CHAPTER 8

The Cave in the Mind

In one of the most evocative passages in Plato’s The Republic, Socrates invites Glaucon, a devoted pupil, to envisage ‘an underground cave-dwelling, with a long entrance reaching up towards the light’.1 In this cave are fettered prisoners who have been in this condition since infancy and who can see only the shadows of statues and other objects that men are carrying across the entrance. These shadows fall on the wall before their fixed gaze. With no knowledge of the world beyond their cave, the prisoners, as Glaucon readily concedes, believe that they are looking at reality. If one of their number – emblematic of the philosopher – were to manage to escape and reach the light behind the source of the shadows, and then return to tell the prisoners that they are seeing mere shadows, they would not believe him.

If, Socrates continues, the benighted prisoners had a ‘system of honours and commendations’ and awarded prizes to the man who had the keenest eye for the passing shadows and the best memory of them, they would not wish to abandon their awards merely on the word of the one who had been up to the light. Nor would he wish to return to sharing their esteem for those who had been recipients of awards.

There is much in this rather disturbing trope that is relevant to our enquiry into Upper Palaeolithic parietal images. From our perspective, there is, however, a key point that Socrates does not make. In our version of the cave, the light streaming from above catches the prisoners themselves and throws the ‘shadows’ of their minds onto the wall so that they mingle with the shadows of the external objects to create a multi-dimensional panorama.

We are concerned not only with the human mind in the cave; we must also take into account the neurological cave in the mind. We are considering some of the ways in which the human mind behaved in the Upper Palaeolithic caverns, whether as a result of the sensory deprivation of the caves themselves or the many other factors that induce altered states of consciousness. Amongst those states is, as we have seen, the sensation of entering a constricting vortex and coming out on the far side into an hallucinatory realm with its own conditions of causality and transformation. This is the cave in the mind. Then, too, there is the projection of mental imagery onto surfaces. In the absence of anyone who had the kind of understanding of altered states that we have today, Upper Palaeolithic people must have believed, like Socrates’s prisoners, that those images and experiences were part and parcel of ‘reality’, as they conceived it. This chapter explores the ways in which the cave in the mind and the topographies of geomorphological caves interlocked.

To accomplish this task, I intertwine more tightly the various strands of evidence that we have been following, and, at the same time, continue my consideration of shamanism. I began with a suspicion, an intelligent guess that writers have mooted from time to time; I now move on to confirmation of that suspicion and, in the next chapter, to an exploration of specific Upper Palaeolithic caves with well-supported hypotheses in mind. At that point, I shall consider how Upper Palaeolithic people may have awarded ‘honours and commendations’ to those who were skilled in discerning, remembering and ‘fixing’ the ‘shadows’ on the walls. We shall be able to see how the caves were used and, at least in general terms, why they were embellished as they were. Our evidential strands will intertwine to form a strong cable.

Hypothesis

All in all, the preceding chapters have shown that there are two major reasons for suspecting some form of shamanism in the west European Upper Palaeolithic:

There is every reason to believe that the brains of Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens were fully modern. They therefore experienced dreams and had the potential to experience visions. Further, they had no option but to reach some common understanding of what dreams and visions were and what they meant. By contrast, combined neurological and archaeological evidence suggests that Neanderthals, like other mammals, had the neurological potential to experience dreams and hallucinations, but not to remember them in any significant way, to act upon them, or to use them as a basis for social discrimination.

Secondly, we have noted the ubiquity among hunter-gatherer communities of what we call shamanism. Not being concerned with societies that combine elements of shamanism with other religions, I listed what I take to be the principal features of hunter-gatherer shamanism (Chapter 4). Whatever differences exist between them, and they are doubtless numerous, huntergatherer societies throughout the world have ritual functionaries who exploit altered states of consciousness to perform the tasks that I noted in our general discussions and in the two case studies.2 I argue that the widespread occurrence of shamanism results not merely from diffusion from a geographical source area, such as central Asia – though the first people to enter North America doubtless took tenets of shamanism with them. Rather, we should note the ancient, universal, human neurological inheritance that includes the capacity of the nervous system to enter altered states and the need to make sense of the resultant dreams and hallucinations within a foraging way of life. There seems to be no other explanation for the remarkable similarities between shamanistic traditions worldwide.

Taken together these two points – antiquity and ubiquity – make it seem likely that some form of shamanism was practised by the hunter-gatherers of the west European Upper Palaeolithic. That ancient expression of shamanism would in all probability not have been identical to any of the historically recorded types of shamanism, but it would have had comparable core features – hence the value of both ethnographic case studies and neuropsychology. Nor does it seem likely that Upper Palaeolithic shamanism was static and unchanging through the 30,000 and more years of the Upper Palaeolithic and across the whole of western Europe. But, as the analogy that I drew with Christianity implies (Chapter 4), change does not mean total overthrow, and Upper Palaeolithic shamanisms were probably subsumable under the general rubric of ‘shamanism’.

Our suspicion seems well-founded enough to be called a hypothesis. As we intertwine evidential strands, we can move on to consider other kinds of support for that hypothesis and to see what puzzling features of Upper Palaeolithic art it explains.

Animals and ‘signs’

One of the most baffling features of Upper Palaeolithic art is the co-occurrence of geometric motifs with images of animals: sometimes they are adjacent, sometimes superimposed. Some panels, such as the Apse in Lascaux3 or the Sanctuary in Les Trois Frères,4 are so densely covered with both representational and geometric images that some relationship between the two types seems inescapable. What could that relationship be?

We have seen that representational imagery could not have evolved out of geometric or ‘macaroni’ marks: the non-representational marks are not feeble early attempts at image-making.What, then, about the suggestion that the two types of image derive from two distinct, parallel, probably complementary, graphic systems?5 Some researchers think that the relationship between geometric and representational images may have been akin to that between text and diagrams in a book: each says the same thing but by means of different conventions.

