Vincent van Gogh (seen from behind) and Emile Bernard on the banks of the Seine at Asnières, c. 1886

Van Gogh made the short trip to Antwerp on 24 November 1885. The bustling, historic harbour city appealed to him immediately. His hunger for art and new ideas, stirred by his visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam the previous month, drove him to visit every place in the city where the work of old and contemporary artists could be seen: the museums, the churches with their religious paintings by great masters, the viewing days at auction houses, and even an art lottery. He commented, more frequently than before, on the use of colour and technique in the paintings he saw. He looked at Rubens differently now, judging not so much his subject matter and convincing rendering of emotions as his effective use of colour. Van Gogh was now looking at things through the eyes of a painter. The small number of painted portraits that survive from this period – executed in looser brushwork and brighter colours than his Nuenen work – show how eager he was to put his new insights into practice.

Van Gogh made contact with some art dealers, but realized that the few paintings that had been shipped with his belongings were unlikely to sell. His chances of success were minimal, he now understood, unless he started producing town views and portraits. It was not easy to find affordable models, however. Occasionally he tried to persuade a prostitute or other folk type to pose for him, but the cost of painters’ materials and hiring models were ‘ruining’ him (547).

In January 1886 Van Gogh showed some of his recent work to the teachers at the art academy and was admitted for a course of study. There he could paint from models and, in the evening, draw from plaster casts of antique statues. At life-drawing classes which met late in the evening, his acquaintance with other students allowed him to sharpen his mind somewhat, but did not give him much satisfaction. In his eyes, most of them had been completely misled by their teachers, who wrongly focused on technique and disapproved of personal expression. At the same time, he was disappointed at the lack of fellowship and verve in the world of artists and art dealers. He actually found the dull artistic climate quite depressing. It strengthened his conviction that solidarity and collaboration were necessary to bring about a ‘renewal’ (549).

Vincent van Gogh (seen from behind) and Emile Bernard on the banks of the Seine at Asnières, c. 1886

In the meantime Vincent’s health had deteriorated to an alarming degree. Acting on a doctor’s advice, he finally took some rest. He was treated for venereal disease and also needed a lot of dental work, all of which cost a great deal of money. Theo, who often opposed Vincent’s uncontrolled spending on materials and models, immediately sent extra money whenever he thought his brother’s health was at stake.

At the end of January Van Gogh finished his courses at the academy and took stock of the situation: ‘my ideas have changed and been refreshed, and that was actually the goal I had in mind in coming here’ (562). No progress had been made, though, with regard to the ‘friction of ideas’ (555) that he had sought among his peers and the hoped-for sale of his work.

In February Vincent pressed Theo to let him come to Paris – not in June or July, when Theo’s lease was due to expire and he would be free to look for a more spacious apartment for the two of them, but immediately. Vincent wanted to spend a year honing his skills as a draughtsman. To this end, he had his eye on Fernand Cormon’s studio – popular with foreign artists, and known to be less rigid than more traditional studios – and he wanted to paint copies in the Louvre and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Theo tried to persuade him to return to Nuenen until the summer, but Vincent, leaving behind not just his possessions but also his debts, set out in late February for the capital of France, the capital of the artistic world.

Vincent arrived in Paris without prior warning at the end of February 1886. It had been ten years since his last visit to the metropolis. Everything that was progressive in art, literature, theatre and music came together there. It was in Paris that Van Gogh first heard the music of Wagner and saw experimental plays at the cafés and cabarets of Montmartre. Modern novels by such writers as Guy de Maupassant, Joris-Karl Huysmans and Leo Tolstoy sharpened his view of a society that was changing rapidly in the face of industrialization.

Shortly after his arrival Van Gogh enrolled at Cormon’s studio on the boulevard de Clichy, where students could work after the model. But Vincent wrote to Horace Mann Livens, an English acquaintance from the art academy in Antwerp, that he ‘did not find that as useful as I had expected it to be’ (569); he gave up working there by June.

Theo’s apartment in rue Laval, where he unexpectedly had to make room for Vincent, was exchanged in June for a more spacious apartment in rue Lepic in Montmartre, a district that had preserved its small-scale, rural character. Vincent had a small room to use as a studio, but his chaotic lifestyle and way of working left their mark throughout the house. Theo had a prestigious job that brought with it certain social obligations; Vincent’s nonconformist behaviour caused him a great deal of embarrassment.

The fact that the brothers were living together meant fewer letters were exchanged. Our knowledge of their time together in Paris comes from eyewitness accounts and from references and descriptions in Vincent’s later letters. Artists with whom Vincent came into contact in this period reported that he was easily upset, aired his opinions whether they were called for or not, and always seemed to be looking for an argument. Feelings often ran high between the brothers, and Theo sometimes suggested that it would be better for them to live apart. But despite the difficulties, their fraternal bond always prevailed.

During his first summer in Paris, Van Gogh painted many flower still lifes to increase his understanding of colour theory and to practise modelling with paint. His brushwork became looser and his colours brighter under the influence of Impressionism, which was ubiquitous in Paris. He became friendly with the intelligent and ambitious Emile Bernard, who was just eighteen years old, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who was at the beginning of his brief but highly successful career. Van Gogh also became acquainted with Paul Gauguin, who held great promise for the future, and he got to know the Pointillists Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. Moreover, he became very enthusiastic about Japanese prints which he admired for their clarity and elegance, and of which he bought large quantities. In 1887 Van Gogh organized an exhibition of Japanese prints from his collection at the café run by Agostina Segatori, briefly his lover, and another show at a restaurant later that year of paintings by himself and several of his friends.

Emile Bernard and his sister Madeleine, c. 1887

In Paris Van Gogh came to the conclusion that being a ‘modern artist’ meant total immersion in the artistic, social and intellectual life of one’s time. He expanded his repertoire by painting cafés, parks, flower still lifes and self-portraits. It is astonishing to see how quickly Van Gogh, coming from the north with his gaze still fixed on the past, managed to reinvent himself in Paris in little more than a year, becoming an artist who had shed all dogma. The modern Van Gogh was born in Paris, a fact of which he was well aware when he left the city two years later.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 545)

Saturday evening

My dear Theo,

Wanted to write to you with a few more impressions of Antwerp. This morning I went for a really good walk in the pouring rain, an expedition with the object of fetching my things from the customs office. The different entrepôts and hangars on the wharves are very fine.

I’ve already walked in all directions around these docks and wharves several times. It’s a strange contrast, particularly when one comes from the sand and the heath and the tranquillity of a country village and hasn’t been in anything but quiet surroundings for a long time. It’s an incomprehensible confusion.

One of De Goncourt’s sayings was ‘Japonaiserie for ever’. Well, these docks are one huge Japonaiserie, fantastic, singular, strange — at least, one can see them like that.

I’d like to walk with you there to find out whether we look at things the same way.

One could do anything there, townscapes — figures of the most diverse character — the ships as the central subject with water and sky in delicate grey — but above all — Japonaiseries.

I mean, the figures there are always in motion, one sees them in the most peculiar settings, everything fantastic, and interesting contrasts keep appearing of their own accord.

A white horse in the mud, in a corner where heaps of merchandise lie covered with a tarpaulin — against the old, black, smoke-stained walls of the warehouse. Quite simple — but a Black and White effect.

Through the window of a very elegant English inn one will look out on the filthiest mud and on a ship where such delightful wares as hides and buffalo horns are being unloaded by monstrous docker types or foreign sailors; by the window, looking at this or at something else, stands a very fair, very delicate English girl. The interior with figure wholly in tone, and for light — the silvery sky above that mud and the buffalo horns, again a series of contrasts that’s quite strong. There’ll be Flemish sailors with exaggeratedly ruddy faces, with broad shoulders, powerful and robust, and Antwerp through and through, standing eating mussels and drinking beer, and making a great deal of noise and commotion about it. Contrast — there goes a tiny little figure in black, with her small hands pressed against her body, slipping soundlessly along the grey walls. In a frame of jet-black hair, a little oval face, brown? Orange yellow? I don’t know.

She raises her eyelids momentarily and looks with a slanting glance out of a pair of jet-black eyes. It’s a Chinese girl, mysterious, quiet as a mouse, small, like a bedbug by nature. What a contrast to the group of Flemish mussel eaters.

Another contrast — people passing along a very narrow street between formidably tall houses. Warehouses and stores. But down at street level, alehouses for all nations with the corresponding male and female individuals. Shops selling food, sailors’ clothes, colourful and bustling.

