CHAPTER 3

A Creative Illusion

Two years before Darwin received Wallace’s stunning essay and realized that he would have to hurry up with the publication of his own ideas on the mechanism of evolution, an accidental discovery ignited controversy in Germany. Workmen who had been digging out a cave known locally as Feldhofer Grotto showed some of their finds to Johann Fuhlrott, a local schoolmaster and amateur naturalist.1

The cave was high up in a limestone cliff overlooking the Neander Valley, through which the Düssel River flows on its way to its confluence with the Rhine at Düsseldorf. Contrary to a widespread belief, the stream below the cave is not called the Neander. The name derives from Joachim Neander, a seventeenth-century theologian and teacher, who was relieved of his post at a Düsseldorf school because he refused to take Holy Communion. As he pondered his theological dilemma, he took frequent walks up the valley, and it became known locally as Neander’s Valley – Neanderthal.

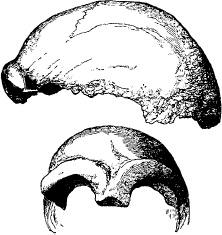

Then, in 1857, the valley itself presented a dilemma with theological implications. The workmen showed Fuhlrott some limb bones, part of a pelvis and, most strikingly, a cranium (the top part of a skull). They assumed that the bones came from one of the extinct cave bears, the remains of which they frequently found. Fuhlrott disagreed: it was certainly not part of a bear skull. He particularly noticed the extraordinarily pronounced supraorbital ridge, the bone that, in a double curve, runs horizontally across the face over the eye sockets. Above this bony ridge, the forehead was thick and sloped sharply back (Fig. 16). It was therefore also unlike a modern human skull. The limb bones, too, were especially robust. All the bones were encrusted with mineral accretions that, Fuhlrott knew, took a very long time to form.

16 The Neanderthal cranium found in 1857. This is how the sensational discovery was illustrated in T. H. Huxley’s book Man’s Place in Nature (1863).

After examining the bones, Fuhlrott set off for the cave, but he found no further specimens. He did, however, learn that the bones had come from beneath a thick layer of sediment. Unquestionably, they were decidedly ancient. But were they human, perhaps the remains of some diseased or mentally retarded person? Or were they of some other, non-human species that he could not identify? With no Darwinian concept of human evolution to guide him, Fuhlrott was baffled.

He therefore contacted Professor Hermann Schaaffhausen, a noted anatomist in the University of Bonn. Together, they presented descriptions and discussions of the finds at Bonn scientific gatherings on 4 February 1857 and, in more detail, in June of the same year. Schaaffhausen was a remarkable man, and the events in which he participated bore some resemblance to those taking place at the same time in England. Like many intellectuals of the period, he was leaning towards some form of evolutionary theory and had published his doubts concerning the supposed immutability of species.2 But he and Fuhlrott lacked Darwin’s and Wallace’s notion of natural selection, and they had to fall back on vague generalizations in their explanation of the bones from the Neander Valley. They suggested that they came from a ‘barbarous and savage race’ that co-existed with the extinct animals, the bones of which were well known.3 In tune with the burgeoning prescience of the time, Schaaffhausen wrote: ‘Many a barbarous race may…have disappeared, together with the animals of the ancient world, while the races whose organization is improved have continued the genus’.4 This is getting very close to a concept of human evolution and, moreover, natural selection. One has the feeling that an intellectual dam was about to burst; all that was needed to crack the wall was Darwin’s Origin of Species.

Needless to say, given all the other bitter controversies of the time, there were many who fiercely challenged Schaaffhausen’s interpretation of the finds. August Meyer, a pathologist in the University of Bonn, argued as late as 1864 – five years after the publication of Origin of Species – that the bones came from a Cossack soldier whose regiment had pursued Napoleon in 1814. Mortally wounded, the unfortunate man crept into the Neanderthal cave to die. The eminent anatomist Rudolf Virchow supported Meyer’s rejection of the find, and exercised his influential authority to prevent recognition of the discovery. Inevitably, one recalls what happened after the discovery of Altamira (Chapter 1).

On the other side of the Channel, the scientific climate was more receptive, thanks to the energetic work of Darwin, Lyell and Huxley. In 1863, Huxley himself recognized the importance of the Neanderthal finds in his Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature. In the same year, William King, a former student of Charles Lyell and himself Professor of Geology at Queen’s College in Galway, Ireland, coined the famous term Homo neanderthalensis – Neanderthal Man. The two-part Latin name indicates that King believed that the bones from the Neander Valley represented a species distinct from modern people, that is, from Homo sapiens.

Transition to modernity

King, Huxley and many others seriously pondered whether Neanderthal Man was a ‘missing link’ between ape-like ancestors and modern people. In doing so, they were the first to tackle the problems of what is now known as the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition, the time in western Europe when the Neanderthals gave way to fully modern people.5 Hereafter, I refer to this time simply as the ‘Transition’.

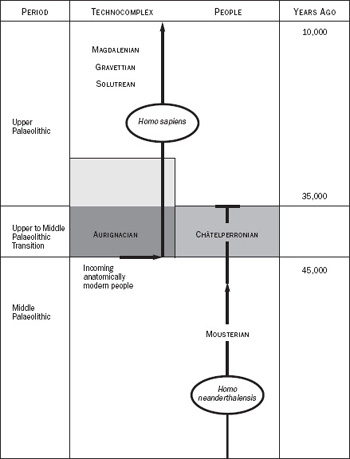

Before we examine some of the characteristics of this crucial time in human history, we need to be more precise about places and dates than we have hitherto been. At first, our discussion will centre on western Europe, especially southwestern France and northern Spain where the Transition is well documented and studied. In this region, the Transition took place between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago; the periods and dates of the west European Transition and the principal subdivisions of the Upper Palaeolithic itself are set out in Figure 17. At the end of this chapter, I consider evidence from Africa that predates the west European data; the syntheses of the African evidence that researchers are now making provide a better understanding of the Transition as it took place in western Europe. The picture of change in human society that emerges from this recent research throws new light on that aspect of the Transition that has been called the ‘Upper Palaeolithic Revolution’ and the ‘Creative Explosion’ – that time when recognizably modern skeletons, behaviour and art seem to have appeared in western Europe as a ‘package deal’.

As well as questioning the inevitability implied by the ‘package deal’ theory – that the whole indivisible package was simply part of the evolutionary process – we need to examine the kind of role that art played in the Transition, especially in western Europe. But first we must briefly return to the question of appropriate methodology.

17 A diagrammatic representation of the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition. Homo sapiens lived side by side with Homo neanderthalensis before the archaic species died out.

Most accounts of the Transition start with the climate and ecology of western Europe and then move on to human technology and thereafter to social organization, and end with a brief section on art, as if the making of images was to be expected and was, in any event, of no great consequence. The effect of this apparently logical approach is methodologically comparable with the one that Laming-Emperaire and Leroi-Gourhan adopted when they mapped the caves and plotted the locations of images on their maps: it carries with it the danger of predetermining a particular kind of answer (that was in all probability in mind from the beginning). Laming-Emperaire’s and Leroi-Gourhan’s structuralist and mythogramatic hypotheses were inevitably founded on the locations of species in the caves because that was the way in which they collected and handled their data (Chapter 2). They believed that their explanations derived from, rather than determined, their methods, but belief in such linear ordering of method and explanation is somewhat naive. Similarly, the descriptive chain favoured by many writers on the Transition tends to lead to the conclusion that ‘art’ (image-making, body decoration, music, dance) was a unified, symbolic or aesthetic component of a package that came at the end of a causal chain of environmental factors. The type of method that researchers employ thus determines the nature (if not the details) of the type of explanation that they eventually come up with.