The answer is in fact more straightforward. As we have seen, in certain altered states, the human nervous system produces both geometric and representational imagery. The two kinds of imagery are not exclusively sequential, each obliterating its predecessor; in Stage 3, they are experienced together. Their intimate association in shamanistic art throughout the world therefore comes as no surprise. Indeed, we can go a step further. The behaviour of the human nervous system in altered states resolves the postulated dichotomy between geometric and representational imagery that has formed the foundation for all classifications of Upper Palaeolithic art hitherto devised. Contrary to these classifications, both types of image are representational: they both represent (by way of complex processes) mental imagery, not (at least initially) things in the material world.

That is not the end of the matter. When the neuropsychological model (Chapter 4) is applied to Upper Palaeolithic imagery we find all stages represented. This model was an initial attempt to get a better hold on Upper Palaeolithic art, one that went beyond general assertions and unsupported ethnographic analogies. It has, however, become much misunderstood: there is more to the model than entoptic phenomena. It is incorrect to refer to the hypothesis as the ‘entoptic explanation’ or the ‘entoptic theory’, as numerous writers do. Indeed, clear depictions of entoptic phenomena are rare in Upper Palaeolithic cave art, as indeed they are in southern African shamanistic rock paintings (as opposed to engravings where they are more numerous). Both Upper Palaeolithic people and San rock painters were more concerned with Stage 3 hallucinations than with Stage 1 entoptic phenomena. What is significant is that there are Upper Palaeolithic images referable to all three stages of the model, and this strengthens the argument for a connection with the mental imagery of altered states. We find entoptic forms (Stage 1), construals (Stage 2), and transformations and combinations of representational and entoptic imagery (Stage 3).6 The proportions of imagery ascribable to each of the stages varied from time to time and place to place.

But we also find Upper Palaeolithic ‘signs’ that do not conform to any of the known entoptic types. Figure 47 shows some of these non-entoptic motifs. Amongst them are ‘claviforms’, vertical lines with a bulge on one side, and ‘tectiforms’, hut-like motifs. This distinction is a major step forward because it helps us to address the non-entoptic ‘signs’ and how these relate to animal motifs from a different point of view from that which we adopt when we examine the entoptic elements. Because meaning is not inherent in but rather assigned to entoptic imagery (and indeed to all imagery) in specific cultural contexts, we do not know what the ‘signs’ of Upper Palaeolithic art meant to the people of the time. The Cro-Magnons of western Europe were not South American Tukano, so we cannot transfer the meanings that Reichel-Dolmatoff discovered those Amazonian people ascribed to their geometric mental images to the Upper Palaeolithic paintings and engravings.

47 Not all Upper Palaeolithic signs conform to the shapes of entoptic phenomena as established by laboratory research. These include socalled claviforms and hut-shaped tectiforms.

Whether we shall ever be able to crack the meanings of the entoptic and non-entoptic signs remains to be seen; I am not irredeemably pessimistic on this point. At present we can at least say that some of them are similar to entoptic forms. Those motifs are, as far as their origin rather than their meaning is concerned, explicable in terms of altered states of consciousness. They therefore fit the overall pattern suggested by the hypothesis that Upper Palaeolithic parietal art was shamanistic.

Caverns measureless to man

Another highly puzzling characteristic of Upper Palaeolithic imagery is also clarified by our hypothesis, and, moreover, clarified in such a way as to lead us on to further, more detailed, questions and answers. The heuristic potential of the hypothesis is thus revealed: it does not ring the curtain down on research, but encouragingly leads on to further questions.

The characteristic to which I now refer is the placing of images in deep, often small, underground contexts to which no light penetrates and which people seem to have seldom visited. These locations are connected to larger chambers, also in total darkness, in which a number of people could have gathered to view the images and to perform other activities. Then there are the images in the open air and in the entrances to caves; these are well-lit. The way in which the images trail from the level of daily life into underground caverns and then on into spaces that in some cases can be reached only by negotiating hazardous, labyrinthine subterranean passages suggests that parietal art was a cultural product that linked the tiers of the Upper Palaeolithic cosmos. In Lévi-Straussian terms, one could say that Upper Palaeolithic parietal art mediates, or forms a connecting link between, the two elements of an ‘above-ground:below-ground’ binary opposition.

This inference means that to speak of Upper Palaeolithic shamanism is to make a statement about cosmology, not just about religious belief and ritual, as if such matters were epiphenomena and therefore of no great importance to our understanding of Upper Palaeolithic life. All life, economic, social and religious, takes place within and interacts reciprocally with a specific conception of the universe. It cannot be otherwise. As we saw in previous chapters, the shamanistic cosmology is conceived, in the first instance, as comprising two realms, the material world and a spiritual realm. Often, the spirit world is immanent, interdigitating with the material world as well as separate from it. At the same time, these two realms are conceived of as subdivided and layered, the more socially complex the shamanistic society, the more tiered the subdivisions of the cosmos. There is not one, monolithic ‘shamanistic cosmos’. We also saw that universal, neurologically ‘wired’ sensations of flying and passing through a constricting tunnel probably gave rise to these conceptions.

I now argue that entry into Upper Palaeolithic caves was probably seen as virtually indistinguishable from entry into the mental vortex that leads to the experiences and hallucinations of deep trance. The subterranean passages and chambers were the ‘entrails’ of the nether world; entry into them was both physical and psychic entry into the underworld. ‘Spiritual’ experiences were thus given topographic materiality. Entry into a cave was, for Upper Palaeolithic people, entry into part of the spirit world. The embellishing images blazed (possibly in a fairly literal sense) a path into the unknown.