This street is long, one keeps seeing authentic scenes, and once in a while there’s a commotion, louder than usual, when a quarrel breaks out. For instance, you’re walking along, looking around, and suddenly a great cheer goes up and all sorts of shouting. In broad daylight a sailor is being thrown out of a brothel by the girls and pursued by a furious fellow and a string of girls. Of whom he is apparently terrified — at any rate, I saw him scramble over a pile of sacks and disappear through a window into a warehouse. Once one’s had enough of this racket — at the end of the berths where the Harwich and Le Havre boats lie — having the city behind one — one sees — in front of one, nothing, absolutely nothing but an infinity of flat, half-flooded pasture, incredibly sad and wet, undulating dry reeds, mud — the river with a single small black boat, water in the foreground grey, sky misty and cold, grey — silent as a desert.

The overall effect of the port or of a dock — sometimes it’s more tangled and fantastic than a thorn-hedge, so tangled that one can find no rest for the eye, so that one gets dizzy, is forced by the flickering of colours and lines to look now here and now there, unable to tell one thing from another even after staring at a single spot for a long while.

But if one goes to a place where one has an indistinct piece of land as a foreground — then one gets the most beautiful, quiet lines and those effects that Mols, for instance, often gets. Now one sees a girl who is magnificently healthy and, at least seemingly, very sincere and innocently cheerful, then a countenance so slyly malicious that one is frightened by it as if by a hyena. Not forgetting the faces ravaged by the pox, the colour of boiled shrimp, with little dull grey eyes and no eyebrows, and sparse, greasy, thin hair, colour of pure pig’s bristle or slightly yellower — Swedish or Danish types. It would be good to work there — but how and where? Because one could run into trouble there exceedingly quickly. All the same, I did roam around a whole lot of streets and alleys without mishap, even sat and talked very genially with various girls, who evidently took me for a bargee.

I don’t consider it impossible that I might be able to come by some good models by painting portraits.

Today I got my things and tools — which I was eagerly awaiting. And so I have my studio in order. If I could come by good models at virtually no expense I wouldn’t be afraid of anything. I don’t reckon it a bad thing, either, that I haven’t any money, as much as it would take to force things by paying.

Perhaps the idea of painting portraits and getting the sitters to pay for them by posing is a safer way. Because in the city it’s not like it is with the peasants. Anyway. One thing’s certain, Antwerp’s a very singular and beautiful place for a painter.

My studio’s quite tolerable, mainly because I’ve pinned a set of Japanese prints on the walls that I find very diverting. You know, those little female figures in gardens or on the shore, horsemen, flowers, gnarled thorn branches.

I’ve reconciled myself to having left — and hope not to be idle this winter.

Well, it’s a relief to me to have a little cubby-hole where I can work in bad weather.

It’s pretty obvious that I shan’t exactly be living in the lap of luxury these days.

See that you send your letter off on the first, because I’ve got enough bread in until then, but after that I’d be in a real stew.

My little room isn’t bad at all, and it definitely doesn’t look dreary.

Now that I have the 3 studies I brought with me here, I’ll set about going to the picture dealers, who mostly seem to live in private houses, though, no shop windows on the street.

The park is beautiful, too. I sat there drawing one morning.

Well — I’ve had no setbacks so far. I’m safe and sound as far as accommodation is concerned, for by forking out a few more francs I’ve acquired a stove and a lamp. I shan’t easily get bored, I assure you. I’ve also found OCTOBER by Lhermitte, women in a potato field in the evening, magnificent. Not yet November, though. Have you kept up to date with that, by any chance? I’ve also seen that there’s a Figaro Illustré with a fine drawing by Raffaëlli.

You know my address is 194 rue des Images, so please address your letter there, and the second volume of De Goncourt when you’ve finished it.

Regards.

Yours truly,

Vincent

It’s curious that my painted studies look darker here in the city than in the country — is this because the light isn’t as bright anywhere in the city? I don’t know — but it might differ more than one would say on the face of it. It struck me, and I could understand that things that are with you also appear darker than I thought they were in the country. Still, the ones I’ve brought with me now don’t look bad all the same — the mill — avenue of autumn trees and still life, and a few small ones.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 552)

My dear Theo,

Last Sunday I saw the two large paintings by Rubens for the first time, and because I’d looked at the ones in the museum repeatedly and at my leisure, these — The descent from the Cross and The elevation of the Cross — were all the more interesting for it. There’s an oddity in The elevation of the Cross that struck me right away, and that is — there are no female figures in it. Unless on the side panels of the triptych. It’s no better for it in consequence. Let me tell you that I adore The descent from the Cross. NOT, though, because of the depth of emotion that one would find in a Rembrandt or in a painting by Delacroix or in a drawing by Millet.

Nothing moves me less than Rubens when it comes to the expression of human sorrow. Let me start by saying, to make it clearer what I mean — that even his most beautiful heads of a weeping Magdalen or Mater Dolorosas always just remind me of the tears of a pretty tart who’s caught the clap, say, or some such petty vexation of human life — as such they’re masterly, but one needn’t look for anything more in them. Rubens excels in the painting of ordinary beautiful women. But he is not dramatic in the expression. Compare him with, say, the head by Rembrandt in the La Caze Collection — with the male figure in the Jewish bride — you’ll understand what I mean — that, for instance, his 8 or so bombastic fellows performing a feat of strength with a heavy wooden cross in The elevation of the Cross seem absurd to me as soon as I look at them from the standpoint of modern analysis of human passions and emotions. That in his expressions, particularly in the men (always excepting actual portraits) Rubens is superficial, hollow, bombastic, yes, altogether conventional and nothing, like — Giulio Romano and even worse fellows of the decadence.

But all the same, I adore it because it is precisely he, Rubens, who seeks to express a mood of gaiety, of serenity, of sorrow, and actually achieves it, through the combination of colours — even if his figures are sometimes hollow etc.

Thus in The elevation of the Cross, even — the pale spot — the body a high, light accent — is dramatic in the context of its contrast with the rest, which has been pitched so low.

The same thing, but to my mind far more beautiful, is the charm of The descent from the Cross, where the pale spot is repeated by the blonde hair, pale faces and necks of the female figures, while the sombre setting is immensely rich because of those various low masses, brought together by the tone, of red, dark green, black, grey, violet.

And Delacroix tried again to get people to believe in the symphonies of the colours. And in vain, one would say, judging by how much almost everyone understands good colour to mean the correctness of local colour, the small-minded preciseness — that neither Rembrandt, nor Millet, nor Delacroix, nor whomever you like, not even Manet or Courbet, set as their aim, any more than Rubens or Veronese did.

I’ve also seen various other Rubens paintings &c. in several churches. And it’s very interesting to study Rubens, precisely because he is, or rather seems, so supremely simple in his technique. Does it with so little, and paints — and above all draws, too — with such a swift hand and without any hesitation. But portraits and — heads or figures of women, that’s his forte. There he’s deep and intimate, too. And how fresh his paintings have remained precisely because of the simplicity of the technique.

Now what else shall I tell you? That I feel increasingly inclined, without rushing, that’s to say without rushing nervously — to do all my figure studies over again from the beginning very calmly and coolly. I’d like to get to the point in knowledge of the nude and the structure of the figure where I can work from memory. I’d like to work either with Verlat or at another studio for a while, and for the rest also paint from models for myself as much as possible. At the moment I’ve left 5 paintings — 2 portraits, 2 landscapes, 1 still life — with Verlat’s painting class at the academy. I’ve just been there again, but each time I haven’t found him there. But I’ll soon be able to let you know how that turns out. And I hope to arrange it so that I can paint from the model at the academy all day, which would make it easier for me, since the models are so awfully expensive that I can’t keep it up.

And I must find some way of getting help in that regard.

In any event, I think that I’ll stay in Antwerp itself for a while, instead of going back to the country. It would be so much better than postponing it, and there’s so much more opportunity here of finding people who might take an interest in it. I feel that I dare do something and can do something, and things have already been dragging on for far too long.

You get cross if I make a comment, or rather you take no notice of it, and all the rest that we know, and yet I believe that there will come a time when you yourself will have to acknowledge that you’ve been too weak in seeing to it that I get back some of my credit with people. But anyway, we’re facing the future, not the past. And again — I believe that time will bring you to the realization that, if there had been more cordiality and warmth between us, we could have set up our own business together.

Even if you’d stayed with G&C. You said to me, indeed, that you know very well that you’ll get no thanks for your pains — but are you so very sure that this isn’t a misunderstanding like the one Pa himself laboured under? At any rate I won’t put up with it, you can be sure of that. For there’s still too much to do, even nowadays.

The other day I saw an excerpt from Zola’s new book for the first time, ‘L’oeuvre’, which as you know is appearing as a serial in Gil Blas. I think that this novel will do some good if it sinks in a little in the art world. I thought the excerpt that I read was very realistic.

