Annotations for Proverbs

1:1 proverbs of Solomon. Solomon’s reign is described in the books of Kings and Chronicles. His were years of unprecedented and rarely surpassed success and prosperity for Israel. Solomon inherited a united kingdom won by the wars of his father David. The beginning of his reign was peaceful, with no significant internal or external threats. Such a time was right for productive and positive international contact, including that between wisdom teachers.

The Historical Books describe Solomon’s wisdom as having a divine origin. In response to the king’s piety (1Ki 3:1–15), God allowed him to choose a gift. Rather than wealth or honor, Solomon asks him for wisdom, and God grants it to him. Indeed, God was so pleased with his choice that he also gives him honor and wealth. The narrative that follows tells stories about the exercise of this divinely granted wisdom (1Ki 3:16–28).

In general, every king was aware of the need for wisdom in order to govern well, though it was not always set above other priorities the way that it should have been. It would be easy for success to be measured by the criteria inherent in one’s personal ambitions. In contrast, wisdom is a quality that will pursue the good of the people and look to establish successful domestic and international policies.

Parallels to Biblical proverbs are found throughout the literature of the ancient Near East for the entire OT period. In fact, some of the earliest literary texts are proverbs dating to well over a millennium before Solomon. On one hand this is no surprise, since Solomon is identified as a collector of wise sayings. On the other, similarities do not suggest borrowing, since wisdom was common currency in the ancient world as it remains today, and observations about life take on similar parameters and stimulate similar analogies and insights.

1:6 proverbs and parables . . . riddles. This verse lists three of the many types of wisdom writings. The proverb (Hebrew mashal) is an aphorism, a short statement often consisting of contrasting parallel lines. It is generally moral-laden and always didactic in character. Parables are extended contrast pieces that in narrative form both tell a story and require the audience to see a double or hidden meaning (see notes on 2Sa 12:1–4, 6). Although there are no riddles in the book of Proverbs, they were apparently common enough as a form of intellectual game (see Jdg 14:12–14). riddles. In the OT this Hebrew term appears only in Proverbs and comes from a root that is usually translated “scornful” or “cynical.” This may be an attempt to downgrade riddles as true wisdom sayings.

1:8 my son. Egyptian instructions are often addressed as advice to a son from a father. The book of Proverbs, particularly chs. 1–9, also presents admonitions of the father to the son. Even so, though the Egyptian instructions mention the father-son dynamic in the prologue, reference to father and son does not work itself into the advice section of the text as it does in Proverbs (e.g., vv. 8, 10, 15; 2:1; 3:1, 11, 21; 4:1, 10, 20). In addition, other Semitic practical wisdom texts are similar to the book of Proverbs, not just Egyptian wisdom. Other examples include the Aramaic Words of Ahiqar (lines 82, 96, 127, 129, 149), as well as Akkadian and Sumerian (admittedly non-Semitic) wisdom. Even so, all the Near Eastern traditions clearly place their practical wisdom in the setting of father and son. This leads to the debate as to the exact nature of the relationship. Is it biological, or is the language a metaphor for a professional relationship, i.e., of a teacher and an apprentice? Often the two probably coincided, with the biological son succeeding the father in his profession. Egyptian instruction seems the most consistently focused on profession, but even there its teaching often articulates principles that are useful for getting along in life generally. The wisdom of Proverbs is a mixture of family, professional and scribal advice. However, there is no doubt but that the father-son dynamic is often biological. Adding support to this viewpoint is the appearance of the mother, rare to be sure, along with the fathier in the instruction of their son (v. 8; 6:20; 31:1). your mother’s teaching. While the book of Proverbs is similar to other ancient Near Eastern texts in that it consists of a father’s instruction to his son, it gives a larger role to the mother in her son’s education. An exception is found in the conclusion of Dua-Kheti’s teaching for his son Pepi in The Satire of the Trades. To be sure, only Lemuel’s mother actually speaks in the book of Proverbs (31:1–9), but the fact that the father speaks of the teaching of his wife is significant.

1:9 garland . . . chain. The words of the father and mother, which embody the wisdom of the society, can become a decorative wreath for the son’s head and a chain or necklace of office. Just as a champion is adorned with a garland of victory and a newly appointed official is given the chain and vestments of his office, so too is the attentive son assured of prosperity and a stable life (Pr 4:1–6). As Ptahhotep says, “The wise follow their teacher’s advice [and] consequently their projects do not fail.” In Egyptian literature Ma’at, the goddess associated with wisdom, truth and justice, provides a garland of victory to the gods and is worn as a chain around the neck of various officials.

1:12 let’s swallow them alive. The metaphor of swallowing for destruction and death probably derives from the Canaanite picture of the god Mot (“Death”), who performs his ghastly task by swallowing his victims. Baal’s death at the hands of Mot is described as Mot’s swallowing him “like an olive-cake.” grave. This Hebrew term (sheol) is the most frequently used term for the place people go after they die. Often it refers simply to the grave, as here, though the grave is often seen as a portal to the netherworld (see the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld”).

1:15 do not go along with them. The Egyptian Papyrus Insinger also counsels against joining in with evil fools. See also Pr 13:20.

1:20 wisdom . . . she. Wisdom is personified as a woman here for the first time in the book. The fullest development of this metaphor is found in 8:1–9:6 (see note on 8:12). Much discussion has taken place concerning her identity and background. Many see her description as connected to an ancient Near Eastern goddess, whether Asherah, Ishtar, Isis, or Ma’at. One can make the strongest case for the latter, since Ma’at, like wisdom, refers to the order of creation, truth and justice. Often Ma’at appears to be no more than an abstract concept, but occasionally she appears as a goddess, though not one that has been given a developed personality in Egyptian literature. Most likely, Wisdom should be treated as a poetic personification.

2:4 as for silver . . . as for hidden treasure. The comparison between wisdom and the value of various types of riches (cf. 3:14–15; 8:10, 19; Job 28) is also attested in Egyptian wisdom, as exemplified by the “Instruction of Ptahhotep”: “Good speech is more hidden than greenstone (emeralds), Yet may be found among the maids at the grindstones” (lines 58–59, AEL.1.63).

2:16 adulterous woman. Lit. “strange” woman. wayward woman. Lit. “foreign” woman. For a full discussion of these terms, see the article “The ‘Strange’ and ‘Foreign’ Woman.”

2:19 None who go to her return. The “strange woman” (see previous note) often, as here, takes on mythological proportions. Her house leads to death, and none who go to her return, implying that they are consigned permanently to the realm of the dead. The description of the netherworld as a “land of no return” is reminiscent of Akkadian mythology. In the Assyrian Descent of Ishtar and in the description of the so-called House of Death found in the Gilgamesh Epic, the realm of the dead is called “the house that none who have entered it leave” and “the road from which there is no way back.”

3:3 bind them around your neck. The demand to bind something on one’s neck is not found outside of Proverbs (but see also 6:21; 7:3 admonishes the son to bind the father’s commands on his finger). However, the language reminds the reader of Dt 6:4–9, which includes a command to the people to tie the law on their hands and bind them on their foreheads. Perhaps the neck is here mentioned because disobedience is elsewhere described as a stiffening of the neck (e.g., Jer 7:26; 17:23). tablet of your heart. In the ancient world, writing was often done on tablets. While in Mesopotamia writing tablets were normally made of clay, in the OT the term probably refers to wooden boards covered with wax (though the Ten Commandments were written on two stone tablets; Ex 24:12). The metaphor of the heart as a tablet (not a tablet worn on a cord over the heart as some would have it) on which one writes the law, of course, points to an internalization of God’s commands in one’s life, so that not only one’s actions but also one’s motives are pure (see also Pr 7:3; Jer 31:33). The only other place where writing on the heart is specifically mentioned is Jer 17:1, where it is said that Judah’s sin is inscribed on their hearts.

3:6 make your paths straight. Trusting the Lord makes life’s journey much easier. The metaphor of the deity straightening one’s path is found in Babylonian literature in the hymn to the goddess Gula, the goddess of healing, who is identified as the one who gives life to faithful followers and makes a straight path for those who seek her ways. For Israelites this metaphor is particularly meaningful since much of Israel is hilly and rocky, giving travelers a great appreciation for smooth paths on level terrain.

