4 Profit, loss and accountability

Sample costings for publishing products and services

How to make a budget go further

Securing sponsorship, partnerships and other methods of financial support

Hanging on to a marketing budget

Marketing costs money. Even if you concentrate on online marketing (Chapter 9) or publicity and PR (Chapter 10) you will incur costs: your time; the electricity and telephone bills. The long-term cost of free material given away for review, or feature that has a production cost (even if distributed online, material needs to be prepared for dissemination), also risks removing the recipients’ need to purchase. While many of these activities will be paid for out of the general company overheads, when it comes to drawing up a budget for the active marketing of a title, a much closer line of accountability needs to be created between effort and anticipated rewards, and a firm decision must be taken on how much can be spent.

A glance at the title file of a forthcoming product should show you how many copies were expected to sell in the first year after publication, an estimation made when the title was first commissioned. The marketing budget will be designed to produce these sales and so generate enough revenue to, first, pay for the direct outlay on the title (author advance or fee, development and promotion costs and so on); second, make a contribution to company overheads; and, third, produce a profit to invest in new publishing enterprises and (if relevant) remunerate shareholders.

These three considerations will be computed together as the eventual return on investment (ROI): how much the publisher invested in the project, and how much it got back. The period over which ROI is calculated, and eventually judged, will depend on the nature of the publishing project, its long-term significance to the organisation and the specific market being targeted. For example, projects that require customers to commit into the future, especially if paid up front with a commitment to a certain period of time (e.g., subscriptions to journals or online resources), may deliver much more in longer-term customer lifetime value and hence be financially accounted over longer periods of time.

Selling through retailers rather than direct to their customers has meant that in the past publishing firms have been distanced from accurately understanding the ROI for their products. This is changing. While some online retailers do not release information on buying patterns of customers, which remains proprietary information, publishers today are actively seeking to build up communities of purchasers themselves. New methods of marketing online allow them to measure the impact of their marketing on awareness and purchasing patterns – and in the process to understand the longevity and profitability of relationships with their customers.

Finally, one can speculate on how getting free or discounted materials impacts on publishers’ attitude to price and what is value for money.

A budget is a plan of activities expressed in money terms. Successful management of a budget means delivering, at an acceptable cost, all the elements detailed in the budget. It is not just a question of keeping expenditure within the prescribed limit irrespective of how many of the planned outcomes are achieved.

The budget assigned to the marketing department of a publishing house will be just one of a whole series of payments that senior managers have to allocate. Organisational overheads have to be provided for – both those attributable to specific departments (e.g., staff and freelance hours) and those from the company as a whole (e.g., audit fees, HR department costs and IT).

The amount allocated to the marketing budget (and to other departmental budgets) is usually based on a percentage of the organisation’s (or section’s) projected turnover for that year. What you can spend is dictated by what you will be receiving.

For each forthcoming product or service, the marketing manager will estimate market size and (based on previous experience, current market activity and the value originality or newness offered by the now item being announced) the percentage likely to buy. Anticipated future income from new titles is added to other sources of revenue such as rights sales for content (both in the original and in additional formats such as online or ‘partial’ publication), reprints and investment income. Projected turnover for the year ahead, and probably for the next three- or five-year period, is planned at high-level management meetings. Expectations are subsequently monitored against actual performance, usually on a monthly and annual basis. Comparisons are then made with previous years and long-term plans updated.

The marketing budget is likely to be subsequently divided between several categories of expenditure. Four main categories exist, in decreasing order of importance:

• plans for individual titles;

• budgets for ‘smaller’ titles;

• contingency.

Core marketing costs

These are the regular marketing activities that are essential to the selling cycles of the publishing industry. These include the marketing website, the production of catalogues and new title or stock lists (increasingly available in digital format only but therefore requiring ongoing updating throughout the year rather than timed production at specific intervals) and advance notices for each title planned. The total sum required for these items is usually deducted from the marketing budget before further allocations are made. These should only be cut as a very last resort.

Plans for individual titles

Once core costs have been taken out, the money is then generally divided between a variety of different publishing projects, each one of which is in effect a separate business. The manager calculates what it will cost to reach potential buyers, aiming to reach as many as possible with the budget allocated and deciding where the available resources will have the most impact.

New titles or series, or perhaps works that are already published but need actively promoting, should have specific amounts of money allocated to their marketing. The allocation is not always made exactly in proportion to the anticipated revenue: some markets may be easier or cheaper to reach than others, and need less extensive budgets.

If it is your responsibility to draw up these preliminary allocations, consider the options for reaching the market presented elsewhere in this book, decide on which titles or series the money could most usefully be spent, then look at the actual costs. How many people does it include and how many are you able to reach already? How many times do you need to ‘touch’ the customer before they will purchase? For example, will one series of book advertisements on the subway be enough to make them buy or must this be reinforced through social media and bookshops? Publishers used to have their relationships with their customers largely mediated through specialist retailers, but they are now moving towards systems that capture customer data so that the market can be contacted directly – and a community of interest built for the future sales. Those marketing specialist information to scientific, technical and professional audiences are further ahead here; they can estimate the size of their market accurately and, based on previous experience and the size of their subscriber list, appreciate their overall penetration levels. Consider what other products and services within the organisation can be marketed symbiotically to increase the possible size of an order – through the pooling of budgets and to present the customer with the breadth of what is on offer. It can be particularly hard to estimate anticipated sales for material that is destined for a ‘general’ market (see Chapter 15).

Next comes the allocation of money to titles needing (or receiving) smaller budgets. This may mean you will only be able to promote them actively if you pool the budget with that of other titles and do a shared promotion, e.g., several titles at the same time, or appeal to the same audience through a combination of cross-selling events, writing support and related boooks. This is not necessarily an unwelcome compromise. Boosting a range of related titles together encourages an awareness of your publishing house as a particular type of organisation, and may attract both new purchasers and new authors. In the same way, most editors have a responsibility for building a particular list. Cooperative promotions back up and give authority to your main title strategies, and can provide a useful push for the backlist titles included.

Contingency

Last of all may come a contingency amount to be used at the marketing department’s discretion on any title or group of titles as good ideas come up, such as backing an author’s initiatives or attending a relevant conference. It does not always reach the final budget: during the process of reconciling how much the marketing department would like to spend with how much is available, sacrifices are looked for. The contingency budget is often a casualty.

How the four areas of budgetary division are linked

The sum of these four areas of spending is usually based on (or at least compared with) the percentage of the firm’s anticipated turnover, as discussed above. By drawing up a budget in this way the interdependence of all the titles in a list can be seen. If one title fails to achieve what it is budgeted to do, all the other titles in the list will have to work harder if the firm is to survive or profit margins are to be maintained.

Reasons for failure vary. An author may produce the manuscript late or produce a text that needs substantial and time-consuming reworking before it can be published; copyright clearance can take up to 6 months; production time may be longer than anticipated. Until a title is actually released for publication, recorded dues cannot be added to the sales figures. If this happens at a financial year end, sales will be lost from the year’s figures.

If the manuscript cannot be remedied, the sales will be lost altogether – a serious situation if money has already been spent on promotion and the author advance is difficult to recover.