For my part I’ll admit that something else is needed when working absolutely from nature — facility of composition — knowledge of the figure — but after all — I don’t think I’ve been putting myself to all this trouble for years for absolutely nothing. I feel a certain power in me because, wherever I may go, I’ll always have a goal — painting people as I see and know them.

As to whether we’ve already heard the last of Impressionism — to stick to the term Impressionism — I always imagine that many newcomers may still emerge in figure painting, in particular, and I’m beginning to think it increasingly desirable in a difficult time like the present that one should seek one’s salvation precisely by going deeper into high art. For there is relatively higher and lower — people are more than the rest, and for that matter a whole lot harder to paint, too.

I’ll do my best to make acquaintances here, and I thought that if I worked for a while with Verlat, say, I’d be in a better position to know what’s going on here, and what there is to do, and how one can get into it.

So just let me scratch around, and for heaven’s sake don’t lose heart or weaken. I don’t think that you can reasonably ask me to go back to the country for the sake of perhaps 50 francs a month less, when the whole stretch of years ahead is so closely related to the associations I have to establish in town, either here in Antwerp or later in Paris.

And I wish I could make you understand how easy it is to foresee that a great deal will change in the trade. And consequently there are many new opportunities too, if one could come up with something original. But that that is therefore necessary, if one wants to do something useful. It’s no fault of mine and no crime when I tell you we must put more force into this or that, and if we don’t have it ourselves we’ll have to find friends and new contacts. I have to earn a bit more or have a few more friends — preferably both. That’s the way to get there, but it’s been too tough for me recently.

As regards this month, I really do definitely have to insist that you manage to send me at least another 50 francs.

At the moment I’m losing weight, and moreover my clothes are getting too bad &c. You know very well yourself that this won’t do. All the same, I have a degree of confidence that we can pull through.

But you said that if I became ill we’d be in even more of a state — I hope it won’t come to that, but I would like to be a little bit more comfortable, precisely so as to prevent that.

Anyway — when one thinks how many people just go on living without ever in their lives having even a notion of care — and who always just think that everything will turn out for the best. As if people didn’t starve — and no one ever perished.

I’m beginning to object more and more to your imagining yourself to be a financier and, for instance, thinking the exact opposite of me.

People aren’t all alike, and if one isn’t able to see that in calculating, above all, TIME must have passed over the calculation before one can consider for certain that one has calculated correctly; if one can’t see this, one is no calculator. And a broader view of finance is precisely what characterizes many modern financiers. That’s to say not exploiting, but allowing freedom of action. I know, Theo, how you yourself could perhaps be rather hard pressed. But you’ve never in your life had it as hard as I have for the last 10 or 12 years in a row. Can’t you understand that I’m right when I say that now, perhaps, it’s been long enough; in that time I’ve learned something I couldn’t do before, so all the opportunities have been renewed and I come up against it, against always being neglected? And if it were now to be my wish to stay here again in city life for a while, then perhaps also go to a studio in Paris, will you try to prevent it? Be fair enough to let me go on, because I tell you, I’m not looking for a row and I don’t want a row, but I won’t allow my career to be blocked. And what can I do in the country, unless I go there with money for models and paint? There’s no opportunity in the country, absolutely none, to make money from my work, and that opportunity does exist in town. So I won’t be secure until I’ve made friends in the city, and that’s the order of the day. Now for the moment it might make things a bit more difficult but it’s the way, all the same, and going back to the country now would end in stagnation.

Anyway — regards — De Goncourt’s book is good.

Yours truly,

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh (letter 559)

My dear Theo,

I’ve received your letter and 25 francs enclosed and I thank you very much for both. I’m really glad that you like my plan to come to Paris. I believe it will help me make progress and at the same time that, if I didn’t go, I might easily get into a mess, keep moving around in the same circle too much, persist in the same mistakes. Furthermore, as for you, I don’t think that coming home to a studio would do you any harm. For the rest, I have to tell you the same about me as you write about yourself — I’ll disappoint you.

And even so, this is the way to combine forces. And even so, much greater understanding of each other can follow from it.

Now what shall I tell you about my health? I still believe that I have a chance of avoiding being really ill; all the same, I’ll need time to get better. I also still have two more teeth to be filled, then my upper jaw, which was most affected, will be all right again. I still have to pay 10 francs for that, and then another 40 francs to get the bottom half right too.

Some years of those 10 years that I appear to have spent in prison will disappear as a result. Because bad teeth, which one so seldom sees any more as it’s so easy to get them put right, since bad teeth give a physiognomy a sort of sunken look.

And then — even eating the same things, one can naturally digest better when one can chew properly, and so my stomach will have a chance to recover.

I really do notice that I’ve been at a very low ebb, though — and as you wrote yourself, all sorts of things that are even worse could arise out of neglecting it. However, we’ll see that we get it put right.

I haven’t worked for a few days, gone to bed early a couple of nights (otherwise it was usually 1 or 2 o’clock because of drawing at the club). And I feel that it’s calming me.

I’ve had a note from Ma, who writes that they’re going to start packing in March.

Further, since you say you’ll have to pay rent until the end of June — well then, perhaps it would be best after all if I were to return to Nuenen, starting in March, only — if I encountered opposition and scenes like I got before I left, I would be wasting my time there and so, even if it were only just for those few months, I’d make a change anyhow, since I want to have some new things from the country ready to bring to Paris with me.

That Siberdt, the teacher of the antique, who spoke to me at first as I told you, definitely tried to pick a quarrel with me today, perhaps with a view to getting rid of me. Which didn’t work inasmuch as I said — Why are you trying to pick a quarrel with me? I have no wish to quarrel, and in any case I have absolutely no desire to contradict you, but you deliberately try to pick a quarrel with me.

He evidently hadn’t expected that and couldn’t say much to refute it this time, but — next time, of course, he’ll be able to start something.

The issue behind it is that the fellows in the class are talking about things in my work among themselves, and I’ve said, not to Siberdt but outside the class to some of the fellows, that their drawings were completely wrong.

Bear in mind that if I go to Cormon and run into trouble sooner or later either with the master or the pupils, I wouldn’t let it worry me. If need be, even if I didn’t have a master, I could also go through the antique course by going to draw in the Louvre or somewhere. And so I’d do that if I had to — although I’d far rather have correction — as long as it doesn’t become DELIBERATE provocation; that correction without one giving any cause other than a certain singularity in one’s manner of working which is different from the others. If he starts on me again, I’ll say out loud in the class, I’m happy to do mechanically everything that you tell me to do, because I’m determined to pay you back what is your due, if need be, if you insist on it, but — as far as mechanizing me as you mechanize the others is concerned, that has not, I assure you, the slightest hold over me.

Besides, you started by telling me something quite different, that’s to say, you told me: tackle it as you wish.

The reason why I’m drawing plaster casts — not to start from the outline, but to start from the centres — I haven’t got it yet, but I feel it more and more and — I’ll certainly carry on with it, it’s too interesting.

I wish that we could spend a few days together in the Louvre and could just talk about it. I believe it would interest you.

This morning I sent you Chérie, mainly for the preface, which will certainly strike you.

And — I wish that at the end of our lives we could also walk somewhere together and — looking back, say — we’ve done this — and that’s one; and that — and that’s two; and that — and that’s three. And if we want to and dare to — will there be anything to talk about then?

We can try two things — making something good ourselves — collecting things by other people that we think are good, and dealing in them. But we must both live rather more robustly, and perhaps combining forces is a step towards becoming more robust.

But now allow me to touch on a delicate matter — if I’ve said unpleasant things to you, specifically about our upbringing and our home, this has been because we’re in an area where being critical is essential in order for us to get along with and understand each other and cooperate in business.

Now I can well understand that one can passionately love something or someone that one can’t do anything about.

Very well — I won’t go into that except in so far as it might make a fatal separation between us where reconciliation is needed.

And our upbringing &c. — won’t prove to be so good that we’ll retain many illusions about it — there you are — and we might perhaps have been happier with a different upbringing. But if we stick to the positive idea of wanting to produce and to be something, then we’ll be able, without getting angry, to discuss faits accomplis as such when it’s unavoidable and might perhaps touch on or directly concern the Goupils or the family. And for the rest, these issues between us are for the understanding of the situation and not out of rancour.

But if we undertake something it won’t be a matter of indifference to either of us to improve our health, because we need time alive — some 25 or 30 years of working constantly. There’s so much of interest in the present age when one thinks how very possible it is that we may well yet see the beginning of the end of a society. And just as there is infinite poetry in the autumn or in a sunset, and then there’s so much soul and mysterious endeavour in nature, so it is now. And as for art — decline, if you will, after the Delacroix, Corots, Millets, Duprés, Troyons, Bretons, Rousseaux, Daubignys — very well — but a decline so full of charm — that there truly is still an immense, immense amount of good things to come, and they’re being made every day.