3:15 more precious than rubies. While both rubies and sapphires are forms of the mineral corundum, which consists primarily of aluminum oxide, rubies are much rarer and therefore considered more precious. The Egyptian sage Ptahhotep also compares true wisdom with rare gems (emeralds), adding weight to such analogies. Diamonds were not known in the ancient world.

3:18 tree of life. The immediate background of this image is the tree of life in the Garden of Eden (Ge 2). Those who embrace wisdom are like those who embrace the tree of life; i.e., wisdom is the source of life in all its fullness. A symbol commonly referred to as the “tree of life” by modern scholars is well attested in ancient Mesopotamian art, though no textual evidence identifies it as such. It is more appropriate to identify it as a “cosmic tree”—a tree located in the center of the world that links the cosmic realms.

3:19 By wisdom the LORD laid the earth’s foundations. It is not unprecedented that creation is said to be the product of a deity’s wisdom. In the “Memphite Theology,” the Egyptian god Ptah is said to produce the world through his heart and tongue, standing for his wisdom and his speech. According to the sages, the creative act, in order to fully demonstrate God’s presence and concern, is followed by an ongoing and sustaining of the structures of the heavens and the earth.

3:20 watery depths. Hebrew tehom, which refers to the primordial cosmic ocean. In the Babylonian Creation Epic, Enuma Elish, the goddess representing this cosmic ocean, Tiamat, is divided in half by Marduk to make the waters above and the waters below. See note on Ge 1:2; see also the articles “The ‘Vault’ and ‘Water Above,’ ” “Cosmic Geography.”

3:27 Do not withhold good. Generosity to the poor is a common theme in ancient Near Eastern wisdom literature. Typical is the following quote from the Egyptian “Instruction of Any,” but similar sentiments are found in the Babylonian Counsels of Wisdom, as well as the Egyptian “Instruction of Ptahhotep” and “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq”: “Do not eat bread while another stands by, Without extending your hand to him.”

4:4 he taught me. Throughout chs. 1–9 the father teaches his son. In the present discourse, we learn that the father himself was the recipient of teaching from his father. The family is thus the locus of wisdom teaching, but, then again, the family also provides the context for learning the law of God (Dt 6) as well as the meaningful events of the past (Ps 78:5–8).

4:9 garland . . . crown. The image of a marriage feast is given substance with the bestowing of the traditional symbols of union by the bride (wisdom) on her groom (protégé). In this case, marriage symbolism of the “glorious crown” (cf. Isa 61:10) could be compared with the fragrant bridal garments in SS 4:11. In the metaphoric sense, it could also be paralleled with Isa 28:5, where God becomes a “glorious crown, a beautiful wreath” for the Israelites.

4:17 the bread of wickedness . . . the wine of violence. The food and drink of the wicked are their very acts. Their evil sustains them. The metaphor of ingesting food and drink is used to indicate their deeply engrained wickedness. The “Instruction of Ptahhotep” uses similar language: “He lives on what others die on; distortion of speech is his bread; he is ‘a dead man who is alive every day.’ ”

4:23 heart. It is a common tradition in the ancient Near East for the heart to be the seat of the intellect (cf. 14:33) and the source of stability for one who would adhere to a just and wise life (cf. 1Ki 3:5–9). In Egyptian religious thought, the heart (ib) is distinguished from the soul (ba) and is considered the very essence of a person’s being. It is the heart that is weighed in the balance of truth when a deceased individual is examined by the gods Anubis and Thoth. The “Book of the Dead” provides spells to protect and strengthen the heart as preparation for this ordeal. In the Egyptian “Complaints of Khakheperresonb,” the main speaker dialogues with his heart, which is the center of his emotions, intellect and will. Indeed, one might recognize in this composition how the heart may well be described as the place from which everything flows, as in this verse.

In the ancient world, people had no knowledge of the physiology of the brain (and likewise no knowledge of the physiology of the kidney or liver). All of the functions that we associate with the brain, they tended to attach to the various entrails, the heart being most prominent among them because blood (the essence of life) obviously flowed through the heart, and a dead person’s heart stopped beating. Thus, the heart is the center of intellect, emotions, will and belief.

6:1 if you have put up security for your neighbor. A frequent theme covered by the book of Proverbs is advice pertaining to the giving of loans or the securing of debts (e.g., 11:15; 17:18; 20:16; 22:26; 27:13). The teaching is consistent: Do not give loans or secure debts. To understand this teaching, we need to put it in a broader context. In the first place, interest-bearing loans to fellow Israelites are forbidden (Ex 22:25). It was possible to give interest-bearing loans to foreigners (Dt 23:20), but if the word “stranger” (Hebrew zar) implies “foreigner” here, then even these types of loans are discouraged.

Ancient Near Eastern law collections (the Laws of Eshnunna and the Code of Hammurapi) have laws regulating the giving and receiving of loans. Ancient Egyptian wisdom literature (the “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq”) gives advice to borrowers and lenders alike. People are advised to borrow money at interest for real estate investment, marrying or celebrating special events, but not to raise their standard of living. Cautions about lending money include making sure that the lenders have obtained security and that they are careful not to trust too highly the one to whom they are lending money.

A text that specifically warns against becoming surety or a guarantor of another is found in the “Instructions of Shuruppak” (l. 19), where it is observed that if you become the guarantor for someone else’s loan, they will have some control over you.

6:6 ant. Examination of the creatures of nature provides both good and bad examples of behavior. The ant is proclaimed the paragon of hard work and foresightedness (cf. 30:25), storing food for the future. Yet another aspect of their character is noted in an Amarna letter, which states that the ant, despite its small size, is willing to defend itself when provoked.

6:9 you sluggard. See note on 12:24.

6:13 winks . . . signals . . . motions. This verse enigmatically talks about body language. It accuses those who wink their eye, signal with their feet and motion with their fingers of being scoundrels. While these gestures may simply be a sign of restlessness that results in bad behavior, another alternative is that they are related to ancient practices of sorcery, referring to ways of putting a hex on another person.

6:17 lying tongue. See note on 10:18.

7:3 tablet of your heart. See note on 3:3.

7:4 my sister. The reference to Woman Wisdom as “sister” must be understood in the context of ancient Near Eastern and Biblical love poetry (“my sister, my bride”; SS 4:9), where the “sister” is actually the beloved. In other words, the father encourages his son to make Woman Wisdom his lover, his wife. One Egyptian love poem begins: “One alone is (my) sister, having no peer: more gracious than all other women.”

7:8, 12 corner. Babylonian texts speak of small open-air shrines or niches on street corners or courtyards. One text says that there were 180 of them in the city of Babylon to the goddess Ishtar. Each of these shrines featured a raised structure with an altar on the top, and they seem to have been frequented primarily by women. In this sense, the word “corner” may refer to what is basically a cultic niche—a small, half-enclosed shrine where a small image would have stood.

7:13 brazen face. Compare the stance and attitude of the “brazen prostitute” in Eze 16:30. The Hebrew term here translated “brazen” is more often rendered as “strong” (e.g., Ps 52:7) or “oppressive” (e.g., Jdg 6:2), but it can also take on the connotation of impudence, i.e., to “put up a bold front” (e.g., Pr 21:29; Ecc 7:19). This latter translation fits the context of the adulterous woman who lies in wait for her victims and confidently invites them into her perfumed chambers. It also can be compared to the wife in the Code of Hammurapi who is “not circumspect” and “disparages her husband.”

7:14 fellowship offering. While some entertain the possibility that this type of offering is associated with a pagan ritual in which the woman engages in cultic prostitution as well as the offering of sacrifice, it is best to understand this offering in the light of Lev 3; 7:11–21. The fellowship offering is one that emphasizes communion between the worshiper and God, as well as between fellow worshipers. The meat must be eaten on the same day as the sacrifice. Therefore, it seems that the woman is trying to entice the man not only with her body but also with a delicious meal. Her acts accentuate the sinfulness of her behavior, adding the misuse of holy things (the sacrifice) to adultery.