We can go a step further. Altered states of consciousness not only create notions of a tiered cosmos; they also afford access to, and thereby repeatedly validate, the various divisions of that cosmos. The tiered shamanistic cosmos and ‘proof’ of its reality constitute a closed system of experiential creation and verification. Even people who, for whatever reasons, did not have access to the far end of the intensified trajectory or to the caves themselves, were still able to verify the structure of their cosmos through the more evanescent glimpses of another realm that their dreams afforded them. That they could fleetingly and imperfectly glimpse the creatures and transformations of the spirit world was, for them, evidence enough that the shamans could actually visit it and return with detailed accounts of it. Such people were like Socrates’s prisoners who were able to talk to each other but who merely confirmed each other’s view of the passing shadows.

The Upper Palaeolithic subterranean passages and chambers were therefore places that afforded close contact with, even penetration of, a spiritual, nether tier of the cosmos. The images that people made there related to that chthonic (subterranean) realm. Images were not so much taken underground – pictures of the world above lodged in people’s memories – and placed there; they were both obtained and fixed there.The hallucinatory, or spirit, world together with its painted and engraved imagery, was thus invested with materiality and precisely situated cosmologically; it was not something that existed merely in people’s thoughts and minds. The spiritual nether world was there, tangible and material – and some people could empirically verify it by entering the caves and seeing for themselves the ‘fixed’ visions of the spirit-animals that empowered the shamans of the community and also by experiencing visions, perhaps even in those underground spaces.

Moreover, image-making did not merely take place in the spirit world: it also shaped and incrementally created that world. Every image made hidden presences visible. There was thus a fecund interaction between the given topography of the caves, mercurial mental imagery, and image-fixing by individuals and groups; through time, the images built up and modified the spiritual world both materially (in the caves) and conceptually (in people’s minds). The spirit world, like the social world above, was to some degree malleable; people could engage with it and to a certain extent shape it. In most cases, this shaping took the form of adding new images to those already there or starting to create a new panel altogether. But, in some rare cases, there seem to have been attempts at removing images already there. In the Cosquer Cave, for instance, hand-prints were deeply scored across, as if to cancel them, and in Chauvet it seems that images may have been removed by scraping the surface.7

A living support

This understanding of the caves as the entrails of the nether world brings me to another feature of Upper Palaeolithic parietal art that is difficult to explain outside of the shamanistic hypothesis. As we have seen, one of the best-known and most consistent features of Upper Palaeolithic art is the use that image-makers made of features of the rock surfaces on which they placed their images. Almost every cave contains instances, and numerous writers have commented on the puzzle that they present.8 Here are a few examples over and above those to which I have already referred; they lead, cumulatively, to an important conclusion about the seemingly ‘dead’ cave walls.

Upper Palaeolithic images are sometimes placed so that a small, apparently insignificant nodule or protuberance forms the eye of an animal. Some of the nodules are so insignificant that one suspects that they were identified and selected by touch rather than by sight. In the dim light of flickering lamps, fingers lightly exploring the walls discovered a nodule, and the mind, prepared for the discovery of animals, took it to be an eye. In some cases, touch may have aided the recall, or reconstitution, of a visionary animal. Having experienced a vision in deep trance or as an afterimage, a vision seeker in a more alert state carefully felt the wall for indications of where the spirit animal was.

On a larger scale, a natural rock at Comarque seems to have suggested a remarkably realistic horse’s head, complete with nostrils and mouth (Fig. 48).9 An engraver merely completed and added details to the form. Then, too, human figures occasionally also make use of natural features of the rock. At Le Portel, for example, two red outline human figures are painted so that stalagmitic protuberances become their penes (Pl. 15).10

A particularly illuminating and well-known example is at Castillo (Cantabria) where a depiction of a bison has been painted to fit the rough surface of a stalagmite: the artist discerned the back, tail and hind leg in the shape of the rock (Fig. 49). Significantly, this meant that he or she would have to depict the animal in a vertical position.11 But this does not seem to have mattered. On the contrary, the resultant image exemplifies one of the differences between mental imagery and the animals of the material world outside the cave that, in the nature of things, normally walk or stand in a horizontal position. The Castillo artist was not trying to depict an animal as anyone may see it outside the cave; rather, he or she was reconstituting a ‘floating’ vision. As we saw in Chapter 7, Upper Palaeolithic images seem to ‘float’ on the rock; when they are anchored by some feature of the surface, they are not necessarily in a realistic posture.

48 Partly natural and partly sculpted, this rock form represents a horse’s head. (Comarque, Dordogne.)

49 A few lines were added to the natural form of a stalagmite in Castillo, Spain, to produce an image of a vertical bison.

50 This hole in the rock wall of the Salon Noir, Niaux, resembles a deer head seen faceon. Upper Palaeolithic people added antlers to the natural shape to enhance the appearance of a deer’s head looking out of the wall.

So far, I have described depictions that present lateral views of animals. By contrast, in the Salon Noir at Niaux an artist added antlers to a hole in the rock that, viewed from a certain angle, resembles a deer head, as seen from the front (Figure 50).12 At Altamira, Upper Palaeolithic people created a similar effect in the Horse’s Tail, the deepest part of the cave: natural shapes in the rock have been transformed by the addition of painted eyes and, in one case, a black patch that may represent a beard.13 Visitors who reach the end of this narrow passage and then turn to leave the cave are confronted by faces apparently peering from the rock walls (Pls 4, 5). A similar effect was created in Gargas, in the foothills of the Pyrenees.14 Perhaps even more remarkable is a horse’s head painted in Rouffignac (Fig. 51). Here the head has been depicted on a flint nodule that juts out from the wall; the rest of the animal’s body seems to be ‘inside’ the wall.

51 A horse’s head painted on a flint nodule projecting from the wall of Rouffignac, Dordogne, gives the impression of the animal being inside the rock.