If the overall marketing budget is based on a percentage of anticipated turnover (different amounts being allocated to various titles according to need and ease of reaching the market), what kind of percentages are we talking about? The question depends broadly on a judicious juggling of three considerations: the likely profit margin within the area of publishing in question; the associated development costs; the stage in the publishing lifecycle process. Finally there are a series of variable factors that influence the allocation of marketing budgets.

Considerations that arise from the likely profit margin within the area of publishing in question

There are established rough percentages spent on marketing within certain areas of publishing, and these are based largely on how the materials are sold, price levels, competitor activity and ease of reaching the market. For example:

Information resources for business and professional markets (whether online or in print) sell mainly at high prices (which reflect the costs of researching and continuously updating the content but also respond to competitor activity) direct to specialist markets, and little discount is given to the retail trade. Marketing budgets may be as high as 20 per cent of anticipated turnover, perhaps more to launch a major title in the first year after publication.

Prices within the education market servicing schools are generally low, with sales managed through educational wholesalers, and there will be less room for spending large amounts on marketing. Budgets will probably average 6–8 per cent of forecast turnover.

On academic or highly specialised reference titles, the prices may be high but the print run is very low (250–500) and so the percentage spent on marketing may be no more than 5 per cent – if that. The firm may rely on the author to implement marketing through their own networks and be effectively functioning as a packager, relying on the academic’s need to be published (or that of the funder of their research).

Considerations arising from the associated development costs

Production costs are also referred to as ‘origination’ costs. These include editorial costs, artwork, paper, etc. Reprints after a title’s initial print run has sold out can show healthier margins, once the basic origination (including editorial costs), permissions, illustrations and marketing costs have been paid for.

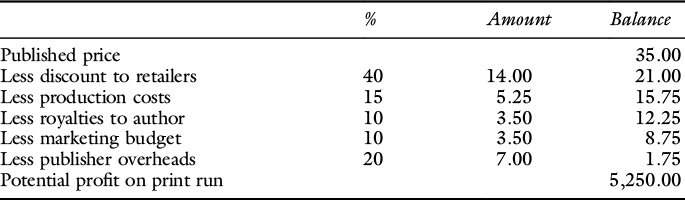

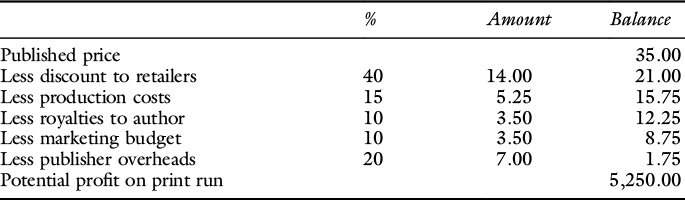

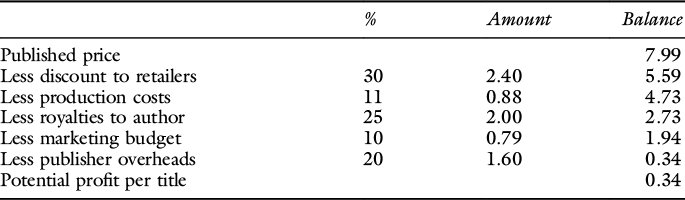

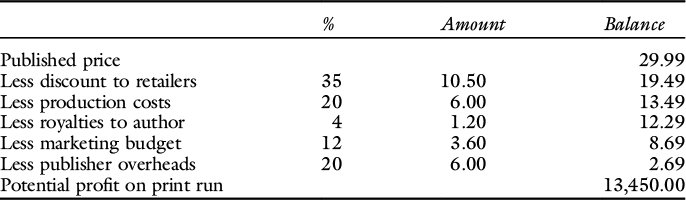

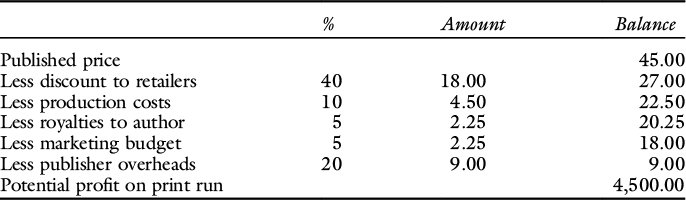

Publisher overheads generally include storage, despatch, representation and staff, as well as a contribution to general overheads, e.g., the costs of running head office. For printed titles, the amounts quoted in Table 4.1 depend on selling the entire print run. If stock is returned and has to be restocked, stored or pulped then this increases the publishers’ overheads.

Table 4.1 Sample costings for publishing products and services

New general hardback title (print run 3,000)

Subsequent mass market paperback edition of the same title (print run 30,000)

Ebook version of the same title

*Consideration of whether this is subject to VAT, and if so whether this is shouldered by publishers or retailers.

**No print run, so no limit here.

Ebook original

New academic textbook (heavily illustrated, print run 5,000, limp binding)

Academic monograph (no illustration, print run 500)

Publishing as an ebook from scratch, without a printed edition, is not (as is generally believed) necessarily vastly cheaper than producing a print title. The absence of print means that production costs are lower, sales management costs are significantly lower (with online retailers managing the selling) and the cost of physical distribution through wholesalers and bookshops is not needed. But the origination costs are very similar; many of the ‘invisible’ costs of publishing (structural and copy-editing, proofreading, creating an attractive cover and author remuneration) still need to be borne. It’s often frustrating for publishers that effective publishing is often only evident when absent; a book that is well written and beautifully designed gives no clue as to the amount of work it has taken to get it to that state of affairs.

The marketing costs of ebooks may also be increased compared to those deployed to sell their printed counterparts, as there are some new ones to factor into the traditional mix, e.g., website management for author and publisher, managing social media, reformatting for different ebook readers.

Reformatting a product can further extend its reach within a niche market before it is made available in a mass market edition, or to meet the needs of a different mass market. For example, producing an ebook first, to test demand, and then producing a hardback and paperback; or producing a hardback and an ebook at the same time. Similarly sometimes a ‘C format paperback’ version (hardback edition size and type of paper, limp binding) will be produced in between the hardback and a mass market edition, in order to extend sales at a higher price.

But reformatting a print title as an ebook will always incur additional costs (it’s not as simple – as is often assumed – as ‘pressing a few buttons’) and how much can be spent on marketing will depend on whether the fixed costs of origination are set against the print book or the ebook. In the UK, the Society of Authors calls for higher author royalties on unenhanced ebooks (versions of the existing print edition with no additional editorial changes) and this too impacts on the amount that can be spent on marketing.

The ‘bundling’ of formats may add incremental sales without necessarily damaging those within each category. For example, bundling a hardback with an ebook might make a very attractive proposition to a reader (one to display at home, one to have when on the move) and extend the income received, without necessarily diminishing the sales in either format (very few customers currently buy both).

Considerations arising from the relevant stage in the publishing lifecycle process

There may be a requirement to spend heavily on marketing at the time of publication in order to achieve an acceptable return on investment (ROI), because if sales do not take off well, the titles will flop in the long term, even if you subsequently alocate more budget. For example:

Information resources for business and professional markets (whether online, print or both) need large initial promotion budgets, perhaps for two or three years, until the sales strategy can become chiefly one of encouraging subscription renewals.

Within educational publishing, a major new series aimed at securing large-scale adoptions will need strong initial marketing momentum. Once the adoptions have been made and the scheme is being used in schools, less intensive selling will be needed.