In contrast to an explanation that sees art as an inevitable part of a symbolic package, I argue that art – let alone an ‘aesthetic sense’ – should not be seen as the simple result of something else, be it ecological stress occasioned by expanding ice sheets or social stress consequent upon the onset of glaciation. Rather, art-making, if and when it appears, is an active member of a dynamic nexus of interdigitating factors. Art was not simply a foregone conclusion, the final link in a causal chain. It was not the inevitable outcome of an evolving ‘aesthetic sense’, as some writers suggest. On the contrary, I argue that an aesthetic sense (if there is such a thing) was something that developed after the first appearance of art in the sense of image-making; it was a consequence, not a cause, of art-making, a consequence, moreover, that real people living in specific times, places and social circumstances constructed, not one that they inherited in the make-up of their brains.6

Contrasts

Bearing in mind these caveats about the relationship between method and explanation and, at the same time, questioning the supposed inevitability of art, we can now examine the changes that are observable in the west European archaeological record between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago – over and above the appearance of portable and parietal art, which is our principal interest. What caused these changes in the material evidence left by human communities is the question that we must answer.

The first point to notice is that the Transition cannot be explained by climatic change alone: human change was not the direct result of marked environmental change. The crucial period did see a colder climate peaking at about 35,000 years ago, but Neanderthals had survived previous climatic instability. During the Transition, vast ice sheets extended across the northern parts of Ireland and England, the whole of Scandinavia and parts of northern Germany. Separate ice caps covered the Pyrenees and the Alps. South of the polar ice sheet was a broad band of tundra and steppe – barren, windswept, treeless areas of frozen subsoil. The Ice Age reached its peak at about 18,000 to 20,000 years ago, long after the Transition. There were minor fluctuations during the period, as, for example, between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago. Throughout the time of glaciation, there would have been marked contrasts between summer and winter temperatures, but, overall, the temperature was as much as 10° C below today’s levels. During the winters, heavy snow falls would have made human movement difficult, but during the summers an absence of dense forests had the opposite effect: people could travel freely. Moreover, with so much water locked up in the ice sheets, the sea-level fell and parts of the North Sea were dry, thus affording access to England and Ireland. This land-bridge remained until the end of the Ice Age, that is until about 8,000 years ago.

The open tundra and steppe was inhabited by herds of bison, wild horse, aurochs and reindeer, as well as mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, creatures whose thick coats were strikingly adapted to the cold.7 These species were migratory, and the herds followed regular routes from summer to winter pastures and back again. For communities that could take advantage of these reasonably predictable, mobile herds, it was a time of plenty, and researchers estimate that, at least during the Upper Palaeolithic itself, population densities may have equalled those of the first agricultural communities.

Such was the setting for (not the cause of) the west European Transition: a stable climate, severe but with compensations. Before 45,000 years ago the anatomically archaic Neanderthals had this landscape to themselves. By 35,000 years ago they had vanished from France, and their place had been taken by anatomically modern Homo sapiens; the last Neanderthal outposts, isolated enclaves, hung on in the Iberian Peninsula until about 27,000 years ago. From Gibraltar, the last Neanderthals looked out across to Africa, their ancestral homeland, but a place by that time occupied by Homo sapiens. The earliest members of the incoming Homo sapiens communities are often called Cro-Magnons, after a site near the Dordogne town of Les Eyzies. This change from Neanderthals to Cro-Magnons is clearly discerned in the kinds of tool kits that the two groups made and used. We need consider the contrasts – and the overlaps – in tool types only briefly; it is the behaviour and identities of the communities that made the tools that are our chief interest.

Archaeologists have long defined periods of the Stone Ages by reference to types of stone tools and the ways in which they were made. The stone tool industry practised by the Middle Palaeolithic Neanderthals is called the Mousterian technocomplex; the earliest industry practised by Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens communities is called the Aurignacian technocomplex (Fig. 17).

During the Middle Palaeolithic, the Neanderthals used what is called the Levallois technique for flaking flint and other stone types (Fig. 18). This technique required preparation of core stones so that standardized flakes could be struck from them. The flakes were wide, fairly thick and heavy and were used for cutting, scraping and so forth; they were probably mostly hand-held. During the Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens communities manufactured much thinner and longer blades from distinctively conical cores of flint. Once detached from the core, these blades were often carefully shaped by further and finer flaking; they were probably hafted rather than hand-held. But the distinction is not absolutely clear-cut. Some Middle Palaeolithic people had begun to make more refined stone artefacts that can be called blades. What is important is that there was a proliferation of blade-making after the Transition.

Along with the new blade techniques of manufacture came a wider range of tool types. These include a diversity of spear-points, as well as a novel kind of scraper called an ‘end-scraper’ that was probably used for preparing skins and other such tasks. People also made burins (blades notched at one or both ends so that they could be used as chisels) for working bone, wood and antler. These new tool types suggest the adoption of new hunting techniques and more carefully made clothing. But many writers point out that some of the tool types, such as the finely made and highly standardized Solutrean points (Fig. 18), go well beyond functional necessity. During the Middle Palaeolithic, tool forms were much more uniform, and their function seems to have been paramount. It is as though, in the Upper Palaeolithic, the shape of the tool, not simply its function, began to matter. This development seems to imply that the forms of the tools symbolized social groups, within or between settlements.8 (Some researchers link this development to the acquisition of fully modern language, but that is a matter we can leave for the moment.) So it seems that Upper Palaeolithic people had a clearer, more precise mental picture of what they wanted their tools to look like, and that picture was linked to the social groups to which they belonged. But that is not all. Upper Palaeolithic tool shapes varied frequently both geographically and through time: the shapes of one’s stone artefacts (rather like a car today) signalled one’s social group. It is hard to escape the implication that society was diversifying and was much more dynamic than during the Middle Palaeolithic. If so, it is important to notice that human creativity and symbolism was linked to social diversity and change, not to stable, history-less societies. Change stimulates; homeostasis anaesthetizes.

18 Stone tool kits. The more recent artefacts are more finely made and include items made from bone, mammoth ivory and antler.

A new creativity is also seen in the exploitation of raw materials – bone, antler, ivory and wood. Whilst Neanderthals sometimes used these materials, they did not exploit their ‘malleability’: the new raw materials can be carved and bent into an endless variety of shapes. Quite suddenly, at the Transition, excavators of archaeological sites begin to find bone, ivory and antler awls, ‘batons’, beads, pendants, bracelets, ‘pins’ and exquisitely carved statuettes.9 As the American archaeologist Randall White puts it: ‘Aurignacian body ornamentation explodes onto the scene in southwest France during the early Aurignacian…It appears to have been complex conceptually, symbolically, technically and logistically right from the very beginning.’ 10 In other words, there was a kind of cognitive quantum leap.