The effect created by these and many other images is of human and animal faces looking out of the rock wall. The figures are not merely painted onto the surface; they become part of the cave itself, part of the nether realm. In this way, human intervention changed the significance of the topography. What could that significance be?

We saw in the North American case study that shamans go on a vision quest, usually in a remote isolated place, sometimes a high cliff-top, sometimes a cave, to fast, meditate and induce an altered state of consciousness in which they ‘see’ the animal helper that will impart the power requisite for shamanistic practice.15 The evidence that I have assembled in this and previous chapters, especially that pertaining to small, hidden niches in the Upper Palaeolithic caves, suggests that one of the uses of the caves was for some sort of vision questing.16 Certainly, the sensory deprivation afforded by the remote, silent and totally dark chambers, such as the Diverticule of the Felines in Lascaux and the Horse’s Tail in Altamira, induces altered states of consciousness.17 In their various stages of altered states, questers sought, by sight and touch, in the folds and cracks of the rock face, visions of powerful animals. It is as if the rock were a living membrane between those who ventured in and one of the lowest levels of the tiered cosmos; behind the membrane lay a realm inhabited by spirit animals and spirits themselves, and the passages and chambers of the caves penetrated deep into that realm.

This suggestion recalls the experience of Barbara Myerhoff, an anthropologist who worked among the Huichol people of northern Mexico. After having ingested the hallucinogenic plant peyote, she ‘sat concentrating on a mythical little animal…. The little fellow and I had entered a yarn painting and he sat precisely in the middle of the composition. I watched him fade and finally disappear into a hole.’ So-called yarn paintings are made by sticking coloured yarn onto an adhesive surface; they frequently depict hallucinatory experiences and mythical concepts. Entering depicted imagery in this manner was probably also part of Upper Palaeolithic and southern African shamanistic experience.18

A tangible ‘other world’

This explanation extends to another enigmatic feature of the embellished caves: the various ways in which the walls of numerous caverns were touched.

In some sites, such as Cosquer Cave, near Marseilles, the entrance to which was inundated by the rising sea-level at the end of the Ice Age, so-called fingerflutings cover most of the walls and parts of the ceiling, even beyond head height (Pl. 14). People trailed two, three or four fingers through the mud on the cave walls wherever the surface was malleable. Above the now-submerged entrance passage that leads to Cosquer, the finger marks are several yards up and their making must have required rudimentary ladders.19 Indeed, at Cosquer the only parts of the cave not covered with finger-flutings are those without the soft mud film that is made by the weathering of the limestone.20 The cross-sections of some of these flutings, 2–3 mm deep, suggest that they might not have been made with fingers but with some sort of instrument, perhaps the tip of a flint blade with nicks that left striations, though such marks may have been left by fragments of stone carried along by the fingers or by broken fingernails.

The patterns so created are rectilinear, curving or zigzagged; some were gone over twice, so we can be sure that they were not entirely random – the shapes mattered. For us, they recall some of the entoptic elements, but there is more to it. In Cosquer, the finger-flutings form a background to the images, which are, in every case, executed on top of them. In one instance, however, a group of two red handprints are also overlain by finger-flutings. The handprints and the flutings in Cosquer therefore seem to constitute a temporal group of markings.

This sort of treatment of cave walls was more widespread in the west European Upper Palaeolithic than is usually allowed; perhaps researchers find finger-flutings rather boring compared with images of animals and therefore tend to ignore them. A detailed and valuable study was, however, undertaken by Michel Lorblanchet, a French archaeologist who has studied the rock art of the Lot Département of France. In the Pech Merle Cave, he found as many as 120 sq.m (1,290 sq. ft) of finger markings: ‘Almost all the clay walls that are accessible without too much difficulty bear these markings.’21 Most marks seem to have been made by adults, though two bands of lines were clearly executed by two small hands, either of a woman or an adolescent. The second of these possibilities may be supported by a dozen or so footprints of an adolescent or big child on the floor of Pech Merle.22

Lorblanchet found that representational images were integrated into a number of the apparently random finger-flutings, though he rightly rejected any suggestion that simple finger marks evolved into depictions.23 Still, his interest centred on recognizable images rather than the ‘macaronis’ themselves. As a result, he saw the practice of finger-fluting as associated with creation mythology, ‘bringing forth creatures from the void and the inextricable’. But finger-flutings appear without representational images often enough to suggest that they had their own significance.

This conclusion is borne out at Hornos de la Pena, in Spain. Here the flutings are more restricted in distribution than in Cosquer or Pech Merle: in one place, a finger-traced ‘grid’ surrounds and appears to issue from a natural cavity (Pl. 16).24 In another remarkable treatment of cave walls at Hornos de la Pena, cavities in the walls were filled with mud and then punctured, apparently with fingers or sticks.25

In Cosquer, the treatment of the surfaces was taken further than finger-flutings. In some locations, sizeable areas were scraped with a tool of some sort as if people wanted to collect the soft, sticky clay; no attempts were made to scrape hard surfaces.26 There is next to no sign in the cave of the quantities of clay that must have been removed from the walls; unless it was deposited in the now-flooded areas, it was therefore carried out of the cave. Red clay was also scraped out of fissures and seemingly removed from the cave. Although one cannot be absolutely certain because of the flooding, it seems that the clay was valued for some purpose, whether for body decoration, the manufacture of paint, or decoration of skin clothing we cannot tell.

On the question of the meaning of finger-flutings, Peter Ucko, Director of the Institute of Archaeology, London, remarks, ‘it is…inconceivable to us today to understand the nature of such action’.27 Jean Clottes and Jean Courtin also remain puzzled by finger-fluting. They ask: ‘What could their purpose be, except to mark the presence of people in the depths of the earth – to take possession of these places, as mysterious as they are frightening, where for all we know no one before them had dared to venture?’ 28 I defer answering this crucial question until after considering what I believe to be a related form of human activity in the caves.

