6 How to write a marketing plan

What have we got to sell? Researching the product

Who is it for? Researching the market

What benefits does the product/service offer your market?

Initial situation analysis: where are we now?

Establishing objectives: what do we want to achieve?

Developing a strategy: how will we get there, in broad terms?

Formulating a plan: how will we get there, in detail?

Developing marketing plans for individual titles

Allocating a budget: how much will it cost?

Communicating the plan to others

Motivating the implementation of the plan

A final checklist for marketing plans

Marketing planning is a structured way of looking at the match between what an organisation has to offer and what the market needs.

(Stokes and Lomax 2008)

Preparing a marketing plan is a common activity within the publishing industry and one on which many future developments may be based. Authors and agents take close note of prospective publishers’ ideas for marketing their work and, if choosing between rival offers, the associated marketing plans will be closely scrutinised. Retailers being asked to invest in new product lines will want to know the wider marketing planned by the publishers, in order to stimulate demand for products they agree to stock or promote. Authors may in the past have been resistant to talking about marketing, feeling their responsibility was for content alone and preferring to leave the marketing to their publishers, but today the sheer range of projects competing for the consumer’s attention means that the author’s ability to outline the market they are writing for, and help communicate with it, is a crucial part of a decision to invest in them. Unpublished authors seeking external investment are well advised to prepare a marketing outline in order to help potential publishers and agents understand where consumers may be found, particularly if this is a new area for publishing. Finally writers planning to self-publish need to think about how best to allocate their efforts and the ability to develop a marketing plan is a sound basis for further activity, whether they assign the ‘to do’ list to themselves or others.

But before discussing how to go about formulating a marketing plan, it’s worth stressing that while the thinking advised in this chapter can be used for plans of all levels of activity, from relatively straightforward organisation within the department to large-scale launches relying on external help, it is of little value if it is not subsequently implemented, or at least referred to. A marketing plan that sits in a drawer or on a computer is of little use. In this context it is helpful to think of a plan in three stages:

• Coming up with a plan.

• Communicating it to others.

• Motivating its implementation.

Most of the time and effort will go into the first stage, but the third one is the one that will probably need most effort and determination.

As we considered in Chapter 1, marketing is usually centred on the goals and requirements of the customer, so thinking about the market and what they need or desire should be firmly developed before refining the kind of products and services to be offered. On a practical level, the publishing industry has long been accused of being product-orientated rather than market-orientated, tending to commission the product and then think about to whom it will sell, and the reasons for this have been explored within Chapter 3 on market research.1 The user of this book, however, is more likely to be charged with the presentation of a specific product or service to a particular group of people, and this chapter is constructed accordingly.

Whatever your starting point, you need to be really clear about what your organisation is trying to achieve through marketing: to launch something new; raise the profile of an existing product; probe and eventually break into a new area of publishing? The best marketing is grounded in a clear understanding of the product or service in question, the target market and the wider situation in which you are operating. Only if you have this understanding will your copy be relevant and personal, and your marketing seen by those who need to read it in order to buy. Much research and thinking is needed before you decide on how best to allocate your efforts.

It can help to break down the planning into stages:

• What have we got to sell? Researching the product.

• Who is it for? Researching the market.

• Initial situation analysis: where are we now?

• Establishing objectives: what do we want to achieve?

• Developing a strategy: how will we get there, in broad terms?

• Formulating a plan: how will we get there, in detail?

• Allocating a budget: how much will it cost?

What have we got to sell? Researching the product

This means finding out all you can about the product or service you are to promote. Who is the author/provider of content: bestselling or unknown; always published by your house or new to the list; available at the time of publication for interviews or not; with other material in circulation? Look at the title. For example, Confessions of a Celebrity Minder will give you an idea of the content.

Is the content already available?

You will find that the delivery dates in contracts are not always kept by authors, and be wary of commencing work on a title if there is not yet a manuscript in-house. Even if the content is already with you, there will not be time to read every title for which you are responsible; the number of titles you have to look after will dictate the amount of time you are able to spend on each one. For example, a major new English scheme brought out by a primary education publisher should be examined in detail. If you have ten monographs a week to promote, looking closely at them all will be impossible and you will have to rely on what those commissioning the work have said about their reasons for doing so. Even if you don’t have access to the manuscript, talk to your editorial contacts to gain more information. Not everything of relevance finds its way from one department to the other.

What are you saying about it in-house?

Most publishing houses have an evolutionary cycle of forms, altered product details passing on to second- and third-generation versions of the original. As you look through these you will acquire an understanding of the title and how it has developed. At one stage in the cycle (perhaps with the ‘presentation’ form or ‘A’ form, the name varies from publishing house to house) it will have been brought before a formal marketing/editorial meeting and approved. Some titles are made available as an ebook first and then a decision on subsequently printing a run of copies will depend on how well this sells. If there is to be a printed run from the outset, the anticipated totals for the first- and second-year sales will have been made. These are your targets.

What did you say about it last time?

If you are promoting a book that is already published, look at previous marketing materials. Find out from the customer services department what the sales and returns patterns have been. Ask the reps what the market thinks of your product and, in particular, what they call it. You may be surprised.

If it’s the work of an author previously published by someone else, look at how they marketed it. Try to get copies of the promotion material they used. Was marketing one of the reasons the author decided to change houses? If so, what were their chief complaints?

Study the contents list

Ask yourself (or the editor) why the title was commissioned. What market needs does it satisfy? Are there any readers’ reports in the file (reports on the manuscript before a decision to publish was taken)? There should also be an author’s publicity form. The amount of time authors spend on compiling these varies, but a fully completed one can be an excellent source of information.

What does it cost?

Will the price attract (or rule out) any important markets? For example, academic libraries are more likely than individual lecturers to buy high-price monographs, but are there enough libraries in the market to make publication worthwhile? Corporate libraries may be able to afford the latest information, but can public libraries? By targeting your message to one market will you alienate another (and possibly larger) one?