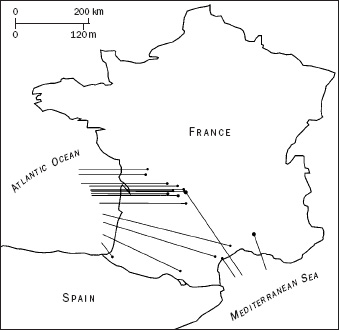

The techniques employed to make these objects were far from simple. For instance, stone burins were used to gouge out long splinters of bone or mammoth ivory that could then be fashioned into needles and so forth. Some of these objects are remarkably fine. For example, people collected fox, wolf and bear teeth and then carefully bored through the roots of the teeth to make pendants and necklaces. White argues that French sites such as Abri Blanchard, Abri Castanet and La Souquette seem to have been ‘factories’ where skilled artisans made beads and pendants according to complex sequences of techniques; the manufacture of items of personal adornment became an industry in itself.11 Remarkably, some beads seem to have been shaped to resemble species of seashells that were traded over considerable distances across southwestern Europe. Shells from the Mediterranean coast have turned up in sites in the Périgord area of France (Fig. 19).12 It would be rash to suppose that these exotic items point to long-distance movements of people. The selectivity, or ‘special-ness’, of the items suggests rather that they had exchange value and that it was the items not so much the people that moved. The value of the items was therefore social; they were not merely ‘trinkets’ or souvenirs picked up by aimless wanderers.13 As White14 points out, the ethnographic literature strongly suggests that the process of extended exchange had profound social implications.15 Some form of trade in items of decoration – and also in fine flint artefacts – was operating in the Upper Palaeolithic.

19 Upper Palaeolithic trade in seashells. The lines representing movements of seashells extend beyond the modern coastline because sea levels were lower at that time.

Trade, of course, implies social complexity and communication. Social integration beyond a nuclear family comprising parents and children is also evident in the organization of hunting, especially of migrating herds of bison, horse and reindeer. The steep-sided valleys of the Vézère and the Dordogne, for instance, channelled herds of animals migrating from the Massif Central down to the plains that lie to the west.Valleys such as these have high densities of Upper Palaeolithic sites. To take advantage of animal migrations, people had to be able to predict the times and places best suited to hunting and then to organize parties to be present at the right times and to perform different but complementary functions. Upper Palaeolithic people were also able to predict the early spring salmon runs when these fish swim upstream to spawn. Being at the right place at the right time meant a great harvest of fish that they could dry and store.Upper Palaeolithic people thus tended to concentrate on a single species, especially at certain times of the year; these included reindeer, wild horse and salmon. Some writers, such as the influential American archaeologist, Lewis Binford, have argued that the Neanderthals were, by contrast, merely scavengers and that they lived off the remains of kills made by carnivores and hence off a wide variety of animals over which they had no control.16 Others have challenged this rather extreme view and have argued that there are signs of planned hunting in the Middle Palaeolithic (some Neanderthal sites do show a focus on selected species). Either way, there can be no doubt that, at the beginning of the Transition, hunting became a much more effective and highly organized social activity.

Overall, in southwestern France, there are four to five times as many Upper Palaeolithic sites as there are ones dating back to the Middle Palaeolithic; the contrast is striking. We also need to note the presence of large Upper Palaeolithic settlements, far more extensive than any Mousterian sites. These settlements were probably aggregation sites.17 Communities split up into small bands during some seasons of the year and then united at recognized aggregation sites at others. Places of this kind were probably associated with rituals, such as rites of passage to adulthood and marriage.

Then, too, archaeologists have found evidence that points to increased social complexity within individual Upper Palaeolithic sites. Although postdepositional disturbance and superimposed series of Neanderthal occupations have blurred the evidence, excavations have shown that in some Middle Palaeolithic sites certain activities were performed close to a hearth; others were conducted closer to the periphery. Does this pattern indicate the early beginnings of a type of social complexity that we could call modern rather than archaic? Some archaeologists believe, probably correctly, that this kind of distribution was simply a matter of convenience and not a result of social distinctions. In support of their position they cite the distribution of activities in some chimpanzee nests18 and much earlier Lower Palaeolithic hominid sites. By contrast, living structures and spatial differentiation are common in early Upper Palaeolithic sites. There are, for instance, stone arcs and postholes in the Arcy-sur-Cure site that probably supported discrete shelters.19 Perhaps the most impressive evidence comes from Pincevent, an open-air Magdalenian site some 60 km (37 miles) southeast of Paris. Here, researchers, initially under the direction of André Leroi-Gourhan, uncovered a large settlement area with numbers of hearths and evidence for shelters. Analysis of stone tools and bones indicated relationships between these nodes. Such complex settlement patterns suggest that Upper Palaeolithic people had more precise ideas about the spatial distribution of activities and people within sites than did their Middle Palaeolithic predecessors and that they distinguished between social categories of people.

There is thus evidence, right from the beginning, for an Upper Palaeolithic mental template (or structure) that controlled (but which people probably also contested) the way in which sections of society interacted with and left their mark on available living space. Society superimposed its social and technological divisions on space: different categories of people were visibly distinct within the area of a camp. People’s movements between designated areas made powerful, visible social statements about belonging to or differences between groups. Space thus became a malleable template that people constructed to express, to reproduce through time, and also to challenge social order and divisions. This is a point that we must bear in mind when, in later chapters, we consider the diverse ways in which Upper Palaeolithic people adapted the topography of deep caves for arcane purposes.

Social differentiation is also implied by elaborate Upper Palaeolithic burials, such as the astonishingly rich ones at Sungir in Russia.20 At this extensive living site, approximately 150 km (95 miles) east of Moscow, archaeologists have excavated five burials (though two are partial); they are probably as much as 32,000 years old.21 Randall White, one of the few Western archaeologists to have studied the material first-hand, believes that Sungir can be seen as a northeastern extension of the Aurignacian. Two of the burials are of adolescents laid in shallow graves dug into the permafrost; the corpses were placed on their backs with their hands folded across their pelves. One of these bodies, said to be that of a boy, was covered with strands of beads, 4,903 in all; he also had a beaded cap with some fox teeth attached. Around his waist was the remains of a decorated belt with more than 250 canine teeth of the polar fox; a simple calculation shows the minimum number of foxes (63) – animals that must be individually trapped or hunted – required to supply so many teeth. In addition, the boy was buried with a carved ivory pendant in the form of an animal, an ivory statuette of a mammoth, an ivory lance made from a straightened mammoth tusk, a carved ivory disc with a central perforation, and other items. The lance was probably too heavy to have served a practical purpose. The adjacent burial, said to be that of a girl, was accompanied by no fewer than 5,274 beads and other objects. If White22 is correct in estimating that it took more than 45 minutes to fashion a single bead, the beads in this female burial took more than 3,500 hours to make.

This brief description gives but a glimpse of the richness of the Sungir burials. Nevertheless, it is clear that, at Sungir, selected people were buried with grave goods that suggest social ranking or leadership of one kind or another, but that was not necessarily linked to age. People used meaningful items, such as fox teeth, to construct their identities in life and to construct a special, perhaps enhanced, identity for specific dead. The high status that these young people enjoyed may have been inherited, but it may also have been acquired in a manner similar to the selection of a Dalai Lama. Moreover, the sheer quantity of the grave goods suggests that the items were contributed by an extensive social network, not by a single family. This was no simple, isolated, egalitarian hunting band.

That said, we must allow the possibility that in cases such as the extraordinarily rich Sungir burials people may have ‘robbed’ earlier graves in order to provide goods for later ones, as apparently sometimes happened in ancient Egypt. The rich Upper Palaeolithic burials may therefore point not so much to individual status but to cumulative status, perhaps through a descent lineage of one kind or another. Either way, we cannot doubt that these burials suggest the functioning of complex societies.