When promoting a new journal it may be cost-effective to spend the whole of the first one or two years’ individual subscription revenue on acquiring a subscriber. Once the subscription is recorded the subscriber should stay for a number of years and hence their lifetime value (generally computed to be around 7 years) will enable the venture to become profitable.

Launching a new author in a competitive market will require significant marketing investment. Some publishing houses spend early, to get a momentum going and build on this in future; others rely on the efforts of their authors in approaching the market and allow market forces to direct where to allocate future spending.

In general, the more the publishers have paid to acquire an author, the more they are likely to spend on marketing. In instances where it has been expensive to secure an author, and who need high-profile marketing campaigns to launch their transfer, it may only be after a second title that a publisher makes a profit, hence the popularity of two- or three-book deals.

Variable factors that influence the allocation of marketing budgets

Factors that can influence the economics of individual publishing projects, the amounts paid to authors and the financial health of the organisation as a whole – and hence impact on the size of associated marketing budgets – include:

The gap between commissioning of the work and delivery. The publisher is generally paying a variety of costs long before they have anything available to sell. Thus, in general, the quicker the publisher is able to move towards remuneration through sales, the better. Arrangements that involve paying commission on sales that are achieved (rather than anticipated) may enable greater risk-taking and a higher marketing spend.1

The terms on which titles are taken by retailers. The levels of discount given to different accounts will depend on various factors including the quantity taken, the terms on which the stock is provided (firm sale or sale and return) and the overall level of business between the two parties. Agreements that lock the two sides together (e.g., buying on firm sale, guaranteed featuring in marketing materials put out by the retailer) may result in a higher marketing spend.

Supermarkets get much bigger discounts in return for firm sale and high quantities, and often use the stock as ‘loss leaders’ to draw customers into their stores. This is generally paid for by increasing publisher marketing spend and reducing author royalties.2

Online retailers similarly get very high levels of discount. There is, however, ongoing concern about the accounting procedures of some and, in particular, arrangements for paying organisational taxation – and whether these are fair to the businesses they compete with.

The prices at which retailers sell the stock. In markets where there is no retail price maintenance (i.e., the price suggested by the publisher may be discounted by the retailer) the sums received may be much less than their official value. If the publisher has agreed to an additional discount on launch, in order to support initial marketing momentum, then increased sales may result. If, however, this does not result in significantly increased sales, the profits per title sold will be further reduced. The sums received by the author are generally based on receipts not the official value of stock.

Along similar lines, if the selling price cannot be guaranteed, marketing initiatives based on titles that will sell at full recommended retail price are particularly useful. For example, authors heading events and signing at literary festivals can add value to a product – and hence stock is usually sold for its full recommended retail price. Such opportunities may be worth backing with an additional marketing spend (or increased retail discount).

The level at which product prices are set. It’s important to note that prices can be arrived at on the basis of market expectations as well as actual costs. For example, the higher cost of a hardback reflects aspects of production such as lower print runs and hence higher unit costs for each title printed, and a higher royalty rate, but also market perceptions of cost and expectations that a hardback title will be more expensive. Similarly, there may be a decision to ‘skim’ the market to fulfil all the demand for a high price before penetrating the market more deeply with a mass market version.

The availability of market research may also tempt publishers to spend more. Estimating the demand for new authors is always difficult. It follows that those who have demonstrated demand by self-publishing may be an attractive investment, particularly if in the process a new area of consumption has been identified and can be further developed in future with new material for the same audience.

Similarly, digital marketing and dissemination permit experimentation (and are often used to test or prove a market for which a subsequent print version could be considered). Digital marketing permits rapid experimentation with offers and free samples to build a market or establish a profile – or implement what has been observed. Often these ‘loss leaders’ do not generate a great deal of income for publisher or author but can be useful in building profile and readership, and their implementation through digital media means they can be established and taken down very quickly, to build on what is learned in the process (e.g., free for just 24 hours).

In some markets sales or value added tax is added to the merchandise being sold; sometimes there is VAT and sales tax on all products (perhaps at a different rate from the standard), in others just on ebooks and CDs. How this is managed is a further complication. Is it visible to the consumer (i.e., itemised on the receipt or invoice they pay)? Alternatively, is it absorbed within the margin of the publisher or the retailer – and if so, which? How tax is managed will impact on consumer perceptions of the value they receive and their tendency to purchase.

Sample costings for publishing products and services

Given all the specific circumstances and conditions listed above, there has been much discussion over whether the following figures should appear in this book at all. We eventually decided that they did have a role in helping to explain the broad structure of financing publishing. They are not designed to show that any one format or genre of publishing is intrinsically more profitable than any other, rather to isolate the variables that need to be taken into consideration when planning a marketing budget.

To summarise, publishing has a very complicated financial structure. Each title is in effect a separate business for which costs must be calculated and the marketing allowance is just one part of that equation – and cannot be seen in isolation. Jo McCrum, assistant chief executive of the Society of Authors comments:

Bear in mind too that the retailer discounts can vary and be much higher than these examples. UK Amazon, book club and supermarket discounts are around 70 per cent on most trade titles. The 70 per cent Amazon takes from publishers’ ebooks/books leaves 30 per cent to be split between publisher and author on a high-discount royalty basis. Sometimes special offers can apply on ebooks where the discounts can go towards 95 per cent. Wholesalers take 60 per cent of the cover price, so an authors’ royalty at that point falls to a receipts basis and the share is therefore much smaller. Independent bookshops get the smallest discounts (35–40 per cent) but this means that author royalties received are calculated on the cover price, and hence more is received.

Publishers will say that the level of discounts they have established with suppliers is confidential commercial information, so we cannot say with certainty what has been arranged. But from evaluating the number of copies sold (via royalty statements) and the monies actually coming in, it’s not hard to work out that publishers are now forced to pay very high levels of commission on some titles, and authors – the original creators of what is being sold – are not getting a share that is either proportionate to their investment in the project or fair.

On titles that are self-published, Amazon takes a 30 per cent distributor’s share and sends the remaining 70 per cent to the self-publishing author. It’s ironic that authors who are self-republishing their out-of-print backlist titles are often getting better returns than they are on their front list titles from their publishers.

In the UK, losing the Net Book Agreement can now be seen as a disaster for the publishing industry, and a precursor of the ferocious discounting that is threatening to destroy it.

If it is thought essential to award a larger than average marketing budget, or indeed to assign more money to any of the routine costs of publishing (e.g., to pay the author a higher advance, give more discount to the book trade, or spend more on production) then either the unit sales must be greater to justify the increase or another variable must be altered. Options here include:

• selling the content in another way (e.g., in digital form);

• increasing the unit price (perhaps by producing a smaller number and building in exclusivity by numbering the print run or bundling the product with other items to make an augmented offer to the consumer for which more can be charged);

• lowering the quality of materials and hence the production costs;

• paying reduced royalties;

• looking for a co-publishing deal that makes production costs more favourable and eases cash flow.

But this needs to be managed against delivering the right message to the market. Spending too much might be counterproductive. For example, consider the fundraising mailshots sent out by charities: they are usually printed on recycled paper, stressing an urgency and need that would be entirely defeated were full-colour brochures enclosed. But when it comes to their gift catalogues, they print in full colour to show the merchandise in its most advantageous light.