7:16 colored linens from Egypt. One of the most important trade items produced in Egypt was linen (Eze 27:7). Royal and personal texts contain mention of its production from flax thread and its use as a medium of exchange or barter. One Eleventh Dynasty text (First Intermediate Period, about the time of the patriarchs) describes how a farmer used cloth woven from flax harvested on his land to pay rent. Colored cloth, which required the additional step of dyeing in its manufacturing process, would have been costly, and in the case of the adulterous woman it served as both a sign of wealth and as a brightly colored enticement to enter her chamber.

7:17 myrrh, aloes and cinnamon. These spices are familiar also in SS 4:14, where they describe the woman’s garden, a euphemism for her private sexual parts. These spices would have been imported from exotic places like Arabia and India.

7:23 arrow pierces his liver. Egyptian tomb paintings often depict the deceased noble hunting in the marshlands. Beaters frighten the fowl to break from cover, and in their terror a hail of arrows from the hunters unexpectedly meets them. The unsuspecting character of the adulterous woman’s victim suggests this same attitude of preoccupation or obliviousness to the real danger he faces. liver. Considered among the most vital organs, so is mentioned as the target here.

8:2 At the highest point. See note on 9:3.

8:3 the gate. A pivotal point in an ancient Near Eastern city. It was the place where people went in and went out of the city. It was a place where the elders met and commerce took place. In other words, it was a public location through which most of the inhabitants of the city would pass. Thus, someone, like Woman Wisdom, speaking near the gate would attract a substantial audience. See notes on Job 5:4; 29:7.

8:11 more precious than rubies. See note on 3:15.

8:12 I, wisdom. The rest of ch. 8 contains the autobiography of Woman Wisdom. We learn about her character and her actions. At the end (vv. 32–36), she gives advice to the “children” (v. 32) who listen to her. In form, this self-description followed by advice follows the structure of other fictionalized autobiographies known in Hebrew (the Teacher’s speech in Ecc 1:12–12:8), Akkadian (the Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin, the Adad-Guppi autobiography, and the Sin of Sargon text), and Aramaic (Words of Ahiqar) that end with advice.

8:15 By me kings reign. The idea that good kings are guided by wisdom may be found in the Historical Books of the Bible (see the description of Solomon in 1Ki 1–4) as well as in ancient Near Eastern texts. In terms of the latter, a few of the instruction texts are the advice of a royal father to his son and successor (e.g., “Teaching for Merikare”).

8:24 When there were no watery depths. This verse must be understood based on the background of ancient Near Eastern creation accounts that presume a primordial watery mass from which the dry land is separated. In Egypt, creation is thought to emanate from the Nun, or watery abyss (see note on Ps 104:5). In Mesopotamia and Canaan, the creator-god (Marduk and Baal, respectively) defeat the god of the sea (Tiamat and Yamm, respectively) and by bounding their waters create the dry land (see the articles “Baal,” “Chaos Monsters”). In Ge 1 the original mass, described as formless and void (Hebrew tohu wabohu), is a watery mass from which the dry ground is separated on the second day (see notes on Ge 1:2, 9; see also the article “The ‘Vault’ and ‘Water Above’ ”).

8:29 when he gave the sea its boundary. This language is reminiscent of the Babylonian Creation Epic, the Enuma Elish. After defeating Tiamat, the god of the sea, Marduk creates borders for her water, pushing it back in order to provide space for land (see the article “Cosmic Geography”).

9:1 seven pillars. Many theories have been put forward to explain the significance of the seven pillars of Wisdom’s house. Some interpret the significance of the number seven as indicating the seven planets known at the time; others take it as a reference to the seven creation days. However, the simplest and best explanation is to take the number seven in its typical symbolic sense, i.e., as indicating completeness. We are to picture a beautiful, large house. One ancient hymn to the god Enki (god of wisdom) may offer another connection of interest. A Sumerian hymn by Ishme-Dagan (Isin period, about 2000 BC) makes reference to seven-fold wisdom granted by Enki to the king.

9:3 highest point of the city. This location of Wisdom’s house is extremely significant to understanding whom she represents. In the ancient Near East, the only building allowed to occupy the acropolis is the temple. This does not divinize wisdom, but expresses that God is the source of wisdom.

9:8 Do not rebuke mockers. A similar insight concerning dealing with mockers is provided by the Egyptian “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq” (7.4–5): “Do not instruct a fool, lest he hate you. Do not instruct him who will not listen to you.”

9:14 highest point of the city. See note on v. 3. Surprisingly, Woman Folly’s house is also described as located at the highest point of the city, the location occupied by a temple in the ancient Near East. Thus Folly, like Wisdom, is associated with deity. In this case, she represents all the false gods and goddesses that attracted Israelites away from the true God. Thus, the choice between Wisdom and Folly is, among other things, a choice between true and false religion.

9:18 the dead. Here and 21:16 do not use the typical Hebrew word, but translate the Hebrew rephaim. In 2:18, the same Hebrew word is rendered “the spirits of the dead.” Though the Hebrew word is much discussed, there is little agreement about its exact meaning. In 2:18, since rephaim stands in parallel to death (mawet), there is no doubt that the rephaim are deceased persons. Outside of Proverbs, this Hebrew term is used in Job 26:5; Ps 88:10; Isa 14:9; 26:14, 19. This list omits occurrences in prose contexts, which raise other issues. The usual understanding of the rephaim as “shades” who dwell in the underworld seems correct, particularly in light of the Isaiah passages. See notes on Job 26:5; Isa 14:9.

10:4 Lazy hands. See note on 12:24.

10:5 gathers crops. Amenemope has similar advice, though expressed in connection with planting rather than harvesting, observing that plowing fields will result eventually in bread to eat.

10:6 Blessings . . . but violence. See the article “Retribution Principle.”

10:10 winks maliciously. The word “maliciously” is interpretive here, and the other occurrences of this phrase include both eyes, so winking is unlikely. This eye gesture may simply be a reference to a secret signal (see 6:13; 16:30). Some have further suggested that the gesture has a magical significance, like putting a hex on someone; see note on 6:13. An alternative is suggested by the Akkadian omen-wisdom that contains a series of omens related to the eyes. One of them asserts that if a person closes his eyes he will speak falsehood. It is uncertain whether this refers to frequent blinking, or squinting the eyes shut while talking.

10:11 fountain of life. As the Egyptian sage Amenemope states: abundant life is to be found in wise action and speech, but “fools who talk publicly in the temple are like a tree planted indoors,” which withers and dies for lack of light and is burned or cast away as trash. On the other hand, “the wise who are reserved are like a tree planted in a garden,” which bears sweet fruit, provides shade and flourishes “in the garden forever.”

10:18 lying lips. The sages roundly and frequently condemn false speech. Lies destroy relationships and cause all kinds of havoc. Proverbs is not alone in promoting truth in speech. Examples of similar teaching from the broader Near East advise not to speak falsely since that displeases the gods.

10:27 The fear of the LORD adds length to life. The idea that religious piety lengthens life may be found in other ancient Near Eastern texts, as illustrated by the Sumerian “Instructions of Ur-Ninurta”: “The man who knows fear of god . . . days will be added to his days” (lines 19, 26). But in the larger ancient world, this fear of god resulted in conscientious performance of ritual. Since the gods were believed to have needs, people who faithfully supplied those needs through ritual would be favored and protected, thus resulting in their long life. In contrast, Israelite faithfulness and fear of the Lord was demonstrated in covenant loyalty.

11:1 The LORD detests. See note on 15:8. dishonest scales. The scale described here was composed of two plates suspended from a bar of some sort. On one plate was a premeasured weight (lit. “stone” [Hebrew eben]), over against which the product would be balanced. Such a system could be fraudulently manipulated in a variety of ways, including falsely labeling the weight. The language of the proverb echoes legal portions of the Pentateuch (Lev 19:35–37; Dt 25:13–15) as well as prophetic indictments relating to justice (Eze 45:10; Hos 12:7–8; Am 8:5; Mic 6:11). The “Instruction of Amenemope” commits two chapters condemning the practice of altering weights, and the Babylonian “Hymn to Shamash,” the god of the sun and justice, condemns those involved in fraudulent practices connected to weights and balances.