Neanderthal burial practices are much more controversial than those implied by sites such as Sungir.23 The Neanderthal archaeological evidence itself is often questionable, the excavations having been undertaken a long time ago. Still, it seems unlikely that all the supposed Neanderthal burials could have been accidental, as has been suggested. One reason for accepting a limited number is that the skeletons have remained articulated. Their completeness indicates that they were deliberately placed in the ground and thus protected from human, animal and physical factors that would otherwise have scattered the bones. This judgment is, however, not the final word in the controversy. Robert Gargett, in a detailed re-examination of the evidence, has concluded that there are ‘natural depositional circumstances in which articulated skeletons might be expected to occur’ and that these conditions are in evidence in all cases of claimed Neanderthal burials.24 If this is so, it is not clear why no other articulated animal skeletons of creatures that could be expected to die in a rock shelter have been found. It seems that we must leave a question mark over some but not all the Neanderthal ‘graves’.

On the other hand, the evidence for Neanderthal grave goods, or ‘offerings’, is unquestionably weak, a point on which there is major agreement. When, or if, they did bury their dead, they did so without the complex accompanying rituals that Upper Palaeolithic people often (though perhaps not always) practised. In sum, it seems likely that some comparatively late Neanderthals may have buried their dead, though there is little evidence in any of these burials to suggest ritual or religious beliefs; burial alone might have been done for hygenic reasons if people did not wish to abandon a rock shelter in which someone had died. This is, in the context of our enquiry, a highly significant point.

It is important to recall that all the diverse and sophisticated Upper Palaeolithic activities that we have noted did not proliferate gradually or severally in western Europe. They all seem to appear right at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic, though some may have intensified in later periods. At one time some researchers believed that art, both portable and parietal, was somewhat different from other components of the Upper Palaeolithic package in that it started hesitantly, evolved gradually through the Upper Palaeolithic and reached its apogee during the Magdalenian. Breuil25 argued that this trajectory was characterized by two stylistic cycles, each starting with ‘simple’art and evolving into more complex images. Leroi-Gourhan, 26 on the other hand, postulated a single stylistic cycle moving from simple to complex.27 The 1994 discovery of the Chauvet Cave put paid to that misapprehension.28 The sophisticated, ‘advanced’ images in that cave have been dated to just over 33,000 years before the present, that is, within the Aurignacian, the earliest Upper Palaeolithic period. This early date should not really have come as a surprise to archaeologists because the finely carved statuettes found decades earlier at Vogelherd and Hohlenstein-Stadel in southern Germany had been dated to the Aurignacian.29 These carvings include representations of horses, mammoths, felines, and a remarkable therianthropic statuette that has a human body and a feline head (Figs 45, 4646). One of them in particular, an exquisite image of a horse, is polished as if it had been carried around in a pouch or, perhaps, fingered in a ritual; it also has a clean-cut chevron that was incised on the shoulder after the horse had been polished.30

There can now be little doubt that – in western Europe – the Transition saw a range of marked innovations, nearly all of which imply mental and social changes of great significance. Upper Palaeolithic people were behaving very differently from their Middle Palaeolithic predecessors, and these changes can be dated back to the beginning of the Aurignacian. We can understand why many researchers speak of a ‘Creative Explosion’. So far, their case looks strong.

Causes

Researchers have advanced two explanations for the changes that we have now examined. These contrasting explanations hold very different implications for our enquiry into the origins of art and, more especially, into the proliferation of subterranean cave art during the west European Upper Palaeolithic.

On the one hand, some researchers argue that local Neanderthal populations gradually evolved into anatomically modern people.31 Others argue that there was a fairly swift replacement of Neanderthals by anatomically modern Homo sapiens who migrated across Europe, both north and south of the Alps, and ended up in southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula. This has been a highly controversial issue, but I believe it is fair to say that, today, most researchers favour the population replacement explanation. We need not rehearse all the data and positions involved in this debate. Instead, I briefly note five important points that persuasively favour the replacement hypothesis. We shall then be able to move on to the intriguing implications of Neanderthals living for perhaps as much as 10,000 years in proximity to incoming Homo sapiens communities.

l A clearly Neanderthal skeleton at the site Saint-Césaire has been dated to 35,000 years before the present, in other words, to the very end of the Transition. Other Neanderthal remains, at Arcy-sur-Cure, have been dated to 34,000 years before the present.32 Finds in the Iberian Peninsula suggest a pocket of surviving Neanderthals as late as perhaps 27,000 years ago. If Neanderthal populations lasted this long, there would simply not have been enough time for them to evolve into anatomically modern people.

2 Fully modern skeletons have been found at the sites of Qafzeh and Skhul in Israel and have been dated to as early as 90,000 to 60,000 years before the present. As we shall see, Israel is on the route that fully modern people would have taken on their way to western Europe. Without doubt, anatomically modern populations existed some 50,000 to 60,000 years before they begin to register in the west European archaeological record. In other words, they did not evolve out of west European Neanderthals.

3 New DNA evidence suggests that the anatomically archaic Neanderthals did not contribute significantly to the genes of modern populations and, moreover, that the two types did not interbreed.33

4 The Aurignacian technocomplex, the one that characterizes the first fully modern populations, extends with remarkable uniformity from Israel all the way to the Iberian Peninsula. Such a wide spread is better explained by fairly rapid migration than by local, evolutionary developments from geographically scattered and somewhat different Mousterian industries.

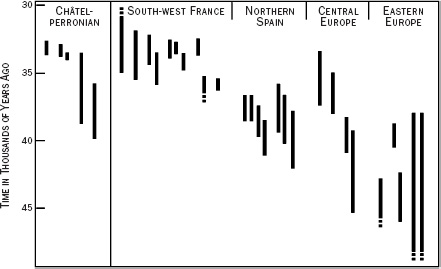

5 Lastly, and convincingly, dates for Aurignacian settlements from eastern Europe through to western Europe become more recent as we move towards the west – which is what we would expect if Homo sapiens communities moved in this direction. The Cambridge archaeologist Paul Mellars has usefully collated the dating evidence to show this temporal sweep across Europe (Fig. 20).

Clearly, the replacement hypothesis answers the criteria for successful hypotheses (Chapter 2) better than local evolution. Yet, despite all these and numerous other points, the debate is not dead. All the evidence, but especially that from the rich Arcy-sur-Cure site, was aired and discussed in a 1998 Special Issue of Current Anthropology. Francesco d’Errico and four colleagues argued for independent development of the Arcy-sur-Cure Mousterian into the Châtelperronian, an early Upper Palaeolithic technocomplex that I describe below.34 Nine specialists contributed to the debate. Whilst most expressed sympathy with a research programme that re-evaluates this important site, the broad consensus was that the distinctive features of the Châtelperronian developed as a result of contact with in-coming Aurignacian communities.

20 Dates showing movement of Homo sapiens communities across Europe from east to west; the oldest dates are in the east. The bars represent the ranges of dates from specific sites.

Responding to the Current Anthropology debate, Mellars has effectively summed up the position.Referring to recent dates, he points out that they leave

entirely open the possibility that the appearance of a range of distinctively ‘modern’ behavioural features among the late Neanderthal populations of western Europe – including the presence of simple bone and ivory tools and perforated pendants at Arcy-sur-Cure – was the product of some form of contact and interaction between the two populations, regardless of whether we refer to this as ‘acculturation’, or by some other term. The alternative is that after a period of around 200,000 years of typically Middle Palaeolithic technology and behaviour, the local Neanderthal populations in western Europe independently, coincidentally, and almost miraculously ‘invented’ these distinctive features of Upper Palaeolithic technology at almost exactly the same time as anatomically and behaviourally modern populations are known to have expanded across Europe.