Study the competition

Early in-house forms and the author’s publicity form should list any major competitors to a forthcoming title, or say if a publishing project has been started to meet a major market opportunity. Bearing in mind that the competition may not just consist of other books, start gathering information on what your product competes with and how the alternatives are promoted. Book fairs are a good time to collect other publishers’ information and catalogues. Consult their websites and see what they say, scan the relevant press for ads, and look at traffic on social media. You can pay a press agency to do this for you, but you will get a better general idea of the market, as well as early warning of any new competition, if you scan the relevant media yourself. Wherever possible register for electronic alerts with keywords to ease your search.

Look on retail websites and see rankings

Find out from your colleagues or boss whether any direct or teleselling has been done on this product or a related title in the past. As well as yielding orders you can gain a great deal of product information in the process. If the market is easily identified, try ringing a few prospects, or consult a directory for contact numbers. You will be surprised how many people find it flattering to have their opinion sought on the need for a new product. Librarians can be particularly helpful. See Chapter 8 for advice on telemarketing.

Ask the author

If there are still unanswered questions, ask the book’s editor about contacting the author. Be prepared; ensure that you have read all the information the author provided about their work before you ring. It’s irritating for an author to spend valuable time filling in a questionnaire only to be contacted by a marketing person who has clearly not read it. It may also be helpful to get the author to check your promotional copy. Similarly, the author may be able to help with testimonials or suggest individuals who might give the book a recommendation that you can quote in your marketing materials. The recommendation of one expert will be worth more than what you can think of to say.

Of course it can be daunting to ring an acknowledged expert on a subject you know little about. But just because you don’t fully understand the subject matter of the product does not mean you are an inappropriate person to handle its marketing. Indeed, you may even do a better job if your understanding is incomplete, because you are forced to take nothing for granted, and to ask basic questions: who is it for, what does it do and so on. In many ways, this puts you closer to the target market and allows insights into how best to position your product.

By now the project should be starting to come alive. Start refining your thoughts by answering the following questions about the content you have to promote:

• What is it?

• What does it do?

• Who is it for?

• Who needs it and what benefits does it offer?

• Does it fulfil any human needs?

• What is new about it?

• Why is this product or service being produced?

• Is it topical?

• Does it meet a new or discovered need?

• What does it compete with?

• What does it replace?

• What are its advantages and benefits?

• How much does it cost? What value does this provide?

• Are there any guarantees of satisfaction?

• Are there any testimonials and quotes you can use?

• Why was this author or content creation team commissioned? What is special about them?

• How reliable are they and how qualified to deliver?

• How worthwhile is it for the customer to invest in a relationship? What else is on offer to develop the relationship?

Several copywriting gurus have outlined basic human needs in the belief that any piece of marketing copy should aim to appeal to at least one. For example, to make or save money, time or effort; to help your family; to impress, belong or emulate others; to self-improve or attract attention, gain a career advantage; feel pleasure or be part of the Zeitgeist.

A new online business package may offer the reader a valuable competitive edge and the chance to extend their invoiceable services – and hence make money; a new novel may offer a temporary escape from reality. Take this a stage further by making a list of selling points, the respective features and benefits of the product, and then put them in order. Successful marketing comes from making the message credible and comprehensible: there may be lots of benefits, but potential buyers need only one to be convinced – the important thing is knowing which one. If you include them then all you may only confuse. Hang on to your workings, as a list of product benefits may be helpful if you are later preparing to meet the author or have to write a press release at short notice.

Who is it for? Researching the market

Market research, whether formal or informal, should have been of fundamental importance to the commissioning and development of your company’s products and services. You now have to find the groups of people who need what you have to offer before you think about how to persuade them to buy.

What is the market like?

What kind of people are they? Is the purchaser likely to be male or female; are there socio-economic indicators or area bias, and can these be related to the methods and media you choose? External help can be brought in here; for example, database and software companies can now offer very sophisticated socio-economic analysis of mailing lists. This is mostly done by postal or zip code analysis but can also draw on additional information such as the examination of house name or first name of householder.

Try to read publications the market has access to, both general interest and professional, and to meet some of the market. Can you go along to a professional meeting or annual conference? Once there, observe what goes on. Gathering this kind of information will help you to decide on the right promotional approach.

Questions to ask about the market

What needs does the market have? How will this product or service improve people’s lives? How much will they benefit? How much do they want it or need it?

– Who is the product for? Who will buy it? Who will benefit from it? Are they the same person?

These two sets of questions are not identical. Think of the advertising of children’s toys on television at Christmas, designed to encourage children to ask for the products that parents and other adults will buy. Equally for academic publishers, new materials may be preferred and recommended by those running modules but while they add the titles to their reading lists, most of the buying will be done by students. The only organisational copies bought may be some stock for the library or learning resource centre, and this will depend on organisational policy – some purchase textbooks, others regard the central budget as there for spending on supplementary reading material, not core texts. Other questions to consider are:

• How big is the potential market? How does this compare with how many you plan to print? What percentage of the market do you have to sell to in order to make the project profitable? Will the ebook market extend your overall sales and help you get material more widely known or reduce the number of print copies purchased?

• Once you have established the primary market, ask yourself who else might need the product. Is there anyone who certainly won’t buy it? (You can perhaps capitalise on this in your promotional information – ‘Is $500 too much to spend on ensuring your children have the most up to date resources to support their homework?’)

Segmenting, targeting and positioning

Marketing theory emphasises the importance of segmenting the market into different groups of people, and then targeting those most likely to purchase (or influence a purchasing decision). The marketing for a product can be segmented as follows in decreasing levels of interest. They are people who:

• can anticipate their need for a new product or service;

• have bought/used such a product or a related product before;

• need such a product now;

• used to but do so no longer;

• have never done so.

