to which emergencies merited the brand’s use. As franchisor, he had to ensure that he maintained the integrity of the brand, or potential franchisees would demur from using it, just as, for example, a car dealership would decline to sell vehicles from a company whose products had been revealed to be faulty.

There appear to have been several criteria by which lord mayors made these choices, and they are suggestive of the brand’s value and of successive mayors’ consciousness of that value and the need to protect it. First, as noted, press coverage played its part. If newspapers reported a disaster extensively, they or their readers were sooner or later likely to ask if and when a Mansion House Fund would be opened. The press therefore acted as both information source and motivation for lord mayors. Second, lord mayors struggled with two related dilemmas: would the cause in question strike a chord with a national audience, and were there other ongoing Mansion House Funds that might compete for public attention and generosity? Third, the intervention of the great and good increasingly came to influence mayoral decisions: when 300 members of parliament petitioned the lord mayor in 1912 to launch a fund in aid of Turco-Balkan relief, he could hardly refuse.67 Finally, mayors surely had to consider the matter in personal terms: if their fundraising, despite A. A. Milne’s view, was likely to be a key part of their legacy, avoiding undue controversy and ‘brand damage’ was clearly important to their own reputations.

The process by which particular disasters and emergencies were accorded Mansion House Funds was therefore a more or less transparent one, and the merits of different causes were openly discussed in the press. The many instances where a lord mayor declined to open a fund are particularly instructive. Reasons for such refusals varied. Some were relatively uncontroversial. The Regent’s Canal Explosion in 1874 was considered, not unreasonably, to be ‘of too local a character for a national appeal’ by the then lord mayor and a local committee stepped in to marshal local contributions.68 In 1877 an appeal on behalf of a famine in Brazil was rejected as a Mansion House cause because the lord mayor noted ‘we had India on our hands’.69 Turkish refugees were not to get their own fund at the Mansion House in 1878 because the Turkish Compassionate Fund and the Stafford House Fund offered ample opportunity to the public ‘to place their contributions in a reliable and recognized channel’.70 Not being of sufficiently national appeal, likely to distract from or be overshadowed by a greater disaster, or duplicating the work of other committees were all reasons cited for the Mansion House name not being used in respect of a particular disaster, and in many cases these reasons were uncritically accepted.

In other cases, controversy ensued. When two overseas famines occurred at the same time, there could be few in Britain who would get exercised about which most deserved British generosity, and in 1877, clearly, imperial considerations won out over any sympathy felt with Brazil’s plight. This became far more problematic when, as in 1878, major domestic disasters coincided. In the normal run of things, the capsizing of the Princess Alice pleasure boat on the Thames with the loss of 640 lives on September 3, and the loss of 268 men at a pit explosion in Abercarn, South Wales, on 11 September, would have been prime candidates for individual Mansion House appeals, both sufficiently spectacular and heart-rending in their effects to draw donations from beyond their localities. The events occurring within days of one another, however, meant that matters were not so cut and dried. The lord mayor was initially loath to grant Abercarn a Mansion House Fund, reasoning that it would cut the previously announced Princess Alice appeal in two; he was persuaded to change his mind after announcing his decision when a delegation pressed the Welsh claims upon him and argued that ‘great claims upon charity do not as a rule reduce subscriptions, but increase them’.71 The two funds ultimately raised well over £30,000 each in a little under two months, with many provincial sub-appeals, it would appear, made and remitted to London jointly despite the lord mayor’s fears.72

Nonetheless this neglect of the miners’ plight, however brief, seemed to speak of mayoral priorities. We might well ask, had the Princess Alice sunk eight days after the miners of Abercarn were killed and trapped, rather than the other way around, would the mayor have had similar pause? ‘Bill Blades, bricklayer’, who reported ‘from the workshop’ for the radical Reynolds’ Newspaper, would likely have thought not. The working man’s plight, in his view, was routinely ignored by the Mansion House which, his Scotch foreman pointed out, could be traced to the fact that ‘the responders to a lord mayor’s fund are the middle classes’. The mayor might sometimes be persuaded to help the working class in Britain, but he would be more apt to respond, it was claimed, ‘if it had been the cause of suffering n------ anywhere in Africa or of distressed householders in the moon’.73 This dichotomy between domestic and international (less often extraterrestrial) causes was a continual point of contention. The inevitable cry that ‘charity begins at home’ could be thrown at the lord mayor from one side74; from the other, earnest Times editorials insisted that (very often ‘self-inflicted’) distress at home was nothing compared to suffering around the world.75