11:2 pride. The late Egyptian Papyrus Insinger says this about those with excessive pride: “There is he who is arrogant, and he makes a stench in the street” (27.17). Pride was often the result of a sense of self-importance. The cultures of the ancient world found greater value in the community and the clan than in the individual, so the vaunting on oneself was considered a negative trait.

11:11 Wisdom has social repercussions, as does folly, since it is identified with wickedness in Proverbs. Wisdom (the result of order and the fear of the Lord) brings joy to the city, because it unites people and they prosper. Folly (the result of disorder) brings grief, because it tears people apart and they languish. The Assyrian sage Ahiqar agrees with this, though his Saying 75 speaks to only the latter point: “[The city] of the wicked will be swept away in the day of storm, and its gates will fall into ruin; for the spoil [of the wicked shall perish].”

11:12 holds their tongue. See note on 12:13; 29:20.

11:13 gossip. Those who speak ill about others behind their backs in order to ruin their reputation are fools according to Proverbs, and they will come to a bad end, since they fracture the structure of society. Ptahhotep refers to gossip as the “spouting of the hot-bellied.”

11:15 puts up security for a stranger. See note on 6:1.

11:20 The LORD detests. See note on 15:8.

11:29 will inherit only wind. Those who disturb the tranquility of their family will have no prosperity. A similar thought is expressed in a Sumerian proverb: “An unjust heir who does not support a wife, who does not support a son, is not raised to prosperity.” On the flip side of the same truth, Ankhsheshonq advises: “Serve your mother and father, that you may go and prosper.”

11:30 tree of life. See note on 3:18.

12:13 trapped by their sinful talk. Proverbs frequently teaches that foolish speech has dire consequences and inevitably results in disorder. In some proverbs, as here, the nature of the speech is not specified, but on other occasions it is described as lying, gossip, slander, rumor and other socially destructive behaviors. Egyptian sages also recognized the connection between evil speech and negative results. A good example is from Any: “A man may be ruined by his tongue, Beware and you will do well.”

12:17 false witness. See note on 10:18 for lying in general. The Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” specifically condemns falsehood (perjury) in the courtroom.

12:19 lying tongue. See note on 10:18.

12:22 The LORD detests. See note on 15:8. lying lips. See note on 10:18.

12:24 Diligent hands . . . but laziness. One of the single most important themes in the book of Proverbs contrasts lazy people with the diligent. The sages considered laziness a preeminent type of folly that results in destitution. In a culture in which one’s contribution to the community and clan were of great importance, laziness was among the greatest of flaws. Indeed, the Biblical sages are often at their satirical best when describing the lazy in bed like a door turning on its hinges (26:14) or refusing to go outside for fear of being attacked by a lion (26:13). rule. Hard workers will find themselves in positions of importance, and the lazy will be their slaves. The Egyptian “Instruction of Any” states the same principle: “He who is slack amounts to nothing, Honored is the man who’s active.”

12:25 Anxiety weighs down the heart. Worry debilitates a person. It can lead to depression and even illness. The Egyptian Papyrus Insinger observes that worry can lead to sickness or even to death. The Biblical proverb here looks to the “kind word” as an antidote, though the Israelites would not have disagreed with the Egyptian text that reminds that the god gives patience to the wise, while the ungodly are left to their own resources and flounder.

12:27 lazy. See note on v. 24.

13:3 guard their lips. Self-control in speech is a highly desired trait according to both Biblical and Egyptian sages. A narrative example of how careful speech comes to a person’s aid may be observed in the Egyptian tale of the “Eloquent Peasant,” in which an uneducated man comes before the king to make a plea for a favorable judgment and acquits himself so well in his speech that his request is granted.

13:4 sluggard’s. See note on 12:24.

13:12 tree of life. See note on 3:18.

13:17 wicked messenger. Government, military, commerce, and even personal communication all depended on messengers. While writing letters was known in the ancient world, much communication took place orally. In the case of written letters or oral communications, the delivery depended on messengers (see note on Ge 16:7). A wicked messenger would be one who did not deliver the message, lost it or delayed its reception. In the case of an oral message, a wicked messenger might forget what to say or even intentionally change the message from what its author desired. Ankhsheshonq gives advice as to the type of person to send on a particular job: “Do not send a low woman on a business of yours; she will go after her own. Do not send a wise man in a small matter when a big matter is waiting. Do not send a fool in a big matter when there is a wise man whom you can send.”

13:20 companion of fools. The sage realizes that one’s peers exercise tremendous influence on a person. If one falls in with evil people, then it is likely that that person will do evil themselves (1:8–19). On the other hand, associating with the wise provides good role models, as well as excellent instruction. The “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq” observe that if you befriend a fool, you are a fool, but it is wise to befriend a wise person.

13:24 rod. There was a real concern in ancient legal (e.g., Sumerian Law Code; Ex 20:12) and wisdom writings to teach children to honor and obey their parents. For instance, the Assyrian sage Ahiqar makes the familiar statement that to “spare the rod is to spoil the child.” He also notes that those “who do not honor their parents’ name are cursed for their evil by Shamash, the god of justice.” The parents’ responsibility for their children is also a concern. The Egyptian “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq” points out that “the children of fools wander in the streets, but the children of the wise are at their parents’ sides” (compare the legal injunction regarding the rebellious son in Dt 21:18–21).

14:5 false witness. See notes on 10:18; 12:17.

14:11 house of the wicked. See note on 11:11.

14:19 bow down . . . at the gates. In this instance, gates refer to the household gates of the righteous, not the city gates (compare the obeisance of the king’s servants at the king’s gate in Est 3:2). In that sense, therefore, the parallelism of the verse indicates that the evil doers will be forced to show subservience to the righteous, becoming their servants. A similar case in which due respect is granted by those who had previously taken no notice of their “new masters” is found in Moses’ prediction in Ex 11:8 that the Egyptian officials would “bow low to me.”

14:23 hard work. See note on 12:24.

14:25 false witness. See note on 12:17.

14:31 Whoever oppresses the poor. Ptahhotep also instructs his reader not to engage in exploitation of the poor by attacking him just because he is weaker. Amenemope adds that any benefit you may gain will be less than satisfying.

15:1 turns away wrath. In the “Instruction of Any,” it is understood that gentle words lead to peace, while a harsh word just makes things worse.

15:4 tree of life. See note on 3:18.

15:8 The LORD detests. Lit. “abomination of the LORD.” This Hebrew phrase occurs frequently in the book (here; vv. 9, 26; 3:32; 6:16; 11:1, 20; 12:22; 16:5; 17:15; 20:10, 23) and indicates the utmost divine censure against something. The intention of describing actions or attitudes that are an abomination to the Lord is to advise strongly against them. We have a similar phenomenon in the Sumerian proverbs that describe various actions such as serving beer with unwashed hands as an abomination of the sun-god Utu.

15:11 Death and Destruction. Hebrew “Sheol” and “Abaddon,” names that relate to the grave and the netherworld (see the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld”). For Death (Sheol), see note on 1:12, where the same Hebrew word is translated “grave.” Abaddon is clearly a derivative of the Hebrew verb abad (“to destroy”) and in parallel with Sheol stands for the place of destruction, though the nature of the destruction is never specified, and is another name for the grave and the netherworld. The NIV rightly capitalizes the words, because here they are personified. In this way, the proverb is reminiscent of Canaanite mythology, where Death is represented by the god Mot, who at one point in the mythic narrative overwhelms even Baal, the chief god of the pantheon. The Biblical text is not saying that a god like Mot actually exists. Even though Baal ultimately is revivified, the Biblical proverb shows the Lord’s superiority when it says that Death and Destruction lie open before him. Personification, treating an inanimate object or a concept as if it were animate, must be carefully differentiated from identification—i.e., death can be personified without actually being identified as a personal entity.