Some companies have tried to improve sales by substantially increasing their level of promotional expenditure, but if it costs proportionally more to achieve the resulting extra sales then the outcome can be financial ruin. Decisions to overspend on marketing may still be made, and sometimes the risks pay off, but it should not be forgotten that monitoring a budget is an essential part of drawing one up, and people can lose their jobs or firms go out of business for failing to implement what they have agreed.

Finally, it’s worth noting too that even if you award identical marketing budgets to all your titles, some will always outperform the others – what Cory Doctorow has dubbed ‘scratchcard publishing’.3 If sales for one title disappoint and you have extra resources to spend, it is usually better to allocate the additional funds to titles that are doing well than try to recover the position of the poorer sellers: it’s better to back the winners.

Once a basic marketing sum has been allocated, the next step is to budget for when it should be spent during the year. There are external constraints on you.

When the market wants to be told about new material

Promotion is usually a seasonal business; timings will vary according to the type of book being promoted and the market being approached. In markets where Christmas is a major holiday, roughly 40 per cent of the year’s general sales in bookshops take place between the middle of October and 24 December. Most publishers for this market therefore time their main selling season so that the books are on the stockists’ shelves ready to meet this bonanza. In the same way, educational publishers promote titles to the schools market at the times when teachers are considering how to spend their budgets, and academic publishers aim to reach their market when reading lists for students are being compiled.

When the titles themselves are scheduled

The production department will produce a list giving scheduled release (when stock goes out from the warehouse to the trade) and publication dates (when retailers can start selling). Promotion schedules should be planned around these dates; with some types of product, timing is particularly important. Printed yearbooks and directories must be promoted early because they age and get harder to sell as the new edition approaches. Books with seasonal covers (e.g., related to Christmas or summer weddings) need to be pitched early. Academic monographs too must be promoted ahead of publication: as much as 60 per cent of first-year sales can occur in the month of publication. If promotion plans have not been carried out and the dues recorded by the time of release, sales may never recover.

The need to promote early should be balanced against the risk of peaking too far ahead of publication date, with the danger that the effects will be lost. The fault may not be yours: the author may deliver the manuscript late; production can take longer than anticipated. And timings may need to be adjusted forwards too. Authors may share information on their forthcoming titles via social media before you anticipated this would happen, and you may find yourself facing sudden unexpected demand, long before scheduled publication; difficult if you have arranged production in a distant (but cost-effective) location and the costs of bringing the material back by air are extremely expensive.

Online sites offer the opportunity for customers to place pre-orders and this is a very useful way of generating initial momentum (guage how far in advance of publication to make them available, look at the terms and conditions and then consider prevailing market factors – too early an announcement may encourage competitor activity). All the pre-orders received are released on publication day, and thus the title’s augmented first-day sales may be enough to raise it into the category of bestseller, with the accompanying attention.

Selling online also means that the variables of the marketing offer (price, costs for postage and packing, discounting) can be changed to fit in with marketing strategies. This permits the making of temporary offers, specific promotions to particular groups (e.g., offering the market a code that, when entered on a website, reveals the special price offered), and what is learned in the process can be fed into future campaigns.

When you have time to market them

Promotions that are not related to publication dates (for example relaunching old series or organising a thematic push for the backlist) can be scheduled for less busy periods in the calendar, but again market acceptability must be considered. Publishing is most often a seasonal business, and you cannot really avoid this. You must just accept that you will be busier at certain times of the year.

Once the budget is established, stick to it – or only depart from it in a conscious fashion, with permission. In most houses once invoices have been passed by the person who commissioned the work (and it is generally that person who checks them against the quote), they are sent to the individual in the accounts department who deals with marketing expenditure (or in large organisations, a specific list/area of activity). A finance manager comments:

In return, monthly reports are generally provided on spending levels, although reports can also be provided weekly, quarterly or annually, depending on the level of activity and the need. Generally speaking, we can produce reports the day after expenditure has been committed or spent on the finance system so, if we entered an invoice today, we could produce an up-to-date report tomorrow. It may be worth noting that we also report on variances against budget, so if one month your budget is £10,000 on staffing and resources and you only spend or commit £5,000 we would report a £5,000 variance which would then require an explanation such as timing or allocating of the budget to an alternative category.

How much financial reporting is provided directly to you will depend on your position within the organisation (whether or not you are a budget holder) and the scale of the funds for which you are responsible. Although more financial reporting may be available to you than you initially realise, it may still be worth keeping a running balance of how much you have spent (or committed but not yet billed) and what still remains from the title’s budget.

It may be helpful to decide at the beginning of the year the percentages of the individual title budgets to be spent on online marketing, online support, print, design, copy, despatch and other key elements. That does not mean the proportions cannot be changed if specific scenarios occur. A marketing manager once spent a project’s entire budget on a delegate place at a relevant conference because this brought with it a copy of the delegate list. She did not even attend.

When considering printed marketing materials, it’s helpful to look at costs per thousand for leaflet production lists and mailing charges. Unit prices for print reduce as numbers increase, mailing lists and despatch charges in general do not (or not by very much). Harness your promotion expenditure to your marketing responses and you start to get very sophisticated market information. If you compare the costs of producing a catalogue (on- or offline) with the orders received directly from it (or perhaps received during the period over which it was being actively used for ordering) then you can compile a figure for orders per page and an accurate indication of how profitable your endeavours have been. This is easier for publishers promoting to markets that have limited purchasing options and hence where the results of their efforts can be isolated (e.g., professional publishing or STM), but accountability is a culture to be developed in any sector and is the way the rest of the retail trade is run (the key ratio is floor/promotional space to revenue).

How to make a budget go further

Affording effective marketing in publishing is tricky: the purchase prices in general are low, as are often the quantities in which books sell (15,000 units for a new paperback novel will generally afford it bestseller status). It follows that being awarded enough marketing budget to enable each title to reach its full potential is not always possible. At the same time, however, take comfort from the fact that there are more opportunities for the free coverage of books and their authors than any other product or service (see Chapter 10 on PR and free marketing). Try the following money-saving techniques:

Take personal responsibility for your budget

Take personal responsibility for your budget and you are more likely to be efficient in its use. So start by observing your own buying habits: what are the trigger points that make you part with your own money; how much information do you need to make a buying decision and what are the aspects of an organisation that make you comfortable/uncomfortable about buying from them?

Build a culture of accountability. Circulate the results from online campaigns; analyse the progress of each promotion; record sales figures before and after marketing efforts; make recommendations on how they could have been improved/why they were so good. There is often a reluctance within the industry to recording why marketing did or did not work – even if you decide not to share what you observe, keep a record for your own future instruction.

Watch what your competitors are doing, both publishing and non-publishing. Keeping a close eye on the publishing industry can be difficult, but one effective way of managing this is to give each member of staff in the marketing department a competitor to ‘adopt’. They then become responsible for watching out for the competitor’s marketing and plans. Pool the information at a meeting and you can have a very helpful overall survey of your market.

Learn from other industries by developing a general interest in advertising and marketing and not just confining your study of marketing materials to the messages put out by other publishers. Above all, be interested in your products and who buys them – and try to observe this in action.

Get your timing right

This is crucial, as was noted above. Timely handling of the standard in-house procedures for book promotion is particularly important. Ensure the title is listed on the website and in catalogues for the season in which it is due to be published. Be sure that the advance notice is ready to appear at the right time, containing up to date information.