Your best strategy is to think carefully about what kinds of people are to be found within the first three categories (what other products have they bought; how much do they need what you have now?), investigate how to reach them (e.g., through your customer lists, social media activity and societies and memberships that reveal an affinity with what you are promoting) and then target them with a marketing approach. Once you have targeted them, and hopefully persuaded them to buy, you can then move on to trying to motivate them to enthuse about, or recommend, your product to others known to them. The power of positive word-of-mouth should not be underestimated.

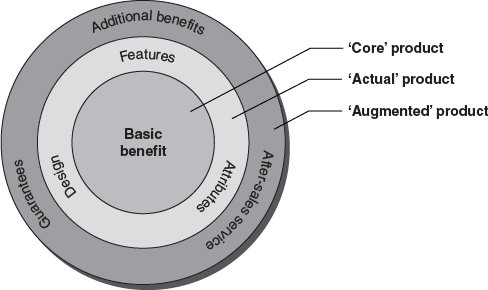

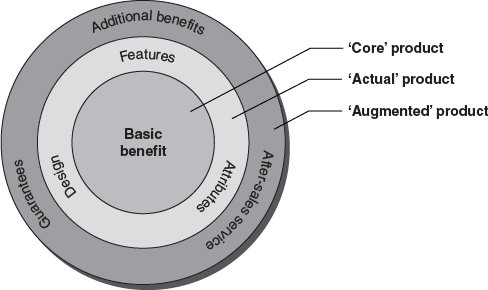

What benefits does the product/service offer your market?

Core benefit, the fundamental reason for acquisition.

Actual benefits, key features the customer expects, e.g., features, attributes and design.

Augmented benefits, additional benefits that add value to the core benefits, e.g., guarantee and after-sales service. This can be presented in diagramatic form, see figure 6.1.

An example of this in practice: a pencil

• Core benefit: enables you to write and hence communicate.

• Actual benefit: colour of casing; softness; hardness of lead; with a rubber on the end; weight in the hand; brand and style.

• Augmented benefit: free case, guarantee, three for two offer.

Then consider a product’s ‘positioning’. This is the emotional relationship that the would-be consumer has with your product and your brand. It is their perception of what your product stands for, based on the impression created by the words you use, and the image you create through design and promotional format. This psychological positioning can be created by linking to existing consumer perceptions, e.g., ‘the new Ian Rankin’, ‘the English Patricia Cornwall’, ‘the right wing John O’Farrell’.

Initial situation analysis: where are we now?

Marketing does not take place in a vacuum and in order to establish realistic and appropriate marketing plans, the wider environment must be considered. This can be broken down and analysed in various ways.

Figure 6.2 Figure showing how micro and macro fit together; adapted from Stokes and Lomax (2008: 38).

How an organisation (or individual) makes decisions is initially influenced by its own internal environment: its structure, objectives and resources. Next, its micro-environment consists of forces close to the organisation that affect its ability to serve its customers and over which it may have some influence. Examples may include the way in which it has conducted relationships in the past and hence the existence of latent goodwill, or strong established local relationships with retailers who have a long history of stocking and promoting merchandise.

The macro- (or external) environment involves larger societal forces that affect the whole of the micro-environment and over which an organisation or individual is very unlikely to be able to exercise influence. Macro-influences will include the wider business economy and events that affect all such as the weather or national sporting events that impact on the general mood.

Useful mnemonics exist for considering the forces at work. These include SWOT analysis and PESTLE, both of which are worth considering in more detail.

A SWOT analysis looks at the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of an organisational (or individual) position. Strengths and weaknesses are internal, specific to the individual; part of the past and present micro-environment. Opportunities and threats are external, deriving from outside circumstances; part of the present and future macro-environment. Figure 6.3 lays this out in a diagrammatic format for a new fiction imprint.

Figure 6.3 SWOT analysis diagram for a new fiction imprint.

Bear in mind that the weaknesses of your marketing position may be beyond your control or inherited. For example, have potential customers previously had bad experience of your delivery methods or turnaround times? Is there resistance to your packaging, such as how easy is it to open/post/recycle and how environmentally friendly? How ethical, diverse or generally likeable is your organisation? What is its brand image? What holding organisation/bigger firm are you part of? Are there any hidden ownerships, dodgy products or previous alliances?

PESTLE is a similarly useful strategic framework for thinking in more detail about the external influences within the current environment and those most likely to influence. It stands for a series of forces that need to be considered. Namely:

• Political factors might include local and national governmental policies and in particular any international agreements that are either established or pending. Within publishing, countries featuring in the news may spark demand for associated backlist titles.

• Economic factors may lead to alterations in income, prices and savings – and hence the market’s ability (or otherwise) to afford to buy. Overall market health and optimism may be affected by government policy on taxation, interest rates and national debt. Within publishing, the expansion of budget airlines and the development of airports as locations for shopping have boosted the number of customers available to airport bookshops, although the leasing of such outlets to chain stores means a more limited range of choice is being offered.

• Social factors may include changes in demographics (people living longer, certain diseases becoming more prevalent), changes in attitudes and lifestyles (new events to celebrate and rites of passage to mark) or cultural changes that affect us all (the hosting of the Olympics). Within publishing, the expansion of book clubs, both ones you attend in person and hosted by the media, has provided significant marketing opportunities for publishers.

• Technological factors may include the new or cheaper availability of technology, making the processes of marketing, administration and distribution swifter or less reliant on humans. There may be advances in materials, production processes or alternatives available that impact on the final product or service delivered. Within publishing, the availability of ebooks has not so far had a significant impact on the sale of paperbacks. People are building up a stock of material for their ebook readers, as well as buying paperbacks, or are perhaps spending more time reading.