15:16 Better . . . than. Proverbs uses the “better-than” proverb form in order to express relative values. While wealth is considered a good thing, and even a gift of Yahweh when acquired honestly, it is not the most important thing by far. If a decision must be made between wealth or a right relationship with God, or between having much or having love and peace, then the latter of each pair is far better. See 16:16. Amenemope expresses a similar value also using the better-than form as he contrasts poverty in the hand of God as better than great stores of wealth.

15:17 Better . . . than. See note on v. 16. vegetables . . . a fattened calf. Most people in the ancient world did not have meat as a regular part of their diet. Grains and vegetables were the subsistence foods. This verse refers to greens and contrasts them to the most luxurious of meals (a “fattened calf” was used only in great celebrations or cultic contexts). The teachings of Amenemope also use this type of saying: “Better is a single loaf and a happy heart than all the riches in the world and sorrow.”

15:18 This proverb contrasts the hothead and the calm person. Egyptian wisdom uses this dichotomy almost as often as Biblical proverbs use the distinction between the wise and the foolish. So, e.g., Amenemope warns against befriending the hothead, and Any warns against provoking conflicts, which can be accomplished by exercising patience rather than provocation.

15:19 sluggard. See note on 12:24.

15:23 timely word. Timing is everything in the world of wisdom. One must know the proper time to say the right thing. Ankhsheshonq puts it this way: “Do not say something when it is not the time for it.”

15:24 realm of the dead. The Hebrew word for this phrase is translated “grave” in 1:12 (see note there).

15:25 boundary stones. See note on 23:10.

15:26 The LORD detests. See note on v. 8.

15:28 mouth of the wicked gushes evil. See note on 29:20.

16:2 motives are weighed by the LORD. Here human self-perception is judged in the light of the Lord’s perception. The proverb speaks to our ability to deceive ourselves concerning our righteousness. Proverbs often denigrates those who are wise in their own eyes (3:7; 12:15; 26:5, 12; 30:12). The observation invites profound reflection on our motives, since God is the final arbiter of whether a path is right or wrong. This is not a function of human beings. An analogy exists between Yahweh measuring (or weighing) the “spirits,” and the Egyptian god Thoth weighing the heart of the dead person against the balance of Ma’at (truth and justice) in order to determine whether the deceased will enter into the afterlife.

16:5 The LORD detests. See note on 15:8.

16:8 Better . . . than. See note on 15:16.

16:9 plan their course. See note on 19:21.

16:10 oracle. The Hebrew (qesem) is a word that is usually connected with divination. Thus, the proverb is hard to understand, because of the apparently positive reference to it on the lips of the king. Qesem is frequently condemned in other parts of the OT (e.g., Dt 18:10; 1Sa 15:23; 2Ki 17:17), because it is associated with pagan divination practices. Nonetheless, there are positive instances of divination elsewhere in the OT (though, admittedly, the word qesem is not found in these contexts), most notably in the use of the Urim and Thummim (see the article “Urim and Thummim”). Without a fuller context, it is difficult to determine with precision how qesem is used here. It was the priests, e.g., who manipulated the Urim and Thummim, but perhaps the king was the one who was responsible for announcing the decision (cf. 1Sa 23:1–8). If so, then perhaps the issue of justice concerns a proper presentation of the oracular decision that would have come from God. It further could point to a legal context for such an oracular decision. The temptation might be for the king to hedge the decision in the interests of his own policies, and thus the statement could also be understood as a kind of warning or prohibition. The wise king will not pervert the legal verdict rendered by the divinely inspired lot. See the articles “Magic,” “Practice of Magic.”

16:11 Honest scales. See note on 11:1.

16:14 The sage warns against provoking a king. After all, the king has the power of life and death. The Tale of Ahiqar begins with a narrative about how the Assyrian king orders the death of Ahiqar, his wise man, based on the anger instigated by a false report filed by Ahiqar’s nephew Nadin. His observations about the danger in angering a king come from his own personal experience.

16:16 better . . . than. See note on 15:16.

16:28 gossip. See note on 11:13.

16:33 lot. The last proverb of ch. 16 returns to a theme from the beginning of the chapter (vv. 1–3, 9). The point is that God is the final arbiter of the future. Human beings may attempt to find out what the future holds, but they should know that it is God who determines it. The OT approved at least one type of divination, the Urim and Thummim, and the principle behind this proverb certainly applied to it. The reason why the determinations of the Urim and Thummim were followed by leaders like David (1Sa 23:1–6) is because it was known that God determined what they would indicate (see the article “Urim and Thummim”). See also the NT use of lots in Ac 1:26. Careful study of Greek and Akkadian lot casting, as well as a close look at associated verbs, leads to the conclusion that lots are placed in a receptacle and then shaken until one comes out. Typically such lot casting was done before a deity.

17:1 Better . . . than. See note on 15:16.

17:3 The crucible for silver and the furnace for gold. Gold and silver may be refined in a graphite crucible. Gold melts at a temperature of 1,948°F (1,064°C) and sterling silver at 1640°F (893°C). An additional 338°F (170°C) is necessary to allow the metal to be poured without freezing, but it also cannot be so hot that a destructive crystalline structure forms or alloys are dissipated before the metal cools. It is also important to avoid oxygen infiltration as much as possible during the melting process so that the structure of the metal will not become porous. The refining process requires expertise and an intimate knowledge of the tools and metals involved. As such it is an apt metaphor for God’s testing of the heart (compare the “weighing of the heart” in the judgment of the soul in Egyptian religious tradition; see the article “The Hardening of Pharaoh’s Heart”).

17:5 Whoever mocks the poor. Some proverbs mock the lazy who end up poor (6:6–11; 10:4–5), but it is their slothfulness that is being ridiculed, not their poverty. Proverbs is aware that there are other reasons, including social injustice, that lead to poverty (e.g., 13:23). We can cite similar ideas from the ancient Near East. Amenemope warns not to laugh at the blind or the lame. In the same vein, in Mesopotamia it was considered wrong to sneer at the unfortunate or those who were downtrodden.

17:6 children are a crown to the aged. Descendants are a blessing to parents and grandparents. The “Instruction of Any” express a similar idea: “Happy is the man whose people are many, he is saluted on account of his progeny.”

17:8 bribe. See note on v. 23.

17:15 the LORD detests. See note on 15:8.

17:17 friend. See note on 27:10.

17:23 bribes. The teaching of Proverbs about bribes at first seems contradictory. A number of passages, including the present one, are negative about bribes. Similarly, Amenemope commands: “Don’t accept the gift of a powerful man, And deprive the weak for his sake.” However, other passages in Proverbs suggest that bribes are acceptable and even advisable (e.g., 18:16). Just like with a timely word, it depends on the circumstance. If a bribe is used to circumvent justice, then it is evil. If the bribe is used to open doors for a good purpose, then it is appropriate.

17:27 uses words with restraint. The wise know how to use words appropriately and with great self-control. They know that speaking too much will lead to trouble. The wisdom of the ancient Near East shares this understanding as it paints a picture of the wise person as one who knows when to be silent. Ptahhotep, e.g., advises that silence is better than chatter and that one should only speak up when they have something positive to contribute.

17:28 keep silent. See note on v. 27.

18:8 gossip. See note on 11:13.

18:9 slack. See note on 12:24.

18:16 gift. See note on 17:23.

18:18 Casting the lot. See note on 16:33.

19:5, 9 false witness. See note on 12:17.

19:11 it is to one’s glory to overlook an offense. If one is offended, he has two choices: (1) confront the offender or (2) ignore the offense. The latter is recommended. If a person acts as if an offense has not happened, then there will be no further provocation or conflict. In maxim 29, Ptahhotep teaches the same strategy of being willing to overlook an offense.

19:12 king’s rage. See note on 16:14.

19:15 Laziness. See note on 12:24.

19:18 Discipline your children. See note on 13:24.

19:21 LORD’s purpose. According to Proverbs, human beings should make plans for the future, but they should do so with the awareness that their plans may be overridden by God’s purpose. Such an attitude engenders humility. This is also a well-attested teaching in ancient Near Eastern wisdom, as exemplified by Amenemope who observes that human words are one thing, but the deeds of god may go a different direction.

19:28 corrupt witness. See notes on 10:18 and 12:17.