Two funds during the early 1880s were especially controversial and seem to bear out some of these criticisms of the Mansion House. They also both demonstrate the extent to which the Mansion House ‘brand’, although in the gift and under the protection of the lord mayor, could be wrested from him by the lobbying of prominent citizens on behalf of their own pet projects. In 1881, as the ‘Land War’ raged in the west of Ireland, impoverished tenant farmers refusing to pay their landlords’ ‘rack-rents’ and by their ostracizing actions making one Co. Mayo land agent, Captain Charles Boycott, an enduring addition to the OED, the Mansion House was lobbied to intervene. But while poor harvests had caused a minor ‘famine’ in the same region in 1879–80, responses to London’s Mansion House Fund in respect of this had been rated ‘inadequate’ in Ireland and a Dublin Mansion House Fund was instead inaugurated.76 This was quite distinct from London’s Mansion House, but was certainly suggestive of the power of the ‘Mansion House’ brand.

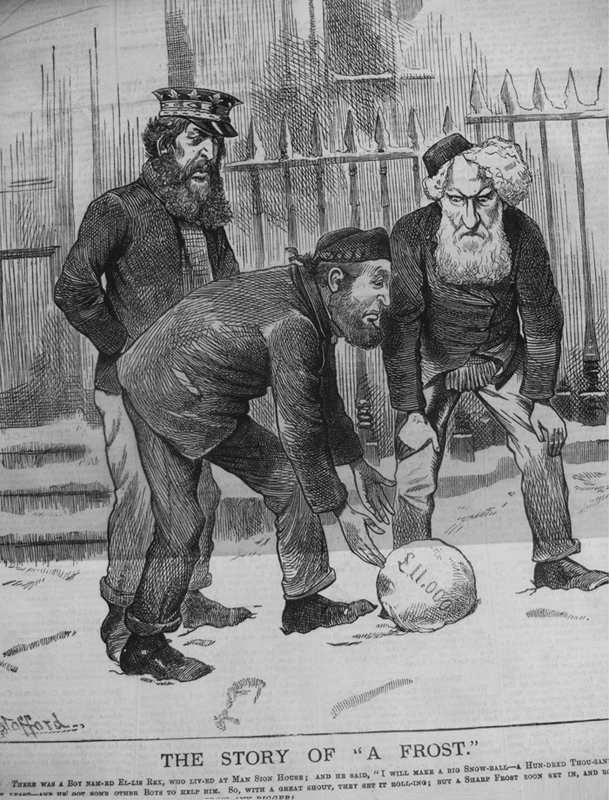

In 1881 the then lord mayor of London, J. Whittaker Ellis, was asked to support, not the distressed tenants, but the distressed landlords of Ireland, who had organized their own ‘Irish Property Defence Association’ against the demands of peasant proprietary and an ‘Association for the Relief of Ladies in Distress’ in support of those female estate-owners who suffered by mass non-payment of rents.77 Ellis went about seeking franchisees in the usual way, sending circulars to mayors around Britain.78 He had been persuaded to open the fund in part by the lobbying of prominent aristocrats, some of them with Irish estates of their own, including the Duke of Sutherland, no wallflower in the matter of political philanthropy as Chapter 5 has shown. Although spuriously claimed as ‘non-political’ by Ellis, who, as Perry Curtis revealed, later described ‘his role in the campaign to counter “the baneful effects of the Land League” and to defeat the fumes of “anarchy and lawlessness”’, it was clearly a pointedly partisan and only dubiously humanitarian effort.79 The decisively political nature of the fund did not please many provincial mayors, and prompted one Irish Home Rule MP to declare later that in the matter of Ireland, the London Mansion House had been ‘a leech or sucker, not a helper or support’.80 One cartoon (Figure 6.2) that portrayed Sutherland and others struggling to push the fund beyond £11,000 was not wholly accurate; but the final amount of £21,000 was hardly enormous in the context of Mansion House Funds, and betrayed a sense that brand damage had occurred.