Hands-on experience

Indeed, the evidence of finger-fluting places us in an advantageous position to consider in a new way one of the most talked-about features of Upper Palaeolithic art – handprints. In some respects, researchers have studied handprints in the same way that they have considered finger-fluting and ‘macaronis’: even as they looked for recognizable images amongst the flutings, they have been interested in the image of the hand rather than the act of making it. Chapters 5 and 6 showed that there is reason to believe that an image itself and the act of making it are simply parts of a longer chain of operations entailing social action and beliefs.

As we saw in Chapter 1, handprints are of two kinds: positive and negative. Positive prints were made by placing paint on the palm and fingers and then pressing the hand against the rock wall. Negative prints were made by placing the hand against the rock and then blowing paint over the hand and the surrounding rock; when the hand was removed, an image of a hand remained.

A fascinating variation on handprints has been found in the Chauvet Cave. Here, there are two panels of what, from a distance, appeared to be large red dots. Eventually, when researchers were able to move closer to the rock wall without disturbing the Upper Palaeolithic surface beneath their feet, they found that the dots are in fact palm-prints. Paint was placed in the hollow of the palm and then slapped against the rock; here and there one can see a trickle of paint falling from the print and the fainter imprints of fingers. On the left side of each print there is a slight notch left by the gap between the thumb and the first finger; they are all right-hand prints. So far, the technique is unique to Chauvet.29

If we take into account what we have already noted about the shamanistic tiered cosmos and the rock wall as a membrane between people and the subterranean spirit world, we must consider the act of making the prints as important as (possibly more than) the resulting shape of a hand. To be sure, the handprint may well have signified the presence of a particular person, as is often suggested – an ancient ‘Joe was here’ – but the fact that a whole panel in Chauvet seems to have been made by a single person diminishes this possibility, at least for that instance. Further, if a handprint indicates the presence of a particular person, we need to ask about the circumstances in which it was made. People had to carry paint into the depths of the caves: handprints were not made on the spur of the moment. Why would people want to have their handprints in the deep caves?

Again, it seems that the answer to this question has more to do with touching the rock surface than with image-making. In the case of negative prints, the paint was applied in such a way that it completely covered the entire hand, and sometimes part of the forearm as well, together with the surrounding rock (Fig. 52). The hand thus ‘disappeared’ behind a layer of paint; it was ‘sealed into’ the wall. In the case of positive prints, the paint was a mediating film that connected the hand to the rock. We have seen that paint should not be regarded as a purely technical substance (Chapter 5); it probably had its own significance and potency. Perhaps it was a kind of power-impregnated ‘solvent’ that ‘dissolved’ the rock and facilitated intimate contact with the realm behind it.

52 A negative hand print. Paint was blown over the hand and wrist thus ‘sealing’ it in the rock wall.

The importance of Upper Palaeolithic paint as a significant substance is borne out by the Chauvet palm-prints. In one panel there are 48 prints; in the other there are 92. The size and anatomical characteristics of the prints suggest that each panel was made by one person, possibly a youth or a woman, but the two panels were not painted by the same person. The panel of 48 dots seems to have been initiated by a clear, full handprint to the left; the palm-prints were added, but care was taken to ensure that they did not overlap the original handprint. The panel of 92 prints has no full handprint; the ‘ghosts’ of fingers, when visible, appear to be fortuitous. Paint was evidently not added to the palm for each print because some have a thinner film of paint in the centre of the palm. But the trickle of paint falling from some prints seems to me to suggest that the action was designed, at least in part, to place a fair quantity of red paint on the rock, so much that it occasionally trickled down the rock face.

In other caves, such as Enlène, there are small dots and strokes of paint in the Galerie du Fond – no images, just the red marks (Fig. 1). As their placing in this deep, out-of-the-way location shows, the marks could not have been made by accident. Here the mere presence of even a small quantity of paint on the rock seems to have been important. The placing of paint, a highly charged substance, on the ‘membrane’ was a significant act.

The act of blowing paint onto the rock also requires careful consideration, lest we imagine that it was no more than a technical operation. Lorblanchet, who had considerable anthropological experience in Australia, investigated the blown handprints and images in the Pech Merle cave in the light of what he had learned about Aboriginal painting techniques. As part of his work in France, he undertook to try to replicate the complex ‘spotted horses’ panel in Pech Merle, which includes six negative handprints (Pl. 19). He found that the handprints were added around the two horses after they had been completed. There can be little doubt that the handprints here are integrally related to the representational horse images; together, they constitute a meaningful ‘composition’.

He also found that parts of the horses themselves were made by blowing paint onto the rock. To replicate the process of blowing he used charcoal:

I put the charcoal powder in my mouth, chewed it, and diluted it with saliva and water. The mixture of charcoal and saliva extended with water forms a paint that adheres well to a cave wall…. To reproduce [the handprints], I used both my hands, but I found it easier to use my left hand with its back against the wall to make what appear to be prints of my right hand.30

A poison-control centre in Paris warned Lorblanchet not to experiment with manganese dioxide, one of the pigments that Upper Palaeolithic artists used, because he would ‘risk serious health problems’ if he accidentally swallowed it.

Standing in front of the Upper Palaeolithic ‘spotted horses’, and contemplating them for a long time, I noticed a point of interest. I found that my hands comfortably and simultaneously fitted the two black prints over the back of the right-hand horse (I did, of course, take care not to allow my hands to touch the rock). I also found that the rock between these two prints bulged out slightly so that it came close to my mouth. At this point, the rock is stained with a red haze of paint that may have come from the mouth of a person standing exactly where I was and with both hands placed on the rock. As I stood there, my body was close to the image of the horse; I was almost embracing the horse, and my face was inches away from the ‘membrane’.