20:1 beer a brawler. Beer and strong drinks are ancient beverages. We know that both Egyptians and Mesopotamians produced alcohol. Indeed, we have beer recipes and even a hymn to the beer god from the latter. In Israel wine was the beverage of choice. Beer was not popular perhaps due to the lack of natural resources to make it readily available. Wisdom literature urges against over-consumption. To exercise wisdom, one must be in possession of all one’s faculties and alcohol tends to blur one’s senses and one’s judgment. Thus, Ankhsheshonq puts it plainly and even advises that Pharaoh’s business should not be discussed when drinking beer. But Any has the most extensive teaching. In his instruction he notes the consequences of drunkenness including evil speech, unawareness of what you are saying, possibility of injury when you fall, and rejection by friends who find you in a drunken stupor.

20:2 king’s wrath. See note on 16:14.

20:4 Sluggards. See note on 12:24.

20:10 Differing weights . . . measures. See note on 11:1. the LORD detests. See note on 15:8.

20:13 Do not love sleep. See note on Job 22:6.

20:16 Take the garment. See note on 27:13.

20:22 Wait for the LORD. When people are hurt or offended, often the first reaction is to seek revenge. This desire often increases the offended person’s anxiety and if successful may well trigger a cycle of hurt, as each party tries to get the best of the other. This proverb recommends a better way: let it go, and expect that God will take care of the situation. Christian readers will recognize the same idea behind Paul’s teaching: “Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: ‘It is mine to avenge; I will repay,’ says the Lord” (Ro 12:19). The “Instruction of Any” has similar advice; he recommends that you leave your attacker in the hands of the deity.

20:23 differing weights. See note on 11:1.

21:1 channels. In the ancient Near East, irrigation ditches were dug to extend a river or lake’s capability to fertilize soil. These were human-made channels that directed the water to where people needed it. It represents power and control over the use of water. To say that the king’s heart is “a stream of water that [the LORD] channels” indicates that the Lord is in control of even the most powerful human beings on earth.

21:2 the LORD weighs the heart. See note on 16:2.

21:6 lying tongue. See note on 10:18.

21:9 corner of the roof. The “better-than” sayings provide a contrast or extreme that is preferable to contact with evil or with the disagreeable. The corner of a roof or a cramped attic chamber (see 1Ki 17:19) would be an uncomfortable perch, but its dangers or its inaccessibility might ward the sufferer from an even more unpleasant contact with a nagging wife (Pr 21:19; 25:24).

21:14 gift. See note on 17:23.

21:16 the dead. See note on 9:18.

21:17 whoever loves wine and olive oil will never be rich. Proverbs gives many reasons for poverty: laziness (12:24), injustice (13:23) and now overindulgence. The Egyptian sages noticed the same connection and Papyrus Insinger observes that the glutton runs the risk of poverty.

21:28 false witness. See note on 12:17.

22:1 more desirable than . . . better than. See note on 15:16.

22:9 generous. See note on 3:27.

22:15 Folly is bound up in the heart of a child. Ankhsheshonq agrees that the natural disposition of youth is wickedness: “When a youth who has been taught thinks, thinking of wrong is what he does.” For the idea that the young require physical discipline to grow wise, see note on 13:24.

22:18 keep them in your heart. This is not the usual Hebrew word for heart. The Hebrew word here is beten rather than leb, and it is more naturally translated “belly” or “stomach.” The NIV appropriately translates the word in an idiom that modern English readers will understand, but by doing so it obscures the connection with Amenemope’s observation that when sayings of the wise are kept in your belly, they stand as a doorpost to the heart.

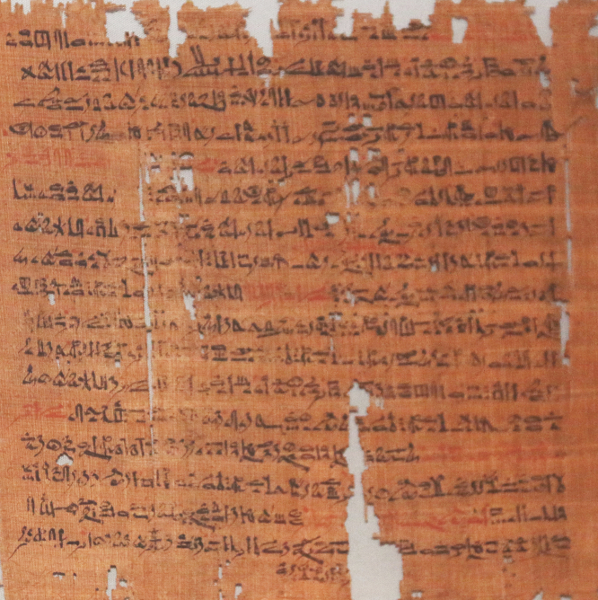

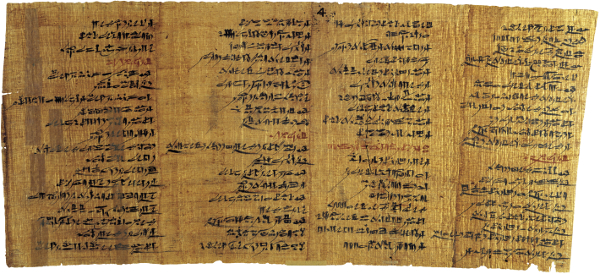

22:20 thirty sayings. A portion of the book of Proverbs (22:17–24:22) seems to imitate, at least in part, the literary structure of the Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope.” Amenemope contains 30 chapters following a lengthy prologue. This fact has encouraged Bible translators to make a minor emendation to the Hebrew text from a word that means “formerly” (shilshom) to the word that means “thirty” (sheloshim). There is some dispute among scholars on the identification of the 30 units within the Biblical text, since there are breaks in the sections that may indicate unrelated segments (see “my son” diversions at 23:15, 19, 26). Also against the connection, the NIV had to slightly emend the text to arrive at 30, and had to provide the noun sayings so that there would be something that there were 30 of. Beyond this difficulty is the fact that the 30 sections in Proverbs would each be only a few verses long (4–6 lines), while the 30 chapters in Amenemope average 12–16 lines in length. The closest parallels between Amenemope and Proverbs come to an end at 23:11, and the remaining units have close ties to other pieces of wisdom literature, including the Words of Ahiqar. This may indicate a general familiarity with Amenemope and other wisdom literature, but a measure of literary independence on the part of the Biblical writer or wisdom school.

22:22 Do not exploit the poor. See note on 14:31.

22:24 a hot-tempered person. Amenemope also counsels avoidance of a hothead.

22:26 shakes hands in pledge. See note on 6:1. Shaking hands on an agreement is not attested clearly in the ancient Near Eastern texts or iconography. The nearest portrayal from the ancient Near East can be seen on the relief on the throne dais of Shalmaneser III, where the king and his vassal Marduk-zakir-shumi look like they are shaking hands, though here it seems to be a gesture of submission.

22:28 boundary stone. See note on 23:10.

22:29 This proverb states that those who work hard and with skill will succeed in their careers. They will work for the most powerful and influential people in society, while those who are not diligent will spend their careers working for people on the lower end of the social stratum. We might compare a statement found in the final chapter of Amenemope in which a skilled scribe is seen to be worthy of promotion in the court.

23:1 When you . . . dine with a ruler. Egyptian wisdom texts often have rules concerning etiquette that give warning to the dangers of dining in the presence of a powerful superior. These include being content with what is set before you and exercising restraint (especially regarding favorite food).

23:4–5 This saying is often taken to be the closest to its parallel in the “Instruction of Amenemope,” which advises people to be content with the wealth they have; anything that is gained illegitimately will quickly be gone. Though the Egyptian text is more extensive than the saying here, the similar sentiment, as well as the image of the flying bird to capture the idea of the transience of wealth, is striking. Even with these parallels, it is by no means definite that any kind of direct borrowing was involved in the composition of either piece. One could imagine that the proverbs developed independently or that both texts are dependent on another, yet unknown text or texts.

23:10 boundary stone. In the ancient Near East, stones were used to mark property boundaries. Archaeology has revealed Mesopotamian boundary stones (known as kudurru), on which inscriptions indicate ownership. To move a boundary stone was to steal land and was strictly forbidden.