Figure 6.2‘Frost’ newspaper cartoon. D593/P/26/7b. Courtesy of Staffordshire Record Archive. The Story of ‘a Frost’. There was a boy named Ellis Rex who lived at Mansion House; and he said, ‘I will make a big Snowball and Hundred Thousand at least’ – and he got some other boys to help him. So with a great shout they set it rolling; but a sharp frost soon set in.81

A year later, another cause celebre got the very same mayor and the Mansion House into further hot water. His literary connections in Iceland alerting him to ‘famine’ in that country, William Morris, the pre-Raphaelite designer, author and activist, pushed it onto the relief agenda, first by writing to newspapers and forming an ad hoc fundraising stream, and then by endeavouring to secure a Mansion House Fund, as he had on a previous occasion in 1875.82 Morris keenly understood the power of the lord mayor’s stamp of approval. Writing to the wife of an Icelandic friend he impressed upon her the necessity of getting a ‘good’ committee together in London, ‘for the names’ sake’ if not necessarily for the administrative work they might do. The more prominent the committee, the greater the likelihood, he explained, that the lord mayor himself would chair the committee.83 All went well until the press started to question the very existence of the famine in Iceland, and Ellis, who had been tempted into granting a Mansion House Fund, found himself denying repeated claims of ‘fictitious woe’ in Iceland.84 Press coverage descended into claim and counterclaim and philosophical debates over what precisely constituted a ‘fact’,85 but, even if the distress was, it would appear, genuine, further damage had been done to the Mansion House’s reputation among the public. The Northern Echo questioned the lord mayor’s judgement in the matter: ‘he stands by the famine, but he does not show that before opening the subscription list he made himself acquainted at first hand with the facts. He does not seem to have got any nearer to Iceland than Copenhagen’.86

Any such questioning of the lord mayor’s political biases, judgement or trustworthiness risked damage to the Mansion House brand, and Ellis’s successors seem to have grasped the fact. To use a twenty-first-century term, in the wake of these missteps and of the similarly criticized 1885–86 distress fund, a degree of ‘brand management’ was required. By the 1890s, therefore, it would appear that lord mayors were increasingly reluctant to open funds on the say so of others, or in response to a public clamour without proper consideration. Speculating upon a possible Mansion House Fund in aid of the victims of English floods in 1891 the Yorkshire Herald cautioned the incoming lord mayor:

There is no doubt about the distress that has been caused by these floods, and the movement for assistance has influential support. But whether the matter is serious enough for the lord mayor to take it up is, perhaps, open to question. Mr Evans, warned by the mistakes of some of his predecessors, will be careful not to make an appeal from the Mansion House unless and until he is sure of his ground.87

Mr Evans both heeded this call and did not. During his mayoralty, despite requests, there was no Mansion House Fund for striking Durham miners (the feeling in London being against them), for the London unemployed, for the victims of the Liberator Building Society scam or for cholera victims abroad.88 Yet Evans made a promise to a national mining accident association, in a meeting held at the Mansion House, that he would meet any mining disaster during his term of office with ‘an immediate response’, words that may have comforted the Bill Blades of the world, and on which he made good within weeks as a Welsh colliery explosion took 112 lives.89 Colliery disasters, after all, could be and generally were presented as de-politicized events, and tended to be extensively communicated by reporters and artists on the scene: the mayor and the donating public knew they stood on relatively safe ground with them.