• Legal factors may include existing legislation, planned future legislation and an awareness of pressure groups and associated lobbies. For example, pollution control or product safety legislation could impact on production planning, and disability legislation on the operation of buildings. Associated lobbies for alternative courses of action are often looking for case studies, and businesses affected by relevant legislation can find themselves highlighted as a result. Within publishing, the maintenance/removal of retail price maintenance, and the development of libel and copyright laws all affect the development and dissemination of content.

• Environmental factors may include geographical location and associated population impact, climate and climate change. Publishers are finding their market is increasingly aware of how paper used for production has been sourced; ebooks are presented as a more environmentally friendly option.

Many of the factors an organisation has to consider may not be this discrete; for example, lobby groups may raise awareness of environmental issues, which are then addressed by law and have a wider impact within society. Customers’ access to the internet may be influenced by both technology and environment and possibly by social factors (e.g., children lobbying for online access at home having got used to computers at school). But the isolation of these issues is a useful way of thinking in more detail about the wider environment for marketing plans.

Establishing objectives: what do we want to achieve?

Establishing objectives for marketing sounds deceptively simple (e.g., national media interest in a first novel; bestseller status by Christmas). The wiser approach is to think about where you want to be – or what you want to achieve – and then break it down into smaller quantifiable steps, ensuring that objectives are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-related).

Establishing objectives that are too ambitious or within a time frame that is unrealistic will demotivate; on the other hand, setting objectives that feel realistic and also mutually stretching may encourage everyone forward, particularly if the stages are achieved and celebrated. So instead of national media interest, a more useful objective might be to obtain positive features in two women’s magazines by the end of March.

Developing a strategy: how will we get there, in broad terms?

An organisational strategy is the long-term policy of an individual organisation accompanied by a broad understanding of how it can be implemented in order to be achievable. Marketing strategy can generally be divided into deciding where an organisation wants to concentrate its efforts, the segments that are most appealing, and then the process of targeting an approach to them through appropriate positioning of the organisation and its products to its market. It should include consideration of ‘what business are we in?’ (often presented as a mission statement), an awareness of priorities within that area and of the assumptions made, including that they may not be correct. This definition of the business we are in also defines the competition.2

Formulating a plan: how will we get there, in detail?

And so finally we come to what may be most recognisable as a plan; the practical implementation of strategy through decisions about how best and when to allocate resources to ensure objectives are met.

There may be different methods of doing the same thing – veterinary physicians, for example, may be reached by a mailshot sent to all veterinary practices, a space advertisement in a publication that is widely read by the group or a blog on a website they frequent. Increasingly social media is used to widen awareness; Twitter and Facebook are both influential and cheap. All are different methods of working towards the same goal, and the choices will depend on a range of factors from how often the market needs to hear from you in order to make a buying decision to the budget available.

Increasingly, a variety of overlapping methods of reaching the market are used, in a staged process. For example, for a high-priced product, with a strong anticipated sales level, there might be an initial email with a link to the organisational website, the subsequent despatch of a printed brochure and then a phone call to the customer to take an order (if the number and permission to call have been given). For mass market products the sequence might be a series of online messages with additional promotion via social media.

The plan will normally be a compilation of different marketing methods, based on understanding of how the market can best be approached.

A good starting point for a marketing plan is to make a list of all the standard promotional boosts received by every product published by your organisation. Not only will compiling such a list give confidence, it will also be useful when you have to speak to authors or agents about promotion plans for a specific title. (Often these standard promotional processes are so familiar that they are easily forgotten.)

If the task of setting up these procedures is yours too, the following ideas will be helpful.

Entry into relevant databases for the publishing business

Nielsen3 and Bowker4 accept information on forthcoming published titles and then make it available to others who need to know. Take particular care in how you describe your product as allocating it to the wrong category (e.g., healthcare instead of medicine, which means it would be seen by the general public rather than medical professionals) can mean the intended market miss being informed. Pay attention to how the market for this product or service may construct an online search for related information and be sure to include key terminology in your description (this is called ‘search engine optimisation’, see Chapter 5).

A website entry

Once a title has been decided on, unless there are strategic reasons for keeping quiet (you do not wish to let your competitors know what you are doing), then information will usually be added to the organisation’s website. This will include basic title and author details, an outline content, expected price and publication date.

An advance notice (AN) or advance title information (ATI)

This is usually in the form of a single sheet (sent by email and also available in printed format), includes all the basic title information and is sent out 6 to 9 months ahead of publication (see Chapter 5).

Inclusion in catalogues, seasonal lists and regular newsletters

Most general publishers produce two 6-monthly catalogues (spring and autumn); others produce a new titles list three times a year or even quarterly. Academic and educational firms usually produce a separate catalogue for each subject for which they publish. Catalogues generally appear 6 months before the books featured are due to be published, and are available in electronic and print format (although there are moves in some sectors to make them electronic only, see Chapter 5). Sections of the catalogue may be updated and emailed/mailed regularly.

Advertising

Are there any standard features in which all your firm’s titles are listed? For example, are there standard space bookings for the export editions/on the websites of the trade or professional press?

Despatch of covers to major bookshops and libraries

Your production department can arrange for extra book jackets and covers to be printed. If you have these stamped on the back with price and publication date they can form useful display and promotional items.

This term was coined by Tim Farmiloe, former editorial director of Macmillan. There are a number of other destinations for your material, which take varying amounts of effort to reach, but may result in extra sales. These include sending information to:

• relevant websites and bloggers, who may write/enthuse about your product. Some of these sites get huge audiences. For ideas on which sites to use, start with your authors, who are often bloggers themselves (see Chapters 9 and 11);

• social media. All kinds of publishing houses, even the highly academic, are increasingly active on social media to create relationships with their customers and promote sales (see Chapter 9);

• governmental and other relevant organisations; for example the British Council promotes titles from UK publishers abroad;

• professional organisations and trade bodies. If, for instance, you are producing a title on writing, there are many organisations that would-be writers can join, and each has a list of useful published material on its website;

• web retailers such as Amazon and Play, particularly if you can encourage purchasers to use the mechanisms provided for reviewing what they have enjoyed. Many offer referral marketing (‘People who bought this also bought’);

• various retailers and wholesalers who produce their own catalogues;

• relevant associations and groups (many have websites that list recommended publications);

• appropriate media and press to stimulate features or the demand for review copies (see Chapter 10).