I’m longing dreadfully for the Louvre, Luxembourg etc., where everything will be so new to me.

For the rest of my life I’ll regret that I didn’t see the Cent chefs d’oeuvre, the Delacroix exhibition and the Meissonier exhibition. But there will still be plenty of opportunities to catch up. It’s true, for instance, that wanting to progress too quickly here, I may actually have progressed less, but what would you? My health is also behind it, and if I regain that as I hope to do, then my taking pains will have been less in vain.

After all, I believe that if one asks permission, one may draw plaster casts in the Louvre, even if one isn’t at L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

It wouldn’t surprise me if, once the idea of living together takes hold, you’ll find it odder and odder that we’ve been together so surprisingly little, if you will — for fully 10 years.

Anyway, I most certainly hope that this will be the end of it, and that it won’t begin again.

What you say about the apartment is perhaps really rather expensive. I mean, I’d be just as happy if it weren’t quite as good.

I’m curious as to how those few months in Nuenen will be for me. Since I have some furniture there, since it’s beautiful there, too, and I know the district a little, it might be a good thing for me to keep a pied-à-terre there, if need be in an inn where I could leave that furniture, since otherwise it will be lost — and it could still come in very useful.

There’s sometimes the most to do by returning to old places.

I must finish this now, since I’m going to the club.

Keep thinking about what we can best do. Regards.

Yours truly,

Vincent.

To Horace Mann Livens (letter 569)

My dear Mr Livens,

Since I am here in Paris I have very often thought of your self and work. You will remember that I liked your colour, your ideas on art and litterature and I add, most of all, your personality.

I have already before now thought that I ought to let you know what I was doing, where I was.

But what refrained me was that I find living in Paris is much dearer than in Antwerp and not knowing what your circumstances are I dare not say Come over to Paris, without warning you that it costs one dearer than Antwerp and that if poor, one has to suffer many things. As you may imagine. But on the other hand there is more chance of selling.

There is also a good chance of exchanging pictures with other artists.

In one word, with much energy, with a sincere personal feeling of colour in nature I would say an artist can get on here notwithstanding the many obstructions. And I intend remaining here still longer.

There is much to be seen here – for instance Delacroix to name only one master.

In Antwerp I did not even know what the Impressionists were, now I have seen them and though not being one of the club yet I have much admired certain Impressionist pictures – DEGAS, nude figure – Claude Monet, landscape.

And now for what regards what I myself have been doing, I have lacked money for paying models, else I had entirely given myself to figure painting but I have made a series of colour studies in painting simply flowers, red poppies, blue corn flowers and myosotys. White and rose roses, yellow chrysantemums – seeking oppositions of blue with orange, red and green, yellow and violet, seeking THE BROKEN AND NEUTRAL TONES to harmonise brutal extremes.

Trying to render intense COLOUR and not a GREY harmony.

Now after these gymnastics I lately did two heads which I dare say are better in light and colour than those I did before.

So as we said at the time in COLOUR seeking LIFE, the true drawing is modelling with colour.

I did a dozen landscapes too, frankly green, frankly blue.

And so I am struggling for life and progress in art.

Now I would very much like to know what you are doing and whether you ever think of going to Paris.

If ever you did come here, write to me before and I will, if you like, share my lodgings and studio with you so long as I have any. In spring – say February or even sooner – I may be going to the south of France, the land of the blue tones and gay colours.

And look here, if I knew you had longings for the same we might combine. I felt sure at the time that you are a thorough colourist and since I saw the Impressionists I assure you that neither your colour nor mine as it is developping itself, is exactly the same as their theories but so much dare I say, we have a chance and a good one of finding friends.

I hope your health is all right. I was rather low down in health when in Antwerp but got better here.

Write to me, in any case remember me to Allan, Briët, Rink, Durand, but I have not so often thought on any of them as I did think of you – almost daily.

Shaking hands cordially.

Yours truly,

Vincent

My present adress is

Mr Vincent van Gogh

54 Rue Lepic

Paris

What regards my chances of sale, look here, they are certainly not much but still I do have a beginning.

At this present moment I have found four dealers who have exhibited studies of mine. And I have exchanged studies with several artists.

Now the prices are 50 francs. Certainly not much but – as far as I can see one must sell cheap to rise, and even at costing price. And mind my dear fellow, Paris is Paris, there is but one Paris and however hard living may be here and if it became worse and harder even – the french air clears up the brain and does one good – a world of good.

I have been in Cormons studio for three or four months but did not find that as useful as I had expected it to be. It may be my fault however, any how I left there too as I left Antwerp and since I worked alone, and fancy that since I feel my own self more.

Trade is slow here, the great dealers sell Millet, Delacroix, Corot, Daubigny, Dupré, a few other masters at exorbitant prices. They do little or nothing for young artists. The second class dealers contrariwise sell those but at very low prices. If I asked more I would do nothing, I fancy. However I have faith in colour, even what regards the price the public will pay for it in the longer run.

But for the present things are awfully hard, therefore let anyone who risks to go over here consider there is no laying on roses at all.

What is to be gained is PROGRESS and, what the deuce, that it is to be found here I dare ascertain. Anyone who has a solid position elsewhere, let him stay where he is but for adventurers as myself I think they lose nothing in risking more. Especially as in my case I am not an adventurer by choice but by fate and feeling nowhere so much myself a stranger as in my family and country.

Kindly remember me to your landlady Mrs Roosmaelen and say her that if she will exhibit something of my work I will send her a small picture of mine.

To Willemien van Gogh (letter 574)

My dear little sister,

I thank you for your letter, although for my part I so detest writing these days, however there are questions in your letter that I do want to answer.

I must begin by contradicting you where you say that you thought Theo looked ‘so wretched’ this summer.

For my part, I think on the contrary that Theo’s appearance has become much more distinguished in the last year.

You have to be strong to endure life in Paris the way he has for so many years.

But might it not be that Theo’s family and friends in Amsterdam and The Hague haven’t treated him and even not received him with the cordiality that he deserved from them and to which he was entitled?

I can tell you in that regard that he was perhaps a little hurt by this, but he’s otherwise not letting it bother him, and now, when times are so bad in paintings, he’s still doing business, so it could be there’s some professional jealousy on the part of his Dutch friends.

Now what shall I say about your little piece about the plants and the rain? You see for yourself in nature that many a flower is trampled, freezes or is parched, further that not every grain of wheat, once it has ripened, ends up in the earth again to germinate there and become a stalk — but far and away the most grains do not develop but go to the mill — don’t they?

Now comparing people with grains of wheat — in every person who’s healthy and natural there’s the power to germinate as in a grain of wheat. And so natural life is germinating.

What the power to germinate is in wheat, so love is in us. Now we, I think, stand there pulling a long face or at a loss for words when, being thwarted in our natural development, we see that germination frustrated and ourselves placed in circumstances as hopeless as they must be for the wheat between the millstones.

If this happens to us and we’re utterly bewildered by the loss of our natural life, there are some among us who, willing to submit themselves to the course of things as they are, nonetheless don’t abandon their self-awareness and want to know how things are with them and what’s actually happening. And searching with good intentions in the books of which it is said they are a light in the darkness, with the best will in the world we find precious little certain at all and not always satisfaction to comfort us personally. And the diseases from which we civilized people suffer the most are melancholia and pessimism.

Like me, for instance, who can count so many years in my life when I completely lost all inclination to laugh, leaving aside whether or not this was my own fault, I for one need above all just to have a good laugh. I found that in Guy de Maupassant and there are others here, Rabelais among the old writers, Henri Rochefort among today’s, where one can find that — Voltaire in CANDIDE.

On the contrary, if one wants truth, life as it is, De Goncourt, for example, in Germinie Lacerteux, La fille Elisa, Zola in La joie de vivre and L’assommoir and so many other masterpieces paint life as we feel it ourselves and thus satisfy that need which we have, that people tell us the truth.

The work of the French naturalists Zola, Flaubert, Guy de Maupassant, De Goncourt, Richepin, Daudet, Huysmans is magnificent and one can scarcely be said to belong to one’s time if one isn’t familiar with them. Maupassant’s masterpiece is Bel-ami; I hope to be able to get it for you.

Is the Bible enough for us? Nowadays I believe Jesus himself would again say to those who just sit melancholy, it is not here, it is risen. Why seek ye the living among the dead?