The Mansion House, then, remained for the most part a name that signified to donors up and down the country that their money would be going to a worthwhile cause, through the hands of trustworthy persons and with proper oversight to ensure that only the most ‘deserving’ cases benefitted by the proceeds. The nature of the lord mayor’s tenure meant that temporary franchisors occasionally allowed personal connections and hobby horses to tarnish the brand, but this was a rare enough occurrence. It is worth noting, moreover, that while the lord mayoralty itself may have changed hands each year, there was crucial administrative continuity in the mayor’s private secretary: William Soulsby held the position from 1875 until 1931, the very period when the Mansion House Fund developed into an efficient fundraising franchise.90 We can speculate that he represented a crucial form of institutional memory; certainly, when he wrote a recollection of his fifty years of service for the Times in 1927, he deemed fundraising ‘for the relief of distress all the world over’ a crucial part of the mayor’s, as he saw it, increasingly important role, and one which was worthy of half the full page the newspaper afforded him.91 And while the lack of archival records from the Mansion House itself makes it difficult to determine Soulsby’s precise role in administering each of the funds, we do know that in 1913, beneficiaries from a Mansion House Flood Fund were sufficiently grateful towards Soulsby that both he and the lord mayor who had called the fund into existence were rewarded with presentations of inscribed silver boxes bought with 3d subscribed by ‘every man who received relief from the fund’.92

Overall, then, while some damaging mistakes were made in who was allowed to employ the Mansion House brand in the 1880s, lessons appear to have been learnt from them. As the bruised honorary secretary of the 1885–86 distress committee told the Times in 1894, one reason for the failure of that venture had been ‘the way in which many of the members of the committee mounted on their own hobbies and fed on their own faddles’ recommending little-known charities to receive funds. ‘Thus much of the money collected was dribbled away and did no good’ The current lord mayor, he was pleased to note, had stated that ‘local distress should be dealt with locally’ and would not repeat these errors.93 By the end of the century, the Mansion House name and reputation had sufficiently recovered that its two Indian Famine Funds in 1897 and 1900 raised the remarkable sums of £773,000 and £390,000 respectively94; its South African War and Refugee funds took in well over a million pounds all told, and funds for a 1903 Volcano eruption in St Vincent in the West Indies and a 1909 earthquake in Italy took £75,000 and £140,000 respectively.95 One of the most lucrative Mansion House Funds in aid of a (more or less) domestic disaster came at the very end of our period, when some £414,000 was raised for families, many based in Southampton, who lost relatives on board the Titanic.96

How accurate is it to view the Mansion House Fund as a franchise? In the sense that its ‘big idea’ was merely gathering money to address the aftermath of disasters, it is not ‘social enterprise’ in quite the way we might understand today. But in its format, it surely conforms to what historians of commercial franchising have understood as early agency franchising, where a central ‘firm’ creates, supplies and successfully brands a commodity that can be sold to consumers by multiple sub-agents, who are free to buy into the franchise or not as they see fit. In this instance, that commodity was not cars or sewing machines, it was compassion and the chance to express it monetarily, as individual donors, as regional communities and as a nation. There is a very strong case for arguing, therefore, that given the volume of money generated, the Mansion House appeals stand as one of the most successful franchises of the era, whether of a commercial or non-commercial type.

Conclusion

It is not, then, too much to claim that the development of some charitable organizations in this period were influenced by the ‘replication’ models that were developing contemporaneously in the commercial sector. The Mansion House stands as the ultimate umbrella brand, available for co-option by any regional or local committee who wanted its imprimatur to raise money in a particular cause. It can be seen, in some respects, as the Comic Relief or Children in Need of its time, creating the opportunity to give, which could then be franchised out to multiple sub-agents across the country, the central committee’s role being to promote and protect the brand, and receive the money in its final, proudly proclaimed total before disbursing it to the appropriate agencies. Other more integral organizations followed different commercial replication models, which encompassed a kind of multiples approach then gathering pace in retailing, and variations on a theme of business-format franchising. Thus, while the notion of ‘social franchising’ has certainly been having something of a moment in the 2010s third sector, it arguably has roots that go far deeper than many of its evangelists may realize.

This is not to suggest that there are no new ideas in charitable fundraising, since there are evidently nuances and innovations aplenty in how charity franchising is conceived today. But it is about showing that the roots of this philanthropic practice, like the roots of many others, are to be found in this crucial period of charitable development, and that to the extent that this new charitable world was a product of and grew up in close parallel to the modern capitalist economy, it partook in and has a place in the birth and development of some of the business world’s most widespread and successful phenomena. How to grow an idea, how to generate money and how to protect one’s hard-won reputation are all skills that businesspeople value to this day; they are also all skills that the entrepreneurial men and women involved in the Victorian and Edwardian charitable world were well versed in.