The marketing manager of one major academic publishing house found that 95 per cent of its sales were achieved through such intermediaries.

Developing marketing plans for individual titles

The checklist above can be applied to all marketing planning. To make your ideas specific to individual situations and products, a number of considerations need to be thought through before you start.

Marketing format

Deciding on whether to produce an email campaign, a cheap two-sided flyer or set up a bespoke website is often where many marketing action plans start. It’s a much better idea to allow the decision on format to grow out of an understanding of the market and the product. For example, given absolute creative freedom to change format and words of an existing direct marketing piece you would be lucky to put up your response by more than 0.5 per cent. You’d probably be far better off reviewing the distribution of your materials, thinking through the product benefits in fuller detail or coming up with a new offer.

Nevertheless, armed with a marketing strategy to reach your customers, there is a lot of scope for lateral thinking on promotional format. Bear in mind that it is the slightly unexpected that secures attention. There are various ways to attract attention, such as different offers through email, different forms of social media, variously sized envelopes for mailshots, new sizes for space advertisements and so on (see Chapter 5).

Media planning

What are the best media through which to convey your promotional message? Should you use email, press advertising, posters, cinema, television and radio advertising, direct mail, display material, public relations, stunts, free samples? All are elements of the promotional mix, tools at your disposal.

Let’s take press advertising as an example. Which magazines and journals does your target market read? Consult the author’s publicity form and note where they suggest review copies should be sent. Talk to editorial and other marketing staff. Do you know any members of the market personally? If so, ask them what they think. Make a shortlist and look up the rates in a commercial directory or the magazine’s advertising website. If they are within your budget, ring up and ask for sample copies as well as details of the readership profile (useful ammunition when the publication starts pestering you for a booking and you want a reason to say no).

Before you make the decision to pay for space, consider whether it could come free. Is there an associated website or chatroom? Could you start a discussion about the subject of your book? Alternatively, is the magazine looking for editorial copy? Might it run something on your product as a feature article, perhaps offering free copies for readers to write in for?

If you decide to advertise, how can this be incorporated within your wider marketing plans; for example, how can attention be directed to your advertising spend via social media; can copies of the publication be available to your reps for distribution to key accounts? Do you plan to take a single space or a series? If there is one magazine or paper that reaches your target market, you will probably get better results from taking a series of advertisements, perhaps featuring a different product benefit each time, rather than spreading the same message over several different magazines. If you go for a series of adverts you should get a discount.

Having decided which media you will use, study them. Can you get yourself added to the free circulation list? Look through the pages. Which adverts do you notice? Is this because of effective copy and design, or placing? Where is the best place to be? In general, go for right-hand side, and facing text, never facing another advertisement (most people skip past double-page ads). Can you get space next to the editorial, or another hot spot such as the crossword or announcements of births, marriages and deaths? Space on book review pages may be cheaper than on news pages, but by opting for the former, will you escape the notice of a large number of your potential buyers? If you are planning to quote your website, is the relevant information ready, waiting for those who go online to look for it?

Read the letters, and look at the job adverts – a close examination of these will tell you who is reading the magazine. If it is a weekly, is any advertiser writing topical copy? Does the lead time allow for this? Is it paid or controlled circulation? When you start writing you should be aiming your message at one individual reader. Can you picture them? This should be your aim, before you start writing to them.

What you say

The words used in a marketing campaign are often referred to (when combined with appropriate design) as the ‘creative strategy’. The next chapters will provide ideas on how to make your approach relevant and effective, suggest new promotional themes and much more. For now I would just recommend that you nurture a general interest in all marketing copy. Don’t confine your study to the publishing trade press alone. Start looking out for copywriting and design techniques that do and do not work, and think why in each case. Keep two files, one of ideas you like (and can copy), the other of mistakes to avoid – bearing in mind that mistakes can often be more instructive. It is daunting to realise how much marketing effort (and expenditure) goes entirely unnoticed. Get on as many mailing/emailing lists as possible to see how other firms are selling.

I think good marketers see ‘good copy’ and ‘effective images’ everywhere and file them. You have to think deeply about the consumer and the best way to do this is to gauge your own response as a consumer and keep a record of what marketing really makes an impact.

Laura Summers, BookMachine

In addition to making your approach interesting and eye-catching you also need to consider whether it is:

• interesting?

• persuasive?

• clear? Do they know what is being promoted and the associated benefits?

• believable?

• motivating? And in particular, do they know what to do next – and how to order?

Keep copies of every piece of promotional material you produce, on- or offline, along with a note of how it performed. This will help you to plan marketing strategies in the future, and save you repeating expensive mistakes. Reading through such a file from time to time also acts as a valuable lesson in objectivity. You will quickly spot things you would like to change and, maybe in time, come to wonder if it really was you who wrote them!

Getting your timing right

When is the best time to promote to your market? Are there any key dates that must be observed – e.g., the start of the events that your products are being launched to commemorate, or the next academic year? When do you need your marketing materials to be ready by? Start working back through your diary, allocating time to all those involved such as designers and printers. See the sample schedule in Chapter 8 on direct marketing.

Planning too far ahead can be as bad as leaving too little time; it only allows everyone the chance to change their mind and the project to go stale. Responding and rising to the occasional need for marketing copy in a hurry is good practice, but in the long term this may block clear thought. Even if you are desperately short of time, try to let the copy sit overnight. What seems very amusing at 5.30pm may appear merely embarrassing at 9am the next day.