Explore online marketing (see Chapter 9)

Although the same care must be taken in the preparation of information, the costs of informing a market online are much less than through sending out printed marketing materials. Ensure you have an effective website and crucially that you update it regularly to give those returning to it something new to look at – offer competitions, reduced price incentives for limited periods, free samples. Ensure this is linked to mechanisms for effective delivery, via a third party if you cannot arrange it yourself.

Benefit from viral marketing

Feed information on your titles to all possible carriers, association websites, those producing relevant newsletters and those active within enthuser-groups which might regard the information as useful to members or followers they attract.

If you find a specific community that is particularly interested, encourage them to be ambassadors for your project: to ‘wear your books as a form of self-expression’4 and communicate their enthusiasm through social media. Making sample material available to them free so they can run a competition or offer it as prizes may get them talking about it. Get them to endorse it for you and they may do even more. This is a particularly useful tactic for independent publishers, when you can build on a passion that unites you with the wider community who share your enthusiasm.

Spot mutually useful synergies

There may be mailings (online and print) going out that you could join if you asked; secondary markets may exist and prove highly profitable if you think of targeting them. Think laterally. Why not send all schools a catalogue request form in case they are interested in other areas for which you publish? There are certain well-known combinations of interest and profession (many academics seem to like opera, and lots of politicians seem to be interested in bird-watching); if you have products on your list likely to appeal, try them out.

Get better value for money for your spend on print

If you decide you do need a printed leaflet, don’t spend too much on production. Instead of sophisticated design, concentrate your attention on effective copy and buying reasons that speak directly to the market (see Chapter 14). Remember that overcomplicated design can get in the way of effective communication.

Run-on costs (see Glossary) for leaflets are often very good value for money compared with the overall set-up costs for a job. Consider increasing the print run and then trying to circulate what you produce as widely as possible: through loose inserts in relevant journals; circulation at specialist meetings; insertion in delegates’ bags at conferences; distribution to the author for their personal use and so on. If you are sending printed information to standard outlets (e.g., bookstores and libraries), use shared mailings rather than bearing all the despatch costs yourself. In surveys, most libraries, academics and schools say they don’t care whether promotional material reaches them on its own or in company; it is the content that counts.

If commercial opportunities do not exist, then consider forming partnerships with non-competing firms to share costs (assuming the mailing list can be used in this way). Can you take exhibition space in partnership too? These methods may attract slightly lower levels of response than individual mailings, but the cost of sales will also be substantially reduced. You will be able to reach more people for less money.

If you prepare a central stock list or standard order form, run on extra copies and use in mailings, include in parcels or send to exhibitions. If you use a new book supplement in your catalogue (perhaps inserted in the centrefold) can this too be reprinted for use in mailings? If your catalogue is designed as a series of double-page spreads, could these be turned into leaflets later on? With this in mind, if you are working in more than one colour, ensure that anything you may want to delete later on (such as page numbers) appears in black only, which is the cheapest plate to change. Can full-colour material be reprinted for a second mailing in two colours rather than four?

Sometimes you may not need formal marketing materials at all. A sales letter with a coupon for return along the bottom can be a very efficient way of soliciting orders. (The opposite generally does not apply, by the way: brochures almost always need a letter to go with them.) Update your information not by reprinting but rather sending out accompanying photocopied pages of reviews or features that have appeared.

Use your authors

Author proactivity is often a highly effective route to the market and today author commitment to involvement in publicity is generally included in the contract (see Chapter 11 on working with authors). Have an early meeting with the authors of forthcoming books and discuss how you can work together to promote interest and sales.

Use free publicity to the maximum possible extent

The pursuit of free publicity should not replace your standard promotional tools; rather, it should back them up. But don’t end up paying for advertising space if the magazine would have printed a feature with a little persuasion. Many magazines are willing to make ‘reader offers’ – an editorial mention in return for free copies to give out (because it helps them cement the loyalty of their readership). Nor should you offer to pay for a loose insert if your author is on the editorial board and could have arranged for it to be circulated for nothing.

To make maximum use of free publicity you need to exploit the link between what you are promoting and why people should be interested, and the background of the author may be more significant than their new title. Try to find media that serve the needs of specialist markets that are not routinely used by other publishers, and non-book outlets in retail, which can help your materials stand out. For example, find out about author’s hobbies and interests and you may find a new avenue for promotion emerges, one where there is much less competition. Is your author interested in model railways or caravanning? Both have extensive associated publications with high circulations.

Negotiate as a matter of course

The publishing industry spends little on space advertising – it’s one of the reasons why the survival of the book review pages is consistently threatened as they bring little revenue into media organisations. It follows that there is a general understanding that publishers are not cash-rich organisations and this can be used to your advantage. There is a standard publisher’s discount of 10 per cent for booking advertising space. Sometimes more can be squeezed if you have not advertised with them before (a ‘trial advertisement’), or the rate the medium quotes is too expensive for your budget. If you have the time, use it – the advertising sales representative will probably come back to you with a reduced price. Particularly good deals can be obtained just before a magazine goes to print – once it has gone to the printers the space has no value at all. If you go for a series of adverts you should get an additional discount, and likewise if you book a year’s requirements in one go.

Do you have someone in the department who has previously worked in advertising sales? If so, ask them to handle negotiations for you, and you will almost certainly reduce your anticipated costs further still. Consider going on a negotiating skills course.

One final tip on dealing with discounted offers: decide where you want to advertise and then negotiate on price. If you allow yourself to get used to responding to the special offers available from magazines that you are less than committed to appearing in (i.e., they were not on your original media plan), your marketing becomes much less targeted and you run the risk of seriously overspending. Remember that space costs are only one part of the total outlay. Continually saying ‘no’ can be an exercise to find out just how much can be negotiated off the list price.

Effective management of cash flow is crucial to a business; an organisation may in theory have made many ‘sales’ but in practice received little remuneration. If a keen eye is not kept on the return of actual cash, the future of the organisation is threatened.

One way of reducing costs is to devolve distribution to a supplier. Distribution is labour-intensive and demands precision (customers want the materials they ordered, quickly and in perfect condition). Devolving it to a wholesaler or online retailer who can supply low-value small orders, leaving you to concentrate on creating product and associated demand, can be a cost-effective response leading to regular return of income.

The setting of terms (e.g., payment periods, the arrangements under which stock may be returned) with retailers is of crucial importance. Published products may be sent to trade outlets on a variety of different terms, some more beneficial to the publisher than others. Encouraging the trade to ‘buy firm’ rather than on ‘sale or return’ prevents unexpected returns that reduce sales and the overall profitability of particular titles.

If you are going to accept direct orders from individual customers, and benefit from the associated understanding of your market, provide every opportunity for those ordering to buy direct and pay early, and in the most cost-efficient way for you. Some credit cards charge a higher percentage of the sales invoice than others. To encourage them to buy direct you can try to promote the value of loyalty to something they believe in, reassuring them with a cast-iron guarantee of satisfaction or their money back. For example:

We are an independent publishing house and would appreciate the chance to fulfil your order directly. Apart from ensuring that the book gets to you more quickly, this offers us an important benefit – the chance to make a sale – and hence to carry on producing the kind of titles we know you value.

Institutions such as schools, colleges and libraries will need an invoice to pay against, but can they be encouraged to pay sooner rather than later? State your credit terms on the website and again on the associated order form. For serial publications, directories and journals, offer customers the chance to complete a standing order. In return, offer to hold the price for a second year or perhaps give a discount.