If the spoken or written word is to remain the light of the world, it’s our right and our duty to acknowledge that we live in an age in which it’s written in such a way, spoken in such a way that in order to find something as great and as good and as original, and just as capable of overturning the whole old society as in the past, we can safely compare it with the old upheaval by the Christians.

For my part, I’m always glad that I’ve read the Bible better than many people nowadays, just because it gives me a certain peace that there have been such lofty ideas in the past. But precisely because I think the old is good, I find the new all the more so. All the more so because we can take action ourselves in our own age, and both the past and the future affect us only indirectly.

My own fortunes dictate above all that I’m making rapid progress in growing up into a little old man, you know, with wrinkles, with a bristly beard, with a number of false teeth &c.

But what does that matter? I have a dirty and difficult occupation, painting, and if I weren’t as I am I wouldn’t paint, but being as I am I often work with pleasure, and I see the possibility glimmering through of making paintings in which there’s some youth and freshness, although my own youth is one of those things I’ve lost. If I didn’t have Theo it wouldn’t be possible for me to do justice to my work, but because I have him as a friend I believe that I’ll make more progress and that things will run their course. It’s my plan to go to the south for a while, as soon as I can, where there’s even more colour and even more sun.

But what I hope to achieve is to paint a good portrait. Anyway.

Now to get back to your little piece, I feel uneasy about assuming for my own use or recommending to others for theirs the belief that powers above us intervene personally to help us or to comfort us. Providence is such a strange thing, and I tell you that I definitely don’t know what to make of it.

Well, in your piece there’s always a certain sentimentality and in its form, above all, it’s reminiscent of the stories about providence already referred to above, let’s say the providence in question, stories that so repeatedly failed to hold water and against which so very much could be said.

And above all I find it a very worrying matter that you believe you have to study in order to write. No, my dear little sister, learn to dance or fall in love with one or more notary’s clerks, officers, in short whoever’s within your reach; rather, much rather commit any number of follies than study in Holland, it serves absolutely no purpose other than to make someone dull, and so I won’t hear of it.

For my part, I still continually have the most impossible and highly unsuitable love affairs from which, as a rule, I emerge only with shame and disgrace.

And in this I’m absolutely right, in my own view, because I tell myself that in earlier years, when I should have been in love, I immersed myself in religious and socialist affairs and considered art more sacred, more than now. Why are religion or law or art so sacred? People who do nothing other than be in love are perhaps more serious and holier than those who sacrifice their love and their heart to an idea. Be this as it may, to write a book, to perform a deed, to make a painting with life in it, one must be a living person oneself. And so for you, unless you never want to progress, studying is very much a side issue. Enjoy yourself as much as you can and have as many distractions as you can, and be aware that what people want in art nowadays has to be very lively, with strong colour, very intense. So intensify your own health and strength and life a little, that’s the best study.

It would please me if you would write and tell me how Margot Begemann is doing and how they’re doing at De Groot’s. How did that business turn out? Did Sien de Groot marry her cousin? And did her child live? What I think about my own work is that the painting of the peasants eating potatoes that I did in Nuenen is after all the best thing I did. Only since then I haven’t had the opportunity to find models, but on the contrary have had the opportunity to study the question of colour. And if I do find models for my figures again later, then I hope to show that I’m looking for something other than little green landscapes or flowers. Last year I painted almost nothing but flowers to accustom myself to a colour other than grey, that’s to say pink, soft or bright green, light blue, violet, yellow, orange, fine red. And when I painted landscape in Asnières this summer I saw more colour in it than before. I’m studying this now in portraits. And I have to tell you that I’m painting none the worse for it, perhaps because I could tell you very many bad things about both painters and paintings if I wanted to, just as easily as I could tell you good things about them.

I don’t want to be one of the melancholics or those who become sour and bitter and morbid. To understand all is to forgive all, and I believe that if we knew everything we’d arrive at a certain serenity. Now having this serenity as much as possible, even when one knows — little — nothing — for certain, is perhaps a better remedy against all ills than what’s sold in the chemist’s. A lot comes of its own accord, one grows and develops of one’s own accord.

So don’t study and swot too much, because that makes for sterility. Enjoy yourself too much rather than too little, and don’t take art or love too seriously either — one can do little about it oneself, it’s mostly a matter of temperament. If I were living near you, I’d try to make you understand that it might be more practical for you to paint with me than to write, and that you might be more able to express your feelings that way. At any rate I can do something about painting personally, but as far as writing’s concerned I’m not in the business. Anyway, it’s not a bad idea for you to want to become an artist, because if one has fire in one, and soul, one can’t keep stifling them and — one would rather burn than suffocate. What’s inside must get out. Me, for instance, it gives me air when I make a painting, and without that I’d be unhappier than I am. Give Ma my very warmest regards.

Vincent

A la recherche du bonheur affected me very greatly. Now I’ve just read Mont-Oriol by Guy de Maupassant. Art often seems to be something very lofty and, as you say, something sacred. But that’s true of love too. And the problem is simply that not everyone thinks about it like that, and those who feel something of it and allow themselves to be swept away by it suffer greatly, firstly because of being misunderstood, but as much because our inspiration is so often inadequate or the work is made impossible by circumstances. One should be able to do two or preferably several things at the same time.

And there are times when it’s by no means clear to us that art should be something sacred or good.

Anyway, think carefully about whether it isn’t better, if one has a feeling for art and wants to work in it, to say that one is doing it because one was created with that feeling and can’t do anything else and is following one’s nature, than to say one is doing it for a good cause.

Does it not say in A la recherche du bonheur that evil lies in our own natures — which we didn’t create ourselves?

What I think is so good about the moderns is that they don’t moralize like the old ones.

It seems coarse to many people, for instance, and they’re angered by it: vice and virtue are chemical products like sugar and vitriol.

Pollard Willow, 1882

‘I’ve attacked that old giant of a pollard willow, and I believe it has turned out the best of the watercolours.’ Letter 252

The Potato Eaters, 1885

‘I plan to make a start this week on that thing with the peasants around a dish of potatoes in the evening’ Letter 490

‘Although I’ll have painted the actual painting in a relatively short time, and largely from memory, it’s taken a whole winter of painting studies of heads and hands.’ Letter 497

‘I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folk, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of MANUAL LABOUR and – that they have thus honestly earned their food.’ Letter 497

The Harvest, 1888

‘The colour here is actually very fine; when the vegetation is fresh it’s a rich green the like of which we seldom see in the north, calm. When it gets scorched and dusty it doesn’t become ugly, but then a landscape takes on tones of gold of every shade, green-gold, yellow-gold, red-gold, ditto bronze, copper, in short from lemon yellow to the dull yellow colour of, say, a pile of threshed grain.’ Letter 626

Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, 1888

‘Here’s an impression of mine, which is the result of a portrait that I painted in the mirror, and which Theo has: a pink-grey face with green eyes, ash-coloured hair, wrinkles in forehead and around the mouth, stiffly wooden, a very red beard, quite unkempt and sad’ Letter 626

The Yellow House (‘The street’), 1888

‘I live in a little yellow house with green door and shutters, whitewashed inside — on the white walls — very brightly coloured Japanese drawings — red tiles on the floor — the house in the full sun — and a bright blue sky above it and — the shadow in the middle of the day much shorter than at home.’ Letter 626

‘a square no. 30 canvas showing the house and its surroundings under a sulphur sun, under a pure cobalt sky. That’s a really difficult subject! But I want to conquer it for that very reason. Because it’s tremendous, these yellow houses in the sunlight and then the incomparable freshness of the blue. All the ground’s yellow, too. … the house to the left is pink, with green shutters; the one that’s shaded by a tree, that’s the restaurant where I go to eat supper every day. My friend the postman lives at the bottom of the street on the left, between the two railway bridges.’ Letter 691