Although Lorblanchet believes that each handprint in this panel was made separately and that the uniform size of the prints suggests that they were made by only one person, I do not believe his conclusions are inescapable. The lowest handprint, for instance, must have been made by the right hand of someone lying prone on the rock floor of the cave; the print is so low that the person’s wrist and forearm must have been in contact with the floor. From this position, it would have been difficult, though perhaps not impossible, for the prostrate person to blow the paint onto his or her own hand. It seems probable that the blowing of the paint need not have been done by the person who was holding his or her hand(s) against the rock but by another, perhaps one could say ‘officiating’, person. It is also possible that more than one person took part in the paint-blowing; a small group of people may have taken turns in the paint-blowing process. This kind of co-operative mode of making at least some of the prints seems to be confirmed by an instance in Gargas, where the hand and forearm of a child were held against the rock by an adult, whose grip on the child’s arm can be seen; it was not the child who was blowing the paint.

As a result of his experience of making a replica of the ‘spotted horses’ panel, Lorblanchet concluded:

The method of spit-painting seems to have had in itself exceptional symbolic significance to early people. Human breath, the most profound expression of a human being, literally breathes life onto a cave wall. The painter projected his being onto the rock, transforming himself into the horses. There could be no closer or more direct communication between a work and its creator.31

We can now return to the questions posed by finger-fluting. If we allow that Upper Palaeolithic people believed that the spirit world lay behind the thin, membranous walls of the underground chambers and passages, the evidence for finger-fluting, handprints and much otherwise incomprehensible behaviour can be understood in rational, if not absolutely precise, terms. In a variety of ways, people touched, respected, painted and ritually treated the walls of caves because of what they were and what existed behind their surfaces. The walls were not a meaningless support. They were part of a highly charged context, a context that, I now argue, provides the earliest evidence that we have for one of the archetypal religious metaphors.

Darkness and light

Sometimes an undulation in the rock surface becomes the dorsal line of an animal if one’s light is held in a specific position; an artist simply added legs and some other features to the shadow. There is a particularly fine example at Niaux where an undulation in the rock has been used to suggest a bison’s back (Pls 17, 18). The distinctively humped dorsal line is clear when a light source is held to the left of and slightly below the image. Like the bison at Castillo (Fig. 49), this Niaux animal is positioned vertically in order to exploit the natural feature of the rock. Similarly, the head of the right-hand ‘spotted horse’ at Pech Merle is suggested by a natural feature of the rock, especially when the source of light is in a certain position – also to the left of the image. In this case, the artist distorted the painted horse’s head, making it grotesquely attenuated; the rock shape itself is more realistically proportioned than the painted head within it. It is as though the rock suggested ‘horse’, yet the artist painted not a naturalistic horse but a deliberately, though only partially, distorted horse, perhaps a ‘spirit-horse’, recognizable as to species but clearly not ‘real’. This technique of using shadows to complete a depiction is more common than is usually supposed:32 people used the insubstantial interplay of moving shadows to seek power and create images of that power.

In these instances, the sought-after animal was not simply ‘discovered’ in the convolutions of the rock. It was created by human intervention and an interaction between two elements, light and darkness. Leaving the world of light and entering the dark, subterranean realm, the image-maker, or makers, carried a lamp or torch. This flickering flame was something that questers had to master and which, the evidence suggests, they used for further revelations.

An important reciprocality is implied by these images born of light and shadow. On the one hand, the creator of the image holds it in his or her power: a movement of the light source can cause the image to appear out of the murk; another movement causes it to disappear. The creator controls the image. On the other hand, the image holds its creator in its power: if the creator or subsequent viewer wishes the image to remain visible, he or she is obliged to maintain a posture that keeps the light source in a specific position. If the viewer tires and as a result lowers the light, the image seems to retreat into the realm behind the membrane. Perhaps more than any other Upper Palaeolithic images, these ‘creatures’ (creations) of light and darkness point to a complex interaction between person and spirit, artist and image, viewer and image. There was a great deal more to Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings than pictures simply to be looked at: some of the images sprang from a fundamental metaphor.

This conclusion is supported by some of the lamps found in the caves. The controlled use of fire dates back more than half a million years, but the use of fire in lamps started at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic; lamps were an invention of Homo sapiens. Most of the known examples come from France; lamps from Spain, Germany and farther east are rare. Sophie de Beaune and Randall White, archaeologists who undertook a detailed study of Upper Palaeolithic lamps, concluded that lamp-producing communities were restricted to a particular region.33 This, as we have seen, is also the region of prolific cave art.

Most lamps were simply rough pieces of stone with natural hollows that could contain the tallow; wicks were made of lichen, moss, conifers and juniper. They did not produce a very bright light. De Beaune and White estimate that as many as 150 lamps would be required to provide accurate colour perception of images along a 5-m (16-ft) long panel; each lamp would have to be placed about 50 cm (20 in) from the wall. So many lamps in one place seems unlikely. Lamps were therefore probably usually supplemented by torches made from Silvester pine. But in caves where only lamps were used viewers would have experienced the paintings and engravings very differently from the way we do today with harsh electric lamps that penetrate every recess.With small tallow lamps, only limited portions of a wall could be seen at any one time, and, as de Beaune and White put it, ‘The illusion of animals suddenly materializing out of the darkness is a powerful one.’34

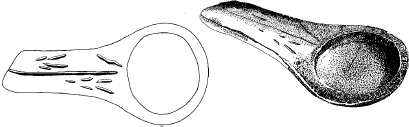

Some lamps were clearly ‘special’. One of these was discovered in La Mouthe (Dordogne), where, early on, excavations demonstrated the antiquity of Upper Palaeolithic cave art (Fig. 8). It is a beautifully shaped, shallow stone bowl. On the underside, there is an engraving of an ibex head with large curving horns. Though not as common as depictions of horses, bison and reindeer, ibexes were engraved on the walls of La Mouthe in close association with other species.