The wording on company order forms does not have to be regarded as unchangeable (although you will need support and sign-off from colleagues if you intend to alter existing practices). Try to gain access to the metrics of any online ordering offered by your organisation and in particular the point at which non-completers gave up. Seemingly trivial amendments to the process could have a significant impact on completion rates. Is there anything in your auto-completion system that could mean a confirming email is picked up by a spam filter and hence not easily received by your customers? Study ordering mechanisms received as a consumer, and appropriate the best ideas. Experiment with different formats and styles, all with the intention of making yours as user-friendly and easy to understand as possible. Pay attention to the particular mechanisms that your market values – the chance to send a personal message with an item being sent to a third party; gift wrapping; gift receipts which do not reveal how much was spent – all of which can make the relationship with customers stronger.

Apply for all the free help you can get

Can your authors arrange for you to attend relevant meetings, run book exhibitions and make special offers to the membership? Does your firm belong to any professional associations from whose collected wisdom you can benefit? Find out about the special interest publishing groups that are part of your professional organisation, and get copies of the reports they publish; when you are more experienced it may be worth trying to attend or get yourself on to an associated committee. Read the professional press that your market reads (and the general press that covers it), and look out for helpful articles that improve your understanding of your customers. You will almost certainly spot useful quotes about market needs and key market issues that can be used in your promotional materials and perhaps spot marketing and promotion opportunities too.

Bulk sales

Are there any specific interest groups that offer the possibility for ‘special sales’: learned and professional societies and associations that may promote to their members? Deals you offer may enable them to represent themselves to their members as proactive and present better value to their membership for example, by securing relevant products or services at a discount.

Securing sponsorship, partnerships and other methods of financial support

Others may be willing to support your product development and marketing plans, given sufficient overlap between your respective aims. From experience, it’s important to research their organisational objectives and meet them to establish their priorities and ethos. You may find that you offer a means of accessing or delivering a target group that they lacked the resources to achieve independently, or they find your mission aligns with their own whether from a business or altruistic point of view – either way, they may be amenable to making a financial contribution or supporting you in kind. For a successful relationship, the following guidelines may help:

• Try to establish relationships with personnel at a variety of levels within the organisation you are working with; then, should one employee leave, you are not then starting all over again.

• Keep track of their official information, which will have been the product of long discussion, to ensure a match between your respective aims and outcomes. As with job applications, pay attention to the verbs they use and reflect them back.

• Your partner organisation may prefer the funding of a specific process or outcome, which they can both isolate and identify with, to a general contribution to overheads.

• Pay timely attention to the various mechanisms your partner organisation needs you to deliver – a short contribution for their regular published reports will almost certainly be required.

• Keep in touch at regular intervals: newsletters, phone calls, meetings in person.

• Acknowledge their involvement willingly and generously, and not just when you know they are present.

Other business models for funding

There are other new funding initiatives emerging to pay for publishing projects, several of which have been shown to work in other areas of industry such as the music business. For example, crowd-sourcing has been experimented with as a means of securing funding, offering enthusiasts the opportunity to invest in the publication of material they support – although ironically this looks back to subscription models of publishing used in the nineteenth century.

Other organisations are exploring how they can benefit from marketing mechanisms that are already established within particular groups. Using the old direct marketing principle that those who are happy to buy direct make better prospects than those who are professionally or temperamentally interested in the subject matter of your publishing, it may be more effective to pursue markets that enjoy online shopping, and look to sell them publishing products that you develop for them, than to build lists of book-buyers. For example, those loyal to particular clothing, food or home-ware catalogues might see books as a related brand extension, in the same way that they view bed linen, home-cured hams and gardening supplies. Associated marketing might be able to piggy-back on existing promotional plans, with the significant added advantage of being the only publishing material promoted – rather than in the context of a bookshop where there is so much choice. Potential partners may exist within the book market already for firms with a strong brand identity or particularly effective marketing mechanisms. For example, literary societies that publish special editions for their membership could provide an excellent basis on which to build the wider marketing of content. Similarly, investing in self-publishing companies could provide new revenue streams as well as the option of first access to titles and authors that demonstrate success.

One model publishers might be able to develop without an acquisition is freemium, the concept of providing some content for nothing while charging for other features. After all, with customers increasingly expecting free content, publishers need to create ways of still making a profit while giving content away. Major projects such as Pottermore and a ‘Spotify for books’5 might make freemium seem complicated and expensive to operate. Despite this, a simple successful model is already being used in China. Websites allow authors to upload stories that can be read for free; once a work is read a number of times, the writer is labelled a ‘VIP’ and the site starts charging for their content. Payments are kept small so, as the UK lacks China’s gigantic domestic market, British publishers would arguably either need to charge more or ensure any site could sell internationally.

Service provision between publishers is another growth area. While publishers have long distributed books on each other’s behalf, the complexities of digital are providing further opportunities to sell services to smaller firms, with the likes of Faber Factory offering ebook distribution, marketing and account management. As Mike Shatzkin has explained, smaller publishers are incentivised to outsource ‘parity functions’, essential business functions that fail to differentiate the company from rivals.6

Hanging on to a marketing budget

Finally, although the marketing budget is just one of many financial responsibilities of the company, when times are difficult its reduction is often an easy way to reduce expenditure. How can you resist this tendency?

The best plan is to combat difficulties with information, so you know why titles are selling badly, and are making changes to market them more efficiently. Compare annual sales patterns year-on-year. Are any market changes responsible for the differences you see? If you are promoting through a number of key associates, did any perform particularly badly? By contacting new organisations you may be able to remedy the situation (although if you have had to market twice over to achieve your basic orders, the gross margin will still be reduced). Talk to the reps and customer services. Are products being returned because they do not meet the expectations of those to whom they were marketed? Is the offer unconvincing? Online sales patterns can tell you a great deal; the effect of changing variables (e.g., the price, the offer or the extensiveness of the guarantee) can be monitored very closely. Experiment with one variable at a time, so you can isolate the results.

If cuts are the only option, the key skill is knowing which elements to axe while doing the least possible damage to sales. Understanding the reasons that particular promotions have either failed or succeeded will help you decide what to avoid in future, and how to plan better for next year. The very last elements you should cut are the regular tools of the trade: the website, online catalogues and advance information sheets on which so much of the publishing sales cycle depends.

Case study

Crimson Cats:7How a small-scale endeavour, with a distinctive identity but low cost-base, can be both a highly effective and also personally satisfying commercial operation

Michael Bartlett was a BBC radio drama producer who commissioned and produced the afternoon plays on Radio 4 in the early 1980s. He was also a professional writer himself but while he was in control of commissioning other writers he did not feel it would be right to offer his work to the BBC. He enjoyed the editorial role very much but knew that rising higher in the BBC would mean taking on an administrative rather than a practical role, and this he did not want to do.

He left the BBC in 1988 in order to help a colleague set up a new commercial radio station in Guildford, with the agreed long-term aim of him then producing speech programmes for the channel. But once the station was established they found that achieving commercial funding for the kind of programmes he wanted to create was never going to be likely. He moved on, setting up a production company producing audio training materials for industry, first on cassette and later on CD. This initially proved lucrative, but when training materials began moving from hard copy on to the internet he found the motivation to produce yet another series on how to manage meetings or negotiate effectively increasingly hard to find.