23:13 This proverb encourages parents to exercise physical discipline on young children in order to move them from their natural state of folly (see 22:15 and note) to wisdom. The same idea is found in Words of Ahiqar, Saying 4, but it is addressed directly to the son: “If I beat you, my son, you will not die; but if I leave you alone, [you will not live].”

23:21 drunkards and gluttons become poor. See notes on 20:1; 21:17.

23:29 Who has bloodshot eyes? See note on 20:1.

23:30 mixed wine. The alcoholic potency of the wine, normally mixed with water, is enhanced with the addition of honey or pepper to create a type of “spiced wine.” As in 20:1, the fool is the one who overindulges in wine. Drunkenness runs counter to the wisdom tradition. For instance, the Greek custom of the “symposium,” or drinking party, regulated the amount of wine consumed, so that rational discourse was possible and a general atmosphere was maintained in which the celebrants could freely release their cares and display their talents in song and poetry.

23:31 Do not gaze at wine when it is red. It is not clear whether there is some fascination with the color red that was thought to be a further inducement to overindulge in strong drink (as is suggested by the reading of the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) or whether there is a translation problem. sparkles . . . goes down smoothly. The sparkling nature of the wine may indicate a particularly potent vintage that is smooth to the palate (see SS 7:9) or it may be related to a term for wine in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle. The Egyptian “Instruction of Any” likewise includes warnings that drunkenness leads to careless speech, bodily harm, rejection by friends and loss of senses.

24:13 honey . . . honey from the comb. The wisdom writer here follows a tradition found in both Ps 19:10 and Eze 3:3 in which God’s words/laws are equated with wisdom and are therefore to be desired, much like one desires the sweetness of honey. In most OT texts, honey represents a natural resource, probably the syrup of the date rather than bees’ honey. Evidence of bee domestication in Israel has been found at Tel Rehov, and both Hittites and Canaanites used bee honey in their sacrifices. In the Bible, honey occurs in lists with other agricultural products (2Ch 31:5). Here the reference to the honeycomb specifies the product as bees’ honey. Note also that honey from the comb would be the freshest and tastiest kind. Akkadian texts also use honey figuratively as they speak of praise being sweeter than honey or wine.

24:28 Do not testify against your neighbor without cause. See note on 12:17.

24:29 I’ll pay them back for what they did. See note on 20:22. Amenemope also teaches against vengeance and urges responding with silence and patience for the god to respond.

25:1 men of Hezekiah. This is the fifth section title (see also 1:1; 10:1; 22:17–21; 24:23) within the book. It begins another section of Solomonic proverbs (implying that what comes before is not Solomonic) that continues through the end of ch. 29, but this time, others are said to be involved. The mystery of the verse has to do with the nature of the involvement of the men of Hezekiah. It is likely that, along with other acts of reform and renewal of worship following the destruction of the northern kingdom in 722 BC, Hezekiah also initiated more care in the transmission of sacred literature. National crisis is a time for reflection, and perhaps Hezekiah attempted to gain God’s favor by having traditional wisdom sayings recorded and disseminated (compare the Words of Ahiqar, a guide to proper behavior, presented to the king of Assyria as a means of his returning to royal favor). However, the rather general reference to “men of Hezekiah” does not allow us to be more specific in identifying who exactly they are. The text suggests that Hezekiah had court-sponsored sages who gathered and compiled wisdom sayings.

25:4 dross. Impurities removed during the refining process. See note on 17:3.

25:8 do not bring hastily to court. Amenemope also advises against bringing a charge too quickly, especially if the evidence is not strong.

25:9 do not betray another’s confidence. According to Proverbs, such an act will ruin one’s reputation. This principle is similar to that of one saying in the Words of Ahiqar that advises that if you reveal secrets to your friends, your reputation as one being able to hold confidences will be ruined.

25:11 apples of gold in settings of silver. The writer here uses the simile of a finely worked piece of jewelry, whose craftsman has been able to balance a golden piece of fruit amidst an intricately designed silver setting. The delicacy of this decorative device draws the eye, just as a right ruling or a clever saying touches the mind. apples. Some have suggested that the fruit named here is an apricot rather than an apple, but it makes no difference to the imagery.

25:13 messenger. See note on 13:17. Good messengers bring relief to those who send them, just like a cool drink brings relief to those who harvest during the hot spring and late summer months.

25:14 gifts. See note on 17:23.

25:18 false testimony. See note on 12:17.

25:22 heap burning coals on his head. The “Instruction of Amenemope” also advises the wise person to shame fools or their enemies by pulling them out of deep water and by feeding them one’s bread until they are so full that they are ashamed. Similarly, the “Precepts and Admonitions” in Babylonian wisdom literature states that the wise man should not “return evil to the man who disputes with you” and should, in fact, “smile on your adversary.” This is surely the direction this proverb goes, but the metaphor of heaping burning coals on the head remains elusive. Cultural phenomena that may offer some explanation include the following: (1) There was an Egyptian ritual (mentioned in a late demotic text from the third century BC) in which a man apparently gave public evidence of his penitence by carrying a pan of burning charcoal on his head when he went to ask forgiveness of the one he had offended. (2) In the Middle Assyrian laws there is an example of a punishment in which hot asphalt was poured on the offender’s head. Both of these have difficulties. The first is in a late text and the action referred to has been variously interpreted. The second is hot tar, not coals, and is a punishment much like tarring (and feathering) in more recent history. At this point, no ancient texts help clarify the imagery used here.

25:23 north wind. In Israel, a north wind typically brings fair weather, not rain, hence the sense of something unexpected happening. But some scholars have suggested that this proverb had its origin in Egypt, where the north wind does bring the rain off the Mediterranean (5–10 inches [12–24 centimeters] per year in the delta).

25:24 corner of the roof. See note on 21:9.

26:1 snow . . . rain. Snow never occurs in the summer in Israel, and rain is an extremely rare event during the harvests of spring and summer. The Mediterranean climate of Syria and Canaan brings rain and cooler temperatures (below freezing in the higher elevations, as at Jerusalem) during the winter months (Oct. to Feb.) and the remainder of the year is dry, with only an occasional shower. Thus, this statement is like many in ancient wisdom literature (e.g., Amenemope and Ankhsheshonq) in which the fool is described as “unteachable” and dishonorable. As Ahiqar notes, there is no point in sending the Bedouin to the sea, as it is not his natural habitat.

26:6 Sending a message. See note on 25:13.

26:13 sluggard. See note on 12:24.

26:16 seven people. It has been suggested that this is a reference to the famed seven sages (referring to either the apkallu or the ummanu) that brought civilization and wisdom to the world in Mesopotamian lore. The seven apkallu came before the flood, and the seven ummanu, the counterparts of the apkallu, came after the flood. This is possible, but one would expect a definite article (“the seven”) if it were the case.

26:22 gossip. See note on 11:13.

26:23 coating of silver dross. While a glaze may be applied to pottery as decoration, it may also hide flaws and thus cheat the one who purchases the pot. Similarly, a coating of silver dross, made of adulterated, oxidized metal, may initially look good, but will quickly tarnish or flake off. Thus the “fervent” (or “smooth” [see NIV text note]) lips of a scoundrel may attempt to cover his hatred and malice with deceitful words.

26:24 lips . . . hearts. An Akkadian proverb draws the same distinction, observing that a man may speak friendly words with his lips, but have a heart full of murder. The incantation series Shurpu speaks of one whose speech is straightforward, but whose heart is devious.

27:9 Perfume and incense. Various pungent scents were part of the Israelite’s everyday life. Perfumes were concocted and incense burned to cover some of the more offensive smells, to enhance one’s sexual attractiveness (e.g., Est 2:12; SS 1:12; cf. thirteenth-century BC Egyptian Love Songs), and to serve as an offering to God (Ex 30:34–38). Among the most common were frankincense, myrrh, saffron and mixtures of cinnamon, cassia and olive oil (see notes on Ps 45:8; 133:2; SS 3:6). Such a pleasant fragrance is an apt parallel with a friend’s wise advice, since a person’s wise counsel makes it desirable to be around them, just as pleasant aromas would.