The notion of population replacement brings us to what are perhaps the most fascinating questions of all. If anatomically modern people moved fairly swiftly into western Europe, they must have encountered and even lived alongside Neanderthal communities. How did these two groups regard one another? Did they interact? If so, was their interaction violent or peaceful? Did they learn from one another? Could they communicate by means of language? In what, if any, ways did their minds/brains and type of consciousness differ? Could interaction between archaic west European Neanderthal and anatomically modern communities in some way have triggered the efflorescence of art that we find in that region? We have no historical record whatsoever of two species of Homo living side by side to guide our thinking: for the last 35,000 years only one species of human beings has occupied the world.

To answer some of these questions, we concentrate on the early Upper Palaeolithic technocomplex known as the Châtelperronian (Fig. 17).

New neighbours

The archaeological record in western Europe shows that the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic was characterized by two distinct groups of people who made different kinds of artefacts. The Homo sapiens people, who moved from the east into western Europe, brought with them the Aurignacian tool kit, the art and new ideas that we have already noticed. Then, for the first 5,000 years and more of the Upper Palaeolithic, the Châtelperronian, a technocomplex associated with Neanderthals, flourished in the Dordogne, southwestern France and parts of the Pyrenees.35 During that period, there was undoubtedly contact between the Aurignacians and the Châtelperronians. At some sites, such as Roc de Combe and Piage in the Dordogne, Aurignacian strata are interstratified with Châtelperronian strata:36 it is therefore clear that the two cultures not only co-existed but that they also occupied the same rock shelters alternately. By 35,000 years before the present, the Châtelperronians had disappeared and the Aurignacians had the landscape to themselves.

We should not envisage this process of replacement as an inexorable wave sweeping across Europe. Rather, we should think of a series of ‘steps’ or ‘jerks’.37 Discrete, advance colonies of Homo sapiens appeared, expanded and coalesced as the people struck out from one ecological locality to another. At the same time, the Neanderthal population was contracting according to its own dynamic. Co-existence was therefore probably not a universal feature of the replacement process. But that there were areas, especially central France and the Pyrenees, where Neanderthals and Homo sapiens lived side by side for some thousands of years is a scenario about which there is no doubt.

What happened during the period of overlap? We need to distinguish between the evidence of stone tools and that of human physical types.

Strong continuities between Mousterian and Châtelperronian stone tools and the ways in which they were made are evident (we need not go into the details).38 For instance, it has long been thought that the Châtelperronian curved, blunt backed flint knives derived from the naturally backed knives characteristic of the Mousterian.39 It thus seems that the Châtelperronian stone industry developed out of the Mousterian. It is also clear that the Châtelperronian was associated with Neanderthals.40 By contrast, no Aurignacian sites are associated with Neanderthals. There is in fact a clear, decisive break between the earlier Mousterian and the intrusive Aurignacian in both artefacts and hominid types. The Châtelperronian can therefore be seen as a terminal expression of the Mousterian, both industries being made by Neanderthals, while the in-coming Aurignacian technocomplex was independent of the local Mousterian and was made by Homo sapiens (Fig. 17).

In eastern Europe and the Italian peninsula there are two technocomplexes comparable to the Châtelperronian. They are, respectively, the Szeletian and the Uluzzian. Both seem to have developed out of earlier Mousterian industries, and both extend into the Aurignacian period. They appear to be local responses to the juxtaposition of Mousterian and Aurignacian communities.41 We shall, however, concentrate on the Châtelperronian of western Europe because it is there that the great flowering of art took place.

There are some highly significant parallels between the Châtelperronian and the Aurignacian that complicate any simple explanation that proposes exclusive origins for the Châtelperronian in the Mousterian. There is, in the Châtelperronian, a strong component of blade technology that seems to have come from the makers’ Aurignacian neighbours, not out of their Mousterian ancestry. There are also end-scrapers and burins, as well as items made from bone and antler that show a technology that seems to have originated in the Aurignacian industry rather than in the earlier Mousterian. Perhaps most interesting are items of personal adornment, especially grooved and perforated animal teeth, and abundant pieces of red ochre that may have been used for body decoration.42

All these borrowed features developed at a late stage of the Châtelperronian, long after the first appearance of the Aurignacian in western Europe. Were they spontaneous developments among the Châtelperronian Neanderthals, or were they the result of selective imitation of, and exchange with, Aurignacian communities, that is to say, a consequence of acculturation?43 As we have seen, most researchers now believe that the best explanation for the combination of inherited and the borrowed features evident in the Châtelperronian is that there was a process of acculturation that resulted from contact between the two species of Homo – Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis. The precise nature of that contact is more debatable. We need to consider it now. Thereafter we shall examine the significance of those Upper Palaeolithic features that the Neanderthals did not adopt. As we shall see, they are more instructive than those they did adopt.

Interaction

The first scenario for contact between the Aurignacians and Neanderthals that springs to many people’s minds is violent conflict, an early form of genocide. They imagine Aurignacian hoards rampaging through the land, viciously destroying all the slow-witted Neanderthals they found. The actuality was probably rather different. There were probably many ways in which the two groups interacted at different times and places.44

To be sure, it seems unlikely that there was no conflict at all, but it was probably intermittent rather than sustained genocide. When there was conflict, it seems likely that it was the Homo sapiens men who killed the Neanderthal men and ravished their women. But the Homo sapiens communities were intelligent enough to realize that the offspring of such unions would be infertile and probably mentally inferior to themselves.45 How would the Homo sapiens communities have regarded such offspring? At this point imaginative reconstruction of what bi-species society was like reaches its limits. We need to turn to the archaeological record for more substantial clues than imagination alone can provide.

Writers such as Clive Gamble46 have pointed out that, certainly at first, the in-coming Aurignacians may have sought different kinds of landscape to exploit from those favoured by the Neanderthals. It seems that, at first, the Aurignacians moved around a Neanderthal pocket that hung on in the Dordogne. If the Neanderthal and Homo sapiens hunting strategies were different – the Neanderthal’s being more general than that of Homo sapiens who, as we have seen, tended to focus on single species – competition for resources and particular kinds of landscape may have at first been rare.

Different hunting strategies in turn suggest different social structures. Gamble47 has subtly developed this implication. He explores the effects of different kinds of social networks for the two groups. In brief, he argues that, in Châtelperronian society, contact was face-to-face: people met other people and exchanged artefacts and information. By the production of symbolic artefacts that signified different social groups and kinds of relationships, Aurignacian people were able to maintain wider networks that could exist even between people who had never set eyes on one another. If the Aurignacians were able ‘to go beyond the confines of face-to-face society and achieve wider system integration performed across a social landscape’, 48 they would have been able to construct a geographically wider power base. As a result of their more complex networks, ‘individuals were both constrained and enabled in the scale and effects of their actions over others’.49

Because they were able to forge symbolically sustained networks and fields of power, the Aurignacian population built up. Eventually, competition for resources became more intense and perhaps violent. If we recall that at the time of the Transition there was a comparatively cold period and that Neanderthals had survived such problems before, we can isolate a major difference between those earlier cold periods and the Transition: at the Transition there was another human species on the landscape and therefore greater competition for resources. Even small disadvantages, such as higher infant mortality, can tip the balance. If Homo sapiens communities were able to store food through the winter and the Neanderthals were not able to do so, Homo sapiens child survival rates would have been more advantageous.