He and his wife Dee Palmer (also a radio producer) decided to build on the skills they had in pursuit of something they both enjoyed doing. In 2005 they established an audiobook publishing company – Crimson Cats.

They avoided large set-up costs by using their existing expertise (spotting material likely to appeal; editing and developing scripts; recording and producing). They built on the recording equipment they already owned and establishing premises in a room they could soundproof in their new home in Norfolk. They used material that was either out of copyright, so close to being out of copyright or so long out of print that its publishers, often surprised to be approached, were willing to release rights in return for a share of the profits rather than requiring money up front.

The one ingredient they did not have at their disposal was the voices – professional actors whom they considered essential for a quality product. They got around this difficulty by coming up with a creative solution to paying them. Rather than paying agreed fees up front, they asked the actors to record without an initial payment in return for an enhanced royalty (15–20 per cent of the profit on sales, depending on the nature of the project and the size of the actor’s involvement). To establish the total on which the percentages were worked out, only the direct costs of production (CD production, cases and the associated printing of jacket material) were counted before the artist’s deduction was made. Michael commented:

It’s possible for any business to rack up all its overheads and so not have a profit to share with collaborators. We did not want to operate like this. All the actors we used had made a commitment to us, and having trusted us it was important that we delivered a fair return to them. Once we have paid for the CD duplication and printing and any specific copyright associated with that title (music for example), then the rest is the profit on which we calculate the royalty. We pay all other costs of producing the recordings (website management, marketing, accountancy costs, etc.) ourselves. All our actors seem happy with the arrangement and have stayed with us.

After years in the broadcasting and audio production world they had many contacts, and judicious use of these enabled them to keep their costs low. Michael comments:

We used all our broadcasting contacts to find a cost effective CD duplicator and printer (we use a company in Hull). We needed a graphic designer and that was someone (in Leeds) who we had worked with on commercial training projects for many years and had become friends, so he cut us a deal.

Naming a new business is always a challenge and here again we used our network. We were looking for something a little offbeat and hence memorable and we came up with the idea of ‘Sleepy Cats Audio Books’. We envisaged a logo of a sleeping cat – the epitome of relaxation. Then a friend pointed out that such a name would be a gift to hostile reviewers: ‘Their audio books send you to sleep.’ So we came away from that. We mentioned it to our designer and two days later the logo of the cat’s silhouette arrived with the suggestion ‘Crimson Cats’. It’s not a name people forget easily which is a big advantage for a small company.

What to charge for the audiobooks was the subject of long discussions and research into other bestselling audiobook publishers. They eventually set their prices in line with the slightly smaller ones; organisations such as HarperCollins, Random Century and the BBC obviously have the benefit of scale. They had to consider the level of discount they could afford if they sold through bookshops. This is a tiny part of their sales but following reviews in the national press (which they have had for almost all titles) there was usually a small spate of bookshop enquiries. The bookshops have to make a profit too so there needed to be a discount for them. Sadly there are only two broadsheets left that publish audiobook reviews – the Times and the Telegraph. Sue Arnold of the Guardian was a great fan:

For a tiny publishing outfit, two adults and a cat with a DIY recording studio in the basement of their Norfolk cottage, Crimson Cats produces some of the most sophisticated, original and genuinely interesting audios around.8

Postage and packing is paid by the customers so does not affect the unit price. Managing the process through their local post office has played a significant role in the local economy, as does the freelance help they employ when they are especially busy. They do a particularly healthy local trade in CDs for presents in the run-up to Christmas.

From the start they have specialised in unusual material: quirky taste and in particular material that cannot be sourced elsewhere; this is the only way they can gain an ‘edge’ over larger international publishers. Thus, while there are many recordings of Three Men in a Boat, Crimson Cats recorded Jerome K. Jerome’s autobiography (My Life and Times). A recording of the death of Nelson, a reading of the graphic, eye-witness account of the surgeon on board the Victory similarly sold well (Authentic Narrative of the Death of Lord Nelson). And recordings of the early stories of Jane Austen (The Beautifull Cassandra9) and the letters, journals and stories of Katherine Mansfield (Finding Katherine Mansfield) have become strong sellers, mainly by making links with relevant societies – the Katherine Mansfield Society in Australia proved particularly good customers. If Michael and Dee are approached by writers with material they feel strongly about, and in the process spot something they think would appeal to a wide market, they use their editing skills to publish from scratch. This has led to success with one family’s history of service in Afghanistan in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which resonates with involvement today (My Grandads and Afghanistan) and a collection of poetry and prose by women written during the First World War (War Girls).

Print on demand means they need to print only as much marketing and packaging material as they need – rather than seeking to anticipate (and store) their future requirements. Digital marketing enables them to keep in touch with their customers and let them know when a new release is out, and the internet allows worldwide sales, especially, but not exclusively, by MP3 downloads. And while the markets for some titles are highly specific, there is significant evidence that their customers enjoy browsing and buying across their whole list.

The business is now an established entity. They produce one or two new titles a year and servicing these and the existing back catalogue requires about two days a week of their time, an ongoing support for their wider lifestyle. They enjoy the process, find their customers relate to a small business whose taste and values they appreciate and that, by sticking to their instincts and spotting material that is new to the market, they have found a niche that is profitable. In short, they provide a perfect example of the business principles outlined in Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail (Anderson 2009).

Case study

Selling apps: An interview with Tom Williams, marketing producer at Touch Press

Tom Williams took both an undergraduate degree in English and then a Master’s in Modern Culture at UCL in London, researched and wrote a biography of Raymond Chandler,10 moved into media journalism and then spent 5 years as a literary agent with PFD (Peters, Fraser and Dunlop a UK literary agency). He was always interested in the digital potential for content and was the first agent to sell an app on behalf of an author. He joined Touch Press in 2013 and is their marketing producer, working with a team of four others.

Touch Press produce apps for the Apple iPad. Launched at the same time as the tablet, their business model is thus only 4 years old. But the original team behind Touch Press were quick to spot the possibilities for content development through a new format, and when sample iPads were first made available to journalists, one of the pre-loaded sample apps was their The Elements.

The organisation produces apps in several broad fields of interest: science and technology (e.g., The Elements, Journeys of Invention, Solar System, Incredible Numbers), music (e.g., Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, known within the organisation as B9, The Liszt Sonata and the forthcoming Vivaldi’s Four Seasons) and literature (e.g., Shakespeare’s Sonnets and a forthcoming app featuring Seamus Heaney’s translations of Aesop’s Fables).

Whereas early apps tended to be in effect interactive ebooks, textual content enriched with additional website links, today the app has shown its capacity to evolve into an experience that is both more complete and discrete, characteristically combining a central theme with additional material which intellectually engages the user in both its re-experience and re-evaluation. So the B9 app allows the user to compare various recordings of the same work, to hear experts comment on stylistic and presentational differences and share their understanding of its history; an engrossing experience that enhances the user’s understanding of the main content. So far apps for the adult market have tended to be in areas of non-fiction, although apps featuring children’s stories have been developed with particular success by Nosy Crow.11

Within traditional publishing, marketing often comes late in the process, applied to a finished product to aid its wider dissemination rather than having been an integral part of its development from the outset. Tom’s role at Touch Press involves him in product development from its earliest consideration. Ideas for apps can come from a variety of sources – colleagues’ own enthusiasms (the sophisticated materials developed around music draw heavily on the passions of their staff), or established content-rich organisations seeking to work with them (e.g., publishers such as Faber & Faber and Profile). But organisations that approach them with ideas for apps are partnered not commissioned; all ideas are rigorously strategised about how they might best be developed, not just packaged.