Another example, this one from Lascaux, is also fashioned from sandstone, but it has a ‘handle’ (Fig. 52). It is engraved with a central line that runs the length of the handle. Towards one end of the line there are, on one side, four separate marks and, on the other side and towards the other end of the line, a set of similar incisions. Such signs occur on the walls in all parts of Lascaux, along with depictions of animals. Most of these are painted, though one in the remote Diverticule of the Felines is engraved. This lamp was found at the bottom of the ‘Well’, an area of the cave I discuss in the next chapter.

The imagery on both these lamps thus relates to the parietal art of the caves in which they were found. At first glance, one may suppose that the imagery on the lamps is there merely for decoration. But what I have so far noted about the shamanistic cosmos, the relations between some images and light, and the significance of entering the entrails of the underworld are all points that suggest there was more to light and lamps than simple utility. Both the animals and the geometric motifs were, in some way, related to the light:darkness metaphor.

It is, of course, quite possible that the genesis of the binary light:darkness metaphor took place before people ventured into the caves. Day and night might well have been a much earlier generating circumstance, each having its own connotations. Once created, the metaphor was probably extended to embrace and inform beliefs about the caves and the nether world. Indeed, it seems probable that, during the Upper Palaeolithic, the great binary metaphor became a vehicle for multiple meanings that might have included notions of life and death, good and bad, though in formulations probably different from those that have run through the Western tradition down to the present day.

53 Carved sandstone lamp found in the Shaft in Lascaux. A ‘broken’sign is carved on the handle.

Numerous writers have discussed the metaphors by which we live, the ones that give meaning and orientation to our lives, that structure the ways in which we react to the world around us and to other people.35 Light and darkness constitute one of those metaphors. But, unlike many others of more recent origin, light:darkness can be traced back to the Upper Palaeolithic.

An echo from the opposite wall

Light and darkness and the other characteristics of Upper Palaeolithic art that I have considered have focused on the visual. But, in altered states of consciousness, all the senses hallucinate. It is this complexity that gives visions and hallucinations such overwhelming impact.

Socrates made this point when he developed his notion of bound prisoners in a cave. He suggested that, if those carrying the objects across the entrance to the cave were to speak and there was ‘an echo from the opposite wall’, those in the cave would believe ‘that the voice came from the shadow passing before them’.

In shamanistic belief, images and visions are not silent: they speak, make animal sounds and communicate. For instance, a Greenlandic Inuit shaman seeking spirit helpers went to an entrance into a glacier. After calling on the spirits, he heard a voice telling him to enter the ‘under-ice’ world. There, in the darkness, he encountered a growling bear.36

Sound also plays a prominent role in the Banisteriopsis-induced trances of the Peruvian rain forest Cashinahua:

I heard armadillo tail trumpets and then many frogs and toads singing. The world was transformed. Everything became bright…. I came down the trail to a village. There was much noise, the sound of people laughing. They were dancing kacha, the fertility dance.37

Here, the shaman’s trance experience includes sounds of various kinds. It is common to find that shamans hear not only the sounds of musical instruments, spirit people and spirit animals, but those animals also speak to them, give them instructions and teach them songs. Some of these sounds derive from neurologically induced aural sensations which shamans interpret in culturally specific ways; others, those that include comprehensible statements, are more properly hallucinations.38 To these ‘inner sounds’ must be added those made by people to accompany rituals and mental experiences.39 There is evidence that Upper Palaeolithic people had the means to make ‘music’. More than two dozen so-called ‘flutes’ have been reported, but it is not always clear if the holes in these hollow bones were made to facilitate the sounding of different pitches or if they are simply the result of the bone having been bitten by animals. But some are convincing, and it appears that people used hollow bones to make sounds.40 Whether the sounds so produced could be called music or whether they were imitations of animal sounds we do not know.

Another type of sound was evidently made by ‘bull-roarers’, flat pieces of bone, antler or wood that were attached to a cord and swung round and round to produce a powerful humming sound. A particularly fine example, covered with geometric decorations and rubbed with red ochre, was found at La Roche de Birol in the Dordogne.41 Such instruments were also used by the southern African San to imitate the sound of bees swarming; bees were, for them, a significant source of supernatural potency. We do not know what Upper Palaeolithic people believed about the sounds emitted by bull-roarers, but, if they were used in subterranean chambers, the effect must have been aweinspiring.

To my mind, the oft-cited ‘musical bow player’ in the Sanctuary at Les Trois Frères is somewhat less convincing (Figs 1, 44). This bison-headed figure seems, at first glance and in numerous illustrations, to be holding a bow to his face. Closer inspection of the whole panel reveals so many apparently random lines amongst the tangle of figures that the bow-playing interpretation becomes tenuous. Finally, we need to notice that a number of caves contain evidence for stalactites, especially of the undulating ‘drapery’ kind, having been struck, though we cannot always be sure that this was done during the Upper Palaeolithic. These stalactites emit a deep booming sound when struck. In the Réseau Clastres (Fig. 2) in the foothills of the French Pyrenees, they have been struck by someone standing on the far side; someone entering the cave with only a lamp or burning torch would not easily see the percussionist, and the sound would swell and resonate from the darkness in enveloping waves.

The effect of rhythmic sound, especially drumming and chanting, is widely recognized as a means of contacting the world of spirits.42 The literature on this point is indeed vast. One has only to think of the sounds of clapping and dancing rattles fixed around the ankles that cause potency to ‘boil’ in San shamans and to carry them off to the spirit world.Elsewhere, shamans are intimately associated with drums. Amongst Siberian shamans, the tiered cosmos is represented on drums along with creatures that inhabit the various levels.43 On one drum the horizontal levels were crossed by a perpendicular line ‘which the shaman called kiri (bowstring) and which was supposed to serve him as orientation when he was going on unknown roads or flying on his drum to the spirits.’44 This ‘bowstring’ is what anthropologists call the axis mundi.