Ezra Zubrow50 has studied the effects of such relations on population densities and reproduction. His conclusion is surprising: ‘a small demographic advantage in the neighbourhood of a difference of two per cent mortality will result in the rapid extinction of the Neanderthals. The time frame is approximately 30 generations, or one millennium.’ 51 Here, then, is an explanation for the rapid extinction of the Neanderthals that does not depend on calculated, purposeful genocide. A small demographic imbalance will produce the same result.

We cannot leave this question of interaction without some reference to language. There is no doubt in any researchers’ minds that Upper Palaeolithic people had fully modern language – that is, they were able to create arbitrary sounds with meanings, to manipulate complex grammatical constructions, to speak about the past and the future, to convey abstract notions, and to utter intelligible sentences that had never before been put together. What is at issue is whether the Neanderthals also had fully modern language or whether they had a more rudimentary type of proto-language.52 Another point of controversy is whether proto-language evolved gradually or suddenly – ‘catastrophically’ – into complex modern language.53

These are hotly debated questions, but they need not impede our discussion; we do not have to answer them before we can move on to issues concerning Upper Palaeolithic art. Still, they are intriguing. Because I accept that language is closely related to social complexity – in broad evolutionary terms, the more complex the social relations of a species, the more complex its language and communication systems – I am inclined to accept that the Neanderthals had a comparatively simple form of language. This notion may be difficult for us to grasp because their language would have been compatible with a type of consciousness different from ours (Chapter 4).

To what extent Neanderthals would have been able to communicate linguistically with Homo sapiens people is a moot point that researchers have insufficiently explored. I think that there would have been the possibility of certain kinds of linguistic communication that did not presuppose fully modern consciousness on the part of the Neanderthal auditors.54 The incoming Aurignacians brought modern language with them;55 the Neanderthals may have learned to understand at least something of what they were saying and thereby even to have improved their own linguistic skill to a certain extent – as they did their flint-knapping. The Neanderthals’ potential for language may have been greater than their social environment had so far required. Verbal communication between the two communities would therefore have been possible at a fairly straightforward, day-to-day level – perhaps the Neanderthals learned to speak a kind of ‘pidgin-Aurignacian’ – but the Aurignacians would have found it impossible to convey notions that the Neanderthal mind simply could not entertain.

So far we have considered social networks, demographic patterning and communication. Can we go further in our investigation of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens interaction?

What Neanderthals did not borrow

At this point we need to break down the comprehensive, ragbag word ‘art’ and to distinguish between different kinds of visual arts (song, dance and mythtelling do not concern us at the moment). We need to distinguish between those kinds of art that can interact to produce viable new forms and those that cannot evolve into other types. Fundamentally, I argue that an art form such as body decoration could not have evolved into the making of two-dimensional images of animals on cave walls.

The use of red ochre and a range of body adornments were, I argue, kinds of art that the Neanderthals were able to imitate. In some circumstances they may have literally acquired Aurignacian items of decoration by exchange or stealth.56 These kinds of art are closely related, and none places more intellectual or cognitive demands on the user than any other; they all presuppose the same range of cognitive abilities. Further, they may have ‘interbred’: one kind may have spawned another, or at least have influenced the form of another. But we cannot leave the matter of body adornment there.

An important point that has received insufficient attention is that the stone tool types and technologies that the Neanderthals took over were probably used for the same practical purposes as the Homo sapiens people used them – cutting meat, scraping bone, preparing skins, and so forth.Was this also true of body adornment? To answer that question, we need to note that body decorations are not simply ‘decorations’, the fruit of personal whims; on the contrary, they signify social groups and status. ‘The surface of the body…becomes the symbolic stage upon which the drama of socialisation is enacted, and body adornment…becomes the language through which it is expressed.’ 57 Social identity changes through life: people move from adolescence to adulthood, from unmarried to married, from child-bearing to post-child-bearing, from unrelated to related-by-marriage status. There are also different contexts within a single stage of life: the presentation of self at a major ritual occasion differs from that of daily life. Body adornments are sensitive to these changes, and people change them to signal their social role-of-the-moment. Death is but one social context; researchers do not suppose that the elaborate adornments found in some Upper Palaeolithic burials were worn in everyday life.

If body decoration signalled social identity, it is interesting to note a feature on which Randall White comments. Although the Aurignacians in southern Germany were making portable statuettes and carvings of animals, they did not, generally speaking, make much use of representational art as body adornment. Instead, they used parts of actual animals in a metonymical way, that is, part of the animal stood for the whole. Beads were made from bones and teeth. Moreover, many of the animals whose teeth were used for necklaces and pendants were carnivores – felids and canids. As White says, ‘It is surely more than just a coincidence that animals that hunt other animals were singled out for use in social display by the most dangerous predator of all.’ 58 This function of body decoration may well have had validity in the Aurignacian, but, as we shall see in subsequent chapters, it would be wrong to see hunting as a purely economic, subsistence activity: it was probably also associated with the procurement of supernatural power. I return to the concept of a supernatural realm in a moment.

What, then, could borrowed body adornment have signified in Neanderthal society? It is highly unlikely that the Neanderthals recognized the same range of social distinctions as did Homo sapiens people and that the items of decoration would have signified exactly the same thing in both societies; Neanderthal social structure was surely different from Homo sapiens social structure. If body decoration did signify social distinctions among late Neanderthals, they were not the same distinctions as identical items signified in Homo sapiens communities. That being so, it may be misleading to speak of ‘borrowing’ because the word covertly implies similar functions. If the items meant something different to the Neanderthals – they may have signified no, or very different, social distinctions among the Neanderthals – it was only the ‘outward show’ that was taken over. The Neanderthals were, in some sense, pretending to be Homo sapiens.

By contrast to body decorations, representations – pictures or carvings – of animals and human figures are kinds of art that the Châtelperronian Neanderthals did not take over (Fig. 21). This is a sharper and more informative distinction than researchers have allowed: whatever the Neanderthals may have done that suggests they had some sort of symbolic faculty, there is no evidence that they made pictures and carvings. This distinction suggests that we are now dealing with a radically different kind of art: body-painting, for example, did not evolve into image-making (Chapter 7). Image-making demands mental abilities and conventions of a different, more ‘advanced’, order.

As we have seen, an altogether different kind of art, or perhaps one should say ‘symbolic behaviour’, is the burial of selected dead with grave goods consisting of rich body decorations, beads, pendants, and other artefacts. Although beads and so forth may have been placed in graves, no one can argue that the notion of burial grew out of body decorations. Nor could there have been any evolutionary relationship between graves and pictures – in either direction. They are distinctly different kinds of ‘art’.59 An important point to remember is that some Upper Palaeolithic burials are so rich in grave goods that the items must have been contributed to the burial by a much wider social circle than an individual family. Such burials point to wider social networks and attendant symbolism than those of the Middle Palaeolithic.60

21 What the Châtelperronian Neanderthals borrowed and did not borrow from their Homo sapiens neighbours.

Why, then, did the Neanderthals ignore the images and the elaborate burials of Homo sapiens life? Their selective borrowing raises key questions about society and human consciousness. I argue that elaborate, highly ritualized burial and the making of representational pictures and carvings had, at that time though not necessarily in later periods of human history, two important points in common – even though they are radically different kinds of art.

First, as instances of material culture, body adornment and burial were both associated with the expression and construction of a type of hierarchical, or at least differentiated, society that was not simply based on age, sex and physical strength. For the Neanderthals, this kind of society was – literally – unthinkable. They probably groped to understand why Aurignacians showed respect and deferred to certain people who, as far as the Neanderthals could see, were physically weak. As I have suggested, types of body decoration and ornaments were sporadically absorbed into late Neanderthal culture, but perhaps only to lend a superficial resemblance to their more astute and complex Aurignacian neighbours.