27:10 do not go to your relative’s house. While some proverbs suggest that a friend is equivalent to a relative in an emergency and that both will prove helpful (17:17), the present proverb actually prefers a neighbor over a relative at such a time. Perhaps the explanation is that friends are associated with a person by choice and affection, whereas a brother has no say. However, still, one might think that particularly in an ancient society a relative would help even if they did not like the person. Perhaps the key to understanding this verse is the last line, which mentions that the relative lives at a distance. Perhaps the friend is someone close and the brother far away. But, again, ancient society was not as mobile as modern society, so one wonders how often relatives would be split by such great distance. In any case, such a thought is not without parallel in the ancient Near East, since Ankhsheshonq advises that is it preferable to go to a friend rather than a brother when there are difficult circumstances. Sometimes relationship with a relative can be rancorous or antagonistic, and some relatives (e.g., a brother) might even have vested interests to be realized should you be ruined or die.

27:20 Death and Destruction. See note on 15:11.

27:21 crucible . . . furnace. See note on 17:3.

28:6 Better . . . than. See note on 15:16.

28:8 interest or profit. Charging interest to fellow Israelites was against the law (Ex 22:25; Dt 23:20). It was lawful to charge interest to non-Israelites, but nothing in this proverb indicates that that is in view. While there are no other cultures that evidence interest-free loans, ancient law codes like the Code of Hammurapi do regulate the amount of interest that a creditor may charge.

29:11 Fools give full vent to their rage. Uncontrolled anger can be extremely destructive, even if it is justified by an attack of some sort. If a person does not guard the expression of their anger, then it can harm them even further. Papyrus Insinger also counsels a watch over one’s anger, observing that great anger creates a stench around a person.

29:17 Discipline your children. See notes on 13:24; 23:13.

29:19 Servants cannot be corrected by mere words. The sages operated by the principle that wisdom was not an inherent human quality—to the contrary, they considered the fear of the Lord the beginning of wisdom. Their teaching implied that people in their natural state were naive or foolish and that it took work to become wise. They also taught that some people were harder to educate than others. Here, we see that “servants” were thought by the wise to be particularly difficult to train. It was not that they were not intelligent enough to understand intellectually what they were being told. The second line affirms that they do understand but says that they do not respond. This likely indicates a lack of desire to carry out the commands of the master. It appears that they needed something more to motivate them (perhaps fear of the rod? [see note on 13:24]). Papyrus Insinger makes a similar point, observing that the servant will only obey if the master has some means of discipline at hand.

29:20 someone who speaks in haste. Proverbs often warns against speaking too hastily. One should think before speaking, rather than impulsively blurting out the first thing that comes to mind. Ankhsheshonq warns against blurting out whatever comes to mind. Ptahhotep advises deliberation in speech to ensure that what is said matters.

29:23 Pride. See note on 11:2.

30:1 Agur son of Jakeh. We know nothing further about this man, since neither he nor his father, Jakeh, are mentioned anywhere else. We also know nothing about Ithiel and Ukal (see NIV text note), who are named as the recipients of Agur’s wisdom. Indeed, there are questions about the proper translation of some verses in Pr 30. inspired utterance. The Hebrew word may alternatively identify the tribe from which Agur comes (“Massa”). This may then be connected to the name of a tribe in Arabia related to the Ishmaelites mentioned in Ge 25:14; 1Ch 1:30. If so, then we have here the words of an Arabian wise man.

30:8 Keep falsehood and lies far from me. See note on 10:18.

30:16 the grave. See note on 1:12. the barren womb. If a woman could not have a child, the consequences were dire. Even today, couples are often saddened by an inability to have children, but in antiquity the stakes were even higher. After all, who would take care of an aging couple if there were no children? A widow without sons would be particularly vulnerable in a patriarchal society without social structures like health plans or nursing homes. One need only think of the anxieties surrounding childbirth in the Genesis patriarchal narratives (e.g., Ge 30:1) to get a sense of the issue. It was also not uncommon in the ancient world to believe that one’s felicity in the afterlife was dependent on care by those who were still in the land of the living. Thus, barrenness destined one to continued difficulties in the afterlife.

30:21–23 This numerical proverb describes a topsy-turvy world. Similar negative thoughts about a topsy-turvy world may be found in the Admonitions of Ipu-Wer and apocalyptic texts like Isa 24:2 and the Akkadian Marduk Prophecy and Shulgi Prophecy. All of these portray a situation in which order has been disrupted, and we should recall that order is what wisdom pursues in the ancient Near East.

31:1 King Lemuel. As with Agur (see note on 30:1), we have no Biblical or extra-Biblical mention of such a king. inspired utterance. As with Agur, this Hebrew term may be a reference to the king’s tribal affiliation (see note on 30:1). If Lemuel is from the tribe of Massa, then he would be an Arabian leader. mother. Note that it is his mother who teaches him here (see note on 1:8). The fact that this is a royal instruction, i.e., from a queen to her son, makes it similar to the Egyptian “Instruction of King Amenemhet” and the “Teaching for Merikare,” as well as the Akkadian Advice to a Prince, though in the latter the teacher is the queen mother.

31:4 not for rulers to crave beer. See note on 20:1.

31:10–31 The book of Proverbs ends with an extensive description of the “wife of noble character” (v. 10). As we read this description, we see that it recapitulates much that has been said earlier about the good wife as opposed to the evil woman (5:15–20; 12:4; 18:22). Furthermore, if we read this description in the light of what was earlier said about the Woman Wisdom (1:20–33; 8:1–36; 9:1–8), we can see that this noble woman is a human reflection of the Woman Wisdom, who represents God’s wisdom and even God himself. In essence, she embodies godly wisdom.

It is interesting to note that in many editions of the Hebrew canon, the book of Proverbs is then followed by Ruth, who is called a “woman of noble character” (Ru 3:11), and then by the Song of Songs, in which the woman plays the leading role in pursuit of the love relationship with the man.

There really is nothing quite like this poem in ancient Near Eastern literature, though there are some other more prosaic statements about the value of a good woman and advice about how to treat her. Ptahhotep urges men to love their wives and provide for them even as he counsels to keep them housebound, away from places of power. The “Instruction of Any” suggests that an efficient wife be given free rein in the home so that husband and wife can avoid strife.

31:10 worth far more than rubies. See note on 3:15.

31:16–24 The Code of Hammurapi contains several laws regulating the activities of Babylonian women who operate inns or taverns. However, this may not be construed in the same light as having the ability to buy a field or sell finely dyed and woven garments as a professional seamstress. The idealized picture in this proverb of how a woman might demonstrate wisdom in the various pursuits of life goes beyond anything that the Biblical text elsewhere suggests is open to women. Ordinarily, they did not have the legal standing to purchase land, although they certainly worked hard with their families to cultivate it and deal with its produce. The one industry mentioned in ancient Near Eastern texts that is open to female enterprise was weaving, and this may be the model for all the other activities.

31:19 distaff . . . spindle. Both of these Hebrew terms appear only here in the Bible. However, the context suggests that the translation is appropriate and that these are simply technical terms related to the task of spinning and weaving. There is a sense of intense activity performed by a determined woman willing to “roll up her sleeves” and produce large quantities of woven goods for both her family and for merchants to sell for her.

31:21 scarlet. See note on Ex 25:4. A red or purple dye would have been expensive and reserved for the wealthy.

31:22 fine linen. A sheet of fine linen would have been a valuable and desirable commodity, to be used as a bed covering or cut into smaller pieces for garments (see Jdg 14:12–13; Isa 3:23). purple. This dye, made from the glandular fluid of sea mollusks, would have been quite expensive; in this context, it is a symbol of the prosperity that the ideal wife brings to her household.

31:23 city gate. The traditional place for the city elders to gather to do business (cf. Lot in Sodom’s gate in Ge 19:1) and to hear legal arguments (Ru 4:1–4). See notes on 8:3; Job 5:4; 29:7. elders. Old Babylonian records note their legal role in judging land disputes, hearing the taking of oaths, and serving as witnesses to various transactions.