Amongst the Siberian Tuvas, a clan ritual was performed to ‘enliven’ a shaman’s drum: in this ceremony, the process was regarded as ‘taming and training the horse’,45 thus emphasizing the point that the drum was the shaman’s ‘vehicle’ to the spirit world. In northern Siberia, the shaman’s drum may represent a reindeer, the hide of which is used in the making of the drum. The shaman was said to ride the reindeer-drum to the spirit world; drums were ‘animals in their own right as well as makers of sounds’.46

The drum is also called a boat. As Anna-Leena Siikala of Joensuu University, Finland, a long-time student of Siberian shamanism, explains:

Calling a drum a boat is also more than an expression of figurative language. Mythical images or metaphoric expressions are often understood as a real manifestation of the signified. The drum-boat, for example, can be visualised and sensed as a real object in visions and shaman songs.47

The American anthropologist Michael Harner sums up the effect of persistent drumming: ‘The steady, monotonous beat of the drum acts like a carrier wave, first to help the shaman enter the SSC [Shamanic State of Consciousness], and then sustain him on his journey.’48 This is not a flight of fancy. Like so much else of what I have discussed, there is a material, neurological, not merely psychological, basis for widespread shamanistic beliefs. Research has shown that low-frequency drum-beats produce changes in the human nervous system and induce trance states, which, of course, include sensations of out-of-body travel.49 There is thus a neurological explanation for the shamanistic use of drums.

Working on the altogether reasonable hypothesis that some sort of musical or rhythmic activity probably took place in Upper Palaeolithic caves, researchers have investigated the acoustic properties of various chambers and passages.50 Findings suggest that resonant areas are more likely to have images than non-resonant ones. The implication is that people performed rituals involving drumming and chanting in the acoustically best areas and then followed up these activities by making images. An extension to this suggestion is that depictions of felines are placed (for unexplained reasons) in non-resonant chambers. All in all, the hypothesis is interesting but, I feel, ultimately unpersuasive. For instance, a comparison of the highly decorated Axial Gallery with the much less elaborate Diverticule of the Felines in Lascaux is misleading. They are not both ‘narrow dead-end tunnels’.51 The Axial Gallery is much larger than the Diverticule of the Felines, which can accommodate only one person and then in a prone position. Then, too, the recent discovery of feline images in a deep but large chamber in Chauvet will require investigation. The factors that governed the placing of images were far more complex than resonance alone, and included the way in which the topography of a cave was conceived and the locations where specific kinds of spiritual experiences were encouraged. Still, we need not doubt that resonance and echoes added to the effect of subterranean Upper Palaeolithic rituals. The caves, if not the hills, were alive with the sound of music.

What are the effects of music on someone in an altered state? Westerners, having ingested LSD, expressed the experience like this:

I lay quietly and listened to the music…then my vision commenced to change a little…and slowly the music seemed to absorb all my consciousness…. It seemed to me as though the music and I became one. You do not hear it – you are the music. It seems to play in you…. As the music started, I suddenly felt a great lifting from within. Then outer space became alive. The music carried me and flowed through me…I felt much larger than normal and more elongated in my limbs.52

Barbara Myerhoff had a comparable experience after she ingested peyote. She became intensely and blissfully conscious of passing vehicles. ‘With great delight I began to notice sounds, especially the noises of the trucks passing on the highway outside…. My body assumed the rhythm of the passing trucks, gently wafting up and down like a scarf in a breeze.’53

If that is the effect of music and rhythmic sound on Westerners, what would it have been on Upper Palaeolithic people? Would animal sounds, for instance, have led to a feeling of oneness with the animals? Did sound aid transformation into an animal? ‘You are the music.’ It is, of course, difficult to answer such questions, but, given the universality of the human nervous system, it seems likely that these Western reports throw some light on what it must have been like to enter an Upper Palaeolithic cave, to experience altered states and to hear music and emotive sounds.

The cumulative effect

Socrates’s simile of a cave inhabited by prisoners bound so that they can see only shadows is a more dramatic presentation of the insights that he offered in the previous section of The Republic. Immediately preceding his development of the cave simile, Socrates asked Glaucon to think of a line divided into four sections that represent states of mind: at the top end is intelligence, next is reason (understanding), next is belief (faith) and at the lower end of the line is illusion (imagining).54 This conceit is uncannily like the spectrum of consciousness that I have outlined. Upper Palaeolithic people moved along Socrates’s line as do twenty-first-century people, though it would be good to think that we do not occupy the lower, illusory, end of the line as extensively as they did. The mind in the cave and the cave in the human mind cannot be separated; they are keys to subterranean Upper Palaeolithic parietal art.

The combined effect of the underground spaces, altered states of consciousness, mysterious sounds, the interplay of light and darkness, and progressively revealed, flickering panels of images is, in one sense, easy to imagine, but, in another sense, the impact of such multi-sensory experiences on Upper Palaeolithic people probably exceeded anything that we can comprehend today. We enter the caves with our minds at the top end of Socrates’s line; their minds were working with faith and illusion. Nor can we fully reconstruct the rituals that must surely have been performed in the cold, silent and dimly lit chambers and passages. Nor can we say what each and every image and geometric sign meant to the people who saw them or were told about them.

Yet, if we see the caves as entities, as natural phenomena taken over by people, and try to place them in a social context, as Max Raphael urged, we can begin to sense something of the role that they must have played in Upper Palaeolithic communities. Rather than attempt to generalize the exceedingly diverse caves into a rigid, imposed ‘structure’, as André Leroi-Gourhan did, we need to take them individually and try to discern the various ways in which each was used by a community of people – not just by individuals for the making of individual images. It is to this essentially sociological task that I turn in the next chapter.