My second point is more fundamental and will lead on to the substance of later chapters. I suggest that the type of consciousness – not merely the degree of intelligence – that Neanderthals possessed was different in important respects from that of Upper Palaeolithic people, and that this distinction precluded, for the Neanderthals, both image-making and elaborate burial. Because of the neurological structure of their brains and the type of consciousness that that structure produced, Neanderthals were unable to

– remember and entertain mental imagery derived from a range of states of consciousness (introverted states, dreaming, altered states, etc.),

– manipulate and share that imagery,

– by such socializing of mental imagery, conceive of an ‘alternative reality’, a ‘parallel state of being’ or ‘spirit world’so memorable and emotionally charged that it had a factuality and life of its own,

– recognize a connection between mental images and two- and three-dimensional images,

– recognize two- and three-dimensional representations of three-dimensional things in the material world, 61 and

– live in accordance with social distinctions that were underwritten by degrees of these abilities and differential access to types of mental imagery.

True, the Neanderthals evidently had mental images of what their tools should look like, though not as precise or flexible as those of Upper Palaeolithic people. They could also understand the purposes that those tools served. But the kind of mental image that enabled them to do all this was, I argue, of an altogether different kind from the type that can be translated into a representation of, say, an animal, and compared with other people’s mental imagery to create an ‘alternative reality’. Neanderthal mental imagery was, I suggest, closely linked to motor skills – such as the series of manual actions that produced a flint tool of the desired shape.Physical action activated mental imagery and, to a limited extent, vice versa.

The more complex Upper Palaeolithic mental imagery could be independently entertained and subtly manipulated. It could also be extended to find expression in, or to be perceived as parallel to, two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional things. Indeed, Aurignacian people could achieve all six of the abilities I have listed. Neanderthals could comprehend neither the Aurignacians’ representational images nor the purposes of their burials. How, they may have asked, can those few marks on a cave wall possibly call to mind a real, live, huge, active bison? (Later, I argue that the Aurignacian images probably represented something even more incomprehensible to the Neanderthal mind.) What could these Aurignacians possibly mean when they talk about the ‘spirit’ of a dead person going to a ‘realm’ where there are other ‘spirits’? Why do Aurignacians place items associated with living, individual people in graves with the bodies of people whose lives have ended?

What are the implications of these points? I suggest that, in Upper Palaeolithic communities, representational art and elaborate burial practices were both associated with different degrees and kinds of access for different categories of people to ‘spiritual’ realms (that is, realms of mental imagery) and, as such, had a common foundation in a type of consciousness that the Neanderthals lacked. That, I argue, is the reason why Neanderthals neither borrowed nor mimicked them. It was not merely that they were insufficiently intelligent (though that may well have been true) but that they had a different kind of consciousness. Fully modern human consciousness, by contrast to that of the Neanderthals, includes the ability to entertain mental images, to generate mental images in various states of consciousness, to recall those mental images, to discuss them with other people within an accepted framework (that is, to socialize them), and to make pictures. How did these abilities and lack of abilities affect the Aurignacians’ and the Neanderthals’ conceptions of their own identities?

From the point of view of the Aurignacians, the ability to form, entertain and manipulate mental imagery in social contexts, to conceive of a spiritual realm and to prepare the dead for that realm were practices that they brought with them when they moved into western Europe, as the early statuettes and burials found in eastern and central Europe imply. They must have realized that the Neanderthals did not have these abilities: they must have seen that, whatever else the Neanderthals may have been able to copy, this was something that they just could not manage. The exploitation of a particular kind of consciousness and mental imagery for social concerns thus became, for the Aurignacians, a major distinguishing feature of their society vis-à-vis their Neanderthal neighbours. That their possession of it would have engendered a sense of superiority over the Neanderthals and coloured their relationships with them are inescapable conclusions that researchers have not explored.

Moreover, it seems likely that the Aurignacians would have gone further and actively cultivated those characteristics of their lives and thought that set them apart from and ‘above’ the Neanderthals. Especially in competitive circumstances towards the end of the Châtelperronian, they would have developed those distinctions that were closely associated with social control within their own communities and with subsistence effectiveness that was dependent on such control. The oldest representational art (the Swabian statuettes) does not appear in the earliest levels of the Aurignacian but somewhat later.62 This delay is understandable. After initial contact, and perhaps a wary stand-off, the two species would have needed time to develop relations of various kinds. Some, but not all, of these relations may have been linked to growing population density and competition for specific resources. It was only when inter-species relations reached a certain level of intimacy that the Aurignacians found it necessary to escalate the making of representational art out of their existing mental imagery; the images that they made were, in part, statements about their social dominance and helped to entrench that dominance. Image-making thus reflected and played an active role in the evolution of social relations right from the beginning.

The Neanderthal point of view must have been entirely different. They had lived in western Europe for 160,000 years or more, and in that time they had successfully honed their relationship with their environment as best they could with their mental capacity. During the period from about 60,000 to 40,000 years ago, they developed regional variations and micro-adaptations: their development had not ground to an absolute halt; their culture was not terminally moribund. Then between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago they had to cope with the new arrivals. They were now participating in a new world of social relations, something with which they had never had to contend before. The new challenges were not environmental, like the ones with which they had previously managed to cope. Now their surroundings contained more complex Homo sapiens social communities and, especially threatening to their way of life, various forms of symbolism that pointed to a more efficient way of life that they could not emulate. These new, challenging components were beyond their ken. They could successfully imitate some components of Aurignacian life, such as stone tool-making; there were aspects, such as body adornment, that they could mimic without being able to take over their full meaning; and then there were kinds of Aurignacian behaviour – elaborate burials, beliefs about a spirit world, and image-making – for which they were not mentally equipped. Their deficiency can be traced not so much to inferior intelligence as to their particular kind of consciousness (Chapter 7).63

I believe that it was a conflictual scenario of social divisions, perceptively prefigured by Max Raphael, that was the dynamic behind the efflorescence of Upper Palaeolithic art. When Laming-Emperaire and Leroi-Gourhan developed the mythogram component of Raphael’s ideas at the expense of his social emphasis, they led Upper Palaeolithic art research down a functionalist avenue, one that emphasizes the ‘beneficial’ effects of image-making by claiming that images facilitated extended inter-group co-operation, intra-group cohesion, information-exchange, the resolution of binary oppositions, and so forth. The reality was, I argue, more complex and much less comfortable. It was not ‘beauty’ or an ‘aesthetic sense’ that was burgeoning at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic but rather social discrimination. Art and ritual may well contribute to social cohesion, but they do so by marking off groups from other groups and thus creating the potential for social tensions. It was not cooperation but social competition and tension that triggered an ever-widening spiral of social, political and technological change that continued long after the last Neanderthal had died, indeed throughout human history.

A wider focus

So far, we have focused on the well-documented region of western Europe and, as a result, have been able to see the Transition as being triggered by the arrival some 45,000 years ago of anatomically modern Aurignacian people who brought with them complex social structures, sophisticated, planned hunting, diverse symbolic behaviour and, of course, image-making. The suddenness with which this new package appears in western Europe and the comparative speed with which it replaced the old Neanderthal way of life are certainly striking. Small wonder then that writers speak of a ‘Creative Explosion’ 64 or, on a grander scale, of the ‘Human Revolution’.65 They are right to do so. But only if they are geographically specific and explicitly ignore evidence from Africa and the Middle East. In these regions we find precursors of the ‘Creative Explosion’, but the overall picture looks much less explosive. It is in Africa that we must seek the earliest evidence for the ‘Human Revolution’.