Allocating a budget: how much will it cost?

A budget considers the resources needed to achieve the plan: money, time, staff, etc. It should be related to the costs of reaching the market and the response needed in order to make this worthwhile. An estimated profit and loss for each campaign will usually be supplemented by consideration of the best possible/worst possible/most likely outcomes (Chapter 4 looks at costing marketing campaigns in more detail).

It’s worth noting that the actual budget is deliberately quite low down the list in terms of planning order, simply because too early consideration can limit your thinking; there is often a separate way of reaching the market that costs less.

You also need to consider:

• How much will the market pay and how will they pay? If they are buying for the organisation they work for, how much can they spend on their own account without having to get a second signature to approve the purchase?

• At what point will you break even? How many do you need to sell to cover your (a) marketing costs and (b) your contribution to the organisational overheads? You could do some break-even analysis by running ‘what if’ scenarios on spreadsheets.

Always be aware of the impression you are creating. Large promotion budgets do not necessarily lead to better sales – indeed, overly lavish material can directly contradict your sales message. For example, full-colour printed material to promote a product supposedly offering good value for money can lead the consumer to conclude that the price is unnecessarily high, pushed up by the cost of the sales message. On the other hand, when selling a high-price product through the mail, attractively produced promotion material, giving an impression of the quality of what is available and the beauty it will add to the customer’s home, is probably essential. Look out for the advertisements for high-price ‘collectable’ volumes that show the products beautifully lit in prestigious surroundings and the enjoyment therefore available to those who own them.

Sometimes it may be advantageous to make your message look hurried and ‘undesigned’. Stockbrokers who produce online ‘tip sheets’ deliberately go for a no-frills approach. If time has to be allowed for design and professional layout, the information is stale by the time it is received. Announcing an urgent meeting about an issue of local importance via a sophisticated leaflet would probably be counterproductive.

Communicating the plan to others

There will be those on whom you rely to execute a plan and those who need to know what you are doing in order to help the process

A common reason for plans failing is that insufficient resources have been allocated, and time and energy of colleagues are as important as money. Make a detailed list of the resources needed to implement your plans and discuss how these will be delivered before you start work – not at a crisis point. Draw up a timeline for who is responsible for what and when. Try to spot double bookings; the planned allocation of a part-time member of staff whereas in reality a maternity leave or leave of absence means the staff likely to be available will already be at full stretch. Try to consider early the various skill sets of the individuals involved and whether there are any gaps.

Whom to tell in-house

There is a range of other people you need to involve in what you are doing – and you will get the best effects if you consult them during the development of your plans rather than just inform them of what you have set up.

If you are going to fulfil the orders within your organisation,5 your marketing materials should offer an option for direct supply and hence feature your website, email address and telephone numbers. Ensure these are ready before any marketing materials are finalised and consult those who will handle the orders. Whether your distribution is handled in-house or by a third-party organisation, passing all your planned promotions to a colleague in customer services will win you friends and expose you to the feedback they regularly get but seldom know how (or to whom) to pass on. Similarly, does the website manager, organisational receptionist and those staffing incoming calls know what you are offering? If you set up an ‘out of office’ on your computer, have you really briefed those nominated to speak on your behalf on what to say? If calls come through to your department, has everyone who might answer your phone been briefed? Persuading other people to answer your telephone or deal with your ‘out of office’ emails can be difficult. Try offering an incentive, such as a points systems resulting in chocolates or wine for every order taken in the department. Leave a basic list of prices or details of the current promotion for all to consult when you are not there.

If the magazine in which you are advertising offers a reader-reply scheme, do you have something ready to send out to those who respond? Colleagues making telesales calls need administrative back-up to ensure what they promise in calls is backed up in practice – with the despatch of samples and the execution of paperwork to support purchase. All these things – and more – need thinking through beforehand.

Does your organisation have any reps calling on retail outlets or head offices to discuss stocking? If your marketing plans are likely to result in increased customer demand, it is vital that they know. As a result they may be able to persuade retail outlets to take additional stock and hence produce more sales. Even if there is no other news than your plans are simply up to schedule, do send a copy of each forthcoming promotion piece to the reps. It is embarrassing if the customers they visit know more about marketing plans than they do.

Motivating the implementation of the plan

Seeing a plan through to fulfilment imposes the need for monitoring and measuring the outcomes: breaking it down into manageable chunks, allocating responsibility and noting progress against what was intended. The monitoring needs to be regular and rigorous, but need not necessarily be formal – perhaps just organising a check-up meeting among all those involved once a week, and then having an action list afterwards so everyone is clear on the priorities. With monitoring need to come controls – formal arrangements for who is commissioning spending and committing future relationships, but also alerting points at which triggers will indicate more extreme action is required. These systems are best established before a campaign is launched rather than halfway through.

If there are particular circumstances that mean a project should not be evaluated against normal organisational monitoring procedures, these need to be highlighted early. For example, a publishing house may be working with a major client who sees distribution of a key resource to the student market as a long-term investment, and is supporting this development by paying all the development costs. Such a project might result in few recordable sales, the normal measure of publisher effectiveness, and hence risks being read inappropriately by management not informed of the project’s wider aims – or where the associated income would be recorded.

Evaluation is also vital for plans to remain relevant, both for effectiveness of communication (how many people were reached, what was their level of subsequent recall of the messages circulated?) and effectiveness of progress towards organisational objectives (dissemination of brand; market penetration targets; sales; budgetary objectives). Publishing is a notoriously optimistic industry and in the past can stand accused of having been unwilling to commit resources and time to evaluate campaigns, being in general too busy getting on with the next one. Part of monitoring a plan should be an ongoing referring back to objectives and hence feeding what was learned into the next campaign. Remember to use both internal and external sources of information, and to rely on a range of opinions, not just your own.