As marketing producer, Tom sees himself as the customer advocate, looking at the development of apps and what features and processes the customer might want to see included; this is based on both empathy with the kind of people who buy their products and extensive feedback on how their customers use them. Selling through retail outlets has long distanced traditional publishers from their customers and denied them feedback on how they used or enjoyed the item taken home. But as apps can only be bought from a single source – the Apple App Store, and they are so far only available for this single device – Touch Press gain a clear understanding of who is buying and how frequently (they get daily sales figures). What is more, they are able to monitor usage data in great detail to see which sections are most explored, the time spent on each, and observe overall patterns of engagement.

Price is an important part of the marketing matrix and its digital presentation enables it to be experimented with and learned from – and for this to be quickly achieved. While traditional retailers understand pricing points, above or below which the customer’s perception of value is affected, there are definite expectations for the purchasers of traditional publishing products of what books will roughly cost. Similarly, distinct ‘sweet spots’ are emerging for the selling of apps. For example, more will be sold at $4.99 than $3.99; more at $8.99 than $7.99. Interestingly offering material at a price of ‘free’ seems to change the relationship from one of transaction to one of technical involvement, and customers will often critically review material as ‘work in progress’ rather than simply appreciate receiving something for nothing. Mark Coker of Smashwords has confirmed the same experience for those offering ebooks free, whether as a pricing strategy or a limited special offer – ‘customers are often harsher in their feedback on titles they have downloaded free than those they have paid for’.12

Initially Tom’s team just announced the availability of new apps, largely online via YouTube and Twitter, offering links to longer blogs on websites. But having experimented with pre-releasing through the circulation of short promotional films, highlighting product usage and benefits (e.g., the Beat Map sound button that enables the listener to observe which parts of the orchestra are playing at any one time), they will continue this way. Smashwords too have confirmed the advantages of announcing ebooks as pre-orderable, and how pre-launch publicity can help build up market confidence and hence healthy initial sales figures on day one of official availability. Links to these promotional films are circulated via social media, and initial outline campaigns can be tested on a limited basis, and responses noted, before being rolled out more widely. They also offer free trials of their apps, a short extract so the market can experience what is on offer and make an informed choice about whether to proceed to purchase.

As regards the marketing messages, Tom’s team develop – and test – specific vocabularies that suit each brand, refining messages, clarifying and developing tone, and once established these are kept specific to the products in question. This is not a new idea – in the 1960s John DeLorean noted that the various car models available from General Motors all had their own associated vocabularies13 – but within the publishing industry it shows an unusual rigour. The long-term aim of refining the marketing messages, clarifying and developing their tone and effectiveness, is to build a lifetime value of the customer that is above the cost of managing the relationship in store (the retail price of the app less the discount to Apple on product plus the cost of servicing their account) and good judgements are made possible through the precise information on both how the marketing processes are working (pay-per-interaction and pay-per-view) and what is selling.

Purchasers of apps tend to be fairly affluent – because the device on which they are used is costly – and as a broad generalisation they are males and in the age range 25–45. The apps mainly get bought by the individuals who will use them, although a gift option is possible. There are limitations to the scheme as the potential donor has to know that the intended recipient has both an iPad and an iAccount. Touch Press’s product range has strong relevance to students of all ages and discussions are taking place about direct supply to schools and colleges.

The titles get reviewed in the app press and the book pages of national media now also offer a review section for relevant apps. Both offer opportunities for associated press advertising.

Again, specific feedback from actual campaigns can direct future expenditure and Touch Press have found that advertising tends to work best in the location where the apps are sold, and where there is a linear route from reading about the apps to buying them; the consumer route from print advertising to online purchase has not been particularly successful. The online ordering facility includes a review section, although it is frustrating that customers tend to use this for offering feedback on functionality and glitches rather than submitting it via Touch Press’s well-structured ‘Customer Support’ that comes as a standard part of app purchase.

Tom suspects that while awareness of different publishing companies and their various imprints is very strong within the traditional publishing industry, few outside it have much awareness of who publishes their favourite authors. Within app publishing, Touch Press promote themselves as creators of other apps their market may have heard of, or also own, and also through the brand names of those they partner with – e.g., Faber & Faber, Profile, The Science Museum, Deutsche Grammophon. They are trying to instil a sense of a Touch Press app as something special. They consistently build longevity into their products by insisting on highest quality – in graphics and resolution – so that when, as is inevitable, the platform hosting device changes, materials can be repurposed to fit.

The Elements was a book that became an app, Incredible Numbers and Skulls were both developed from apps into books and there are other possibilities for developing related product. But the organisation is conscious of the need to maintain the meaningfulness of their brand, adding value to content to make it something worth having. An app’s particular facility in ‘show not tell’ offers advantages in making complex subjects comprehensible, and it is important to offer customers extension material that adds value to their overall understanding and experience – and can hence be monetised to ensure the organisation’s sound development in future – rather than just because it is technically possible.

The biggest market for their apps is the US but Japan and China are catching up fast.

Translations have been created (16 different language editions exist for The Elements) but given that this is a product appealing to educated markets, and with a sophisticated multisensory nature, the potential remains for selling the original English edition to international markets. There is also scope for repurposing content for different groups, perhaps as specific and tailored experiences at much higher prices, in the same way that Nick Lovell suggests letting an organisation’s biggest enthusiasts spend as much as they like on fuelling a profitable business.14

This sophistication of delivery does not however currently extend to being able to offer different pricing models for different geographical locations. Apple’s agency model is a discount of 30 per cent and they require pricing within tight bands, and the application of the price established within all markets. It could be interesting to see regional variations explore different market thresholds.

Touch Press describe themselves as producing ‘living books that define the future of publishing’. While their focused passion for content delivery in new ways and technological expertise are both undeniable, it’s interesting to question whether in future such hubs of innovation within publishing will thrive best inside or outside the industry’s official portals.

Maybe innovation works best when developed by independent partners to the industry rather than lodged inside traditional companies, within which innovators can become isolated, and perhaps overwhelmed by organisational history and cultural emphasis on how things were formerly done. Or has the range of organisations involved in publishing just changed? Other instances of innovative content development can be cited that have grown independently before coming back to reinvigorate the traditional industry, as the original fiction series created by Working Partners15 for mainstream publishing houses has shown.

It would seem Touch Press also have much to teach the more established publishing industry about effective marketing. Their emphasis on its early involvement within the process of content delivery places the customer at the heart of the experience, a key principle of effective marketing. Their rigorous pursuit of consumer insight, based on a mixture of first-hand observation of the market and ongoing experimentation with isolatable variables, is worth much wider exploration. It offers the tempting prospect of cost-effective promotion to consumers about whom increasingly more becomes known.

In conclusion, within the general scope of a marketing role, it’s possible to be involved in a variety of different selling situations. The key is identifying the nature of the customer, their needs and matching this with the right sort of information and buying opportunity – in order to move them towards purchase.

Creating a sales proposition that others buy into