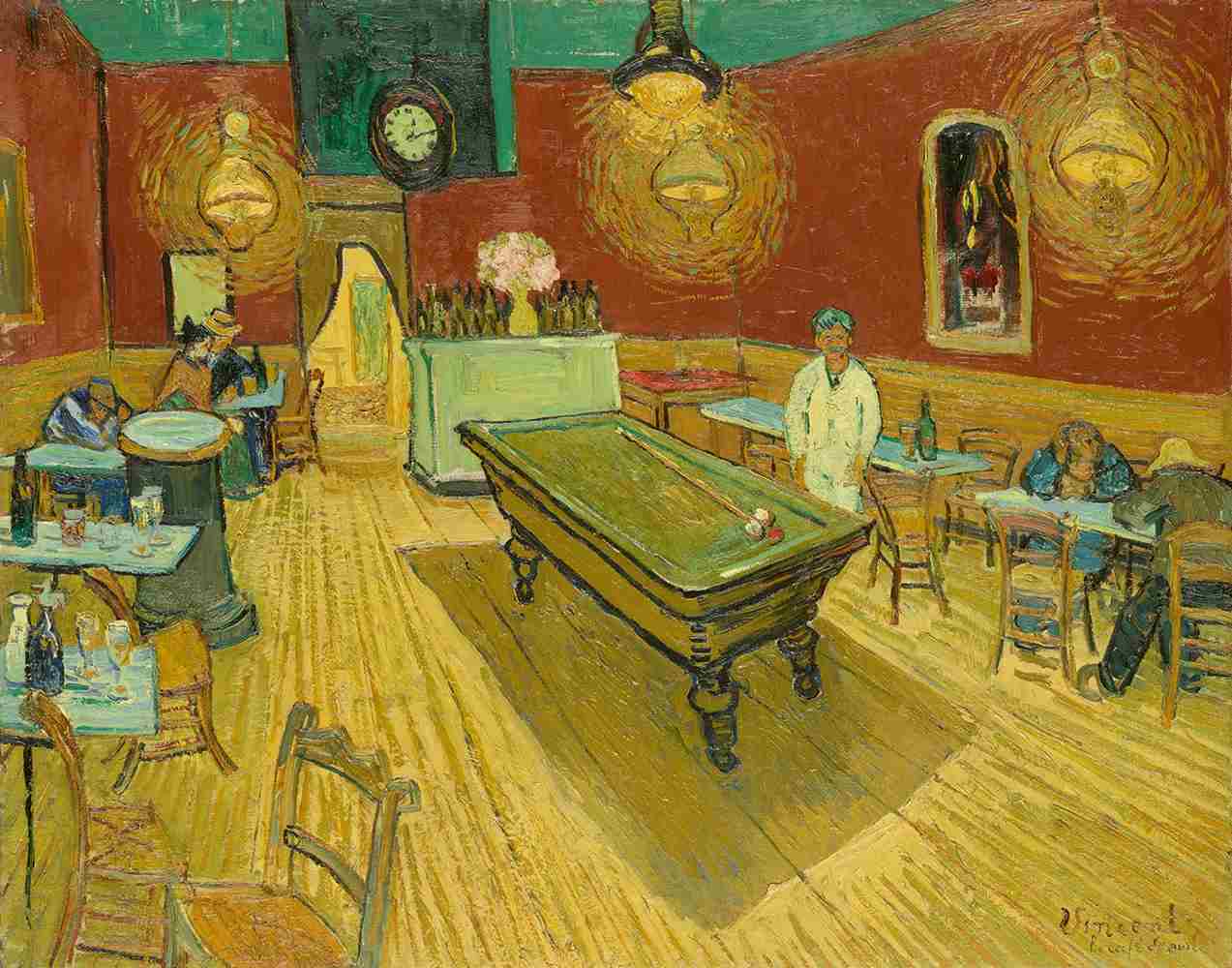

The Night Café, 1888

‘In my painting of the night café I’ve tried to express the idea that the café is a place where you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes. Anyway, I tried with contrasts of delicate pink and blood-red and wine-red. Soft Louis XV and Veronese green contrasting with yellow greens and hard blue greens. All of that in an ambience of a hellish furnace, in pale sulphur.’ Letter 677

Starry Night over the Rhône, 1888

‘Included herewith little croquis of a square no. 30 canvas — the starry sky at last, actually painted at night, under a gas-lamp. … Against the green-blue field of the sky the Great Bear has a green and pink sparkle whose discreet paleness contrasts with the harsh gold of the gaslight.’ Letter 691

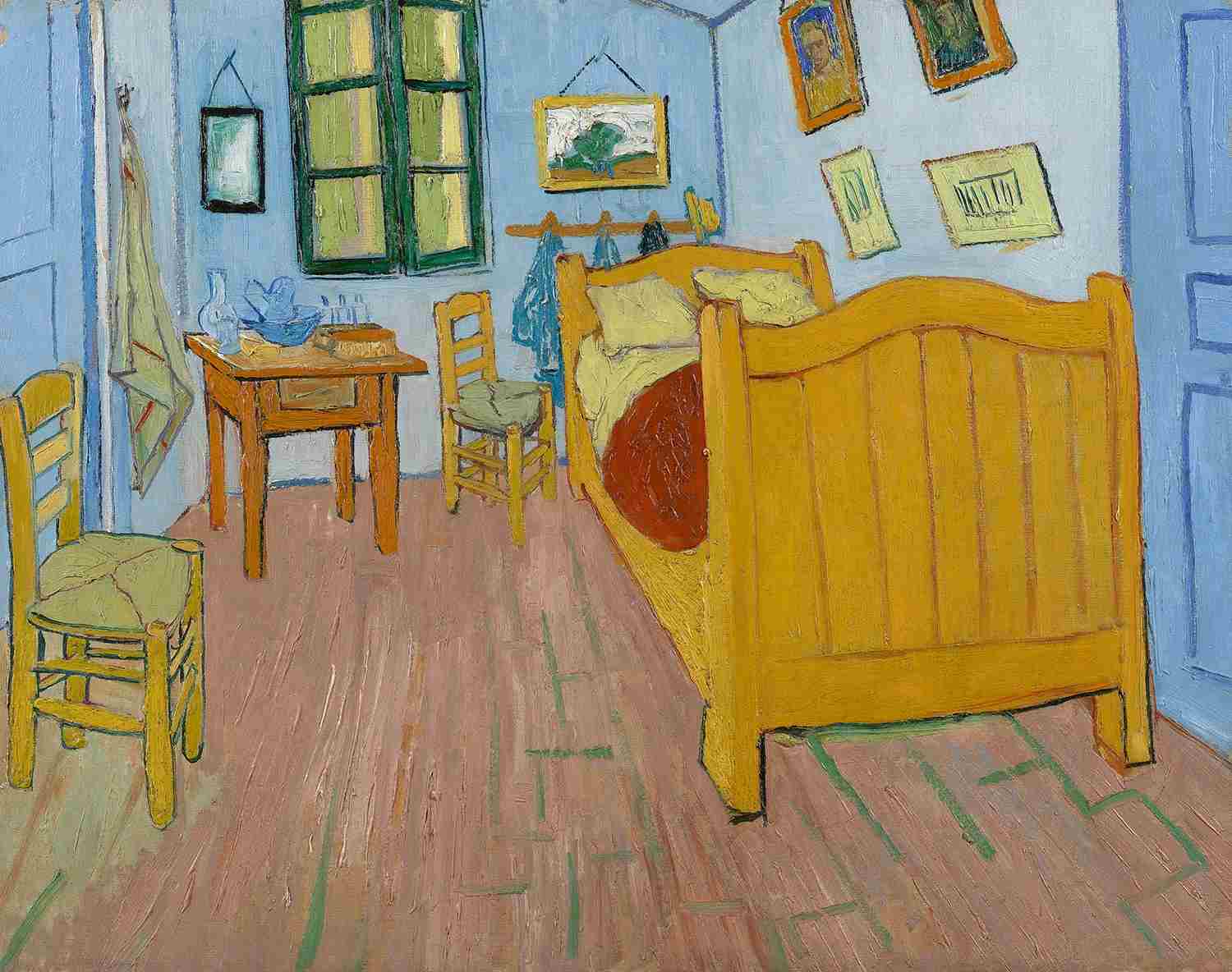

The Bedroom, 1888

‘I did, for my decoration once again, a no. 30 canvas of my bedroom with the whitewood furniture that you know. Ah, well, it amused me enormously doing this bare interior. … In flat tints, but coarsely brushed in full impasto, the walls pale lilac, the floor in a broken and faded red, the chairs and the bed chrome yellow, the pillows and the sheet very pale lemon green, the bedspread blood-red, the dressing-table orange, the washbasin blue, the window green. I had wished to express utter repose with all these very different tones, you see, among which the only white is the little note given by the mirror with a black frame’ Letter 706

Sunflowers, 1889

‘But you’ll see these big paintings of bouquets of 12, 14 sunflowers stuffed into this tiny little boudoir with a pretty bed and everything else elegant. It won’t be commonplace.’ Letter 677

‘if Jeannin has the peony, Quost the hollyhock, I indeed, before others, have taken the sunflower.’ Letter 739

Lullaby: Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle (La Berceuse), 1889

‘Today I made a fresh start on the canvas I had painted of Mrs Roulin, the one which had remained in a vague state as regards the hands because of my accident. As an arrangement of colours: the reds moving through to pure oranges, intensifying even more in the flesh tones up to the chromes, passing into the pinks and marrying with the olive and Veronese greens. As an Impressionist arrangement of colours, I’ve never devised anything better.’ Letter 739