A final checklist for marketing plans

1 What are you trying to achieve and by when? What are the management expectations for this product/campaign? These are vital bits of information that will shape everything you do.

2 What is the product and how does it work/compete/improve with other solutions?

3 Who is it for? What are its key benefits to the market?

4 What is the organisation doing already? What standard promotional processes will take place, that you can benefit from, to get this product better known?

5 How, in addition, can you reach the market? Make a list of all possible vehicles including those you could not possibly afford (because you may be able to think of other means to achieve the same thing).

6 What budget is available? Is there any possible overlap with other titles, which means that budgets can be pooled and wider marketing gained for the backlist?

7 Which parts of the communication mix will you use? What other mechanisms do you have at your disposal (such as free and negotiated publicity)?

8 What can the author/content supplier do? Who else can you encourage to be an ambassador/enthuser?

9 What are the key dates and can these be formulated into a schedule? What must you have done by when?

10 Who must you inform about what you are up to, for both pragmatic and political reasons? Those you are relying on to handle resulting orders (customer services) as well as those dealing with feedback or even possible flack (PR staff) need to know what to expect, and you should always keep your line manager informed.

Case study

A marketing plan for the 5th edition of Inside Book Publishing by Giles Clark and Angus Phillips, by Samantha Perkins6

Publication date: 30 June 2014

HB: 978-0-415-53716-2

PB: 978-0-415-53717-9

HB: 978-0-415-53716-2

PB: 978-0-415-53719-9

RRP: £75.00, £24.99

Size: 246x174mm

Extent: 350pp

Initial print run: 2,000

The definitive text for all who need to learn about the publishing industry.

Publishing Training Centre

Primary market: Publishing Studies and Media Studies students.

Secondary markets: other newcomers to the industry, authors, publishers.

About the book

Inside Book Publishing is the classic introduction to the book publishing industry and has established itself as the bestselling textbook, becoming a staple of publishing courses and a manual for the profession for more than two decades … The book provides excellent overviews of the main publishing process, including commissioning, product development, production, marketing, sales and distribution (from the AN).

The website, www.insidebookpublishing.com, supports the book by providing up-to-date and relevant content, as well as offering research and news on the publishing industry.

Updates (from the AN):

The 5th edition has been updated to respond to the rapid changes in the market place and contemporary technology.

• Now more global in its references and scope. While based on the UK model, updates including international case studies and a globally relevant introduction make the book more suitable for international markets.

• The book explores new tensions and trends, including the rapid growth of ebook self-publishing and purchasing, and the breaking down of conventional models in the supply chain. And there is a greater coverage of digital and digital business models.

• The internet is now viewed as the primary channel to market for 5th edition.

• The book has been completely rewritten, particularly the marketing chapter.

• Abstracts have been added to chapters.

• New illustrations have been added.

About the stable it comes from

Part of the Routledge List – a range of high-quality resources for this market

Inside Magazine Publishing, Turning the Page, How to Market Books (Dec 2014), Inside Journals Publishing (Jan 2015), i.e., part of a strong list with an identifiable brand within a specific and developing discipline of Publishing Studies.

The Professionals’ Guide to Publishing, Davies & Balkwill (Kogan Page)

Routledge’s book is more clearly aimed at those taking a qualification in publishing and offers much more detail, particularly in digital publishing (from the AN).

The authors

Very strong team; one publisher and one academic – hence covering both markets.

Giles Clark: co-publishing adviser at the Open University and very well connected within publishing.

Angus Phillips: former publisher with OUP, now director, Oxford International Centre for Publishing Studies. Former chair of Association for Publishing Education and well connected in industry and academia.

Target market

Publishing and media students (UG and PG levels)

Size: 2.5 million UG and PG students in UK in (2011–12)7

UG students make up 77 per cent and PG 23 per cent8

The cohort of those studying publishing has tripled in size to 1,370 students in 2011–12, almost half of whom are postgraduates.9

Age range: 18–24 = 61.7 per cent

24–29 = 12.1 per cent

30+ = 26.2 per cent10

Spending habits:

• Outgoings have increased, but social spending is down since 2012.11

• Spend £22 per month on books,12 up £2 from 2012.13

• Four in five worry about money.14

• Students are brand loyal.15

• While the majority of the UK’s undergraduate students are now using ebooks, none are yet relying on them as a primary source of information. Print continues its hold as a key resource for at least two-thirds of students.16

• 88 per cent of undergraduates still use printed books and lecturer handouts … 48 per cent of students using printed books obtain them mainly from the library – more than double the amount buying them new or second-hand.17

There is little information on the spending habits of postgraduate students, but anecdotally they are inclined to spend more heavily on resources to support their course, particularly if they are using postgraduate education as a route to a career change.

Science and technology students

Skillset reports that 36 per cent of publishers believe that the biggest challenge facing the industry is a ‘lack of relevant skills within emerging workforce’.18 Publishers are increasingly looking for candidates with backgrounds that aren’t in arts and literature: ‘The industry’s continuous digital progression has increased the need to recruit individuals with a much more diversified set of skills.’19 While journal and academic publishers are increasingly interested in students with a background in science, the industry as a whole has a skills gap for technology and business-minded students.

In 2013, 47 per cent of graduates were working in non-graduate positions,20 with 13 per cent unemployed.21

Many students take a topic that interests them but don’t necessarily want to follow normal career paths for that topic, or change their minds. While others may find it difficult to find a job in their discipline with decreasing funding and stretched budgets.

Working in publishing offers graduates the opportunity to work with their specialist subject, just in a different industry.

Other potential users

These could include:

• those who want a career change (currently more likely with recent redundancy/job loss);

• those moving into the industry from other creative industries (e.g., coders, app developers);

• graduates who do not want to do a Master’s/PhD;

• those without graduate training, although most publishers now require degree-level education.