The more extreme proponents of the ‘Human Revolution’ theory argue that modern human behaviour is a ‘package deal’ and that it appeared everywhere about 50,000–40,000 years ago. They ascribe this apparent sudden change to species-wide neurological changes coupled with the advent of fully modern language.66 This view results from too tight a focus on the west European evidence. Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks, in a critical review of a much wider sweep of evidence that embraces, especially, the African continent, comment:

There is a profound Eurocentric bias in Old World archaeology that is partly a result of research history and partly a product of the richness of the European material itself. The privileging of the European record is so entrenched in the field of archaeology that it is not even perceived by its practitioners.67

To achieve a less biased account of the west European Transition we need to distinguish between what we may see as (a) anatomically modern features of the human body and (b) behaviourally modern features of human life. The first of these two concepts is the easier to define: we need only examine recent human skeletons and agree on which features and measurements are the ones that distinguish them from much older specimens (though this is easier said than done). The second concept is more controversial. Archaeologists have derived their notion of modern human behaviour, that is, behaviour associated with anatomically modern human beings, from the west European evidence. Consequently, they formulate lists to characterize modern human behaviour, such as the following:68

– abstract thinking, the ability to act with reference to abstract concepts not limited in time or space,

– planning depth, the ability to formulate strategies based on past experience and to act upon them in a group context,

– behavioural, economic and technological innovation, and

– symbolic behaviour, the ability to represent objects, people and abstract concepts with arbitrary symbols, vocal or visual, and to reify such symbols in cultural practice.

Given the west European evidence, this list seems reasonable enough. But, as its compilers point out, it is unreasonable to expect all early anatomically modern populations to have expressed these characteristics in exactly the same way. All early Homo sapiens communities did not, for instance, make bone tools, eat fish and use paint to make images in caves.69

The importance of this point becomes clear when we turn to the African evidence for the emergence of modern human anatomy and behaviour. Because our principal interest lies elsewhere, I summarize this evidence and avoid the detail of human fossil types, dates and dating techniques, site names, differences between what is known in Africa as the Middle Stone Age and the European Middle Palaeolithic, stone artefact typologies, demographic patterning within Africa, highly specific internal debates, and much else – fascinating and important though all these issues are.70

Although there is still some residual opposition, as well as a good deal of refining that needs to be done, researchers today generally accept the ‘Out of Africa’ hypothesis. They believe that the fossil evidence shows conclusively that the precursors of anatomically modern human populations evolved in Africa and left the continent in two waves. This hypothesis explains why western Europe was occupied by anatomically archaic Neanderthals for thousands of years before the Homo sapiens communities made their way west from the Middle East and through eastern Europe. One view of this second exodus from Africa is that the anatomically modern populations that left Africa did not have fully modern behaviour and acquired it only some 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

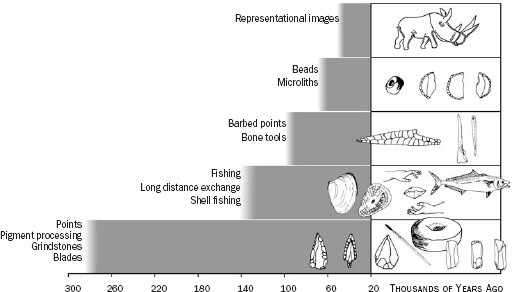

22 The gradual assembly of fully modern behavioural characteristics in Africa. Representational imagemaking is here shown as the most recent component of modern behaviour; recently found geometric engravings have been dated to 77,000 years ago.

The African evidence challenges this crucial point. It now seems that the shift to behavioural modernity started in Africa as long as 250,000 to 300,000 or more years ago.71 It is also clear that we should speak not of ‘modern human behaviour’ but of ‘modern human behaviours’. Modern behaviour did not appear suddenly as a complete package; in this sense, there was no ‘revolution’. The four characteristics of modern behaviour I listed above manifested themselves in various ways and appeared at different times and in widely separated places in the African archaeological record (Fig. 22).72 For instance, the making of blades and pigment processing using grindstones date back to 250,000 years ago. Long-distance exchange and shellfishing started about 140,000 years ago. Bone tools and mining are about 100,000 years old. Ostrich eggshell bead-making started between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago, but present evidence suggests that the species of art that we call representational images may date back to between only 30,000 and 40,000 years ago. Most astonishing of all is the recent find that Chris Henshilwood and his colleagues made in the southern Cape cave known as Blombos. A piece of ochre, carefully engraved with crosses with a central and a containing line has been dated to approximately 77,000 years before the present (Pl. 6). Though not a representational image, this is now the oldest dated ‘art’ in the world. It shows indisputable modern human behaviour at an unexpectedly early date. While there may be some debate about the details of all this evidence, it now seems clear that modern human behaviour was appearing piecemeal in Africa before the Transition in western Europe.73

Change in the behaviour of the earliest African anatomically modern human communities was episodic, and contact between those scattered groups probably intermittent. These two conditions resulted in what McBrearty and Brooks call ‘a stepwise progress, a gradual assembling of the modern human adaptation’.74 It is therefore critical that ‘the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition in Europe not be confused with the origin of Homo sapiens’.75 The African evidence shows that, far from any concept of a revolution, innovations were ad hoc and their dissemination was sporadic. Western Europe was a special case, a cul-de-sac which saw an efflorescence of certain components of modern human behaviour.

There was, therefore, an ‘Upper Palaeolithic Revolution’, a ‘Creative Explosion’, in one sense but not in another. To be sure, there was a comparatively sudden burst of symbolic activity, but that explosion was not universal, nor was it an indivisible ‘package deal’. The idea that all the different kinds of art and fully developed symbolic behaviour suddenly appeared in western Europe may be termed the ‘Creative Illusion’.

This cautionary note does not diminish the importance of what happened in western Europe; it merely places those events in a wider perspective, one that opens up new lines of explanation. If the modern mind and modern behaviour evolved sporadically in Africa, it follows that the potential for all the symbolic activities that we see in Upper Palaeolithic western Europe was in existence before Homo sapiens communities reached France and the Iberian Peninsula. This pre-existing potential means that we should not seek a neuronal event as the triggering mechanism for the west European ‘Creative Explosion’. With what possibilities are we left? It seems to me that the answer must lie in social circumstances. As I have argued, this means we must investigate the role of art in social conflict, stress and discrimination. We should pick up the story where Max Raphael left it. We need to eschew functionalist explanations that, under the silent influence of Darwin’s ideas of natural selection, reiterate in one way or another the supposedly beneficial effects of imagemaking, the ways in which image-making is said to have contributed to a harmonious society. Instead of following this (I suggest facile) route we need to explore the role of images and the complex social processes of imagemaking in circumstances of social conflict. Far from lying at the root of a ‘pure, higher aesthetic sense’, image-making, linked to religion, was, much more murkily, born in and facilitated the formation of stratified societies as we know them today.76

Having come to a better understanding of the specific role of western Europe in the larger scheme of things, we can now focus in a more informed way on the enigma of Upper Palaeolithic art. The first issue that we need to address is the distinction between human intelligence and consciousness and the ways in which this distinction helps to clarify what was happening to the Upper Palaeolithic human mind in the caves of western Europe. Why did people penetrate into those dark passages and chambers and fashion images that even today make us hold our breath as they overwhelm us in the interplay of light and darkness?