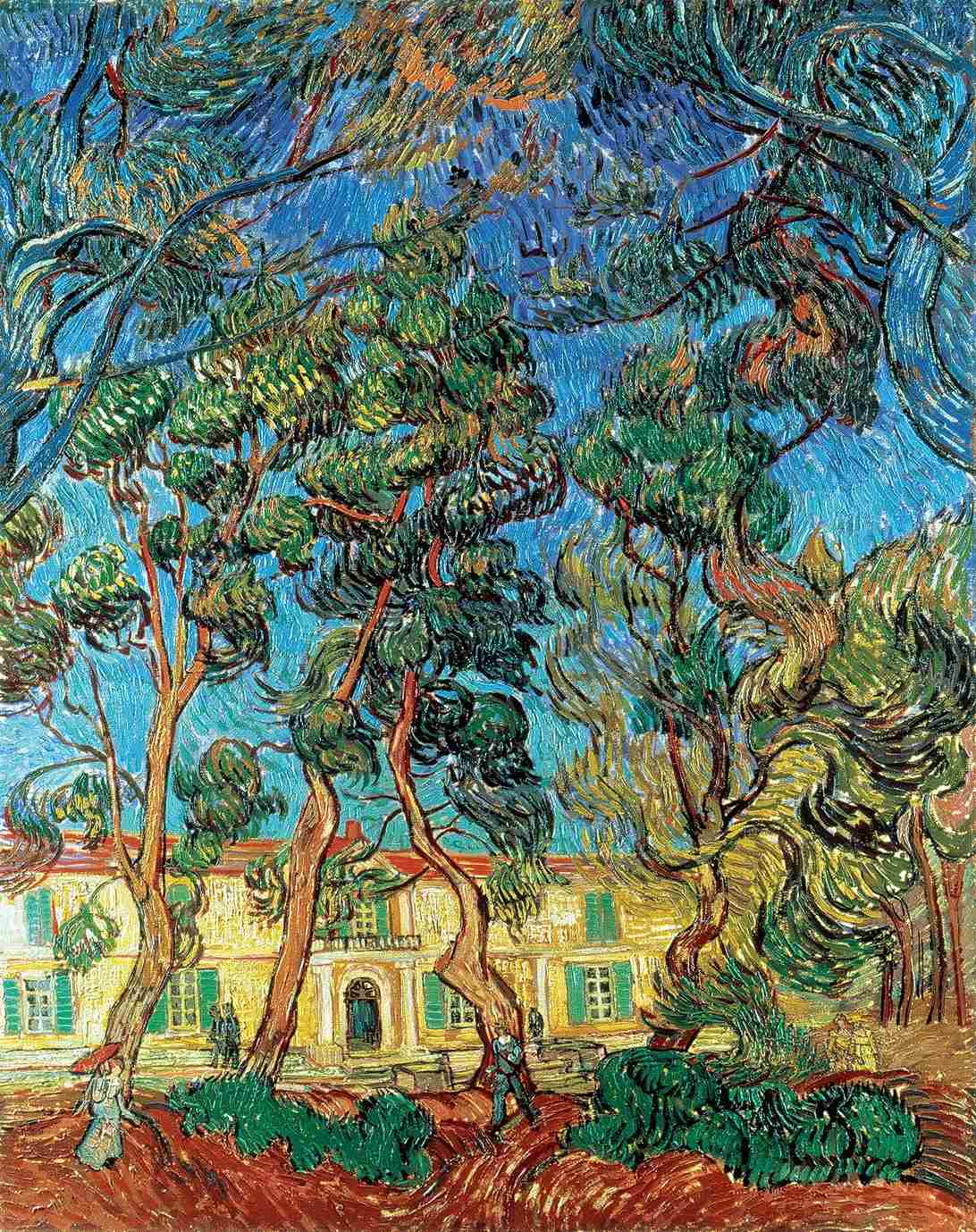

Hospital at Saint-Rémy, 1889

‘As for me, I’m going for at least 3 months into an asylum at St-Rémy, not far from here. In all I’ve had 4 big crises in which I hadn’t the slightest idea of what I said, wanted, did.’ Letter 764

Enclosed Field with Rising Sun, 1889

‘Another canvas depicts a sun rising over a field of new wheat. Receding lines of the furrows run high up on the canvas, towards a wall and a range of lilac hills. The field is violet and green-yellow. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow aureole. In it, in contrast to the other canvas, I have tried to express calm, a great peace.’ Letter 822

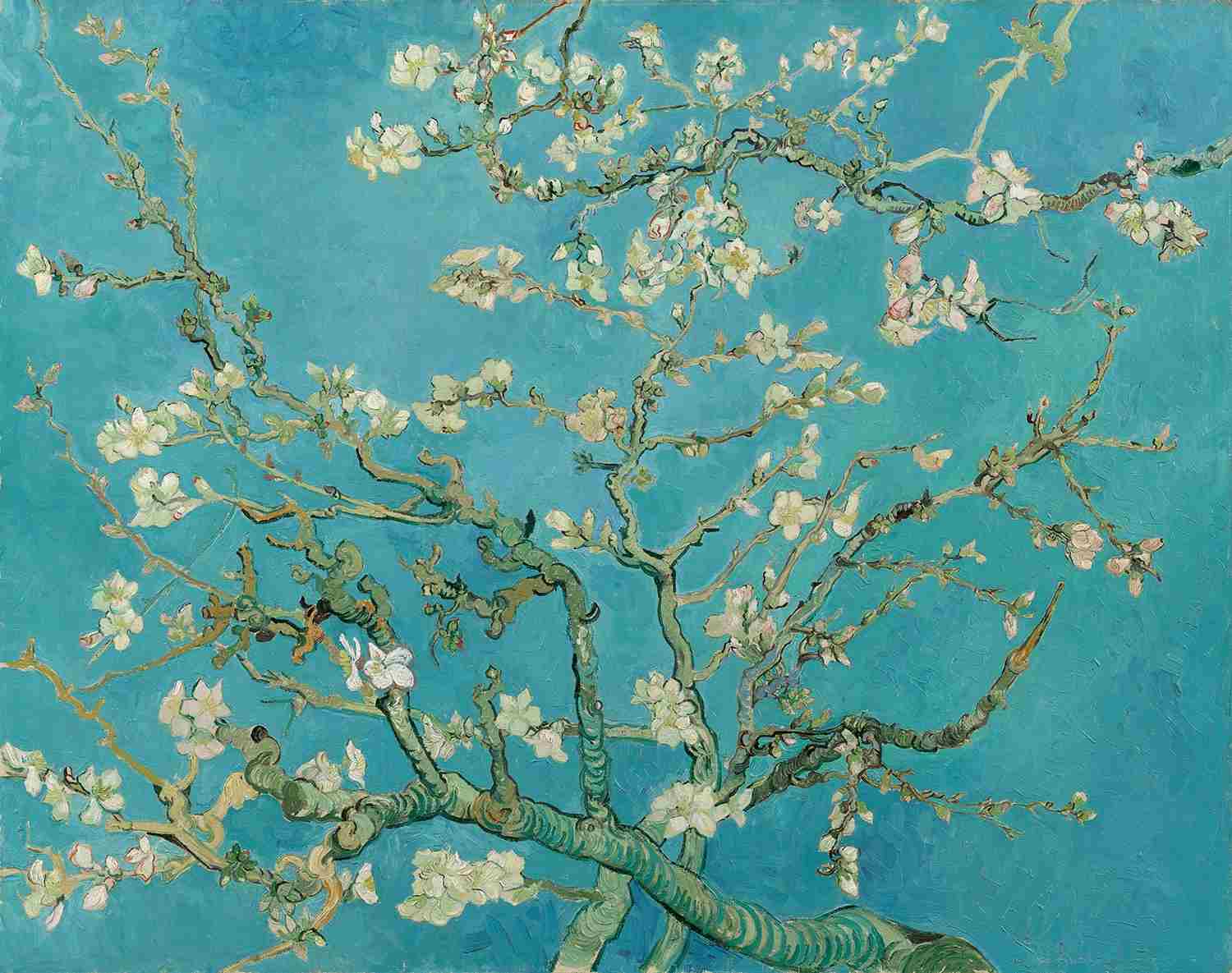

Almond Blossom, 1890

‘For Theo and Jo’s little one I brought back a rather large painting – which they’ve hung above the piano – white almond blossoms – big branches on a sky-blue background’ Letter 879