Many of these are likely to go on a publishing training course. It is also likely that they would consult a career adviser, recruitment agencies and relevant websites/blogs for advice on how to get into the industry.

Self-publishers/authors

Digital developments have led to authors being increasingly involved in the publishing process as social media, author websites and blogs have made the author’s brand and platform more important than ever as they are now in direct contact with their readers everywhere. ‘Self-published titles have grown by nearly 60% in 2012, and in 2013 it showed no signs of slowing.’22 These authors are increasingly ‘working hard to educate themselves like never before’.23 Phillips reported good feedback about the book from self-publishers.

The combination of new updates and its position as the publishing textbook will be appealing to established publishers who want to keep up to date with what their new recruits know. For the same reasons this will also be of use to lecturers in other creative or technological industries as: ‘More and more publishers are outsourcing to freelancers for help with editing, proofreading, illustrating, indexing and graphic design.’24

Market reach

• Publishing and other mentioned students can be targeted directly through lecturers who can recommend the title or put/keep it on their reading lists.

• Booksellers.

• Relevant newspapers and magazines.

• Websites and blogs for authors, self-publishers, publishers, careers advisors and recruitment agencies.

Current trends and affecting factors

• Reduced marketing budgets because of the recession and industry changes.

• Library funding cuts.

• Ebooks.

• Phillips reported that Waterstones keener on non-fiction as less affected by ebook sales.

• The recession will likely affect company and customer spending for the next few years.

• The rise of self-publishing.

Rights and international

‘Around a third of UK Publishers’ sales are exports’ (Clark and Phillips 2014: 9).

Routledge have ‘a dedicated international sales team’, with offices in Europe, Singapore, India and China. This should be exploited as much as possible.

Korean translation and edition for China this year.

Target the CIVETS (Columbia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey and South Africa).25

Recommendations

The following recommendations aim to provide maximum market reach at as low a cost as possible:

Table 6.1 Table of marketing plan recommendations. Courtesy of Samantha Perkins

*‘Understanding Book Publishing’, Publishing Training Centre, www.train4publishing.co.uk/courses/online-training/understanding-book-publishing (accessed 20 April 2014).

**Textbook Companion Websites. Routledge, www.routledge.com/books/textbooks/companion_websites/ (accessed 20 April 2014).

• All communication with channels to market should be individually targeted and persuasively written.

• Should encourage others to write reviews (e.g., Amazon) or publicise with social media whenever possible.

• Really push the idea of it being core/foundation text for publishing to attract students (and others) who are on increasingly tight budgets.

• Discuss marketing plan with the rights department and adapt the recommendations to international markets.

Notes

1 A complete discussion of these can be found in Baverstock (1993).

2 For further exploration of this area see Michael E. Porter’s five forces model of competition (1980, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, New York: Macmillan) and discussion since.

5 See page 192, ‘Postage and packing’ for guidance in this area.

6 MA Publishing 2013–14; this was submitted as an assignment within the ‘marketing’ module, for which she received a distinction. @sam_publishing.

7 ‘Patterns and Trends in UK Higher Education’ (Universities UK: London, 2013), www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/highereducation/Documents/2013/PatternsAndTrendsinUKHigherEducation2013.pdf (accessed 20 April 2014), p. 5.

8 Ibid.

9 Matthew, D. (2014) ‘Analysis: the subjects favoured and forsaken by students over 15 years’, Times Higher Education, www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/features/analysis-the-subjects-favoured-and-forsaken-by-students-over-15-years/2010435. fullarticle (accessed 20 April 2014).

10 ‘Patterns and Trends in UK Higher Education’, p.13

11 Ibid.

12 Butler, J. (2013) ‘Student Money Survey 2013’, www.savethestudent.org/money/student-money-survey-2013-results.html#2 (accessed 20 April 2014).

13 Butler, J. (2012) ‘What do students spend their money on?’ www.savethestudent.org/money/student-budgeting/what-do-students-spend-their-money-on.html (accessed 20 April 2014).

14 Butler, ‘Student Money Survey 2013’.

15 The Beans Group (2012) ‘Student Spending Report’, http://tbg.beanscdn.co.uk/ems/reports/reports/000/000/012/original/student-spending-report.pdf?1355871237 (accessed 20 April 2014), p. 7.

16 Bowker (2012) ‘British university students still crave print, says new BML study’, www.bookmarketing.co.uk/uploads/documents/pr_bml_bowker_student_survey_v1_YA68F.pdf (accessed 20 April 2014), p. 1.

17 Ibid.

18 Creative Skillset (2013) ‘Industry panel results: future skills survey’, http://creativeskillset.org/assets/0000/6529/Industry_Panel_results_Future_skills_survey.pdf (accessed 20 April 2014), p. 10.

19 Signorelli-Chaplin, K. (2013) ‘What skills do publishers need?’, The Publishers Association, www.publishers.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2415:byte-the-book-event-23rd-january-2013-what-skills-do-publishers-need-&catid=499:general&Itemid=1608 (accessed 20 April 2014).

20 Office for National Statistics (2013) ‘Graduates in the UK Labour Market 2013’, www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_337841.pdf (accessed 20 April 2014), p. 13.

21 Ibid., p. 5.

22 Palmer, A. (2014) ‘A look ahead to self-publishing in 2014’, Publishers Weekly, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/authors/pw-select/article/60783-pw-select-january-2014-a-look-ahead-to-self-publishing-in-2014.html (accessed 20 April 2014).

23 Ibid.

24 Wood, F. (2011) ‘The best books on publishing’, The Bookseller, www.thebookseller.com/feature/best-books-publishing.html (accessed 20 April 2014).

25 CIVETS, Investopedia, www.investopedia.com/terms/c/civets.asp (accessed 20th April 2014).