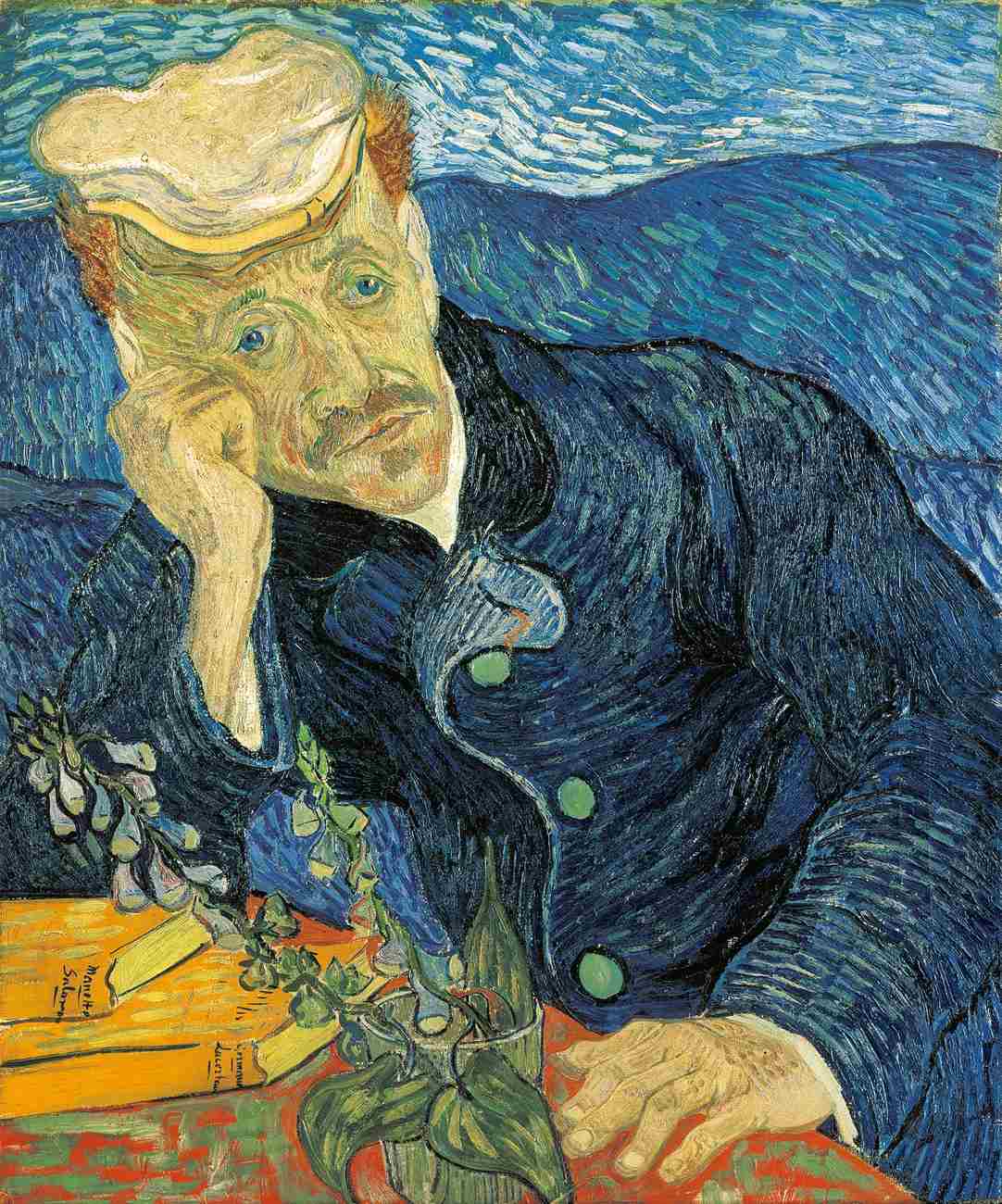

Doctor Gachet sitting at a table with books and a glass with foxglove, 1890

‘Mr Gachet is absolutely fanatical about this portrait … I feel that at his place I can do not too bad a painting every time I go there, and he’ll certainly continue to invite me to dinner each Sunday or Monday.’ Letter 877

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890

‘I’ve painted another three large canvases … They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness. You’ll see this soon, I hope – for I hope to bring them to you in Paris as soon as possible, since I’d almost believe that these canvases will tell you what I can’t say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside.’ Letter 898

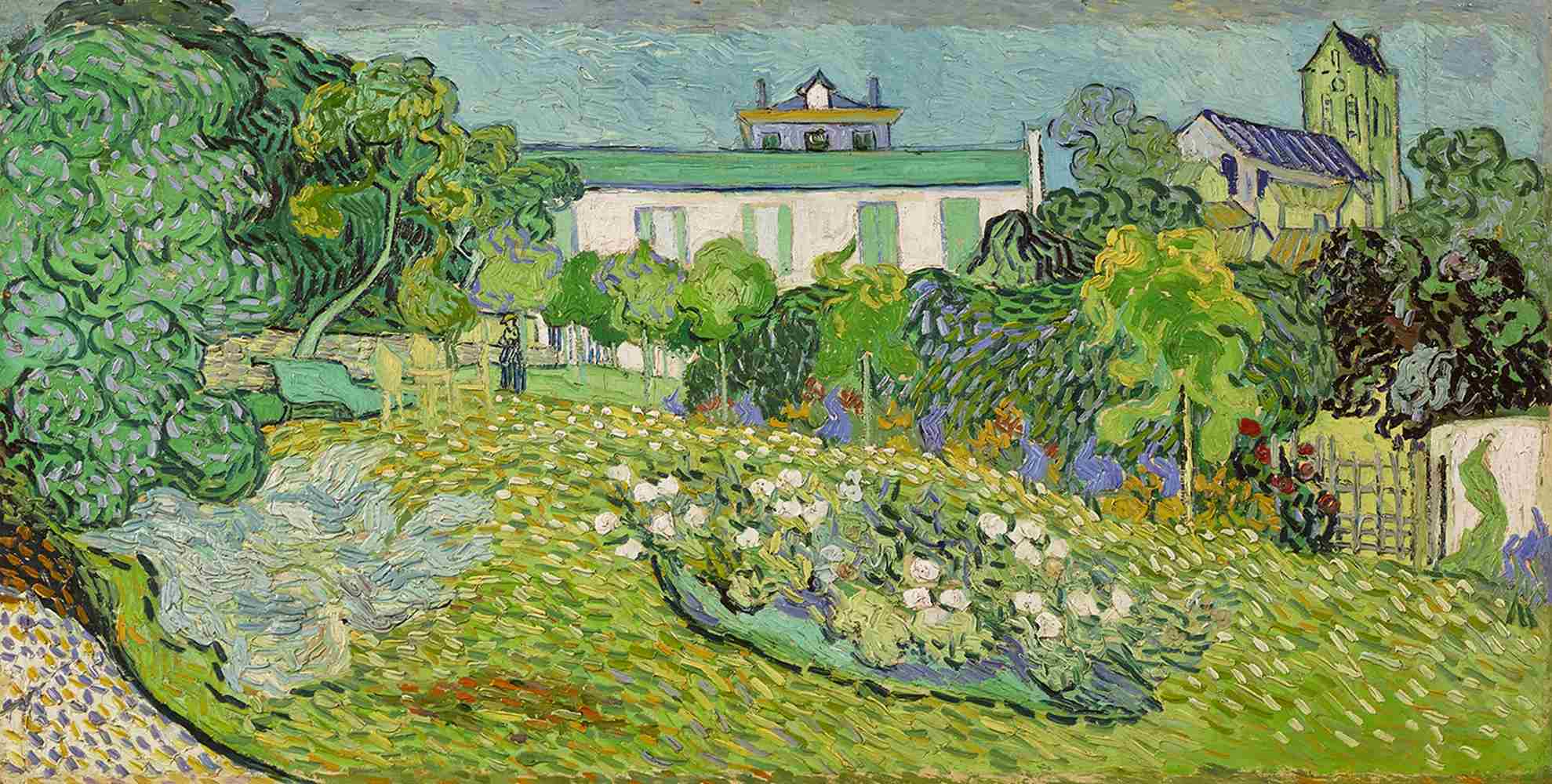

Daubigny’s Garden, 1890

‘Now the third canvas is Daubigny’s garden, a painting I’d been thinking about ever since I’ve been here.’ Letter 898

‘Foreground of green and pink grass, on the left a green and lilac bush and a stem of plants with whitish foliage. In the middle a bed of roses. To the right a hurdle, a wall, and above the wall a hazel tree with violet foliage. Then a hedge of lilac, a row of rounded yellow lime trees. The house itself in the background, pink with a roof of bluish tiles. A bench and 3 chairs, a dark figure with a yellow hat, and in the foreground a black cat. Sky pale green.’ Letter 902